User login

New York City inpatient detox unit keeps running: Here’s how

Substance use disorder and its daily consequences take no breaks even during a pandemic. The stressors created by COVID-19, including deaths of loved ones and the disruptions to normal life from policies aimed at flattening the curve, seem to have increased substance use.

I practice as a hospitalist with an internal medicine background and specialty in addiction medicine at BronxCare Health System’s inpatient detoxification unit, a 24/7, 20-bed medically-supervised unit in South Bronx in New York City. It is one of the comprehensive services provided by the BronxCare’s life recovery center and addiction services, which also includes an outpatient clinic, opioid treatment program, inpatient rehab, and a half-way house. Inpatient detoxification units like ours are designed to treat serious addictions and chemical dependency and prevent and treat life-threatening withdrawal symptoms and signs or complications. Our patients come from all over the city and its adjoining suburbs, including from emergency room referrals, referral clinics, courts and the justice system, walk-ins, and self-referrals.

At a time when many inpatient detoxification units within the city were temporarily closed due to fear of inpatient spread of the virus or to provide extra COVID beds in anticipation for the peak surge, we have been able to provide a needed service. In fact, several other inpatient detoxification programs within the city have been able to refer their patients to our facility.

Individuals with substance use disorder have historically been a vulnerable and underserved population and possess high risk for multiple health problems as well as preexisting conditions. Many have limited life options financially, educationally, and with housing, and encounter barriers to accessing primary health care services, including preventive services. The introduction of the COVID-19 pandemic into these patients’ precarious health situations only made things worse as many of the limited resources for patients with substance use disorder were diverted to battling the pandemic. Numerous inpatient and outpatient addiction services, for example, were temporarily shut down. This has led to an increase in domestic violence, and psychiatric decompensation, including psychosis, suicidal attempts, and worsening of medical comorbidities in these patients.

Our wake-up call came when the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in New York in early March. Within a short period of time the state became the epicenter for COVID-19. With the projection of millions of cases being positive and the number of new cases doubling every third day at the onset in New York City, we knew we had a battle brewing and needed to radically transform our mode of operation fast.

Our first task was to ensure the safety of our patients and the dedicated health workers attending to them. We streamlined the patient point of entry through one screening site, while also brushing up on our history-taking to intently screen for COVID-19. This included not just focusing on travels from China, but from Europe and other parts of the world.

Yes, we did ask patients about cough, fever, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, feeling fatigued, severe body ache, and possible contact with someone who is sick or has traveled overseas. But we were also attuned to the increased rate of community spread and the presentation of other symptoms, such as loss of taste and smell, early in the process. Hence we were able to triage patients with suspected cases to the appropriate sections of the hospital for further screening, testing, and evaluation, instead of having those patients admitted to the detox unit.

Early in the process a huddle team was instituted with daily briefing of staff lasting 30 minutes or less. This team consists of physicians, nurses, a physician assistant, a social worker, and a counselor. In addition to discussing treatment plans for the patient, they deliberate on the public health information from the hospital’s COVID-19 command center, New York State Department of Health, the Office of Mental Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concerning the latest evidence-based information. These discussions have helped us modify our policies and practices.

We instituted a no visiting rule during a short hospital stay of 5-7 days, and this was initiated weeks in advance of many institutions, including nursing homes with vulnerable populations. Our admitting criteria was reviewed to allow for admission of only those patients who absolutely needed inpatient substance use disorder treatment, including patients with severe withdrawal symptoms and signs, comorbidities, or neuropsychiatric manifestations that made them unsafe for outpatient or home detoxification. Others were triaged to the outpatient services which was amply supported with telemedicine. Rooms and designated areas of the building were earmarked as places for isolation/quarantine if suspected COVID-19 cases were identified pending testing. To assess patients’ risk of COVID-19, we do point-of-care nasopharyngeal swab testing with polymerase chain reaction.

Regarding face masks, patients and staff were fitted with ones early in the process. Additionally, staff were trained on the importance of face mask use and how to ensure you have a tight seal around the mouth and nose and were provided with other appropriate personal protective equipment. Concerning social distancing, we reduced the patient population capacity for the unit down to 50% and offered only single room admissions. Social distancing was encouraged in the unit, including in the television and recreation room and dining room, and during small treatment groups of less than six individuals. Daily temperature checks with noncontact handheld thermometers were enforced for staff and anyone coming into the life recovery center.

Patients are continuously being educated on the presentations of COVID-19 and encouraged to report any symptoms. Any staff feeling sick or having symptoms are encouraged to stay home. Rigorous and continuous cleaning of surfaces, especially of areas subjected to common use, is done frequently by the hospital housekeeping and environmental crew and is the order of the day.

Dr. Fagbemi is a hospitalist at BronxCare Health System, a not-for-profit health and teaching hospital system serving South and Central Bronx in New York. He has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Substance use disorder and its daily consequences take no breaks even during a pandemic. The stressors created by COVID-19, including deaths of loved ones and the disruptions to normal life from policies aimed at flattening the curve, seem to have increased substance use.

I practice as a hospitalist with an internal medicine background and specialty in addiction medicine at BronxCare Health System’s inpatient detoxification unit, a 24/7, 20-bed medically-supervised unit in South Bronx in New York City. It is one of the comprehensive services provided by the BronxCare’s life recovery center and addiction services, which also includes an outpatient clinic, opioid treatment program, inpatient rehab, and a half-way house. Inpatient detoxification units like ours are designed to treat serious addictions and chemical dependency and prevent and treat life-threatening withdrawal symptoms and signs or complications. Our patients come from all over the city and its adjoining suburbs, including from emergency room referrals, referral clinics, courts and the justice system, walk-ins, and self-referrals.

At a time when many inpatient detoxification units within the city were temporarily closed due to fear of inpatient spread of the virus or to provide extra COVID beds in anticipation for the peak surge, we have been able to provide a needed service. In fact, several other inpatient detoxification programs within the city have been able to refer their patients to our facility.

Individuals with substance use disorder have historically been a vulnerable and underserved population and possess high risk for multiple health problems as well as preexisting conditions. Many have limited life options financially, educationally, and with housing, and encounter barriers to accessing primary health care services, including preventive services. The introduction of the COVID-19 pandemic into these patients’ precarious health situations only made things worse as many of the limited resources for patients with substance use disorder were diverted to battling the pandemic. Numerous inpatient and outpatient addiction services, for example, were temporarily shut down. This has led to an increase in domestic violence, and psychiatric decompensation, including psychosis, suicidal attempts, and worsening of medical comorbidities in these patients.

Our wake-up call came when the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in New York in early March. Within a short period of time the state became the epicenter for COVID-19. With the projection of millions of cases being positive and the number of new cases doubling every third day at the onset in New York City, we knew we had a battle brewing and needed to radically transform our mode of operation fast.

Our first task was to ensure the safety of our patients and the dedicated health workers attending to them. We streamlined the patient point of entry through one screening site, while also brushing up on our history-taking to intently screen for COVID-19. This included not just focusing on travels from China, but from Europe and other parts of the world.

Yes, we did ask patients about cough, fever, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, feeling fatigued, severe body ache, and possible contact with someone who is sick or has traveled overseas. But we were also attuned to the increased rate of community spread and the presentation of other symptoms, such as loss of taste and smell, early in the process. Hence we were able to triage patients with suspected cases to the appropriate sections of the hospital for further screening, testing, and evaluation, instead of having those patients admitted to the detox unit.

Early in the process a huddle team was instituted with daily briefing of staff lasting 30 minutes or less. This team consists of physicians, nurses, a physician assistant, a social worker, and a counselor. In addition to discussing treatment plans for the patient, they deliberate on the public health information from the hospital’s COVID-19 command center, New York State Department of Health, the Office of Mental Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concerning the latest evidence-based information. These discussions have helped us modify our policies and practices.

We instituted a no visiting rule during a short hospital stay of 5-7 days, and this was initiated weeks in advance of many institutions, including nursing homes with vulnerable populations. Our admitting criteria was reviewed to allow for admission of only those patients who absolutely needed inpatient substance use disorder treatment, including patients with severe withdrawal symptoms and signs, comorbidities, or neuropsychiatric manifestations that made them unsafe for outpatient or home detoxification. Others were triaged to the outpatient services which was amply supported with telemedicine. Rooms and designated areas of the building were earmarked as places for isolation/quarantine if suspected COVID-19 cases were identified pending testing. To assess patients’ risk of COVID-19, we do point-of-care nasopharyngeal swab testing with polymerase chain reaction.

Regarding face masks, patients and staff were fitted with ones early in the process. Additionally, staff were trained on the importance of face mask use and how to ensure you have a tight seal around the mouth and nose and were provided with other appropriate personal protective equipment. Concerning social distancing, we reduced the patient population capacity for the unit down to 50% and offered only single room admissions. Social distancing was encouraged in the unit, including in the television and recreation room and dining room, and during small treatment groups of less than six individuals. Daily temperature checks with noncontact handheld thermometers were enforced for staff and anyone coming into the life recovery center.

Patients are continuously being educated on the presentations of COVID-19 and encouraged to report any symptoms. Any staff feeling sick or having symptoms are encouraged to stay home. Rigorous and continuous cleaning of surfaces, especially of areas subjected to common use, is done frequently by the hospital housekeeping and environmental crew and is the order of the day.

Dr. Fagbemi is a hospitalist at BronxCare Health System, a not-for-profit health and teaching hospital system serving South and Central Bronx in New York. He has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Substance use disorder and its daily consequences take no breaks even during a pandemic. The stressors created by COVID-19, including deaths of loved ones and the disruptions to normal life from policies aimed at flattening the curve, seem to have increased substance use.

I practice as a hospitalist with an internal medicine background and specialty in addiction medicine at BronxCare Health System’s inpatient detoxification unit, a 24/7, 20-bed medically-supervised unit in South Bronx in New York City. It is one of the comprehensive services provided by the BronxCare’s life recovery center and addiction services, which also includes an outpatient clinic, opioid treatment program, inpatient rehab, and a half-way house. Inpatient detoxification units like ours are designed to treat serious addictions and chemical dependency and prevent and treat life-threatening withdrawal symptoms and signs or complications. Our patients come from all over the city and its adjoining suburbs, including from emergency room referrals, referral clinics, courts and the justice system, walk-ins, and self-referrals.

At a time when many inpatient detoxification units within the city were temporarily closed due to fear of inpatient spread of the virus or to provide extra COVID beds in anticipation for the peak surge, we have been able to provide a needed service. In fact, several other inpatient detoxification programs within the city have been able to refer their patients to our facility.

Individuals with substance use disorder have historically been a vulnerable and underserved population and possess high risk for multiple health problems as well as preexisting conditions. Many have limited life options financially, educationally, and with housing, and encounter barriers to accessing primary health care services, including preventive services. The introduction of the COVID-19 pandemic into these patients’ precarious health situations only made things worse as many of the limited resources for patients with substance use disorder were diverted to battling the pandemic. Numerous inpatient and outpatient addiction services, for example, were temporarily shut down. This has led to an increase in domestic violence, and psychiatric decompensation, including psychosis, suicidal attempts, and worsening of medical comorbidities in these patients.

Our wake-up call came when the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in New York in early March. Within a short period of time the state became the epicenter for COVID-19. With the projection of millions of cases being positive and the number of new cases doubling every third day at the onset in New York City, we knew we had a battle brewing and needed to radically transform our mode of operation fast.

Our first task was to ensure the safety of our patients and the dedicated health workers attending to them. We streamlined the patient point of entry through one screening site, while also brushing up on our history-taking to intently screen for COVID-19. This included not just focusing on travels from China, but from Europe and other parts of the world.

Yes, we did ask patients about cough, fever, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, feeling fatigued, severe body ache, and possible contact with someone who is sick or has traveled overseas. But we were also attuned to the increased rate of community spread and the presentation of other symptoms, such as loss of taste and smell, early in the process. Hence we were able to triage patients with suspected cases to the appropriate sections of the hospital for further screening, testing, and evaluation, instead of having those patients admitted to the detox unit.

Early in the process a huddle team was instituted with daily briefing of staff lasting 30 minutes or less. This team consists of physicians, nurses, a physician assistant, a social worker, and a counselor. In addition to discussing treatment plans for the patient, they deliberate on the public health information from the hospital’s COVID-19 command center, New York State Department of Health, the Office of Mental Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concerning the latest evidence-based information. These discussions have helped us modify our policies and practices.

We instituted a no visiting rule during a short hospital stay of 5-7 days, and this was initiated weeks in advance of many institutions, including nursing homes with vulnerable populations. Our admitting criteria was reviewed to allow for admission of only those patients who absolutely needed inpatient substance use disorder treatment, including patients with severe withdrawal symptoms and signs, comorbidities, or neuropsychiatric manifestations that made them unsafe for outpatient or home detoxification. Others were triaged to the outpatient services which was amply supported with telemedicine. Rooms and designated areas of the building were earmarked as places for isolation/quarantine if suspected COVID-19 cases were identified pending testing. To assess patients’ risk of COVID-19, we do point-of-care nasopharyngeal swab testing with polymerase chain reaction.

Regarding face masks, patients and staff were fitted with ones early in the process. Additionally, staff were trained on the importance of face mask use and how to ensure you have a tight seal around the mouth and nose and were provided with other appropriate personal protective equipment. Concerning social distancing, we reduced the patient population capacity for the unit down to 50% and offered only single room admissions. Social distancing was encouraged in the unit, including in the television and recreation room and dining room, and during small treatment groups of less than six individuals. Daily temperature checks with noncontact handheld thermometers were enforced for staff and anyone coming into the life recovery center.

Patients are continuously being educated on the presentations of COVID-19 and encouraged to report any symptoms. Any staff feeling sick or having symptoms are encouraged to stay home. Rigorous and continuous cleaning of surfaces, especially of areas subjected to common use, is done frequently by the hospital housekeeping and environmental crew and is the order of the day.

Dr. Fagbemi is a hospitalist at BronxCare Health System, a not-for-profit health and teaching hospital system serving South and Central Bronx in New York. He has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Domestic abuse linked to cardiac disease, mortality in women

Adult female survivors of domestic abuse were at least one-third more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and all-cause mortality over a short follow-up period, although they did not face a higher risk of hypertension, a new British study finds.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, provides more evidence of a link between domestic abuse and poor health, even in younger women.

“The prevalence of domestic abuse is vast, so any increased risk in cardiometabolic disease may translate into a large burden of potentially preventable illness in society,” said study lead author Joht Singh Chandan, PhD, MBBS, of the University of Birmingham (England) and University of Warwick in Coventry, England, in an interview.

The researchers retrospectively tracked primary care patients in the United Kingdom from 1995-2017. They compared 18,547 adult female survivors of domestic abuse with a group of 72,231 other women who were matched to them at baseline by age, body mass index, smoking status, and a measure known as the Townsend deprivation score.

The average age of women in the groups was 37 years plus or minus 13 in the domestic abuse group and 37 years plus or minus 12 in the unexposed group. In both groups, 45% of women smoked; women in the domestic abuse group were more likely to drink excessively (10%), compared with those in the unexposed group (4%).

Researchers followed the women in the domestic abuse group for an average of 2 years and the unexposed group for 3 years. Those in the domestic abuse group were more likely to fall out of the study because they transferred to other medical practices.

Over the study period, 181 women in the domestic abuse group and 644 women in the unexposed group developed cardiovascular disease outcomes (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.55; P = .001). They were also more likely to develop type 2 diabetes (adjusted IRR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.30-1.76; P less than .001) and all-cause mortality (adjusted IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.24-1.67; P less than.001). But there was no increased risk of hypertension (adjusted IRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.88-1.12; P = 0.873).

Why might exposure to domestic abuse boost cardiovascular risk? “Although our study was not able to answer exactly why this relationship exists, Dr. Chandan said. “These can be broadly put into three categories: adoption of poor lifestyle behaviors due to difficult circumstances (physical inactivity, poor diet, disrupted sleep, substance misuse and smoking); associated development of mental ill health; and the alteration of the immune, metabolic, neuroendocrine, and autonomic nervous system due to the impact of stress on the body.”

It’s not clear why the risk of hypertension may be an outlier among cardiovascular outcomes, Dr. Chandan said. However, he pointed to a similar study whose results hinted that survivors of emotional abuse may be more susceptible to a negative impact on hypertension (Ann Epidemiol. 2012 Aug;22[8]:562-7). The new study does not provide information about the type of abuse suffered by subjects.

Adrienne O’Neil, PhD, a family violence practitioner and cardiovascular epidemiologist at Deakin University in Geelong, Australia, said in an interview that the study is “a very useful contribution to the literature.” However, she cautioned that the study might have missed cases of domestic abuse because it relies on reports from primary care practitioners.

As for the findings, she said they’re surprising because of the divergence of major cardiovascular outcomes such as ischemic heart disease and stroke in groups of women with an average age of 37. “These differential health outcomes were observed over a 2-3 period. You probably wouldn’t expect to see a divergence in cardiovascular outcomes for 5-10 years in this age group.”

Dr. O’Neil said that, moving forward, the research can be helpful to understanding the rise of cardiovascular disease in women aged 35-54, especially in the United States. “The way we assess an individual’s risk of having a heart attack in the future is largely guided by evidence based on men. For a long time, this has neglected female-specific risk factors like polycystic ovary syndrome and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy but also conditions and exposures to which young women are especially vulnerable like depression, anxiety and [domestic abuse],” she said.

“This research is important as it gives us clues about who may be at elevated risk to help us guide prevention efforts. Equally, there is some evidence that chest pain presentation may be a useful predictor of domestic abuse victimization so there could be multiple lines of further inquiry.”

Dr. Chandan, the other study authors, and Dr. O’Neil reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chandan JS et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014580.

Adult female survivors of domestic abuse were at least one-third more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and all-cause mortality over a short follow-up period, although they did not face a higher risk of hypertension, a new British study finds.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, provides more evidence of a link between domestic abuse and poor health, even in younger women.

“The prevalence of domestic abuse is vast, so any increased risk in cardiometabolic disease may translate into a large burden of potentially preventable illness in society,” said study lead author Joht Singh Chandan, PhD, MBBS, of the University of Birmingham (England) and University of Warwick in Coventry, England, in an interview.

The researchers retrospectively tracked primary care patients in the United Kingdom from 1995-2017. They compared 18,547 adult female survivors of domestic abuse with a group of 72,231 other women who were matched to them at baseline by age, body mass index, smoking status, and a measure known as the Townsend deprivation score.

The average age of women in the groups was 37 years plus or minus 13 in the domestic abuse group and 37 years plus or minus 12 in the unexposed group. In both groups, 45% of women smoked; women in the domestic abuse group were more likely to drink excessively (10%), compared with those in the unexposed group (4%).

Researchers followed the women in the domestic abuse group for an average of 2 years and the unexposed group for 3 years. Those in the domestic abuse group were more likely to fall out of the study because they transferred to other medical practices.

Over the study period, 181 women in the domestic abuse group and 644 women in the unexposed group developed cardiovascular disease outcomes (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.55; P = .001). They were also more likely to develop type 2 diabetes (adjusted IRR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.30-1.76; P less than .001) and all-cause mortality (adjusted IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.24-1.67; P less than.001). But there was no increased risk of hypertension (adjusted IRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.88-1.12; P = 0.873).

Why might exposure to domestic abuse boost cardiovascular risk? “Although our study was not able to answer exactly why this relationship exists, Dr. Chandan said. “These can be broadly put into three categories: adoption of poor lifestyle behaviors due to difficult circumstances (physical inactivity, poor diet, disrupted sleep, substance misuse and smoking); associated development of mental ill health; and the alteration of the immune, metabolic, neuroendocrine, and autonomic nervous system due to the impact of stress on the body.”

It’s not clear why the risk of hypertension may be an outlier among cardiovascular outcomes, Dr. Chandan said. However, he pointed to a similar study whose results hinted that survivors of emotional abuse may be more susceptible to a negative impact on hypertension (Ann Epidemiol. 2012 Aug;22[8]:562-7). The new study does not provide information about the type of abuse suffered by subjects.

Adrienne O’Neil, PhD, a family violence practitioner and cardiovascular epidemiologist at Deakin University in Geelong, Australia, said in an interview that the study is “a very useful contribution to the literature.” However, she cautioned that the study might have missed cases of domestic abuse because it relies on reports from primary care practitioners.

As for the findings, she said they’re surprising because of the divergence of major cardiovascular outcomes such as ischemic heart disease and stroke in groups of women with an average age of 37. “These differential health outcomes were observed over a 2-3 period. You probably wouldn’t expect to see a divergence in cardiovascular outcomes for 5-10 years in this age group.”

Dr. O’Neil said that, moving forward, the research can be helpful to understanding the rise of cardiovascular disease in women aged 35-54, especially in the United States. “The way we assess an individual’s risk of having a heart attack in the future is largely guided by evidence based on men. For a long time, this has neglected female-specific risk factors like polycystic ovary syndrome and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy but also conditions and exposures to which young women are especially vulnerable like depression, anxiety and [domestic abuse],” she said.

“This research is important as it gives us clues about who may be at elevated risk to help us guide prevention efforts. Equally, there is some evidence that chest pain presentation may be a useful predictor of domestic abuse victimization so there could be multiple lines of further inquiry.”

Dr. Chandan, the other study authors, and Dr. O’Neil reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chandan JS et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014580.

Adult female survivors of domestic abuse were at least one-third more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and all-cause mortality over a short follow-up period, although they did not face a higher risk of hypertension, a new British study finds.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, provides more evidence of a link between domestic abuse and poor health, even in younger women.

“The prevalence of domestic abuse is vast, so any increased risk in cardiometabolic disease may translate into a large burden of potentially preventable illness in society,” said study lead author Joht Singh Chandan, PhD, MBBS, of the University of Birmingham (England) and University of Warwick in Coventry, England, in an interview.

The researchers retrospectively tracked primary care patients in the United Kingdom from 1995-2017. They compared 18,547 adult female survivors of domestic abuse with a group of 72,231 other women who were matched to them at baseline by age, body mass index, smoking status, and a measure known as the Townsend deprivation score.

The average age of women in the groups was 37 years plus or minus 13 in the domestic abuse group and 37 years plus or minus 12 in the unexposed group. In both groups, 45% of women smoked; women in the domestic abuse group were more likely to drink excessively (10%), compared with those in the unexposed group (4%).

Researchers followed the women in the domestic abuse group for an average of 2 years and the unexposed group for 3 years. Those in the domestic abuse group were more likely to fall out of the study because they transferred to other medical practices.

Over the study period, 181 women in the domestic abuse group and 644 women in the unexposed group developed cardiovascular disease outcomes (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.55; P = .001). They were also more likely to develop type 2 diabetes (adjusted IRR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.30-1.76; P less than .001) and all-cause mortality (adjusted IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.24-1.67; P less than.001). But there was no increased risk of hypertension (adjusted IRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.88-1.12; P = 0.873).

Why might exposure to domestic abuse boost cardiovascular risk? “Although our study was not able to answer exactly why this relationship exists, Dr. Chandan said. “These can be broadly put into three categories: adoption of poor lifestyle behaviors due to difficult circumstances (physical inactivity, poor diet, disrupted sleep, substance misuse and smoking); associated development of mental ill health; and the alteration of the immune, metabolic, neuroendocrine, and autonomic nervous system due to the impact of stress on the body.”

It’s not clear why the risk of hypertension may be an outlier among cardiovascular outcomes, Dr. Chandan said. However, he pointed to a similar study whose results hinted that survivors of emotional abuse may be more susceptible to a negative impact on hypertension (Ann Epidemiol. 2012 Aug;22[8]:562-7). The new study does not provide information about the type of abuse suffered by subjects.

Adrienne O’Neil, PhD, a family violence practitioner and cardiovascular epidemiologist at Deakin University in Geelong, Australia, said in an interview that the study is “a very useful contribution to the literature.” However, she cautioned that the study might have missed cases of domestic abuse because it relies on reports from primary care practitioners.

As for the findings, she said they’re surprising because of the divergence of major cardiovascular outcomes such as ischemic heart disease and stroke in groups of women with an average age of 37. “These differential health outcomes were observed over a 2-3 period. You probably wouldn’t expect to see a divergence in cardiovascular outcomes for 5-10 years in this age group.”

Dr. O’Neil said that, moving forward, the research can be helpful to understanding the rise of cardiovascular disease in women aged 35-54, especially in the United States. “The way we assess an individual’s risk of having a heart attack in the future is largely guided by evidence based on men. For a long time, this has neglected female-specific risk factors like polycystic ovary syndrome and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy but also conditions and exposures to which young women are especially vulnerable like depression, anxiety and [domestic abuse],” she said.

“This research is important as it gives us clues about who may be at elevated risk to help us guide prevention efforts. Equally, there is some evidence that chest pain presentation may be a useful predictor of domestic abuse victimization so there could be multiple lines of further inquiry.”

Dr. Chandan, the other study authors, and Dr. O’Neil reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chandan JS et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014580.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Movement-based yoga ‘viable’ for depression in many mental disorders

Movement-based yoga appears to ease depressive symptoms in a wide range of mental health disorders, a new systematic review and meta-analysis suggest.

Results of the research, which included 19 studies and more than 1,000 patients with a variety of mental health diagnoses, showed that those who practiced yoga experienced greater reductions in depressive symptoms versus those undergoing no treatment, usual treatment, or attention-control exercises. In addition, there was a dose-dependent effect such that more weekly yoga sessions were associated with the greatest reduction in depressive symptoms.

“Once we reviewed all the existing science about the mental health benefits of movement-based yoga, we found that movement-based yoga – which is the same thing as postural yoga or asana – helped reduce symptoms of depression,” study investigator Jacinta Brinsley, BClinExPhys, of the University of South Australia, Adelaide, said in an interview.

“We also found those who practiced more frequently had bigger reductions. However, it didn’t matter how long the individual sessions were; what mattered was how many times per week people practiced,” she added.

The researchers noted that the study is the first to focus specifically on movement-based yoga.

“We excluded meditative forms of yoga, which have often been included in previous reviews, yielding mixed findings. The other thing we’ve done a bit differently is pool all the different diagnoses together and then look at depressive symptoms across them,” said Ms. Brinsley.

The study was published online May 18 in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Getting clarity

Depressive disorders are currently the world’s leading cause of disability, affecting more than 340 million people.

Most individuals who suffer from depressive disorders also experience a host of physical comorbidities including obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.

Perhaps not surprisingly, physical inactivity is also associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, which may be the reason some international organizations now recommend that physical activity be included as part of routine psychiatric care.

One potential form of exercise is yoga, which has become popular in Western culture, including among psychiatric patients. Although previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the effects of various yoga interventions on mental health, none has investigated the benefits of yoga across a range of psychiatric diagnoses.

What’s more, the authors of these reviews all urge caution when interpreting their results because of potential heterogeneity of the various yoga interventions, as well as poor methodological reporting.

“As an exercise physiologist, I prescribe evidence-based treatment,” said Ms. Brinsley. “I was interested in seeing if there’s evidence to support movement-based yoga in people who were struggling with mental health or who had a diagnosed mental illness.

“The [previous] findings are quite contradictory and there’s not a clear outcome in terms of intervention results, so we pooled the data and ran the meta-analysis, thinking it would be a great way to add some important evidence to the science,” she added.

To allow for a more comprehensive assessment of yoga’s potential mental health benefits, the investigators included a range of mental health diagnoses.

Dose-dependent effect

Studies were only included in the analysis if they were randomized, controlled trials with a yoga intervention that had a minimum of 50% physical activity during each session in adults with a recognized diagnosed mental disorder. Control conditions were defined as treatment as usual, wait list, or attention controls.

Two investigators independently scanned article titles and abstracts, and a final list of articles for the study was decided by consensus. Study quality was reported using the PEDro checklist; a random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software.

A total of 3,880 records were identified and screened. The investigators assessed full-text versions of 80 articles, 19 of which (1,080 patients) were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Of these, nine studies included patients with a depressive disorder; five trials were in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, three studies included patients with a diagnosis of PTSD, one study included patients diagnosed with alcohol dependence, and one study included patients with a range of psychiatric disorders.

Of the 1,080 patients included in the review, 578 were assigned to yoga and 502 to control conditions. Yoga practice involved a mixture of movement, breathing exercises, and/or mindfulness, but the movement component took up more than half of each session.

The yoga interventions lasted an average of 2.4 months (range, 1.5-2.5 months), with an average of 1.6 sessions per week (range, 1-3 sessions) that lasted an average of 60 minutes (range, 20-90 minutes).

Of the 19 studies (632 patients), 13 reported changes in depressive symptoms and were therefore included in the meta-analysis. The six studies excluded from the quantitative analysis did not report depression symptom scores.

With respect to primary outcomes, individuals who performed yoga showed a greater reduction in depressive symptoms, compared with the three control groups (standardized mean difference, –0.41; 95% CI, –0.65 to –0.17; P < .001).

Specific subgroup analyses showed a moderate effect of yoga on depressive symptoms, compared with wait-list controls (SMD, –0.58; P < .05), treatment as usual (SMD, –0.39; P = .31), and attention controls (SMD, –0.21; P = .22).

Subgroup analyses were also performed with respect to diagnostic category. These data showed a moderate effect of yoga on depressive symptoms in depressive disorders (SMD, –0.40; P < .01), no effect in PTSD (SMD, –0.01; P = .95), a nominal effect in alcohol use disorders (SMD, –0.24; P = .69), and a marked effect in schizophrenia (SMD, –0.90; P < .01).

Movement may be key

Researchers also performed a series of meta-regression analyses, which showed that the number of yoga sessions performed each week had a significant effect on depressive symptoms. Indeed, individuals with higher session frequencies demonstrated a greater improvement in symptoms (beta, –0.44; P < .001).

These findings, said Ms. Brinsley, suggest yoga may be a viable intervention for managing depressive symptoms in patients with a variety of mental disorders.

Based on these findings, along with other conventional forms of exercise.

Equally important was the finding that the number of weekly yoga sessions moderated the effect of depressive symptoms, as it may inform the future design of yoga interventions in patients with mental disorders.

With this in mind, the researchers recommended that such interventions should aim to increase the frequency or weekly sessions rather than the duration of each individual session or the overall duration of the intervention.

However, said Ms. Brinsley, these findings suggest it is the physical aspect of the yoga practice that may be key.

“Yoga comprises several different components, including the movement postures, the breathing component, and the mindfulness or meditative component, but in this meta-analysis we looked specifically at yoga that was at least 50% movement based. So it might have also included mindfulness and breathing, but it had to have the movement,” she said.

Don’t discount meditation

Commenting on the findings, Holger Cramer, MSc, PhD, DSc, who was not involved in the study, noted that the systematic review and meta-analysis builds on a number of previous reviews regarding the benefits of yoga for mental disorders.

“Surprisingly, the largest effect in this analysis was found in schizophrenia, even higher than in patients with depressive disorders,” said Dr. Cramer of the University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany). “This is in strong contradiction to what would otherwise be expected. As the authors point out, only about a quarter of all schizophrenia patients suffer from depression, so there should not be so much room for improvement.”

Dr. Cramer also advised against reducing yoga to simply a physical undertaking. “We have shown in our meta-analysis that those interventions focusing on meditation and/or breathing techniques are the most effective ones,” he added.

As such, he urged that breathing techniques be a part of yoga for treating depression in psychiatric disorders, though care should be taken in patients with PTSD, “since breath control might be perceived as unpleasant.”

For Ms. Brinsley, the findings help solidify yoga’s potential as a genuine treatment option for a variety of mental health patients suffering depressive symptoms.

“It’s about acknowledging that yoga can be a helpful part of treatment and can have a significant effect on mental health,” she noted.

At the same time, practitioners also need to acknowledge that patients suffering from mental health disorders may struggle with motivation when it comes to activities such as yoga.

“Engaging in a new activity can be particularly challenging if you’re struggling with mental health. Nevertheless, it’s important for people to have a choice and do something they enjoy. And yoga can be another tool in their toolbox for managing their mental health,” she said.

The study was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and Health Education England. Ms. Brinsley and Dr. Cramer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Movement-based yoga appears to ease depressive symptoms in a wide range of mental health disorders, a new systematic review and meta-analysis suggest.

Results of the research, which included 19 studies and more than 1,000 patients with a variety of mental health diagnoses, showed that those who practiced yoga experienced greater reductions in depressive symptoms versus those undergoing no treatment, usual treatment, or attention-control exercises. In addition, there was a dose-dependent effect such that more weekly yoga sessions were associated with the greatest reduction in depressive symptoms.

“Once we reviewed all the existing science about the mental health benefits of movement-based yoga, we found that movement-based yoga – which is the same thing as postural yoga or asana – helped reduce symptoms of depression,” study investigator Jacinta Brinsley, BClinExPhys, of the University of South Australia, Adelaide, said in an interview.

“We also found those who practiced more frequently had bigger reductions. However, it didn’t matter how long the individual sessions were; what mattered was how many times per week people practiced,” she added.

The researchers noted that the study is the first to focus specifically on movement-based yoga.

“We excluded meditative forms of yoga, which have often been included in previous reviews, yielding mixed findings. The other thing we’ve done a bit differently is pool all the different diagnoses together and then look at depressive symptoms across them,” said Ms. Brinsley.

The study was published online May 18 in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Getting clarity

Depressive disorders are currently the world’s leading cause of disability, affecting more than 340 million people.

Most individuals who suffer from depressive disorders also experience a host of physical comorbidities including obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.

Perhaps not surprisingly, physical inactivity is also associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, which may be the reason some international organizations now recommend that physical activity be included as part of routine psychiatric care.

One potential form of exercise is yoga, which has become popular in Western culture, including among psychiatric patients. Although previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the effects of various yoga interventions on mental health, none has investigated the benefits of yoga across a range of psychiatric diagnoses.

What’s more, the authors of these reviews all urge caution when interpreting their results because of potential heterogeneity of the various yoga interventions, as well as poor methodological reporting.

“As an exercise physiologist, I prescribe evidence-based treatment,” said Ms. Brinsley. “I was interested in seeing if there’s evidence to support movement-based yoga in people who were struggling with mental health or who had a diagnosed mental illness.

“The [previous] findings are quite contradictory and there’s not a clear outcome in terms of intervention results, so we pooled the data and ran the meta-analysis, thinking it would be a great way to add some important evidence to the science,” she added.

To allow for a more comprehensive assessment of yoga’s potential mental health benefits, the investigators included a range of mental health diagnoses.

Dose-dependent effect

Studies were only included in the analysis if they were randomized, controlled trials with a yoga intervention that had a minimum of 50% physical activity during each session in adults with a recognized diagnosed mental disorder. Control conditions were defined as treatment as usual, wait list, or attention controls.

Two investigators independently scanned article titles and abstracts, and a final list of articles for the study was decided by consensus. Study quality was reported using the PEDro checklist; a random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software.

A total of 3,880 records were identified and screened. The investigators assessed full-text versions of 80 articles, 19 of which (1,080 patients) were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Of these, nine studies included patients with a depressive disorder; five trials were in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, three studies included patients with a diagnosis of PTSD, one study included patients diagnosed with alcohol dependence, and one study included patients with a range of psychiatric disorders.

Of the 1,080 patients included in the review, 578 were assigned to yoga and 502 to control conditions. Yoga practice involved a mixture of movement, breathing exercises, and/or mindfulness, but the movement component took up more than half of each session.

The yoga interventions lasted an average of 2.4 months (range, 1.5-2.5 months), with an average of 1.6 sessions per week (range, 1-3 sessions) that lasted an average of 60 minutes (range, 20-90 minutes).

Of the 19 studies (632 patients), 13 reported changes in depressive symptoms and were therefore included in the meta-analysis. The six studies excluded from the quantitative analysis did not report depression symptom scores.

With respect to primary outcomes, individuals who performed yoga showed a greater reduction in depressive symptoms, compared with the three control groups (standardized mean difference, –0.41; 95% CI, –0.65 to –0.17; P < .001).

Specific subgroup analyses showed a moderate effect of yoga on depressive symptoms, compared with wait-list controls (SMD, –0.58; P < .05), treatment as usual (SMD, –0.39; P = .31), and attention controls (SMD, –0.21; P = .22).

Subgroup analyses were also performed with respect to diagnostic category. These data showed a moderate effect of yoga on depressive symptoms in depressive disorders (SMD, –0.40; P < .01), no effect in PTSD (SMD, –0.01; P = .95), a nominal effect in alcohol use disorders (SMD, –0.24; P = .69), and a marked effect in schizophrenia (SMD, –0.90; P < .01).

Movement may be key

Researchers also performed a series of meta-regression analyses, which showed that the number of yoga sessions performed each week had a significant effect on depressive symptoms. Indeed, individuals with higher session frequencies demonstrated a greater improvement in symptoms (beta, –0.44; P < .001).

These findings, said Ms. Brinsley, suggest yoga may be a viable intervention for managing depressive symptoms in patients with a variety of mental disorders.

Based on these findings, along with other conventional forms of exercise.

Equally important was the finding that the number of weekly yoga sessions moderated the effect of depressive symptoms, as it may inform the future design of yoga interventions in patients with mental disorders.

With this in mind, the researchers recommended that such interventions should aim to increase the frequency or weekly sessions rather than the duration of each individual session or the overall duration of the intervention.

However, said Ms. Brinsley, these findings suggest it is the physical aspect of the yoga practice that may be key.

“Yoga comprises several different components, including the movement postures, the breathing component, and the mindfulness or meditative component, but in this meta-analysis we looked specifically at yoga that was at least 50% movement based. So it might have also included mindfulness and breathing, but it had to have the movement,” she said.

Don’t discount meditation

Commenting on the findings, Holger Cramer, MSc, PhD, DSc, who was not involved in the study, noted that the systematic review and meta-analysis builds on a number of previous reviews regarding the benefits of yoga for mental disorders.

“Surprisingly, the largest effect in this analysis was found in schizophrenia, even higher than in patients with depressive disorders,” said Dr. Cramer of the University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany). “This is in strong contradiction to what would otherwise be expected. As the authors point out, only about a quarter of all schizophrenia patients suffer from depression, so there should not be so much room for improvement.”

Dr. Cramer also advised against reducing yoga to simply a physical undertaking. “We have shown in our meta-analysis that those interventions focusing on meditation and/or breathing techniques are the most effective ones,” he added.

As such, he urged that breathing techniques be a part of yoga for treating depression in psychiatric disorders, though care should be taken in patients with PTSD, “since breath control might be perceived as unpleasant.”

For Ms. Brinsley, the findings help solidify yoga’s potential as a genuine treatment option for a variety of mental health patients suffering depressive symptoms.

“It’s about acknowledging that yoga can be a helpful part of treatment and can have a significant effect on mental health,” she noted.

At the same time, practitioners also need to acknowledge that patients suffering from mental health disorders may struggle with motivation when it comes to activities such as yoga.

“Engaging in a new activity can be particularly challenging if you’re struggling with mental health. Nevertheless, it’s important for people to have a choice and do something they enjoy. And yoga can be another tool in their toolbox for managing their mental health,” she said.

The study was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and Health Education England. Ms. Brinsley and Dr. Cramer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Movement-based yoga appears to ease depressive symptoms in a wide range of mental health disorders, a new systematic review and meta-analysis suggest.

Results of the research, which included 19 studies and more than 1,000 patients with a variety of mental health diagnoses, showed that those who practiced yoga experienced greater reductions in depressive symptoms versus those undergoing no treatment, usual treatment, or attention-control exercises. In addition, there was a dose-dependent effect such that more weekly yoga sessions were associated with the greatest reduction in depressive symptoms.

“Once we reviewed all the existing science about the mental health benefits of movement-based yoga, we found that movement-based yoga – which is the same thing as postural yoga or asana – helped reduce symptoms of depression,” study investigator Jacinta Brinsley, BClinExPhys, of the University of South Australia, Adelaide, said in an interview.

“We also found those who practiced more frequently had bigger reductions. However, it didn’t matter how long the individual sessions were; what mattered was how many times per week people practiced,” she added.

The researchers noted that the study is the first to focus specifically on movement-based yoga.

“We excluded meditative forms of yoga, which have often been included in previous reviews, yielding mixed findings. The other thing we’ve done a bit differently is pool all the different diagnoses together and then look at depressive symptoms across them,” said Ms. Brinsley.

The study was published online May 18 in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Getting clarity

Depressive disorders are currently the world’s leading cause of disability, affecting more than 340 million people.

Most individuals who suffer from depressive disorders also experience a host of physical comorbidities including obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.

Perhaps not surprisingly, physical inactivity is also associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, which may be the reason some international organizations now recommend that physical activity be included as part of routine psychiatric care.

One potential form of exercise is yoga, which has become popular in Western culture, including among psychiatric patients. Although previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the effects of various yoga interventions on mental health, none has investigated the benefits of yoga across a range of psychiatric diagnoses.

What’s more, the authors of these reviews all urge caution when interpreting their results because of potential heterogeneity of the various yoga interventions, as well as poor methodological reporting.

“As an exercise physiologist, I prescribe evidence-based treatment,” said Ms. Brinsley. “I was interested in seeing if there’s evidence to support movement-based yoga in people who were struggling with mental health or who had a diagnosed mental illness.

“The [previous] findings are quite contradictory and there’s not a clear outcome in terms of intervention results, so we pooled the data and ran the meta-analysis, thinking it would be a great way to add some important evidence to the science,” she added.

To allow for a more comprehensive assessment of yoga’s potential mental health benefits, the investigators included a range of mental health diagnoses.

Dose-dependent effect

Studies were only included in the analysis if they were randomized, controlled trials with a yoga intervention that had a minimum of 50% physical activity during each session in adults with a recognized diagnosed mental disorder. Control conditions were defined as treatment as usual, wait list, or attention controls.

Two investigators independently scanned article titles and abstracts, and a final list of articles for the study was decided by consensus. Study quality was reported using the PEDro checklist; a random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software.

A total of 3,880 records were identified and screened. The investigators assessed full-text versions of 80 articles, 19 of which (1,080 patients) were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Of these, nine studies included patients with a depressive disorder; five trials were in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, three studies included patients with a diagnosis of PTSD, one study included patients diagnosed with alcohol dependence, and one study included patients with a range of psychiatric disorders.

Of the 1,080 patients included in the review, 578 were assigned to yoga and 502 to control conditions. Yoga practice involved a mixture of movement, breathing exercises, and/or mindfulness, but the movement component took up more than half of each session.

The yoga interventions lasted an average of 2.4 months (range, 1.5-2.5 months), with an average of 1.6 sessions per week (range, 1-3 sessions) that lasted an average of 60 minutes (range, 20-90 minutes).

Of the 19 studies (632 patients), 13 reported changes in depressive symptoms and were therefore included in the meta-analysis. The six studies excluded from the quantitative analysis did not report depression symptom scores.

With respect to primary outcomes, individuals who performed yoga showed a greater reduction in depressive symptoms, compared with the three control groups (standardized mean difference, –0.41; 95% CI, –0.65 to –0.17; P < .001).

Specific subgroup analyses showed a moderate effect of yoga on depressive symptoms, compared with wait-list controls (SMD, –0.58; P < .05), treatment as usual (SMD, –0.39; P = .31), and attention controls (SMD, –0.21; P = .22).

Subgroup analyses were also performed with respect to diagnostic category. These data showed a moderate effect of yoga on depressive symptoms in depressive disorders (SMD, –0.40; P < .01), no effect in PTSD (SMD, –0.01; P = .95), a nominal effect in alcohol use disorders (SMD, –0.24; P = .69), and a marked effect in schizophrenia (SMD, –0.90; P < .01).

Movement may be key

Researchers also performed a series of meta-regression analyses, which showed that the number of yoga sessions performed each week had a significant effect on depressive symptoms. Indeed, individuals with higher session frequencies demonstrated a greater improvement in symptoms (beta, –0.44; P < .001).

These findings, said Ms. Brinsley, suggest yoga may be a viable intervention for managing depressive symptoms in patients with a variety of mental disorders.

Based on these findings, along with other conventional forms of exercise.

Equally important was the finding that the number of weekly yoga sessions moderated the effect of depressive symptoms, as it may inform the future design of yoga interventions in patients with mental disorders.

With this in mind, the researchers recommended that such interventions should aim to increase the frequency or weekly sessions rather than the duration of each individual session or the overall duration of the intervention.

However, said Ms. Brinsley, these findings suggest it is the physical aspect of the yoga practice that may be key.

“Yoga comprises several different components, including the movement postures, the breathing component, and the mindfulness or meditative component, but in this meta-analysis we looked specifically at yoga that was at least 50% movement based. So it might have also included mindfulness and breathing, but it had to have the movement,” she said.

Don’t discount meditation

Commenting on the findings, Holger Cramer, MSc, PhD, DSc, who was not involved in the study, noted that the systematic review and meta-analysis builds on a number of previous reviews regarding the benefits of yoga for mental disorders.

“Surprisingly, the largest effect in this analysis was found in schizophrenia, even higher than in patients with depressive disorders,” said Dr. Cramer of the University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany). “This is in strong contradiction to what would otherwise be expected. As the authors point out, only about a quarter of all schizophrenia patients suffer from depression, so there should not be so much room for improvement.”

Dr. Cramer also advised against reducing yoga to simply a physical undertaking. “We have shown in our meta-analysis that those interventions focusing on meditation and/or breathing techniques are the most effective ones,” he added.

As such, he urged that breathing techniques be a part of yoga for treating depression in psychiatric disorders, though care should be taken in patients with PTSD, “since breath control might be perceived as unpleasant.”

For Ms. Brinsley, the findings help solidify yoga’s potential as a genuine treatment option for a variety of mental health patients suffering depressive symptoms.

“It’s about acknowledging that yoga can be a helpful part of treatment and can have a significant effect on mental health,” she noted.

At the same time, practitioners also need to acknowledge that patients suffering from mental health disorders may struggle with motivation when it comes to activities such as yoga.

“Engaging in a new activity can be particularly challenging if you’re struggling with mental health. Nevertheless, it’s important for people to have a choice and do something they enjoy. And yoga can be another tool in their toolbox for managing their mental health,” she said.

The study was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and Health Education England. Ms. Brinsley and Dr. Cramer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cannabidiol for psychosis: A review of 4 studies

There has been increasing interest in the medicinal use of cannabidiol (CBD) for a wide variety of health conditions. CBD is one of more than 80 chemicals identified in the Cannabis sativa plant, otherwise known as marijuana or hemp. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the psychoactive ingredient found in marijuana that produces a “high.” CBD, which is one of the most abundant cannabinoids in Cannabis sativa, does not produce any psychotomimetic effects.

The strongest scientific evidence supporting CBD for medicinal purposes is for its effectiveness in treating certain childhood epilepsy syndromes that typically do not respond to antiseizure medications. Currently, the only FDA-approved CBD product is a prescription oil cannabidiol (brand name: Epidiolex) for treating 2 types of epilepsy. Aside from Epidiolex, state laws governing the use of CBD vary. CBD is being studied as a treatment for a wide range of psychiatric conditions, including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dystonia, insomnia, and anxiety. Research supporting CBD’s benefits is limited, and the US National Library of Medicine’s MedlinePlus indicates there is “insufficient evidence to rate effectiveness” for these indications.1

Despite having been legalized for medicinal use in many states, CBD is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance by the US Drug Enforcement Agency. Because of this classification, little has been done to regulate and oversee the sale of products containing CBD. In a 2017 study of 84 CBD products sold by 31 companies online, Bonn-Miller et al2 found that nearly 70% percent of products were inaccurately labeled. In this study, blind testing found that only approximately 31% of products contained within 10% of the amount of CBD that was listed on the label. These researchers also found that some products contained components not listed on the label, including THC.2

The relationship between cannabis and psychosis or psychotic symptoms has been investigated for decades. Some recent studies that examined the effects of CBD on psychosis found that individuals who use CBD may experience fewer positive psychotic symptoms compared with placebo. This raises the question of whether CBD may have a role in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. One of the first studies on this issue was conducted by Leweke et al,3 who compared oral CBD, up to 800 mg/d, with the antipsychotic amisulpride, up to 800 mg/d, in 39 patients with an acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms. Amisulpride is used outside the United States to treat psychosis, but is FDA-approved only as an antiemetic. Patients were treated for 4 weeks. By Day 28, there was a significant reduction in positive symptoms as measured using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), with no significant difference in efficacy between the treatments. Similar findings emerged for negative, total, and general symptoms, with significant reductions by Day 28 in both treatment arms, and no significant between-treatment differences.

These findings were the first robust indication that CBD may have antipsychotic efficacy. However, of greater interest may be CBD’s markedly superior adverse effect profile. Predictably, amisulpride significantly increased extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, and prolactin levels from baseline to Day 28. However, no significant change was found in any of these adverse effects in the CBD group, and the between-treatment difference was significant (all P < .01).

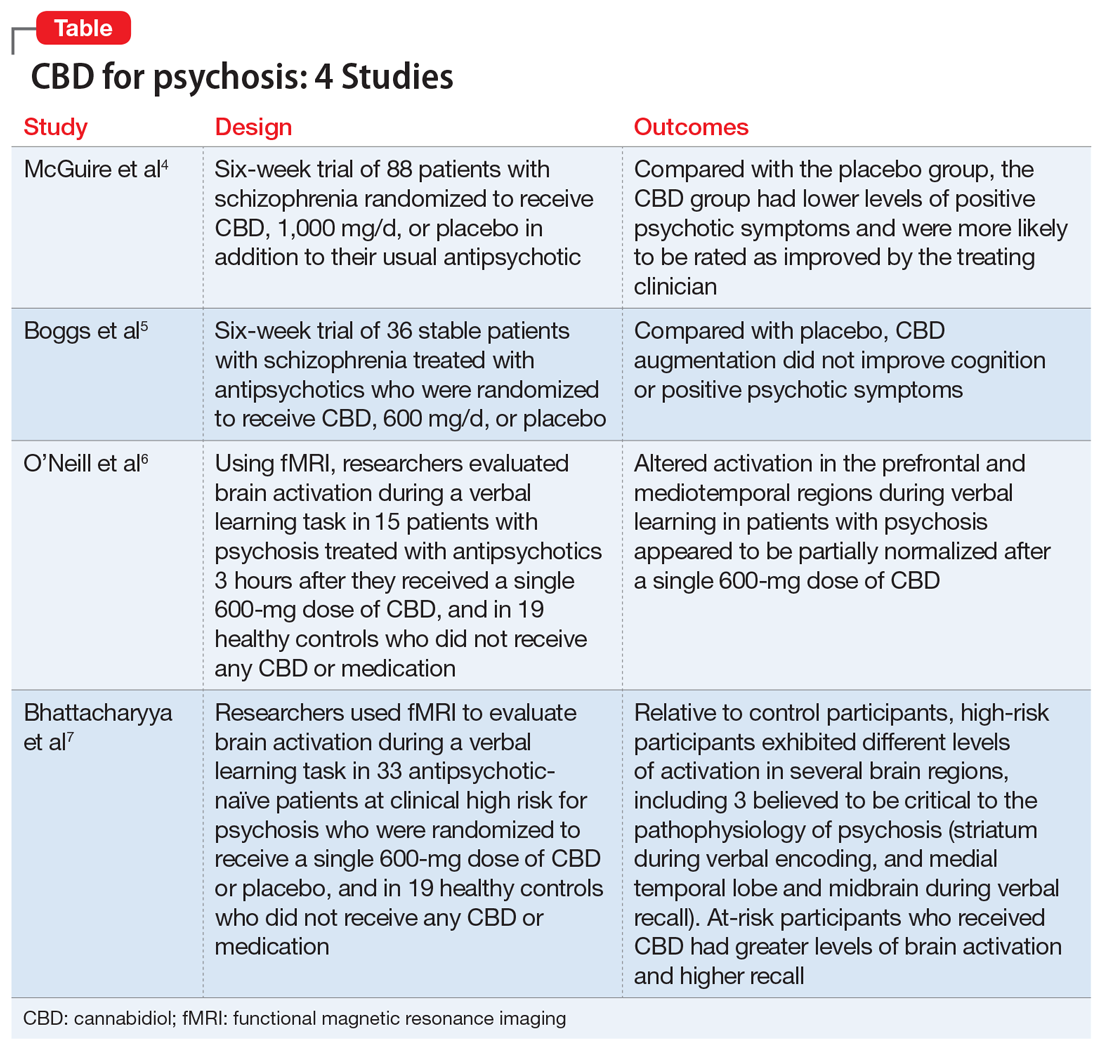

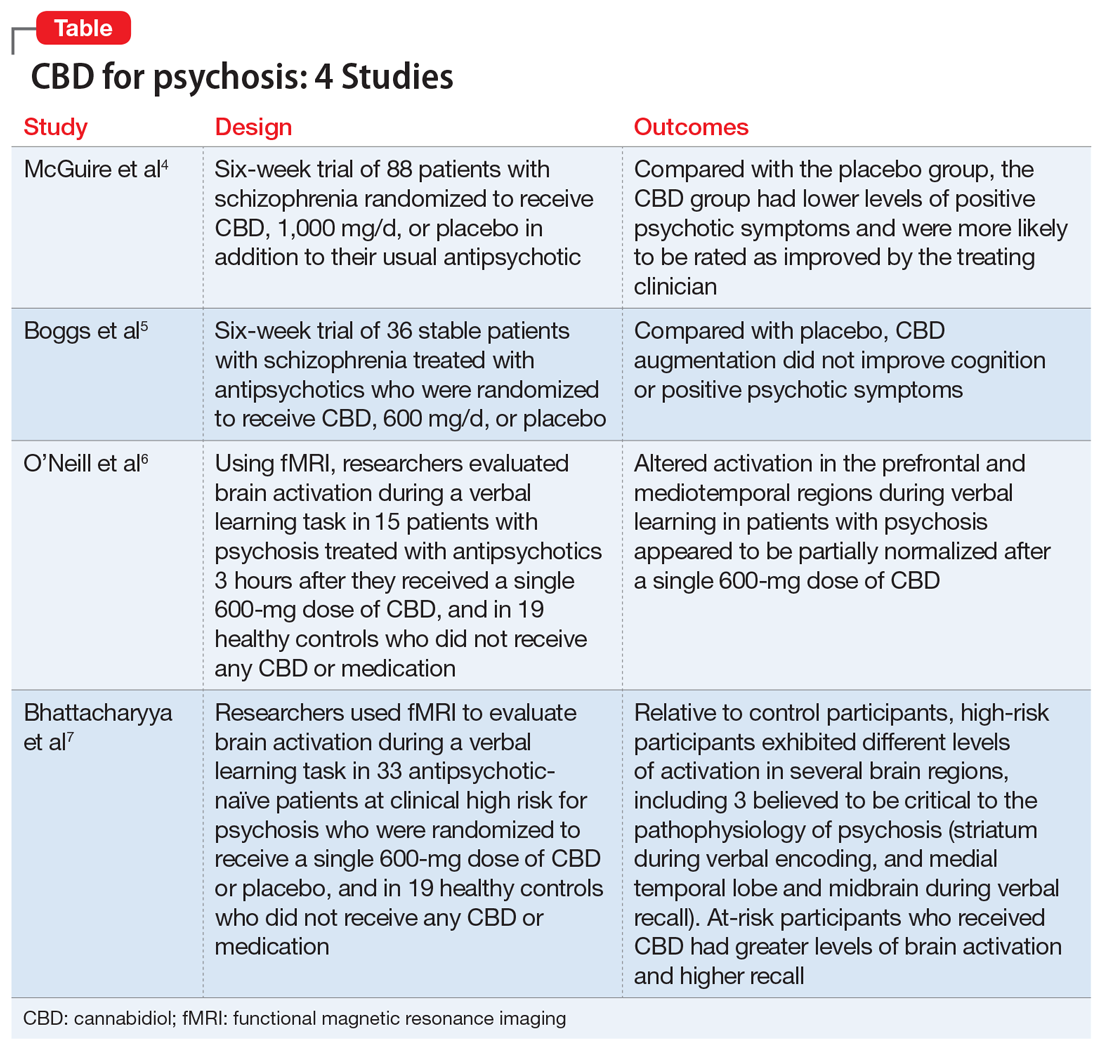

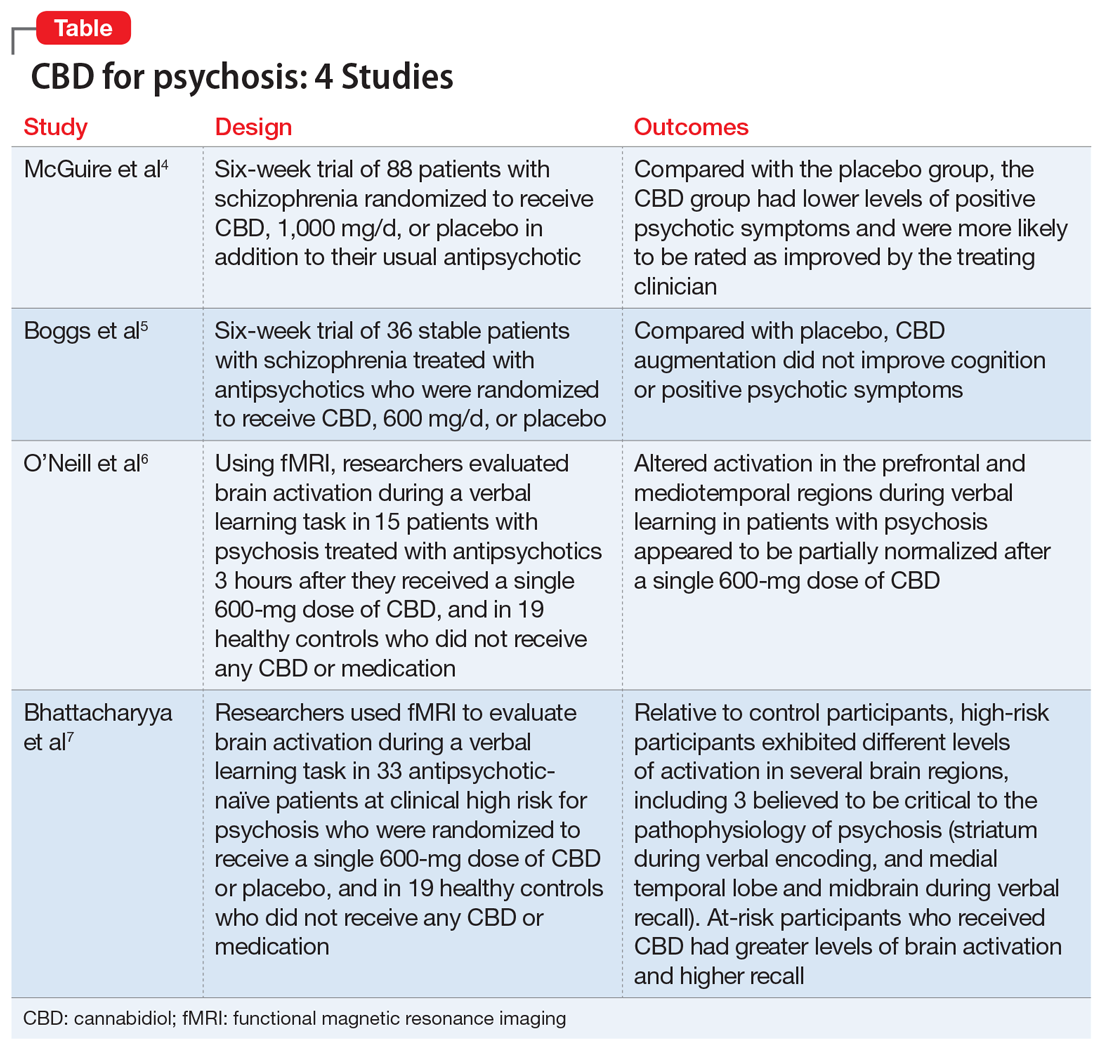

Here we review 4 recent studies that evaluated CBD as a treatment for schizophrenia. These studies are summarized in the Table.4-7

Continue to: McGuire P, et al...

1. McGuire P, Robson P, Cubala WJ, et al. Cannabidiol (CBD) as an adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(3):225-231.

Antipsychotic medications act through blockade of central dopamine D2 receptors. For most patients, antipsychotics effectively treat positive psychotic symptoms, which are driven by elevated dopamine function. However, these medications have minimal effects on negative symptoms and cognitive impairment, features of schizophrenia that are not driven by elevated dopamine. Compounds exhibiting a mechanism of action unlike that of current antipsychotics may improve the treatment and outcomes of patients with schizophrenia. The mechanism of action of CBD is unclear, but it does not appear to involve the direct antagonism of dopamine receptors. Human and animal research study findings indicate that CBD has antipsychotic properties. McGuire et al4 assessed the safety and effectiveness of CBD as an adjunctive treatment of schizophrenia.

Study design

- In this double-blind parallel-group trial conducted at 15 hospitals in the United Kingdom, Romania, and Poland, 88 patients with schizophrenia received CBD (1,000 mg/d; N = 43) or placebo (N = 45) as adjunct to the antipsychotic medication they had been prescribed. Patients had previously demonstrated at least a partial response to antipsychotic treatment, and were taking stable doses of an antipsychotic for ≥4 weeks.

- Evaluations of symptoms, general functioning, cognitive performance, and EPS were completed at baseline and on Days 8, 22, and 43 (± 3 days). Current substance use was assessed using a semi-structured interview, and reassessed at the end of treatment.

- The key endpoints were the patients’ level of functioning, severity of symptoms, and cognitive performance. Participants were assessed before and after treatment using the PANSS, the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS), the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF), and the improvement and severity scales of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI-I and CGI-S, respectively).

- The clinicians’ impression of illness severity and symptom improvement and patient- or caregiver-reported impressions of general functioning and sleep also were noted.

Outcomes

- After 6 weeks, compared with the placebo group, the CBD group had lower levels of positive psychotic symptoms and were more likely to be rated as improved and as not severely unwell by the treating clinician. Patients in the CBD group also showed greater improvements in cognitive performance and in overall functioning, although these were not statistically significant.

- Similar levels of negative psychotic symptoms, overall psychopathology, and general psychopathology were observed in the CBD and placebo groups. The CBD group had a higher proportion of treatment responders (≥20% improvement in PANSS total score) than did the placebo group; however, the total number of responders per group was small (12 and 6 patients, respectively). At baseline, most patients in both groups were classified as moderately, markedly, or severely ill (83.4% in the CBD group vs 79.6% in placebo group). By the end of treatment, this decreased to 54.8% in the CBD group and 63.6% in the placebo group. Clinicians rated 78.6% of patients in the CBD group as “improved” on the CGI-I, compared with 54.6% of patients in the placebo group.

Conclusion

- CBD treatment adjunctive to antipsychotics was associated with significant effects on positive psychotic symptoms and on CGI-I and illness severity. Improvements in cognitive performance and level of overall functioning were also seen, but were not statistically significant.

- Although the effect on positive symptoms was modest, improvement occurred in patients being treated with appropriate dosages of antipsychotics, which suggests CBD provided benefits over and above the effect of antipsychotic treatment. Moreover, the changes in CGI-I and CGI-S scores indicated that the improvement was evident to the treating psychiatrists, and may therefore be clinically meaningful.

Continue to: Boggs DL, et al...

2. Boggs DL, Surti T, Gupta A, et al. The effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on cognition and symptoms in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia a randomized placebo controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(7):1923-1932.

Schizophrenia is associated with cognitive deficits in learning, recall, attention, working memory, and executive function. The cognitive impairments associated with schizophrenia (CIAS) are independent of phase of illness and often persist after other symptoms have been effectively treated. These impairments are the strongest predictor of functional outcome, even more so than psychotic symptoms.

Antipsychotics have limited efficacy for CIAS, which highlights the need for CIAS treatments that target other nondopaminergic neurotransmitter systems. The endocannabinoid system, which has been implicated in schizophrenia and in cognition, is a potential target. Several cannabinoids impair memory and attention. The main psychoactive component of marijuana, THC, is a cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) partial agonist. Administration of THC produces significant deficits in verbal learning, attention, and working memory.

Researchers have hypothesized that CB1R blockade or modulation of cannabinoid levels may offer a novel target for treating CIAS. Boggs et al5 compared the cognitive, symptomatic, and adverse effects of CBD vs placebo.

Study design

- In this 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted in Connecticut from September 2009 to May 2012, 36 stable patients with schizophrenia who were treated with antipsychotics were randomized to also receive oral CBD, 600 mg/d, or placebo.

- Cognition was assessed using the t score of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) composite and subscales at baseline and the end of study. An increase in MCCB t score indicates an improvement in cognitive ability. Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the PANSS at baseline, Week 2, Week 4, and Week 6.

Outcomes

- CBD augmentation did not improve MCCB performance or psychotic symptoms. There was no main effect of time or medication on MCCB composite score, but a significant drug × time effect was observed.

- Post-hoc analyses revealed that only patients who received placebo improved over time. The lack of a similar improvement with CBD might be related to the greater incidence of sedation among the CBD group (20%) vs the placebo group (5%). Both the MCCB composite score and reasoning and problem-solving domain scores were higher at baseline and endpoint for patients who received CBD, which suggests that the observed improvement in the placebo group could represent a regression to the mean.

- There was a significant decrease in PANSS scores over time, but there was no significant drug × time interaction.

Conclusion

- CBD augmentation was not associated with an improvement in MCCB score. This is consistent with data from other clinical trials4,8 that suggested that CBD (at a wide range of doses) does not have significant beneficial effects on cognition in patients with schizophrenia.

- Additionally, CBD did not improve psychotic symptoms. These results are in contrast to published case reports9,10 and 2 published clinical trials3,4 that found CBD (800 mg/d) was as efficacious as amisulpride in reducing positive psychotic symptoms, and a small but statistically significant improvement in PANSS positive scores with CBD (1,000 mg/d) compared with placebo. However, these results are similar to those of a separate study11 that evaluated the same 600-mg/d dose of CBD used by Boggs et al.5 At 600 mg/d, CBD produced very small improvements in PANSS total scores (~2.4) that were not statistically significant. A higher CBD dose may be needed to reduce psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Continue to: O’Neill A, et al...

3. O’Neill A, Wilson R, Blest-Hopley G, et al. Normalization of mediotemporal and prefrontal activity, and mediotemporal-striatal connectivity, may underlie antipsychotic effects of cannabidiol in psychosis. Psychol Med. 2020;1-11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003519.

In addition to their key roles in the psychopathology of psychosis, the mediotemporal and prefrontal cortices are involved in learning and memory, and the striatum plays a role in encoding contextual information associated with memories. Because deficits in verbal learning and memory are one of the most commonly reported impairments in patients with psychosis, O’Neill et al6 used functional MRI (fMRI) to examine brain activity during a verbal learning task in patients with psychosis after taking CBD or placebo.

Study design

- In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study, researchers investigated the effects of a single dose of CBD in 15 patients with psychosis who were treated with antipsychotics. Three hours after taking a 600-mg dose of CBD or placebo, these participants were scanned using fMRI while performing a verbal paired associate (VPA) learning task. Nineteen healthy controls underwent fMRI in identical conditions, but without any medication administration.

- The fMRI measured brain activation using the blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) hemodynamic responses of the brain. The fMRI signals were studied in the mediotemporal, prefrontal, and striatal regions.

- The VPA task presented word pairs visually, and the accuracy of responses were recorded online. The VPA task was comprised of 3 conditions: encoding, recall, and baseline.

- Results during each phase of the VPA task were compared.

Outcomes

- While completing the VPA task after taking placebo, compared with healthy controls, patients with psychosis demonstrated a different pattern of activity in the prefrontal and mediotemporal brain areas. Specifically, during verbal encoding, the placebo group showed altered activation in prefrontal regions. During verbal recall, the placebo group showed altered activation in prefrontal and mediotemporal regions, as well as increased mediotemporal-striatal functional connectivity.

- After participants received CBD, activation in these brain areas became more like the activation seen in controls. CBD attenuated dysfunction in these regions such that activation was intermediate between the placebo condition and the control group. CBD also attenuated functional connectivity between the hippocampus and striatum, and lead to reduced symptoms in patients with psychosis (as measured by PANSS total score).

Conclusion

- Altered activation in prefrontal and mediotemporal regions during verbal learning in patients with psychosis appeared to be partially normalized after a single 600-mg dose of CBD. Results also showed improvement in PANSS total score with CBD.

- These findings suggest that a single dose of CBD may partially attenuate the dysfunctional prefrontal and mediotemporal activation that is believed to underlie the dopamine dysfunction that leads to psychotic symptoms. These effects, along with a reduction in psychotic symptoms, suggest that normalization of altered prefrontal and mediotemporal function and mediotemporal-striatal connectivity may underlie the antipsychotic effects of CBD in established psychosis.

Continue to: Bhattacharyya S, et al...