User login

Similar brain atrophy in obesity and Alzheimer’s disease

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Can a ‘smart’ skin patch detect early neurodegenerative diseases?

A new “smart patch” composed of microneedles that can detect proinflammatory markers via simulated skin interstitial fluid (ISF) may help diagnose neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease very early on.

Originally developed to deliver medications and vaccines via the skin in a minimally invasive manner, the microneedle arrays were fitted with molecular sensors that, when placed on the skin, detect neuroinflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-6 in as little as 6 minutes.

The literature suggests that these biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease are present years before patients become symptomatic, said study investigator Sanjiv Sharma, PhD.

“Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are [characterized by] progressive loss in nerve cell and brain cells, which leads to memory problems and a loss of mental ability. That is why early diagnosis is key to preventing the loss of brain tissue in dementia, which can go undetected for years,” added Dr. Sharma, who is a lecturer in medical engineering at Swansea (Wales) University.

Dr. Sharma developed the patch with scientists at the Polytechnic of Porto (Portugal) School of Engineering in Portugal. In 2022, they designed, and are currently testing, a microneedle patch that will deliver the COVID vaccine.

The investigators describe their research on the patch’s ability to detect IL-6 in an article published in ACS Omega.

At-home diagnosis?

“The skin is the largest organ in the body – it contains more skin interstitial fluid than the total blood volume,” Dr. Sharma noted. “This fluid is an ultrafiltrate of blood and holds biomarkers that complement other biofluids, such as sweat, saliva, and urine. It can be sampled in a minimally invasive manner and used either for point-of-care testing or real-time using microneedle devices.”

Dr. Sharma and associates tested the microneedle patch in artificial ISF that contained the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. They found that the patch accurately detected IL-6 concentrations as low as 1 pg/mL in the fabricated ISF solution.

“In general, the transdermal sensor presented here showed simplicity in designing, short measuring time, high accuracy, and low detection limit. This approach seems a successful tool for the screening of inflammatory biomarkers in point of care testing wherein the skin acts as a window to the body,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Sharma noted that early detection of neurodegenerative diseases is crucial, as once symptoms appear, the disease may have already progressed significantly, and meaningful intervention is challenging.

The device has yet to be tested in humans, which is the next step, said Dr. Sharma.

“We will have to test the hypothesis through extensive preclinical and clinical studies to determine if bloodless, transdermal (skin) diagnostics can offer a cost-effective device that could allow testing in simpler settings such as a clinician’s practice or even home settings,” he noted.

Early days

Commenting on the research, David K. Simon, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said it is “a promising step regarding validation of a potentially beneficial method for rapidly and accurately measuring IL-6.”

However, he added, “many additional steps are needed to validate the method in actual human skin and to determine whether or not measuring these biomarkers in skin will be useful in studies of neurodegenerative diseases.”

He noted that one study limitation is that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are highly nonspecific, and levels are elevated in various diseases associated with inflammation.

“It is highly unlikely that measuring IL-6 will be useful as a diagnostic tool. However, it does have potential as a biomarker for measuring the impact of treatments aimed at reducing inflammation. As the authors point out, it’s more likely that clinicians will require a panel of biomarkers rather than only measuring IL-6,” he said.

The study was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new “smart patch” composed of microneedles that can detect proinflammatory markers via simulated skin interstitial fluid (ISF) may help diagnose neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease very early on.

Originally developed to deliver medications and vaccines via the skin in a minimally invasive manner, the microneedle arrays were fitted with molecular sensors that, when placed on the skin, detect neuroinflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-6 in as little as 6 minutes.

The literature suggests that these biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease are present years before patients become symptomatic, said study investigator Sanjiv Sharma, PhD.

“Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are [characterized by] progressive loss in nerve cell and brain cells, which leads to memory problems and a loss of mental ability. That is why early diagnosis is key to preventing the loss of brain tissue in dementia, which can go undetected for years,” added Dr. Sharma, who is a lecturer in medical engineering at Swansea (Wales) University.

Dr. Sharma developed the patch with scientists at the Polytechnic of Porto (Portugal) School of Engineering in Portugal. In 2022, they designed, and are currently testing, a microneedle patch that will deliver the COVID vaccine.

The investigators describe their research on the patch’s ability to detect IL-6 in an article published in ACS Omega.

At-home diagnosis?

“The skin is the largest organ in the body – it contains more skin interstitial fluid than the total blood volume,” Dr. Sharma noted. “This fluid is an ultrafiltrate of blood and holds biomarkers that complement other biofluids, such as sweat, saliva, and urine. It can be sampled in a minimally invasive manner and used either for point-of-care testing or real-time using microneedle devices.”

Dr. Sharma and associates tested the microneedle patch in artificial ISF that contained the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. They found that the patch accurately detected IL-6 concentrations as low as 1 pg/mL in the fabricated ISF solution.

“In general, the transdermal sensor presented here showed simplicity in designing, short measuring time, high accuracy, and low detection limit. This approach seems a successful tool for the screening of inflammatory biomarkers in point of care testing wherein the skin acts as a window to the body,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Sharma noted that early detection of neurodegenerative diseases is crucial, as once symptoms appear, the disease may have already progressed significantly, and meaningful intervention is challenging.

The device has yet to be tested in humans, which is the next step, said Dr. Sharma.

“We will have to test the hypothesis through extensive preclinical and clinical studies to determine if bloodless, transdermal (skin) diagnostics can offer a cost-effective device that could allow testing in simpler settings such as a clinician’s practice or even home settings,” he noted.

Early days

Commenting on the research, David K. Simon, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said it is “a promising step regarding validation of a potentially beneficial method for rapidly and accurately measuring IL-6.”

However, he added, “many additional steps are needed to validate the method in actual human skin and to determine whether or not measuring these biomarkers in skin will be useful in studies of neurodegenerative diseases.”

He noted that one study limitation is that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are highly nonspecific, and levels are elevated in various diseases associated with inflammation.

“It is highly unlikely that measuring IL-6 will be useful as a diagnostic tool. However, it does have potential as a biomarker for measuring the impact of treatments aimed at reducing inflammation. As the authors point out, it’s more likely that clinicians will require a panel of biomarkers rather than only measuring IL-6,” he said.

The study was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new “smart patch” composed of microneedles that can detect proinflammatory markers via simulated skin interstitial fluid (ISF) may help diagnose neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease very early on.

Originally developed to deliver medications and vaccines via the skin in a minimally invasive manner, the microneedle arrays were fitted with molecular sensors that, when placed on the skin, detect neuroinflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-6 in as little as 6 minutes.

The literature suggests that these biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease are present years before patients become symptomatic, said study investigator Sanjiv Sharma, PhD.

“Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are [characterized by] progressive loss in nerve cell and brain cells, which leads to memory problems and a loss of mental ability. That is why early diagnosis is key to preventing the loss of brain tissue in dementia, which can go undetected for years,” added Dr. Sharma, who is a lecturer in medical engineering at Swansea (Wales) University.

Dr. Sharma developed the patch with scientists at the Polytechnic of Porto (Portugal) School of Engineering in Portugal. In 2022, they designed, and are currently testing, a microneedle patch that will deliver the COVID vaccine.

The investigators describe their research on the patch’s ability to detect IL-6 in an article published in ACS Omega.

At-home diagnosis?

“The skin is the largest organ in the body – it contains more skin interstitial fluid than the total blood volume,” Dr. Sharma noted. “This fluid is an ultrafiltrate of blood and holds biomarkers that complement other biofluids, such as sweat, saliva, and urine. It can be sampled in a minimally invasive manner and used either for point-of-care testing or real-time using microneedle devices.”

Dr. Sharma and associates tested the microneedle patch in artificial ISF that contained the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. They found that the patch accurately detected IL-6 concentrations as low as 1 pg/mL in the fabricated ISF solution.

“In general, the transdermal sensor presented here showed simplicity in designing, short measuring time, high accuracy, and low detection limit. This approach seems a successful tool for the screening of inflammatory biomarkers in point of care testing wherein the skin acts as a window to the body,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Sharma noted that early detection of neurodegenerative diseases is crucial, as once symptoms appear, the disease may have already progressed significantly, and meaningful intervention is challenging.

The device has yet to be tested in humans, which is the next step, said Dr. Sharma.

“We will have to test the hypothesis through extensive preclinical and clinical studies to determine if bloodless, transdermal (skin) diagnostics can offer a cost-effective device that could allow testing in simpler settings such as a clinician’s practice or even home settings,” he noted.

Early days

Commenting on the research, David K. Simon, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said it is “a promising step regarding validation of a potentially beneficial method for rapidly and accurately measuring IL-6.”

However, he added, “many additional steps are needed to validate the method in actual human skin and to determine whether or not measuring these biomarkers in skin will be useful in studies of neurodegenerative diseases.”

He noted that one study limitation is that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are highly nonspecific, and levels are elevated in various diseases associated with inflammation.

“It is highly unlikely that measuring IL-6 will be useful as a diagnostic tool. However, it does have potential as a biomarker for measuring the impact of treatments aimed at reducing inflammation. As the authors point out, it’s more likely that clinicians will require a panel of biomarkers rather than only measuring IL-6,” he said.

The study was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACS OMEGA

Six healthy lifestyle habits linked to slowed memory decline

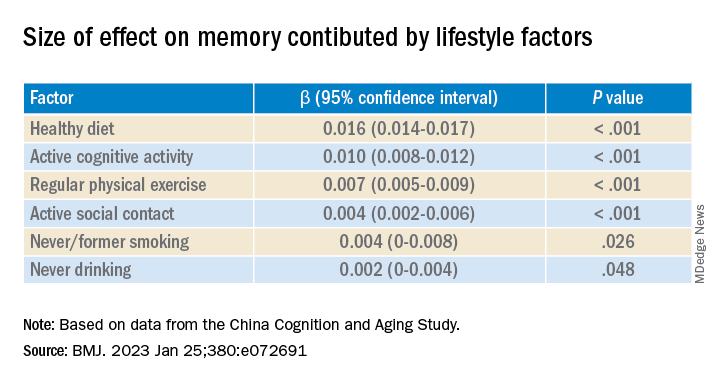

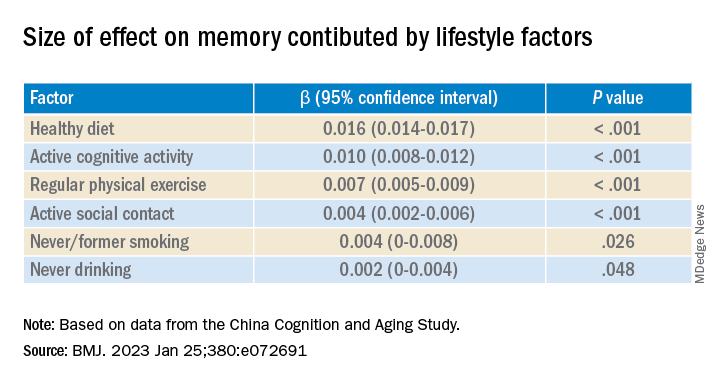

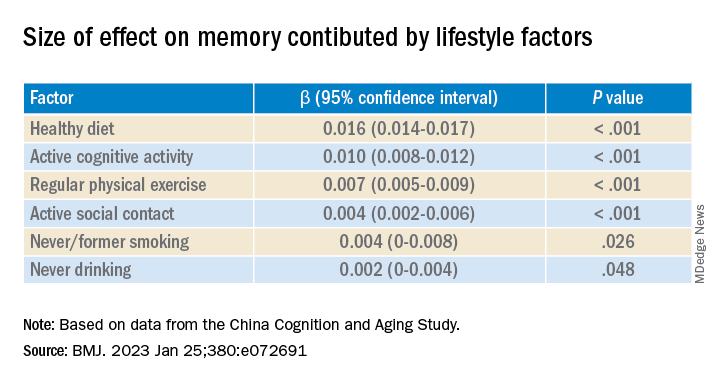

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

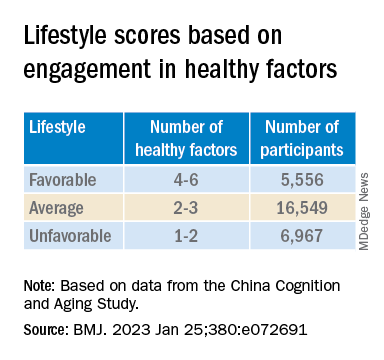

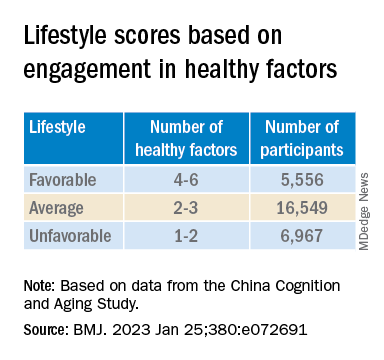

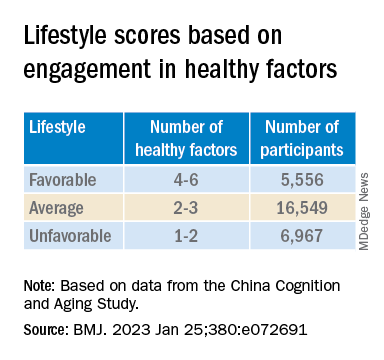

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BMJ

Nine more minutes a day of vigorous exercise tied to better cognition

such as running and cycling, plays in brain health.

“Even minor differences in daily behavior appeared meaningful for cognition in this study,” researcher John J. Mitchell, MSci and PhD candidate, Medical Research Council, London, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Research gap

Previous research has linked physical activity (PA) with increased cognitive reserve, which delays the onset of cognitive decline in later life. But disentangling the most important components of PA for cognition – such as intensity and volume – has not been well researched.

Previous studies didn’t capture sleep time, which typically takes up the largest component of the day. Sleep is “acutely relevant” when examining cognition, the investigators noted.

In addition, studies in this area often focus on just one or two activity components of the day, which “neglects the growing awareness” that movements “are all tightly interlinked,” said Mr. Mitchell.

The new study included 4,481 participants in the British Cohort Study who were born in 1970 across England, Scotland, and Wales. The participants were followed throughout childhood and adulthood.

The median age of the participants was 47 years, and they were predominantly White, female (52%), married (66%), and well educated. Most were occasional or nonrisky alcohol consumers, and half had never smoked.

The researchers collected biometric measurements and health, demographic, and lifestyle information. Participants wore a thigh-mounted accelerometer at least 7 consecutive hours a day for up to 7 days to track PA, sedentary behavior (SB), and sleep time.

The device used in the study could detect subtle movements as well as speed of accelerations, said Mr. Mitchell. “From this, we can distinguish MVPA from slow walking, standing, and sitting. It’s the current best practice for detecting the more subtle movements we make, such as brisk walking and stair climbing, beyond just ‘exercise,’ “ he added.

Light intensity PA (LIPA) describes movement such as walking and moving around the house or office, while MVPA includes activities such as brisk walking and running that accelerate the heart rate. SB, defined as time spent sitting or lying, is distinguished from standing by the thigh inclination.

On an average day, the cohort spent 51 minutes in MVPA; 5 hours, 42 minutes in LIPA; 9 hours, 16 minutes in SB; and 8 hours, 11 minutes sleeping.

Researchers calculated an overall global score for verbal memory and executive function.

The study used “compositional data analysis,” a statistical method that can examine the associations of cognition and PA in the context of all components of daily movement.

The analysis revealed a positive association between MVPA and cognition relative to all other behaviors, after adjustment for sociodemographic factors that included sex, age, education, and marital status. But the relationship lessened after further adjustment for health status – for example, cardiovascular disease or disability – and lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption and smoking status.

SB relative to all other movements remained positively associated with cognition after full adjustment. This, the authors speculated, may reflect engagement in cognitively stimulating activities such as reading.

To better understand the associations, the researchers used a statistical method to reallocate time in the cohort’s average day from one activity component to another.

“We held two of the components static but moved time between the other two and monitored the theoretical ramifications of that change for cognition,” said Mr. Mitchell.

Real cognitive change

There was a 1.31% improvement in cognition ranking compared to the sample average after replacing 9 minutes of sedentary activity with MVPA (1.31; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.09-2.50). There was a 1.27% improvement after replacing 7 minutes of LIPA with MVPA, and a 1.2% improvement after replacing 7 minutes of sleep with MVPA.

Individuals might move up from about the 50th percentile to the 51st or 52nd percentile after just 9 minutes of more moderate to vigorous movement in place of sitting, said Mr. Mitchell. “This highlights how even very modest differences in people’s daily movement – less than 10 minutes – is linked to quite real changes in our cognitive health.”

The impact of physical activity appeared greatest on working memory and mental processes, such as planning and organization.

On the other hand, cognition declined by 1%-2% after replacing MVPA with 8 minutes of SB, 6 minutes of LIPA, or 7 minutes of sleep.

The activity tracking device couldn’t determine how well participants slept, which is “a clear limitation” of the study, said Mr. Mitchell. “We have to be cautious when trying to interpret our findings surrounding sleep.”

Another limitation is that despite a large sample size, people of color were underrepresented, limiting the generalizability of the findings. As well, other healthy pursuits – for example, reading – might have contributed to improved cognition.

Important findings

In a comment, Jennifer J. Heisz, PhD, associate professor and Canada research chair in brain health and aging, department of kinesiology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said the findings from the study are important.

“Through the statistical modelling, the authors demonstrate that swapping just 9 minutes of sedentary behavior with moderate to vigorous physical activity, such as a brisk walk or bike ride, was associated with an increase in cognition.”

She added that this seemed to be especially true for people who sit while at work.

The findings “confer with the growing consensus” that some exercise is better than none when it comes to brain health, said Dr. Heisz.

“Clinicians should encourage their patients to add a brisk, 10-minute walk to their daily routine and break up prolonged sitting with short movement breaks.”

She noted the study was cross-sectional, “so it is not possible to infer causation.”

The study received funding from the Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundation. Mr. Mitchell and Dr. Heisz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

such as running and cycling, plays in brain health.

“Even minor differences in daily behavior appeared meaningful for cognition in this study,” researcher John J. Mitchell, MSci and PhD candidate, Medical Research Council, London, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Research gap

Previous research has linked physical activity (PA) with increased cognitive reserve, which delays the onset of cognitive decline in later life. But disentangling the most important components of PA for cognition – such as intensity and volume – has not been well researched.

Previous studies didn’t capture sleep time, which typically takes up the largest component of the day. Sleep is “acutely relevant” when examining cognition, the investigators noted.

In addition, studies in this area often focus on just one or two activity components of the day, which “neglects the growing awareness” that movements “are all tightly interlinked,” said Mr. Mitchell.

The new study included 4,481 participants in the British Cohort Study who were born in 1970 across England, Scotland, and Wales. The participants were followed throughout childhood and adulthood.

The median age of the participants was 47 years, and they were predominantly White, female (52%), married (66%), and well educated. Most were occasional or nonrisky alcohol consumers, and half had never smoked.

The researchers collected biometric measurements and health, demographic, and lifestyle information. Participants wore a thigh-mounted accelerometer at least 7 consecutive hours a day for up to 7 days to track PA, sedentary behavior (SB), and sleep time.

The device used in the study could detect subtle movements as well as speed of accelerations, said Mr. Mitchell. “From this, we can distinguish MVPA from slow walking, standing, and sitting. It’s the current best practice for detecting the more subtle movements we make, such as brisk walking and stair climbing, beyond just ‘exercise,’ “ he added.

Light intensity PA (LIPA) describes movement such as walking and moving around the house or office, while MVPA includes activities such as brisk walking and running that accelerate the heart rate. SB, defined as time spent sitting or lying, is distinguished from standing by the thigh inclination.

On an average day, the cohort spent 51 minutes in MVPA; 5 hours, 42 minutes in LIPA; 9 hours, 16 minutes in SB; and 8 hours, 11 minutes sleeping.

Researchers calculated an overall global score for verbal memory and executive function.

The study used “compositional data analysis,” a statistical method that can examine the associations of cognition and PA in the context of all components of daily movement.

The analysis revealed a positive association between MVPA and cognition relative to all other behaviors, after adjustment for sociodemographic factors that included sex, age, education, and marital status. But the relationship lessened after further adjustment for health status – for example, cardiovascular disease or disability – and lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption and smoking status.

SB relative to all other movements remained positively associated with cognition after full adjustment. This, the authors speculated, may reflect engagement in cognitively stimulating activities such as reading.

To better understand the associations, the researchers used a statistical method to reallocate time in the cohort’s average day from one activity component to another.

“We held two of the components static but moved time between the other two and monitored the theoretical ramifications of that change for cognition,” said Mr. Mitchell.

Real cognitive change

There was a 1.31% improvement in cognition ranking compared to the sample average after replacing 9 minutes of sedentary activity with MVPA (1.31; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.09-2.50). There was a 1.27% improvement after replacing 7 minutes of LIPA with MVPA, and a 1.2% improvement after replacing 7 minutes of sleep with MVPA.

Individuals might move up from about the 50th percentile to the 51st or 52nd percentile after just 9 minutes of more moderate to vigorous movement in place of sitting, said Mr. Mitchell. “This highlights how even very modest differences in people’s daily movement – less than 10 minutes – is linked to quite real changes in our cognitive health.”

The impact of physical activity appeared greatest on working memory and mental processes, such as planning and organization.

On the other hand, cognition declined by 1%-2% after replacing MVPA with 8 minutes of SB, 6 minutes of LIPA, or 7 minutes of sleep.

The activity tracking device couldn’t determine how well participants slept, which is “a clear limitation” of the study, said Mr. Mitchell. “We have to be cautious when trying to interpret our findings surrounding sleep.”

Another limitation is that despite a large sample size, people of color were underrepresented, limiting the generalizability of the findings. As well, other healthy pursuits – for example, reading – might have contributed to improved cognition.

Important findings

In a comment, Jennifer J. Heisz, PhD, associate professor and Canada research chair in brain health and aging, department of kinesiology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said the findings from the study are important.

“Through the statistical modelling, the authors demonstrate that swapping just 9 minutes of sedentary behavior with moderate to vigorous physical activity, such as a brisk walk or bike ride, was associated with an increase in cognition.”

She added that this seemed to be especially true for people who sit while at work.

The findings “confer with the growing consensus” that some exercise is better than none when it comes to brain health, said Dr. Heisz.

“Clinicians should encourage their patients to add a brisk, 10-minute walk to their daily routine and break up prolonged sitting with short movement breaks.”

She noted the study was cross-sectional, “so it is not possible to infer causation.”

The study received funding from the Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundation. Mr. Mitchell and Dr. Heisz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

such as running and cycling, plays in brain health.

“Even minor differences in daily behavior appeared meaningful for cognition in this study,” researcher John J. Mitchell, MSci and PhD candidate, Medical Research Council, London, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Research gap

Previous research has linked physical activity (PA) with increased cognitive reserve, which delays the onset of cognitive decline in later life. But disentangling the most important components of PA for cognition – such as intensity and volume – has not been well researched.

Previous studies didn’t capture sleep time, which typically takes up the largest component of the day. Sleep is “acutely relevant” when examining cognition, the investigators noted.

In addition, studies in this area often focus on just one or two activity components of the day, which “neglects the growing awareness” that movements “are all tightly interlinked,” said Mr. Mitchell.

The new study included 4,481 participants in the British Cohort Study who were born in 1970 across England, Scotland, and Wales. The participants were followed throughout childhood and adulthood.

The median age of the participants was 47 years, and they were predominantly White, female (52%), married (66%), and well educated. Most were occasional or nonrisky alcohol consumers, and half had never smoked.

The researchers collected biometric measurements and health, demographic, and lifestyle information. Participants wore a thigh-mounted accelerometer at least 7 consecutive hours a day for up to 7 days to track PA, sedentary behavior (SB), and sleep time.

The device used in the study could detect subtle movements as well as speed of accelerations, said Mr. Mitchell. “From this, we can distinguish MVPA from slow walking, standing, and sitting. It’s the current best practice for detecting the more subtle movements we make, such as brisk walking and stair climbing, beyond just ‘exercise,’ “ he added.

Light intensity PA (LIPA) describes movement such as walking and moving around the house or office, while MVPA includes activities such as brisk walking and running that accelerate the heart rate. SB, defined as time spent sitting or lying, is distinguished from standing by the thigh inclination.

On an average day, the cohort spent 51 minutes in MVPA; 5 hours, 42 minutes in LIPA; 9 hours, 16 minutes in SB; and 8 hours, 11 minutes sleeping.

Researchers calculated an overall global score for verbal memory and executive function.

The study used “compositional data analysis,” a statistical method that can examine the associations of cognition and PA in the context of all components of daily movement.

The analysis revealed a positive association between MVPA and cognition relative to all other behaviors, after adjustment for sociodemographic factors that included sex, age, education, and marital status. But the relationship lessened after further adjustment for health status – for example, cardiovascular disease or disability – and lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption and smoking status.

SB relative to all other movements remained positively associated with cognition after full adjustment. This, the authors speculated, may reflect engagement in cognitively stimulating activities such as reading.

To better understand the associations, the researchers used a statistical method to reallocate time in the cohort’s average day from one activity component to another.

“We held two of the components static but moved time between the other two and monitored the theoretical ramifications of that change for cognition,” said Mr. Mitchell.

Real cognitive change

There was a 1.31% improvement in cognition ranking compared to the sample average after replacing 9 minutes of sedentary activity with MVPA (1.31; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.09-2.50). There was a 1.27% improvement after replacing 7 minutes of LIPA with MVPA, and a 1.2% improvement after replacing 7 minutes of sleep with MVPA.

Individuals might move up from about the 50th percentile to the 51st or 52nd percentile after just 9 minutes of more moderate to vigorous movement in place of sitting, said Mr. Mitchell. “This highlights how even very modest differences in people’s daily movement – less than 10 minutes – is linked to quite real changes in our cognitive health.”

The impact of physical activity appeared greatest on working memory and mental processes, such as planning and organization.

On the other hand, cognition declined by 1%-2% after replacing MVPA with 8 minutes of SB, 6 minutes of LIPA, or 7 minutes of sleep.

The activity tracking device couldn’t determine how well participants slept, which is “a clear limitation” of the study, said Mr. Mitchell. “We have to be cautious when trying to interpret our findings surrounding sleep.”

Another limitation is that despite a large sample size, people of color were underrepresented, limiting the generalizability of the findings. As well, other healthy pursuits – for example, reading – might have contributed to improved cognition.

Important findings

In a comment, Jennifer J. Heisz, PhD, associate professor and Canada research chair in brain health and aging, department of kinesiology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said the findings from the study are important.

“Through the statistical modelling, the authors demonstrate that swapping just 9 minutes of sedentary behavior with moderate to vigorous physical activity, such as a brisk walk or bike ride, was associated with an increase in cognition.”

She added that this seemed to be especially true for people who sit while at work.

The findings “confer with the growing consensus” that some exercise is better than none when it comes to brain health, said Dr. Heisz.

“Clinicians should encourage their patients to add a brisk, 10-minute walk to their daily routine and break up prolonged sitting with short movement breaks.”

She noted the study was cross-sectional, “so it is not possible to infer causation.”

The study received funding from the Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundation. Mr. Mitchell and Dr. Heisz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF EPIDEMIOLOGY AND COMMUNITY HEALTH

Geriatrician advises on use of vitamin D supplementation, lecanemab, and texting for her patients

Vitamin D supplementation and incident fractures

Vitamin D supplementation is a commonly recommended intervention for bone health, but data to support its impact on reducing fracture risk has been variable.

A study in the New England Journal of Medicine by LeBoff and colleagues has garnered much attention since its publication in July 2022.1 In the ancillary study of the Vitamin D and Omega-3-Trial (VITAL), the authors examined the impact of vitamin D supplementation versus placebo on incident fractures. The study found that vitamin D supplementation, as compared with placebo, led to no significant difference in the incidence of total, nonvertebral, and hip fractures in midlife and older adults over the 5-year period of follow-up.

The generalizability of these findings has been raised as a concern as the study does not describe adults at higher risk for fracture. The authors of the study specified in their conclusion that vitamin D supplementation does not reduce fracture risk in “generally healthy midlife and older adults who were not selected for vitamin D deficiency, low bone mass or osteoporosis.”

With a mean participant age of 67 and exclusion of participants with a history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, cirrhosis and other serious illnesses, the study does not reflect the multimorbid older adult population that geriatricians typically care for. Furthermore, efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on fracture risk may be the most impactful in those with osteoporosis and with severe vitamin D deficiency (defined by vitamin D 25[OH]D level less than 12 ng/mL).

In post hoc analyses, there was no significant difference in fracture risk in these subgroups, however the authors acknowledged that the findings may be limited by the small percentage of participants with severe vitamin D deficiency (2.4%) and osteoporosis included in the study (5%).

Lecanemab for mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s dementia

On Jan. 6, 2023, the Food and Drug Administration approved lecanemab, the second-ever disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s dementia following the approval of aducanumab in 2021. Lecanemab is a monoclonal antibody targeting larger amyloid-beta oligomers, which has been shown in vitro to have higher affinity for amyloid-beta, compared with aducanumab. FDA approval followed shortly after the publication of the CLARITY-AD trial, which investigated the effect of lecanemab versus placebo on cognitive decline and burden of amyloid in adults with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s dementia. Over an 18-month period, the study found that participants who received lecanemab, compared with placebo, had a significantly smaller decline in cognition and function, and reduction in amyloid burden on PET CT.2

The clinical significance of these findings, however, is unclear. As noted by an editorial published in the Lancet in 2022, the difference in Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) scale between the treatment and placebo groups was 0.45. On an 18-point scale, prior research has noted that a minimal clinically significance difference of 0.98 is necessary in those with mild cognitive impairment and 1.63 in mild Alzheimer dementia.3

Additionally, the CLARITY-AD trial reported that lecanemab resulted in infusion reactions in 26.4% of participants and brain edema (an amyloid-related imaging abnormality referred to as ARIA-E) in 12.6% of participants. This finding highlights concerns for safety and the need for close monitoring, as well as ongoing implications of economic feasibility and equitable access for all those who qualify for treatment.2

Social isolation and dementia risk

There is growing awareness of the impact of social isolation on health outcomes, particularly among older adults. Prior research has reported that one in four older adults are considered socially isolated and that social isolation increases risk of premature death, dementia, depression, and cardiovascular disease.4

A study by Huang and colleagues is the first nationally representative cohort study examining the association between social isolation and incident dementia for older adults in community dwelling settings. A cohort of 5,022 older adults participating in the National Health and Aging Trends Study was followed from 2011 to 2020. When adjusting for demographic and health factors, including race, level of education, and number of chronic health conditions, socially isolated adults had a greater risk of developing dementia, compared with adults who were not socially isolated (hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.49). Potential mechanisms to explain this association include the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and depression in older adults who are socially isolated, thereby increasing dementia risk.

Decreased cognitive activity/engagement and access to resources such as caregiving and health care may also be linked to the increased risk of dementia in socially isolated older adults.5

Another observational cohort study from the National Health and Aging Trends Study investigated whether access and use of technology can lower the risk of social isolation. The study found that older adults who used email or text messaging had a lower risk of social isolation than older adults who did not use technology (incidence rate ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.51-0.80).6 These findings highlight the importance of addressing social isolation as an important modifiable health risk factor, and the need for providing equitable access to technology in vulnerable populations as health intervention.

Dr. Mengru “Ruru” Wang is a geriatrician and internist at the University of Washington, Seattle. She practices full-spectrum medicine, seeing patients in primary care, nursing homes, and acute care. Dr. Wang has no disclosures related to this piece.

References

1. LeBoff MS et al. Supplemental vitamin D and incident fractures in midlife and older adults. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(4):299-30.

2. van Dyck CH et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21.

3. The Lancet. Lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: tempering hype and hope. Lancet. 2022; 400:1899.

4. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. Washington, DC: 2020, The National Academies Press.

5. Huang, AR et al. Social isolation and 9-year dementia risk in community dwelling Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/jgs18140.

6. Umoh ME etal. Impact of technology on social isolation: Longitudinal analysis from the National Health Aging Trends Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022 Dec 15. doi 10.1111/jgs.18179.

Vitamin D supplementation and incident fractures

Vitamin D supplementation is a commonly recommended intervention for bone health, but data to support its impact on reducing fracture risk has been variable.

A study in the New England Journal of Medicine by LeBoff and colleagues has garnered much attention since its publication in July 2022.1 In the ancillary study of the Vitamin D and Omega-3-Trial (VITAL), the authors examined the impact of vitamin D supplementation versus placebo on incident fractures. The study found that vitamin D supplementation, as compared with placebo, led to no significant difference in the incidence of total, nonvertebral, and hip fractures in midlife and older adults over the 5-year period of follow-up.

The generalizability of these findings has been raised as a concern as the study does not describe adults at higher risk for fracture. The authors of the study specified in their conclusion that vitamin D supplementation does not reduce fracture risk in “generally healthy midlife and older adults who were not selected for vitamin D deficiency, low bone mass or osteoporosis.”

With a mean participant age of 67 and exclusion of participants with a history of cardiovascular disease, stroke, cirrhosis and other serious illnesses, the study does not reflect the multimorbid older adult population that geriatricians typically care for. Furthermore, efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on fracture risk may be the most impactful in those with osteoporosis and with severe vitamin D deficiency (defined by vitamin D 25[OH]D level less than 12 ng/mL).

In post hoc analyses, there was no significant difference in fracture risk in these subgroups, however the authors acknowledged that the findings may be limited by the small percentage of participants with severe vitamin D deficiency (2.4%) and osteoporosis included in the study (5%).

Lecanemab for mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s dementia

On Jan. 6, 2023, the Food and Drug Administration approved lecanemab, the second-ever disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s dementia following the approval of aducanumab in 2021. Lecanemab is a monoclonal antibody targeting larger amyloid-beta oligomers, which has been shown in vitro to have higher affinity for amyloid-beta, compared with aducanumab. FDA approval followed shortly after the publication of the CLARITY-AD trial, which investigated the effect of lecanemab versus placebo on cognitive decline and burden of amyloid in adults with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s dementia. Over an 18-month period, the study found that participants who received lecanemab, compared with placebo, had a significantly smaller decline in cognition and function, and reduction in amyloid burden on PET CT.2

The clinical significance of these findings, however, is unclear. As noted by an editorial published in the Lancet in 2022, the difference in Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) scale between the treatment and placebo groups was 0.45. On an 18-point scale, prior research has noted that a minimal clinically significance difference of 0.98 is necessary in those with mild cognitive impairment and 1.63 in mild Alzheimer dementia.3

Additionally, the CLARITY-AD trial reported that lecanemab resulted in infusion reactions in 26.4% of participants and brain edema (an amyloid-related imaging abnormality referred to as ARIA-E) in 12.6% of participants. This finding highlights concerns for safety and the need for close monitoring, as well as ongoing implications of economic feasibility and equitable access for all those who qualify for treatment.2

Social isolation and dementia risk

There is growing awareness of the impact of social isolation on health outcomes, particularly among older adults. Prior research has reported that one in four older adults are considered socially isolated and that social isolation increases risk of premature death, dementia, depression, and cardiovascular disease.4

A study by Huang and colleagues is the first nationally representative cohort study examining the association between social isolation and incident dementia for older adults in community dwelling settings. A cohort of 5,022 older adults participating in the National Health and Aging Trends Study was followed from 2011 to 2020. When adjusting for demographic and health factors, including race, level of education, and number of chronic health conditions, socially isolated adults had a greater risk of developing dementia, compared with adults who were not socially isolated (hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.49). Potential mechanisms to explain this association include the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and depression in older adults who are socially isolated, thereby increasing dementia risk.

Decreased cognitive activity/engagement and access to resources such as caregiving and health care may also be linked to the increased risk of dementia in socially isolated older adults.5

Another observational cohort study from the National Health and Aging Trends Study investigated whether access and use of technology can lower the risk of social isolation. The study found that older adults who used email or text messaging had a lower risk of social isolation than older adults who did not use technology (incidence rate ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.51-0.80).6 These findings highlight the importance of addressing social isolation as an important modifiable health risk factor, and the need for providing equitable access to technology in vulnerable populations as health intervention.

Dr. Mengru “Ruru” Wang is a geriatrician and internist at the University of Washington, Seattle. She practices full-spectrum medicine, seeing patients in primary care, nursing homes, and acute care. Dr. Wang has no disclosures related to this piece.

References

1. LeBoff MS et al. Supplemental vitamin D and incident fractures in midlife and older adults. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(4):299-30.