User login

Doctors urge Congress to pass Zika funding

Federal health officials, pediatricians, and ob.gyns. are imploring Congress to pass an appropriations bill with sufficient money to fight the growing threat of the Zika virus.

“Funding for Zika research, for prevention, and for control efforts – including mosquito surveillance and control – is essentially all spent,” Beth P. Bell, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said during a press conference. The Obama administration “has already transferred millions of dollars from other important programs to help with the Zika response, [but] without additional resources from Congress, critical public health work may not be accomplished.”

President Obama asked Congress in February to appropriate $1.9 billion to address all aspects of the Zika virus situation in the United States; partisan politics surrounding funding for Planned Parenthood have derailed passage of the legislation to date.

Without additional, specific funding, development of a Zika vaccine would be severely limited, and virtually no funds would be available to conduct multitiered studies that are critical for protecting both women and children from the virus’ devastating effects, Dr. Bell said. Additionally, money allocated to state health departments for the management of patients with Zika virus would no longer be available. Development of tests for early diagnosis would be slowed or halted altogether.

“Allowing this to happen needlessly puts the American people at risk, and will result in more Zika infections and potentially more babies being born with microcephaly and other birth defects,” Dr. Bell added. “Congress has come back from their recess, and we hope that they will do the right thing.”

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “continues to develop, update, and issue guidance on the risks, prevention, assessment, and treatment of the Zika virus,” primarily through its practice advisories and resources available jointly through the CDC, ACOG president Thomas Gellhaus, MD, said.

“The biggest impact Zika has is on babies, and they are our future,” said Karen Remley, MD, executive director and CEO of the American Academy of Pediatricians, adding that funding is crucial to continue monitoring children who have been born with birth defects, as the long-term development of these and other issues is new territory for doctors across the United States and its territories.

As Congress prepared to adjourn in advance of the primary elections, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell noted that some progress is being made on Zika funding.

“We’ve made a lot of important progress already,” Sen. McConnell said Sept. 12 on the Senate floor. “I expect to move forward this week on a continuing resolution through Dec. 9 at last year’s enacted levels and include funds for Zika control and our veterans. Talks are continuing, and leaders from both parties will meet later this afternoon at the White House to discuss the progress and path forward.”

Federal health officials, pediatricians, and ob.gyns. are imploring Congress to pass an appropriations bill with sufficient money to fight the growing threat of the Zika virus.

“Funding for Zika research, for prevention, and for control efforts – including mosquito surveillance and control – is essentially all spent,” Beth P. Bell, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said during a press conference. The Obama administration “has already transferred millions of dollars from other important programs to help with the Zika response, [but] without additional resources from Congress, critical public health work may not be accomplished.”

President Obama asked Congress in February to appropriate $1.9 billion to address all aspects of the Zika virus situation in the United States; partisan politics surrounding funding for Planned Parenthood have derailed passage of the legislation to date.

Without additional, specific funding, development of a Zika vaccine would be severely limited, and virtually no funds would be available to conduct multitiered studies that are critical for protecting both women and children from the virus’ devastating effects, Dr. Bell said. Additionally, money allocated to state health departments for the management of patients with Zika virus would no longer be available. Development of tests for early diagnosis would be slowed or halted altogether.

“Allowing this to happen needlessly puts the American people at risk, and will result in more Zika infections and potentially more babies being born with microcephaly and other birth defects,” Dr. Bell added. “Congress has come back from their recess, and we hope that they will do the right thing.”

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “continues to develop, update, and issue guidance on the risks, prevention, assessment, and treatment of the Zika virus,” primarily through its practice advisories and resources available jointly through the CDC, ACOG president Thomas Gellhaus, MD, said.

“The biggest impact Zika has is on babies, and they are our future,” said Karen Remley, MD, executive director and CEO of the American Academy of Pediatricians, adding that funding is crucial to continue monitoring children who have been born with birth defects, as the long-term development of these and other issues is new territory for doctors across the United States and its territories.

As Congress prepared to adjourn in advance of the primary elections, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell noted that some progress is being made on Zika funding.

“We’ve made a lot of important progress already,” Sen. McConnell said Sept. 12 on the Senate floor. “I expect to move forward this week on a continuing resolution through Dec. 9 at last year’s enacted levels and include funds for Zika control and our veterans. Talks are continuing, and leaders from both parties will meet later this afternoon at the White House to discuss the progress and path forward.”

Federal health officials, pediatricians, and ob.gyns. are imploring Congress to pass an appropriations bill with sufficient money to fight the growing threat of the Zika virus.

“Funding for Zika research, for prevention, and for control efforts – including mosquito surveillance and control – is essentially all spent,” Beth P. Bell, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said during a press conference. The Obama administration “has already transferred millions of dollars from other important programs to help with the Zika response, [but] without additional resources from Congress, critical public health work may not be accomplished.”

President Obama asked Congress in February to appropriate $1.9 billion to address all aspects of the Zika virus situation in the United States; partisan politics surrounding funding for Planned Parenthood have derailed passage of the legislation to date.

Without additional, specific funding, development of a Zika vaccine would be severely limited, and virtually no funds would be available to conduct multitiered studies that are critical for protecting both women and children from the virus’ devastating effects, Dr. Bell said. Additionally, money allocated to state health departments for the management of patients with Zika virus would no longer be available. Development of tests for early diagnosis would be slowed or halted altogether.

“Allowing this to happen needlessly puts the American people at risk, and will result in more Zika infections and potentially more babies being born with microcephaly and other birth defects,” Dr. Bell added. “Congress has come back from their recess, and we hope that they will do the right thing.”

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “continues to develop, update, and issue guidance on the risks, prevention, assessment, and treatment of the Zika virus,” primarily through its practice advisories and resources available jointly through the CDC, ACOG president Thomas Gellhaus, MD, said.

“The biggest impact Zika has is on babies, and they are our future,” said Karen Remley, MD, executive director and CEO of the American Academy of Pediatricians, adding that funding is crucial to continue monitoring children who have been born with birth defects, as the long-term development of these and other issues is new territory for doctors across the United States and its territories.

As Congress prepared to adjourn in advance of the primary elections, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell noted that some progress is being made on Zika funding.

“We’ve made a lot of important progress already,” Sen. McConnell said Sept. 12 on the Senate floor. “I expect to move forward this week on a continuing resolution through Dec. 9 at last year’s enacted levels and include funds for Zika control and our veterans. Talks are continuing, and leaders from both parties will meet later this afternoon at the White House to discuss the progress and path forward.”

Zika’s not the only mosquito-borne virus to worry about

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – As the spread of Zika virus continues to garner attention in the national spotlight, two other mosquito-borne viral infections pose a potential threat to the United States: dengue fever and chikungunya.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Iris Z. Ahronowitz, MD, shared tips on how to spot and diagnose patients with these viral infections.

“You really need to use all the data at your disposal, including a thorough symptom history, a thorough exposure history, and of course, our most important tool in all of this: our eyes,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Reaching a diagnosis involves asking about epidemiologic exposure, symptoms, morphology, and performing confirmatory testing by PCR and/or ELISA. “Unfortunately we are not getting these results very quickly,” she said. “Sometimes the turn-around time can be 3 weeks or longer.”

She discussed the case of a 32-year-old woman who had returned from travel to Central Mexico (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58[2]:308-16). Two days later, she developed fever, fatigue, and retro-orbital headache, as well as flushing macular erythema over the chest. Three days later, she developed a generalized morbilliform eruption. Her white blood cell count was 1.5, platelets were 37, aspartate aminotransferase was 124 and alanine aminotransferase was 87.

The differential diagnosis for morbilliform eruption plus fever in a returning traveler is extensive, Dr. Ahronowitz said, including measles, chikungunya, West Nile virus, O’nyong-nyong fever, Mayaro virus, Sindbis virus, Ross river disease, Ebola/Marburg, dengue, and Zika. Bacterial/rickettsial possibilities include typhoid fever, typhus, and leptospirosis.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus. Five serotypes have been identified, the most recent in 2013. According to Dr. Ahronowitz, dengue ranks as the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from the Caribbean, South American, and Southeast Asia. “There are up to 100 million cases every year, 40% of the world population is at risk, and an estimated 80% of people are asymptomatic carriers, which is facilitating the spread of this disease,” she said. The most common vector is Aedes aegypti, a daytime biting mosquito that is endemic to the tropics and subtropics. But a new vector is emerging, A. albopictus, which is common in temperate areas. “Both types of mosquitoes are in the United States, and they’re spreading rapidly,” she said. “This is probably due to a combination of climate change and international travel.”

Dengue classically presents with sudden onset of fevers, headaches, and particularly retro-orbital pain, severe myalgia; 50%-82% of cases develop a distinctive rash. “While most viruses have nonspecific lab abnormalities, one that can be very helpful to you with suspected dengue is thrombocytopenia,” she said. “The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days.”

Rashes associated with dengue are classically biphasic and sequential. The initial rash occurs within 24-48 hours of symptom onset and is often mistaken for sunburn, with a flushing erythema of the face, neck, and chest. Three to five days later, a subsequent rash develops that starts out as a generalized morbilliform eruption but becomes confluent with petechiae and islands of sparing. “It’s been described as white islands in a sea of red,” Dr. Ahronowitz said.

A more severe form of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever, is characterized by extensive purpura and bleeding from mucosa, GI tract, and injection sites. “The patients who get this have prior immunity to a different serotype,” she said. “This is thought to be due to a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement whereby the presence of preexisting antibodies facilitates entry of the virus and produces a more robust inflammatory response. Most of these patients, even the ones with severe dengue, recover fully. The most common long-term sequela we’re seeing is chronic fatigue.”

The diagnosis is made with viral PCR from serum less than 7 days from onset of symptoms, or IgM ELISA more than 4 days from onset of symptoms. The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation and analgesia; there’s no specific treatment. “Do not give NSAIDs, which can potentiate hemorrhage; give acetaminophen for pain and fevers,” she advised. “A tetravalent vaccine is now available for dengue. Prevention is so important because there is no treatment.”

Next, Dr. Ahronowitz discussed the case of a 38-year-old man who returned from travel to Bangladesh (Int J Dermatol. 2008;47[1]:1148-52). Two days after returning he developed fever to 104 degrees, headaches, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Three days after returning, he developed severe pain in the wrist, knees, and ankles, and a rash. “This rash was not specific, it was a morbilliform eruption primarily on the chest,” she said.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with chikungunya, a single-strand RNA mosquito-borne virus with the same vectors as dengue. “This has been wreaking havoc across the Caribbean in the past few years,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Chikungunya was first identified in the Americas in 2013, and there have been hundreds of thousands of cases in the Caribbean.” The first case acquired in the United States occurred in Florida in the summer of 2014. As of January 2016 there were 679 imported cases of the infection in the United States. “Fortunately, this most recent epidemic is slowing down a bit, but it’s important to be aware of,” she said.

Clinical presentation of chikungunya includes an incubation period of 3-7 days, acute onset of high fevers, chills, and myalgia. Nonspecific exanthem around 3 days occurs in 40%-75% of cases, and symmetric polyarthralgias are common in the fingers, wrists, and ankles. Labs may reveal lymphopenia, AKI, and elevated AST/ALT. Acute symptoms resolve within 7-10 days.

Besides the rash, other cutaneous signs of the disease include aphthous-like ulcers and anogenital ulcers, particularly around the scrotum. Other patients may present with controfacial hyperpigmentation, also known as “brownie nose,” that appears with the rash. In babies, bullous lesions can occur. More than 20% of patients who acquire chikungunya still have severe joint pain 1 year after initial presentation. “This can be really debilitating,” she said. “A subset of patients will develop an inflammatory seronegative rheumatoid-like arthritis. It’s generally not a fatal condition except in the extremes of age and in people with a lot of comorbidities. Most people recover fully.”

As in dengue, clinicians can diagnose chikungunya by viral culture in the first 3 days of illness, and by RT-PCR in the first 8 days of illness. On serology, IgM is positive by 5 days of symptom onset.

“If testing is not available locally, contact the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention],” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Treatment is supportive. Evaluate for and treat potential coinfections, including dengue, malaria, and bacterial infections. If dengue is in the differential diagnosis, avoid NSAIDs.” A new vaccine for chikungunya is currently in phase II trials.

Dr. Ahronowitz reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – As the spread of Zika virus continues to garner attention in the national spotlight, two other mosquito-borne viral infections pose a potential threat to the United States: dengue fever and chikungunya.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Iris Z. Ahronowitz, MD, shared tips on how to spot and diagnose patients with these viral infections.

“You really need to use all the data at your disposal, including a thorough symptom history, a thorough exposure history, and of course, our most important tool in all of this: our eyes,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Reaching a diagnosis involves asking about epidemiologic exposure, symptoms, morphology, and performing confirmatory testing by PCR and/or ELISA. “Unfortunately we are not getting these results very quickly,” she said. “Sometimes the turn-around time can be 3 weeks or longer.”

She discussed the case of a 32-year-old woman who had returned from travel to Central Mexico (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58[2]:308-16). Two days later, she developed fever, fatigue, and retro-orbital headache, as well as flushing macular erythema over the chest. Three days later, she developed a generalized morbilliform eruption. Her white blood cell count was 1.5, platelets were 37, aspartate aminotransferase was 124 and alanine aminotransferase was 87.

The differential diagnosis for morbilliform eruption plus fever in a returning traveler is extensive, Dr. Ahronowitz said, including measles, chikungunya, West Nile virus, O’nyong-nyong fever, Mayaro virus, Sindbis virus, Ross river disease, Ebola/Marburg, dengue, and Zika. Bacterial/rickettsial possibilities include typhoid fever, typhus, and leptospirosis.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus. Five serotypes have been identified, the most recent in 2013. According to Dr. Ahronowitz, dengue ranks as the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from the Caribbean, South American, and Southeast Asia. “There are up to 100 million cases every year, 40% of the world population is at risk, and an estimated 80% of people are asymptomatic carriers, which is facilitating the spread of this disease,” she said. The most common vector is Aedes aegypti, a daytime biting mosquito that is endemic to the tropics and subtropics. But a new vector is emerging, A. albopictus, which is common in temperate areas. “Both types of mosquitoes are in the United States, and they’re spreading rapidly,” she said. “This is probably due to a combination of climate change and international travel.”

Dengue classically presents with sudden onset of fevers, headaches, and particularly retro-orbital pain, severe myalgia; 50%-82% of cases develop a distinctive rash. “While most viruses have nonspecific lab abnormalities, one that can be very helpful to you with suspected dengue is thrombocytopenia,” she said. “The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days.”

Rashes associated with dengue are classically biphasic and sequential. The initial rash occurs within 24-48 hours of symptom onset and is often mistaken for sunburn, with a flushing erythema of the face, neck, and chest. Three to five days later, a subsequent rash develops that starts out as a generalized morbilliform eruption but becomes confluent with petechiae and islands of sparing. “It’s been described as white islands in a sea of red,” Dr. Ahronowitz said.

A more severe form of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever, is characterized by extensive purpura and bleeding from mucosa, GI tract, and injection sites. “The patients who get this have prior immunity to a different serotype,” she said. “This is thought to be due to a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement whereby the presence of preexisting antibodies facilitates entry of the virus and produces a more robust inflammatory response. Most of these patients, even the ones with severe dengue, recover fully. The most common long-term sequela we’re seeing is chronic fatigue.”

The diagnosis is made with viral PCR from serum less than 7 days from onset of symptoms, or IgM ELISA more than 4 days from onset of symptoms. The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation and analgesia; there’s no specific treatment. “Do not give NSAIDs, which can potentiate hemorrhage; give acetaminophen for pain and fevers,” she advised. “A tetravalent vaccine is now available for dengue. Prevention is so important because there is no treatment.”

Next, Dr. Ahronowitz discussed the case of a 38-year-old man who returned from travel to Bangladesh (Int J Dermatol. 2008;47[1]:1148-52). Two days after returning he developed fever to 104 degrees, headaches, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Three days after returning, he developed severe pain in the wrist, knees, and ankles, and a rash. “This rash was not specific, it was a morbilliform eruption primarily on the chest,” she said.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with chikungunya, a single-strand RNA mosquito-borne virus with the same vectors as dengue. “This has been wreaking havoc across the Caribbean in the past few years,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Chikungunya was first identified in the Americas in 2013, and there have been hundreds of thousands of cases in the Caribbean.” The first case acquired in the United States occurred in Florida in the summer of 2014. As of January 2016 there were 679 imported cases of the infection in the United States. “Fortunately, this most recent epidemic is slowing down a bit, but it’s important to be aware of,” she said.

Clinical presentation of chikungunya includes an incubation period of 3-7 days, acute onset of high fevers, chills, and myalgia. Nonspecific exanthem around 3 days occurs in 40%-75% of cases, and symmetric polyarthralgias are common in the fingers, wrists, and ankles. Labs may reveal lymphopenia, AKI, and elevated AST/ALT. Acute symptoms resolve within 7-10 days.

Besides the rash, other cutaneous signs of the disease include aphthous-like ulcers and anogenital ulcers, particularly around the scrotum. Other patients may present with controfacial hyperpigmentation, also known as “brownie nose,” that appears with the rash. In babies, bullous lesions can occur. More than 20% of patients who acquire chikungunya still have severe joint pain 1 year after initial presentation. “This can be really debilitating,” she said. “A subset of patients will develop an inflammatory seronegative rheumatoid-like arthritis. It’s generally not a fatal condition except in the extremes of age and in people with a lot of comorbidities. Most people recover fully.”

As in dengue, clinicians can diagnose chikungunya by viral culture in the first 3 days of illness, and by RT-PCR in the first 8 days of illness. On serology, IgM is positive by 5 days of symptom onset.

“If testing is not available locally, contact the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention],” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Treatment is supportive. Evaluate for and treat potential coinfections, including dengue, malaria, and bacterial infections. If dengue is in the differential diagnosis, avoid NSAIDs.” A new vaccine for chikungunya is currently in phase II trials.

Dr. Ahronowitz reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – As the spread of Zika virus continues to garner attention in the national spotlight, two other mosquito-borne viral infections pose a potential threat to the United States: dengue fever and chikungunya.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Iris Z. Ahronowitz, MD, shared tips on how to spot and diagnose patients with these viral infections.

“You really need to use all the data at your disposal, including a thorough symptom history, a thorough exposure history, and of course, our most important tool in all of this: our eyes,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Reaching a diagnosis involves asking about epidemiologic exposure, symptoms, morphology, and performing confirmatory testing by PCR and/or ELISA. “Unfortunately we are not getting these results very quickly,” she said. “Sometimes the turn-around time can be 3 weeks or longer.”

She discussed the case of a 32-year-old woman who had returned from travel to Central Mexico (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58[2]:308-16). Two days later, she developed fever, fatigue, and retro-orbital headache, as well as flushing macular erythema over the chest. Three days later, she developed a generalized morbilliform eruption. Her white blood cell count was 1.5, platelets were 37, aspartate aminotransferase was 124 and alanine aminotransferase was 87.

The differential diagnosis for morbilliform eruption plus fever in a returning traveler is extensive, Dr. Ahronowitz said, including measles, chikungunya, West Nile virus, O’nyong-nyong fever, Mayaro virus, Sindbis virus, Ross river disease, Ebola/Marburg, dengue, and Zika. Bacterial/rickettsial possibilities include typhoid fever, typhus, and leptospirosis.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus. Five serotypes have been identified, the most recent in 2013. According to Dr. Ahronowitz, dengue ranks as the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from the Caribbean, South American, and Southeast Asia. “There are up to 100 million cases every year, 40% of the world population is at risk, and an estimated 80% of people are asymptomatic carriers, which is facilitating the spread of this disease,” she said. The most common vector is Aedes aegypti, a daytime biting mosquito that is endemic to the tropics and subtropics. But a new vector is emerging, A. albopictus, which is common in temperate areas. “Both types of mosquitoes are in the United States, and they’re spreading rapidly,” she said. “This is probably due to a combination of climate change and international travel.”

Dengue classically presents with sudden onset of fevers, headaches, and particularly retro-orbital pain, severe myalgia; 50%-82% of cases develop a distinctive rash. “While most viruses have nonspecific lab abnormalities, one that can be very helpful to you with suspected dengue is thrombocytopenia,” she said. “The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days.”

Rashes associated with dengue are classically biphasic and sequential. The initial rash occurs within 24-48 hours of symptom onset and is often mistaken for sunburn, with a flushing erythema of the face, neck, and chest. Three to five days later, a subsequent rash develops that starts out as a generalized morbilliform eruption but becomes confluent with petechiae and islands of sparing. “It’s been described as white islands in a sea of red,” Dr. Ahronowitz said.

A more severe form of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever, is characterized by extensive purpura and bleeding from mucosa, GI tract, and injection sites. “The patients who get this have prior immunity to a different serotype,” she said. “This is thought to be due to a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement whereby the presence of preexisting antibodies facilitates entry of the virus and produces a more robust inflammatory response. Most of these patients, even the ones with severe dengue, recover fully. The most common long-term sequela we’re seeing is chronic fatigue.”

The diagnosis is made with viral PCR from serum less than 7 days from onset of symptoms, or IgM ELISA more than 4 days from onset of symptoms. The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation and analgesia; there’s no specific treatment. “Do not give NSAIDs, which can potentiate hemorrhage; give acetaminophen for pain and fevers,” she advised. “A tetravalent vaccine is now available for dengue. Prevention is so important because there is no treatment.”

Next, Dr. Ahronowitz discussed the case of a 38-year-old man who returned from travel to Bangladesh (Int J Dermatol. 2008;47[1]:1148-52). Two days after returning he developed fever to 104 degrees, headaches, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Three days after returning, he developed severe pain in the wrist, knees, and ankles, and a rash. “This rash was not specific, it was a morbilliform eruption primarily on the chest,” she said.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with chikungunya, a single-strand RNA mosquito-borne virus with the same vectors as dengue. “This has been wreaking havoc across the Caribbean in the past few years,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Chikungunya was first identified in the Americas in 2013, and there have been hundreds of thousands of cases in the Caribbean.” The first case acquired in the United States occurred in Florida in the summer of 2014. As of January 2016 there were 679 imported cases of the infection in the United States. “Fortunately, this most recent epidemic is slowing down a bit, but it’s important to be aware of,” she said.

Clinical presentation of chikungunya includes an incubation period of 3-7 days, acute onset of high fevers, chills, and myalgia. Nonspecific exanthem around 3 days occurs in 40%-75% of cases, and symmetric polyarthralgias are common in the fingers, wrists, and ankles. Labs may reveal lymphopenia, AKI, and elevated AST/ALT. Acute symptoms resolve within 7-10 days.

Besides the rash, other cutaneous signs of the disease include aphthous-like ulcers and anogenital ulcers, particularly around the scrotum. Other patients may present with controfacial hyperpigmentation, also known as “brownie nose,” that appears with the rash. In babies, bullous lesions can occur. More than 20% of patients who acquire chikungunya still have severe joint pain 1 year after initial presentation. “This can be really debilitating,” she said. “A subset of patients will develop an inflammatory seronegative rheumatoid-like arthritis. It’s generally not a fatal condition except in the extremes of age and in people with a lot of comorbidities. Most people recover fully.”

As in dengue, clinicians can diagnose chikungunya by viral culture in the first 3 days of illness, and by RT-PCR in the first 8 days of illness. On serology, IgM is positive by 5 days of symptom onset.

“If testing is not available locally, contact the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention],” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Treatment is supportive. Evaluate for and treat potential coinfections, including dengue, malaria, and bacterial infections. If dengue is in the differential diagnosis, avoid NSAIDs.” A new vaccine for chikungunya is currently in phase II trials.

Dr. Ahronowitz reported having no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT PDA 2016

Another infant with Zika-related birth defect born in the United States

The first new case of a live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects in almost a month was reported during the week ending Sept. 1, bringing the U.S. total to 18 so far, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The infant was born in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia and is the first case of a Zika-related birth defect reported since the week ending Aug. 4. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children. There were no new Zika-related pregnancy losses for the week of Sept. 1, so the total remains at six for the states, D.C., and the territories, the CDC reported Sept. 8.

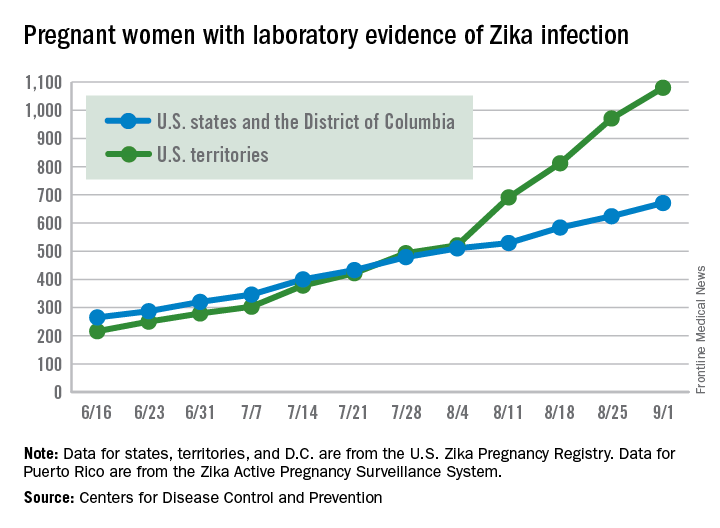

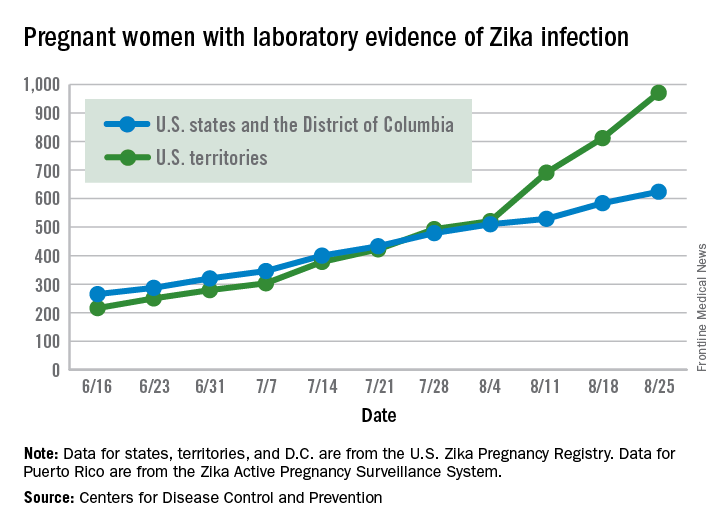

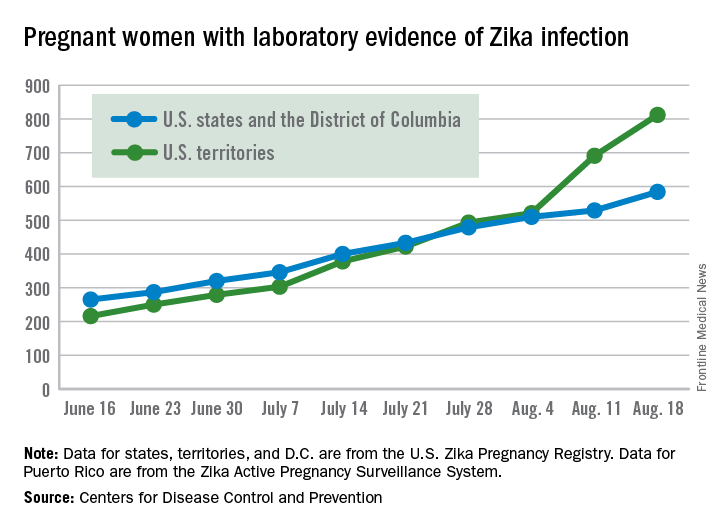

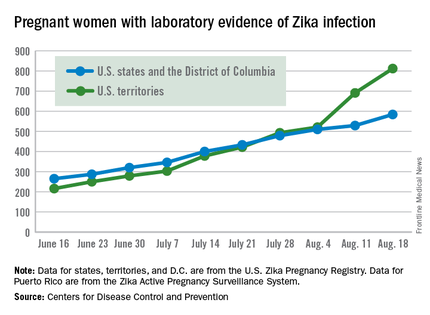

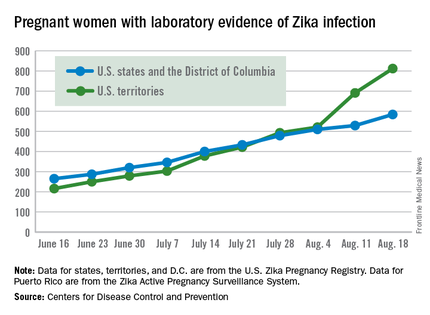

The number of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika infection increased by 156 during the week ending Sept. 1: 47 new cases in the states/D.C. and 109 new cases in the territories. The total number of pregnant women with Zika for 2016 is now 1,751, the CDC said.

For 2015-2016, there have been 18,833 cases reported in the entire U.S. population: 2,964 in the states/D.C. (all but 44 were travel associated) and 15,869 in the territories. All but 60 cases in the territories were locally acquired, and 98% have occurred in Puerto Rico, the CDC also reported Sept. 8.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The first new case of a live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects in almost a month was reported during the week ending Sept. 1, bringing the U.S. total to 18 so far, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The infant was born in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia and is the first case of a Zika-related birth defect reported since the week ending Aug. 4. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children. There were no new Zika-related pregnancy losses for the week of Sept. 1, so the total remains at six for the states, D.C., and the territories, the CDC reported Sept. 8.

The number of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika infection increased by 156 during the week ending Sept. 1: 47 new cases in the states/D.C. and 109 new cases in the territories. The total number of pregnant women with Zika for 2016 is now 1,751, the CDC said.

For 2015-2016, there have been 18,833 cases reported in the entire U.S. population: 2,964 in the states/D.C. (all but 44 were travel associated) and 15,869 in the territories. All but 60 cases in the territories were locally acquired, and 98% have occurred in Puerto Rico, the CDC also reported Sept. 8.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The first new case of a live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects in almost a month was reported during the week ending Sept. 1, bringing the U.S. total to 18 so far, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The infant was born in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia and is the first case of a Zika-related birth defect reported since the week ending Aug. 4. The CDC is not reporting state- or territorial-level data to protect the privacy of affected women and children. There were no new Zika-related pregnancy losses for the week of Sept. 1, so the total remains at six for the states, D.C., and the territories, the CDC reported Sept. 8.

The number of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika infection increased by 156 during the week ending Sept. 1: 47 new cases in the states/D.C. and 109 new cases in the territories. The total number of pregnant women with Zika for 2016 is now 1,751, the CDC said.

For 2015-2016, there have been 18,833 cases reported in the entire U.S. population: 2,964 in the states/D.C. (all but 44 were travel associated) and 15,869 in the territories. All but 60 cases in the territories were locally acquired, and 98% have occurred in Puerto Rico, the CDC also reported Sept. 8.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Another 199 pregnant women with Zika

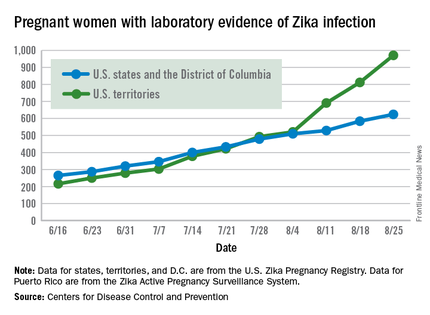

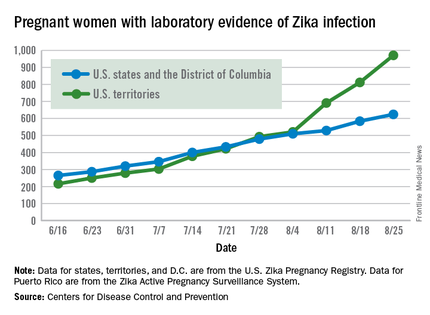

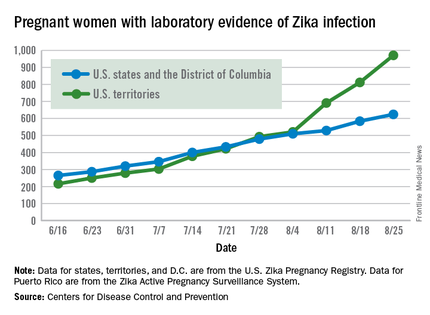

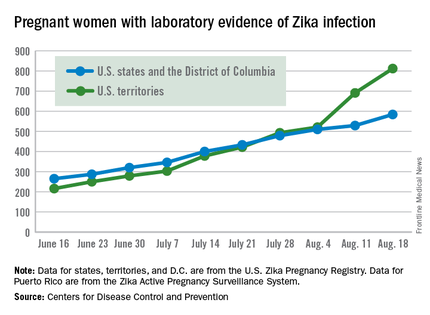

Zika virus shows no signs of slowing down, as the number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of possible infection in the United States and its territories took its largest jump yet during the week ending Aug. 25, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 199 new cases of Zika that week: 159 in the U.S. territories and 40 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The previous high had been 189 for the week ending Aug. 11. Cases in pregnant women for 2016 so far number 971 in the territories and 624 in the states and D.C. – a total of 1,595, the CDC reported Sept. 1.

The number of poor outcomes among pregnant women with Zika virus infection did not change for the week ending Aug. 25. The number of live-born infants with Zika-related birth defects remained at 17 – 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories – and the number of pregnancy losses with birth defects was still 6 – 5 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

Among the entire U.S. population, 16,832 cases of Zika have been reported to the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch in 2015-2016, with 5,304 reported for the week ending Aug. 31 (Puerto Rico retroactively reported 5,000 cases that had been identified between June 4 and Aug. 6). The states/D.C. account for 2,722 of total cases, and the territories have reported 14,110 cases, of which Puerto Rico accounts for 13,791, the CDC noted.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika virus shows no signs of slowing down, as the number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of possible infection in the United States and its territories took its largest jump yet during the week ending Aug. 25, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 199 new cases of Zika that week: 159 in the U.S. territories and 40 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The previous high had been 189 for the week ending Aug. 11. Cases in pregnant women for 2016 so far number 971 in the territories and 624 in the states and D.C. – a total of 1,595, the CDC reported Sept. 1.

The number of poor outcomes among pregnant women with Zika virus infection did not change for the week ending Aug. 25. The number of live-born infants with Zika-related birth defects remained at 17 – 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories – and the number of pregnancy losses with birth defects was still 6 – 5 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

Among the entire U.S. population, 16,832 cases of Zika have been reported to the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch in 2015-2016, with 5,304 reported for the week ending Aug. 31 (Puerto Rico retroactively reported 5,000 cases that had been identified between June 4 and Aug. 6). The states/D.C. account for 2,722 of total cases, and the territories have reported 14,110 cases, of which Puerto Rico accounts for 13,791, the CDC noted.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika virus shows no signs of slowing down, as the number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of possible infection in the United States and its territories took its largest jump yet during the week ending Aug. 25, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 199 new cases of Zika that week: 159 in the U.S. territories and 40 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The previous high had been 189 for the week ending Aug. 11. Cases in pregnant women for 2016 so far number 971 in the territories and 624 in the states and D.C. – a total of 1,595, the CDC reported Sept. 1.

The number of poor outcomes among pregnant women with Zika virus infection did not change for the week ending Aug. 25. The number of live-born infants with Zika-related birth defects remained at 17 – 16 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories – and the number of pregnancy losses with birth defects was still 6 – 5 in the states/D.C. and 1 in the territories, the CDC said. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

Among the entire U.S. population, 16,832 cases of Zika have been reported to the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch in 2015-2016, with 5,304 reported for the week ending Aug. 31 (Puerto Rico retroactively reported 5,000 cases that had been identified between June 4 and Aug. 6). The states/D.C. account for 2,722 of total cases, and the territories have reported 14,110 cases, of which Puerto Rico accounts for 13,791, the CDC noted.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Guillain-Barré incidence rose with Zika across Americas

Increased incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome corresponded closely with patterns of Zika virus disease incidence in Central and South America from April 2015 through March 2016, according to results from a new temporal and graphic analysis.

The findings show Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) cases increasing from 100% to nearly 900% above previously recorded baseline rates during periods of Zika virus transmission in El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Honduras, Suriname, Venezuela, and the Brazilian state of Bahia (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1609015).

The analysis of the yearlong period also revealed that declines in GBS incidence accompanied declines in Zika virus disease when and where transmission began to wane. The researchers, led by Marcos A. Espinal, MD, DrPH, of the Pan American Health Organization in Washington, did not find significant associations between co-circulation of dengue virus and GBS incidence. The study, which looked at 164,237 confirmed and suspected cases of Zika virus disease and 1,474 cases of GBS, found a 75% higher Zika virus disease incidence rate in women, which Dr. Espinal and colleagues said might be attributable to differences in health care–seeking behavior. GBS incidence, meanwhile, was 28% higher among males. The higher rate of GBS in men, the authors said, was consistent with findings from previous epidemiological studies of GBS.

While the new results did not show that Zika virus causes GBS, Dr. Espinal and colleagues wrote, they argued that they were indicative of a strong association, adding that GBS “could serve as a sentinel for Zika virus disease and other neurological disorders linked to Zika virus,” including microcephaly.

Most of the study authors worked for the Pan American Health Organization or for national health agencies in the data-contributing countries. None declared conflicts of interest.

Increased incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome corresponded closely with patterns of Zika virus disease incidence in Central and South America from April 2015 through March 2016, according to results from a new temporal and graphic analysis.

The findings show Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) cases increasing from 100% to nearly 900% above previously recorded baseline rates during periods of Zika virus transmission in El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Honduras, Suriname, Venezuela, and the Brazilian state of Bahia (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1609015).

The analysis of the yearlong period also revealed that declines in GBS incidence accompanied declines in Zika virus disease when and where transmission began to wane. The researchers, led by Marcos A. Espinal, MD, DrPH, of the Pan American Health Organization in Washington, did not find significant associations between co-circulation of dengue virus and GBS incidence. The study, which looked at 164,237 confirmed and suspected cases of Zika virus disease and 1,474 cases of GBS, found a 75% higher Zika virus disease incidence rate in women, which Dr. Espinal and colleagues said might be attributable to differences in health care–seeking behavior. GBS incidence, meanwhile, was 28% higher among males. The higher rate of GBS in men, the authors said, was consistent with findings from previous epidemiological studies of GBS.

While the new results did not show that Zika virus causes GBS, Dr. Espinal and colleagues wrote, they argued that they were indicative of a strong association, adding that GBS “could serve as a sentinel for Zika virus disease and other neurological disorders linked to Zika virus,” including microcephaly.

Most of the study authors worked for the Pan American Health Organization or for national health agencies in the data-contributing countries. None declared conflicts of interest.

Increased incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome corresponded closely with patterns of Zika virus disease incidence in Central and South America from April 2015 through March 2016, according to results from a new temporal and graphic analysis.

The findings show Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) cases increasing from 100% to nearly 900% above previously recorded baseline rates during periods of Zika virus transmission in El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Honduras, Suriname, Venezuela, and the Brazilian state of Bahia (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1609015).

The analysis of the yearlong period also revealed that declines in GBS incidence accompanied declines in Zika virus disease when and where transmission began to wane. The researchers, led by Marcos A. Espinal, MD, DrPH, of the Pan American Health Organization in Washington, did not find significant associations between co-circulation of dengue virus and GBS incidence. The study, which looked at 164,237 confirmed and suspected cases of Zika virus disease and 1,474 cases of GBS, found a 75% higher Zika virus disease incidence rate in women, which Dr. Espinal and colleagues said might be attributable to differences in health care–seeking behavior. GBS incidence, meanwhile, was 28% higher among males. The higher rate of GBS in men, the authors said, was consistent with findings from previous epidemiological studies of GBS.

While the new results did not show that Zika virus causes GBS, Dr. Espinal and colleagues wrote, they argued that they were indicative of a strong association, adding that GBS “could serve as a sentinel for Zika virus disease and other neurological disorders linked to Zika virus,” including microcephaly.

Most of the study authors worked for the Pan American Health Organization or for national health agencies in the data-contributing countries. None declared conflicts of interest.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

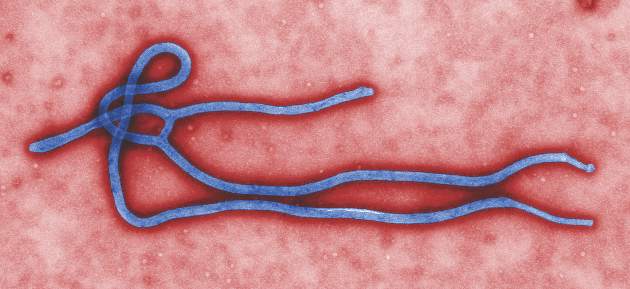

Mass administration of malaria drugs may cut morbidity during Ebola outbreaks

Mass administration of malaria chemoprevention during Ebola virus disease outbreaks may reduce cases of fever, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

During the October-December 2014 Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in Liberia, health care services were limited, negatively impacting malaria treatment. Hoping to reduce malaria-associated morbidity, investigators targeted four neighborhoods in Monrovia, Liberia – with a total population of 551,971 – for a mass drug administration (MDA) of malaria chemoprevention. MDA participants were divided into two treatment rounds, with 102,372 households verified as receiving treatment with the drug combination artesunate/amodiaquine by community leaders and a malaria committee in round 1, and 103,497 households verified in round 2.

Incidences of self-reported fever episodes declined significantly after round 1 (1.5%), compared with the month prior to round 1 (4.2%) (P < .0001). Self-reported fever incidences in children younger than 5 years of age (6.9%) and in older household members (3.8%) both decreased, to 1.1% and 1.6%, respectively, after round 1 of the MDA.

The researchers also found that self-reported fever was 4.9% lower after round 1 in household members who took a full course of artesunate/amodiaquine malaria chemoprevention (ASAQ-CP) but only 0.6% lower among household members who did not start or not complete a full course of ASAQ-CP. Still, reported incidence of fever declined in both groups, although the risk difference (RD) was significantly larger among the group that took part in the ASAQ-CP course (P < .001).

“Despite high acceptance and coverage of the MDA and the small impact of side effects, initiation of malaria chemoprevention was low, possibly due to health messaging and behavior in the pre-Ebola outbreak period and the ongoing lack of health care services,” researchers concluded. “Combining MDAs during Ebola outbreaks with longer-term interventions to prevent malaria and to improve access to health care might reduce the proportion of respondents saving their treatment for future malaria episodes.”

Read the full study in PLOS ONE (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161311).

Mass administration of malaria chemoprevention during Ebola virus disease outbreaks may reduce cases of fever, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

During the October-December 2014 Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in Liberia, health care services were limited, negatively impacting malaria treatment. Hoping to reduce malaria-associated morbidity, investigators targeted four neighborhoods in Monrovia, Liberia – with a total population of 551,971 – for a mass drug administration (MDA) of malaria chemoprevention. MDA participants were divided into two treatment rounds, with 102,372 households verified as receiving treatment with the drug combination artesunate/amodiaquine by community leaders and a malaria committee in round 1, and 103,497 households verified in round 2.

Incidences of self-reported fever episodes declined significantly after round 1 (1.5%), compared with the month prior to round 1 (4.2%) (P < .0001). Self-reported fever incidences in children younger than 5 years of age (6.9%) and in older household members (3.8%) both decreased, to 1.1% and 1.6%, respectively, after round 1 of the MDA.

The researchers also found that self-reported fever was 4.9% lower after round 1 in household members who took a full course of artesunate/amodiaquine malaria chemoprevention (ASAQ-CP) but only 0.6% lower among household members who did not start or not complete a full course of ASAQ-CP. Still, reported incidence of fever declined in both groups, although the risk difference (RD) was significantly larger among the group that took part in the ASAQ-CP course (P < .001).

“Despite high acceptance and coverage of the MDA and the small impact of side effects, initiation of malaria chemoprevention was low, possibly due to health messaging and behavior in the pre-Ebola outbreak period and the ongoing lack of health care services,” researchers concluded. “Combining MDAs during Ebola outbreaks with longer-term interventions to prevent malaria and to improve access to health care might reduce the proportion of respondents saving their treatment for future malaria episodes.”

Read the full study in PLOS ONE (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161311).

Mass administration of malaria chemoprevention during Ebola virus disease outbreaks may reduce cases of fever, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

During the October-December 2014 Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in Liberia, health care services were limited, negatively impacting malaria treatment. Hoping to reduce malaria-associated morbidity, investigators targeted four neighborhoods in Monrovia, Liberia – with a total population of 551,971 – for a mass drug administration (MDA) of malaria chemoprevention. MDA participants were divided into two treatment rounds, with 102,372 households verified as receiving treatment with the drug combination artesunate/amodiaquine by community leaders and a malaria committee in round 1, and 103,497 households verified in round 2.

Incidences of self-reported fever episodes declined significantly after round 1 (1.5%), compared with the month prior to round 1 (4.2%) (P < .0001). Self-reported fever incidences in children younger than 5 years of age (6.9%) and in older household members (3.8%) both decreased, to 1.1% and 1.6%, respectively, after round 1 of the MDA.

The researchers also found that self-reported fever was 4.9% lower after round 1 in household members who took a full course of artesunate/amodiaquine malaria chemoprevention (ASAQ-CP) but only 0.6% lower among household members who did not start or not complete a full course of ASAQ-CP. Still, reported incidence of fever declined in both groups, although the risk difference (RD) was significantly larger among the group that took part in the ASAQ-CP course (P < .001).

“Despite high acceptance and coverage of the MDA and the small impact of side effects, initiation of malaria chemoprevention was low, possibly due to health messaging and behavior in the pre-Ebola outbreak period and the ongoing lack of health care services,” researchers concluded. “Combining MDAs during Ebola outbreaks with longer-term interventions to prevent malaria and to improve access to health care might reduce the proportion of respondents saving their treatment for future malaria episodes.”

Read the full study in PLOS ONE (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161311).

FROM PLOS ONE

Congenital Zika virus associated with sensorineural hearing loss

Congenital Zika virus infection may be associated with sensorineural hearing loss, according to the latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the CDC.

“In the majority of cases of hearing loss associated with congenital viral infection, the damage to the auditory system is within the cochlea,” wrote the authors of the MMWR, led by Mariana C. Leal, PhD of the Hospital Agamenon Magalhães in Recife, Brazil. “It is likely that similar lesions account for the hearing deficit in children with congenital Zika virus infection” (MMWR. 2016 Aug 30.65:1-4)

Full auditory function evaluations were performed on 70 children born with microcephaly, all of whom had confirmed laboratory evidence of congenital Zika virus. One child with bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss was excluded because the child had already received treatment with amikacin (a known ototoxic antibiotic) prior to evaluation for this study. All children were ages 0-10 months; investigators defined Zika-associated microcephaly as head circumference of 32 cm or lower at birth. Gestational ages at birth ranged from 37 weeks to 1 day shy of 42 weeks.

Of the 69 children included for analysis, four (5.8%) were found to have sensorineural hearing loss with no other potential cause, which the investigators noted is “within the range (6%-65%) reported for other congenital viral infections.” The investigators also stated that the auditory issues were mainly evident in children whose mothers experienced a rash illness during the first trimester of their pregnancy.

“Children with evidence of congenital Zika virus infection who have normal initial screening tests should receive regular follow-up, because onset of hearing loss associated with other congenital viral infections can be delayed and the loss can be progressive,” the authors noted.

No disclosures or funding sources were reported.

Congenital Zika virus infection may be associated with sensorineural hearing loss, according to the latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the CDC.

“In the majority of cases of hearing loss associated with congenital viral infection, the damage to the auditory system is within the cochlea,” wrote the authors of the MMWR, led by Mariana C. Leal, PhD of the Hospital Agamenon Magalhães in Recife, Brazil. “It is likely that similar lesions account for the hearing deficit in children with congenital Zika virus infection” (MMWR. 2016 Aug 30.65:1-4)

Full auditory function evaluations were performed on 70 children born with microcephaly, all of whom had confirmed laboratory evidence of congenital Zika virus. One child with bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss was excluded because the child had already received treatment with amikacin (a known ototoxic antibiotic) prior to evaluation for this study. All children were ages 0-10 months; investigators defined Zika-associated microcephaly as head circumference of 32 cm or lower at birth. Gestational ages at birth ranged from 37 weeks to 1 day shy of 42 weeks.

Of the 69 children included for analysis, four (5.8%) were found to have sensorineural hearing loss with no other potential cause, which the investigators noted is “within the range (6%-65%) reported for other congenital viral infections.” The investigators also stated that the auditory issues were mainly evident in children whose mothers experienced a rash illness during the first trimester of their pregnancy.

“Children with evidence of congenital Zika virus infection who have normal initial screening tests should receive regular follow-up, because onset of hearing loss associated with other congenital viral infections can be delayed and the loss can be progressive,” the authors noted.

No disclosures or funding sources were reported.

Congenital Zika virus infection may be associated with sensorineural hearing loss, according to the latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the CDC.

“In the majority of cases of hearing loss associated with congenital viral infection, the damage to the auditory system is within the cochlea,” wrote the authors of the MMWR, led by Mariana C. Leal, PhD of the Hospital Agamenon Magalhães in Recife, Brazil. “It is likely that similar lesions account for the hearing deficit in children with congenital Zika virus infection” (MMWR. 2016 Aug 30.65:1-4)

Full auditory function evaluations were performed on 70 children born with microcephaly, all of whom had confirmed laboratory evidence of congenital Zika virus. One child with bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss was excluded because the child had already received treatment with amikacin (a known ototoxic antibiotic) prior to evaluation for this study. All children were ages 0-10 months; investigators defined Zika-associated microcephaly as head circumference of 32 cm or lower at birth. Gestational ages at birth ranged from 37 weeks to 1 day shy of 42 weeks.

Of the 69 children included for analysis, four (5.8%) were found to have sensorineural hearing loss with no other potential cause, which the investigators noted is “within the range (6%-65%) reported for other congenital viral infections.” The investigators also stated that the auditory issues were mainly evident in children whose mothers experienced a rash illness during the first trimester of their pregnancy.

“Children with evidence of congenital Zika virus infection who have normal initial screening tests should receive regular follow-up, because onset of hearing loss associated with other congenital viral infections can be delayed and the loss can be progressive,” the authors noted.

No disclosures or funding sources were reported.

FROM THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

Key clinical point: Congenital Zika virus could be associated with sensorineural hearing loss in infants.

Major finding: 4 of 69 children (5.8%) with microcephaly and confirmed congenital Zika virus infection had sensorineural hearing loss without evidence of any other possible causes.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 70 children born with microcephaly in Brazil from Nov. 2015 through May 2016.

Disclosures: No disclosures or funding source reported.

Zika outbreak forces better history taking, tracking

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – The definition of taking a thorough travel history has expanded with the spread of Zika.

Physicians “need to focus not only on patients’ travel histories, but also the travel histories and future travel plans of our patients’ sexual partners,” Ilona T. Goldfarb, a perinatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview. “We cannot rely on our patients to just [offer] that they’ve been in the Caribbean. We have to ask them diligently, and at every visit.”

Dr. Goldfarb added that immigration is a risk for Zika exposure, and may be a barrier to accurate history taking. In these cases, travel history will need to be performed in the patient’s spoken language to ensure accuracy, Dr. Goldfarb said. To track and communicate Zika information, Dr. Goldfarb and her colleagues have developed a three-part response based on their experience with previous infectious disease emergencies:

1. Communication. The practice is in regular communication with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the state public health department to ensure they are up to date on all guidelines.

2. Education. Dr. Goldfarb and her practice colleagues routinely brief each other and patients on any new information, including recommended testing and guidelines, as well as travel warnings.

3. Tracking. Clinicians use a tracking worksheet for every patient screened for potential Zika exposure, allowing them to prospectively and retrospectively review patients. This has already proven useful, Dr. Goldfarb said, when the CDC changed its guidance around testing of asymptomatic patients.

In a presentation at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dr. Goldfarb presented the data that she and her colleagues have collected so far on patients with Zika exposure.

As of Aug. 10, 2016, the practice had screened 142 women for Zika virus exposure since January 2016. More than 80% of the exposure came from travel to Zika-endemic areas. There have been few cases of exposure reported through sex, but Dr. Goldfarb said she thinks this type of exposure has been underreported because the link between infection and sex was not known until more recently.

Of the patients screened, 87% were appropriate candidates for Zika virus serum testing under CDC guidelines. There have been four positive serum tests for Zika exposure in Dr. Goldfarb’s patients so far.

In the one live birth, the newborn showed no visible signs of abnormalities. Testing revealed Zika virus RNA in the placenta, but not in the cord blood. The other three pregnancies were either terminated or associated with miscarriages. Again, Zika was detected in the placentas, but not in the fetuses.

Testing protocols have been a moving target since the outbreak began, according to Dr. Goldfarb. Some patients who call or are screened for possible exposure “are not actually eligible for testing because of the time frame or location of travel.”

To make sure that appropriate testing is being performed, Dr. Goldfarb advised designating an in-practice “Zika expert.” In her own practice, Dr. Goldfarb and one other colleague handle all Zika screening and inquiries from patients and colleagues. “This has greatly improved our efficiency and the experience for the patients,” she said in an interview.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health is piloting a program with Dr. Goldfarb’s practice to determine if using the “designated expert” approach will improve laboratory wait times, compared with the standard protocol of having clinicians obtain approval from a state epidemiologist before sending patient serum samples for testing.

It has taken from 2 to 68 days to receive test results from the state lab, although a period of 17 days is typical, Dr. Goldfarb reported. The process has improved since last March when state health officials ramped up their capacity, she said.

As of Aug. 10, Dr. Goldfarb’s practice has performed 107 ultrasounds for patients with suspected Zika virus, averaging 3 per patient. Across all ultrasounds, there were three abnormalities, including one case of bilateral ventriculomegaly. Earlier in that pregnancy, the patient had tested negative for Zika on real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing, which simultaneously screens for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Serum testing was also negative for Zika in the two other pregnancies with fetal abnormalities.

Dr. Goldfarb said she couldn’t quantify how much time is being spent on Zika screening and counseling since that is not being tracked, but she estimated that her practice takes between three and five calls or questions per day regarding the virus.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – The definition of taking a thorough travel history has expanded with the spread of Zika.

Physicians “need to focus not only on patients’ travel histories, but also the travel histories and future travel plans of our patients’ sexual partners,” Ilona T. Goldfarb, a perinatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview. “We cannot rely on our patients to just [offer] that they’ve been in the Caribbean. We have to ask them diligently, and at every visit.”

Dr. Goldfarb added that immigration is a risk for Zika exposure, and may be a barrier to accurate history taking. In these cases, travel history will need to be performed in the patient’s spoken language to ensure accuracy, Dr. Goldfarb said. To track and communicate Zika information, Dr. Goldfarb and her colleagues have developed a three-part response based on their experience with previous infectious disease emergencies:

1. Communication. The practice is in regular communication with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the state public health department to ensure they are up to date on all guidelines.

2. Education. Dr. Goldfarb and her practice colleagues routinely brief each other and patients on any new information, including recommended testing and guidelines, as well as travel warnings.

3. Tracking. Clinicians use a tracking worksheet for every patient screened for potential Zika exposure, allowing them to prospectively and retrospectively review patients. This has already proven useful, Dr. Goldfarb said, when the CDC changed its guidance around testing of asymptomatic patients.

In a presentation at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dr. Goldfarb presented the data that she and her colleagues have collected so far on patients with Zika exposure.

As of Aug. 10, 2016, the practice had screened 142 women for Zika virus exposure since January 2016. More than 80% of the exposure came from travel to Zika-endemic areas. There have been few cases of exposure reported through sex, but Dr. Goldfarb said she thinks this type of exposure has been underreported because the link between infection and sex was not known until more recently.

Of the patients screened, 87% were appropriate candidates for Zika virus serum testing under CDC guidelines. There have been four positive serum tests for Zika exposure in Dr. Goldfarb’s patients so far.

In the one live birth, the newborn showed no visible signs of abnormalities. Testing revealed Zika virus RNA in the placenta, but not in the cord blood. The other three pregnancies were either terminated or associated with miscarriages. Again, Zika was detected in the placentas, but not in the fetuses.

Testing protocols have been a moving target since the outbreak began, according to Dr. Goldfarb. Some patients who call or are screened for possible exposure “are not actually eligible for testing because of the time frame or location of travel.”

To make sure that appropriate testing is being performed, Dr. Goldfarb advised designating an in-practice “Zika expert.” In her own practice, Dr. Goldfarb and one other colleague handle all Zika screening and inquiries from patients and colleagues. “This has greatly improved our efficiency and the experience for the patients,” she said in an interview.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health is piloting a program with Dr. Goldfarb’s practice to determine if using the “designated expert” approach will improve laboratory wait times, compared with the standard protocol of having clinicians obtain approval from a state epidemiologist before sending patient serum samples for testing.

It has taken from 2 to 68 days to receive test results from the state lab, although a period of 17 days is typical, Dr. Goldfarb reported. The process has improved since last March when state health officials ramped up their capacity, she said.

As of Aug. 10, Dr. Goldfarb’s practice has performed 107 ultrasounds for patients with suspected Zika virus, averaging 3 per patient. Across all ultrasounds, there were three abnormalities, including one case of bilateral ventriculomegaly. Earlier in that pregnancy, the patient had tested negative for Zika on real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing, which simultaneously screens for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Serum testing was also negative for Zika in the two other pregnancies with fetal abnormalities.

Dr. Goldfarb said she couldn’t quantify how much time is being spent on Zika screening and counseling since that is not being tracked, but she estimated that her practice takes between three and five calls or questions per day regarding the virus.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – The definition of taking a thorough travel history has expanded with the spread of Zika.

Physicians “need to focus not only on patients’ travel histories, but also the travel histories and future travel plans of our patients’ sexual partners,” Ilona T. Goldfarb, a perinatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview. “We cannot rely on our patients to just [offer] that they’ve been in the Caribbean. We have to ask them diligently, and at every visit.”

Dr. Goldfarb added that immigration is a risk for Zika exposure, and may be a barrier to accurate history taking. In these cases, travel history will need to be performed in the patient’s spoken language to ensure accuracy, Dr. Goldfarb said. To track and communicate Zika information, Dr. Goldfarb and her colleagues have developed a three-part response based on their experience with previous infectious disease emergencies:

1. Communication. The practice is in regular communication with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the state public health department to ensure they are up to date on all guidelines.

2. Education. Dr. Goldfarb and her practice colleagues routinely brief each other and patients on any new information, including recommended testing and guidelines, as well as travel warnings.

3. Tracking. Clinicians use a tracking worksheet for every patient screened for potential Zika exposure, allowing them to prospectively and retrospectively review patients. This has already proven useful, Dr. Goldfarb said, when the CDC changed its guidance around testing of asymptomatic patients.

In a presentation at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dr. Goldfarb presented the data that she and her colleagues have collected so far on patients with Zika exposure.

As of Aug. 10, 2016, the practice had screened 142 women for Zika virus exposure since January 2016. More than 80% of the exposure came from travel to Zika-endemic areas. There have been few cases of exposure reported through sex, but Dr. Goldfarb said she thinks this type of exposure has been underreported because the link between infection and sex was not known until more recently.

Of the patients screened, 87% were appropriate candidates for Zika virus serum testing under CDC guidelines. There have been four positive serum tests for Zika exposure in Dr. Goldfarb’s patients so far.

In the one live birth, the newborn showed no visible signs of abnormalities. Testing revealed Zika virus RNA in the placenta, but not in the cord blood. The other three pregnancies were either terminated or associated with miscarriages. Again, Zika was detected in the placentas, but not in the fetuses.

Testing protocols have been a moving target since the outbreak began, according to Dr. Goldfarb. Some patients who call or are screened for possible exposure “are not actually eligible for testing because of the time frame or location of travel.”

To make sure that appropriate testing is being performed, Dr. Goldfarb advised designating an in-practice “Zika expert.” In her own practice, Dr. Goldfarb and one other colleague handle all Zika screening and inquiries from patients and colleagues. “This has greatly improved our efficiency and the experience for the patients,” she said in an interview.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health is piloting a program with Dr. Goldfarb’s practice to determine if using the “designated expert” approach will improve laboratory wait times, compared with the standard protocol of having clinicians obtain approval from a state epidemiologist before sending patient serum samples for testing.

It has taken from 2 to 68 days to receive test results from the state lab, although a period of 17 days is typical, Dr. Goldfarb reported. The process has improved since last March when state health officials ramped up their capacity, she said.

As of Aug. 10, Dr. Goldfarb’s practice has performed 107 ultrasounds for patients with suspected Zika virus, averaging 3 per patient. Across all ultrasounds, there were three abnormalities, including one case of bilateral ventriculomegaly. Earlier in that pregnancy, the patient had tested negative for Zika on real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing, which simultaneously screens for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Serum testing was also negative for Zika in the two other pregnancies with fetal abnormalities.

Dr. Goldfarb said she couldn’t quantify how much time is being spent on Zika screening and counseling since that is not being tracked, but she estimated that her practice takes between three and five calls or questions per day regarding the virus.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IDSOG

CDC reports asymptomatic Zika transmission; FDA begins universal blood testing

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have confirmed a case of Zika virus infection in a nonpregnant Maryland woman who likely contracted the virus through sexual intercourse with her asymptomatic male partner.

“To date, only one other case has been reported in which a man without symptoms might have sexually transmitted Zika virus to his female partner,” Richard B. Brooks, MD, and his colleagues wrote Aug. 26 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6534e2). “However, in that reported case, both the man and the woman had traveled to a country with ongoing Zika virus transmission where they were likely exposed to mosquitoes.”

In the current case, the couple had condomless vaginal sex 10 days and 14 days after his return from the Dominican Republic, along with oral sex on day 14. Two days after the last encounter, the woman began exhibiting symptoms of Zika virus infection, namely, a maculopapular rash and a fever. She sought medical care 3 days later (19 days after her partner returned to the United States). She had no other sexual partners during this time. Meanwhile, the male sex partner reported no symptoms of a Zika virus infection, other than simply being tired from his recent travel.

“The findings in this report indicate that it might be appropriate to consider persons who have condomless sex with partners returning from areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission as exposed to Zika virus, regardless of whether the returning traveler reports symptoms of Zika virus infection,” the researchers wrote.

Transmission of Zika virus through blood transfusions is also a growing concern, particularly if an asymptomatic individual donated blood.

On Aug. 26, the Food and Drug Administration announced recommendations to test all donated blood and blood components across the United States and its territories for the Zika virus, to mitigate the chances of transmitting the virus through transfusions. In February, the FDA first issued guidance recommending that only areas with active Zika virus transmission screen donated blood.