User login

Enzymatic injections show durable improvement in buttock cellulite

follow-up in an ongoing, 5-year, phase 3b, open-label extension study, Michael H. Gold, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

However, outcomes in that study, as well as in the earlier pivotal trials, were assessed via physician and patient subjective assessments of aesthetic appearance. In a separate presentation at the conference, Michael S. Kaminer, MD, presented a different study evaluating the objective quantifiable effects of CCH on buttock cellulite dimple volume using three-dimensional imaging. The results, indicating that smaller cellulite dimples responded better than larger dimples, he noted, were unexpected.

Discussant Zoe D. Draelos, MD, who practices in High Point, N.C., and is a consulting professor of dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., put the two studies in perspective, explaining that there are multiple challenges associated with the use of CCH to treat buttock cellulite, and dermatologists need to understand them in order to maximize the benefit.

“There’s definitely a market for this therapy,” she observed, noting the plethora of over-the-counter products and devices sold for removal of cellulite. “I think if you manage patient expectations, this will be a very, very successful procedure.”

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved subcutaneous injections of CCH (marketed under the brand name QWO) for treatment of cellulite in women’s buttocks on the basis of the randomized RELEASE-1 and -2 trials. But while this is a new indication for CCH, it is not a new drug. The medication has been approved for years for treatment of fibrotic band contracture disorders, namely Dupuytren’s contracture and Peyronie’s disease. The mechanism of action for treatment of cellulite involves a process dubbed enzymatic subcision, in which CCH breaks down mature collagen and stimulates new collagen formation and fat redistribution in an effort to achieve smoother skin contour.

“This adds a whole new wrinkle to injectables available in dermatology. We have fillers, we have toxins, and now we have enzymatic subcision,” Dr. Draelos commented.

Durability of effects

Dr. Gold, founder of the Gold Skin Care Center and at the Tennessee Clinical Research Center, Nashville, reported on 483 women with moderate to severe buttock cellulitis who completed the 71-day, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 RELEASE-1 or RELEASE-2 studies and then enrolled in the open-label extension study. At the end of the randomized trial, 61.7% of women experienced at least a 1-level improvement on the Patient-Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (PR-PCSS), compared with 36.7% of placebo controls. The key finding in the interim analysis of the extension study: After the first 6 months, during which no one received any additional therapy, 52.7% of the CCH group still had at least a 1-level improvement in PR-PCSS, compared with the randomized trial baseline, as did 32.6% of controls.

Similarly, 63% of CCH-treated patients showed at least a 1-level improvement in the Clinician-Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (CR-PCSS) from baseline to the end of the randomized trial, and 52.7% met that standard after 6 months off treatment in the open-label extension. In contrast, the control group had response rates of 36.7% and 32.6%. There were no long-term safety concerns, according to Dr. Gold.

Measuring cellulite dimple volume shrinkage

Dr. Kaminer and coinvestigators measured the change in cellulite dimple volume from baseline to 30 days after the final injection of 33 buttock dimples in 27 women in order to get a quantifiable sense of the effectiveness of the CCH injection. To their surprise, smaller-volume dimples up to 118 mm3 showed a mean 43% reduction in volume, a significantly better result than the 15.8% reduction seen in dimples greater than 118 mm3.

“That’s almost counterintuitive, right? You’d think that larger dimples would have a bigger improvement, but it turns out that the smaller dimples do better,” he said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

Also, cellulite dimples in women age 40 and under responded significantly better than those in older women, added Dr. Kaminer, a dermatologist in private practice in Chestnut Hill, Mass., who is also on the faculty at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Challenges in using CCH therapy

Dr. Draelos, who is familiar with CCH, having worked on some earlier studies of the product, commented that “this is really the first medical treatment for cellulite that’s been proven to work.”

That being said, there are challenges with this therapy. While roughly 53% of women rated themselves as having at least a 1-level improvement after 6 months of follow-up, so did 33% of placebo-treated controls, for a placebo-subtracted 20% response.

“Is a 1-grade improvement going to be enough for women to engage in this procedure? You do need to remember that it takes multiple injections: most need at least three injections to see durable impact. And there’s discomfort during the procedure and afterwards during the healing process because the mechanism of action is enzymatic. You’re breaking down fibrous bands, and that’s a proinflammatory process. Many women who undergo this procedure may have discomfort and bruising, and they should be warned that this is not a procedure to do before taking a cruise or wearing a bikini. Also, it’s important to note that many women will have discomfort in the area where they sit, so if they have a job where they need to be sitting for long periods of time they need to plan their activities around this particular procedure,” the dermatologist said.

Another consideration: “The area they actually studied – the buttocks – is an area where I’m not sure a lot of women would expose their skin in public. I think thigh dimpling is more bothersome because it shows in shorts and other types of clothing. We need to figure out if the injections work on the posterior thighs, the most common place most postpubertal women get cellulite,” Dr. Draelos noted.

She wasn’t surprised that smaller cellulite dimples did better. Larger dimples presumably have a broader fibrous attachment and tighter fibrous band. She found the less robust outcomes in women over age 40 similarly unsurprising, since cellulitis seems to worsen with age. Cellulitis can’t really be called a disease, anyway, since it occurs in about 90% of postpubertal women.

One last tip about managing patient expectations: “Let a woman know that it’ll be better, but it won’t be gone,” she said.

Dr. Gold and Dr. Kaminer reported serving as paid investigators for and consultants to Endo Pharmaceuticals, the study sponsor and manufacturer of CCH, as well as for several other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

follow-up in an ongoing, 5-year, phase 3b, open-label extension study, Michael H. Gold, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

However, outcomes in that study, as well as in the earlier pivotal trials, were assessed via physician and patient subjective assessments of aesthetic appearance. In a separate presentation at the conference, Michael S. Kaminer, MD, presented a different study evaluating the objective quantifiable effects of CCH on buttock cellulite dimple volume using three-dimensional imaging. The results, indicating that smaller cellulite dimples responded better than larger dimples, he noted, were unexpected.

Discussant Zoe D. Draelos, MD, who practices in High Point, N.C., and is a consulting professor of dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., put the two studies in perspective, explaining that there are multiple challenges associated with the use of CCH to treat buttock cellulite, and dermatologists need to understand them in order to maximize the benefit.

“There’s definitely a market for this therapy,” she observed, noting the plethora of over-the-counter products and devices sold for removal of cellulite. “I think if you manage patient expectations, this will be a very, very successful procedure.”

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved subcutaneous injections of CCH (marketed under the brand name QWO) for treatment of cellulite in women’s buttocks on the basis of the randomized RELEASE-1 and -2 trials. But while this is a new indication for CCH, it is not a new drug. The medication has been approved for years for treatment of fibrotic band contracture disorders, namely Dupuytren’s contracture and Peyronie’s disease. The mechanism of action for treatment of cellulite involves a process dubbed enzymatic subcision, in which CCH breaks down mature collagen and stimulates new collagen formation and fat redistribution in an effort to achieve smoother skin contour.

“This adds a whole new wrinkle to injectables available in dermatology. We have fillers, we have toxins, and now we have enzymatic subcision,” Dr. Draelos commented.

Durability of effects

Dr. Gold, founder of the Gold Skin Care Center and at the Tennessee Clinical Research Center, Nashville, reported on 483 women with moderate to severe buttock cellulitis who completed the 71-day, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 RELEASE-1 or RELEASE-2 studies and then enrolled in the open-label extension study. At the end of the randomized trial, 61.7% of women experienced at least a 1-level improvement on the Patient-Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (PR-PCSS), compared with 36.7% of placebo controls. The key finding in the interim analysis of the extension study: After the first 6 months, during which no one received any additional therapy, 52.7% of the CCH group still had at least a 1-level improvement in PR-PCSS, compared with the randomized trial baseline, as did 32.6% of controls.

Similarly, 63% of CCH-treated patients showed at least a 1-level improvement in the Clinician-Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (CR-PCSS) from baseline to the end of the randomized trial, and 52.7% met that standard after 6 months off treatment in the open-label extension. In contrast, the control group had response rates of 36.7% and 32.6%. There were no long-term safety concerns, according to Dr. Gold.

Measuring cellulite dimple volume shrinkage

Dr. Kaminer and coinvestigators measured the change in cellulite dimple volume from baseline to 30 days after the final injection of 33 buttock dimples in 27 women in order to get a quantifiable sense of the effectiveness of the CCH injection. To their surprise, smaller-volume dimples up to 118 mm3 showed a mean 43% reduction in volume, a significantly better result than the 15.8% reduction seen in dimples greater than 118 mm3.

“That’s almost counterintuitive, right? You’d think that larger dimples would have a bigger improvement, but it turns out that the smaller dimples do better,” he said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

Also, cellulite dimples in women age 40 and under responded significantly better than those in older women, added Dr. Kaminer, a dermatologist in private practice in Chestnut Hill, Mass., who is also on the faculty at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Challenges in using CCH therapy

Dr. Draelos, who is familiar with CCH, having worked on some earlier studies of the product, commented that “this is really the first medical treatment for cellulite that’s been proven to work.”

That being said, there are challenges with this therapy. While roughly 53% of women rated themselves as having at least a 1-level improvement after 6 months of follow-up, so did 33% of placebo-treated controls, for a placebo-subtracted 20% response.

“Is a 1-grade improvement going to be enough for women to engage in this procedure? You do need to remember that it takes multiple injections: most need at least three injections to see durable impact. And there’s discomfort during the procedure and afterwards during the healing process because the mechanism of action is enzymatic. You’re breaking down fibrous bands, and that’s a proinflammatory process. Many women who undergo this procedure may have discomfort and bruising, and they should be warned that this is not a procedure to do before taking a cruise or wearing a bikini. Also, it’s important to note that many women will have discomfort in the area where they sit, so if they have a job where they need to be sitting for long periods of time they need to plan their activities around this particular procedure,” the dermatologist said.

Another consideration: “The area they actually studied – the buttocks – is an area where I’m not sure a lot of women would expose their skin in public. I think thigh dimpling is more bothersome because it shows in shorts and other types of clothing. We need to figure out if the injections work on the posterior thighs, the most common place most postpubertal women get cellulite,” Dr. Draelos noted.

She wasn’t surprised that smaller cellulite dimples did better. Larger dimples presumably have a broader fibrous attachment and tighter fibrous band. She found the less robust outcomes in women over age 40 similarly unsurprising, since cellulitis seems to worsen with age. Cellulitis can’t really be called a disease, anyway, since it occurs in about 90% of postpubertal women.

One last tip about managing patient expectations: “Let a woman know that it’ll be better, but it won’t be gone,” she said.

Dr. Gold and Dr. Kaminer reported serving as paid investigators for and consultants to Endo Pharmaceuticals, the study sponsor and manufacturer of CCH, as well as for several other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

follow-up in an ongoing, 5-year, phase 3b, open-label extension study, Michael H. Gold, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

However, outcomes in that study, as well as in the earlier pivotal trials, were assessed via physician and patient subjective assessments of aesthetic appearance. In a separate presentation at the conference, Michael S. Kaminer, MD, presented a different study evaluating the objective quantifiable effects of CCH on buttock cellulite dimple volume using three-dimensional imaging. The results, indicating that smaller cellulite dimples responded better than larger dimples, he noted, were unexpected.

Discussant Zoe D. Draelos, MD, who practices in High Point, N.C., and is a consulting professor of dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., put the two studies in perspective, explaining that there are multiple challenges associated with the use of CCH to treat buttock cellulite, and dermatologists need to understand them in order to maximize the benefit.

“There’s definitely a market for this therapy,” she observed, noting the plethora of over-the-counter products and devices sold for removal of cellulite. “I think if you manage patient expectations, this will be a very, very successful procedure.”

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved subcutaneous injections of CCH (marketed under the brand name QWO) for treatment of cellulite in women’s buttocks on the basis of the randomized RELEASE-1 and -2 trials. But while this is a new indication for CCH, it is not a new drug. The medication has been approved for years for treatment of fibrotic band contracture disorders, namely Dupuytren’s contracture and Peyronie’s disease. The mechanism of action for treatment of cellulite involves a process dubbed enzymatic subcision, in which CCH breaks down mature collagen and stimulates new collagen formation and fat redistribution in an effort to achieve smoother skin contour.

“This adds a whole new wrinkle to injectables available in dermatology. We have fillers, we have toxins, and now we have enzymatic subcision,” Dr. Draelos commented.

Durability of effects

Dr. Gold, founder of the Gold Skin Care Center and at the Tennessee Clinical Research Center, Nashville, reported on 483 women with moderate to severe buttock cellulitis who completed the 71-day, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 RELEASE-1 or RELEASE-2 studies and then enrolled in the open-label extension study. At the end of the randomized trial, 61.7% of women experienced at least a 1-level improvement on the Patient-Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (PR-PCSS), compared with 36.7% of placebo controls. The key finding in the interim analysis of the extension study: After the first 6 months, during which no one received any additional therapy, 52.7% of the CCH group still had at least a 1-level improvement in PR-PCSS, compared with the randomized trial baseline, as did 32.6% of controls.

Similarly, 63% of CCH-treated patients showed at least a 1-level improvement in the Clinician-Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (CR-PCSS) from baseline to the end of the randomized trial, and 52.7% met that standard after 6 months off treatment in the open-label extension. In contrast, the control group had response rates of 36.7% and 32.6%. There were no long-term safety concerns, according to Dr. Gold.

Measuring cellulite dimple volume shrinkage

Dr. Kaminer and coinvestigators measured the change in cellulite dimple volume from baseline to 30 days after the final injection of 33 buttock dimples in 27 women in order to get a quantifiable sense of the effectiveness of the CCH injection. To their surprise, smaller-volume dimples up to 118 mm3 showed a mean 43% reduction in volume, a significantly better result than the 15.8% reduction seen in dimples greater than 118 mm3.

“That’s almost counterintuitive, right? You’d think that larger dimples would have a bigger improvement, but it turns out that the smaller dimples do better,” he said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

Also, cellulite dimples in women age 40 and under responded significantly better than those in older women, added Dr. Kaminer, a dermatologist in private practice in Chestnut Hill, Mass., who is also on the faculty at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Challenges in using CCH therapy

Dr. Draelos, who is familiar with CCH, having worked on some earlier studies of the product, commented that “this is really the first medical treatment for cellulite that’s been proven to work.”

That being said, there are challenges with this therapy. While roughly 53% of women rated themselves as having at least a 1-level improvement after 6 months of follow-up, so did 33% of placebo-treated controls, for a placebo-subtracted 20% response.

“Is a 1-grade improvement going to be enough for women to engage in this procedure? You do need to remember that it takes multiple injections: most need at least three injections to see durable impact. And there’s discomfort during the procedure and afterwards during the healing process because the mechanism of action is enzymatic. You’re breaking down fibrous bands, and that’s a proinflammatory process. Many women who undergo this procedure may have discomfort and bruising, and they should be warned that this is not a procedure to do before taking a cruise or wearing a bikini. Also, it’s important to note that many women will have discomfort in the area where they sit, so if they have a job where they need to be sitting for long periods of time they need to plan their activities around this particular procedure,” the dermatologist said.

Another consideration: “The area they actually studied – the buttocks – is an area where I’m not sure a lot of women would expose their skin in public. I think thigh dimpling is more bothersome because it shows in shorts and other types of clothing. We need to figure out if the injections work on the posterior thighs, the most common place most postpubertal women get cellulite,” Dr. Draelos noted.

She wasn’t surprised that smaller cellulite dimples did better. Larger dimples presumably have a broader fibrous attachment and tighter fibrous band. She found the less robust outcomes in women over age 40 similarly unsurprising, since cellulitis seems to worsen with age. Cellulitis can’t really be called a disease, anyway, since it occurs in about 90% of postpubertal women.

One last tip about managing patient expectations: “Let a woman know that it’ll be better, but it won’t be gone,” she said.

Dr. Gold and Dr. Kaminer reported serving as paid investigators for and consultants to Endo Pharmaceuticals, the study sponsor and manufacturer of CCH, as well as for several other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

The Zoom effect on cosmetic procedures

As clinics were allowed to reopen under local government guidelines several months into the COVID-19 pandemic, many cosmetic dermatologists and aesthetic surgeons had no idea what our schedules would be like. .

While scheduled appointments, no shows, cancellations, and rebookings seem to wax and wane with surges in COVID-19 cases locally and with associated media coverage, there appear to be several reasons why demand has increased. Because people are wearing masks, they can easily hide signs of recovery or “something new” in their appearance. Patients aren’t typically around as many people and have more time to recover in private. There is also the positive effect a procedure can have on mood and self-esteem during what has been a difficult year. And people have had more time to read beauty and self-care articles, as well as advertisements for skin and hair care on social media.

The Zoom effect

One reason I did not anticipate is the Zoom effect. I don’t intend to single out Zoom – as there are other videoconferencing options available – but it seems to be the one patients bring up the most. Virtual meetings, conferences, and social events, and video calls with loved ones have become a part of daily routines for many, who are now seeing themselves on camera during these interactions as they never did before. It has created a strange new phenomenon.

Patients have literally said to me “I don’t like the way I look on Zoom” and ask about options to improve what they are seeing. They are often surprised to see that their appearance on virtual meetings, for example, does not reflect the way they feel inside, or how they think they should look. Even medical dermatology patients who have had no interest in cosmetic procedures previously have been coming in for this specific reason – both female and male patients.

Since photography is a hobby, I counsel patients that lighting and shadows play a huge role in how they appear on screen. Depending on the lighting, camera angle, and camera quality, suboptimal lighting can highlight shadows and wrinkles not normally seen in natural or optimal light. In a recent interview on KCRW, the Los Angeles NPR affiliate station, the founding director of the Virtual Human Interaction Lab (VHIL) at Stanford University highlighted work on the effect that Zoom and virtual interactions have had on people during the COVID-19 pandemic. He notes that during a normal in-person meeting or conference, attention is usually on the person speaking, but now with everyone on camera at once, people have the pressure and subsequent feelings of exhaustion (a different type of exhaustion than being there in person) of being seen at all times. To address “Zoom Fatigue,” the VHIL’s recommendations include turning off the camera periodically, or changing the settings so your image is not seen. Another option is to use background filters, including some face filters (a cat for example), which Zoom has created to ease some of the stress of these meetings.

Back to the actual in-person office visits: In my experience, all cosmetic procedures across the board, including injectables, skin resurfacing, and lasers have increased. In Dr. Talakoub’s practice, she has noted a tenfold increase in the use of deoxycholic acid (Kybella) and neck procedures attributed to the unflattering angle of the neck as people look down on their computer screens.There has also been an increase in the use of other injectables, such as Botox of the glabella to address scowling at the screen, facial fillers to address the dark shadows cast on the tear troughs, and lip fillers (noted to be 10-20 times higher) because of masks that can hide healing downtime. Similarly, increased use of Coolsculpting has been noted, as some patients have the flexibility of being able to take their Zoom meetings during the procedure, when they otherwise may not have had the time. Some patients have told me that the appointment with me is the only visit they’ve made outside of their home during the pandemic. Once the consultations or procedures are completed, patients often show gratitude and their self-esteem is increased. Some patients have said they even feel better and more productive at work, or note more positive interactions with their loved ones after the work has been done, likely because they feel better about themselves.There have been discussions about the benefits people have in being able to use Zoom and other videoconferencing platforms to gather and create, as well as see people and communicate in a way that can sometimes be more effective than a phone call. As physicians, these virtual tools have also allowed us to provide telehealth visits, a flexible, safe, and comfortable option for both the patient and practitioner. If done in a safe place, the ability to see each other without wearing a mask is also a nice treat.

The gratification and improvement in psyche that patients experience after our visits during this unprecedented, challenging time has been evident. Perhaps it’s the social interaction with their trusted physician, the outcome of the procedure itself, or a combination of both, which has a net positive effect on the physician-patient relationship.

While cosmetic procedures are appropriately deemed elective by hospital facilities and practitioners and should be of lower importance with regard to use of available facilities and PPE than those related to COVID-19 and other life-threatening scenarios, the longevity of this pandemic has surprisingly highlighted the numerous ways in which cosmetic visits can help patients, and the importance of being able to be there for patients – in a safe manner for all involved.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

As clinics were allowed to reopen under local government guidelines several months into the COVID-19 pandemic, many cosmetic dermatologists and aesthetic surgeons had no idea what our schedules would be like. .

While scheduled appointments, no shows, cancellations, and rebookings seem to wax and wane with surges in COVID-19 cases locally and with associated media coverage, there appear to be several reasons why demand has increased. Because people are wearing masks, they can easily hide signs of recovery or “something new” in their appearance. Patients aren’t typically around as many people and have more time to recover in private. There is also the positive effect a procedure can have on mood and self-esteem during what has been a difficult year. And people have had more time to read beauty and self-care articles, as well as advertisements for skin and hair care on social media.

The Zoom effect

One reason I did not anticipate is the Zoom effect. I don’t intend to single out Zoom – as there are other videoconferencing options available – but it seems to be the one patients bring up the most. Virtual meetings, conferences, and social events, and video calls with loved ones have become a part of daily routines for many, who are now seeing themselves on camera during these interactions as they never did before. It has created a strange new phenomenon.

Patients have literally said to me “I don’t like the way I look on Zoom” and ask about options to improve what they are seeing. They are often surprised to see that their appearance on virtual meetings, for example, does not reflect the way they feel inside, or how they think they should look. Even medical dermatology patients who have had no interest in cosmetic procedures previously have been coming in for this specific reason – both female and male patients.

Since photography is a hobby, I counsel patients that lighting and shadows play a huge role in how they appear on screen. Depending on the lighting, camera angle, and camera quality, suboptimal lighting can highlight shadows and wrinkles not normally seen in natural or optimal light. In a recent interview on KCRW, the Los Angeles NPR affiliate station, the founding director of the Virtual Human Interaction Lab (VHIL) at Stanford University highlighted work on the effect that Zoom and virtual interactions have had on people during the COVID-19 pandemic. He notes that during a normal in-person meeting or conference, attention is usually on the person speaking, but now with everyone on camera at once, people have the pressure and subsequent feelings of exhaustion (a different type of exhaustion than being there in person) of being seen at all times. To address “Zoom Fatigue,” the VHIL’s recommendations include turning off the camera periodically, or changing the settings so your image is not seen. Another option is to use background filters, including some face filters (a cat for example), which Zoom has created to ease some of the stress of these meetings.

Back to the actual in-person office visits: In my experience, all cosmetic procedures across the board, including injectables, skin resurfacing, and lasers have increased. In Dr. Talakoub’s practice, she has noted a tenfold increase in the use of deoxycholic acid (Kybella) and neck procedures attributed to the unflattering angle of the neck as people look down on their computer screens.There has also been an increase in the use of other injectables, such as Botox of the glabella to address scowling at the screen, facial fillers to address the dark shadows cast on the tear troughs, and lip fillers (noted to be 10-20 times higher) because of masks that can hide healing downtime. Similarly, increased use of Coolsculpting has been noted, as some patients have the flexibility of being able to take their Zoom meetings during the procedure, when they otherwise may not have had the time. Some patients have told me that the appointment with me is the only visit they’ve made outside of their home during the pandemic. Once the consultations or procedures are completed, patients often show gratitude and their self-esteem is increased. Some patients have said they even feel better and more productive at work, or note more positive interactions with their loved ones after the work has been done, likely because they feel better about themselves.There have been discussions about the benefits people have in being able to use Zoom and other videoconferencing platforms to gather and create, as well as see people and communicate in a way that can sometimes be more effective than a phone call. As physicians, these virtual tools have also allowed us to provide telehealth visits, a flexible, safe, and comfortable option for both the patient and practitioner. If done in a safe place, the ability to see each other without wearing a mask is also a nice treat.

The gratification and improvement in psyche that patients experience after our visits during this unprecedented, challenging time has been evident. Perhaps it’s the social interaction with their trusted physician, the outcome of the procedure itself, or a combination of both, which has a net positive effect on the physician-patient relationship.

While cosmetic procedures are appropriately deemed elective by hospital facilities and practitioners and should be of lower importance with regard to use of available facilities and PPE than those related to COVID-19 and other life-threatening scenarios, the longevity of this pandemic has surprisingly highlighted the numerous ways in which cosmetic visits can help patients, and the importance of being able to be there for patients – in a safe manner for all involved.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

As clinics were allowed to reopen under local government guidelines several months into the COVID-19 pandemic, many cosmetic dermatologists and aesthetic surgeons had no idea what our schedules would be like. .

While scheduled appointments, no shows, cancellations, and rebookings seem to wax and wane with surges in COVID-19 cases locally and with associated media coverage, there appear to be several reasons why demand has increased. Because people are wearing masks, they can easily hide signs of recovery or “something new” in their appearance. Patients aren’t typically around as many people and have more time to recover in private. There is also the positive effect a procedure can have on mood and self-esteem during what has been a difficult year. And people have had more time to read beauty and self-care articles, as well as advertisements for skin and hair care on social media.

The Zoom effect

One reason I did not anticipate is the Zoom effect. I don’t intend to single out Zoom – as there are other videoconferencing options available – but it seems to be the one patients bring up the most. Virtual meetings, conferences, and social events, and video calls with loved ones have become a part of daily routines for many, who are now seeing themselves on camera during these interactions as they never did before. It has created a strange new phenomenon.

Patients have literally said to me “I don’t like the way I look on Zoom” and ask about options to improve what they are seeing. They are often surprised to see that their appearance on virtual meetings, for example, does not reflect the way they feel inside, or how they think they should look. Even medical dermatology patients who have had no interest in cosmetic procedures previously have been coming in for this specific reason – both female and male patients.

Since photography is a hobby, I counsel patients that lighting and shadows play a huge role in how they appear on screen. Depending on the lighting, camera angle, and camera quality, suboptimal lighting can highlight shadows and wrinkles not normally seen in natural or optimal light. In a recent interview on KCRW, the Los Angeles NPR affiliate station, the founding director of the Virtual Human Interaction Lab (VHIL) at Stanford University highlighted work on the effect that Zoom and virtual interactions have had on people during the COVID-19 pandemic. He notes that during a normal in-person meeting or conference, attention is usually on the person speaking, but now with everyone on camera at once, people have the pressure and subsequent feelings of exhaustion (a different type of exhaustion than being there in person) of being seen at all times. To address “Zoom Fatigue,” the VHIL’s recommendations include turning off the camera periodically, or changing the settings so your image is not seen. Another option is to use background filters, including some face filters (a cat for example), which Zoom has created to ease some of the stress of these meetings.

Back to the actual in-person office visits: In my experience, all cosmetic procedures across the board, including injectables, skin resurfacing, and lasers have increased. In Dr. Talakoub’s practice, she has noted a tenfold increase in the use of deoxycholic acid (Kybella) and neck procedures attributed to the unflattering angle of the neck as people look down on their computer screens.There has also been an increase in the use of other injectables, such as Botox of the glabella to address scowling at the screen, facial fillers to address the dark shadows cast on the tear troughs, and lip fillers (noted to be 10-20 times higher) because of masks that can hide healing downtime. Similarly, increased use of Coolsculpting has been noted, as some patients have the flexibility of being able to take their Zoom meetings during the procedure, when they otherwise may not have had the time. Some patients have told me that the appointment with me is the only visit they’ve made outside of their home during the pandemic. Once the consultations or procedures are completed, patients often show gratitude and their self-esteem is increased. Some patients have said they even feel better and more productive at work, or note more positive interactions with their loved ones after the work has been done, likely because they feel better about themselves.There have been discussions about the benefits people have in being able to use Zoom and other videoconferencing platforms to gather and create, as well as see people and communicate in a way that can sometimes be more effective than a phone call. As physicians, these virtual tools have also allowed us to provide telehealth visits, a flexible, safe, and comfortable option for both the patient and practitioner. If done in a safe place, the ability to see each other without wearing a mask is also a nice treat.

The gratification and improvement in psyche that patients experience after our visits during this unprecedented, challenging time has been evident. Perhaps it’s the social interaction with their trusted physician, the outcome of the procedure itself, or a combination of both, which has a net positive effect on the physician-patient relationship.

While cosmetic procedures are appropriately deemed elective by hospital facilities and practitioners and should be of lower importance with regard to use of available facilities and PPE than those related to COVID-19 and other life-threatening scenarios, the longevity of this pandemic has surprisingly highlighted the numerous ways in which cosmetic visits can help patients, and the importance of being able to be there for patients – in a safe manner for all involved.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

The cutaneous benefits of bee venom, Part II: Acupuncture, wound healing, and various potential indications

A wide range of products derived from bees, including honey, propolis, bee pollen, bee bread, royal jelly, beeswax, and bee venom, have been used since ancient times for medical purposes.1 Specifically, bee venom has been used in traditional medicine to treat multiple disorders, including arthritis, cancer, pain, rheumatism, and skin diseases.2,3 The primary active constituent of bee venom is melittin, an amphiphilic peptide containing 26 amino acid residues and known to impart anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, analgesic, and anticancer effects.4-7 Additional anti-inflammatory compounds found in bee venom include adolapin, apamin, and phospholipase A2; melittin and phospholipase A2 are also capable of delivering pro-inflammatory activity.8,9

The anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties of bee venom have been cited as justification for its use as a cosmetic ingredient.10 In experimental studies, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects have been reported.11 Bee venom phospholipase A2 has also demonstrated notable success in vitro and in vivo in conferring immunomodulatory effects and is a key component in past and continuing use of bee venom therapy for immune-related disorders, such as arthritis.12

A recent review of the biomedical literature by Nguyen et al. reveals that bee venom is one of the key ingredients in the booming Korean cosmeceuticals industry.13 Kim et al. reviewed the therapeutic applications of bee venom in 2019, noting that anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, antifibrotic, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties have been cited in experimental and clinical reports, with cutaneous treatments ranging from acne, alopecia, and atopic dermatitis to melanoma, morphea, photoaging, psoriasis, vitiligo, wounds, and wrinkles.14 This column focuses on the use of bee venom in acupuncture and wound healing, as well as some other potential applications of this bee product used for millennia.

Acupuncture

Bee venom acupuncture entails the application of bee venom to the tips of acupuncture needles, which are then applied to acupoints on the skin. Cherniack and Govorushko state that several small studies in humans show that bee venom acupuncture has been used effectively to treat various musculoskeletal and neurological conditions.8

In 2016, Sur et al. explored the effects of bee venom acupuncture on atopic dermatitis in a mouse model with lesions induced by trimellitic anhydride. Bee venom treatment was found to significantly ease inflammation, lesion thickness, and lymph node weight. Suppression of T-cell proliferation and infiltration, Th1 and Th2 cytokine synthesis, and interleukin (IL)-4 and immunoglobulin E (IgE) production was also noted.15

A case report by Hwang and Kim in 2018 described the successful use of bee venom acupuncture in the treatment of a 64-year-old Korean woman with circumscribed morphea resulting from systemic sclerosis. Subcutaneous bee venom acupuncture along the margins resolved pruritus through 2 months of follow-up.11

Wound healing

A study by Hozzein et al. in 2018 on protecting functional macrophages from apoptosis and improving Nrf2, Ang-1, and Tie-2 signaling in diabetic wound healing in mice revealed that bee venom supports immune function, thus promoting healing from diabetic wounds.(16) Previously, this team had shown that bee venom facilitates wound healing in diabetic mice by inhibiting the activation of transcription factor-3 and inducible nitric oxide synthase-mediated stress.17

In early 2020, Nakashima et al. reported their results showing that bee venom-derived phospholipase A2 augmented poly(I:C)-induced activation in human keratinocytes, suggesting that it could play a role in wound healing promotion through enhanced TLR3 responses.18

Alopecia

A 2016 study on the effect of bee venom on alopecia in C57BL/6 mice by Park et al. showed that the bee toxin dose-dependently stimulated proliferation of several growth factors, including fibroblast growth factors 2 and 7, as compared with the control group. Bee venom also suppressed transition from the anagen to catagen phases, nurtured hair growth, and presented the potential as a strong 5α-reductase inhibitor.19

Anticancer and anti-arthritic activity

In 2007, Son et al. reported that the various peptides (melittin, apamin, adolapin, the mast-cell-degranulating peptide), enzymes (i.e., phospholipase A2), as well as biologically active amines (i.e., histamine and epinephrine) and nonpeptide components in bee venom are thought to account for multiple pharmaceutical properties that yield anti-arthritis, antinociceptive, and anticancer effects.2

In 2019, Lim et al. determined that bee venom and melittin inhibited the growth and migration of melanoma cells (B16F10, A375SM, and SK-MEL-28) by downregulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways. They concluded that melittin has the potential for use in preventing and treating malignant melanoma.4

Phototoxicity

Heo et al. conducted phototoxicity and skin sensitization studies of bee venom, as well as a bee venom from which they removed phospholipase A2, and determined that both were nonphototoxic substances and did not act as sensitizers.20

Han et al. assessed the skin safety of bee venom on tests in healthy male Hartley guinea pigs in 2017 and found that bee venom application engendered no toxic reactions, including any signs of cutaneous phototoxicity or skin photosensitization, and is likely safe for inclusion as a topical skin care ingredient.10

Antiwrinkle activity

Han et al. also evaluated the beneficial effects of bee venom serum on facial wrinkles in a small study on humans (22 South Korean women between 30 and 49 years old), finding clinical improvements as seen through reductions in wrinkle count, average wrinkle depth, and total wrinkle area. The authors, noting that this was the first clinical study to assess the results of using bee venom cosmetics on facial skin, also cited the relative safety of the product, which presents nominal irritation potential, and acknowledged its present use in the cosmetics industry.21

Conclusion

Bees play a critical role in the web of life as they pollinate approximately one-third of our food. Perhaps counterintuitively, given our awareness of the painful and potentially serious reactions to bee stings, bee venom has also been found to deliver multiple salutary effects. More research is necessary to ascertain the viability of using bee venom as a reliable treatment for the various cutaneous conditions for which it demonstrates potential benefits. Current evidence presents justification for further investigation.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Kurek-Górecka A et al. Molecules. 2020 Jan 28;25(3):556.

2. Son DJ et al. Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Aug;115(2):246-70.

3. Lee G, Bae H. Molecules. 2016 May 11;21(5):616.

4. Lim HN et al. Molecules. 2019 Mar 7;24(5):929.

5. Gu H et al. Mol Med Rep. 2018 Oct;18(4):3711-8. 6. You CE et al. Ann Dermatol. 2016 Oct;28(5):593-9. 7. An HJ et al. Int J Mol Med. 2014 Nov;34(5):1341-8. 8. Cherniack EP, Govorushko S. Toxicon. 2018 Nov;154:74-8. 9. Cornara L et al. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 28;8:412.

10. Han SM et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Dec;16(4):e68-e75.

11. Hwang JH, Kim KH. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Dec;97(49):e13404. 12. Lee G, Bae H. Toxins (Basel). 2016 Feb 22;8(2):48. 13. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

14. Kim H et al. Toxins (Basel). 2019 Jun 27:11(7):374.

15. Sur B et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 Jan 29;16:38. 16. Hozzein WN et al. Mol Immunol. 2018 Nov;103:322-35. 17. Badr G et al. J Cell Physiol. 2016 Oct;231(10):2159-71. 18. Nakashima A et al. Int Immunol. 2020 May 30;32(6):371-83. 19. Park S et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016 Jun 1;39(6):1060-8.

20. Heo Y et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:157367. 21. Han SM et al. Clin Interv Aging. 2015 Oct 1;10:1587-92.

A wide range of products derived from bees, including honey, propolis, bee pollen, bee bread, royal jelly, beeswax, and bee venom, have been used since ancient times for medical purposes.1 Specifically, bee venom has been used in traditional medicine to treat multiple disorders, including arthritis, cancer, pain, rheumatism, and skin diseases.2,3 The primary active constituent of bee venom is melittin, an amphiphilic peptide containing 26 amino acid residues and known to impart anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, analgesic, and anticancer effects.4-7 Additional anti-inflammatory compounds found in bee venom include adolapin, apamin, and phospholipase A2; melittin and phospholipase A2 are also capable of delivering pro-inflammatory activity.8,9

The anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties of bee venom have been cited as justification for its use as a cosmetic ingredient.10 In experimental studies, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects have been reported.11 Bee venom phospholipase A2 has also demonstrated notable success in vitro and in vivo in conferring immunomodulatory effects and is a key component in past and continuing use of bee venom therapy for immune-related disorders, such as arthritis.12

A recent review of the biomedical literature by Nguyen et al. reveals that bee venom is one of the key ingredients in the booming Korean cosmeceuticals industry.13 Kim et al. reviewed the therapeutic applications of bee venom in 2019, noting that anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, antifibrotic, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties have been cited in experimental and clinical reports, with cutaneous treatments ranging from acne, alopecia, and atopic dermatitis to melanoma, morphea, photoaging, psoriasis, vitiligo, wounds, and wrinkles.14 This column focuses on the use of bee venom in acupuncture and wound healing, as well as some other potential applications of this bee product used for millennia.

Acupuncture

Bee venom acupuncture entails the application of bee venom to the tips of acupuncture needles, which are then applied to acupoints on the skin. Cherniack and Govorushko state that several small studies in humans show that bee venom acupuncture has been used effectively to treat various musculoskeletal and neurological conditions.8

In 2016, Sur et al. explored the effects of bee venom acupuncture on atopic dermatitis in a mouse model with lesions induced by trimellitic anhydride. Bee venom treatment was found to significantly ease inflammation, lesion thickness, and lymph node weight. Suppression of T-cell proliferation and infiltration, Th1 and Th2 cytokine synthesis, and interleukin (IL)-4 and immunoglobulin E (IgE) production was also noted.15

A case report by Hwang and Kim in 2018 described the successful use of bee venom acupuncture in the treatment of a 64-year-old Korean woman with circumscribed morphea resulting from systemic sclerosis. Subcutaneous bee venom acupuncture along the margins resolved pruritus through 2 months of follow-up.11

Wound healing

A study by Hozzein et al. in 2018 on protecting functional macrophages from apoptosis and improving Nrf2, Ang-1, and Tie-2 signaling in diabetic wound healing in mice revealed that bee venom supports immune function, thus promoting healing from diabetic wounds.(16) Previously, this team had shown that bee venom facilitates wound healing in diabetic mice by inhibiting the activation of transcription factor-3 and inducible nitric oxide synthase-mediated stress.17

In early 2020, Nakashima et al. reported their results showing that bee venom-derived phospholipase A2 augmented poly(I:C)-induced activation in human keratinocytes, suggesting that it could play a role in wound healing promotion through enhanced TLR3 responses.18

Alopecia

A 2016 study on the effect of bee venom on alopecia in C57BL/6 mice by Park et al. showed that the bee toxin dose-dependently stimulated proliferation of several growth factors, including fibroblast growth factors 2 and 7, as compared with the control group. Bee venom also suppressed transition from the anagen to catagen phases, nurtured hair growth, and presented the potential as a strong 5α-reductase inhibitor.19

Anticancer and anti-arthritic activity

In 2007, Son et al. reported that the various peptides (melittin, apamin, adolapin, the mast-cell-degranulating peptide), enzymes (i.e., phospholipase A2), as well as biologically active amines (i.e., histamine and epinephrine) and nonpeptide components in bee venom are thought to account for multiple pharmaceutical properties that yield anti-arthritis, antinociceptive, and anticancer effects.2

In 2019, Lim et al. determined that bee venom and melittin inhibited the growth and migration of melanoma cells (B16F10, A375SM, and SK-MEL-28) by downregulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways. They concluded that melittin has the potential for use in preventing and treating malignant melanoma.4

Phototoxicity

Heo et al. conducted phototoxicity and skin sensitization studies of bee venom, as well as a bee venom from which they removed phospholipase A2, and determined that both were nonphototoxic substances and did not act as sensitizers.20

Han et al. assessed the skin safety of bee venom on tests in healthy male Hartley guinea pigs in 2017 and found that bee venom application engendered no toxic reactions, including any signs of cutaneous phototoxicity or skin photosensitization, and is likely safe for inclusion as a topical skin care ingredient.10

Antiwrinkle activity

Han et al. also evaluated the beneficial effects of bee venom serum on facial wrinkles in a small study on humans (22 South Korean women between 30 and 49 years old), finding clinical improvements as seen through reductions in wrinkle count, average wrinkle depth, and total wrinkle area. The authors, noting that this was the first clinical study to assess the results of using bee venom cosmetics on facial skin, also cited the relative safety of the product, which presents nominal irritation potential, and acknowledged its present use in the cosmetics industry.21

Conclusion

Bees play a critical role in the web of life as they pollinate approximately one-third of our food. Perhaps counterintuitively, given our awareness of the painful and potentially serious reactions to bee stings, bee venom has also been found to deliver multiple salutary effects. More research is necessary to ascertain the viability of using bee venom as a reliable treatment for the various cutaneous conditions for which it demonstrates potential benefits. Current evidence presents justification for further investigation.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Kurek-Górecka A et al. Molecules. 2020 Jan 28;25(3):556.

2. Son DJ et al. Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Aug;115(2):246-70.

3. Lee G, Bae H. Molecules. 2016 May 11;21(5):616.

4. Lim HN et al. Molecules. 2019 Mar 7;24(5):929.

5. Gu H et al. Mol Med Rep. 2018 Oct;18(4):3711-8. 6. You CE et al. Ann Dermatol. 2016 Oct;28(5):593-9. 7. An HJ et al. Int J Mol Med. 2014 Nov;34(5):1341-8. 8. Cherniack EP, Govorushko S. Toxicon. 2018 Nov;154:74-8. 9. Cornara L et al. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 28;8:412.

10. Han SM et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Dec;16(4):e68-e75.

11. Hwang JH, Kim KH. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Dec;97(49):e13404. 12. Lee G, Bae H. Toxins (Basel). 2016 Feb 22;8(2):48. 13. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

14. Kim H et al. Toxins (Basel). 2019 Jun 27:11(7):374.

15. Sur B et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 Jan 29;16:38. 16. Hozzein WN et al. Mol Immunol. 2018 Nov;103:322-35. 17. Badr G et al. J Cell Physiol. 2016 Oct;231(10):2159-71. 18. Nakashima A et al. Int Immunol. 2020 May 30;32(6):371-83. 19. Park S et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016 Jun 1;39(6):1060-8.

20. Heo Y et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:157367. 21. Han SM et al. Clin Interv Aging. 2015 Oct 1;10:1587-92.

A wide range of products derived from bees, including honey, propolis, bee pollen, bee bread, royal jelly, beeswax, and bee venom, have been used since ancient times for medical purposes.1 Specifically, bee venom has been used in traditional medicine to treat multiple disorders, including arthritis, cancer, pain, rheumatism, and skin diseases.2,3 The primary active constituent of bee venom is melittin, an amphiphilic peptide containing 26 amino acid residues and known to impart anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, analgesic, and anticancer effects.4-7 Additional anti-inflammatory compounds found in bee venom include adolapin, apamin, and phospholipase A2; melittin and phospholipase A2 are also capable of delivering pro-inflammatory activity.8,9

The anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties of bee venom have been cited as justification for its use as a cosmetic ingredient.10 In experimental studies, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects have been reported.11 Bee venom phospholipase A2 has also demonstrated notable success in vitro and in vivo in conferring immunomodulatory effects and is a key component in past and continuing use of bee venom therapy for immune-related disorders, such as arthritis.12

A recent review of the biomedical literature by Nguyen et al. reveals that bee venom is one of the key ingredients in the booming Korean cosmeceuticals industry.13 Kim et al. reviewed the therapeutic applications of bee venom in 2019, noting that anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, antifibrotic, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties have been cited in experimental and clinical reports, with cutaneous treatments ranging from acne, alopecia, and atopic dermatitis to melanoma, morphea, photoaging, psoriasis, vitiligo, wounds, and wrinkles.14 This column focuses on the use of bee venom in acupuncture and wound healing, as well as some other potential applications of this bee product used for millennia.

Acupuncture

Bee venom acupuncture entails the application of bee venom to the tips of acupuncture needles, which are then applied to acupoints on the skin. Cherniack and Govorushko state that several small studies in humans show that bee venom acupuncture has been used effectively to treat various musculoskeletal and neurological conditions.8

In 2016, Sur et al. explored the effects of bee venom acupuncture on atopic dermatitis in a mouse model with lesions induced by trimellitic anhydride. Bee venom treatment was found to significantly ease inflammation, lesion thickness, and lymph node weight. Suppression of T-cell proliferation and infiltration, Th1 and Th2 cytokine synthesis, and interleukin (IL)-4 and immunoglobulin E (IgE) production was also noted.15

A case report by Hwang and Kim in 2018 described the successful use of bee venom acupuncture in the treatment of a 64-year-old Korean woman with circumscribed morphea resulting from systemic sclerosis. Subcutaneous bee venom acupuncture along the margins resolved pruritus through 2 months of follow-up.11

Wound healing

A study by Hozzein et al. in 2018 on protecting functional macrophages from apoptosis and improving Nrf2, Ang-1, and Tie-2 signaling in diabetic wound healing in mice revealed that bee venom supports immune function, thus promoting healing from diabetic wounds.(16) Previously, this team had shown that bee venom facilitates wound healing in diabetic mice by inhibiting the activation of transcription factor-3 and inducible nitric oxide synthase-mediated stress.17

In early 2020, Nakashima et al. reported their results showing that bee venom-derived phospholipase A2 augmented poly(I:C)-induced activation in human keratinocytes, suggesting that it could play a role in wound healing promotion through enhanced TLR3 responses.18

Alopecia

A 2016 study on the effect of bee venom on alopecia in C57BL/6 mice by Park et al. showed that the bee toxin dose-dependently stimulated proliferation of several growth factors, including fibroblast growth factors 2 and 7, as compared with the control group. Bee venom also suppressed transition from the anagen to catagen phases, nurtured hair growth, and presented the potential as a strong 5α-reductase inhibitor.19

Anticancer and anti-arthritic activity

In 2007, Son et al. reported that the various peptides (melittin, apamin, adolapin, the mast-cell-degranulating peptide), enzymes (i.e., phospholipase A2), as well as biologically active amines (i.e., histamine and epinephrine) and nonpeptide components in bee venom are thought to account for multiple pharmaceutical properties that yield anti-arthritis, antinociceptive, and anticancer effects.2

In 2019, Lim et al. determined that bee venom and melittin inhibited the growth and migration of melanoma cells (B16F10, A375SM, and SK-MEL-28) by downregulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways. They concluded that melittin has the potential for use in preventing and treating malignant melanoma.4

Phototoxicity

Heo et al. conducted phototoxicity and skin sensitization studies of bee venom, as well as a bee venom from which they removed phospholipase A2, and determined that both were nonphototoxic substances and did not act as sensitizers.20

Han et al. assessed the skin safety of bee venom on tests in healthy male Hartley guinea pigs in 2017 and found that bee venom application engendered no toxic reactions, including any signs of cutaneous phototoxicity or skin photosensitization, and is likely safe for inclusion as a topical skin care ingredient.10

Antiwrinkle activity

Han et al. also evaluated the beneficial effects of bee venom serum on facial wrinkles in a small study on humans (22 South Korean women between 30 and 49 years old), finding clinical improvements as seen through reductions in wrinkle count, average wrinkle depth, and total wrinkle area. The authors, noting that this was the first clinical study to assess the results of using bee venom cosmetics on facial skin, also cited the relative safety of the product, which presents nominal irritation potential, and acknowledged its present use in the cosmetics industry.21

Conclusion

Bees play a critical role in the web of life as they pollinate approximately one-third of our food. Perhaps counterintuitively, given our awareness of the painful and potentially serious reactions to bee stings, bee venom has also been found to deliver multiple salutary effects. More research is necessary to ascertain the viability of using bee venom as a reliable treatment for the various cutaneous conditions for which it demonstrates potential benefits. Current evidence presents justification for further investigation.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Kurek-Górecka A et al. Molecules. 2020 Jan 28;25(3):556.

2. Son DJ et al. Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Aug;115(2):246-70.

3. Lee G, Bae H. Molecules. 2016 May 11;21(5):616.

4. Lim HN et al. Molecules. 2019 Mar 7;24(5):929.

5. Gu H et al. Mol Med Rep. 2018 Oct;18(4):3711-8. 6. You CE et al. Ann Dermatol. 2016 Oct;28(5):593-9. 7. An HJ et al. Int J Mol Med. 2014 Nov;34(5):1341-8. 8. Cherniack EP, Govorushko S. Toxicon. 2018 Nov;154:74-8. 9. Cornara L et al. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 28;8:412.

10. Han SM et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Dec;16(4):e68-e75.

11. Hwang JH, Kim KH. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Dec;97(49):e13404. 12. Lee G, Bae H. Toxins (Basel). 2016 Feb 22;8(2):48. 13. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

14. Kim H et al. Toxins (Basel). 2019 Jun 27:11(7):374.

15. Sur B et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 Jan 29;16:38. 16. Hozzein WN et al. Mol Immunol. 2018 Nov;103:322-35. 17. Badr G et al. J Cell Physiol. 2016 Oct;231(10):2159-71. 18. Nakashima A et al. Int Immunol. 2020 May 30;32(6):371-83. 19. Park S et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016 Jun 1;39(6):1060-8.

20. Heo Y et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:157367. 21. Han SM et al. Clin Interv Aging. 2015 Oct 1;10:1587-92.

Upper Lip Anatomy, Mechanics of Local Flaps, and Considerations for Reconstruction

The upper lip poses challenges during reconstruction. Distortion of well-defined anatomic structures, including the vermilion border, oral commissures, Cupid’s bow, and philtrum, leads to noticeable deformities. Furthermore, maintenance of upper and lower lip function is essential for verbal communication, facial expression, and controlled opening of the oral cavity.

Similar to a prior review focused on the lower lip,1 we conducted a review of the literature using the PubMed database (1976-2017) and the following search terms: upper lip, lower lip, anatomy, comparison, cadaver, histology, local flap, and reconstruction. We reviewed studies that assessed anatomic and histologic characteristics of the upper and the lower lips, function of the upper lip, mechanics of local flaps, and upper lip reconstruction techniques including local flaps and regional flaps. Articles with an emphasis on free flaps were excluded.

The initial search resulted in 1326 articles. Of these, 1201 were excluded after abstracts were screened. Full-text review of the remaining 125 articles resulted in exclusion of 85 papers (9 foreign language, 4 duplicates, and 72 irrelevant). Among the 40 articles eligible for inclusion, 12 articles discussed anatomy and histology of the upper lip, 9 examined function of the upper lip, and 19 reviewed available techniques for reconstruction of the upper lip.

In this article, we review the anatomy and function of the upper lip as well as various repair techniques to provide the reconstructive surgeon with greater familiarity with the local flaps and an algorithmic approach for upper lip reconstruction.

Anatomic Characteristics of the Upper Lip

The muscular component of the upper lip primarily is comprised of the orbicularis oris (OO) muscle divided into 2 distinct concentric components: pars peripheralis and pars marginalis.2,3 It is discontinuous in some individuals.4 Although OO is the primary muscle of the lower lip, the upper lip is remarkably complex. Orbicularis oris and 3 additional muscles contribute to upper lip function: depressor septi nasi, the alar portion of the nasalis, and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN).5

The modiolus, a muscular structure located just lateral to the commissures, serves as a convergence point for facial muscle animation and lip function while distributing contraction forces between the lips and face.6 It is imperative to preserve its location in reconstruction to allow for good functional and aesthetic outcomes.

The upper lip is divided into 3 distinct aesthetic subunits: the philtrum and 1 lateral subunit on each side.7,8 Its unique surface features include the Cupid’s bow, vermilion tubercle, and philtral columns. The philtral columns are created by the dermal insertion on each side of the OO, which originates from the modiolus, decussates, and inserts into the skin of the contralateral philtral groove.2,9-11 The OO has additional insertions into the dermis lateral to the philtrum.5 During its course across the midline, it decreases its insertions, leading to the formation and thinness of the philtral dimple.9 The philtral shape primarily is due to the intermingling of LLSAN and the pars peripheralis in an axial plane. The LLSAN enters superolateral to the ipsilateral philtral ridge and courses along this ridge to contribute to the philtral shape.2 Formation of the philtrum’s contour arises from the opposing force of both muscles pulling the skin in opposite directions.2,5 The vermilion tubercle arises from the dermal insertion of the pars marginalis originating from the ipsilateral modiolus and follows the vermilion border.2 The Cupid’s bow is part of the white roll at the vermilion-cutaneous junction produced by the anterior projection of the pars peripheralis.10 The complex anatomy of this structure explains the intricacy of lip reconstructions in this area.

Function of the Upper Lip

Although the primary purpose of OO is sphincteric function, the upper lip’s key role is coverage of dentition and facial animation.12 The latter is achieved through the relationship of multiple muscles, including levator labii superioris, levator septi nasi, risorius, zygomaticus minor, zygomaticus major, levator anguli oris, and buccinator.7,13-17 Their smooth coordination results in various facial expressions. In comparison, the lower lip is critical for preservation of oral competence, prevention of drooling, eating, and speech due to the actions of OO and vertical support from the mentalis muscle.1,18-22

Reconstructive Methods for the Upper Lip

Multiple options are available for reconstruction of upper lip defects, with the aim to preserve facial animation and coverage of dentition. When animation muscles are involved, restoring function is the goal, which can be achieved by placing sutures to reapproximate the muscle edges in smaller defects or anchor the remaining muscle edge to preserve deep structures in larger defects, respecting the vector of contraction and attempting simulation of the muscle function. Additionally, restoration of the continuity of OO also is important for good aesthetic and functional outcomes.

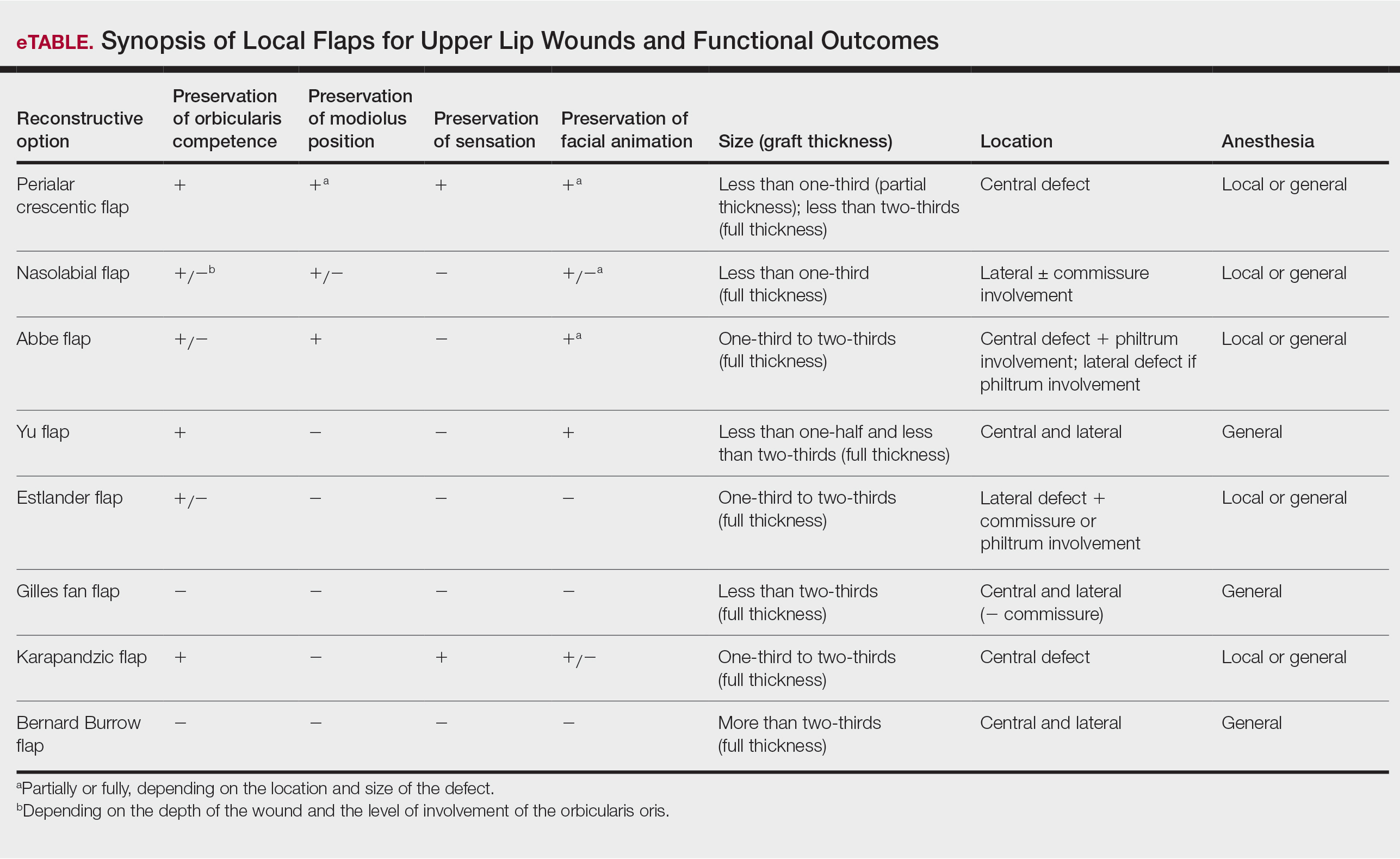

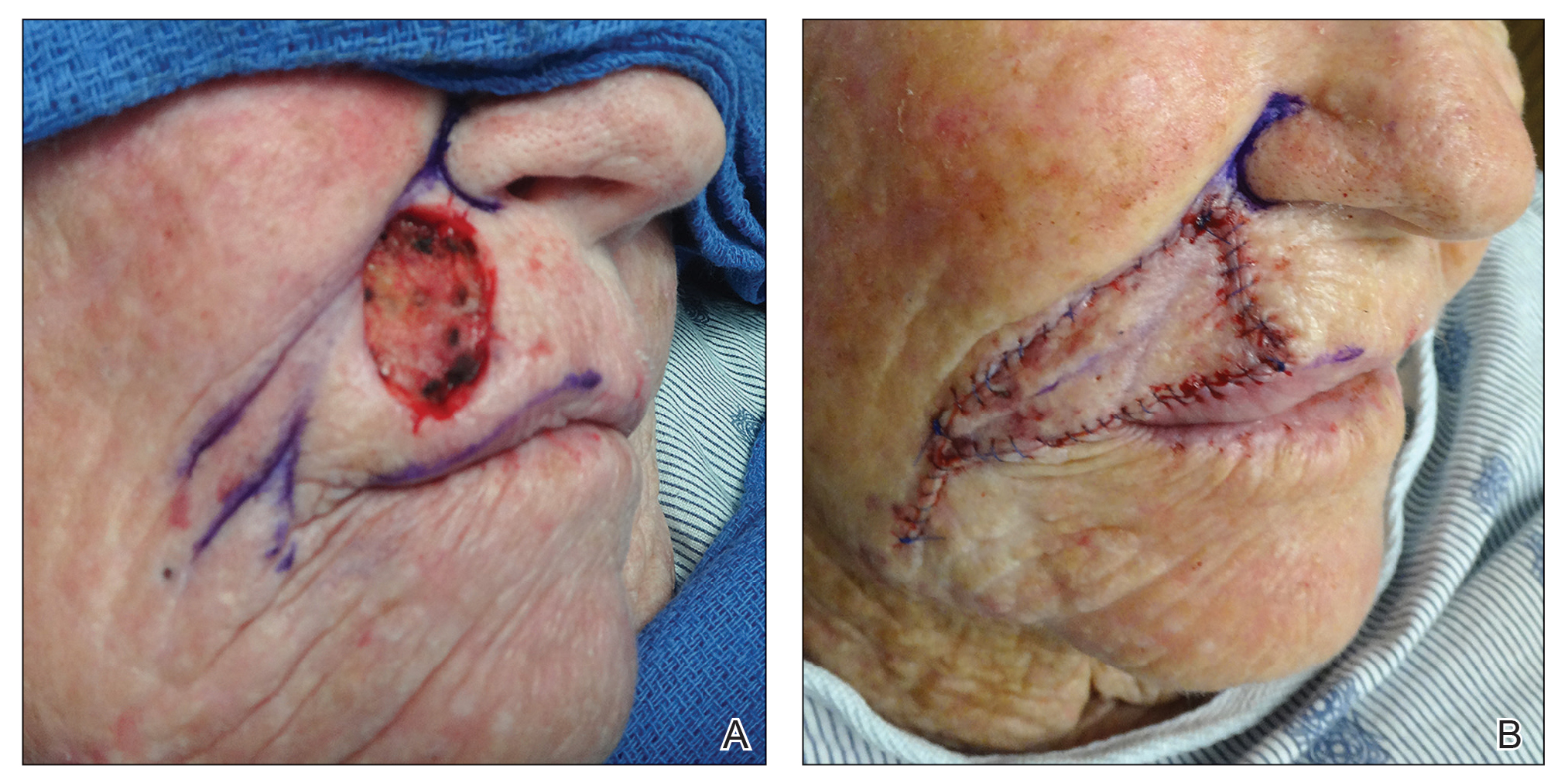

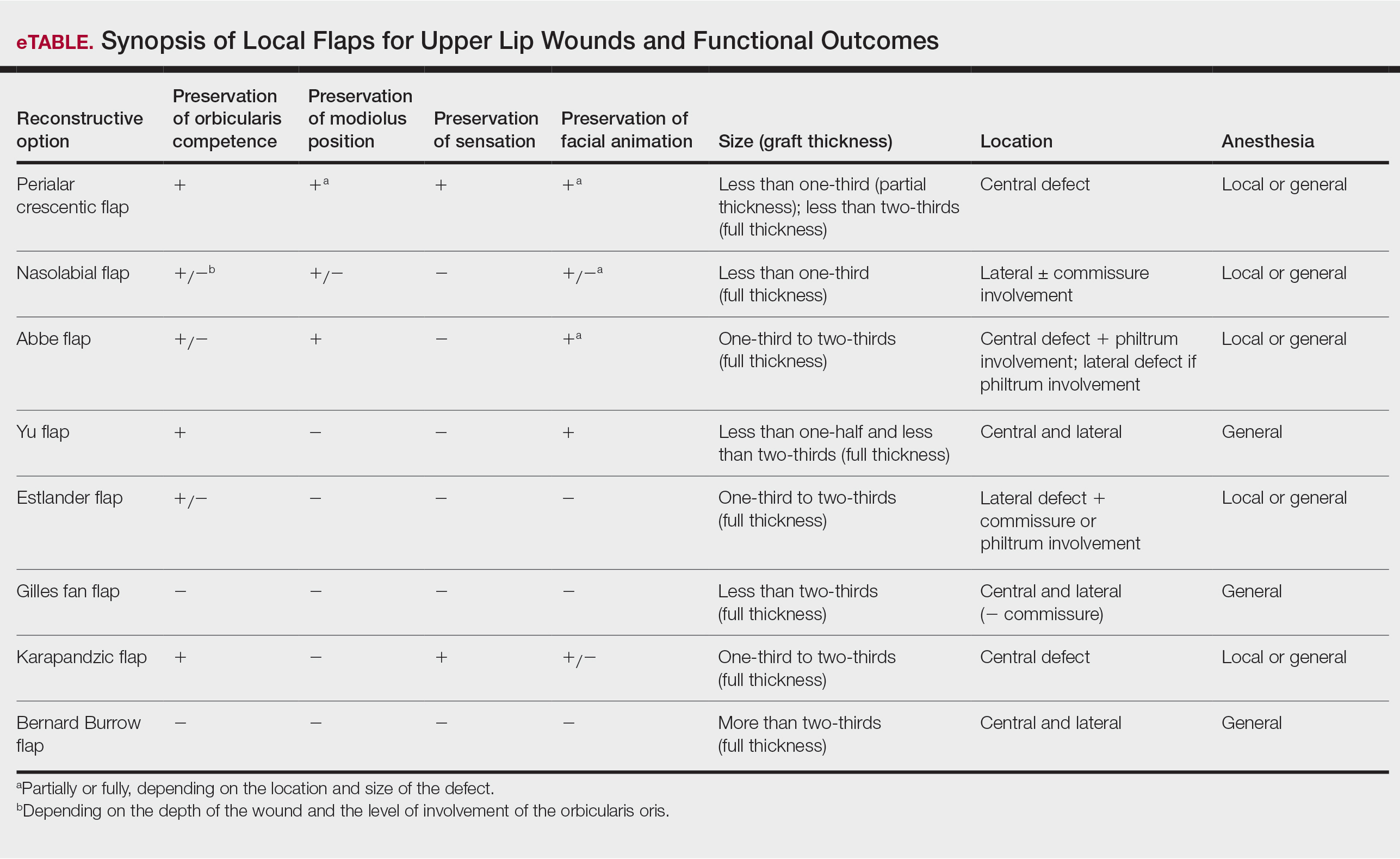

Janis23 proposed the rule of thirds to approach upper and lower lip reconstruction. Using these rules, we briefly analyze the available flaps focusing on animation, OO restoration, preservation of the modiolus position, and sensation for each (eTable).

The perialar crescentic flap, an advancement flap, can be utilized for laterally located partial-thickness defects affecting up to one-third of the upper lip, especially those adjacent to the alar base, as well as full-thickness defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip.7,24 The OO continuity and position of the modiolus often are preserved, sensation is maintained, and muscles of animation commonly are unaffected by this flap, especially in partial-thickness defects. In males, caution should be exercised where non–hair-bearing skin of the cheek is advanced to the upper lip region. Other potential complications include obliteration of the melolabial crease and pincushioning.7

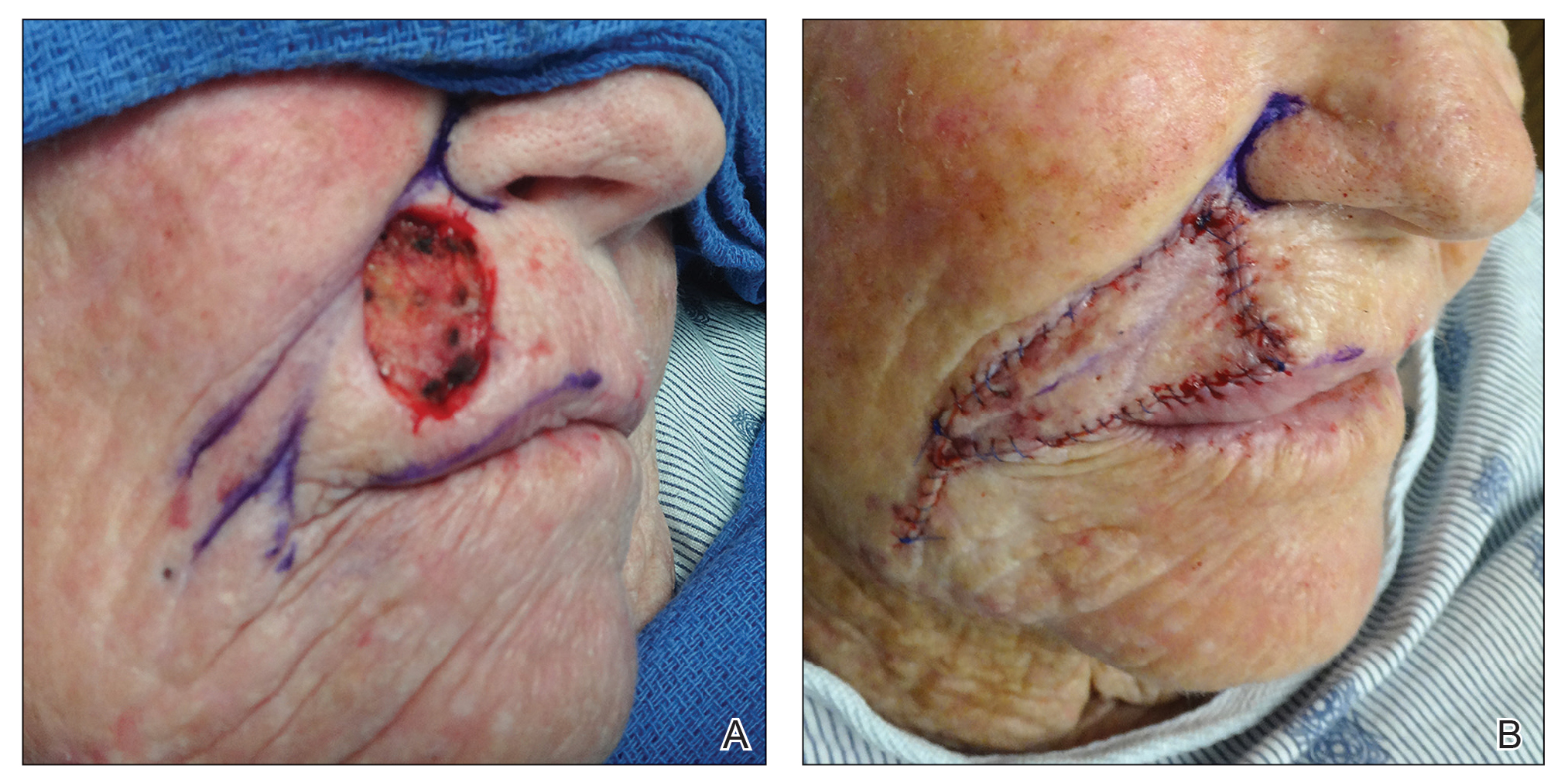

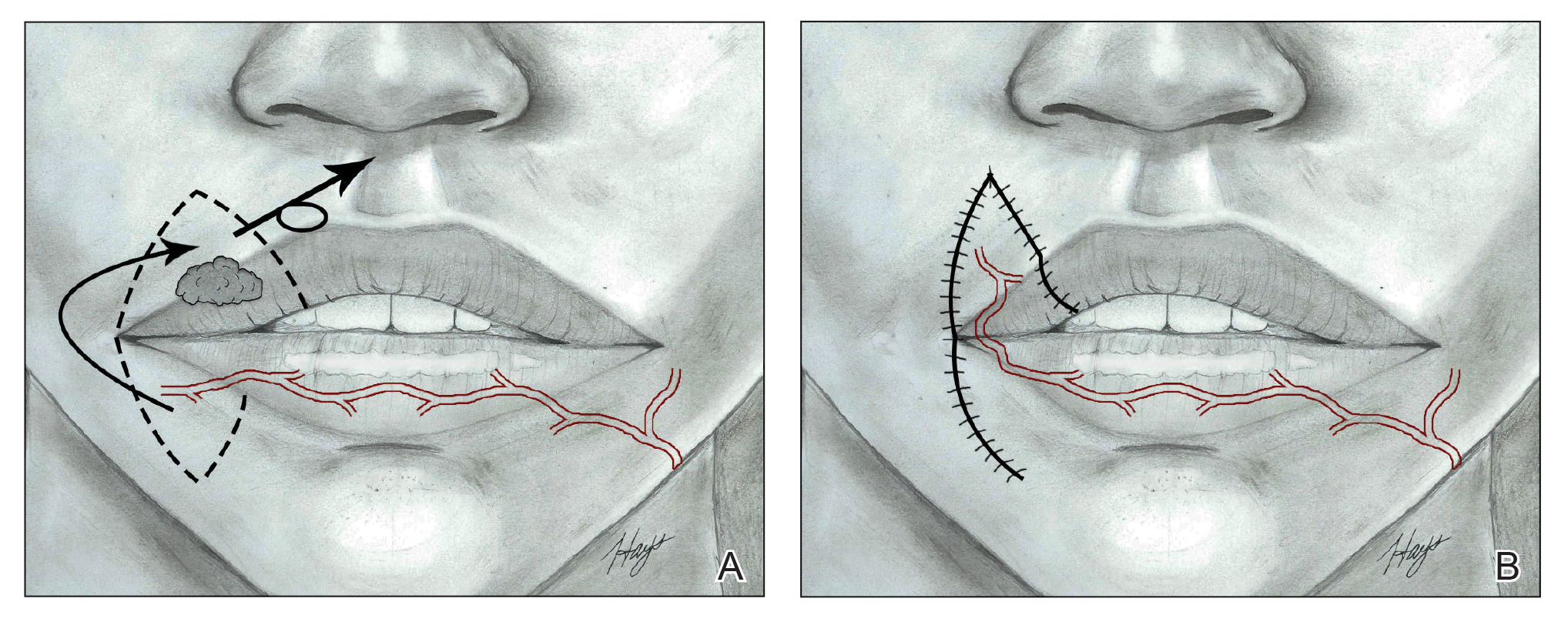

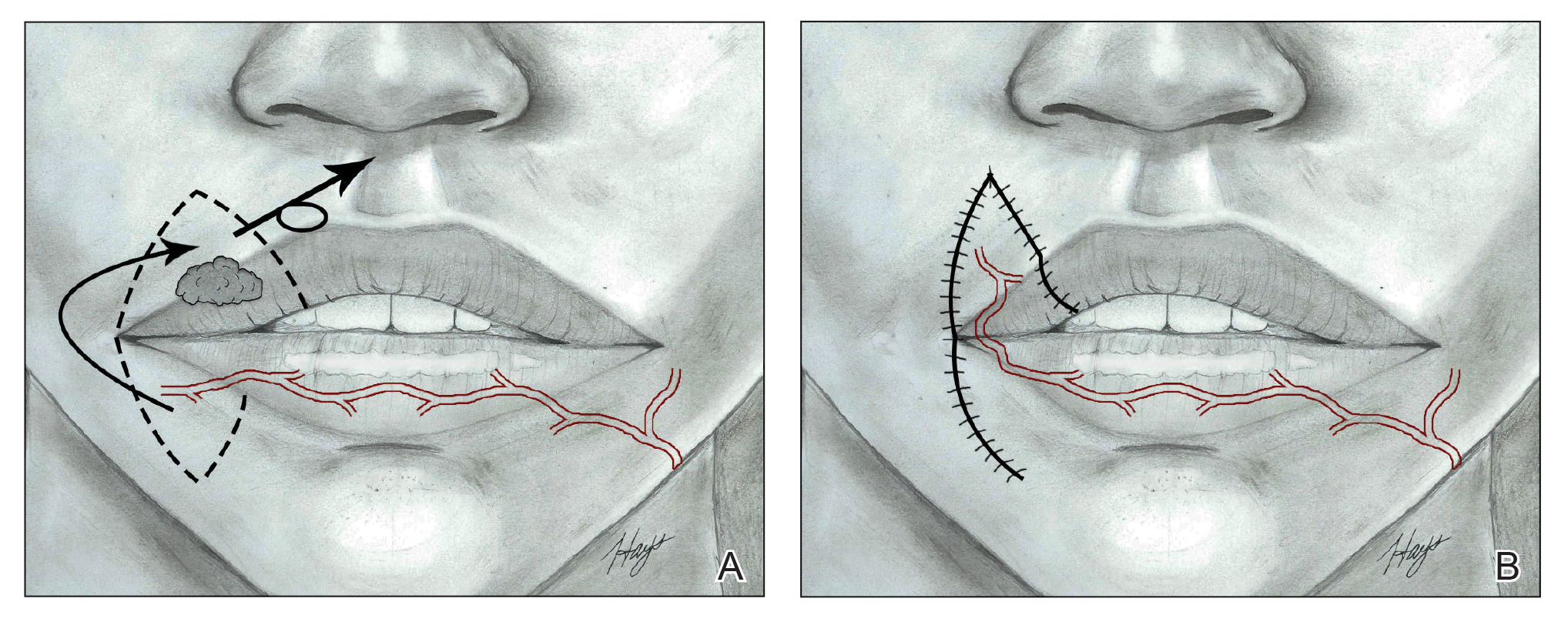

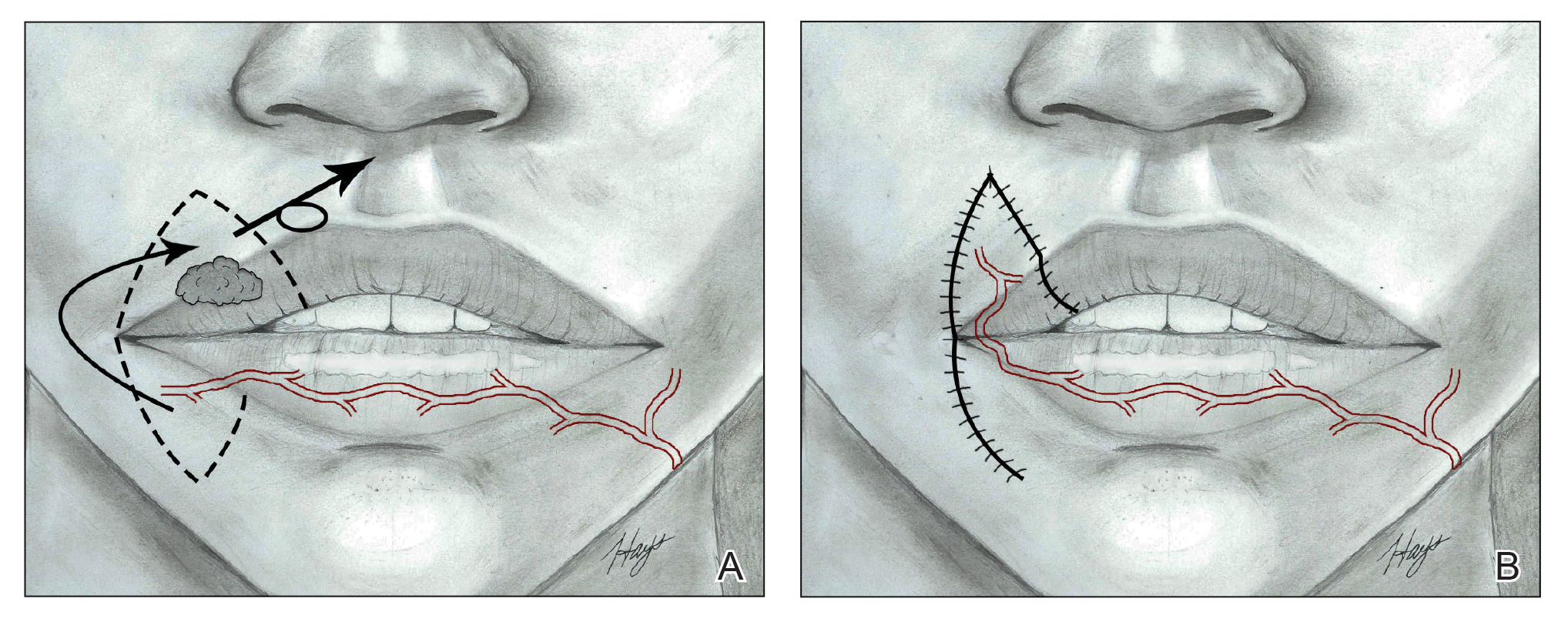

Nasolabial (ie, melolabial) flaps are suggested for repair of defects up to one-third of the upper lip, especially when the vermilion is unaffected, or in lateral defects with or without commissure involvement.7,24-28 This flap is based on the facial artery and may be used as a direct transposition, V-Y advancement, or island flap with good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 1).29,30 There is limited literature regarding the effects on animation. However, it may be beneficial in avoiding microstomia, as regional tissue is transferred from the cheek area, maintaining upper lip length. Additionally, the location of the modiolus often is unaffected, especially when the flap is harvested above the level of the muscle, providing superior facial animation function. Flap design is critical in areas lateral to the commissure and over the modiolus, as distortion of its position can occur.26 Similar to crescentic advancement, it is important to exercise caution in male patients, as non–hair-bearing tissue can be transferred to the upper lip. Reported adverse outcomes of the nasolabial flap include a thin flat upper lip, obliteration of the Cupid’s bow, and hypoesthesia that may improve over time.30

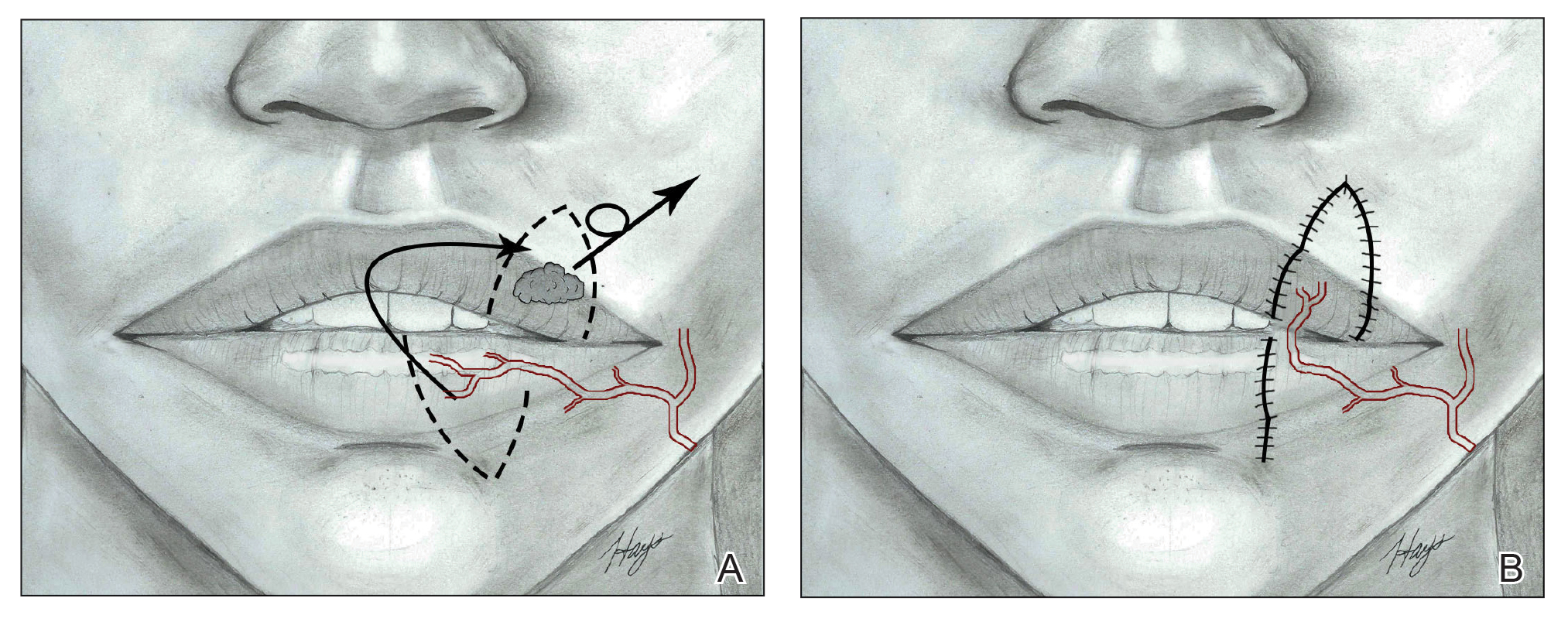

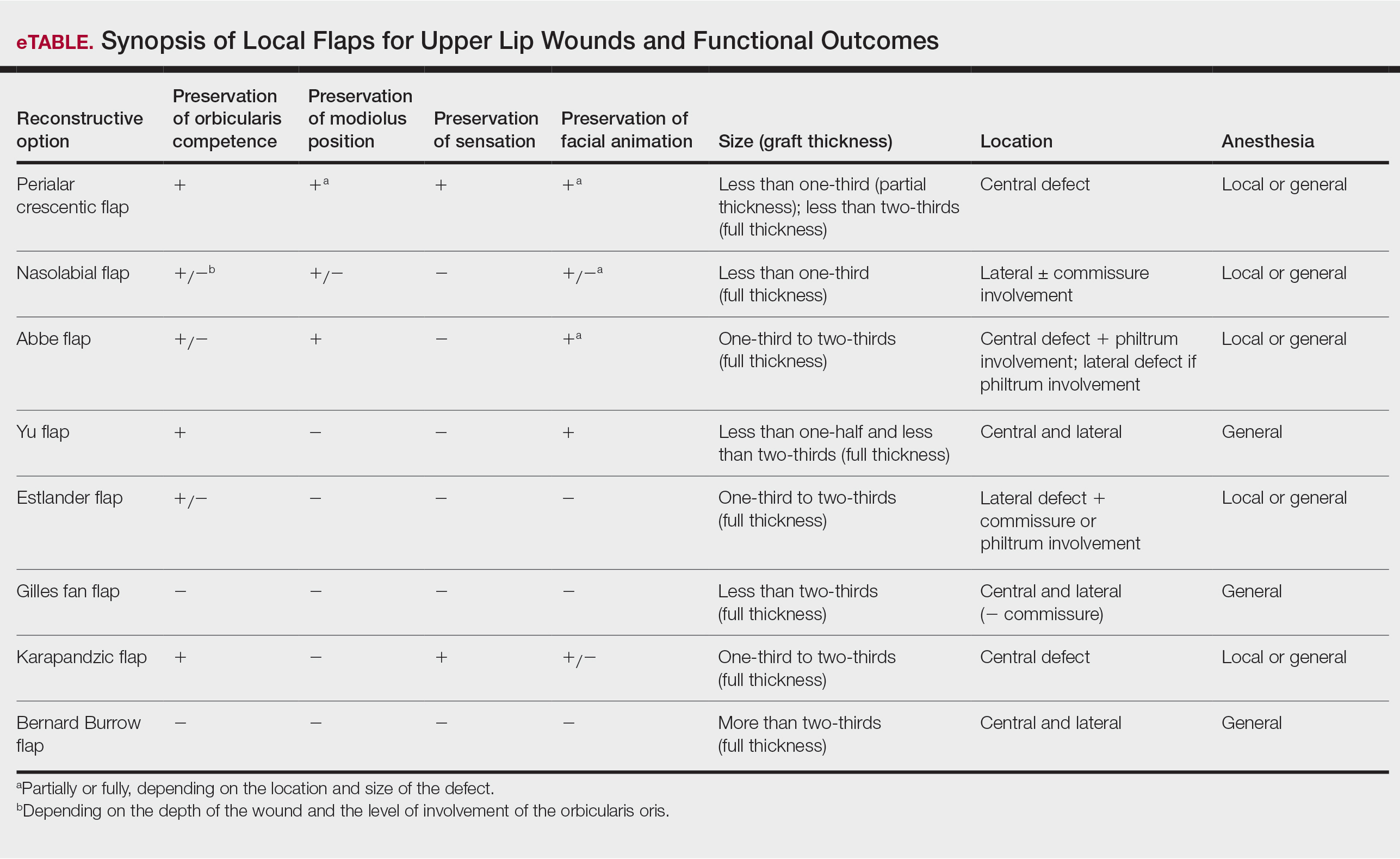

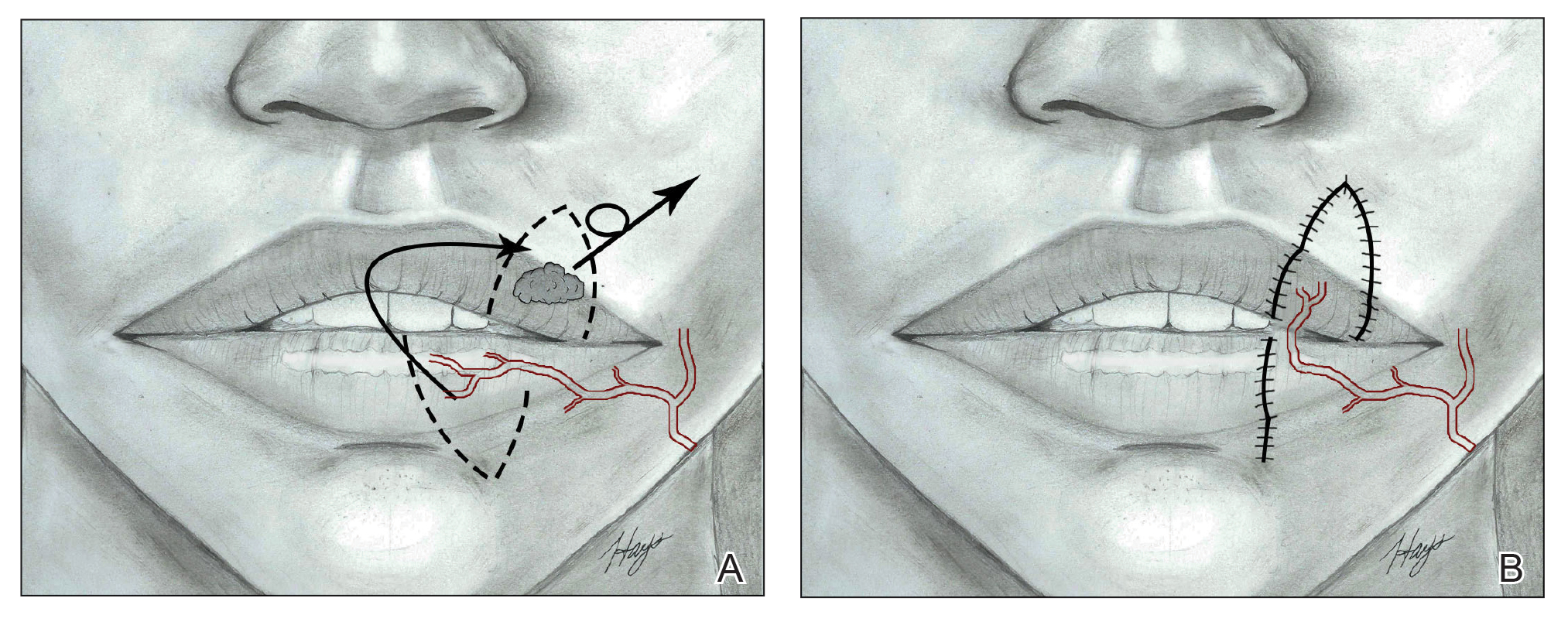

The Abbe flap is suitable for reconstruction of upper lip defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip and lateral defects, provided the commissure or philtrum is unaffected.7,8 It is a 2-stage lip-switch flap based on the inferior labial artery, where tissue is harvested and transferred from the lower lip (Figure 2).23,31 It is particularly useful for philtral reconstruction, as incision lines at the flap edges can recreate the skin folds of the philtrum. Moreover, incision lines are better concealed under the nose, making it favorable for female patients. Surgeons should consider the difference in philtral width between sexes when designing this flap for optimal aesthetic outcome, as males have larger philtral width than females.21 The Abbe flap allows preservation of the Cupid’s bow, oral commissure, and modiolus position; however, it is an insensate flap and does not establish continuity of OO.23 For central defects, the function of animation muscles is not critically affected. In philtral reconstruction using an Abbe flap, a common adverse outcome is widening of the central segment because of tension and contraction forces applied by the adjacent OO. Restoration of the continuity of the muscle through dissection and advancement in small defects or anchoring of muscle edges on deeper surfaces may avoid direct pull on the flap. In larger central defects extending beyond the native philtrum, it is important to recreate the philtrum proportional to the remaining upper and lower lips. The recommended technique is a combination of a thin Abbe flap with bilateral perialar crescentic advancement flaps to maintain a proportional philtrum. Several variations have been described, including 3D planning with muscular suspension for natural raised philtral columns, avoiding a flat upper lip.5

The Yu flap, a sensate single-stage rotational advancement flap, can be used in a variety of ways for repair of upper lip defects, depending on the size and location.26 Lateral defects up to one-half of the upper lip should be repaired with a unilateral reverse Yu flap, central defects up to one-half of the upper lip can be reconstructed with bilateral reverse Yu flaps, and defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip can be repaired with bilateral Yu flaps. This flap restores OO continuity and thus preserves sphincter function, minimizes oral incompetence, and has a low risk of microstomia. The muscles of facial animation are preserved, yet the modiolus is not. Good aesthetic outcomes have been reported depending on the location of the Yu flap because scars can be placed in the nasolabial sulcus, commissures, or medially to recreate the philtrum.26

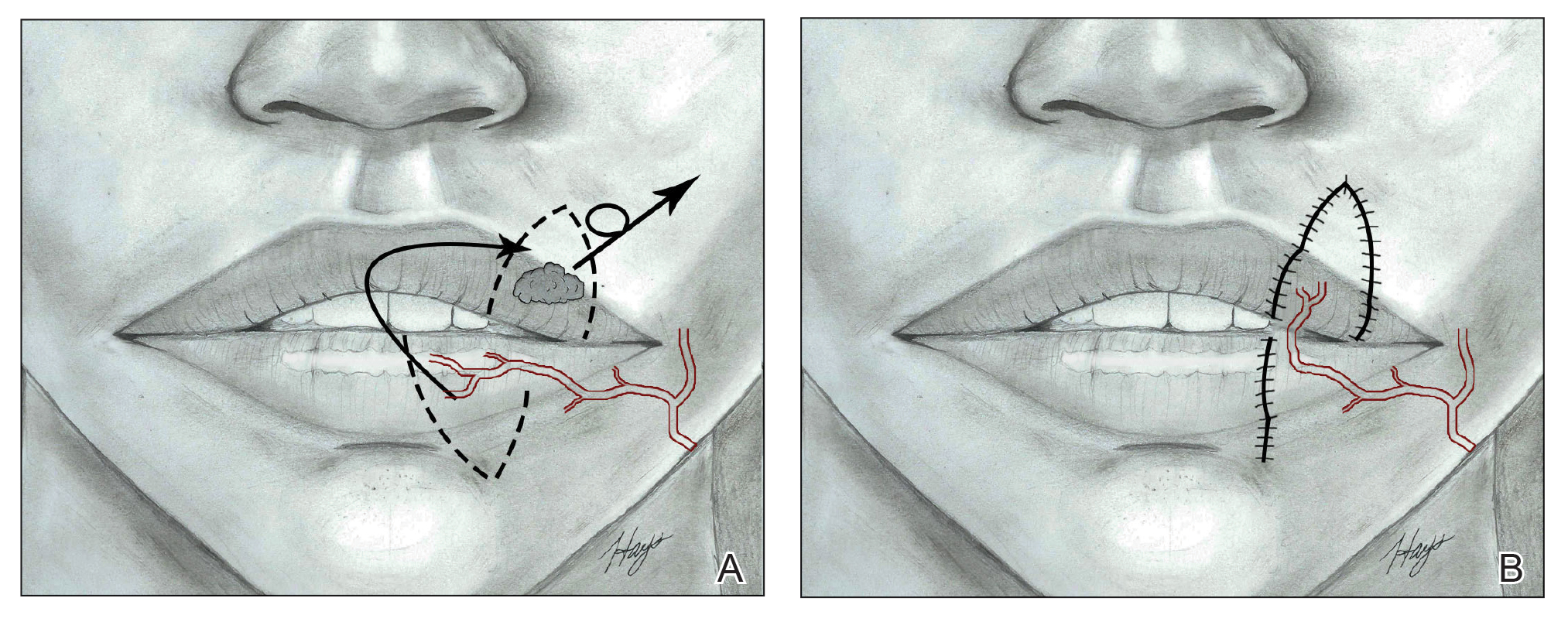

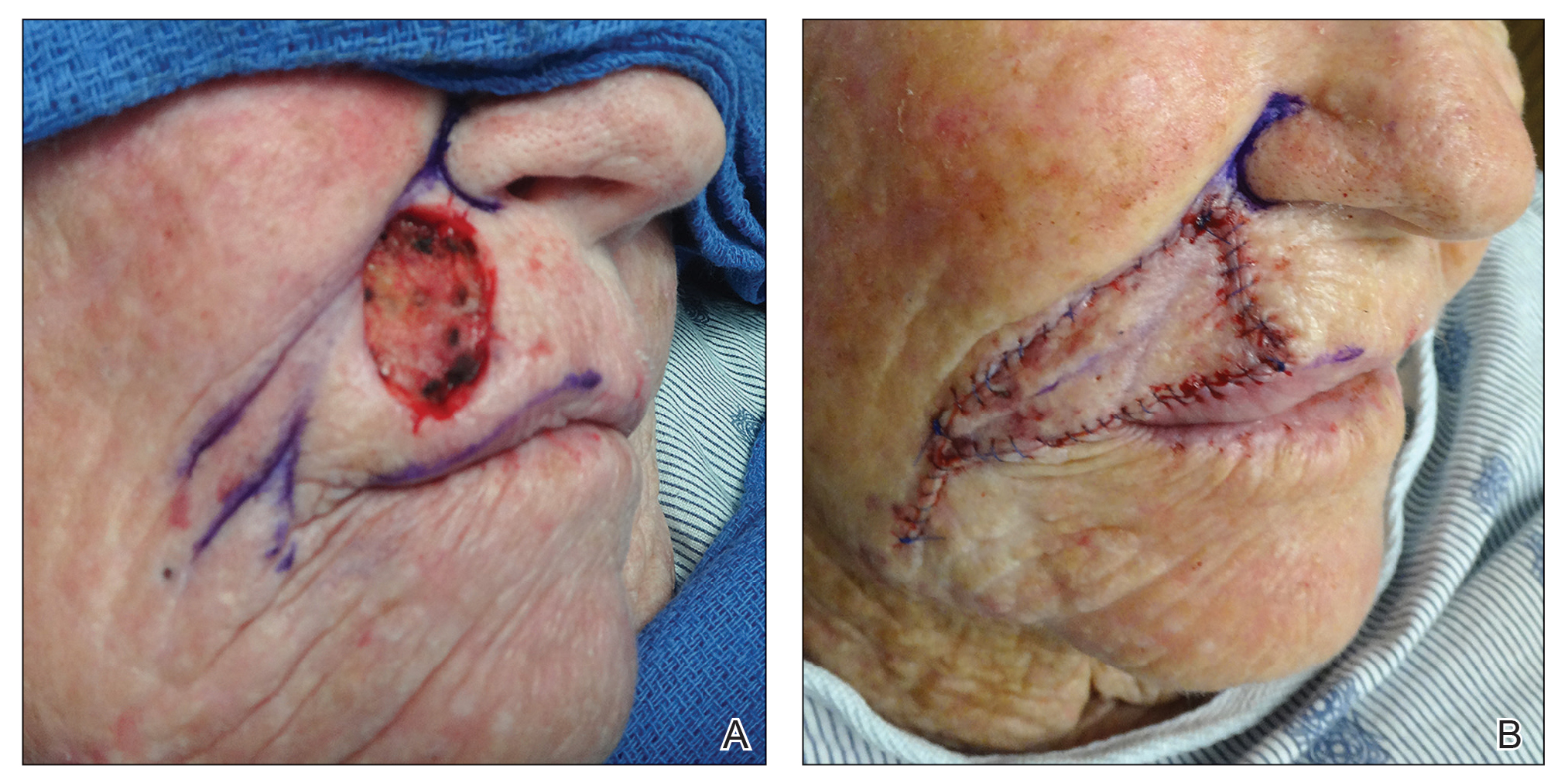

The Estlander flap is a single-stage flap utilizing donor tissue from the opposing lip for reconstruction of lateral defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip with commissure and philtrum involvement (Figure 3).8,23,32 It is an insensate flap that alters the position of the modiolus, distorting oral and facial animation.23 The superomedial position of the modiolus is better tolerated in the upper lip because it increases the relaxation tone of the lower lip and simulates the vector of contraction of major animation muscles, positively impacting the sphincteric function of the reconstructed lip. Sphincteric function action is not as impaired compared with the lower lip because the new position of the modiolus tightens the lower lip and prevents drooling.33 When designing the flap, one should consider that the inferior labial artery has been reported to remain with 10 mm of the superior border of the lower lip; therefore, pedicles of the Abbe and Estlander flaps should be at least 10 mm from the vermilion border to preserve vascular supply.34,35

The Karapandzic flap, a modified Gilles fan flap, can be employed for repair of central defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip.8,23,32,36-39 The bilateral advancement of full-thickness adjacent tissue edges preserves neurovascular structures allowing sensation and restores OO continuation.40 Prior studies have shown the average distance of the superior labial artery emergence from the facial artery and labial commissure is 12.1 mm; thus, at least 12.1 mm of tissue from the commissure should be preserved to prevent vascular compromise in Karapandzic flaps.34,35 The modiolus position is altered, and facial animation muscles are disrupted, consequently impairing facial animation, especially elevation of the lip.36 The philtrum is obliterated, producing unfavorable aesthetic outcomes. Finally, the upper lip is thinner and smaller in volume than the lower lip, increasing the risk for microstomia compared with the lower lip with a similar reconstructive technique.36

Defects larger than two-thirds of the upper lip require a Bernard Burrow flap, distant free flap, or combination of multiple regional and local flaps dependent on the characteristics of the defect.36,41 Distant free flaps are beyond the scope of this review. The Bernard Burrow flap consists of bilaterally opposing cheek advancement flaps. It is an insensate flap that does not restore OO continuity, producing minimal muscle function and poor animation. Microstomia is a common adverse outcome.36

Conclusion

Comprehensive understanding of labial anatomy and its intimate relationship to function and aesthetics of the upper lip are critical. Flap anatomy and mechanics are key factors for successful reconstruction. The purpose of this article is to utilize knowledge of histology, anatomy, and function of the upper lip to improve the outcomes of reconstruction. The Abbe flap often is utilized for reconstruction of the philtrum and central upper lip defects, though it is a less desirable option for lower lip reconstruction. The Karapandzic flap, while sensate and restorative of OO continuity, may have less optimal functional and cosmetic results compared with its use in the lower lip. Regarding lateral defects involving the commissure, the Estlander flap provides a reasonable option for the upper lip when compared with its use in lower lip defects, where outcomes are usually inferior.

- Boukovalas S, Boson AL, Hays JP, et al. A systematic review of lower lip anatomy, mechanics of local flaps, and special considerations for lower lip reconstruction. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1254-1261.

- Wu J, Yin N. Detailed anatomy of the nasolabial muscle in human fetuses as determined by micro-CT combined with iodine staining. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:111-116.

- Pepper JP, Baker SR. Local flaps: cheek and lip reconstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15:374-382.