User login

Guidelines Aren’t For Everybody

An 88-year-old man comes for clinic follow up. He has a medical history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and chronic kidney disease. He recently had laboratory tests done: BUN, 32 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.3 mg/dL; potassium, 4.5 mmol/L; bicarbonate, 22 Eq/L; and A1c, 8.2%.

He checks his blood glucose daily (alternating between fasting blood glucose and before dinner) and his fasting blood glucose levels are around 130 mg/dL. His highest glucose reading was 240 mg/dL. He does not have polyuria or visual changes. Current medications: atorvastatin, irbesartan, empagliflozin, and amlodipine. On physical exam his blood pressure is 130/70 mm Hg, pulse is 80, and his BMI 20.

What medication adjustments would you recommend?

A. Begin insulin glargine at bedtime

B. Begin mealtime insulin aspart

C. Begin semaglutide

D. Begin metformin

E. No changes

I think the correct approach here would be no changes. Most physicians know guideline recommendations for A1c of less than 7% are used for patients with diabetes with few comorbid conditions, normal cognition, and functional status. Many of our elderly patients do not meet these criteria and the goal of intense medical treatment of diabetes is different in those patients. The American Diabetes Association has issued a thoughtful paper on treatment of diabetes in elderly people, stressing that patients should have very individualized goals, and that there is no one-size-fits all A1c goal.1

In this patient I would avoid adding insulin, given hypoglycemia risk. A GLP-1 agonist might appear attractive given his multiple cardiovascular risk factors, but his low BMI is a major concern for frailty that may well be worsened with reduced nutrient intake. Diabetes is the chronic condition that probably has the most guidance for management in elderly patients.

I recently saw a 92-year-old man with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation who had been losing weight and becoming weaker. He had suffered several falls in the previous 2 weeks. His medication list included amiodarone, apixaban, sacubitril/valsartan, carvedilol, empagliflozin, spironolactone, and furosemide. He was extremely frail and had stopped eating. He was receiving all guideline-directed therapies, yet he was miserable and dying. Falls in this population are potentially as fatal as decompensated heart disease.

I stopped his amiodarone, furosemide, and spironolactone, and reduced his doses of sacubitril/valsartan and carvedilol. His appetite returned and his will to live returned. Heart failure guidelines do not include robust studies of very elderly patients because few studies exist in this population. Frailty assessment is crucial in decision making in your elderly patients.2,3 and frequent check-ins to make sure that they are not suffering from the effects of polypharmacy are crucial. Our goal in our very elderly patients is quality life-years. Polypharmacy has the potential to decrease the quality of life, as well as potentially shorten life.

The very elderly are at risk of the negative consequences of polypharmacy, especially if they have several diseases like diabetes, congestive heart failure, and hypertension that may require multiple medications. Gutierrez-Valencia and colleagues performed a systematic review of 25 articles on frailty and polypharmacy.4 Their findings demonstrated a significant association between an increased number of medications and frailty. They postulated that polypharmacy could actually be a contributor to frailty. There just isn’t enough evidence for the benefit of guidelines in the very aged and the risks of polypharmacy are real. We should use the lowest possible doses of medications in this population, frequently reassess goals, and monitor closely for side effects.

Pearl: Always consider the risks of polypharmacy when considering therapies for your elderly patients.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2021. Diabetes Care 2021;44(Suppl 1):S168–S179.

2. Gaur A et al. Cardiogeriatrics: The current state of the art. Heart. 2024 Jan 11:heartjnl-2022-322117.

3. Denfeld QE et al. Assessing and managing frailty in advanced heart failure: An International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Nov 29:S1053-2498(23)02028-4.

4. Gutiérrez-Valencia M et al. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Jul;84(7):1432-44.

An 88-year-old man comes for clinic follow up. He has a medical history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and chronic kidney disease. He recently had laboratory tests done: BUN, 32 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.3 mg/dL; potassium, 4.5 mmol/L; bicarbonate, 22 Eq/L; and A1c, 8.2%.

He checks his blood glucose daily (alternating between fasting blood glucose and before dinner) and his fasting blood glucose levels are around 130 mg/dL. His highest glucose reading was 240 mg/dL. He does not have polyuria or visual changes. Current medications: atorvastatin, irbesartan, empagliflozin, and amlodipine. On physical exam his blood pressure is 130/70 mm Hg, pulse is 80, and his BMI 20.

What medication adjustments would you recommend?

A. Begin insulin glargine at bedtime

B. Begin mealtime insulin aspart

C. Begin semaglutide

D. Begin metformin

E. No changes

I think the correct approach here would be no changes. Most physicians know guideline recommendations for A1c of less than 7% are used for patients with diabetes with few comorbid conditions, normal cognition, and functional status. Many of our elderly patients do not meet these criteria and the goal of intense medical treatment of diabetes is different in those patients. The American Diabetes Association has issued a thoughtful paper on treatment of diabetes in elderly people, stressing that patients should have very individualized goals, and that there is no one-size-fits all A1c goal.1

In this patient I would avoid adding insulin, given hypoglycemia risk. A GLP-1 agonist might appear attractive given his multiple cardiovascular risk factors, but his low BMI is a major concern for frailty that may well be worsened with reduced nutrient intake. Diabetes is the chronic condition that probably has the most guidance for management in elderly patients.

I recently saw a 92-year-old man with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation who had been losing weight and becoming weaker. He had suffered several falls in the previous 2 weeks. His medication list included amiodarone, apixaban, sacubitril/valsartan, carvedilol, empagliflozin, spironolactone, and furosemide. He was extremely frail and had stopped eating. He was receiving all guideline-directed therapies, yet he was miserable and dying. Falls in this population are potentially as fatal as decompensated heart disease.

I stopped his amiodarone, furosemide, and spironolactone, and reduced his doses of sacubitril/valsartan and carvedilol. His appetite returned and his will to live returned. Heart failure guidelines do not include robust studies of very elderly patients because few studies exist in this population. Frailty assessment is crucial in decision making in your elderly patients.2,3 and frequent check-ins to make sure that they are not suffering from the effects of polypharmacy are crucial. Our goal in our very elderly patients is quality life-years. Polypharmacy has the potential to decrease the quality of life, as well as potentially shorten life.

The very elderly are at risk of the negative consequences of polypharmacy, especially if they have several diseases like diabetes, congestive heart failure, and hypertension that may require multiple medications. Gutierrez-Valencia and colleagues performed a systematic review of 25 articles on frailty and polypharmacy.4 Their findings demonstrated a significant association between an increased number of medications and frailty. They postulated that polypharmacy could actually be a contributor to frailty. There just isn’t enough evidence for the benefit of guidelines in the very aged and the risks of polypharmacy are real. We should use the lowest possible doses of medications in this population, frequently reassess goals, and monitor closely for side effects.

Pearl: Always consider the risks of polypharmacy when considering therapies for your elderly patients.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2021. Diabetes Care 2021;44(Suppl 1):S168–S179.

2. Gaur A et al. Cardiogeriatrics: The current state of the art. Heart. 2024 Jan 11:heartjnl-2022-322117.

3. Denfeld QE et al. Assessing and managing frailty in advanced heart failure: An International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Nov 29:S1053-2498(23)02028-4.

4. Gutiérrez-Valencia M et al. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Jul;84(7):1432-44.

An 88-year-old man comes for clinic follow up. He has a medical history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and chronic kidney disease. He recently had laboratory tests done: BUN, 32 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.3 mg/dL; potassium, 4.5 mmol/L; bicarbonate, 22 Eq/L; and A1c, 8.2%.

He checks his blood glucose daily (alternating between fasting blood glucose and before dinner) and his fasting blood glucose levels are around 130 mg/dL. His highest glucose reading was 240 mg/dL. He does not have polyuria or visual changes. Current medications: atorvastatin, irbesartan, empagliflozin, and amlodipine. On physical exam his blood pressure is 130/70 mm Hg, pulse is 80, and his BMI 20.

What medication adjustments would you recommend?

A. Begin insulin glargine at bedtime

B. Begin mealtime insulin aspart

C. Begin semaglutide

D. Begin metformin

E. No changes

I think the correct approach here would be no changes. Most physicians know guideline recommendations for A1c of less than 7% are used for patients with diabetes with few comorbid conditions, normal cognition, and functional status. Many of our elderly patients do not meet these criteria and the goal of intense medical treatment of diabetes is different in those patients. The American Diabetes Association has issued a thoughtful paper on treatment of diabetes in elderly people, stressing that patients should have very individualized goals, and that there is no one-size-fits all A1c goal.1

In this patient I would avoid adding insulin, given hypoglycemia risk. A GLP-1 agonist might appear attractive given his multiple cardiovascular risk factors, but his low BMI is a major concern for frailty that may well be worsened with reduced nutrient intake. Diabetes is the chronic condition that probably has the most guidance for management in elderly patients.

I recently saw a 92-year-old man with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation who had been losing weight and becoming weaker. He had suffered several falls in the previous 2 weeks. His medication list included amiodarone, apixaban, sacubitril/valsartan, carvedilol, empagliflozin, spironolactone, and furosemide. He was extremely frail and had stopped eating. He was receiving all guideline-directed therapies, yet he was miserable and dying. Falls in this population are potentially as fatal as decompensated heart disease.

I stopped his amiodarone, furosemide, and spironolactone, and reduced his doses of sacubitril/valsartan and carvedilol. His appetite returned and his will to live returned. Heart failure guidelines do not include robust studies of very elderly patients because few studies exist in this population. Frailty assessment is crucial in decision making in your elderly patients.2,3 and frequent check-ins to make sure that they are not suffering from the effects of polypharmacy are crucial. Our goal in our very elderly patients is quality life-years. Polypharmacy has the potential to decrease the quality of life, as well as potentially shorten life.

The very elderly are at risk of the negative consequences of polypharmacy, especially if they have several diseases like diabetes, congestive heart failure, and hypertension that may require multiple medications. Gutierrez-Valencia and colleagues performed a systematic review of 25 articles on frailty and polypharmacy.4 Their findings demonstrated a significant association between an increased number of medications and frailty. They postulated that polypharmacy could actually be a contributor to frailty. There just isn’t enough evidence for the benefit of guidelines in the very aged and the risks of polypharmacy are real. We should use the lowest possible doses of medications in this population, frequently reassess goals, and monitor closely for side effects.

Pearl: Always consider the risks of polypharmacy when considering therapies for your elderly patients.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2021. Diabetes Care 2021;44(Suppl 1):S168–S179.

2. Gaur A et al. Cardiogeriatrics: The current state of the art. Heart. 2024 Jan 11:heartjnl-2022-322117.

3. Denfeld QE et al. Assessing and managing frailty in advanced heart failure: An International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Nov 29:S1053-2498(23)02028-4.

4. Gutiérrez-Valencia M et al. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Jul;84(7):1432-44.

Reducing or Discontinuing Insulin or Sulfonylurea When Initiating a Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Agonist

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

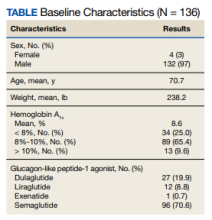

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

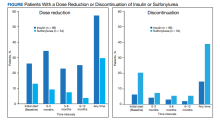

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14

This retrospective chart review found a large proportion of patients had a dose reduction of insulin (57.3%) or sulfonylurea (29.6%). The percentage of patients with a dose reduction was potentially underestimated as patients were not counted if they discontinued insulin or sulfonylurea. Concomitant use of GLP-1 agonists with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 The dose reductions in this study show that pharmacists within pharmacy-led PACT clinics monitor for or attempt to prevent hypoglycemia, which aligns with the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists. While increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option for patients, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in an older population, like this one with a mean age > 70 years. The large proportions of patients with dose reductions or insulin and sulfonylurea discontinuations suggest that pharmacists may need to take a more cautious approach when initiating a GLP-1 agonist to prevent adverse health outcomes related to low blood sugar for older adults, such as falls and fractures.

Insulin was discontinued in 20.4% of patients and sulfonylurea was discontinued in 38.9% of patients within 12 months after starting a GLP-1 agonist. When a patient was on both insulin and a sulfonylurea, the percentage of patients who discontinued insulin (21.4%) or a sulfonylurea (50.0%) was higher compared with patients just on insulin (14.6%) or a sulfonylurea (38.9%) alone. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to a higher incidence of discontinuations when these diabetes agents are administered in combination.

Within 12 months of patients receiving a GLP-1 agonist, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.1%, which is comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. For semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.9 For dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 0.7% to 1.6% and 0.8% to 1.6%, respectively.10 For liraglutide 1.8 mg dosage, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 1.0% to 1.5%.11 The mean weight loss in this study was 13.9 lb. Along with HbA1c, weight loss in this review was comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. Patients administering semaglutide lost up to 14 lb, patients taking dulaglutide lost up to 10.1 lb, and patients on liraglutide lost on average 6.2 lb.9-11 Even with medications such as insulin and sulfonylurea that have the side effects of hypoglycemia and weight gain, adding a GLP-1 agonist showed a reduction in HbA1c and weight loss relatively similar to previous clinical trials.

A study on the effects of adding semaglutide to insulin regimens in March 2023 by Meyer and colleagues displayed similar results to this retrospective chart review. That study concluded that there was blood glucose improvement (HbA1c reduction of 1.3%) in patients after 6 months despite a decrease in the insulin dose. Also, patients lost a mean weight of 11 lb during the 6-month trial.3 This retrospective chart review at the WBVAMC adds to the body of research that supports potential reductions or discontinuations of insulin and/or sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the results. This review was comprised of a mostly older, male population, which results in a low generalizability to organizations other than VA medical centers. In addition, this study only evaluated patients on a GLP-1 agonist followed in a pharmacist-led PACT clinic. This study excluded patients who were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by an endocrinologist or a pharmacist at one of the community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with WBVAMC, or a pharmacist or clinician outside the VA. The sole focus of this study was patients in a pharmacist-led VAMC clinic. Not all patient data may have been included in the study. If a patient did not have an appointment at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months or did not obtain laboratory tests, HbA1c and weights were not recorded. Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and in-person appointments were potentially switched to phone or video appointments. There were many instances during this chart review where a weight was not recorded at each time interval. Also, this study did not consider any other diabetes medications the patient was taking. There were many instances where the patient was taking metformin and/or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. These medications along with diet could have affected the weight results as metformin is weight neutral and SGLT-2 inhibitors promote weight loss.15 Lastly, this study did not evaluate the amount of insulin reduced, only if there was a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea.

Conclusions

Dose reductions and a discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist may be needed. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to the higher incidences of discontinuations compared with patients on just 1 of these agents. Dose reductions or discontinuations of these diabetic agents can promote positive patient outcomes, such as preventing hypoglycemia, minimizing weight gain, increasing weight loss, and reducing HbA1c levels.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

2. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VE, et al. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S216-S229. doi:10.2337/dc23-S013

3. Meyer J, Dreischmeier E, Lehmann M, Phelan J. The effects of adding semaglutide to high daily dose insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(3):241-250. doi:10.1177/10600280221107381

4. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2291-2301. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00070

5. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152-160. doi:10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152

6. Castek SL, Healey LC, Kania DS, Vernon VP, Dawson AJ. Assessment of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in veterans taking basal/bolus insulin regimens. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S18-S23. doi:10.12788/fp.0317

7. Chen M, Vider E, Plakogiannis R. Insulin dosage adjustments after initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):511-517. doi:10.1177/0897190021993625

8. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A; EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

9. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection. Package insert. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf

11. Victoza (liraglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf

12. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(9):1117-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037

13. Granata A, Maccarrone R, Anzaldi M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and renal outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic kidney disease: state of the art. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(9):1657-1665. Published 2022 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac069

14. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595

15. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14

This retrospective chart review found a large proportion of patients had a dose reduction of insulin (57.3%) or sulfonylurea (29.6%). The percentage of patients with a dose reduction was potentially underestimated as patients were not counted if they discontinued insulin or sulfonylurea. Concomitant use of GLP-1 agonists with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 The dose reductions in this study show that pharmacists within pharmacy-led PACT clinics monitor for or attempt to prevent hypoglycemia, which aligns with the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists. While increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option for patients, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in an older population, like this one with a mean age > 70 years. The large proportions of patients with dose reductions or insulin and sulfonylurea discontinuations suggest that pharmacists may need to take a more cautious approach when initiating a GLP-1 agonist to prevent adverse health outcomes related to low blood sugar for older adults, such as falls and fractures.

Insulin was discontinued in 20.4% of patients and sulfonylurea was discontinued in 38.9% of patients within 12 months after starting a GLP-1 agonist. When a patient was on both insulin and a sulfonylurea, the percentage of patients who discontinued insulin (21.4%) or a sulfonylurea (50.0%) was higher compared with patients just on insulin (14.6%) or a sulfonylurea (38.9%) alone. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to a higher incidence of discontinuations when these diabetes agents are administered in combination.

Within 12 months of patients receiving a GLP-1 agonist, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.1%, which is comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. For semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.9 For dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 0.7% to 1.6% and 0.8% to 1.6%, respectively.10 For liraglutide 1.8 mg dosage, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 1.0% to 1.5%.11 The mean weight loss in this study was 13.9 lb. Along with HbA1c, weight loss in this review was comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. Patients administering semaglutide lost up to 14 lb, patients taking dulaglutide lost up to 10.1 lb, and patients on liraglutide lost on average 6.2 lb.9-11 Even with medications such as insulin and sulfonylurea that have the side effects of hypoglycemia and weight gain, adding a GLP-1 agonist showed a reduction in HbA1c and weight loss relatively similar to previous clinical trials.

A study on the effects of adding semaglutide to insulin regimens in March 2023 by Meyer and colleagues displayed similar results to this retrospective chart review. That study concluded that there was blood glucose improvement (HbA1c reduction of 1.3%) in patients after 6 months despite a decrease in the insulin dose. Also, patients lost a mean weight of 11 lb during the 6-month trial.3 This retrospective chart review at the WBVAMC adds to the body of research that supports potential reductions or discontinuations of insulin and/or sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the results. This review was comprised of a mostly older, male population, which results in a low generalizability to organizations other than VA medical centers. In addition, this study only evaluated patients on a GLP-1 agonist followed in a pharmacist-led PACT clinic. This study excluded patients who were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by an endocrinologist or a pharmacist at one of the community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with WBVAMC, or a pharmacist or clinician outside the VA. The sole focus of this study was patients in a pharmacist-led VAMC clinic. Not all patient data may have been included in the study. If a patient did not have an appointment at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months or did not obtain laboratory tests, HbA1c and weights were not recorded. Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and in-person appointments were potentially switched to phone or video appointments. There were many instances during this chart review where a weight was not recorded at each time interval. Also, this study did not consider any other diabetes medications the patient was taking. There were many instances where the patient was taking metformin and/or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. These medications along with diet could have affected the weight results as metformin is weight neutral and SGLT-2 inhibitors promote weight loss.15 Lastly, this study did not evaluate the amount of insulin reduced, only if there was a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea.

Conclusions

Dose reductions and a discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist may be needed. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to the higher incidences of discontinuations compared with patients on just 1 of these agents. Dose reductions or discontinuations of these diabetic agents can promote positive patient outcomes, such as preventing hypoglycemia, minimizing weight gain, increasing weight loss, and reducing HbA1c levels.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14

This retrospective chart review found a large proportion of patients had a dose reduction of insulin (57.3%) or sulfonylurea (29.6%). The percentage of patients with a dose reduction was potentially underestimated as patients were not counted if they discontinued insulin or sulfonylurea. Concomitant use of GLP-1 agonists with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 The dose reductions in this study show that pharmacists within pharmacy-led PACT clinics monitor for or attempt to prevent hypoglycemia, which aligns with the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists. While increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option for patients, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in an older population, like this one with a mean age > 70 years. The large proportions of patients with dose reductions or insulin and sulfonylurea discontinuations suggest that pharmacists may need to take a more cautious approach when initiating a GLP-1 agonist to prevent adverse health outcomes related to low blood sugar for older adults, such as falls and fractures.

Insulin was discontinued in 20.4% of patients and sulfonylurea was discontinued in 38.9% of patients within 12 months after starting a GLP-1 agonist. When a patient was on both insulin and a sulfonylurea, the percentage of patients who discontinued insulin (21.4%) or a sulfonylurea (50.0%) was higher compared with patients just on insulin (14.6%) or a sulfonylurea (38.9%) alone. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to a higher incidence of discontinuations when these diabetes agents are administered in combination.

Within 12 months of patients receiving a GLP-1 agonist, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.1%, which is comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. For semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.9 For dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 0.7% to 1.6% and 0.8% to 1.6%, respectively.10 For liraglutide 1.8 mg dosage, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 1.0% to 1.5%.11 The mean weight loss in this study was 13.9 lb. Along with HbA1c, weight loss in this review was comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. Patients administering semaglutide lost up to 14 lb, patients taking dulaglutide lost up to 10.1 lb, and patients on liraglutide lost on average 6.2 lb.9-11 Even with medications such as insulin and sulfonylurea that have the side effects of hypoglycemia and weight gain, adding a GLP-1 agonist showed a reduction in HbA1c and weight loss relatively similar to previous clinical trials.

A study on the effects of adding semaglutide to insulin regimens in March 2023 by Meyer and colleagues displayed similar results to this retrospective chart review. That study concluded that there was blood glucose improvement (HbA1c reduction of 1.3%) in patients after 6 months despite a decrease in the insulin dose. Also, patients lost a mean weight of 11 lb during the 6-month trial.3 This retrospective chart review at the WBVAMC adds to the body of research that supports potential reductions or discontinuations of insulin and/or sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the results. This review was comprised of a mostly older, male population, which results in a low generalizability to organizations other than VA medical centers. In addition, this study only evaluated patients on a GLP-1 agonist followed in a pharmacist-led PACT clinic. This study excluded patients who were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by an endocrinologist or a pharmacist at one of the community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with WBVAMC, or a pharmacist or clinician outside the VA. The sole focus of this study was patients in a pharmacist-led VAMC clinic. Not all patient data may have been included in the study. If a patient did not have an appointment at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months or did not obtain laboratory tests, HbA1c and weights were not recorded. Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and in-person appointments were potentially switched to phone or video appointments. There were many instances during this chart review where a weight was not recorded at each time interval. Also, this study did not consider any other diabetes medications the patient was taking. There were many instances where the patient was taking metformin and/or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. These medications along with diet could have affected the weight results as metformin is weight neutral and SGLT-2 inhibitors promote weight loss.15 Lastly, this study did not evaluate the amount of insulin reduced, only if there was a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea.

Conclusions

Dose reductions and a discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist may be needed. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to the higher incidences of discontinuations compared with patients on just 1 of these agents. Dose reductions or discontinuations of these diabetic agents can promote positive patient outcomes, such as preventing hypoglycemia, minimizing weight gain, increasing weight loss, and reducing HbA1c levels.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

2. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VE, et al. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S216-S229. doi:10.2337/dc23-S013

3. Meyer J, Dreischmeier E, Lehmann M, Phelan J. The effects of adding semaglutide to high daily dose insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(3):241-250. doi:10.1177/10600280221107381

4. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2291-2301. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00070

5. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152-160. doi:10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152

6. Castek SL, Healey LC, Kania DS, Vernon VP, Dawson AJ. Assessment of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in veterans taking basal/bolus insulin regimens. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S18-S23. doi:10.12788/fp.0317

7. Chen M, Vider E, Plakogiannis R. Insulin dosage adjustments after initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):511-517. doi:10.1177/0897190021993625

8. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A; EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

9. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection. Package insert. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf

11. Victoza (liraglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf

12. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(9):1117-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037

13. Granata A, Maccarrone R, Anzaldi M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and renal outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic kidney disease: state of the art. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(9):1657-1665. Published 2022 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac069

14. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595

15. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

2. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VE, et al. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S216-S229. doi:10.2337/dc23-S013

3. Meyer J, Dreischmeier E, Lehmann M, Phelan J. The effects of adding semaglutide to high daily dose insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(3):241-250. doi:10.1177/10600280221107381

4. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2291-2301. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00070

5. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152-160. doi:10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152

6. Castek SL, Healey LC, Kania DS, Vernon VP, Dawson AJ. Assessment of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in veterans taking basal/bolus insulin regimens. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S18-S23. doi:10.12788/fp.0317

7. Chen M, Vider E, Plakogiannis R. Insulin dosage adjustments after initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):511-517. doi:10.1177/0897190021993625

8. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A; EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

9. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection. Package insert. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf

11. Victoza (liraglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf

12. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(9):1117-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037

13. Granata A, Maccarrone R, Anzaldi M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and renal outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic kidney disease: state of the art. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(9):1657-1665. Published 2022 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac069

14. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595

15. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2

Top 5 Medications That Can Increase Blood Glucose Levels

It’s that time of the year, when social media is rife with many top 5 and top 10 lists. Let’s revisit some of the most commonly used medications known to increase glucose levels and look at some practical tips on overcoming these.

1. Glucocorticoids

Without a doubt, corticosteroids are at the top of the list when it comes to the potential for increasing blood glucose levels. High-dose glucocorticoid therapy is known to lead to new-onset diabetes (steroid-induced diabetes). Similarly, people with preexisting diabetes may notice significant worsening of glycemic control when they start on glucocorticoid therapy. The extent of glucose elevation depends on their glycemic status prior to initiation on steroids, the dose and duration of glucocorticoid therapy, and comorbid conditions, among other factors.

Management tip: For those with previously well-controlled diabetes or borderline diabetes, glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia may be managed by metformin with or without sulfonylurea therapy, especially if corticosteroid treatment is low-dose and for a shorter duration. However, for many individuals with preexisting poorly controlled diabetes or those initiated on high-dose corticosteroids, insulin therapy would perhaps be the treatment of choice. Glucocorticoid therapy generally leads to more pronounced postprandial hyperglycemia compared with fasting hyperglycemia; hence, the use of short-acting insulin therapy or perhaps NPH insulin in the morning might be a better option for many individuals. Dietary modification plays an important role in limiting the extent of postprandial hyperglycemia. Use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices may also be very helpful for understanding glycemic excursions and how to adjust insulin. In individuals for whom glucocorticoid therapy is tapered down, it is important to adjust the dose of medications with potential to cause hypoglycemia, such as insulin/sulfonylurea therapy, as the degree of hyperglycemia may decrease with decreased dose of the glucocorticoid therapy.

2. Antipsychotic Therapy

Antipsychotic medications can be obesogenic; between 15% and 72% of people who take second-generation antipsychotics experience weight gain of 7% or more. Increases in weight are not the only factor contributing to an elevated risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Antipsychotics are thought to cause downregulation of intracellular insulin signaling, leading to insulin resistance. At the same time, there seems to be a direct effect on the pancreatic beta cells. Antagonism of the dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT2C, and muscarinic M3 receptors impairs beta-cell response to changes in blood glucose. In addition to the pharmacologic effects, cell culture experiments have shown that antipsychotics increase apoptosis of beta cells. Increased weight and concomitant development of type 2 diabetes is seen particularly in agents that exhibit high muscarinic M3 and histamine H1 receptor blockade. The effect on glucose metabolism is seen the most with agents such as clozapine, olanzapine, and haloperidol and the least with agents such as ziprasidone.

Management tip: Given the ongoing change in the understanding of increases in weight and their association with the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, a metabolically safer approach involves starting with medications that have a lower propensity for weight gain, and the partial agonists/third-generation antipsychotics as a family presently have the best overall data.

3. Thiazide Diuretics

Thiazide diuretics are commonly used for the management of hypertension and are associated with metabolic complications including hypokalemia; higher cholesterol, triglycerides, and other circulating lipids; and elevated glucose. It’s thought that the reduced potassium level occurring as a result of these medications might contribute to new-onset diabetes. The hypokalemia occurring from these medications is thought to lead to a decrease in insulin secretion and sensitivity, which is dose dependent. Studies show that the number needed to harm for chlorthalidone-induced diabetes is 29 over 1 year. There is believed to be no additional risk beyond 1 year.

Management tip: It’s important to monitor potassium levels for those initiated on thiazide diuretics. If hypokalemia occurs, it would be pertinent to correct the hypokalemia with potassium supplements to mitigate the risk for new-onset diabetes.

4. Statin Therapy

Statin therapy is thought to be associated with decreased insulin sensitivity and impairment in insulin secretion. The overall incidence of diabetes is pegged to be between 9% and 12% on statin therapy on the basis of meta-analysis studies, and higher on the basis of population-based studies. Overall, the estimated number needed to harm is: 1 out of every 255 patients on statin therapy for 4 years may develop new-onset diabetes. Compare this with the extremely strong evidence for number needed to treat being 39 for 5 years with statin therapy in patients with preexisting heart disease to prevent one occurrence of a nonfatal myocardial infarction.

Management tip: Although statins are associated with a small incident increase in the risk of developing diabetes, the potential benefits of using statin therapy for both primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease significantly outweigh any of the potential risks associated with hyperglycemia. This is an important discussion to have with patients who are reluctant to use statin therapy because of the potential risk for new-onset diabetes as a side effect.

5. Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers are another commonly used group of medications for managing hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, and arrhythmia. Nonvasodilating beta-blockers such as metoprolol and atenolol are more likely to be associated with increases in A1c, mean plasma glucose, body weight, and triglycerides compared with vasodilating beta-blockers such as carvedilol, nebivolol, and labetalol (Bakris GL et al; Giugliano D et al). Similarly, studies have also shown that atenolol and metoprolol are associated with increased odds of hypoglycemia compared with carvedilol. People on beta-blockers may have masking of some of the symptoms of hypoglycemia, such as tremor, irritability, and palpitations, while other symptoms such as diaphoresis may remain unaffected on beta-blockers.

Management tip: Education on recognizing and managing hypoglycemia would be important when starting patients on beta-blockers if they are on preexisting insulin/sulfonylurea therapy. Use of CGM devices may be helpful if there is a high risk for hypoglycemia, especially as symptoms of hypoglycemia are often masked.

Honorable Mention

Several other medications — including antiretroviral therapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, immunosuppressants, and interferon alpha — are associated with worsening glycemic control and new-onset diabetes. Consider these agents’ effects on blood glucose, especially in people with an elevated risk of developing diabetes or those with preexisting diabetes, when prescribing.

A special mention should also be made of androgen deprivation therapy. These include treatment options like goserelin and leuprolide, which are gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist therapies and are commonly used for prostate cancer management. Depending on the patient, these agents may be used for prolonged duration. Androgen deprivation therapy, by definition, decreases testosterone levels in men, thereby leading to worsening insulin resistance. Increase in fat mass and concomitant muscle wasting have been associated with the use of these medications; these, in turn, lead to peripheral insulin resistance. Nearly 1 out of every 5 men treated with long-term androgen deprivation therapy may be prone to developing worsening of A1c by 1% or more.

Management tip: Men on androgen deprivation therapy should be encouraged to participate in regular physical activity to reduce the burden of insulin resistance and to promote cardiovascular health.

Drug-induced diabetes is potentially reversible in many cases. Similarly, worsening of glycemic control due to medications in people with preexisting diabetes may also attenuate once the effect of the drug wears off. Blood glucose should be monitored on an ongoing basis so that diabetes medications can be adjusted. For some individuals, however, the worsening of glycemic status may be more chronic and may require long-term use of antihyperglycemic agents, especially if the benefits of continuation of the medication leading to hyperglycemia far exceed any potential risks.

Dr. Jain is Clinical Instructor, Department of Endocrinology, University of British Columbia; Endocrinologist, Fraser River Endocrinology, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s that time of the year, when social media is rife with many top 5 and top 10 lists. Let’s revisit some of the most commonly used medications known to increase glucose levels and look at some practical tips on overcoming these.

1. Glucocorticoids

Without a doubt, corticosteroids are at the top of the list when it comes to the potential for increasing blood glucose levels. High-dose glucocorticoid therapy is known to lead to new-onset diabetes (steroid-induced diabetes). Similarly, people with preexisting diabetes may notice significant worsening of glycemic control when they start on glucocorticoid therapy. The extent of glucose elevation depends on their glycemic status prior to initiation on steroids, the dose and duration of glucocorticoid therapy, and comorbid conditions, among other factors.