User login

Thrown From Motorcycle

ANSWER

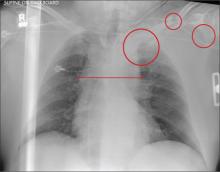

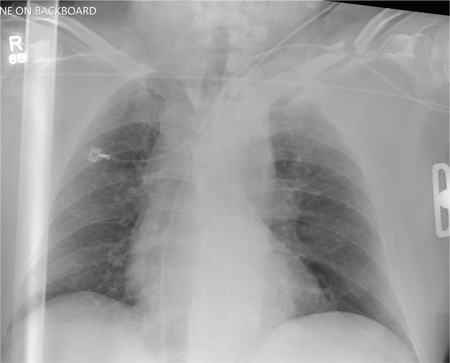

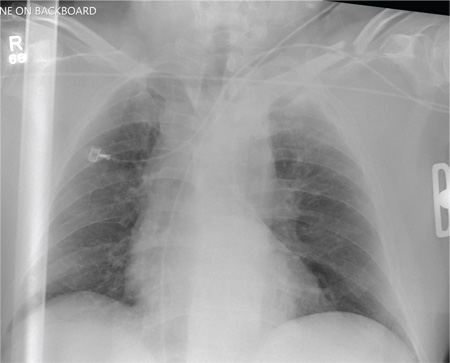

Several findings are evident from this radiograph. First, the quality is slightly diminished due to the patient’s size and artifact from the backboard. The patient’s mediastinum is somewhat widened, which is concerning for possible occult chest/vascular injury. There is some haziness within the left apical region suggestive of a hemothorax; no definite pneumothorax is seen. The left clavicle is fractured and displaced, and the left scapula is fractured as well.

ANSWER

Several findings are evident from this radiograph. First, the quality is slightly diminished due to the patient’s size and artifact from the backboard. The patient’s mediastinum is somewhat widened, which is concerning for possible occult chest/vascular injury. There is some haziness within the left apical region suggestive of a hemothorax; no definite pneumothorax is seen. The left clavicle is fractured and displaced, and the left scapula is fractured as well.

ANSWER

Several findings are evident from this radiograph. First, the quality is slightly diminished due to the patient’s size and artifact from the backboard. The patient’s mediastinum is somewhat widened, which is concerning for possible occult chest/vascular injury. There is some haziness within the left apical region suggestive of a hemothorax; no definite pneumothorax is seen. The left clavicle is fractured and displaced, and the left scapula is fractured as well.

A 57-year-old man is brought to your facility as a trauma code. He was riding a motorcycle on the highway, traveling approximately 45 to 50 mph, when the car in front of him abruptly stopped. He hit the car and was thrown from his bike. He believes he briefly lost consciousness but recalls emergency personnel tending to him. On arrival, he is awake and alert, complaining of pain in his neck, left arm, and left lower leg. Medical history is significant for borderline hypertension and a previous accident that resulted in an emergency laparotomy. Primary survey reveals stable vital signs: blood pressure of 157/100 mm Hg; heart rate, 110 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98% with supplemental oxygen. Pupils are equal and reactive; there are slightly decreased breath sounds on the left side. Abdominal exam appears benign. There is decreased mobility and pain in the patient’s left upper and left lower extremities, although no obvious deformity is noted. Preliminary chest radiograph is obtained before the patient is sent for CT. What is your impression?

Capturing the Impact of Language Barriers on Asthma Management During an Emergency Department Visit

Study Overview

Objective. To compare rates of asthma action plan use in limited English proficiency (LEP) caregivers compared with English proficient (EP) caregivers.

Design. Cross-sectional survey.

Participants and setting. A convenience sample of 107 Latino caregivers of children with asthma at an urban academic emergency department (ED). Surveys in the preferred language of the patient (English or Spanish, with the translated version previously validated) were distributed at the time of the ED visit. Interpreters were utilized when requested.

Main outcome measure. Caregiver use of an asthma action plan.

Main results. 51 LEP caregivers and 56 EP caregivers completed the survey. Mothers completed the surveys 87% of the time and the average age of patients was 4 years. Among the EP caregivers, 64% reported using an asthma action plan, while only 39% of the LEP caregivers reported using one. The difference was statistally significant (P = 0.01). Through both correlations and regressions, English proficiency was the only variable (others included health insurance status and level of caregiver education) that showed a significant effect on asthma action plan use.

Conclusions. Children whose caregiver had LEP were significantly less likely to have and use an asthma action plan. Asthma education in the language of choice of the patient may help improve asthma care.

Commentary

With 20% of US households now speaking a language other than English at home [1], language barriers between providers and patients present multiple challenges to health services delivery and can significantly contribute to immigrant health disparities. Despite US laws and multiple federal agency policies requiring the use of interpreters during health care encounters, organizations continue to fall short of providing interpreter services and often lack adequate or equivalent materials for patient education. Too often, providers overestimate their language skills [2,3], use colleagues as ad hoc interpreters out of convenience [4], or rely on family members for interpretation [4]—a practice that is universally discouraged.

Recent research does suggest that the timing of interpreter use is critical. In planned encounters such as primary care visits, interpreters can and should be scheduled for visits when a language-concordant provider is not available. During hospitalizations, including ED visits, interpreters are most effective when used on admission, during patient teaching, and upon discharge, and the timing of these visits has been shown to affect length of stay and readmission rates [5,6].

This study magnifies the consequences of failing to provide language-concordant services to patients and their caregivers. It also helps to identify one of the sources of pediatric asthma health disparities in Latino populations. The emphasis on the role of the caregiver in action plan utilization is a unique aspect of this study and it is one of the first to examine the issue in this way. It highlights the importance of caregivers in health system transitions and illustrates how a language barrier can potentially impact transitions.

The authors’ explicit use of a power analysis to calculate their sample size is a strength of the study. Furthermore, the authors differentiated their respondents by country of origin, something that rarely occurs in studies of Latinos [7], and allows the reader to differentiate the impact of the intervention at a micro level within this population. The presentation of Spanish language quotes with their translations within the manuscript provides transparency for bilingual readers to verify the accuracy of the authors’ translation.

There are, however, a number of methodological issues that should be noted. The authors acknowledge that they did not account for asthma severity in the survey nor control for it in the analysis, did not assess health literacy, and did not differentiate their results based on country of origin. The latter point is important because the immigration experience and demographic profiles of Latinos differs significantly by country of origin and could factor in to action plan use. The translation process used for survey instrument translation also did not illustrate how it accounted for the well-established linguistic variation that occurs in the Spanish language. Additionally, US census data shows that the main countries of origin of Latinos in the service area of the study are Puerto Rico, Ecuador, and Mexico [1]. The survey itself had Ecuador as a write in and Dominican as a response option. The combination presented in the survey reflects the Latino demographic composition in the nearest large urban area. Thus, when collecting country of origin data on immigrant patients, country choices should reflect local demographics and not national trends for maximum precision.

Another concern is that Spanish language literacy was not assessed. Many Latino immigrants may have limited reading ability in Spanish. For Mexican immigrants in particular, Spanish may be a second language after their indigenous language. This is also true for some South American Latino immigrants from the Andean region. Many Latino immigrants come to the United States with less than an 8th grade education and likely come from educational systems of poor quality, which subsequently affects their Spanish language reading and writing skills [8]. Assessing education level based on US equivalents is not an accurate way to gauge literacy. Thus, assessing reading literacy in Spanish before surveying patients would have been a useful step that could have further refined the results. These factors will have implications for action plan utilization and implementation for any chronic disease.

Providers often think that language barriers are an obvious factor in health disparities and service delivery, but few studies have actually captured or quantified the effects of language barriers on health outcomes. Most studies only identify language barriers as an access issue. This study provides a good illustration of the impact of a language barrier on a known and effective intervention for pediatric asthma management. Practitioners can take the consequences illustrated in this study and easily extrapolate the contribution to health disparities on a broader scale.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Practitioners caring for patients in EDs where the patient or caregiver has a language barrier should make every effort to use appropriate interpreter services when patient teaching occurs. Assessing not only for health literacy but reading ability in the LEP patient or caregiver is also important, since it will affect dyad’s ability to implement self-care measures recommended in patient teaching sessions or action plan implementation. Asking the patient what their country of origin is, regardless of their legal status, will help practitioners refine patient teaching and the language they (and the interpreter when appropriate) use to illustrate what needs to be done to manage their condition.

—Allison Squires, PhD, RN

1. Ryan C. Language use in the United States : 2011. Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC; 2013.

2. Diamond LC, Luft HS, Chung S, Jacobs EA. “Does this doctor speak my language?” Improving the characterization of physician non-English language skills. Health Serv Res 2012;47(1 Pt 2):556–69.

3. Jacobs EA. Patient centeredness in medical encounters requiring an interpreter. Am J Med 2000;109:515.

4. Hsieh E. Understanding medical interpreters: reconceptualizing bilingual health communication. Health Commun 2006;20:177–86.

5. Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med 2010;5:276–82.

6. Lindholm M, Hargraves JL, Ferguson WJ, Reed G. Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1294–9.

7. Gerchow L, Tagliaferro B, Squires A, et al. Latina food patterns in the United States: a qualitative metasynthesis. Nurs Res 2014;63:182–93.

8. Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Pérez-Stable EJ, et al. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient-physician communication. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:398–402.

Study Overview

Objective. To compare rates of asthma action plan use in limited English proficiency (LEP) caregivers compared with English proficient (EP) caregivers.

Design. Cross-sectional survey.

Participants and setting. A convenience sample of 107 Latino caregivers of children with asthma at an urban academic emergency department (ED). Surveys in the preferred language of the patient (English or Spanish, with the translated version previously validated) were distributed at the time of the ED visit. Interpreters were utilized when requested.

Main outcome measure. Caregiver use of an asthma action plan.

Main results. 51 LEP caregivers and 56 EP caregivers completed the survey. Mothers completed the surveys 87% of the time and the average age of patients was 4 years. Among the EP caregivers, 64% reported using an asthma action plan, while only 39% of the LEP caregivers reported using one. The difference was statistally significant (P = 0.01). Through both correlations and regressions, English proficiency was the only variable (others included health insurance status and level of caregiver education) that showed a significant effect on asthma action plan use.

Conclusions. Children whose caregiver had LEP were significantly less likely to have and use an asthma action plan. Asthma education in the language of choice of the patient may help improve asthma care.

Commentary

With 20% of US households now speaking a language other than English at home [1], language barriers between providers and patients present multiple challenges to health services delivery and can significantly contribute to immigrant health disparities. Despite US laws and multiple federal agency policies requiring the use of interpreters during health care encounters, organizations continue to fall short of providing interpreter services and often lack adequate or equivalent materials for patient education. Too often, providers overestimate their language skills [2,3], use colleagues as ad hoc interpreters out of convenience [4], or rely on family members for interpretation [4]—a practice that is universally discouraged.

Recent research does suggest that the timing of interpreter use is critical. In planned encounters such as primary care visits, interpreters can and should be scheduled for visits when a language-concordant provider is not available. During hospitalizations, including ED visits, interpreters are most effective when used on admission, during patient teaching, and upon discharge, and the timing of these visits has been shown to affect length of stay and readmission rates [5,6].

This study magnifies the consequences of failing to provide language-concordant services to patients and their caregivers. It also helps to identify one of the sources of pediatric asthma health disparities in Latino populations. The emphasis on the role of the caregiver in action plan utilization is a unique aspect of this study and it is one of the first to examine the issue in this way. It highlights the importance of caregivers in health system transitions and illustrates how a language barrier can potentially impact transitions.

The authors’ explicit use of a power analysis to calculate their sample size is a strength of the study. Furthermore, the authors differentiated their respondents by country of origin, something that rarely occurs in studies of Latinos [7], and allows the reader to differentiate the impact of the intervention at a micro level within this population. The presentation of Spanish language quotes with their translations within the manuscript provides transparency for bilingual readers to verify the accuracy of the authors’ translation.

There are, however, a number of methodological issues that should be noted. The authors acknowledge that they did not account for asthma severity in the survey nor control for it in the analysis, did not assess health literacy, and did not differentiate their results based on country of origin. The latter point is important because the immigration experience and demographic profiles of Latinos differs significantly by country of origin and could factor in to action plan use. The translation process used for survey instrument translation also did not illustrate how it accounted for the well-established linguistic variation that occurs in the Spanish language. Additionally, US census data shows that the main countries of origin of Latinos in the service area of the study are Puerto Rico, Ecuador, and Mexico [1]. The survey itself had Ecuador as a write in and Dominican as a response option. The combination presented in the survey reflects the Latino demographic composition in the nearest large urban area. Thus, when collecting country of origin data on immigrant patients, country choices should reflect local demographics and not national trends for maximum precision.

Another concern is that Spanish language literacy was not assessed. Many Latino immigrants may have limited reading ability in Spanish. For Mexican immigrants in particular, Spanish may be a second language after their indigenous language. This is also true for some South American Latino immigrants from the Andean region. Many Latino immigrants come to the United States with less than an 8th grade education and likely come from educational systems of poor quality, which subsequently affects their Spanish language reading and writing skills [8]. Assessing education level based on US equivalents is not an accurate way to gauge literacy. Thus, assessing reading literacy in Spanish before surveying patients would have been a useful step that could have further refined the results. These factors will have implications for action plan utilization and implementation for any chronic disease.

Providers often think that language barriers are an obvious factor in health disparities and service delivery, but few studies have actually captured or quantified the effects of language barriers on health outcomes. Most studies only identify language barriers as an access issue. This study provides a good illustration of the impact of a language barrier on a known and effective intervention for pediatric asthma management. Practitioners can take the consequences illustrated in this study and easily extrapolate the contribution to health disparities on a broader scale.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Practitioners caring for patients in EDs where the patient or caregiver has a language barrier should make every effort to use appropriate interpreter services when patient teaching occurs. Assessing not only for health literacy but reading ability in the LEP patient or caregiver is also important, since it will affect dyad’s ability to implement self-care measures recommended in patient teaching sessions or action plan implementation. Asking the patient what their country of origin is, regardless of their legal status, will help practitioners refine patient teaching and the language they (and the interpreter when appropriate) use to illustrate what needs to be done to manage their condition.

—Allison Squires, PhD, RN

Study Overview

Objective. To compare rates of asthma action plan use in limited English proficiency (LEP) caregivers compared with English proficient (EP) caregivers.

Design. Cross-sectional survey.

Participants and setting. A convenience sample of 107 Latino caregivers of children with asthma at an urban academic emergency department (ED). Surveys in the preferred language of the patient (English or Spanish, with the translated version previously validated) were distributed at the time of the ED visit. Interpreters were utilized when requested.

Main outcome measure. Caregiver use of an asthma action plan.

Main results. 51 LEP caregivers and 56 EP caregivers completed the survey. Mothers completed the surveys 87% of the time and the average age of patients was 4 years. Among the EP caregivers, 64% reported using an asthma action plan, while only 39% of the LEP caregivers reported using one. The difference was statistally significant (P = 0.01). Through both correlations and regressions, English proficiency was the only variable (others included health insurance status and level of caregiver education) that showed a significant effect on asthma action plan use.

Conclusions. Children whose caregiver had LEP were significantly less likely to have and use an asthma action plan. Asthma education in the language of choice of the patient may help improve asthma care.

Commentary

With 20% of US households now speaking a language other than English at home [1], language barriers between providers and patients present multiple challenges to health services delivery and can significantly contribute to immigrant health disparities. Despite US laws and multiple federal agency policies requiring the use of interpreters during health care encounters, organizations continue to fall short of providing interpreter services and often lack adequate or equivalent materials for patient education. Too often, providers overestimate their language skills [2,3], use colleagues as ad hoc interpreters out of convenience [4], or rely on family members for interpretation [4]—a practice that is universally discouraged.

Recent research does suggest that the timing of interpreter use is critical. In planned encounters such as primary care visits, interpreters can and should be scheduled for visits when a language-concordant provider is not available. During hospitalizations, including ED visits, interpreters are most effective when used on admission, during patient teaching, and upon discharge, and the timing of these visits has been shown to affect length of stay and readmission rates [5,6].

This study magnifies the consequences of failing to provide language-concordant services to patients and their caregivers. It also helps to identify one of the sources of pediatric asthma health disparities in Latino populations. The emphasis on the role of the caregiver in action plan utilization is a unique aspect of this study and it is one of the first to examine the issue in this way. It highlights the importance of caregivers in health system transitions and illustrates how a language barrier can potentially impact transitions.

The authors’ explicit use of a power analysis to calculate their sample size is a strength of the study. Furthermore, the authors differentiated their respondents by country of origin, something that rarely occurs in studies of Latinos [7], and allows the reader to differentiate the impact of the intervention at a micro level within this population. The presentation of Spanish language quotes with their translations within the manuscript provides transparency for bilingual readers to verify the accuracy of the authors’ translation.

There are, however, a number of methodological issues that should be noted. The authors acknowledge that they did not account for asthma severity in the survey nor control for it in the analysis, did not assess health literacy, and did not differentiate their results based on country of origin. The latter point is important because the immigration experience and demographic profiles of Latinos differs significantly by country of origin and could factor in to action plan use. The translation process used for survey instrument translation also did not illustrate how it accounted for the well-established linguistic variation that occurs in the Spanish language. Additionally, US census data shows that the main countries of origin of Latinos in the service area of the study are Puerto Rico, Ecuador, and Mexico [1]. The survey itself had Ecuador as a write in and Dominican as a response option. The combination presented in the survey reflects the Latino demographic composition in the nearest large urban area. Thus, when collecting country of origin data on immigrant patients, country choices should reflect local demographics and not national trends for maximum precision.

Another concern is that Spanish language literacy was not assessed. Many Latino immigrants may have limited reading ability in Spanish. For Mexican immigrants in particular, Spanish may be a second language after their indigenous language. This is also true for some South American Latino immigrants from the Andean region. Many Latino immigrants come to the United States with less than an 8th grade education and likely come from educational systems of poor quality, which subsequently affects their Spanish language reading and writing skills [8]. Assessing education level based on US equivalents is not an accurate way to gauge literacy. Thus, assessing reading literacy in Spanish before surveying patients would have been a useful step that could have further refined the results. These factors will have implications for action plan utilization and implementation for any chronic disease.

Providers often think that language barriers are an obvious factor in health disparities and service delivery, but few studies have actually captured or quantified the effects of language barriers on health outcomes. Most studies only identify language barriers as an access issue. This study provides a good illustration of the impact of a language barrier on a known and effective intervention for pediatric asthma management. Practitioners can take the consequences illustrated in this study and easily extrapolate the contribution to health disparities on a broader scale.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Practitioners caring for patients in EDs where the patient or caregiver has a language barrier should make every effort to use appropriate interpreter services when patient teaching occurs. Assessing not only for health literacy but reading ability in the LEP patient or caregiver is also important, since it will affect dyad’s ability to implement self-care measures recommended in patient teaching sessions or action plan implementation. Asking the patient what their country of origin is, regardless of their legal status, will help practitioners refine patient teaching and the language they (and the interpreter when appropriate) use to illustrate what needs to be done to manage their condition.

—Allison Squires, PhD, RN

1. Ryan C. Language use in the United States : 2011. Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC; 2013.

2. Diamond LC, Luft HS, Chung S, Jacobs EA. “Does this doctor speak my language?” Improving the characterization of physician non-English language skills. Health Serv Res 2012;47(1 Pt 2):556–69.

3. Jacobs EA. Patient centeredness in medical encounters requiring an interpreter. Am J Med 2000;109:515.

4. Hsieh E. Understanding medical interpreters: reconceptualizing bilingual health communication. Health Commun 2006;20:177–86.

5. Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med 2010;5:276–82.

6. Lindholm M, Hargraves JL, Ferguson WJ, Reed G. Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1294–9.

7. Gerchow L, Tagliaferro B, Squires A, et al. Latina food patterns in the United States: a qualitative metasynthesis. Nurs Res 2014;63:182–93.

8. Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Pérez-Stable EJ, et al. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient-physician communication. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:398–402.

1. Ryan C. Language use in the United States : 2011. Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC; 2013.

2. Diamond LC, Luft HS, Chung S, Jacobs EA. “Does this doctor speak my language?” Improving the characterization of physician non-English language skills. Health Serv Res 2012;47(1 Pt 2):556–69.

3. Jacobs EA. Patient centeredness in medical encounters requiring an interpreter. Am J Med 2000;109:515.

4. Hsieh E. Understanding medical interpreters: reconceptualizing bilingual health communication. Health Commun 2006;20:177–86.

5. Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med 2010;5:276–82.

6. Lindholm M, Hargraves JL, Ferguson WJ, Reed G. Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1294–9.

7. Gerchow L, Tagliaferro B, Squires A, et al. Latina food patterns in the United States: a qualitative metasynthesis. Nurs Res 2014;63:182–93.

8. Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Pérez-Stable EJ, et al. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient-physician communication. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:398–402.

Case Studies in Toxicology: Death and Taxus

Case

A 50-year-old man ingests two handfuls of small, red berries that he picked from a shrub in front of his apartment building, with the belief that they would have medicinal value. Two hours later, he developed abdominal cramping and vomited multiple times, followed shortly thereafter by profuse diaphoresis, lethargy, and ataxia. His concerned family brought him to the ED where his vital signs on presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 78/43 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 50 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 12 breaths/minute; temperature (T), 97.8°F. With the exception of bradycardia, the patient’s cardiac, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal. His skin was diaphoretic, and he had no focal motor or sensory deficits or tremor. Initial laboratory values were: hemoglobin, 12.6 g/dL; sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 4.6 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 20 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 17 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.2 mg/dL; glucose, 288 mg/dL. The patient’s troponin I level was slightly elevated at 0.06 ng/mL; electrocardiogram (ECG) results are shown in Figure 1.

Why do plant poisonings occur?

There is the general belief that what is natural is not only healthful but also safe. This is clearly not true: cyanide, uranium, and king cobras are all natural but hardly safe. While most plants chosen for their purported medicinal properties are generally harmless in most patients when taken in low doses, there are plants that are sufficiently poisonous to be consequential with even relatively small exposures. Some people, often unknowingly vulnerable due to genetic or other causes, are uniquely susceptible to even minute doses.

Humans probably learned about plant toxicity early on—most likely the hard way. To this day, however, the Internet is replete with traditional and avant-garde natural healing remedies involving the use of naturally-derived plant products. These numerous bioactive compounds are often sold in plant form or as extracts, the latter being more concerning given their more concentrated formulation.

Plant misidentification is a common cause of poisoning, whether the intended use is for food or medicine. For example, some mistake “deadly nightshade” (Atropa belladonna) berries, which are deep blue, for blueberries, or pokeweed roots for horseradish roots due to their similar appearances.1

Alternatively, even when a plant is correctly identified, patients may experience adverse effects if they exceed the “therapeutic dose” (eg, dysrhythmia from aconite roots used in traditional Chinese medicine) or if the plant is improperly prepared (eg, hypoglycemia from consuming unripe ackee fruit).2 In addition, a toxic plant such as Jimson weed (Datura stramonium) or coca leaf extract may be intentionally ingested for its psychoactive hallucinatory effects.2 Although rare in the United States, in certain parts of Asia, persons intent on self-harm may consume toxic plants.1

When ingested, what plants cause bradycardia and hypotension, and why do these effects occur?

The two broad classes of plant-derived toxins that can cause these findings are cardioactive steroids and sodium channel active agents.

Cardioactive Steroids

There are numerous botanical sources of cardioactive steroids (sometimes called cardiac glycosides) such as Digitalis lanata, from which digoxin is derived; and Digitalis purpurea, the source of digitoxin. Poisoning by Digitalis spp, squill, lily of the valley, oleander, yellow oleander, and Cerbera manghas are clinically similar. Cardioactive steroids act pharmacologically to block the sodium-potassium ATPase pump on the myocardial cell membrane. This in turn increases intracellular sodium, which subsequently inhibits the exchange of extracellular sodium for intracellular calcium, leading to inotropy. Clinical manifestations of toxicity include nausea, vomiting, hyperkalemia, bradycardia, cardiac dysrhythmias, and occasionally hypotension—some of which can be life-threatening.

Sodium Channel Active Agents

Several plant toxins affect the flow of sodium by blocking or activating the sodium channel. Both effects alter the rate and strength of cardiac contraction, causing cardiac dysrhythmias.

Aconite is often used in traditional Chinese medicine. In North America, it is mainly derived from Aconitinum napellus, commonly called monkshood, helmet flower, or wolfsbane. It effectively holds open the voltage-dependent sodium channel, increasing cellular excitability. By prolonging the sodium current influx, neuronal and cardiac repolarization eventually slow due to sodium overload, leading to bradycardia and hypotension, as well as neurological effects. Its cardiotoxicity resembles that caused by cardiac glycosides, though a history of paresthesias or muscle weakness may help to differentiate the two toxins.

Veratrum spp include false hellebore, Indian poke, and California hellebore. These plants are occasionally mistaken for leeks (ramps) and can cause vomiting, bradycardia, and hypotension by a mechanism of action similar to aconitine.

Grayanotoxins, a group of diterpenoid toxins found in death camas, azalea, Rhododendron spp, and mountain laurel, can become concentrated in honey made from these plants. Depending on the specific toxin, they variably open or close the sodium channel. In addition to causing bradycardia and hypotension, patients may exhibit mental status changes (“mad honey” poisoning) and seizures.2

Case Continuation

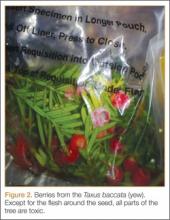

After rapid infusion of 1-liter of normal saline, the patient’s BP was 80/63 mm Hg and HR was 52 beats/minute. His wife arrived to the ED 30-minutes later with a plastic bag containing the red berries the patient had ingested. The emergency physician identified them as Taxus baccata, or more commonly, yew berries. The patient stated that he ingested both the red fleshy aril and chewed the hard central seed.

How is cardiotoxicity from yew berries treated?

Within hours of ingestion, toxicity progresses from nausea, abdominal pain, paresthesias, and ataxia, to bradycardia, cardiac conduction delays, wide-complex ventricular dysrhythmias and mental status changes.3 Although toxicity of Taxus has been known since antiquity, no antidote exists. Ventricular dysrhythmias causing hemodynamic instability should be electrically cardioverted, although there is no evidence to support the safety or efficacy of such therapy. Since the serum, and therefore cardiac concentration of taxine will be identical after cardioversion to its value prior, recurrent dysrhythmias are common.1 Sodium bicarbonate has been inconsistently effective in the treatment of wide-complex tachydysrhythmias,4 but its use seems counterintuitive for most cases. There may be merit to raising the sodium gradient on an already sodium overloaded myocyte, but short-term gain may lead to unintended consequences. Success with antidysrhythmics has been limited: although amiodarone is often used to treat wide-complex tachydysrhythmias, its efficacy in Taxus toxicity has been conflicting.4-6

There have been a few reported cases of yew alkaloid crossreactivity with digoxin assays, suggesting that digoxin-specific antibody fragments may bind taxine.7 There is no evidence, however, that cardioactive steroids are present in yew, and empiric use of antidigoxin Fab-fragments cannot be recommended. A single case report demonstrated that hemodialysis was ineffective in the removal of taxines, likely due to the toxin’s large volume of distribution.8 As a last resort, extracorporeal life support with membrane oxygenation is described favorably in two cases of yew berry poisoning refractory to conventional therapy.9,10

Case Conclusion

The patient’s ECGs showed a morphologically abnormal rhythm, possibly with a Brugada pattern, which are representative of the dysrhythmias caused by taxine’s inhibitory effects on the sodium and calcium channels. Despite an attempt at electrical cardioversion, the dysrhythmia persisted. He was given intravenous boluses of fluids and started on an amiodarone infusion. The patient’s BP gradually improved over the following 2 hours, and the dysrhythmia resolved with hemodynamic improvement. The amiodarone infusion was then discontinued, and he was admitted to the hospital for further testing. Echocardiography, electrophysiology studies, and cardiac catheterization were all normal. The absence of structural, dysrhythmogenic, and ischemic abnormalities supported the toxic etiology of his hemodynamic aberrations. He was discharged from the hospital 3 days later without report of sequelae.

Dr Nguyen is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Bruneton J. Toxic Plants; Dangerous to Humans and Animals. Paris, France: Lavoisier Publishing; 1999:4-752.

- Palmer ME, Betz JM. Plants. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE. In: Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2010:1537-1560.

- Nelson LS, Shih RD, Balick MJ. Handbook of Poisonous and Injurious Plants. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer/New York Botanical Garden; 2007:288-290.

- Pierog J, Kane B, Kane K, Donovan JW. Management of isolated yew berry toxicity with sodium bicarbonate: a case report in treatment efficacy. J Med Toxicol. 2009;5(2):84-89.

- Jones R, Jones J, Causer J, Ewins D, Goenka N, Joseph F. Yew tree poisoning: a near-fatal lesson from history. Clin Med. 2011;11(2):173-175.

- Willaert W, Claessens P, Vankelecom B, Vanderheyden M. Intoxication with Taxus baccata: cardiac arrhythmias following yew leaves ingestion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(4 Pt 1):511,512.

- Cummins RO, Haulman J, Quan L, Graves JR, Peterson D, Horan S. Near-fatal yew berry intoxication treated with external cardiac pacing and digoxin-specific FAB antibody fragments. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(1):38-43

- Dahlqvist M, Venzin R, König S, et al. Haemodialysis in Taxus baccata poisoning: a case report. QJM. 2012;105(4):359-361.

- Panzeri C, Bacis G, Ferri F, et al. Extracorporeal life support in severe Taxus baccata poisoning. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48(5):463-465.

- Soumagne N, Chauvet S, Chatellier D, Robert R, Charrière JM, Menu P. Treatment of yew leaf intoxication with extracorporeal circulation. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(3):354.e5-6.

Case

A 50-year-old man ingests two handfuls of small, red berries that he picked from a shrub in front of his apartment building, with the belief that they would have medicinal value. Two hours later, he developed abdominal cramping and vomited multiple times, followed shortly thereafter by profuse diaphoresis, lethargy, and ataxia. His concerned family brought him to the ED where his vital signs on presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 78/43 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 50 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 12 breaths/minute; temperature (T), 97.8°F. With the exception of bradycardia, the patient’s cardiac, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal. His skin was diaphoretic, and he had no focal motor or sensory deficits or tremor. Initial laboratory values were: hemoglobin, 12.6 g/dL; sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 4.6 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 20 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 17 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.2 mg/dL; glucose, 288 mg/dL. The patient’s troponin I level was slightly elevated at 0.06 ng/mL; electrocardiogram (ECG) results are shown in Figure 1.

Why do plant poisonings occur?

There is the general belief that what is natural is not only healthful but also safe. This is clearly not true: cyanide, uranium, and king cobras are all natural but hardly safe. While most plants chosen for their purported medicinal properties are generally harmless in most patients when taken in low doses, there are plants that are sufficiently poisonous to be consequential with even relatively small exposures. Some people, often unknowingly vulnerable due to genetic or other causes, are uniquely susceptible to even minute doses.

Humans probably learned about plant toxicity early on—most likely the hard way. To this day, however, the Internet is replete with traditional and avant-garde natural healing remedies involving the use of naturally-derived plant products. These numerous bioactive compounds are often sold in plant form or as extracts, the latter being more concerning given their more concentrated formulation.

Plant misidentification is a common cause of poisoning, whether the intended use is for food or medicine. For example, some mistake “deadly nightshade” (Atropa belladonna) berries, which are deep blue, for blueberries, or pokeweed roots for horseradish roots due to their similar appearances.1

Alternatively, even when a plant is correctly identified, patients may experience adverse effects if they exceed the “therapeutic dose” (eg, dysrhythmia from aconite roots used in traditional Chinese medicine) or if the plant is improperly prepared (eg, hypoglycemia from consuming unripe ackee fruit).2 In addition, a toxic plant such as Jimson weed (Datura stramonium) or coca leaf extract may be intentionally ingested for its psychoactive hallucinatory effects.2 Although rare in the United States, in certain parts of Asia, persons intent on self-harm may consume toxic plants.1

When ingested, what plants cause bradycardia and hypotension, and why do these effects occur?

The two broad classes of plant-derived toxins that can cause these findings are cardioactive steroids and sodium channel active agents.

Cardioactive Steroids

There are numerous botanical sources of cardioactive steroids (sometimes called cardiac glycosides) such as Digitalis lanata, from which digoxin is derived; and Digitalis purpurea, the source of digitoxin. Poisoning by Digitalis spp, squill, lily of the valley, oleander, yellow oleander, and Cerbera manghas are clinically similar. Cardioactive steroids act pharmacologically to block the sodium-potassium ATPase pump on the myocardial cell membrane. This in turn increases intracellular sodium, which subsequently inhibits the exchange of extracellular sodium for intracellular calcium, leading to inotropy. Clinical manifestations of toxicity include nausea, vomiting, hyperkalemia, bradycardia, cardiac dysrhythmias, and occasionally hypotension—some of which can be life-threatening.

Sodium Channel Active Agents

Several plant toxins affect the flow of sodium by blocking or activating the sodium channel. Both effects alter the rate and strength of cardiac contraction, causing cardiac dysrhythmias.

Aconite is often used in traditional Chinese medicine. In North America, it is mainly derived from Aconitinum napellus, commonly called monkshood, helmet flower, or wolfsbane. It effectively holds open the voltage-dependent sodium channel, increasing cellular excitability. By prolonging the sodium current influx, neuronal and cardiac repolarization eventually slow due to sodium overload, leading to bradycardia and hypotension, as well as neurological effects. Its cardiotoxicity resembles that caused by cardiac glycosides, though a history of paresthesias or muscle weakness may help to differentiate the two toxins.

Veratrum spp include false hellebore, Indian poke, and California hellebore. These plants are occasionally mistaken for leeks (ramps) and can cause vomiting, bradycardia, and hypotension by a mechanism of action similar to aconitine.

Grayanotoxins, a group of diterpenoid toxins found in death camas, azalea, Rhododendron spp, and mountain laurel, can become concentrated in honey made from these plants. Depending on the specific toxin, they variably open or close the sodium channel. In addition to causing bradycardia and hypotension, patients may exhibit mental status changes (“mad honey” poisoning) and seizures.2

Case Continuation

After rapid infusion of 1-liter of normal saline, the patient’s BP was 80/63 mm Hg and HR was 52 beats/minute. His wife arrived to the ED 30-minutes later with a plastic bag containing the red berries the patient had ingested. The emergency physician identified them as Taxus baccata, or more commonly, yew berries. The patient stated that he ingested both the red fleshy aril and chewed the hard central seed.

How is cardiotoxicity from yew berries treated?

Within hours of ingestion, toxicity progresses from nausea, abdominal pain, paresthesias, and ataxia, to bradycardia, cardiac conduction delays, wide-complex ventricular dysrhythmias and mental status changes.3 Although toxicity of Taxus has been known since antiquity, no antidote exists. Ventricular dysrhythmias causing hemodynamic instability should be electrically cardioverted, although there is no evidence to support the safety or efficacy of such therapy. Since the serum, and therefore cardiac concentration of taxine will be identical after cardioversion to its value prior, recurrent dysrhythmias are common.1 Sodium bicarbonate has been inconsistently effective in the treatment of wide-complex tachydysrhythmias,4 but its use seems counterintuitive for most cases. There may be merit to raising the sodium gradient on an already sodium overloaded myocyte, but short-term gain may lead to unintended consequences. Success with antidysrhythmics has been limited: although amiodarone is often used to treat wide-complex tachydysrhythmias, its efficacy in Taxus toxicity has been conflicting.4-6

There have been a few reported cases of yew alkaloid crossreactivity with digoxin assays, suggesting that digoxin-specific antibody fragments may bind taxine.7 There is no evidence, however, that cardioactive steroids are present in yew, and empiric use of antidigoxin Fab-fragments cannot be recommended. A single case report demonstrated that hemodialysis was ineffective in the removal of taxines, likely due to the toxin’s large volume of distribution.8 As a last resort, extracorporeal life support with membrane oxygenation is described favorably in two cases of yew berry poisoning refractory to conventional therapy.9,10

Case Conclusion

The patient’s ECGs showed a morphologically abnormal rhythm, possibly with a Brugada pattern, which are representative of the dysrhythmias caused by taxine’s inhibitory effects on the sodium and calcium channels. Despite an attempt at electrical cardioversion, the dysrhythmia persisted. He was given intravenous boluses of fluids and started on an amiodarone infusion. The patient’s BP gradually improved over the following 2 hours, and the dysrhythmia resolved with hemodynamic improvement. The amiodarone infusion was then discontinued, and he was admitted to the hospital for further testing. Echocardiography, electrophysiology studies, and cardiac catheterization were all normal. The absence of structural, dysrhythmogenic, and ischemic abnormalities supported the toxic etiology of his hemodynamic aberrations. He was discharged from the hospital 3 days later without report of sequelae.

Dr Nguyen is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 50-year-old man ingests two handfuls of small, red berries that he picked from a shrub in front of his apartment building, with the belief that they would have medicinal value. Two hours later, he developed abdominal cramping and vomited multiple times, followed shortly thereafter by profuse diaphoresis, lethargy, and ataxia. His concerned family brought him to the ED where his vital signs on presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 78/43 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 50 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 12 breaths/minute; temperature (T), 97.8°F. With the exception of bradycardia, the patient’s cardiac, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations were normal. His skin was diaphoretic, and he had no focal motor or sensory deficits or tremor. Initial laboratory values were: hemoglobin, 12.6 g/dL; sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 4.6 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 20 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 17 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.2 mg/dL; glucose, 288 mg/dL. The patient’s troponin I level was slightly elevated at 0.06 ng/mL; electrocardiogram (ECG) results are shown in Figure 1.

Why do plant poisonings occur?

There is the general belief that what is natural is not only healthful but also safe. This is clearly not true: cyanide, uranium, and king cobras are all natural but hardly safe. While most plants chosen for their purported medicinal properties are generally harmless in most patients when taken in low doses, there are plants that are sufficiently poisonous to be consequential with even relatively small exposures. Some people, often unknowingly vulnerable due to genetic or other causes, are uniquely susceptible to even minute doses.

Humans probably learned about plant toxicity early on—most likely the hard way. To this day, however, the Internet is replete with traditional and avant-garde natural healing remedies involving the use of naturally-derived plant products. These numerous bioactive compounds are often sold in plant form or as extracts, the latter being more concerning given their more concentrated formulation.

Plant misidentification is a common cause of poisoning, whether the intended use is for food or medicine. For example, some mistake “deadly nightshade” (Atropa belladonna) berries, which are deep blue, for blueberries, or pokeweed roots for horseradish roots due to their similar appearances.1

Alternatively, even when a plant is correctly identified, patients may experience adverse effects if they exceed the “therapeutic dose” (eg, dysrhythmia from aconite roots used in traditional Chinese medicine) or if the plant is improperly prepared (eg, hypoglycemia from consuming unripe ackee fruit).2 In addition, a toxic plant such as Jimson weed (Datura stramonium) or coca leaf extract may be intentionally ingested for its psychoactive hallucinatory effects.2 Although rare in the United States, in certain parts of Asia, persons intent on self-harm may consume toxic plants.1

When ingested, what plants cause bradycardia and hypotension, and why do these effects occur?

The two broad classes of plant-derived toxins that can cause these findings are cardioactive steroids and sodium channel active agents.

Cardioactive Steroids

There are numerous botanical sources of cardioactive steroids (sometimes called cardiac glycosides) such as Digitalis lanata, from which digoxin is derived; and Digitalis purpurea, the source of digitoxin. Poisoning by Digitalis spp, squill, lily of the valley, oleander, yellow oleander, and Cerbera manghas are clinically similar. Cardioactive steroids act pharmacologically to block the sodium-potassium ATPase pump on the myocardial cell membrane. This in turn increases intracellular sodium, which subsequently inhibits the exchange of extracellular sodium for intracellular calcium, leading to inotropy. Clinical manifestations of toxicity include nausea, vomiting, hyperkalemia, bradycardia, cardiac dysrhythmias, and occasionally hypotension—some of which can be life-threatening.

Sodium Channel Active Agents

Several plant toxins affect the flow of sodium by blocking or activating the sodium channel. Both effects alter the rate and strength of cardiac contraction, causing cardiac dysrhythmias.

Aconite is often used in traditional Chinese medicine. In North America, it is mainly derived from Aconitinum napellus, commonly called monkshood, helmet flower, or wolfsbane. It effectively holds open the voltage-dependent sodium channel, increasing cellular excitability. By prolonging the sodium current influx, neuronal and cardiac repolarization eventually slow due to sodium overload, leading to bradycardia and hypotension, as well as neurological effects. Its cardiotoxicity resembles that caused by cardiac glycosides, though a history of paresthesias or muscle weakness may help to differentiate the two toxins.

Veratrum spp include false hellebore, Indian poke, and California hellebore. These plants are occasionally mistaken for leeks (ramps) and can cause vomiting, bradycardia, and hypotension by a mechanism of action similar to aconitine.

Grayanotoxins, a group of diterpenoid toxins found in death camas, azalea, Rhododendron spp, and mountain laurel, can become concentrated in honey made from these plants. Depending on the specific toxin, they variably open or close the sodium channel. In addition to causing bradycardia and hypotension, patients may exhibit mental status changes (“mad honey” poisoning) and seizures.2

Case Continuation

After rapid infusion of 1-liter of normal saline, the patient’s BP was 80/63 mm Hg and HR was 52 beats/minute. His wife arrived to the ED 30-minutes later with a plastic bag containing the red berries the patient had ingested. The emergency physician identified them as Taxus baccata, or more commonly, yew berries. The patient stated that he ingested both the red fleshy aril and chewed the hard central seed.

How is cardiotoxicity from yew berries treated?

Within hours of ingestion, toxicity progresses from nausea, abdominal pain, paresthesias, and ataxia, to bradycardia, cardiac conduction delays, wide-complex ventricular dysrhythmias and mental status changes.3 Although toxicity of Taxus has been known since antiquity, no antidote exists. Ventricular dysrhythmias causing hemodynamic instability should be electrically cardioverted, although there is no evidence to support the safety or efficacy of such therapy. Since the serum, and therefore cardiac concentration of taxine will be identical after cardioversion to its value prior, recurrent dysrhythmias are common.1 Sodium bicarbonate has been inconsistently effective in the treatment of wide-complex tachydysrhythmias,4 but its use seems counterintuitive for most cases. There may be merit to raising the sodium gradient on an already sodium overloaded myocyte, but short-term gain may lead to unintended consequences. Success with antidysrhythmics has been limited: although amiodarone is often used to treat wide-complex tachydysrhythmias, its efficacy in Taxus toxicity has been conflicting.4-6

There have been a few reported cases of yew alkaloid crossreactivity with digoxin assays, suggesting that digoxin-specific antibody fragments may bind taxine.7 There is no evidence, however, that cardioactive steroids are present in yew, and empiric use of antidigoxin Fab-fragments cannot be recommended. A single case report demonstrated that hemodialysis was ineffective in the removal of taxines, likely due to the toxin’s large volume of distribution.8 As a last resort, extracorporeal life support with membrane oxygenation is described favorably in two cases of yew berry poisoning refractory to conventional therapy.9,10

Case Conclusion

The patient’s ECGs showed a morphologically abnormal rhythm, possibly with a Brugada pattern, which are representative of the dysrhythmias caused by taxine’s inhibitory effects on the sodium and calcium channels. Despite an attempt at electrical cardioversion, the dysrhythmia persisted. He was given intravenous boluses of fluids and started on an amiodarone infusion. The patient’s BP gradually improved over the following 2 hours, and the dysrhythmia resolved with hemodynamic improvement. The amiodarone infusion was then discontinued, and he was admitted to the hospital for further testing. Echocardiography, electrophysiology studies, and cardiac catheterization were all normal. The absence of structural, dysrhythmogenic, and ischemic abnormalities supported the toxic etiology of his hemodynamic aberrations. He was discharged from the hospital 3 days later without report of sequelae.

Dr Nguyen is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Bruneton J. Toxic Plants; Dangerous to Humans and Animals. Paris, France: Lavoisier Publishing; 1999:4-752.

- Palmer ME, Betz JM. Plants. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE. In: Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2010:1537-1560.

- Nelson LS, Shih RD, Balick MJ. Handbook of Poisonous and Injurious Plants. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer/New York Botanical Garden; 2007:288-290.

- Pierog J, Kane B, Kane K, Donovan JW. Management of isolated yew berry toxicity with sodium bicarbonate: a case report in treatment efficacy. J Med Toxicol. 2009;5(2):84-89.

- Jones R, Jones J, Causer J, Ewins D, Goenka N, Joseph F. Yew tree poisoning: a near-fatal lesson from history. Clin Med. 2011;11(2):173-175.

- Willaert W, Claessens P, Vankelecom B, Vanderheyden M. Intoxication with Taxus baccata: cardiac arrhythmias following yew leaves ingestion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(4 Pt 1):511,512.

- Cummins RO, Haulman J, Quan L, Graves JR, Peterson D, Horan S. Near-fatal yew berry intoxication treated with external cardiac pacing and digoxin-specific FAB antibody fragments. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(1):38-43

- Dahlqvist M, Venzin R, König S, et al. Haemodialysis in Taxus baccata poisoning: a case report. QJM. 2012;105(4):359-361.

- Panzeri C, Bacis G, Ferri F, et al. Extracorporeal life support in severe Taxus baccata poisoning. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48(5):463-465.

- Soumagne N, Chauvet S, Chatellier D, Robert R, Charrière JM, Menu P. Treatment of yew leaf intoxication with extracorporeal circulation. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(3):354.e5-6.

- Bruneton J. Toxic Plants; Dangerous to Humans and Animals. Paris, France: Lavoisier Publishing; 1999:4-752.

- Palmer ME, Betz JM. Plants. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE. In: Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2010:1537-1560.

- Nelson LS, Shih RD, Balick MJ. Handbook of Poisonous and Injurious Plants. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer/New York Botanical Garden; 2007:288-290.

- Pierog J, Kane B, Kane K, Donovan JW. Management of isolated yew berry toxicity with sodium bicarbonate: a case report in treatment efficacy. J Med Toxicol. 2009;5(2):84-89.

- Jones R, Jones J, Causer J, Ewins D, Goenka N, Joseph F. Yew tree poisoning: a near-fatal lesson from history. Clin Med. 2011;11(2):173-175.

- Willaert W, Claessens P, Vankelecom B, Vanderheyden M. Intoxication with Taxus baccata: cardiac arrhythmias following yew leaves ingestion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(4 Pt 1):511,512.

- Cummins RO, Haulman J, Quan L, Graves JR, Peterson D, Horan S. Near-fatal yew berry intoxication treated with external cardiac pacing and digoxin-specific FAB antibody fragments. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(1):38-43

- Dahlqvist M, Venzin R, König S, et al. Haemodialysis in Taxus baccata poisoning: a case report. QJM. 2012;105(4):359-361.

- Panzeri C, Bacis G, Ferri F, et al. Extracorporeal life support in severe Taxus baccata poisoning. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48(5):463-465.

- Soumagne N, Chauvet S, Chatellier D, Robert R, Charrière JM, Menu P. Treatment of yew leaf intoxication with extracorporeal circulation. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(3):354.e5-6.

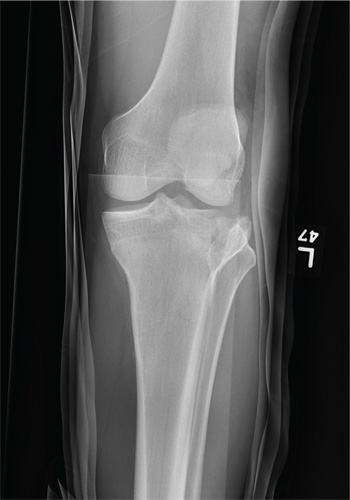

Clipped by an Oncoming Car

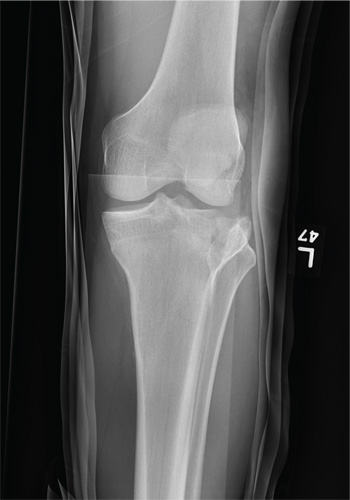

A 23-year-old man is brought in after being hit by a car. He was in the process of getting into his car when another vehicle coming from the opposite direction swerved into his lane. He tried to jump onto his hood to avoid the other car but was struck by the side mirror and landed on the ground. He is primarily complaining of left knee and lower leg pain. He denies any medical history. Primary survey appears to be stable except for scalp and facial lacerations. The patient is awake, alert, and oriented, and his vital signs are stable. His left lower extremity is in a splint immobilizer, placed by emergency medical personnel. There is a moderate amount of soft tissue swelling around the knee, which is exquisitely tender to palpation. The patient has limited flexion and extension of the knee due to pain. He is able to wiggle his toes, and distally in the leg and foot there appears to be no neurovascular compromise. Radiographs of the tibia are obtained. What is your impression?

Man, 26, With Sudden-Onset Right Lower Quadrant Pain

A 26-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. After triage was complete, he was transported to an examination room, where the clinician obtained the history of presenting illness. The onset of pain was approximately 90 minutes prior to arrival at the ED and woke the patient from a “sound sleep.” He stated that the pain initially started as a “3 out of 10” but had progressed to a “12 out of 10,” and he described it as being in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen, with radiation to his right testicle. However, he was unsure where the pain started or if it was worse in either location. Nausea was the primary associated symptom, but he denied vomiting, diarrhea, fever, dysuria, or hematuria. Last, the patient denied history of trauma.

Medical history was noncontributory: He denied previous gastrointestinal diseases, and there was no history of renal stones, urinary tract infection, or any other genitourinary disease. He had no surgical history. The patient smoked less than a pack of cigarettes per day but denied alcohol or drug use.

Physical examination revealed a young man in moderate discomfort. Despite describing his pain as a “12 out of 10,” he had a blood pressure of 121/72 mm Hg; pulse, 59 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 96.8°F. HEENT and cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and neurologic exam results were all within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed a mildly tender right lower quadrant with deep palpation, but no rebound or guarding. Murphy sign was negative.

Because of the complaint of pain radiating to the testicles, a genitourinary examination was performed. The penis appeared unremarkable, with no lesions or discharge. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. The scrotum appeared appropriate in size and was also grossly unremarkable. The left testicle was nontender. However, palpation of the right testicle elicited moderate to severe pain. There was no visible swelling, and there were no palpable hernias or other masses. Cremasteric reflex was assessed bilaterally and deemed to be absent on the right side.

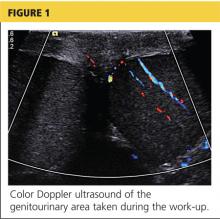

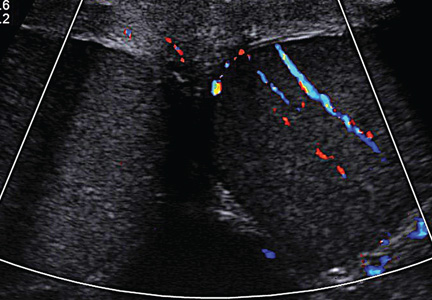

A workup was initiated that included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and urinalysis; the results of these tests were unremarkable. A differential diagnosis was formed, with emphasis on appendicitis and testicular torsion. Because of the specific nature and location of the pain, both ultrasound and CT of the abdomen/pelvis were considered. It was decided to order the ultrasound, with a plan to perform CT only if ultrasound was unremarkable. The patient was medicated for his pain and the ultrasound commenced. Halfway through the imaging, the clinician and attending physician were summoned to the examination room to review the image seen in Figure 1.

On the next page: Discussion and diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Testicular torsion may occur if the testicle twists or rotates on the spermatic cord. The twisting causes arterial ischemia and venous outflow obstruction, cutting off the testicle’s blood supply.1,2 Torsion may be extravaginal or intravaginal, depending on the extent of involvement of the surrounding structures.2

Extravaginal torsion is most commonly seen in neonates and occurs because the entire testicle may freely rotate prior to fixation to the scrotal wall via the tunica vaginalis.2Intravaginal torsion is more common in adolescents and often occurs as a result of a condition known as bell clapper deformity. This congenital abnormality enables the testicle to rotate within the tunica vaginalis and rest transversely in the scrotum instead of in a more vertical orientation.2,3 Torsion occurs if the testicle rotates 90° to 180°, with complete torsion occurring at 360° (torsion may extend to as much as 720°).2 Torsion may also occur as a result of trauma.1

Peak incidence of testicular torsion occurs at ages 13 to 14, but it can occur at any age; torsion affects approximately 1 in 4,000 males younger than 25.2-5 Ninety-five percent of all torsions are intravaginal.2 Torsion is the most common pathology for males who undergo surgical exploration for scrotal pain.3

The main goal in the diagnosis and treatment of torsion is testicular salvage. Torsion is considered a urologic emergency, making early diagnosis and treatment critical to prevent testicular loss. In fact, a review of the relevant literature reveals that the rate of testicular salvage is much higher if the diagnosis is made within 6 to 12 hours.1,2,5 Potential sequelae from delayed treatment include testicular infarction, loss of testicle, infertility problems, infections, cosmetic deformity, and increased risk for testicular malignancy.2

Because many men hesitate to seek medical attention for symptoms of testicular pain and swelling, the primary care clinician should openly discuss testicular disorders, especially with preadolescent males, during testicular examinations.6

Diagnosis

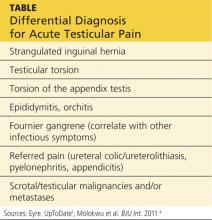

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. The cremasteric reflex should be assessed because it can help differentiate among the causes of testicular pain.7 It is performed by gently stroking the upper inner thigh and observing for contraction of the ipsilateral testicle. One study found that, in cases of torsion, the absence of a cremasteric reflex had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 88%.7 See the Table for the differential diagnosis for acute testicular pain.

While it is often possible to make the diagnosis of testicular torsion clinically, ultrasound with color Doppler is the diagnostic test of choice in cases for which the cause of acute scrotal pain is unclear.8 Ultrasound provides anatomic detail of the scrotum and its contents, and perfusion is assessed by adding the color Doppler images.8 It is important to note that, while the absence of blood flow is considered diagnostic for testicular torsion, the presence of flow does not necessarily exclude it.4

On the next page: Treatment >>

Treatment

Surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and orchiopexy (fixation of the testicle to the scrotal wall) is the mainstay of treatment for testicular torsion.1 Orchiopexy is often performed bilaterally in order to prevent future torsion of the unaffected testicle. In about 40% of males with the bell clapper deformity, the condition is present on both sides.2 Orchiectomy, the complete removal of the testicle, is necessary when the degree of torsion and subsequent ischemia have caused irreversible damage to the testicle.6 In one study in which 2,248 cases of torsion were reviewed, approximately 34% of males required orchiectomy.6

If surgery may be delayed, the clinician may attempt manual detorsion at the bedside. Despite the “open book” method described in many texts—which instructs the practitioner to rotate the testicle laterally—a review of the literature reveals that torsion takes place medially only 70% of the time.1,5 The clinician should always consider this when any attempts at manual detorsion are made and correlate his or her technique with physical examination and the patient’s response.5

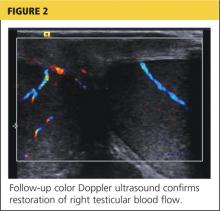

Relief of pain and return of the testicle to its natural longitudinal lie are considered indicators of successful detorsion.1 Color Doppler ultrasound should be used to confirm the return of circulation. However, in one case review of pediatric patients who underwent surgical exploration after manual detorsion, some degree of residual torsion remained in 32%.5 Because of this risk, surgery is still indicated even in cases of successful bedside detorsion.5

On the next page: Case continuation >>

CASE CONTINUATION

The decision to perform bedside ultrasound was made because the diagnosis of testicular torsion is a surgical emergency, and the window of time to prevent complications can be extremely narrow. If the ultrasound had been normal, then a CT scan may have provided additional data on which to base the diagnosis.

The patient was given adequate parenteral pain medication. After color Doppler ultrasound confirmed the torsion, the testicle was laterally rotated approximately 360°. The patient reported alleviation of his symptoms. Color Doppler was again performed to confirm the return of hyperemic blood flow to the affected testicle (Figure 2). The urologist arrived shortly thereafter and the patient was taken to the operating room, where he underwent scrotal exploration and bilateral orchiopexy.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. Testicular torsion is most commonly seen in infants and adolescents but can occur at any age. The condition is a surgical emergency and the goal is testicular salvage, which is most likely to occur before 12 hours have elapsed since the onset of symptoms. An important component of the physical examination is attempting to elicit the cremasteric reflex, which is likely to be absent in the presence of torsion.

The primary care provider’s goal is to rapidly diagnose testicular torsion, then refer the patient immediately to a urologist or ED. The skilled clinician may attempt manual detorsion, based on his/her expertise and comfort level; however, this procedure should never delay prompt surgical intervention.

REFERENCES

1. Eyre RC. Evaluation of the acute scrotum in adults. www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-the-acute-scrotum-in-adults. Accessed May 16, 2014.

2. Ogunyemi OI, Weiker M, Abel EJ. Testicular torsion. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2036003-overview. Accessed May 16, 2014.

3. Khan F, Muoka O, Watson GM. Bell clapper testis, torsion, and detorsion: a case report. Case Rep Urol. 2011;2011:631970.

4. Molokwu CN, Somani BK, Goodman CM. Outcomes of scrotal exploration for acute scrotal pain suspicious of testicular torsion: a consecutive case series of 173 patients. BJU Int. 2011;107(6):990-993.

5. Sessions AE, Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC, et al. Testicular torsion: direction, degree, duration and disinformation. J Urol. 2003;169(2):663-665.

6. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1167-1171.

7. Schmitz D, Safranek S. How useful is a physical exam in diagnosing testicular torsion? J Fam Pract. 2009;58(8):433-434.

8. D’Andrea A, Coppolino F, Cesarano E, et al. US in the assessment of acute scrotum. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(suppl 1):S8. www.criticalultrasound journal.com/content/5/S1/S8/. Accessed May 16, 2014.

A 26-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. After triage was complete, he was transported to an examination room, where the clinician obtained the history of presenting illness. The onset of pain was approximately 90 minutes prior to arrival at the ED and woke the patient from a “sound sleep.” He stated that the pain initially started as a “3 out of 10” but had progressed to a “12 out of 10,” and he described it as being in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen, with radiation to his right testicle. However, he was unsure where the pain started or if it was worse in either location. Nausea was the primary associated symptom, but he denied vomiting, diarrhea, fever, dysuria, or hematuria. Last, the patient denied history of trauma.

Medical history was noncontributory: He denied previous gastrointestinal diseases, and there was no history of renal stones, urinary tract infection, or any other genitourinary disease. He had no surgical history. The patient smoked less than a pack of cigarettes per day but denied alcohol or drug use.

Physical examination revealed a young man in moderate discomfort. Despite describing his pain as a “12 out of 10,” he had a blood pressure of 121/72 mm Hg; pulse, 59 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 96.8°F. HEENT and cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and neurologic exam results were all within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed a mildly tender right lower quadrant with deep palpation, but no rebound or guarding. Murphy sign was negative.

Because of the complaint of pain radiating to the testicles, a genitourinary examination was performed. The penis appeared unremarkable, with no lesions or discharge. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. The scrotum appeared appropriate in size and was also grossly unremarkable. The left testicle was nontender. However, palpation of the right testicle elicited moderate to severe pain. There was no visible swelling, and there were no palpable hernias or other masses. Cremasteric reflex was assessed bilaterally and deemed to be absent on the right side.

A workup was initiated that included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and urinalysis; the results of these tests were unremarkable. A differential diagnosis was formed, with emphasis on appendicitis and testicular torsion. Because of the specific nature and location of the pain, both ultrasound and CT of the abdomen/pelvis were considered. It was decided to order the ultrasound, with a plan to perform CT only if ultrasound was unremarkable. The patient was medicated for his pain and the ultrasound commenced. Halfway through the imaging, the clinician and attending physician were summoned to the examination room to review the image seen in Figure 1.

On the next page: Discussion and diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Testicular torsion may occur if the testicle twists or rotates on the spermatic cord. The twisting causes arterial ischemia and venous outflow obstruction, cutting off the testicle’s blood supply.1,2 Torsion may be extravaginal or intravaginal, depending on the extent of involvement of the surrounding structures.2

Extravaginal torsion is most commonly seen in neonates and occurs because the entire testicle may freely rotate prior to fixation to the scrotal wall via the tunica vaginalis.2Intravaginal torsion is more common in adolescents and often occurs as a result of a condition known as bell clapper deformity. This congenital abnormality enables the testicle to rotate within the tunica vaginalis and rest transversely in the scrotum instead of in a more vertical orientation.2,3 Torsion occurs if the testicle rotates 90° to 180°, with complete torsion occurring at 360° (torsion may extend to as much as 720°).2 Torsion may also occur as a result of trauma.1

Peak incidence of testicular torsion occurs at ages 13 to 14, but it can occur at any age; torsion affects approximately 1 in 4,000 males younger than 25.2-5 Ninety-five percent of all torsions are intravaginal.2 Torsion is the most common pathology for males who undergo surgical exploration for scrotal pain.3

The main goal in the diagnosis and treatment of torsion is testicular salvage. Torsion is considered a urologic emergency, making early diagnosis and treatment critical to prevent testicular loss. In fact, a review of the relevant literature reveals that the rate of testicular salvage is much higher if the diagnosis is made within 6 to 12 hours.1,2,5 Potential sequelae from delayed treatment include testicular infarction, loss of testicle, infertility problems, infections, cosmetic deformity, and increased risk for testicular malignancy.2

Because many men hesitate to seek medical attention for symptoms of testicular pain and swelling, the primary care clinician should openly discuss testicular disorders, especially with preadolescent males, during testicular examinations.6

Diagnosis

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. The cremasteric reflex should be assessed because it can help differentiate among the causes of testicular pain.7 It is performed by gently stroking the upper inner thigh and observing for contraction of the ipsilateral testicle. One study found that, in cases of torsion, the absence of a cremasteric reflex had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 88%.7 See the Table for the differential diagnosis for acute testicular pain.

While it is often possible to make the diagnosis of testicular torsion clinically, ultrasound with color Doppler is the diagnostic test of choice in cases for which the cause of acute scrotal pain is unclear.8 Ultrasound provides anatomic detail of the scrotum and its contents, and perfusion is assessed by adding the color Doppler images.8 It is important to note that, while the absence of blood flow is considered diagnostic for testicular torsion, the presence of flow does not necessarily exclude it.4

On the next page: Treatment >>

Treatment

Surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and orchiopexy (fixation of the testicle to the scrotal wall) is the mainstay of treatment for testicular torsion.1 Orchiopexy is often performed bilaterally in order to prevent future torsion of the unaffected testicle. In about 40% of males with the bell clapper deformity, the condition is present on both sides.2 Orchiectomy, the complete removal of the testicle, is necessary when the degree of torsion and subsequent ischemia have caused irreversible damage to the testicle.6 In one study in which 2,248 cases of torsion were reviewed, approximately 34% of males required orchiectomy.6

If surgery may be delayed, the clinician may attempt manual detorsion at the bedside. Despite the “open book” method described in many texts—which instructs the practitioner to rotate the testicle laterally—a review of the literature reveals that torsion takes place medially only 70% of the time.1,5 The clinician should always consider this when any attempts at manual detorsion are made and correlate his or her technique with physical examination and the patient’s response.5