User login

Clinical pearls for administering cognitive exams during the pandemic

Patients have often been labeled as “poor historians” if they are not able to recollect their own medical history, whether through illness or difficulties in communication. But Fred Ovsiew, MD, speaking at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sees that label as an excuse on the part of the clinician.

“I strongly advise you to drop that phrase from your vocabulary if you do use it, because the patient is not the historian. The doctor, the clinician is the historian,” Dr. Ovsiew said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. “It is the clinician’s job to put the story together using the account by the patient as one source, but [also] interviewing a collateral informant and/or reviewing records, which is necessary in almost every case of a neuropsychiatric illness.”

Rather, clinicians taking history at the bedside should focus on why the patients cannot give a narrative account of their illness. Patients can have narrative incapacity on a psychogenic basis, such as in patients with conversion or somatoform disorder, he explained. “I think this is a result of the narrative incapacity that develops in people who have had trauma or adverse experiences in childhood and insecure attachment. This is shown on the adult attachment interview as a disorganized account of their childhoods.”

Other patients might not be able to recount their medical history because they are amnestic, which leaves their account vague because of a lack of access to information. “It may be frozen in time in the sense that, up to a certain point in their life, they can recount the history,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “But in recent years, their account becomes vague.”

Patients with right hemisphere lesions might not know that their account has incongruity and is implausible, while patients with dorsolateral prefrontal lesions might be aspontaneous, use few words to describe their situation, and have poor insight. Those with ventromedial prefrontal lesions can be impulsive and have poor insight, not considering alternative possibilities, Dr. Ovsiew noted.

Asking open-ended questions of the patient is the first step to identifying any potential narrative incapacity, followed by a detailed medical history by the clinician. When taking a medical history, try avoiding what Dr. Ovsiew calls the “anything like that?” problem, where a clinician asks a question about a cluster of symptoms that would make sense to a doctor, but not a patient. For example, a doctor might ask whether a patient is experiencing “chest pain or leg swelling – anything like that?” because he or she knows what those symptoms have in common, but the patient might not know the relationship between those symptoms. “You can’t count on the patient to tell you all the relevant information,” he said. “You have to know what to ask about.”

“Patients with brain disease have subtle personality changes, sometimes more obvious personality changes. These need to be inquired about,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “The patient with apathy has reduced negative as well as positive emotions. The patient with depression has reduced positive emotions, but often tells you very clearly about the negative emotions of sadness, guilt. The patient with depression has diurnal variation in mood, a very telling symptom, especially when it’s disclosed spontaneously,” Dr. Ovsiew explained. “The point is, you need to know to ask about it.”

When taking a sleep history, clinicians should be aware of sleep disturbances apart from insomnia and early waking. REM sleep behavior disorder is a condition that should be inquired about. Obstructive sleep apnea is a condition that might not be immediately apparent to the patient, but a bed partner can identify whether a patient has problems breathing throughout the night.

“This is an important condition to uncover for the neuropsychiatrist because it contributes to treatment resistance and depression, and it contributes to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “These patients commonly have mild difficulties with attention and concentration.”

Always ask about head injury in every history, which can be relevant to later onset depression, PTSD, and cognitive impairment. Every head injury follows a trajectory of retrograde amnesia and altered state of consciousness (including coma), followed by a period of posttraumatic amnesia. Duration of these states can be used to assess the severity of brain injury, but the 15-point Glasgow Coma Scale is another way to assess injury severity, Dr. Ovsiew explained.

However, the two do not always overlap, he noted. “Someone may have a Glasgow Coma Scale score that is 9-12, predicting moderate brain injury, but they may have a short duration of amnesia. These don’t always follow the same path. There are many different ways of classifying how severe the brain injury is.”

Keep probes brief, straightforward

Cognitive exams of patients with suspected psychiatric disorders should be simple, easy to administer and focused on a single domain of cognition. “Probes should be brief. They should not require specialized equipment. The Purdue Pegboard Test might be a great neuropsychological instrument, but very few of us carry a pegboard around in our medical bags,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

The probe administered should also be accessible to the patient. The serial sevens clinical test, where a patient is asked to repeatedly subtract 7 from 100, is only effective at testing concentration if the patient is capable of completing the test. “There are going to be patients who can’t do the task, but it’s not because of concentration failure, it’s because of subtraction failure,” he said.

When assessing attention, effective tasks include having the patient perform the digit span test forward and backward, count backward from 20 to 1, listing the months of the year in reverse, and performing the Mental Alternation Test. However, Dr. Ovsiew explained there may be some barriers for patients in completing these tasks. “The person may be aphasic and not know the alphabet. The person may have English as a second language and not be skilled at giving the alphabet in English. In some cases, you may want to check and not assume that the patient can count and does know the alphabet.”

In assessing language, listen for aphasic abnormalities. “The patient, of course, is speaking throughout the interview, but you need to take a moment to listen for prosody, to listen to rate of speech, to listen for paraphasic errors or word-finding problems,” Dr. Ovsiew said. Any abnormalities should be probed further through confrontation naming tasks, which can be done in person and with some success through video, but not by phone. Naming to definition (“What do you call the part of a shirt that covers the arm?”) is one way of administering the test over the phone.

Visuospatial function can be assessed by clock drawing but also carries problems. Patients who do not plan their clock before beginning to draw, for example, may have an executive function problem instead of a visuospatial problem, Dr. Ovsiew noted. Patients in whom a clinician suspects hemineglect should be given a visual search task or line by section task. “I like doing clock drawing. It’s a nice screening test. It’s becoming, I think, less useful as people count on digital clocks and have trouble even imagining what an analog clock looks like.”

An approach that is better suited to in-person assessment, but also works by video, is the Poppelreuter figure visual perceptual function test, which is a prompt for the patient that involves common household items overlaying one another “in atypical positions and atypical configurations” where the patient is instructed to describe the items they see on the card. Another approach that works over video is the interlocking finger test, where the patient is asked to copy the hand positions made by the clinician.

Dr. Ovsiew admitted that visuospatial function is nearly impossible to assess over the phone. Asking topographical questions (“If you’re driving from Chicago to Los Angeles, is the Pacific Ocean in front of you, behind you, to your left, or to your right?”) may help judge visuospatial function, but this relies on the patient having the topographic knowledge to answer the questions. Some patients who are topographically disoriented can’t do them at all,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Bedside neuropsychiatry assesses encoding of a memory, its retention and its retrieval as well as verbal and visual cues. Each one of these aspects of memory can be impaired on its own and should be explored separately, Dr. Ovsiew explained. “Neuropsychiatric clinicians have a rough-and-ready, seat-of-the-pants way of approaching this that wouldn’t pass muster if you’re a psychologist, but is the best we can do at the bedside.”

To test retrieval and retention, the Three Words–Three Shapes test works well in person, with some difficulty by video, and is not possible to administer over the phone. In lieu of that test, giving the patient a simple word list and asking them to repeat the list in order. Using the word list, “these different stages of memory function can be parsed out pretty well at the bedside or chairside, and even by the phone. Figuring out where the memory failure is diagnostically important,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Executive function, which involves activation, planning, sequencing, maintaining, self-monitoring, and flexible employment of action and attention, is “complicated to evaluate because there are multiple aspects of executive function, multiple deficits that can be seen with executive dysfunction, and they don’t all correlate with each other.”

Within executive function evaluation, the Mental Alternation Test can assess working memory, motor sequencing can be assessed through the ring/fist, fist/edge/palm, alternating fist, and rampart tests. The Go/No-Go test can be used to assess response inhibition. For effortful retrieval evaluation, spontaneous word-list generation – such as thinking of all the items one can buy at a supermarket– can test category fluency, while a task to name all the words starting with a certain letter can assess letter stimulus.

Executive function “is of crucial importance in the neuropsychiatric evaluation because it’s strongly correlated with how well the person functions outside the office,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Ovsiew reported relationships with Wolters Kluwer Health in the form of consulting, receiving royalty payments, and related activities.

Patients have often been labeled as “poor historians” if they are not able to recollect their own medical history, whether through illness or difficulties in communication. But Fred Ovsiew, MD, speaking at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sees that label as an excuse on the part of the clinician.

“I strongly advise you to drop that phrase from your vocabulary if you do use it, because the patient is not the historian. The doctor, the clinician is the historian,” Dr. Ovsiew said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. “It is the clinician’s job to put the story together using the account by the patient as one source, but [also] interviewing a collateral informant and/or reviewing records, which is necessary in almost every case of a neuropsychiatric illness.”

Rather, clinicians taking history at the bedside should focus on why the patients cannot give a narrative account of their illness. Patients can have narrative incapacity on a psychogenic basis, such as in patients with conversion or somatoform disorder, he explained. “I think this is a result of the narrative incapacity that develops in people who have had trauma or adverse experiences in childhood and insecure attachment. This is shown on the adult attachment interview as a disorganized account of their childhoods.”

Other patients might not be able to recount their medical history because they are amnestic, which leaves their account vague because of a lack of access to information. “It may be frozen in time in the sense that, up to a certain point in their life, they can recount the history,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “But in recent years, their account becomes vague.”

Patients with right hemisphere lesions might not know that their account has incongruity and is implausible, while patients with dorsolateral prefrontal lesions might be aspontaneous, use few words to describe their situation, and have poor insight. Those with ventromedial prefrontal lesions can be impulsive and have poor insight, not considering alternative possibilities, Dr. Ovsiew noted.

Asking open-ended questions of the patient is the first step to identifying any potential narrative incapacity, followed by a detailed medical history by the clinician. When taking a medical history, try avoiding what Dr. Ovsiew calls the “anything like that?” problem, where a clinician asks a question about a cluster of symptoms that would make sense to a doctor, but not a patient. For example, a doctor might ask whether a patient is experiencing “chest pain or leg swelling – anything like that?” because he or she knows what those symptoms have in common, but the patient might not know the relationship between those symptoms. “You can’t count on the patient to tell you all the relevant information,” he said. “You have to know what to ask about.”

“Patients with brain disease have subtle personality changes, sometimes more obvious personality changes. These need to be inquired about,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “The patient with apathy has reduced negative as well as positive emotions. The patient with depression has reduced positive emotions, but often tells you very clearly about the negative emotions of sadness, guilt. The patient with depression has diurnal variation in mood, a very telling symptom, especially when it’s disclosed spontaneously,” Dr. Ovsiew explained. “The point is, you need to know to ask about it.”

When taking a sleep history, clinicians should be aware of sleep disturbances apart from insomnia and early waking. REM sleep behavior disorder is a condition that should be inquired about. Obstructive sleep apnea is a condition that might not be immediately apparent to the patient, but a bed partner can identify whether a patient has problems breathing throughout the night.

“This is an important condition to uncover for the neuropsychiatrist because it contributes to treatment resistance and depression, and it contributes to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “These patients commonly have mild difficulties with attention and concentration.”

Always ask about head injury in every history, which can be relevant to later onset depression, PTSD, and cognitive impairment. Every head injury follows a trajectory of retrograde amnesia and altered state of consciousness (including coma), followed by a period of posttraumatic amnesia. Duration of these states can be used to assess the severity of brain injury, but the 15-point Glasgow Coma Scale is another way to assess injury severity, Dr. Ovsiew explained.

However, the two do not always overlap, he noted. “Someone may have a Glasgow Coma Scale score that is 9-12, predicting moderate brain injury, but they may have a short duration of amnesia. These don’t always follow the same path. There are many different ways of classifying how severe the brain injury is.”

Keep probes brief, straightforward

Cognitive exams of patients with suspected psychiatric disorders should be simple, easy to administer and focused on a single domain of cognition. “Probes should be brief. They should not require specialized equipment. The Purdue Pegboard Test might be a great neuropsychological instrument, but very few of us carry a pegboard around in our medical bags,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

The probe administered should also be accessible to the patient. The serial sevens clinical test, where a patient is asked to repeatedly subtract 7 from 100, is only effective at testing concentration if the patient is capable of completing the test. “There are going to be patients who can’t do the task, but it’s not because of concentration failure, it’s because of subtraction failure,” he said.

When assessing attention, effective tasks include having the patient perform the digit span test forward and backward, count backward from 20 to 1, listing the months of the year in reverse, and performing the Mental Alternation Test. However, Dr. Ovsiew explained there may be some barriers for patients in completing these tasks. “The person may be aphasic and not know the alphabet. The person may have English as a second language and not be skilled at giving the alphabet in English. In some cases, you may want to check and not assume that the patient can count and does know the alphabet.”

In assessing language, listen for aphasic abnormalities. “The patient, of course, is speaking throughout the interview, but you need to take a moment to listen for prosody, to listen to rate of speech, to listen for paraphasic errors or word-finding problems,” Dr. Ovsiew said. Any abnormalities should be probed further through confrontation naming tasks, which can be done in person and with some success through video, but not by phone. Naming to definition (“What do you call the part of a shirt that covers the arm?”) is one way of administering the test over the phone.

Visuospatial function can be assessed by clock drawing but also carries problems. Patients who do not plan their clock before beginning to draw, for example, may have an executive function problem instead of a visuospatial problem, Dr. Ovsiew noted. Patients in whom a clinician suspects hemineglect should be given a visual search task or line by section task. “I like doing clock drawing. It’s a nice screening test. It’s becoming, I think, less useful as people count on digital clocks and have trouble even imagining what an analog clock looks like.”

An approach that is better suited to in-person assessment, but also works by video, is the Poppelreuter figure visual perceptual function test, which is a prompt for the patient that involves common household items overlaying one another “in atypical positions and atypical configurations” where the patient is instructed to describe the items they see on the card. Another approach that works over video is the interlocking finger test, where the patient is asked to copy the hand positions made by the clinician.

Dr. Ovsiew admitted that visuospatial function is nearly impossible to assess over the phone. Asking topographical questions (“If you’re driving from Chicago to Los Angeles, is the Pacific Ocean in front of you, behind you, to your left, or to your right?”) may help judge visuospatial function, but this relies on the patient having the topographic knowledge to answer the questions. Some patients who are topographically disoriented can’t do them at all,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Bedside neuropsychiatry assesses encoding of a memory, its retention and its retrieval as well as verbal and visual cues. Each one of these aspects of memory can be impaired on its own and should be explored separately, Dr. Ovsiew explained. “Neuropsychiatric clinicians have a rough-and-ready, seat-of-the-pants way of approaching this that wouldn’t pass muster if you’re a psychologist, but is the best we can do at the bedside.”

To test retrieval and retention, the Three Words–Three Shapes test works well in person, with some difficulty by video, and is not possible to administer over the phone. In lieu of that test, giving the patient a simple word list and asking them to repeat the list in order. Using the word list, “these different stages of memory function can be parsed out pretty well at the bedside or chairside, and even by the phone. Figuring out where the memory failure is diagnostically important,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Executive function, which involves activation, planning, sequencing, maintaining, self-monitoring, and flexible employment of action and attention, is “complicated to evaluate because there are multiple aspects of executive function, multiple deficits that can be seen with executive dysfunction, and they don’t all correlate with each other.”

Within executive function evaluation, the Mental Alternation Test can assess working memory, motor sequencing can be assessed through the ring/fist, fist/edge/palm, alternating fist, and rampart tests. The Go/No-Go test can be used to assess response inhibition. For effortful retrieval evaluation, spontaneous word-list generation – such as thinking of all the items one can buy at a supermarket– can test category fluency, while a task to name all the words starting with a certain letter can assess letter stimulus.

Executive function “is of crucial importance in the neuropsychiatric evaluation because it’s strongly correlated with how well the person functions outside the office,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Ovsiew reported relationships with Wolters Kluwer Health in the form of consulting, receiving royalty payments, and related activities.

Patients have often been labeled as “poor historians” if they are not able to recollect their own medical history, whether through illness or difficulties in communication. But Fred Ovsiew, MD, speaking at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sees that label as an excuse on the part of the clinician.

“I strongly advise you to drop that phrase from your vocabulary if you do use it, because the patient is not the historian. The doctor, the clinician is the historian,” Dr. Ovsiew said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. “It is the clinician’s job to put the story together using the account by the patient as one source, but [also] interviewing a collateral informant and/or reviewing records, which is necessary in almost every case of a neuropsychiatric illness.”

Rather, clinicians taking history at the bedside should focus on why the patients cannot give a narrative account of their illness. Patients can have narrative incapacity on a psychogenic basis, such as in patients with conversion or somatoform disorder, he explained. “I think this is a result of the narrative incapacity that develops in people who have had trauma or adverse experiences in childhood and insecure attachment. This is shown on the adult attachment interview as a disorganized account of their childhoods.”

Other patients might not be able to recount their medical history because they are amnestic, which leaves their account vague because of a lack of access to information. “It may be frozen in time in the sense that, up to a certain point in their life, they can recount the history,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “But in recent years, their account becomes vague.”

Patients with right hemisphere lesions might not know that their account has incongruity and is implausible, while patients with dorsolateral prefrontal lesions might be aspontaneous, use few words to describe their situation, and have poor insight. Those with ventromedial prefrontal lesions can be impulsive and have poor insight, not considering alternative possibilities, Dr. Ovsiew noted.

Asking open-ended questions of the patient is the first step to identifying any potential narrative incapacity, followed by a detailed medical history by the clinician. When taking a medical history, try avoiding what Dr. Ovsiew calls the “anything like that?” problem, where a clinician asks a question about a cluster of symptoms that would make sense to a doctor, but not a patient. For example, a doctor might ask whether a patient is experiencing “chest pain or leg swelling – anything like that?” because he or she knows what those symptoms have in common, but the patient might not know the relationship between those symptoms. “You can’t count on the patient to tell you all the relevant information,” he said. “You have to know what to ask about.”

“Patients with brain disease have subtle personality changes, sometimes more obvious personality changes. These need to be inquired about,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “The patient with apathy has reduced negative as well as positive emotions. The patient with depression has reduced positive emotions, but often tells you very clearly about the negative emotions of sadness, guilt. The patient with depression has diurnal variation in mood, a very telling symptom, especially when it’s disclosed spontaneously,” Dr. Ovsiew explained. “The point is, you need to know to ask about it.”

When taking a sleep history, clinicians should be aware of sleep disturbances apart from insomnia and early waking. REM sleep behavior disorder is a condition that should be inquired about. Obstructive sleep apnea is a condition that might not be immediately apparent to the patient, but a bed partner can identify whether a patient has problems breathing throughout the night.

“This is an important condition to uncover for the neuropsychiatrist because it contributes to treatment resistance and depression, and it contributes to cognitive impairment,” Dr. Ovsiew said. “These patients commonly have mild difficulties with attention and concentration.”

Always ask about head injury in every history, which can be relevant to later onset depression, PTSD, and cognitive impairment. Every head injury follows a trajectory of retrograde amnesia and altered state of consciousness (including coma), followed by a period of posttraumatic amnesia. Duration of these states can be used to assess the severity of brain injury, but the 15-point Glasgow Coma Scale is another way to assess injury severity, Dr. Ovsiew explained.

However, the two do not always overlap, he noted. “Someone may have a Glasgow Coma Scale score that is 9-12, predicting moderate brain injury, but they may have a short duration of amnesia. These don’t always follow the same path. There are many different ways of classifying how severe the brain injury is.”

Keep probes brief, straightforward

Cognitive exams of patients with suspected psychiatric disorders should be simple, easy to administer and focused on a single domain of cognition. “Probes should be brief. They should not require specialized equipment. The Purdue Pegboard Test might be a great neuropsychological instrument, but very few of us carry a pegboard around in our medical bags,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

The probe administered should also be accessible to the patient. The serial sevens clinical test, where a patient is asked to repeatedly subtract 7 from 100, is only effective at testing concentration if the patient is capable of completing the test. “There are going to be patients who can’t do the task, but it’s not because of concentration failure, it’s because of subtraction failure,” he said.

When assessing attention, effective tasks include having the patient perform the digit span test forward and backward, count backward from 20 to 1, listing the months of the year in reverse, and performing the Mental Alternation Test. However, Dr. Ovsiew explained there may be some barriers for patients in completing these tasks. “The person may be aphasic and not know the alphabet. The person may have English as a second language and not be skilled at giving the alphabet in English. In some cases, you may want to check and not assume that the patient can count and does know the alphabet.”

In assessing language, listen for aphasic abnormalities. “The patient, of course, is speaking throughout the interview, but you need to take a moment to listen for prosody, to listen to rate of speech, to listen for paraphasic errors or word-finding problems,” Dr. Ovsiew said. Any abnormalities should be probed further through confrontation naming tasks, which can be done in person and with some success through video, but not by phone. Naming to definition (“What do you call the part of a shirt that covers the arm?”) is one way of administering the test over the phone.

Visuospatial function can be assessed by clock drawing but also carries problems. Patients who do not plan their clock before beginning to draw, for example, may have an executive function problem instead of a visuospatial problem, Dr. Ovsiew noted. Patients in whom a clinician suspects hemineglect should be given a visual search task or line by section task. “I like doing clock drawing. It’s a nice screening test. It’s becoming, I think, less useful as people count on digital clocks and have trouble even imagining what an analog clock looks like.”

An approach that is better suited to in-person assessment, but also works by video, is the Poppelreuter figure visual perceptual function test, which is a prompt for the patient that involves common household items overlaying one another “in atypical positions and atypical configurations” where the patient is instructed to describe the items they see on the card. Another approach that works over video is the interlocking finger test, where the patient is asked to copy the hand positions made by the clinician.

Dr. Ovsiew admitted that visuospatial function is nearly impossible to assess over the phone. Asking topographical questions (“If you’re driving from Chicago to Los Angeles, is the Pacific Ocean in front of you, behind you, to your left, or to your right?”) may help judge visuospatial function, but this relies on the patient having the topographic knowledge to answer the questions. Some patients who are topographically disoriented can’t do them at all,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Bedside neuropsychiatry assesses encoding of a memory, its retention and its retrieval as well as verbal and visual cues. Each one of these aspects of memory can be impaired on its own and should be explored separately, Dr. Ovsiew explained. “Neuropsychiatric clinicians have a rough-and-ready, seat-of-the-pants way of approaching this that wouldn’t pass muster if you’re a psychologist, but is the best we can do at the bedside.”

To test retrieval and retention, the Three Words–Three Shapes test works well in person, with some difficulty by video, and is not possible to administer over the phone. In lieu of that test, giving the patient a simple word list and asking them to repeat the list in order. Using the word list, “these different stages of memory function can be parsed out pretty well at the bedside or chairside, and even by the phone. Figuring out where the memory failure is diagnostically important,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Executive function, which involves activation, planning, sequencing, maintaining, self-monitoring, and flexible employment of action and attention, is “complicated to evaluate because there are multiple aspects of executive function, multiple deficits that can be seen with executive dysfunction, and they don’t all correlate with each other.”

Within executive function evaluation, the Mental Alternation Test can assess working memory, motor sequencing can be assessed through the ring/fist, fist/edge/palm, alternating fist, and rampart tests. The Go/No-Go test can be used to assess response inhibition. For effortful retrieval evaluation, spontaneous word-list generation – such as thinking of all the items one can buy at a supermarket– can test category fluency, while a task to name all the words starting with a certain letter can assess letter stimulus.

Executive function “is of crucial importance in the neuropsychiatric evaluation because it’s strongly correlated with how well the person functions outside the office,” Dr. Ovsiew said.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Ovsiew reported relationships with Wolters Kluwer Health in the form of consulting, receiving royalty payments, and related activities.

FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2020

More evidence links gum disease and dementia risk

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

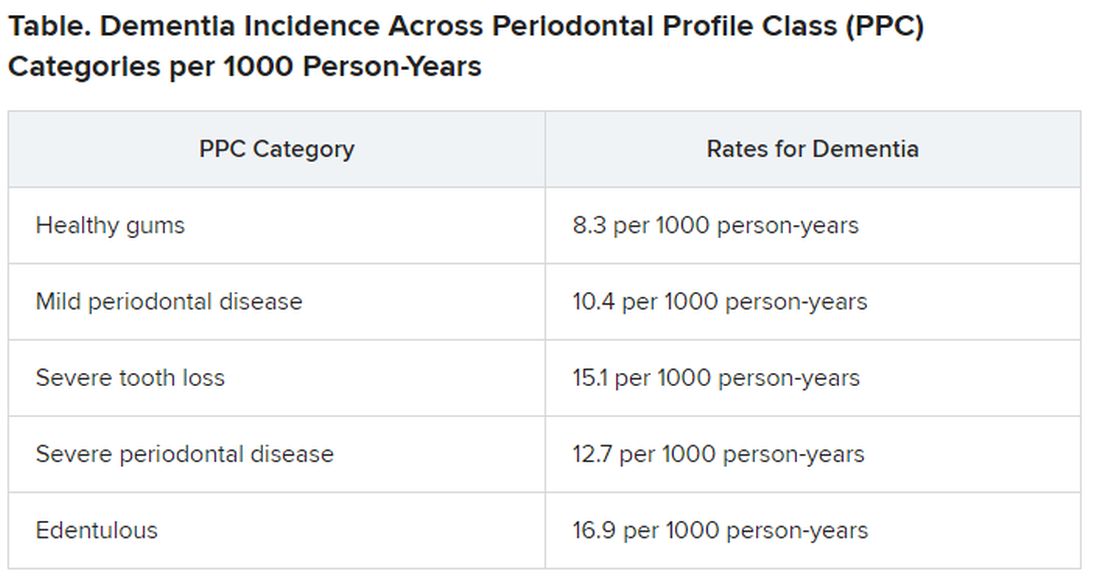

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

especially in those with severe gum inflammation and edentulism, new research suggests.

Over a 20-year period, investigators prospectively followed more than 8,000 individuals aged around 63 years who did not have cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline, grouping them based on the extent and severity of their periodontal disease and number of lost teeth.

Results showed that 14% of participants with healthy gums and all their teeth at baseline developed dementia, compared with 18% of those with mild periodontal disease and 22% who had severe periodontal disease. The highest percentage (23%) of participants who developed dementia was found in those who were edentulous.

After accounting for comorbidities that might affect dementia risk, edentulous participants had a 20% higher risk for developing MCI or dementia, compared with the healthy group.

Because the study was observational, “we don’t have knowledge of causality so we cannot state that if you treat periodontal disease you can prevent or treat dementia,” said lead author Ryan T. Demmer, PhD, MPH, associate professor, division of epidemiology and community health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. However, “the take-home message from this paper is that it further supports the possibility that oral infections could be a risk factor for dementia.”

The study was published online July 29 in Neurology.

The ARIC trial

Prior studies have “described the interrelation of tooth loss or periodontal disease and cognitive outcomes, although many reports were cross-sectional or case-control … and often lacked robust confounder adjustment,” the investigators noted. Additionally, lack of longitudinal data impedes the “potential for baseline periodontal status to predict incident MCI.”

To explore the associations between periodontal status and incident MCI and dementia, the researchers studied participants in the ARIC study, a community-based longitudinal cohort consisting of 15,792 predominantly Black and White participants aged 45-64 years. The current analysis included 8,275 individuals (55% women; 21% black; mean age, 63 years) who at baseline did not meet criteria for dementia or MCI.

A full-mouth periodontal examination was conducted at baseline and participants were categorized according to the severity and extent of gingival inflammation and tooth attachment loss based on the Periodontal Profile Class (PPC) seven-category model. Potential confounding variables included age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking status, oral hygiene and access to care, plasma lipid levels, APOE genotype, body mass index, blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure.

Based on PPC categorization, 22% of the patients had healthy gums, 12% had mild periodontal disease, 8% had a high gingival inflammation index, and 12% had posterior disease (with 6% having severe disease). In addition, 9% had tooth loss, 11% had severe tooth loss, and 20% were edentulous.

Infection hypothesis

Results showed that participants with worse periodontal status were more likely to have risk factors for vascular disease and dementia, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. During median follow-up of 18.4 years, 19% of participants overall (n = 1,569) developed dementia, translating into 11.8 cases per 1,000 person-years. There were notable differences between the PPC categories in rates of incident dementia, with edentulous participants at twice the risk for developing dementia, compared with those who had healthy gums.

For participants with severe PPC, including severe tooth loss and severe disease, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio for incident dementia was 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.47) versus those who were periodontally healthy. For participants with edentulism, the HR was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.48). The adjusted risk ratios for the combined dementia/MCI outcome among participants with mild to intermediate PPC, severe PPC, or edentulism versus the periodontal healthy group were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.00-1.48), 1.15 (95% CI, 0.88-1.51), and 1.90 (95% CI, 1.40-2.58), respectively.

These findings were most pronounced among younger (median age at dental exam, younger than 62) versus older (62 years and older) participants (P = .02). Severe disease or total tooth loss were associated with an approximately 20% greater dementia incidence during the follow-up period, compared with healthy gums.

The investigators noted that the findings were “generally consistent” when considering the combined outcome of MCI and dementia. However, they noted that the association between edentulism and MCI was “markedly stronger,” with an approximate 100% increase in MCI or MCI plus dementia.

The association between periodontal disease and MCI or dementia “is rooted in the infection hypothesis, meaning adverse microbial exposures in the mucosal surfaces of the mouth, especially the subgingival space,” Dr. Demmer said. “One notion is that there could somehow be a direct infection of the brain with oral organisms, which posits that the oral organism could travel to the brain, colonize there, and cause damage that impairs cognition.”

Another possible mechanism is that chronic systemic inflammation in response to oral infections can eventually lead to vascular disease which, in turn, is a known risk factor for future dementia, he noted.

“Brush and floss”

Commenting on the research findings, James M. Noble, MD, associate professor of neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, called the study “well characterized both by whole-mouth assessments and cognitive assessments performed in a standardized manner.” Moreover, “the study was sufficiently sized to allow for exploration of age and suggests that oral health may be a more important factor earlier in the course of aging, in late adulthood,” said Dr. Noble, who was not involved with the research.

The study also “makes an important contribution to this field through a rigorously followed cohort and robust design for both periodontal predictor and cognitive outcome assessments,” he said, noting that, “as always, the take-home message is ‘brush and floss.’

“Although we don’t know if treating periodontal disease can help treat dementia, this study suggests that we have to pay attention to good oral hygiene and make referrals to dentists when appropriate,” Dr. Demmer added.

The ARIC trial is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Demmer, the study coauthors, and Dr. Noble have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Are aging physicians a burden?

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.