User login

The Next Frontier of Antibiotic Discovery: Inside Your Gut

Scientists at Stanford University and the University of Pennsylvania have discovered a new antibiotic candidate in a surprising place: the human gut.

In mice, the antibiotic — a peptide known as prevotellin-2 — showed antimicrobial potency on par with polymyxin B, an antibiotic medication used to treat multidrug-resistant infections. Meanwhile, the peptide mainly left commensal, or beneficial, bacteria alone. The study, published in Cell, also identified several other potent antibiotic peptides with the potential to combat antimicrobial-resistant infections.

The research is part of a larger quest to find new antibiotics that can fight drug-resistant infections, a critical public health threat with more than 2.8 million cases and 35,000 deaths annually in the United States. That quest is urgent, said study author César de la Fuente, PhD, professor of bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“The main pillars that have enabled us to almost double our lifespan in the last 100 years or so have been antibiotics, vaccines, and clean water,” said Dr. de la Fuente. “Imagine taking out one of those. I think it would be pretty dramatic.” (Dr. De la Fuente’s lab has become known for finding antibiotic candidates in unusual places, like ancient genetic information of Neanderthals and woolly mammoths.)

The first widely used antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered in 1928, when a physician studying Staphylococcus bacteria returned to his lab after summer break to find mold growing in one of his petri dishes. But many other antibiotics — like streptomycin, tetracycline, and erythromycin — were discovered from soil bacteria, which produce variations of these substances to compete with other microorganisms.

By looking in the gut microbiome, the researchers hoped to identify peptides that the trillions of microbes use against each other in the fight for limited resources — ideally, peptides that wouldn’t broadly kill off the entire microbiome.

Kill the Bad, Spare the Good

Many traditional antibiotics are small molecules. This means they can wipe out the good bacteria in your body, and because each targets a specific bacterial function, bad bacteria can become resistant to them.

Peptide antibiotics, on the other hand, don’t diffuse into the whole body. If taken orally, they stay in the gut; if taken intravenously, they generally stay in the blood. And because of how they kill bacteria, targeting the membrane, they’re also less prone to bacterial resistance.

The microbiome is like a big reservoir of pathogens, said Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD, hematologist at Stanford University in California and one of the study’s authors. Because many antibiotics kill healthy gut bacteria, “what you have left over,” Dr. Bhatt said, “is this big open niche that gets filled up with multidrug-resistant organisms like E coli [Escherichia coli] or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.”

Dr. Bhatt has seen cancer patients undergo successful treatment only to die of a multidrug-resistant infection, because current antibiotics fail against those pathogens. “That’s like winning the battle to lose the war.”

By investigating the microbiome, “we wanted to see if we could identify antimicrobial peptides that might spare key members of our regular microbiome, so that we wouldn’t totally disrupt the microbiome the way we do when we use broad-spectrum, small molecule–based antibiotics,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The researchers used artificial intelligence to sift through 400,000 proteins to predict, based on known antibiotics, which peptide sequences might have antimicrobial properties. From the results, they chose 78 peptides to synthesize and test.

“The application of computational approaches combined with experimental validation is very powerful and exciting,” said Jennifer Geddes-McAlister, PhD, professor of cell biology at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, who was not involved in the study. “The study is robust in its approach to microbiome sampling.”

The Long Journey from Lab to Clinic

More than half of the peptides the team tested effectively inhibited the growth of harmful bacteria, and prevotellin-2 (derived from the bacteria Prevotella copri)stood out as the most powerful.

“The study validates experimental data from the lab using animal models, which moves discoveries closer to the clinic,” said Dr. Geddes-McAlister. “Further testing with clinical trials is needed, but the potential for clinical application is promising.”

Unfortunately, that’s not likely to happen anytime soon, said Dr. de la Fuente. “There is not enough economic incentive” for companies to develop new antibiotics. Ten years is his most hopeful guess for when we might see prevotellin-2, or a similar antibiotic, complete clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists at Stanford University and the University of Pennsylvania have discovered a new antibiotic candidate in a surprising place: the human gut.

In mice, the antibiotic — a peptide known as prevotellin-2 — showed antimicrobial potency on par with polymyxin B, an antibiotic medication used to treat multidrug-resistant infections. Meanwhile, the peptide mainly left commensal, or beneficial, bacteria alone. The study, published in Cell, also identified several other potent antibiotic peptides with the potential to combat antimicrobial-resistant infections.

The research is part of a larger quest to find new antibiotics that can fight drug-resistant infections, a critical public health threat with more than 2.8 million cases and 35,000 deaths annually in the United States. That quest is urgent, said study author César de la Fuente, PhD, professor of bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“The main pillars that have enabled us to almost double our lifespan in the last 100 years or so have been antibiotics, vaccines, and clean water,” said Dr. de la Fuente. “Imagine taking out one of those. I think it would be pretty dramatic.” (Dr. De la Fuente’s lab has become known for finding antibiotic candidates in unusual places, like ancient genetic information of Neanderthals and woolly mammoths.)

The first widely used antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered in 1928, when a physician studying Staphylococcus bacteria returned to his lab after summer break to find mold growing in one of his petri dishes. But many other antibiotics — like streptomycin, tetracycline, and erythromycin — were discovered from soil bacteria, which produce variations of these substances to compete with other microorganisms.

By looking in the gut microbiome, the researchers hoped to identify peptides that the trillions of microbes use against each other in the fight for limited resources — ideally, peptides that wouldn’t broadly kill off the entire microbiome.

Kill the Bad, Spare the Good

Many traditional antibiotics are small molecules. This means they can wipe out the good bacteria in your body, and because each targets a specific bacterial function, bad bacteria can become resistant to them.

Peptide antibiotics, on the other hand, don’t diffuse into the whole body. If taken orally, they stay in the gut; if taken intravenously, they generally stay in the blood. And because of how they kill bacteria, targeting the membrane, they’re also less prone to bacterial resistance.

The microbiome is like a big reservoir of pathogens, said Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD, hematologist at Stanford University in California and one of the study’s authors. Because many antibiotics kill healthy gut bacteria, “what you have left over,” Dr. Bhatt said, “is this big open niche that gets filled up with multidrug-resistant organisms like E coli [Escherichia coli] or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.”

Dr. Bhatt has seen cancer patients undergo successful treatment only to die of a multidrug-resistant infection, because current antibiotics fail against those pathogens. “That’s like winning the battle to lose the war.”

By investigating the microbiome, “we wanted to see if we could identify antimicrobial peptides that might spare key members of our regular microbiome, so that we wouldn’t totally disrupt the microbiome the way we do when we use broad-spectrum, small molecule–based antibiotics,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The researchers used artificial intelligence to sift through 400,000 proteins to predict, based on known antibiotics, which peptide sequences might have antimicrobial properties. From the results, they chose 78 peptides to synthesize and test.

“The application of computational approaches combined with experimental validation is very powerful and exciting,” said Jennifer Geddes-McAlister, PhD, professor of cell biology at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, who was not involved in the study. “The study is robust in its approach to microbiome sampling.”

The Long Journey from Lab to Clinic

More than half of the peptides the team tested effectively inhibited the growth of harmful bacteria, and prevotellin-2 (derived from the bacteria Prevotella copri)stood out as the most powerful.

“The study validates experimental data from the lab using animal models, which moves discoveries closer to the clinic,” said Dr. Geddes-McAlister. “Further testing with clinical trials is needed, but the potential for clinical application is promising.”

Unfortunately, that’s not likely to happen anytime soon, said Dr. de la Fuente. “There is not enough economic incentive” for companies to develop new antibiotics. Ten years is his most hopeful guess for when we might see prevotellin-2, or a similar antibiotic, complete clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists at Stanford University and the University of Pennsylvania have discovered a new antibiotic candidate in a surprising place: the human gut.

In mice, the antibiotic — a peptide known as prevotellin-2 — showed antimicrobial potency on par with polymyxin B, an antibiotic medication used to treat multidrug-resistant infections. Meanwhile, the peptide mainly left commensal, or beneficial, bacteria alone. The study, published in Cell, also identified several other potent antibiotic peptides with the potential to combat antimicrobial-resistant infections.

The research is part of a larger quest to find new antibiotics that can fight drug-resistant infections, a critical public health threat with more than 2.8 million cases and 35,000 deaths annually in the United States. That quest is urgent, said study author César de la Fuente, PhD, professor of bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“The main pillars that have enabled us to almost double our lifespan in the last 100 years or so have been antibiotics, vaccines, and clean water,” said Dr. de la Fuente. “Imagine taking out one of those. I think it would be pretty dramatic.” (Dr. De la Fuente’s lab has become known for finding antibiotic candidates in unusual places, like ancient genetic information of Neanderthals and woolly mammoths.)

The first widely used antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered in 1928, when a physician studying Staphylococcus bacteria returned to his lab after summer break to find mold growing in one of his petri dishes. But many other antibiotics — like streptomycin, tetracycline, and erythromycin — were discovered from soil bacteria, which produce variations of these substances to compete with other microorganisms.

By looking in the gut microbiome, the researchers hoped to identify peptides that the trillions of microbes use against each other in the fight for limited resources — ideally, peptides that wouldn’t broadly kill off the entire microbiome.

Kill the Bad, Spare the Good

Many traditional antibiotics are small molecules. This means they can wipe out the good bacteria in your body, and because each targets a specific bacterial function, bad bacteria can become resistant to them.

Peptide antibiotics, on the other hand, don’t diffuse into the whole body. If taken orally, they stay in the gut; if taken intravenously, they generally stay in the blood. And because of how they kill bacteria, targeting the membrane, they’re also less prone to bacterial resistance.

The microbiome is like a big reservoir of pathogens, said Ami Bhatt, MD, PhD, hematologist at Stanford University in California and one of the study’s authors. Because many antibiotics kill healthy gut bacteria, “what you have left over,” Dr. Bhatt said, “is this big open niche that gets filled up with multidrug-resistant organisms like E coli [Escherichia coli] or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.”

Dr. Bhatt has seen cancer patients undergo successful treatment only to die of a multidrug-resistant infection, because current antibiotics fail against those pathogens. “That’s like winning the battle to lose the war.”

By investigating the microbiome, “we wanted to see if we could identify antimicrobial peptides that might spare key members of our regular microbiome, so that we wouldn’t totally disrupt the microbiome the way we do when we use broad-spectrum, small molecule–based antibiotics,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The researchers used artificial intelligence to sift through 400,000 proteins to predict, based on known antibiotics, which peptide sequences might have antimicrobial properties. From the results, they chose 78 peptides to synthesize and test.

“The application of computational approaches combined with experimental validation is very powerful and exciting,” said Jennifer Geddes-McAlister, PhD, professor of cell biology at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, who was not involved in the study. “The study is robust in its approach to microbiome sampling.”

The Long Journey from Lab to Clinic

More than half of the peptides the team tested effectively inhibited the growth of harmful bacteria, and prevotellin-2 (derived from the bacteria Prevotella copri)stood out as the most powerful.

“The study validates experimental data from the lab using animal models, which moves discoveries closer to the clinic,” said Dr. Geddes-McAlister. “Further testing with clinical trials is needed, but the potential for clinical application is promising.”

Unfortunately, that’s not likely to happen anytime soon, said Dr. de la Fuente. “There is not enough economic incentive” for companies to develop new antibiotics. Ten years is his most hopeful guess for when we might see prevotellin-2, or a similar antibiotic, complete clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CELL

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

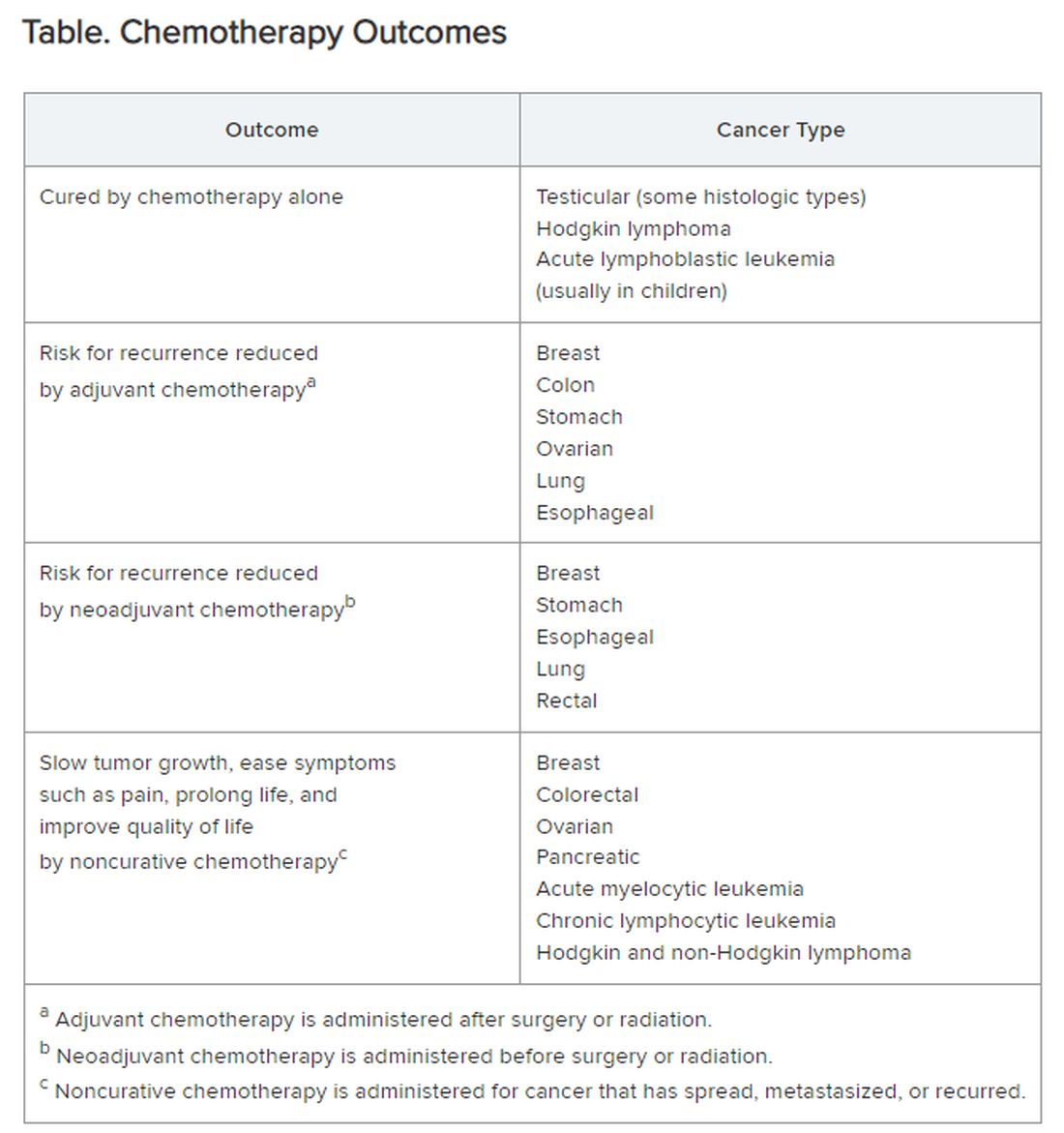

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians Lament Over Reliance on Relative Value Units: Survey

Most physicians oppose the way standardized relative value units (RVUs) are used to determine performance and compensation, according to Medscape’s 2024 Physicians and RVUs Report. About 6 in 10 survey respondents were unhappy with how RVUs affected them financially, while 7 in 10 said RVUs were poor measures of productivity.

The report analyzed 2024 survey data from 1005 practicing physicians who earn RVUs.

“I’m already mad that the medical field is controlled by health insurers and what they pay and authorize,” said an anesthesiologist in New York. “Then [that approach] is transferred to medical offices and hospitals, where physicians are paid by RVUs.”

Most physicians surveyed produced between 4000 and 8000 RVUs per year. Roughly one in six were high RVU generators, generating more than 10,000 annually.

In most cases, the metric influences earning potential — 42% of doctors surveyed said RVUs affect their salaries to some degree. One quarter said their salary was based entirely on RVUs. More than three fourths of physicians who received performance bonuses said they must meet RVU targets to do so.

“The current RVU system encourages unnecessary procedures, hurting patients,” said an orthopedic surgeon in Maine.

Nearly three fourths of practitioners surveyed said they occasionally to frequently felt pressure to take on more patients as a result of this system.

“I know numerous primary care doctors and specialists who have been forced to increase patient volume to meet RVU goals, and none is happy about it,” said Alok Patel, MD, a pediatric hospitalist with Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto, California. “Plus, patients are definitely not happy about being rushed.”

More than half of respondents said they occasionally or frequently felt compelled by their employer to use higher-level coding, which interferes with a physician’s ethical responsibility to the patient, said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a bioethicist at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City.

“Rather than rewarding excellence or good outcomes, you’re kind of rewarding procedures and volume,” said Dr. Caplan. “It’s more than pressure; it’s expected.”

Nearly 6 in 10 physicians said that the method for calculating reimbursements was unfair. Almost half said that they weren’t happy with how their workplace uses RVUs.

A few respondents said that their RVU model, which is often based on what Dr. Patel called an “overly complicated algorithm,” did not account for the time spent on tasks or the fact that some patients miss appointments. RVUs also rely on factors outside the control of a physician, such as location and patient volume, said one doctor.

The model can also lower the level of care patients receive, Dr. Patel said.

“I know primary care doctors who work in RVU-based systems and simply cannot take the necessary time — even if it’s 30-45 minutes — to thoroughly assess a patient, when the model forces them to take on 15-minute encounters.”

Finally, over half of clinicians said alternatives to the RVU system would be more effective, and 77% suggested including qualitative data. One respondent recommended incorporating time spent doing paperwork and communicating with patients, complexity of conditions, and medication management.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most physicians oppose the way standardized relative value units (RVUs) are used to determine performance and compensation, according to Medscape’s 2024 Physicians and RVUs Report. About 6 in 10 survey respondents were unhappy with how RVUs affected them financially, while 7 in 10 said RVUs were poor measures of productivity.

The report analyzed 2024 survey data from 1005 practicing physicians who earn RVUs.

“I’m already mad that the medical field is controlled by health insurers and what they pay and authorize,” said an anesthesiologist in New York. “Then [that approach] is transferred to medical offices and hospitals, where physicians are paid by RVUs.”

Most physicians surveyed produced between 4000 and 8000 RVUs per year. Roughly one in six were high RVU generators, generating more than 10,000 annually.

In most cases, the metric influences earning potential — 42% of doctors surveyed said RVUs affect their salaries to some degree. One quarter said their salary was based entirely on RVUs. More than three fourths of physicians who received performance bonuses said they must meet RVU targets to do so.

“The current RVU system encourages unnecessary procedures, hurting patients,” said an orthopedic surgeon in Maine.

Nearly three fourths of practitioners surveyed said they occasionally to frequently felt pressure to take on more patients as a result of this system.

“I know numerous primary care doctors and specialists who have been forced to increase patient volume to meet RVU goals, and none is happy about it,” said Alok Patel, MD, a pediatric hospitalist with Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto, California. “Plus, patients are definitely not happy about being rushed.”

More than half of respondents said they occasionally or frequently felt compelled by their employer to use higher-level coding, which interferes with a physician’s ethical responsibility to the patient, said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a bioethicist at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City.

“Rather than rewarding excellence or good outcomes, you’re kind of rewarding procedures and volume,” said Dr. Caplan. “It’s more than pressure; it’s expected.”

Nearly 6 in 10 physicians said that the method for calculating reimbursements was unfair. Almost half said that they weren’t happy with how their workplace uses RVUs.

A few respondents said that their RVU model, which is often based on what Dr. Patel called an “overly complicated algorithm,” did not account for the time spent on tasks or the fact that some patients miss appointments. RVUs also rely on factors outside the control of a physician, such as location and patient volume, said one doctor.

The model can also lower the level of care patients receive, Dr. Patel said.

“I know primary care doctors who work in RVU-based systems and simply cannot take the necessary time — even if it’s 30-45 minutes — to thoroughly assess a patient, when the model forces them to take on 15-minute encounters.”

Finally, over half of clinicians said alternatives to the RVU system would be more effective, and 77% suggested including qualitative data. One respondent recommended incorporating time spent doing paperwork and communicating with patients, complexity of conditions, and medication management.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most physicians oppose the way standardized relative value units (RVUs) are used to determine performance and compensation, according to Medscape’s 2024 Physicians and RVUs Report. About 6 in 10 survey respondents were unhappy with how RVUs affected them financially, while 7 in 10 said RVUs were poor measures of productivity.

The report analyzed 2024 survey data from 1005 practicing physicians who earn RVUs.

“I’m already mad that the medical field is controlled by health insurers and what they pay and authorize,” said an anesthesiologist in New York. “Then [that approach] is transferred to medical offices and hospitals, where physicians are paid by RVUs.”

Most physicians surveyed produced between 4000 and 8000 RVUs per year. Roughly one in six were high RVU generators, generating more than 10,000 annually.

In most cases, the metric influences earning potential — 42% of doctors surveyed said RVUs affect their salaries to some degree. One quarter said their salary was based entirely on RVUs. More than three fourths of physicians who received performance bonuses said they must meet RVU targets to do so.

“The current RVU system encourages unnecessary procedures, hurting patients,” said an orthopedic surgeon in Maine.

Nearly three fourths of practitioners surveyed said they occasionally to frequently felt pressure to take on more patients as a result of this system.

“I know numerous primary care doctors and specialists who have been forced to increase patient volume to meet RVU goals, and none is happy about it,” said Alok Patel, MD, a pediatric hospitalist with Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto, California. “Plus, patients are definitely not happy about being rushed.”

More than half of respondents said they occasionally or frequently felt compelled by their employer to use higher-level coding, which interferes with a physician’s ethical responsibility to the patient, said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a bioethicist at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City.

“Rather than rewarding excellence or good outcomes, you’re kind of rewarding procedures and volume,” said Dr. Caplan. “It’s more than pressure; it’s expected.”

Nearly 6 in 10 physicians said that the method for calculating reimbursements was unfair. Almost half said that they weren’t happy with how their workplace uses RVUs.

A few respondents said that their RVU model, which is often based on what Dr. Patel called an “overly complicated algorithm,” did not account for the time spent on tasks or the fact that some patients miss appointments. RVUs also rely on factors outside the control of a physician, such as location and patient volume, said one doctor.

The model can also lower the level of care patients receive, Dr. Patel said.

“I know primary care doctors who work in RVU-based systems and simply cannot take the necessary time — even if it’s 30-45 minutes — to thoroughly assess a patient, when the model forces them to take on 15-minute encounters.”

Finally, over half of clinicians said alternatives to the RVU system would be more effective, and 77% suggested including qualitative data. One respondent recommended incorporating time spent doing paperwork and communicating with patients, complexity of conditions, and medication management.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Will Compounding ‘Best Practices’ Guide Reassure Clinicians?

A new “best practices” guide released by the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding (APC) aims to educate compounding pharmacists and reassure prescribers about the ethical, legal, and practical considerations that must be addressed to ensure quality standards and protect patients’ health.

Endocrinologists have expressed skepticism about the quality of compounded drugs, particularly the popular glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) semaglutide. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued an alert linking hospitalizations to overdoses of compounded semaglutide.

“This document goes beyond today’s media-grabbing shortages,” APC Board Chair-Elect Gina Besteman, RPh, of Belmar Pharma Solutions told this news organization. “We developed these best practices to apply to all shortage drug compounding, and especially in this moment when so many are compounding GLP-1s. These serve as a reminder about what compliance and care look like.”

Prescribers determine whether a patient needs a compounded medication, not pharmacists, Ms. Besteman noted. “A patient-specific prescription order must be authorized for a compounded medication to be dispensed. Prescribers should ensure pharmacies they work with regularly check the FDA Drug Shortage List, as compounding of ‘essential copies’ of FDA-approved drugs is only allowed when a drug is listed as ‘currently in shortage.’ ”

Framework for Compounding

“With fake and illegal online stores popping up, it’s critical for legitimate, state-licensed compounding pharmacies to maintain the profession’s high standards,” the APC said in a media communication.

Highlights of its best practices, which are directed toward 503A state-licensed compounding pharmacies, include the following, among others:

- Pharmacies should check the FDA drug shortage list prior to preparing a copy of an FDA-approved drug and maintain documentation to demonstrate to regulators that the drug was in shortage at the time it was compounded.

- Pharmacies may only source active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from state-licensed wholesalers who purchase from FDA-registered manufacturers or order directly from FDA-registered manufacturers.

- Verify from the wholesaler that the manufacturer is registered with the FDA and the API meets all the requirements of section 503A, and that both hold the appropriate permits or licenses in their home state and the shipped to state.

- Adhere to USP Chapter <797> testing requirements for sterility, endotoxin, stability, particulate, antimicrobial effectiveness, and container closure integrity studies.

- Counseling must be offered to the patient or the patient’s agent/caregiver. Providing written information that assists in the understanding of how to properly use the compounded medication is advised.

- Instructions should be written in a way that a layperson can understand (especially directions including dosage titrations and conversions between milligrams and milliliters or units).

- Like all medications, compounded drugs can only be prescribed in the presence of a valid patient-practitioner relationship and can only be dispensed by a pharmacy after receipt of a valid patient-specific prescription order.

- When marketing, never make claims of safety or efficacy of the compounded product.

- Advertising that patients will/may save money using compounded medications, compared with manufactured products is not allowed.

“Compounding FDA-approved drugs during shortages is nothing new — pharmacies have been doing it well before GLP-1s came on the scene, and they’ll continue long after this current shortage ends,” Ms. Besteman said. “Prescribers should be aware of APC’s guidelines because they provide a framework for ethically and legally compounding medications during drug shortages.

“To paraphrase The Police,” she concluded, “every move you make, every step you take, they’ll be watching you. Make sure they see those best practices in action.”

‘Reduces the Risks’

Commenting on the best practices guidance, Ivania Rizo, MD, director of Obesity Medicine and Diabetes and clinical colead at Boston Medical Center’s Health Equity Accelerator in Massachusetts, said: “These best practices will hopefully make a difference in the quality of compounded drugs.”

“The emphasis on rigorous testing of APIs and adherence to USP standards is particularly important for maintaining drug quality,” she noted. “This structured approach reduces the risk of variability and ensures that compounded drugs meet high-quality standards, thus enhancing their reliability.”

“Knowing that compounding pharmacies are adhering to rigorous standards for sourcing, testing, and compounding can at least reassure clinicians that specific steps are being taken for the safety and efficacy of these medications,” she said. “The transparency in documenting compliance with FDA guidelines and maintaining high-quality control measures can enhance trust among healthcare providers.”

Although clinicians are likely to have more confidence in compounded drugs when these best practices are followed, she said, “overall, we all hope that the shortages of medications such as tirzepatide are resolved promptly, allowing patients to access FDA-approved drugs without the need for compounding.”

“While the implementation of best practices for compounding during shortages is a positive and necessary step, our ultimate goal remains to address and resolve these shortages in the near future,” she concluded.

Dr. Rizo declared no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new “best practices” guide released by the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding (APC) aims to educate compounding pharmacists and reassure prescribers about the ethical, legal, and practical considerations that must be addressed to ensure quality standards and protect patients’ health.

Endocrinologists have expressed skepticism about the quality of compounded drugs, particularly the popular glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) semaglutide. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued an alert linking hospitalizations to overdoses of compounded semaglutide.

“This document goes beyond today’s media-grabbing shortages,” APC Board Chair-Elect Gina Besteman, RPh, of Belmar Pharma Solutions told this news organization. “We developed these best practices to apply to all shortage drug compounding, and especially in this moment when so many are compounding GLP-1s. These serve as a reminder about what compliance and care look like.”

Prescribers determine whether a patient needs a compounded medication, not pharmacists, Ms. Besteman noted. “A patient-specific prescription order must be authorized for a compounded medication to be dispensed. Prescribers should ensure pharmacies they work with regularly check the FDA Drug Shortage List, as compounding of ‘essential copies’ of FDA-approved drugs is only allowed when a drug is listed as ‘currently in shortage.’ ”

Framework for Compounding

“With fake and illegal online stores popping up, it’s critical for legitimate, state-licensed compounding pharmacies to maintain the profession’s high standards,” the APC said in a media communication.

Highlights of its best practices, which are directed toward 503A state-licensed compounding pharmacies, include the following, among others:

- Pharmacies should check the FDA drug shortage list prior to preparing a copy of an FDA-approved drug and maintain documentation to demonstrate to regulators that the drug was in shortage at the time it was compounded.

- Pharmacies may only source active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from state-licensed wholesalers who purchase from FDA-registered manufacturers or order directly from FDA-registered manufacturers.

- Verify from the wholesaler that the manufacturer is registered with the FDA and the API meets all the requirements of section 503A, and that both hold the appropriate permits or licenses in their home state and the shipped to state.

- Adhere to USP Chapter <797> testing requirements for sterility, endotoxin, stability, particulate, antimicrobial effectiveness, and container closure integrity studies.

- Counseling must be offered to the patient or the patient’s agent/caregiver. Providing written information that assists in the understanding of how to properly use the compounded medication is advised.

- Instructions should be written in a way that a layperson can understand (especially directions including dosage titrations and conversions between milligrams and milliliters or units).

- Like all medications, compounded drugs can only be prescribed in the presence of a valid patient-practitioner relationship and can only be dispensed by a pharmacy after receipt of a valid patient-specific prescription order.

- When marketing, never make claims of safety or efficacy of the compounded product.

- Advertising that patients will/may save money using compounded medications, compared with manufactured products is not allowed.

“Compounding FDA-approved drugs during shortages is nothing new — pharmacies have been doing it well before GLP-1s came on the scene, and they’ll continue long after this current shortage ends,” Ms. Besteman said. “Prescribers should be aware of APC’s guidelines because they provide a framework for ethically and legally compounding medications during drug shortages.

“To paraphrase The Police,” she concluded, “every move you make, every step you take, they’ll be watching you. Make sure they see those best practices in action.”

‘Reduces the Risks’

Commenting on the best practices guidance, Ivania Rizo, MD, director of Obesity Medicine and Diabetes and clinical colead at Boston Medical Center’s Health Equity Accelerator in Massachusetts, said: “These best practices will hopefully make a difference in the quality of compounded drugs.”

“The emphasis on rigorous testing of APIs and adherence to USP standards is particularly important for maintaining drug quality,” she noted. “This structured approach reduces the risk of variability and ensures that compounded drugs meet high-quality standards, thus enhancing their reliability.”

“Knowing that compounding pharmacies are adhering to rigorous standards for sourcing, testing, and compounding can at least reassure clinicians that specific steps are being taken for the safety and efficacy of these medications,” she said. “The transparency in documenting compliance with FDA guidelines and maintaining high-quality control measures can enhance trust among healthcare providers.”

Although clinicians are likely to have more confidence in compounded drugs when these best practices are followed, she said, “overall, we all hope that the shortages of medications such as tirzepatide are resolved promptly, allowing patients to access FDA-approved drugs without the need for compounding.”

“While the implementation of best practices for compounding during shortages is a positive and necessary step, our ultimate goal remains to address and resolve these shortages in the near future,” she concluded.

Dr. Rizo declared no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new “best practices” guide released by the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding (APC) aims to educate compounding pharmacists and reassure prescribers about the ethical, legal, and practical considerations that must be addressed to ensure quality standards and protect patients’ health.

Endocrinologists have expressed skepticism about the quality of compounded drugs, particularly the popular glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) semaglutide. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued an alert linking hospitalizations to overdoses of compounded semaglutide.

“This document goes beyond today’s media-grabbing shortages,” APC Board Chair-Elect Gina Besteman, RPh, of Belmar Pharma Solutions told this news organization. “We developed these best practices to apply to all shortage drug compounding, and especially in this moment when so many are compounding GLP-1s. These serve as a reminder about what compliance and care look like.”

Prescribers determine whether a patient needs a compounded medication, not pharmacists, Ms. Besteman noted. “A patient-specific prescription order must be authorized for a compounded medication to be dispensed. Prescribers should ensure pharmacies they work with regularly check the FDA Drug Shortage List, as compounding of ‘essential copies’ of FDA-approved drugs is only allowed when a drug is listed as ‘currently in shortage.’ ”

Framework for Compounding

“With fake and illegal online stores popping up, it’s critical for legitimate, state-licensed compounding pharmacies to maintain the profession’s high standards,” the APC said in a media communication.

Highlights of its best practices, which are directed toward 503A state-licensed compounding pharmacies, include the following, among others:

- Pharmacies should check the FDA drug shortage list prior to preparing a copy of an FDA-approved drug and maintain documentation to demonstrate to regulators that the drug was in shortage at the time it was compounded.

- Pharmacies may only source active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from state-licensed wholesalers who purchase from FDA-registered manufacturers or order directly from FDA-registered manufacturers.

- Verify from the wholesaler that the manufacturer is registered with the FDA and the API meets all the requirements of section 503A, and that both hold the appropriate permits or licenses in their home state and the shipped to state.

- Adhere to USP Chapter <797> testing requirements for sterility, endotoxin, stability, particulate, antimicrobial effectiveness, and container closure integrity studies.

- Counseling must be offered to the patient or the patient’s agent/caregiver. Providing written information that assists in the understanding of how to properly use the compounded medication is advised.

- Instructions should be written in a way that a layperson can understand (especially directions including dosage titrations and conversions between milligrams and milliliters or units).

- Like all medications, compounded drugs can only be prescribed in the presence of a valid patient-practitioner relationship and can only be dispensed by a pharmacy after receipt of a valid patient-specific prescription order.

- When marketing, never make claims of safety or efficacy of the compounded product.

- Advertising that patients will/may save money using compounded medications, compared with manufactured products is not allowed.

“Compounding FDA-approved drugs during shortages is nothing new — pharmacies have been doing it well before GLP-1s came on the scene, and they’ll continue long after this current shortage ends,” Ms. Besteman said. “Prescribers should be aware of APC’s guidelines because they provide a framework for ethically and legally compounding medications during drug shortages.

“To paraphrase The Police,” she concluded, “every move you make, every step you take, they’ll be watching you. Make sure they see those best practices in action.”

‘Reduces the Risks’

Commenting on the best practices guidance, Ivania Rizo, MD, director of Obesity Medicine and Diabetes and clinical colead at Boston Medical Center’s Health Equity Accelerator in Massachusetts, said: “These best practices will hopefully make a difference in the quality of compounded drugs.”

“The emphasis on rigorous testing of APIs and adherence to USP standards is particularly important for maintaining drug quality,” she noted. “This structured approach reduces the risk of variability and ensures that compounded drugs meet high-quality standards, thus enhancing their reliability.”

“Knowing that compounding pharmacies are adhering to rigorous standards for sourcing, testing, and compounding can at least reassure clinicians that specific steps are being taken for the safety and efficacy of these medications,” she said. “The transparency in documenting compliance with FDA guidelines and maintaining high-quality control measures can enhance trust among healthcare providers.”

Although clinicians are likely to have more confidence in compounded drugs when these best practices are followed, she said, “overall, we all hope that the shortages of medications such as tirzepatide are resolved promptly, allowing patients to access FDA-approved drugs without the need for compounding.”

“While the implementation of best practices for compounding during shortages is a positive and necessary step, our ultimate goal remains to address and resolve these shortages in the near future,” she concluded.

Dr. Rizo declared no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Do New Blood Tests for Cancer Meet the Right Standards?

Biotech startups worldwide are rushing to market screening tests that they claim can detect various cancers in early stages with just a few drops of blood. The tests allegedly will simplify cancer care by eliminating tedious scans, scopes, and swabs at the doctor’s office.

The promise of these early detection tests is truly “enticing,” Hilary A. Robbins, PhD, from the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization in Lyon, France, said in an interview.

In an opinion article in The New England Journal of Medicine, she emphasized that the new cancer tests are much less cumbersome than traditional screening strategies for individual cancers. Moreover, they could enable the early detection of dozens of cancer types for which no screening has been available so far.

Meeting the Criteria

The problem is that these tests have not met the strict criteria typically required for traditional cancer screening tests. To be considered for introduction as a screening procedure, a test usually needs to meet the following four minimum requirements:

- The disease that the test screens for must have a presymptomatic form.

- The screening test must be able to identify this presymptomatic disease.

- Treating the disease in the presymptomatic phase improves prognosis (specifically, it affects cancer-specific mortality in a randomized controlled trial).

- The screening test is feasible, and the benefits outweigh potential risks.

“The new blood tests for multiple cancers have so far only met the second criteria, showing they can detect presymptomatic cancer,” Dr. Robbins wrote.

The next step would be to demonstrate that they affect cancer-specific mortality. “But currently, commercial interests seem to be influencing the evidence standards for these cancer tests,” said Dr. Robbins.

Inappropriate Endpoints?

Some proponents of such tests argue that, unlike for previous cancer screening procedures, initial approval should not depend on the endpoint of cancer-specific mortality. It would take too long to gather sufficient outcome data, and in the meantime, people would die, they argue.

Eric A. Klein, MD, from the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute in Cleveland, Ohio, and colleagues advocate for alternative endpoints such as the incidence of late-stage cancer in an article published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

“The concept would be,” they wrote, “that a negative signal would not indicate a mortality benefit, leading to the study being stopped. A positive signal, on the other hand, could result in provisional approval until mortality data and real-world evidence of effectiveness are available. This would resemble the accelerated approval of new cancer drugs, which often is based on progression-free survival until there postmarketing data on overall survival emerge.”

Dr. Klein is also employed at the US biotech start-up Grail, which developed the Galleri test, which is one of the best-known and most advanced cancer screening tests. The Galleri test uses cell-free DNA and machine learning to detect a common cancer signal in more than 50 cancer types and predict the origin of the cancer signal. Consumers in the United States can already order and perform the test.

An NHS Study

Arguments for different endpoints apparently resonated with the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS). Three years ago, they initiated the Galleri study, a large randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of Grail’s cancer test. The primary endpoint was not cancer-specific mortality, but the incidence of stage III or IV cancer.

The results are expected in 2026. But recruitment was stopped after 140,000 participants were enrolled. The NHS reported that the initial results were not convincing enough to continue the trial. Exact numbers were not disclosed.

The Galleri study deviates from the standard randomized controlled trial design for cancer screening procedures not only in terms of the primary endpoint, but also in blinding. The only participants who were unblinded and informed of their test results are those in the intervention group with a positive cancer test.

False Security

This trial design encourages participants to undergo blood tests once per year. But according to Dr. Robbins, it prevents the exploration of the phenomenon of “false security,” which is a potential drawback of the new cancer tests.

“Women with a negative mammogram can reasonably assume that they probably do not have breast cancer. But individuals with a negative cancer blood test could mistakenly believe they cannot have any cancer at all. As a result, they may not undergo standard early detection screenings or seek medical help early enough for potential cancer symptoms,” said Dr. Robbins.

To assess the actual risk-benefit ratio of the Galleri test, participants must receive their test results, she said. “Under real-world conditions, benefits and risks can come from positive and negative results.”

Upcoming Trial

More illuminating results may come from a large trial planned by the National Cancer Institute in the United States. Several new cancer tests will be evaluated for their ability to reduce cancer-specific mortality. A pilot phase will start later in 2024. “This study may be the only one with sufficient statistical power to determine whether an approach based on these cancer tests can reduce cancer-specific mortality,” said Dr. Robbins.

For the new blood tests for multiple cancers, it is crucial that health authorities “set a high bar for a benefit,” she said. This, according to her, also means that they must show an effect on cancer-specific mortality before being introduced. “This evidence must come from studies in which commercial interests do not influence the design, execution, data management, or data analysis.”

This story was translated from the Medscape German edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Biotech startups worldwide are rushing to market screening tests that they claim can detect various cancers in early stages with just a few drops of blood. The tests allegedly will simplify cancer care by eliminating tedious scans, scopes, and swabs at the doctor’s office.

The promise of these early detection tests is truly “enticing,” Hilary A. Robbins, PhD, from the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization in Lyon, France, said in an interview.

In an opinion article in The New England Journal of Medicine, she emphasized that the new cancer tests are much less cumbersome than traditional screening strategies for individual cancers. Moreover, they could enable the early detection of dozens of cancer types for which no screening has been available so far.

Meeting the Criteria

The problem is that these tests have not met the strict criteria typically required for traditional cancer screening tests. To be considered for introduction as a screening procedure, a test usually needs to meet the following four minimum requirements:

- The disease that the test screens for must have a presymptomatic form.

- The screening test must be able to identify this presymptomatic disease.

- Treating the disease in the presymptomatic phase improves prognosis (specifically, it affects cancer-specific mortality in a randomized controlled trial).

- The screening test is feasible, and the benefits outweigh potential risks.

“The new blood tests for multiple cancers have so far only met the second criteria, showing they can detect presymptomatic cancer,” Dr. Robbins wrote.

The next step would be to demonstrate that they affect cancer-specific mortality. “But currently, commercial interests seem to be influencing the evidence standards for these cancer tests,” said Dr. Robbins.

Inappropriate Endpoints?

Some proponents of such tests argue that, unlike for previous cancer screening procedures, initial approval should not depend on the endpoint of cancer-specific mortality. It would take too long to gather sufficient outcome data, and in the meantime, people would die, they argue.

Eric A. Klein, MD, from the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute in Cleveland, Ohio, and colleagues advocate for alternative endpoints such as the incidence of late-stage cancer in an article published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

“The concept would be,” they wrote, “that a negative signal would not indicate a mortality benefit, leading to the study being stopped. A positive signal, on the other hand, could result in provisional approval until mortality data and real-world evidence of effectiveness are available. This would resemble the accelerated approval of new cancer drugs, which often is based on progression-free survival until there postmarketing data on overall survival emerge.”

Dr. Klein is also employed at the US biotech start-up Grail, which developed the Galleri test, which is one of the best-known and most advanced cancer screening tests. The Galleri test uses cell-free DNA and machine learning to detect a common cancer signal in more than 50 cancer types and predict the origin of the cancer signal. Consumers in the United States can already order and perform the test.

An NHS Study

Arguments for different endpoints apparently resonated with the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS). Three years ago, they initiated the Galleri study, a large randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of Grail’s cancer test. The primary endpoint was not cancer-specific mortality, but the incidence of stage III or IV cancer.

The results are expected in 2026. But recruitment was stopped after 140,000 participants were enrolled. The NHS reported that the initial results were not convincing enough to continue the trial. Exact numbers were not disclosed.

The Galleri study deviates from the standard randomized controlled trial design for cancer screening procedures not only in terms of the primary endpoint, but also in blinding. The only participants who were unblinded and informed of their test results are those in the intervention group with a positive cancer test.

False Security

This trial design encourages participants to undergo blood tests once per year. But according to Dr. Robbins, it prevents the exploration of the phenomenon of “false security,” which is a potential drawback of the new cancer tests.