User login

STI update: Testing, treatment, and emerging threats

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are still increasing in incidence and probably will continue to do so in the near future. Moreover, drug-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae are emerging, as are less-known organisms such as Mycoplasma genitalium.

Now the good news: new tests for STIs are available or are coming! Based on nucleic acid amplification, these tests can be performed at the point of care, so that patients can leave the clinic with an accurate diagnosis and proper treatment for themselves and their sexual partners. Also, the tests can be run on samples collected by the patients themselves, either swabs or urine collections, eliminating the need for invasive sampling and making doctor-shy patients more likely to come in to be treated.1 We hope that by using these sensitive and accurate tests we can begin to bend the upward curve of STIs and be better antimicrobial stewards.2

This article reviews current issues surrounding STI control, and provides detailed guidance on recognizing, testing for, and treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and M genitalium infection.

STI RATES ARE HIGH AND RISING

STIs are among the most common acute infectious diseases worldwide, with an estimated 1 million new curable cases every day.3 Further, STIs have major impacts on sexual, reproductive, and psychological health.

In the United States, rates of reportable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) are rising.4 In addition, more-sensitive tests for trichomoniasis, which is not a reportable infection in any state, have revealed it to be more prevalent than previously thought.5

BARRIERS AND CHALLENGES TO DIAGNOSIS

The medical system does not fully meet the needs of some populations, including young people and men who have sex with men, regarding their sexual and reproductive health.

Ongoing barriers among young people include reluctance to use available health services, limited access to STI testing, worries about confidentiality, and the shame and stigma associated with STIs.6

Men who have sex with men have a higher incidence of STIs than other groups. Since STIs are associated with a higher risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, it is important to detect, diagnose, and manage STIs in this group—and in all high-risk groups. Rectal STIs are an independent risk factor for incident HIV infection.7 In addition, many men who have sex with men face challenges navigating the emotional, physical, and cognitive aspects of adolescence, a voyage further complicated by mental health issues, unprotected sexual encounters, and substance abuse in many, especially among minority youth.8 These same factors also impair their ability to access resources for preventing and treating HIV and other STIs.

STI diagnosis is often missed

Most people who have STIs feel no symptoms, which increases the importance of risk-based screening to detect these infections.9,10 In many other cases, STIs manifest with nonspecific genitourinary symptoms that are mistaken for urinary tract infection. Tomas et al11 found that of 264 women who presented to an emergency department with genitourinary symptoms or were being treated for urinary tract infection, 175 were given a diagnosis of a urinary tract infection. Of these, 100 (57%) were treated without performing a urine culture; 60 (23%) of the 264 women had 1 or more positive STI tests, 22 (37%) of whom did not receive treatment for an STI.

Poor follow-up of patients and partners

Patients with STIs need to be retested 3 months after treatment to make sure the treatment was effective. Another reason for follow-up is that these patients are at higher risk of another infection within a year.12

Although treating patients’ partners has been shown to reduce reinfection rates, fewer than one-third of STIs (including HIV infections) were recognized through partner notification between 2010 and 2012 in a Dutch study, in men who have sex with men and in women.13 Challenges included partners who could not be identified among men who have sex with men, failure of heterosexual men to notify their partners, and lower rates of partner notification for HIV.

In the United States, “expedited partner therapy” allows healthcare providers to provide a prescription or medications to partners of patients diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea without examining the partner.14 While this approach is legal in most states, implementation can be challenging.15

STI EVALUATION

History and physical examination

A complete sexual history helps in estimating the patient’s risk of an STI and applying appropriate risk-based screening. Factors such as sexual practices, use of barrier protection, and history of STIs should be discussed.

Physical examination is also important. Although some patients may experience discomfort during a genital or pelvic examination, omitting this step may lead to missed diagnoses in women with STIs.16

Laboratory testing

Laboratory testing for STIs helps ensure accurate diagnosis and treatment. Empiric treatment without testing could give a patient a false sense of health by missing an infection that is not currently causing symptoms but that could later worsen or have lasting complications. Failure to test patients also misses the opportunity for partner notification, linkage to services, and follow-up testing.

Many of the most common STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis, can be detected using vaginal, cervical, or urethral swabs or first-catch urine (from the initial urine stream). In studies that compared various sampling methods,17 self-collected urine samples for gonorrhea in men were nearly as good as clinician-collected swabs of the urethra. In women, self-collected vaginal swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia were nearly as good as clinician-collected vaginal swabs. While urine specimens are acceptable for chlamydia testing in women, their sensitivity may be slightly lower than with vaginal and endocervical swab specimens.18,19

A major advantage of urine specimens for STI testing is that collection is noninvasive and is therefore more likely to be acceptable to patients. Urine testing can also be conducted in a variety of nonclinical settings such as health fairs, pharmacy-based screening programs, and express STI testing sites, thus increasing availability.

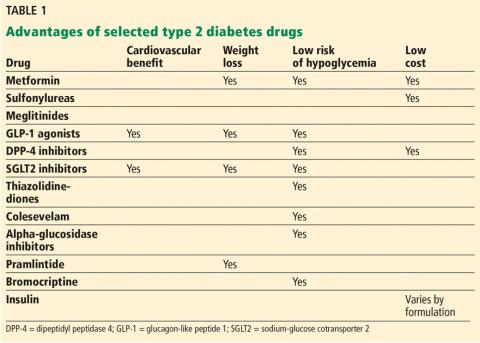

To prevent further transmission and morbidity and to aid in public health efforts, it is critical to recognize the cause of infectious cervicitis and urethritis and to screen for STIs according to guidelines.12 Table 1 summarizes current screening and laboratory testing recommendations.

GONORRHEA AND CHLAMYDIA

Gonorrhea and chlamydia are the 2 most frequently reported STIs in the United States, with more than 550,000 cases of gonorrhea and 1.7 million cases of chlamydia reported in 2017.4

Both infections present similarly: cervicitis or urethritis characterized by discharge (mucopurulent discharge with gonorrhea) and dysuria. Untreated, they can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammation, and infertility.

Extragenital infections can be asymptomatic or cause exudative pharyngitis or proctitis. Most people in whom chlamydia is detected from pharyngeal specimens are asymptomatic. When pharyngeal symptoms exist secondary to gonorrheal infection, they typically include sore throat and pharyngeal exudates. However, Komaroff et al,20 in a study of 192 men and women who presented with sore throat, found that only 2 (1%) tested positive for N gonorrhoeae.

Screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia

Best practices include screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia as follows21–23:

- Every year in sexually active women through age 25 (including during pregnancy) and in older women who have risk factors for infection12

- At least every year in men who have sex with men, at all sites of sexual contact (urethra, pharynx, rectum), along with testing for HIV and syphilis

- Every 3 to 6 months in men who have sex with men who have multiple or anonymous partners, who are sexually active and use illicit drugs, or who have partners who use illicit drugs

- Possibly every year in young men who live in high-prevalence areas or who are seen in certain clinical settings, such as STI and adolescent clinics.

Specimens. A vaginal swab is preferred for screening in women. Several studies have shown that self-collected swabs have clinical sensitivity and specificity comparable to that of provider-collected samples.17,24 First-catch urine or endocervical swabs have similar performance characteristics and are also acceptable. In men, urethral swabs or first-catch urine samples are appropriate for screening for urogenital infections.

Testing methods. Testing for both pathogens should be done simultaneously with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Commercially available NAATs are more sensitive than culture and antigen testing for detecting gonorrhea and chlamydia.25–27

Most assays are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for testing vaginal, urethral, cervical, and urine specimens. Until recently, no commercial assay was cleared for testing extragenital sites, but recommendations for screening extragenital sites prompted many clinical laboratories to validate throat and rectal swabs for use with NAATs, which are more sensitive than culture at these sites.25,28 The recent FDA approval of extragenital specimen types for 2 commercially available assays may increase the availability of testing for these sites.

Data on the utility of NAATs for detecting chlamydia and gonorrhea in children are limited, and many clinical laboratories have not validated molecular methods for testing in children. Current guidelines specific to this population should be followed regarding test methods and preferred specimen types.12,29,30

Although gonococcal infection is usually diagnosed with culture-independent molecular methods, antimicrobial resistance is emerging. Thus, failure of the combination of ceftriaxone and azithromycin should prompt culture-based follow-up testing to determine antimicrobial susceptibility.

Strategies for treatment and control

Historically, people treated for gonorrhea have been treated for chlamydia at the same time, as these diseases tend to go together. This can be with a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone for the gonorrhea plus a single oral dose of azithromycin for the chlamydia.12 For patients who have only gonorrhea, this double regimen may help prevent the development of resistant gonorrhea strains.

All the patient’s sexual partners in the previous 60 days should be tested and treated, and expedited partner therapy should be offered if possible. Patients should be advised to have no sexual contact until they complete the treatment, or 7 days after single-dose treatment. Testing should be repeated 3 months after treatment.

M GENITALIUM IS EMERGING

A member of the Mycoplasmataceae family, M genitalium was originally identified as a pathogen in the early 1980s but has only recently emerged as an important cause of STI. Studies indicate that it is responsible for 10% to 20% of cases of nongonococcal urethritis and 10% to 30% of cases of cervicitis.31–33 Additionally, 2% to 22% of cases of pelvic inflammatory disease have evidence of M genitalium.34,35

However, data on M genitalium prevalence are suspect because the organism is hard to identify—lacking a cell wall, it is undetectable by Gram stain.36 Although it has been isolated in respiratory and synovial fluids, it has so far been recognized to be clinically important only in the urogenital tract. It can persist for years in infected patients by exploiting specialized cell-surface structures to invade cells.36 Once inside a cell, it triggers secretion of mycoplasmal toxins and destructive metabolites such as hydrogen peroxide, evading the host immune system as it does so.37

Testing guidelines for M genitalium

Current guidelines do not recommend routine screening for M genitalium, and no commercial test was available until recently.12 Although evidence suggests that M genitalium is independently associated with preterm birth and miscarriages,38 routine screening of pregnant women is not recommended.12

Testing for M genitalium should be considered in cases of persistent or recurrent nongonococcal urethritis in patients who test negative for gonorrhea and chlamydia or for whom treatment has failed.12 Many isolates exhibit genotypic resistance to macrolide antibiotics, which are often the first-line therapy for nongonococcal urethritis.39

Further study is needed to evaluate the potential impact of routine screening for M genitalium on the reproductive and sexual health of at-risk populations.

Diagnostic tests for M genitalium

Awareness of M genitalium as a cause of nongonococcal urethritis has been hampered by a dearth of diagnostic tests.40 The organism’s fastidious requirements and extremely slow growth preclude culture as a practical method of diagnosis.41 Serologic assays are dogged by cross-reactivity and poor sensitivity.42,43 Thus, molecular assays for detecting M genitalium and associated resistance markers are preferred for diagnosis.12

Several molecular tests are approved, available, and in use in Europe for diagnosing M genitalium infection,40 and in January 2019 the FDA approved a molecular test that can detect M genitalium in urine specimens and vaginal, endocervical, urethral, and penile meatal swabs. Although vaginal swabs are preferred for this assay because they have higher sensitivity (92% for provider-collected and 99% for patient-collected swabs), urine specimens are acceptable, with a sensitivity of 78%.44

At least 1 company is seeking FDA clearance for another molecular diagnostic assay for detecting M genitalium and markers of macrolide resistance in urine and genital swab specimens. Such assays may facilitate appropriate treatment.

Clinicians should stay abreast of diagnostic testing options, which are likely to become more readily available soon.

A high rate of macrolide resistance

Because M genitalium lacks a cell wall, antibiotics such as beta-lactams that target cell wall synthesis are ineffective.

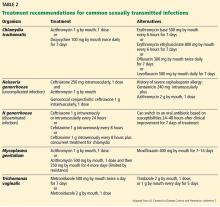

Regimens for treating M genitalium are outlined in Table 2.12 Azithromycin is more effective than doxycycline. However, as many as 50% of strains were macrolide-resistant in a cohort of US female patients.45 Given the high incidence of treatment failure with azithromycin 1 g, it is thought that this regimen might select for resistance. For cases in which symptoms persist, a 1- to 2-week course of moxifloxacin is recommended.12 However, this has not been validated by clinical trials, and failures of the 7-day regimen have been reported.46

Partners of patients who test positive for M genitalium should also be tested and undergo clinically applicable screening for nongonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.12

TRICHOMONIASIS

Trichomoniasis, caused by the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis, is the most prevalent nonviral STI in the United States. It disproportionately affects black women, in whom the prevalence is 13%, compared with 1% in non-Hispanic white women.47 It is also present in 26% of women with symptoms who are seen in STI clinics and is highly prevalent in incarcerated populations. It is uncommon in men who have sex with men.48

In men, trichomoniasis manifests as urethritis, epididymitis, or prostatitis. While most infected women have no symptoms, they may experience vaginitis with discharge that is diffuse, frothy, pruritic, malodorous, or yellow-green. Vaginal and cervical erythema (“strawberry cervix”) can also occur.

Screening for trichomoniasis

Current guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend testing for T vaginalis in women who have symptoms and routinely screening in women who are HIV-positive, regardless of symptoms. There is no evidence to support routine screening of pregnant women without symptoms, and pregnant women who do have symptoms should be evaluated according to the same guidelines as for nonpregnant women.12 Testing can be considered in patients who have no symptoms but who engage in high-risk behaviors and in areas of high prevalence.

A lack of studies using sensitive methods for T vaginalis detection has hampered a true estimation of disease burden and at-risk populations. Screening recommendations may evolve in upcoming clinical guidelines as the field advances.

As infection can recur, women should be retested 3 months after initial diagnosis.12

NAAT is the preferred test for trichomoniasis

Commercially available diagnostic tests for trichomoniasis include culture, antigen testing, and NAAT.49 While many clinicians do their own wet-mount microscopy for a rapid result, this method has low sensitivity.50 Similarly, antigen testing and culture perform poorly compared with NAATs, which are the gold standard for detection.51,52 A major advantage of NAATs for T vaginalis detection is that they combine high sensitivity and fast results, facilitating diagnosis and appropriate treatment of patients and their partners.

In spite of these benefits, adoption of molecular diagnostic testing for T vaginalis has lagged behind that for chlamydia and gonorrhea.53 FDA-cleared NAATs are available for testing vaginal, cervical, or urine specimens from women, but until recently, there were no approved assays for testing in men. The Cepheid Xpert TV assay, which is valid for male urine specimens to diagnose other sexually transmitted diseases, has demonstrated excellent diagnostic sensitivity for T vaginalis in men and women.54 Interestingly, a large proportion of male patients in this study had no symptoms, suggesting that screening of men in high-risk groups may be warranted.

7-day metronidazole treatment beats single-dose treatment

The first-line treatment for trichomoniasis has been a single dose of metronidazole 2 g by mouth, but in a recent randomized controlled trial,55 a course of 500 mg by mouth twice a day for 7 days was 45% more effective at 4 weeks than a single dose, and it should now be the preferred regimen.

In clinical trials,56 a single dose of tinidazole 2 g orally was equivalent or superior to metronidazole 2 g and had fewer gastrointestinal side effects, but it is more expensive.

- Harding-Esch EM, Nori AV, Hegazi A, et al. Impact of deploying multiple point-of-care tests with a ‘sample first’ approach on a sexual health clinical care pathway. A service evaluation. Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93(6):424–429. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2016-052988

- Unemo M, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17(8):e235–e279. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30310-9

- Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 2015; 10(12):e0143304. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143304

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2017. www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/toc.htm. Accessed October 7, 2019.

- Ginocchio CC, Chapin K, Smith JS, et al. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis and coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States as determined by the Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50(8):2601–2608. doi:10.1128/JCM.00748-12

- Newton-Levinson A, Leichliter JS, Chandra-Mouli V. Sexually transmitted infection services for adolescents and youth in low- and middle-income countries: perceived and experienced barriers to accessing care. J Adolesc Health 2016; 59(1):7–16.

doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.014 - Barbee LA, Khosropour CM, Dombrowksi JC, Golden MR. New human immunodeficiency virus diagnosis independently associated with rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44(7):385–389. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000614

- Halkitis PN, Kapadia F, Bub KL, Barton S, Moreira AD, Stults CB. A longitudinal investigation of syndemic conditions among young gay, bisexual, and other MSM: the P18 cohort study. AIDS Behav 2015; 19(6):970–980. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0892-y

- Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Prev Med 2003; 36(4):502–509. pmid:12649059

- Patel P, Bush T, Mayer K, et al; SUN Study Investigators. Routine brief risk-reduction counseling with biannual STD testing reduces STD incidence among HIV-infected men who have sex with men in care. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39(6):470–474. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31824b3110

- Tomas ME, Getman D, Donskey CJ, Hecker MT. Overdiagnosis of urinary tract infection and underdiagnosis of sexually transmitted infection in adult women presenting to an emergency department. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53(8):2686–2692. doi:10.1128/JCM.00670-15

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64(RR–03): 1–137. pmid:26042815

- van Aar F, van Weert Y, Spijker R, Gotz H, Op de Coul E; Partner Notification Group. Partner notification among men who have sex with men and heterosexuals with STI/HIV: different outcomes and challenges. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26(8):565–573. doi:10.1177/0956462414547398

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDa): expedited partner therapy. www.cdc.gov/std/ept/. Accessed October 7, 2019.

- Jamison CD, Chang T, Mmeje O. Expedited partner therapy: combating record high sexually transmitted infection rates. Am J Public Health 2018; 108(10):1325–1327. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304570

- Singh RH, Zenilman JM, Brown KM, Madden T, Gaydos C, Ghanem KG. The role of physical examination in diagnosing common causes of vaginitis: a prospective study. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89(3):185–190. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2012-050550

- Lunny C, Taylor D, Hoang L, et al. Self-collected versus clinician-collected sampling for chlamydia and gonorrhea screening: a systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10(7):e0132776. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132776

- Michel CE, Sonnex C, Carne CA, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis load at matched anatomic sites: implications for screening strategies. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45(5):1395–1402. doi:10.1128/JCM.00100-07

- Schachter J, Chernesky MA, Willis DE, et al. Vaginal swabs are the specimens of choice when screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: results from a multicenter evaluation of the APTIMA assays for both infections. Sex Transm Dis 2005; 32(12):725–728. pmid:16314767

- Komaroff AL, Aronson MD, Pass TM, Ervin CT. Prevalence of pharyngeal gonorrhea in general medical patients with sore throats. Sex Transm Dis 1980; 7(3):116–119. pmid:6777884

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinic-based testing for rectal and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections by community-based organizations—five cities, United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58(26):716–719. pmid:19590491

- Chesson HW, Bernstein KT, Gift TL, Marcus JL, Pipkin S, Kent CK. The cost-effectiveness of screening men who have sex with men for rectal chlamydial and gonococcal infection to prevent HIV Infection. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40(5):366–471. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318284e544

- Park J, Marcus JL, Pandori M, Snell A, Philip SS, Bernstein KT. Sentinel surveillance for pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea among men who have sex with men—San Francisco, 2010. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39(6):482–484. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182495e2f

- Masek BJ, Arora N, Quinn N, et al. Performance of three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by use of self-collected vaginal swabs obtained via an internet-based screening program. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47(6):1663–1667. doi:10.1128/JCM.02387-08

- Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis rectal infections. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48(5):1827–1832. doi:10.1128/JCM.02398-09

- Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Reisner SL, et al. Asymptomatic gonorrhea and chlamydial infections detected by nucleic acid amplification tests among Boston area men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35(5):495–498. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816471ae

- Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, Shayevich C, Klausner JD. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35(7):637–642. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31817bdd7e

- Cornelisse VJ, Chow EP, Huffam S, et al. Increased detection of pharyngeal and rectal gonorrhea in men who have sex with men after transition from culture to nucleic acid amplification testing. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44(2):114–117. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000553

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae—2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014; 63(RR–02):1–19. pmid:24622331

- Hammerschlag MR, Gaydos CA. Guidelines for the use of molecular biological methods to detect sexually transmitted pathogens in cases of suspected sexual abuse in children. Methods Mol Biol 2012; 903:307–317. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-937-2_21

- Huppert JS, Mortensen JE, Reed JL, Kahn JA, Rich KD, Hobbs MM. Mycoplasma genitalium detected by transcription-mediated amplification is associated with Chlamydia trachomatis in adolescent women. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35(3):250–254. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815abac6

- Pond MJ, Nori AV, Witney AA, Lopeman RC, Butcher PD, Sadiq ST. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in nongonococcal urethritis: the need for routine testing and the inadequacy of current treatment options. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(5):631–637. doi:10.1093/cid/cit752

- Seña AC, Lee JY, Schwebke J, et al. A silent epidemic: the prevalence, incidence and persistence of Mycoplasma genitalium among young, asymptomatic high-risk women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(1):73–79. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy025

- Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG 2010; 117(3):361–364. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02455.x

- Cohen CR, Manhart LE, Bukusi EA, et al. Association between Mycoplasma genitalium and acute endometritis. Lancet 2002; 359(9308):765–766. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07848-0

- Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24(3):498–514. doi:10.1128/CMR.00006-11

- Ross JD, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium as a sexually transmitted infection: implications for screening, testing, and treatment. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82(4):269–271. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.017368

- Donders GG, Ruban K, Bellen G, Petricevic L. Mycoplasma/ureaplasma infection in pregnancy: to screen or not to screen. J Perinat Med 2017; 45(5):505–515. doi:10.1515/jpm-2016-0111

- Allan-Blitz LT, Mokany E, Miller S, Wee R, Shannon C, Klausner JD. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium and azithromycin-resistant infections among remnant clinical specimens, Los Angeles. Sex Transm Dis 2018; 45(9):632–635. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000829

- Munson E. Molecular diagnostics update for the emerging (if not already widespread) sexually transmitted infection agent Mycoplasma genitalium: just about ready for prime time. J Clin Microbio. 2017; 55(10):2894–2902. doi:10.1128/JCM.00818-17

- Waites KB, Taylor-Robinson D. Mycoplasma and ureaplasma. In: Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC, American Society for Microbiology, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 11th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2015:1088–1105.

- Cimolai N, Bryan LE, To M, Woods DE. Immunological cross-reactivity of a Mycoplasma pneumoniae membrane-associated protein antigen with Mycoplasma genitalium and Acholeplasma laidlawii. J Clin Microbiol 1987; 25(11):2136–2139. pmid:2447119

- Ma L, Mancuso M, Williams JA, et al. Extensive variation and rapid shift of the MG192 sequence in Mycoplasma genitalium strains from patients with chronic infection. Infect Immun 2014; 82(3):1326–1334. doi:10.1128/IAI.01526-13

- Hologic. Aptima Mycoplasma genitalium assay.www.hologic.com/sites/default/files/package-insert/AW-14170-001_005_01.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2019.

- Getman D, Jiang A, O’Donnell M, Cohen S. Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence, coinfection, and macrolide antibiotic resistance frequency in a multicenter clinical study cohort in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54(9):2278–2283. doi:10.1128/JCM.01053-16

- Li Y, Le WJ, Li S, Cao YP, Su XH. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of moxifloxacin in treating Mycoplasma genitalium infection. Int J STD AIDS 2017; 28(11):1106–1114. doi:10.1177/0956462416688562

- Sutton M, Sternberg M, Koumans EH, McQuillan G, Berman S, Markowitz L. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001–2004. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(10):1319–1326. doi:10.1086/522532

- Kelley CF, Rosenberg ES, O’Hara BM, Sanchez T, del Rio C, Sullivan PS. Prevalence of urethral Trichomonas vaginalis in black and white men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39(9):739. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318264248b

- Van Der Pol B. Clinical and laboratory testing for T vaginalis infection. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54(1):7–12. doi:10.1128/JCM.02025-15

- Nye MB, Schwebke JR, Body BA. Comparison of APTIMA Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification to wet mount microscopy, culture, and polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of trichomoniasis in men and women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 200(2):188.e1–e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.005

- Andrea SB, Chapin KC. Comparison of Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification assay and BD affirm VPIII for detection of T. vaginalis in symptomatic women: performance parameters and epidemiological implications. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49(3):866–869. doi:10.1128/JCM.02367-10

- Schwebke JR, Hobbs MM, Taylor SN, et al. Molecular testing for Trichomonas vaginalis in women: results from a prospective U.S. clinical trial. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49(12):4106–4111. doi:10.1128/JCM.01291-11

- College of American Pathologists. CAP surveys, Trichomonas vaginalis molecular, set TVAG-A. https://documents.cap.org/documents/2018-surveys-anatomic-pathology-ed-programs-catalog.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

- Schwebke JR, Gaydos CA, Davis T, et al. Clinical evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert TV assay for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis with prospectively collected specimens from men and women. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56(2). doi:10.1128/JCM.01091-17

- Kissinger P, Muzny CA, Mena LA, et al. Single-dose versus 7-day-dose metronidazole for the treatment of trichomoniasis in women: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18(11):1251–1259. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30423-7

- Forna F, Gulmezoglu AM. Interventions for treating trichomoniasis in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (2):CD000218. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000218

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are still increasing in incidence and probably will continue to do so in the near future. Moreover, drug-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae are emerging, as are less-known organisms such as Mycoplasma genitalium.

Now the good news: new tests for STIs are available or are coming! Based on nucleic acid amplification, these tests can be performed at the point of care, so that patients can leave the clinic with an accurate diagnosis and proper treatment for themselves and their sexual partners. Also, the tests can be run on samples collected by the patients themselves, either swabs or urine collections, eliminating the need for invasive sampling and making doctor-shy patients more likely to come in to be treated.1 We hope that by using these sensitive and accurate tests we can begin to bend the upward curve of STIs and be better antimicrobial stewards.2

This article reviews current issues surrounding STI control, and provides detailed guidance on recognizing, testing for, and treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and M genitalium infection.

STI RATES ARE HIGH AND RISING

STIs are among the most common acute infectious diseases worldwide, with an estimated 1 million new curable cases every day.3 Further, STIs have major impacts on sexual, reproductive, and psychological health.

In the United States, rates of reportable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) are rising.4 In addition, more-sensitive tests for trichomoniasis, which is not a reportable infection in any state, have revealed it to be more prevalent than previously thought.5

BARRIERS AND CHALLENGES TO DIAGNOSIS

The medical system does not fully meet the needs of some populations, including young people and men who have sex with men, regarding their sexual and reproductive health.

Ongoing barriers among young people include reluctance to use available health services, limited access to STI testing, worries about confidentiality, and the shame and stigma associated with STIs.6

Men who have sex with men have a higher incidence of STIs than other groups. Since STIs are associated with a higher risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, it is important to detect, diagnose, and manage STIs in this group—and in all high-risk groups. Rectal STIs are an independent risk factor for incident HIV infection.7 In addition, many men who have sex with men face challenges navigating the emotional, physical, and cognitive aspects of adolescence, a voyage further complicated by mental health issues, unprotected sexual encounters, and substance abuse in many, especially among minority youth.8 These same factors also impair their ability to access resources for preventing and treating HIV and other STIs.

STI diagnosis is often missed

Most people who have STIs feel no symptoms, which increases the importance of risk-based screening to detect these infections.9,10 In many other cases, STIs manifest with nonspecific genitourinary symptoms that are mistaken for urinary tract infection. Tomas et al11 found that of 264 women who presented to an emergency department with genitourinary symptoms or were being treated for urinary tract infection, 175 were given a diagnosis of a urinary tract infection. Of these, 100 (57%) were treated without performing a urine culture; 60 (23%) of the 264 women had 1 or more positive STI tests, 22 (37%) of whom did not receive treatment for an STI.

Poor follow-up of patients and partners

Patients with STIs need to be retested 3 months after treatment to make sure the treatment was effective. Another reason for follow-up is that these patients are at higher risk of another infection within a year.12

Although treating patients’ partners has been shown to reduce reinfection rates, fewer than one-third of STIs (including HIV infections) were recognized through partner notification between 2010 and 2012 in a Dutch study, in men who have sex with men and in women.13 Challenges included partners who could not be identified among men who have sex with men, failure of heterosexual men to notify their partners, and lower rates of partner notification for HIV.

In the United States, “expedited partner therapy” allows healthcare providers to provide a prescription or medications to partners of patients diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea without examining the partner.14 While this approach is legal in most states, implementation can be challenging.15

STI EVALUATION

History and physical examination

A complete sexual history helps in estimating the patient’s risk of an STI and applying appropriate risk-based screening. Factors such as sexual practices, use of barrier protection, and history of STIs should be discussed.

Physical examination is also important. Although some patients may experience discomfort during a genital or pelvic examination, omitting this step may lead to missed diagnoses in women with STIs.16

Laboratory testing

Laboratory testing for STIs helps ensure accurate diagnosis and treatment. Empiric treatment without testing could give a patient a false sense of health by missing an infection that is not currently causing symptoms but that could later worsen or have lasting complications. Failure to test patients also misses the opportunity for partner notification, linkage to services, and follow-up testing.

Many of the most common STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis, can be detected using vaginal, cervical, or urethral swabs or first-catch urine (from the initial urine stream). In studies that compared various sampling methods,17 self-collected urine samples for gonorrhea in men were nearly as good as clinician-collected swabs of the urethra. In women, self-collected vaginal swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia were nearly as good as clinician-collected vaginal swabs. While urine specimens are acceptable for chlamydia testing in women, their sensitivity may be slightly lower than with vaginal and endocervical swab specimens.18,19

A major advantage of urine specimens for STI testing is that collection is noninvasive and is therefore more likely to be acceptable to patients. Urine testing can also be conducted in a variety of nonclinical settings such as health fairs, pharmacy-based screening programs, and express STI testing sites, thus increasing availability.

To prevent further transmission and morbidity and to aid in public health efforts, it is critical to recognize the cause of infectious cervicitis and urethritis and to screen for STIs according to guidelines.12 Table 1 summarizes current screening and laboratory testing recommendations.

GONORRHEA AND CHLAMYDIA

Gonorrhea and chlamydia are the 2 most frequently reported STIs in the United States, with more than 550,000 cases of gonorrhea and 1.7 million cases of chlamydia reported in 2017.4

Both infections present similarly: cervicitis or urethritis characterized by discharge (mucopurulent discharge with gonorrhea) and dysuria. Untreated, they can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammation, and infertility.

Extragenital infections can be asymptomatic or cause exudative pharyngitis or proctitis. Most people in whom chlamydia is detected from pharyngeal specimens are asymptomatic. When pharyngeal symptoms exist secondary to gonorrheal infection, they typically include sore throat and pharyngeal exudates. However, Komaroff et al,20 in a study of 192 men and women who presented with sore throat, found that only 2 (1%) tested positive for N gonorrhoeae.

Screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia

Best practices include screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia as follows21–23:

- Every year in sexually active women through age 25 (including during pregnancy) and in older women who have risk factors for infection12

- At least every year in men who have sex with men, at all sites of sexual contact (urethra, pharynx, rectum), along with testing for HIV and syphilis

- Every 3 to 6 months in men who have sex with men who have multiple or anonymous partners, who are sexually active and use illicit drugs, or who have partners who use illicit drugs

- Possibly every year in young men who live in high-prevalence areas or who are seen in certain clinical settings, such as STI and adolescent clinics.

Specimens. A vaginal swab is preferred for screening in women. Several studies have shown that self-collected swabs have clinical sensitivity and specificity comparable to that of provider-collected samples.17,24 First-catch urine or endocervical swabs have similar performance characteristics and are also acceptable. In men, urethral swabs or first-catch urine samples are appropriate for screening for urogenital infections.

Testing methods. Testing for both pathogens should be done simultaneously with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Commercially available NAATs are more sensitive than culture and antigen testing for detecting gonorrhea and chlamydia.25–27

Most assays are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for testing vaginal, urethral, cervical, and urine specimens. Until recently, no commercial assay was cleared for testing extragenital sites, but recommendations for screening extragenital sites prompted many clinical laboratories to validate throat and rectal swabs for use with NAATs, which are more sensitive than culture at these sites.25,28 The recent FDA approval of extragenital specimen types for 2 commercially available assays may increase the availability of testing for these sites.

Data on the utility of NAATs for detecting chlamydia and gonorrhea in children are limited, and many clinical laboratories have not validated molecular methods for testing in children. Current guidelines specific to this population should be followed regarding test methods and preferred specimen types.12,29,30

Although gonococcal infection is usually diagnosed with culture-independent molecular methods, antimicrobial resistance is emerging. Thus, failure of the combination of ceftriaxone and azithromycin should prompt culture-based follow-up testing to determine antimicrobial susceptibility.

Strategies for treatment and control

Historically, people treated for gonorrhea have been treated for chlamydia at the same time, as these diseases tend to go together. This can be with a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone for the gonorrhea plus a single oral dose of azithromycin for the chlamydia.12 For patients who have only gonorrhea, this double regimen may help prevent the development of resistant gonorrhea strains.

All the patient’s sexual partners in the previous 60 days should be tested and treated, and expedited partner therapy should be offered if possible. Patients should be advised to have no sexual contact until they complete the treatment, or 7 days after single-dose treatment. Testing should be repeated 3 months after treatment.

M GENITALIUM IS EMERGING

A member of the Mycoplasmataceae family, M genitalium was originally identified as a pathogen in the early 1980s but has only recently emerged as an important cause of STI. Studies indicate that it is responsible for 10% to 20% of cases of nongonococcal urethritis and 10% to 30% of cases of cervicitis.31–33 Additionally, 2% to 22% of cases of pelvic inflammatory disease have evidence of M genitalium.34,35

However, data on M genitalium prevalence are suspect because the organism is hard to identify—lacking a cell wall, it is undetectable by Gram stain.36 Although it has been isolated in respiratory and synovial fluids, it has so far been recognized to be clinically important only in the urogenital tract. It can persist for years in infected patients by exploiting specialized cell-surface structures to invade cells.36 Once inside a cell, it triggers secretion of mycoplasmal toxins and destructive metabolites such as hydrogen peroxide, evading the host immune system as it does so.37

Testing guidelines for M genitalium

Current guidelines do not recommend routine screening for M genitalium, and no commercial test was available until recently.12 Although evidence suggests that M genitalium is independently associated with preterm birth and miscarriages,38 routine screening of pregnant women is not recommended.12

Testing for M genitalium should be considered in cases of persistent or recurrent nongonococcal urethritis in patients who test negative for gonorrhea and chlamydia or for whom treatment has failed.12 Many isolates exhibit genotypic resistance to macrolide antibiotics, which are often the first-line therapy for nongonococcal urethritis.39

Further study is needed to evaluate the potential impact of routine screening for M genitalium on the reproductive and sexual health of at-risk populations.

Diagnostic tests for M genitalium

Awareness of M genitalium as a cause of nongonococcal urethritis has been hampered by a dearth of diagnostic tests.40 The organism’s fastidious requirements and extremely slow growth preclude culture as a practical method of diagnosis.41 Serologic assays are dogged by cross-reactivity and poor sensitivity.42,43 Thus, molecular assays for detecting M genitalium and associated resistance markers are preferred for diagnosis.12

Several molecular tests are approved, available, and in use in Europe for diagnosing M genitalium infection,40 and in January 2019 the FDA approved a molecular test that can detect M genitalium in urine specimens and vaginal, endocervical, urethral, and penile meatal swabs. Although vaginal swabs are preferred for this assay because they have higher sensitivity (92% for provider-collected and 99% for patient-collected swabs), urine specimens are acceptable, with a sensitivity of 78%.44

At least 1 company is seeking FDA clearance for another molecular diagnostic assay for detecting M genitalium and markers of macrolide resistance in urine and genital swab specimens. Such assays may facilitate appropriate treatment.

Clinicians should stay abreast of diagnostic testing options, which are likely to become more readily available soon.

A high rate of macrolide resistance

Because M genitalium lacks a cell wall, antibiotics such as beta-lactams that target cell wall synthesis are ineffective.

Regimens for treating M genitalium are outlined in Table 2.12 Azithromycin is more effective than doxycycline. However, as many as 50% of strains were macrolide-resistant in a cohort of US female patients.45 Given the high incidence of treatment failure with azithromycin 1 g, it is thought that this regimen might select for resistance. For cases in which symptoms persist, a 1- to 2-week course of moxifloxacin is recommended.12 However, this has not been validated by clinical trials, and failures of the 7-day regimen have been reported.46

Partners of patients who test positive for M genitalium should also be tested and undergo clinically applicable screening for nongonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.12

TRICHOMONIASIS

Trichomoniasis, caused by the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis, is the most prevalent nonviral STI in the United States. It disproportionately affects black women, in whom the prevalence is 13%, compared with 1% in non-Hispanic white women.47 It is also present in 26% of women with symptoms who are seen in STI clinics and is highly prevalent in incarcerated populations. It is uncommon in men who have sex with men.48

In men, trichomoniasis manifests as urethritis, epididymitis, or prostatitis. While most infected women have no symptoms, they may experience vaginitis with discharge that is diffuse, frothy, pruritic, malodorous, or yellow-green. Vaginal and cervical erythema (“strawberry cervix”) can also occur.

Screening for trichomoniasis

Current guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend testing for T vaginalis in women who have symptoms and routinely screening in women who are HIV-positive, regardless of symptoms. There is no evidence to support routine screening of pregnant women without symptoms, and pregnant women who do have symptoms should be evaluated according to the same guidelines as for nonpregnant women.12 Testing can be considered in patients who have no symptoms but who engage in high-risk behaviors and in areas of high prevalence.

A lack of studies using sensitive methods for T vaginalis detection has hampered a true estimation of disease burden and at-risk populations. Screening recommendations may evolve in upcoming clinical guidelines as the field advances.

As infection can recur, women should be retested 3 months after initial diagnosis.12

NAAT is the preferred test for trichomoniasis

Commercially available diagnostic tests for trichomoniasis include culture, antigen testing, and NAAT.49 While many clinicians do their own wet-mount microscopy for a rapid result, this method has low sensitivity.50 Similarly, antigen testing and culture perform poorly compared with NAATs, which are the gold standard for detection.51,52 A major advantage of NAATs for T vaginalis detection is that they combine high sensitivity and fast results, facilitating diagnosis and appropriate treatment of patients and their partners.

In spite of these benefits, adoption of molecular diagnostic testing for T vaginalis has lagged behind that for chlamydia and gonorrhea.53 FDA-cleared NAATs are available for testing vaginal, cervical, or urine specimens from women, but until recently, there were no approved assays for testing in men. The Cepheid Xpert TV assay, which is valid for male urine specimens to diagnose other sexually transmitted diseases, has demonstrated excellent diagnostic sensitivity for T vaginalis in men and women.54 Interestingly, a large proportion of male patients in this study had no symptoms, suggesting that screening of men in high-risk groups may be warranted.

7-day metronidazole treatment beats single-dose treatment

The first-line treatment for trichomoniasis has been a single dose of metronidazole 2 g by mouth, but in a recent randomized controlled trial,55 a course of 500 mg by mouth twice a day for 7 days was 45% more effective at 4 weeks than a single dose, and it should now be the preferred regimen.

In clinical trials,56 a single dose of tinidazole 2 g orally was equivalent or superior to metronidazole 2 g and had fewer gastrointestinal side effects, but it is more expensive.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are still increasing in incidence and probably will continue to do so in the near future. Moreover, drug-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae are emerging, as are less-known organisms such as Mycoplasma genitalium.

Now the good news: new tests for STIs are available or are coming! Based on nucleic acid amplification, these tests can be performed at the point of care, so that patients can leave the clinic with an accurate diagnosis and proper treatment for themselves and their sexual partners. Also, the tests can be run on samples collected by the patients themselves, either swabs or urine collections, eliminating the need for invasive sampling and making doctor-shy patients more likely to come in to be treated.1 We hope that by using these sensitive and accurate tests we can begin to bend the upward curve of STIs and be better antimicrobial stewards.2

This article reviews current issues surrounding STI control, and provides detailed guidance on recognizing, testing for, and treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and M genitalium infection.

STI RATES ARE HIGH AND RISING

STIs are among the most common acute infectious diseases worldwide, with an estimated 1 million new curable cases every day.3 Further, STIs have major impacts on sexual, reproductive, and psychological health.

In the United States, rates of reportable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) are rising.4 In addition, more-sensitive tests for trichomoniasis, which is not a reportable infection in any state, have revealed it to be more prevalent than previously thought.5

BARRIERS AND CHALLENGES TO DIAGNOSIS

The medical system does not fully meet the needs of some populations, including young people and men who have sex with men, regarding their sexual and reproductive health.

Ongoing barriers among young people include reluctance to use available health services, limited access to STI testing, worries about confidentiality, and the shame and stigma associated with STIs.6

Men who have sex with men have a higher incidence of STIs than other groups. Since STIs are associated with a higher risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, it is important to detect, diagnose, and manage STIs in this group—and in all high-risk groups. Rectal STIs are an independent risk factor for incident HIV infection.7 In addition, many men who have sex with men face challenges navigating the emotional, physical, and cognitive aspects of adolescence, a voyage further complicated by mental health issues, unprotected sexual encounters, and substance abuse in many, especially among minority youth.8 These same factors also impair their ability to access resources for preventing and treating HIV and other STIs.

STI diagnosis is often missed

Most people who have STIs feel no symptoms, which increases the importance of risk-based screening to detect these infections.9,10 In many other cases, STIs manifest with nonspecific genitourinary symptoms that are mistaken for urinary tract infection. Tomas et al11 found that of 264 women who presented to an emergency department with genitourinary symptoms or were being treated for urinary tract infection, 175 were given a diagnosis of a urinary tract infection. Of these, 100 (57%) were treated without performing a urine culture; 60 (23%) of the 264 women had 1 or more positive STI tests, 22 (37%) of whom did not receive treatment for an STI.

Poor follow-up of patients and partners

Patients with STIs need to be retested 3 months after treatment to make sure the treatment was effective. Another reason for follow-up is that these patients are at higher risk of another infection within a year.12

Although treating patients’ partners has been shown to reduce reinfection rates, fewer than one-third of STIs (including HIV infections) were recognized through partner notification between 2010 and 2012 in a Dutch study, in men who have sex with men and in women.13 Challenges included partners who could not be identified among men who have sex with men, failure of heterosexual men to notify their partners, and lower rates of partner notification for HIV.

In the United States, “expedited partner therapy” allows healthcare providers to provide a prescription or medications to partners of patients diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea without examining the partner.14 While this approach is legal in most states, implementation can be challenging.15

STI EVALUATION

History and physical examination

A complete sexual history helps in estimating the patient’s risk of an STI and applying appropriate risk-based screening. Factors such as sexual practices, use of barrier protection, and history of STIs should be discussed.

Physical examination is also important. Although some patients may experience discomfort during a genital or pelvic examination, omitting this step may lead to missed diagnoses in women with STIs.16

Laboratory testing

Laboratory testing for STIs helps ensure accurate diagnosis and treatment. Empiric treatment without testing could give a patient a false sense of health by missing an infection that is not currently causing symptoms but that could later worsen or have lasting complications. Failure to test patients also misses the opportunity for partner notification, linkage to services, and follow-up testing.

Many of the most common STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis, can be detected using vaginal, cervical, or urethral swabs or first-catch urine (from the initial urine stream). In studies that compared various sampling methods,17 self-collected urine samples for gonorrhea in men were nearly as good as clinician-collected swabs of the urethra. In women, self-collected vaginal swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia were nearly as good as clinician-collected vaginal swabs. While urine specimens are acceptable for chlamydia testing in women, their sensitivity may be slightly lower than with vaginal and endocervical swab specimens.18,19

A major advantage of urine specimens for STI testing is that collection is noninvasive and is therefore more likely to be acceptable to patients. Urine testing can also be conducted in a variety of nonclinical settings such as health fairs, pharmacy-based screening programs, and express STI testing sites, thus increasing availability.

To prevent further transmission and morbidity and to aid in public health efforts, it is critical to recognize the cause of infectious cervicitis and urethritis and to screen for STIs according to guidelines.12 Table 1 summarizes current screening and laboratory testing recommendations.

GONORRHEA AND CHLAMYDIA

Gonorrhea and chlamydia are the 2 most frequently reported STIs in the United States, with more than 550,000 cases of gonorrhea and 1.7 million cases of chlamydia reported in 2017.4

Both infections present similarly: cervicitis or urethritis characterized by discharge (mucopurulent discharge with gonorrhea) and dysuria. Untreated, they can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammation, and infertility.

Extragenital infections can be asymptomatic or cause exudative pharyngitis or proctitis. Most people in whom chlamydia is detected from pharyngeal specimens are asymptomatic. When pharyngeal symptoms exist secondary to gonorrheal infection, they typically include sore throat and pharyngeal exudates. However, Komaroff et al,20 in a study of 192 men and women who presented with sore throat, found that only 2 (1%) tested positive for N gonorrhoeae.

Screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia

Best practices include screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia as follows21–23:

- Every year in sexually active women through age 25 (including during pregnancy) and in older women who have risk factors for infection12

- At least every year in men who have sex with men, at all sites of sexual contact (urethra, pharynx, rectum), along with testing for HIV and syphilis

- Every 3 to 6 months in men who have sex with men who have multiple or anonymous partners, who are sexually active and use illicit drugs, or who have partners who use illicit drugs

- Possibly every year in young men who live in high-prevalence areas or who are seen in certain clinical settings, such as STI and adolescent clinics.

Specimens. A vaginal swab is preferred for screening in women. Several studies have shown that self-collected swabs have clinical sensitivity and specificity comparable to that of provider-collected samples.17,24 First-catch urine or endocervical swabs have similar performance characteristics and are also acceptable. In men, urethral swabs or first-catch urine samples are appropriate for screening for urogenital infections.

Testing methods. Testing for both pathogens should be done simultaneously with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Commercially available NAATs are more sensitive than culture and antigen testing for detecting gonorrhea and chlamydia.25–27

Most assays are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for testing vaginal, urethral, cervical, and urine specimens. Until recently, no commercial assay was cleared for testing extragenital sites, but recommendations for screening extragenital sites prompted many clinical laboratories to validate throat and rectal swabs for use with NAATs, which are more sensitive than culture at these sites.25,28 The recent FDA approval of extragenital specimen types for 2 commercially available assays may increase the availability of testing for these sites.

Data on the utility of NAATs for detecting chlamydia and gonorrhea in children are limited, and many clinical laboratories have not validated molecular methods for testing in children. Current guidelines specific to this population should be followed regarding test methods and preferred specimen types.12,29,30

Although gonococcal infection is usually diagnosed with culture-independent molecular methods, antimicrobial resistance is emerging. Thus, failure of the combination of ceftriaxone and azithromycin should prompt culture-based follow-up testing to determine antimicrobial susceptibility.

Strategies for treatment and control

Historically, people treated for gonorrhea have been treated for chlamydia at the same time, as these diseases tend to go together. This can be with a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone for the gonorrhea plus a single oral dose of azithromycin for the chlamydia.12 For patients who have only gonorrhea, this double regimen may help prevent the development of resistant gonorrhea strains.

All the patient’s sexual partners in the previous 60 days should be tested and treated, and expedited partner therapy should be offered if possible. Patients should be advised to have no sexual contact until they complete the treatment, or 7 days after single-dose treatment. Testing should be repeated 3 months after treatment.

M GENITALIUM IS EMERGING

A member of the Mycoplasmataceae family, M genitalium was originally identified as a pathogen in the early 1980s but has only recently emerged as an important cause of STI. Studies indicate that it is responsible for 10% to 20% of cases of nongonococcal urethritis and 10% to 30% of cases of cervicitis.31–33 Additionally, 2% to 22% of cases of pelvic inflammatory disease have evidence of M genitalium.34,35

However, data on M genitalium prevalence are suspect because the organism is hard to identify—lacking a cell wall, it is undetectable by Gram stain.36 Although it has been isolated in respiratory and synovial fluids, it has so far been recognized to be clinically important only in the urogenital tract. It can persist for years in infected patients by exploiting specialized cell-surface structures to invade cells.36 Once inside a cell, it triggers secretion of mycoplasmal toxins and destructive metabolites such as hydrogen peroxide, evading the host immune system as it does so.37

Testing guidelines for M genitalium

Current guidelines do not recommend routine screening for M genitalium, and no commercial test was available until recently.12 Although evidence suggests that M genitalium is independently associated with preterm birth and miscarriages,38 routine screening of pregnant women is not recommended.12

Testing for M genitalium should be considered in cases of persistent or recurrent nongonococcal urethritis in patients who test negative for gonorrhea and chlamydia or for whom treatment has failed.12 Many isolates exhibit genotypic resistance to macrolide antibiotics, which are often the first-line therapy for nongonococcal urethritis.39

Further study is needed to evaluate the potential impact of routine screening for M genitalium on the reproductive and sexual health of at-risk populations.

Diagnostic tests for M genitalium

Awareness of M genitalium as a cause of nongonococcal urethritis has been hampered by a dearth of diagnostic tests.40 The organism’s fastidious requirements and extremely slow growth preclude culture as a practical method of diagnosis.41 Serologic assays are dogged by cross-reactivity and poor sensitivity.42,43 Thus, molecular assays for detecting M genitalium and associated resistance markers are preferred for diagnosis.12

Several molecular tests are approved, available, and in use in Europe for diagnosing M genitalium infection,40 and in January 2019 the FDA approved a molecular test that can detect M genitalium in urine specimens and vaginal, endocervical, urethral, and penile meatal swabs. Although vaginal swabs are preferred for this assay because they have higher sensitivity (92% for provider-collected and 99% for patient-collected swabs), urine specimens are acceptable, with a sensitivity of 78%.44

At least 1 company is seeking FDA clearance for another molecular diagnostic assay for detecting M genitalium and markers of macrolide resistance in urine and genital swab specimens. Such assays may facilitate appropriate treatment.

Clinicians should stay abreast of diagnostic testing options, which are likely to become more readily available soon.

A high rate of macrolide resistance

Because M genitalium lacks a cell wall, antibiotics such as beta-lactams that target cell wall synthesis are ineffective.

Regimens for treating M genitalium are outlined in Table 2.12 Azithromycin is more effective than doxycycline. However, as many as 50% of strains were macrolide-resistant in a cohort of US female patients.45 Given the high incidence of treatment failure with azithromycin 1 g, it is thought that this regimen might select for resistance. For cases in which symptoms persist, a 1- to 2-week course of moxifloxacin is recommended.12 However, this has not been validated by clinical trials, and failures of the 7-day regimen have been reported.46

Partners of patients who test positive for M genitalium should also be tested and undergo clinically applicable screening for nongonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.12

TRICHOMONIASIS

Trichomoniasis, caused by the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis, is the most prevalent nonviral STI in the United States. It disproportionately affects black women, in whom the prevalence is 13%, compared with 1% in non-Hispanic white women.47 It is also present in 26% of women with symptoms who are seen in STI clinics and is highly prevalent in incarcerated populations. It is uncommon in men who have sex with men.48

In men, trichomoniasis manifests as urethritis, epididymitis, or prostatitis. While most infected women have no symptoms, they may experience vaginitis with discharge that is diffuse, frothy, pruritic, malodorous, or yellow-green. Vaginal and cervical erythema (“strawberry cervix”) can also occur.

Screening for trichomoniasis

Current guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend testing for T vaginalis in women who have symptoms and routinely screening in women who are HIV-positive, regardless of symptoms. There is no evidence to support routine screening of pregnant women without symptoms, and pregnant women who do have symptoms should be evaluated according to the same guidelines as for nonpregnant women.12 Testing can be considered in patients who have no symptoms but who engage in high-risk behaviors and in areas of high prevalence.

A lack of studies using sensitive methods for T vaginalis detection has hampered a true estimation of disease burden and at-risk populations. Screening recommendations may evolve in upcoming clinical guidelines as the field advances.

As infection can recur, women should be retested 3 months after initial diagnosis.12

NAAT is the preferred test for trichomoniasis

Commercially available diagnostic tests for trichomoniasis include culture, antigen testing, and NAAT.49 While many clinicians do their own wet-mount microscopy for a rapid result, this method has low sensitivity.50 Similarly, antigen testing and culture perform poorly compared with NAATs, which are the gold standard for detection.51,52 A major advantage of NAATs for T vaginalis detection is that they combine high sensitivity and fast results, facilitating diagnosis and appropriate treatment of patients and their partners.

In spite of these benefits, adoption of molecular diagnostic testing for T vaginalis has lagged behind that for chlamydia and gonorrhea.53 FDA-cleared NAATs are available for testing vaginal, cervical, or urine specimens from women, but until recently, there were no approved assays for testing in men. The Cepheid Xpert TV assay, which is valid for male urine specimens to diagnose other sexually transmitted diseases, has demonstrated excellent diagnostic sensitivity for T vaginalis in men and women.54 Interestingly, a large proportion of male patients in this study had no symptoms, suggesting that screening of men in high-risk groups may be warranted.

7-day metronidazole treatment beats single-dose treatment

The first-line treatment for trichomoniasis has been a single dose of metronidazole 2 g by mouth, but in a recent randomized controlled trial,55 a course of 500 mg by mouth twice a day for 7 days was 45% more effective at 4 weeks than a single dose, and it should now be the preferred regimen.

In clinical trials,56 a single dose of tinidazole 2 g orally was equivalent or superior to metronidazole 2 g and had fewer gastrointestinal side effects, but it is more expensive.

- Harding-Esch EM, Nori AV, Hegazi A, et al. Impact of deploying multiple point-of-care tests with a ‘sample first’ approach on a sexual health clinical care pathway. A service evaluation. Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93(6):424–429. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2016-052988

- Unemo M, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17(8):e235–e279. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30310-9

- Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 2015; 10(12):e0143304. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143304

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2017. www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/toc.htm. Accessed October 7, 2019.

- Ginocchio CC, Chapin K, Smith JS, et al. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis and coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States as determined by the Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50(8):2601–2608. doi:10.1128/JCM.00748-12

- Newton-Levinson A, Leichliter JS, Chandra-Mouli V. Sexually transmitted infection services for adolescents and youth in low- and middle-income countries: perceived and experienced barriers to accessing care. J Adolesc Health 2016; 59(1):7–16.

doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.014 - Barbee LA, Khosropour CM, Dombrowksi JC, Golden MR. New human immunodeficiency virus diagnosis independently associated with rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44(7):385–389. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000614

- Halkitis PN, Kapadia F, Bub KL, Barton S, Moreira AD, Stults CB. A longitudinal investigation of syndemic conditions among young gay, bisexual, and other MSM: the P18 cohort study. AIDS Behav 2015; 19(6):970–980. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0892-y

- Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Prev Med 2003; 36(4):502–509. pmid:12649059

- Patel P, Bush T, Mayer K, et al; SUN Study Investigators. Routine brief risk-reduction counseling with biannual STD testing reduces STD incidence among HIV-infected men who have sex with men in care. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39(6):470–474. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31824b3110

- Tomas ME, Getman D, Donskey CJ, Hecker MT. Overdiagnosis of urinary tract infection and underdiagnosis of sexually transmitted infection in adult women presenting to an emergency department. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53(8):2686–2692. doi:10.1128/JCM.00670-15

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64(RR–03): 1–137. pmid:26042815

- van Aar F, van Weert Y, Spijker R, Gotz H, Op de Coul E; Partner Notification Group. Partner notification among men who have sex with men and heterosexuals with STI/HIV: different outcomes and challenges. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26(8):565–573. doi:10.1177/0956462414547398

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDa): expedited partner therapy. www.cdc.gov/std/ept/. Accessed October 7, 2019.

- Jamison CD, Chang T, Mmeje O. Expedited partner therapy: combating record high sexually transmitted infection rates. Am J Public Health 2018; 108(10):1325–1327. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304570

- Singh RH, Zenilman JM, Brown KM, Madden T, Gaydos C, Ghanem KG. The role of physical examination in diagnosing common causes of vaginitis: a prospective study. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89(3):185–190. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2012-050550

- Lunny C, Taylor D, Hoang L, et al. Self-collected versus clinician-collected sampling for chlamydia and gonorrhea screening: a systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10(7):e0132776. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132776

- Michel CE, Sonnex C, Carne CA, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis load at matched anatomic sites: implications for screening strategies. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45(5):1395–1402. doi:10.1128/JCM.00100-07

- Schachter J, Chernesky MA, Willis DE, et al. Vaginal swabs are the specimens of choice when screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: results from a multicenter evaluation of the APTIMA assays for both infections. Sex Transm Dis 2005; 32(12):725–728. pmid:16314767

- Komaroff AL, Aronson MD, Pass TM, Ervin CT. Prevalence of pharyngeal gonorrhea in general medical patients with sore throats. Sex Transm Dis 1980; 7(3):116–119. pmid:6777884

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinic-based testing for rectal and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections by community-based organizations—five cities, United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58(26):716–719. pmid:19590491

- Chesson HW, Bernstein KT, Gift TL, Marcus JL, Pipkin S, Kent CK. The cost-effectiveness of screening men who have sex with men for rectal chlamydial and gonococcal infection to prevent HIV Infection. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40(5):366–471. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318284e544

- Park J, Marcus JL, Pandori M, Snell A, Philip SS, Bernstein KT. Sentinel surveillance for pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea among men who have sex with men—San Francisco, 2010. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39(6):482–484. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182495e2f

- Masek BJ, Arora N, Quinn N, et al. Performance of three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by use of self-collected vaginal swabs obtained via an internet-based screening program. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47(6):1663–1667. doi:10.1128/JCM.02387-08

- Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis rectal infections. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48(5):1827–1832. doi:10.1128/JCM.02398-09

- Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Reisner SL, et al. Asymptomatic gonorrhea and chlamydial infections detected by nucleic acid amplification tests among Boston area men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35(5):495–498. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816471ae

- Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, Shayevich C, Klausner JD. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35(7):637–642. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31817bdd7e

- Cornelisse VJ, Chow EP, Huffam S, et al. Increased detection of pharyngeal and rectal gonorrhea in men who have sex with men after transition from culture to nucleic acid amplification testing. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44(2):114–117. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000553

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae—2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014; 63(RR–02):1–19. pmid:24622331

- Hammerschlag MR, Gaydos CA. Guidelines for the use of molecular biological methods to detect sexually transmitted pathogens in cases of suspected sexual abuse in children. Methods Mol Biol 2012; 903:307–317. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-937-2_21

- Huppert JS, Mortensen JE, Reed JL, Kahn JA, Rich KD, Hobbs MM. Mycoplasma genitalium detected by transcription-mediated amplification is associated with Chlamydia trachomatis in adolescent women. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35(3):250–254. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815abac6

- Pond MJ, Nori AV, Witney AA, Lopeman RC, Butcher PD, Sadiq ST. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in nongonococcal urethritis: the need for routine testing and the inadequacy of current treatment options. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(5):631–637. doi:10.1093/cid/cit752

- Seña AC, Lee JY, Schwebke J, et al. A silent epidemic: the prevalence, incidence and persistence of Mycoplasma genitalium among young, asymptomatic high-risk women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(1):73–79. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy025

- Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG 2010; 117(3):361–364. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02455.x

- Cohen CR, Manhart LE, Bukusi EA, et al. Association between Mycoplasma genitalium and acute endometritis. Lancet 2002; 359(9308):765–766. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07848-0

- Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24(3):498–514. doi:10.1128/CMR.00006-11

- Ross JD, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium as a sexually transmitted infection: implications for screening, testing, and treatment. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82(4):269–271. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.017368

- Donders GG, Ruban K, Bellen G, Petricevic L. Mycoplasma/ureaplasma infection in pregnancy: to screen or not to screen. J Perinat Med 2017; 45(5):505–515. doi:10.1515/jpm-2016-0111

- Allan-Blitz LT, Mokany E, Miller S, Wee R, Shannon C, Klausner JD. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium and azithromycin-resistant infections among remnant clinical specimens, Los Angeles. Sex Transm Dis 2018; 45(9):632–635. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000829

- Munson E. Molecular diagnostics update for the emerging (if not already widespread) sexually transmitted infection agent Mycoplasma genitalium: just about ready for prime time. J Clin Microbio. 2017; 55(10):2894–2902. doi:10.1128/JCM.00818-17

- Waites KB, Taylor-Robinson D. Mycoplasma and ureaplasma. In: Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC, American Society for Microbiology, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 11th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2015:1088–1105.

- Cimolai N, Bryan LE, To M, Woods DE. Immunological cross-reactivity of a Mycoplasma pneumoniae membrane-associated protein antigen with Mycoplasma genitalium and Acholeplasma laidlawii. J Clin Microbiol 1987; 25(11):2136–2139. pmid:2447119

- Ma L, Mancuso M, Williams JA, et al. Extensive variation and rapid shift of the MG192 sequence in Mycoplasma genitalium strains from patients with chronic infection. Infect Immun 2014; 82(3):1326–1334. doi:10.1128/IAI.01526-13