User login

Granulomatous Mycosis Fungoides With Clinical Features of Granulomatous Slack Skin

Double-Positive CD4+CD8+ Sézary Syndrome: An Unusual Phenotype With an Aggressive Clinical Course

myDermPath

What is it?

myDermPath is an interactive app designed as a learning and practice tool for dermatopathology. It contains a huge image library, diagnostic algorithms, glossaries, and more than 2000 image-based quiz questions.

How does it work?

The initial interface consists of 9 tabs, each directing the user down a different learning pathway. The tabs include About myDermPath, myDermPath Algorithm, Search By Diagnosis, Special Stains, Immunohistochemistry, Direct Immunofluorescence, Glossary Of Terms, Normal Skin Histology, and Ready For A Pop Quiz.

Histopathologic disease descriptions can be obtained through the interactive myDermPath Algorithm in which the user is walked through a short series of descriptive questions until a diagnosis is reached. Alternatively, the user can search by diagnosis. The final diagnosis page gives a brief description of histology, clinical characteristics, management, and differential diagnosis. A representative histologic image, an annotated image, and digital slide are provided. Finally, there are options to add your own notes, incorporate your own slides, or search the diagnosis on PubMed.

Short algorithms also are used to suggest special stains, immunohistochemistry, and direct immunofluorescence. Each stain or marker is paired with a representative slide. Searching directly for specific special stains, immunostains, or immunomarkers, however, is not possible.

Lastly, a section called Ready For A Pop Quiz randomly selects images from a database of more than 2000 slides and asks users to choose the best diagnosis for the presented slide from multiple choices. Each slide can be expanded to a very good detail, full-screen view.

How can it help me?

This app is a favorite of dermatology residents at my institution. Because it was written by 3 experts in dermatopathology, the information is reliable. The algorithms are quick to complete and the information provided is concise, allowing this app to be used by residents for a quick review during dermatopathology teaching sessions. The quiz bank with more 2000 high-quality slides is very convenient for short self-testing sessions. myDermPath is an excellent supplement to any dermatopathology learning program for the general dermatologist.

How can I get it?

myDermPath is free, so every dermatology learner should download this app and give it a try. It is available from the Apple App Store for your iPhone and iPad and from the Google Play Store.

If you would like to recommend an app, e-mail our Editorial Office.

What is it?

myDermPath is an interactive app designed as a learning and practice tool for dermatopathology. It contains a huge image library, diagnostic algorithms, glossaries, and more than 2000 image-based quiz questions.

How does it work?

The initial interface consists of 9 tabs, each directing the user down a different learning pathway. The tabs include About myDermPath, myDermPath Algorithm, Search By Diagnosis, Special Stains, Immunohistochemistry, Direct Immunofluorescence, Glossary Of Terms, Normal Skin Histology, and Ready For A Pop Quiz.

Histopathologic disease descriptions can be obtained through the interactive myDermPath Algorithm in which the user is walked through a short series of descriptive questions until a diagnosis is reached. Alternatively, the user can search by diagnosis. The final diagnosis page gives a brief description of histology, clinical characteristics, management, and differential diagnosis. A representative histologic image, an annotated image, and digital slide are provided. Finally, there are options to add your own notes, incorporate your own slides, or search the diagnosis on PubMed.

Short algorithms also are used to suggest special stains, immunohistochemistry, and direct immunofluorescence. Each stain or marker is paired with a representative slide. Searching directly for specific special stains, immunostains, or immunomarkers, however, is not possible.

Lastly, a section called Ready For A Pop Quiz randomly selects images from a database of more than 2000 slides and asks users to choose the best diagnosis for the presented slide from multiple choices. Each slide can be expanded to a very good detail, full-screen view.

How can it help me?

This app is a favorite of dermatology residents at my institution. Because it was written by 3 experts in dermatopathology, the information is reliable. The algorithms are quick to complete and the information provided is concise, allowing this app to be used by residents for a quick review during dermatopathology teaching sessions. The quiz bank with more 2000 high-quality slides is very convenient for short self-testing sessions. myDermPath is an excellent supplement to any dermatopathology learning program for the general dermatologist.

How can I get it?

myDermPath is free, so every dermatology learner should download this app and give it a try. It is available from the Apple App Store for your iPhone and iPad and from the Google Play Store.

If you would like to recommend an app, e-mail our Editorial Office.

What is it?

myDermPath is an interactive app designed as a learning and practice tool for dermatopathology. It contains a huge image library, diagnostic algorithms, glossaries, and more than 2000 image-based quiz questions.

How does it work?

The initial interface consists of 9 tabs, each directing the user down a different learning pathway. The tabs include About myDermPath, myDermPath Algorithm, Search By Diagnosis, Special Stains, Immunohistochemistry, Direct Immunofluorescence, Glossary Of Terms, Normal Skin Histology, and Ready For A Pop Quiz.

Histopathologic disease descriptions can be obtained through the interactive myDermPath Algorithm in which the user is walked through a short series of descriptive questions until a diagnosis is reached. Alternatively, the user can search by diagnosis. The final diagnosis page gives a brief description of histology, clinical characteristics, management, and differential diagnosis. A representative histologic image, an annotated image, and digital slide are provided. Finally, there are options to add your own notes, incorporate your own slides, or search the diagnosis on PubMed.

Short algorithms also are used to suggest special stains, immunohistochemistry, and direct immunofluorescence. Each stain or marker is paired with a representative slide. Searching directly for specific special stains, immunostains, or immunomarkers, however, is not possible.

Lastly, a section called Ready For A Pop Quiz randomly selects images from a database of more than 2000 slides and asks users to choose the best diagnosis for the presented slide from multiple choices. Each slide can be expanded to a very good detail, full-screen view.

How can it help me?

This app is a favorite of dermatology residents at my institution. Because it was written by 3 experts in dermatopathology, the information is reliable. The algorithms are quick to complete and the information provided is concise, allowing this app to be used by residents for a quick review during dermatopathology teaching sessions. The quiz bank with more 2000 high-quality slides is very convenient for short self-testing sessions. myDermPath is an excellent supplement to any dermatopathology learning program for the general dermatologist.

How can I get it?

myDermPath is free, so every dermatology learner should download this app and give it a try. It is available from the Apple App Store for your iPhone and iPad and from the Google Play Store.

If you would like to recommend an app, e-mail our Editorial Office.

Circumscribed Acral Hypokeratosis: A Report of 2 Cases and a Brief Review of the Literature

Test your knowledge on circumscribed acral hypokeratosis with MD-IQ: the medical intelligence quiz. Click here to answer 5 questions.

Primary Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis of the Feet: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Test your knowledge on cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with MD-IQ: the medical intelligence quiz. Click here to answer 5 questions.

Chondroid Syringoma

Atrophic Erythematous Facial Plaques

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

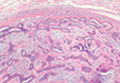

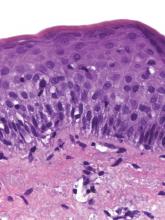

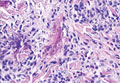

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

A 26-year-old woman presented with a 2-year history of facial lesions that had gradually increased in size and number. Initially they were tender and pruritic but eventually became asymptomatic. She denied aggravation with sun exposure and did not use regular sun protection. Multiple pulsed dye laser treatments to the lesions had not resulted in appreciable improvement. Review of systems revealed occasional blurred vision and joint pain in her wrist and fingers of her right hand. Physical examination revealed a healthy-appearing woman. On the forehead and bilateral cheeks there were multiple atrophic, erythematous, sunken plaques with discrete borders. Each plaque measured more than 5 mm. Similar plaques were scattered across the frontal scalp, trunk, and upper extremities, though fewer in number and less atrophic with mild hyperpigmentation. There was diffuse hair thinning of the scalp. Laboratory test results included a normal complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody profile, and complete blood cell count. Histopathology revealed a superficial and mid perivascular and perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and melanophages. Vacuolar changes in the dermoepidermal junction were present. There were few dyskeratotic keratinocytes and mucin deposition present in the dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was not performed.