User login

Bowel-Associated Dermatosis-Arthritis Syndrome in a Patient With Crohn Disease

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman with Crohn disease of 10 years’ duration presented to the clinic with a chief concern of nonpruritic pustular lesions on the bilateral arms. Physical examination revealed several pustules on the arms with secondary excoriation. She also had a warm tender nodule on the left upper shin and subungual hemorrhages under the fingernails (Figure 1). The patient had previously undergone infliximab therapy, which was discontinued 10 months prior to presentation in anticipation of a partial colectomy and temporary ileostomy that was performed 8 months prior to presentation. She recently had developed bilateral, radiating, sharp lower extremity pain extending from the feet to the hips over the last 2 weeks and swelling of the bilateral legs that impaired her ability to ambulate. Additionally, she had recently traveled to Colorado and a Lyme disease workup was initiated at an outside hospital in Colorado; however, the results were pending. The outside hospital also performed a spinal tap that was negative. At our clinic, biopsies were performed on the shin nodule and a right palmar pustule (Figure 2). There was clinical suspicion of erythema nodosum and subcorneal pustular dermatosis or a vesiculopustular skin manifestation of the patient’s Crohn disease. The patient was switched from generic doxycycline to a brand name variant 150 mg every night at bedtime for 2 weeks. She subsequently was admitted to the inpatient rheumatology service for a complete systemic workup.

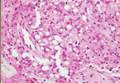

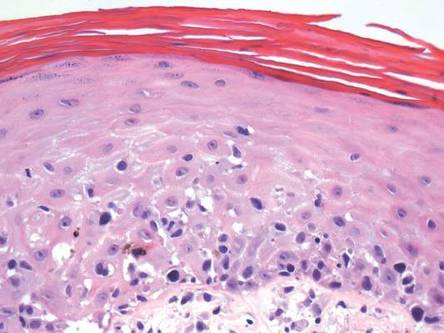

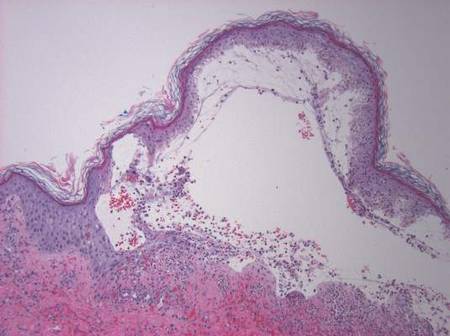

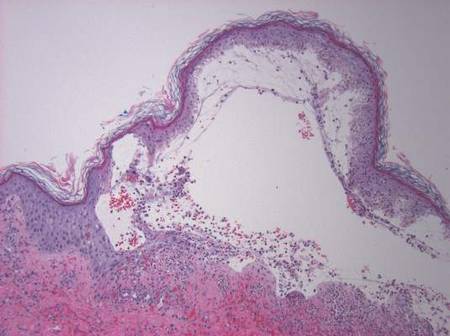

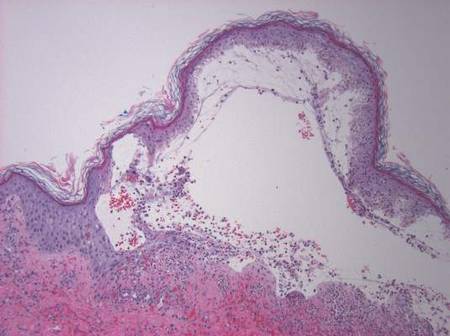

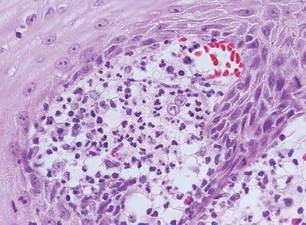

The punch biopsy of the left upper shin demonstrated operative hemorrhage and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation without evidence of fungal or bacterial elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Clinically, the diagnosis was most likely erythema nodosum, though insufficient hypodermis was present to make the diagnosis with pathology. The shave biopsy of the right medial palm was nondiagnostic but showed a transected pustule with no bacterial or fungal elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 3). Given the clinical context, the likely pathologic diagnosis was vesiculopustular Crohn disease.

Our patient was started on an empiric steroid trial with rapid improvement of the arthralgia and rash. The presumed diagnosis was a Crohn disease flare and the patient was discharged on an 8-week steroid taper. Three weeks later at a follow-up appointment, the patient’s skin lesions had nearly resolved. The swelling of the legs and feet had substantially decreased, but the joint pain, primarily in the ankles, persisted.

Routine laboratory studies showed a hemoglobin level of 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL), white blood cell count of 9.1 K/μL (reference range, 4.5–11.0 K/μL), C-reactive protein level of 20.15 mg/dL (reference range, <1.0 mg/dL), and an antinuclear antibody titer of 160 (<80). Serology for Lyme disease was negative. Serum chemistries were all within reference range and an echocardiogram was normal.

Up to one-third of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) experience extraintestinal manifestations of their condition. Of these patients, nearly one-third will develop cutaneous manifestations.1 The most common skin diseases associated with IBD are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum.2 The differential diagnoses considered in this unique case included early pyoderma gangrenosum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), and vesiculopustular Crohn disease. Vesiculopustular Crohn disease is a rare component of IBD and also can be present in bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome (BADAS). In BADAS, symptoms often include arthritis and systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. The skin manifestations typically involve the arms and trunk. It often is seen after intestinal bypass surgery but also can be present in patients with gastrointestinal diseases such as IBD.3 Due to its early association with bypass surgery, BADAS previously was referred to as bowel bypass syndrome but has since been seen in relation to other intestinal surgeries and IBD.4 Patients with BADAS often present with episodes of fever, fatigue, and malaise, in addition to arthralgia and cutaneous eruptions. Cases of BADAS related to IBD instead of bypass surgery often can be less severe in nature. Unlike many of these previously reported cases, our patient’s joint pain primarily was in the knees and ankles, whereas typical cases of BADAS cause upper extremity (ie, shoulder, elbow) arthralgia. Our patient occasionally experienced upper extremity pain, but it was less frequent and less severe than the knee and ankle pain. The vesiculopustular lesions in BADAS usually begin as 3- to 10-mm painful macules that then develop into aseptic pustular lesions. These manifestations arise on the upper arms and chest or trunk and can be accompanied by erythema nodosum on the legs.4

It has been hypothesized that BADAS occurs as an immune reaction to bacterial overgrowth in the bowel from IBD, infection, or surgery. The reaction is in response to a bacterial antigen and manifests cutaneously.5 This same pathogenesis is thought to cause various other manifestations of Crohn disease such as erythema nodosum. Bacteria that incite this immune response include Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus.

Resolution of both vesiculopustular Crohn disease and of BADAS often occurs with treatment of the underlying IBD but also can be improved with steroids and antibiotics. However, response to antibiotics often is variable.5,6 The mainstay for treatment remains steroids and management of underlying bowel disease.

Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome often is overlooked when compiling differential diagnoses for neutrophilic dermatoses but should be considered in patients with bowel disease or recent surgery. Because the syndrome can be recurrent, early diagnosis can help to prevent and treat relapsing courses of BADAS.

- Trost LB, McDonnell JK. Important cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:580-585.

- Havemann BD. A pustular skin rash in a woman with 2 weeks of diarrhea. MedGenMed. 2005;7:11.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

- Huang B, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:13.

- Truchuelo MT, Alcántara J, Vano-Galván S, et al. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: another cutaneous manifestation of inflammatory intestinal disease. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1596-1598.

- Ashok D, Kiely P. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:81.

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman with Crohn disease of 10 years’ duration presented to the clinic with a chief concern of nonpruritic pustular lesions on the bilateral arms. Physical examination revealed several pustules on the arms with secondary excoriation. She also had a warm tender nodule on the left upper shin and subungual hemorrhages under the fingernails (Figure 1). The patient had previously undergone infliximab therapy, which was discontinued 10 months prior to presentation in anticipation of a partial colectomy and temporary ileostomy that was performed 8 months prior to presentation. She recently had developed bilateral, radiating, sharp lower extremity pain extending from the feet to the hips over the last 2 weeks and swelling of the bilateral legs that impaired her ability to ambulate. Additionally, she had recently traveled to Colorado and a Lyme disease workup was initiated at an outside hospital in Colorado; however, the results were pending. The outside hospital also performed a spinal tap that was negative. At our clinic, biopsies were performed on the shin nodule and a right palmar pustule (Figure 2). There was clinical suspicion of erythema nodosum and subcorneal pustular dermatosis or a vesiculopustular skin manifestation of the patient’s Crohn disease. The patient was switched from generic doxycycline to a brand name variant 150 mg every night at bedtime for 2 weeks. She subsequently was admitted to the inpatient rheumatology service for a complete systemic workup.

The punch biopsy of the left upper shin demonstrated operative hemorrhage and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation without evidence of fungal or bacterial elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Clinically, the diagnosis was most likely erythema nodosum, though insufficient hypodermis was present to make the diagnosis with pathology. The shave biopsy of the right medial palm was nondiagnostic but showed a transected pustule with no bacterial or fungal elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 3). Given the clinical context, the likely pathologic diagnosis was vesiculopustular Crohn disease.

Our patient was started on an empiric steroid trial with rapid improvement of the arthralgia and rash. The presumed diagnosis was a Crohn disease flare and the patient was discharged on an 8-week steroid taper. Three weeks later at a follow-up appointment, the patient’s skin lesions had nearly resolved. The swelling of the legs and feet had substantially decreased, but the joint pain, primarily in the ankles, persisted.

Routine laboratory studies showed a hemoglobin level of 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL), white blood cell count of 9.1 K/μL (reference range, 4.5–11.0 K/μL), C-reactive protein level of 20.15 mg/dL (reference range, <1.0 mg/dL), and an antinuclear antibody titer of 160 (<80). Serology for Lyme disease was negative. Serum chemistries were all within reference range and an echocardiogram was normal.

Up to one-third of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) experience extraintestinal manifestations of their condition. Of these patients, nearly one-third will develop cutaneous manifestations.1 The most common skin diseases associated with IBD are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum.2 The differential diagnoses considered in this unique case included early pyoderma gangrenosum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), and vesiculopustular Crohn disease. Vesiculopustular Crohn disease is a rare component of IBD and also can be present in bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome (BADAS). In BADAS, symptoms often include arthritis and systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. The skin manifestations typically involve the arms and trunk. It often is seen after intestinal bypass surgery but also can be present in patients with gastrointestinal diseases such as IBD.3 Due to its early association with bypass surgery, BADAS previously was referred to as bowel bypass syndrome but has since been seen in relation to other intestinal surgeries and IBD.4 Patients with BADAS often present with episodes of fever, fatigue, and malaise, in addition to arthralgia and cutaneous eruptions. Cases of BADAS related to IBD instead of bypass surgery often can be less severe in nature. Unlike many of these previously reported cases, our patient’s joint pain primarily was in the knees and ankles, whereas typical cases of BADAS cause upper extremity (ie, shoulder, elbow) arthralgia. Our patient occasionally experienced upper extremity pain, but it was less frequent and less severe than the knee and ankle pain. The vesiculopustular lesions in BADAS usually begin as 3- to 10-mm painful macules that then develop into aseptic pustular lesions. These manifestations arise on the upper arms and chest or trunk and can be accompanied by erythema nodosum on the legs.4

It has been hypothesized that BADAS occurs as an immune reaction to bacterial overgrowth in the bowel from IBD, infection, or surgery. The reaction is in response to a bacterial antigen and manifests cutaneously.5 This same pathogenesis is thought to cause various other manifestations of Crohn disease such as erythema nodosum. Bacteria that incite this immune response include Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus.

Resolution of both vesiculopustular Crohn disease and of BADAS often occurs with treatment of the underlying IBD but also can be improved with steroids and antibiotics. However, response to antibiotics often is variable.5,6 The mainstay for treatment remains steroids and management of underlying bowel disease.

Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome often is overlooked when compiling differential diagnoses for neutrophilic dermatoses but should be considered in patients with bowel disease or recent surgery. Because the syndrome can be recurrent, early diagnosis can help to prevent and treat relapsing courses of BADAS.

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman with Crohn disease of 10 years’ duration presented to the clinic with a chief concern of nonpruritic pustular lesions on the bilateral arms. Physical examination revealed several pustules on the arms with secondary excoriation. She also had a warm tender nodule on the left upper shin and subungual hemorrhages under the fingernails (Figure 1). The patient had previously undergone infliximab therapy, which was discontinued 10 months prior to presentation in anticipation of a partial colectomy and temporary ileostomy that was performed 8 months prior to presentation. She recently had developed bilateral, radiating, sharp lower extremity pain extending from the feet to the hips over the last 2 weeks and swelling of the bilateral legs that impaired her ability to ambulate. Additionally, she had recently traveled to Colorado and a Lyme disease workup was initiated at an outside hospital in Colorado; however, the results were pending. The outside hospital also performed a spinal tap that was negative. At our clinic, biopsies were performed on the shin nodule and a right palmar pustule (Figure 2). There was clinical suspicion of erythema nodosum and subcorneal pustular dermatosis or a vesiculopustular skin manifestation of the patient’s Crohn disease. The patient was switched from generic doxycycline to a brand name variant 150 mg every night at bedtime for 2 weeks. She subsequently was admitted to the inpatient rheumatology service for a complete systemic workup.

The punch biopsy of the left upper shin demonstrated operative hemorrhage and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation without evidence of fungal or bacterial elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Clinically, the diagnosis was most likely erythema nodosum, though insufficient hypodermis was present to make the diagnosis with pathology. The shave biopsy of the right medial palm was nondiagnostic but showed a transected pustule with no bacterial or fungal elements by Gram or Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 3). Given the clinical context, the likely pathologic diagnosis was vesiculopustular Crohn disease.

Our patient was started on an empiric steroid trial with rapid improvement of the arthralgia and rash. The presumed diagnosis was a Crohn disease flare and the patient was discharged on an 8-week steroid taper. Three weeks later at a follow-up appointment, the patient’s skin lesions had nearly resolved. The swelling of the legs and feet had substantially decreased, but the joint pain, primarily in the ankles, persisted.

Routine laboratory studies showed a hemoglobin level of 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL), white blood cell count of 9.1 K/μL (reference range, 4.5–11.0 K/μL), C-reactive protein level of 20.15 mg/dL (reference range, <1.0 mg/dL), and an antinuclear antibody titer of 160 (<80). Serology for Lyme disease was negative. Serum chemistries were all within reference range and an echocardiogram was normal.

Up to one-third of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) experience extraintestinal manifestations of their condition. Of these patients, nearly one-third will develop cutaneous manifestations.1 The most common skin diseases associated with IBD are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum.2 The differential diagnoses considered in this unique case included early pyoderma gangrenosum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), and vesiculopustular Crohn disease. Vesiculopustular Crohn disease is a rare component of IBD and also can be present in bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome (BADAS). In BADAS, symptoms often include arthritis and systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise. The skin manifestations typically involve the arms and trunk. It often is seen after intestinal bypass surgery but also can be present in patients with gastrointestinal diseases such as IBD.3 Due to its early association with bypass surgery, BADAS previously was referred to as bowel bypass syndrome but has since been seen in relation to other intestinal surgeries and IBD.4 Patients with BADAS often present with episodes of fever, fatigue, and malaise, in addition to arthralgia and cutaneous eruptions. Cases of BADAS related to IBD instead of bypass surgery often can be less severe in nature. Unlike many of these previously reported cases, our patient’s joint pain primarily was in the knees and ankles, whereas typical cases of BADAS cause upper extremity (ie, shoulder, elbow) arthralgia. Our patient occasionally experienced upper extremity pain, but it was less frequent and less severe than the knee and ankle pain. The vesiculopustular lesions in BADAS usually begin as 3- to 10-mm painful macules that then develop into aseptic pustular lesions. These manifestations arise on the upper arms and chest or trunk and can be accompanied by erythema nodosum on the legs.4

It has been hypothesized that BADAS occurs as an immune reaction to bacterial overgrowth in the bowel from IBD, infection, or surgery. The reaction is in response to a bacterial antigen and manifests cutaneously.5 This same pathogenesis is thought to cause various other manifestations of Crohn disease such as erythema nodosum. Bacteria that incite this immune response include Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus.

Resolution of both vesiculopustular Crohn disease and of BADAS often occurs with treatment of the underlying IBD but also can be improved with steroids and antibiotics. However, response to antibiotics often is variable.5,6 The mainstay for treatment remains steroids and management of underlying bowel disease.

Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome often is overlooked when compiling differential diagnoses for neutrophilic dermatoses but should be considered in patients with bowel disease or recent surgery. Because the syndrome can be recurrent, early diagnosis can help to prevent and treat relapsing courses of BADAS.

- Trost LB, McDonnell JK. Important cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:580-585.

- Havemann BD. A pustular skin rash in a woman with 2 weeks of diarrhea. MedGenMed. 2005;7:11.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

- Huang B, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:13.

- Truchuelo MT, Alcántara J, Vano-Galván S, et al. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: another cutaneous manifestation of inflammatory intestinal disease. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1596-1598.

- Ashok D, Kiely P. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:81.

- Trost LB, McDonnell JK. Important cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:580-585.

- Havemann BD. A pustular skin rash in a woman with 2 weeks of diarrhea. MedGenMed. 2005;7:11.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

- Huang B, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:13.

- Truchuelo MT, Alcántara J, Vano-Galván S, et al. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: another cutaneous manifestation of inflammatory intestinal disease. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1596-1598.

- Ashok D, Kiely P. Bowel associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:81.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Mycosis Fungoides

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

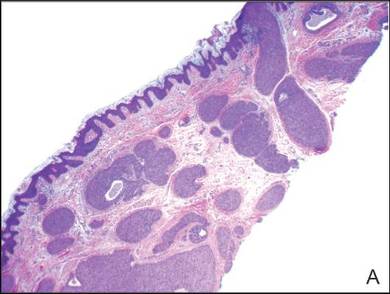

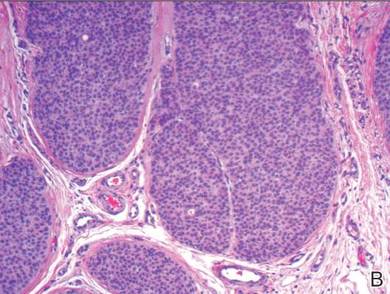

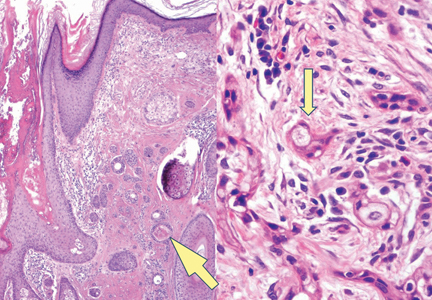

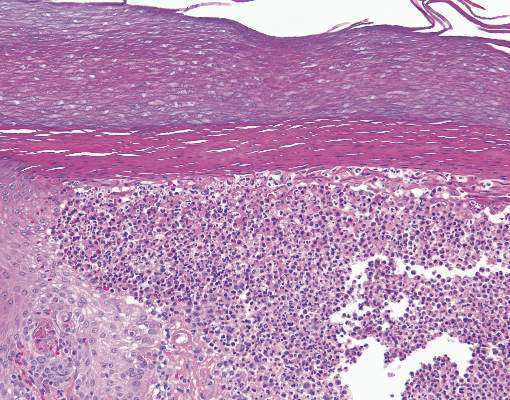

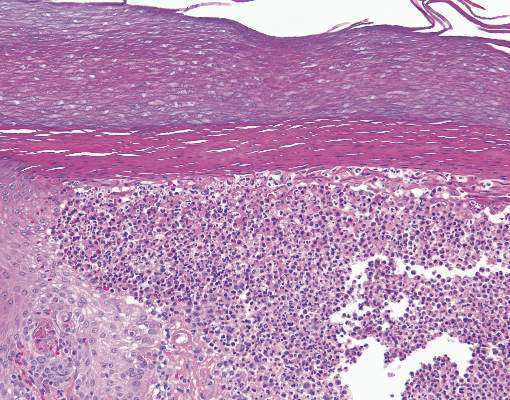

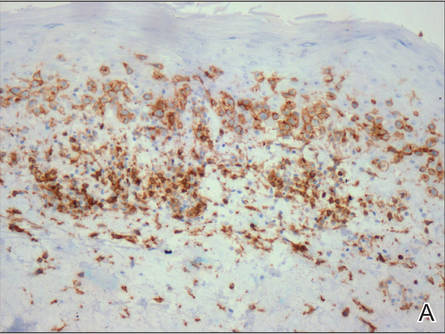

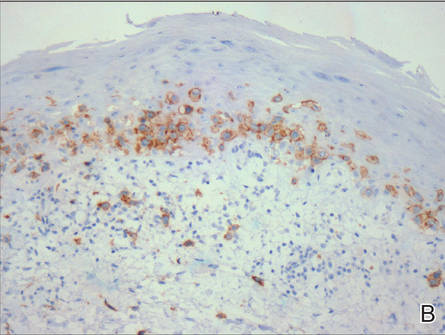

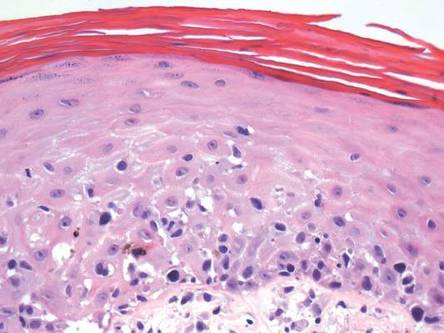

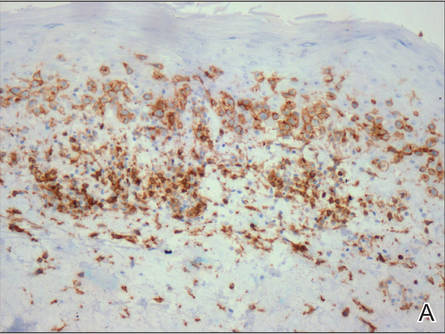

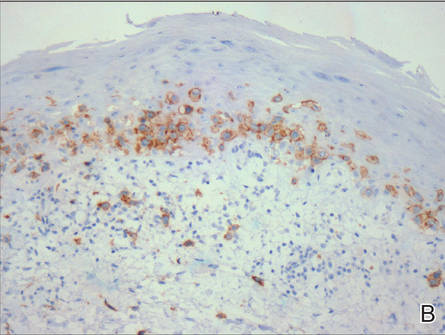

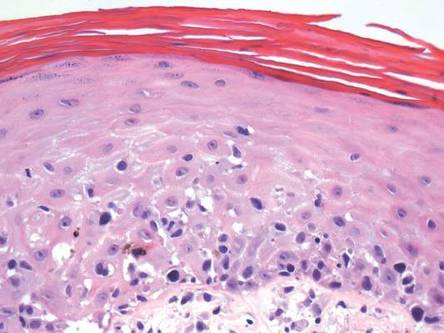

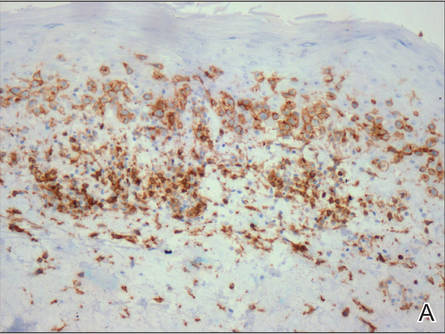

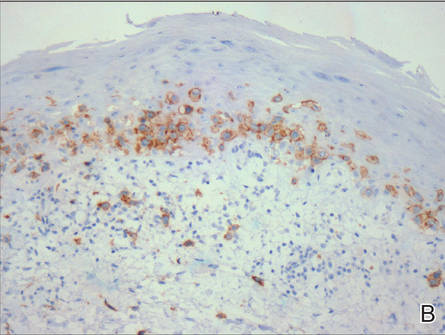

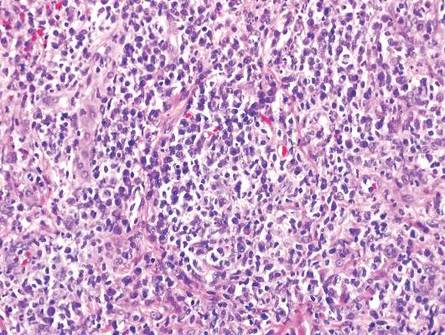

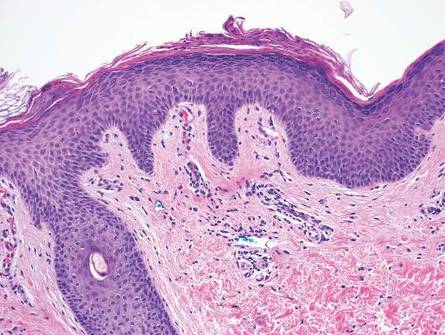

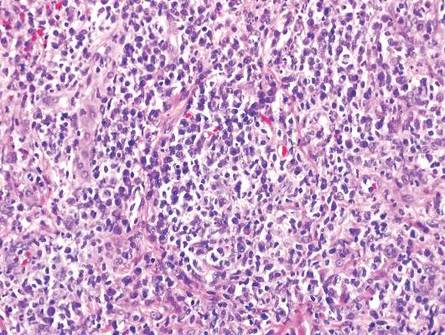

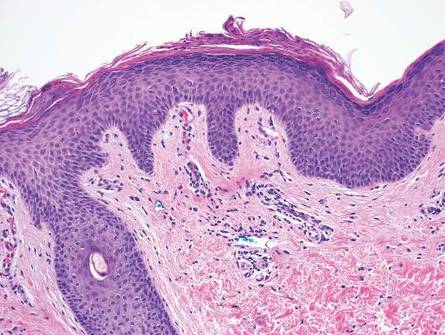

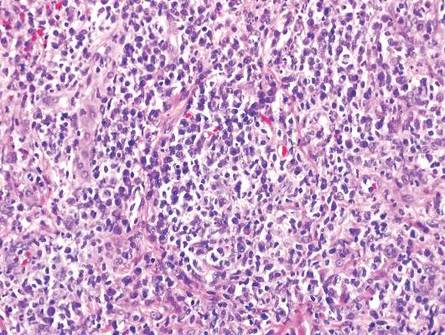

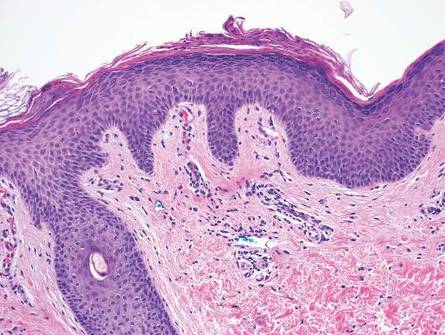

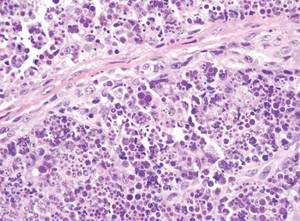

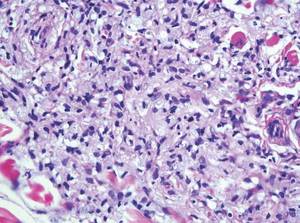

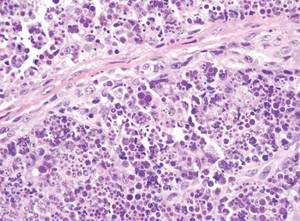

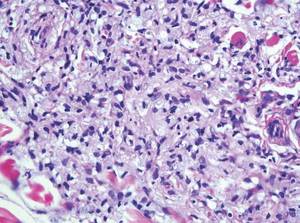

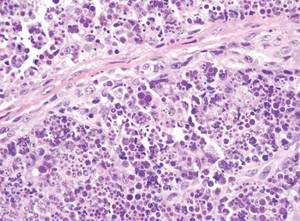

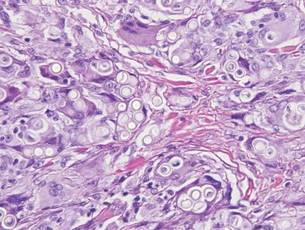

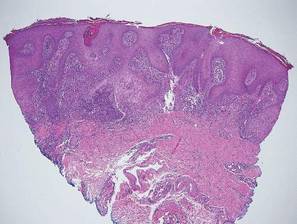

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

An otherwise healthy 62-year-old man presented for evaluation of multiple scaly erythematous plaques on the right upper arm and shoulder of 10 years’ duration. The patient reported a burning sensation but no exacerbation of the lesions upon sun exposure. He previously had been treated for a presumed clinical diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum but experienced only modest improvement with topical corticosteroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Previous trials of systemic antifungals also yielded minimal benefit.

Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

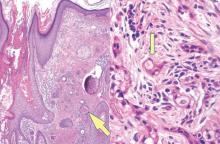

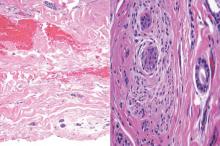

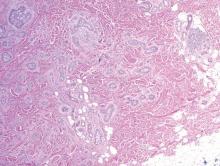

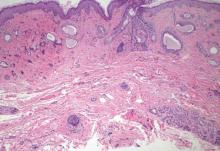

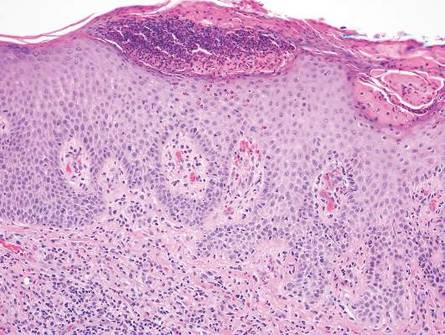

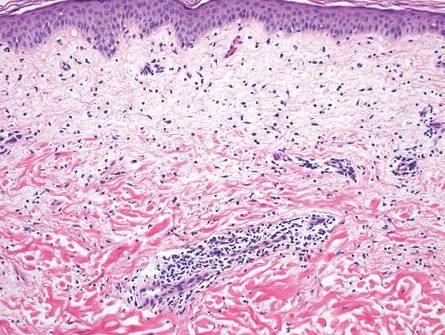

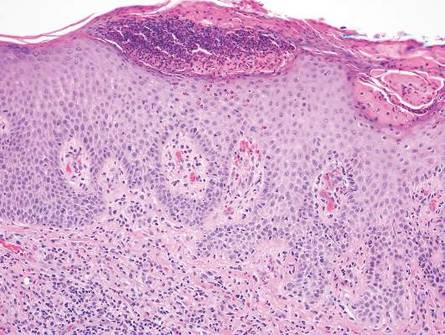

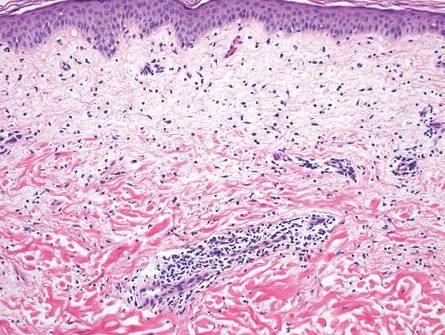

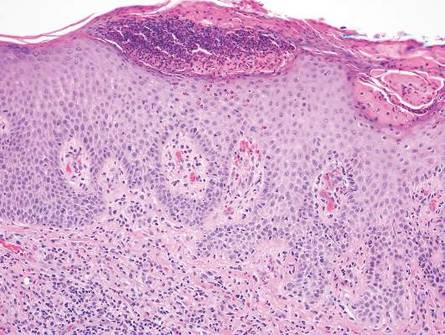

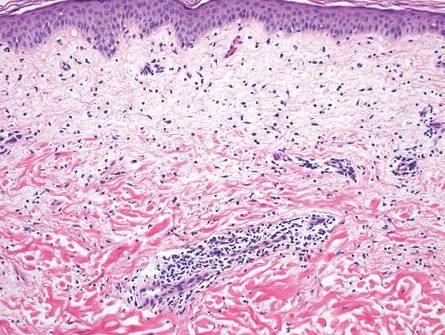

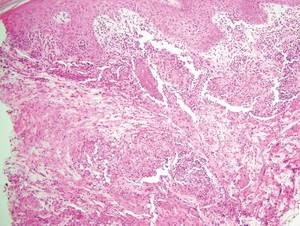

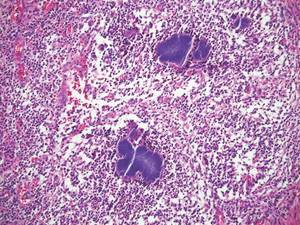

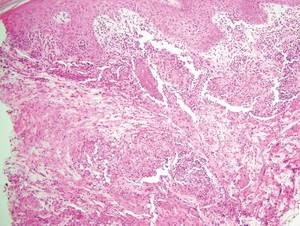

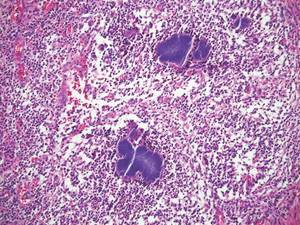

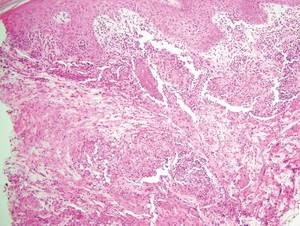

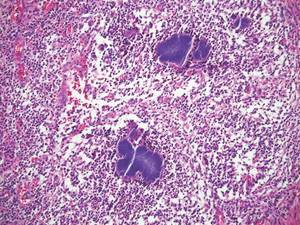

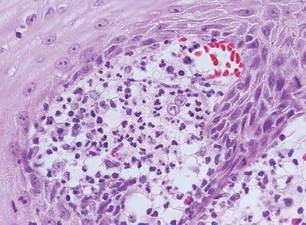

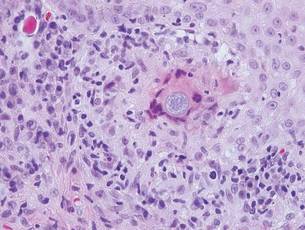

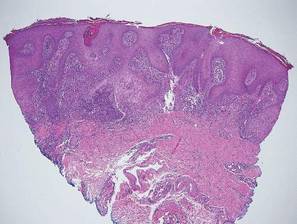

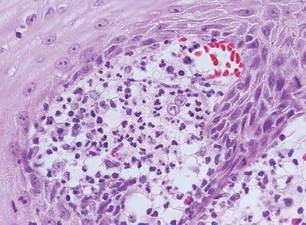

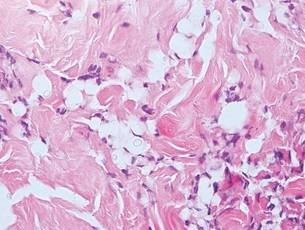

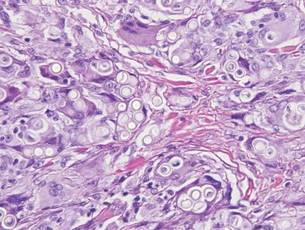

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

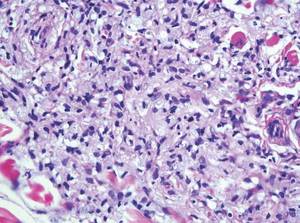

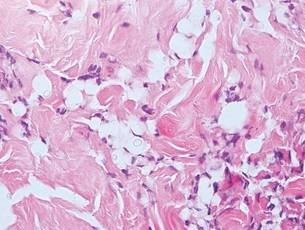

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

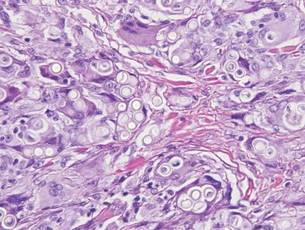

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

Erythematous Scaly Papules on the Shins and Calves

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

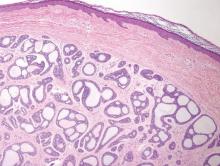

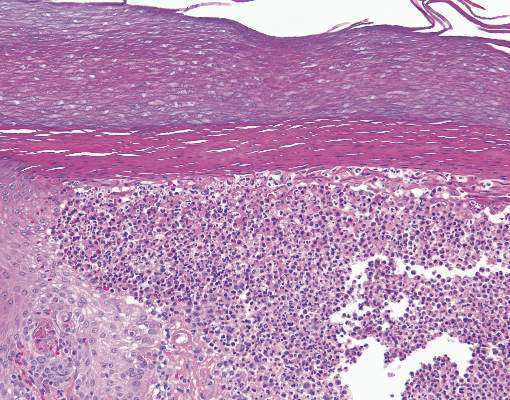

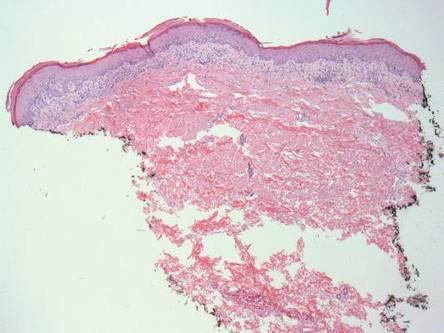

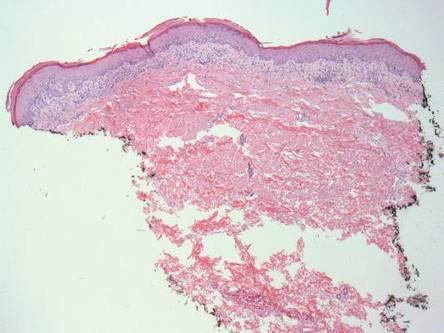

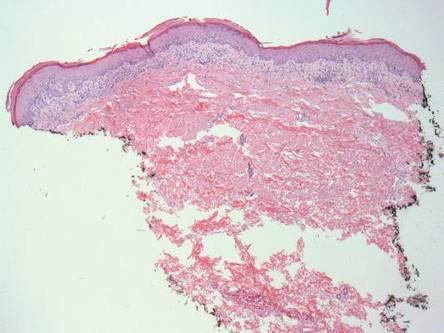

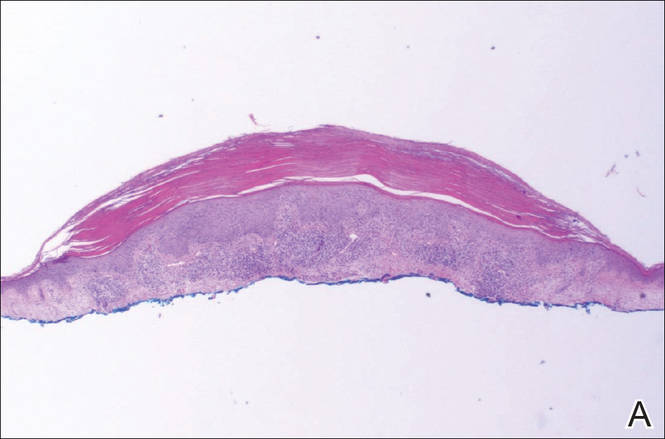

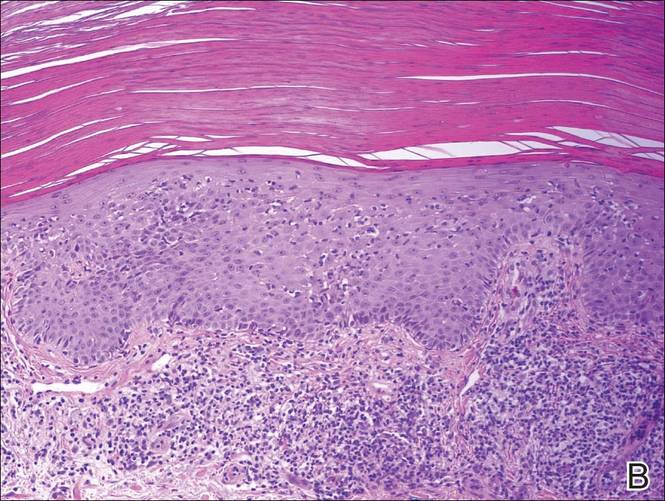

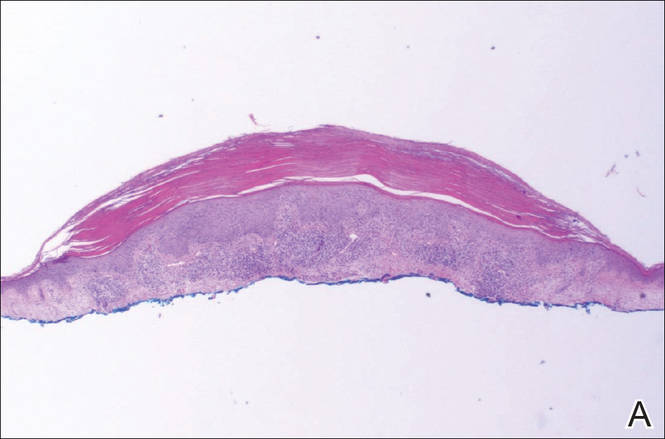

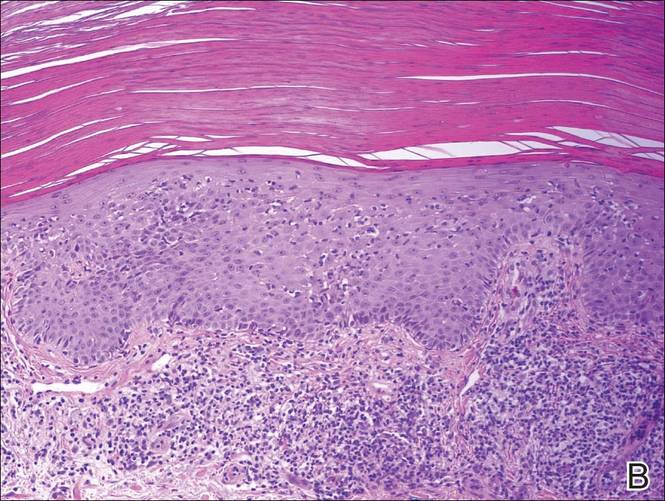

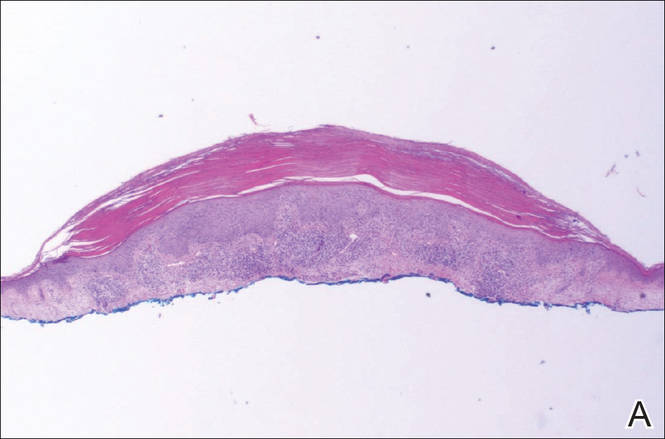

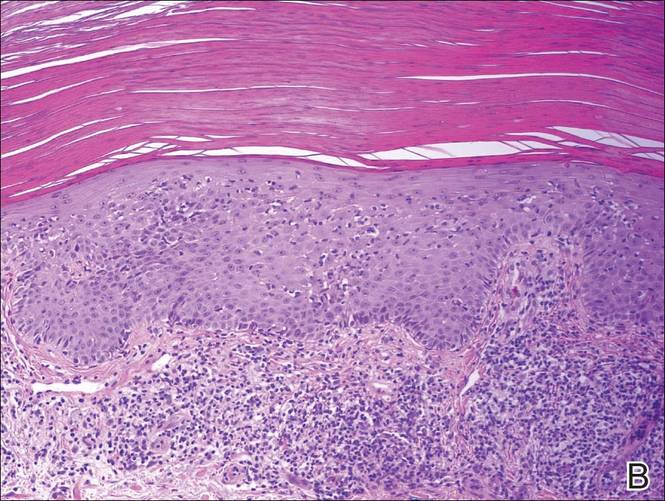

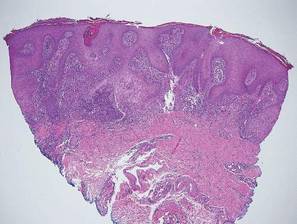

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

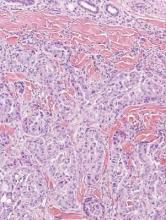

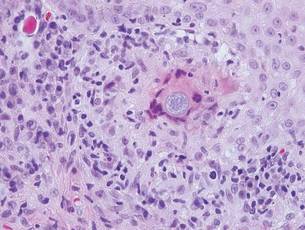

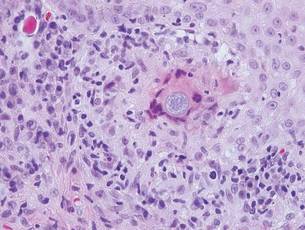

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection caused by intracellular organisms found in tropical climates. Old World leishmaniasis is endemic to Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe, while New World leishmaniasis is native to Central and South Americas.1 Depending upon a host’s immune status and the specific Leishmania species, clinical presentations vary in appearance and severity, ranging from self-limited, localized cutaneous disease to potentially fatal visceral and mucocutaneous involvement. Most cutaneous manifestations of leishmaniasis begin as distinct, painless papules that may progress to nodules or become ulcerated over time.1 Histologically, leishmaniasis is diagnosed by the identification of intracellular organisms that characteristically align along the peripheral rim inside the vacuole of a histiocyte.2 This unique finding is called the “marquee sign” due to its resemblance to light bulbs arranged around a dressing room mirror (Figure 1).2Leishmania amastigotes (also known as Leishman-Donovan bodies) have kinetoplasts that are helpful in diagnosis but also may be difficult to detect.2 Along with the Leishmania parasites, there typically is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 2).1,2 There also may be varying degrees of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and overlying epidermal ulceration.1

Cutaneous botryomycosis can present clinically as a number of various primary lesions, including papules, nodules, or ulcers that may resemble leishmaniasis.3 Botryomycosis represents a specific histologic collection of bacterial granules, most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus.3 The dermal granulomatous infiltrate seen in botryomycosis often is similar to that seen in chronic leishmaniasis; however, one histologic feature unique to botryomycosis is the presence of characteristic basophilic staphylococcal grains that are arranged in clusters resembling bunches of grapes (the term botryo means “bunch of grapes” in Greek).3 A thin, eosinophilic rim consisting of antibodies, bacterial debris, and complement proteins and glycoproteins may encircle the basophilic grains but does not need to be present for diagnosis (Figure 3).3

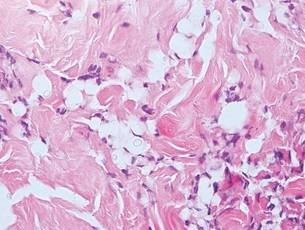

Lepromatous leprosy presents as a symmetric, widespread eruption of macules, patches, plaques, or papules that are most prominent in acral areas.4 Perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes is characteristic of lepromatous leprosy.2 Mycobacteria bacilli also are seen within histiocytic vacuoles, similarly to leishmaniasis; however, collections of these bacilli congregate within the center of a foamy histiocyte to form a distinctive histologic finding known as a globus. These individual histiocytes containing central globi are called Virchow cells (Figure 4).2 However, lepromatous leprosy can be distinguished from leishmaniasis histologically by carefully observing the intracellular location of the infectious organism. Mycobacteria bacilli are located in the center of a histiocyte vacuole whereas Leishmania parasites demonstrate a peripheral alignment along a histiocyte vacuole. If any uncertainty remains between a diagnosis of leishmaniasis and lepromatous leprosy, positive Fite staining for mycobacteria easily differentiates between the 2 conditions.2,4

Cutaneous lobomycosis, a rare fungal infection transmitted by dolphins, manifests clinically as an asymptomatic nodule that is similar in appearance to a keloid. Histologic similarities to leishmaniasis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and dermal granulomatous inflammation.4 The most distinguishing characteristic of lobomycosis is the presence of round, thick-walled, white organisms connected in a “string of beads” or chainlike configuration (Figure 5).2 Unlike leishmaniasis, lobomycosis fungal organisms would stain positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.4

Cutaneous protothecosis is a rare clinical entity that presents as an isolated nodule or plaque or bursitis.4 It occurs following minor trauma and inoculation with Prototheca organisms, a genus of algae found in contaminated water.2,4 In its morula form, Prototheca adopts a characteristic arrangement within histiocytes that strikingly resembles a soccer ball (Figure 6).2 Conversely, nonmorulating forms of protothecosis can also be seen; these exhibit a central basophilic, dotlike structure within the histiocytes surrounded by a white halo.2 Definitive diagnosis of protothecosis can only be made upon successful culture of the algae.5

- Kevric I, Cappel MA, Keeling JH. New World and Old World leishmania infections: a practical review. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:579-593.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- De Vries HJ, Van Noesel CJ, Hoekzema R, et al. Botryomycosis in an HIV-positive subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:87-90.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2012.

- Hillesheim PB, Bahrami S. Cutaneous protothecosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:941-944.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection caused by intracellular organisms found in tropical climates. Old World leishmaniasis is endemic to Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe, while New World leishmaniasis is native to Central and South Americas.1 Depending upon a host’s immune status and the specific Leishmania species, clinical presentations vary in appearance and severity, ranging from self-limited, localized cutaneous disease to potentially fatal visceral and mucocutaneous involvement. Most cutaneous manifestations of leishmaniasis begin as distinct, painless papules that may progress to nodules or become ulcerated over time.1 Histologically, leishmaniasis is diagnosed by the identification of intracellular organisms that characteristically align along the peripheral rim inside the vacuole of a histiocyte.2 This unique finding is called the “marquee sign” due to its resemblance to light bulbs arranged around a dressing room mirror (Figure 1).2Leishmania amastigotes (also known as Leishman-Donovan bodies) have kinetoplasts that are helpful in diagnosis but also may be difficult to detect.2 Along with the Leishmania parasites, there typically is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 2).1,2 There also may be varying degrees of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and overlying epidermal ulceration.1

Cutaneous botryomycosis can present clinically as a number of various primary lesions, including papules, nodules, or ulcers that may resemble leishmaniasis.3 Botryomycosis represents a specific histologic collection of bacterial granules, most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus.3 The dermal granulomatous infiltrate seen in botryomycosis often is similar to that seen in chronic leishmaniasis; however, one histologic feature unique to botryomycosis is the presence of characteristic basophilic staphylococcal grains that are arranged in clusters resembling bunches of grapes (the term botryo means “bunch of grapes” in Greek).3 A thin, eosinophilic rim consisting of antibodies, bacterial debris, and complement proteins and glycoproteins may encircle the basophilic grains but does not need to be present for diagnosis (Figure 3).3