User login

Readmission for COPD exacerbation upped in-hospital mortality risk

NEW ORLEANS – Reduction of readmission rates among individuals hospitalized for an acute exacerbation of COPD could reduce mortality and health care expenditures, results of a large, retrospective study suggest.

said researcher Anand Muthu Krishnan, MBBS, an from the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

“This is not a small problem,” Dr. Krishnan said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “The amount of money that can be saved can be put into primary care for curbing COPD and better patient outcomes, basically, if you’re able to put in checkpoints to stop this problem.”

Bundled care interventions by interdisciplinary teams have thus far proven effective at improving quality of care and improving process measures in this setting, said Dr. Krishnan.

The retrospective cohort study by Dr. Krishnan and colleagues included 530,229 adult patients in the 2016 National Readmission Database who had a principal diagnosis of acute COPD exacerbation. The mean age of the patients was 68 years, and 58% were female.

The rates of readmission at 30 days after discharge were 16.3% for any cause and 5.4% specifically for COPD, the researchers found. Of note, the in-hospital mortality rate increased from 1.1% to 3.8% during readmission (P less than .01), Dr. Krishnan said.

Readmissions were linked to a cumulative length of stay of 458,677 days, with corresponding hospital costs of $0.97 billion and charges of $4.0 billion; the COPD-specific readmissions were associated with cumulative length of stay of 132,026 days, costs of $253 million, and charges of $1 billion, Dr. Krishnan reported.

Dr. Krishnan and coauthors disclosed no relationships relevant to their study.

SOURCE: Krishnan AM et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.229.

NEW ORLEANS – Reduction of readmission rates among individuals hospitalized for an acute exacerbation of COPD could reduce mortality and health care expenditures, results of a large, retrospective study suggest.

said researcher Anand Muthu Krishnan, MBBS, an from the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

“This is not a small problem,” Dr. Krishnan said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “The amount of money that can be saved can be put into primary care for curbing COPD and better patient outcomes, basically, if you’re able to put in checkpoints to stop this problem.”

Bundled care interventions by interdisciplinary teams have thus far proven effective at improving quality of care and improving process measures in this setting, said Dr. Krishnan.

The retrospective cohort study by Dr. Krishnan and colleagues included 530,229 adult patients in the 2016 National Readmission Database who had a principal diagnosis of acute COPD exacerbation. The mean age of the patients was 68 years, and 58% were female.

The rates of readmission at 30 days after discharge were 16.3% for any cause and 5.4% specifically for COPD, the researchers found. Of note, the in-hospital mortality rate increased from 1.1% to 3.8% during readmission (P less than .01), Dr. Krishnan said.

Readmissions were linked to a cumulative length of stay of 458,677 days, with corresponding hospital costs of $0.97 billion and charges of $4.0 billion; the COPD-specific readmissions were associated with cumulative length of stay of 132,026 days, costs of $253 million, and charges of $1 billion, Dr. Krishnan reported.

Dr. Krishnan and coauthors disclosed no relationships relevant to their study.

SOURCE: Krishnan AM et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.229.

NEW ORLEANS – Reduction of readmission rates among individuals hospitalized for an acute exacerbation of COPD could reduce mortality and health care expenditures, results of a large, retrospective study suggest.

said researcher Anand Muthu Krishnan, MBBS, an from the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

“This is not a small problem,” Dr. Krishnan said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “The amount of money that can be saved can be put into primary care for curbing COPD and better patient outcomes, basically, if you’re able to put in checkpoints to stop this problem.”

Bundled care interventions by interdisciplinary teams have thus far proven effective at improving quality of care and improving process measures in this setting, said Dr. Krishnan.

The retrospective cohort study by Dr. Krishnan and colleagues included 530,229 adult patients in the 2016 National Readmission Database who had a principal diagnosis of acute COPD exacerbation. The mean age of the patients was 68 years, and 58% were female.

The rates of readmission at 30 days after discharge were 16.3% for any cause and 5.4% specifically for COPD, the researchers found. Of note, the in-hospital mortality rate increased from 1.1% to 3.8% during readmission (P less than .01), Dr. Krishnan said.

Readmissions were linked to a cumulative length of stay of 458,677 days, with corresponding hospital costs of $0.97 billion and charges of $4.0 billion; the COPD-specific readmissions were associated with cumulative length of stay of 132,026 days, costs of $253 million, and charges of $1 billion, Dr. Krishnan reported.

Dr. Krishnan and coauthors disclosed no relationships relevant to their study.

SOURCE: Krishnan AM et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.229.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Opioids, benzodiazepines carry greater risk of COPD-related hospitalization

according to recent research from Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

In addition, the risk of hospitalization because of respiratory events for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was greater when opioid and benzodiazepine medications were combined, compared with patients who did not take either medication, Jacques G. Baillargeon, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and community health at the University of Texas, Galveston, and colleagues wrote.

“Patients with COPD and their physicians should judiciously assess the risks and benefits of opioids and benzodiazepines, alone and in combination, and preferentially recommend nonopioid and nonbenzodiazepine approaches for pain, sleep, and anxiety management in patients with COPD,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers performed a case-control study of 3,232 Medicare beneficiary cases of COPD patients who were aged at least 66 years. Patients were included if they experienced a hospitalization related to a COPD-related adverse event with a respiratory diagnosis in 2014 and then matched to one or two control patients (total, 6,247 patients) based on age at hospitalization, gender, COPD medication, COPD complexity, obstructive sleep apnea, and socioeconomic status. COPD complexity was assigned to three levels (low, moderate, high) and calculated using the patient’s comorbid respiratory conditions and associated medical procedures in the 12 months prior to their hospitalization.

They found that, in the 30 days before COPD-related hospitalization, use of opioids was associated with greater likelihood of hospitalization (adjusted odds ratio, 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.52-1.97), as was use of benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.21-1.66). When patients used both opioids and benzodiazepines, they had a significantly higher risk of hospitalization, compared with patients who did not use opioids or benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.94-2.77).

In the 60 days prior to hospitalization, there was also a greater likelihood of hospitalization among COPD patients who used opioids (aOR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.47-1.88), benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.24-1.67), and both opioids and benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.93-2.67); at 90 days, this higher risk of hospitalization persisted among COPD patients taking opioids (aOR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.40-1.78), benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.20-1.63), and both opioids and benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.88-2.59).

The researchers acknowledged that one potential limitation in the study was how COPD diagnoses were obtained through coding performed by clinicians instead of from laboratory testing. Confounding by COPD indication and severity; use of over-the-counter medication or opioids and benzodiazepines received illegally; and lack of analyses of potential confounders such as diet, alcohol use, smoking status and herbal supplement use were other limitations.

This study was supported by an award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Baillargeon had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Baillargeon JG et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201901-024OC.

according to recent research from Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

In addition, the risk of hospitalization because of respiratory events for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was greater when opioid and benzodiazepine medications were combined, compared with patients who did not take either medication, Jacques G. Baillargeon, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and community health at the University of Texas, Galveston, and colleagues wrote.

“Patients with COPD and their physicians should judiciously assess the risks and benefits of opioids and benzodiazepines, alone and in combination, and preferentially recommend nonopioid and nonbenzodiazepine approaches for pain, sleep, and anxiety management in patients with COPD,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers performed a case-control study of 3,232 Medicare beneficiary cases of COPD patients who were aged at least 66 years. Patients were included if they experienced a hospitalization related to a COPD-related adverse event with a respiratory diagnosis in 2014 and then matched to one or two control patients (total, 6,247 patients) based on age at hospitalization, gender, COPD medication, COPD complexity, obstructive sleep apnea, and socioeconomic status. COPD complexity was assigned to three levels (low, moderate, high) and calculated using the patient’s comorbid respiratory conditions and associated medical procedures in the 12 months prior to their hospitalization.

They found that, in the 30 days before COPD-related hospitalization, use of opioids was associated with greater likelihood of hospitalization (adjusted odds ratio, 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.52-1.97), as was use of benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.21-1.66). When patients used both opioids and benzodiazepines, they had a significantly higher risk of hospitalization, compared with patients who did not use opioids or benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.94-2.77).

In the 60 days prior to hospitalization, there was also a greater likelihood of hospitalization among COPD patients who used opioids (aOR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.47-1.88), benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.24-1.67), and both opioids and benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.93-2.67); at 90 days, this higher risk of hospitalization persisted among COPD patients taking opioids (aOR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.40-1.78), benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.20-1.63), and both opioids and benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.88-2.59).

The researchers acknowledged that one potential limitation in the study was how COPD diagnoses were obtained through coding performed by clinicians instead of from laboratory testing. Confounding by COPD indication and severity; use of over-the-counter medication or opioids and benzodiazepines received illegally; and lack of analyses of potential confounders such as diet, alcohol use, smoking status and herbal supplement use were other limitations.

This study was supported by an award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Baillargeon had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Baillargeon JG et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201901-024OC.

according to recent research from Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

In addition, the risk of hospitalization because of respiratory events for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was greater when opioid and benzodiazepine medications were combined, compared with patients who did not take either medication, Jacques G. Baillargeon, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and community health at the University of Texas, Galveston, and colleagues wrote.

“Patients with COPD and their physicians should judiciously assess the risks and benefits of opioids and benzodiazepines, alone and in combination, and preferentially recommend nonopioid and nonbenzodiazepine approaches for pain, sleep, and anxiety management in patients with COPD,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers performed a case-control study of 3,232 Medicare beneficiary cases of COPD patients who were aged at least 66 years. Patients were included if they experienced a hospitalization related to a COPD-related adverse event with a respiratory diagnosis in 2014 and then matched to one or two control patients (total, 6,247 patients) based on age at hospitalization, gender, COPD medication, COPD complexity, obstructive sleep apnea, and socioeconomic status. COPD complexity was assigned to three levels (low, moderate, high) and calculated using the patient’s comorbid respiratory conditions and associated medical procedures in the 12 months prior to their hospitalization.

They found that, in the 30 days before COPD-related hospitalization, use of opioids was associated with greater likelihood of hospitalization (adjusted odds ratio, 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.52-1.97), as was use of benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.21-1.66). When patients used both opioids and benzodiazepines, they had a significantly higher risk of hospitalization, compared with patients who did not use opioids or benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.94-2.77).

In the 60 days prior to hospitalization, there was also a greater likelihood of hospitalization among COPD patients who used opioids (aOR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.47-1.88), benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.24-1.67), and both opioids and benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.93-2.67); at 90 days, this higher risk of hospitalization persisted among COPD patients taking opioids (aOR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.40-1.78), benzodiazepines (aOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.20-1.63), and both opioids and benzodiazepines (aOR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.88-2.59).

The researchers acknowledged that one potential limitation in the study was how COPD diagnoses were obtained through coding performed by clinicians instead of from laboratory testing. Confounding by COPD indication and severity; use of over-the-counter medication or opioids and benzodiazepines received illegally; and lack of analyses of potential confounders such as diet, alcohol use, smoking status and herbal supplement use were other limitations.

This study was supported by an award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Baillargeon had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Baillargeon JG et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019 Oct 1. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201901-024OC.

FROM ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY

Recent COPD exacerbation did not affect aclidinium’s efficacy in high-risk patients

NEW ORLEANS – A history of recent exacerbations did not significantly affect the safety or efficacy of aclidinium bromide (Tudorza) in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and high cardiovascular risk, analysis of a postmarketing surveillance trial suggests.

Regardless of exacerbation history, the long-acting muscarinic antagonist reduced the rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations versus placebo in this subgroup analysis of the phase IV ASCENT-COPD trial, presented here at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

At the same time, there were no significant increases in the risk of mortality or major cardiac adverse events (MACE) for those patients who had an exacerbation in the past year versus those who did not, according to investigator Robert A. Wise, MD.

Those findings may be reassuring, given that COPD patients commonly have comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors, according to Dr. Wise, professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“There’s a concern and some evidence that patients who have a propensity to COPD exacerbations may also have an increased risk for cardiovascular events,” Dr. Wise said in a podium presentation.

Accordingly, he and coinvestigators sought to tease out the impact of COPD exacerbations on safety as well as efficacy in the randomized, placebo-controlled ASCENT-COPD trial, which included 3,630 patients with moderate to severe COPD plus a cardiovascular disease history or multiple atherothrombotic risk factors.

Of the patients who were analyzed in the study, 1,433 patients had at least one treated COPD exacerbation in the year before screening for the study, while 2,156 had no exacerbations in the prior year, Dr. Wise said.

Top-line results of that study, published several months ago, showed that aclidinium did not increase MACE risk over 3 years, and reduced the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations over the first year (JAMA. 2019 7 May 7;321[17]:1693-701).

In this latest analysis, presented at the meeting, risk of MACE with aclidinium treatment was not increased versus placebo, irrespective of whether they had exacerbations in the prior year (interaction P = .233); likewise, the risk of all-cause mortality was similar between groups (P = .154).

In terms of reduction in moderate or severe COPD exacerbations in the first year, aclidinium was superior to placebo both for the patients who had at least one or exacerbation in the prior year (rate ratio, 0.80) and those who had no exacerbations in the prior year (RR, 0.69).

“This translates into a number-needed-to-treat to prevent one exacerbation of about 11 patients for those without an exacerbation, compared to about 6 patients for those with a prior exacerbation,” Dr. Wise said in his presentation.

The ASCENT-COPD study was funded initially by Forest Laboratories and later by AstraZeneca and Circassia. Dr. Wise provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sunovion, Mylan/Theravance, Contrafect, Pearl, Merck, Verona, Novartis, AbbVie, Syneos, Regeneron, and Kiniksa.

SOURCE: Wise R et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.231.

NEW ORLEANS – A history of recent exacerbations did not significantly affect the safety or efficacy of aclidinium bromide (Tudorza) in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and high cardiovascular risk, analysis of a postmarketing surveillance trial suggests.

Regardless of exacerbation history, the long-acting muscarinic antagonist reduced the rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations versus placebo in this subgroup analysis of the phase IV ASCENT-COPD trial, presented here at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

At the same time, there were no significant increases in the risk of mortality or major cardiac adverse events (MACE) for those patients who had an exacerbation in the past year versus those who did not, according to investigator Robert A. Wise, MD.

Those findings may be reassuring, given that COPD patients commonly have comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors, according to Dr. Wise, professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“There’s a concern and some evidence that patients who have a propensity to COPD exacerbations may also have an increased risk for cardiovascular events,” Dr. Wise said in a podium presentation.

Accordingly, he and coinvestigators sought to tease out the impact of COPD exacerbations on safety as well as efficacy in the randomized, placebo-controlled ASCENT-COPD trial, which included 3,630 patients with moderate to severe COPD plus a cardiovascular disease history or multiple atherothrombotic risk factors.

Of the patients who were analyzed in the study, 1,433 patients had at least one treated COPD exacerbation in the year before screening for the study, while 2,156 had no exacerbations in the prior year, Dr. Wise said.

Top-line results of that study, published several months ago, showed that aclidinium did not increase MACE risk over 3 years, and reduced the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations over the first year (JAMA. 2019 7 May 7;321[17]:1693-701).

In this latest analysis, presented at the meeting, risk of MACE with aclidinium treatment was not increased versus placebo, irrespective of whether they had exacerbations in the prior year (interaction P = .233); likewise, the risk of all-cause mortality was similar between groups (P = .154).

In terms of reduction in moderate or severe COPD exacerbations in the first year, aclidinium was superior to placebo both for the patients who had at least one or exacerbation in the prior year (rate ratio, 0.80) and those who had no exacerbations in the prior year (RR, 0.69).

“This translates into a number-needed-to-treat to prevent one exacerbation of about 11 patients for those without an exacerbation, compared to about 6 patients for those with a prior exacerbation,” Dr. Wise said in his presentation.

The ASCENT-COPD study was funded initially by Forest Laboratories and later by AstraZeneca and Circassia. Dr. Wise provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sunovion, Mylan/Theravance, Contrafect, Pearl, Merck, Verona, Novartis, AbbVie, Syneos, Regeneron, and Kiniksa.

SOURCE: Wise R et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.231.

NEW ORLEANS – A history of recent exacerbations did not significantly affect the safety or efficacy of aclidinium bromide (Tudorza) in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and high cardiovascular risk, analysis of a postmarketing surveillance trial suggests.

Regardless of exacerbation history, the long-acting muscarinic antagonist reduced the rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations versus placebo in this subgroup analysis of the phase IV ASCENT-COPD trial, presented here at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

At the same time, there were no significant increases in the risk of mortality or major cardiac adverse events (MACE) for those patients who had an exacerbation in the past year versus those who did not, according to investigator Robert A. Wise, MD.

Those findings may be reassuring, given that COPD patients commonly have comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors, according to Dr. Wise, professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“There’s a concern and some evidence that patients who have a propensity to COPD exacerbations may also have an increased risk for cardiovascular events,” Dr. Wise said in a podium presentation.

Accordingly, he and coinvestigators sought to tease out the impact of COPD exacerbations on safety as well as efficacy in the randomized, placebo-controlled ASCENT-COPD trial, which included 3,630 patients with moderate to severe COPD plus a cardiovascular disease history or multiple atherothrombotic risk factors.

Of the patients who were analyzed in the study, 1,433 patients had at least one treated COPD exacerbation in the year before screening for the study, while 2,156 had no exacerbations in the prior year, Dr. Wise said.

Top-line results of that study, published several months ago, showed that aclidinium did not increase MACE risk over 3 years, and reduced the rate of moderate to severe COPD exacerbations over the first year (JAMA. 2019 7 May 7;321[17]:1693-701).

In this latest analysis, presented at the meeting, risk of MACE with aclidinium treatment was not increased versus placebo, irrespective of whether they had exacerbations in the prior year (interaction P = .233); likewise, the risk of all-cause mortality was similar between groups (P = .154).

In terms of reduction in moderate or severe COPD exacerbations in the first year, aclidinium was superior to placebo both for the patients who had at least one or exacerbation in the prior year (rate ratio, 0.80) and those who had no exacerbations in the prior year (RR, 0.69).

“This translates into a number-needed-to-treat to prevent one exacerbation of about 11 patients for those without an exacerbation, compared to about 6 patients for those with a prior exacerbation,” Dr. Wise said in his presentation.

The ASCENT-COPD study was funded initially by Forest Laboratories and later by AstraZeneca and Circassia. Dr. Wise provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sunovion, Mylan/Theravance, Contrafect, Pearl, Merck, Verona, Novartis, AbbVie, Syneos, Regeneron, and Kiniksa.

SOURCE: Wise R et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.231.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Beta-blocker treatment did not reduce exacerbation risk in COPD

A new study has found that beta-blocker treatment did not prevent exacerbations in patients with moderate or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

“These results differ from previously reported findings from observational studies suggesting that beta-blockers reduce the risks of exacerbation and death from any cause in patients with COPD,” wrote Mark T. Dransfield, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and coauthors. Their findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians and also were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To determine the value of beta-blockers as a potential treatment for COPD, the researchers launched a prospective randomized trial called BLOCK COPD, consisting of 532 patients with moderate or severe COPD. They were assigned to two groups: those receiving extended-release metoprolol (n = 268) and those receiving placebo (n = 264). The mean age of all patients was 65 years.

The groups saw no significant difference in median time until the first exacerbation, which was 202 days (95% confidence interval, 162-282) in the metoprolol group and 222 days (95% CI, 189-295) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.32; P = .66). Metoprolol was associated with a higher risk of severe or very severe exacerbations leading to hospitalization (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.29-2.83). During treatment, there were 11 deaths in the metoprolol group and 5 deaths in the placebo group.

Though there was no evidence of increases in patient-reported adverse events related to metoprolol, more discontinuations did occur in the metoprolol group compared with placebo (11.2% vs. 6.1%).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, chiefly including the fact that the trial was ended early “on the basis of the conditional power analyses and concern about safety.” In addition, the reduction of heart rate and blood pressure in the metoprolol group made it impossible to fully blind the study. Finally, many patients in the trial had already suffered the effects of moderate to severe COPD, including previous hospitalization and the need for supplemental oxygen, leading to uncertainty as to “whether our results would apply to patients with mild airflow obstruction or a lower exacerbation risk.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Department of Defense. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, personal fees and research funds from various pharmaceutical companies and government entities.

SOURCE: Dransfield MT et al. CHEST 2019. 2019 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908142.

A new study has found that beta-blocker treatment did not prevent exacerbations in patients with moderate or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

“These results differ from previously reported findings from observational studies suggesting that beta-blockers reduce the risks of exacerbation and death from any cause in patients with COPD,” wrote Mark T. Dransfield, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and coauthors. Their findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians and also were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To determine the value of beta-blockers as a potential treatment for COPD, the researchers launched a prospective randomized trial called BLOCK COPD, consisting of 532 patients with moderate or severe COPD. They were assigned to two groups: those receiving extended-release metoprolol (n = 268) and those receiving placebo (n = 264). The mean age of all patients was 65 years.

The groups saw no significant difference in median time until the first exacerbation, which was 202 days (95% confidence interval, 162-282) in the metoprolol group and 222 days (95% CI, 189-295) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.32; P = .66). Metoprolol was associated with a higher risk of severe or very severe exacerbations leading to hospitalization (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.29-2.83). During treatment, there were 11 deaths in the metoprolol group and 5 deaths in the placebo group.

Though there was no evidence of increases in patient-reported adverse events related to metoprolol, more discontinuations did occur in the metoprolol group compared with placebo (11.2% vs. 6.1%).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, chiefly including the fact that the trial was ended early “on the basis of the conditional power analyses and concern about safety.” In addition, the reduction of heart rate and blood pressure in the metoprolol group made it impossible to fully blind the study. Finally, many patients in the trial had already suffered the effects of moderate to severe COPD, including previous hospitalization and the need for supplemental oxygen, leading to uncertainty as to “whether our results would apply to patients with mild airflow obstruction or a lower exacerbation risk.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Department of Defense. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, personal fees and research funds from various pharmaceutical companies and government entities.

SOURCE: Dransfield MT et al. CHEST 2019. 2019 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908142.

A new study has found that beta-blocker treatment did not prevent exacerbations in patients with moderate or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

“These results differ from previously reported findings from observational studies suggesting that beta-blockers reduce the risks of exacerbation and death from any cause in patients with COPD,” wrote Mark T. Dransfield, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and coauthors. Their findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians and also were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To determine the value of beta-blockers as a potential treatment for COPD, the researchers launched a prospective randomized trial called BLOCK COPD, consisting of 532 patients with moderate or severe COPD. They were assigned to two groups: those receiving extended-release metoprolol (n = 268) and those receiving placebo (n = 264). The mean age of all patients was 65 years.

The groups saw no significant difference in median time until the first exacerbation, which was 202 days (95% confidence interval, 162-282) in the metoprolol group and 222 days (95% CI, 189-295) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.32; P = .66). Metoprolol was associated with a higher risk of severe or very severe exacerbations leading to hospitalization (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.29-2.83). During treatment, there were 11 deaths in the metoprolol group and 5 deaths in the placebo group.

Though there was no evidence of increases in patient-reported adverse events related to metoprolol, more discontinuations did occur in the metoprolol group compared with placebo (11.2% vs. 6.1%).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, chiefly including the fact that the trial was ended early “on the basis of the conditional power analyses and concern about safety.” In addition, the reduction of heart rate and blood pressure in the metoprolol group made it impossible to fully blind the study. Finally, many patients in the trial had already suffered the effects of moderate to severe COPD, including previous hospitalization and the need for supplemental oxygen, leading to uncertainty as to “whether our results would apply to patients with mild airflow obstruction or a lower exacerbation risk.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Department of Defense. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, personal fees and research funds from various pharmaceutical companies and government entities.

SOURCE: Dransfield MT et al. CHEST 2019. 2019 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908142.

FROM CHEST 2019

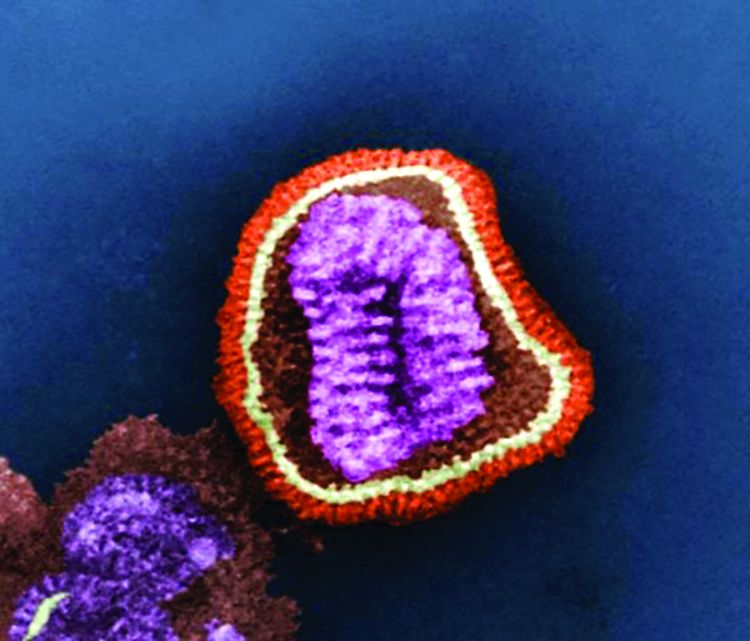

Influenza vaccination modestly reduces risk of hospitalizations in patients with COPD

(COPD), according to data published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large, real-world population study to examine vaccine effectiveness in people with COPD using the test-negative design and influenza-specific study outcomes,” wrote Andrea S. Gershon, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto and colleagues. “These findings emphasize the need for more effective influenza vaccines for older COPD patients and other preventive strategies.”

A test-negative study design

Data suggest that 70% of COPD exacerbations are caused by infection, and influenza often is identified as the cause. Although all major COPD practice guidelines recommend seasonal influenza vaccination, the evidence indicating that vaccination reduces hospitalizations and death is limited. The inherent or corticosteroid-induced decrease in immune response to vaccination and respiratory infection among patients with COPD may reduce the effectiveness of influenza vaccination, wrote Dr. Gershon and colleagues.

The investigators used a test-negative design to evaluate how effectively influenza vaccination prevents laboratory-confirmed influenza–associated hospitalizations in community-dwelling older patients with COPD. They chose this design because it attenuates biases resulting from misclassification of infection and from differences in health care–seeking behavior between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients.

Dr. Gershon and colleagues examined health care administrative data and respiratory specimens collected from patients who had been tested for influenza during the 2010-2011 to 2015-2016 influenza seasons. Eligible patients were aged 66 years or older, had physician-diagnosed COPD, and had been tested for influenza within 3 days before and during an acute care hospitalization. The researchers determined influenza vaccination status using physician and pharmacist billing claims. They obtained demographic information through linkage with the provincial health insurance database. Multivariable logistic regression allowed Dr. Gershon and colleagues to estimate the adjusted odds ratio of influenza vaccination in people with laboratory-confirmed influenza, compared with those without.

Effectiveness did not vary by demographic factors

The investigators included 21,748 patients in their analysis. Of this population, 3,636 (16.7%) patients tested positive for influenza. Vaccinated patients were less likely than unvaccinated patients to test positive for influenza (15.3% vs. 18.6%). Vaccinated patients also were more likely to be older; live in an urban area; live in a higher income neighborhood; have had more outpatient visits with a physician in the previous year; have received a prescription for a COPD medication in the previous 6 months; have diabetes, asthma, or immunocompromising conditions; have a longer duration of COPD; and have had an outpatient COPD exacerbation in the previous year.

The overall unadjusted estimate of vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza–associated hospitalizations was 21%. Multivariable adjustment yielded an effectiveness of 22%. When Dr. Gershon and colleagues corrected for misclassification of vaccination status among people with COPD, the effectiveness was estimated to be 43%. Vaccine effectiveness did not vary significantly according to influenza season, nor did it vary significantly by patient-specific factors such as age, sex, influenza subtype, codiagnosis of asthma, duration of COPD, previous outpatient COPD exacerbations, previous COPD hospitalization, previous receipt of inhaled corticosteroids, and previous pneumonia.

One limitation of the study was the possibility that COPD was misclassified because not all participants underwent pulmonary function testing. In addition, the estimates of vaccine effectiveness in the present study are specific to the outcome of influenza hospitalization and may not be generalizable to vaccine effectiveness estimates of outpatient outcomes, said the investigators. Finally, Dr. Gershon and colleagues could not identify the type of vaccine received.

“Given that a large pragmatic randomized controlled trial evaluating influenza vaccination would be unethical, this is likely the most robust estimate of vaccine effectiveness for hospitalizations in the COPD population to guide influenza vaccine recommendations for patients with COPD,” wrote Dr. Gershon and colleagues.

An Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health Systems Research Fund Capacity Grant and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant funded this research. One investigator received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the study, and others received grants from pharmaceutical companies that were unrelated to this study.

SOURCE: Gershon AS et al. J Infect Dis. 2019 Sep 24. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz419.

(COPD), according to data published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large, real-world population study to examine vaccine effectiveness in people with COPD using the test-negative design and influenza-specific study outcomes,” wrote Andrea S. Gershon, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto and colleagues. “These findings emphasize the need for more effective influenza vaccines for older COPD patients and other preventive strategies.”

A test-negative study design

Data suggest that 70% of COPD exacerbations are caused by infection, and influenza often is identified as the cause. Although all major COPD practice guidelines recommend seasonal influenza vaccination, the evidence indicating that vaccination reduces hospitalizations and death is limited. The inherent or corticosteroid-induced decrease in immune response to vaccination and respiratory infection among patients with COPD may reduce the effectiveness of influenza vaccination, wrote Dr. Gershon and colleagues.

The investigators used a test-negative design to evaluate how effectively influenza vaccination prevents laboratory-confirmed influenza–associated hospitalizations in community-dwelling older patients with COPD. They chose this design because it attenuates biases resulting from misclassification of infection and from differences in health care–seeking behavior between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients.

Dr. Gershon and colleagues examined health care administrative data and respiratory specimens collected from patients who had been tested for influenza during the 2010-2011 to 2015-2016 influenza seasons. Eligible patients were aged 66 years or older, had physician-diagnosed COPD, and had been tested for influenza within 3 days before and during an acute care hospitalization. The researchers determined influenza vaccination status using physician and pharmacist billing claims. They obtained demographic information through linkage with the provincial health insurance database. Multivariable logistic regression allowed Dr. Gershon and colleagues to estimate the adjusted odds ratio of influenza vaccination in people with laboratory-confirmed influenza, compared with those without.

Effectiveness did not vary by demographic factors

The investigators included 21,748 patients in their analysis. Of this population, 3,636 (16.7%) patients tested positive for influenza. Vaccinated patients were less likely than unvaccinated patients to test positive for influenza (15.3% vs. 18.6%). Vaccinated patients also were more likely to be older; live in an urban area; live in a higher income neighborhood; have had more outpatient visits with a physician in the previous year; have received a prescription for a COPD medication in the previous 6 months; have diabetes, asthma, or immunocompromising conditions; have a longer duration of COPD; and have had an outpatient COPD exacerbation in the previous year.

The overall unadjusted estimate of vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza–associated hospitalizations was 21%. Multivariable adjustment yielded an effectiveness of 22%. When Dr. Gershon and colleagues corrected for misclassification of vaccination status among people with COPD, the effectiveness was estimated to be 43%. Vaccine effectiveness did not vary significantly according to influenza season, nor did it vary significantly by patient-specific factors such as age, sex, influenza subtype, codiagnosis of asthma, duration of COPD, previous outpatient COPD exacerbations, previous COPD hospitalization, previous receipt of inhaled corticosteroids, and previous pneumonia.

One limitation of the study was the possibility that COPD was misclassified because not all participants underwent pulmonary function testing. In addition, the estimates of vaccine effectiveness in the present study are specific to the outcome of influenza hospitalization and may not be generalizable to vaccine effectiveness estimates of outpatient outcomes, said the investigators. Finally, Dr. Gershon and colleagues could not identify the type of vaccine received.

“Given that a large pragmatic randomized controlled trial evaluating influenza vaccination would be unethical, this is likely the most robust estimate of vaccine effectiveness for hospitalizations in the COPD population to guide influenza vaccine recommendations for patients with COPD,” wrote Dr. Gershon and colleagues.

An Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health Systems Research Fund Capacity Grant and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant funded this research. One investigator received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the study, and others received grants from pharmaceutical companies that were unrelated to this study.

SOURCE: Gershon AS et al. J Infect Dis. 2019 Sep 24. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz419.

(COPD), according to data published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large, real-world population study to examine vaccine effectiveness in people with COPD using the test-negative design and influenza-specific study outcomes,” wrote Andrea S. Gershon, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto and colleagues. “These findings emphasize the need for more effective influenza vaccines for older COPD patients and other preventive strategies.”

A test-negative study design

Data suggest that 70% of COPD exacerbations are caused by infection, and influenza often is identified as the cause. Although all major COPD practice guidelines recommend seasonal influenza vaccination, the evidence indicating that vaccination reduces hospitalizations and death is limited. The inherent or corticosteroid-induced decrease in immune response to vaccination and respiratory infection among patients with COPD may reduce the effectiveness of influenza vaccination, wrote Dr. Gershon and colleagues.

The investigators used a test-negative design to evaluate how effectively influenza vaccination prevents laboratory-confirmed influenza–associated hospitalizations in community-dwelling older patients with COPD. They chose this design because it attenuates biases resulting from misclassification of infection and from differences in health care–seeking behavior between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients.

Dr. Gershon and colleagues examined health care administrative data and respiratory specimens collected from patients who had been tested for influenza during the 2010-2011 to 2015-2016 influenza seasons. Eligible patients were aged 66 years or older, had physician-diagnosed COPD, and had been tested for influenza within 3 days before and during an acute care hospitalization. The researchers determined influenza vaccination status using physician and pharmacist billing claims. They obtained demographic information through linkage with the provincial health insurance database. Multivariable logistic regression allowed Dr. Gershon and colleagues to estimate the adjusted odds ratio of influenza vaccination in people with laboratory-confirmed influenza, compared with those without.

Effectiveness did not vary by demographic factors

The investigators included 21,748 patients in their analysis. Of this population, 3,636 (16.7%) patients tested positive for influenza. Vaccinated patients were less likely than unvaccinated patients to test positive for influenza (15.3% vs. 18.6%). Vaccinated patients also were more likely to be older; live in an urban area; live in a higher income neighborhood; have had more outpatient visits with a physician in the previous year; have received a prescription for a COPD medication in the previous 6 months; have diabetes, asthma, or immunocompromising conditions; have a longer duration of COPD; and have had an outpatient COPD exacerbation in the previous year.

The overall unadjusted estimate of vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza–associated hospitalizations was 21%. Multivariable adjustment yielded an effectiveness of 22%. When Dr. Gershon and colleagues corrected for misclassification of vaccination status among people with COPD, the effectiveness was estimated to be 43%. Vaccine effectiveness did not vary significantly according to influenza season, nor did it vary significantly by patient-specific factors such as age, sex, influenza subtype, codiagnosis of asthma, duration of COPD, previous outpatient COPD exacerbations, previous COPD hospitalization, previous receipt of inhaled corticosteroids, and previous pneumonia.

One limitation of the study was the possibility that COPD was misclassified because not all participants underwent pulmonary function testing. In addition, the estimates of vaccine effectiveness in the present study are specific to the outcome of influenza hospitalization and may not be generalizable to vaccine effectiveness estimates of outpatient outcomes, said the investigators. Finally, Dr. Gershon and colleagues could not identify the type of vaccine received.

“Given that a large pragmatic randomized controlled trial evaluating influenza vaccination would be unethical, this is likely the most robust estimate of vaccine effectiveness for hospitalizations in the COPD population to guide influenza vaccine recommendations for patients with COPD,” wrote Dr. Gershon and colleagues.

An Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health Systems Research Fund Capacity Grant and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant funded this research. One investigator received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the study, and others received grants from pharmaceutical companies that were unrelated to this study.

SOURCE: Gershon AS et al. J Infect Dis. 2019 Sep 24. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz419.

FROM JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

New guideline conditionally recommends long-term home NIV for COPD patients

from a European Respiratory Society task force.

“Our recommendations, based on the best available evidence, can guide the management of chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure in COPD patients aimed at improving patient outcomes,” wrote Begum Ergan, MD, of Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey, and coauthors. The guideline was published in the European Respiratory Journal.

To provide insight into the clinical application of LTH-NIV, the European Respiratory Society convened a task force of 20 clinicians, methodologists, and experts. Their four recommendations were developed based on the GRADE (Grading, Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology.

The first recommendation was to use LTH-NIV for patients with chronic stable hypercapnic COPD. Though an analysis of randomized, controlled trials showed little effect on mortality or hospitalizations, pooled analyses showed that NIV may decrease dyspnea scores (standardized mean difference, –0.51; 95% confidence interval, –0.06 to –0.95) and increase health-related quality of life (SMD, 0.49; 95% CI, –0.01 to 0.98).

The second was to use LTH-NIV in patients with COPD following a life-threatening episode of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring acute NIV, if hypercapnia persists. Though it was not associated with a reduction in mortality (risk ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.67-1.25), it was found to potentially reduce exacerbations (SMD, 0.19; 95% CI, –0.40 to 0.01) and hospitalizations (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.30-1.24).

The third was to titrate LTH-NIV to normalize or reduce PaCO2 levels in patients with COPD. While this recommendation was issued with a very low certainty of evidence, it was driven by the “minimal potential harms of targeted PaCO2 reduction.”

The fourth was to use fixed pressure support mode as first-choice ventilator mode in patients with COPD using LTH-NIV. The six trials on this subject did not provide insight into long-term outcomes, nor were there significant improvements seen in health-related quality of life, sleep quality, or exercise tolerance. As such, it was also issued with a very low certainty of evidence.

The authors acknowledged all four recommendations as weak and conditional, “due to limitations in the certainty of the available evidence.” As such, they noted that their recommendations “require consideration of individual preferences, resource considerations, technical expertise, and clinical circumstances prior to implementation in clinical practice.”

The authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving grants and personal fees from various medical supply companies.

SOURCE: Ergan B et al. Eur Respir J. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01003-2019.

from a European Respiratory Society task force.

“Our recommendations, based on the best available evidence, can guide the management of chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure in COPD patients aimed at improving patient outcomes,” wrote Begum Ergan, MD, of Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey, and coauthors. The guideline was published in the European Respiratory Journal.

To provide insight into the clinical application of LTH-NIV, the European Respiratory Society convened a task force of 20 clinicians, methodologists, and experts. Their four recommendations were developed based on the GRADE (Grading, Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology.

The first recommendation was to use LTH-NIV for patients with chronic stable hypercapnic COPD. Though an analysis of randomized, controlled trials showed little effect on mortality or hospitalizations, pooled analyses showed that NIV may decrease dyspnea scores (standardized mean difference, –0.51; 95% confidence interval, –0.06 to –0.95) and increase health-related quality of life (SMD, 0.49; 95% CI, –0.01 to 0.98).

The second was to use LTH-NIV in patients with COPD following a life-threatening episode of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring acute NIV, if hypercapnia persists. Though it was not associated with a reduction in mortality (risk ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.67-1.25), it was found to potentially reduce exacerbations (SMD, 0.19; 95% CI, –0.40 to 0.01) and hospitalizations (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.30-1.24).

The third was to titrate LTH-NIV to normalize or reduce PaCO2 levels in patients with COPD. While this recommendation was issued with a very low certainty of evidence, it was driven by the “minimal potential harms of targeted PaCO2 reduction.”

The fourth was to use fixed pressure support mode as first-choice ventilator mode in patients with COPD using LTH-NIV. The six trials on this subject did not provide insight into long-term outcomes, nor were there significant improvements seen in health-related quality of life, sleep quality, or exercise tolerance. As such, it was also issued with a very low certainty of evidence.

The authors acknowledged all four recommendations as weak and conditional, “due to limitations in the certainty of the available evidence.” As such, they noted that their recommendations “require consideration of individual preferences, resource considerations, technical expertise, and clinical circumstances prior to implementation in clinical practice.”

The authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving grants and personal fees from various medical supply companies.

SOURCE: Ergan B et al. Eur Respir J. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01003-2019.

from a European Respiratory Society task force.

“Our recommendations, based on the best available evidence, can guide the management of chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure in COPD patients aimed at improving patient outcomes,” wrote Begum Ergan, MD, of Dokuz Eylul University, Izmir, Turkey, and coauthors. The guideline was published in the European Respiratory Journal.

To provide insight into the clinical application of LTH-NIV, the European Respiratory Society convened a task force of 20 clinicians, methodologists, and experts. Their four recommendations were developed based on the GRADE (Grading, Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology.

The first recommendation was to use LTH-NIV for patients with chronic stable hypercapnic COPD. Though an analysis of randomized, controlled trials showed little effect on mortality or hospitalizations, pooled analyses showed that NIV may decrease dyspnea scores (standardized mean difference, –0.51; 95% confidence interval, –0.06 to –0.95) and increase health-related quality of life (SMD, 0.49; 95% CI, –0.01 to 0.98).

The second was to use LTH-NIV in patients with COPD following a life-threatening episode of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring acute NIV, if hypercapnia persists. Though it was not associated with a reduction in mortality (risk ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.67-1.25), it was found to potentially reduce exacerbations (SMD, 0.19; 95% CI, –0.40 to 0.01) and hospitalizations (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.30-1.24).

The third was to titrate LTH-NIV to normalize or reduce PaCO2 levels in patients with COPD. While this recommendation was issued with a very low certainty of evidence, it was driven by the “minimal potential harms of targeted PaCO2 reduction.”

The fourth was to use fixed pressure support mode as first-choice ventilator mode in patients with COPD using LTH-NIV. The six trials on this subject did not provide insight into long-term outcomes, nor were there significant improvements seen in health-related quality of life, sleep quality, or exercise tolerance. As such, it was also issued with a very low certainty of evidence.

The authors acknowledged all four recommendations as weak and conditional, “due to limitations in the certainty of the available evidence.” As such, they noted that their recommendations “require consideration of individual preferences, resource considerations, technical expertise, and clinical circumstances prior to implementation in clinical practice.”

The authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving grants and personal fees from various medical supply companies.

SOURCE: Ergan B et al. Eur Respir J. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01003-2019.

FROM THE EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL

Wildfire smoke has acute cardiorespiratory impact, but long-term effects still under study

The 2019 wildfire season is underway in many locales across the United States, exposing millions of individuals to smoky conditions that will have health consequences ranging from stinging eyes to scratchy throats to a trip to the ED for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation. Questions about long-term health impacts are on the minds of many, including physicians and their patients who live with cardiorespiratory conditions.

John R. Balmes, MD, a pulmonologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the respiratory and cardiovascular effects of air pollutants, suggested that the best available published literature points to “pretty strong evidence for acute effects of wildfire smoke on respiratory health, meaning people with preexisting asthma and COPD are at risk for exacerbations, and probably for respiratory tract infections as well.” He said, “It’s a little less clear, but there’s good biological plausibility for increased risk of respiratory tract infections because when your alveolar macrophages are overloaded with carbon particles that are toxic to those cells, they don’t function as well as a first line of defense against bacterial infection, for example.”

The new normal of wildfires

Warmer, drier summers in recent years in the western United States and many other regions, attributed by climate experts to global climate change, have produced catastrophic wildfires (PNAS;2016 Oct 18;113[42]11770-5; Science 2006 Aug 18;313:940-3). The Camp Fire in Northern California broke out in November 2018, took the lives of at least 85 people, and cost more than $16 billion in damage. Smoke from that blaze reached hazardous levels in San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, and many other smaller towns. Other forest fires in that year caused heavy smoke conditions in Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, and Anchorage. Such events are expected to be repeated often in the coming years (Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 6;16[13]).

Wildfire smoke can contain a wide range of substances, chemicals, and gases with known and unknown cardiorespiratory implications. “Smoke is composed primarily of carbon dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, hydrocarbons and other organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides, trace minerals and several thousand other compounds,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Wildfire smoke: A guide for public health officials 2019. Washington, D.C.: EPA, 2019). The EPA report noted, “Particles with diameters less than 10 mcm (particulate matter, or PM10) can be inhaled into the lungs and affect the lungs, heart, and blood vessels. The smallest particles, those less than 2.5 mcm in diameter (PM2.5), are the greatest risk to public health because they can reach deep into the lungs and may even make it into the bloodstream.”

Research on health impact

In early June of 2008, Wayne Cascio, MD, awoke in his Greenville, N.C., home to the stench of smoke emanating from a large peat fire burning some 65 miles away. By the time he reached the parking lot at East Carolina University in Greenville to begin his workday as chief of cardiology, the haze of smoke had thickened to the point where he could only see a few feet in front of him.

Over the next several weeks, the fire scorched 41,000 acres and produced haze and air pollution that far exceeded National Ambient Air Quality Standards for particulate matter and blanketed rural communities in the state’s eastern region. The price tag for management of the blaze reached $20 million. Because of his interest in the health effects of wildfire smoke and because of his relationship with investigators at the EPA, Dr. Cascio initiated an epidemiology study to investigate the effects of exposure on cardiorespiratory outcomes in the population affected by the fire (Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Oct;119[10]:1415-20).

By combining satellite data with syndromic surveillance drawn from hospital records in 41 counties contained in the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool, he and his colleagues found that exposure to the peat wildfire smoke led to increases in the cumulative risk ratio for asthma (relative risk, 1.65), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (RR, 1.73), and pneumonia and acute bronchitis (RR, 1.59). ED visits related to cardiopulmonary symptoms and heart failure also were significantly increased (RR, 1.23 and 1.37, respectively). “That was really the first study to strongly identify a cardiac endpoint related to wildfire smoke exposure,” said Dr. Cascio, who now directs the EPA’s National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It really pointed out how little we knew about the health effects of wildfire up until that time.”

Those early findings have been replicated in subsequent research about the acute health effects of exposure to wildfire smoke, which contains PM2.5 and other toxic substances from structures, electronic devices, and automobiles destroyed in the path of flames, including heavy metals and asbestos. Most of the work has focused on smoke-related cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits and hospitalizations.

A study of the 2008 California wildfire impact on ED visits accounted for ozone levels in addition to PM2.5 in the smoke. During the active fire periods, PM2.5 was significantly associated with exacerbations of asthma and COPD and these effects remained after controlling for ozone levels. PM2.5 inhalation during the wildfires was associated with increased risk of an ED visit for asthma (RR, 1.112; 95% confidence interval, 1.087-1.138) for a 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 and COPD (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.019-1.0825), as well as for combined respiratory visits (RR, 1.035; 95% CI, 1.023-1.046) (Environ Int. 2109 Aug;129:291-8).

Researchers who evaluated the health impacts of wildfires in California during the 2015 fire season found an increase in all-cause cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits, especially among those aged 65 years and older during smoke days. The population-based study included 1,196,233 ED visits during May 1–Sept. 30 that year. PM2.5 concentrations were categorized as light, medium, or dense. Relative risk rose with the amount of smoke in the air. Rates of all-cause cardiovascular ED visits were elevated across levels of smoke density, with the greatest increase on dense smoke days and among those aged 65 years or older (RR,1.15; 95% CI, 1.09-1.22). All-cause cerebrovascular visits were associated with dense smoke days, especially among those aged 65 years and older (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00-1.49). Respiratory conditions also were increased on dense smoke days (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28) (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Apr 11;7:e007492. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007492).

Long-term effects unknown

When it comes to the long-term effects of wildfire smoke on human health outcomes, much less is known. In a recent literature review, Colleen E. Reid, PhD, and Melissa May Maestas, PhD, found only one study that investigated long-term respiratory health impacts of wildfire smoke, and only a few studies that have estimated future health impacts of wildfires under likely climate change scenarios (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019 Mar;25:179-87).

“We know that there are immediate respiratory health effects from wildfire smoke,” said Dr. Reid of the department of geography at the University of Colorado Boulder. “What’s less known is everything else. That’s challenging, because people want to know about the long-term health effects.”

Evidence from the scientific literature suggests that exposure to air pollution adversely affects cardiovascular health, but whether exposure to wildfire smoke confers a similar risk is less clear. “Until just a few years ago we haven’t been able to study wildfire exposure measures on a large scale,” said EPA scientist Ana G. Rappold, PhD, a statistician there in the environmental public health division of the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It’s also hard to predict wildfires, so it’s hard to plan for an epidemiologic study if you don’t know where they’re going to occur.”

Dr. Rappold and colleagues examined cardiopulmonary hospitalizations among adults aged 65 years and older in 692 U.S. counties within 200 km of 123 large wildfires during 2008-2010 (Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127[3]:37006. doi: 10.1289/EHP3860). They observed that an increased risk of PM2.5-related cardiopulmonary hospitalizations was similar on smoke and nonsmoke days across multiple lags and exposure metrics, while risk for asthma-related hospitalizations was higher during smoke days. “One hypothesis is that this was an older study population, so naturally if you’re inhaling smoke, the first organ that’s impacted in an older population is the lungs,” Dr. Rappold said. “If you go to the hospital for asthma, wheezing, or bronchitis, you are taken out of the risk pool for cardiovascular and other diseases. That could explain why in other studies we don’t see a clear cardiovascular signal as we have for air pollution studies in general. Another aspect to this study is, the exposure metric was PM2.5, but smoke contains many other components, particularly gases, which are respiratory irritants. It could be that this triggers a higher risk for respiratory [effects] than regular episodes of high PM2.5 exposure, just because of the additional gases that people are exposed to.”

Another complicating factor is the paucity of data about solutions to long-term exposure to wildfire smoke. “If you’re impacted by high-exposure levels for 60 days, that is not something we have experienced before,” Dr. Rappold noted. “What are the solutions for that community? What works? Can we show that by implementing community-level resilience plans with HEPA [high-efficiency particulate air] filters or other interventions, do the overall outcomes improve? Doctors are the first ones to talk with their patients about their symptoms and about how to take care of their conditions. They can clearly make a difference in emphasizing reducing exposures in a way that fits their patients individually, either reducing the amount of time spent outside, the duration of exposure, and the level of exposure. Maybe change activities based on the intensity of exposure. Don’t go for a run outside when it’s smoky, because your ventilation rate is higher and you will breathe in more smoke. Become aware of those things.”

Advising vulnerable patients

While research in this field advances, the unforgiving wildfire season looms, assuring more destruction of property and threats to cardiorespiratory health. “There are a lot of questions that research will have an opportunity to address as we go forward, including the utility and the benefit of N95 masks, the utility of HEPA filters used in the house, and even with HVAC [heating, ventilation, and air conditioning] systems,” Dr. Cascio said. “Can we really clean up the indoor air well enough to protect us from wildfire smoke?”

The way he sees it, the time is ripe for clinicians and officials in public and private practice settings to refine how they distribute information to people living in areas affected by wildfire smoke. “We can’t force people do anything, but at least if they’re informed, then they understand they can make an informed decision about how they might want to affect what they do that would limit their exposure,” he said. “As a patient, my health care system sends text and email messages to me. So, why couldn’t the hospital send out a text message or an email to all of the patients with COPD, coronary disease, and heart failure when an area is impacted by smoke, saying, ‘Check your air quality and take action if air quality is poor?’ Physicians don’t have time to do this kind of education in the office for all of their patients. I know that from experience. But if one were to only focus on those at highest risk, and encourage them to follow our guidelines, which might include doing HEPA filter treatment in the home, we probably would reduce the number of clinical events in a cost-effective way.”

The 2019 wildfire season is underway in many locales across the United States, exposing millions of individuals to smoky conditions that will have health consequences ranging from stinging eyes to scratchy throats to a trip to the ED for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation. Questions about long-term health impacts are on the minds of many, including physicians and their patients who live with cardiorespiratory conditions.

John R. Balmes, MD, a pulmonologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the respiratory and cardiovascular effects of air pollutants, suggested that the best available published literature points to “pretty strong evidence for acute effects of wildfire smoke on respiratory health, meaning people with preexisting asthma and COPD are at risk for exacerbations, and probably for respiratory tract infections as well.” He said, “It’s a little less clear, but there’s good biological plausibility for increased risk of respiratory tract infections because when your alveolar macrophages are overloaded with carbon particles that are toxic to those cells, they don’t function as well as a first line of defense against bacterial infection, for example.”

The new normal of wildfires

Warmer, drier summers in recent years in the western United States and many other regions, attributed by climate experts to global climate change, have produced catastrophic wildfires (PNAS;2016 Oct 18;113[42]11770-5; Science 2006 Aug 18;313:940-3). The Camp Fire in Northern California broke out in November 2018, took the lives of at least 85 people, and cost more than $16 billion in damage. Smoke from that blaze reached hazardous levels in San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, and many other smaller towns. Other forest fires in that year caused heavy smoke conditions in Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, and Anchorage. Such events are expected to be repeated often in the coming years (Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 6;16[13]).

Wildfire smoke can contain a wide range of substances, chemicals, and gases with known and unknown cardiorespiratory implications. “Smoke is composed primarily of carbon dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, hydrocarbons and other organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides, trace minerals and several thousand other compounds,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Wildfire smoke: A guide for public health officials 2019. Washington, D.C.: EPA, 2019). The EPA report noted, “Particles with diameters less than 10 mcm (particulate matter, or PM10) can be inhaled into the lungs and affect the lungs, heart, and blood vessels. The smallest particles, those less than 2.5 mcm in diameter (PM2.5), are the greatest risk to public health because they can reach deep into the lungs and may even make it into the bloodstream.”

Research on health impact

In early June of 2008, Wayne Cascio, MD, awoke in his Greenville, N.C., home to the stench of smoke emanating from a large peat fire burning some 65 miles away. By the time he reached the parking lot at East Carolina University in Greenville to begin his workday as chief of cardiology, the haze of smoke had thickened to the point where he could only see a few feet in front of him.

Over the next several weeks, the fire scorched 41,000 acres and produced haze and air pollution that far exceeded National Ambient Air Quality Standards for particulate matter and blanketed rural communities in the state’s eastern region. The price tag for management of the blaze reached $20 million. Because of his interest in the health effects of wildfire smoke and because of his relationship with investigators at the EPA, Dr. Cascio initiated an epidemiology study to investigate the effects of exposure on cardiorespiratory outcomes in the population affected by the fire (Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Oct;119[10]:1415-20).

By combining satellite data with syndromic surveillance drawn from hospital records in 41 counties contained in the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool, he and his colleagues found that exposure to the peat wildfire smoke led to increases in the cumulative risk ratio for asthma (relative risk, 1.65), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (RR, 1.73), and pneumonia and acute bronchitis (RR, 1.59). ED visits related to cardiopulmonary symptoms and heart failure also were significantly increased (RR, 1.23 and 1.37, respectively). “That was really the first study to strongly identify a cardiac endpoint related to wildfire smoke exposure,” said Dr. Cascio, who now directs the EPA’s National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It really pointed out how little we knew about the health effects of wildfire up until that time.”

Those early findings have been replicated in subsequent research about the acute health effects of exposure to wildfire smoke, which contains PM2.5 and other toxic substances from structures, electronic devices, and automobiles destroyed in the path of flames, including heavy metals and asbestos. Most of the work has focused on smoke-related cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits and hospitalizations.

A study of the 2008 California wildfire impact on ED visits accounted for ozone levels in addition to PM2.5 in the smoke. During the active fire periods, PM2.5 was significantly associated with exacerbations of asthma and COPD and these effects remained after controlling for ozone levels. PM2.5 inhalation during the wildfires was associated with increased risk of an ED visit for asthma (RR, 1.112; 95% confidence interval, 1.087-1.138) for a 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 and COPD (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.019-1.0825), as well as for combined respiratory visits (RR, 1.035; 95% CI, 1.023-1.046) (Environ Int. 2109 Aug;129:291-8).

Researchers who evaluated the health impacts of wildfires in California during the 2015 fire season found an increase in all-cause cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits, especially among those aged 65 years and older during smoke days. The population-based study included 1,196,233 ED visits during May 1–Sept. 30 that year. PM2.5 concentrations were categorized as light, medium, or dense. Relative risk rose with the amount of smoke in the air. Rates of all-cause cardiovascular ED visits were elevated across levels of smoke density, with the greatest increase on dense smoke days and among those aged 65 years or older (RR,1.15; 95% CI, 1.09-1.22). All-cause cerebrovascular visits were associated with dense smoke days, especially among those aged 65 years and older (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00-1.49). Respiratory conditions also were increased on dense smoke days (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28) (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Apr 11;7:e007492. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007492).

Long-term effects unknown

When it comes to the long-term effects of wildfire smoke on human health outcomes, much less is known. In a recent literature review, Colleen E. Reid, PhD, and Melissa May Maestas, PhD, found only one study that investigated long-term respiratory health impacts of wildfire smoke, and only a few studies that have estimated future health impacts of wildfires under likely climate change scenarios (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019 Mar;25:179-87).

“We know that there are immediate respiratory health effects from wildfire smoke,” said Dr. Reid of the department of geography at the University of Colorado Boulder. “What’s less known is everything else. That’s challenging, because people want to know about the long-term health effects.”

Evidence from the scientific literature suggests that exposure to air pollution adversely affects cardiovascular health, but whether exposure to wildfire smoke confers a similar risk is less clear. “Until just a few years ago we haven’t been able to study wildfire exposure measures on a large scale,” said EPA scientist Ana G. Rappold, PhD, a statistician there in the environmental public health division of the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It’s also hard to predict wildfires, so it’s hard to plan for an epidemiologic study if you don’t know where they’re going to occur.”

Dr. Rappold and colleagues examined cardiopulmonary hospitalizations among adults aged 65 years and older in 692 U.S. counties within 200 km of 123 large wildfires during 2008-2010 (Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127[3]:37006. doi: 10.1289/EHP3860). They observed that an increased risk of PM2.5-related cardiopulmonary hospitalizations was similar on smoke and nonsmoke days across multiple lags and exposure metrics, while risk for asthma-related hospitalizations was higher during smoke days. “One hypothesis is that this was an older study population, so naturally if you’re inhaling smoke, the first organ that’s impacted in an older population is the lungs,” Dr. Rappold said. “If you go to the hospital for asthma, wheezing, or bronchitis, you are taken out of the risk pool for cardiovascular and other diseases. That could explain why in other studies we don’t see a clear cardiovascular signal as we have for air pollution studies in general. Another aspect to this study is, the exposure metric was PM2.5, but smoke contains many other components, particularly gases, which are respiratory irritants. It could be that this triggers a higher risk for respiratory [effects] than regular episodes of high PM2.5 exposure, just because of the additional gases that people are exposed to.”