User login

Cancer Data Trends 2024: B-Cell Lymphoma

Lu W, Chen W, Zhou Y, et al. A model to predict the prognosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma based on ultrasound images. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3346. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-30533-y

Leukemia - Chronic lymphocytic - CLL: statistics. Cancer.net. Published February 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/leukemia-chronic-lymphocytic-cll/statistics

Harmanen M, Hujo M, Sund R, et al. Survival of patients with mantle cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: retrospective binational analysis between 2000 and 2020. Br J Haematol. 2023;201(1):64-74. doi:10.1111/bjh.18597

Romancik JT, Cohen JB. Management of older adults with mantle cell lymphoma. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(7):469-481. doi:10.1007/s40266-020-00765-y

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL). Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.lls.org/research/marginal-zone-lymphoma-mzl

Understanding lymphoma: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lymphoma Research Foundation fact sheet. Updated 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024 https://lymphoma.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/LRF_Understanding_Lymphoma_Diffuse_Large_B_Cell_Lymphoma_Fact_Sheet.pdf

Key statistics for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. American Cancer Society. Updated January 17, 2024. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/non-hodgkin-lymphoma/about/key-statistics.html

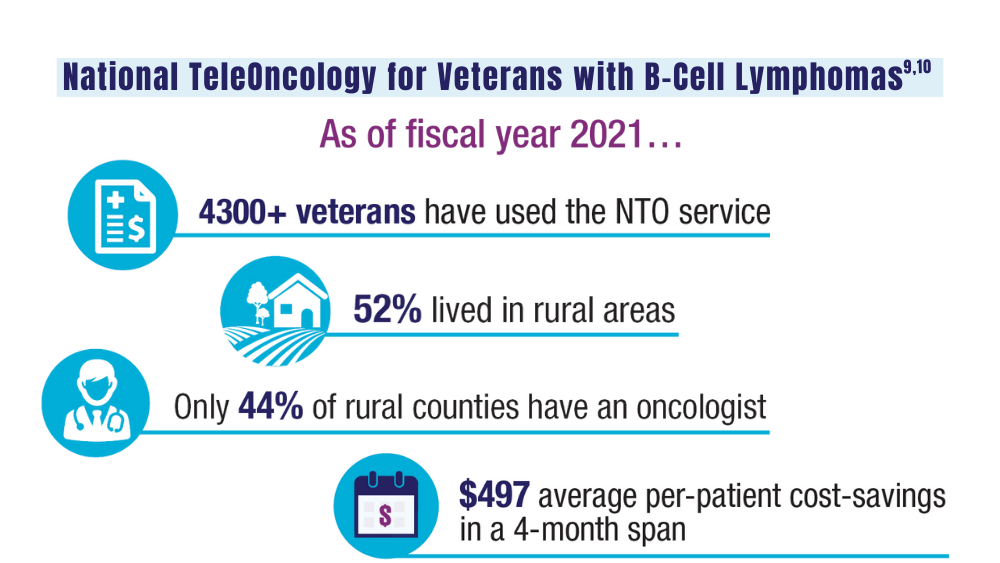

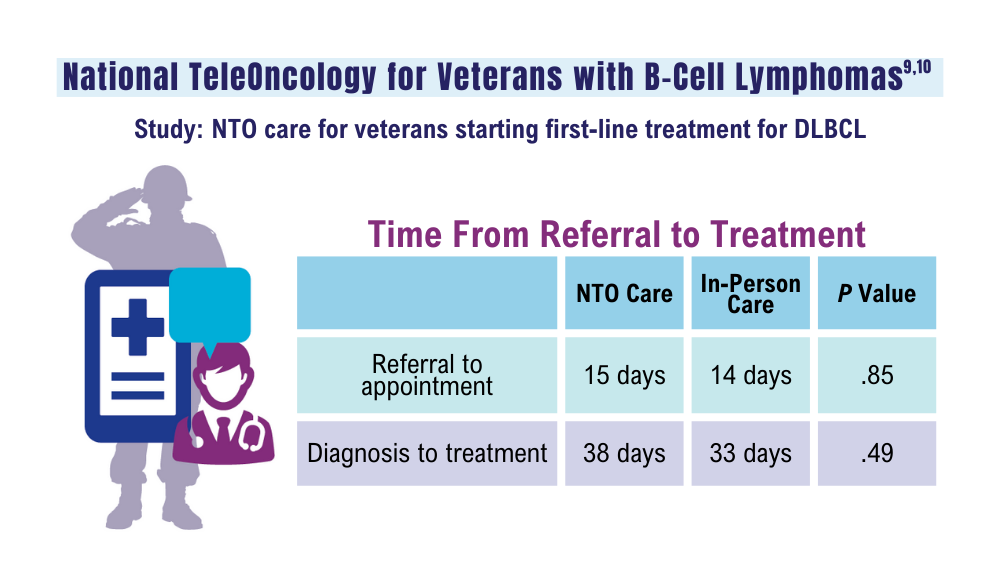

Zullig LL, Raska W, McWhirter G, et al. Veterans Health Administration National TeleOncology Service. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(4):e504-e510. doi:10.1200/OP.22.00455

Lin C, Zhou KI, Burningham ZR, et al. Telemedicine-supervised cancer therapy for patients with an aggressive lymphoma and metastatic lung cancer in the U.S. Veterans Affairs National TeleOncology Service. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 suppl)16:Abstract 1602. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1602

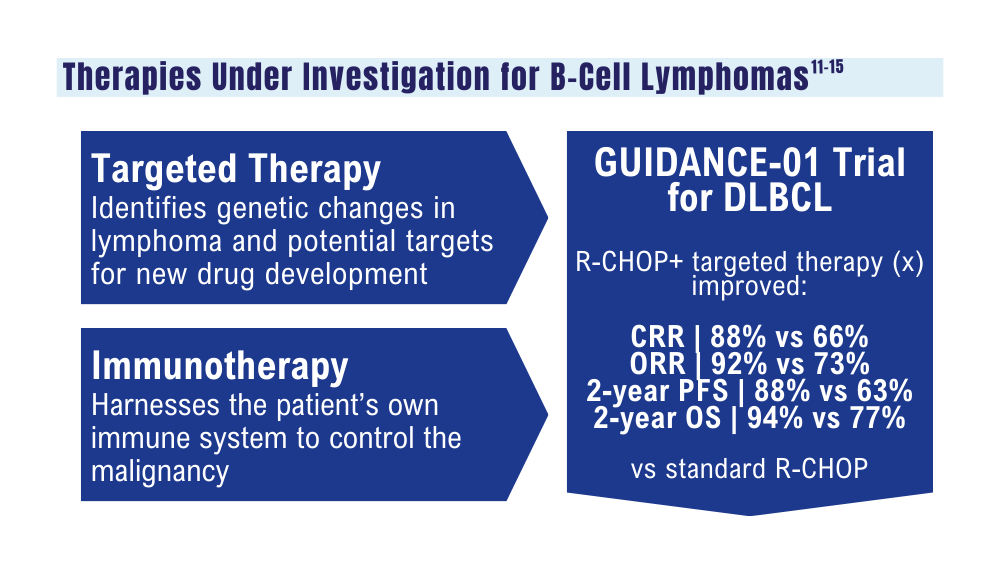

Zhang MC, Tian S, Fu D, et al. Genetic subtype-guided immunochemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the randomized GUIDANCE-01 trial. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(10):1705-1716.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2023.09.004

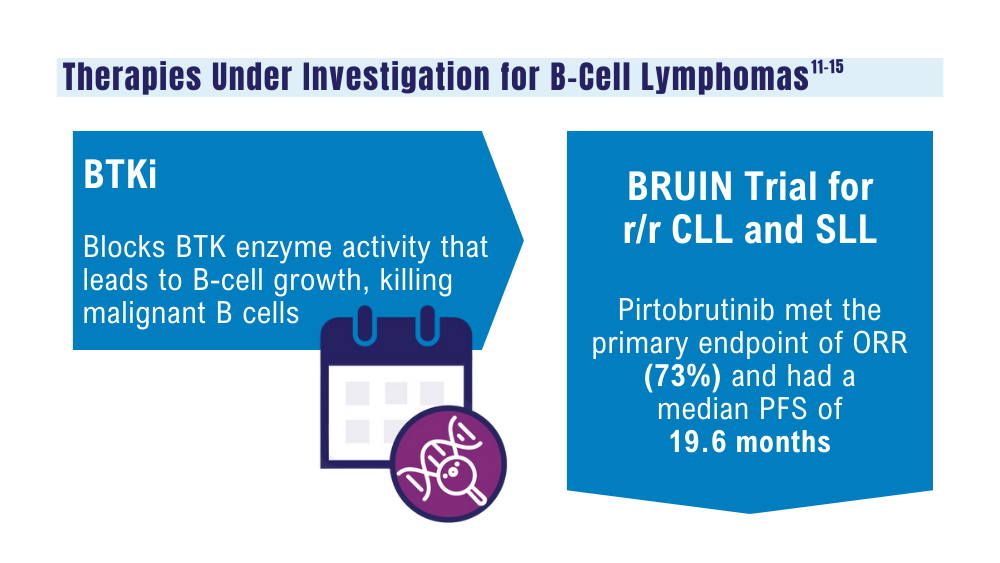

Mato AR, Woyach JA, Brown JR, et al. Pirtobrutinib after a covalent BTK inhibitor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(1):33-44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2300696

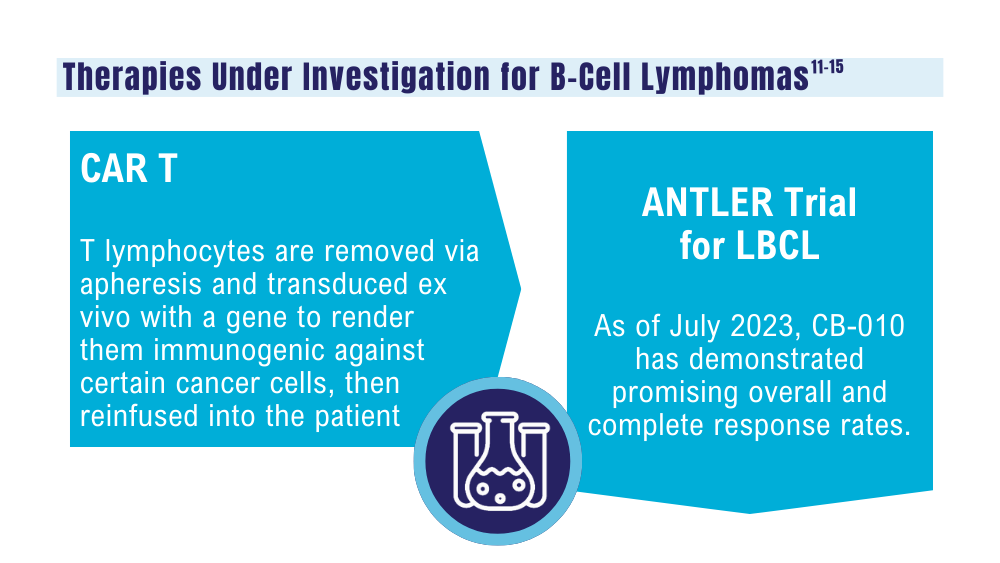

Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(4):69. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7

Caribou Biosciences reports positive clinical data from dose escalation of CB-010 ANTLER phase 1 trial in r/r B-NHL [news release]. Globalnewswire.com. Published July 13, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2023/07/13/2704702/0/en/Caribou-Biosciences-Reports-Positive-Clinical-Data-from-Dose-Escalation-of-CB-010-ANTLER-Phase-1-Trial-in-r-r-B-NHL.html

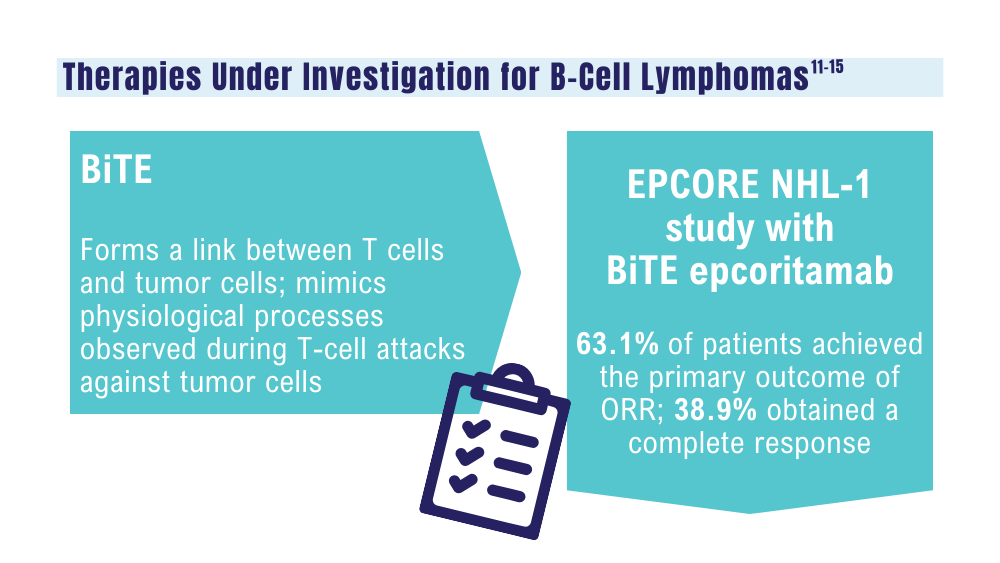

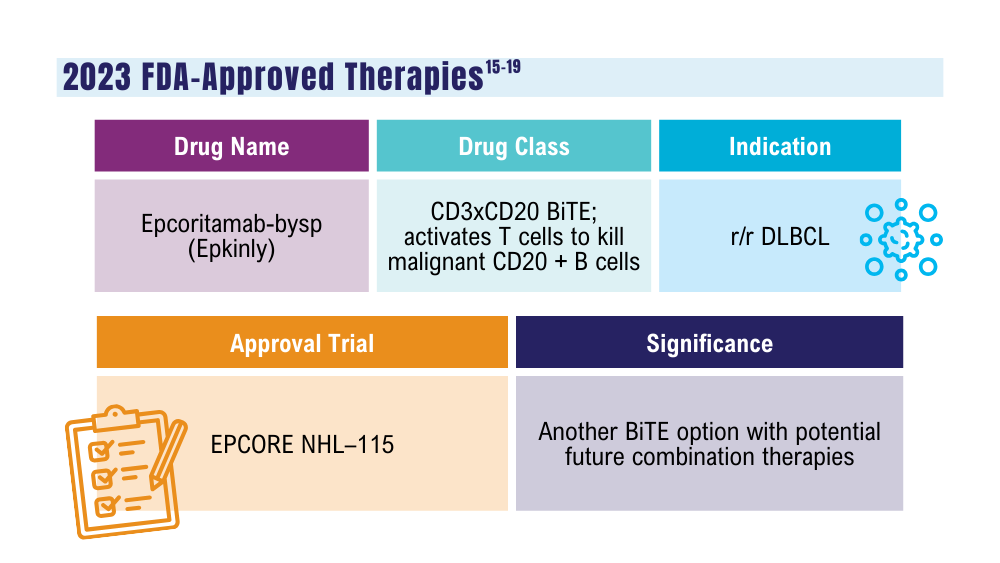

Ma J, Mo Y, Tang M, et al. Bispecific antibodies: from research to clinical application. Front Immunol. 2021;12:626616. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.626616

Davis JA, Granger K, Sakowski A, et al. Dual target dilemma: navigating epcoritamab vs. glofitamab in relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023;16(12):915-918. doi:10.1080/17474086.2023.2285978

Lynch RC, Poh C, Ujjani CS, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin with infusional chemotherapy for untreated aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood Adv. 2023;7(11):2449-2458. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2022009145

Thompson PA, Tam CS. Pirtobrutinib: a new hope for patients with BTK inhibitor-refractory lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2023;141(26):3137-3142. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020240

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves zanubrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Published January 19, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-zanubrutinib-chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia-or-small-lymphocytic-lymphoma

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to glofitamab-gxbm for selected relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas. Published June 16, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-glofitamab-gxbm-selected-relapsed-or-refractory-large-b-cell

Lu W, Chen W, Zhou Y, et al. A model to predict the prognosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma based on ultrasound images. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3346. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-30533-y

Leukemia - Chronic lymphocytic - CLL: statistics. Cancer.net. Published February 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/leukemia-chronic-lymphocytic-cll/statistics

Harmanen M, Hujo M, Sund R, et al. Survival of patients with mantle cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: retrospective binational analysis between 2000 and 2020. Br J Haematol. 2023;201(1):64-74. doi:10.1111/bjh.18597

Romancik JT, Cohen JB. Management of older adults with mantle cell lymphoma. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(7):469-481. doi:10.1007/s40266-020-00765-y

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL). Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.lls.org/research/marginal-zone-lymphoma-mzl

Understanding lymphoma: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lymphoma Research Foundation fact sheet. Updated 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024 https://lymphoma.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/LRF_Understanding_Lymphoma_Diffuse_Large_B_Cell_Lymphoma_Fact_Sheet.pdf

Key statistics for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. American Cancer Society. Updated January 17, 2024. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/non-hodgkin-lymphoma/about/key-statistics.html

Zullig LL, Raska W, McWhirter G, et al. Veterans Health Administration National TeleOncology Service. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(4):e504-e510. doi:10.1200/OP.22.00455

Lin C, Zhou KI, Burningham ZR, et al. Telemedicine-supervised cancer therapy for patients with an aggressive lymphoma and metastatic lung cancer in the U.S. Veterans Affairs National TeleOncology Service. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 suppl)16:Abstract 1602. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1602

Zhang MC, Tian S, Fu D, et al. Genetic subtype-guided immunochemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the randomized GUIDANCE-01 trial. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(10):1705-1716.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2023.09.004

Mato AR, Woyach JA, Brown JR, et al. Pirtobrutinib after a covalent BTK inhibitor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(1):33-44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2300696

Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(4):69. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7

Caribou Biosciences reports positive clinical data from dose escalation of CB-010 ANTLER phase 1 trial in r/r B-NHL [news release]. Globalnewswire.com. Published July 13, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2023/07/13/2704702/0/en/Caribou-Biosciences-Reports-Positive-Clinical-Data-from-Dose-Escalation-of-CB-010-ANTLER-Phase-1-Trial-in-r-r-B-NHL.html

Ma J, Mo Y, Tang M, et al. Bispecific antibodies: from research to clinical application. Front Immunol. 2021;12:626616. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.626616

Davis JA, Granger K, Sakowski A, et al. Dual target dilemma: navigating epcoritamab vs. glofitamab in relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023;16(12):915-918. doi:10.1080/17474086.2023.2285978

Lynch RC, Poh C, Ujjani CS, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin with infusional chemotherapy for untreated aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood Adv. 2023;7(11):2449-2458. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2022009145

Thompson PA, Tam CS. Pirtobrutinib: a new hope for patients with BTK inhibitor-refractory lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2023;141(26):3137-3142. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020240

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves zanubrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Published January 19, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-zanubrutinib-chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia-or-small-lymphocytic-lymphoma

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to glofitamab-gxbm for selected relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas. Published June 16, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-glofitamab-gxbm-selected-relapsed-or-refractory-large-b-cell

Lu W, Chen W, Zhou Y, et al. A model to predict the prognosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma based on ultrasound images. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3346. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-30533-y

Leukemia - Chronic lymphocytic - CLL: statistics. Cancer.net. Published February 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/leukemia-chronic-lymphocytic-cll/statistics

Harmanen M, Hujo M, Sund R, et al. Survival of patients with mantle cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: retrospective binational analysis between 2000 and 2020. Br J Haematol. 2023;201(1):64-74. doi:10.1111/bjh.18597

Romancik JT, Cohen JB. Management of older adults with mantle cell lymphoma. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(7):469-481. doi:10.1007/s40266-020-00765-y

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL). Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.lls.org/research/marginal-zone-lymphoma-mzl

Understanding lymphoma: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lymphoma Research Foundation fact sheet. Updated 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024 https://lymphoma.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/LRF_Understanding_Lymphoma_Diffuse_Large_B_Cell_Lymphoma_Fact_Sheet.pdf

Key statistics for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. American Cancer Society. Updated January 17, 2024. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/non-hodgkin-lymphoma/about/key-statistics.html

Zullig LL, Raska W, McWhirter G, et al. Veterans Health Administration National TeleOncology Service. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(4):e504-e510. doi:10.1200/OP.22.00455

Lin C, Zhou KI, Burningham ZR, et al. Telemedicine-supervised cancer therapy for patients with an aggressive lymphoma and metastatic lung cancer in the U.S. Veterans Affairs National TeleOncology Service. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 suppl)16:Abstract 1602. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.1602

Zhang MC, Tian S, Fu D, et al. Genetic subtype-guided immunochemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the randomized GUIDANCE-01 trial. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(10):1705-1716.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2023.09.004

Mato AR, Woyach JA, Brown JR, et al. Pirtobrutinib after a covalent BTK inhibitor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(1):33-44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2300696

Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(4):69. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7

Caribou Biosciences reports positive clinical data from dose escalation of CB-010 ANTLER phase 1 trial in r/r B-NHL [news release]. Globalnewswire.com. Published July 13, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2023/07/13/2704702/0/en/Caribou-Biosciences-Reports-Positive-Clinical-Data-from-Dose-Escalation-of-CB-010-ANTLER-Phase-1-Trial-in-r-r-B-NHL.html

Ma J, Mo Y, Tang M, et al. Bispecific antibodies: from research to clinical application. Front Immunol. 2021;12:626616. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.626616

Davis JA, Granger K, Sakowski A, et al. Dual target dilemma: navigating epcoritamab vs. glofitamab in relapsed refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023;16(12):915-918. doi:10.1080/17474086.2023.2285978

Lynch RC, Poh C, Ujjani CS, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin with infusional chemotherapy for untreated aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood Adv. 2023;7(11):2449-2458. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2022009145

Thompson PA, Tam CS. Pirtobrutinib: a new hope for patients with BTK inhibitor-refractory lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2023;141(26):3137-3142. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020240

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves zanubrutinib for chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Published January 19, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-zanubrutinib-chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia-or-small-lymphocytic-lymphoma

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to glofitamab-gxbm for selected relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas. Published June 16, 2023. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-glofitamab-gxbm-selected-relapsed-or-refractory-large-b-cell

CDC Study Links Camp Lejeune Contaminated Water to Range of Cancers

For years, people living and working at Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, N.C., drank and showered in water contaminated with trichloroethylene (TCE) and other industrial solvents. Now, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study has determined that the exposure markedly increased their risk for certain cancers.

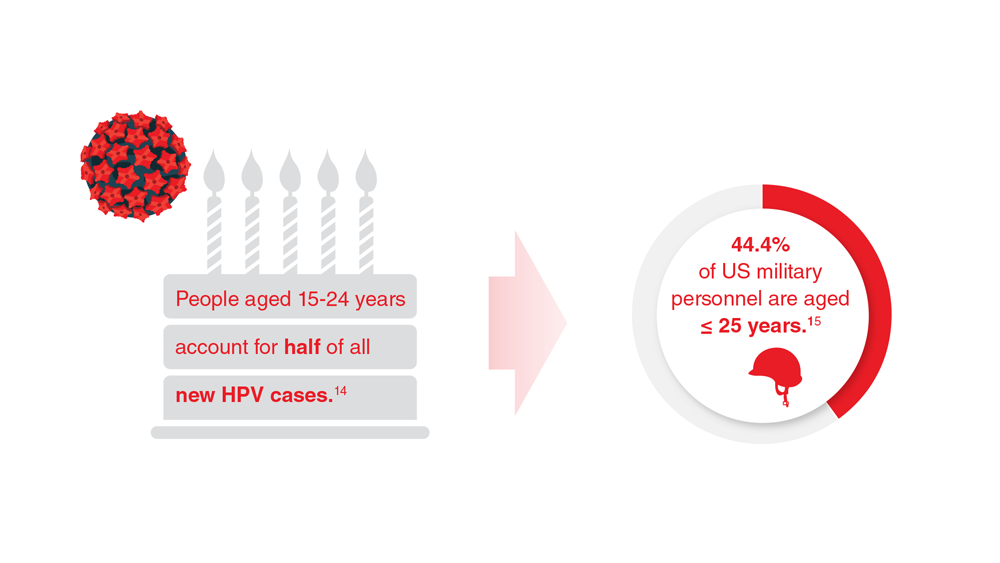

In one of the largest cohort cancer incidence studies ever completed in the US, researchers compared cancer risk between 161,315 military personnel and civilian workers at Camp Lejeune and 169,281 military personnel and civilian workers at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, Calif., where the water was not contaminated.

Data from diagnoses between 1996 and 2017 documented 12,083 cancers among Camp Lejeune Marine and Navy personnel and 1,563 among civilian workers. By comparison, 12,144 cancers were documented among Camp Pendleton personnel and 1,372 among civilian workers. However, personnel stationed at Camp Lejeune between 1975 and 1985 had at least a 20% higher risk for all myeloid cancers including polycythemia vera, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative syndromes, and cancers of the esophagus, larynx, soft tissue, and thyroid. Civilian workers had a higher risk for all myeloid cancers, squamous cell lung cancer, and female ductal breast cancer.

The water exposures included contributions to total internal body dose from 3 routes: ingestion, inhalation, and dermal. The researchers note that a Marine in training may consume as much as 6 liters a day of drinking water, but the combined dose from inhalation and dermal routes could be as high or higher than that from ingestion. For example, they note that an internal dose via inhalation to TCE during a 10-minute shower could equal the internal dose via ingestion of 2 liters of contaminated drinking water.

Health risks at Camp Lejeune have been studied before, but this study “more fully establishes the scope,” Richard Clapp, a Boston University emeritus public health professor, told the Associated Press.

For years, people living and working at Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, N.C., drank and showered in water contaminated with trichloroethylene (TCE) and other industrial solvents. Now, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study has determined that the exposure markedly increased their risk for certain cancers.

In one of the largest cohort cancer incidence studies ever completed in the US, researchers compared cancer risk between 161,315 military personnel and civilian workers at Camp Lejeune and 169,281 military personnel and civilian workers at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, Calif., where the water was not contaminated.

Data from diagnoses between 1996 and 2017 documented 12,083 cancers among Camp Lejeune Marine and Navy personnel and 1,563 among civilian workers. By comparison, 12,144 cancers were documented among Camp Pendleton personnel and 1,372 among civilian workers. However, personnel stationed at Camp Lejeune between 1975 and 1985 had at least a 20% higher risk for all myeloid cancers including polycythemia vera, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative syndromes, and cancers of the esophagus, larynx, soft tissue, and thyroid. Civilian workers had a higher risk for all myeloid cancers, squamous cell lung cancer, and female ductal breast cancer.

The water exposures included contributions to total internal body dose from 3 routes: ingestion, inhalation, and dermal. The researchers note that a Marine in training may consume as much as 6 liters a day of drinking water, but the combined dose from inhalation and dermal routes could be as high or higher than that from ingestion. For example, they note that an internal dose via inhalation to TCE during a 10-minute shower could equal the internal dose via ingestion of 2 liters of contaminated drinking water.

Health risks at Camp Lejeune have been studied before, but this study “more fully establishes the scope,” Richard Clapp, a Boston University emeritus public health professor, told the Associated Press.

For years, people living and working at Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, N.C., drank and showered in water contaminated with trichloroethylene (TCE) and other industrial solvents. Now, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study has determined that the exposure markedly increased their risk for certain cancers.

In one of the largest cohort cancer incidence studies ever completed in the US, researchers compared cancer risk between 161,315 military personnel and civilian workers at Camp Lejeune and 169,281 military personnel and civilian workers at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, Calif., where the water was not contaminated.

Data from diagnoses between 1996 and 2017 documented 12,083 cancers among Camp Lejeune Marine and Navy personnel and 1,563 among civilian workers. By comparison, 12,144 cancers were documented among Camp Pendleton personnel and 1,372 among civilian workers. However, personnel stationed at Camp Lejeune between 1975 and 1985 had at least a 20% higher risk for all myeloid cancers including polycythemia vera, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative syndromes, and cancers of the esophagus, larynx, soft tissue, and thyroid. Civilian workers had a higher risk for all myeloid cancers, squamous cell lung cancer, and female ductal breast cancer.

The water exposures included contributions to total internal body dose from 3 routes: ingestion, inhalation, and dermal. The researchers note that a Marine in training may consume as much as 6 liters a day of drinking water, but the combined dose from inhalation and dermal routes could be as high or higher than that from ingestion. For example, they note that an internal dose via inhalation to TCE during a 10-minute shower could equal the internal dose via ingestion of 2 liters of contaminated drinking water.

Health risks at Camp Lejeune have been studied before, but this study “more fully establishes the scope,” Richard Clapp, a Boston University emeritus public health professor, told the Associated Press.

Preventing ASCVD Events: Using Coronary Artery Calcification Scores to Personalize Risk and Guide Statin Therapy

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer mortality, and cigarette smoking is the most significant risk factor. Several randomized clinical trials have shown that lung cancer screening (LCS) with nonelectrocardiogram (ECG)-gated low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces both lung cancer and all-cause mortality.1,2 Hence, the US Preventive Screening Task Force (USPSTF) recommends annual screening with LDCT in adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.3

Smoking is also an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), and LCS clinical trials acknowledge that mortality from ASCVD events exceeds that of lung cancer.4,5 In an analysis of asymptomatic individuals from the Framingham Heart Offspring study who were eligible for LCS, the ASCVD event rate during a median (IQR) follow-up of 11.4 (9.7-12.0) years was 12.6%.6 However, despite the high rate of ASCVD events in this population, primary prevention strategies are consistently underused. In a study of 5495 individuals who underwent LCS with LDCT, only 40% of those eligible for statins had one prescribed, underscoring the missed opportunity for preventing ASCVD events during LCS.7 Yet the interactions for shared decision making and the availability of coronary artery calcification (CAC) scores from the LDCT provide an ideal window for intervening and preventing ASCVD events during LCS.

CAC is a hallmark of atherosclerotic plaque development and is proportional to plaque burden and ASCVD risk.8 Because of the relationship between CAC, subclinical atherosclerosis, and ASCVD risk, there is an opportunity to use CAC detected by LDCT to predict ASCVD risk and guide recommendations for statin treatment in individuals enrolled in LCS. Traditionally, CAC has been visualized by ECG-gated noncontrast CT scans with imaging protocols specifically designed to visualize the coronary arteries, minimize motion artifacts, and reduce signal noise. These scans are specifically done for primary prevention risk assessment and report an Agatston score, a summed measure based on calcified plaque area and maximal density.9 Results are reported as an overall CAC score and an age-, sex-, and race-adjusted percentile of CAC. Currently, a CAC score ≥ 100 or above the 75th percentile for age, sex, and race is considered abnormal.

High-quality evidence supports CAC scores as a strong predictor of ASCVD risk independent of age, sex, race, and other traditional risk factors.10-12 In asymptomatic individuals, a CAC score of 0 is a strong, negative risk factor associated with very low annualized mortality rates and cardiovascular (CV) events, so intermediate-risk individuals can be reclassified to a lower risk group avoiding or delaying statin therapy.13 As a result, current primary prevention guidelines allow for CAC scoring in asymptomatic, intermediate-risk adults where the clinical benefits of statin therapy are uncertain, knowing the CAC score will aid in the clinical decision to delay or initiate statin therapy.

Unlike traditional ECG-gated CAC scoring, LDCT imaging protocols are non–ECG-gated and performed at variable energy and slice thickness to optimize the detection of lung nodules. Early studies suggested that CAC detected by LDCT could be used in lieu of traditional CAC scoring to personalize risk.14,15 Recently, multiple studies have validated the accuracy and reproducibility of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC. In both the NELSON and the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) LCS trials, higher visual and quantitative measures of CAC were independently and incrementally associated with ASCVD risk.16,17 A subsequent review and meta-analysis of 6 LCS trials confirmed CAC detected by LDCT to be an independent predictor of ASCVD events regardless of the method used to measure CAC.18

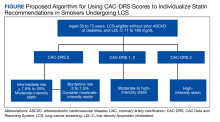

There is now consensus that either an Agatston score or a visual estimate of CAC be reported on all noncontrast, noncardiac chest CT scans irrespective of the indication or technique, including LDCT scans for LCS using a uniform reporting system known as the Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS).19 The CAC-DRS simplifies reporting and adds modifiers indicating if the reported score is visual (V) or Agatston (A) and number of vessels involved. For example, CAC-DRS A0 or CAC-DRS V0 would indicate an Agatston score of 0 or a visual score of 0. CAC-DRS A1/N2 would indicate a total Agatston score of 1-99 in 2 coronary arteries. The currently agreed-on CAC-DRS risk groups are listed in the Table, along with their corresponding visual score or Agatston score and anticipated 10-year event rate, irrespective of other risk factors.20

As LCS efforts increase, primary care practitioners will receive LDCT reports that now incorporate an estimation of CAC (visual or quantitative). Thus, it will be increasingly important to know how to interpret and use these scores to guide clinical decisions regarding the initiation of statin therapy, referral for additional testing, and when to seek specialty cardiology care. For instance, does the absence of CAC (CAC = 0) on LDCT predict a low enough risk for statin therapy to be delayed or withdrawn? Does increasing CAC scores on follow-up LDCT in individuals on statin therapy represent treatment failure? When should CAC scores trigger additional testing, such as a stress test or referral to cardiology specialty care?

Primary Prevention in LCS

The initial approach to primary prevention in LCS is no different from that recommended by the 2018 multisociety guidelines on the management of blood cholesterol, the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline on primary prevention, or the 2022 USPTSF recommendations on statin use for primary prevention of CV disease in adults.21-23 For a baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥ 190 mg/dL, high-intensity statin therapy is recommended without further risk stratification. Individuals with diabetes also are at higher-than-average risk, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended.

For individuals not in either group, a validated ASCVD risk assessment tool is recommended to estimate baseline risk. The most validated tool for estimating risk in the US population is the 2013 ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE) which provides an estimate of the 10-year risk for fatal and myocardial infarction and fatal and nonfatal stroke.24 The PCE risk calculator uses age, presence of diabetes, sex, smoking history, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and treatment for hypertension to place individuals into 1 of 4 risk groups: low (< 5%), borderline (5% to < 7.5%), intermediate (≥ 7.5% to < 20%), and high (≥ 20%). Clinicians should be aware that the PCE only considers current smoking history and not prior smoking history or cumulative pack-year history. This differs from eligibility for LCS where recent smoking plays a larger role. All these risk factors are important to consider when evaluating risk and discussing risk-reducing strategies like statin therapy.

The 2018 multisociety guidelines and the 2019 primary prevention guidelines set the threshold for considering initiation of statin therapy at intermediate risk ≥ 7.5%.21,22 The 2020 US Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines set the threshold for considering statin therapy at an estimated 10-year event rate of 12%, whereas the 2022 UPSTF recommendations set the threshold at 10% with additional risk factors as the threshold for statin therapy.23,25 The reasons for these differences are beyond the scope of this review, but all these guidelines use the PCE to estimate baseline risk as the starting point for clinical decision making.

The PCE was originally derived and validated in population studies dating to the 1960s when the importance of diet, exercise, and smoking cessation in reducing ASCVD events was not well appreciated. The application of the PCE in more contemporary populations shows that it overestimates risk, especially in older individuals and women.26,27 Overestimation of risk has the potential to result in the initiation of statin therapy in individuals in whom the actual clinical benefit would otherwise be small.

To address this issue, current guidelines allow the use of CAC scoring to refine risk in individuals who are classified as intermediate risk and who otherwise desire to avoid lifelong statin therapy. Using current recommendations, we make suggestions on how to use CAC scores from LDCT to aid in clinical decision making for individuals in LCS (Figure).

No Coronary Artery Calcification

Between 25% and 30% of LDCT done for LCS will show no CAC.14,16 In general population studies, a CAC score of 0 is a strong negative predictor when there are no other risk factors.13,28 In contrast, the negative predictive ability of a CAC score of 0 in individuals with a smoking history who are eligible for LCS is unproven. In multivariate modeling, a CAC score of 0 did not reduce the significant hazard of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or smokers.29 In an analysis of 44,042 individuals without known heart disease referred for CAC scoring, the frequency of a CAC score of 0 was only modestly lower in smokers (38%) compared with nonsmokers (42%), yet the all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher.30 In addition, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) participants who were current smokers or eligible for LCS and had a CAC score of 0 had an observed 11-year ASCVD event rate of 13.4% and 20.8%, respectively, leading to the conclusion that a CAC score of 0 may not be predictive of minimal risk in smokers and those eligible for LCS.31 Additionally, in LCS-eligible individuals, the PCE underestimated event rates and incorporation of CAC scores did not significantly improve risk estimation. Finally, data from the NLST screening trial showed that the absence of CAC on LDCT was not associated with better survival or lower CV mortality compared with individuals with low CAC scores.32

The question of whether individuals undergoing LCS with LDCT who have no detectable CAC can avoid statin therapy is an unresolved issue; no contemporary studies have looked specifically at the relationship between estimated risk, a CAC score of 0, and ASCVD outcomes in individuals participating in LCS. For these reasons, we recommend moderate-intensity statin therapy when the estimated risk is intermediate because it is unclear that either an Agatston score of 0 reclassifies intermediate-risk LCS-eligible individuals to a lower risk group.

For the few borderline risk (estimated risk, 5% to < 7.5%) LCS-eligible individuals, a CAC score of 0 might confer low short-term risk but the long-term benefit of statin therapy on reducing subsequent risk, the presence of other risk factors, and the willingness to stop smoking should all be considered. For these individuals who elect to avoid statin therapy, annual re-estimation of risk at the time of repeat LDCT is recommended. In these circumstances, referral for traditional Agatston scoring is not likely to change decision making because the sensitivity of the 2 techniques is very similar.

Agatston Score of 1-99 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 1

In general population studies, these scores correspond to borderline risk and an estimated 10-year event rate of just under 7.5%.20 In both the NELSON and NLST LCS trials, even low amounts of CAC regardless of the scoring method were associated with higher observed ASCVD mortality when adjusted for other baseline risk factors.32 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with intermediate and borderline risk, a CAC score between 1 and 99 or a visual estimate of 1 indicates the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is reasonable.

Agatston Score of 100-299 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 2

Across all ages, races, and sexes, CAC scores between 100 to 299 are associated with an event rate of about 15% over 10 years.20 In the NELSON LCS trial, the adjusted hazard ratio for ASCVD events with a nontraditional Agatston score of 101 to 400 was 6.58.33 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with a CAC score of 100 to 299, regardless of the baseline risk estimate, the projected absolute event rate at 10 years would be about 20%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended to reduce the baseline LDL-C by 30% to 49%.

Agatston Score of > 300 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 3

Agatston CAC scores > 300 are consistent with a 10-year incidence of ASCVD events of > 15% regardless of age, sex, or race and ethnicity.20 In the Calcium Consortium, a CAC > 400 was correlated with an event rate of 13.6 events/1000 person-years.12 In a Walter Reed Military Medical Center study, a CAC score > 400 projected a cumulative incidence of ASCVD events of nearly 20% at 10 years.34 In smokers eligible for LCS, a CAC score > 300 projected a 10-year ASCVD event rate of 25%.29 In these patients, moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended, although high-intensity statin therapy can be considered if there are other risk factors.

Agatston Score ≥ 1000

The 2018 consensus statement on CAC reporting categorizes all CAC scores > 300 into a single risk group because the recommended treatment options do not differ.19 However, recent data suggest this might not be the case since individuals with very high CAC scores experience high rates of events that might justify more aggressive intervention. In an analysis of individuals who participated in the CAC Consortium with a CAC score ≥ 1000, the all-cause mortality rate was 18.8 per 1000 person-years with a CV mortality rate of 8 per 1000 person-years.35 Individuals with very high levels of CAC > 1000 also have a greater number of diseased coronary arteries, higher involvement of the left main coronary artery, and significantly higher event rates compared with those with a CAC of 400 to 999.36 In an analysis of individuals from the NLST trial, nontraditionally measured Agatston score > 1000 was associated with a hazard ratio for coronary artery disease (CAD) mortality of 3.66 in men and 5.81 in women.17 These observed and projected levels of risk are like that seen in secondary prevention trials, and some experts have recommended the use of high-intensity statin therapy to reduce LDL-C to < 70 mg/dL.37

Primary Prevention in Individuals aged 76 to 80 years

LCS can continue through age 80 years, while the PCE and primary prevention guidelines are truncated at age 75 years. Because age is a major contributor to risk, many of these individuals will already be in the intermediate- to high-risk group. However, the net clinical benefit of statin therapy for primary prevention in this age group is not well established, and the few primary prevention trials in this group have not demonstrated net clinical benefit.38 As a result, current guidelines do not provide specific treatment recommendations for individuals aged > 75 years but recognize the value of shared decision making considering associated comorbidities, age-related risks of statin therapy, and the desires of the individual to avoid ASCVD-related events even if the net clinical benefit is low.

Older individuals with elevated CAC scores should be informed about the risk of ASCVD events and the potential but unproven benefit of moderate-intensity statin therapy. Older individuals with a CAC score of 0 likely have low short-term risk of ASCVD events and withholding statin therapy is not unreasonable.

CAC Scores on Annual LDCT Scans

Because LCS requires annual LDCT scans, primary care practitioners and patients need to understand the significance of changing CAC scores over time. For individuals not on statin therapy, increasing calcification is a marker of progression of subclinical atherosclerosis. Patients undergoing LCS not on statin who have progressive increases in their CAC should consider initiating statin therapy. Individuals who opted not to initiate statin therapy who subsequently develop CAC should be re-engaged in a discussion about the significance of the finding and the clinically proven benefits of statin therapy in individuals with subclinical atherosclerosis. These considerations do not apply to individuals already on statin therapy. Statins convert lipid-rich plaques to lipid-depleted plaques, resulting in increasing calcification. As a result, CAC scores do not decrease and may increase with statin therapy.39 Individuals participating in annual LCS should be informed of this possibility. Also, in these individuals, referral to specialty care as a treatment failure is not supported by the literature.

Furthermore, serial CAC scoring to titrate the intensity of statin therapy is not currently recommended. The goal with moderate-intensity statin therapy is a 30% to 49% reduction from baseline LDL-C. If this milestone is not achieved, the statin dose can be escalated. For high-intensity statin therapy, the goal is a > 50% reduction. If this milestone is not achieved, then additional lipid-lowering agents, such as ezetimibe, can be added.

Further ASCVD Testing

LCS with LDCT is associated with improved health outcomes, and LDCT is the preferred imaging modality. The ability of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC is sufficient for clinical decision making. Therefore, obtaining a traditional CAC score increases radiation exposure without additional clinical benefits.

Furthermore, although referral for additional testing in those with nonzero CAC scores is common, current evidence does not support this practice in asymptomatic individuals. Indeed, the risks of LCS include overdiagnosis, excessive testing, and overtreatment secondary to the discovery of other findings, such as benign pulmonary nodules and CAC. With respect to CAD, randomized controlled trials do not support a strategy of coronary angiography and intervention in asymptomatic individuals, even with moderate-to-severe ischemia on functional testing.40 As a result, routine stress tests to diagnose CAD or to confirm the results of CAC scores in asymptomatic individuals are not recommended. The only potential exception would be in select cases where the CAC score is > 1000 and when calcium is predominately located in the left main coronary artery.

Conclusions

LCS provides smokers at risk for lung cancer with the best probability to survive that diagnosis, and coincidentally LCS may also provide the best opportunity to prevent ASCVD events and mortality. Before initiating LCS, clinicians should initiate a shared decision making conversation about the benefits and risks of LDCT scans. In addition to relevant education about smoking, during shared decision making, the initial ASCVD risk estimate should be done using the PCE and when appropriate the benefits of statin therapy discussed. Individuals also should be informed of the potential for identifying CAC and counseled on its significance and how it might influence the decision to recommend statin therapy.

In patients undergoing LCS with an estimated risk of ≥ 7.5% to < 20%, moderate-intensity statin therapy is indicated. In this setting, a CAC score > 0 indicates subclinical atherosclerosis and should be used to help direct patients toward initiating statin therapy. Unfortunately, in patients undergoing LCS a CAC score of 0 might not provide protection against ASCVD, and until there is more information to the contrary, these individuals should at least participate in shared decision making about the long-term benefits of statin therapy in reducing ASCVD risk. Because LDCT scanning is done annually, there are opportunities to review the importance of prevention and to adjust therapy as needed to achieve the greatest reduction in ASCVD. Reported elevated CAC scores on LDCT provide an opportunity to re-engage the patient in the discussion about the benefits of statin therapy if they are not already on a statin, or consideration for high-intensity statin if the CAC score is > 1000 or reduction in baseline LDL-C is < 30% on the current statin dose.

1. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, Oudkerk M. Lung-cancer screening and the NELSON Trial. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2165-2166. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004224

2. Aberle T, Adams DR, Berg AM, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):396-409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

3. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;25(10):962-970. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1117

4. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341-350. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1211128

5. Khan SS, Ning H, Sinha A, et al. Cigarette smoking and competing risks for fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular disease subtypes across the life course. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(23):e021751. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.021751

6. Lu MT, Onuma OK, Massaro JM, et al. Lung cancer screening eligibility in the community: cardiovascular risk factors, coronary artery calcification, and cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2016;134(12):897-899. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023957

7. Tailor TD, Chiles C, Yeboah J, et al. Cardiovascular risk in the lung cancer screening population: a multicenter study evaluating the association between coronary artery calcification and preventive statin prescription. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(9):1258-1266. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2021.01.015

8. Mori H, Torii S, Kutyna M, et al. Coronary artery calcification and its progression: what does it really mean? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(1):127-142. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.012

10. Nasir K, Bittencourt MS, Blaha MJ, et al. Implications of coronary artery calcium testing among statin candidates according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol management guidelines: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(15): 1657-1668. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.066

11. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(13):1336-1345. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072100

12. Grandhi GR, Mirbolouk M, Dardari ZA. Interplay of coronary artery calcium and risk factors for predicting CVD/CHD Mortality: the CAC Consortium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(5):1175-1186. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.08.024

13. Blaha M, Budoff MJ, Shaw J. Absence of coronary artery calcification and all-cause mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(6):692-700. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.009

14. Shemesh J, Henschke CI, Farooqi A, et al. Frequency of coronary artery calcification on low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Clin Imaging. 2006;30(3):181-185. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2005.11.002

15. Shemesh J, Henschke C, Shaham D, et al. Ordinal scoring of coronary artery calcifications on low-dose CT scans of the chest is predictive of death from cardiovascular disease. Radiology. 2010;257:541-548. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100383

16. Jacobs PC, Gondrie MJ, van der Graaf Y, et al. Coronary artery calcium can predict all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events on low-dose CT screening for lung cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(3):505-511. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5577

17. Lessmann N, de Jong PA, Celeng C, et al. Sex differences in coronary artery and thoracic aorta calcification and their association with cardiovascular mortality in heavy smokers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(9):1808-1817. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.10.026

18. Gendarme S, Goussault H, Assie JB, et al. Impact on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates of coronary artery calcifications detected during organized, low-dose, computed-tomography screening for lung cancer: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(7):1553. doi:10.3390/cancers13071553

19. Hecht HS, Blaha MJ, Kazerooni EA, et al. CAC-DRS: coronary artery calcium data and reporting system. An expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2018;12(3):185-191. doi:10.1016/j.jcct.2018.03.008

20. Budoff MJ, Young R, Burke G, et al. Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(25):2401-2408. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy217

21. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1046-e1081. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000624

22. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

23. Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;328(8):746-753. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.13044

24. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2889-2934. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002

25. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline. Updated August 25, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/lipids

25. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline. Updated August 25, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/lipids

26. DeFilippis AP, Young, R, Carrubba CJ, et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):266-275. doi:10.7326/M14-1281

27. Rana JS, Tabada GH, Solomon, MD, et al. Accuracy of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk equation in a large contemporary, multiethnic population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(18):2118-2130. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.055

28. Sarwar A, Shaw LJ, Shapiro MD, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(6):675-688. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.031

29. McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Rivera JJ, et al. Mortality rates in smokers and nonsmokers in the presence or absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(10):1037-1045. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.02.017

30. Leigh A, McEvoy JW, Garg P, et al. Coronary artery calcium scores and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk stratification in smokers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(5):852-861. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.12.017

31. Garg PK, Jorgensen NW, McClelland RL, et al. Use of coronary artery calcium testing to improve coronary heart disease risk assessment in lung cancer screening population: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomagr. 2018;12(6):439-400.

32. Chiles C, Duan F, Gladish GW, et al. Association of coronary artery calcification and mortality in the national lung screening trial: a comparison of three scoring methods. Radiology. 2015;276(1):82-90. doi:10.1148/radiol.15142062

33. Takx RA, Isgum I, Willemink MJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium in nongated CT to predict cardiovascular events in male lung cancer screening participants: results of the NELSON study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9(1):50-57. doi:10.1016/j.jcct.2014.11.006

34. Mitchell JD, Paisley R, Moon P, et al. Coronary artery calcium and long-term risk of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke: The Walter Reed Cohort Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(12):1799-1806. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.09.003

35. Peng AW, Mirbolouk M, Orimoloye OA, et al. Long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality in asymptomatic patients with CAC >/=1,000: results from the CAC Consortium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;13(1, pt 1):83-93. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.005

36. Peng AW, Dardari ZA. Blumenthal RS, et al. Very high coronary artery calcium (>/=1000) and association with cardiovascular disease events, non-cardiovascular disease outcomes, and mortality: results from MESA. Circulation. 2021;143(16):1571-1583. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050545

37. Orringer CE, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, et al. The National Lipid Association scientific statement on coronary artery calcium scoring to guide preventive strategies for ASCVD risk reduction. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15(1):33-60. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2020.12.005

38. Sheperd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. PROSPER study group. PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease. (PROSPER): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623-1630. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11600-x

39. Puri R, Nicholls SJ, Shao M, et al. Impact of statins on serial coronary calcification during atheroma progression and regression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(13):1273-1282. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.036

40. Maron D.J, Hochman J S, Reynolds HR, et al. ISCHEMIA Research Group. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1395-1407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915922

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer mortality, and cigarette smoking is the most significant risk factor. Several randomized clinical trials have shown that lung cancer screening (LCS) with nonelectrocardiogram (ECG)-gated low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces both lung cancer and all-cause mortality.1,2 Hence, the US Preventive Screening Task Force (USPSTF) recommends annual screening with LDCT in adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.3

Smoking is also an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), and LCS clinical trials acknowledge that mortality from ASCVD events exceeds that of lung cancer.4,5 In an analysis of asymptomatic individuals from the Framingham Heart Offspring study who were eligible for LCS, the ASCVD event rate during a median (IQR) follow-up of 11.4 (9.7-12.0) years was 12.6%.6 However, despite the high rate of ASCVD events in this population, primary prevention strategies are consistently underused. In a study of 5495 individuals who underwent LCS with LDCT, only 40% of those eligible for statins had one prescribed, underscoring the missed opportunity for preventing ASCVD events during LCS.7 Yet the interactions for shared decision making and the availability of coronary artery calcification (CAC) scores from the LDCT provide an ideal window for intervening and preventing ASCVD events during LCS.

CAC is a hallmark of atherosclerotic plaque development and is proportional to plaque burden and ASCVD risk.8 Because of the relationship between CAC, subclinical atherosclerosis, and ASCVD risk, there is an opportunity to use CAC detected by LDCT to predict ASCVD risk and guide recommendations for statin treatment in individuals enrolled in LCS. Traditionally, CAC has been visualized by ECG-gated noncontrast CT scans with imaging protocols specifically designed to visualize the coronary arteries, minimize motion artifacts, and reduce signal noise. These scans are specifically done for primary prevention risk assessment and report an Agatston score, a summed measure based on calcified plaque area and maximal density.9 Results are reported as an overall CAC score and an age-, sex-, and race-adjusted percentile of CAC. Currently, a CAC score ≥ 100 or above the 75th percentile for age, sex, and race is considered abnormal.

High-quality evidence supports CAC scores as a strong predictor of ASCVD risk independent of age, sex, race, and other traditional risk factors.10-12 In asymptomatic individuals, a CAC score of 0 is a strong, negative risk factor associated with very low annualized mortality rates and cardiovascular (CV) events, so intermediate-risk individuals can be reclassified to a lower risk group avoiding or delaying statin therapy.13 As a result, current primary prevention guidelines allow for CAC scoring in asymptomatic, intermediate-risk adults where the clinical benefits of statin therapy are uncertain, knowing the CAC score will aid in the clinical decision to delay or initiate statin therapy.

Unlike traditional ECG-gated CAC scoring, LDCT imaging protocols are non–ECG-gated and performed at variable energy and slice thickness to optimize the detection of lung nodules. Early studies suggested that CAC detected by LDCT could be used in lieu of traditional CAC scoring to personalize risk.14,15 Recently, multiple studies have validated the accuracy and reproducibility of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC. In both the NELSON and the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) LCS trials, higher visual and quantitative measures of CAC were independently and incrementally associated with ASCVD risk.16,17 A subsequent review and meta-analysis of 6 LCS trials confirmed CAC detected by LDCT to be an independent predictor of ASCVD events regardless of the method used to measure CAC.18

There is now consensus that either an Agatston score or a visual estimate of CAC be reported on all noncontrast, noncardiac chest CT scans irrespective of the indication or technique, including LDCT scans for LCS using a uniform reporting system known as the Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS).19 The CAC-DRS simplifies reporting and adds modifiers indicating if the reported score is visual (V) or Agatston (A) and number of vessels involved. For example, CAC-DRS A0 or CAC-DRS V0 would indicate an Agatston score of 0 or a visual score of 0. CAC-DRS A1/N2 would indicate a total Agatston score of 1-99 in 2 coronary arteries. The currently agreed-on CAC-DRS risk groups are listed in the Table, along with their corresponding visual score or Agatston score and anticipated 10-year event rate, irrespective of other risk factors.20

As LCS efforts increase, primary care practitioners will receive LDCT reports that now incorporate an estimation of CAC (visual or quantitative). Thus, it will be increasingly important to know how to interpret and use these scores to guide clinical decisions regarding the initiation of statin therapy, referral for additional testing, and when to seek specialty cardiology care. For instance, does the absence of CAC (CAC = 0) on LDCT predict a low enough risk for statin therapy to be delayed or withdrawn? Does increasing CAC scores on follow-up LDCT in individuals on statin therapy represent treatment failure? When should CAC scores trigger additional testing, such as a stress test or referral to cardiology specialty care?

Primary Prevention in LCS

The initial approach to primary prevention in LCS is no different from that recommended by the 2018 multisociety guidelines on the management of blood cholesterol, the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline on primary prevention, or the 2022 USPTSF recommendations on statin use for primary prevention of CV disease in adults.21-23 For a baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥ 190 mg/dL, high-intensity statin therapy is recommended without further risk stratification. Individuals with diabetes also are at higher-than-average risk, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended.

For individuals not in either group, a validated ASCVD risk assessment tool is recommended to estimate baseline risk. The most validated tool for estimating risk in the US population is the 2013 ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE) which provides an estimate of the 10-year risk for fatal and myocardial infarction and fatal and nonfatal stroke.24 The PCE risk calculator uses age, presence of diabetes, sex, smoking history, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and treatment for hypertension to place individuals into 1 of 4 risk groups: low (< 5%), borderline (5% to < 7.5%), intermediate (≥ 7.5% to < 20%), and high (≥ 20%). Clinicians should be aware that the PCE only considers current smoking history and not prior smoking history or cumulative pack-year history. This differs from eligibility for LCS where recent smoking plays a larger role. All these risk factors are important to consider when evaluating risk and discussing risk-reducing strategies like statin therapy.

The 2018 multisociety guidelines and the 2019 primary prevention guidelines set the threshold for considering initiation of statin therapy at intermediate risk ≥ 7.5%.21,22 The 2020 US Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines set the threshold for considering statin therapy at an estimated 10-year event rate of 12%, whereas the 2022 UPSTF recommendations set the threshold at 10% with additional risk factors as the threshold for statin therapy.23,25 The reasons for these differences are beyond the scope of this review, but all these guidelines use the PCE to estimate baseline risk as the starting point for clinical decision making.

The PCE was originally derived and validated in population studies dating to the 1960s when the importance of diet, exercise, and smoking cessation in reducing ASCVD events was not well appreciated. The application of the PCE in more contemporary populations shows that it overestimates risk, especially in older individuals and women.26,27 Overestimation of risk has the potential to result in the initiation of statin therapy in individuals in whom the actual clinical benefit would otherwise be small.

To address this issue, current guidelines allow the use of CAC scoring to refine risk in individuals who are classified as intermediate risk and who otherwise desire to avoid lifelong statin therapy. Using current recommendations, we make suggestions on how to use CAC scores from LDCT to aid in clinical decision making for individuals in LCS (Figure).

No Coronary Artery Calcification

Between 25% and 30% of LDCT done for LCS will show no CAC.14,16 In general population studies, a CAC score of 0 is a strong negative predictor when there are no other risk factors.13,28 In contrast, the negative predictive ability of a CAC score of 0 in individuals with a smoking history who are eligible for LCS is unproven. In multivariate modeling, a CAC score of 0 did not reduce the significant hazard of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or smokers.29 In an analysis of 44,042 individuals without known heart disease referred for CAC scoring, the frequency of a CAC score of 0 was only modestly lower in smokers (38%) compared with nonsmokers (42%), yet the all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher.30 In addition, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) participants who were current smokers or eligible for LCS and had a CAC score of 0 had an observed 11-year ASCVD event rate of 13.4% and 20.8%, respectively, leading to the conclusion that a CAC score of 0 may not be predictive of minimal risk in smokers and those eligible for LCS.31 Additionally, in LCS-eligible individuals, the PCE underestimated event rates and incorporation of CAC scores did not significantly improve risk estimation. Finally, data from the NLST screening trial showed that the absence of CAC on LDCT was not associated with better survival or lower CV mortality compared with individuals with low CAC scores.32

The question of whether individuals undergoing LCS with LDCT who have no detectable CAC can avoid statin therapy is an unresolved issue; no contemporary studies have looked specifically at the relationship between estimated risk, a CAC score of 0, and ASCVD outcomes in individuals participating in LCS. For these reasons, we recommend moderate-intensity statin therapy when the estimated risk is intermediate because it is unclear that either an Agatston score of 0 reclassifies intermediate-risk LCS-eligible individuals to a lower risk group.

For the few borderline risk (estimated risk, 5% to < 7.5%) LCS-eligible individuals, a CAC score of 0 might confer low short-term risk but the long-term benefit of statin therapy on reducing subsequent risk, the presence of other risk factors, and the willingness to stop smoking should all be considered. For these individuals who elect to avoid statin therapy, annual re-estimation of risk at the time of repeat LDCT is recommended. In these circumstances, referral for traditional Agatston scoring is not likely to change decision making because the sensitivity of the 2 techniques is very similar.

Agatston Score of 1-99 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 1

In general population studies, these scores correspond to borderline risk and an estimated 10-year event rate of just under 7.5%.20 In both the NELSON and NLST LCS trials, even low amounts of CAC regardless of the scoring method were associated with higher observed ASCVD mortality when adjusted for other baseline risk factors.32 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with intermediate and borderline risk, a CAC score between 1 and 99 or a visual estimate of 1 indicates the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is reasonable.

Agatston Score of 100-299 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 2

Across all ages, races, and sexes, CAC scores between 100 to 299 are associated with an event rate of about 15% over 10 years.20 In the NELSON LCS trial, the adjusted hazard ratio for ASCVD events with a nontraditional Agatston score of 101 to 400 was 6.58.33 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with a CAC score of 100 to 299, regardless of the baseline risk estimate, the projected absolute event rate at 10 years would be about 20%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended to reduce the baseline LDL-C by 30% to 49%.

Agatston Score of > 300 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 3

Agatston CAC scores > 300 are consistent with a 10-year incidence of ASCVD events of > 15% regardless of age, sex, or race and ethnicity.20 In the Calcium Consortium, a CAC > 400 was correlated with an event rate of 13.6 events/1000 person-years.12 In a Walter Reed Military Medical Center study, a CAC score > 400 projected a cumulative incidence of ASCVD events of nearly 20% at 10 years.34 In smokers eligible for LCS, a CAC score > 300 projected a 10-year ASCVD event rate of 25%.29 In these patients, moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended, although high-intensity statin therapy can be considered if there are other risk factors.

Agatston Score ≥ 1000

The 2018 consensus statement on CAC reporting categorizes all CAC scores > 300 into a single risk group because the recommended treatment options do not differ.19 However, recent data suggest this might not be the case since individuals with very high CAC scores experience high rates of events that might justify more aggressive intervention. In an analysis of individuals who participated in the CAC Consortium with a CAC score ≥ 1000, the all-cause mortality rate was 18.8 per 1000 person-years with a CV mortality rate of 8 per 1000 person-years.35 Individuals with very high levels of CAC > 1000 also have a greater number of diseased coronary arteries, higher involvement of the left main coronary artery, and significantly higher event rates compared with those with a CAC of 400 to 999.36 In an analysis of individuals from the NLST trial, nontraditionally measured Agatston score > 1000 was associated with a hazard ratio for coronary artery disease (CAD) mortality of 3.66 in men and 5.81 in women.17 These observed and projected levels of risk are like that seen in secondary prevention trials, and some experts have recommended the use of high-intensity statin therapy to reduce LDL-C to < 70 mg/dL.37

Primary Prevention in Individuals aged 76 to 80 years

LCS can continue through age 80 years, while the PCE and primary prevention guidelines are truncated at age 75 years. Because age is a major contributor to risk, many of these individuals will already be in the intermediate- to high-risk group. However, the net clinical benefit of statin therapy for primary prevention in this age group is not well established, and the few primary prevention trials in this group have not demonstrated net clinical benefit.38 As a result, current guidelines do not provide specific treatment recommendations for individuals aged > 75 years but recognize the value of shared decision making considering associated comorbidities, age-related risks of statin therapy, and the desires of the individual to avoid ASCVD-related events even if the net clinical benefit is low.

Older individuals with elevated CAC scores should be informed about the risk of ASCVD events and the potential but unproven benefit of moderate-intensity statin therapy. Older individuals with a CAC score of 0 likely have low short-term risk of ASCVD events and withholding statin therapy is not unreasonable.

CAC Scores on Annual LDCT Scans

Because LCS requires annual LDCT scans, primary care practitioners and patients need to understand the significance of changing CAC scores over time. For individuals not on statin therapy, increasing calcification is a marker of progression of subclinical atherosclerosis. Patients undergoing LCS not on statin who have progressive increases in their CAC should consider initiating statin therapy. Individuals who opted not to initiate statin therapy who subsequently develop CAC should be re-engaged in a discussion about the significance of the finding and the clinically proven benefits of statin therapy in individuals with subclinical atherosclerosis. These considerations do not apply to individuals already on statin therapy. Statins convert lipid-rich plaques to lipid-depleted plaques, resulting in increasing calcification. As a result, CAC scores do not decrease and may increase with statin therapy.39 Individuals participating in annual LCS should be informed of this possibility. Also, in these individuals, referral to specialty care as a treatment failure is not supported by the literature.

Furthermore, serial CAC scoring to titrate the intensity of statin therapy is not currently recommended. The goal with moderate-intensity statin therapy is a 30% to 49% reduction from baseline LDL-C. If this milestone is not achieved, the statin dose can be escalated. For high-intensity statin therapy, the goal is a > 50% reduction. If this milestone is not achieved, then additional lipid-lowering agents, such as ezetimibe, can be added.

Further ASCVD Testing

LCS with LDCT is associated with improved health outcomes, and LDCT is the preferred imaging modality. The ability of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC is sufficient for clinical decision making. Therefore, obtaining a traditional CAC score increases radiation exposure without additional clinical benefits.

Furthermore, although referral for additional testing in those with nonzero CAC scores is common, current evidence does not support this practice in asymptomatic individuals. Indeed, the risks of LCS include overdiagnosis, excessive testing, and overtreatment secondary to the discovery of other findings, such as benign pulmonary nodules and CAC. With respect to CAD, randomized controlled trials do not support a strategy of coronary angiography and intervention in asymptomatic individuals, even with moderate-to-severe ischemia on functional testing.40 As a result, routine stress tests to diagnose CAD or to confirm the results of CAC scores in asymptomatic individuals are not recommended. The only potential exception would be in select cases where the CAC score is > 1000 and when calcium is predominately located in the left main coronary artery.

Conclusions

LCS provides smokers at risk for lung cancer with the best probability to survive that diagnosis, and coincidentally LCS may also provide the best opportunity to prevent ASCVD events and mortality. Before initiating LCS, clinicians should initiate a shared decision making conversation about the benefits and risks of LDCT scans. In addition to relevant education about smoking, during shared decision making, the initial ASCVD risk estimate should be done using the PCE and when appropriate the benefits of statin therapy discussed. Individuals also should be informed of the potential for identifying CAC and counseled on its significance and how it might influence the decision to recommend statin therapy.

In patients undergoing LCS with an estimated risk of ≥ 7.5% to < 20%, moderate-intensity statin therapy is indicated. In this setting, a CAC score > 0 indicates subclinical atherosclerosis and should be used to help direct patients toward initiating statin therapy. Unfortunately, in patients undergoing LCS a CAC score of 0 might not provide protection against ASCVD, and until there is more information to the contrary, these individuals should at least participate in shared decision making about the long-term benefits of statin therapy in reducing ASCVD risk. Because LDCT scanning is done annually, there are opportunities to review the importance of prevention and to adjust therapy as needed to achieve the greatest reduction in ASCVD. Reported elevated CAC scores on LDCT provide an opportunity to re-engage the patient in the discussion about the benefits of statin therapy if they are not already on a statin, or consideration for high-intensity statin if the CAC score is > 1000 or reduction in baseline LDL-C is < 30% on the current statin dose.

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer mortality, and cigarette smoking is the most significant risk factor. Several randomized clinical trials have shown that lung cancer screening (LCS) with nonelectrocardiogram (ECG)-gated low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces both lung cancer and all-cause mortality.1,2 Hence, the US Preventive Screening Task Force (USPSTF) recommends annual screening with LDCT in adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.3

Smoking is also an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), and LCS clinical trials acknowledge that mortality from ASCVD events exceeds that of lung cancer.4,5 In an analysis of asymptomatic individuals from the Framingham Heart Offspring study who were eligible for LCS, the ASCVD event rate during a median (IQR) follow-up of 11.4 (9.7-12.0) years was 12.6%.6 However, despite the high rate of ASCVD events in this population, primary prevention strategies are consistently underused. In a study of 5495 individuals who underwent LCS with LDCT, only 40% of those eligible for statins had one prescribed, underscoring the missed opportunity for preventing ASCVD events during LCS.7 Yet the interactions for shared decision making and the availability of coronary artery calcification (CAC) scores from the LDCT provide an ideal window for intervening and preventing ASCVD events during LCS.

CAC is a hallmark of atherosclerotic plaque development and is proportional to plaque burden and ASCVD risk.8 Because of the relationship between CAC, subclinical atherosclerosis, and ASCVD risk, there is an opportunity to use CAC detected by LDCT to predict ASCVD risk and guide recommendations for statin treatment in individuals enrolled in LCS. Traditionally, CAC has been visualized by ECG-gated noncontrast CT scans with imaging protocols specifically designed to visualize the coronary arteries, minimize motion artifacts, and reduce signal noise. These scans are specifically done for primary prevention risk assessment and report an Agatston score, a summed measure based on calcified plaque area and maximal density.9 Results are reported as an overall CAC score and an age-, sex-, and race-adjusted percentile of CAC. Currently, a CAC score ≥ 100 or above the 75th percentile for age, sex, and race is considered abnormal.

High-quality evidence supports CAC scores as a strong predictor of ASCVD risk independent of age, sex, race, and other traditional risk factors.10-12 In asymptomatic individuals, a CAC score of 0 is a strong, negative risk factor associated with very low annualized mortality rates and cardiovascular (CV) events, so intermediate-risk individuals can be reclassified to a lower risk group avoiding or delaying statin therapy.13 As a result, current primary prevention guidelines allow for CAC scoring in asymptomatic, intermediate-risk adults where the clinical benefits of statin therapy are uncertain, knowing the CAC score will aid in the clinical decision to delay or initiate statin therapy.

Unlike traditional ECG-gated CAC scoring, LDCT imaging protocols are non–ECG-gated and performed at variable energy and slice thickness to optimize the detection of lung nodules. Early studies suggested that CAC detected by LDCT could be used in lieu of traditional CAC scoring to personalize risk.14,15 Recently, multiple studies have validated the accuracy and reproducibility of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC. In both the NELSON and the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) LCS trials, higher visual and quantitative measures of CAC were independently and incrementally associated with ASCVD risk.16,17 A subsequent review and meta-analysis of 6 LCS trials confirmed CAC detected by LDCT to be an independent predictor of ASCVD events regardless of the method used to measure CAC.18

There is now consensus that either an Agatston score or a visual estimate of CAC be reported on all noncontrast, noncardiac chest CT scans irrespective of the indication or technique, including LDCT scans for LCS using a uniform reporting system known as the Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS).19 The CAC-DRS simplifies reporting and adds modifiers indicating if the reported score is visual (V) or Agatston (A) and number of vessels involved. For example, CAC-DRS A0 or CAC-DRS V0 would indicate an Agatston score of 0 or a visual score of 0. CAC-DRS A1/N2 would indicate a total Agatston score of 1-99 in 2 coronary arteries. The currently agreed-on CAC-DRS risk groups are listed in the Table, along with their corresponding visual score or Agatston score and anticipated 10-year event rate, irrespective of other risk factors.20

As LCS efforts increase, primary care practitioners will receive LDCT reports that now incorporate an estimation of CAC (visual or quantitative). Thus, it will be increasingly important to know how to interpret and use these scores to guide clinical decisions regarding the initiation of statin therapy, referral for additional testing, and when to seek specialty cardiology care. For instance, does the absence of CAC (CAC = 0) on LDCT predict a low enough risk for statin therapy to be delayed or withdrawn? Does increasing CAC scores on follow-up LDCT in individuals on statin therapy represent treatment failure? When should CAC scores trigger additional testing, such as a stress test or referral to cardiology specialty care?

Primary Prevention in LCS

The initial approach to primary prevention in LCS is no different from that recommended by the 2018 multisociety guidelines on the management of blood cholesterol, the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline on primary prevention, or the 2022 USPTSF recommendations on statin use for primary prevention of CV disease in adults.21-23 For a baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥ 190 mg/dL, high-intensity statin therapy is recommended without further risk stratification. Individuals with diabetes also are at higher-than-average risk, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended.

For individuals not in either group, a validated ASCVD risk assessment tool is recommended to estimate baseline risk. The most validated tool for estimating risk in the US population is the 2013 ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE) which provides an estimate of the 10-year risk for fatal and myocardial infarction and fatal and nonfatal stroke.24 The PCE risk calculator uses age, presence of diabetes, sex, smoking history, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and treatment for hypertension to place individuals into 1 of 4 risk groups: low (< 5%), borderline (5% to < 7.5%), intermediate (≥ 7.5% to < 20%), and high (≥ 20%). Clinicians should be aware that the PCE only considers current smoking history and not prior smoking history or cumulative pack-year history. This differs from eligibility for LCS where recent smoking plays a larger role. All these risk factors are important to consider when evaluating risk and discussing risk-reducing strategies like statin therapy.

The 2018 multisociety guidelines and the 2019 primary prevention guidelines set the threshold for considering initiation of statin therapy at intermediate risk ≥ 7.5%.21,22 The 2020 US Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines set the threshold for considering statin therapy at an estimated 10-year event rate of 12%, whereas the 2022 UPSTF recommendations set the threshold at 10% with additional risk factors as the threshold for statin therapy.23,25 The reasons for these differences are beyond the scope of this review, but all these guidelines use the PCE to estimate baseline risk as the starting point for clinical decision making.

The PCE was originally derived and validated in population studies dating to the 1960s when the importance of diet, exercise, and smoking cessation in reducing ASCVD events was not well appreciated. The application of the PCE in more contemporary populations shows that it overestimates risk, especially in older individuals and women.26,27 Overestimation of risk has the potential to result in the initiation of statin therapy in individuals in whom the actual clinical benefit would otherwise be small.

To address this issue, current guidelines allow the use of CAC scoring to refine risk in individuals who are classified as intermediate risk and who otherwise desire to avoid lifelong statin therapy. Using current recommendations, we make suggestions on how to use CAC scores from LDCT to aid in clinical decision making for individuals in LCS (Figure).

No Coronary Artery Calcification