User login

3-Month paliperidone palmitate for preventing relapse in schizophrenia

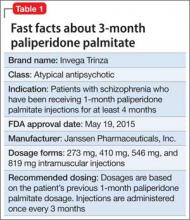

A 3-month paliperidone palmitate (PPM-3) extended-release injectable suspension was approved by the FDA in May 2015 for preventing relapse among patients with schizophrenia, under the brand name Invega Trinza (Table 1). Administered 4 times a year, PPM-3 provides the longest interval of any approved long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAIA). PPM-3 can be administered to patients with schizophrenia who have been taking 1-month paliperidone palmitate (PPM-1) extended-release injectable suspension (brand name, Invega Sustenna), once a month, for at least 4 months.

How it works

PPM-3 is a LAIA injection. Because of its low solubility in water, paliperidone palmitate dissolves slowly once injected before being hydrolyzed as paliperidone and absorbed into the bloodstream. From time of release on Day 1, PPM-3 remains active for as long 18 months.

PPM-3 reaches a maximum plasma concentration between Day 30 and Day 33. In clinical trials, PPM-3 had a median half-life of 84 to 95 days when injected into the deltoid muscle and a median half-life of 118 to 139 days when injected into the gluteal muscle.

Paliperidone is not extensively metabolized in the liver. Although results of a study suggest that cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and CYP3A4 might play a role in metabolizing paliperidone, there is no evidence that it has a significant role.

Dosing and administration

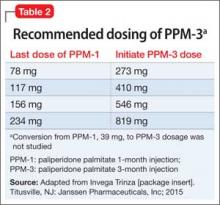

PPM-3 is administered intramuscularly by a licensed health care professional, once every 3 months. The recommended dosage is based on the patient’s previous dosage of PPM-1 (Table 2).

See the prescribing information for administration instructions.

Efficacy

The efficacy of PPM-3 was assessed in a long-term double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized-withdrawal trial in adult patients with acute symptoms (previously treated with an oral antipsychotic) or adequately treated with a LAIA, either PPM-1 or another agent; patients receiving PPM-1, 39 mg, injections were ineligible. All patients entering the study received PPM-1 in place of the next scheduled injection.

The study comprised 3 treatment periods:

• 17-Week flexible-dose open-label period with PPM-1 (ie, first part of a 29-week open-label stabilization phase): Patients (N = 506) received PPM-1 with a flexible dose based on symptom response, tolerability, and medication history. Patients had to achieve a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of <70 at Week 17 to enter the second phase.

• 12-Week open-label with PPM-3 (ie, second part of the 29-week open-label stabilization phase): Patients (N = 379) received a single injection of PPM-3 that was 3.5 times the last dose of PPM-1. Patients had to achieve a PANSS total score of <70 and ≤4 for 7 specific PANSS items.

• A variable length double-blind treatment period: Patients (N = 305) were randomized 1:1 to continue treatment with PPM-3 (273 mg, 410 mg, 546 mg, or 819 mg) or placebo (administered once every 12 weeks) until relapse, early withdrawal, or end of the study. The primary efficacy measure was time to first relapse, defined as psychiatric hospitalization, ≥25% increase or a 10-point increase in total PANSS score on 2 consecutive assessments, deliberate self-injury, violent behavior, suicidal or homicidal ideation, or a score of ≥5 (if the maximum baseline score was ≤3) or ≥6 (if the maximum baseline score was 4) on 2 consecutive assessments of the specific PANSS items.

Among the patients in the third treatment period, 23% of those who received placebo and 7.4% of those who received PPM-3 experienced a relapse event. The time to relapse was significantly longer for patients who received PPM-3 than for those who received placebo.

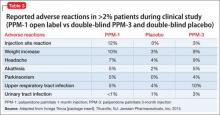

See Table 3 for adverse reactions reported in patients who received PPM-3 and those taking placebo in the study.

Contraindications

Allergic reactions. Patients who have a hypersensitivity to paliperidone, risperidone, or their components should not receive PPM-3. Anaphylactic reactions have been reported in patients who previously tolerated risperidone or oral paliperidone, which could be significant because the drug is slowly released over 3 months. Other adverse reactions, including angioedema, ileus, swollen tongue, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, urinary incontinence, and urinary retention, were reported post-approval of paliperidone; however, these adverse effects were reported voluntarily from an unknown population size and, therefore, it is unknown whether there is a causal relationship to the drug or its frequency.

Drug-drug interactions. Although paliperidone is not expected to cause drug– drug interactions with medications that are metabolized by CYP isoenzymes, it is recommended to avoid using a strong inducer of CYP3A4 and/or P-glycoprotein.

Overdose. When assessing treatment options and recovery, consider the half-life of PPM-3 and its long-lasting effects.

Because PPM-3 is administered by a licensed health care provider, the potential for overdose is low. However, if overdose occurs, general treatment and management measures should be employed as with overdose of any drug and the possibility of multiple drug overdose should be considered. There is no specific antidote to paliperidone. Contact a certified poison control center for guidance on managing paliperidone and PPM-3 overdose. Generally, management consists of supportive care.

Black-box warning in dementia. As with all atypical antipsychotics, the black-box warning for PPM-3 states that it is not approved for, and should not be used in, patients with dementia-related psychosis. An analysis of placebo-controlled studies revealed that patients taking an antipsychotic had (1) 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death than those who received placebo and (2) a higher incidence of cerebrovascular adverse reactions.

Adverse reactions

The safety profile of PPM-3 is similar to that of PPM-1. The most common adverse reactions are:

• reaction at the injection site

• weight gain

• headache

• upper respiratory tract infection

• akathisia

• parkinsonism.

See the full prescribing information for a complete list of adverse effects.

Related Resources

• Sedky K, Nazir R, Lindenmayer JP, et al. Paliperidone palmitate: once monthly treatment option for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):48-49.

• Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial [published online March 29, 2015]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0241.

Drug Brand Names

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna, Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Source: Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2015.

A 3-month paliperidone palmitate (PPM-3) extended-release injectable suspension was approved by the FDA in May 2015 for preventing relapse among patients with schizophrenia, under the brand name Invega Trinza (Table 1). Administered 4 times a year, PPM-3 provides the longest interval of any approved long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAIA). PPM-3 can be administered to patients with schizophrenia who have been taking 1-month paliperidone palmitate (PPM-1) extended-release injectable suspension (brand name, Invega Sustenna), once a month, for at least 4 months.

How it works

PPM-3 is a LAIA injection. Because of its low solubility in water, paliperidone palmitate dissolves slowly once injected before being hydrolyzed as paliperidone and absorbed into the bloodstream. From time of release on Day 1, PPM-3 remains active for as long 18 months.

PPM-3 reaches a maximum plasma concentration between Day 30 and Day 33. In clinical trials, PPM-3 had a median half-life of 84 to 95 days when injected into the deltoid muscle and a median half-life of 118 to 139 days when injected into the gluteal muscle.

Paliperidone is not extensively metabolized in the liver. Although results of a study suggest that cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and CYP3A4 might play a role in metabolizing paliperidone, there is no evidence that it has a significant role.

Dosing and administration

PPM-3 is administered intramuscularly by a licensed health care professional, once every 3 months. The recommended dosage is based on the patient’s previous dosage of PPM-1 (Table 2).

See the prescribing information for administration instructions.

Efficacy

The efficacy of PPM-3 was assessed in a long-term double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized-withdrawal trial in adult patients with acute symptoms (previously treated with an oral antipsychotic) or adequately treated with a LAIA, either PPM-1 or another agent; patients receiving PPM-1, 39 mg, injections were ineligible. All patients entering the study received PPM-1 in place of the next scheduled injection.

The study comprised 3 treatment periods:

• 17-Week flexible-dose open-label period with PPM-1 (ie, first part of a 29-week open-label stabilization phase): Patients (N = 506) received PPM-1 with a flexible dose based on symptom response, tolerability, and medication history. Patients had to achieve a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of <70 at Week 17 to enter the second phase.

• 12-Week open-label with PPM-3 (ie, second part of the 29-week open-label stabilization phase): Patients (N = 379) received a single injection of PPM-3 that was 3.5 times the last dose of PPM-1. Patients had to achieve a PANSS total score of <70 and ≤4 for 7 specific PANSS items.

• A variable length double-blind treatment period: Patients (N = 305) were randomized 1:1 to continue treatment with PPM-3 (273 mg, 410 mg, 546 mg, or 819 mg) or placebo (administered once every 12 weeks) until relapse, early withdrawal, or end of the study. The primary efficacy measure was time to first relapse, defined as psychiatric hospitalization, ≥25% increase or a 10-point increase in total PANSS score on 2 consecutive assessments, deliberate self-injury, violent behavior, suicidal or homicidal ideation, or a score of ≥5 (if the maximum baseline score was ≤3) or ≥6 (if the maximum baseline score was 4) on 2 consecutive assessments of the specific PANSS items.

Among the patients in the third treatment period, 23% of those who received placebo and 7.4% of those who received PPM-3 experienced a relapse event. The time to relapse was significantly longer for patients who received PPM-3 than for those who received placebo.

See Table 3 for adverse reactions reported in patients who received PPM-3 and those taking placebo in the study.

Contraindications

Allergic reactions. Patients who have a hypersensitivity to paliperidone, risperidone, or their components should not receive PPM-3. Anaphylactic reactions have been reported in patients who previously tolerated risperidone or oral paliperidone, which could be significant because the drug is slowly released over 3 months. Other adverse reactions, including angioedema, ileus, swollen tongue, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, urinary incontinence, and urinary retention, were reported post-approval of paliperidone; however, these adverse effects were reported voluntarily from an unknown population size and, therefore, it is unknown whether there is a causal relationship to the drug or its frequency.

Drug-drug interactions. Although paliperidone is not expected to cause drug– drug interactions with medications that are metabolized by CYP isoenzymes, it is recommended to avoid using a strong inducer of CYP3A4 and/or P-glycoprotein.

Overdose. When assessing treatment options and recovery, consider the half-life of PPM-3 and its long-lasting effects.

Because PPM-3 is administered by a licensed health care provider, the potential for overdose is low. However, if overdose occurs, general treatment and management measures should be employed as with overdose of any drug and the possibility of multiple drug overdose should be considered. There is no specific antidote to paliperidone. Contact a certified poison control center for guidance on managing paliperidone and PPM-3 overdose. Generally, management consists of supportive care.

Black-box warning in dementia. As with all atypical antipsychotics, the black-box warning for PPM-3 states that it is not approved for, and should not be used in, patients with dementia-related psychosis. An analysis of placebo-controlled studies revealed that patients taking an antipsychotic had (1) 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death than those who received placebo and (2) a higher incidence of cerebrovascular adverse reactions.

Adverse reactions

The safety profile of PPM-3 is similar to that of PPM-1. The most common adverse reactions are:

• reaction at the injection site

• weight gain

• headache

• upper respiratory tract infection

• akathisia

• parkinsonism.

See the full prescribing information for a complete list of adverse effects.

Related Resources

• Sedky K, Nazir R, Lindenmayer JP, et al. Paliperidone palmitate: once monthly treatment option for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):48-49.

• Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial [published online March 29, 2015]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0241.

Drug Brand Names

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna, Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

A 3-month paliperidone palmitate (PPM-3) extended-release injectable suspension was approved by the FDA in May 2015 for preventing relapse among patients with schizophrenia, under the brand name Invega Trinza (Table 1). Administered 4 times a year, PPM-3 provides the longest interval of any approved long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAIA). PPM-3 can be administered to patients with schizophrenia who have been taking 1-month paliperidone palmitate (PPM-1) extended-release injectable suspension (brand name, Invega Sustenna), once a month, for at least 4 months.

How it works

PPM-3 is a LAIA injection. Because of its low solubility in water, paliperidone palmitate dissolves slowly once injected before being hydrolyzed as paliperidone and absorbed into the bloodstream. From time of release on Day 1, PPM-3 remains active for as long 18 months.

PPM-3 reaches a maximum plasma concentration between Day 30 and Day 33. In clinical trials, PPM-3 had a median half-life of 84 to 95 days when injected into the deltoid muscle and a median half-life of 118 to 139 days when injected into the gluteal muscle.

Paliperidone is not extensively metabolized in the liver. Although results of a study suggest that cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and CYP3A4 might play a role in metabolizing paliperidone, there is no evidence that it has a significant role.

Dosing and administration

PPM-3 is administered intramuscularly by a licensed health care professional, once every 3 months. The recommended dosage is based on the patient’s previous dosage of PPM-1 (Table 2).

See the prescribing information for administration instructions.

Efficacy

The efficacy of PPM-3 was assessed in a long-term double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized-withdrawal trial in adult patients with acute symptoms (previously treated with an oral antipsychotic) or adequately treated with a LAIA, either PPM-1 or another agent; patients receiving PPM-1, 39 mg, injections were ineligible. All patients entering the study received PPM-1 in place of the next scheduled injection.

The study comprised 3 treatment periods:

• 17-Week flexible-dose open-label period with PPM-1 (ie, first part of a 29-week open-label stabilization phase): Patients (N = 506) received PPM-1 with a flexible dose based on symptom response, tolerability, and medication history. Patients had to achieve a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of <70 at Week 17 to enter the second phase.

• 12-Week open-label with PPM-3 (ie, second part of the 29-week open-label stabilization phase): Patients (N = 379) received a single injection of PPM-3 that was 3.5 times the last dose of PPM-1. Patients had to achieve a PANSS total score of <70 and ≤4 for 7 specific PANSS items.

• A variable length double-blind treatment period: Patients (N = 305) were randomized 1:1 to continue treatment with PPM-3 (273 mg, 410 mg, 546 mg, or 819 mg) or placebo (administered once every 12 weeks) until relapse, early withdrawal, or end of the study. The primary efficacy measure was time to first relapse, defined as psychiatric hospitalization, ≥25% increase or a 10-point increase in total PANSS score on 2 consecutive assessments, deliberate self-injury, violent behavior, suicidal or homicidal ideation, or a score of ≥5 (if the maximum baseline score was ≤3) or ≥6 (if the maximum baseline score was 4) on 2 consecutive assessments of the specific PANSS items.

Among the patients in the third treatment period, 23% of those who received placebo and 7.4% of those who received PPM-3 experienced a relapse event. The time to relapse was significantly longer for patients who received PPM-3 than for those who received placebo.

See Table 3 for adverse reactions reported in patients who received PPM-3 and those taking placebo in the study.

Contraindications

Allergic reactions. Patients who have a hypersensitivity to paliperidone, risperidone, or their components should not receive PPM-3. Anaphylactic reactions have been reported in patients who previously tolerated risperidone or oral paliperidone, which could be significant because the drug is slowly released over 3 months. Other adverse reactions, including angioedema, ileus, swollen tongue, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, urinary incontinence, and urinary retention, were reported post-approval of paliperidone; however, these adverse effects were reported voluntarily from an unknown population size and, therefore, it is unknown whether there is a causal relationship to the drug or its frequency.

Drug-drug interactions. Although paliperidone is not expected to cause drug– drug interactions with medications that are metabolized by CYP isoenzymes, it is recommended to avoid using a strong inducer of CYP3A4 and/or P-glycoprotein.

Overdose. When assessing treatment options and recovery, consider the half-life of PPM-3 and its long-lasting effects.

Because PPM-3 is administered by a licensed health care provider, the potential for overdose is low. However, if overdose occurs, general treatment and management measures should be employed as with overdose of any drug and the possibility of multiple drug overdose should be considered. There is no specific antidote to paliperidone. Contact a certified poison control center for guidance on managing paliperidone and PPM-3 overdose. Generally, management consists of supportive care.

Black-box warning in dementia. As with all atypical antipsychotics, the black-box warning for PPM-3 states that it is not approved for, and should not be used in, patients with dementia-related psychosis. An analysis of placebo-controlled studies revealed that patients taking an antipsychotic had (1) 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death than those who received placebo and (2) a higher incidence of cerebrovascular adverse reactions.

Adverse reactions

The safety profile of PPM-3 is similar to that of PPM-1. The most common adverse reactions are:

• reaction at the injection site

• weight gain

• headache

• upper respiratory tract infection

• akathisia

• parkinsonism.

See the full prescribing information for a complete list of adverse effects.

Related Resources

• Sedky K, Nazir R, Lindenmayer JP, et al. Paliperidone palmitate: once monthly treatment option for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):48-49.

• Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial [published online March 29, 2015]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0241.

Drug Brand Names

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna, Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Source: Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2015.

Source: Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2015.

Asenapine for pediatric bipolar disorder: New indication

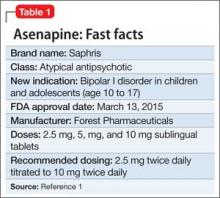

Asenapine an atypical antipsychotic sold under the brand name Saphris, was granted a second, pediatric indication by the FDA in March 2015 as monotherapy for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents age 10 to 17 (Table 1).1 (Asenapine was first approved in August 2009 as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate in adults for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.1,2)

Dosage and administration

Asenapine is available as 2.5-, 5-, and 10-mg sublingual tablets, the only atypical antipsychotic with this formulation.1 The recommended dosage for the new indication is 2.5 mg twice daily for 3 days, titrated to 5 mg twice daily, titrated again to 10 mg twice daily after 3 days.3 In a phase I study, pediatric patients appeared to be more sensitive to dystonia when the recommended dosage escalation schedule was not followed.3

In clinical trials, drinking water 2 to 5 minutes after taking asenapine decreased exposure to the drug. Instruct patients not to swallow the tablet and to avoid eating and drinking for 10 minutes after administration.3

For full prescribing information for pediatric and adult patients, see Reference 3.

Safety and efficacy

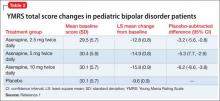

In a 3-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of 403 patients, 302 children and adolescents age 10 to 17 received asenapine at fixed dosages of 2.5 to 10 mg twice daily; the remainder were given placebo. The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score and Clinical Global Impressions Severity of Illness scores of patients who received asenapine improved significantly compared with those who received placebo, as measured by change from baseline to week 3 (Table 2).1

The safety and efficacy of asenapine has not been evaluated in pediatric bipolar disorder patients age ≤10 or pediatric schizophrenia patients age ≤12, or as an adjunctive therapy in pediatric bipolar disorder patients.

Asenapine was not shown to be effective in pediatric patients with schizophrenia in an 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial.

The pharmacokinetics of asenapine in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adults.

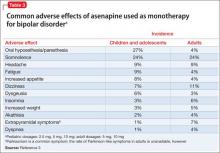

Adverse effects

In pediatric patients, the most common reported adverse effects of asenapine are:

• dizziness

• dysgeusia

• fatigue

• increased appetite

• increased weight

• nausea

• oral paresthesia

• somnolence.

Similar adverse effects were reported in the pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder clinical trials (Table 3).3 A complete list of reported adverse effects is given in the package insert.3

When treating pediatric patients, monitor the child’s weight gain against expected normal weight gain.

Asenapine is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment and those who have a hypersensitivity to asenapine or any components in its formulation.3

1. Actavis receives FDA approval of Saphris for pediatric patients with bipolar I disorder. Drugs.com. http://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/actavis-receivesfda-

approval-saphris-pediatric-patients-bipolardisorder-4188.html. Published March 2015. Accessed June 19, 2015.

2. Lincoln J, Preskon S. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2009;12(8):75-76,83-85.

3. Saphris [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

Asenapine an atypical antipsychotic sold under the brand name Saphris, was granted a second, pediatric indication by the FDA in March 2015 as monotherapy for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents age 10 to 17 (Table 1).1 (Asenapine was first approved in August 2009 as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate in adults for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.1,2)

Dosage and administration

Asenapine is available as 2.5-, 5-, and 10-mg sublingual tablets, the only atypical antipsychotic with this formulation.1 The recommended dosage for the new indication is 2.5 mg twice daily for 3 days, titrated to 5 mg twice daily, titrated again to 10 mg twice daily after 3 days.3 In a phase I study, pediatric patients appeared to be more sensitive to dystonia when the recommended dosage escalation schedule was not followed.3

In clinical trials, drinking water 2 to 5 minutes after taking asenapine decreased exposure to the drug. Instruct patients not to swallow the tablet and to avoid eating and drinking for 10 minutes after administration.3

For full prescribing information for pediatric and adult patients, see Reference 3.

Safety and efficacy

In a 3-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of 403 patients, 302 children and adolescents age 10 to 17 received asenapine at fixed dosages of 2.5 to 10 mg twice daily; the remainder were given placebo. The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score and Clinical Global Impressions Severity of Illness scores of patients who received asenapine improved significantly compared with those who received placebo, as measured by change from baseline to week 3 (Table 2).1

The safety and efficacy of asenapine has not been evaluated in pediatric bipolar disorder patients age ≤10 or pediatric schizophrenia patients age ≤12, or as an adjunctive therapy in pediatric bipolar disorder patients.

Asenapine was not shown to be effective in pediatric patients with schizophrenia in an 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial.

The pharmacokinetics of asenapine in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adults.

Adverse effects

In pediatric patients, the most common reported adverse effects of asenapine are:

• dizziness

• dysgeusia

• fatigue

• increased appetite

• increased weight

• nausea

• oral paresthesia

• somnolence.

Similar adverse effects were reported in the pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder clinical trials (Table 3).3 A complete list of reported adverse effects is given in the package insert.3

When treating pediatric patients, monitor the child’s weight gain against expected normal weight gain.

Asenapine is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment and those who have a hypersensitivity to asenapine or any components in its formulation.3

Asenapine an atypical antipsychotic sold under the brand name Saphris, was granted a second, pediatric indication by the FDA in March 2015 as monotherapy for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents age 10 to 17 (Table 1).1 (Asenapine was first approved in August 2009 as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate in adults for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.1,2)

Dosage and administration

Asenapine is available as 2.5-, 5-, and 10-mg sublingual tablets, the only atypical antipsychotic with this formulation.1 The recommended dosage for the new indication is 2.5 mg twice daily for 3 days, titrated to 5 mg twice daily, titrated again to 10 mg twice daily after 3 days.3 In a phase I study, pediatric patients appeared to be more sensitive to dystonia when the recommended dosage escalation schedule was not followed.3

In clinical trials, drinking water 2 to 5 minutes after taking asenapine decreased exposure to the drug. Instruct patients not to swallow the tablet and to avoid eating and drinking for 10 minutes after administration.3

For full prescribing information for pediatric and adult patients, see Reference 3.

Safety and efficacy

In a 3-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of 403 patients, 302 children and adolescents age 10 to 17 received asenapine at fixed dosages of 2.5 to 10 mg twice daily; the remainder were given placebo. The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score and Clinical Global Impressions Severity of Illness scores of patients who received asenapine improved significantly compared with those who received placebo, as measured by change from baseline to week 3 (Table 2).1

The safety and efficacy of asenapine has not been evaluated in pediatric bipolar disorder patients age ≤10 or pediatric schizophrenia patients age ≤12, or as an adjunctive therapy in pediatric bipolar disorder patients.

Asenapine was not shown to be effective in pediatric patients with schizophrenia in an 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial.

The pharmacokinetics of asenapine in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adults.

Adverse effects

In pediatric patients, the most common reported adverse effects of asenapine are:

• dizziness

• dysgeusia

• fatigue

• increased appetite

• increased weight

• nausea

• oral paresthesia

• somnolence.

Similar adverse effects were reported in the pediatric bipolar disorder and adult bipolar disorder clinical trials (Table 3).3 A complete list of reported adverse effects is given in the package insert.3

When treating pediatric patients, monitor the child’s weight gain against expected normal weight gain.

Asenapine is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment and those who have a hypersensitivity to asenapine or any components in its formulation.3

1. Actavis receives FDA approval of Saphris for pediatric patients with bipolar I disorder. Drugs.com. http://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/actavis-receivesfda-

approval-saphris-pediatric-patients-bipolardisorder-4188.html. Published March 2015. Accessed June 19, 2015.

2. Lincoln J, Preskon S. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2009;12(8):75-76,83-85.

3. Saphris [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

1. Actavis receives FDA approval of Saphris for pediatric patients with bipolar I disorder. Drugs.com. http://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/actavis-receivesfda-

approval-saphris-pediatric-patients-bipolardisorder-4188.html. Published March 2015. Accessed June 19, 2015.

2. Lincoln J, Preskon S. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2009;12(8):75-76,83-85.

3. Saphris [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

Liraglutide for obesity: New indication

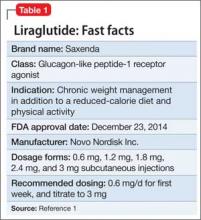

Liraglutide (rDNA origin) injection, approved by the FDA in 2010 for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), has a new formulation and indication for treating obesity in adults as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity (Table 1).1

Liraglutide, recommended dosage 3 mg/d (under the brand name Saxenda), is approved for adults with a body mass index (BMI) ≥30, or those with a BMI of ≥27 and a weight-related condition such as hypertension, T2DM, or high cholesterol.1 (A 1.8-mg formulation, under the brand name Victoza, is FDA-approved for managing T2DM, but is not indicated for weight management.)

How it works

Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. GLP-1, which regulates appetite and calorie intake, is found in several regions of the brain that are involved in regulating appetite. Patients taking liraglutide lose weight because of decreased calorie intake, not increased energy expenditure.

Liraglutide is endogenously metabolized without a specific organ as a major route of elimination.1

Dosage and administration

Liraglutide is administered using a prefilled, multi-dose pen that can be injected in the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm. Recommended dosage is 3 mg/d, administered any time of day. Initiate dosage at 0.6 mg/d the first week, then titrate by 0.6 mg a week—to reduce the likelihood of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms—until 3 mg/d is reached.

Discontinue liraglutide if a patient has not lost at least 4% of body weight after 16 weeks of treatment, because it is unlikely the patient will achieve and sustain weight loss.

Efficacy

Liraglutide was studied in 3 clinical trials of obese and overweight participants who had a weight-related condition. Patients who had a history of major depressive disorder or suicide attempt were excluded from the studies. All participants in Studies 1 and 2 received instruction about following a reduced-calorie diet and increasing physical activity. In Study 3, patients were randomized to treatment after losing >5% of their body weight through reduced calorie intake and exercise; those who did not meet the required weight loss were excluded from the study. In these 56-week clinical studies:

• of 3,731 participants without diabetes or a weight-related comorbidity, such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol, 62% of patients (n = 2,313) who took liraglutide lost ≥5% of their body weight from baseline, compared with 34% of participants who received placebo

• of 635 participants with T2DM, 49% of patients (n = 311) treated with liraglutide lost ≥5% of their body weight compared with 16% placebo patients

• of 422 participants with a weight-related comorbidity, 42% of patients (n = 177) lost ≥5% of their body weight compared with 21.7% of placebo patients.

Improvements in some cardiovascular disease risk factors were observed. Long-term follow up was not studied.

Contraindictations

Liraglutide is contraindicated in patients who have a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. In a 104-week study, malignant thyroid C-cell carcinomas were detected in rats and mice given liraglutide, 1 and 3 mg/kg/d; however, it was not detected in groups given 0.03 and 0.2 mg/kg/d. It isn’t known whether liraglutide can cause thyroid C-cell tumors in humans.

Patients should not take liraglutide if they have hypersensitivity to liraglutide or any product components, are using insulin, are taking any other GLP-1 receptor agonist, or are pregnant.

Adverse effects

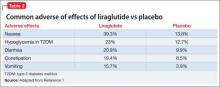

The most common reported adverse effects are nausea (39.3%), hypoglycemia in patients with T2DM (23%), diarrhea (20.9%), constipation (19.4%), and vomiting (15.7%) (Table 2). In clinical trials, 9.8% of patients discontinued treatment because of adverse effects, compared with 4.3% of those receiving placebo.

Liraglutide has low potential for pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions related to cytochrome P450 and plasma protein binding. For a full list of drug-drug interactions, see the full prescribing information.1

Reference

1. Saxenda [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk A/S; 2015.

Liraglutide (rDNA origin) injection, approved by the FDA in 2010 for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), has a new formulation and indication for treating obesity in adults as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity (Table 1).1

Liraglutide, recommended dosage 3 mg/d (under the brand name Saxenda), is approved for adults with a body mass index (BMI) ≥30, or those with a BMI of ≥27 and a weight-related condition such as hypertension, T2DM, or high cholesterol.1 (A 1.8-mg formulation, under the brand name Victoza, is FDA-approved for managing T2DM, but is not indicated for weight management.)

How it works

Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. GLP-1, which regulates appetite and calorie intake, is found in several regions of the brain that are involved in regulating appetite. Patients taking liraglutide lose weight because of decreased calorie intake, not increased energy expenditure.

Liraglutide is endogenously metabolized without a specific organ as a major route of elimination.1

Dosage and administration

Liraglutide is administered using a prefilled, multi-dose pen that can be injected in the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm. Recommended dosage is 3 mg/d, administered any time of day. Initiate dosage at 0.6 mg/d the first week, then titrate by 0.6 mg a week—to reduce the likelihood of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms—until 3 mg/d is reached.

Discontinue liraglutide if a patient has not lost at least 4% of body weight after 16 weeks of treatment, because it is unlikely the patient will achieve and sustain weight loss.

Efficacy

Liraglutide was studied in 3 clinical trials of obese and overweight participants who had a weight-related condition. Patients who had a history of major depressive disorder or suicide attempt were excluded from the studies. All participants in Studies 1 and 2 received instruction about following a reduced-calorie diet and increasing physical activity. In Study 3, patients were randomized to treatment after losing >5% of their body weight through reduced calorie intake and exercise; those who did not meet the required weight loss were excluded from the study. In these 56-week clinical studies:

• of 3,731 participants without diabetes or a weight-related comorbidity, such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol, 62% of patients (n = 2,313) who took liraglutide lost ≥5% of their body weight from baseline, compared with 34% of participants who received placebo

• of 635 participants with T2DM, 49% of patients (n = 311) treated with liraglutide lost ≥5% of their body weight compared with 16% placebo patients

• of 422 participants with a weight-related comorbidity, 42% of patients (n = 177) lost ≥5% of their body weight compared with 21.7% of placebo patients.

Improvements in some cardiovascular disease risk factors were observed. Long-term follow up was not studied.

Contraindictations

Liraglutide is contraindicated in patients who have a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. In a 104-week study, malignant thyroid C-cell carcinomas were detected in rats and mice given liraglutide, 1 and 3 mg/kg/d; however, it was not detected in groups given 0.03 and 0.2 mg/kg/d. It isn’t known whether liraglutide can cause thyroid C-cell tumors in humans.

Patients should not take liraglutide if they have hypersensitivity to liraglutide or any product components, are using insulin, are taking any other GLP-1 receptor agonist, or are pregnant.

Adverse effects

The most common reported adverse effects are nausea (39.3%), hypoglycemia in patients with T2DM (23%), diarrhea (20.9%), constipation (19.4%), and vomiting (15.7%) (Table 2). In clinical trials, 9.8% of patients discontinued treatment because of adverse effects, compared with 4.3% of those receiving placebo.

Liraglutide has low potential for pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions related to cytochrome P450 and plasma protein binding. For a full list of drug-drug interactions, see the full prescribing information.1

Liraglutide (rDNA origin) injection, approved by the FDA in 2010 for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), has a new formulation and indication for treating obesity in adults as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity (Table 1).1

Liraglutide, recommended dosage 3 mg/d (under the brand name Saxenda), is approved for adults with a body mass index (BMI) ≥30, or those with a BMI of ≥27 and a weight-related condition such as hypertension, T2DM, or high cholesterol.1 (A 1.8-mg formulation, under the brand name Victoza, is FDA-approved for managing T2DM, but is not indicated for weight management.)

How it works

Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. GLP-1, which regulates appetite and calorie intake, is found in several regions of the brain that are involved in regulating appetite. Patients taking liraglutide lose weight because of decreased calorie intake, not increased energy expenditure.

Liraglutide is endogenously metabolized without a specific organ as a major route of elimination.1

Dosage and administration

Liraglutide is administered using a prefilled, multi-dose pen that can be injected in the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm. Recommended dosage is 3 mg/d, administered any time of day. Initiate dosage at 0.6 mg/d the first week, then titrate by 0.6 mg a week—to reduce the likelihood of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms—until 3 mg/d is reached.

Discontinue liraglutide if a patient has not lost at least 4% of body weight after 16 weeks of treatment, because it is unlikely the patient will achieve and sustain weight loss.

Efficacy

Liraglutide was studied in 3 clinical trials of obese and overweight participants who had a weight-related condition. Patients who had a history of major depressive disorder or suicide attempt were excluded from the studies. All participants in Studies 1 and 2 received instruction about following a reduced-calorie diet and increasing physical activity. In Study 3, patients were randomized to treatment after losing >5% of their body weight through reduced calorie intake and exercise; those who did not meet the required weight loss were excluded from the study. In these 56-week clinical studies:

• of 3,731 participants without diabetes or a weight-related comorbidity, such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol, 62% of patients (n = 2,313) who took liraglutide lost ≥5% of their body weight from baseline, compared with 34% of participants who received placebo

• of 635 participants with T2DM, 49% of patients (n = 311) treated with liraglutide lost ≥5% of their body weight compared with 16% placebo patients

• of 422 participants with a weight-related comorbidity, 42% of patients (n = 177) lost ≥5% of their body weight compared with 21.7% of placebo patients.

Improvements in some cardiovascular disease risk factors were observed. Long-term follow up was not studied.

Contraindictations

Liraglutide is contraindicated in patients who have a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. In a 104-week study, malignant thyroid C-cell carcinomas were detected in rats and mice given liraglutide, 1 and 3 mg/kg/d; however, it was not detected in groups given 0.03 and 0.2 mg/kg/d. It isn’t known whether liraglutide can cause thyroid C-cell tumors in humans.

Patients should not take liraglutide if they have hypersensitivity to liraglutide or any product components, are using insulin, are taking any other GLP-1 receptor agonist, or are pregnant.

Adverse effects

The most common reported adverse effects are nausea (39.3%), hypoglycemia in patients with T2DM (23%), diarrhea (20.9%), constipation (19.4%), and vomiting (15.7%) (Table 2). In clinical trials, 9.8% of patients discontinued treatment because of adverse effects, compared with 4.3% of those receiving placebo.

Liraglutide has low potential for pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions related to cytochrome P450 and plasma protein binding. For a full list of drug-drug interactions, see the full prescribing information.1

Reference

1. Saxenda [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk A/S; 2015.

Reference

1. Saxenda [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk A/S; 2015.