User login

In-hospital mortality increased in COPD patients with acute exacerbations and high serum phosphate levels

found significantly higher in-hospital mortality among AECOPD patients with high serum phosphate levels. The finding, according to Siqi Li et al. in a preproof HELIYON article, suggests that hyperphosphatemia may be a high-risk factor for AECOPD-related in-hospital mortality.

Phosphorus is key to several physiological processes, among them energy metabolism, bone mineralization, membrane transport, and intracellular signaling. Li et al. pointed out that in patients with multiple diseases, hyperphosphatemia is associated with increased mortality. In the development of COPD specifically, acute exacerbations have been shown in several recent studies to be an important adverse event conferring heightened mortality risk. Despite many efforts, AECOPD mortality rates remain high, making identification of potential factors, Li et al. stated, crucial for improving outcomes in high-risk patients.

The electronic Intensive Care Unit Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD) holds data associated with over 200,000 patient stays, providing a large sample size for research studies. To determine the relationship between serum phosphate and in-hospital mortality in AECOPD patients, investigators analyzed data from a total of 1,199 AECOPD patients (mean age, 68 years; ~55% female) enrolled in eICU-CRD and divided them into three groups according to serum phosphate level tertiles: lowest tertile (serum phosphate ≤ 3.0 mg/dL, n = 445), median tertile (serum phosphate > 3.0 mg/dL and ≤ 4.0 mg/dL, n = 378), and highest tertile (serum phosphate > 4.0 mg/dL, n = 376). The Li et al. study’s primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality, defined as survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included length of stay (LOS) in the intensive care unit (ICU), LOS in the hospital, and all-cause ICU mortality.

The Li et al. analysis of patient characteristics showed that patients in the highest tertile of serum phosphate had significantly higher body mass index (BMI) (P < .001), lower temperature (P < .001), lower heart rate (P < .001), lower mean arterial blood pressure (P = .011), higher creatinine (P < .001), higher potassium (P < .001), higher sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) (P < .001), higher acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE IV) (P < .001), and higher ICU mortality (P < .001). Also, patients with higher serum phosphate levels were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (RRT) (P < .001) and vasoactive drugs (P = .003) than those in the lower serum phosphate group. Such differences were also observed for age (P = .021), calcium level (P = .023), sodium level (P = .039), hypertension (P = .014), coronary artery disease (P = .004), diabetes (P = .017), and chronic kidney disease (P < .001). No significant differences were observed for gender, respiration rate, SpO2, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelets, cirrhosis, stroke, ventilation, LOS in ICU, and LOS in hospital (P > .05).

A univariate logistic regression analysis performed to determine the relationship between serum phosphate level and risk of in-hospital mortality revealed that higher serum phosphate level correlated with increased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.46; P < .001).

Li et al. posited that several mechanisms may explain increased mortality at higher serum phosphate levels in AECOPD patients: increased serum phosphate induces vascular calcification and endothelial dysfunction, leading to organ dysfunction; hyperphosphatemia causes oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and inflammation, all of which are involved in the pathogenesis of AECOPD, and a higher phosphate diet exacerbates aging and lung emphysema phenotypes; restriction of phosphate intake and absorption relieves these phenotypes and alveolar destruction, which might contribute to the development of AECOPD.

Li et al. concluded: “Reducing serum phosphate levels may be a therapeutic strategy to improve prognosis of AECOPD patients.”

“This large retrospective analysis on eICU database in the U.S. revealed elevated serum phosphate levels with increased in-hospital mortality among patients experiencing acute exacerbation of COPD,” commented Dharani Narendra, MD, assistant professor in medicine, at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “This association, previously observed in various chronic conditions including COPD, particularly in men, is now noted to apply to both genders, irrespective of chronic kidney disease. The study also hints at potential mechanisms for elevated phosphate levels, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell apoptosis in AECOPD, as well as a high-phosphate diet.”

She told this news organization also, “It remains imperative to ascertain whether treating hyperphosphatemia or implementing dietary phosphate restrictions can reduce mortality or prevent AECOPD episodes. These demand additional clinical trials to establish a definitive cause-and-effect relationship and to guide potential treatment and prevention strategies.”

Noting study limitations, Li et al. stated that many variables, such as smoking, exacerbation frequency, severity, PH, PaO2, PaCO2, and lactate, were not included in this study owing to more than 20% missing values.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department, Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation, and Special fund for rehabilitation medicine of the National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders Clinical Research Fund. The authors declare no competing interests.

found significantly higher in-hospital mortality among AECOPD patients with high serum phosphate levels. The finding, according to Siqi Li et al. in a preproof HELIYON article, suggests that hyperphosphatemia may be a high-risk factor for AECOPD-related in-hospital mortality.

Phosphorus is key to several physiological processes, among them energy metabolism, bone mineralization, membrane transport, and intracellular signaling. Li et al. pointed out that in patients with multiple diseases, hyperphosphatemia is associated with increased mortality. In the development of COPD specifically, acute exacerbations have been shown in several recent studies to be an important adverse event conferring heightened mortality risk. Despite many efforts, AECOPD mortality rates remain high, making identification of potential factors, Li et al. stated, crucial for improving outcomes in high-risk patients.

The electronic Intensive Care Unit Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD) holds data associated with over 200,000 patient stays, providing a large sample size for research studies. To determine the relationship between serum phosphate and in-hospital mortality in AECOPD patients, investigators analyzed data from a total of 1,199 AECOPD patients (mean age, 68 years; ~55% female) enrolled in eICU-CRD and divided them into three groups according to serum phosphate level tertiles: lowest tertile (serum phosphate ≤ 3.0 mg/dL, n = 445), median tertile (serum phosphate > 3.0 mg/dL and ≤ 4.0 mg/dL, n = 378), and highest tertile (serum phosphate > 4.0 mg/dL, n = 376). The Li et al. study’s primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality, defined as survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included length of stay (LOS) in the intensive care unit (ICU), LOS in the hospital, and all-cause ICU mortality.

The Li et al. analysis of patient characteristics showed that patients in the highest tertile of serum phosphate had significantly higher body mass index (BMI) (P < .001), lower temperature (P < .001), lower heart rate (P < .001), lower mean arterial blood pressure (P = .011), higher creatinine (P < .001), higher potassium (P < .001), higher sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) (P < .001), higher acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE IV) (P < .001), and higher ICU mortality (P < .001). Also, patients with higher serum phosphate levels were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (RRT) (P < .001) and vasoactive drugs (P = .003) than those in the lower serum phosphate group. Such differences were also observed for age (P = .021), calcium level (P = .023), sodium level (P = .039), hypertension (P = .014), coronary artery disease (P = .004), diabetes (P = .017), and chronic kidney disease (P < .001). No significant differences were observed for gender, respiration rate, SpO2, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelets, cirrhosis, stroke, ventilation, LOS in ICU, and LOS in hospital (P > .05).

A univariate logistic regression analysis performed to determine the relationship between serum phosphate level and risk of in-hospital mortality revealed that higher serum phosphate level correlated with increased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.46; P < .001).

Li et al. posited that several mechanisms may explain increased mortality at higher serum phosphate levels in AECOPD patients: increased serum phosphate induces vascular calcification and endothelial dysfunction, leading to organ dysfunction; hyperphosphatemia causes oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and inflammation, all of which are involved in the pathogenesis of AECOPD, and a higher phosphate diet exacerbates aging and lung emphysema phenotypes; restriction of phosphate intake and absorption relieves these phenotypes and alveolar destruction, which might contribute to the development of AECOPD.

Li et al. concluded: “Reducing serum phosphate levels may be a therapeutic strategy to improve prognosis of AECOPD patients.”

“This large retrospective analysis on eICU database in the U.S. revealed elevated serum phosphate levels with increased in-hospital mortality among patients experiencing acute exacerbation of COPD,” commented Dharani Narendra, MD, assistant professor in medicine, at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “This association, previously observed in various chronic conditions including COPD, particularly in men, is now noted to apply to both genders, irrespective of chronic kidney disease. The study also hints at potential mechanisms for elevated phosphate levels, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell apoptosis in AECOPD, as well as a high-phosphate diet.”

She told this news organization also, “It remains imperative to ascertain whether treating hyperphosphatemia or implementing dietary phosphate restrictions can reduce mortality or prevent AECOPD episodes. These demand additional clinical trials to establish a definitive cause-and-effect relationship and to guide potential treatment and prevention strategies.”

Noting study limitations, Li et al. stated that many variables, such as smoking, exacerbation frequency, severity, PH, PaO2, PaCO2, and lactate, were not included in this study owing to more than 20% missing values.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department, Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation, and Special fund for rehabilitation medicine of the National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders Clinical Research Fund. The authors declare no competing interests.

found significantly higher in-hospital mortality among AECOPD patients with high serum phosphate levels. The finding, according to Siqi Li et al. in a preproof HELIYON article, suggests that hyperphosphatemia may be a high-risk factor for AECOPD-related in-hospital mortality.

Phosphorus is key to several physiological processes, among them energy metabolism, bone mineralization, membrane transport, and intracellular signaling. Li et al. pointed out that in patients with multiple diseases, hyperphosphatemia is associated with increased mortality. In the development of COPD specifically, acute exacerbations have been shown in several recent studies to be an important adverse event conferring heightened mortality risk. Despite many efforts, AECOPD mortality rates remain high, making identification of potential factors, Li et al. stated, crucial for improving outcomes in high-risk patients.

The electronic Intensive Care Unit Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD) holds data associated with over 200,000 patient stays, providing a large sample size for research studies. To determine the relationship between serum phosphate and in-hospital mortality in AECOPD patients, investigators analyzed data from a total of 1,199 AECOPD patients (mean age, 68 years; ~55% female) enrolled in eICU-CRD and divided them into three groups according to serum phosphate level tertiles: lowest tertile (serum phosphate ≤ 3.0 mg/dL, n = 445), median tertile (serum phosphate > 3.0 mg/dL and ≤ 4.0 mg/dL, n = 378), and highest tertile (serum phosphate > 4.0 mg/dL, n = 376). The Li et al. study’s primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality, defined as survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included length of stay (LOS) in the intensive care unit (ICU), LOS in the hospital, and all-cause ICU mortality.

The Li et al. analysis of patient characteristics showed that patients in the highest tertile of serum phosphate had significantly higher body mass index (BMI) (P < .001), lower temperature (P < .001), lower heart rate (P < .001), lower mean arterial blood pressure (P = .011), higher creatinine (P < .001), higher potassium (P < .001), higher sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) (P < .001), higher acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE IV) (P < .001), and higher ICU mortality (P < .001). Also, patients with higher serum phosphate levels were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (RRT) (P < .001) and vasoactive drugs (P = .003) than those in the lower serum phosphate group. Such differences were also observed for age (P = .021), calcium level (P = .023), sodium level (P = .039), hypertension (P = .014), coronary artery disease (P = .004), diabetes (P = .017), and chronic kidney disease (P < .001). No significant differences were observed for gender, respiration rate, SpO2, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelets, cirrhosis, stroke, ventilation, LOS in ICU, and LOS in hospital (P > .05).

A univariate logistic regression analysis performed to determine the relationship between serum phosphate level and risk of in-hospital mortality revealed that higher serum phosphate level correlated with increased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.46; P < .001).

Li et al. posited that several mechanisms may explain increased mortality at higher serum phosphate levels in AECOPD patients: increased serum phosphate induces vascular calcification and endothelial dysfunction, leading to organ dysfunction; hyperphosphatemia causes oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and inflammation, all of which are involved in the pathogenesis of AECOPD, and a higher phosphate diet exacerbates aging and lung emphysema phenotypes; restriction of phosphate intake and absorption relieves these phenotypes and alveolar destruction, which might contribute to the development of AECOPD.

Li et al. concluded: “Reducing serum phosphate levels may be a therapeutic strategy to improve prognosis of AECOPD patients.”

“This large retrospective analysis on eICU database in the U.S. revealed elevated serum phosphate levels with increased in-hospital mortality among patients experiencing acute exacerbation of COPD,” commented Dharani Narendra, MD, assistant professor in medicine, at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “This association, previously observed in various chronic conditions including COPD, particularly in men, is now noted to apply to both genders, irrespective of chronic kidney disease. The study also hints at potential mechanisms for elevated phosphate levels, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell apoptosis in AECOPD, as well as a high-phosphate diet.”

She told this news organization also, “It remains imperative to ascertain whether treating hyperphosphatemia or implementing dietary phosphate restrictions can reduce mortality or prevent AECOPD episodes. These demand additional clinical trials to establish a definitive cause-and-effect relationship and to guide potential treatment and prevention strategies.”

Noting study limitations, Li et al. stated that many variables, such as smoking, exacerbation frequency, severity, PH, PaO2, PaCO2, and lactate, were not included in this study owing to more than 20% missing values.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department, Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation, and Special fund for rehabilitation medicine of the National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders Clinical Research Fund. The authors declare no competing interests.

FROM HELIYON

Home oxygen therapy: What does the data show?

Inhalers, nebulizers, antibiotics, and steroids – these are some of the most common tools in our pulmonary arsenal that we deploy on a daily basis. But, there is no treatment more fundamental to a pulmonary practitioner than oxygen. So how is it that something that naturally occurs and comprises 21% of ambient air has become so medicalized?

It is difficult (perhaps impossible) to find a pulmonologist or a hospitalist who has not included the phrase “obtain ambulatory saturation to qualify the patient for home oxygen” in at least one of their progress notes on a daily basis. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most common reason for the prescription of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), a large industry tightly regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

The evidence for the use of LTOT in patients with COPD dates back to two seminal papers published in 1980 and 1981. The British Medical Research Council Working Party conducted the BMRC trial, in which 87 patients with a Pa

Another study published around the same time, the Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease (NOTT) trial (Ann Intern Med. 1980;93[3]:391-8) directly compared continuous 24-hour to nocturnal home oxygen therapy in patients with COPD and severe hypoxemia with a Pa

Afterward, it became universally accepted dogma that patients with COPD and severe hypoxemia stood to substantially benefit from LTOT. For years, it was the only therapy associated with a mortality reduction. The LOTT study (Albert RK, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[17]:1617-27) included 768 patients with stable COPD and a resting or nocturnal Sp

The INOX (Lacasse Y, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383[12]:1129-38) trial, in which 243 patients with oxygen saturation less than 90% for at least 30% of the night were assigned to receive nocturnal vs sham oxygen, found similar results. There was no difference in the composite outcome of all-cause mortality and progression to 24-7 oxygen requirement (according to the criteria originally defined by NOTT). A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis including six studies designed to assess the role of LTOT in patients with COPD and moderate desaturation, including LOTT and INOX, found no benefit to providing LTOT (Lacasse Y, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10[11]:1029-37).

Based on these studies, a resting Sp

COPD management has changed significantly in the 40 years since NOTT was published. In the early 1980s, standard of care included an inhaled beta-agonist and oral theophylline. We now prescribe a regimen of modern-day inhaler combinations, which can lead to a mortality benefit in the correct population. Additionally, rates of smoking are markedly lower now than they were in 1980. In the Minnesota Heart Survey, the prevalence of being an ever-smoking man or woman in 1980 compared with 2009 dropped from 71.6% and 54.7% to 44.2% and 39.6%, respectively (Filion KB, et al. Am J Public Health. 2012;102[4]:705-13). Treatment of common comorbid conditions has also dramatically improved.

A report containing all fee-for-service data published in 2021 by CMS reported oxygen therapy accounted for 9.8% of all DME costs covered by CMS and totaled approximately $800,000,000 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. FFS Data. 2021. This represents a significant financial burden to our health system and government.

Two of the eligible groups per CMS (those with isolated ambulatory or nocturnal hypoxemia) do not benefit from LTOT in RCTs. The other two groups are eligible based on trial data from a small number of patients who were studied more than 40 years ago. These facts raise serious questions about the cost-efficacy of LTOT.

So where does this leave us?

There are significant barriers to repeating large randomized oxygen trials. Due to broad inclusion criteria for LTOT by CMS, there are undoubtedly many people prescribed LTOT for whom there is minimal to no benefit. Patients often feel restricted in their mobility and may feel isolated being tethered to medical equipment. It is good practice to think about LTOT the same way we do any other therapy we provide - as a medicine with associated risks, benefits, and costs.

Despite its ubiquity, oxygen remains an important therapeutic tool. Still, choosing wisely means recognizing that not all patients who qualify for LTOT by CMS criteria will benefit.

Drs. Kreisel and Sonti are with the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC.

Inhalers, nebulizers, antibiotics, and steroids – these are some of the most common tools in our pulmonary arsenal that we deploy on a daily basis. But, there is no treatment more fundamental to a pulmonary practitioner than oxygen. So how is it that something that naturally occurs and comprises 21% of ambient air has become so medicalized?

It is difficult (perhaps impossible) to find a pulmonologist or a hospitalist who has not included the phrase “obtain ambulatory saturation to qualify the patient for home oxygen” in at least one of their progress notes on a daily basis. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most common reason for the prescription of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), a large industry tightly regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

The evidence for the use of LTOT in patients with COPD dates back to two seminal papers published in 1980 and 1981. The British Medical Research Council Working Party conducted the BMRC trial, in which 87 patients with a Pa

Another study published around the same time, the Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease (NOTT) trial (Ann Intern Med. 1980;93[3]:391-8) directly compared continuous 24-hour to nocturnal home oxygen therapy in patients with COPD and severe hypoxemia with a Pa

Afterward, it became universally accepted dogma that patients with COPD and severe hypoxemia stood to substantially benefit from LTOT. For years, it was the only therapy associated with a mortality reduction. The LOTT study (Albert RK, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[17]:1617-27) included 768 patients with stable COPD and a resting or nocturnal Sp

The INOX (Lacasse Y, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383[12]:1129-38) trial, in which 243 patients with oxygen saturation less than 90% for at least 30% of the night were assigned to receive nocturnal vs sham oxygen, found similar results. There was no difference in the composite outcome of all-cause mortality and progression to 24-7 oxygen requirement (according to the criteria originally defined by NOTT). A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis including six studies designed to assess the role of LTOT in patients with COPD and moderate desaturation, including LOTT and INOX, found no benefit to providing LTOT (Lacasse Y, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10[11]:1029-37).

Based on these studies, a resting Sp

COPD management has changed significantly in the 40 years since NOTT was published. In the early 1980s, standard of care included an inhaled beta-agonist and oral theophylline. We now prescribe a regimen of modern-day inhaler combinations, which can lead to a mortality benefit in the correct population. Additionally, rates of smoking are markedly lower now than they were in 1980. In the Minnesota Heart Survey, the prevalence of being an ever-smoking man or woman in 1980 compared with 2009 dropped from 71.6% and 54.7% to 44.2% and 39.6%, respectively (Filion KB, et al. Am J Public Health. 2012;102[4]:705-13). Treatment of common comorbid conditions has also dramatically improved.

A report containing all fee-for-service data published in 2021 by CMS reported oxygen therapy accounted for 9.8% of all DME costs covered by CMS and totaled approximately $800,000,000 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. FFS Data. 2021. This represents a significant financial burden to our health system and government.

Two of the eligible groups per CMS (those with isolated ambulatory or nocturnal hypoxemia) do not benefit from LTOT in RCTs. The other two groups are eligible based on trial data from a small number of patients who were studied more than 40 years ago. These facts raise serious questions about the cost-efficacy of LTOT.

So where does this leave us?

There are significant barriers to repeating large randomized oxygen trials. Due to broad inclusion criteria for LTOT by CMS, there are undoubtedly many people prescribed LTOT for whom there is minimal to no benefit. Patients often feel restricted in their mobility and may feel isolated being tethered to medical equipment. It is good practice to think about LTOT the same way we do any other therapy we provide - as a medicine with associated risks, benefits, and costs.

Despite its ubiquity, oxygen remains an important therapeutic tool. Still, choosing wisely means recognizing that not all patients who qualify for LTOT by CMS criteria will benefit.

Drs. Kreisel and Sonti are with the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC.

Inhalers, nebulizers, antibiotics, and steroids – these are some of the most common tools in our pulmonary arsenal that we deploy on a daily basis. But, there is no treatment more fundamental to a pulmonary practitioner than oxygen. So how is it that something that naturally occurs and comprises 21% of ambient air has become so medicalized?

It is difficult (perhaps impossible) to find a pulmonologist or a hospitalist who has not included the phrase “obtain ambulatory saturation to qualify the patient for home oxygen” in at least one of their progress notes on a daily basis. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most common reason for the prescription of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), a large industry tightly regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

The evidence for the use of LTOT in patients with COPD dates back to two seminal papers published in 1980 and 1981. The British Medical Research Council Working Party conducted the BMRC trial, in which 87 patients with a Pa

Another study published around the same time, the Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease (NOTT) trial (Ann Intern Med. 1980;93[3]:391-8) directly compared continuous 24-hour to nocturnal home oxygen therapy in patients with COPD and severe hypoxemia with a Pa

Afterward, it became universally accepted dogma that patients with COPD and severe hypoxemia stood to substantially benefit from LTOT. For years, it was the only therapy associated with a mortality reduction. The LOTT study (Albert RK, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[17]:1617-27) included 768 patients with stable COPD and a resting or nocturnal Sp

The INOX (Lacasse Y, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383[12]:1129-38) trial, in which 243 patients with oxygen saturation less than 90% for at least 30% of the night were assigned to receive nocturnal vs sham oxygen, found similar results. There was no difference in the composite outcome of all-cause mortality and progression to 24-7 oxygen requirement (according to the criteria originally defined by NOTT). A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis including six studies designed to assess the role of LTOT in patients with COPD and moderate desaturation, including LOTT and INOX, found no benefit to providing LTOT (Lacasse Y, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10[11]:1029-37).

Based on these studies, a resting Sp

COPD management has changed significantly in the 40 years since NOTT was published. In the early 1980s, standard of care included an inhaled beta-agonist and oral theophylline. We now prescribe a regimen of modern-day inhaler combinations, which can lead to a mortality benefit in the correct population. Additionally, rates of smoking are markedly lower now than they were in 1980. In the Minnesota Heart Survey, the prevalence of being an ever-smoking man or woman in 1980 compared with 2009 dropped from 71.6% and 54.7% to 44.2% and 39.6%, respectively (Filion KB, et al. Am J Public Health. 2012;102[4]:705-13). Treatment of common comorbid conditions has also dramatically improved.

A report containing all fee-for-service data published in 2021 by CMS reported oxygen therapy accounted for 9.8% of all DME costs covered by CMS and totaled approximately $800,000,000 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. FFS Data. 2021. This represents a significant financial burden to our health system and government.

Two of the eligible groups per CMS (those with isolated ambulatory or nocturnal hypoxemia) do not benefit from LTOT in RCTs. The other two groups are eligible based on trial data from a small number of patients who were studied more than 40 years ago. These facts raise serious questions about the cost-efficacy of LTOT.

So where does this leave us?

There are significant barriers to repeating large randomized oxygen trials. Due to broad inclusion criteria for LTOT by CMS, there are undoubtedly many people prescribed LTOT for whom there is minimal to no benefit. Patients often feel restricted in their mobility and may feel isolated being tethered to medical equipment. It is good practice to think about LTOT the same way we do any other therapy we provide - as a medicine with associated risks, benefits, and costs.

Despite its ubiquity, oxygen remains an important therapeutic tool. Still, choosing wisely means recognizing that not all patients who qualify for LTOT by CMS criteria will benefit.

Drs. Kreisel and Sonti are with the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC.

Short, long-lasting bronchodilators similar for exacerbated COPD

HONOLULU – in safety and efficacy to a short-acting combination of albuterol and ipratropium.

The 2023 Gold Report on prevention, management, and diagnosis of COPD recommended switching to long-acting bronchodilators despite a lack of clinical evidence showing safety in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation, according to Rajiv Dhand, MD, who presented the new study at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

“We wanted to establish the safety, because long-acting agents are approved only for use in nonhospitalized patients. We established that it was safe and that it was comparably effective, but you could give 30% lower doses. Patients don’t have to be woken up to get the medication, and there’s a better chance that all the doses will be administered to these patients. So I think that it provides convenience with similar efficacy and safety,” said Dr. Dhand, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

The researchers randomized 60 patients to receive nebulized albuterol (2.5 mg) and ipratropium (0.5 mg) every 6 hours (short-acting group) or nebulized formoterol (20 mcg) every 12 hours and revefenacin (175 mcg) every 24 hours (long-acting group). The mean age was 63.2 years, 58.3% were male, and 65% were current smokers.

The median decrease between day 1 and day 3 in the Modified Borg Dyspnea score was 4.0 in the long-acting group (P < .001), and 2.0 in the short-acting group, though the latter was not statistically significant (P = .134). Both groups had a decrease in supplemental oxygen requirement, with no difference between the two groups. There was also no difference in the number of respiratory visits for rescue therapy.

Respiratory therapists in the audience welcomed the new evidence. “As a respiratory therapist, I feel that we should move away from giving good short acting [therapies] ... the new guidelines state that we should move away from them, but I think that physicians in general have not gone that way. The way that we’re working, giving short acting every four hours – I don’t see that it’s a benefit to our patients,” said Sharon Armstead, who attended the session and was asked to comment on the study. She is a respiratory therapist at Ascension Health and an instructor at Concordia University, Austin, Texas. Ms. Armstead has asthma, and has first-hand experience as a patient when respiratory therapists are unable to attend to the patient every 4 hours.

She suggested that continued use of short-acting therapies may be due to inertia. “It’s easier [for a physician] to click a button on [a computer screen] than to actually slow down and write the order. If we need a rescue, then we’ll call for a rescue,” Ms. Armstead said.

She anticipates that long-acting therapies will ultimately lead to better outcomes because they will increase the time that respiratory therapists can spend with patients. “That’s what we really want to do. We want to spend time with our patients and stay there and watch our patients. But if you’re just telling us to [administer a therapy] every 4 hours, it’s not really giving the patient what they need.”

Specifically, there were concerns about cardiovascular safety, but the researchers found no between-group differences.

Asked for comment, session co-moderator Brittany Duchene, MD remarked: “It’s super interesting, but I worry about the cost. From a practical perspective, it’s challenging to get those drugs placed on an outpatient basis. They are very expensive, and they’re newer [drugs], but I think overall it’s good to give less,” said Dr. Duchene, a pulmonary critical care physician at Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital, St. Johnsbury.

A potential concern raised by one audience member is that some patients are used to frequent treatment and may grow anxious with less frequent therapy. “I think we just need some reeducation that this is like a long-acting medicine. It also decreases the burden on our respiratory therapists, which is very good,” said Dr. Duchene.

The study was funded by Mylan/Theravance Biopharma. Dr. Dhand has received research support from Theravance, Mylan, and Viatris. He has received honoraria from Teva and UpToDate. Ms. Armstead and Dr. Duchene have no relevant financial disclosures.

HONOLULU – in safety and efficacy to a short-acting combination of albuterol and ipratropium.

The 2023 Gold Report on prevention, management, and diagnosis of COPD recommended switching to long-acting bronchodilators despite a lack of clinical evidence showing safety in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation, according to Rajiv Dhand, MD, who presented the new study at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

“We wanted to establish the safety, because long-acting agents are approved only for use in nonhospitalized patients. We established that it was safe and that it was comparably effective, but you could give 30% lower doses. Patients don’t have to be woken up to get the medication, and there’s a better chance that all the doses will be administered to these patients. So I think that it provides convenience with similar efficacy and safety,” said Dr. Dhand, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

The researchers randomized 60 patients to receive nebulized albuterol (2.5 mg) and ipratropium (0.5 mg) every 6 hours (short-acting group) or nebulized formoterol (20 mcg) every 12 hours and revefenacin (175 mcg) every 24 hours (long-acting group). The mean age was 63.2 years, 58.3% were male, and 65% were current smokers.

The median decrease between day 1 and day 3 in the Modified Borg Dyspnea score was 4.0 in the long-acting group (P < .001), and 2.0 in the short-acting group, though the latter was not statistically significant (P = .134). Both groups had a decrease in supplemental oxygen requirement, with no difference between the two groups. There was also no difference in the number of respiratory visits for rescue therapy.

Respiratory therapists in the audience welcomed the new evidence. “As a respiratory therapist, I feel that we should move away from giving good short acting [therapies] ... the new guidelines state that we should move away from them, but I think that physicians in general have not gone that way. The way that we’re working, giving short acting every four hours – I don’t see that it’s a benefit to our patients,” said Sharon Armstead, who attended the session and was asked to comment on the study. She is a respiratory therapist at Ascension Health and an instructor at Concordia University, Austin, Texas. Ms. Armstead has asthma, and has first-hand experience as a patient when respiratory therapists are unable to attend to the patient every 4 hours.

She suggested that continued use of short-acting therapies may be due to inertia. “It’s easier [for a physician] to click a button on [a computer screen] than to actually slow down and write the order. If we need a rescue, then we’ll call for a rescue,” Ms. Armstead said.

She anticipates that long-acting therapies will ultimately lead to better outcomes because they will increase the time that respiratory therapists can spend with patients. “That’s what we really want to do. We want to spend time with our patients and stay there and watch our patients. But if you’re just telling us to [administer a therapy] every 4 hours, it’s not really giving the patient what they need.”

Specifically, there were concerns about cardiovascular safety, but the researchers found no between-group differences.

Asked for comment, session co-moderator Brittany Duchene, MD remarked: “It’s super interesting, but I worry about the cost. From a practical perspective, it’s challenging to get those drugs placed on an outpatient basis. They are very expensive, and they’re newer [drugs], but I think overall it’s good to give less,” said Dr. Duchene, a pulmonary critical care physician at Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital, St. Johnsbury.

A potential concern raised by one audience member is that some patients are used to frequent treatment and may grow anxious with less frequent therapy. “I think we just need some reeducation that this is like a long-acting medicine. It also decreases the burden on our respiratory therapists, which is very good,” said Dr. Duchene.

The study was funded by Mylan/Theravance Biopharma. Dr. Dhand has received research support from Theravance, Mylan, and Viatris. He has received honoraria from Teva and UpToDate. Ms. Armstead and Dr. Duchene have no relevant financial disclosures.

HONOLULU – in safety and efficacy to a short-acting combination of albuterol and ipratropium.

The 2023 Gold Report on prevention, management, and diagnosis of COPD recommended switching to long-acting bronchodilators despite a lack of clinical evidence showing safety in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation, according to Rajiv Dhand, MD, who presented the new study at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

“We wanted to establish the safety, because long-acting agents are approved only for use in nonhospitalized patients. We established that it was safe and that it was comparably effective, but you could give 30% lower doses. Patients don’t have to be woken up to get the medication, and there’s a better chance that all the doses will be administered to these patients. So I think that it provides convenience with similar efficacy and safety,” said Dr. Dhand, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

The researchers randomized 60 patients to receive nebulized albuterol (2.5 mg) and ipratropium (0.5 mg) every 6 hours (short-acting group) or nebulized formoterol (20 mcg) every 12 hours and revefenacin (175 mcg) every 24 hours (long-acting group). The mean age was 63.2 years, 58.3% were male, and 65% were current smokers.

The median decrease between day 1 and day 3 in the Modified Borg Dyspnea score was 4.0 in the long-acting group (P < .001), and 2.0 in the short-acting group, though the latter was not statistically significant (P = .134). Both groups had a decrease in supplemental oxygen requirement, with no difference between the two groups. There was also no difference in the number of respiratory visits for rescue therapy.

Respiratory therapists in the audience welcomed the new evidence. “As a respiratory therapist, I feel that we should move away from giving good short acting [therapies] ... the new guidelines state that we should move away from them, but I think that physicians in general have not gone that way. The way that we’re working, giving short acting every four hours – I don’t see that it’s a benefit to our patients,” said Sharon Armstead, who attended the session and was asked to comment on the study. She is a respiratory therapist at Ascension Health and an instructor at Concordia University, Austin, Texas. Ms. Armstead has asthma, and has first-hand experience as a patient when respiratory therapists are unable to attend to the patient every 4 hours.

She suggested that continued use of short-acting therapies may be due to inertia. “It’s easier [for a physician] to click a button on [a computer screen] than to actually slow down and write the order. If we need a rescue, then we’ll call for a rescue,” Ms. Armstead said.

She anticipates that long-acting therapies will ultimately lead to better outcomes because they will increase the time that respiratory therapists can spend with patients. “That’s what we really want to do. We want to spend time with our patients and stay there and watch our patients. But if you’re just telling us to [administer a therapy] every 4 hours, it’s not really giving the patient what they need.”

Specifically, there were concerns about cardiovascular safety, but the researchers found no between-group differences.

Asked for comment, session co-moderator Brittany Duchene, MD remarked: “It’s super interesting, but I worry about the cost. From a practical perspective, it’s challenging to get those drugs placed on an outpatient basis. They are very expensive, and they’re newer [drugs], but I think overall it’s good to give less,” said Dr. Duchene, a pulmonary critical care physician at Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital, St. Johnsbury.

A potential concern raised by one audience member is that some patients are used to frequent treatment and may grow anxious with less frequent therapy. “I think we just need some reeducation that this is like a long-acting medicine. It also decreases the burden on our respiratory therapists, which is very good,” said Dr. Duchene.

The study was funded by Mylan/Theravance Biopharma. Dr. Dhand has received research support from Theravance, Mylan, and Viatris. He has received honoraria from Teva and UpToDate. Ms. Armstead and Dr. Duchene have no relevant financial disclosures.

AT CHEST 2023

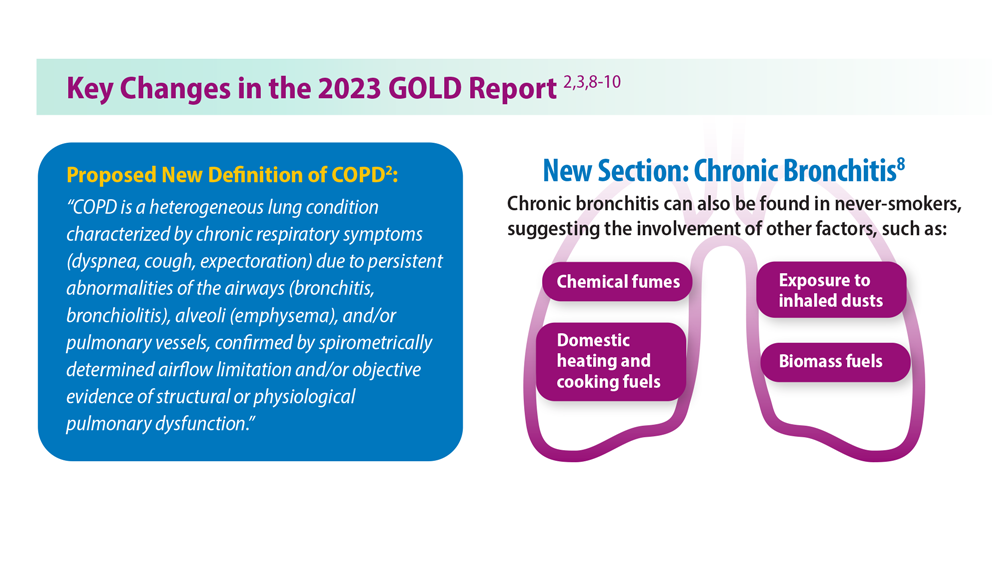

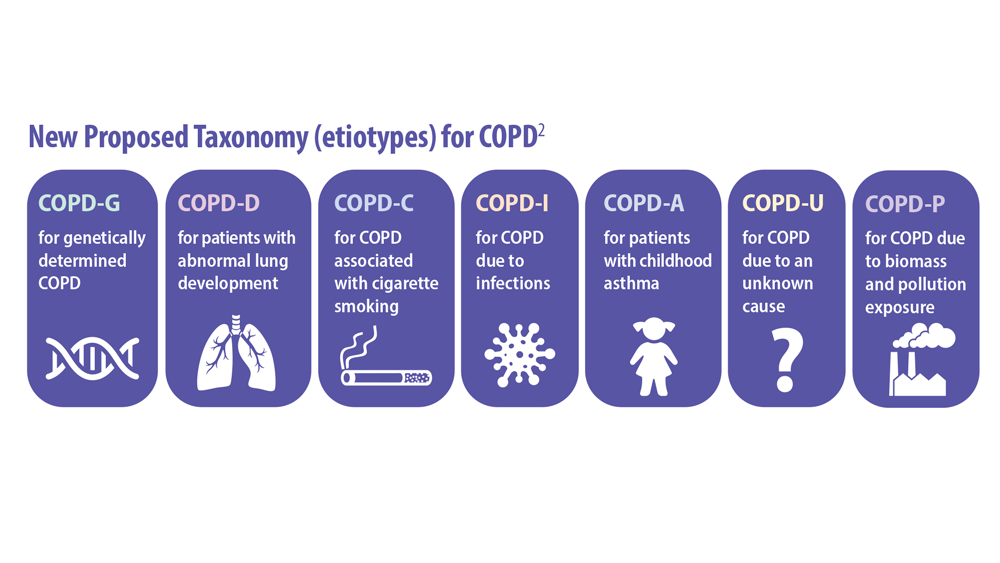

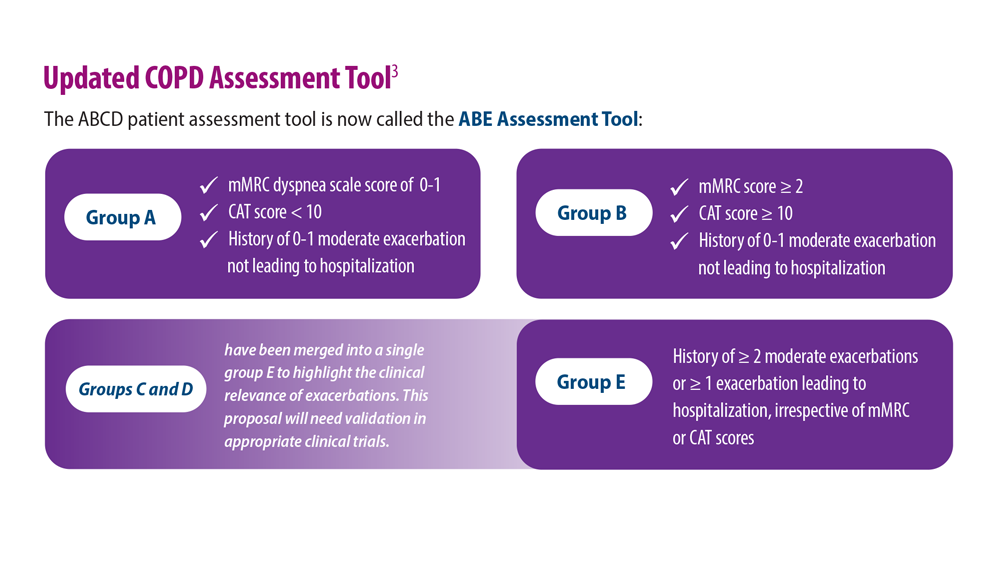

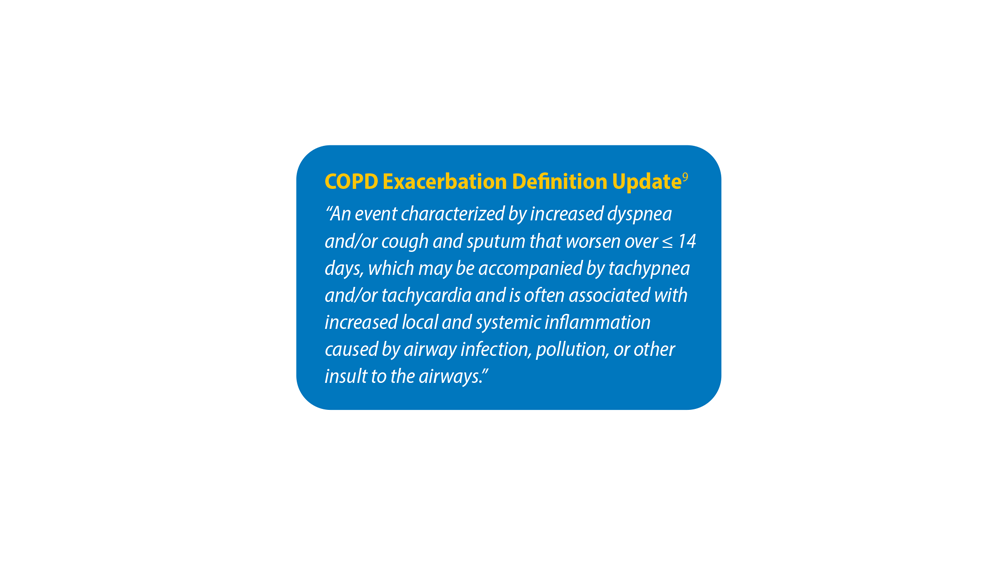

Updated Guidelines for COPD Management: 2023 GOLD Strategy Report

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Published 2023. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

- Celli B et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(11):1317. doi:10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP

- Han M et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):43-50. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70044-9

- Klijn SL et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):24. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0022-1

- Chan AH et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):335-349.e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.024

- Brusselle G et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207-2217. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91694

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733-743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9

- Trupin L et al. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462-469. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00094203

- Celli BR et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(11):1251-1258. doi:10.1164/rccm.202108-1819PP

- Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165-1185. doi:10.1183/09031936.00128008

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Published 2023. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

- Celli B et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(11):1317. doi:10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP

- Han M et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):43-50. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70044-9

- Klijn SL et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):24. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0022-1

- Chan AH et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):335-349.e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.024

- Brusselle G et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207-2217. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91694

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733-743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9

- Trupin L et al. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462-469. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00094203

- Celli BR et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(11):1251-1258. doi:10.1164/rccm.202108-1819PP

- Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165-1185. doi:10.1183/09031936.00128008

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Published 2023. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

- Celli B et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(11):1317. doi:10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP

- Han M et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):43-50. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70044-9

- Klijn SL et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):24. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0022-1

- Chan AH et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):335-349.e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.024

- Brusselle G et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207-2217. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91694

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733-743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9

- Trupin L et al. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462-469. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00094203

- Celli BR et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(11):1251-1258. doi:10.1164/rccm.202108-1819PP

- Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165-1185. doi:10.1183/09031936.00128008

FDA warns AstraZeneca over ‘misleading claims’ about COPD drug

Promotional materials for the drug Breztri (budesonide/formoterol fumarate/glycopyrrolate inhaled) suggest that the drug has a positive effect on all-cause mortality for COPD patients, but the referenced clinical trial does not support that claim, the FDA letter states.

The FDA issued the warning letter on Aug. 4 and published the letter online on Aug. 15.

The sales aid highlights a 49% observed relative difference in time to all-cause mortality (ACM) over 1 year between Breztri and long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting beta agonist (LAMA/LABA) inhalers.

Because of “statistical testing hierarchy failure” as well as confounding factors such as the removal of patients from inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) prior to entering the treatment arm of the trial, “no conclusions about the effect of Breztri on ACM can be drawn from the [clinical] trial,” the FDA wrote. “To date, no drug has been shown to improve ACM in COPD.”

The Breztri sales aid also states that there was a 20% reduction of severe exacerbations in patients using Breztri compared with patients using ICS/LABA. However, in the cited clinical trial, “the reduction in severe exacerbations was not statistically significant for patients treated with Breztri relative to comparator groups,” according to the FDA.

AstraZeneca has 15 working days from the receipt of the letter to respond in writing with “any plan for discontinuing use of such communications, or for ceasing distribution of Breztri,” the agency wrote.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Promotional materials for the drug Breztri (budesonide/formoterol fumarate/glycopyrrolate inhaled) suggest that the drug has a positive effect on all-cause mortality for COPD patients, but the referenced clinical trial does not support that claim, the FDA letter states.

The FDA issued the warning letter on Aug. 4 and published the letter online on Aug. 15.

The sales aid highlights a 49% observed relative difference in time to all-cause mortality (ACM) over 1 year between Breztri and long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting beta agonist (LAMA/LABA) inhalers.

Because of “statistical testing hierarchy failure” as well as confounding factors such as the removal of patients from inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) prior to entering the treatment arm of the trial, “no conclusions about the effect of Breztri on ACM can be drawn from the [clinical] trial,” the FDA wrote. “To date, no drug has been shown to improve ACM in COPD.”

The Breztri sales aid also states that there was a 20% reduction of severe exacerbations in patients using Breztri compared with patients using ICS/LABA. However, in the cited clinical trial, “the reduction in severe exacerbations was not statistically significant for patients treated with Breztri relative to comparator groups,” according to the FDA.

AstraZeneca has 15 working days from the receipt of the letter to respond in writing with “any plan for discontinuing use of such communications, or for ceasing distribution of Breztri,” the agency wrote.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Promotional materials for the drug Breztri (budesonide/formoterol fumarate/glycopyrrolate inhaled) suggest that the drug has a positive effect on all-cause mortality for COPD patients, but the referenced clinical trial does not support that claim, the FDA letter states.

The FDA issued the warning letter on Aug. 4 and published the letter online on Aug. 15.

The sales aid highlights a 49% observed relative difference in time to all-cause mortality (ACM) over 1 year between Breztri and long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting beta agonist (LAMA/LABA) inhalers.

Because of “statistical testing hierarchy failure” as well as confounding factors such as the removal of patients from inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) prior to entering the treatment arm of the trial, “no conclusions about the effect of Breztri on ACM can be drawn from the [clinical] trial,” the FDA wrote. “To date, no drug has been shown to improve ACM in COPD.”

The Breztri sales aid also states that there was a 20% reduction of severe exacerbations in patients using Breztri compared with patients using ICS/LABA. However, in the cited clinical trial, “the reduction in severe exacerbations was not statistically significant for patients treated with Breztri relative to comparator groups,” according to the FDA.

AstraZeneca has 15 working days from the receipt of the letter to respond in writing with “any plan for discontinuing use of such communications, or for ceasing distribution of Breztri,” the agency wrote.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Generic inhalers for COPD support hold their own

Sometimes we get what we pay for. Other times we pay too much.

That’s the message of a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, which finds that a generic maintenance inhaler is as effective at managing symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) as a pricier branded alternative.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved Wixela Inhub (the combination corticosteroid/long-acting beta2 adrenergic agonist fluticasone-salmeterol; Viatris) as a generic dry powder inhaler for managing symptoms of COPD. This approval was based on evidence of the generic’s effectiveness against asthma, although COPD also was on the product label. The study authors compared Wixela’s effectiveness in controlling symptoms of COPD with that of the brand name inhaler Advair Diskus (fluticasone-salmeterol; GlaxoSmithKline), which uses the same active ingredients.

The result: “The generic looks to be as safe and effective as the brand name. I don’t see a clinical reason why one would ever need to get the brand name over the generic version,” said study author William Feldman, MD, DPhil, MPH, a health services researcher and pulmonologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

Same types of patients, different inhalers, same outcomes

Dr. Feldman and colleagues compared the medical records of 10,000 patients with COPD who began using the branded inhaler to the records of another 10,000 patients with COPD who opted for the generic alternative. Participants in the two groups were evenly matched by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, region, severity of COPD, and presence of other comorbidities, according to the researchers. Participants were all older than age 40, and the average age in both groups was 72 years.

The researchers looked for a difference in a first episode of a moderate exacerbation of COPD, defined as requiring a course of prednisone for 5-14 days. They also looked for cases of severe COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the year after people began using either the generic or brand name inhaler. And they looked for differences across 1 year in rates of hospitalization for pneumonia.

For none of those outcomes, however, did the type of inhaler appear to matter. Compared with the brand-name drug, using the generic was associated with nearly identical rates of moderate or severe COPD exacerbation (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.04. The same was true for the proportion of people who went to the hospital for pneumonia at least once (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.86-1.15).

“To get through the FDA as an interchangeable generic, the generic firms have to show that their product can be used in just the same way as the brand-name version,” Dr. Feldman said, which may explain why the generic and brand-name versions of the inhaler performed so similarly.

Dr. Feldman cautioned that the price savings for patients who opt for the generic over the branded product are hard to determine, given the vagaries of different insurance plans and potential rebates when using the branded project. As a general matter, having a single generic competitor will not lower costs much, Dr. Feldman noted, pointing to 2017 research from Harvard that found a profusion of generic competitors is needed to significantly lower health care costs.

“I don’t want to in any way underestimate the importance of getting that first generic onto the market, because it sets the stage for future generics,” Dr. Feldman said.

“There are very few generic options for patients with COPD,” said Surya Bhatt, MD, director of the Pulmonary Function and Exercise Physiology Lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Even the rescue inhalers that people with COPD use to manage acute episodes of the condition are usually branded at this time, Dr. Bhatt noted, with few generic options.*

“The results are quite compelling,” said Dr. Bhatt, who was not involved in the research. Although the trial was not randomized, he commended the researchers for stratifying participants in the two groups to be as comparable as possible.

Dr. Bhatt noted that the FDA’s 2019 approval – given that the agency requires bioequivalence studies between branded and generic products – was enough to cause him to begin prescribing the generic inhaler. The fact that this approval was based on asthma but not also COPD is not a concern.

“There are so many similarities between asthma, COPD, and some obstructive lung diseases,” Dr. Bhatt noted.

In his experience, the only time someone with COPD continues using the branded inhaler – now that a potentially cheaper generic is available – is when their insurance plan makes their out-of-pocket cost minimal. Otherwise, brand loyalty does not exist.

“Patients are generally okay with being on a generic for inhalers, just because of the high cost,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The study was primarily supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Feldman reported funding from Arnold Ventures, the Commonwealth Fund, and the FDA, and consulting relationships with Alosa Health and Aetion. Dr. Bhatt reported no relevant financial relationships.

*Correction, 8/16/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized Dr. Bhatt's comments on the availability of generic options.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sometimes we get what we pay for. Other times we pay too much.

That’s the message of a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, which finds that a generic maintenance inhaler is as effective at managing symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) as a pricier branded alternative.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved Wixela Inhub (the combination corticosteroid/long-acting beta2 adrenergic agonist fluticasone-salmeterol; Viatris) as a generic dry powder inhaler for managing symptoms of COPD. This approval was based on evidence of the generic’s effectiveness against asthma, although COPD also was on the product label. The study authors compared Wixela’s effectiveness in controlling symptoms of COPD with that of the brand name inhaler Advair Diskus (fluticasone-salmeterol; GlaxoSmithKline), which uses the same active ingredients.

The result: “The generic looks to be as safe and effective as the brand name. I don’t see a clinical reason why one would ever need to get the brand name over the generic version,” said study author William Feldman, MD, DPhil, MPH, a health services researcher and pulmonologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

Same types of patients, different inhalers, same outcomes

Dr. Feldman and colleagues compared the medical records of 10,000 patients with COPD who began using the branded inhaler to the records of another 10,000 patients with COPD who opted for the generic alternative. Participants in the two groups were evenly matched by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, region, severity of COPD, and presence of other comorbidities, according to the researchers. Participants were all older than age 40, and the average age in both groups was 72 years.

The researchers looked for a difference in a first episode of a moderate exacerbation of COPD, defined as requiring a course of prednisone for 5-14 days. They also looked for cases of severe COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the year after people began using either the generic or brand name inhaler. And they looked for differences across 1 year in rates of hospitalization for pneumonia.

For none of those outcomes, however, did the type of inhaler appear to matter. Compared with the brand-name drug, using the generic was associated with nearly identical rates of moderate or severe COPD exacerbation (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.04. The same was true for the proportion of people who went to the hospital for pneumonia at least once (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.86-1.15).

“To get through the FDA as an interchangeable generic, the generic firms have to show that their product can be used in just the same way as the brand-name version,” Dr. Feldman said, which may explain why the generic and brand-name versions of the inhaler performed so similarly.

Dr. Feldman cautioned that the price savings for patients who opt for the generic over the branded product are hard to determine, given the vagaries of different insurance plans and potential rebates when using the branded project. As a general matter, having a single generic competitor will not lower costs much, Dr. Feldman noted, pointing to 2017 research from Harvard that found a profusion of generic competitors is needed to significantly lower health care costs.

“I don’t want to in any way underestimate the importance of getting that first generic onto the market, because it sets the stage for future generics,” Dr. Feldman said.

“There are very few generic options for patients with COPD,” said Surya Bhatt, MD, director of the Pulmonary Function and Exercise Physiology Lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Even the rescue inhalers that people with COPD use to manage acute episodes of the condition are usually branded at this time, Dr. Bhatt noted, with few generic options.*

“The results are quite compelling,” said Dr. Bhatt, who was not involved in the research. Although the trial was not randomized, he commended the researchers for stratifying participants in the two groups to be as comparable as possible.

Dr. Bhatt noted that the FDA’s 2019 approval – given that the agency requires bioequivalence studies between branded and generic products – was enough to cause him to begin prescribing the generic inhaler. The fact that this approval was based on asthma but not also COPD is not a concern.

“There are so many similarities between asthma, COPD, and some obstructive lung diseases,” Dr. Bhatt noted.

In his experience, the only time someone with COPD continues using the branded inhaler – now that a potentially cheaper generic is available – is when their insurance plan makes their out-of-pocket cost minimal. Otherwise, brand loyalty does not exist.

“Patients are generally okay with being on a generic for inhalers, just because of the high cost,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The study was primarily supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Feldman reported funding from Arnold Ventures, the Commonwealth Fund, and the FDA, and consulting relationships with Alosa Health and Aetion. Dr. Bhatt reported no relevant financial relationships.

*Correction, 8/16/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized Dr. Bhatt's comments on the availability of generic options.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sometimes we get what we pay for. Other times we pay too much.

That’s the message of a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, which finds that a generic maintenance inhaler is as effective at managing symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) as a pricier branded alternative.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved Wixela Inhub (the combination corticosteroid/long-acting beta2 adrenergic agonist fluticasone-salmeterol; Viatris) as a generic dry powder inhaler for managing symptoms of COPD. This approval was based on evidence of the generic’s effectiveness against asthma, although COPD also was on the product label. The study authors compared Wixela’s effectiveness in controlling symptoms of COPD with that of the brand name inhaler Advair Diskus (fluticasone-salmeterol; GlaxoSmithKline), which uses the same active ingredients.

The result: “The generic looks to be as safe and effective as the brand name. I don’t see a clinical reason why one would ever need to get the brand name over the generic version,” said study author William Feldman, MD, DPhil, MPH, a health services researcher and pulmonologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

Same types of patients, different inhalers, same outcomes

Dr. Feldman and colleagues compared the medical records of 10,000 patients with COPD who began using the branded inhaler to the records of another 10,000 patients with COPD who opted for the generic alternative. Participants in the two groups were evenly matched by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, region, severity of COPD, and presence of other comorbidities, according to the researchers. Participants were all older than age 40, and the average age in both groups was 72 years.

The researchers looked for a difference in a first episode of a moderate exacerbation of COPD, defined as requiring a course of prednisone for 5-14 days. They also looked for cases of severe COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the year after people began using either the generic or brand name inhaler. And they looked for differences across 1 year in rates of hospitalization for pneumonia.

For none of those outcomes, however, did the type of inhaler appear to matter. Compared with the brand-name drug, using the generic was associated with nearly identical rates of moderate or severe COPD exacerbation (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval, 0.90-1.04. The same was true for the proportion of people who went to the hospital for pneumonia at least once (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.86-1.15).

“To get through the FDA as an interchangeable generic, the generic firms have to show that their product can be used in just the same way as the brand-name version,” Dr. Feldman said, which may explain why the generic and brand-name versions of the inhaler performed so similarly.

Dr. Feldman cautioned that the price savings for patients who opt for the generic over the branded product are hard to determine, given the vagaries of different insurance plans and potential rebates when using the branded project. As a general matter, having a single generic competitor will not lower costs much, Dr. Feldman noted, pointing to 2017 research from Harvard that found a profusion of generic competitors is needed to significantly lower health care costs.

“I don’t want to in any way underestimate the importance of getting that first generic onto the market, because it sets the stage for future generics,” Dr. Feldman said.

“There are very few generic options for patients with COPD,” said Surya Bhatt, MD, director of the Pulmonary Function and Exercise Physiology Lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Even the rescue inhalers that people with COPD use to manage acute episodes of the condition are usually branded at this time, Dr. Bhatt noted, with few generic options.*

“The results are quite compelling,” said Dr. Bhatt, who was not involved in the research. Although the trial was not randomized, he commended the researchers for stratifying participants in the two groups to be as comparable as possible.

Dr. Bhatt noted that the FDA’s 2019 approval – given that the agency requires bioequivalence studies between branded and generic products – was enough to cause him to begin prescribing the generic inhaler. The fact that this approval was based on asthma but not also COPD is not a concern.

“There are so many similarities between asthma, COPD, and some obstructive lung diseases,” Dr. Bhatt noted.

In his experience, the only time someone with COPD continues using the branded inhaler – now that a potentially cheaper generic is available – is when their insurance plan makes their out-of-pocket cost minimal. Otherwise, brand loyalty does not exist.

“Patients are generally okay with being on a generic for inhalers, just because of the high cost,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The study was primarily supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Feldman reported funding from Arnold Ventures, the Commonwealth Fund, and the FDA, and consulting relationships with Alosa Health and Aetion. Dr. Bhatt reported no relevant financial relationships.

*Correction, 8/16/23: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized Dr. Bhatt's comments on the availability of generic options.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

COPD plus PRISm may promote frailty progression

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a new phenotype of lung function impairment predicted progression of frailty in older adults, based on data from more than 5,000 individuals.

COPD has been associated with frailty, but longitudinal data on the association of COPD with progression of frailty are limited, as are data on the potential association of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) with frailty progression, wrote Di He, BS, of Zhejiang University, China, and colleagues.

PRISm has been defined in recent studies as “proportional impairments in FEV1 and FVC, resulting in the normal ratio of FEV1 and FVC.” Individuals with PRISm may transition to normal spirometry or COPD over time, the researchers wrote.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 5,901 adults aged 50 years and older who were participating on the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), a prospective cohort study. Of these, 3,765 were included in an additional analysis of the association between transitions from normal spirometry to PRISm and the progression of frailty. The mean age of the participants was 65.5 years; 54.9% were women.

The median follow-up period for analysis with frailty progression was 9.5 years for PRISm and COPD and 5.8 years for PRISm transitions. Lung function data were collected at baseline. Based on spirometry data, participants were divided into three lung function groups – normal spirometry, PRISm, and COPD – and each of these was classified based on severity. Frailty was assessed using the frailty index (FI) during the follow-up period.

with additional annual increases of 0.301 and 0.172, respectively (P < .001 for both).

When stratified by severity, individuals with more severe PRISm and with more COPD had higher baseline FI and faster FI progression, compared with those with mild PRISm and COPD.

PRISm transitions were assessed over a 4-year interval at the start of the ELSA. Individuals with normal spirometry who transitioned to PRISm during the study had accelerated progression of frailty, as did those with COPD who transitioned to PRISm. However, no significant frailty progression occurred in those who changed from PRISm to normal spirometry.

The mechanisms behind the associations of PRISm and COPD with frailty remain unclear, but the results were consistent after controlling for multiple confounders, “suggesting PRISm and COPD had independent pathophysiological mechanisms for frailty,” the researchers write in their discussion. Other recent studies have identified sarcopenia as a complication for individuals with lung function impairment, they noted. “Therefore, another plausible explanation could be that PRISm and COPD caused sarcopenia, which accelerated frailty progression,” they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and the potential underestimation of lung function in participants with reversible airflow obstruction because of the use of prebronchodilator spirometry in the cohort study, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and high-quality data from the ELSA, as well as by the repeat measures of FI and lung function. The results were consistent after controlling for multiple confounders, and support the need for more research to explore the causality behind the association of PRISm and COPD with frailty, the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Basic Public Welfare Research Project, the Zhoushan Science and Technology Project, and the Key Laboratory of Intelligent Preventive Medicine of Zhejiang Province. The researchers report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a new phenotype of lung function impairment predicted progression of frailty in older adults, based on data from more than 5,000 individuals.

COPD has been associated with frailty, but longitudinal data on the association of COPD with progression of frailty are limited, as are data on the potential association of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) with frailty progression, wrote Di He, BS, of Zhejiang University, China, and colleagues.

PRISm has been defined in recent studies as “proportional impairments in FEV1 and FVC, resulting in the normal ratio of FEV1 and FVC.” Individuals with PRISm may transition to normal spirometry or COPD over time, the researchers wrote.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 5,901 adults aged 50 years and older who were participating on the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), a prospective cohort study. Of these, 3,765 were included in an additional analysis of the association between transitions from normal spirometry to PRISm and the progression of frailty. The mean age of the participants was 65.5 years; 54.9% were women.

The median follow-up period for analysis with frailty progression was 9.5 years for PRISm and COPD and 5.8 years for PRISm transitions. Lung function data were collected at baseline. Based on spirometry data, participants were divided into three lung function groups – normal spirometry, PRISm, and COPD – and each of these was classified based on severity. Frailty was assessed using the frailty index (FI) during the follow-up period.

with additional annual increases of 0.301 and 0.172, respectively (P < .001 for both).

When stratified by severity, individuals with more severe PRISm and with more COPD had higher baseline FI and faster FI progression, compared with those with mild PRISm and COPD.

PRISm transitions were assessed over a 4-year interval at the start of the ELSA. Individuals with normal spirometry who transitioned to PRISm during the study had accelerated progression of frailty, as did those with COPD who transitioned to PRISm. However, no significant frailty progression occurred in those who changed from PRISm to normal spirometry.

The mechanisms behind the associations of PRISm and COPD with frailty remain unclear, but the results were consistent after controlling for multiple confounders, “suggesting PRISm and COPD had independent pathophysiological mechanisms for frailty,” the researchers write in their discussion. Other recent studies have identified sarcopenia as a complication for individuals with lung function impairment, they noted. “Therefore, another plausible explanation could be that PRISm and COPD caused sarcopenia, which accelerated frailty progression,” they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and the potential underestimation of lung function in participants with reversible airflow obstruction because of the use of prebronchodilator spirometry in the cohort study, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and high-quality data from the ELSA, as well as by the repeat measures of FI and lung function. The results were consistent after controlling for multiple confounders, and support the need for more research to explore the causality behind the association of PRISm and COPD with frailty, the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Basic Public Welfare Research Project, the Zhoushan Science and Technology Project, and the Key Laboratory of Intelligent Preventive Medicine of Zhejiang Province. The researchers report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a new phenotype of lung function impairment predicted progression of frailty in older adults, based on data from more than 5,000 individuals.

COPD has been associated with frailty, but longitudinal data on the association of COPD with progression of frailty are limited, as are data on the potential association of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) with frailty progression, wrote Di He, BS, of Zhejiang University, China, and colleagues.

PRISm has been defined in recent studies as “proportional impairments in FEV1 and FVC, resulting in the normal ratio of FEV1 and FVC.” Individuals with PRISm may transition to normal spirometry or COPD over time, the researchers wrote.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 5,901 adults aged 50 years and older who were participating on the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), a prospective cohort study. Of these, 3,765 were included in an additional analysis of the association between transitions from normal spirometry to PRISm and the progression of frailty. The mean age of the participants was 65.5 years; 54.9% were women.

The median follow-up period for analysis with frailty progression was 9.5 years for PRISm and COPD and 5.8 years for PRISm transitions. Lung function data were collected at baseline. Based on spirometry data, participants were divided into three lung function groups – normal spirometry, PRISm, and COPD – and each of these was classified based on severity. Frailty was assessed using the frailty index (FI) during the follow-up period.

with additional annual increases of 0.301 and 0.172, respectively (P < .001 for both).

When stratified by severity, individuals with more severe PRISm and with more COPD had higher baseline FI and faster FI progression, compared with those with mild PRISm and COPD.

PRISm transitions were assessed over a 4-year interval at the start of the ELSA. Individuals with normal spirometry who transitioned to PRISm during the study had accelerated progression of frailty, as did those with COPD who transitioned to PRISm. However, no significant frailty progression occurred in those who changed from PRISm to normal spirometry.

The mechanisms behind the associations of PRISm and COPD with frailty remain unclear, but the results were consistent after controlling for multiple confounders, “suggesting PRISm and COPD had independent pathophysiological mechanisms for frailty,” the researchers write in their discussion. Other recent studies have identified sarcopenia as a complication for individuals with lung function impairment, they noted. “Therefore, another plausible explanation could be that PRISm and COPD caused sarcopenia, which accelerated frailty progression,” they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and the potential underestimation of lung function in participants with reversible airflow obstruction because of the use of prebronchodilator spirometry in the cohort study, the researchers noted.