User login

Depression and emotional lability

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 51-year-old man presents with complaints of progressively worsening cognitive impairments, particularly in executive functioning and episodic memory, as well as depression, apathy, and emotional lability. The patient is accompanied by his wife, who states that he often becomes irritable and "flies off the handle" without provocation. The patient's depressive symptoms began approximately 18 months ago, shortly after his mother's death from heart failure. Both he and his wife initially attributed his symptoms to the grieving process; however, in the past 6 months, his depression and mood swings have become increasingly frequent and intense. In addition, he was recently mandated to go on administrative leave from his job as an IT manager because of poor performance and angry outbursts in the workplace. The patient believes that his forgetfulness and difficulty regulating his emotions are the result of the depression he is experiencing. His goal today is to "get on some medication" to help him better manage his emotions and return to work. Although his wife is supportive of her husband, she is concerned about her husband's rapidly progressing deficits in short-term memory and is uncertain that they are related to his emotional symptoms.

The patient's medical history is notable for nine concussions sustained during his time as a high school and college football player; only one resulted in loss of consciousness. He does not currently take any medications. There is no history of tobacco use, illicit drug use, or excessive alcohol consumption. There is no family history of dementia. His current height and weight are 6 ft 3 in and 223 lb, and his BMI is 27.9.

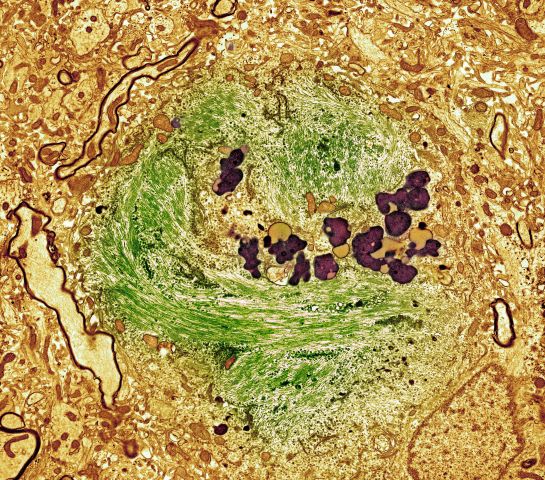

No abnormalities are noted on physical exam; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are all within normal ranges, including thyroid-stimulating hormone and vitamin B12 levels. The patient scores 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, which is a set of 11 questions that doctors and other healthcare professionals commonly use to check for cognitive impairment. His clinician orders a brain MRI, which reveals a tau-positive neurofibrillary tangle in the neocortex.

Two diets tied to lower Alzheimer’s pathology at autopsy

In a cohort of deceased older adults, those who had adhered to the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) and Mediterranean diets for nearly a decade before death had less global Alzheimer’s disease–related pathology, primarily less beta-amyloid, at autopsy.

Those who most closely followed these diets had almost 40% lower odds of having an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis at death. The findings offer one mechanism by which healthy diets protect cognition.

“While our research doesn’t prove that a healthy diet resulted in fewer brain deposits of amyloid plaques ... we know there is a relationship, and following the MIND and Mediterranean diets may be one way that people can improve their brain health and protect cognition as they age,” study investigator Puja Agarwal, PhD, of RUSH University Medical Center in Chicago, said in a statement.

The study was published online in Neurology.

Green leafy veggies key

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died of cancer in 2020 at age 64.

Although similar, the Mediterranean diet recommends vegetables, fruit, and three or more servings of fish per week, whereas the MIND diet prioritizes green leafy vegetables, such as spinach, kale, and collard greens, along with other vegetables. The MIND diet also prioritizes berries over other fruit and recommends one or more servings of fish per week. Both diets recommend small amounts of wine.

The current study focused on 581 older adults who died while participating in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP). All participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations and brain autopsy after death.

Participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires beginning at a mean age of 84. The mean age at death was 91. Mean follow-up was 6.8 years.

Around the time of death, 224 participants (39%) had a diagnosis of clinical dementia, and 383 participants (66%) had a pathologic Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis at time of death.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to investigate the MIND and Mediterranean diets and dietary components associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. They controlled for age at death, sex, education, APO-epsilon 4 status, and total calories.

Overall, both diets were significantly associated with lower global Alzheimer’s disease pathology (MIND: beta = –0.022, P = .034; and Mediterranean: beta = –0.007, P = .039) – specifically, with less beta-amyloid (MIND: beta = –0.068, P = .050; and Mediterranean: beta = –0.040, P = .004).

The findings persisted when the analysis was further adjusted for physical activity, smoking, and vascular disease burden and when participants with mild cognitive impairment or dementia at the baseline dietary assessment were excluded.

Individuals who most closely followed the Mediterranean diet had average beta-amyloid load similar to being 18 years younger than peers with the lowest adherence. And those who most closely followed the MIND diet had average beta-amyloid amounts similar to being 12 years younger than those with the lowest adherence.

A MIND diet score 1 point higher corresponded to typical plaque deposition of participants who are 4.25 years younger in age.

Regarding individual dietary components, those who ate seven or more servings of green leafy vegetables weekly had less global Alzheimer’s disease pathology than peers who ate one or fewer (beta = –0.115, P = .0038). Those who ate seven or more servings per week had plaque amounts in their brains corresponding to being almost 19 years younger in comparison with those who ate the fewest servings per week.

“Our finding that eating more green leafy vegetables is in itself associated with fewer signs of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain is intriguing enough for people to consider adding more of these vegetables to their diet,” Dr. Agarwal said in the news release.

Previous data from the MAP cohort showed that adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Novel study, intriguing results

Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations with the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that a number of studies have linked overall nutrition – especially a balanced diet low in saturated fats and sugar and high in vegetables – with brain health, including cognition, as one ages.

This new study “takes what we know about the link between nutrition and risk for cognitive decline a step further by looking at the specific brain changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease. The study found an association of certain nutrition behaviors with less of these Alzheimer’s brain changes,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the study.

“This is intriguing, and more research is needed to test via an intervention if healthy dietary behaviors can modify the presence of Alzheimer’s brain changes and reduce risk of cognitive decline.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial known as US POINTER to study how targeting known dementia risk factors in combination may reduce risk of cognitive decline in older adults. The MIND diet is being used in US POINTER.

“But while we work to find an exact ‘recipe’ for risk reduction, it’s important to eat a heart-healthy diet that incorporates nutrients that our bodies and brains need to be at their best,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Agarwal and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a cohort of deceased older adults, those who had adhered to the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) and Mediterranean diets for nearly a decade before death had less global Alzheimer’s disease–related pathology, primarily less beta-amyloid, at autopsy.

Those who most closely followed these diets had almost 40% lower odds of having an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis at death. The findings offer one mechanism by which healthy diets protect cognition.

“While our research doesn’t prove that a healthy diet resulted in fewer brain deposits of amyloid plaques ... we know there is a relationship, and following the MIND and Mediterranean diets may be one way that people can improve their brain health and protect cognition as they age,” study investigator Puja Agarwal, PhD, of RUSH University Medical Center in Chicago, said in a statement.

The study was published online in Neurology.

Green leafy veggies key

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died of cancer in 2020 at age 64.

Although similar, the Mediterranean diet recommends vegetables, fruit, and three or more servings of fish per week, whereas the MIND diet prioritizes green leafy vegetables, such as spinach, kale, and collard greens, along with other vegetables. The MIND diet also prioritizes berries over other fruit and recommends one or more servings of fish per week. Both diets recommend small amounts of wine.

The current study focused on 581 older adults who died while participating in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP). All participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations and brain autopsy after death.

Participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires beginning at a mean age of 84. The mean age at death was 91. Mean follow-up was 6.8 years.

Around the time of death, 224 participants (39%) had a diagnosis of clinical dementia, and 383 participants (66%) had a pathologic Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis at time of death.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to investigate the MIND and Mediterranean diets and dietary components associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. They controlled for age at death, sex, education, APO-epsilon 4 status, and total calories.

Overall, both diets were significantly associated with lower global Alzheimer’s disease pathology (MIND: beta = –0.022, P = .034; and Mediterranean: beta = –0.007, P = .039) – specifically, with less beta-amyloid (MIND: beta = –0.068, P = .050; and Mediterranean: beta = –0.040, P = .004).

The findings persisted when the analysis was further adjusted for physical activity, smoking, and vascular disease burden and when participants with mild cognitive impairment or dementia at the baseline dietary assessment were excluded.

Individuals who most closely followed the Mediterranean diet had average beta-amyloid load similar to being 18 years younger than peers with the lowest adherence. And those who most closely followed the MIND diet had average beta-amyloid amounts similar to being 12 years younger than those with the lowest adherence.

A MIND diet score 1 point higher corresponded to typical plaque deposition of participants who are 4.25 years younger in age.

Regarding individual dietary components, those who ate seven or more servings of green leafy vegetables weekly had less global Alzheimer’s disease pathology than peers who ate one or fewer (beta = –0.115, P = .0038). Those who ate seven or more servings per week had plaque amounts in their brains corresponding to being almost 19 years younger in comparison with those who ate the fewest servings per week.

“Our finding that eating more green leafy vegetables is in itself associated with fewer signs of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain is intriguing enough for people to consider adding more of these vegetables to their diet,” Dr. Agarwal said in the news release.

Previous data from the MAP cohort showed that adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Novel study, intriguing results

Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations with the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that a number of studies have linked overall nutrition – especially a balanced diet low in saturated fats and sugar and high in vegetables – with brain health, including cognition, as one ages.

This new study “takes what we know about the link between nutrition and risk for cognitive decline a step further by looking at the specific brain changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease. The study found an association of certain nutrition behaviors with less of these Alzheimer’s brain changes,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the study.

“This is intriguing, and more research is needed to test via an intervention if healthy dietary behaviors can modify the presence of Alzheimer’s brain changes and reduce risk of cognitive decline.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial known as US POINTER to study how targeting known dementia risk factors in combination may reduce risk of cognitive decline in older adults. The MIND diet is being used in US POINTER.

“But while we work to find an exact ‘recipe’ for risk reduction, it’s important to eat a heart-healthy diet that incorporates nutrients that our bodies and brains need to be at their best,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Agarwal and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a cohort of deceased older adults, those who had adhered to the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) and Mediterranean diets for nearly a decade before death had less global Alzheimer’s disease–related pathology, primarily less beta-amyloid, at autopsy.

Those who most closely followed these diets had almost 40% lower odds of having an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis at death. The findings offer one mechanism by which healthy diets protect cognition.

“While our research doesn’t prove that a healthy diet resulted in fewer brain deposits of amyloid plaques ... we know there is a relationship, and following the MIND and Mediterranean diets may be one way that people can improve their brain health and protect cognition as they age,” study investigator Puja Agarwal, PhD, of RUSH University Medical Center in Chicago, said in a statement.

The study was published online in Neurology.

Green leafy veggies key

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died of cancer in 2020 at age 64.

Although similar, the Mediterranean diet recommends vegetables, fruit, and three or more servings of fish per week, whereas the MIND diet prioritizes green leafy vegetables, such as spinach, kale, and collard greens, along with other vegetables. The MIND diet also prioritizes berries over other fruit and recommends one or more servings of fish per week. Both diets recommend small amounts of wine.

The current study focused on 581 older adults who died while participating in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP). All participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations and brain autopsy after death.

Participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires beginning at a mean age of 84. The mean age at death was 91. Mean follow-up was 6.8 years.

Around the time of death, 224 participants (39%) had a diagnosis of clinical dementia, and 383 participants (66%) had a pathologic Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis at time of death.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to investigate the MIND and Mediterranean diets and dietary components associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. They controlled for age at death, sex, education, APO-epsilon 4 status, and total calories.

Overall, both diets were significantly associated with lower global Alzheimer’s disease pathology (MIND: beta = –0.022, P = .034; and Mediterranean: beta = –0.007, P = .039) – specifically, with less beta-amyloid (MIND: beta = –0.068, P = .050; and Mediterranean: beta = –0.040, P = .004).

The findings persisted when the analysis was further adjusted for physical activity, smoking, and vascular disease burden and when participants with mild cognitive impairment or dementia at the baseline dietary assessment were excluded.

Individuals who most closely followed the Mediterranean diet had average beta-amyloid load similar to being 18 years younger than peers with the lowest adherence. And those who most closely followed the MIND diet had average beta-amyloid amounts similar to being 12 years younger than those with the lowest adherence.

A MIND diet score 1 point higher corresponded to typical plaque deposition of participants who are 4.25 years younger in age.

Regarding individual dietary components, those who ate seven or more servings of green leafy vegetables weekly had less global Alzheimer’s disease pathology than peers who ate one or fewer (beta = –0.115, P = .0038). Those who ate seven or more servings per week had plaque amounts in their brains corresponding to being almost 19 years younger in comparison with those who ate the fewest servings per week.

“Our finding that eating more green leafy vegetables is in itself associated with fewer signs of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain is intriguing enough for people to consider adding more of these vegetables to their diet,” Dr. Agarwal said in the news release.

Previous data from the MAP cohort showed that adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Novel study, intriguing results

Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations with the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that a number of studies have linked overall nutrition – especially a balanced diet low in saturated fats and sugar and high in vegetables – with brain health, including cognition, as one ages.

This new study “takes what we know about the link between nutrition and risk for cognitive decline a step further by looking at the specific brain changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease. The study found an association of certain nutrition behaviors with less of these Alzheimer’s brain changes,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the study.

“This is intriguing, and more research is needed to test via an intervention if healthy dietary behaviors can modify the presence of Alzheimer’s brain changes and reduce risk of cognitive decline.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial known as US POINTER to study how targeting known dementia risk factors in combination may reduce risk of cognitive decline in older adults. The MIND diet is being used in US POINTER.

“But while we work to find an exact ‘recipe’ for risk reduction, it’s important to eat a heart-healthy diet that incorporates nutrients that our bodies and brains need to be at their best,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Agarwal and Dr. Snyder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROLOGY

High stress levels linked to cognitive decline

, a new study shows.

Individuals with elevated stress levels also had higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. But even after controlling for those risk factors, stress remained an independent predictor of cognitive decline.

The national cohort study showed that the association between stress and cognition was similar between Black and White individuals and that those with controlled stress were less likely to have cognitive impairment than those with uncontrolled or new stress.

“We have known for a while that excess levels of stress can be harmful for the human body and the heart, but we are now adding more evidence that excess levels of stress can be harmful for cognition,” said lead investigator Ambar Kulshreshtha, MD, PhD, associate professor of family and preventive medicine and epidemiology at Emory University, Atlanta. “We were able to see that regardless of race or gender, stress is bad.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Independent risk factor

For the study, investigators analyzed data from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, a national population-based cohort of Black and White participants aged 45 years or older, sampled from the U.S. population.

Participants completed a questionnaire designed to evaluate stress levels when they were enrolled in the study between 2003 and 2007 and again about 11 years after enrollment.

Of the 24,448 participants (41.6% Black) in the study, 22.9% reported elevated stress levels.

Those with high stress were more likely to be younger, female, Black, smokers, and have a higher body mass index and less likely to have a college degree and to be physically active. They also had a lower family income and were more likely to have cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Participants with elevated levels of perceived stress were 37% more likely to have poor cognition after adjustment for sociodemographic variables, cardiovascular risk factors, and depression (adjusted odds ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.22-1.53).

There was no significant difference between Black and White participants.

Damaging consequences

Researchers also found a dose-response relationship, with the greatest cognitive decline found in people who reported high stress at both time points and those who had new stress at follow up (aOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.92-1.45), compared with those with resolved stress (aOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.81-1.32) or no stress (aOR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.97).

A change in perceived stress by 1 unit was associated with 4% increased risk of cognitive impairment after adjusting for sociodemographic variables, CVD risk factors, lifestyle factors, and depressive symptoms (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06).

Although the study didn’t reveal the mechanisms that might link stress and cognition, it does point to stress as a potentially modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline, Dr. Kulshreshtha said.

“One in three of my patients have had to deal with extra levels of stress and anxiety over the past few years,” said Dr. Kulshreshtha. “We as clinicians are aware that stress can have damaging consequences to the heart and other organs, and when we see patients who have these complaints, especially elderly patients, we should spend some time asking people about their stress and how they are managing it.”

Additional screening

Gregory Day, MD, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., said that the findings help fill a void in the research about stress and cognition.

“It’s a potentially important association that’s easy for us to miss in clinical practice,” said Dr. Day, who was not a part of the study. “It’s one of those things that we can all recognize impacts health, but we have very few large, well thought out studies that give us the data we need to inform its place in clinical decision-making.”

In addition to its large sample size, the overrepresentation of diverse populations is a strength of the study and a contribution to the field, Dr. Day said.

“One question they don’t directly ask is, is this association maybe due to some differences in stress? And the answer from the paper is probably not, because it looks like when we control for these things, we don’t see big differences incident risk factors between race,” he added.

The findings also point to the need for clinicians, especially primary care physicians, to screen patients for stress during routine examinations.

“Every visit is an opportunity to screen for risk factors that are going to set people up for future brain health,” Dr. Day said. “In addition to screening for all of these other risk factors for brain health, maybe it’s worth including some more global assessment of stress in a standard screener.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Kulshreshtha and Dr. Day report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

Individuals with elevated stress levels also had higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. But even after controlling for those risk factors, stress remained an independent predictor of cognitive decline.

The national cohort study showed that the association between stress and cognition was similar between Black and White individuals and that those with controlled stress were less likely to have cognitive impairment than those with uncontrolled or new stress.

“We have known for a while that excess levels of stress can be harmful for the human body and the heart, but we are now adding more evidence that excess levels of stress can be harmful for cognition,” said lead investigator Ambar Kulshreshtha, MD, PhD, associate professor of family and preventive medicine and epidemiology at Emory University, Atlanta. “We were able to see that regardless of race or gender, stress is bad.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Independent risk factor

For the study, investigators analyzed data from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, a national population-based cohort of Black and White participants aged 45 years or older, sampled from the U.S. population.

Participants completed a questionnaire designed to evaluate stress levels when they were enrolled in the study between 2003 and 2007 and again about 11 years after enrollment.

Of the 24,448 participants (41.6% Black) in the study, 22.9% reported elevated stress levels.

Those with high stress were more likely to be younger, female, Black, smokers, and have a higher body mass index and less likely to have a college degree and to be physically active. They also had a lower family income and were more likely to have cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Participants with elevated levels of perceived stress were 37% more likely to have poor cognition after adjustment for sociodemographic variables, cardiovascular risk factors, and depression (adjusted odds ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.22-1.53).

There was no significant difference between Black and White participants.

Damaging consequences

Researchers also found a dose-response relationship, with the greatest cognitive decline found in people who reported high stress at both time points and those who had new stress at follow up (aOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.92-1.45), compared with those with resolved stress (aOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.81-1.32) or no stress (aOR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.97).

A change in perceived stress by 1 unit was associated with 4% increased risk of cognitive impairment after adjusting for sociodemographic variables, CVD risk factors, lifestyle factors, and depressive symptoms (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06).

Although the study didn’t reveal the mechanisms that might link stress and cognition, it does point to stress as a potentially modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline, Dr. Kulshreshtha said.

“One in three of my patients have had to deal with extra levels of stress and anxiety over the past few years,” said Dr. Kulshreshtha. “We as clinicians are aware that stress can have damaging consequences to the heart and other organs, and when we see patients who have these complaints, especially elderly patients, we should spend some time asking people about their stress and how they are managing it.”

Additional screening

Gregory Day, MD, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., said that the findings help fill a void in the research about stress and cognition.

“It’s a potentially important association that’s easy for us to miss in clinical practice,” said Dr. Day, who was not a part of the study. “It’s one of those things that we can all recognize impacts health, but we have very few large, well thought out studies that give us the data we need to inform its place in clinical decision-making.”

In addition to its large sample size, the overrepresentation of diverse populations is a strength of the study and a contribution to the field, Dr. Day said.

“One question they don’t directly ask is, is this association maybe due to some differences in stress? And the answer from the paper is probably not, because it looks like when we control for these things, we don’t see big differences incident risk factors between race,” he added.

The findings also point to the need for clinicians, especially primary care physicians, to screen patients for stress during routine examinations.

“Every visit is an opportunity to screen for risk factors that are going to set people up for future brain health,” Dr. Day said. “In addition to screening for all of these other risk factors for brain health, maybe it’s worth including some more global assessment of stress in a standard screener.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Kulshreshtha and Dr. Day report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

Individuals with elevated stress levels also had higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. But even after controlling for those risk factors, stress remained an independent predictor of cognitive decline.

The national cohort study showed that the association between stress and cognition was similar between Black and White individuals and that those with controlled stress were less likely to have cognitive impairment than those with uncontrolled or new stress.

“We have known for a while that excess levels of stress can be harmful for the human body and the heart, but we are now adding more evidence that excess levels of stress can be harmful for cognition,” said lead investigator Ambar Kulshreshtha, MD, PhD, associate professor of family and preventive medicine and epidemiology at Emory University, Atlanta. “We were able to see that regardless of race or gender, stress is bad.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Independent risk factor

For the study, investigators analyzed data from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, a national population-based cohort of Black and White participants aged 45 years or older, sampled from the U.S. population.

Participants completed a questionnaire designed to evaluate stress levels when they were enrolled in the study between 2003 and 2007 and again about 11 years after enrollment.

Of the 24,448 participants (41.6% Black) in the study, 22.9% reported elevated stress levels.

Those with high stress were more likely to be younger, female, Black, smokers, and have a higher body mass index and less likely to have a college degree and to be physically active. They also had a lower family income and were more likely to have cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Participants with elevated levels of perceived stress were 37% more likely to have poor cognition after adjustment for sociodemographic variables, cardiovascular risk factors, and depression (adjusted odds ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.22-1.53).

There was no significant difference between Black and White participants.

Damaging consequences

Researchers also found a dose-response relationship, with the greatest cognitive decline found in people who reported high stress at both time points and those who had new stress at follow up (aOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.92-1.45), compared with those with resolved stress (aOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.81-1.32) or no stress (aOR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.97).

A change in perceived stress by 1 unit was associated with 4% increased risk of cognitive impairment after adjusting for sociodemographic variables, CVD risk factors, lifestyle factors, and depressive symptoms (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06).

Although the study didn’t reveal the mechanisms that might link stress and cognition, it does point to stress as a potentially modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline, Dr. Kulshreshtha said.

“One in three of my patients have had to deal with extra levels of stress and anxiety over the past few years,” said Dr. Kulshreshtha. “We as clinicians are aware that stress can have damaging consequences to the heart and other organs, and when we see patients who have these complaints, especially elderly patients, we should spend some time asking people about their stress and how they are managing it.”

Additional screening

Gregory Day, MD, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., said that the findings help fill a void in the research about stress and cognition.

“It’s a potentially important association that’s easy for us to miss in clinical practice,” said Dr. Day, who was not a part of the study. “It’s one of those things that we can all recognize impacts health, but we have very few large, well thought out studies that give us the data we need to inform its place in clinical decision-making.”

In addition to its large sample size, the overrepresentation of diverse populations is a strength of the study and a contribution to the field, Dr. Day said.

“One question they don’t directly ask is, is this association maybe due to some differences in stress? And the answer from the paper is probably not, because it looks like when we control for these things, we don’t see big differences incident risk factors between race,” he added.

The findings also point to the need for clinicians, especially primary care physicians, to screen patients for stress during routine examinations.

“Every visit is an opportunity to screen for risk factors that are going to set people up for future brain health,” Dr. Day said. “In addition to screening for all of these other risk factors for brain health, maybe it’s worth including some more global assessment of stress in a standard screener.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Kulshreshtha and Dr. Day report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From JAMA Network Open

Alzheimer's Disease Presentation

Antipsychotic cuts Alzheimer’s-related agitation

results of a phase 3 study suggest.

“In this phase 3 trial of patients with agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia, treatment with brexpiprazole 2 or 3 mg/day resulted in statistically significantly greater improvements in agitation versus placebo on the primary and key secondary endpoints,” said study investigator George Grossberg, MD, professor and director of the division of geriatric psychiatry, department of psychiatry & behavioral neuroscience, Saint Louis University.

Dr. Grossberg presented the findings as part of the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

Agitation common, distressing

With two previous studies also showing efficacy of brexpiprazole in AD-related agitation, Dr. Grossberg speculated that brexpiprazole will become the first drug to be approved for agitation in AD.

Agitation is one of the most common AD symptoms and is arguably the most distressing for patients and caregivers alike, Dr. Grossberg noted.

The drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for adults with major depressive disorder and for adults with schizophrenia.

To investigate the drug at effective doses for AD-related agitation, the researchers conducted a phase 3 multicenter trial that included 345 patients with AD who met criteria for agitation and aggression.

Study participants had a mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 5 and 22 at screening and baseline and a mean Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) total score of about 79. A score above 45 is considered clinically significant agitation. Use of AD medications were permitted.

Patients had a mean age of 74 years and were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive treatment with brexpiprazole 2 mg (n = 75) or 3 mg (n = 153) per day, or placebo (n = 117).

The study’s primary endpoint was improvement as assessed by the CMAI. Over 12 weeks, participants in the brexpiprazole group experienced greater improvement in agitation, with a mean change of –22.6 with brexpiprazole vs. –17.3 with placebo (P = .0026).

Brexpiprazole was also associated with significantly greater improvement in the secondary outcome of change from baseline to week 12 in agitation severity, as assessed using the Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score (mean change, –1.20 with brexpiprazole vs. –0.93 with placebo; P = .0078).

Specifically, treatment with the drug resulted in improvements in three key subscales of agitation, including aggressive behavior, such as physically striking out (P < .01 vs. placebo); physically nonaggressive; and verbally agitated, such as screaming or cursing (both P < .05).

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) associated with brexpiprazole vs. placebo included somnolence (3.5% vs. 0.9%), nasopharyngitis (3.1% vs. 1.7%), dizziness (2.7% vs. 1.7%), diarrhea (2.2% vs. 0.9%), urinary tract infection (2.2% vs. 0.9%), and asthenia (2.2% vs. 0.0%).

“Aside from headache, no other TEAEs had an incidence of more than 5% in the brexpiprazole (2 or 3 mg) group, or in either dose group,” Dr. Grossberg said. “Cognition also remained stable,” he added.

Boxed warnings

Adverse events commonly associated with brexpiprazole include weight change, extrapyramidal events, falls, cardiovascular events, and sedation. In the study, all occurred at an incidence of less than 2% in both study groups, he noted.

Compared with the antipsychotic aripiprazole, brexpiprazole is associated with lower weight gain and akathisia, or motor restlessness.

One death occurred in the brexpiprazole 3 mg group in a patient who had heart failure, pneumonia, and cachexia. At autopsy, it was found the patient had cerebral and coronary atherosclerosis. The death was considered to be unrelated to brexpiprazole, said Dr. Grossberg.

This finding is notable because a caveat is that brexpiprazole, like aripiprazole and other typical and atypical antipsychotics, carries an FDA boxed warning related to an increased risk for death in older patients when used for dementia-related psychosis.

Noting that a black box warning about mortality risk is not a minor issue, Dr. Grossberg added that the risks are relatively low, whereas the risks associated with agitation in dementia can be high.

“If it’s an emergency situation, you have to treat the patient because otherwise they may harm someone else, or harm the staff, or harm their loved ones or themselves, and in those cases, we want to treat the patient first, get them under control, and then we worry about the black box,” he said.

In addition, “the No. 1 reason for getting kicked out of a nursing home is agitation or severe behaviors in the context of a dementia or a major neurocognitive disorder that the facility cannot control,” Dr. Grossberg added.

In such cases, patients may wind up in an emergency department and may not be welcome back at the nursing home.

“There’s always a risk/benefit ratio, and I have that discussion with patients and their families, but I can tell you that I’ve never had a family ask me not to use a medication because of the black box warning, because they see how miserable and how out of control their loved one is and they’re miserable because they see the suffering and will ask that we do anything that we can to get this behavior under control,” Dr. Grossberg said.

Caution still warranted

Commenting on the study, Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, professor and chairman of the department of psychiatry and the Bhatia Family Endowed Chair in Psychiatry at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., underscored that, owing to the concerns behind the FDA warnings, “nonpharmacologic management is the cornerstone of treating agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia.”

He noted that the lack of an FDA-approved drug for agitation with AD is the result of “the overall benefits of any of the drug classes or drugs trialed to treat agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia vs. their adverse effect profile,” he said.

Therefore, he continued, “any medication or medication class should be used with caution among these individuals who often have polymorbidity.”

Dr. Tampi agreed that “the use of each drug for agitation in AD should be on a case-by-case basis with a clear and documented risk/benefit discussion with the patient and their families.”

“These medications should only be used for refractory symptoms or emergency situations where the agitation is not managed adequately with nonpharmacologic techniques and with a clear and documented risk/benefit discussion with patients and their families,” Dr. Tampi said.

The study was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization and H. Lundbeck. Dr. Grossberg has received consulting fees from Acadia, Avanir, Biogen, BioXcel, Genentech, Karuna, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Roche, and Takeda. Dr. Tampi had no disclosures to report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 3/14/23.

results of a phase 3 study suggest.

“In this phase 3 trial of patients with agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia, treatment with brexpiprazole 2 or 3 mg/day resulted in statistically significantly greater improvements in agitation versus placebo on the primary and key secondary endpoints,” said study investigator George Grossberg, MD, professor and director of the division of geriatric psychiatry, department of psychiatry & behavioral neuroscience, Saint Louis University.

Dr. Grossberg presented the findings as part of the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

Agitation common, distressing

With two previous studies also showing efficacy of brexpiprazole in AD-related agitation, Dr. Grossberg speculated that brexpiprazole will become the first drug to be approved for agitation in AD.

Agitation is one of the most common AD symptoms and is arguably the most distressing for patients and caregivers alike, Dr. Grossberg noted.

The drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for adults with major depressive disorder and for adults with schizophrenia.

To investigate the drug at effective doses for AD-related agitation, the researchers conducted a phase 3 multicenter trial that included 345 patients with AD who met criteria for agitation and aggression.

Study participants had a mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 5 and 22 at screening and baseline and a mean Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) total score of about 79. A score above 45 is considered clinically significant agitation. Use of AD medications were permitted.

Patients had a mean age of 74 years and were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive treatment with brexpiprazole 2 mg (n = 75) or 3 mg (n = 153) per day, or placebo (n = 117).

The study’s primary endpoint was improvement as assessed by the CMAI. Over 12 weeks, participants in the brexpiprazole group experienced greater improvement in agitation, with a mean change of –22.6 with brexpiprazole vs. –17.3 with placebo (P = .0026).

Brexpiprazole was also associated with significantly greater improvement in the secondary outcome of change from baseline to week 12 in agitation severity, as assessed using the Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score (mean change, –1.20 with brexpiprazole vs. –0.93 with placebo; P = .0078).

Specifically, treatment with the drug resulted in improvements in three key subscales of agitation, including aggressive behavior, such as physically striking out (P < .01 vs. placebo); physically nonaggressive; and verbally agitated, such as screaming or cursing (both P < .05).

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) associated with brexpiprazole vs. placebo included somnolence (3.5% vs. 0.9%), nasopharyngitis (3.1% vs. 1.7%), dizziness (2.7% vs. 1.7%), diarrhea (2.2% vs. 0.9%), urinary tract infection (2.2% vs. 0.9%), and asthenia (2.2% vs. 0.0%).

“Aside from headache, no other TEAEs had an incidence of more than 5% in the brexpiprazole (2 or 3 mg) group, or in either dose group,” Dr. Grossberg said. “Cognition also remained stable,” he added.

Boxed warnings

Adverse events commonly associated with brexpiprazole include weight change, extrapyramidal events, falls, cardiovascular events, and sedation. In the study, all occurred at an incidence of less than 2% in both study groups, he noted.

Compared with the antipsychotic aripiprazole, brexpiprazole is associated with lower weight gain and akathisia, or motor restlessness.

One death occurred in the brexpiprazole 3 mg group in a patient who had heart failure, pneumonia, and cachexia. At autopsy, it was found the patient had cerebral and coronary atherosclerosis. The death was considered to be unrelated to brexpiprazole, said Dr. Grossberg.

This finding is notable because a caveat is that brexpiprazole, like aripiprazole and other typical and atypical antipsychotics, carries an FDA boxed warning related to an increased risk for death in older patients when used for dementia-related psychosis.

Noting that a black box warning about mortality risk is not a minor issue, Dr. Grossberg added that the risks are relatively low, whereas the risks associated with agitation in dementia can be high.

“If it’s an emergency situation, you have to treat the patient because otherwise they may harm someone else, or harm the staff, or harm their loved ones or themselves, and in those cases, we want to treat the patient first, get them under control, and then we worry about the black box,” he said.

In addition, “the No. 1 reason for getting kicked out of a nursing home is agitation or severe behaviors in the context of a dementia or a major neurocognitive disorder that the facility cannot control,” Dr. Grossberg added.

In such cases, patients may wind up in an emergency department and may not be welcome back at the nursing home.

“There’s always a risk/benefit ratio, and I have that discussion with patients and their families, but I can tell you that I’ve never had a family ask me not to use a medication because of the black box warning, because they see how miserable and how out of control their loved one is and they’re miserable because they see the suffering and will ask that we do anything that we can to get this behavior under control,” Dr. Grossberg said.

Caution still warranted

Commenting on the study, Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, professor and chairman of the department of psychiatry and the Bhatia Family Endowed Chair in Psychiatry at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., underscored that, owing to the concerns behind the FDA warnings, “nonpharmacologic management is the cornerstone of treating agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia.”

He noted that the lack of an FDA-approved drug for agitation with AD is the result of “the overall benefits of any of the drug classes or drugs trialed to treat agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia vs. their adverse effect profile,” he said.

Therefore, he continued, “any medication or medication class should be used with caution among these individuals who often have polymorbidity.”

Dr. Tampi agreed that “the use of each drug for agitation in AD should be on a case-by-case basis with a clear and documented risk/benefit discussion with the patient and their families.”

“These medications should only be used for refractory symptoms or emergency situations where the agitation is not managed adequately with nonpharmacologic techniques and with a clear and documented risk/benefit discussion with patients and their families,” Dr. Tampi said.

The study was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization and H. Lundbeck. Dr. Grossberg has received consulting fees from Acadia, Avanir, Biogen, BioXcel, Genentech, Karuna, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Roche, and Takeda. Dr. Tampi had no disclosures to report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 3/14/23.

results of a phase 3 study suggest.

“In this phase 3 trial of patients with agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia, treatment with brexpiprazole 2 or 3 mg/day resulted in statistically significantly greater improvements in agitation versus placebo on the primary and key secondary endpoints,” said study investigator George Grossberg, MD, professor and director of the division of geriatric psychiatry, department of psychiatry & behavioral neuroscience, Saint Louis University.

Dr. Grossberg presented the findings as part of the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

Agitation common, distressing

With two previous studies also showing efficacy of brexpiprazole in AD-related agitation, Dr. Grossberg speculated that brexpiprazole will become the first drug to be approved for agitation in AD.

Agitation is one of the most common AD symptoms and is arguably the most distressing for patients and caregivers alike, Dr. Grossberg noted.

The drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for adults with major depressive disorder and for adults with schizophrenia.

To investigate the drug at effective doses for AD-related agitation, the researchers conducted a phase 3 multicenter trial that included 345 patients with AD who met criteria for agitation and aggression.

Study participants had a mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 5 and 22 at screening and baseline and a mean Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) total score of about 79. A score above 45 is considered clinically significant agitation. Use of AD medications were permitted.

Patients had a mean age of 74 years and were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive treatment with brexpiprazole 2 mg (n = 75) or 3 mg (n = 153) per day, or placebo (n = 117).

The study’s primary endpoint was improvement as assessed by the CMAI. Over 12 weeks, participants in the brexpiprazole group experienced greater improvement in agitation, with a mean change of –22.6 with brexpiprazole vs. –17.3 with placebo (P = .0026).

Brexpiprazole was also associated with significantly greater improvement in the secondary outcome of change from baseline to week 12 in agitation severity, as assessed using the Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score (mean change, –1.20 with brexpiprazole vs. –0.93 with placebo; P = .0078).

Specifically, treatment with the drug resulted in improvements in three key subscales of agitation, including aggressive behavior, such as physically striking out (P < .01 vs. placebo); physically nonaggressive; and verbally agitated, such as screaming or cursing (both P < .05).

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) associated with brexpiprazole vs. placebo included somnolence (3.5% vs. 0.9%), nasopharyngitis (3.1% vs. 1.7%), dizziness (2.7% vs. 1.7%), diarrhea (2.2% vs. 0.9%), urinary tract infection (2.2% vs. 0.9%), and asthenia (2.2% vs. 0.0%).

“Aside from headache, no other TEAEs had an incidence of more than 5% in the brexpiprazole (2 or 3 mg) group, or in either dose group,” Dr. Grossberg said. “Cognition also remained stable,” he added.

Boxed warnings

Adverse events commonly associated with brexpiprazole include weight change, extrapyramidal events, falls, cardiovascular events, and sedation. In the study, all occurred at an incidence of less than 2% in both study groups, he noted.

Compared with the antipsychotic aripiprazole, brexpiprazole is associated with lower weight gain and akathisia, or motor restlessness.

One death occurred in the brexpiprazole 3 mg group in a patient who had heart failure, pneumonia, and cachexia. At autopsy, it was found the patient had cerebral and coronary atherosclerosis. The death was considered to be unrelated to brexpiprazole, said Dr. Grossberg.

This finding is notable because a caveat is that brexpiprazole, like aripiprazole and other typical and atypical antipsychotics, carries an FDA boxed warning related to an increased risk for death in older patients when used for dementia-related psychosis.

Noting that a black box warning about mortality risk is not a minor issue, Dr. Grossberg added that the risks are relatively low, whereas the risks associated with agitation in dementia can be high.

“If it’s an emergency situation, you have to treat the patient because otherwise they may harm someone else, or harm the staff, or harm their loved ones or themselves, and in those cases, we want to treat the patient first, get them under control, and then we worry about the black box,” he said.

In addition, “the No. 1 reason for getting kicked out of a nursing home is agitation or severe behaviors in the context of a dementia or a major neurocognitive disorder that the facility cannot control,” Dr. Grossberg added.

In such cases, patients may wind up in an emergency department and may not be welcome back at the nursing home.

“There’s always a risk/benefit ratio, and I have that discussion with patients and their families, but I can tell you that I’ve never had a family ask me not to use a medication because of the black box warning, because they see how miserable and how out of control their loved one is and they’re miserable because they see the suffering and will ask that we do anything that we can to get this behavior under control,” Dr. Grossberg said.

Caution still warranted

Commenting on the study, Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, professor and chairman of the department of psychiatry and the Bhatia Family Endowed Chair in Psychiatry at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., underscored that, owing to the concerns behind the FDA warnings, “nonpharmacologic management is the cornerstone of treating agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia.”

He noted that the lack of an FDA-approved drug for agitation with AD is the result of “the overall benefits of any of the drug classes or drugs trialed to treat agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia vs. their adverse effect profile,” he said.

Therefore, he continued, “any medication or medication class should be used with caution among these individuals who often have polymorbidity.”

Dr. Tampi agreed that “the use of each drug for agitation in AD should be on a case-by-case basis with a clear and documented risk/benefit discussion with the patient and their families.”

“These medications should only be used for refractory symptoms or emergency situations where the agitation is not managed adequately with nonpharmacologic techniques and with a clear and documented risk/benefit discussion with patients and their families,” Dr. Tampi said.

The study was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization and H. Lundbeck. Dr. Grossberg has received consulting fees from Acadia, Avanir, Biogen, BioXcel, Genentech, Karuna, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Roche, and Takeda. Dr. Tampi had no disclosures to report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 3/14/23.

AT AAGP 2023

Cognitive remediation training reduces aggression in schizophrenia

Aggressive behavior, including verbal or physical threats or violent acts, is at least four times more likely among individuals with schizophrenia, compared with the general population, wrote Anzalee Khan, PhD, of the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, Orangeburg, N.Y., and colleagues. Recent studies suggest that psychosocial treatments such as cognitive remediation training (CRT) or social cognition training (SCT) may be helpful, but the potential benefit of combining these strategies has not been explored, they said.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research , the authors randomized 62 adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder to 36 sessions of a combination treatment with cognitive remediation and social cognition; 68 were randomized to cognitive remediation and computer-based control treatment. Participants also had at least one confirmed assault in the past year, or scores of 5 or higher on the Life History of Aggression scale. Complete data were analyzed for 45 patients in the CRT/SRT group and 34 in the CRT control group.

The primary outcome was the measure of aggression using the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (OAS-M) in which higher scores indicate higher levels of aggression. Incidents of aggression were coded based on hospital staff reports and summarized weekly. The mean age of the participants was 34.9 years (ranging from 18 to 60 years), 85% were male, and the mean years of education was 11.5.

At the study’s end (14 weeks), participants in both groups showed significant reductions in measures of aggression from baseline, with the largest effect size for the total global OAS-M score (effect size 1.11 for CRT plus SCT and 0.73 for the CRT plus control group).

The results failed to confirm the hypothesis that the combination of CRT and SCT would significantly increase improvements in aggression compared with CRT alone, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Potential reasons include underdosed SCT intervention (only 12 sessions) and the nature of the SCT used in the study, which had few aggressive social interaction models and more models related to social engagement.

Although adding SCT did not have a significant impact on aggression, patients in the CRT plus SCT group showed greater improvement in cognitive function, emotion recognition, and mentalizing, compared with the controls without SCT, the researchers noted.

“While these findings are not surprising given that participants in the CRT plus SCT group received active social cognition training, they do support the idea that social cognition training may have contributed to further strengthen our effect on cognition,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors including the study population of individuals with chronic schizophrenia and low levels of function in long-term tertiary care, which may limit generalizability, and the inability to control for the effects of pharmacotherapy, the researchers said.

However, the results were strengthened by the multidimensional assessments at both time points and the use of two cognitive and social cognition interventions, and suggest that adding social cognitive training enhanced the effect of CRT on cognitive function, emotion regulation, and mentalizing capacity, they said.

“Future studies are needed to examine the antiaggressive effects of a more intensive and more targeted social cognition intervention combined with CRT,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and the Weill Cornell Clinical and Translational Science Award Program, National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Aggressive behavior, including verbal or physical threats or violent acts, is at least four times more likely among individuals with schizophrenia, compared with the general population, wrote Anzalee Khan, PhD, of the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, Orangeburg, N.Y., and colleagues. Recent studies suggest that psychosocial treatments such as cognitive remediation training (CRT) or social cognition training (SCT) may be helpful, but the potential benefit of combining these strategies has not been explored, they said.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research , the authors randomized 62 adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder to 36 sessions of a combination treatment with cognitive remediation and social cognition; 68 were randomized to cognitive remediation and computer-based control treatment. Participants also had at least one confirmed assault in the past year, or scores of 5 or higher on the Life History of Aggression scale. Complete data were analyzed for 45 patients in the CRT/SRT group and 34 in the CRT control group.

The primary outcome was the measure of aggression using the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (OAS-M) in which higher scores indicate higher levels of aggression. Incidents of aggression were coded based on hospital staff reports and summarized weekly. The mean age of the participants was 34.9 years (ranging from 18 to 60 years), 85% were male, and the mean years of education was 11.5.

At the study’s end (14 weeks), participants in both groups showed significant reductions in measures of aggression from baseline, with the largest effect size for the total global OAS-M score (effect size 1.11 for CRT plus SCT and 0.73 for the CRT plus control group).

The results failed to confirm the hypothesis that the combination of CRT and SCT would significantly increase improvements in aggression compared with CRT alone, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Potential reasons include underdosed SCT intervention (only 12 sessions) and the nature of the SCT used in the study, which had few aggressive social interaction models and more models related to social engagement.

Although adding SCT did not have a significant impact on aggression, patients in the CRT plus SCT group showed greater improvement in cognitive function, emotion recognition, and mentalizing, compared with the controls without SCT, the researchers noted.

“While these findings are not surprising given that participants in the CRT plus SCT group received active social cognition training, they do support the idea that social cognition training may have contributed to further strengthen our effect on cognition,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors including the study population of individuals with chronic schizophrenia and low levels of function in long-term tertiary care, which may limit generalizability, and the inability to control for the effects of pharmacotherapy, the researchers said.

However, the results were strengthened by the multidimensional assessments at both time points and the use of two cognitive and social cognition interventions, and suggest that adding social cognitive training enhanced the effect of CRT on cognitive function, emotion regulation, and mentalizing capacity, they said.

“Future studies are needed to examine the antiaggressive effects of a more intensive and more targeted social cognition intervention combined with CRT,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and the Weill Cornell Clinical and Translational Science Award Program, National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Aggressive behavior, including verbal or physical threats or violent acts, is at least four times more likely among individuals with schizophrenia, compared with the general population, wrote Anzalee Khan, PhD, of the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, Orangeburg, N.Y., and colleagues. Recent studies suggest that psychosocial treatments such as cognitive remediation training (CRT) or social cognition training (SCT) may be helpful, but the potential benefit of combining these strategies has not been explored, they said.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research , the authors randomized 62 adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder to 36 sessions of a combination treatment with cognitive remediation and social cognition; 68 were randomized to cognitive remediation and computer-based control treatment. Participants also had at least one confirmed assault in the past year, or scores of 5 or higher on the Life History of Aggression scale. Complete data were analyzed for 45 patients in the CRT/SRT group and 34 in the CRT control group.

The primary outcome was the measure of aggression using the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (OAS-M) in which higher scores indicate higher levels of aggression. Incidents of aggression were coded based on hospital staff reports and summarized weekly. The mean age of the participants was 34.9 years (ranging from 18 to 60 years), 85% were male, and the mean years of education was 11.5.

At the study’s end (14 weeks), participants in both groups showed significant reductions in measures of aggression from baseline, with the largest effect size for the total global OAS-M score (effect size 1.11 for CRT plus SCT and 0.73 for the CRT plus control group).

The results failed to confirm the hypothesis that the combination of CRT and SCT would significantly increase improvements in aggression compared with CRT alone, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Potential reasons include underdosed SCT intervention (only 12 sessions) and the nature of the SCT used in the study, which had few aggressive social interaction models and more models related to social engagement.

Although adding SCT did not have a significant impact on aggression, patients in the CRT plus SCT group showed greater improvement in cognitive function, emotion recognition, and mentalizing, compared with the controls without SCT, the researchers noted.

“While these findings are not surprising given that participants in the CRT plus SCT group received active social cognition training, they do support the idea that social cognition training may have contributed to further strengthen our effect on cognition,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors including the study population of individuals with chronic schizophrenia and low levels of function in long-term tertiary care, which may limit generalizability, and the inability to control for the effects of pharmacotherapy, the researchers said.

However, the results were strengthened by the multidimensional assessments at both time points and the use of two cognitive and social cognition interventions, and suggest that adding social cognitive training enhanced the effect of CRT on cognitive function, emotion regulation, and mentalizing capacity, they said.

“Future studies are needed to examine the antiaggressive effects of a more intensive and more targeted social cognition intervention combined with CRT,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and the Weill Cornell Clinical and Translational Science Award Program, National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SCHIZOPHRENIA RESEARCH