User login

Texas launches website in fight against opioid abuse; Gen Z’ers report more mental health problems

Officials in Texas see their new “Dose of Reality” website as a tool that might help address the opioid crisis in their state.

Dose of Reality, an initiative of the state attorney general, the Texas Department of State Health Services, and Texas Health and Human Services, offers for download material on opioids. People also can learn about risk factors of opioid abuse and how to safely store the medications. Drug disposal sites statewide also are included, according to an article published by the Dallas Morning News.

“The misuse of prescription opioids costs lives and devastates Texas families in every corner of our state. Dose of Reality is a one-stop shop of information on the opioid epidemic in Texas. [It] will pull back the curtain on opioids, educate Texans and save, hopefully, many lives,” Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton reportedly said at a press conference announcing the website launch.

Of the 42,249 deaths tied to opioid overdoses reported nationwide by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in 2016, 1,375 of those deaths reportedly occurred in Texas. According to Mr. Paxton, deceptive marketing and promotion by pharmaceutical companies have been part of the problem.

Generation Z and mental health

Gen Z’ers – young people born from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s – are the most likely age group to report mental health problems, according to a report from the American Psychological Association.

The findings from the group’s 12th annual Stress in America survey of 3,458 Americans aged 18 years or older and 300 teens aged 15-17 years showed that issues such as sexual harassment and gun violence are significant stressors for Gen Z. America’s youngest adults are most likely of all generations to report poor mental health, and Gen Z also is significantly more likely to seek professional help for mental health issues, the study authors wrote.

Adolescents and young adults aged 15-21 years are more concerned than are other generations about the state of the United States, and overall, 71% of the Gen Z’ers are more positive about the country’s future. About 60% had gotten politically involved in the past year.

But that optimism did not extend to Gen Z’ers of color. “For around 4 in 10 Gen Zs of color, personal debt [41%] and housing instability (40%) are significant sources of stress, while 3 in 10 white Gen Zs [30%] say the same about personal debt and less than one-quarter [24%] of this demographic cite housing instability,” the authors wrote.

“Solutions” center in the works

A new facility to be built in a Denver neighborhood will enable offenders with mental health issues to receive treatment instead of incarceration. Once up and running, the facility, dubbed a “solutions” or “stabilization” center, will be a go-to option for police officers who have picked up someone judged to be in the throes of a mental health crisis, instead of a trip to the police station and booking, the Denver Post reported.

People referred to the center will be eligible to stay for up to 5 days and referrals will be available for continued counseling. Walk-ins will not be admitted.

“In my heart, I’m committed to making this an addition to the neighborhood that will make the neighborhood a safer place and not a more difficult place,” said Jay Flynn, a vice president of the Mental Health Center of Denver, which helped spearhead the initiative.

Not everyone is on board. Residents near the center site have voiced their concern about neighborhood safety. “It’s not that we don’t understand the needs of homelessness in our community,” said one resident at a community meeting held to discuss the center. “The fact is that our community is extremely stressed and we need to preserve a safe environment.”

The center is scheduled to open in 2020.

Is masculinity really toxic?

A new ad by Gillette raises questions about what it means to be male. The ad initially presents a more traditional view of men as boors, bullies, and sexual oppressors, then morphs into a call for a sea change to males with empathy, compassion, and a need to help. The ad came a few months after the American Psychological Association issued new practice guidelines for boys and men, in which traditional masculinity ideology was conceptualized as limiting.

Those developments prompted an op-ed piece in the Los Angeles Times that considered whether masculinity really is toxic.

“Some of the angry responses to the [Gillette] ad were over the top, and yet the detractors have a point. Take the way the ad exhorts men to start doing and saying ‘the right thing,’ and then continues, ‘Some already are. But some is not enough.’ This suggests decent men are a minority while brutes are the norm,” wrote Cathy Young, a contributing editor at Reason magazine.

“What’s more, some of the ‘toxic’ behavior shown is pretty innocuous, such as teenage boys ogling bikini-clad babes on television. (Should we shame girls who drool over cute male pop stars?) The ad also blurs the line between fighting and roughhousing, implicitly condemning the physical play styles more common among boys,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, the psychologists pointed out that, in light of many factors, including higher death rates in the United States for boys and men – compared with those of girls and women – understanding “how boys and men experience masculinity is an important cultural competency.”

Dementia and an aging workforce

As the American workforce continues to age, employers are having tough conversations about dementia and other cognitive issues, according an article from the Associated Press.

“And it’s not just managing missed deadlines,” Sarah Wood, director of global work-life services at an organization called Workplace Options, said in the piece. “If this person has been a dependable employee for 40 years and is now missing meetings, they’ll be beating themselves up over this.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of U.S. workers aged 65-74 years was expected to skyrocket by 55% between 2014 and 2024.

Those aged 65 years and older are more likely to face dementia diagnoses. Because of the Americans with Disabilities Act, employers with dementia – including Alzheimer’s – are protected, “depending on the employee’s position and level of impairment,” according to the article.

Employers can accommodate employees by taking steps such as writing instructions rather than communicating verbally and reassigning employees who operate heavy machines to desk work, according to David K. Fram, director of the Americans with Disabilities Act equal opportunity services at the National Employment Law Institute. But employees must be able to do the “essential functions of the job,” he said.

Officials in Texas see their new “Dose of Reality” website as a tool that might help address the opioid crisis in their state.

Dose of Reality, an initiative of the state attorney general, the Texas Department of State Health Services, and Texas Health and Human Services, offers for download material on opioids. People also can learn about risk factors of opioid abuse and how to safely store the medications. Drug disposal sites statewide also are included, according to an article published by the Dallas Morning News.

“The misuse of prescription opioids costs lives and devastates Texas families in every corner of our state. Dose of Reality is a one-stop shop of information on the opioid epidemic in Texas. [It] will pull back the curtain on opioids, educate Texans and save, hopefully, many lives,” Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton reportedly said at a press conference announcing the website launch.

Of the 42,249 deaths tied to opioid overdoses reported nationwide by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in 2016, 1,375 of those deaths reportedly occurred in Texas. According to Mr. Paxton, deceptive marketing and promotion by pharmaceutical companies have been part of the problem.

Generation Z and mental health

Gen Z’ers – young people born from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s – are the most likely age group to report mental health problems, according to a report from the American Psychological Association.

The findings from the group’s 12th annual Stress in America survey of 3,458 Americans aged 18 years or older and 300 teens aged 15-17 years showed that issues such as sexual harassment and gun violence are significant stressors for Gen Z. America’s youngest adults are most likely of all generations to report poor mental health, and Gen Z also is significantly more likely to seek professional help for mental health issues, the study authors wrote.

Adolescents and young adults aged 15-21 years are more concerned than are other generations about the state of the United States, and overall, 71% of the Gen Z’ers are more positive about the country’s future. About 60% had gotten politically involved in the past year.

But that optimism did not extend to Gen Z’ers of color. “For around 4 in 10 Gen Zs of color, personal debt [41%] and housing instability (40%) are significant sources of stress, while 3 in 10 white Gen Zs [30%] say the same about personal debt and less than one-quarter [24%] of this demographic cite housing instability,” the authors wrote.

“Solutions” center in the works

A new facility to be built in a Denver neighborhood will enable offenders with mental health issues to receive treatment instead of incarceration. Once up and running, the facility, dubbed a “solutions” or “stabilization” center, will be a go-to option for police officers who have picked up someone judged to be in the throes of a mental health crisis, instead of a trip to the police station and booking, the Denver Post reported.

People referred to the center will be eligible to stay for up to 5 days and referrals will be available for continued counseling. Walk-ins will not be admitted.

“In my heart, I’m committed to making this an addition to the neighborhood that will make the neighborhood a safer place and not a more difficult place,” said Jay Flynn, a vice president of the Mental Health Center of Denver, which helped spearhead the initiative.

Not everyone is on board. Residents near the center site have voiced their concern about neighborhood safety. “It’s not that we don’t understand the needs of homelessness in our community,” said one resident at a community meeting held to discuss the center. “The fact is that our community is extremely stressed and we need to preserve a safe environment.”

The center is scheduled to open in 2020.

Is masculinity really toxic?

A new ad by Gillette raises questions about what it means to be male. The ad initially presents a more traditional view of men as boors, bullies, and sexual oppressors, then morphs into a call for a sea change to males with empathy, compassion, and a need to help. The ad came a few months after the American Psychological Association issued new practice guidelines for boys and men, in which traditional masculinity ideology was conceptualized as limiting.

Those developments prompted an op-ed piece in the Los Angeles Times that considered whether masculinity really is toxic.

“Some of the angry responses to the [Gillette] ad were over the top, and yet the detractors have a point. Take the way the ad exhorts men to start doing and saying ‘the right thing,’ and then continues, ‘Some already are. But some is not enough.’ This suggests decent men are a minority while brutes are the norm,” wrote Cathy Young, a contributing editor at Reason magazine.

“What’s more, some of the ‘toxic’ behavior shown is pretty innocuous, such as teenage boys ogling bikini-clad babes on television. (Should we shame girls who drool over cute male pop stars?) The ad also blurs the line between fighting and roughhousing, implicitly condemning the physical play styles more common among boys,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, the psychologists pointed out that, in light of many factors, including higher death rates in the United States for boys and men – compared with those of girls and women – understanding “how boys and men experience masculinity is an important cultural competency.”

Dementia and an aging workforce

As the American workforce continues to age, employers are having tough conversations about dementia and other cognitive issues, according an article from the Associated Press.

“And it’s not just managing missed deadlines,” Sarah Wood, director of global work-life services at an organization called Workplace Options, said in the piece. “If this person has been a dependable employee for 40 years and is now missing meetings, they’ll be beating themselves up over this.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of U.S. workers aged 65-74 years was expected to skyrocket by 55% between 2014 and 2024.

Those aged 65 years and older are more likely to face dementia diagnoses. Because of the Americans with Disabilities Act, employers with dementia – including Alzheimer’s – are protected, “depending on the employee’s position and level of impairment,” according to the article.

Employers can accommodate employees by taking steps such as writing instructions rather than communicating verbally and reassigning employees who operate heavy machines to desk work, according to David K. Fram, director of the Americans with Disabilities Act equal opportunity services at the National Employment Law Institute. But employees must be able to do the “essential functions of the job,” he said.

Officials in Texas see their new “Dose of Reality” website as a tool that might help address the opioid crisis in their state.

Dose of Reality, an initiative of the state attorney general, the Texas Department of State Health Services, and Texas Health and Human Services, offers for download material on opioids. People also can learn about risk factors of opioid abuse and how to safely store the medications. Drug disposal sites statewide also are included, according to an article published by the Dallas Morning News.

“The misuse of prescription opioids costs lives and devastates Texas families in every corner of our state. Dose of Reality is a one-stop shop of information on the opioid epidemic in Texas. [It] will pull back the curtain on opioids, educate Texans and save, hopefully, many lives,” Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton reportedly said at a press conference announcing the website launch.

Of the 42,249 deaths tied to opioid overdoses reported nationwide by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in 2016, 1,375 of those deaths reportedly occurred in Texas. According to Mr. Paxton, deceptive marketing and promotion by pharmaceutical companies have been part of the problem.

Generation Z and mental health

Gen Z’ers – young people born from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s – are the most likely age group to report mental health problems, according to a report from the American Psychological Association.

The findings from the group’s 12th annual Stress in America survey of 3,458 Americans aged 18 years or older and 300 teens aged 15-17 years showed that issues such as sexual harassment and gun violence are significant stressors for Gen Z. America’s youngest adults are most likely of all generations to report poor mental health, and Gen Z also is significantly more likely to seek professional help for mental health issues, the study authors wrote.

Adolescents and young adults aged 15-21 years are more concerned than are other generations about the state of the United States, and overall, 71% of the Gen Z’ers are more positive about the country’s future. About 60% had gotten politically involved in the past year.

But that optimism did not extend to Gen Z’ers of color. “For around 4 in 10 Gen Zs of color, personal debt [41%] and housing instability (40%) are significant sources of stress, while 3 in 10 white Gen Zs [30%] say the same about personal debt and less than one-quarter [24%] of this demographic cite housing instability,” the authors wrote.

“Solutions” center in the works

A new facility to be built in a Denver neighborhood will enable offenders with mental health issues to receive treatment instead of incarceration. Once up and running, the facility, dubbed a “solutions” or “stabilization” center, will be a go-to option for police officers who have picked up someone judged to be in the throes of a mental health crisis, instead of a trip to the police station and booking, the Denver Post reported.

People referred to the center will be eligible to stay for up to 5 days and referrals will be available for continued counseling. Walk-ins will not be admitted.

“In my heart, I’m committed to making this an addition to the neighborhood that will make the neighborhood a safer place and not a more difficult place,” said Jay Flynn, a vice president of the Mental Health Center of Denver, which helped spearhead the initiative.

Not everyone is on board. Residents near the center site have voiced their concern about neighborhood safety. “It’s not that we don’t understand the needs of homelessness in our community,” said one resident at a community meeting held to discuss the center. “The fact is that our community is extremely stressed and we need to preserve a safe environment.”

The center is scheduled to open in 2020.

Is masculinity really toxic?

A new ad by Gillette raises questions about what it means to be male. The ad initially presents a more traditional view of men as boors, bullies, and sexual oppressors, then morphs into a call for a sea change to males with empathy, compassion, and a need to help. The ad came a few months after the American Psychological Association issued new practice guidelines for boys and men, in which traditional masculinity ideology was conceptualized as limiting.

Those developments prompted an op-ed piece in the Los Angeles Times that considered whether masculinity really is toxic.

“Some of the angry responses to the [Gillette] ad were over the top, and yet the detractors have a point. Take the way the ad exhorts men to start doing and saying ‘the right thing,’ and then continues, ‘Some already are. But some is not enough.’ This suggests decent men are a minority while brutes are the norm,” wrote Cathy Young, a contributing editor at Reason magazine.

“What’s more, some of the ‘toxic’ behavior shown is pretty innocuous, such as teenage boys ogling bikini-clad babes on television. (Should we shame girls who drool over cute male pop stars?) The ad also blurs the line between fighting and roughhousing, implicitly condemning the physical play styles more common among boys,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, the psychologists pointed out that, in light of many factors, including higher death rates in the United States for boys and men – compared with those of girls and women – understanding “how boys and men experience masculinity is an important cultural competency.”

Dementia and an aging workforce

As the American workforce continues to age, employers are having tough conversations about dementia and other cognitive issues, according an article from the Associated Press.

“And it’s not just managing missed deadlines,” Sarah Wood, director of global work-life services at an organization called Workplace Options, said in the piece. “If this person has been a dependable employee for 40 years and is now missing meetings, they’ll be beating themselves up over this.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of U.S. workers aged 65-74 years was expected to skyrocket by 55% between 2014 and 2024.

Those aged 65 years and older are more likely to face dementia diagnoses. Because of the Americans with Disabilities Act, employers with dementia – including Alzheimer’s – are protected, “depending on the employee’s position and level of impairment,” according to the article.

Employers can accommodate employees by taking steps such as writing instructions rather than communicating verbally and reassigning employees who operate heavy machines to desk work, according to David K. Fram, director of the Americans with Disabilities Act equal opportunity services at the National Employment Law Institute. But employees must be able to do the “essential functions of the job,” he said.

We must counsel against heat-not-burn cigarettes

Tobacco companies are marketing a new version of cigarettes dubbed heat-not-burn (HNB) cigarettes.1,2 Offered as a “modified-risk tobacco product,” HNB cigarettes utilize a lithium battery-powered heating element and are available all over the world.1,2 Like conventional smokes, they contain tobacco, but deliver nicotine by heating leaves at 350° C rather than burning them at 600° C.1-3 Heating the tobacco produces an inhalable aerosol with tobacco flavor and nicotine, without smoke. These HNB cigarettes are also different from e-cigarettes that aerosolize a liquid.

Tobacco companies contend that HNB cigarettes are safer than smoking tobacco.1 Consumers inhale a heated tobacco aerosol that reportedly contains less nicotine and fewer toxicities; yet, HNB are not independently substantiated as being healthier, nor proven safe.1-5 Thermal decomposition, rather than combustion, may afford a less dangerous nicotine consumption; however, HNB aerosols deliver many of the same dangerous compounds as traditional cigarettes, including carbon monoxide, tar, and aromatic hydrocarbons.2-6 Despite possible harm reduction in the short-run, long-term safety remains unconfirmed.

Safety in passive environmental inhalations is not established.2 HNB cigarettes are contraindicated during pregnancy and/or lactation. Nicotine is provided in addictive quantities, enough to foster continued dependence. Exposure to HNB products can promote longer-term usage or lead to smoking traditional tobacco cigarettes. There is also an increased risk to non-smokers of exposure to HNB aerosols. Additionally, lithium batteries have been known to burn or explode. HNB devices may even lead to privacy concerns due micro-controller chips contained within that harvest information. These chips could inform manufacturers about device usage.7

Tobacco is a global health hazard and smoking is the number one preventable cause of disease.1,5,8 Global smoking prevalence is nearing 19%.9 There are concerns about dual use, rather than HNB cigarettes alone as a substitute for conventional smoking. The ultimate hope is to abstain from all tobacco and nicotine. Although HNB inhalations contain fewer toxic chemicals than by smoking, evidence regarding mitigation of tobacco-related diseases is inconclusive.10

Physicians have an obligation to minimize tobacco and nicotine-related hazards. Ongoing research and clinical exposure might better document the health impact of HNB cigarettes. Until the risks and benefits of HNB cigarettes are confirmed, health care professionals would be wise to counsel against their use.

Diksha Mohanty, MD; Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

1. Combustible cigarettes kill millions a year. Can Big Tobacco save them? The Economist Web site. https://www.economist.com/business/2017/12/19/combustible-cigarettes-kill-millions-a-year-can-big-tobacco-save-them. Accessed November 9, 2018.

2. Auer R, Concha-Lozano N, Jacot-Sadowski I, et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco cigarettes: smoke by any other name. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1050-1052.

3. Caputi TL. Industry watch: heat-not-burn tobacco products are about to reach their boiling point. Tob Control. 2016;26:609-610.

4. Jenssen BP, Walley SC, McGrath-Morrow SA. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: Tobacco industry claims no substitute for science. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172383.

5. Levy DT, Cummings KM, Villanti AC, et al. A framework for evaluating the public health impact of e-cigarettes and other vaporized nicotine products. Addiction. 2017;112:8-17.

6. Bekki K, Inaba Y, Uchiyama S, et al. Comparison of chemicals in mainstream smoke in heat-not-burn tobacco and combustion cigarettes. J UOEH, 2017;39:201-207.

7. Lasseter T, Wilson D, Wilson T, et al. Philip Morris device knows a lot about your smoking habit. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/tobacco-iqos-device. Accessed November 9, 2018.

8. Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, et al. Smoking and mortality — beyond established causes. New Engl J Med. 2015;372:631-640.

9. World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in tobacco smoking 2000-2025 - First edition. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/reportontrendstobaccosmoking/en/index4.html. Accessed November 9, 2018.

10. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. CTPConnect—September 2017. https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/NewsEvents/ucm576895.htm. Updated June 14, 2018. Accessed Nov ember 9, 2018.

Tobacco companies are marketing a new version of cigarettes dubbed heat-not-burn (HNB) cigarettes.1,2 Offered as a “modified-risk tobacco product,” HNB cigarettes utilize a lithium battery-powered heating element and are available all over the world.1,2 Like conventional smokes, they contain tobacco, but deliver nicotine by heating leaves at 350° C rather than burning them at 600° C.1-3 Heating the tobacco produces an inhalable aerosol with tobacco flavor and nicotine, without smoke. These HNB cigarettes are also different from e-cigarettes that aerosolize a liquid.

Tobacco companies contend that HNB cigarettes are safer than smoking tobacco.1 Consumers inhale a heated tobacco aerosol that reportedly contains less nicotine and fewer toxicities; yet, HNB are not independently substantiated as being healthier, nor proven safe.1-5 Thermal decomposition, rather than combustion, may afford a less dangerous nicotine consumption; however, HNB aerosols deliver many of the same dangerous compounds as traditional cigarettes, including carbon monoxide, tar, and aromatic hydrocarbons.2-6 Despite possible harm reduction in the short-run, long-term safety remains unconfirmed.

Safety in passive environmental inhalations is not established.2 HNB cigarettes are contraindicated during pregnancy and/or lactation. Nicotine is provided in addictive quantities, enough to foster continued dependence. Exposure to HNB products can promote longer-term usage or lead to smoking traditional tobacco cigarettes. There is also an increased risk to non-smokers of exposure to HNB aerosols. Additionally, lithium batteries have been known to burn or explode. HNB devices may even lead to privacy concerns due micro-controller chips contained within that harvest information. These chips could inform manufacturers about device usage.7

Tobacco is a global health hazard and smoking is the number one preventable cause of disease.1,5,8 Global smoking prevalence is nearing 19%.9 There are concerns about dual use, rather than HNB cigarettes alone as a substitute for conventional smoking. The ultimate hope is to abstain from all tobacco and nicotine. Although HNB inhalations contain fewer toxic chemicals than by smoking, evidence regarding mitigation of tobacco-related diseases is inconclusive.10

Physicians have an obligation to minimize tobacco and nicotine-related hazards. Ongoing research and clinical exposure might better document the health impact of HNB cigarettes. Until the risks and benefits of HNB cigarettes are confirmed, health care professionals would be wise to counsel against their use.

Diksha Mohanty, MD; Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

Tobacco companies are marketing a new version of cigarettes dubbed heat-not-burn (HNB) cigarettes.1,2 Offered as a “modified-risk tobacco product,” HNB cigarettes utilize a lithium battery-powered heating element and are available all over the world.1,2 Like conventional smokes, they contain tobacco, but deliver nicotine by heating leaves at 350° C rather than burning them at 600° C.1-3 Heating the tobacco produces an inhalable aerosol with tobacco flavor and nicotine, without smoke. These HNB cigarettes are also different from e-cigarettes that aerosolize a liquid.

Tobacco companies contend that HNB cigarettes are safer than smoking tobacco.1 Consumers inhale a heated tobacco aerosol that reportedly contains less nicotine and fewer toxicities; yet, HNB are not independently substantiated as being healthier, nor proven safe.1-5 Thermal decomposition, rather than combustion, may afford a less dangerous nicotine consumption; however, HNB aerosols deliver many of the same dangerous compounds as traditional cigarettes, including carbon monoxide, tar, and aromatic hydrocarbons.2-6 Despite possible harm reduction in the short-run, long-term safety remains unconfirmed.

Safety in passive environmental inhalations is not established.2 HNB cigarettes are contraindicated during pregnancy and/or lactation. Nicotine is provided in addictive quantities, enough to foster continued dependence. Exposure to HNB products can promote longer-term usage or lead to smoking traditional tobacco cigarettes. There is also an increased risk to non-smokers of exposure to HNB aerosols. Additionally, lithium batteries have been known to burn or explode. HNB devices may even lead to privacy concerns due micro-controller chips contained within that harvest information. These chips could inform manufacturers about device usage.7

Tobacco is a global health hazard and smoking is the number one preventable cause of disease.1,5,8 Global smoking prevalence is nearing 19%.9 There are concerns about dual use, rather than HNB cigarettes alone as a substitute for conventional smoking. The ultimate hope is to abstain from all tobacco and nicotine. Although HNB inhalations contain fewer toxic chemicals than by smoking, evidence regarding mitigation of tobacco-related diseases is inconclusive.10

Physicians have an obligation to minimize tobacco and nicotine-related hazards. Ongoing research and clinical exposure might better document the health impact of HNB cigarettes. Until the risks and benefits of HNB cigarettes are confirmed, health care professionals would be wise to counsel against their use.

Diksha Mohanty, MD; Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

1. Combustible cigarettes kill millions a year. Can Big Tobacco save them? The Economist Web site. https://www.economist.com/business/2017/12/19/combustible-cigarettes-kill-millions-a-year-can-big-tobacco-save-them. Accessed November 9, 2018.

2. Auer R, Concha-Lozano N, Jacot-Sadowski I, et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco cigarettes: smoke by any other name. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1050-1052.

3. Caputi TL. Industry watch: heat-not-burn tobacco products are about to reach their boiling point. Tob Control. 2016;26:609-610.

4. Jenssen BP, Walley SC, McGrath-Morrow SA. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: Tobacco industry claims no substitute for science. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172383.

5. Levy DT, Cummings KM, Villanti AC, et al. A framework for evaluating the public health impact of e-cigarettes and other vaporized nicotine products. Addiction. 2017;112:8-17.

6. Bekki K, Inaba Y, Uchiyama S, et al. Comparison of chemicals in mainstream smoke in heat-not-burn tobacco and combustion cigarettes. J UOEH, 2017;39:201-207.

7. Lasseter T, Wilson D, Wilson T, et al. Philip Morris device knows a lot about your smoking habit. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/tobacco-iqos-device. Accessed November 9, 2018.

8. Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, et al. Smoking and mortality — beyond established causes. New Engl J Med. 2015;372:631-640.

9. World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in tobacco smoking 2000-2025 - First edition. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/reportontrendstobaccosmoking/en/index4.html. Accessed November 9, 2018.

10. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. CTPConnect—September 2017. https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/NewsEvents/ucm576895.htm. Updated June 14, 2018. Accessed Nov ember 9, 2018.

1. Combustible cigarettes kill millions a year. Can Big Tobacco save them? The Economist Web site. https://www.economist.com/business/2017/12/19/combustible-cigarettes-kill-millions-a-year-can-big-tobacco-save-them. Accessed November 9, 2018.

2. Auer R, Concha-Lozano N, Jacot-Sadowski I, et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco cigarettes: smoke by any other name. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1050-1052.

3. Caputi TL. Industry watch: heat-not-burn tobacco products are about to reach their boiling point. Tob Control. 2016;26:609-610.

4. Jenssen BP, Walley SC, McGrath-Morrow SA. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: Tobacco industry claims no substitute for science. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172383.

5. Levy DT, Cummings KM, Villanti AC, et al. A framework for evaluating the public health impact of e-cigarettes and other vaporized nicotine products. Addiction. 2017;112:8-17.

6. Bekki K, Inaba Y, Uchiyama S, et al. Comparison of chemicals in mainstream smoke in heat-not-burn tobacco and combustion cigarettes. J UOEH, 2017;39:201-207.

7. Lasseter T, Wilson D, Wilson T, et al. Philip Morris device knows a lot about your smoking habit. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/tobacco-iqos-device. Accessed November 9, 2018.

8. Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, et al. Smoking and mortality — beyond established causes. New Engl J Med. 2015;372:631-640.

9. World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in tobacco smoking 2000-2025 - First edition. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/reportontrendstobaccosmoking/en/index4.html. Accessed November 9, 2018.

10. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. CTPConnect—September 2017. https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/NewsEvents/ucm576895.htm. Updated June 14, 2018. Accessed Nov ember 9, 2018.

Alcohol use disorder: How best to screen and intervene

THE CASE

Ms. E, a 42-year-old woman, visited her new physician for a physical exam. When asked about alcohol intake, she reported that she drank 3 to 4 beers after work and sometimes 5 to 8 beers a day on the weekends. Occasionally, she exceeded those amounts, but she didn’t feel guilty about her drinking. She was often late to work and said her relationship with her boyfriend was strained. A review of systems was positive for fatigue, poor concentration, abdominal pain, and weight gain. Her body mass index was 41, pulse 100 beats/min, blood pressure 125/75 mm Hg, and she was afebrile. Her physical exam was otherwise within normal limits.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a common and often untreated condition that is increasingly prevalent in the United States.1 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) characterizes AUD as a combination of signs and symptoms typifying alcohol abuse and dependence (discussed in a bit).2

Data from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) showed 15.7 million Americans with AUD, affecting 6.2% of the population ages 18 years or older and 2.5% of adolescents ages 12 to 17 years.3

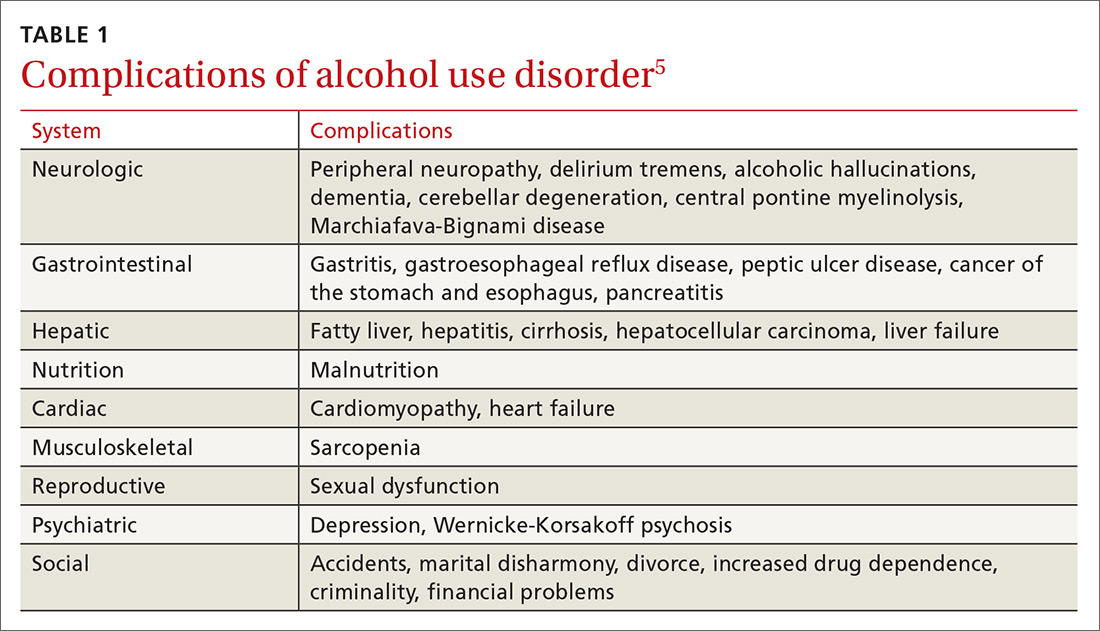

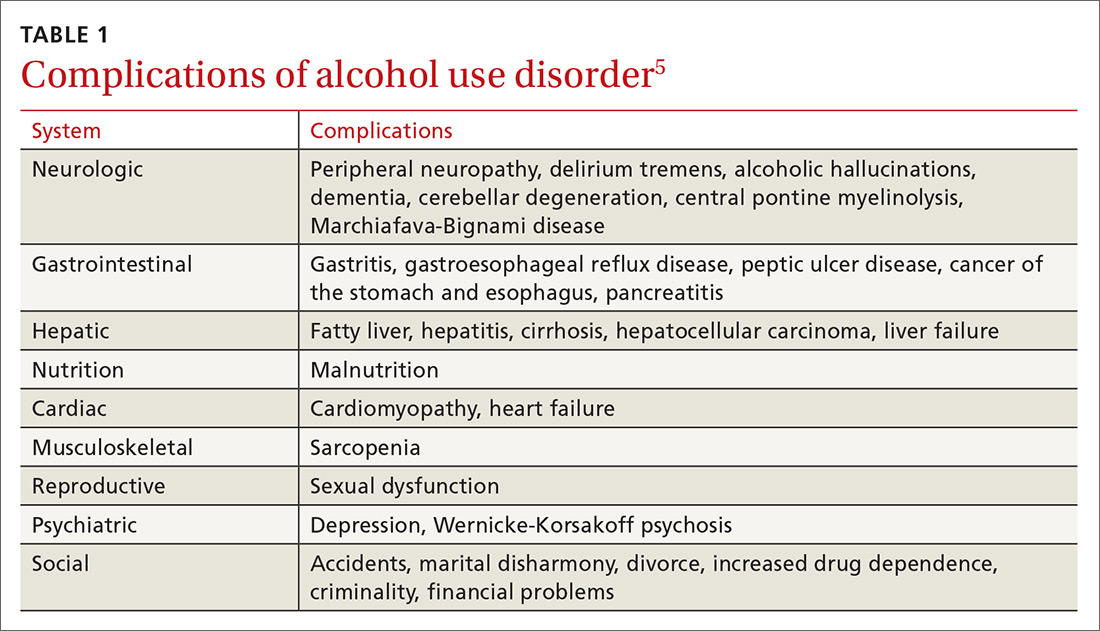

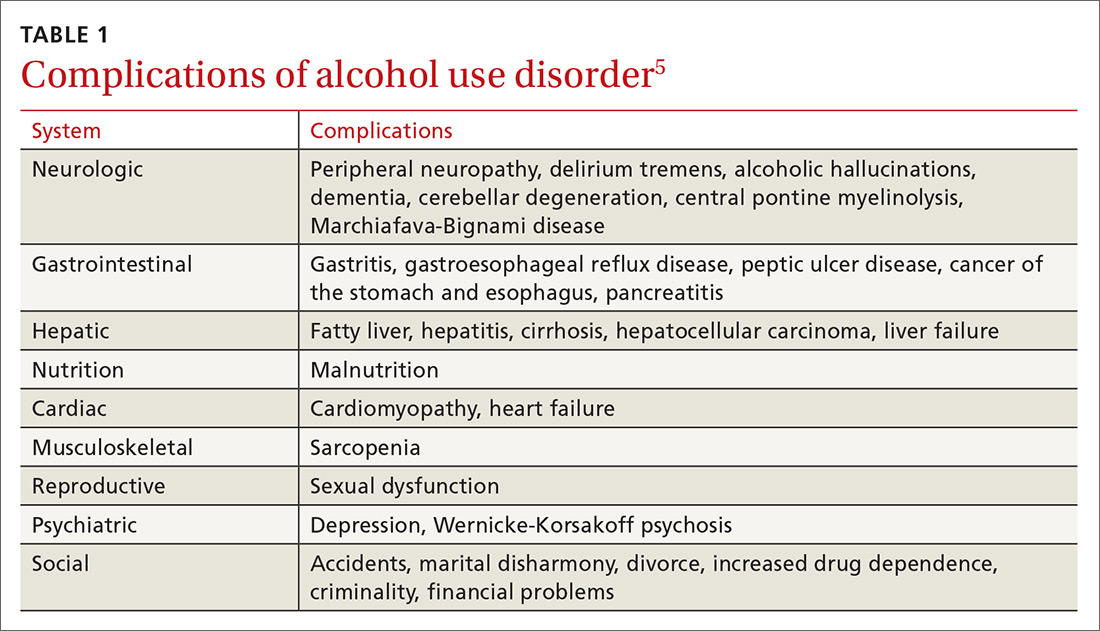

Alcohol use and AUD account for an estimated 3.8% of all global deaths and 4.6% of global disability-adjusted life years.4 AUD adversely affects several systems (TABLE 15), and patients with AUD are sicker and more likely to die younger than those without AUD.4 In the United States, prevalence of AUD has increased in recent years among women, older adults, racial minorities, and individuals with a low education level.6

Screening for AUD is reasonable and straightforward, although diagnosis and treatment of AUD in primary care settings may be challenging due to competing clinical priorities; lack of training, resources, and support; and skepticism about the efficacy of behavioral and pharmacologic treatments.7,8 However, family physicians are in an excellent position to diagnose and help address the complex biopsychosocial needs of patients with AUD, often in collaboration with colleagues and community organizations.

Signs and symptoms of AUD

In clinical practice, at least 2 of the following 11 behaviors or symptoms are required to diagnose AUD2:

- consuming larger amounts of alcohol over a longer period than intended

- persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use

- making a significant effort to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol

In moderate-to-severe cases:

- cravings or urges to use alcohol

- recurrent failure to fulfill major work, school, or social obligations

- continued alcohol use despite recurrent social and interpersonal problems

- giving up social, occupational, and recreational activities due to alcohol

- using alcohol in physically dangerous situations

- continued alcohol use despite having physical or psychological problems

- tolerance to alcohol’s effects

- withdrawal symptoms.

Continue to: Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if...

Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if they exhibit 2 or 3 symptoms, moderate AUD with 4 or 5 symptoms, and severe AUD if there are 6 or more symptoms.2

Those who meet criteria for AUD and are able to stop using alcohol are deemed to be in early remission if the criteria have gone unfulfilled for at least 3 months and less than 12 months. Patients are considered to be in sustained remission if they have not met criteria for AUD at any time during a period of 12 months or longer.

How to detect AUD

Several clues in a patient’s history can suggest AUD (TABLE 29,10). Most imbibers are unaware of the dangers and may consider themselves merely “social drinkers.” Binge drinking may be an early indicator of vulnerability to AUD and should be assessed as part of a thorough clinical evaluation.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) that clinicians screen adults ages 18 years or older for alcohol misuse.12

Studies demonstrate that both genetic and environmental factors play important roles in the development of AUD.13 A family history of excessive alcohol use increases the risk of AUD. Comorbidity of AUD and other mental health conditions is extremely common. For example, high rates of association between major depressive disorder and AUD have been observed.14

Tools to use in screening and diagnosing AUD

Screening for AUD during an office visit can be done fairly quickly. While 96% of primary care physicians screen for alcohol misuse in some way, only 38% use 1 of the 3 tools recommended by the USPSTF15—the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the abbreviated AUDIT-C, or the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) single question screen—which detect the full spectrum of alcohol misuse in adults.12 Although the commonly used CAGE questionnaire is one of the most studied self-report tools, it has lower sensitivity at a lower level of alcohol intake.16

Continue to: The NIAAA single-question screen asks...

The NIAAA single-question screen asks how many times in the past year the patient had ≥4 drinks (women) or ≥5 drinks (men) in a day.15 The sensitivity and specificity of single-question screening are 82% to 87% and 61% to 79%, respectively, and the test has been validated in several different settings.12 The AUDIT screening tool, freely available from the World Health Organization, is a 10-item questionnaire that probes an individual’s alcohol intake, alcohol dependence, and adverse consequences of alcohol use. Administration of the AUDIT typically requires only 2 minutes. AUDIT-C17 is an abbreviated version of the AUDIT questionnaire that asks 3 consumption questions to screen for AUD.

It was found that AUDIT scores in the range of 8 to 15 indicate a medium-level alcohol problem, whereas a score of ≥16 indicates a high-level alcohol problem. The AUDIT-C is scored from 0 to 12, with ≥4 indicating a problem in men and ≥3

THE CASE

The physician had used the NIAAA single- question screen to determine that Ms. E drank more than 4 beers per day during social events and weekends, which occurred 2 to 3 times per month over the past year. She lives alone and said that she’d been seeing less and less of her boyfriend lately. Her score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), which screens for depression, was 11, indicating moderate impairment. Her response on the CAGE questionnaire was negative for a problem with alcohol. However, her AUDIT score was 17, indicating a high-level alcohol problem. Based on these findings, her physician expressed concern that her alcohol use might be contributing to her symptoms and difficulties.

Although she did not have a history of increasing usage per day, a persistent desire to cut down, significant effort to obtain alcohol, or cravings, she was having work troubles and continued to drink even though it was straining relationships, promoting weight gain, and causing abdominal pain.

The physician asked her to schedule a return visit and ordered several blood studies. He also offered to connect her with a colleague with whom he collaborated who could speak with her about possible alcohol use disorders and depression.

Continue to: Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

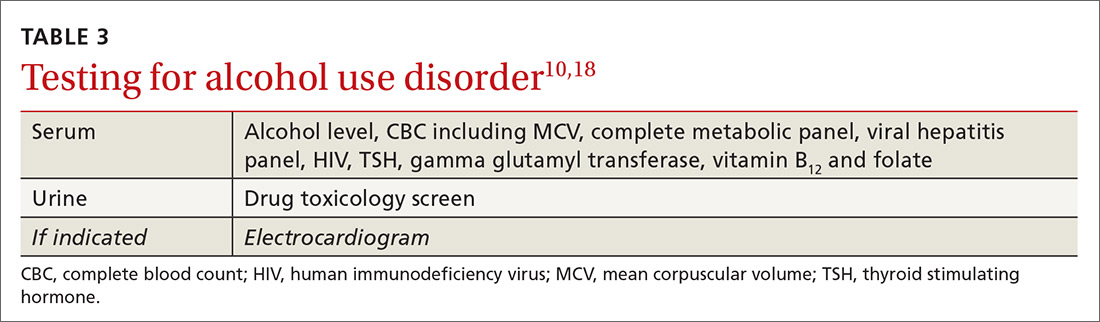

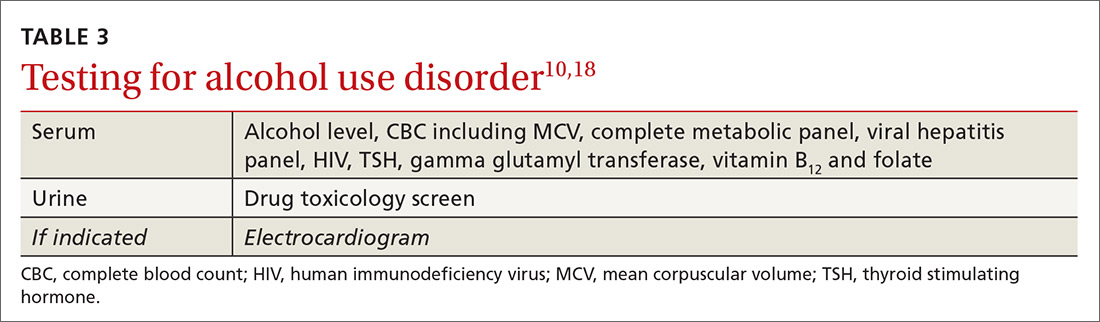

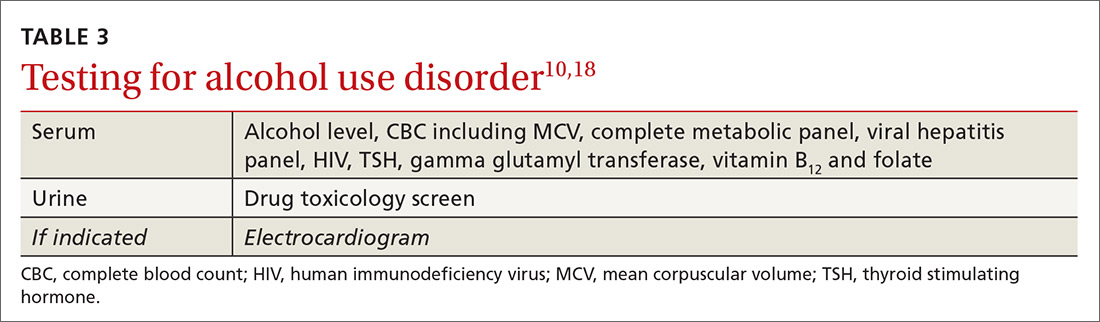

Lab tests used to measure hepatic injury due to alcohol include gamma-glutamyl-transferase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and macrocytic volume, although the indices of hepatic damage have low specificity. Elevated serum ethanol levels can reveal recent alcohol use, and vitamin deficiencies and other abnormalities can be used to differentiate other causes of hepatic inflammation and co-existing health issues (TABLE 310,18). A number of as-yet-unvalidated biomarkers are being studied to assist in screening, diagnosing, and treating AUD.18

What treatment approaches work for AUD?

Family physicians can efficiently and productively address AUD by using alcohol screening and brief intervention, which have been shown to reduce risky drinking. Reimbursement for this service is covered by such CPT codes as 99408, 99409, or H0049, or with other evaluation and management (E/M) codes by using modifier 25.

Treatment of AUD varies and should be customized to each patient’s needs, readiness, preferences, and resources. Individual and group counseling approaches can be effective, and medications are available for inpatient and outpatient settings. Psychotherapy options include brief interventions, 12-step programs (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous—https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/find-aa-resources),motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to describe these options in detail, resources are available for those who wish to learn more.19-21

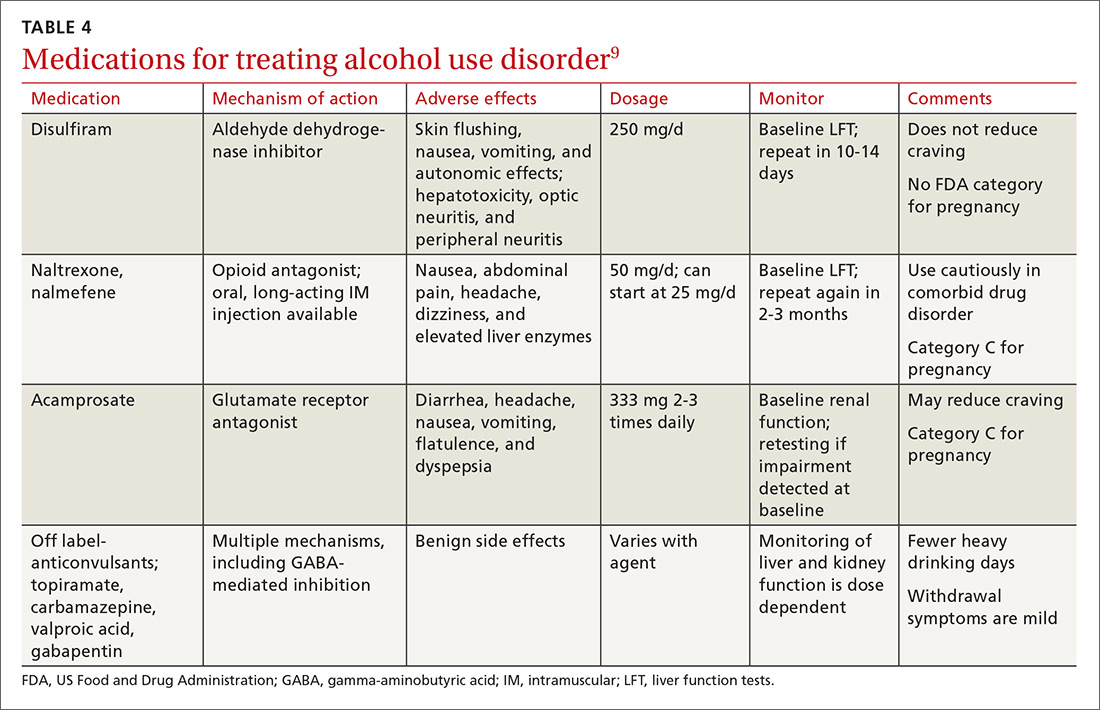

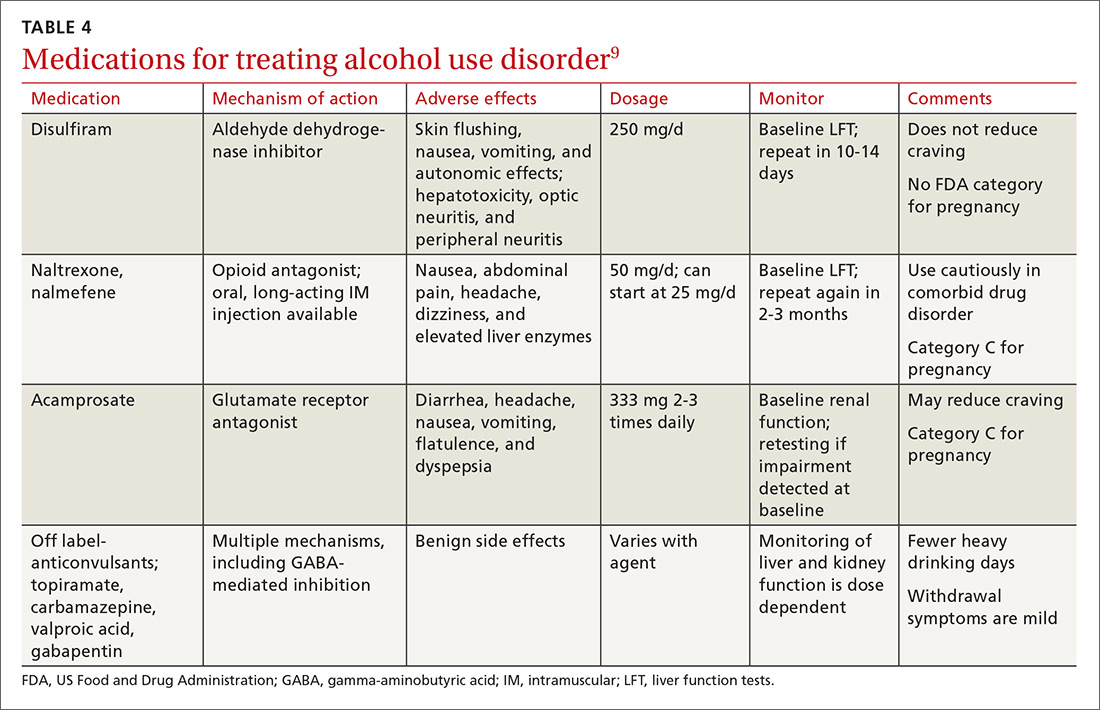

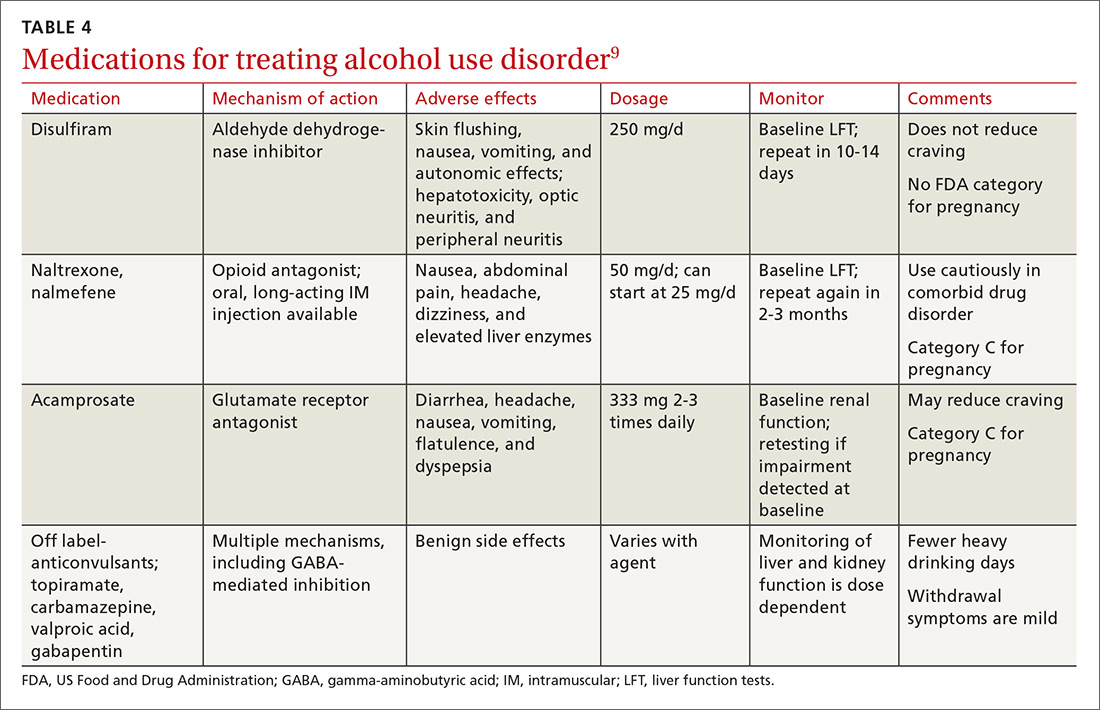

Psychopharmacologic management includes US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications such as disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate, and off-label uses of other medications (TABLE 49). Not enough empiric evidence is available to judge the effectiveness of these medications in adolescents, and the FDA has not approved them for such use. Evidence from meta-analyses comparing naltrexone and acamprosate have shown naltrexone to be more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking and cravings, while acamprosate is effective in promoting abstinence.22,23 Naltrexone combined with behavioral intervention reduces the heavy drinking days and percentage of abstinence days.24

Current guideline recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association25 include:

- Naltrexone and acamprosate are recommended to treat patients with moderate-to-severe AUD in specific circumstances (eg, when nonpharmacologic approaches have failed to produce an effect or when patients prefer to use one of these medications).

- Topiramate and gabapentin are also suggested as medications for patients with moderate-to-severe AUD, but typically after first trying naltrexone and acamprosate.

- Disulfiram generally should not be used as first-line treatment. It produces physical reactions (eg, flushing) if alcohol is consumed within 12 to 24 hours of medication use.

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Ms. E was open to the idea of decreasing her alcohol use and agreed that she was depressed. Her lab tests at follow-up were normal other than an elevated AST/ALT of 90/80 U/L. S

She continued to get counseling for her AUD and for her comorbid depression in addition to taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She is now in early remission for her alcohol use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Metro Health Medical Center, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

1. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

2. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington DC; 2013.

3. HHS. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2018.

4. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223-2233.

5. Chase V, Neild R, Sadler CW, et al. The medical complications of alcohol use: understanding mechanisms to improve management. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:253-265.

6. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:911-923.

7. Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy in primary care: a qualitative study in five VA clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:258-267.

8. Zhang DX, Li ST, Lee QK, et al. Systematic review of guidelines on managing patients with harmful use of alcohol in primary healthcare settings. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52:595-609.

9. Wackernah RC, Minnick MJ, Clapp P. Alcohol use disorder: pathophysiology, effects, and pharmacologic options for treatment. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2014;5:1-12.

10. Kattimani S, Bharadwaj B. Clinical management of alcohol withdrawal: a systematic review. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:100-108.

11. Gowin JL, Sloan ME, Stangl BL, et al. Vulnerability for alcohol use disorder and rate of alcohol consumption. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1094-1101.

12. Moyer VA; Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210-218.

13. Tarter RE, Alterman AI, Edwards KL. Vulnerability to alcoholism in men: a behavior-genetic perspective. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46:329-356.

14. Brière FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, et al. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood [published online ahead of print, October 22, 2013]. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:526-533. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007.

15. Tan CH, Hungerford DW, Denny CH, et al. Screening for alcohol misuse: practices among U.S. primary care providers, DocStyles 2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:173-180.

16. Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Kester A. The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:30-39.

17. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789-1795.

18. Nanau RM, Neuman MG. Biomolecules and biomarkers used in diagnosis of alcohol drinking and in monitoring therapeutic interventions. Biomolecules. 2015;5:1339-1385.

19. Raddock M, Martukovich R, Berko E, et al. 7 tools to help patients adopt healthier behaviors. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:97-103.

20. AHRQ. Whitlock EP, Green CA, Polen MR, et al. Behavioral Counseling Interventions in Primary Care to Reduce Risky/Harmful Alcohol Use. 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK42863/. Accessed November 17, 2018.

21. Miller WR, Baca C, Compton WM, et al. Addressing substance abuse in health care settings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:292-302.

22. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108:275-293.

23. Rosner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, et al. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:11-23.

24. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003-2017.

25. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:86-90.

THE CASE

Ms. E, a 42-year-old woman, visited her new physician for a physical exam. When asked about alcohol intake, she reported that she drank 3 to 4 beers after work and sometimes 5 to 8 beers a day on the weekends. Occasionally, she exceeded those amounts, but she didn’t feel guilty about her drinking. She was often late to work and said her relationship with her boyfriend was strained. A review of systems was positive for fatigue, poor concentration, abdominal pain, and weight gain. Her body mass index was 41, pulse 100 beats/min, blood pressure 125/75 mm Hg, and she was afebrile. Her physical exam was otherwise within normal limits.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a common and often untreated condition that is increasingly prevalent in the United States.1 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) characterizes AUD as a combination of signs and symptoms typifying alcohol abuse and dependence (discussed in a bit).2

Data from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) showed 15.7 million Americans with AUD, affecting 6.2% of the population ages 18 years or older and 2.5% of adolescents ages 12 to 17 years.3

Alcohol use and AUD account for an estimated 3.8% of all global deaths and 4.6% of global disability-adjusted life years.4 AUD adversely affects several systems (TABLE 15), and patients with AUD are sicker and more likely to die younger than those without AUD.4 In the United States, prevalence of AUD has increased in recent years among women, older adults, racial minorities, and individuals with a low education level.6

Screening for AUD is reasonable and straightforward, although diagnosis and treatment of AUD in primary care settings may be challenging due to competing clinical priorities; lack of training, resources, and support; and skepticism about the efficacy of behavioral and pharmacologic treatments.7,8 However, family physicians are in an excellent position to diagnose and help address the complex biopsychosocial needs of patients with AUD, often in collaboration with colleagues and community organizations.

Signs and symptoms of AUD

In clinical practice, at least 2 of the following 11 behaviors or symptoms are required to diagnose AUD2:

- consuming larger amounts of alcohol over a longer period than intended

- persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use

- making a significant effort to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol

In moderate-to-severe cases:

- cravings or urges to use alcohol

- recurrent failure to fulfill major work, school, or social obligations

- continued alcohol use despite recurrent social and interpersonal problems

- giving up social, occupational, and recreational activities due to alcohol

- using alcohol in physically dangerous situations

- continued alcohol use despite having physical or psychological problems

- tolerance to alcohol’s effects

- withdrawal symptoms.

Continue to: Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if...

Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if they exhibit 2 or 3 symptoms, moderate AUD with 4 or 5 symptoms, and severe AUD if there are 6 or more symptoms.2

Those who meet criteria for AUD and are able to stop using alcohol are deemed to be in early remission if the criteria have gone unfulfilled for at least 3 months and less than 12 months. Patients are considered to be in sustained remission if they have not met criteria for AUD at any time during a period of 12 months or longer.

How to detect AUD

Several clues in a patient’s history can suggest AUD (TABLE 29,10). Most imbibers are unaware of the dangers and may consider themselves merely “social drinkers.” Binge drinking may be an early indicator of vulnerability to AUD and should be assessed as part of a thorough clinical evaluation.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) that clinicians screen adults ages 18 years or older for alcohol misuse.12

Studies demonstrate that both genetic and environmental factors play important roles in the development of AUD.13 A family history of excessive alcohol use increases the risk of AUD. Comorbidity of AUD and other mental health conditions is extremely common. For example, high rates of association between major depressive disorder and AUD have been observed.14

Tools to use in screening and diagnosing AUD

Screening for AUD during an office visit can be done fairly quickly. While 96% of primary care physicians screen for alcohol misuse in some way, only 38% use 1 of the 3 tools recommended by the USPSTF15—the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the abbreviated AUDIT-C, or the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) single question screen—which detect the full spectrum of alcohol misuse in adults.12 Although the commonly used CAGE questionnaire is one of the most studied self-report tools, it has lower sensitivity at a lower level of alcohol intake.16

Continue to: The NIAAA single-question screen asks...

The NIAAA single-question screen asks how many times in the past year the patient had ≥4 drinks (women) or ≥5 drinks (men) in a day.15 The sensitivity and specificity of single-question screening are 82% to 87% and 61% to 79%, respectively, and the test has been validated in several different settings.12 The AUDIT screening tool, freely available from the World Health Organization, is a 10-item questionnaire that probes an individual’s alcohol intake, alcohol dependence, and adverse consequences of alcohol use. Administration of the AUDIT typically requires only 2 minutes. AUDIT-C17 is an abbreviated version of the AUDIT questionnaire that asks 3 consumption questions to screen for AUD.

It was found that AUDIT scores in the range of 8 to 15 indicate a medium-level alcohol problem, whereas a score of ≥16 indicates a high-level alcohol problem. The AUDIT-C is scored from 0 to 12, with ≥4 indicating a problem in men and ≥3

THE CASE

The physician had used the NIAAA single- question screen to determine that Ms. E drank more than 4 beers per day during social events and weekends, which occurred 2 to 3 times per month over the past year. She lives alone and said that she’d been seeing less and less of her boyfriend lately. Her score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), which screens for depression, was 11, indicating moderate impairment. Her response on the CAGE questionnaire was negative for a problem with alcohol. However, her AUDIT score was 17, indicating a high-level alcohol problem. Based on these findings, her physician expressed concern that her alcohol use might be contributing to her symptoms and difficulties.

Although she did not have a history of increasing usage per day, a persistent desire to cut down, significant effort to obtain alcohol, or cravings, she was having work troubles and continued to drink even though it was straining relationships, promoting weight gain, and causing abdominal pain.

The physician asked her to schedule a return visit and ordered several blood studies. He also offered to connect her with a colleague with whom he collaborated who could speak with her about possible alcohol use disorders and depression.

Continue to: Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Lab tests used to measure hepatic injury due to alcohol include gamma-glutamyl-transferase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and macrocytic volume, although the indices of hepatic damage have low specificity. Elevated serum ethanol levels can reveal recent alcohol use, and vitamin deficiencies and other abnormalities can be used to differentiate other causes of hepatic inflammation and co-existing health issues (TABLE 310,18). A number of as-yet-unvalidated biomarkers are being studied to assist in screening, diagnosing, and treating AUD.18

What treatment approaches work for AUD?

Family physicians can efficiently and productively address AUD by using alcohol screening and brief intervention, which have been shown to reduce risky drinking. Reimbursement for this service is covered by such CPT codes as 99408, 99409, or H0049, or with other evaluation and management (E/M) codes by using modifier 25.

Treatment of AUD varies and should be customized to each patient’s needs, readiness, preferences, and resources. Individual and group counseling approaches can be effective, and medications are available for inpatient and outpatient settings. Psychotherapy options include brief interventions, 12-step programs (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous—https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/find-aa-resources),motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to describe these options in detail, resources are available for those who wish to learn more.19-21

Psychopharmacologic management includes US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications such as disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate, and off-label uses of other medications (TABLE 49). Not enough empiric evidence is available to judge the effectiveness of these medications in adolescents, and the FDA has not approved them for such use. Evidence from meta-analyses comparing naltrexone and acamprosate have shown naltrexone to be more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking and cravings, while acamprosate is effective in promoting abstinence.22,23 Naltrexone combined with behavioral intervention reduces the heavy drinking days and percentage of abstinence days.24

Current guideline recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association25 include:

- Naltrexone and acamprosate are recommended to treat patients with moderate-to-severe AUD in specific circumstances (eg, when nonpharmacologic approaches have failed to produce an effect or when patients prefer to use one of these medications).

- Topiramate and gabapentin are also suggested as medications for patients with moderate-to-severe AUD, but typically after first trying naltrexone and acamprosate.

- Disulfiram generally should not be used as first-line treatment. It produces physical reactions (eg, flushing) if alcohol is consumed within 12 to 24 hours of medication use.

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Ms. E was open to the idea of decreasing her alcohol use and agreed that she was depressed. Her lab tests at follow-up were normal other than an elevated AST/ALT of 90/80 U/L. S

She continued to get counseling for her AUD and for her comorbid depression in addition to taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She is now in early remission for her alcohol use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Metro Health Medical Center, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

THE CASE

Ms. E, a 42-year-old woman, visited her new physician for a physical exam. When asked about alcohol intake, she reported that she drank 3 to 4 beers after work and sometimes 5 to 8 beers a day on the weekends. Occasionally, she exceeded those amounts, but she didn’t feel guilty about her drinking. She was often late to work and said her relationship with her boyfriend was strained. A review of systems was positive for fatigue, poor concentration, abdominal pain, and weight gain. Her body mass index was 41, pulse 100 beats/min, blood pressure 125/75 mm Hg, and she was afebrile. Her physical exam was otherwise within normal limits.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a common and often untreated condition that is increasingly prevalent in the United States.1 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) characterizes AUD as a combination of signs and symptoms typifying alcohol abuse and dependence (discussed in a bit).2

Data from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) showed 15.7 million Americans with AUD, affecting 6.2% of the population ages 18 years or older and 2.5% of adolescents ages 12 to 17 years.3

Alcohol use and AUD account for an estimated 3.8% of all global deaths and 4.6% of global disability-adjusted life years.4 AUD adversely affects several systems (TABLE 15), and patients with AUD are sicker and more likely to die younger than those without AUD.4 In the United States, prevalence of AUD has increased in recent years among women, older adults, racial minorities, and individuals with a low education level.6

Screening for AUD is reasonable and straightforward, although diagnosis and treatment of AUD in primary care settings may be challenging due to competing clinical priorities; lack of training, resources, and support; and skepticism about the efficacy of behavioral and pharmacologic treatments.7,8 However, family physicians are in an excellent position to diagnose and help address the complex biopsychosocial needs of patients with AUD, often in collaboration with colleagues and community organizations.

Signs and symptoms of AUD

In clinical practice, at least 2 of the following 11 behaviors or symptoms are required to diagnose AUD2:

- consuming larger amounts of alcohol over a longer period than intended

- persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use

- making a significant effort to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol

In moderate-to-severe cases:

- cravings or urges to use alcohol

- recurrent failure to fulfill major work, school, or social obligations

- continued alcohol use despite recurrent social and interpersonal problems

- giving up social, occupational, and recreational activities due to alcohol

- using alcohol in physically dangerous situations

- continued alcohol use despite having physical or psychological problems

- tolerance to alcohol’s effects

- withdrawal symptoms.

Continue to: Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if...

Patients meet criteria for mild AUD severity if they exhibit 2 or 3 symptoms, moderate AUD with 4 or 5 symptoms, and severe AUD if there are 6 or more symptoms.2

Those who meet criteria for AUD and are able to stop using alcohol are deemed to be in early remission if the criteria have gone unfulfilled for at least 3 months and less than 12 months. Patients are considered to be in sustained remission if they have not met criteria for AUD at any time during a period of 12 months or longer.

How to detect AUD

Several clues in a patient’s history can suggest AUD (TABLE 29,10). Most imbibers are unaware of the dangers and may consider themselves merely “social drinkers.” Binge drinking may be an early indicator of vulnerability to AUD and should be assessed as part of a thorough clinical evaluation.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) that clinicians screen adults ages 18 years or older for alcohol misuse.12

Studies demonstrate that both genetic and environmental factors play important roles in the development of AUD.13 A family history of excessive alcohol use increases the risk of AUD. Comorbidity of AUD and other mental health conditions is extremely common. For example, high rates of association between major depressive disorder and AUD have been observed.14

Tools to use in screening and diagnosing AUD

Screening for AUD during an office visit can be done fairly quickly. While 96% of primary care physicians screen for alcohol misuse in some way, only 38% use 1 of the 3 tools recommended by the USPSTF15—the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the abbreviated AUDIT-C, or the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) single question screen—which detect the full spectrum of alcohol misuse in adults.12 Although the commonly used CAGE questionnaire is one of the most studied self-report tools, it has lower sensitivity at a lower level of alcohol intake.16

Continue to: The NIAAA single-question screen asks...

The NIAAA single-question screen asks how many times in the past year the patient had ≥4 drinks (women) or ≥5 drinks (men) in a day.15 The sensitivity and specificity of single-question screening are 82% to 87% and 61% to 79%, respectively, and the test has been validated in several different settings.12 The AUDIT screening tool, freely available from the World Health Organization, is a 10-item questionnaire that probes an individual’s alcohol intake, alcohol dependence, and adverse consequences of alcohol use. Administration of the AUDIT typically requires only 2 minutes. AUDIT-C17 is an abbreviated version of the AUDIT questionnaire that asks 3 consumption questions to screen for AUD.

It was found that AUDIT scores in the range of 8 to 15 indicate a medium-level alcohol problem, whereas a score of ≥16 indicates a high-level alcohol problem. The AUDIT-C is scored from 0 to 12, with ≥4 indicating a problem in men and ≥3

THE CASE

The physician had used the NIAAA single- question screen to determine that Ms. E drank more than 4 beers per day during social events and weekends, which occurred 2 to 3 times per month over the past year. She lives alone and said that she’d been seeing less and less of her boyfriend lately. Her score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), which screens for depression, was 11, indicating moderate impairment. Her response on the CAGE questionnaire was negative for a problem with alcohol. However, her AUDIT score was 17, indicating a high-level alcohol problem. Based on these findings, her physician expressed concern that her alcohol use might be contributing to her symptoms and difficulties.

Although she did not have a history of increasing usage per day, a persistent desire to cut down, significant effort to obtain alcohol, or cravings, she was having work troubles and continued to drink even though it was straining relationships, promoting weight gain, and causing abdominal pain.

The physician asked her to schedule a return visit and ordered several blood studies. He also offered to connect her with a colleague with whom he collaborated who could speak with her about possible alcohol use disorders and depression.

Continue to: Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Selecting blood work in screening for AUD

Lab tests used to measure hepatic injury due to alcohol include gamma-glutamyl-transferase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and macrocytic volume, although the indices of hepatic damage have low specificity. Elevated serum ethanol levels can reveal recent alcohol use, and vitamin deficiencies and other abnormalities can be used to differentiate other causes of hepatic inflammation and co-existing health issues (TABLE 310,18). A number of as-yet-unvalidated biomarkers are being studied to assist in screening, diagnosing, and treating AUD.18

What treatment approaches work for AUD?

Family physicians can efficiently and productively address AUD by using alcohol screening and brief intervention, which have been shown to reduce risky drinking. Reimbursement for this service is covered by such CPT codes as 99408, 99409, or H0049, or with other evaluation and management (E/M) codes by using modifier 25.

Treatment of AUD varies and should be customized to each patient’s needs, readiness, preferences, and resources. Individual and group counseling approaches can be effective, and medications are available for inpatient and outpatient settings. Psychotherapy options include brief interventions, 12-step programs (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous—https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/find-aa-resources),motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to describe these options in detail, resources are available for those who wish to learn more.19-21

Psychopharmacologic management includes US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications such as disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate, and off-label uses of other medications (TABLE 49). Not enough empiric evidence is available to judge the effectiveness of these medications in adolescents, and the FDA has not approved them for such use. Evidence from meta-analyses comparing naltrexone and acamprosate have shown naltrexone to be more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking and cravings, while acamprosate is effective in promoting abstinence.22,23 Naltrexone combined with behavioral intervention reduces the heavy drinking days and percentage of abstinence days.24

Current guideline recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association25 include:

- Naltrexone and acamprosate are recommended to treat patients with moderate-to-severe AUD in specific circumstances (eg, when nonpharmacologic approaches have failed to produce an effect or when patients prefer to use one of these medications).

- Topiramate and gabapentin are also suggested as medications for patients with moderate-to-severe AUD, but typically after first trying naltrexone and acamprosate.

- Disulfiram generally should not be used as first-line treatment. It produces physical reactions (eg, flushing) if alcohol is consumed within 12 to 24 hours of medication use.

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Ms. E was open to the idea of decreasing her alcohol use and agreed that she was depressed. Her lab tests at follow-up were normal other than an elevated AST/ALT of 90/80 U/L. S

She continued to get counseling for her AUD and for her comorbid depression in addition to taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She is now in early remission for her alcohol use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jaividhya Dasarathy, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Metro Health Medical Center, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; [email protected].

1. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

2. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington DC; 2013.

3. HHS. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2018.

4. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223-2233.

5. Chase V, Neild R, Sadler CW, et al. The medical complications of alcohol use: understanding mechanisms to improve management. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:253-265.

6. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:911-923.

7. Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy in primary care: a qualitative study in five VA clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:258-267.

8. Zhang DX, Li ST, Lee QK, et al. Systematic review of guidelines on managing patients with harmful use of alcohol in primary healthcare settings. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52:595-609.

9. Wackernah RC, Minnick MJ, Clapp P. Alcohol use disorder: pathophysiology, effects, and pharmacologic options for treatment. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2014;5:1-12.

10. Kattimani S, Bharadwaj B. Clinical management of alcohol withdrawal: a systematic review. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:100-108.

11. Gowin JL, Sloan ME, Stangl BL, et al. Vulnerability for alcohol use disorder and rate of alcohol consumption. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1094-1101.

12. Moyer VA; Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210-218.

13. Tarter RE, Alterman AI, Edwards KL. Vulnerability to alcoholism in men: a behavior-genetic perspective. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46:329-356.

14. Brière FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, et al. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood [published online ahead of print, October 22, 2013]. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:526-533. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007.

15. Tan CH, Hungerford DW, Denny CH, et al. Screening for alcohol misuse: practices among U.S. primary care providers, DocStyles 2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:173-180.

16. Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Kester A. The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:30-39.

17. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789-1795.

18. Nanau RM, Neuman MG. Biomolecules and biomarkers used in diagnosis of alcohol drinking and in monitoring therapeutic interventions. Biomolecules. 2015;5:1339-1385.

19. Raddock M, Martukovich R, Berko E, et al. 7 tools to help patients adopt healthier behaviors. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:97-103.

20. AHRQ. Whitlock EP, Green CA, Polen MR, et al. Behavioral Counseling Interventions in Primary Care to Reduce Risky/Harmful Alcohol Use. 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK42863/. Accessed November 17, 2018.

21. Miller WR, Baca C, Compton WM, et al. Addressing substance abuse in health care settings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:292-302.

22. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108:275-293.

23. Rosner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, et al. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:11-23.

24. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003-2017.

25. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:86-90.

1. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

2. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington DC; 2013.

3. HHS. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2018.

4. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223-2233.

5. Chase V, Neild R, Sadler CW, et al. The medical complications of alcohol use: understanding mechanisms to improve management. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:253-265.

6. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:911-923.

7. Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy in primary care: a qualitative study in five VA clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:258-267.

8. Zhang DX, Li ST, Lee QK, et al. Systematic review of guidelines on managing patients with harmful use of alcohol in primary healthcare settings. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52:595-609.

9. Wackernah RC, Minnick MJ, Clapp P. Alcohol use disorder: pathophysiology, effects, and pharmacologic options for treatment. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2014;5:1-12.

10. Kattimani S, Bharadwaj B. Clinical management of alcohol withdrawal: a systematic review. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:100-108.

11. Gowin JL, Sloan ME, Stangl BL, et al. Vulnerability for alcohol use disorder and rate of alcohol consumption. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1094-1101.

12. Moyer VA; Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210-218.

13. Tarter RE, Alterman AI, Edwards KL. Vulnerability to alcoholism in men: a behavior-genetic perspective. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46:329-356.