User login

School-based asthma program improves asthma care coordination for children

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM AAAAI 2021

Nighttime asthma predicts poor outcomes in teens

Teens with persistent nocturnal asthma symptoms were significantly more likely than were those without nighttime asthma to report poor functional health independent of daytime asthma, based on data from 430 adolescents aged 12-16 years.

Approximately half of children with severe asthma experience at least one night of inadequate sleep per week, and lost sleep among young children with asthma has been associated with impaired physical function, school absence, and worsened mood. However, the effect of asthma-related sleep disruption on daily function in teenagers in particular has not been well studied, according to Anne Zhang of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and colleagues.

In a poster presented at the virtual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies (#542), the researchers reviewed baseline survey data from the School-Based Asthma Care for Teens (SB-ACT) study, a randomized, controlled trial conducted from 2014 to 2018 in Rochester, N.Y.

The average age of the respondents was 13.4 years, 56% were male, 56% were African American, 32% were Hispanic, and 84% had Medicaid insurance.

Persistent nocturnal asthma was defined as 2 or more nights of nighttime awakening in the past 14 days, and intermittent nocturnal asthma was defined as less than 2 nights of nighttime awakening in the past 14 days.

Overall, teens with persistent nocturnal asthma were significantly more likely than were those with intermittent nocturnal asthma to report physical limitations during strenuous activity (58% vs. 41%), moderate activity (32% vs. 19%), and school gym classes (36% vs. 19%; P <.01 for all).

In addition to physical impact, teens with persistent nocturnal asthma were more likely than were those with intermittent nocturnal asthma to report depressive symptoms (41% vs. 23%), asthma-related school absences in the past 14 days (0.81 vs. 0.12), and poorer quality of life (4.6 vs. 5.9, P <.01 for all).

The results remained significant in a multivariate analysis that controlled for daytime asthma symptoms, weight status, race, ethnicity, gender, age, and smoke exposure, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, potential of recall bias in survey responses, and lack of data on sleep duration and quality, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that improving nighttime asthma control for teens may improve daily function, and providers should ask teens with asthma about the possible effect and burden of nighttime symptoms, they said. Potential strategies to improve persistent nocturnal asthma symptoms include adjusting the timing of medications or physical activity, they added.

“We know that getting adequate, high-quality sleep is important for health - especially for adolescents,” said Kelly A. Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, in an interview. “Just like adults, tired teens are not able to function at their best and are at higher risk of developing mood problems,” she said.

However, “There are already so many barriers for teens getting good sleep, such as screen time/social media, homework, busy social calendars, caffeine use, and early morning school start times,” she said. Underlying medical conditions such as depression, anxiety, and obstructive sleep apnea also can contribute to poor sleep for teens, she added.

“In my practice, I frequently counsel about sleep hygiene because it is so essential and not commonly followed,” said Dr. Curran. “Nocturnal asthma is another contributor to poor sleep - not one that I have been regularly screening for - and something we can potentially intervene in to help improve health and quality of life,” she emphasized.

Dr. Curran said that she was not surprised by the study findings, given what is known about the importance of sleep. In clinical practice, “Teens who have asthma should be screened for nocturnal symptoms as these are linked to worsened quality of life, including limitations in activities, depressive symptoms, and asthma-related school absence,” she said.

However, additional research is needed to better understand whether improving nocturnal asthma symptoms can help improve quality of life and daily functioning in adolescents, she noted.

The SB-ACT was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Zhang was supported in part by the OME-CACHED for medical student research and an NIH grant. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This story was updated on May 5. 2021.

Teens with persistent nocturnal asthma symptoms were significantly more likely than were those without nighttime asthma to report poor functional health independent of daytime asthma, based on data from 430 adolescents aged 12-16 years.

Approximately half of children with severe asthma experience at least one night of inadequate sleep per week, and lost sleep among young children with asthma has been associated with impaired physical function, school absence, and worsened mood. However, the effect of asthma-related sleep disruption on daily function in teenagers in particular has not been well studied, according to Anne Zhang of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and colleagues.

In a poster presented at the virtual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies (#542), the researchers reviewed baseline survey data from the School-Based Asthma Care for Teens (SB-ACT) study, a randomized, controlled trial conducted from 2014 to 2018 in Rochester, N.Y.

The average age of the respondents was 13.4 years, 56% were male, 56% were African American, 32% were Hispanic, and 84% had Medicaid insurance.

Persistent nocturnal asthma was defined as 2 or more nights of nighttime awakening in the past 14 days, and intermittent nocturnal asthma was defined as less than 2 nights of nighttime awakening in the past 14 days.

Overall, teens with persistent nocturnal asthma were significantly more likely than were those with intermittent nocturnal asthma to report physical limitations during strenuous activity (58% vs. 41%), moderate activity (32% vs. 19%), and school gym classes (36% vs. 19%; P <.01 for all).

In addition to physical impact, teens with persistent nocturnal asthma were more likely than were those with intermittent nocturnal asthma to report depressive symptoms (41% vs. 23%), asthma-related school absences in the past 14 days (0.81 vs. 0.12), and poorer quality of life (4.6 vs. 5.9, P <.01 for all).

The results remained significant in a multivariate analysis that controlled for daytime asthma symptoms, weight status, race, ethnicity, gender, age, and smoke exposure, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, potential of recall bias in survey responses, and lack of data on sleep duration and quality, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that improving nighttime asthma control for teens may improve daily function, and providers should ask teens with asthma about the possible effect and burden of nighttime symptoms, they said. Potential strategies to improve persistent nocturnal asthma symptoms include adjusting the timing of medications or physical activity, they added.

“We know that getting adequate, high-quality sleep is important for health - especially for adolescents,” said Kelly A. Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, in an interview. “Just like adults, tired teens are not able to function at their best and are at higher risk of developing mood problems,” she said.

However, “There are already so many barriers for teens getting good sleep, such as screen time/social media, homework, busy social calendars, caffeine use, and early morning school start times,” she said. Underlying medical conditions such as depression, anxiety, and obstructive sleep apnea also can contribute to poor sleep for teens, she added.

“In my practice, I frequently counsel about sleep hygiene because it is so essential and not commonly followed,” said Dr. Curran. “Nocturnal asthma is another contributor to poor sleep - not one that I have been regularly screening for - and something we can potentially intervene in to help improve health and quality of life,” she emphasized.

Dr. Curran said that she was not surprised by the study findings, given what is known about the importance of sleep. In clinical practice, “Teens who have asthma should be screened for nocturnal symptoms as these are linked to worsened quality of life, including limitations in activities, depressive symptoms, and asthma-related school absence,” she said.

However, additional research is needed to better understand whether improving nocturnal asthma symptoms can help improve quality of life and daily functioning in adolescents, she noted.

The SB-ACT was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Zhang was supported in part by the OME-CACHED for medical student research and an NIH grant. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This story was updated on May 5. 2021.

Teens with persistent nocturnal asthma symptoms were significantly more likely than were those without nighttime asthma to report poor functional health independent of daytime asthma, based on data from 430 adolescents aged 12-16 years.

Approximately half of children with severe asthma experience at least one night of inadequate sleep per week, and lost sleep among young children with asthma has been associated with impaired physical function, school absence, and worsened mood. However, the effect of asthma-related sleep disruption on daily function in teenagers in particular has not been well studied, according to Anne Zhang of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and colleagues.

In a poster presented at the virtual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies (#542), the researchers reviewed baseline survey data from the School-Based Asthma Care for Teens (SB-ACT) study, a randomized, controlled trial conducted from 2014 to 2018 in Rochester, N.Y.

The average age of the respondents was 13.4 years, 56% were male, 56% were African American, 32% were Hispanic, and 84% had Medicaid insurance.

Persistent nocturnal asthma was defined as 2 or more nights of nighttime awakening in the past 14 days, and intermittent nocturnal asthma was defined as less than 2 nights of nighttime awakening in the past 14 days.

Overall, teens with persistent nocturnal asthma were significantly more likely than were those with intermittent nocturnal asthma to report physical limitations during strenuous activity (58% vs. 41%), moderate activity (32% vs. 19%), and school gym classes (36% vs. 19%; P <.01 for all).

In addition to physical impact, teens with persistent nocturnal asthma were more likely than were those with intermittent nocturnal asthma to report depressive symptoms (41% vs. 23%), asthma-related school absences in the past 14 days (0.81 vs. 0.12), and poorer quality of life (4.6 vs. 5.9, P <.01 for all).

The results remained significant in a multivariate analysis that controlled for daytime asthma symptoms, weight status, race, ethnicity, gender, age, and smoke exposure, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, potential of recall bias in survey responses, and lack of data on sleep duration and quality, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that improving nighttime asthma control for teens may improve daily function, and providers should ask teens with asthma about the possible effect and burden of nighttime symptoms, they said. Potential strategies to improve persistent nocturnal asthma symptoms include adjusting the timing of medications or physical activity, they added.

“We know that getting adequate, high-quality sleep is important for health - especially for adolescents,” said Kelly A. Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, in an interview. “Just like adults, tired teens are not able to function at their best and are at higher risk of developing mood problems,” she said.

However, “There are already so many barriers for teens getting good sleep, such as screen time/social media, homework, busy social calendars, caffeine use, and early morning school start times,” she said. Underlying medical conditions such as depression, anxiety, and obstructive sleep apnea also can contribute to poor sleep for teens, she added.

“In my practice, I frequently counsel about sleep hygiene because it is so essential and not commonly followed,” said Dr. Curran. “Nocturnal asthma is another contributor to poor sleep - not one that I have been regularly screening for - and something we can potentially intervene in to help improve health and quality of life,” she emphasized.

Dr. Curran said that she was not surprised by the study findings, given what is known about the importance of sleep. In clinical practice, “Teens who have asthma should be screened for nocturnal symptoms as these are linked to worsened quality of life, including limitations in activities, depressive symptoms, and asthma-related school absence,” she said.

However, additional research is needed to better understand whether improving nocturnal asthma symptoms can help improve quality of life and daily functioning in adolescents, she noted.

The SB-ACT was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Zhang was supported in part by the OME-CACHED for medical student research and an NIH grant. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This story was updated on May 5. 2021.

FROM PAS 2021

37-year-old man • cough • increasing shortness of breath • pleuritic chest pain • Dx?

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

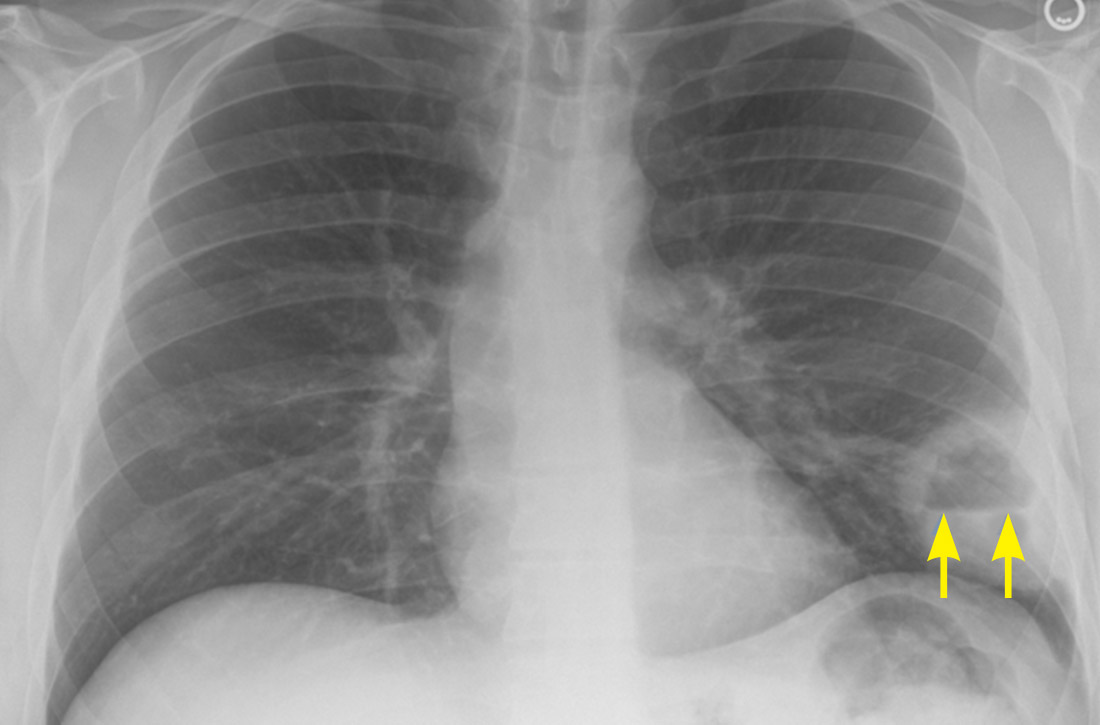

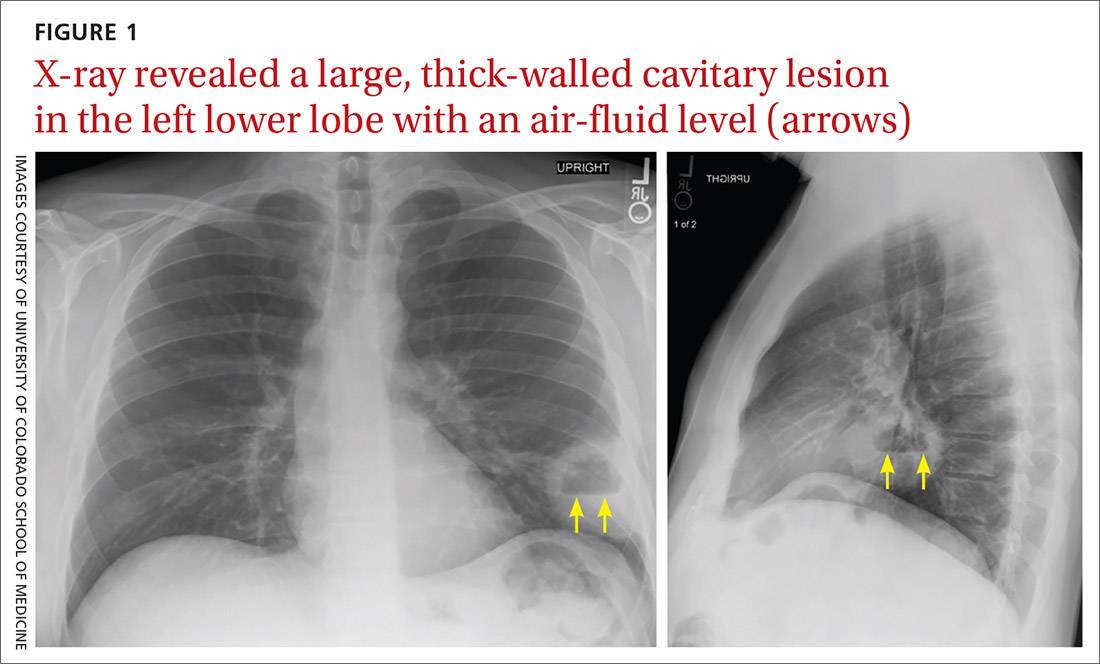

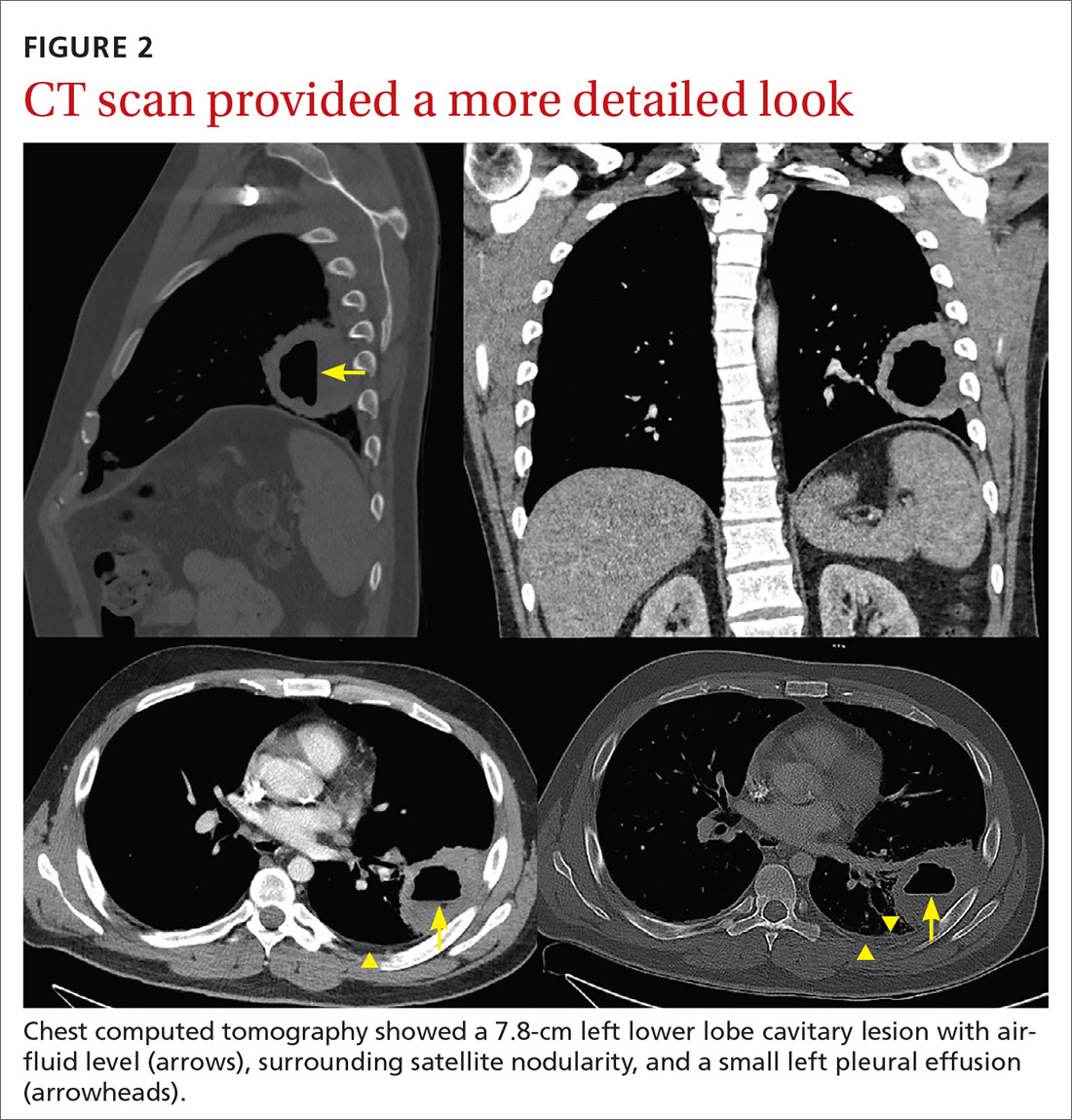

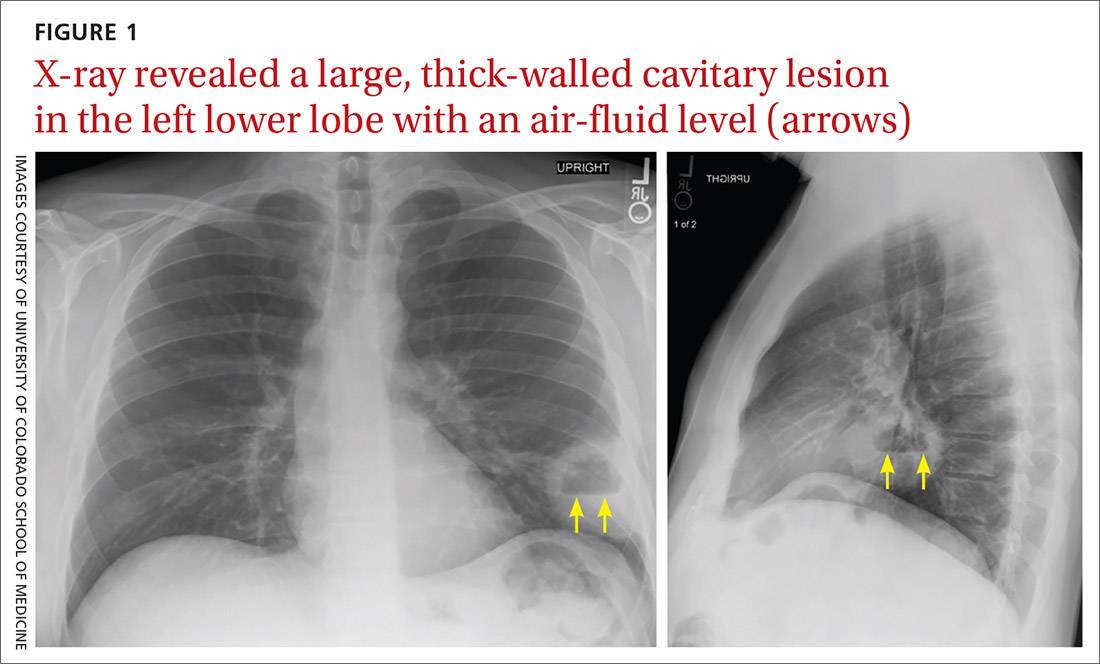

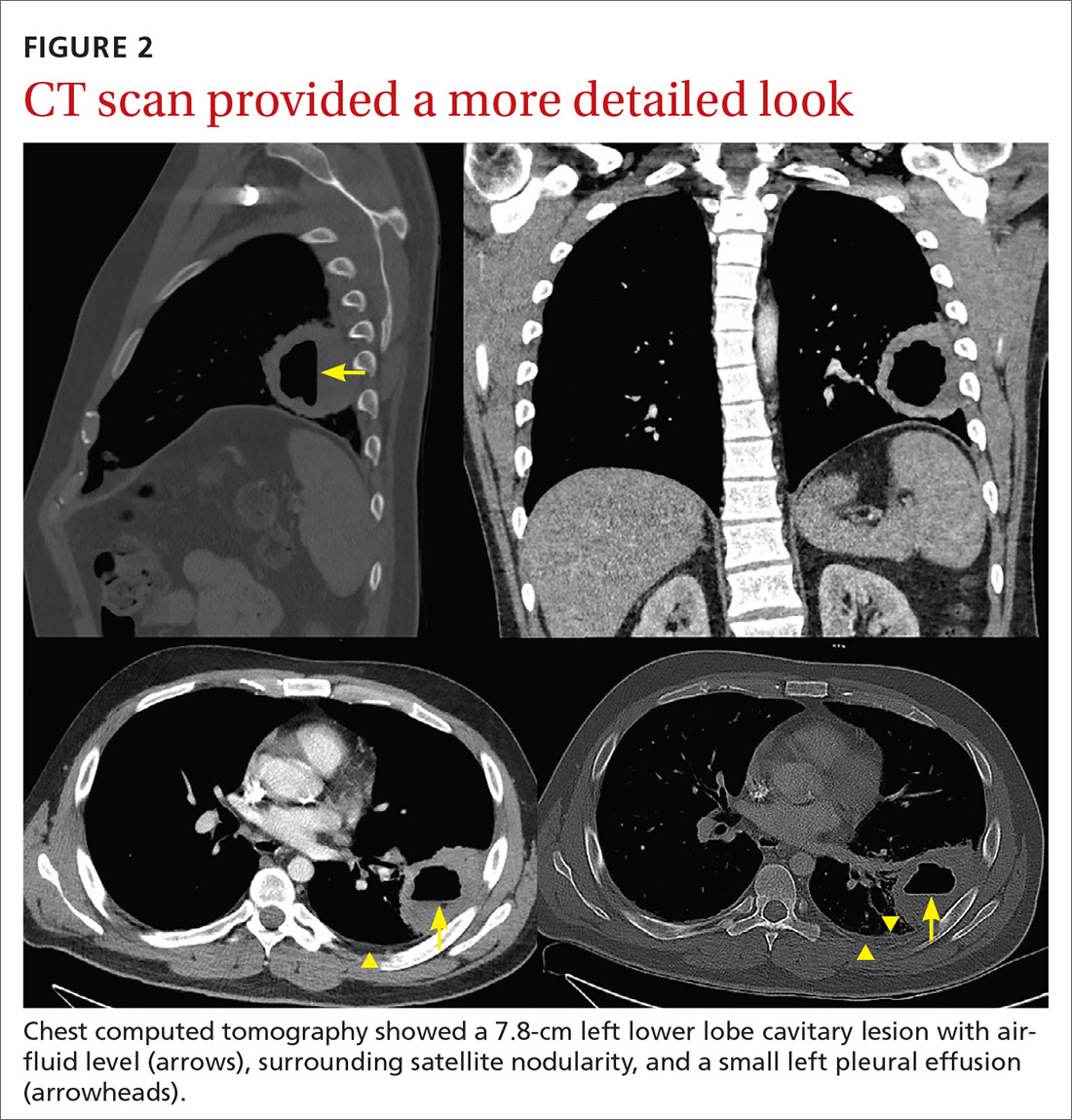

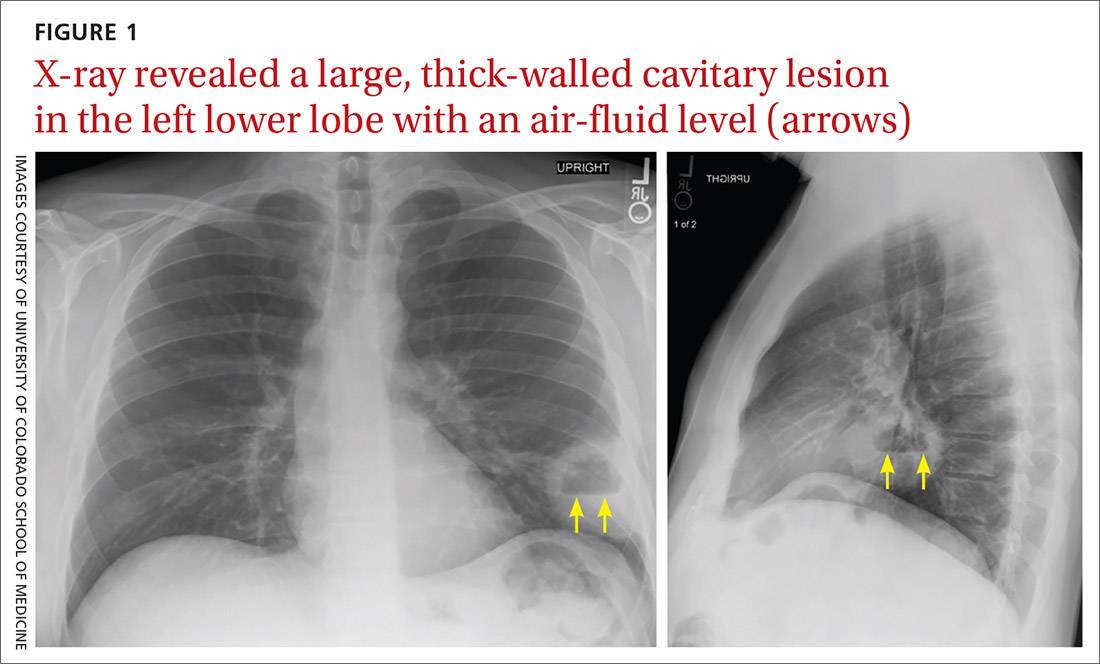

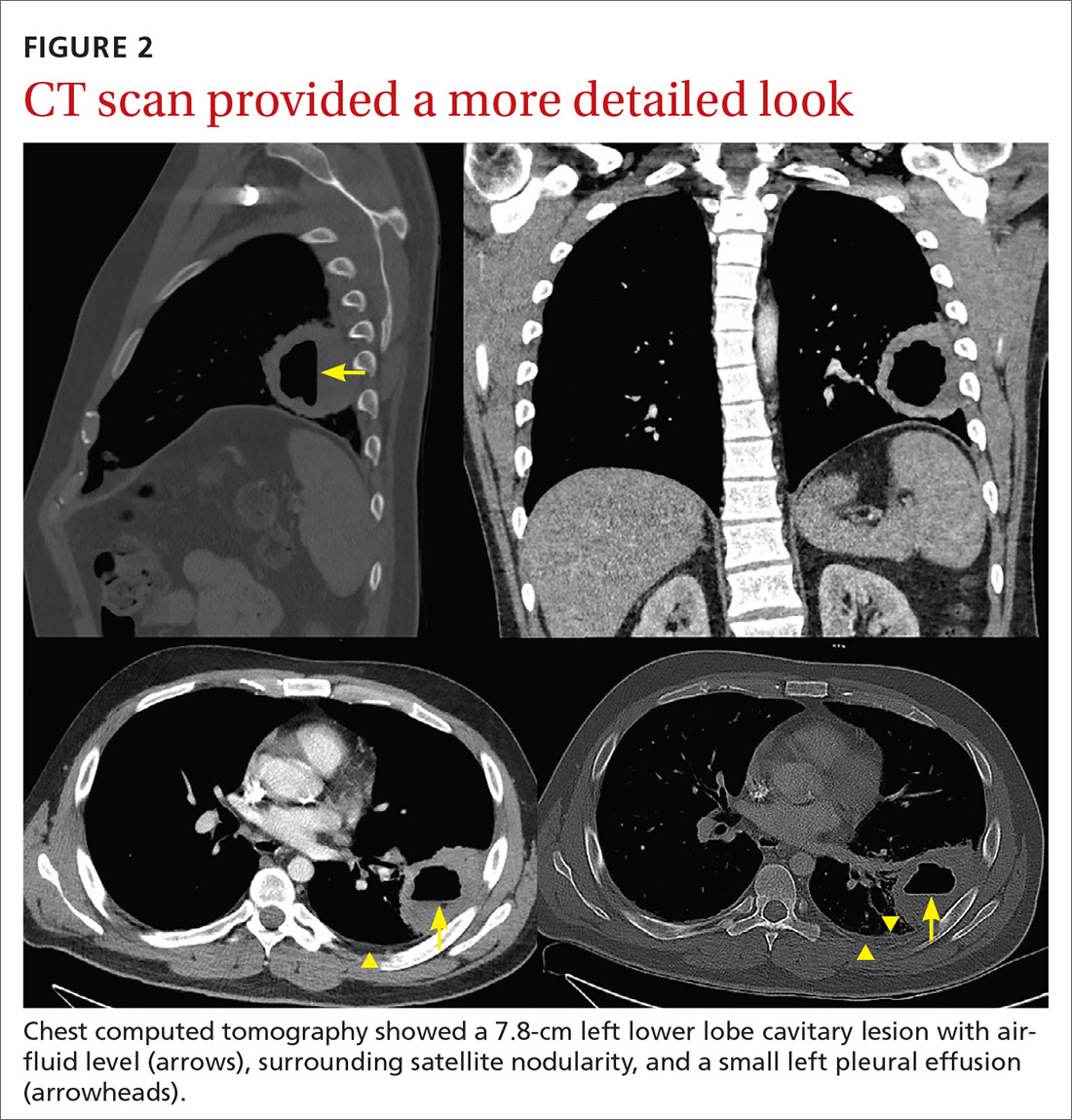

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

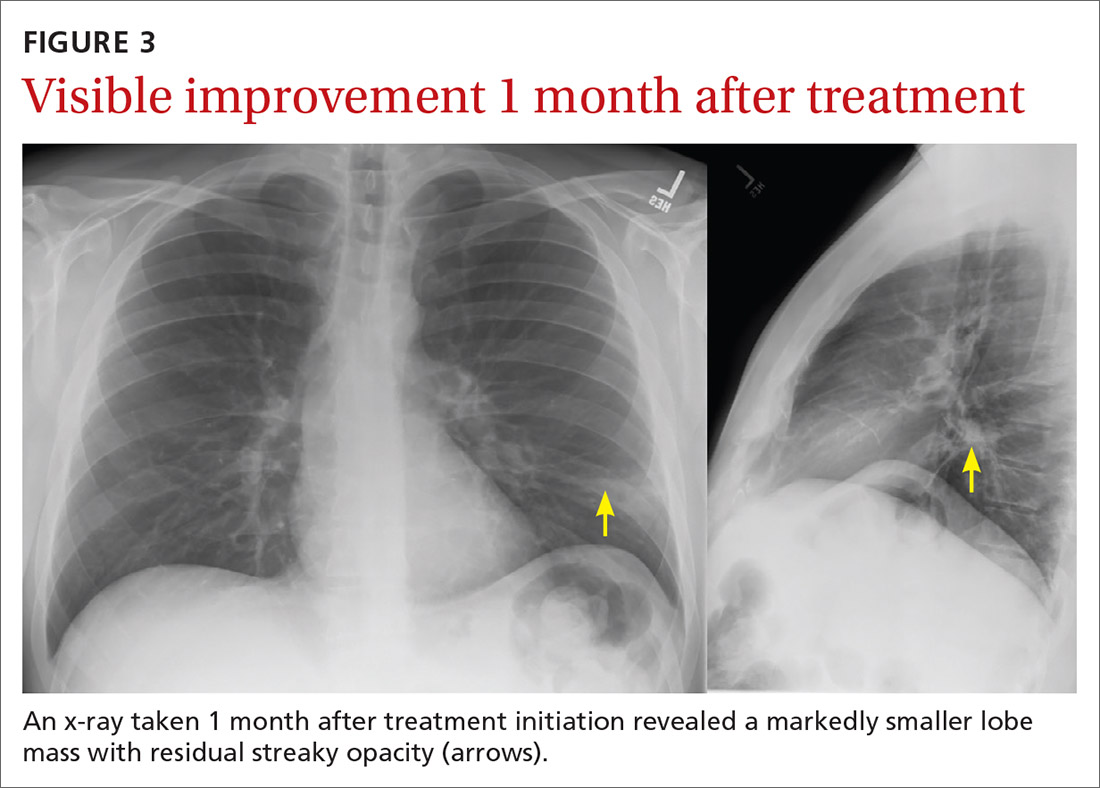

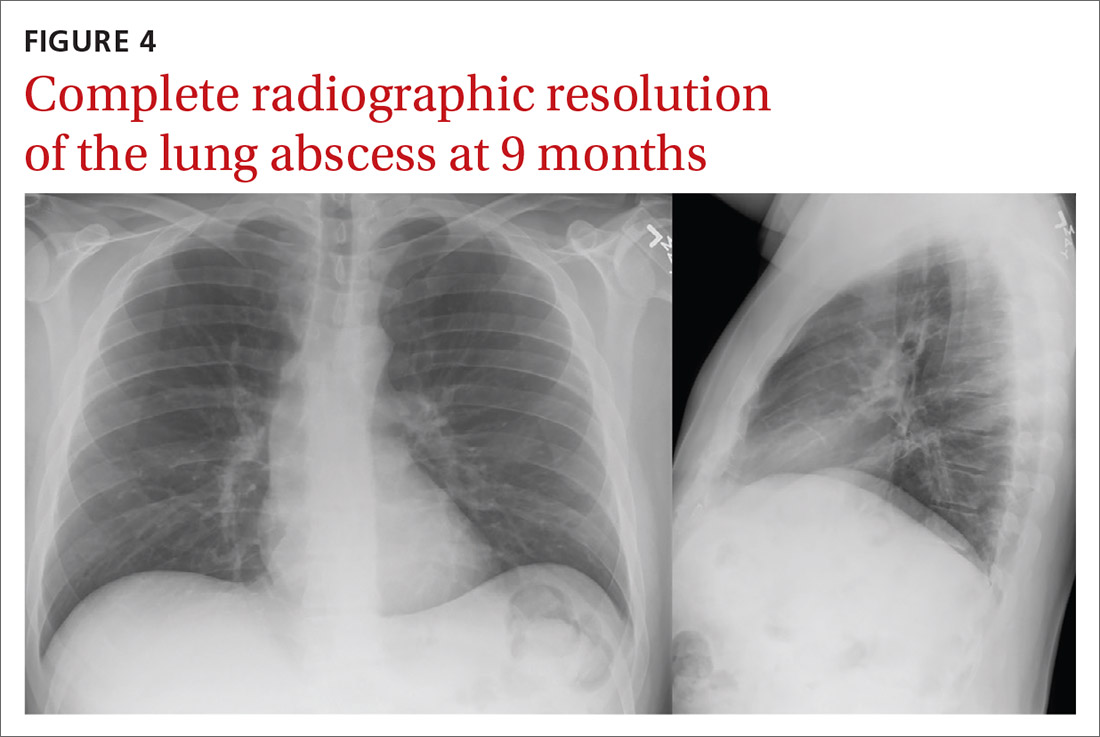

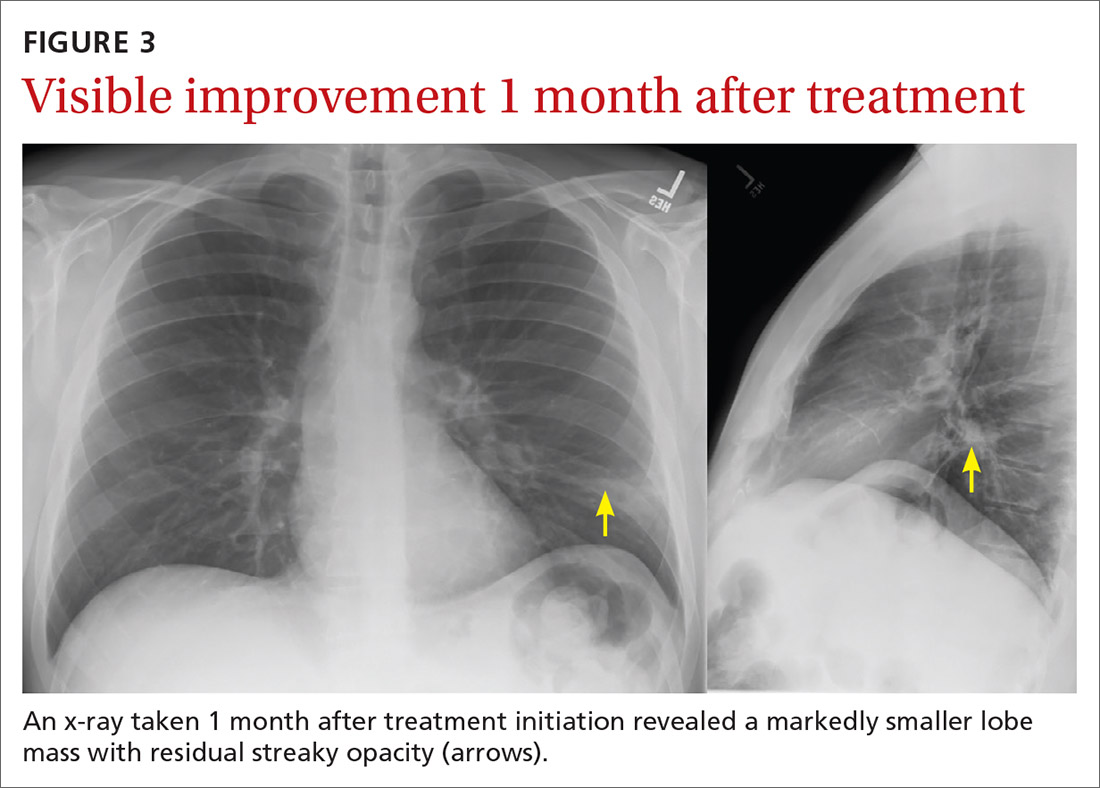

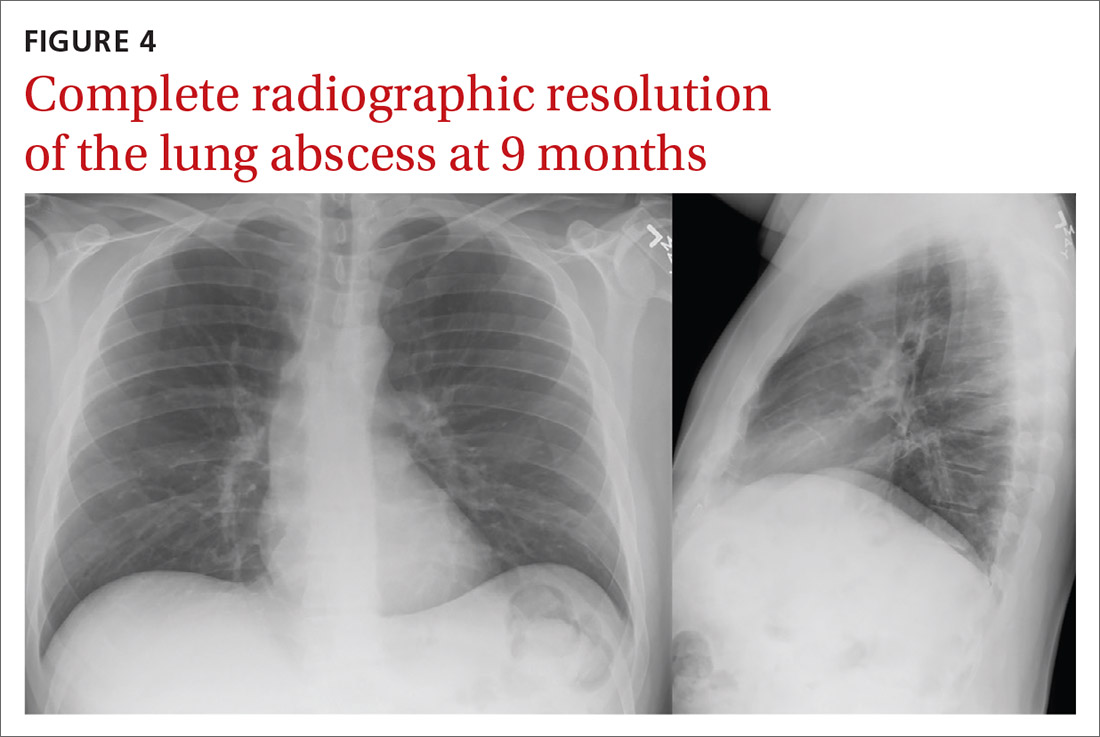

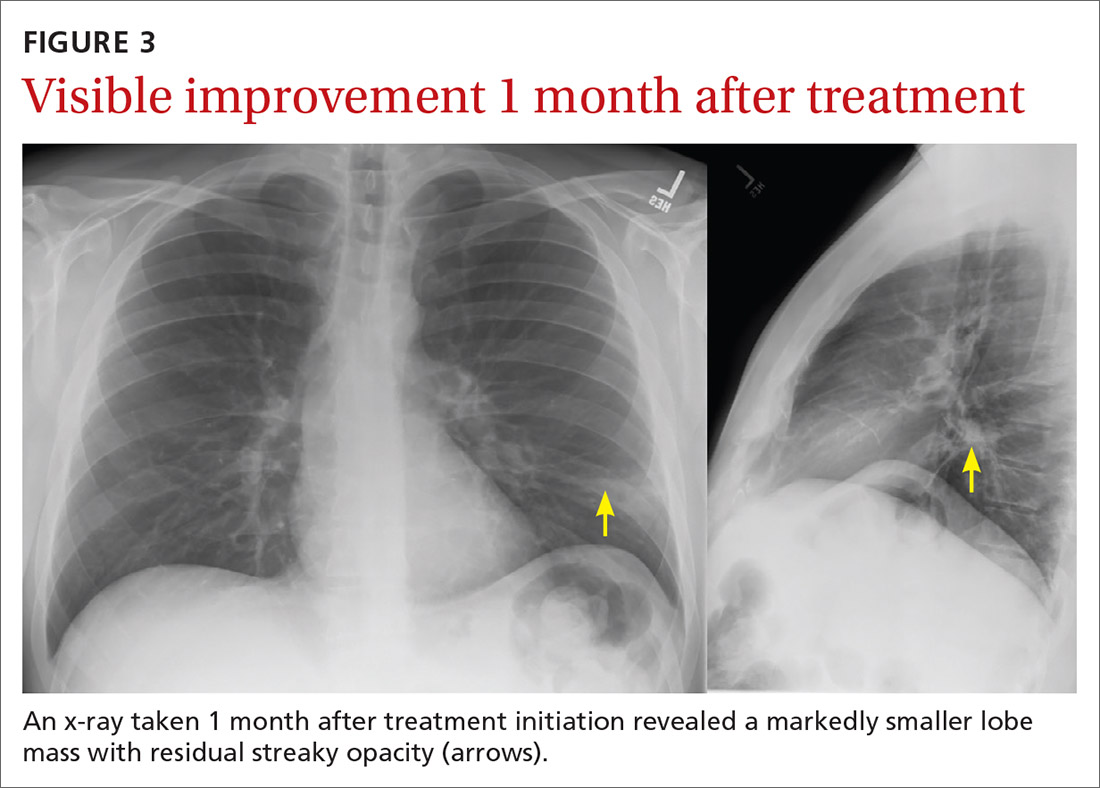

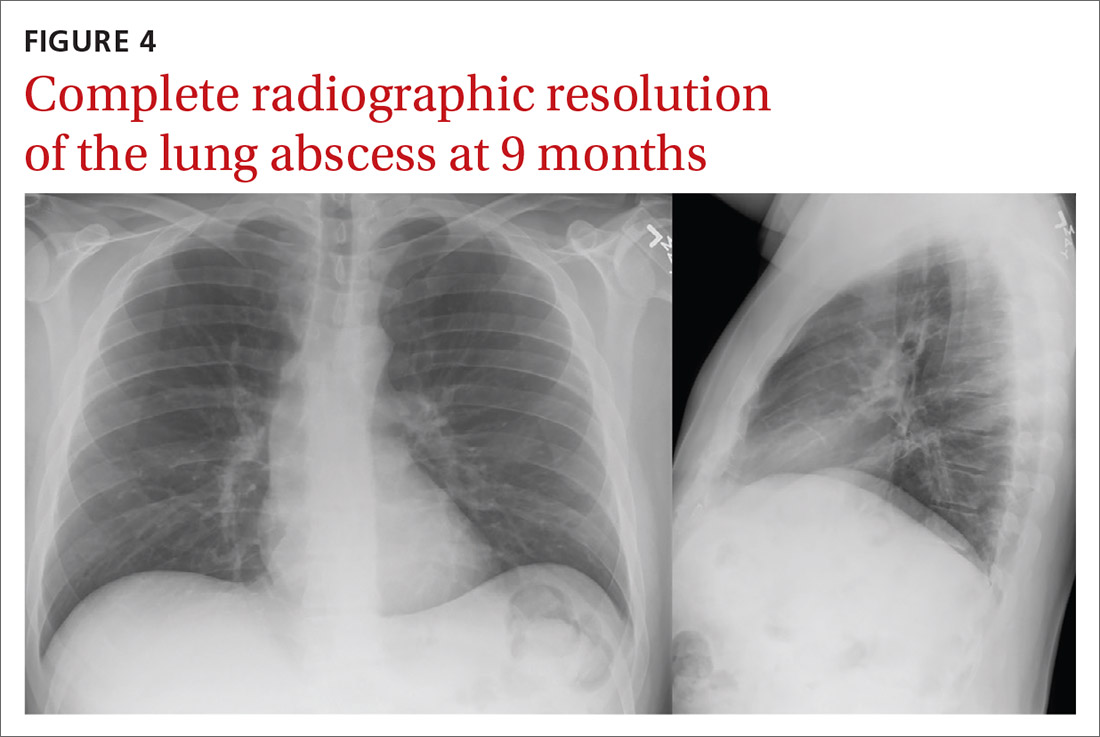

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

List of COVID-19 high-risk comorbidities expanded

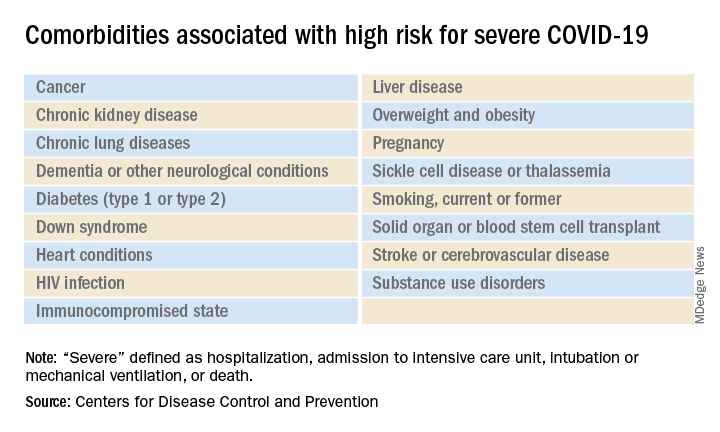

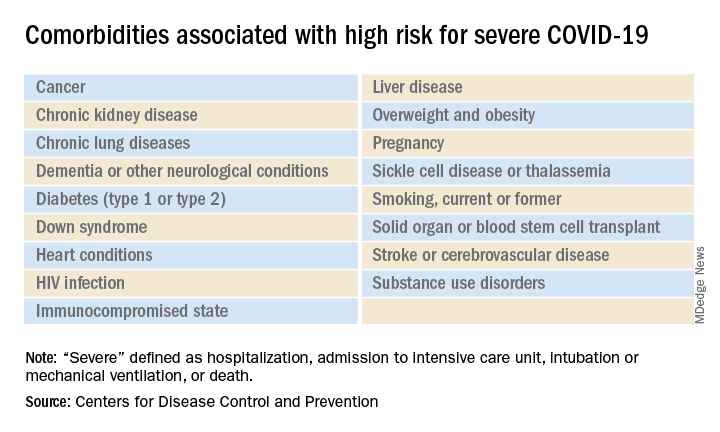

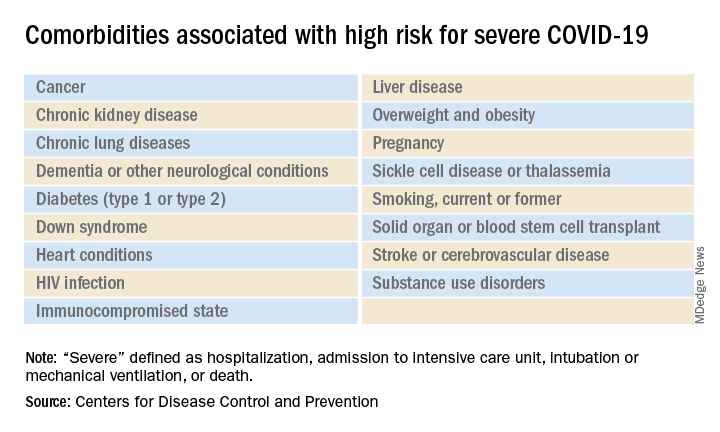

The list of medical according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s latest list consists of 17 conditions or groups of related conditions that may increase patients’ risk of developing severe outcomes of COVID-19, the CDC said on a web page intended for the general public.

On a separate page, the CDC defines severe outcomes “as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

Asthma is included in the newly expanded list with other chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis; the list’s heart disease entry covers coronary artery disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and hypertension, the CDC said.

The list of medical according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s latest list consists of 17 conditions or groups of related conditions that may increase patients’ risk of developing severe outcomes of COVID-19, the CDC said on a web page intended for the general public.

On a separate page, the CDC defines severe outcomes “as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

Asthma is included in the newly expanded list with other chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis; the list’s heart disease entry covers coronary artery disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and hypertension, the CDC said.

The list of medical according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s latest list consists of 17 conditions or groups of related conditions that may increase patients’ risk of developing severe outcomes of COVID-19, the CDC said on a web page intended for the general public.

On a separate page, the CDC defines severe outcomes “as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

Asthma is included in the newly expanded list with other chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis; the list’s heart disease entry covers coronary artery disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and hypertension, the CDC said.

Severe Asthma Highlights From AAAAI 2021

Key studies on severe asthma from the 2021 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) meeting include data on newer biologic treatments.

Dr Mario Castro, of the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City, discusses results from the pivotal NAVIGATOR trial. This 1-year study demonstrated that tezepelumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibitor of the activity of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), can provide clinically meaningful exacerbation reductions inpatients with severe asthma.

Dr Castro also discusses the phase 3 PONENTE study of benralizumab, a biologic therapy that targets the IL-5 pathway to reduce eosinophilic inflammation. He reviews data showing that benralizumab can significantly reduce the use of oral corticosteroids in patients with asthma, and considers the PONENTE trial results in light of data from the prior ZONDA phase 3 clinical trial.

--

Mario Castro, MD, MPH, Professor; Chief, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kansas.

Mario Castro, MD, MPH, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Genentech; Teva; Sanofi-Aventis; Novartis.

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Genentech; GlaxoSmithKline; Regeneron; Sanofi; Teva.

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Pulmatrix; Sanofi-Aventis; Shirogi.

Key studies on severe asthma from the 2021 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) meeting include data on newer biologic treatments.

Dr Mario Castro, of the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City, discusses results from the pivotal NAVIGATOR trial. This 1-year study demonstrated that tezepelumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibitor of the activity of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), can provide clinically meaningful exacerbation reductions inpatients with severe asthma.

Dr Castro also discusses the phase 3 PONENTE study of benralizumab, a biologic therapy that targets the IL-5 pathway to reduce eosinophilic inflammation. He reviews data showing that benralizumab can significantly reduce the use of oral corticosteroids in patients with asthma, and considers the PONENTE trial results in light of data from the prior ZONDA phase 3 clinical trial.

--

Mario Castro, MD, MPH, Professor; Chief, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kansas.

Mario Castro, MD, MPH, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Genentech; Teva; Sanofi-Aventis; Novartis.

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Genentech; GlaxoSmithKline; Regeneron; Sanofi; Teva.

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Pulmatrix; Sanofi-Aventis; Shirogi.

Key studies on severe asthma from the 2021 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) meeting include data on newer biologic treatments.

Dr Mario Castro, of the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City, discusses results from the pivotal NAVIGATOR trial. This 1-year study demonstrated that tezepelumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibitor of the activity of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), can provide clinically meaningful exacerbation reductions inpatients with severe asthma.

Dr Castro also discusses the phase 3 PONENTE study of benralizumab, a biologic therapy that targets the IL-5 pathway to reduce eosinophilic inflammation. He reviews data showing that benralizumab can significantly reduce the use of oral corticosteroids in patients with asthma, and considers the PONENTE trial results in light of data from the prior ZONDA phase 3 clinical trial.

--

Mario Castro, MD, MPH, Professor; Chief, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kansas.

Mario Castro, MD, MPH, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Genentech; Teva; Sanofi-Aventis; Novartis.

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Genentech; GlaxoSmithKline; Regeneron; Sanofi; Teva.

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; GlaxoSmithKline; Pulmatrix; Sanofi-Aventis; Shirogi.

Managing Moderate to Severe Asthma in Adolescents

"The eye of the hurricane" is how adolescent asthma is often described, according to Dr Benjamin Gaston, of Indiana University School of Medicine, given the disease is more prevalent in children but more severe in patients whose asthma continues on into adulthood.

In adolescence, increasingly severe disease may find itself on a collision course with nonadherence, which remains a challenge at this age. Because adolescents adapt easily to telemedicine and mobile apps, pandemic-related disruptions to in-person appointments may not be a barrier for this group and indeed may be beneficial.

The 2019 GINA and 2020 NHLBI guidelines offer promising new approaches, including use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with formoterol at the onset of symptoms. ICS with formoterol as rescue and long-acting monoclonal antibody injections have proven effective for some adolescents but are no substitute for daily prevention therapy, an important standard of care.

Obstacles remain, including the high cost of both ICS-formoterol and the new biologics, as well as the inconvenient packaging of formoterol, which is not included in most ICS-LABA combinations on the market.

Studies such as the NHLBI PrecISE trial are investigating predictive biomarkers that could lead to highly individualized treatments for adolescent patients with this heterogeneous disease.

--

Benjamin Gaston, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine; Vice Chair for Translational Research, Department of Pediatrics, Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Benjamin Gaston, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

"The eye of the hurricane" is how adolescent asthma is often described, according to Dr Benjamin Gaston, of Indiana University School of Medicine, given the disease is more prevalent in children but more severe in patients whose asthma continues on into adulthood.

In adolescence, increasingly severe disease may find itself on a collision course with nonadherence, which remains a challenge at this age. Because adolescents adapt easily to telemedicine and mobile apps, pandemic-related disruptions to in-person appointments may not be a barrier for this group and indeed may be beneficial.

The 2019 GINA and 2020 NHLBI guidelines offer promising new approaches, including use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with formoterol at the onset of symptoms. ICS with formoterol as rescue and long-acting monoclonal antibody injections have proven effective for some adolescents but are no substitute for daily prevention therapy, an important standard of care.

Obstacles remain, including the high cost of both ICS-formoterol and the new biologics, as well as the inconvenient packaging of formoterol, which is not included in most ICS-LABA combinations on the market.

Studies such as the NHLBI PrecISE trial are investigating predictive biomarkers that could lead to highly individualized treatments for adolescent patients with this heterogeneous disease.

--

Benjamin Gaston, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine; Vice Chair for Translational Research, Department of Pediatrics, Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Benjamin Gaston, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

"The eye of the hurricane" is how adolescent asthma is often described, according to Dr Benjamin Gaston, of Indiana University School of Medicine, given the disease is more prevalent in children but more severe in patients whose asthma continues on into adulthood.

In adolescence, increasingly severe disease may find itself on a collision course with nonadherence, which remains a challenge at this age. Because adolescents adapt easily to telemedicine and mobile apps, pandemic-related disruptions to in-person appointments may not be a barrier for this group and indeed may be beneficial.

The 2019 GINA and 2020 NHLBI guidelines offer promising new approaches, including use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with formoterol at the onset of symptoms. ICS with formoterol as rescue and long-acting monoclonal antibody injections have proven effective for some adolescents but are no substitute for daily prevention therapy, an important standard of care.

Obstacles remain, including the high cost of both ICS-formoterol and the new biologics, as well as the inconvenient packaging of formoterol, which is not included in most ICS-LABA combinations on the market.

Studies such as the NHLBI PrecISE trial are investigating predictive biomarkers that could lead to highly individualized treatments for adolescent patients with this heterogeneous disease.

--

Benjamin Gaston, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine; Vice Chair for Translational Research, Department of Pediatrics, Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Benjamin Gaston, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Asthma-COPD overlap linked to occupational pollutants

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.