User login

Heart failure guidelines: What you need to know about the 2017 focused update

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) jointly released a focused update1 of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline for managing heart failure.2 This is the second focused update of the 2013 guidelines; the first update,3 in 2016, covered 2 new drugs (sacubitril-valsartan and ivabradine) for chronic stage C heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

Rather than focus on new medication classes, this second update provides recommendations regarding:

- Preventing the progression to left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure in patients at high risk (stage A) through screening with B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and aiming for more aggressive blood pressure control

- Inpatient biomarker use

- Medications in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, or diastolic heart failure)

- Blood pressure targets in stage C heart failure

- Managing important comorbidities such as iron deficiency and sleep-disordered breathing to decrease morbidity, improve functional capacity, and enhance quality of life.

These guidelines and the data that underlie them are explored below. We also discuss potential applications to the management of hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

COMMON, COSTLY, AND DEBILITATING

Heart failure—defined by the ACC/AHA as the complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood—remains one of the most common, costly, and debilitating diseases in the United States.2 Based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 2011 to 2014, an estimated 6.5 million US adults have it, with projections of more than 8 million by 2030.4,5 More than 960,000 new cases are thought to occur annually, with a lifetime risk of developing it of roughly 20% to 45%.6

Despite ever-growing familiarity and some significant strides in management, the death rate in this syndrome is substantial. After admissions for heart failure (which number 1 million per year), the mortality rate is roughly 10% at 1 year and 40% at 5 years.6 Also staggering are the associated costs, with $30.7 billion attributed to heart failure in 2012 and a projected $69.7 billion annually by 2030.5 Thus, we must direct efforts not only to treatment, but also to prevention.

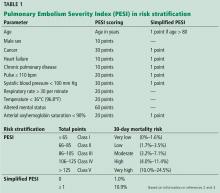

Preventive efforts would target patients with ACC/AHA stage A heart failure—those at high risk for developing but currently without evidence of structural heart disease or heart failure symptoms (Table 1).7 This group may represent up to one-third of the US adult population, or 75 million people, when including the well-recognized risk factors of coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease in those without left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure.8

BIOMARKERS FOR PREVENTION

Past ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines2 have included recommendations on the use of biomarkers to aid in diagnosis and prognosis and, to a lesser degree, to guide treatment of heart failure. Largely based on 2 trials (see below), the 2017 guidelines go further, issuing a recommendation on the use of natriuretic peptide biomarkers in a screening strategy to prompt early intervention and prevent the progression to clinical heart failure in high-risk patients (stage A heart failure).

The PONTIAC trial

The NT-proBNP Selected Prevention of Cardiac Events in a Population of Diabetic Patients Without a History of Cardiac Disease (PONTIAC) trial9 randomized 300 outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and an elevated N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) level (> 125 pg/mL) to standard medical care vs standard care plus intensive up-titration of renin-angiotensin system antagonists and beta-blockers in a cardiac clinic over 2 years.

Earlier studies10 had shown NT-proBNP levels to have predictive value for cardiac events in diabetic patients, while the neurohormonal treatments were thought to have an established record of preventing primary and secondary cardiovascular events. In PONTIAC, a significant reduction was seen in the primary end point of hospitalization or death due to cardiac disease (hazard ratio [HR] 0.351, P = .044), as well as in the secondary end point of hospitalization due to heart failure (P < .05), in the aggressive-intervention group. These results laid the foundation for the larger St. Vincent’s Screening to Prevent Heart Failure (STOP-HF) trial.11

The STOP-HF trial

The STOP-HF trial randomized 1,235 outpatients who were at high risk but without left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure symptoms (stage A) to annual screening alone vs annual screening plus BNP testing, in which a BNP level higher than 50 pg/mL triggered echocardiography and evaluation by a cardiologist who would then assist with medications.11

Eligible patients were over age 40 and had 1 or more of the following risk factors:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2)

- Vascular disease (coronary, cerebral, or peripheral arterial disease)

- Arrhythmia requiring treatment

- Moderate to severe valvular disease.

After a mean follow-up of 4.3 years, the primary end point, ie, asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction with or without newly diagnosed heart failure, was found in 9.7% of the control group and in only 5.9% of the intervention group with BNP screening, a 42% relative risk reduction (P = .013).

Similarly, the incidence of secondary end points of emergency hospitalization for a cardiovascular event (arrhythmia, transient ischemic attack, stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral or pulmonary thrombosis or embolization, or heart failure) was also lower at 45.2 vs 24.4 per 1,000 patient-years, a 46% relative risk reduction.

An important difference in medications between the 2 groups was an increase in subsequently prescribed renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system therapy, mainly consisting of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in those with elevated BNP in the intervention group. Notably, blood pressure was about the same in the 2 groups.11

Although these findings are encouraging, larger studies are needed, as the lack of blinding, low event rates, and small absolute risk reduction make the results difficult to generalize.

New or modified recommendations for screening

Employing this novel prevention strategy in the extremely large number of patients with stage A heart failure, thought to be up to one-third of the US adult population, may serve as a way to best direct and utilize limited medical resources.8

BIOMARKERS FOR PROGNOSIS OR ADDED RISK STRATIFICATION

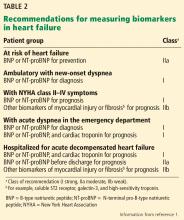

The 2013 guidelines2 recognized that a significant body of work had accumulated showing that natriuretic peptide levels can predict outcomes in both chronic and acute heart failure. Thus, in both conditions, the guidelines contained separate class Ia recommendations to obtain a natriuretic peptide level, troponin level, or both to establish prognosis or disease severity.

The 2017 update1 underscores the importance of timing in measuring natriuretic peptide levels during admission for ADHF, with emphasis on obtaining them at admission and at discharge for acute and postdischarge prognosis. The completely new class IIa recommendation to obtain a predischarge natriuretic peptide level for postdischarge prognosis was based on a number of observational studies, some of which we explore below.

The ELAN-HF meta-analysis

The European Collaboration on Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (ELAN-HF)12 performed a meta-analysis to develop a discharge prognostication score for ADHF that included both absolute level and percent change in natriuretic peptide levels at the time of discharge.

Using data from 7 prospective cohorts totaling 1,301 patients, the authors found that incorporation of these values into a subsequently validated risk model led to significant improvements in the ability to predict the end points of all-cause mortality and the combined end point of all-cause mortality or first readmission for a cardiovascular reason within 180 days.

The OPTIMIZE-HF retrospective analysis

Data from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) were retrospectively analyzed13 to determine whether postdischarge outcomes were best predicted by natriuretic peptide levels at admission or discharge or by the relative change in natriuretic peptide level. More than 7,000 patients age 65 or older, in 220 hospitals, were included, and Cox prediction models were compared using clinical variables alone or in combination with the natriuretic peptide levels.

The model that included the discharge natriuretic peptide level was found to be the most predictive, with a c-index of 0.693 for predicting mortality and a c-index of 0.606 for mortality or rehospitalization at 1 year.

New or modified recommendations on biomarkers for prognosis

The 2017 update1 modified the earlier recommendation to obtain a natriuretic peptide or troponin level or both at admission for ADHF to establish prognosis. This now has a class Ia recommendation, emphasizing that such levels be obtained on admission. In addition, a new class IIa recommendation is made to obtain a predischarge natriuretic peptide level for postdischarge prognosis. The former class Ia recommendation to obtain a natriuretic peptide level in chronic heart failure to establish prognosis or disease severity remains unchanged.

Also worth noting is what the 2017 update does not recommend in regard to obtaining biomarker levels. It emphasizes that many patients, particularly those with advanced (stage D) heart failure, have a poor prognosis that is well established with or without biomarker levels. Additionally, there are many cardiac and noncardiac causes of natriuretic peptide elevation; thus, clinical judgment remains paramount.

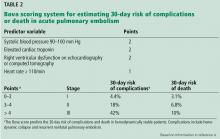

The 2017 update1 also cautions against setting targets of percent change in or absolute levels of natriuretic peptide at discharge despite observational and retrospective studies demonstrating better outcomes when levels are reduced, as treating for any specific target has never been studied in a large prospective study. Thus, doing so may result in unintended harm. Rather, clinical judgment and optimization of guideline-directed management and therapy are encouraged (Table 2).

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT FOR STAGE C HFpEF

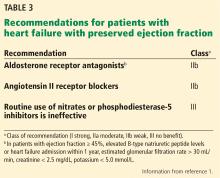

Although the 2013 guidelines2 contain many class I recommendations for various medications in chronic HFrEF, not a single such recommendation is found for chronic HFpEF. A review by Okwuosa et al7 covered HFrEF, including the most recent additions on which the 2016 update was based, sacubitril-valsartan and ivabradine. The 2016 update was similarly devoid of recommendations regarding specific medications in HFpEF, leaving only the 2013 class IIb recommendation to consider using an ARB to decrease hospitalizations in HFpEF.

Evidence behind this recommendation came from the Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity program’s randomized controlled trial in 3,025 patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II to IV heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction over 40%, who were treated with candesartan or placebo.14 Over a median follow-up of 36.6 months, there was no significant difference in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death or admission for heart failure, but significantly fewer patients in the candesartan arm were admitted (230 vs 270, P = .017). Thus the recommendation.

Although this finding was encouraging, it was clear that no blockbuster drug for HFpEF had been identified. Considering that roughly half of all heart failure patients have preserved ejection fraction, the discovery of such a drug for HFpEF would be met with much excitement.15 Subsequently, other medication classes have been evaluated in the hope of benefit, allowing the 2017 update to provide specific recommendations for aldosterone antagonists, nitrates, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors in HFpEF.

ALDOSTERONE ANTAGONISTS FOR HFpEF

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists had previously been shown to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality rates in patients with HFrEF.16 In addition to aldosterone’s effects on sodium retention and many other pathophysiologic mechanisms relating to heart failure, this hormone is also known to play a role in promoting myocardial fibrosis.17 Accordingly, some have wondered whether aldosterone antagonists could improve diastolic dysfunction, and perhaps outcomes, in HFpEF.

The Aldo-DHF trial

The Aldosterone Receptor Blockade in Diastolic Heart Failure (Aldo-DHF) trial investigated whether the aldosterone antagonist spironolactone would improve diastolic function or maximal exercise capacity in chronic HFpEF.18 It randomized 422 ambulatory patients with NYHA stage II or III heart failure, preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (≥ 50%), and echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction to receive spironolactone 25 mg daily or placebo.

Although no significant difference was seen in maximal exercise capacity, follow-up over 1 year nevertheless showed significant improvement in echocardiographic diastolic dysfunction (E/e') and perhaps reverse remodeling (decreased left ventricular mass index). These improvements spurred larger trials powered to detect whether clinical outcomes could also be improved.

The TOPCAT trial

The Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial19 was a large, multicenter, international, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that investigated whether spironolactone could improve clinical outcomes in HFpEF. It randomized 3,445 patients with symptomatic heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction of 45% or more to spironolactone 15 to 45 mg daily or placebo.

The effect on a composite primary outcome of death from cardiovascular cause, aborted cardiac arrest, or hospitalization for heart failure was evaluated over a mean follow-up of 3.3 years, with only a small (HR 0.89), nonclinically significant reduction evident. Those in the spironolactone group did have a significantly lower incidence of hospitalization for heart failure (12.0% vs 14.2%, P = .04).

Although the results were disappointing in this essentially negative trial, significant regional variations evident on post hoc analysis prompted further investigation and much controversy since the trial’s publication in 2014.

Participants came in roughly equal proportions from the Americas (United States, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina—51%) and from Russia and Georgia (49%), but outcomes between the two groups were markedly different. Concern was first raised when immediate review discovered a 4-fold lower rate of the primary outcome in the placebo groups from Russia and Georgia (8.4%), a rate in fact similar to that in patients without heart failure.19 This led to further exploration that identified other red flags that called into question the data integrity from the non-American sites.20

Not only did patients receiving spironolactone in Russia and Georgia not experience the reduction in clinical outcomes seen in their American counterparts, they also did not manifest the expected elevations in potassium and creatinine, and spironolactone metabolites were undetectable in almost one-third of patients.21

These findings prompted a post hoc analysis that included only the 51% (1,767 patients) of the study population coming from the Americas; in this subgroup, treatment with spironolactone was associated with a statistically significant 18% relative risk reduction in the primary composite outcome, a 26% reduction in cardiovascular mortality, and an 18% reduction in hospitalization for heart failure.20

New or modified recommendations on aldosterone receptor antagonists

Nitrates and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

Earlier studies indicated that long-acting nitrates are prescribed in 15% to 50% of patients with HFpEF, perhaps based on extrapolation from studies in HFrEF suggesting that they might improve exercise intolerance.22 Some have speculated that the hemodynamic effects of nitrates, such as decreasing pulmonary congestion, might improve exercise intolerance in those with the stiff ventricles of HFpEF as well, prompting further study.

The NEAT-HFpEF trial

The Nitrate’s Effect on Activity Tolerance in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (NEAT-HFpEF) trial22 investigated whether extended-release isosorbide mononitrate would increase daily activity levels in patients with HFpEF. This double-blind, crossover study randomized 110 patients with HFpEF (ejection fraction ≥ 50%) and persistent dyspnea to escalating doses of isosorbide mononitrate or placebo over 6 weeks, then to the other arm for another 6 weeks. Daily activity levels during the 120-mg phase were measured with a continuously worn accelerometer.

No beneficial effect of nitrates was evident, with a nonsignificant trend towards decreased activity levels, a significant decrease in hours of activity per day (–0.30 hours, P = .02), and no change in the other secondary end points such as quality-of-life score, 6-minute walk distance, or natriuretic peptide level.

Suggested explanations for these negative findings include the possibility of rapid dose escalation leading to increased subtle side effects (headache, dizziness, fatigue) that, in turn, decreased activity. Additionally, given the imprecise diagnostic criteria for HFpEF, difficulties with patient selection may have led to inclusion of a large number of patients without elevated left-sided filling pressures.23

The RELAX trial

The Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibition to Improve Clinical Status and Exercise Capacity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (RELAX) trial24 investigated whether the phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor sildenafil would improve exercise capacity in HFpEF. Improvements in both exercise capacity and clinical outcomes had already been seen in earlier trials in patients with pulmonary hypertension, as well as in those with HFrEF.25 A smaller study in HFpEF patients with pulmonary hypertension was also encouraging.26

Thus, it was disappointing that, after randomizing 216 outpatients with HFpEF to sildenafil or placebo for 24 weeks, no benefit was seen in the primary end point of change in peak oxygen consumption or in secondary end points of change in 6-minute walk distance or composite clinical score. Unlike in NEAT-HFpEF, patients here were required to have elevated natriuretic peptide levels or elevated invasively measured filling pressures.

The study authors speculated that pulmonary arterial hypertension and right ventricular systolic failure might need to be significant for patients with HFpEF to benefit from phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, with their known effects of dilation of pulmonary vasculature and increasing contractility of the right ventricle.24

New or modified recommendations on nitrates or phosphodiesterase-5 drugs

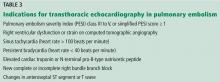

Given these disappointing results, the 2017 update provides a class III (no benefit) recommendation against the routine use of nitrates or phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors to improve exercise tolerance or quality of life in HFpEF, citing them as ineffective (Table 3).1

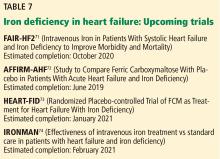

IRON DEFICIENCY IN HEART FAILURE

Not only is iron deficiency present in roughly 50% of patients with symptomatic heart failure (stage C and D HFrEF),27 it is also associated with increased heart failure symptoms such as fatigue and exercise intolerance,28 reduced functional capacity, decreased quality of life, and increased mortality.

Notably, this association exists regardless of the hemoglobin level.29 In fact, even in those without heart failure or anemia, iron deficiency alone results in worsened aerobic performance, exercise intolerance, and increased fatigue.30 Conversely, improvement in symptoms, exercise tolerance, and cognition have been shown with repletion of iron stores in such patients.31

At the time of the 2013 guidelines, only a single large trial of intravenous iron in HFrEF and iron deficiency had been carried out (see below), and although the results were promising, it was felt that the evidence base on which to make recommendations was inadequate. Thus, recommendations were deferred until more data could be obtained.

Of note, in all the trials discussed below, iron deficiency was diagnosed in the setting of heart failure as ferritin less than 100 mg/mL (absolute iron deficiency) or as ferritin 100 to 300 mg/mL with transferrin saturation less than 20% (relative deficiency).32

The CONFIRM-HF trial

As in the Ferinject Assessment in Patients With Iron Deficiency and Chronic Heart Failure (FAIR-HF) trial,33 the subsequent Ferric Carboxymaltose Evaluation on Performance in Patients With Iron Deficiency in Combination With Chronic Heart Failure (CONFIRM-HF) trial34 involved the intravenous infusion of iron (ferric carboxymaltose) in outpatients with symptomatic HFrEF and iron deficiency. It showed that benefits remained evident with a more objective primary end point (change in 6-minute walk test distance at 24 weeks), and that such benefits were sustained, as seen in numerous secondary end points related to functional capacity at 52 weeks. Benefits in CONFIRM-HF were evident independently from anemia, specifically whether hemoglobin was under or over 12 g/dL.

Although these results were promising, it remained unclear whether such improvements could be obtained with a much easier to administer, more readily available, and less expensive oral iron formulation.

The IRONOUT-HF trial

The Iron Repletion Effects on Oxygen Uptake in Heart Failure (IRONOUT-HF) trial35 investigated whether oral, rather than intravenous, iron supplementation could improve peak exercise capacity in patients with HFrEF and iron deficiency. This double-blind, placebo-controlled trial randomized 225 patients with NYHA class II to IV HFrEF and iron deficiency to treatment with oral iron polysaccharide (150 mg twice daily) or placebo for 16 weeks.

Contrary to the supportive findings above, no significant change was seen in the primary end point of change in peak oxygen uptake or in any of the secondary end points (change in 6-minute walk, quality of life). Also, despite a 15-fold increase in the amount of iron administered in oral form compared with intravenously, little change was evident in the indices of iron stores over the course of the study, with only a 3% increase in transferrin saturation and an 11 ng/mL increase in ferritin. The intravenous trials resulted in a 4-fold greater increase in transferrin saturation and a 20-fold greater increase in ferritin.36

What keeps heart failure patients from absorbing oral iron? It is unclear why oral iron administration in HFrEF, such as in IRONOUT-HF, seems to be so ineffective, but hepcidin—a protein hormone made by the liver that shuts down intestinal iron absorption and iron release from macrophages—may play a central role.37 When iron stores are adequate, hepcidin is upregulated to prevent iron overload. However, hepcidin is also increased in inflammatory states, and chronic heart failure is often associated with inflammation.

With this in mind, the IRONOUT-HF investigators measured baseline hepcidin levels at the beginning and at the end of the 16 weeks and found that high baseline hepcidin levels predicted poorer response to oral iron. Other inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin 6, may also play a role.38,39 Unlike oral iron formulations such as iron polysaccharide, intravenous iron (ferric carboxymaltose) bypasses these regulatory mechanisms, which may partly explain its much more significant effect on the indices of iron stores and outcomes.

New or modified recommendations on iron

The 2017 update1 makes recommendations regarding iron deficiency and anemia in heart failure for the first time.

A class IIb recommendation states that it might be reasonable to treat NYHA class II and III heart failure patients with iron deficiency with intravenous iron to improve functional status and quality of life. A strong recommendation has been deferred until more is known about morbidity and mortality effects from adequately powered trials, some of which are under way and explored further below.

The 2017 update also withholds any recommendations regarding oral iron supplementation in heart failure, citing an uncertain evidence base. Certainly, the subsequent IRONOUT-HF trial does not lend enthusiasm for this approach.

Lastly, given the lack of benefit coupled with the increased risk of thromboembolic events evident in a trial of darbepoetin alfa vs placebo in non-iron deficiency-related anemia in HFrEF,40,41 the 2017 update provides a class III (no benefit) recommendation against using erythropoietin-stimulating agents in heart failure and anemia.

HYPERTENSION IN HEART FAILURE

The 2013 guidelines for the management of heart failure simply provided a class I recommendation to control hypertension and lipid disorders in accordance with contemporary guidelines to lower the risk of heart failure.1

SPRINT

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT)42 sought to determine whether a lower systolic blood pressure target (120 vs 140 mm Hg) would reduce clinical events in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events but without diabetes mellitus. Patients at high risk were defined as over age 75, or with known vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, or a Framingham Risk Score higher than 15%. This multicenter, open-label controlled trial randomized 9,361 patients to intensive treatment (goal systolic blood pressure < 120 mm Hg) or standard treatment (goal systolic blood pressure < 140 mm Hg).

SPRINT was stopped early at a median follow-up of 3.26 years when a 25% relative risk reduction in the primary composite outcome of myocardial infarction, other acute coronary syndromes, stroke, heart failure, or death from cardiovascular causes became evident in the intensive-treatment group (1.65% vs 2.19% per year, HR 0.75, P < .0001).

All-cause mortality was also lower in the intensive-treatment group (HR 0.73, P = .003), while the incidence of serious adverse events (hypotension, syncope, electrolyte abnormalities, acute kidney injury, and noninjurious falls) was only slightly higher (38.3% vs 37.1%, P = .25). Most pertinent, a significant 38% relative risk reduction in heart failure and a 43% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular events were also evident.

Of note, blood pressure measurements were taken as the average of 3 measurements obtained by an automated cuff taken after the patient had been sitting quietly alone in a room for 5 minutes.

New or modified recommendations on hypertension in heart failure

Given the impressive 25% relative risk reduction in myocardial infarction, other acute coronary syndromes, stroke, heart failure, or death from cardiovascular causes in SPRINT,42 the 2017 update1 incorporated the intensive targets of SPRINT into its recommendations. However, to compensate for what are expected to be higher blood pressures obtained in real-world clinical practice as opposed to the near-perfect conditions used in SPRINT, a slightly higher blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg was set.

Although not specifically included in SPRINT, given the lack of trial data on specific blood pressure targets in HFrEF and the decreased cardiovascular events noted above, a class I (level of evidence C, expert opinion) recommendation to target a goal systolic blood pressure less than 130 mm Hg in stage C HFrEF with hypertension is also given. Standard guideline-directed medications in the treatment of HFrEF are to be used (Table 4).

Similarly, a new class I (level of evidence C, expert opinion) recommendation is given for hypertension in HFpEF to target a systolic blood pressure of less than 130 mm Hg, with special mention to first manage any element of volume overload with diuretics. Other than avoiding nitrates (unless used for angina) and phosphodiesterase inhibitors, it is noted that few data exist to guide the choice of antihypertensive further, although perhaps renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition, especially aldosterone antagonists, may be considered. These recommendations are fully in line with the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure clinical practice guidelines,43 ie, that renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or ARB and especially mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists would be the preferred choice (Table 4).

SLEEP-DISORDERED BREATHING IN HEART FAILURE

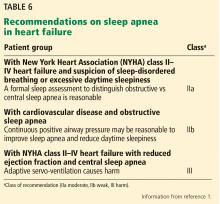

Sleep-disordered breathing, either obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) or central sleep apnea, is quite commonly associated with symptomatic HFrEF.44 Whereas OSA is found in roughly 18% and central sleep apnea in 1% of the general population, sleep-disordered breathing is found in nearly 60% of patients with HFrEF, with some studies showing a nearly equal proportion of OSA and central sleep apnea.45 A similar prevalence is seen in HFpEF, although with a much higher proportion of OSA.46 Central sleep apnea tends to be a marker of more severe heart failure, as it is strongly associated with severe cardiac systolic dysfunction and worse functional capacity.47

Not surprisingly, the underlying mechanism of central sleep apnea is quite different from that of OSA. Whereas OSA predominantly occurs because of repeated obstruction of the pharynx due to nocturnal pharyngeal muscle relaxation, no such airway patency issues or strained breathing patterns exist in central sleep apnea. Central sleep apnea, which can manifest as Cheyne-Stokes respirations, is thought to occur due to an abnormal ventilatory control system with complex pathophysiology such as altered sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to carbon dioxide, interplay of pulmonary congestion, subsequent hyperventilation, and prolonged circulation times due to reduced cardiac output.48

What the two types of sleep-disordered breathing have in common is an association with negative health outcomes. Both appear to induce inflammation and sympathetic nervous system activity via oxidative stress from intermittent nocturnal hypoxemia and hypercapnea.49 OSA was already known to be associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates in the general population,50 and central sleep apnea had been identified as an independent predictor of mortality in HFrEF.51

At the time of the 2013 guidelines, only small or observational studies with limited results had been done evaluating treatment effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP) on OSA and central sleep apnea. Given the relative paucity of data, only a single class IIa recommendation stating that CPAP could be beneficial to increase left ventricular ejection fraction and functional status in concomitant sleep apnea and heart failure was given in 2013. However, many larger trials were under way,52–59 some with surprising results such as a significant increase in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Table 5).54

New or modified recommendations on sleep-disordered breathing

Given the common association with heart failure (60%)45 and the marked variation in response to treatment, including potential for harm with adaptive servo-ventilation and central sleep apnea, a class IIa recommendation is made stating that it is reasonable to obtain a formal sleep study in any patient with symptomatic (NYHA class II–IV) heart failure.1

Due to the potential for harm with adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with central sleep apnea and NYHA class II to IV HFrEF, a class III (harm) recommendation is made against its use.

Largely based on the results of the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial,56 a class IIb, level of evidence B-R (moderate, based on randomized trials) recommendation is given, stating that the use of CPAP in those with OSA and known cardiovascular disease may be reasonable to improve sleep quality and reduce daytime sleepiness.

POTENTIAL APPLICATIONS IN ACUTE DECOMPENSATED HEART FAILURE

Although the 2017 update1 is directed mostly toward managing chronic heart failure, it is worth considering how it might apply to the management of ADHF.

SHOULD WE USE BIOMARFER TARGETS TO GUIDE THERAPY IN ADHF?

The 2017 update1 does offer direct recommendations regarding the use of biomarker levels during admissions for ADHF. Mainly, they emphasize that the admission biomarker levels provide valuable information regarding acute prognosis and risk stratification (class I recommendation), while natriuretic peptide levels just before discharge provide the same for the postdischarge timeframe (class IIa recommendation).

The update also explicitly cautions against using a natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment strategy, such as setting targets for predischarge absolute level or percent change in level of natriuretic peptides during admissions for ADHF. Although observational and retrospective studies have shown better outcomes when levels are reduced at discharge, treating for any specific inpatient target has never been tested in any large, prospective study; thus, doing so could result in unintended harm.

So what do we know?

McQuade et al systematic review

McQuade et al57 performed a systematic review of more than 40 ADHF trials, which showed that, indeed, patients who achieved a target absolute natriuretic peptide level (BNP ≤ 250 pg/mL) or percent reduction (≥ 30%) at time of discharge had significantly improved outcomes such as reduced postdischarge all-cause mortality and rehospitalization rates. However, these were mostly prospective cohort studies that did not use any type of natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment protocol, leaving it unclear whether such a strategy could positively influence outcomes.

For this reason, both McQuade et al57 and, in an accompanying editorial, Felker et al58 called for properly designed, randomized controlled trials to investigate such a strategy. Felker noted that only 2 such phase II trials in ADHF have been completed,59,60 with unconvincing results.

PRIMA II

The Multicenter, Randomized Clinical Trial to Study the Impact of In-hospital Guidance for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Treatment by a Predefined NT-ProBNP Target on the Reduction of Readmission and Mortality Rates (PRIMA II)60 randomized patients to natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment or standard care during admission for ADHF.

Many participants (60%) reached the predetermined target of 30% reduction in natriuretic peptide levels at the time of clinical stabilization and randomization; 405 patients were randomized. Patients in the natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment group underwent a prespecified treatment algorithm, with repeat natriuretic peptide levels measured again after the protocol.

Natriuretic peptide-guided therapy failed to show any significant benefit in any clinical outcomes, including the primary composite end point of mortality or heart failure readmissions at 180 days (36% vs 38%, HR 0.99, 95% confidence interval 0.72–1.36). Consistent with the review by McQuade et al,57 achieving the 30% reduction in natriuretic peptide at discharge, in either arm, was associated with a better prognosis, with significantly lower mortality and readmission rates at 180 days (HR 0.39 for rehospitalization or death, 95% confidence interval 0.27–0.55).

As in the observational studies, those who achieved the target natriuretic peptide level at the time of discharge had a better prognosis than those who did not, but neither study showed an improvement in clinical outcomes using a natriuretic peptide level-targeting treatment strategy.

No larger randomized controlled trial results are available for guided therapy in ADHF. However, additional insight may be gained from a subsequent trial61 that evaluated biomarker-guided titration of guideline-directed medical therapy in outpatients with chronic HFrEF.

The GUIDE-IT trial

That trial, the Guiding Evidence Based Therapy Using Biomarker Intensified Treatment in Heart Failure (GUIDE-IT)61 trial, was a large multicenter attempt to determine whether a natriuretic peptide-guided treatment strategy was more effective than standard care in the management of 894 high-risk outpatients with chronic HFrEF. Earlier, promising results had been obtained in a meta-analysis62 of more than 11 similar trials in 2,000 outpatients, with a decreased mortality rate (HR 0.62) seen in the biomarker-guided arm. However, the results had not been definitive due to being underpowered.62

Unfortunately, the results of GUIDE-IT were disappointing, with no significant difference in either the combined primary end point of mortality or hospitalization for heart failure, or the secondary end points evident at 15 months, prompting early termination for futility.61 Among other factors, the study authors postulated that this may have partly resulted from a patient population with more severe heart failure and resultant azotemia, limiting the ability to titrate neurohormonal medications to the desired dosage.

The question of whether patients who cannot achieve such biomarker targets need more intensive therapy or whether their heart failure is too severe to respond adequately echoes the question often raised in discussions of inpatient biomarker-guided therapy.58 Thus, only limited insight is gained, and it remains unclear whether a natriuretic peptide-guided treatment strategy can improve outpatient or inpatient outcomes. Until this is clarified, clinical judgment and optimization of guideline-directed management and therapy should remain the bedrock of treatment.

SHOULD ALDOSTERONE ANTAGONISTS BE USED IN ACUTE HFpEF?

Given the encouraging results in chronic HFpEF from post hoc analyses of TOPCAT, are there any additional recent data suggesting a role for aldosterone antagonists such as spironolactone in acute HFpEF?

The ATHENA-HF trial

The Aldosterone Targeted Neurohormonal Combined With Natriuresis Therapy in Heart Failure (ATHENA-HF) trial63 compared treatment with high-dose spironolactone (100 mg) for 96 hours vs usual care in 360 patients with ADHF. The patient population included those with HFrEF and HFpEF, and usual care included low-dose spironolactone (12.5–25 mg) in roughly 15% of patients. High-dose mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists have been shown to overcome diuretic resistance, improve pulmonary vascular congestion, and partially combat the adverse neurohormonal activation seen in ADHF.

Unfortunately, the trial was completely neutral in regard to the primary end point of reduction in natriuretic peptide levels as well as to the secondary end points of 30-day mortality rate, heart failure readmission, clinical congestion scores, urine output, and change in weight. No suggestion of additional benefit was seen in subgroup analysis of patients with acute HFpEF (ejection fraction > 45%), which yielded similar results.63

Given these lackluster findings, routine use of high-dose spironolactone in ADHF is not recommended.64 However, the treatment was well tolerated, without significant adverse effects of hyperkalemia or kidney injury, leaving the door open as to whether it may have utility in selected patients with diuretic resistance.

Should ARNIs and ivabradine be started during ADHF admissions?

The first half of the focused update3 of the 2013 guidelines,2 reviewed by Okwuosa et al,7 provided recommendations for the use of sacubitril-valsartan, an angiotensin-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), and ivabradine, a selective sinoatrial node If channel inhibitor, in chronic HFrEF.

Sacubitril-valsartan was given a class I recommendation for use in patients with NYHA class II or III chronic HFrEF who tolerate an ACE inhibitor or an ARB. This recommendation was given largely based on the benefits in mortality and heart failure hospitalizations seen in PARADIGM-HF (the Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure)65 compared with enalapril (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.73–0.87, P < .001).

There is currently no recommendation on initiation or use of ARNIs during admissions for ADHF, but a recent trial may lend some insight.66

THE PIONEER-HF trial

The Comparison of Sacubitril/Valsartan vs Enalapril on Effect on NT-proBNP in Patients Stabilized From an Acute Heart Failure Episode (PIONEER-HF) trial66 randomized patients admitted for acute HFrEF, once stabilized, to sacubitril-valsartan or enalapril. Encouragingly, the percentage change of natriuretic peptide levels from the time of inpatient initiation to 4 and 8 weeks thereafter, the primary efficacy end point, was 46.7% with sacubitril-valsartan versus 25.3% with enalapril alone (ratio of change 0.71, 95% CI 0.63–0.81, P < .001). Although not powered for such, a prespecified analysis of a composite of clinical outcomes was also favorable for sacubitril-valsartan, largely driven by a 44% decreased rate of rehospitalization. More definitive, and quite reassuring, was that no significant difference was seen in the key safety outcomes of worsening renal function, hyperkalemia, symptomatic hypotension, and angioedema. These results were also applicable to the one-third of study participants who had no former diagnosis of heart failure, the one-third identifying as African American, and the one-third who had not been taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB. These results, taken together with the notion that at study completion the patients become similar to those included in PARADIGM-HF, have led some to assert that PIONEER-HF has the potential to change clinical practice.

Ivabradine was given a class IIa recommendation for use in patients with NYHA class II or III chronic HFrEF with a resting heart rate of at least 70 bpm, in sinus rhythm, despite being on optimal medical therapy including a beta-blocker at a maximum tolerated dose.

This recommendation was largely based on SHIFT (Systolic Heart Failure Treatment With the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial), which randomized patients to ivabradine or placebo to evaluate the effects of isolated lowering of the heart rate on the composite primary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization. A significant reduction was seen in the ivabradine arm (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.75–0.90, P < .0001), mainly driven by decreased hospitalizations.67

Subsequently, a small unblinded single-center study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy and safety of initiating ivabradine during admissions for ADHF.68

THE ETHIC-AHF trial

The Effect of Early Treatment With Ivabradine Combined With Beta-Blockers vs Beta-Blockers Alone in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure and Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (ETHIC-AHF) trial68 sought to determine the safety and effectiveness of early coadministration of ivabradine with beta-blockers in patients with acute HFrEF.

This single-center, unblinded study randomized 71 patients to ivabradine and beta-blockade or beta-blockade alone upon clinical stabilization (24–48 hours) after admission for acute decompensated HFrEF.

The primary end point was heart rate at 28 days, with the ivabradine group showing a statistically significant decrease (64 vs 70 bpm, P = .01), which persisted at 4 months. There was no significant difference in the secondary end points of adverse drug effects or the composite of clinical event outcomes (all-cause mortality, admission for heart failure or cardiovascular cause), but a number of surrogate end points including left ventricular ejection fraction, BNP level, and NYHA functional class at 4 months showed mild improvement.

Although this study provided evidence that the coadministration of ivabradine and a beta-blocker is safe and was positive in regard to clinical outcomes, the significant limitations due to its size and study design (single-center, unblinded, 4-month follow-up) simply serve to support the pursuit of larger studies with more stringent design and longer follow-up in order to determine the clinical efficacy.

The PRIME-HF trial

The Predischarge Initiation of Ivabradine in the Management of Heart Failure (PRIME-HF) trial69 is a randomized, open-label, multicenter trial comparing standard care vs the initiation of ivabradine before discharge, but after clinical stabilization, during admissions for ADHF in patients with chronic HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 35%). At subsequent outpatient visits, the dosage can be modified in the ivabradine group, or ivabradine can be initiated at the provider’s discretion in the usual-care group.

PRIME-HF is attempting to determine whether initiating ivabradine before discharge will result in more patients taking ivabradine at 180 days, its primary end point, as well as in changes in secondary end points including heart rate and patient-centered outcomes. The study is active, with reporting expected in 2019.

As these trials all come to completion, it will not be long before we have further guidance regarding the inpatient initiation of these new and exciting therapeutic agents.

SHOULD INTRAVENOUS IRON BE GIVEN DURING ADHF ADMISSIONS?

Given the high prevalence of iron deficiency in symptomatic HFrEF, its independent association with mortality, improvements in quality of life and functional capacity suggested by repleting with intravenous iron (in FAIR-HF and CONFIRM-HF), the seeming inefficacy of oral iron in IRONOUT, and the logistical challenges of intravenous administration during standard clinic visits, could giving intravenous iron soon be incorporated into admissions for ADHF?

Caution has been advised for several reasons. As discussed above, larger randomized controlled trials powered to detect more definitive clinical end points such as death and the rate of hospitalization are still needed before a stronger recommendation can be made for intravenous iron in HFrEF. Also, without such data, it seems unwise to add the considerable economic burden of routinely assessing for iron deficiency and providing intravenous iron during ADHF admissions to the already staggering costs of heart failure.

The effects seen on morbidity and mortality that become evident in these trials over the next 5 years will help determine future guidelines and whether intravenous iron is routinely administered in bridge clinics, during inpatient admissions for ADHF, or not at all in patients with HFrEF and iron deficiency.

INTERNISTS ARE KEY

Heart failure remains one of the most common, morbid, complex, and costly diseases in the United States, and its prevalence is expected only to increase.4,5 The 2017 update1 of the 2013 guideline2 for the management of heart failure provides recommendations aimed not only at management of heart failure, but also at its comorbidities and, for the first time ever, at its prevention.

Internists provide care for the majority of heart failure patients, as well as for their comorbidities, and are most often the first to come into contact with patients at high risk of developing heart failure. Thus, a thorough understanding of these guidelines and how to apply them to the management of acute decompensated heart failure is of critical importance.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(6):776–803. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.025

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 128(16):e240–e327. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2016; 134(13):e282–e293. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000435

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 135(10):e146–e603. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485

- Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 2013; 6(3):606–619. doi:10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a

- Huffman MD, Berry JD, Ning H, et al. Lifetime risk for heart failure among white and black Americans: cardiovascular lifetime risk pooling project. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61(14):1510–1517. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.022

- Okwuosa IS, Princewill O, Nwabueze C, et al. The ABCs of managing systolic heart failure: past, present, and future. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(10):753–765. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.16006

- Kovell LC, Juraschek SP, Russell SD. Stage A heart failure is not adequately recognized in US adults: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2007–2010. PLoS One 2015; 10(7):e0132228. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132228

- Huelsmann M, Neuhold S, Resl M, et al. PONTIAC (NT-proBNP selected prevention of cardiac events in a population of diabetic patients without a history of cardiac disease): a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62(15):1365–1372. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.069

- Clodi M, Resl M, Neuhold S, et al. A comparison of NT-proBNP and albuminuria for predicting cardiac events in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012; 19(5):944–951. doi:10.1177/1741826711420015

- Ledwidge M, Gallagher J, Conlon C, et al. Natriuretic peptide-based screening and collaborative care for heart failure: the STOP-HF randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 310(1):66–74. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.7588

- Salah K, Kok WE, Eurlings LW, et al. A novel discharge risk model for patients hospitalised for acute decompensated heart failure incorporating N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels: a European coLlaboration on Acute decompeNsated Heart Failure: ELAN-HF Score. Heart 2014; 100(2):115–125. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303632

- Kociol RD, Horton JR, Fonarow GC, et al. Admission, discharge, or change in B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term outcomes: data from Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) linked to Medicare claims. Circ Heart Fail 2011; 4(5):628–636. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.962290

- Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, et al; CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet 2003; 362(9386):777–781. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7

- Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(3):251–259. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052256

- Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(10):709–717. doi:10.1056/NEJM199909023411001

- MacFadyen RJ, Barr CS, Struthers AD. Aldosterone blockade reduces vascular collagen turnover, improves heart rate variability and reduces early morning rise in heart rate in heart failure patients. Cardiovasc Res 1997; 35(1):30–34. pmid:9302344

- Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, et al; Aldo-DHF Investigators. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2013; 309(8):781–791. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.905

- Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, et al; TOPCAT Investigators. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(15):1383–1392. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1313731

- Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, et al. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation 2015; 31(1):34–42. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013255

- de Denus S, O’Meara E, Desai AS, et al. Spironolactone metabolites in TOPCAT—new insights into regional variation. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(17):1690–1692. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1612601

- Redfield MM, Anstrom KJ, Levine JA, et al; NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network. Isosorbide mononitrate in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(24):2314–2324. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1510774

- Walton-Shirley M. Succinct thoughts on NEAT-HFpEF: true, true, and unrelated? Medscape 2015. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/854116. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309(12):1268–1277. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.2024

- Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. PDE5 inhibition with sildenafil improves left ventricular diastolic function, cardiac geometry, and clinical status in patients with stable systolic heart failure: results of a 1-year, prospective, randomized, placebo controlled study. Circ Heart Fail 2011; 4(1):8–17. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944694

- Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation 2011; 124(2):164–174. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.983866

- Klip IT, Comin-Colet J, Voors AA, et al. Iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: an international pooled analysis. Am Heart J 2013; 165(4):575–582.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.01.017

- Jankowska EA, von Haehling S, Anker SD, Macdougall IC, Ponikowski P. Iron deficiency and heart failure: diagnostic dilemmas and therapeutic perspectives. Eur Heart J 2013; 34(11):816–829. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs224

- Jankowska EA, Rozentryt P, Witkowska A, et al. Iron deficiency predicts impaired exercise capacity in patients with systolic chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2011; 17(11):899–906. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.08.003

- Haas JD, Brownlie T 4th. Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. J Nutr 2001; 131(2S–2):676S-690S. doi:10.1093/jn/131.2.676S

- Davies KJ, Maguire JJ, Brooks GA, Dallman PR, Packer L. Muscle mitochondrial bioenergetics, oxygen supply, and work capacity during dietary iron deficiency and repletion. Am J Physiol 1982; 242(6):E418–E427. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1982.242.6.E418

- Drozd M, Jankowska EA, Banasiak W, Ponikowski P. Iron therapy in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency: review of iron preparations for practitioners. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2017; 17(3):183–201. doi:10.1007/s40256-016-0211-2

- Anker SD, Comin Colet J, Filippatos G, et al; FAIR-HF Trial Investigators. Ferric carboxymaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(25):2436–2448. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908355

- Ponikowski P, van Veldhuisen DJ, Comin-Colet J, et al; CONFIRM-HF Investigators. Beneficial effects of long-term intravenous iron therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in patients with symptomatic heart failure and iron deficiency. Eur Heart J 2015; 36(11):657–668. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu385

- Lewis GD, Malhotra R, Hernandez AF, et al; NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network. Effect of Oral Iron Repletion on Exercise Capacity in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Iron Deficiency: The IRONOUT HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 317(19):1958–1966. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.5427

- Wendling P. Iron supplementation in HF: trials support IV but not oral. Medscape 2016. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/872088. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- Ganz T. Hepcidin and iron regulation, 10 years later. Blood 2011; 117(17):4425–4433. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-258467

- Jankowska EA, Kasztura M, Sokolski M, et al. Iron deficiency defined as depleted iron stores accompanied by unmet cellular iron requirements identifies patients at the highest risk of death after an episode of acute heart failure. Eur Heart J 2014; 35(36):2468–2476. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu235

- Jankowska EA, Malyszko J, Ardehali H, et al. Iron status in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2013; 34(11):827–834. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs377

- Swedberg K, Young JB, Anand IS, et al. Treatment of anemia with darbepoetin alfa in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(13):1210–1219. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214865

- Ghali JK, Anand IS, Abraham WT, et al; Study of Anemia in Heart Failure Trial (STAMINA-HeFT) Group. Randomized double-blind trial of darbepoetin alfa in patients with symptomatic heart failure and anemia. Circulation 2008; 117(4):526–535. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698514

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(22):2103–2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Arnow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71(19):e127–e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006

- Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al; Sleep Heart Health Study Research Group. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(8):893–900. pmid:11966340

- MacDonald M, Fang J, Pittman SD, White DP, Malhotra A.The current prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in congestive heart failure patients treated with beta-blockers. J Clin Sleep Med 2008; 4(1):38-42. pmid:18350960

- Bitter T, Faber L, Hering D, Langer C, Horstkotte D, Oldenburg O. Sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2009; 11(6):602–608. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfp057

- Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160(4):1101–1106. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9903020

- Ng AC, Freedman SB. Sleep disordered breathing in chronic heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2009; 14(2):89–99. doi:10.1007/s10741-008-9096-8

- Kasai T, Bradley TD. Obstructive sleep apnea and heart failure: pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57(2):119–127. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.627

- Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet 2005; 365(9464):1046–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7

- Javaheri S, Shukla R, Zeigler H, Wexler L. Central sleep apnea, right ventricular dysfunction, and low diastolic blood pressure are predictors of mortality in systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49(20):2028–2034. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.084

- Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, et al; CANPAP Investigators. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005; 353(19):2025–2033. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051001

- Arzt M, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al; CANPAP Investigators. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP). Circulation 2007; 115(25):3173–3180. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683482

- Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(12):1095–1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506459

- O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Fiuzat M, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with minute ventilation-targeted adaptive servo-ventilation therapy in heart failure: the CAT-HF Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(12):1577–1587. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.041

- McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, et al; SAVE Investigators and Coordinators. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(10):919–931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606599

- McQuade CN, Mizus M, Wald JW, Goldberg L, Jessup M, Umscheid CA. Brain-type natriuretic peptide and amino-terminal pro-brain-type natriuretic peptide discharge thresholds for acute decompensated heart failure: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(3):180–190. doi:10.7326/M16-1468

- Felker GM, Whellan DJ. Inpatient management of heart failure: are we shooting at the right target? Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(3):223–224. doi:10.7326/M16-2667

- Carubelli V, Lombardi C, Lazzarini V, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2016; 17(11):828–839. doi:10.2459/JCM.0000000000000419

- Stienen S, Salah K, Moons AH, et al. Rationale and design of PRIMA II: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial to study the impact of in-hospital guidance for acute decompensated heart failure treatment by a predefined NT-PRoBNP target on the reduction of readmIssion and mortality rates. Am Heart J 2014; 168(1):30–36. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2014.04.008

- Felker GM, Anstrom KJ, Adams KF, et al. Effect of natriuretic peptide-guided therapy on hospitalization or cardiovascular mortality in high-risk patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318(8):713–720. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.10565

- Troughton RW, Frampton CM, Brunner-La Rocca HP, et al. Effect of B-type natriuretic peptide-guided treatment of chronic heart failure on total mortality and hospitalization: an individual patient meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2014; 35(23):1559–1567. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu090

- van Vliet AA, Donker AJ, Nauta JJ, Verheugt FW. Spironolactone in congestive heart failure refractory to high-dose loop diuretic and low-dose angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Am J Cardiol 1993; 71(3):21A–28A. pmid:8422000

- Butler J, Anstrom KJ, Felker GM, et al; National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Heart Failure Clinical Research Network. Efficacy and safety of spironolactone in acute heart failure. The ATHENA-HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2(9):950–958. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2198

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al; PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(11):993–1004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409077

- ClinicalTrials.gov. ComParIson Of Sacubitril/valsartaN Versus Enalapril on Effect on NTpRo-BNP in patients stabilized from an acute Heart Failure episode (PIONEER-HF). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02554890. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- Swedberg K, Komajda M, Böhm M, et al; SHIFT Investigators. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2010; 376(9744):875–885. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61198-1

- Hidalgo FJ, Anguita M, Castillo JC, et al. Effect of early treatment with ivabradine combined with beta-blockers versus beta-blockers alone in patients hospitalised with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (ETHIC-AHF): a randomised study. Int J Cardiol 2016; 217:7–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.136

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Predischarge Initiation of Ivabradine in the Management of Heart Failure (PRIME-HF). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02827500. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- Anker SD, Kirwan BA, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Effects of ferric carboxymaltose on hospitalisations and mortality rates in iron-deficient heart failure patients: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20(1):125–133. doi:10.1002/ejhf.823

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Intravenous Iron in Patients With Systolic Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency to Improve Morbidity and Mortality (FAIR-HF2). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03036462. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to Compare Ferric Carboxymaltose With Placebo in Patients With Acute Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency (AFFIRM-AHF). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02937454. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial of Ferric Carboxymaltose as Treatment for Heart Failure With Iron Deficiency (HEART-FID). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03037931. Accessed January 17, 2019.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Intravenous Iron Treatment in Patients With Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency (IRONMAN). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02642562. Accessed January 17, 2019.

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) jointly released a focused update1 of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline for managing heart failure.2 This is the second focused update of the 2013 guidelines; the first update,3 in 2016, covered 2 new drugs (sacubitril-valsartan and ivabradine) for chronic stage C heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

Rather than focus on new medication classes, this second update provides recommendations regarding:

- Preventing the progression to left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure in patients at high risk (stage A) through screening with B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and aiming for more aggressive blood pressure control

- Inpatient biomarker use

- Medications in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, or diastolic heart failure)

- Blood pressure targets in stage C heart failure

- Managing important comorbidities such as iron deficiency and sleep-disordered breathing to decrease morbidity, improve functional capacity, and enhance quality of life.

These guidelines and the data that underlie them are explored below. We also discuss potential applications to the management of hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

COMMON, COSTLY, AND DEBILITATING

Heart failure—defined by the ACC/AHA as the complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood—remains one of the most common, costly, and debilitating diseases in the United States.2 Based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 2011 to 2014, an estimated 6.5 million US adults have it, with projections of more than 8 million by 2030.4,5 More than 960,000 new cases are thought to occur annually, with a lifetime risk of developing it of roughly 20% to 45%.6

Despite ever-growing familiarity and some significant strides in management, the death rate in this syndrome is substantial. After admissions for heart failure (which number 1 million per year), the mortality rate is roughly 10% at 1 year and 40% at 5 years.6 Also staggering are the associated costs, with $30.7 billion attributed to heart failure in 2012 and a projected $69.7 billion annually by 2030.5 Thus, we must direct efforts not only to treatment, but also to prevention.

Preventive efforts would target patients with ACC/AHA stage A heart failure—those at high risk for developing but currently without evidence of structural heart disease or heart failure symptoms (Table 1).7 This group may represent up to one-third of the US adult population, or 75 million people, when including the well-recognized risk factors of coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease in those without left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure.8

BIOMARKERS FOR PREVENTION

Past ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines2 have included recommendations on the use of biomarkers to aid in diagnosis and prognosis and, to a lesser degree, to guide treatment of heart failure. Largely based on 2 trials (see below), the 2017 guidelines go further, issuing a recommendation on the use of natriuretic peptide biomarkers in a screening strategy to prompt early intervention and prevent the progression to clinical heart failure in high-risk patients (stage A heart failure).

The PONTIAC trial

The NT-proBNP Selected Prevention of Cardiac Events in a Population of Diabetic Patients Without a History of Cardiac Disease (PONTIAC) trial9 randomized 300 outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and an elevated N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) level (> 125 pg/mL) to standard medical care vs standard care plus intensive up-titration of renin-angiotensin system antagonists and beta-blockers in a cardiac clinic over 2 years.

Earlier studies10 had shown NT-proBNP levels to have predictive value for cardiac events in diabetic patients, while the neurohormonal treatments were thought to have an established record of preventing primary and secondary cardiovascular events. In PONTIAC, a significant reduction was seen in the primary end point of hospitalization or death due to cardiac disease (hazard ratio [HR] 0.351, P = .044), as well as in the secondary end point of hospitalization due to heart failure (P < .05), in the aggressive-intervention group. These results laid the foundation for the larger St. Vincent’s Screening to Prevent Heart Failure (STOP-HF) trial.11

The STOP-HF trial

The STOP-HF trial randomized 1,235 outpatients who were at high risk but without left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure symptoms (stage A) to annual screening alone vs annual screening plus BNP testing, in which a BNP level higher than 50 pg/mL triggered echocardiography and evaluation by a cardiologist who would then assist with medications.11

Eligible patients were over age 40 and had 1 or more of the following risk factors:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2)

- Vascular disease (coronary, cerebral, or peripheral arterial disease)

- Arrhythmia requiring treatment

- Moderate to severe valvular disease.

After a mean follow-up of 4.3 years, the primary end point, ie, asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction with or without newly diagnosed heart failure, was found in 9.7% of the control group and in only 5.9% of the intervention group with BNP screening, a 42% relative risk reduction (P = .013).

Similarly, the incidence of secondary end points of emergency hospitalization for a cardiovascular event (arrhythmia, transient ischemic attack, stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral or pulmonary thrombosis or embolization, or heart failure) was also lower at 45.2 vs 24.4 per 1,000 patient-years, a 46% relative risk reduction.

An important difference in medications between the 2 groups was an increase in subsequently prescribed renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system therapy, mainly consisting of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in those with elevated BNP in the intervention group. Notably, blood pressure was about the same in the 2 groups.11

Although these findings are encouraging, larger studies are needed, as the lack of blinding, low event rates, and small absolute risk reduction make the results difficult to generalize.

New or modified recommendations for screening

Employing this novel prevention strategy in the extremely large number of patients with stage A heart failure, thought to be up to one-third of the US adult population, may serve as a way to best direct and utilize limited medical resources.8

BIOMARKERS FOR PROGNOSIS OR ADDED RISK STRATIFICATION

The 2013 guidelines2 recognized that a significant body of work had accumulated showing that natriuretic peptide levels can predict outcomes in both chronic and acute heart failure. Thus, in both conditions, the guidelines contained separate class Ia recommendations to obtain a natriuretic peptide level, troponin level, or both to establish prognosis or disease severity.

The 2017 update1 underscores the importance of timing in measuring natriuretic peptide levels during admission for ADHF, with emphasis on obtaining them at admission and at discharge for acute and postdischarge prognosis. The completely new class IIa recommendation to obtain a predischarge natriuretic peptide level for postdischarge prognosis was based on a number of observational studies, some of which we explore below.

The ELAN-HF meta-analysis

The European Collaboration on Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (ELAN-HF)12 performed a meta-analysis to develop a discharge prognostication score for ADHF that included both absolute level and percent change in natriuretic peptide levels at the time of discharge.

Using data from 7 prospective cohorts totaling 1,301 patients, the authors found that incorporation of these values into a subsequently validated risk model led to significant improvements in the ability to predict the end points of all-cause mortality and the combined end point of all-cause mortality or first readmission for a cardiovascular reason within 180 days.

The OPTIMIZE-HF retrospective analysis

Data from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) were retrospectively analyzed13 to determine whether postdischarge outcomes were best predicted by natriuretic peptide levels at admission or discharge or by the relative change in natriuretic peptide level. More than 7,000 patients age 65 or older, in 220 hospitals, were included, and Cox prediction models were compared using clinical variables alone or in combination with the natriuretic peptide levels.

The model that included the discharge natriuretic peptide level was found to be the most predictive, with a c-index of 0.693 for predicting mortality and a c-index of 0.606 for mortality or rehospitalization at 1 year.

New or modified recommendations on biomarkers for prognosis

The 2017 update1 modified the earlier recommendation to obtain a natriuretic peptide or troponin level or both at admission for ADHF to establish prognosis. This now has a class Ia recommendation, emphasizing that such levels be obtained on admission. In addition, a new class IIa recommendation is made to obtain a predischarge natriuretic peptide level for postdischarge prognosis. The former class Ia recommendation to obtain a natriuretic peptide level in chronic heart failure to establish prognosis or disease severity remains unchanged.

Also worth noting is what the 2017 update does not recommend in regard to obtaining biomarker levels. It emphasizes that many patients, particularly those with advanced (stage D) heart failure, have a poor prognosis that is well established with or without biomarker levels. Additionally, there are many cardiac and noncardiac causes of natriuretic peptide elevation; thus, clinical judgment remains paramount.

The 2017 update1 also cautions against setting targets of percent change in or absolute levels of natriuretic peptide at discharge despite observational and retrospective studies demonstrating better outcomes when levels are reduced, as treating for any specific target has never been studied in a large prospective study. Thus, doing so may result in unintended harm. Rather, clinical judgment and optimization of guideline-directed management and therapy are encouraged (Table 2).

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT FOR STAGE C HFpEF

Although the 2013 guidelines2 contain many class I recommendations for various medications in chronic HFrEF, not a single such recommendation is found for chronic HFpEF. A review by Okwuosa et al7 covered HFrEF, including the most recent additions on which the 2016 update was based, sacubitril-valsartan and ivabradine. The 2016 update was similarly devoid of recommendations regarding specific medications in HFpEF, leaving only the 2013 class IIb recommendation to consider using an ARB to decrease hospitalizations in HFpEF.

Evidence behind this recommendation came from the Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity program’s randomized controlled trial in 3,025 patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II to IV heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction over 40%, who were treated with candesartan or placebo.14 Over a median follow-up of 36.6 months, there was no significant difference in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death or admission for heart failure, but significantly fewer patients in the candesartan arm were admitted (230 vs 270, P = .017). Thus the recommendation.

Although this finding was encouraging, it was clear that no blockbuster drug for HFpEF had been identified. Considering that roughly half of all heart failure patients have preserved ejection fraction, the discovery of such a drug for HFpEF would be met with much excitement.15 Subsequently, other medication classes have been evaluated in the hope of benefit, allowing the 2017 update to provide specific recommendations for aldosterone antagonists, nitrates, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors in HFpEF.

ALDOSTERONE ANTAGONISTS FOR HFpEF