User login

Depression, or something else?

CASE Suicidal behavior, severe headaches

Ms. A, age 60, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depression, suicidal behavior, and 3 days of severe headaches. Neurology is consulted and an MRI is ordered, which shows a 3.0-cm mass lesion in the left temporal lobe with associated vasogenic edema that is suspicious for metastatic disease (Figure).

Ms. A is admitted to the hospital for further workup of her brain lesion. She is started on IV dexamethasone, 10 mg every 6 hours, a glucocorticosteroid, for brain edema, and levetiracetam, 500 mg twice a day, for seizure prophylaxis.

Upon admission, in addition to oncology and neurosurgery, psychiatry is also consulted to evaluate Ms. A for depression and suicidality.

EVALUATION Mood changes and poor judgment

Ms. A has a psychiatric history of depression and alcohol use disorder but says she has not consumed any alcohol in years. Her medical history includes hypertension, diabetes, and stage 4 non-small–cell lung cancer, for which she received surgery and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy 1 year ago.

On initial intake, Ms. A reports that in addition to the headaches, she has also been experiencing worsening depression and suicidal behavior. For the past 2 months, she has had a severely depressed mood, with notable anhedonia, poor appetite, insomnia, low energy, and decreased concentration. The changes in her mental health were triggered by her mother’s death. Three days prior to admission, the patient planned to overdose on antihypertensive pills, but her suicide attempt was interrupted when her family called. She denies any current suicidal ideation, intent, or plan.

According to her family, Ms. A has been increasingly irritable and her personality has changed in the past month. She also has been repeatedly sorting through her neighbors’ garbage.

Ms. A’s current psychiatric medications are duloxetine, 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 50 mg every night at bedtime; and buspirone, 10 mg/d. However, it is unclear if she is consistently taking these medications.

Continue to: On mental status examination...

On mental status examination, Ms. A is calm and she has no abnormal movements. She says she is depressed. Her affect is reactive and labile. She is alert and oriented to person, place, and time. Her attention, registration, and recall are intact. Her executive function is not tested. However, Ms. A’s insight and judgment seem poor.

To address Ms. A’s worsening depression, the psychiatry team increases her duloxetine from 30 to 60 mg/d, and she continues quetiapine, 50 mg every night at bedtime, for mood lability. Buspirone is not continued because she was not taking a therapeutic dosage in the community.

Within 4 days, Ms. A shows improvement in sleep, appetite, and mood. She has no further suicidal ideation.

[polldaddy:10511743]

The authors’ observations

Ms. A had a recurrence of what was presumed to be major depressive disorder (MDD) in the context of her mother’s death. However, she also exhibited irritability, mood lability, and impulsivity, all of which could be part of her depression, or a separate problem related to her brain tumor. Because Ms. A had never displayed bizarre behavior before the past few weeks, it is likely that her CNS lesion was directly affecting her personality and possibly underlying her planned suicide attempt.

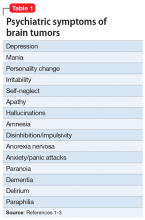

Fifty to 80% of patients with CNS tumors, either primary or metastatic, present with psychiatric symptoms.1 Table 11-3 lists common psychiatric symptoms of brain tumors. Unfortunately, there is little reliable evidence that directly correlates tumor location with specific psychiatric symptoms. A 2010 meta-analysis found a statistically significant link between anorexia nervosa and hypothalamic tumors.1 However, for other brain regions, there is only an increased likelihood that any given tumor location will produce psychiatric symptoms.1,4 For instance, compared to patients with tumors in other locations, those with temporal lobe tumors are more likely to present with mood disorders, personality changes, and memory problems.1 In contrast, patients with frontal lobe tumors have an increased likelihood of psychosis, mood disorders, and personality changes.1 Patients with tumors in the pituitary region often present with anxiety.1

Continue to: When considering treatment options...

When considering treatment options for Ms. A, alcohol withdrawal was unlikely given the remote history of alcohol use, low alcohol blood level, and lack of evidence of unstable vital signs or tremor. Although she might have benefited from inpatient psychiatric treatment, this needed to wait until there was a definitive treatment plan for her brain tumor. Finally, although a paraneoplastic syndrome, such as limbic encephalitis, could be causing her psychiatric symptoms, this scenario is less likely with non-small–cell lung cancer.

Although uncommon, CNS tumors can present with psychiatric symptoms as the only manifestation. This is more likely when a patient exhibits new-onset or atypical symptoms, or fails to respond to standard psychiatric treatment.4 Case reports have described patients with brain tumors being misdiagnosed as having a primary psychiatric condition, which delays treatment of their CNS cancer.2 Additionally, frontal and limbic tumors are more likely to present with psychiatric manifestations; up to 90% of patients exhibit altered mental status or personality changes, as did Ms. A.1,4 Clearly, it is easier to identify patients with psychiatric symptoms resulting from a brain tumor when they also present with focal neurologic deficits or systemic symptoms, such as headache or nausea and vomiting. Ms. A presented with severe headaches, which is what led to her early imaging and prompt diagnosis.

Numerous proposed mechanisms might account for the psychiatric symptoms that occur during the course of a brain tumor, including direct injury to neuronal cells, secretion of hormones or other tumor-derived substances, and peri-ictal phenomena.3

TREATMENT Tumor is removed, but memory is impaired

Ms. A is scheduled for craniotomy and surgical resection of the frontal mass. Prior to surgery, Ms. A shows interest in improving her health, cooperates with staff, and seeks her daughter’s input on treatment. One week after admission, Ms. A has her mass resected, which is confirmed on biopsy to be a lung metastasis. Post-surgery, Ms. A receives codeine, 30 mg every 6 hours as needed, for pain; she continues dexamethasone, 4 mg IV every 6 hours, for brain edema and levetiracetam, 500 mg twice a day, for seizure prophylaxis.

On Day 2 after surgery, Ms. A attempts to elope. When she is approached by a psychiatrist on the treatment team, she does not recognize him. Although her long-term memory seems intact, she is unable to remember the details of recent events, including her medical and surgical treatments.

[polldaddy:10511745]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Ms. A’s memory impairment may be secondary to a surgically acquired neurocognitive deficit. In the United States, brain metastases represent a significant public health issue, affecting >100,000 patients per year.5 Metastatic lesions are the most common brain tumors. Lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma are the leading solid tumors to spread to the CNS.5 In cases of single brain metastasis, similar to Ms. A’s solitary left temporal lobe lesion, surgical resection plays a critical role in treatment. It provides histological confirmation of metastatic disease and can relieve mass effect if present. Studies have shown that combined surgical resection with radiation improves survival relative to patients who undergo radiation therapy alone.6,7

However, the benefits of surgical resection need to be balanced with preservation of neurologic function. Emerging evidence suggests that a majority of patients have surgically-acquired cognitive deficits due to damage of normal surrounding tissues, and these deficits are associated with reduced quality of life.8,9 Further, a study examining glioma surgical resections found that patients with left temporal lobe tumors exhibit more frequent and severe neurocognitive decline than patients with right temporal lobe tumors, especially in domains such as verbal memory.8 Ms. A’s memory impairment was persistent during her postoperative course, which suggests that it was not just an immediate post-surgical phenomenon, but a longer-lasting cognitive change directly related to the resection.

It is also possible that Ms. A had a prior neurocognitive disorder that manifested to a greater degree as a result of the CNS tumor. Ms. A might have had early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, although her intact memory before surgery makes this less likely. Alternatively, she could have had vascular dementia, especially given her long-standing hypertension and diabetes. This might have been missed in the initial evaluation because executive function was not tested. However, the relatively abrupt onset of memory problems after surgery suggests that she had no underlying neurocognitive disorder.

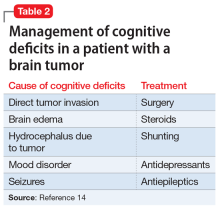

Ms. A’s presumed episode of MDD might also explain her memory changes. Major depressive disorder is increasingly common among geriatric patients, affecting approximately 5% of community-dwelling older adults.10 Its incidence increases with medical comorbidities, as suggested by depression rates of 5% to 10% in the primary care setting vs 37% in patients after critical-care hospitalizations.10 Late-life depression (LLD) occurs in adults age ≥60. Unlike depression in younger patients, LLD is more likely to be associated with cognitive impairment, specifically impairment of executive function and memory.11 The incidence of cognitive impairment in LLD is higher in patients with a history of depression, such as Ms. A.11,12 However, in general, patients who are depressed have memory complaints out of proportion to the clinical findings, and they show poor effort on cognitive testing. Ms. A exhibited neither of these, which makes it less likely that LLD was the exclusive cause of her memory loss.13 Table 214 outlines the management of cognitive deficits in a patient with a brain tumor.

EVALUATION Increasingly agitated and paranoid

After the tumor resection, Ms. A becomes increasingly irritable, uncooperative, and agitated. She repeatedly demands to be discharged. She insists she is fine and refuses medications and further laboratory workup. She becomes paranoid about the nursing staff and believes they are trying to kill her.

Continue to: On psychiatric re-evaluation...

On psychiatric re-evaluation, Ms. A demonstrates pressured speech, perseveration about going home, paranoid delusions, and anger at her family and physicians.

[polldaddy:10511747]

The authors’ observations

Ms. A’s refusal of medications and agitation may be explained by postoperative delirium, a surgical complication that is increasingly common among geriatric patients and is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Delirium is characterized by an acute onset and fluctuating course of symptoms that include inattention, motoric hypo- or hyperactivity, inappropriate behavior, emotional lability, cognitive dysfunction, and psychotic symptoms.15 Risk factors that contribute to postoperative delirium include older age, alcohol use, and poor baseline functional and cognitive status.16 The pathophysiology of delirium is not fully understood, but accumulating evidence suggests that different sets of interacting biologic factors (ie, neurotransmitters and inflammation) contribute to a disruption of large-scale neuronal networks in the brain, resulting in cognitive dysfunction.15 Patients who develop postoperative delirium are more likely to develop long-term cognitive dysfunction and have an increased risk of dementia.16

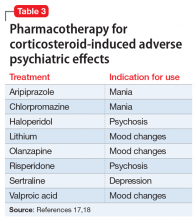

Another potential source of Ms. A’s agitation is steroid use. Ms. A received IV dexamethasone, 8 to 16 mg/d, around the time of her surgery. Steroids are commonly used to treat brain tumors, particularly when there is vasogenic edema. Steroid psychosis is a term loosely used to describe a wide range of psychiatric symptoms induced by corticosteroids that includes, but is not limited to, depression, mania, psychosis, delirium, and cognitive impairment.17 Steroid-induced psychiatric adverse effects occur in 5% to 18% of patients receiving corticosteroids and often happen early in treatment, although they can occur at any point.18 Corticosteroids influence brain activity via glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. These receptors are widely distributed throughout the brain and affect neurotransmitter systems, such as the serotonergic system, that are associated with changes in mood, behavior, and cognition.17 While the adverse psychiatric manifestations of steroid use vary, higher dosages are associated with an increased risk of psychiatric complications; mania is more prevalent early in the course of treatment, and depression is more common with long-term use.17,19 Table 317,18 outlines the evidence-based treatment of corticosteroid-induced adverse psychiatric effects.

Although there are no clinical guidelines or FDA-approved medications for treating steroid-induced psychiatric adverse events, these are best managed by tapering and discontinuing steroids when possible and simultaneously using psychotropic medications to treat psychiatric symptoms. Case reports and limited evidence-based literature have demonstrated that steroid-induced mania responds to mood stabilizers or antipsychotics, while depression can be managed with antidepressants or lithium.17

Additionally, patients with CNS tumors are at risk for seizures and often are prescribed antiepileptics. Because it is easy to administer and does not need to be titrated, levetiracetam is a commonly used agent. However, levetiracetam can cause psychiatric adverse effects, including behavior changes and frank psychosis.20

Continue to: Finally, Ms. A's altered mental status...

Finally, Ms. A’s altered mental status could have been related to opioid intoxication. Opioids are used to manage postsurgical pain, and studies have shown these medications can be a precipitating factor for delirium in geriatric patients.21

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

At the request of the psychiatry team, levetiracetam is discontinued due to its potential for psychiatric adverse effects. The neurosurgery team replaces it with valproic acid, 500 mg every 12 hours. Ms. A is also tapered off steroids fairly rapidly because of the potential for steroid-induced psychiatric adverse effects. Her quetiapine is titrated from 50 to 150 mg every night at bedtime, and duloxetine is discontinued.

OUTCOME Agitation improves dramatically

Ms. A’s new medication regimen dramatically improves her agitation, which allows Ms. A, her family, and the medical team to work together to establish treatment goals. Ms. A ultimately returns home with the assistance of her family. She continues to have memory issues, but with improved emotion regulation. Several months later, Ms. A is readmitted to the hospital because her cancer has progressed despite treatment.

Bottom Line

Brain tumors may present with various psychiatric manifestations that can change during the course of the patient’s treatment. A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation should parse out the interplay between direct effects of the tumor and any adverse effects that are the result of medical and/or surgical interventions to determine the cause of psychiatric symptoms and their appropriate management.

Related Resource

Madhusoodanan S, Ting MB, Farah T, et al. Psychiatric aspects of brain tumors: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(3):273-285.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buspirone • Buspar

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Codeine • Codeine systemic

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Haloperidol • Haldol

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Lorazepam • Ativan

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

1. Madhusoodanan S, Opler MG, Moise D, et al. Brain tumor location and psychiatric symptoms: is there any association? A meta-analysis of published case studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(10):1529-1536.

2. Bunevicius A, Deltuva VP, Deltuviene D, et al. Brain lesions manifesting as psychiatric disorders: eight cases. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):950-958.

3. Pearl ML, Talgat G, Valea FA, et al. Psychiatric symptoms due to brain metastases. Med Update Psychiatr. 1998;3(4):91-94.

4. Madhusoodanan S, Danan D, Moise D. Psychiatric manifestations of brain tumors: diagnostic implications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(4):343-349.

5. Ferguson SD, Wagner KM, Prabhu SS, et al. Neurosurgical management of brain metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2017;34(6-7):377-389.

6. Husain ZA, Regine WF, Kwok Y, et al. Brain metastases: contemporary management and future directions. Eur J Clin Med Oncol. 2011;3(3):38-45.

7. Vecht CJ, Haaxmareiche H, Noordijk EM, et al. Treatment of single brain metastasis - radiotherapy alone or combined with neurosurgery. Ann Neurol. 1993;33(6):583-590.

8. Barry RL, Byun NE, Tantawy MN, et al. In vivo neuroimaging and behavioral correlates in a rat model of chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(1):87-95.

9. Wu AS, Witgert ME, Lang FF, et al. Neurocognitive function before and after surgery for insular gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(6):1115-1125.

10. Taylor WD. Depression in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1228-1236.

11. Liguori C, Pierantozzi M, Chiaravalloti A, et al. When cognitive decline and depression coexist in the elderly: CSF biomarkers analysis can differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from late-life depression. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:38.

12. Luijendijk HJ, van den Berg JF, Dekker MJHJ, et al. Incidence and recurrence of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1394-1401.

13. Potter GG, Steffens DC. Contribution of depression to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults. Neurologist. 2007;13(3):105-117.

14. Taphoorn MJB, Klein M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(3):159-168.

15. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

16. Sprung J, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, et al. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients is associated with subsequent cognitive impairment. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(2):316-323.

17. Kusljic S, Manias E, Gogos A. Corticosteroid-induced psychiatric disturbances: it is time for pharmacists to take notice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(2):355-360.

18. Cerullo MA. Corticosteroid-induced mania: prepare for the unpredictable. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(6):43-50.

19. Dubovsky AN, Arvikar S, Stern TA, et al. Steroid psychosis revisited. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):103-115.

20. Habets JGV, Leentjens AFG, Schijns OEMG. Serious and reversible levetiracetam-induced psychiatric symptoms after resection of frontal low-grade glioma: two case histories. Br J Neurosurg. 2017;31(4):471-473.

21

CASE Suicidal behavior, severe headaches

Ms. A, age 60, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depression, suicidal behavior, and 3 days of severe headaches. Neurology is consulted and an MRI is ordered, which shows a 3.0-cm mass lesion in the left temporal lobe with associated vasogenic edema that is suspicious for metastatic disease (Figure).

Ms. A is admitted to the hospital for further workup of her brain lesion. She is started on IV dexamethasone, 10 mg every 6 hours, a glucocorticosteroid, for brain edema, and levetiracetam, 500 mg twice a day, for seizure prophylaxis.

Upon admission, in addition to oncology and neurosurgery, psychiatry is also consulted to evaluate Ms. A for depression and suicidality.

EVALUATION Mood changes and poor judgment

Ms. A has a psychiatric history of depression and alcohol use disorder but says she has not consumed any alcohol in years. Her medical history includes hypertension, diabetes, and stage 4 non-small–cell lung cancer, for which she received surgery and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy 1 year ago.

On initial intake, Ms. A reports that in addition to the headaches, she has also been experiencing worsening depression and suicidal behavior. For the past 2 months, she has had a severely depressed mood, with notable anhedonia, poor appetite, insomnia, low energy, and decreased concentration. The changes in her mental health were triggered by her mother’s death. Three days prior to admission, the patient planned to overdose on antihypertensive pills, but her suicide attempt was interrupted when her family called. She denies any current suicidal ideation, intent, or plan.

According to her family, Ms. A has been increasingly irritable and her personality has changed in the past month. She also has been repeatedly sorting through her neighbors’ garbage.

Ms. A’s current psychiatric medications are duloxetine, 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 50 mg every night at bedtime; and buspirone, 10 mg/d. However, it is unclear if she is consistently taking these medications.

Continue to: On mental status examination...

On mental status examination, Ms. A is calm and she has no abnormal movements. She says she is depressed. Her affect is reactive and labile. She is alert and oriented to person, place, and time. Her attention, registration, and recall are intact. Her executive function is not tested. However, Ms. A’s insight and judgment seem poor.

To address Ms. A’s worsening depression, the psychiatry team increases her duloxetine from 30 to 60 mg/d, and she continues quetiapine, 50 mg every night at bedtime, for mood lability. Buspirone is not continued because she was not taking a therapeutic dosage in the community.

Within 4 days, Ms. A shows improvement in sleep, appetite, and mood. She has no further suicidal ideation.

[polldaddy:10511743]

The authors’ observations

Ms. A had a recurrence of what was presumed to be major depressive disorder (MDD) in the context of her mother’s death. However, she also exhibited irritability, mood lability, and impulsivity, all of which could be part of her depression, or a separate problem related to her brain tumor. Because Ms. A had never displayed bizarre behavior before the past few weeks, it is likely that her CNS lesion was directly affecting her personality and possibly underlying her planned suicide attempt.

Fifty to 80% of patients with CNS tumors, either primary or metastatic, present with psychiatric symptoms.1 Table 11-3 lists common psychiatric symptoms of brain tumors. Unfortunately, there is little reliable evidence that directly correlates tumor location with specific psychiatric symptoms. A 2010 meta-analysis found a statistically significant link between anorexia nervosa and hypothalamic tumors.1 However, for other brain regions, there is only an increased likelihood that any given tumor location will produce psychiatric symptoms.1,4 For instance, compared to patients with tumors in other locations, those with temporal lobe tumors are more likely to present with mood disorders, personality changes, and memory problems.1 In contrast, patients with frontal lobe tumors have an increased likelihood of psychosis, mood disorders, and personality changes.1 Patients with tumors in the pituitary region often present with anxiety.1

Continue to: When considering treatment options...

When considering treatment options for Ms. A, alcohol withdrawal was unlikely given the remote history of alcohol use, low alcohol blood level, and lack of evidence of unstable vital signs or tremor. Although she might have benefited from inpatient psychiatric treatment, this needed to wait until there was a definitive treatment plan for her brain tumor. Finally, although a paraneoplastic syndrome, such as limbic encephalitis, could be causing her psychiatric symptoms, this scenario is less likely with non-small–cell lung cancer.

Although uncommon, CNS tumors can present with psychiatric symptoms as the only manifestation. This is more likely when a patient exhibits new-onset or atypical symptoms, or fails to respond to standard psychiatric treatment.4 Case reports have described patients with brain tumors being misdiagnosed as having a primary psychiatric condition, which delays treatment of their CNS cancer.2 Additionally, frontal and limbic tumors are more likely to present with psychiatric manifestations; up to 90% of patients exhibit altered mental status or personality changes, as did Ms. A.1,4 Clearly, it is easier to identify patients with psychiatric symptoms resulting from a brain tumor when they also present with focal neurologic deficits or systemic symptoms, such as headache or nausea and vomiting. Ms. A presented with severe headaches, which is what led to her early imaging and prompt diagnosis.

Numerous proposed mechanisms might account for the psychiatric symptoms that occur during the course of a brain tumor, including direct injury to neuronal cells, secretion of hormones or other tumor-derived substances, and peri-ictal phenomena.3

TREATMENT Tumor is removed, but memory is impaired

Ms. A is scheduled for craniotomy and surgical resection of the frontal mass. Prior to surgery, Ms. A shows interest in improving her health, cooperates with staff, and seeks her daughter’s input on treatment. One week after admission, Ms. A has her mass resected, which is confirmed on biopsy to be a lung metastasis. Post-surgery, Ms. A receives codeine, 30 mg every 6 hours as needed, for pain; she continues dexamethasone, 4 mg IV every 6 hours, for brain edema and levetiracetam, 500 mg twice a day, for seizure prophylaxis.

On Day 2 after surgery, Ms. A attempts to elope. When she is approached by a psychiatrist on the treatment team, she does not recognize him. Although her long-term memory seems intact, she is unable to remember the details of recent events, including her medical and surgical treatments.

[polldaddy:10511745]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Ms. A’s memory impairment may be secondary to a surgically acquired neurocognitive deficit. In the United States, brain metastases represent a significant public health issue, affecting >100,000 patients per year.5 Metastatic lesions are the most common brain tumors. Lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma are the leading solid tumors to spread to the CNS.5 In cases of single brain metastasis, similar to Ms. A’s solitary left temporal lobe lesion, surgical resection plays a critical role in treatment. It provides histological confirmation of metastatic disease and can relieve mass effect if present. Studies have shown that combined surgical resection with radiation improves survival relative to patients who undergo radiation therapy alone.6,7

However, the benefits of surgical resection need to be balanced with preservation of neurologic function. Emerging evidence suggests that a majority of patients have surgically-acquired cognitive deficits due to damage of normal surrounding tissues, and these deficits are associated with reduced quality of life.8,9 Further, a study examining glioma surgical resections found that patients with left temporal lobe tumors exhibit more frequent and severe neurocognitive decline than patients with right temporal lobe tumors, especially in domains such as verbal memory.8 Ms. A’s memory impairment was persistent during her postoperative course, which suggests that it was not just an immediate post-surgical phenomenon, but a longer-lasting cognitive change directly related to the resection.

It is also possible that Ms. A had a prior neurocognitive disorder that manifested to a greater degree as a result of the CNS tumor. Ms. A might have had early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, although her intact memory before surgery makes this less likely. Alternatively, she could have had vascular dementia, especially given her long-standing hypertension and diabetes. This might have been missed in the initial evaluation because executive function was not tested. However, the relatively abrupt onset of memory problems after surgery suggests that she had no underlying neurocognitive disorder.

Ms. A’s presumed episode of MDD might also explain her memory changes. Major depressive disorder is increasingly common among geriatric patients, affecting approximately 5% of community-dwelling older adults.10 Its incidence increases with medical comorbidities, as suggested by depression rates of 5% to 10% in the primary care setting vs 37% in patients after critical-care hospitalizations.10 Late-life depression (LLD) occurs in adults age ≥60. Unlike depression in younger patients, LLD is more likely to be associated with cognitive impairment, specifically impairment of executive function and memory.11 The incidence of cognitive impairment in LLD is higher in patients with a history of depression, such as Ms. A.11,12 However, in general, patients who are depressed have memory complaints out of proportion to the clinical findings, and they show poor effort on cognitive testing. Ms. A exhibited neither of these, which makes it less likely that LLD was the exclusive cause of her memory loss.13 Table 214 outlines the management of cognitive deficits in a patient with a brain tumor.

EVALUATION Increasingly agitated and paranoid

After the tumor resection, Ms. A becomes increasingly irritable, uncooperative, and agitated. She repeatedly demands to be discharged. She insists she is fine and refuses medications and further laboratory workup. She becomes paranoid about the nursing staff and believes they are trying to kill her.

Continue to: On psychiatric re-evaluation...

On psychiatric re-evaluation, Ms. A demonstrates pressured speech, perseveration about going home, paranoid delusions, and anger at her family and physicians.

[polldaddy:10511747]

The authors’ observations

Ms. A’s refusal of medications and agitation may be explained by postoperative delirium, a surgical complication that is increasingly common among geriatric patients and is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Delirium is characterized by an acute onset and fluctuating course of symptoms that include inattention, motoric hypo- or hyperactivity, inappropriate behavior, emotional lability, cognitive dysfunction, and psychotic symptoms.15 Risk factors that contribute to postoperative delirium include older age, alcohol use, and poor baseline functional and cognitive status.16 The pathophysiology of delirium is not fully understood, but accumulating evidence suggests that different sets of interacting biologic factors (ie, neurotransmitters and inflammation) contribute to a disruption of large-scale neuronal networks in the brain, resulting in cognitive dysfunction.15 Patients who develop postoperative delirium are more likely to develop long-term cognitive dysfunction and have an increased risk of dementia.16

Another potential source of Ms. A’s agitation is steroid use. Ms. A received IV dexamethasone, 8 to 16 mg/d, around the time of her surgery. Steroids are commonly used to treat brain tumors, particularly when there is vasogenic edema. Steroid psychosis is a term loosely used to describe a wide range of psychiatric symptoms induced by corticosteroids that includes, but is not limited to, depression, mania, psychosis, delirium, and cognitive impairment.17 Steroid-induced psychiatric adverse effects occur in 5% to 18% of patients receiving corticosteroids and often happen early in treatment, although they can occur at any point.18 Corticosteroids influence brain activity via glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. These receptors are widely distributed throughout the brain and affect neurotransmitter systems, such as the serotonergic system, that are associated with changes in mood, behavior, and cognition.17 While the adverse psychiatric manifestations of steroid use vary, higher dosages are associated with an increased risk of psychiatric complications; mania is more prevalent early in the course of treatment, and depression is more common with long-term use.17,19 Table 317,18 outlines the evidence-based treatment of corticosteroid-induced adverse psychiatric effects.

Although there are no clinical guidelines or FDA-approved medications for treating steroid-induced psychiatric adverse events, these are best managed by tapering and discontinuing steroids when possible and simultaneously using psychotropic medications to treat psychiatric symptoms. Case reports and limited evidence-based literature have demonstrated that steroid-induced mania responds to mood stabilizers or antipsychotics, while depression can be managed with antidepressants or lithium.17

Additionally, patients with CNS tumors are at risk for seizures and often are prescribed antiepileptics. Because it is easy to administer and does not need to be titrated, levetiracetam is a commonly used agent. However, levetiracetam can cause psychiatric adverse effects, including behavior changes and frank psychosis.20

Continue to: Finally, Ms. A's altered mental status...

Finally, Ms. A’s altered mental status could have been related to opioid intoxication. Opioids are used to manage postsurgical pain, and studies have shown these medications can be a precipitating factor for delirium in geriatric patients.21

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

At the request of the psychiatry team, levetiracetam is discontinued due to its potential for psychiatric adverse effects. The neurosurgery team replaces it with valproic acid, 500 mg every 12 hours. Ms. A is also tapered off steroids fairly rapidly because of the potential for steroid-induced psychiatric adverse effects. Her quetiapine is titrated from 50 to 150 mg every night at bedtime, and duloxetine is discontinued.

OUTCOME Agitation improves dramatically

Ms. A’s new medication regimen dramatically improves her agitation, which allows Ms. A, her family, and the medical team to work together to establish treatment goals. Ms. A ultimately returns home with the assistance of her family. She continues to have memory issues, but with improved emotion regulation. Several months later, Ms. A is readmitted to the hospital because her cancer has progressed despite treatment.

Bottom Line

Brain tumors may present with various psychiatric manifestations that can change during the course of the patient’s treatment. A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation should parse out the interplay between direct effects of the tumor and any adverse effects that are the result of medical and/or surgical interventions to determine the cause of psychiatric symptoms and their appropriate management.

Related Resource

Madhusoodanan S, Ting MB, Farah T, et al. Psychiatric aspects of brain tumors: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(3):273-285.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buspirone • Buspar

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Codeine • Codeine systemic

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Haloperidol • Haldol

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Lorazepam • Ativan

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

CASE Suicidal behavior, severe headaches

Ms. A, age 60, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depression, suicidal behavior, and 3 days of severe headaches. Neurology is consulted and an MRI is ordered, which shows a 3.0-cm mass lesion in the left temporal lobe with associated vasogenic edema that is suspicious for metastatic disease (Figure).

Ms. A is admitted to the hospital for further workup of her brain lesion. She is started on IV dexamethasone, 10 mg every 6 hours, a glucocorticosteroid, for brain edema, and levetiracetam, 500 mg twice a day, for seizure prophylaxis.

Upon admission, in addition to oncology and neurosurgery, psychiatry is also consulted to evaluate Ms. A for depression and suicidality.

EVALUATION Mood changes and poor judgment

Ms. A has a psychiatric history of depression and alcohol use disorder but says she has not consumed any alcohol in years. Her medical history includes hypertension, diabetes, and stage 4 non-small–cell lung cancer, for which she received surgery and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy 1 year ago.

On initial intake, Ms. A reports that in addition to the headaches, she has also been experiencing worsening depression and suicidal behavior. For the past 2 months, she has had a severely depressed mood, with notable anhedonia, poor appetite, insomnia, low energy, and decreased concentration. The changes in her mental health were triggered by her mother’s death. Three days prior to admission, the patient planned to overdose on antihypertensive pills, but her suicide attempt was interrupted when her family called. She denies any current suicidal ideation, intent, or plan.

According to her family, Ms. A has been increasingly irritable and her personality has changed in the past month. She also has been repeatedly sorting through her neighbors’ garbage.

Ms. A’s current psychiatric medications are duloxetine, 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 50 mg every night at bedtime; and buspirone, 10 mg/d. However, it is unclear if she is consistently taking these medications.

Continue to: On mental status examination...

On mental status examination, Ms. A is calm and she has no abnormal movements. She says she is depressed. Her affect is reactive and labile. She is alert and oriented to person, place, and time. Her attention, registration, and recall are intact. Her executive function is not tested. However, Ms. A’s insight and judgment seem poor.

To address Ms. A’s worsening depression, the psychiatry team increases her duloxetine from 30 to 60 mg/d, and she continues quetiapine, 50 mg every night at bedtime, for mood lability. Buspirone is not continued because she was not taking a therapeutic dosage in the community.

Within 4 days, Ms. A shows improvement in sleep, appetite, and mood. She has no further suicidal ideation.

[polldaddy:10511743]

The authors’ observations

Ms. A had a recurrence of what was presumed to be major depressive disorder (MDD) in the context of her mother’s death. However, she also exhibited irritability, mood lability, and impulsivity, all of which could be part of her depression, or a separate problem related to her brain tumor. Because Ms. A had never displayed bizarre behavior before the past few weeks, it is likely that her CNS lesion was directly affecting her personality and possibly underlying her planned suicide attempt.

Fifty to 80% of patients with CNS tumors, either primary or metastatic, present with psychiatric symptoms.1 Table 11-3 lists common psychiatric symptoms of brain tumors. Unfortunately, there is little reliable evidence that directly correlates tumor location with specific psychiatric symptoms. A 2010 meta-analysis found a statistically significant link between anorexia nervosa and hypothalamic tumors.1 However, for other brain regions, there is only an increased likelihood that any given tumor location will produce psychiatric symptoms.1,4 For instance, compared to patients with tumors in other locations, those with temporal lobe tumors are more likely to present with mood disorders, personality changes, and memory problems.1 In contrast, patients with frontal lobe tumors have an increased likelihood of psychosis, mood disorders, and personality changes.1 Patients with tumors in the pituitary region often present with anxiety.1

Continue to: When considering treatment options...

When considering treatment options for Ms. A, alcohol withdrawal was unlikely given the remote history of alcohol use, low alcohol blood level, and lack of evidence of unstable vital signs or tremor. Although she might have benefited from inpatient psychiatric treatment, this needed to wait until there was a definitive treatment plan for her brain tumor. Finally, although a paraneoplastic syndrome, such as limbic encephalitis, could be causing her psychiatric symptoms, this scenario is less likely with non-small–cell lung cancer.

Although uncommon, CNS tumors can present with psychiatric symptoms as the only manifestation. This is more likely when a patient exhibits new-onset or atypical symptoms, or fails to respond to standard psychiatric treatment.4 Case reports have described patients with brain tumors being misdiagnosed as having a primary psychiatric condition, which delays treatment of their CNS cancer.2 Additionally, frontal and limbic tumors are more likely to present with psychiatric manifestations; up to 90% of patients exhibit altered mental status or personality changes, as did Ms. A.1,4 Clearly, it is easier to identify patients with psychiatric symptoms resulting from a brain tumor when they also present with focal neurologic deficits or systemic symptoms, such as headache or nausea and vomiting. Ms. A presented with severe headaches, which is what led to her early imaging and prompt diagnosis.

Numerous proposed mechanisms might account for the psychiatric symptoms that occur during the course of a brain tumor, including direct injury to neuronal cells, secretion of hormones or other tumor-derived substances, and peri-ictal phenomena.3

TREATMENT Tumor is removed, but memory is impaired

Ms. A is scheduled for craniotomy and surgical resection of the frontal mass. Prior to surgery, Ms. A shows interest in improving her health, cooperates with staff, and seeks her daughter’s input on treatment. One week after admission, Ms. A has her mass resected, which is confirmed on biopsy to be a lung metastasis. Post-surgery, Ms. A receives codeine, 30 mg every 6 hours as needed, for pain; she continues dexamethasone, 4 mg IV every 6 hours, for brain edema and levetiracetam, 500 mg twice a day, for seizure prophylaxis.

On Day 2 after surgery, Ms. A attempts to elope. When she is approached by a psychiatrist on the treatment team, she does not recognize him. Although her long-term memory seems intact, she is unable to remember the details of recent events, including her medical and surgical treatments.

[polldaddy:10511745]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Ms. A’s memory impairment may be secondary to a surgically acquired neurocognitive deficit. In the United States, brain metastases represent a significant public health issue, affecting >100,000 patients per year.5 Metastatic lesions are the most common brain tumors. Lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma are the leading solid tumors to spread to the CNS.5 In cases of single brain metastasis, similar to Ms. A’s solitary left temporal lobe lesion, surgical resection plays a critical role in treatment. It provides histological confirmation of metastatic disease and can relieve mass effect if present. Studies have shown that combined surgical resection with radiation improves survival relative to patients who undergo radiation therapy alone.6,7

However, the benefits of surgical resection need to be balanced with preservation of neurologic function. Emerging evidence suggests that a majority of patients have surgically-acquired cognitive deficits due to damage of normal surrounding tissues, and these deficits are associated with reduced quality of life.8,9 Further, a study examining glioma surgical resections found that patients with left temporal lobe tumors exhibit more frequent and severe neurocognitive decline than patients with right temporal lobe tumors, especially in domains such as verbal memory.8 Ms. A’s memory impairment was persistent during her postoperative course, which suggests that it was not just an immediate post-surgical phenomenon, but a longer-lasting cognitive change directly related to the resection.

It is also possible that Ms. A had a prior neurocognitive disorder that manifested to a greater degree as a result of the CNS tumor. Ms. A might have had early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, although her intact memory before surgery makes this less likely. Alternatively, she could have had vascular dementia, especially given her long-standing hypertension and diabetes. This might have been missed in the initial evaluation because executive function was not tested. However, the relatively abrupt onset of memory problems after surgery suggests that she had no underlying neurocognitive disorder.

Ms. A’s presumed episode of MDD might also explain her memory changes. Major depressive disorder is increasingly common among geriatric patients, affecting approximately 5% of community-dwelling older adults.10 Its incidence increases with medical comorbidities, as suggested by depression rates of 5% to 10% in the primary care setting vs 37% in patients after critical-care hospitalizations.10 Late-life depression (LLD) occurs in adults age ≥60. Unlike depression in younger patients, LLD is more likely to be associated with cognitive impairment, specifically impairment of executive function and memory.11 The incidence of cognitive impairment in LLD is higher in patients with a history of depression, such as Ms. A.11,12 However, in general, patients who are depressed have memory complaints out of proportion to the clinical findings, and they show poor effort on cognitive testing. Ms. A exhibited neither of these, which makes it less likely that LLD was the exclusive cause of her memory loss.13 Table 214 outlines the management of cognitive deficits in a patient with a brain tumor.

EVALUATION Increasingly agitated and paranoid

After the tumor resection, Ms. A becomes increasingly irritable, uncooperative, and agitated. She repeatedly demands to be discharged. She insists she is fine and refuses medications and further laboratory workup. She becomes paranoid about the nursing staff and believes they are trying to kill her.

Continue to: On psychiatric re-evaluation...

On psychiatric re-evaluation, Ms. A demonstrates pressured speech, perseveration about going home, paranoid delusions, and anger at her family and physicians.

[polldaddy:10511747]

The authors’ observations

Ms. A’s refusal of medications and agitation may be explained by postoperative delirium, a surgical complication that is increasingly common among geriatric patients and is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Delirium is characterized by an acute onset and fluctuating course of symptoms that include inattention, motoric hypo- or hyperactivity, inappropriate behavior, emotional lability, cognitive dysfunction, and psychotic symptoms.15 Risk factors that contribute to postoperative delirium include older age, alcohol use, and poor baseline functional and cognitive status.16 The pathophysiology of delirium is not fully understood, but accumulating evidence suggests that different sets of interacting biologic factors (ie, neurotransmitters and inflammation) contribute to a disruption of large-scale neuronal networks in the brain, resulting in cognitive dysfunction.15 Patients who develop postoperative delirium are more likely to develop long-term cognitive dysfunction and have an increased risk of dementia.16

Another potential source of Ms. A’s agitation is steroid use. Ms. A received IV dexamethasone, 8 to 16 mg/d, around the time of her surgery. Steroids are commonly used to treat brain tumors, particularly when there is vasogenic edema. Steroid psychosis is a term loosely used to describe a wide range of psychiatric symptoms induced by corticosteroids that includes, but is not limited to, depression, mania, psychosis, delirium, and cognitive impairment.17 Steroid-induced psychiatric adverse effects occur in 5% to 18% of patients receiving corticosteroids and often happen early in treatment, although they can occur at any point.18 Corticosteroids influence brain activity via glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. These receptors are widely distributed throughout the brain and affect neurotransmitter systems, such as the serotonergic system, that are associated with changes in mood, behavior, and cognition.17 While the adverse psychiatric manifestations of steroid use vary, higher dosages are associated with an increased risk of psychiatric complications; mania is more prevalent early in the course of treatment, and depression is more common with long-term use.17,19 Table 317,18 outlines the evidence-based treatment of corticosteroid-induced adverse psychiatric effects.

Although there are no clinical guidelines or FDA-approved medications for treating steroid-induced psychiatric adverse events, these are best managed by tapering and discontinuing steroids when possible and simultaneously using psychotropic medications to treat psychiatric symptoms. Case reports and limited evidence-based literature have demonstrated that steroid-induced mania responds to mood stabilizers or antipsychotics, while depression can be managed with antidepressants or lithium.17

Additionally, patients with CNS tumors are at risk for seizures and often are prescribed antiepileptics. Because it is easy to administer and does not need to be titrated, levetiracetam is a commonly used agent. However, levetiracetam can cause psychiatric adverse effects, including behavior changes and frank psychosis.20

Continue to: Finally, Ms. A's altered mental status...

Finally, Ms. A’s altered mental status could have been related to opioid intoxication. Opioids are used to manage postsurgical pain, and studies have shown these medications can be a precipitating factor for delirium in geriatric patients.21

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

At the request of the psychiatry team, levetiracetam is discontinued due to its potential for psychiatric adverse effects. The neurosurgery team replaces it with valproic acid, 500 mg every 12 hours. Ms. A is also tapered off steroids fairly rapidly because of the potential for steroid-induced psychiatric adverse effects. Her quetiapine is titrated from 50 to 150 mg every night at bedtime, and duloxetine is discontinued.

OUTCOME Agitation improves dramatically

Ms. A’s new medication regimen dramatically improves her agitation, which allows Ms. A, her family, and the medical team to work together to establish treatment goals. Ms. A ultimately returns home with the assistance of her family. She continues to have memory issues, but with improved emotion regulation. Several months later, Ms. A is readmitted to the hospital because her cancer has progressed despite treatment.

Bottom Line

Brain tumors may present with various psychiatric manifestations that can change during the course of the patient’s treatment. A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation should parse out the interplay between direct effects of the tumor and any adverse effects that are the result of medical and/or surgical interventions to determine the cause of psychiatric symptoms and their appropriate management.

Related Resource

Madhusoodanan S, Ting MB, Farah T, et al. Psychiatric aspects of brain tumors: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(3):273-285.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buspirone • Buspar

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Codeine • Codeine systemic

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Haloperidol • Haldol

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Lorazepam • Ativan

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

1. Madhusoodanan S, Opler MG, Moise D, et al. Brain tumor location and psychiatric symptoms: is there any association? A meta-analysis of published case studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(10):1529-1536.

2. Bunevicius A, Deltuva VP, Deltuviene D, et al. Brain lesions manifesting as psychiatric disorders: eight cases. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):950-958.

3. Pearl ML, Talgat G, Valea FA, et al. Psychiatric symptoms due to brain metastases. Med Update Psychiatr. 1998;3(4):91-94.

4. Madhusoodanan S, Danan D, Moise D. Psychiatric manifestations of brain tumors: diagnostic implications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(4):343-349.

5. Ferguson SD, Wagner KM, Prabhu SS, et al. Neurosurgical management of brain metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2017;34(6-7):377-389.

6. Husain ZA, Regine WF, Kwok Y, et al. Brain metastases: contemporary management and future directions. Eur J Clin Med Oncol. 2011;3(3):38-45.

7. Vecht CJ, Haaxmareiche H, Noordijk EM, et al. Treatment of single brain metastasis - radiotherapy alone or combined with neurosurgery. Ann Neurol. 1993;33(6):583-590.

8. Barry RL, Byun NE, Tantawy MN, et al. In vivo neuroimaging and behavioral correlates in a rat model of chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(1):87-95.

9. Wu AS, Witgert ME, Lang FF, et al. Neurocognitive function before and after surgery for insular gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(6):1115-1125.

10. Taylor WD. Depression in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1228-1236.

11. Liguori C, Pierantozzi M, Chiaravalloti A, et al. When cognitive decline and depression coexist in the elderly: CSF biomarkers analysis can differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from late-life depression. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:38.

12. Luijendijk HJ, van den Berg JF, Dekker MJHJ, et al. Incidence and recurrence of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1394-1401.

13. Potter GG, Steffens DC. Contribution of depression to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults. Neurologist. 2007;13(3):105-117.

14. Taphoorn MJB, Klein M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(3):159-168.

15. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

16. Sprung J, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, et al. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients is associated with subsequent cognitive impairment. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(2):316-323.

17. Kusljic S, Manias E, Gogos A. Corticosteroid-induced psychiatric disturbances: it is time for pharmacists to take notice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(2):355-360.

18. Cerullo MA. Corticosteroid-induced mania: prepare for the unpredictable. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(6):43-50.

19. Dubovsky AN, Arvikar S, Stern TA, et al. Steroid psychosis revisited. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):103-115.

20. Habets JGV, Leentjens AFG, Schijns OEMG. Serious and reversible levetiracetam-induced psychiatric symptoms after resection of frontal low-grade glioma: two case histories. Br J Neurosurg. 2017;31(4):471-473.

21

1. Madhusoodanan S, Opler MG, Moise D, et al. Brain tumor location and psychiatric symptoms: is there any association? A meta-analysis of published case studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(10):1529-1536.

2. Bunevicius A, Deltuva VP, Deltuviene D, et al. Brain lesions manifesting as psychiatric disorders: eight cases. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):950-958.

3. Pearl ML, Talgat G, Valea FA, et al. Psychiatric symptoms due to brain metastases. Med Update Psychiatr. 1998;3(4):91-94.

4. Madhusoodanan S, Danan D, Moise D. Psychiatric manifestations of brain tumors: diagnostic implications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(4):343-349.

5. Ferguson SD, Wagner KM, Prabhu SS, et al. Neurosurgical management of brain metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2017;34(6-7):377-389.

6. Husain ZA, Regine WF, Kwok Y, et al. Brain metastases: contemporary management and future directions. Eur J Clin Med Oncol. 2011;3(3):38-45.

7. Vecht CJ, Haaxmareiche H, Noordijk EM, et al. Treatment of single brain metastasis - radiotherapy alone or combined with neurosurgery. Ann Neurol. 1993;33(6):583-590.

8. Barry RL, Byun NE, Tantawy MN, et al. In vivo neuroimaging and behavioral correlates in a rat model of chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(1):87-95.

9. Wu AS, Witgert ME, Lang FF, et al. Neurocognitive function before and after surgery for insular gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(6):1115-1125.

10. Taylor WD. Depression in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1228-1236.

11. Liguori C, Pierantozzi M, Chiaravalloti A, et al. When cognitive decline and depression coexist in the elderly: CSF biomarkers analysis can differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from late-life depression. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:38.

12. Luijendijk HJ, van den Berg JF, Dekker MJHJ, et al. Incidence and recurrence of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1394-1401.

13. Potter GG, Steffens DC. Contribution of depression to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults. Neurologist. 2007;13(3):105-117.

14. Taphoorn MJB, Klein M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(3):159-168.

15. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

16. Sprung J, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, et al. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients is associated with subsequent cognitive impairment. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(2):316-323.

17. Kusljic S, Manias E, Gogos A. Corticosteroid-induced psychiatric disturbances: it is time for pharmacists to take notice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(2):355-360.

18. Cerullo MA. Corticosteroid-induced mania: prepare for the unpredictable. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(6):43-50.

19. Dubovsky AN, Arvikar S, Stern TA, et al. Steroid psychosis revisited. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):103-115.

20. Habets JGV, Leentjens AFG, Schijns OEMG. Serious and reversible levetiracetam-induced psychiatric symptoms after resection of frontal low-grade glioma: two case histories. Br J Neurosurg. 2017;31(4):471-473.

21

USPSTF again deems evidence insufficient to recommend cognitive impairment screening in older adults

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed the current evidence “insufficient” to make a recommendation in regard to screening for cognitive impairment in adults aged 65 years or older.

“More research is needed on the effect of screening and early detection of cognitive impairment on important patient, caregiver, and societal outcomes, including decision making, advance planning, and caregiver outcomes,” wrote lead author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the task force. The statement was published in JAMA.

To update a 2014 recommendation from the USPSTF, which also found insufficient evidence to properly assess cognitive screening’s benefits and harms, the task force commissioned a systematic review of studies applicable to community-dwelling older adults who are not exhibiting signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment. For their statement, “cognitive impairment” is defined as mild cognitive impairment and mild to moderate dementia.

Ultimately, they determined several factors that limited the overall evidence, including the short duration of most trials and the heterogenous nature of interventions and inconsistencies in outcomes reported. Any evidence that suggested improvements was mostly applicable to patients with moderate dementia, meaning “its applicability to a screen-detected population is uncertain.”

Updating 2014 recommendations

Their statement was based on an evidence report, also published in JAMA, in which a team of researchers reviewed 287 studies that included more than 285,000 older adults; 92 of the studies were newly identified, while the other 195 were carried forward from the 2014 recommendation’s review. The researchers sought the answers to five key questions, carrying over the framework from the previous review.

“Despite the accumulation of new data, the conclusions for these key questions are essentially unchanged from the prior review,” wrote lead author Carrie D. Patnode, PhD, of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and coauthors.

Of the questions – which concerned the accuracy of screening instruments; the harms of screening; the harms of interventions; and if screening or interventions improved decision making or outcomes for the patient, family/caregiver, or society – moderate evidence was found to support the accuracy of the instruments, treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for patients with moderate dementia, and psychoeducation interventions for caregivers of patients with moderate dementia. At the same time, there was moderate evidence of adverse effects from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in patients with moderate dementia.

“I think, eventually, there will be sufficient evidence to justify screening, once we have what I call a tiered approach,” Marwan Sabbagh, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, said in an interview. “The very near future will include blood tests for Alzheimer’s, or PET scans, or genetics, or something else. Right now, the cognitive screens lack the specificity and sensitivity, and the secondary screening infrastructure that would improve the accuracy doesn’t exist yet.

“I think this is a ‘not now,’ ” he added, “but I wouldn’t say ‘not ever.’ ”

Dr. Patnode and coauthors noted specific limitations in the evidence, including a lack of studies on how screening for and treating cognitive impairment affects decision making. In addition, details like quality of life and institutionalization were inconsistently reported, and “consistent and standardized reporting of results according to meaningful thresholds of clinical significance” would have been valuable across all measures.

Clinical implications

The implications of this report’s conclusions are substantial, especially as the rising prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia becomes a worldwide concern, wrote Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and Kristine Yaffe, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

Though the data does not explicitly support screening, Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe noted that it still may have benefits. An estimated 10% of cognitive impairment is caused by at least somewhat reversible causes, and screening could also be used to improve care in medical problems that are worsened by cognitive impairment. To find the true value of these efforts, they wrote, researchers need to design and execute additional clinical trials that “answer many of the important questions surrounding screening and treatment of cognitive impairment.”

“The absence of evidence for benefit may lead to inaction,” they added, noting that clinicians screening should still consider the value of screening on a case-by-case basis in order to keep up with the impact of new disease-modifying therapies for certain neurodegenerative diseases.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. One member reported receiving grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The study was funded by the Department of Health & Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe reported consulting for, and receiving funding from, various pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and government organizations.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0435; Patnode CD et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22258.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed the current evidence “insufficient” to make a recommendation in regard to screening for cognitive impairment in adults aged 65 years or older.

“More research is needed on the effect of screening and early detection of cognitive impairment on important patient, caregiver, and societal outcomes, including decision making, advance planning, and caregiver outcomes,” wrote lead author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the task force. The statement was published in JAMA.

To update a 2014 recommendation from the USPSTF, which also found insufficient evidence to properly assess cognitive screening’s benefits and harms, the task force commissioned a systematic review of studies applicable to community-dwelling older adults who are not exhibiting signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment. For their statement, “cognitive impairment” is defined as mild cognitive impairment and mild to moderate dementia.

Ultimately, they determined several factors that limited the overall evidence, including the short duration of most trials and the heterogenous nature of interventions and inconsistencies in outcomes reported. Any evidence that suggested improvements was mostly applicable to patients with moderate dementia, meaning “its applicability to a screen-detected population is uncertain.”

Updating 2014 recommendations

Their statement was based on an evidence report, also published in JAMA, in which a team of researchers reviewed 287 studies that included more than 285,000 older adults; 92 of the studies were newly identified, while the other 195 were carried forward from the 2014 recommendation’s review. The researchers sought the answers to five key questions, carrying over the framework from the previous review.

“Despite the accumulation of new data, the conclusions for these key questions are essentially unchanged from the prior review,” wrote lead author Carrie D. Patnode, PhD, of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and coauthors.

Of the questions – which concerned the accuracy of screening instruments; the harms of screening; the harms of interventions; and if screening or interventions improved decision making or outcomes for the patient, family/caregiver, or society – moderate evidence was found to support the accuracy of the instruments, treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for patients with moderate dementia, and psychoeducation interventions for caregivers of patients with moderate dementia. At the same time, there was moderate evidence of adverse effects from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in patients with moderate dementia.

“I think, eventually, there will be sufficient evidence to justify screening, once we have what I call a tiered approach,” Marwan Sabbagh, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, said in an interview. “The very near future will include blood tests for Alzheimer’s, or PET scans, or genetics, or something else. Right now, the cognitive screens lack the specificity and sensitivity, and the secondary screening infrastructure that would improve the accuracy doesn’t exist yet.

“I think this is a ‘not now,’ ” he added, “but I wouldn’t say ‘not ever.’ ”

Dr. Patnode and coauthors noted specific limitations in the evidence, including a lack of studies on how screening for and treating cognitive impairment affects decision making. In addition, details like quality of life and institutionalization were inconsistently reported, and “consistent and standardized reporting of results according to meaningful thresholds of clinical significance” would have been valuable across all measures.

Clinical implications

The implications of this report’s conclusions are substantial, especially as the rising prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia becomes a worldwide concern, wrote Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and Kristine Yaffe, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

Though the data does not explicitly support screening, Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe noted that it still may have benefits. An estimated 10% of cognitive impairment is caused by at least somewhat reversible causes, and screening could also be used to improve care in medical problems that are worsened by cognitive impairment. To find the true value of these efforts, they wrote, researchers need to design and execute additional clinical trials that “answer many of the important questions surrounding screening and treatment of cognitive impairment.”

“The absence of evidence for benefit may lead to inaction,” they added, noting that clinicians screening should still consider the value of screening on a case-by-case basis in order to keep up with the impact of new disease-modifying therapies for certain neurodegenerative diseases.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. One member reported receiving grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The study was funded by the Department of Health & Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe reported consulting for, and receiving funding from, various pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and government organizations.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0435; Patnode CD et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22258.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed the current evidence “insufficient” to make a recommendation in regard to screening for cognitive impairment in adults aged 65 years or older.

“More research is needed on the effect of screening and early detection of cognitive impairment on important patient, caregiver, and societal outcomes, including decision making, advance planning, and caregiver outcomes,” wrote lead author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the task force. The statement was published in JAMA.

To update a 2014 recommendation from the USPSTF, which also found insufficient evidence to properly assess cognitive screening’s benefits and harms, the task force commissioned a systematic review of studies applicable to community-dwelling older adults who are not exhibiting signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment. For their statement, “cognitive impairment” is defined as mild cognitive impairment and mild to moderate dementia.

Ultimately, they determined several factors that limited the overall evidence, including the short duration of most trials and the heterogenous nature of interventions and inconsistencies in outcomes reported. Any evidence that suggested improvements was mostly applicable to patients with moderate dementia, meaning “its applicability to a screen-detected population is uncertain.”

Updating 2014 recommendations

Their statement was based on an evidence report, also published in JAMA, in which a team of researchers reviewed 287 studies that included more than 285,000 older adults; 92 of the studies were newly identified, while the other 195 were carried forward from the 2014 recommendation’s review. The researchers sought the answers to five key questions, carrying over the framework from the previous review.

“Despite the accumulation of new data, the conclusions for these key questions are essentially unchanged from the prior review,” wrote lead author Carrie D. Patnode, PhD, of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and coauthors.

Of the questions – which concerned the accuracy of screening instruments; the harms of screening; the harms of interventions; and if screening or interventions improved decision making or outcomes for the patient, family/caregiver, or society – moderate evidence was found to support the accuracy of the instruments, treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for patients with moderate dementia, and psychoeducation interventions for caregivers of patients with moderate dementia. At the same time, there was moderate evidence of adverse effects from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in patients with moderate dementia.

“I think, eventually, there will be sufficient evidence to justify screening, once we have what I call a tiered approach,” Marwan Sabbagh, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, said in an interview. “The very near future will include blood tests for Alzheimer’s, or PET scans, or genetics, or something else. Right now, the cognitive screens lack the specificity and sensitivity, and the secondary screening infrastructure that would improve the accuracy doesn’t exist yet.

“I think this is a ‘not now,’ ” he added, “but I wouldn’t say ‘not ever.’ ”

Dr. Patnode and coauthors noted specific limitations in the evidence, including a lack of studies on how screening for and treating cognitive impairment affects decision making. In addition, details like quality of life and institutionalization were inconsistently reported, and “consistent and standardized reporting of results according to meaningful thresholds of clinical significance” would have been valuable across all measures.

Clinical implications

The implications of this report’s conclusions are substantial, especially as the rising prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia becomes a worldwide concern, wrote Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and Kristine Yaffe, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

Though the data does not explicitly support screening, Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe noted that it still may have benefits. An estimated 10% of cognitive impairment is caused by at least somewhat reversible causes, and screening could also be used to improve care in medical problems that are worsened by cognitive impairment. To find the true value of these efforts, they wrote, researchers need to design and execute additional clinical trials that “answer many of the important questions surrounding screening and treatment of cognitive impairment.”

“The absence of evidence for benefit may lead to inaction,” they added, noting that clinicians screening should still consider the value of screening on a case-by-case basis in order to keep up with the impact of new disease-modifying therapies for certain neurodegenerative diseases.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. One member reported receiving grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The study was funded by the Department of Health & Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe reported consulting for, and receiving funding from, various pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and government organizations.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0435; Patnode CD et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22258.

FROM JAMA

As costs for neurologic drugs rise, adherence to therapy drops

For their study, published online Feb. 19 in Neurology, Brian C. Callaghan, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues looked at claims records from a large national private insurer to identify new cases of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and neuropathy between 2001 and 2016, along with pharmacy records following diagnoses.

The researchers identified more than 52,000 patients with neuropathy on gabapentinoids and another 5,000 treated with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for the same. They also identified some 20,000 patients with dementia taking cholinesterase inhibitors, and 3,000 with Parkinson’s disease taking dopamine agonists. Dr. Callaghan and colleagues compared patient adherence over 6 months for pairs of drugs in the same class with similar or equal efficacy, but with different costs to the patient.

Such cost differences can be stark: The researchers noted that the average 2016 out-of-pocket cost for 30 days of pregabalin, a drug used in the treatment of peripheral neuropathy, was $65.70, compared with $8.40 for gabapentin. With two common dementia drugs the difference was even more pronounced: $79.30 for rivastigmine compared with $3.10 for donepezil, both cholinesterase inhibitors with similar efficacy and tolerability.

Dr. Callaghan and colleagues found that such cost differences bore significantly on patient adherence. An increase of $50 in patient costs was seen decreasing adherence by 9% for neuropathy patients on gabapentinoids (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.91, 0.89-0.93) and by 12% for dementia patients on cholinesterase inhibitors (adjusted IRR 0.88, 0.86-0.91, P less than .05 for both). Similar price-linked decreases were seen for neuropathy patients on SNRIs and Parkinson’s patients on dopamine agonists, but the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Black, Asian, and Hispanic patients saw greater drops in adherence than did white patients associated with the same out-of-pocket cost differences, leading the researchers to note that special care should be taken in prescribing decisions for these populations.

“When choosing among medications with differential [out-of-pocket] costs, prescribing the medication with lower [out-of-pocket] expense will likely improve medication adherence while reducing overall costs,” Dr. Callaghan and colleagues wrote in their analysis. “For example, prescribing gabapentin or venlafaxine to patients with newly diagnosed neuropathy is likely to lead to higher adherence compared with pregabalin or duloxetine, and therefore, there is a higher likelihood of relief from neuropathic pain.” The researchers noted that while combination pills and extended-release formulations may be marketed as a way to increase adherence, the higher out-of-pocket costs of such medicines could offset any adherence benefit.

Dr. Callaghan and his colleagues described as strengths of their study its large sample and statistical approach that “allowed us to best estimate the causal relationship between [out-of-pocket] costs and medication adherence by limiting selection bias, residual confounding, and the confounding inherent to medication choice.” Nonadherence – patients who never filled a prescription after diagnosis – was not captured in the study.

The American Academy of Neurology funded the study. Two of its authors reported financial conflicts of interest in the form of compensation from pharmaceutical or device companies. Its lead author, Dr. Callaghan, reported funding for a device maker and performing medical legal consultations.

SOURCE: Reynolds EL et al. Neurology. 2020 Feb 19. doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009039.