User login

Case

A 12-year-old boy presented to the ED via emergency medical services after he was struck by motor vehicle while skateboarding without a helmet or other safety equipment. He was thrown approximately 10 feet, but experienced no loss of consciousness, pain, or active bleeding at the site of the accident. Unaccompanied by family, he arrived to the ED fully immobilized on a long back board. His field vital signs were stable: blood pressure (BP), 100/65 mm Hg; heart rate (HR) 105 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 22 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. The patient had an estimated Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 14, with one point removed due to confusion.

Primary examination showed an intact airway with equal breath sounds bilaterally, and pulses were equal in all extremities with audible heart sounds. The patient was able to move all extremities, and showed no obvious deformities or bleeding. He was neurologically intact, with equal strength and sensation. He did, however, elicit some confusion during the examination, continuously stating it was “all his fault” and asking the medical staff where he was. This confusion persisted even after repeated reorientation. His vital signs remained stable, with slight tachycardia (BP, 105/67 mm hg; HR 100 beats/minute; RR, 17 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile; pulse oxygen saturation, 99%). An abbreviated history revealed no allergies, medications, or past medical history. When questioned, the patient had no recollection of the accident or the last time he had eaten.

A secondary survey was significant for a small contusion/abrasion on the patient’s forehead but an otherwise normal head, ear, eyes, nose, and throat examination and no cervical c-spine tenderness. The patient denied any chest wall tenderness, but there was a dramatic palpable defect in the right chest wall, with profound asymmetry when compared to the left chest wall. No sharp, bony edges could be palpated, nor could any crepitance be felt. Breath sounds were reexamined and remained equal and nonlabored, and the patient continued to have a stable oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. The rest of the secondary survey was negative, and c-spine, pelvic, and portable chest X-rays were all negative for acute findings.

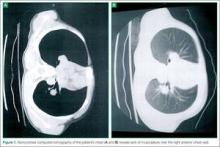

Due to the physical examination findings on the chest wall, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was performed with contrast (Figure). The chest CT was normal, except for a lack of musculature over the right anterior chest wall. The patient’s mother arrived shortly after imaging studies, at which time he was reexamined. When interviewing his mother for further history, she stated that her son had been diagnosed with mild Poland Syndrome as a child, and that he has always had a chest deformity. All other studies, including a noncontrast CT of the brain, were normal. The child quickly improved during his 6-hour observation in the ED, and he was subsequently discharged home with the diagnosis of a concussion.

Discussion

Poland syndrome, also known as hand and ipsilateral thorax syndrome, is a rare congenital disorder with unknown etiology.1,2 The condition was first officially described in 1841 by Alfred Poland at Guy’s Hospital in London, though reports exist as early as 1826. Poland, a medical student, made the discovery while examining the cadaver of a hanged convict.

The occurrence of Poland syndrome is estimated to be from 1 in 25,000 to 1 in 75,000 to 100,000 by some reports,1-4 with a higher incidence in males than females (3:1 ratio) and 75% right-sided dominance.2 The syndrome is primarily described as unilateral, but there is one case report of suspected bilateral involvement.1 The components of the syndrome consist of aplasia of the sternal head of the pectoralis major muscle, hypoplasia of the pectoralis minor muscle, decreased development of breast and subcutaneous tissue, and a variety of ipsilateral hand abnormalities, including shortened carpels and phalanges, and syndactyly. The syndrome is quite variable, with different individuals eliciting combinations of the above components.

Poland syndrome was initially believed to be a nonfamilial disorder due to its sporadic nature, as illustrated by a case report of an isolated affected identical twin.3 However, enough cases of familial involvement have been reported that there is a proposed theory of an inheritable trait. Although over 250 patients with this syndrome have been described, there is no clear cause.2 The current theory of etiology is felt to be due to a lack of blood flow in the subclavian artery, or one of its branches, early in the development of the fetus, around the end of the sixth week of development. Individuals can have mild to severe manifestations, ranging as mild (eg, only pectoralis involvement), to severe (eg, rib hypoplasia, complete absence of ipsilateral hand, dextrocardia, lung herniation). Case reports of high functioning athletes with the disorder show that there is not necessarily functional impairment.

In addition to Poland syndrome, there are a number of congenital abnormalities that can also mimic traumatic chest injuries. Historically, surgeons have classified congenital wall deformities into one of five categories: Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum, sternal clefts, and generic skeletal and cartilage dysplasias (eg, absent ribs, rib torsion, vertebral anomalies).5-7 Of these categories, Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, and some skeletal dysplasias cause anterior chest wall depression.5,6 Although these are examples of congenital thoracic wall abnormalities, one must also remember postoperative changes, which may also appear to be traumatic in origin. Examples of specific procedures are lumpectomy, mastectomy, rib resection, lung resection, or even cardiac surgery—all of which can alter the physical findings of the chest wall.

Conclusion

This report is an interesting case of an impaired patient presenting to the ED after a traumatic incident and unable to describe a past medical history of a congenital disorder. Although the patient was high functioning, as exemplified by his ability to complete normal adolescent activities such as skateboarding, he had a significant physical finding which appeared to correspond to the mechanism of his injury. He was initially thought to have a significant injury involving his chest wall, since secondary examination revealed a palpable defect. Although the patient was oxygenating well, and in no apparent distress, his altered mental status raised concerns about the accuracy of his report, with confusion and perseveration.

When a rare congenital abnormality imitates a traumatic condition, merely having the name of the condition—as we did when the family arrived—does not necessarily rule out the absence of a related deficit or injury. To better differentiate acute from preexisting physical deformities or deficits, one must gather and process multiple diagnostic clues. This is best accomplished by combining the presence or absence of symptoms (in this case, pain, dyspnea, or hemoptysis), physical examination findings (eg, ecchymosis, crepitance, flail segment), and supportive diagnostic tests (radiographs, CT, and echocardiograms). This approach will systematically eliminate or suggest acute traumatic diagnoses. With specific traumatic causes such as rib fracture, pneumothorax, or pulmonary contusion eliminated, one can expand the (nontraumatic) differential, keeping in mind the possibility of a congenital disorder.

Dr Martin is an emergency physician at Emergency Medical Associates of NY and NJ; and emergency medicine education director, Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ.

Dr Martin reports no conflict of interest or financial arrangements.

- Fokin AA, Robicsek F. Poland syndrome revisited. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(6):2218-2225

- Darian VB, Argenta LC, Pasyk KA. Familial Poland’s syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;23(6):531-537

- Stevens D, Fink B, Prevel C. Poland’s syndrome in one identical twin. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(3):392-395.

- McGrath MH, Pomerantz J. Plastic surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1935

- Spear SL, Pelletiere CV, Lee ES, Grotting JC. Anterior thoracic hypoplasia: a separate entity from Poland syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(1):

- Hodgkinson, DJ. Chest wall implants: their use for pectus excavatum, pectoralis muscle tears, Poland’s syndrome, and muscular insufficiency. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21(1):7-15.

- Hodgkinson, DJ. The management of anterior chest wall deformity in patients presenting for breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(5): 1714-1723.

Case

A 12-year-old boy presented to the ED via emergency medical services after he was struck by motor vehicle while skateboarding without a helmet or other safety equipment. He was thrown approximately 10 feet, but experienced no loss of consciousness, pain, or active bleeding at the site of the accident. Unaccompanied by family, he arrived to the ED fully immobilized on a long back board. His field vital signs were stable: blood pressure (BP), 100/65 mm Hg; heart rate (HR) 105 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 22 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. The patient had an estimated Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 14, with one point removed due to confusion.

Primary examination showed an intact airway with equal breath sounds bilaterally, and pulses were equal in all extremities with audible heart sounds. The patient was able to move all extremities, and showed no obvious deformities or bleeding. He was neurologically intact, with equal strength and sensation. He did, however, elicit some confusion during the examination, continuously stating it was “all his fault” and asking the medical staff where he was. This confusion persisted even after repeated reorientation. His vital signs remained stable, with slight tachycardia (BP, 105/67 mm hg; HR 100 beats/minute; RR, 17 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile; pulse oxygen saturation, 99%). An abbreviated history revealed no allergies, medications, or past medical history. When questioned, the patient had no recollection of the accident or the last time he had eaten.

A secondary survey was significant for a small contusion/abrasion on the patient’s forehead but an otherwise normal head, ear, eyes, nose, and throat examination and no cervical c-spine tenderness. The patient denied any chest wall tenderness, but there was a dramatic palpable defect in the right chest wall, with profound asymmetry when compared to the left chest wall. No sharp, bony edges could be palpated, nor could any crepitance be felt. Breath sounds were reexamined and remained equal and nonlabored, and the patient continued to have a stable oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. The rest of the secondary survey was negative, and c-spine, pelvic, and portable chest X-rays were all negative for acute findings.

Due to the physical examination findings on the chest wall, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was performed with contrast (Figure). The chest CT was normal, except for a lack of musculature over the right anterior chest wall. The patient’s mother arrived shortly after imaging studies, at which time he was reexamined. When interviewing his mother for further history, she stated that her son had been diagnosed with mild Poland Syndrome as a child, and that he has always had a chest deformity. All other studies, including a noncontrast CT of the brain, were normal. The child quickly improved during his 6-hour observation in the ED, and he was subsequently discharged home with the diagnosis of a concussion.

Discussion

Poland syndrome, also known as hand and ipsilateral thorax syndrome, is a rare congenital disorder with unknown etiology.1,2 The condition was first officially described in 1841 by Alfred Poland at Guy’s Hospital in London, though reports exist as early as 1826. Poland, a medical student, made the discovery while examining the cadaver of a hanged convict.

The occurrence of Poland syndrome is estimated to be from 1 in 25,000 to 1 in 75,000 to 100,000 by some reports,1-4 with a higher incidence in males than females (3:1 ratio) and 75% right-sided dominance.2 The syndrome is primarily described as unilateral, but there is one case report of suspected bilateral involvement.1 The components of the syndrome consist of aplasia of the sternal head of the pectoralis major muscle, hypoplasia of the pectoralis minor muscle, decreased development of breast and subcutaneous tissue, and a variety of ipsilateral hand abnormalities, including shortened carpels and phalanges, and syndactyly. The syndrome is quite variable, with different individuals eliciting combinations of the above components.

Poland syndrome was initially believed to be a nonfamilial disorder due to its sporadic nature, as illustrated by a case report of an isolated affected identical twin.3 However, enough cases of familial involvement have been reported that there is a proposed theory of an inheritable trait. Although over 250 patients with this syndrome have been described, there is no clear cause.2 The current theory of etiology is felt to be due to a lack of blood flow in the subclavian artery, or one of its branches, early in the development of the fetus, around the end of the sixth week of development. Individuals can have mild to severe manifestations, ranging as mild (eg, only pectoralis involvement), to severe (eg, rib hypoplasia, complete absence of ipsilateral hand, dextrocardia, lung herniation). Case reports of high functioning athletes with the disorder show that there is not necessarily functional impairment.

In addition to Poland syndrome, there are a number of congenital abnormalities that can also mimic traumatic chest injuries. Historically, surgeons have classified congenital wall deformities into one of five categories: Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum, sternal clefts, and generic skeletal and cartilage dysplasias (eg, absent ribs, rib torsion, vertebral anomalies).5-7 Of these categories, Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, and some skeletal dysplasias cause anterior chest wall depression.5,6 Although these are examples of congenital thoracic wall abnormalities, one must also remember postoperative changes, which may also appear to be traumatic in origin. Examples of specific procedures are lumpectomy, mastectomy, rib resection, lung resection, or even cardiac surgery—all of which can alter the physical findings of the chest wall.

Conclusion

This report is an interesting case of an impaired patient presenting to the ED after a traumatic incident and unable to describe a past medical history of a congenital disorder. Although the patient was high functioning, as exemplified by his ability to complete normal adolescent activities such as skateboarding, he had a significant physical finding which appeared to correspond to the mechanism of his injury. He was initially thought to have a significant injury involving his chest wall, since secondary examination revealed a palpable defect. Although the patient was oxygenating well, and in no apparent distress, his altered mental status raised concerns about the accuracy of his report, with confusion and perseveration.

When a rare congenital abnormality imitates a traumatic condition, merely having the name of the condition—as we did when the family arrived—does not necessarily rule out the absence of a related deficit or injury. To better differentiate acute from preexisting physical deformities or deficits, one must gather and process multiple diagnostic clues. This is best accomplished by combining the presence or absence of symptoms (in this case, pain, dyspnea, or hemoptysis), physical examination findings (eg, ecchymosis, crepitance, flail segment), and supportive diagnostic tests (radiographs, CT, and echocardiograms). This approach will systematically eliminate or suggest acute traumatic diagnoses. With specific traumatic causes such as rib fracture, pneumothorax, or pulmonary contusion eliminated, one can expand the (nontraumatic) differential, keeping in mind the possibility of a congenital disorder.

Dr Martin is an emergency physician at Emergency Medical Associates of NY and NJ; and emergency medicine education director, Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ.

Dr Martin reports no conflict of interest or financial arrangements.

Case

A 12-year-old boy presented to the ED via emergency medical services after he was struck by motor vehicle while skateboarding without a helmet or other safety equipment. He was thrown approximately 10 feet, but experienced no loss of consciousness, pain, or active bleeding at the site of the accident. Unaccompanied by family, he arrived to the ED fully immobilized on a long back board. His field vital signs were stable: blood pressure (BP), 100/65 mm Hg; heart rate (HR) 105 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 22 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. The patient had an estimated Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 14, with one point removed due to confusion.

Primary examination showed an intact airway with equal breath sounds bilaterally, and pulses were equal in all extremities with audible heart sounds. The patient was able to move all extremities, and showed no obvious deformities or bleeding. He was neurologically intact, with equal strength and sensation. He did, however, elicit some confusion during the examination, continuously stating it was “all his fault” and asking the medical staff where he was. This confusion persisted even after repeated reorientation. His vital signs remained stable, with slight tachycardia (BP, 105/67 mm hg; HR 100 beats/minute; RR, 17 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile; pulse oxygen saturation, 99%). An abbreviated history revealed no allergies, medications, or past medical history. When questioned, the patient had no recollection of the accident or the last time he had eaten.

A secondary survey was significant for a small contusion/abrasion on the patient’s forehead but an otherwise normal head, ear, eyes, nose, and throat examination and no cervical c-spine tenderness. The patient denied any chest wall tenderness, but there was a dramatic palpable defect in the right chest wall, with profound asymmetry when compared to the left chest wall. No sharp, bony edges could be palpated, nor could any crepitance be felt. Breath sounds were reexamined and remained equal and nonlabored, and the patient continued to have a stable oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. The rest of the secondary survey was negative, and c-spine, pelvic, and portable chest X-rays were all negative for acute findings.

Due to the physical examination findings on the chest wall, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was performed with contrast (Figure). The chest CT was normal, except for a lack of musculature over the right anterior chest wall. The patient’s mother arrived shortly after imaging studies, at which time he was reexamined. When interviewing his mother for further history, she stated that her son had been diagnosed with mild Poland Syndrome as a child, and that he has always had a chest deformity. All other studies, including a noncontrast CT of the brain, were normal. The child quickly improved during his 6-hour observation in the ED, and he was subsequently discharged home with the diagnosis of a concussion.

Discussion

Poland syndrome, also known as hand and ipsilateral thorax syndrome, is a rare congenital disorder with unknown etiology.1,2 The condition was first officially described in 1841 by Alfred Poland at Guy’s Hospital in London, though reports exist as early as 1826. Poland, a medical student, made the discovery while examining the cadaver of a hanged convict.

The occurrence of Poland syndrome is estimated to be from 1 in 25,000 to 1 in 75,000 to 100,000 by some reports,1-4 with a higher incidence in males than females (3:1 ratio) and 75% right-sided dominance.2 The syndrome is primarily described as unilateral, but there is one case report of suspected bilateral involvement.1 The components of the syndrome consist of aplasia of the sternal head of the pectoralis major muscle, hypoplasia of the pectoralis minor muscle, decreased development of breast and subcutaneous tissue, and a variety of ipsilateral hand abnormalities, including shortened carpels and phalanges, and syndactyly. The syndrome is quite variable, with different individuals eliciting combinations of the above components.

Poland syndrome was initially believed to be a nonfamilial disorder due to its sporadic nature, as illustrated by a case report of an isolated affected identical twin.3 However, enough cases of familial involvement have been reported that there is a proposed theory of an inheritable trait. Although over 250 patients with this syndrome have been described, there is no clear cause.2 The current theory of etiology is felt to be due to a lack of blood flow in the subclavian artery, or one of its branches, early in the development of the fetus, around the end of the sixth week of development. Individuals can have mild to severe manifestations, ranging as mild (eg, only pectoralis involvement), to severe (eg, rib hypoplasia, complete absence of ipsilateral hand, dextrocardia, lung herniation). Case reports of high functioning athletes with the disorder show that there is not necessarily functional impairment.

In addition to Poland syndrome, there are a number of congenital abnormalities that can also mimic traumatic chest injuries. Historically, surgeons have classified congenital wall deformities into one of five categories: Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum, sternal clefts, and generic skeletal and cartilage dysplasias (eg, absent ribs, rib torsion, vertebral anomalies).5-7 Of these categories, Poland syndrome, pectus excavatum, and some skeletal dysplasias cause anterior chest wall depression.5,6 Although these are examples of congenital thoracic wall abnormalities, one must also remember postoperative changes, which may also appear to be traumatic in origin. Examples of specific procedures are lumpectomy, mastectomy, rib resection, lung resection, or even cardiac surgery—all of which can alter the physical findings of the chest wall.

Conclusion

This report is an interesting case of an impaired patient presenting to the ED after a traumatic incident and unable to describe a past medical history of a congenital disorder. Although the patient was high functioning, as exemplified by his ability to complete normal adolescent activities such as skateboarding, he had a significant physical finding which appeared to correspond to the mechanism of his injury. He was initially thought to have a significant injury involving his chest wall, since secondary examination revealed a palpable defect. Although the patient was oxygenating well, and in no apparent distress, his altered mental status raised concerns about the accuracy of his report, with confusion and perseveration.

When a rare congenital abnormality imitates a traumatic condition, merely having the name of the condition—as we did when the family arrived—does not necessarily rule out the absence of a related deficit or injury. To better differentiate acute from preexisting physical deformities or deficits, one must gather and process multiple diagnostic clues. This is best accomplished by combining the presence or absence of symptoms (in this case, pain, dyspnea, or hemoptysis), physical examination findings (eg, ecchymosis, crepitance, flail segment), and supportive diagnostic tests (radiographs, CT, and echocardiograms). This approach will systematically eliminate or suggest acute traumatic diagnoses. With specific traumatic causes such as rib fracture, pneumothorax, or pulmonary contusion eliminated, one can expand the (nontraumatic) differential, keeping in mind the possibility of a congenital disorder.

Dr Martin is an emergency physician at Emergency Medical Associates of NY and NJ; and emergency medicine education director, Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ.

Dr Martin reports no conflict of interest or financial arrangements.

- Fokin AA, Robicsek F. Poland syndrome revisited. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(6):2218-2225

- Darian VB, Argenta LC, Pasyk KA. Familial Poland’s syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;23(6):531-537

- Stevens D, Fink B, Prevel C. Poland’s syndrome in one identical twin. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(3):392-395.

- McGrath MH, Pomerantz J. Plastic surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1935

- Spear SL, Pelletiere CV, Lee ES, Grotting JC. Anterior thoracic hypoplasia: a separate entity from Poland syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(1):

- Hodgkinson, DJ. Chest wall implants: their use for pectus excavatum, pectoralis muscle tears, Poland’s syndrome, and muscular insufficiency. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21(1):7-15.

- Hodgkinson, DJ. The management of anterior chest wall deformity in patients presenting for breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(5): 1714-1723.

- Fokin AA, Robicsek F. Poland syndrome revisited. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(6):2218-2225

- Darian VB, Argenta LC, Pasyk KA. Familial Poland’s syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;23(6):531-537

- Stevens D, Fink B, Prevel C. Poland’s syndrome in one identical twin. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(3):392-395.

- McGrath MH, Pomerantz J. Plastic surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1935

- Spear SL, Pelletiere CV, Lee ES, Grotting JC. Anterior thoracic hypoplasia: a separate entity from Poland syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(1):

- Hodgkinson, DJ. Chest wall implants: their use for pectus excavatum, pectoralis muscle tears, Poland’s syndrome, and muscular insufficiency. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21(1):7-15.

- Hodgkinson, DJ. The management of anterior chest wall deformity in patients presenting for breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(5): 1714-1723.