User login

Bipolar patients can be identified using ‘rule of three’

Dr. Hagop S. Akiskal’s “rule of three” conceptualization, which identified behavioral markers tied to bipolarity, proved effective in evaluating and differentiating patients with bipolar disorder from those with unipolar depression, according to Dr. Diogo R. Lara and his associates.

A univariate analysis of more than 70,000 samples found 29 behavioral markers significantly differentiated bipolar patients from patients with unipolar depression. Of these 29, 10 markers had odds ratios greater than 4 for bipolarity.

In a multivariate analysis, 11 markers differentiating bipolar from unipolar depression were confirmed, including reversed circadian rhythms and high debts for both genders; 3 or more provoked car accidents and talent for poetry in men; frequent book reading; 3 or more religion changes; 60 or more sexual partners; experiencing pathological love 2 or more times; heavy cursing; and extravagant dressing styles in women; found Dr. Lara of the Pontifíícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and his associates.

“Most behaviors were expressed in a minority of patients (usually 5%-30%) and usually the ‘rule of three’ was the best numerical marker to distinguish those with bipolarity,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study here: J Affect Disord. 2015 Sept 1;183:195-204. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.046).

Dr. Hagop S. Akiskal’s “rule of three” conceptualization, which identified behavioral markers tied to bipolarity, proved effective in evaluating and differentiating patients with bipolar disorder from those with unipolar depression, according to Dr. Diogo R. Lara and his associates.

A univariate analysis of more than 70,000 samples found 29 behavioral markers significantly differentiated bipolar patients from patients with unipolar depression. Of these 29, 10 markers had odds ratios greater than 4 for bipolarity.

In a multivariate analysis, 11 markers differentiating bipolar from unipolar depression were confirmed, including reversed circadian rhythms and high debts for both genders; 3 or more provoked car accidents and talent for poetry in men; frequent book reading; 3 or more religion changes; 60 or more sexual partners; experiencing pathological love 2 or more times; heavy cursing; and extravagant dressing styles in women; found Dr. Lara of the Pontifíícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and his associates.

“Most behaviors were expressed in a minority of patients (usually 5%-30%) and usually the ‘rule of three’ was the best numerical marker to distinguish those with bipolarity,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study here: J Affect Disord. 2015 Sept 1;183:195-204. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.046).

Dr. Hagop S. Akiskal’s “rule of three” conceptualization, which identified behavioral markers tied to bipolarity, proved effective in evaluating and differentiating patients with bipolar disorder from those with unipolar depression, according to Dr. Diogo R. Lara and his associates.

A univariate analysis of more than 70,000 samples found 29 behavioral markers significantly differentiated bipolar patients from patients with unipolar depression. Of these 29, 10 markers had odds ratios greater than 4 for bipolarity.

In a multivariate analysis, 11 markers differentiating bipolar from unipolar depression were confirmed, including reversed circadian rhythms and high debts for both genders; 3 or more provoked car accidents and talent for poetry in men; frequent book reading; 3 or more religion changes; 60 or more sexual partners; experiencing pathological love 2 or more times; heavy cursing; and extravagant dressing styles in women; found Dr. Lara of the Pontifíícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and his associates.

“Most behaviors were expressed in a minority of patients (usually 5%-30%) and usually the ‘rule of three’ was the best numerical marker to distinguish those with bipolarity,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study here: J Affect Disord. 2015 Sept 1;183:195-204. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.046).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Metabolic dysfunction markers found in bipolar patients

Bipolar disorder patients had different levels of some of the biomarkers linked to metabolic dysfunction than healthy controls, according to a study.

The study’s participants included 57 bipolar disorder patients and a control group of 49 healthy individuals. Among the experimental group, 24 had bipolar disorder type I and the remaining 33 had bipolar disorder type II. The bipolar patients’ average duration of illness was 22 years and their average body mass index was 25.9 kg/m2. The experimental group’s ages and body mass indices were not significantly different from those of the control group.

The researchers compared the bipolar disorder patients’ and control group’s average levels of the biomarkers: C-peptide, ghrelin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1), glucagon, insulin, leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1, total), resistin, and visfatin.

Bipolar disorder patients has significantly lower levels of ghrelin, glucagon, and GLP-1 (P = .018 for ghrelin; P less than .0001 for glucagon; P less than .0001 for GLP-1), and significantly higher levels of GIP than did controls (P less than .0001).

When the bipolar I patients’ biomarker levels were compared with those of the bipolar II patients, no significant differences were found.

Additional findings included negative correlations between a patient’s level of glucagon and numbers of previous manic (r = –0.480; P less than .001), depressive (r = –0.294; P = .026), and any mood episodes (r = –0.403; P = .002). GLP-1 levels also were negatively correlated with the numbers of manic (r = –0.322; P = .015) and any mood episodes (r = –0.274 ; P = .039) experienced by a patient.

“Our findings support the hypothesis that dysregulations in serum glucagon, GLP-1, GIP, and ghrelin might be involved in [bipolar disorder] pathogenesis, particularly in the depressed phase. Moreover, the correlation of glucagon and GLP-1 alterations with number of mood episode recurrences could contribute to the identification of late-stage” bipolar disorder patients, according to Gianluca Rosso, Ph.D., of the University of Torino, Italy, and his colleagues. “Studies in larger samples are needed to confirm these data and to further investigate the common mechanism between mood and metabolic disorders.”

Read the full article here: (J Affect Disord. 2015 Sept 15;184:293-8.)

Bipolar disorder patients had different levels of some of the biomarkers linked to metabolic dysfunction than healthy controls, according to a study.

The study’s participants included 57 bipolar disorder patients and a control group of 49 healthy individuals. Among the experimental group, 24 had bipolar disorder type I and the remaining 33 had bipolar disorder type II. The bipolar patients’ average duration of illness was 22 years and their average body mass index was 25.9 kg/m2. The experimental group’s ages and body mass indices were not significantly different from those of the control group.

The researchers compared the bipolar disorder patients’ and control group’s average levels of the biomarkers: C-peptide, ghrelin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1), glucagon, insulin, leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1, total), resistin, and visfatin.

Bipolar disorder patients has significantly lower levels of ghrelin, glucagon, and GLP-1 (P = .018 for ghrelin; P less than .0001 for glucagon; P less than .0001 for GLP-1), and significantly higher levels of GIP than did controls (P less than .0001).

When the bipolar I patients’ biomarker levels were compared with those of the bipolar II patients, no significant differences were found.

Additional findings included negative correlations between a patient’s level of glucagon and numbers of previous manic (r = –0.480; P less than .001), depressive (r = –0.294; P = .026), and any mood episodes (r = –0.403; P = .002). GLP-1 levels also were negatively correlated with the numbers of manic (r = –0.322; P = .015) and any mood episodes (r = –0.274 ; P = .039) experienced by a patient.

“Our findings support the hypothesis that dysregulations in serum glucagon, GLP-1, GIP, and ghrelin might be involved in [bipolar disorder] pathogenesis, particularly in the depressed phase. Moreover, the correlation of glucagon and GLP-1 alterations with number of mood episode recurrences could contribute to the identification of late-stage” bipolar disorder patients, according to Gianluca Rosso, Ph.D., of the University of Torino, Italy, and his colleagues. “Studies in larger samples are needed to confirm these data and to further investigate the common mechanism between mood and metabolic disorders.”

Read the full article here: (J Affect Disord. 2015 Sept 15;184:293-8.)

Bipolar disorder patients had different levels of some of the biomarkers linked to metabolic dysfunction than healthy controls, according to a study.

The study’s participants included 57 bipolar disorder patients and a control group of 49 healthy individuals. Among the experimental group, 24 had bipolar disorder type I and the remaining 33 had bipolar disorder type II. The bipolar patients’ average duration of illness was 22 years and their average body mass index was 25.9 kg/m2. The experimental group’s ages and body mass indices were not significantly different from those of the control group.

The researchers compared the bipolar disorder patients’ and control group’s average levels of the biomarkers: C-peptide, ghrelin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1), glucagon, insulin, leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1, total), resistin, and visfatin.

Bipolar disorder patients has significantly lower levels of ghrelin, glucagon, and GLP-1 (P = .018 for ghrelin; P less than .0001 for glucagon; P less than .0001 for GLP-1), and significantly higher levels of GIP than did controls (P less than .0001).

When the bipolar I patients’ biomarker levels were compared with those of the bipolar II patients, no significant differences were found.

Additional findings included negative correlations between a patient’s level of glucagon and numbers of previous manic (r = –0.480; P less than .001), depressive (r = –0.294; P = .026), and any mood episodes (r = –0.403; P = .002). GLP-1 levels also were negatively correlated with the numbers of manic (r = –0.322; P = .015) and any mood episodes (r = –0.274 ; P = .039) experienced by a patient.

“Our findings support the hypothesis that dysregulations in serum glucagon, GLP-1, GIP, and ghrelin might be involved in [bipolar disorder] pathogenesis, particularly in the depressed phase. Moreover, the correlation of glucagon and GLP-1 alterations with number of mood episode recurrences could contribute to the identification of late-stage” bipolar disorder patients, according to Gianluca Rosso, Ph.D., of the University of Torino, Italy, and his colleagues. “Studies in larger samples are needed to confirm these data and to further investigate the common mechanism between mood and metabolic disorders.”

Read the full article here: (J Affect Disord. 2015 Sept 15;184:293-8.)

FROM JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Nonplanning impulsivity linked to low medication adherence in bipolar patients

In euthymic bipolar patients, higher nonplanning impulsivity, defined as a lack of future orientation, was associated with lower medication adherence, according to a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Lead author Dr. Raoul Belzeaux of Sainte Marguerite Hospital in Marseilles, France, and his associates examined 260 euthymic bipolar patients who were given a questionnaire. Adherence to medication was evaluated by Medication Adherence Rating Scale, and nonplanning impulsivity was measured by Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.

Even after controlling for potential confounding factors, adherence to medication was correlated with nonplanning impulsivity (beta-standardized coefficient = 0.156; P = .015), the authors noted. In addition, path analysis demonstrated only a direct effect of nonplanning impulsivity on adherence to medication.

Read the full article here: (J Affect Disord. 2015 Sep 15;184:60-6 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.041]).

In euthymic bipolar patients, higher nonplanning impulsivity, defined as a lack of future orientation, was associated with lower medication adherence, according to a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Lead author Dr. Raoul Belzeaux of Sainte Marguerite Hospital in Marseilles, France, and his associates examined 260 euthymic bipolar patients who were given a questionnaire. Adherence to medication was evaluated by Medication Adherence Rating Scale, and nonplanning impulsivity was measured by Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.

Even after controlling for potential confounding factors, adherence to medication was correlated with nonplanning impulsivity (beta-standardized coefficient = 0.156; P = .015), the authors noted. In addition, path analysis demonstrated only a direct effect of nonplanning impulsivity on adherence to medication.

Read the full article here: (J Affect Disord. 2015 Sep 15;184:60-6 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.041]).

In euthymic bipolar patients, higher nonplanning impulsivity, defined as a lack of future orientation, was associated with lower medication adherence, according to a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Lead author Dr. Raoul Belzeaux of Sainte Marguerite Hospital in Marseilles, France, and his associates examined 260 euthymic bipolar patients who were given a questionnaire. Adherence to medication was evaluated by Medication Adherence Rating Scale, and nonplanning impulsivity was measured by Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.

Even after controlling for potential confounding factors, adherence to medication was correlated with nonplanning impulsivity (beta-standardized coefficient = 0.156; P = .015), the authors noted. In addition, path analysis demonstrated only a direct effect of nonplanning impulsivity on adherence to medication.

Read the full article here: (J Affect Disord. 2015 Sep 15;184:60-6 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.041]).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Bipolar patients have lower functional exercise capacity than peers

Patients with bipolar disorder have a lower functional exercise capacity than do healthy controls, according to a pilot study published in Psychiatry Research. Researchers found that backward stepwise regression analyses showed that foot pain, low back pain, and depressive symptoms account for 70% of the variance in functional exercise capacity of patients with bipolar disorder

Davy Vancampfort, Ph.D, of the University of Leuven, Belgium, and his associates compared 30 patients with bipolar disorder with 30 healthy controls. All participants performed the 6-minute walk test to assess the functional exercise capacity and were screened for psychiatric symptoms using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and Hypomania Checklist-32. They found patients with bipolar disorder demonstrated a significantly poorer functional exercise capacity (590.8 plus or minus 112.6 m vs. 704.2 plus or minus 94.3 m) than did their peers, with foot and back pain were the most common negative predictors of functional exercise capacity in patients with bipolar disorder.

The authors noted that a multidisciplinary care model that includes improving the functional exercise capacity should be a key target for treatment. “Physical activity interventions delivered by physical therapists may help ameliorate pain symptoms and improve functional exercise capacity,” the authors wrote.

Read the full article here: (Psychiatry Res. 2015 Sept 30;229(1-2):194-9 [doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.040]).

Patients with bipolar disorder have a lower functional exercise capacity than do healthy controls, according to a pilot study published in Psychiatry Research. Researchers found that backward stepwise regression analyses showed that foot pain, low back pain, and depressive symptoms account for 70% of the variance in functional exercise capacity of patients with bipolar disorder

Davy Vancampfort, Ph.D, of the University of Leuven, Belgium, and his associates compared 30 patients with bipolar disorder with 30 healthy controls. All participants performed the 6-minute walk test to assess the functional exercise capacity and were screened for psychiatric symptoms using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and Hypomania Checklist-32. They found patients with bipolar disorder demonstrated a significantly poorer functional exercise capacity (590.8 plus or minus 112.6 m vs. 704.2 plus or minus 94.3 m) than did their peers, with foot and back pain were the most common negative predictors of functional exercise capacity in patients with bipolar disorder.

The authors noted that a multidisciplinary care model that includes improving the functional exercise capacity should be a key target for treatment. “Physical activity interventions delivered by physical therapists may help ameliorate pain symptoms and improve functional exercise capacity,” the authors wrote.

Read the full article here: (Psychiatry Res. 2015 Sept 30;229(1-2):194-9 [doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.040]).

Patients with bipolar disorder have a lower functional exercise capacity than do healthy controls, according to a pilot study published in Psychiatry Research. Researchers found that backward stepwise regression analyses showed that foot pain, low back pain, and depressive symptoms account for 70% of the variance in functional exercise capacity of patients with bipolar disorder

Davy Vancampfort, Ph.D, of the University of Leuven, Belgium, and his associates compared 30 patients with bipolar disorder with 30 healthy controls. All participants performed the 6-minute walk test to assess the functional exercise capacity and were screened for psychiatric symptoms using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and Hypomania Checklist-32. They found patients with bipolar disorder demonstrated a significantly poorer functional exercise capacity (590.8 plus or minus 112.6 m vs. 704.2 plus or minus 94.3 m) than did their peers, with foot and back pain were the most common negative predictors of functional exercise capacity in patients with bipolar disorder.

The authors noted that a multidisciplinary care model that includes improving the functional exercise capacity should be a key target for treatment. “Physical activity interventions delivered by physical therapists may help ameliorate pain symptoms and improve functional exercise capacity,” the authors wrote.

Read the full article here: (Psychiatry Res. 2015 Sept 30;229(1-2):194-9 [doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.040]).

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

Family history, life stressors predict age of bipolar onset

A family history of psychiatric disorders and negative life stressors are associated with earlier and later onset of bipolar disorder, respectively, according to Dr. C.S. Thesing of the department of old age psychiatry, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam.

In a study of 78 patients aged 60 years or older, a family history of psychiatric disorders was significantly associated with early age of illness onset (P less than .01), while negative stressors were associated with a later age of onset (P less than .05). Childhood abuse was not associated with either age of onset or the presence or absence of a family history of psychiatric disorders, reported Dr. Thesing and coauthors.

“Further research should be aimed at exploring both the biological and environmental aspects of [bipolar disorder] together,” the researchers wrote. “Later age at onset was associated with negative stressors prior to the first episode, possibly requiring a clinical emphasis on preventing stressors and/or strengthening patients in their abilities to deal with stressors to prevent new affective episodes,” they concluded.

Read the full study in Journal of Affective Disorders.

A family history of psychiatric disorders and negative life stressors are associated with earlier and later onset of bipolar disorder, respectively, according to Dr. C.S. Thesing of the department of old age psychiatry, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam.

In a study of 78 patients aged 60 years or older, a family history of psychiatric disorders was significantly associated with early age of illness onset (P less than .01), while negative stressors were associated with a later age of onset (P less than .05). Childhood abuse was not associated with either age of onset or the presence or absence of a family history of psychiatric disorders, reported Dr. Thesing and coauthors.

“Further research should be aimed at exploring both the biological and environmental aspects of [bipolar disorder] together,” the researchers wrote. “Later age at onset was associated with negative stressors prior to the first episode, possibly requiring a clinical emphasis on preventing stressors and/or strengthening patients in their abilities to deal with stressors to prevent new affective episodes,” they concluded.

Read the full study in Journal of Affective Disorders.

A family history of psychiatric disorders and negative life stressors are associated with earlier and later onset of bipolar disorder, respectively, according to Dr. C.S. Thesing of the department of old age psychiatry, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam.

In a study of 78 patients aged 60 years or older, a family history of psychiatric disorders was significantly associated with early age of illness onset (P less than .01), while negative stressors were associated with a later age of onset (P less than .05). Childhood abuse was not associated with either age of onset or the presence or absence of a family history of psychiatric disorders, reported Dr. Thesing and coauthors.

“Further research should be aimed at exploring both the biological and environmental aspects of [bipolar disorder] together,” the researchers wrote. “Later age at onset was associated with negative stressors prior to the first episode, possibly requiring a clinical emphasis on preventing stressors and/or strengthening patients in their abilities to deal with stressors to prevent new affective episodes,” they concluded.

Read the full study in Journal of Affective Disorders.

Bipolar disorder diagnoses higher than referrals

Fewer patients were referred to psychiatrists for suspected bipolar disorder than the number of patients diagnosed with the illness, Canadian researchers reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Dr. Andrée Daigneault and her colleagues found that, over a 10-year period, the number of patients referred for suspicion of bipolar disorder (n = 583) was lower than the number of bipolar disorder diagnoses (n = 640).

To conduct the study, the investigators looked at records from Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal’s Module Evaluation/Liaison (MEL) division. The hospital’s psychiatrists examined 18,111 patients from 1998 to 2010 and carried out 10,492 (58%) assessments, reported Dr. Daigneault of the hospital and the Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Montreal, and her associates.

Of all patients assessed by the MEL, 583 patients were referred for a suspicion of bipolar disorder, while 640 patients received the diagnosis from a MEL psychiatrist (40.3% type I, 40.5% type II). The proportion of patients referred to the MEL for suspicion of bipolar disorder remained stable over the 10 years of the study and held between 2.2% and 4.6% annually. Both bipolar I and II disorders were more commonly diagnosed in secondary care than in primary, the authors noted. They also found no increase in the proportion of bipolar disorder referrals over the 10 years of the study.

“If the psychiatric and medical communities seem to become increasing familiar with [bipolar disorder], our study fails to demonstrate that [bipolar disorder] is overly suspected or identified in primary care,” the authors wrote. They said their data suggest that general practitioners “have not been influenced by the popularity of [bipolar disorder], as could have been suggested if rates of [bipolar] suspicions increased over time or surpassed that of [bipolar] diagnoses.”

Read the full article here: (J. Affect. Disord. 2015;174:225-32 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.057]).

Fewer patients were referred to psychiatrists for suspected bipolar disorder than the number of patients diagnosed with the illness, Canadian researchers reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Dr. Andrée Daigneault and her colleagues found that, over a 10-year period, the number of patients referred for suspicion of bipolar disorder (n = 583) was lower than the number of bipolar disorder diagnoses (n = 640).

To conduct the study, the investigators looked at records from Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal’s Module Evaluation/Liaison (MEL) division. The hospital’s psychiatrists examined 18,111 patients from 1998 to 2010 and carried out 10,492 (58%) assessments, reported Dr. Daigneault of the hospital and the Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Montreal, and her associates.

Of all patients assessed by the MEL, 583 patients were referred for a suspicion of bipolar disorder, while 640 patients received the diagnosis from a MEL psychiatrist (40.3% type I, 40.5% type II). The proportion of patients referred to the MEL for suspicion of bipolar disorder remained stable over the 10 years of the study and held between 2.2% and 4.6% annually. Both bipolar I and II disorders were more commonly diagnosed in secondary care than in primary, the authors noted. They also found no increase in the proportion of bipolar disorder referrals over the 10 years of the study.

“If the psychiatric and medical communities seem to become increasing familiar with [bipolar disorder], our study fails to demonstrate that [bipolar disorder] is overly suspected or identified in primary care,” the authors wrote. They said their data suggest that general practitioners “have not been influenced by the popularity of [bipolar disorder], as could have been suggested if rates of [bipolar] suspicions increased over time or surpassed that of [bipolar] diagnoses.”

Read the full article here: (J. Affect. Disord. 2015;174:225-32 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.057]).

Fewer patients were referred to psychiatrists for suspected bipolar disorder than the number of patients diagnosed with the illness, Canadian researchers reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Dr. Andrée Daigneault and her colleagues found that, over a 10-year period, the number of patients referred for suspicion of bipolar disorder (n = 583) was lower than the number of bipolar disorder diagnoses (n = 640).

To conduct the study, the investigators looked at records from Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal’s Module Evaluation/Liaison (MEL) division. The hospital’s psychiatrists examined 18,111 patients from 1998 to 2010 and carried out 10,492 (58%) assessments, reported Dr. Daigneault of the hospital and the Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Montreal, and her associates.

Of all patients assessed by the MEL, 583 patients were referred for a suspicion of bipolar disorder, while 640 patients received the diagnosis from a MEL psychiatrist (40.3% type I, 40.5% type II). The proportion of patients referred to the MEL for suspicion of bipolar disorder remained stable over the 10 years of the study and held between 2.2% and 4.6% annually. Both bipolar I and II disorders were more commonly diagnosed in secondary care than in primary, the authors noted. They also found no increase in the proportion of bipolar disorder referrals over the 10 years of the study.

“If the psychiatric and medical communities seem to become increasing familiar with [bipolar disorder], our study fails to demonstrate that [bipolar disorder] is overly suspected or identified in primary care,” the authors wrote. They said their data suggest that general practitioners “have not been influenced by the popularity of [bipolar disorder], as could have been suggested if rates of [bipolar] suspicions increased over time or surpassed that of [bipolar] diagnoses.”

Read the full article here: (J. Affect. Disord. 2015;174:225-32 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.057]).

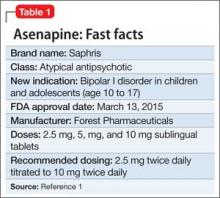

Asenapine for pediatric bipolar disorder: New indication

Asenapine an atypical antipsychotic sold under the brand name Saphris, was granted a second, pediatric indication by the FDA in March 2015 as monotherapy for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents age 10 to 17 (Table 1).1 (Asenapine was first approved in August 2009 as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate in adults for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.1,2)

Dosage and administration

Asenapine is available as 2.5-, 5-, and 10-mg sublingual tablets, the only atypical antipsychotic with this formulation.1 The recommended dosage for the new indication is 2.5 mg twice daily for 3 days, titrated to 5 mg twice daily, titrated again to 10 mg twice daily after 3 days.3 In a phase I study, pediatric patients appeared to be more sensitive to dystonia when the recommended dosage escalation schedule was not followed.3

In clinical trials, drinking water 2 to 5 minutes after taking asenapine decreased exposure to the drug. Instruct patients not to swallow the tablet and to avoid eating and drinking for 10 minutes after administration.3

For full prescribing information for pediatric and adult patients, see Reference 3.

Safety and efficacy

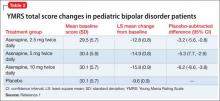

In a 3-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of 403 patients, 302 children and adolescents age 10 to 17 received asenapine at fixed dosages of 2.5 to 10 mg twice daily; the remainder were given placebo. The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score and Clinical Global Impressions Severity of Illness scores of patients who received asenapine improved significantly compared with those who received placebo, as measured by change from baseline to week 3 (Table 2).1

The safety and efficacy of asenapine has not been evaluated in pediatric bipolar disorder patients age ≤10 or pediatric schizophrenia patients age ≤12, or as an adjunctive therapy in pediatric bipolar disorder patients.

Asenapine was not shown to be effective in pediatric patients with schizophrenia in an 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial.

The pharmacokinetics of asenapine in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adults.

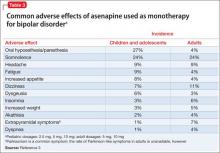

Adverse effects

In pediatric patients, the most common reported adverse effects of asenapine are:

• dizziness

• dysgeusia

• fatigue

• increased appetite

• increased weight

• nausea

• oral paresthesia

• somnolence.

Similar adverse effects were reported in the pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder clinical trials (Table 3).3 A complete list of reported adverse effects is given in the package insert.3

When treating pediatric patients, monitor the child’s weight gain against expected normal weight gain.

Asenapine is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment and those who have a hypersensitivity to asenapine or any components in its formulation.3

1. Actavis receives FDA approval of Saphris for pediatric patients with bipolar I disorder. Drugs.com. http://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/actavis-receivesfda-

approval-saphris-pediatric-patients-bipolardisorder-4188.html. Published March 2015. Accessed June 19, 2015.

2. Lincoln J, Preskon S. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2009;12(8):75-76,83-85.

3. Saphris [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

Asenapine an atypical antipsychotic sold under the brand name Saphris, was granted a second, pediatric indication by the FDA in March 2015 as monotherapy for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents age 10 to 17 (Table 1).1 (Asenapine was first approved in August 2009 as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate in adults for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.1,2)

Dosage and administration

Asenapine is available as 2.5-, 5-, and 10-mg sublingual tablets, the only atypical antipsychotic with this formulation.1 The recommended dosage for the new indication is 2.5 mg twice daily for 3 days, titrated to 5 mg twice daily, titrated again to 10 mg twice daily after 3 days.3 In a phase I study, pediatric patients appeared to be more sensitive to dystonia when the recommended dosage escalation schedule was not followed.3

In clinical trials, drinking water 2 to 5 minutes after taking asenapine decreased exposure to the drug. Instruct patients not to swallow the tablet and to avoid eating and drinking for 10 minutes after administration.3

For full prescribing information for pediatric and adult patients, see Reference 3.

Safety and efficacy

In a 3-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of 403 patients, 302 children and adolescents age 10 to 17 received asenapine at fixed dosages of 2.5 to 10 mg twice daily; the remainder were given placebo. The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score and Clinical Global Impressions Severity of Illness scores of patients who received asenapine improved significantly compared with those who received placebo, as measured by change from baseline to week 3 (Table 2).1

The safety and efficacy of asenapine has not been evaluated in pediatric bipolar disorder patients age ≤10 or pediatric schizophrenia patients age ≤12, or as an adjunctive therapy in pediatric bipolar disorder patients.

Asenapine was not shown to be effective in pediatric patients with schizophrenia in an 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial.

The pharmacokinetics of asenapine in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adults.

Adverse effects

In pediatric patients, the most common reported adverse effects of asenapine are:

• dizziness

• dysgeusia

• fatigue

• increased appetite

• increased weight

• nausea

• oral paresthesia

• somnolence.

Similar adverse effects were reported in the pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder clinical trials (Table 3).3 A complete list of reported adverse effects is given in the package insert.3

When treating pediatric patients, monitor the child’s weight gain against expected normal weight gain.

Asenapine is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment and those who have a hypersensitivity to asenapine or any components in its formulation.3

Asenapine an atypical antipsychotic sold under the brand name Saphris, was granted a second, pediatric indication by the FDA in March 2015 as monotherapy for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents age 10 to 17 (Table 1).1 (Asenapine was first approved in August 2009 as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate in adults for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.1,2)

Dosage and administration

Asenapine is available as 2.5-, 5-, and 10-mg sublingual tablets, the only atypical antipsychotic with this formulation.1 The recommended dosage for the new indication is 2.5 mg twice daily for 3 days, titrated to 5 mg twice daily, titrated again to 10 mg twice daily after 3 days.3 In a phase I study, pediatric patients appeared to be more sensitive to dystonia when the recommended dosage escalation schedule was not followed.3

In clinical trials, drinking water 2 to 5 minutes after taking asenapine decreased exposure to the drug. Instruct patients not to swallow the tablet and to avoid eating and drinking for 10 minutes after administration.3

For full prescribing information for pediatric and adult patients, see Reference 3.

Safety and efficacy

In a 3-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of 403 patients, 302 children and adolescents age 10 to 17 received asenapine at fixed dosages of 2.5 to 10 mg twice daily; the remainder were given placebo. The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score and Clinical Global Impressions Severity of Illness scores of patients who received asenapine improved significantly compared with those who received placebo, as measured by change from baseline to week 3 (Table 2).1

The safety and efficacy of asenapine has not been evaluated in pediatric bipolar disorder patients age ≤10 or pediatric schizophrenia patients age ≤12, or as an adjunctive therapy in pediatric bipolar disorder patients.

Asenapine was not shown to be effective in pediatric patients with schizophrenia in an 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial.

The pharmacokinetics of asenapine in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adults.

Adverse effects

In pediatric patients, the most common reported adverse effects of asenapine are:

• dizziness

• dysgeusia

• fatigue

• increased appetite

• increased weight

• nausea

• oral paresthesia

• somnolence.

Similar adverse effects were reported in the pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder clinical trials (Table 3).3 A complete list of reported adverse effects is given in the package insert.3

When treating pediatric patients, monitor the child’s weight gain against expected normal weight gain.

Asenapine is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment and those who have a hypersensitivity to asenapine or any components in its formulation.3

1. Actavis receives FDA approval of Saphris for pediatric patients with bipolar I disorder. Drugs.com. http://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/actavis-receivesfda-

approval-saphris-pediatric-patients-bipolardisorder-4188.html. Published March 2015. Accessed June 19, 2015.

2. Lincoln J, Preskon S. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2009;12(8):75-76,83-85.

3. Saphris [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

1. Actavis receives FDA approval of Saphris for pediatric patients with bipolar I disorder. Drugs.com. http://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/actavis-receivesfda-

approval-saphris-pediatric-patients-bipolardisorder-4188.html. Published March 2015. Accessed June 19, 2015.

2. Lincoln J, Preskon S. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2009;12(8):75-76,83-85.

3. Saphris [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

Knowledge lacking on auditory hallucinations in bipolar, depressed patients

Research into auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) is lacking in several important ways, according to a systematic review by Dr. Wei Lin Toh and associates.

While previous research indicates that a significant number of people with BD and MDD experience AVH, estimates vary widely, from 11.3% to 62.8% of BD patients, and 5.4% to 40.6% of MDD patients. One neuroimaging study found potential frontotemporal connectivity relating to AVH in bipolar patients.

No study has systematically investigated phenomenological characteristics of AVH in BD and MDD, a significant gap in knowledge relating to AVH in the two disorders. In addition, the investigators recommend research into links between AVH and delusions, as many BD patients and MDD patients experience both delusions and hallucinations of any sort.

“The topic of AVH remains a central but largely understudied symptom in BD, and more so, MDD. Further progress can only be achieved when phenomenological, cognitive, and neuroimaging research efforts go hand-in-hand,” concluded Dr. Toh of Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Find the full review in the Journal of Affective Disorders (May 28, 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.040]).

Research into auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) is lacking in several important ways, according to a systematic review by Dr. Wei Lin Toh and associates.

While previous research indicates that a significant number of people with BD and MDD experience AVH, estimates vary widely, from 11.3% to 62.8% of BD patients, and 5.4% to 40.6% of MDD patients. One neuroimaging study found potential frontotemporal connectivity relating to AVH in bipolar patients.

No study has systematically investigated phenomenological characteristics of AVH in BD and MDD, a significant gap in knowledge relating to AVH in the two disorders. In addition, the investigators recommend research into links between AVH and delusions, as many BD patients and MDD patients experience both delusions and hallucinations of any sort.

“The topic of AVH remains a central but largely understudied symptom in BD, and more so, MDD. Further progress can only be achieved when phenomenological, cognitive, and neuroimaging research efforts go hand-in-hand,” concluded Dr. Toh of Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Find the full review in the Journal of Affective Disorders (May 28, 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.040]).

Research into auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) is lacking in several important ways, according to a systematic review by Dr. Wei Lin Toh and associates.

While previous research indicates that a significant number of people with BD and MDD experience AVH, estimates vary widely, from 11.3% to 62.8% of BD patients, and 5.4% to 40.6% of MDD patients. One neuroimaging study found potential frontotemporal connectivity relating to AVH in bipolar patients.

No study has systematically investigated phenomenological characteristics of AVH in BD and MDD, a significant gap in knowledge relating to AVH in the two disorders. In addition, the investigators recommend research into links between AVH and delusions, as many BD patients and MDD patients experience both delusions and hallucinations of any sort.

“The topic of AVH remains a central but largely understudied symptom in BD, and more so, MDD. Further progress can only be achieved when phenomenological, cognitive, and neuroimaging research efforts go hand-in-hand,” concluded Dr. Toh of Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Find the full review in the Journal of Affective Disorders (May 28, 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.040]).

Bipolar disorder patients may underestimate their sleep quality

MIAMI BEACH – Patients with active bipolar disorder significantly underestimated the quality of their sleep, despite having sleep quality comparable to that of healthy controls.

Sleep complaints are common among individuals with bipolar disorder, and addressing disruptive and troubling sleep problems can be an important component of treating bipolar disorder, noted Dr. Venkatesh Krishnamurthy and his collaborators at Penn State University (Hershey, Pa.).

“Mood state may affect perception of sleep, and the impact of mood state on subjective-objective differences of sleep parameters needs to be further explored,” the researchers noted.

They reported their comparison of subjective and objective measures of sleep for symptomatic patients with bipolar disorder in a poster presentation at a meeting of the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

The study researchers evaluated 30 individuals with symptomatic bipolar disorder, compared with 31 healthy controls, reported Dr. Krishnamurthy, assistant professor at the department of psychiatry’s Sleep Research and Treatment Center at Penn State’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Patients with bipolar disorder were inpatients or in a partial hospitalization program; 11 patients had bipolar depression, 18 had mixed-state bipolar disorder, and 1 had bipolar disorder with a manic episode, Dr. Krishnamurthy said in an interview.

To compare subjective and objective measures of sleep in the two groups, the researchers administered a sleep-quality questionnaire and used actigraphy to document sleep objectively.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the instrument used for subjective assessment, is a self-reporting tool that asks patients to report on aspects of sleep quality, usual sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, and sleep medication use over the past month.

The actigraphs used in the study used accelerometers to measure patient movement at a per-second level, and were worn around the clock for the week of the study. These devices, said Dr. Krishnamurthy, give sleep data that correlate well with polysomnography, the gold standard for sleep assessment.

For both patient groups, Dr. Krishnamurthy and his colleagues reported sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep dysfunction, sleep efficiency in percentage, sleep quality, and medication need as assessed by the PSQI, as well as the overall PSQI score.

The group with bipolar disorder reported a mean time to falling asleep of 61 minutes, compared with 14 minutes for the control group (P = 0.00064). Total sleep duration from the PSQI was 6.2 hours in the bipolar disorder patients, compared with 7.4 hours in the control group (P = 0.017). All other subjective measures of sleep quality were significantly worse for the patients with bipolar disorder, and the overall score on the PSQI was also much higher (worse), compared with the control group (11.7 vs 3.3, P = 1 x 10-11).

Actigraphy was used for a 1-week period to measure sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and number and length of awakenings for both groups. When measured objectively, there was no significant difference in the time it took to fall asleep between the patients with bipolar disorder and the healthy controls (14.64 minutes vs. 13.15 minutes), nor was there a significant difference in total sleep time (400.7 minutes vs. 413 minutes). Overall sleep efficiency was similar between groups.

The absolute difference in sleep duration, latency, and efficiency between subjective and objective measures was compared between groups. There was significantly less difference between objective and subjective ratings of all three sleep measures in the healthy subjects than in those with bipolar disorder.

Overall, the patients with bipolar disorder exhibited a strong perception of poor sleep quality, daytime impairment, and insufficient sleep, as shown by the PSQI scores for this group in comparison with the healthy controls. However, these perceptions did not correlate with objective sleep measures for sleep latency, total sleep duration, or sleep efficiency.

Patients with bipolar disorder were significantly more likely to lack employment and to be smokers or use illicit substances; their body mass index was also significantly higher on average than their healthy counterparts.

The bipolar disorder patients may have altered circadian rhythms, cognitive dysfunction because of the illness, and dysfunctional sleep beliefs, which may have independent effects on subjective perceptions of sleep that were not accounted for in the study, said Dr. Krishnamurthy.

The study’s findings mean that clinicians may wish to consider incorporating objective assessments of sleep, such as actigraphy, into care of individuals with bipolar disorder and sleep disturbances, Dr. Krishnamurthy said in an interview. In addition, “behavioral methods to address sleep misperception may be helpful in bipolar subjects.”

The Penn State Hershey College of Medicine funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Patients with active bipolar disorder significantly underestimated the quality of their sleep, despite having sleep quality comparable to that of healthy controls.

Sleep complaints are common among individuals with bipolar disorder, and addressing disruptive and troubling sleep problems can be an important component of treating bipolar disorder, noted Dr. Venkatesh Krishnamurthy and his collaborators at Penn State University (Hershey, Pa.).

“Mood state may affect perception of sleep, and the impact of mood state on subjective-objective differences of sleep parameters needs to be further explored,” the researchers noted.

They reported their comparison of subjective and objective measures of sleep for symptomatic patients with bipolar disorder in a poster presentation at a meeting of the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

The study researchers evaluated 30 individuals with symptomatic bipolar disorder, compared with 31 healthy controls, reported Dr. Krishnamurthy, assistant professor at the department of psychiatry’s Sleep Research and Treatment Center at Penn State’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Patients with bipolar disorder were inpatients or in a partial hospitalization program; 11 patients had bipolar depression, 18 had mixed-state bipolar disorder, and 1 had bipolar disorder with a manic episode, Dr. Krishnamurthy said in an interview.

To compare subjective and objective measures of sleep in the two groups, the researchers administered a sleep-quality questionnaire and used actigraphy to document sleep objectively.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the instrument used for subjective assessment, is a self-reporting tool that asks patients to report on aspects of sleep quality, usual sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, and sleep medication use over the past month.

The actigraphs used in the study used accelerometers to measure patient movement at a per-second level, and were worn around the clock for the week of the study. These devices, said Dr. Krishnamurthy, give sleep data that correlate well with polysomnography, the gold standard for sleep assessment.

For both patient groups, Dr. Krishnamurthy and his colleagues reported sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep dysfunction, sleep efficiency in percentage, sleep quality, and medication need as assessed by the PSQI, as well as the overall PSQI score.

The group with bipolar disorder reported a mean time to falling asleep of 61 minutes, compared with 14 minutes for the control group (P = 0.00064). Total sleep duration from the PSQI was 6.2 hours in the bipolar disorder patients, compared with 7.4 hours in the control group (P = 0.017). All other subjective measures of sleep quality were significantly worse for the patients with bipolar disorder, and the overall score on the PSQI was also much higher (worse), compared with the control group (11.7 vs 3.3, P = 1 x 10-11).

Actigraphy was used for a 1-week period to measure sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and number and length of awakenings for both groups. When measured objectively, there was no significant difference in the time it took to fall asleep between the patients with bipolar disorder and the healthy controls (14.64 minutes vs. 13.15 minutes), nor was there a significant difference in total sleep time (400.7 minutes vs. 413 minutes). Overall sleep efficiency was similar between groups.

The absolute difference in sleep duration, latency, and efficiency between subjective and objective measures was compared between groups. There was significantly less difference between objective and subjective ratings of all three sleep measures in the healthy subjects than in those with bipolar disorder.

Overall, the patients with bipolar disorder exhibited a strong perception of poor sleep quality, daytime impairment, and insufficient sleep, as shown by the PSQI scores for this group in comparison with the healthy controls. However, these perceptions did not correlate with objective sleep measures for sleep latency, total sleep duration, or sleep efficiency.

Patients with bipolar disorder were significantly more likely to lack employment and to be smokers or use illicit substances; their body mass index was also significantly higher on average than their healthy counterparts.

The bipolar disorder patients may have altered circadian rhythms, cognitive dysfunction because of the illness, and dysfunctional sleep beliefs, which may have independent effects on subjective perceptions of sleep that were not accounted for in the study, said Dr. Krishnamurthy.

The study’s findings mean that clinicians may wish to consider incorporating objective assessments of sleep, such as actigraphy, into care of individuals with bipolar disorder and sleep disturbances, Dr. Krishnamurthy said in an interview. In addition, “behavioral methods to address sleep misperception may be helpful in bipolar subjects.”

The Penn State Hershey College of Medicine funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

MIAMI BEACH – Patients with active bipolar disorder significantly underestimated the quality of their sleep, despite having sleep quality comparable to that of healthy controls.

Sleep complaints are common among individuals with bipolar disorder, and addressing disruptive and troubling sleep problems can be an important component of treating bipolar disorder, noted Dr. Venkatesh Krishnamurthy and his collaborators at Penn State University (Hershey, Pa.).

“Mood state may affect perception of sleep, and the impact of mood state on subjective-objective differences of sleep parameters needs to be further explored,” the researchers noted.

They reported their comparison of subjective and objective measures of sleep for symptomatic patients with bipolar disorder in a poster presentation at a meeting of the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

The study researchers evaluated 30 individuals with symptomatic bipolar disorder, compared with 31 healthy controls, reported Dr. Krishnamurthy, assistant professor at the department of psychiatry’s Sleep Research and Treatment Center at Penn State’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Patients with bipolar disorder were inpatients or in a partial hospitalization program; 11 patients had bipolar depression, 18 had mixed-state bipolar disorder, and 1 had bipolar disorder with a manic episode, Dr. Krishnamurthy said in an interview.

To compare subjective and objective measures of sleep in the two groups, the researchers administered a sleep-quality questionnaire and used actigraphy to document sleep objectively.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the instrument used for subjective assessment, is a self-reporting tool that asks patients to report on aspects of sleep quality, usual sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, and sleep medication use over the past month.

The actigraphs used in the study used accelerometers to measure patient movement at a per-second level, and were worn around the clock for the week of the study. These devices, said Dr. Krishnamurthy, give sleep data that correlate well with polysomnography, the gold standard for sleep assessment.

For both patient groups, Dr. Krishnamurthy and his colleagues reported sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep dysfunction, sleep efficiency in percentage, sleep quality, and medication need as assessed by the PSQI, as well as the overall PSQI score.

The group with bipolar disorder reported a mean time to falling asleep of 61 minutes, compared with 14 minutes for the control group (P = 0.00064). Total sleep duration from the PSQI was 6.2 hours in the bipolar disorder patients, compared with 7.4 hours in the control group (P = 0.017). All other subjective measures of sleep quality were significantly worse for the patients with bipolar disorder, and the overall score on the PSQI was also much higher (worse), compared with the control group (11.7 vs 3.3, P = 1 x 10-11).

Actigraphy was used for a 1-week period to measure sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and number and length of awakenings for both groups. When measured objectively, there was no significant difference in the time it took to fall asleep between the patients with bipolar disorder and the healthy controls (14.64 minutes vs. 13.15 minutes), nor was there a significant difference in total sleep time (400.7 minutes vs. 413 minutes). Overall sleep efficiency was similar between groups.

The absolute difference in sleep duration, latency, and efficiency between subjective and objective measures was compared between groups. There was significantly less difference between objective and subjective ratings of all three sleep measures in the healthy subjects than in those with bipolar disorder.

Overall, the patients with bipolar disorder exhibited a strong perception of poor sleep quality, daytime impairment, and insufficient sleep, as shown by the PSQI scores for this group in comparison with the healthy controls. However, these perceptions did not correlate with objective sleep measures for sleep latency, total sleep duration, or sleep efficiency.

Patients with bipolar disorder were significantly more likely to lack employment and to be smokers or use illicit substances; their body mass index was also significantly higher on average than their healthy counterparts.

The bipolar disorder patients may have altered circadian rhythms, cognitive dysfunction because of the illness, and dysfunctional sleep beliefs, which may have independent effects on subjective perceptions of sleep that were not accounted for in the study, said Dr. Krishnamurthy.

The study’s findings mean that clinicians may wish to consider incorporating objective assessments of sleep, such as actigraphy, into care of individuals with bipolar disorder and sleep disturbances, Dr. Krishnamurthy said in an interview. In addition, “behavioral methods to address sleep misperception may be helpful in bipolar subjects.”

The Penn State Hershey College of Medicine funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

AT THE ASCP Annual Meeting

Key clinical point: Subjective assessment of sleep efficiency and duration varied significantly from actigraphy in active bipolar disorder.

Major finding: Individuals with active bipolar disorder greatly overestimated sleep latency and underestimated sleep duration, reporting significantly worse sleep than healthy subjects, who were more accurate in subjective sleep assessment.

Data source: Subjective assessment via Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and objective measurement via actigraphy of 1 week of sleep for 30 individuals with active bipolar disorder (inpatients or partial hospitalization patients), compared with 31 healthy controls.

Disclosures: The Penn State Hershey College of Medicine funded the study. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

ASCP: Variable pattern of inflammation markers found in serious mental illness

MIAMI BEACH – Elevated levels of the same cytokine* were seen in three serious mental illnesses, but each illness had separate and distinct patterns of inflammatory markers, according to a study of immune function and mental illness.

Dr. David R. Goldsmith and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis that pooled results of three dozen studies of outpatients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression, to search for commonalities and differences in immune system activation.

The results were presented in a poster session at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

Dr. Goldsmith, chief resident for the research track at Emory University’s department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Atlanta, and his collaborators looked at 36 studies examining individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) (12 studies), euthymic bipolar disorder (14 studies), and chronic schizophrenia (10 studies). It is the first meta-analysis to pool results from studies of blood cytokine levels in outpatients with three serious mental illnesses, he said.

Serious mental illness is associated with immune activation, and previous studies have found activation of various cytokines in many mental illnesses. In the acute phase of mental illness, elevations have been found in both interleukin-6 (IL-6) and the cytokine receptor SIL-2R; for MDD and schizophrenia, cytokine levels are acutely increased, tend to decrease with treatment, and eventually rise again, he said.

However, Dr. Goldsmith and his collaborators found that only the cytokine* IL-6 was significantly elevated, compared with healthy controls, for all three illnesses included in the meta-analysis (P < .01 for all). IL-6 is associated with acute and chronic inflammation. For MDD and schizophrenia, two other cytokines were significantly elevated in the meta-analysis: the soluble IL-2 receptor (SIL–2R), a cytokine receptor associated with T-cell activation; and IL-1 beta, a cytokine produced by activated macrophages (P < .01 for all interactions, except P = .01 for IL-1 beta in bipolar disorder.)

For all three disorders, several inflammatory cytokines were significantly elevated, compared with healthy subjects.

Dr. Goldsmith noted some limitations of the meta-analysis. For example, there was a high degree of variability across studies in collection and storage techniques. In addition, no consistent set of tests exists to assess inflammation in mental illness, so the measures obtained varied from study to study. Potential confounders such as smoking and substance abuse were difficult to account for as well. The study limitations highlight the need for “a common set of inflammatory markers that must carefully be studied in order to understand the role of the cytokines in chronic psychiatric disorders and inform novel treatment decisions that may only be relevant to a subset of patients,” he noted.

Going forward, more uniform data collection and larger datasets should help delineate the association between inflammation and serious mental illness. “Despite the heterogeneity of the data, we do see some signal for the role of persistent immune activation, which we think will be important for some people with mental illness,” Dr. Goldsmith said in an interview.Dr. Goldsmith received the Janssen Pharmaceuticals Academic Research Mentoring Award in 2014. He reported no other conflicts of interest.

*Correction, 7/10/2015: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized an inflammatory marker. IL-6 is a cytokine.

On Twitter @karioakes

MIAMI BEACH – Elevated levels of the same cytokine* were seen in three serious mental illnesses, but each illness had separate and distinct patterns of inflammatory markers, according to a study of immune function and mental illness.

Dr. David R. Goldsmith and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis that pooled results of three dozen studies of outpatients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression, to search for commonalities and differences in immune system activation.

The results were presented in a poster session at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

Dr. Goldsmith, chief resident for the research track at Emory University’s department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Atlanta, and his collaborators looked at 36 studies examining individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) (12 studies), euthymic bipolar disorder (14 studies), and chronic schizophrenia (10 studies). It is the first meta-analysis to pool results from studies of blood cytokine levels in outpatients with three serious mental illnesses, he said.

Serious mental illness is associated with immune activation, and previous studies have found activation of various cytokines in many mental illnesses. In the acute phase of mental illness, elevations have been found in both interleukin-6 (IL-6) and the cytokine receptor SIL-2R; for MDD and schizophrenia, cytokine levels are acutely increased, tend to decrease with treatment, and eventually rise again, he said.

However, Dr. Goldsmith and his collaborators found that only the cytokine* IL-6 was significantly elevated, compared with healthy controls, for all three illnesses included in the meta-analysis (P < .01 for all). IL-6 is associated with acute and chronic inflammation. For MDD and schizophrenia, two other cytokines were significantly elevated in the meta-analysis: the soluble IL-2 receptor (SIL–2R), a cytokine receptor associated with T-cell activation; and IL-1 beta, a cytokine produced by activated macrophages (P < .01 for all interactions, except P = .01 for IL-1 beta in bipolar disorder.)

For all three disorders, several inflammatory cytokines were significantly elevated, compared with healthy subjects.

Dr. Goldsmith noted some limitations of the meta-analysis. For example, there was a high degree of variability across studies in collection and storage techniques. In addition, no consistent set of tests exists to assess inflammation in mental illness, so the measures obtained varied from study to study. Potential confounders such as smoking and substance abuse were difficult to account for as well. The study limitations highlight the need for “a common set of inflammatory markers that must carefully be studied in order to understand the role of the cytokines in chronic psychiatric disorders and inform novel treatment decisions that may only be relevant to a subset of patients,” he noted.

Going forward, more uniform data collection and larger datasets should help delineate the association between inflammation and serious mental illness. “Despite the heterogeneity of the data, we do see some signal for the role of persistent immune activation, which we think will be important for some people with mental illness,” Dr. Goldsmith said in an interview.Dr. Goldsmith received the Janssen Pharmaceuticals Academic Research Mentoring Award in 2014. He reported no other conflicts of interest.

*Correction, 7/10/2015: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized an inflammatory marker. IL-6 is a cytokine.

On Twitter @karioakes

MIAMI BEACH – Elevated levels of the same cytokine* were seen in three serious mental illnesses, but each illness had separate and distinct patterns of inflammatory markers, according to a study of immune function and mental illness.

Dr. David R. Goldsmith and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis that pooled results of three dozen studies of outpatients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression, to search for commonalities and differences in immune system activation.

The results were presented in a poster session at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

Dr. Goldsmith, chief resident for the research track at Emory University’s department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Atlanta, and his collaborators looked at 36 studies examining individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) (12 studies), euthymic bipolar disorder (14 studies), and chronic schizophrenia (10 studies). It is the first meta-analysis to pool results from studies of blood cytokine levels in outpatients with three serious mental illnesses, he said.

Serious mental illness is associated with immune activation, and previous studies have found activation of various cytokines in many mental illnesses. In the acute phase of mental illness, elevations have been found in both interleukin-6 (IL-6) and the cytokine receptor SIL-2R; for MDD and schizophrenia, cytokine levels are acutely increased, tend to decrease with treatment, and eventually rise again, he said.

However, Dr. Goldsmith and his collaborators found that only the cytokine* IL-6 was significantly elevated, compared with healthy controls, for all three illnesses included in the meta-analysis (P < .01 for all). IL-6 is associated with acute and chronic inflammation. For MDD and schizophrenia, two other cytokines were significantly elevated in the meta-analysis: the soluble IL-2 receptor (SIL–2R), a cytokine receptor associated with T-cell activation; and IL-1 beta, a cytokine produced by activated macrophages (P < .01 for all interactions, except P = .01 for IL-1 beta in bipolar disorder.)

For all three disorders, several inflammatory cytokines were significantly elevated, compared with healthy subjects.

Dr. Goldsmith noted some limitations of the meta-analysis. For example, there was a high degree of variability across studies in collection and storage techniques. In addition, no consistent set of tests exists to assess inflammation in mental illness, so the measures obtained varied from study to study. Potential confounders such as smoking and substance abuse were difficult to account for as well. The study limitations highlight the need for “a common set of inflammatory markers that must carefully be studied in order to understand the role of the cytokines in chronic psychiatric disorders and inform novel treatment decisions that may only be relevant to a subset of patients,” he noted.

Going forward, more uniform data collection and larger datasets should help delineate the association between inflammation and serious mental illness. “Despite the heterogeneity of the data, we do see some signal for the role of persistent immune activation, which we think will be important for some people with mental illness,” Dr. Goldsmith said in an interview.Dr. Goldsmith received the Janssen Pharmaceuticals Academic Research Mentoring Award in 2014. He reported no other conflicts of interest.

*Correction, 7/10/2015: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized an inflammatory marker. IL-6 is a cytokine.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ASCP ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A meta-analysis found elevations in the cytokine receptor interleukin-6 (IL-6) in outpatients with three serious mental illnesses.

Major finding: The cytokine* IL-6 was significantly elevated in major depressive disorder, chronic schizophrenia, and euthymic bipolar disorder (P < .01); variable patterns of inflammation were seen in the individual disorders.

Data source: Meta-analysis of 36 studies of blood cytokine levels in chronically ill patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression.

Disclosures: Dr. Goldsmith received the Janssen Pharmaceuticals Academic Research Mentoring Award in 2014. He reported no other conflicts of interest.