User login

How physicians can provide better care to transgender patients

People who identify as transgender experience many health disparities, in addition to lack of access to quality care. The most commonly cited barrier is the lack of providers who are knowledgeable about transgender health care, according to past surveys.

Even those who do seek care often have unpleasant experiences. A 2015 survey conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality found that 33% of those who saw a health care provider reported at least one unfavorable experience related to being transgender, such as being verbally harassed or refused treatment because of their gender identity. In fact, 23% of those surveyed say they did not seek health care they needed in the past year because of fear of being mistreated as a transgender person.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: Surveys have shown that many people who identify as transgender will seek only transition care, not primary or preventive care. Why is that?

Dr. Brandt: My answer is multifactorial. Transgender patients do seek primary care – just not as readily. There’s a lot of misconceptions about health care needs for the LGBT community in general. For example, lesbian or bisexual women may be not as well informed about the need for Pap smears compared with their heterosexual counterparts. These misconceptions are further exacerbated in the transgender community.

The fact that a lot of patients seek only transition-related care, but not preventive services, such as primary care and gynecologic care, is also related to fears of discrimination and lack of education of providers. These patients are afraid when they walk into an office that they will be misgendered or their physician won’t be familiar with their health care needs.

What can clinics and clinicians do to create a safe and welcoming environment?

Dr. Brandt: It starts with educating office staff about terminology and gender identities.

A key feature of our EHR is the sexual orientation and gender identity platform, which asks questions about a patient’s gender identity, sexual orientation, sex assigned at birth, and organ inventory. These data are then found in the patient information tab and are just as relevant as their insurance status, age, and date of birth.

There are many ways a doctor’s office can signal to patients that they are inclusive. They can hang LGBTQ-friendly flags or symbols or a sign saying, “We have an anti-discrimination policy” in the waiting room. A welcoming environment can also be achieved by revising patient questionnaires or forms so that they aren’t gender-specific or binary.

Given that the patient may have limited contact with a primary care clinician, how do you prioritize what you address during the visit?

Dr. Brandt: Similar to cisgender patients, it depends initially on the age of the patient and the reason for the visit. The priorities of an otherwise healthy transgender patient in their 20s are going to be largely the same as for a cisgender patient of the same age. As patients age in the primary care world, you’re addressing more issues, such as colorectal screening, lipid disorders, and mammograms, and that doesn’t change. For the most part, the problems that you address should be specific for that age group.

It becomes more complicated when you add in factors such as hormone therapy and whether patients have had any type of gender-affirming surgery. Those things can change the usual recommendations for screening or risk assessment. We try to figure out what routine health maintenance and cancer screening a patient needs based on age and risk factors, in addition to hormone status and surgical state.

Do you think that many physicians are educated about the care of underserved populations such as transgender patients?

Dr. Brandt: Yes and no. We are definitely getting better at it. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a committee opinion highlighting transgender care. So organizations are starting to prioritize these populations and recognize that they are, in fact, underserved and they have special health care needs.

However, the knowledge gaps are still pretty big. I get calls daily from providers asking questions about how to manage patients on hormones, or how to examine a patient who has undergone a vaginoplasty. I hear a lot of horror stories from transgender patients who had their hormones stopped for absurd and medically misinformed reasons.

But I definitely think it’s getting better and it’s being addressed at all levels – the medical school level, the residency level, and the attending level. It just takes time to inform people and for people to get used to the health care needs of these patients.

What should physicians keep in mind when treating patients who identify as transgender?

Dr. Brandt: First and foremost, understanding the terminology and the difference between gender identity, sex, and sexual orientation. Being familiar with that language and being able to speak that language very comfortably and not being awkward about it is a really important thing for primary care physicians and indeed any physician who treats transgender patients.

Physicians should also be aware that any underserved population has higher rates of mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. Obviously, that goes along with being underserved and the stigma and the disparities that exist for these patients. Having providers educate themselves about what those disparities are and how they impact a patient’s daily life and health is paramount to knowing how to treat patients.

What are your top health concerns for these patients and how do you address them?

Dr. Brandt: I think mental health and safety is probably the number one for me. About 41% of transgender adults have attempted suicide. That number is roughly 51% in transgender youth. That is an astonishing number. These patients have much higher rates of domestic violence, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault, especially trans women and trans women of color. So understanding those statistics is huge.

Obesity, smoking, and substance abuse are my next three. Again, those are things that should be addressed at any visit, regardless of the gender identity or sexual orientation of the patient, but those rates are particularly high in this population.

Fertility and long-term care for patients should be addressed. Many patients who identify as transgender are told they can’t have a family. As a primary care physician, you may see a patient before they are seen by an ob.gyn. or surgeon. Talking about what a patient’s long-term life goals are with fertility and family planning, and what that looks like for them, is a big thing for me. Other providers may not feel that’s a concern, but I believe it should be discussed before initiation of hormone therapy, which can significantly impact fertility in some patients.

Are there nuances to the physical examination that primary care physicians should be aware of when dealing with transmasculine patients vs. transfeminine patients?

Dr. Brandt: Absolutely. And this interview can’t cover the scope of those nuances. An example that comes to mind is the genital exam. For transgender women who have undergone a vaginoplasty, the pelvic exam can be very affirming. Whereas for transgender men, a gynecologic exam can significantly exacerbate dysphoria and there are ways to conduct the exam to limit this discomfort and avoid creating a traumatic experience for the patient. It’s important to be aware that the genital exam, or any type of genitourinary exam, can be either affirming or not affirming.

Sexually transmitted infections are up in the general population, and the trans population is at even higher risk. What should physicians think about when they assess this risk?

Dr. Brandt: It’s really important for primary care clinicians and for gynecologists to learn to be comfortable talking about sexual practices, because what people do behind closed doors is really a key to how to counsel patients about safe sex.

People are well aware of the need to have safe sex. However, depending on the type of sex that you’re having, what body parts go where, what is truly safe can vary and people may not know, for example, to wear a condom when sex toys are involved or that a transgender male on testosterone can become pregnant during penile-vaginal intercourse. Providers really should be very educated on the array of sexual practices that people have and how to counsel them about those. They should know how to ask patients the gender identity of their sexual partners, the sexual orientation of their partners, and what parts go where during sex.

Providers should also talk to patients about PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis], whether they identify as cisgender or transgender. My trans patients tend to be a lot more educated about PrEP than other patients. It’s something that many of the residents, even in a standard gynecologic clinic, for example, don’t talk to cisgender patients about because of the stigma surrounding HIV. Many providers still think that the only people who are at risk for HIV are men who have sex with men. And while those rates are higher in some populations, depending on sexual practices, those aren’t the only patients who qualify for PrEP.

Overall, in order to counsel patients about STIs and safe sexual practices, providers should learn to be comfortable talking about sex.

Do you have any strategies on how to make the appointment more successful in addressing those issues?

Dr. Brandt: Bedside manner is a hard thing to teach, and comfort in talking about sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation can vary – but there are a lot of continuing medical education courses that physicians can utilize through the World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

If providers start to notice an influx of patients who identify as transgender or if they want to start seeing transgender patients, it’s really important for them to have that training before they start interacting with patients. In all of medicine, we sort of learn as we go, but this patient population has been subjected to discrimination, violence, error, and misgendering. They have dealt with providers who didn’t understand their health care needs. While this field is evolving, knowing how to appropriately address a patient (using their correct name, pronouns, etc.) is an absolute must.

That needs to be part of a provider’s routine vernacular and not something that they sort of stumble through. You can scare a patient away as soon as they walk into the office with an uneducated front desk staff and things that are seen in the office. Seeking out those educational tools, being aware of your own deficits as a provider and the educational needs of your office, and addressing those needs is really key.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who identify as transgender experience many health disparities, in addition to lack of access to quality care. The most commonly cited barrier is the lack of providers who are knowledgeable about transgender health care, according to past surveys.

Even those who do seek care often have unpleasant experiences. A 2015 survey conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality found that 33% of those who saw a health care provider reported at least one unfavorable experience related to being transgender, such as being verbally harassed or refused treatment because of their gender identity. In fact, 23% of those surveyed say they did not seek health care they needed in the past year because of fear of being mistreated as a transgender person.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: Surveys have shown that many people who identify as transgender will seek only transition care, not primary or preventive care. Why is that?

Dr. Brandt: My answer is multifactorial. Transgender patients do seek primary care – just not as readily. There’s a lot of misconceptions about health care needs for the LGBT community in general. For example, lesbian or bisexual women may be not as well informed about the need for Pap smears compared with their heterosexual counterparts. These misconceptions are further exacerbated in the transgender community.

The fact that a lot of patients seek only transition-related care, but not preventive services, such as primary care and gynecologic care, is also related to fears of discrimination and lack of education of providers. These patients are afraid when they walk into an office that they will be misgendered or their physician won’t be familiar with their health care needs.

What can clinics and clinicians do to create a safe and welcoming environment?

Dr. Brandt: It starts with educating office staff about terminology and gender identities.

A key feature of our EHR is the sexual orientation and gender identity platform, which asks questions about a patient’s gender identity, sexual orientation, sex assigned at birth, and organ inventory. These data are then found in the patient information tab and are just as relevant as their insurance status, age, and date of birth.

There are many ways a doctor’s office can signal to patients that they are inclusive. They can hang LGBTQ-friendly flags or symbols or a sign saying, “We have an anti-discrimination policy” in the waiting room. A welcoming environment can also be achieved by revising patient questionnaires or forms so that they aren’t gender-specific or binary.

Given that the patient may have limited contact with a primary care clinician, how do you prioritize what you address during the visit?

Dr. Brandt: Similar to cisgender patients, it depends initially on the age of the patient and the reason for the visit. The priorities of an otherwise healthy transgender patient in their 20s are going to be largely the same as for a cisgender patient of the same age. As patients age in the primary care world, you’re addressing more issues, such as colorectal screening, lipid disorders, and mammograms, and that doesn’t change. For the most part, the problems that you address should be specific for that age group.

It becomes more complicated when you add in factors such as hormone therapy and whether patients have had any type of gender-affirming surgery. Those things can change the usual recommendations for screening or risk assessment. We try to figure out what routine health maintenance and cancer screening a patient needs based on age and risk factors, in addition to hormone status and surgical state.

Do you think that many physicians are educated about the care of underserved populations such as transgender patients?

Dr. Brandt: Yes and no. We are definitely getting better at it. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a committee opinion highlighting transgender care. So organizations are starting to prioritize these populations and recognize that they are, in fact, underserved and they have special health care needs.

However, the knowledge gaps are still pretty big. I get calls daily from providers asking questions about how to manage patients on hormones, or how to examine a patient who has undergone a vaginoplasty. I hear a lot of horror stories from transgender patients who had their hormones stopped for absurd and medically misinformed reasons.

But I definitely think it’s getting better and it’s being addressed at all levels – the medical school level, the residency level, and the attending level. It just takes time to inform people and for people to get used to the health care needs of these patients.

What should physicians keep in mind when treating patients who identify as transgender?

Dr. Brandt: First and foremost, understanding the terminology and the difference between gender identity, sex, and sexual orientation. Being familiar with that language and being able to speak that language very comfortably and not being awkward about it is a really important thing for primary care physicians and indeed any physician who treats transgender patients.

Physicians should also be aware that any underserved population has higher rates of mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. Obviously, that goes along with being underserved and the stigma and the disparities that exist for these patients. Having providers educate themselves about what those disparities are and how they impact a patient’s daily life and health is paramount to knowing how to treat patients.

What are your top health concerns for these patients and how do you address them?

Dr. Brandt: I think mental health and safety is probably the number one for me. About 41% of transgender adults have attempted suicide. That number is roughly 51% in transgender youth. That is an astonishing number. These patients have much higher rates of domestic violence, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault, especially trans women and trans women of color. So understanding those statistics is huge.

Obesity, smoking, and substance abuse are my next three. Again, those are things that should be addressed at any visit, regardless of the gender identity or sexual orientation of the patient, but those rates are particularly high in this population.

Fertility and long-term care for patients should be addressed. Many patients who identify as transgender are told they can’t have a family. As a primary care physician, you may see a patient before they are seen by an ob.gyn. or surgeon. Talking about what a patient’s long-term life goals are with fertility and family planning, and what that looks like for them, is a big thing for me. Other providers may not feel that’s a concern, but I believe it should be discussed before initiation of hormone therapy, which can significantly impact fertility in some patients.

Are there nuances to the physical examination that primary care physicians should be aware of when dealing with transmasculine patients vs. transfeminine patients?

Dr. Brandt: Absolutely. And this interview can’t cover the scope of those nuances. An example that comes to mind is the genital exam. For transgender women who have undergone a vaginoplasty, the pelvic exam can be very affirming. Whereas for transgender men, a gynecologic exam can significantly exacerbate dysphoria and there are ways to conduct the exam to limit this discomfort and avoid creating a traumatic experience for the patient. It’s important to be aware that the genital exam, or any type of genitourinary exam, can be either affirming or not affirming.

Sexually transmitted infections are up in the general population, and the trans population is at even higher risk. What should physicians think about when they assess this risk?

Dr. Brandt: It’s really important for primary care clinicians and for gynecologists to learn to be comfortable talking about sexual practices, because what people do behind closed doors is really a key to how to counsel patients about safe sex.

People are well aware of the need to have safe sex. However, depending on the type of sex that you’re having, what body parts go where, what is truly safe can vary and people may not know, for example, to wear a condom when sex toys are involved or that a transgender male on testosterone can become pregnant during penile-vaginal intercourse. Providers really should be very educated on the array of sexual practices that people have and how to counsel them about those. They should know how to ask patients the gender identity of their sexual partners, the sexual orientation of their partners, and what parts go where during sex.

Providers should also talk to patients about PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis], whether they identify as cisgender or transgender. My trans patients tend to be a lot more educated about PrEP than other patients. It’s something that many of the residents, even in a standard gynecologic clinic, for example, don’t talk to cisgender patients about because of the stigma surrounding HIV. Many providers still think that the only people who are at risk for HIV are men who have sex with men. And while those rates are higher in some populations, depending on sexual practices, those aren’t the only patients who qualify for PrEP.

Overall, in order to counsel patients about STIs and safe sexual practices, providers should learn to be comfortable talking about sex.

Do you have any strategies on how to make the appointment more successful in addressing those issues?

Dr. Brandt: Bedside manner is a hard thing to teach, and comfort in talking about sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation can vary – but there are a lot of continuing medical education courses that physicians can utilize through the World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

If providers start to notice an influx of patients who identify as transgender or if they want to start seeing transgender patients, it’s really important for them to have that training before they start interacting with patients. In all of medicine, we sort of learn as we go, but this patient population has been subjected to discrimination, violence, error, and misgendering. They have dealt with providers who didn’t understand their health care needs. While this field is evolving, knowing how to appropriately address a patient (using their correct name, pronouns, etc.) is an absolute must.

That needs to be part of a provider’s routine vernacular and not something that they sort of stumble through. You can scare a patient away as soon as they walk into the office with an uneducated front desk staff and things that are seen in the office. Seeking out those educational tools, being aware of your own deficits as a provider and the educational needs of your office, and addressing those needs is really key.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who identify as transgender experience many health disparities, in addition to lack of access to quality care. The most commonly cited barrier is the lack of providers who are knowledgeable about transgender health care, according to past surveys.

Even those who do seek care often have unpleasant experiences. A 2015 survey conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality found that 33% of those who saw a health care provider reported at least one unfavorable experience related to being transgender, such as being verbally harassed or refused treatment because of their gender identity. In fact, 23% of those surveyed say they did not seek health care they needed in the past year because of fear of being mistreated as a transgender person.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: Surveys have shown that many people who identify as transgender will seek only transition care, not primary or preventive care. Why is that?

Dr. Brandt: My answer is multifactorial. Transgender patients do seek primary care – just not as readily. There’s a lot of misconceptions about health care needs for the LGBT community in general. For example, lesbian or bisexual women may be not as well informed about the need for Pap smears compared with their heterosexual counterparts. These misconceptions are further exacerbated in the transgender community.

The fact that a lot of patients seek only transition-related care, but not preventive services, such as primary care and gynecologic care, is also related to fears of discrimination and lack of education of providers. These patients are afraid when they walk into an office that they will be misgendered or their physician won’t be familiar with their health care needs.

What can clinics and clinicians do to create a safe and welcoming environment?

Dr. Brandt: It starts with educating office staff about terminology and gender identities.

A key feature of our EHR is the sexual orientation and gender identity platform, which asks questions about a patient’s gender identity, sexual orientation, sex assigned at birth, and organ inventory. These data are then found in the patient information tab and are just as relevant as their insurance status, age, and date of birth.

There are many ways a doctor’s office can signal to patients that they are inclusive. They can hang LGBTQ-friendly flags or symbols or a sign saying, “We have an anti-discrimination policy” in the waiting room. A welcoming environment can also be achieved by revising patient questionnaires or forms so that they aren’t gender-specific or binary.

Given that the patient may have limited contact with a primary care clinician, how do you prioritize what you address during the visit?

Dr. Brandt: Similar to cisgender patients, it depends initially on the age of the patient and the reason for the visit. The priorities of an otherwise healthy transgender patient in their 20s are going to be largely the same as for a cisgender patient of the same age. As patients age in the primary care world, you’re addressing more issues, such as colorectal screening, lipid disorders, and mammograms, and that doesn’t change. For the most part, the problems that you address should be specific for that age group.

It becomes more complicated when you add in factors such as hormone therapy and whether patients have had any type of gender-affirming surgery. Those things can change the usual recommendations for screening or risk assessment. We try to figure out what routine health maintenance and cancer screening a patient needs based on age and risk factors, in addition to hormone status and surgical state.

Do you think that many physicians are educated about the care of underserved populations such as transgender patients?

Dr. Brandt: Yes and no. We are definitely getting better at it. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a committee opinion highlighting transgender care. So organizations are starting to prioritize these populations and recognize that they are, in fact, underserved and they have special health care needs.

However, the knowledge gaps are still pretty big. I get calls daily from providers asking questions about how to manage patients on hormones, or how to examine a patient who has undergone a vaginoplasty. I hear a lot of horror stories from transgender patients who had their hormones stopped for absurd and medically misinformed reasons.

But I definitely think it’s getting better and it’s being addressed at all levels – the medical school level, the residency level, and the attending level. It just takes time to inform people and for people to get used to the health care needs of these patients.

What should physicians keep in mind when treating patients who identify as transgender?

Dr. Brandt: First and foremost, understanding the terminology and the difference between gender identity, sex, and sexual orientation. Being familiar with that language and being able to speak that language very comfortably and not being awkward about it is a really important thing for primary care physicians and indeed any physician who treats transgender patients.

Physicians should also be aware that any underserved population has higher rates of mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. Obviously, that goes along with being underserved and the stigma and the disparities that exist for these patients. Having providers educate themselves about what those disparities are and how they impact a patient’s daily life and health is paramount to knowing how to treat patients.

What are your top health concerns for these patients and how do you address them?

Dr. Brandt: I think mental health and safety is probably the number one for me. About 41% of transgender adults have attempted suicide. That number is roughly 51% in transgender youth. That is an astonishing number. These patients have much higher rates of domestic violence, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault, especially trans women and trans women of color. So understanding those statistics is huge.

Obesity, smoking, and substance abuse are my next three. Again, those are things that should be addressed at any visit, regardless of the gender identity or sexual orientation of the patient, but those rates are particularly high in this population.

Fertility and long-term care for patients should be addressed. Many patients who identify as transgender are told they can’t have a family. As a primary care physician, you may see a patient before they are seen by an ob.gyn. or surgeon. Talking about what a patient’s long-term life goals are with fertility and family planning, and what that looks like for them, is a big thing for me. Other providers may not feel that’s a concern, but I believe it should be discussed before initiation of hormone therapy, which can significantly impact fertility in some patients.

Are there nuances to the physical examination that primary care physicians should be aware of when dealing with transmasculine patients vs. transfeminine patients?

Dr. Brandt: Absolutely. And this interview can’t cover the scope of those nuances. An example that comes to mind is the genital exam. For transgender women who have undergone a vaginoplasty, the pelvic exam can be very affirming. Whereas for transgender men, a gynecologic exam can significantly exacerbate dysphoria and there are ways to conduct the exam to limit this discomfort and avoid creating a traumatic experience for the patient. It’s important to be aware that the genital exam, or any type of genitourinary exam, can be either affirming or not affirming.

Sexually transmitted infections are up in the general population, and the trans population is at even higher risk. What should physicians think about when they assess this risk?

Dr. Brandt: It’s really important for primary care clinicians and for gynecologists to learn to be comfortable talking about sexual practices, because what people do behind closed doors is really a key to how to counsel patients about safe sex.

People are well aware of the need to have safe sex. However, depending on the type of sex that you’re having, what body parts go where, what is truly safe can vary and people may not know, for example, to wear a condom when sex toys are involved or that a transgender male on testosterone can become pregnant during penile-vaginal intercourse. Providers really should be very educated on the array of sexual practices that people have and how to counsel them about those. They should know how to ask patients the gender identity of their sexual partners, the sexual orientation of their partners, and what parts go where during sex.

Providers should also talk to patients about PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis], whether they identify as cisgender or transgender. My trans patients tend to be a lot more educated about PrEP than other patients. It’s something that many of the residents, even in a standard gynecologic clinic, for example, don’t talk to cisgender patients about because of the stigma surrounding HIV. Many providers still think that the only people who are at risk for HIV are men who have sex with men. And while those rates are higher in some populations, depending on sexual practices, those aren’t the only patients who qualify for PrEP.

Overall, in order to counsel patients about STIs and safe sexual practices, providers should learn to be comfortable talking about sex.

Do you have any strategies on how to make the appointment more successful in addressing those issues?

Dr. Brandt: Bedside manner is a hard thing to teach, and comfort in talking about sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation can vary – but there are a lot of continuing medical education courses that physicians can utilize through the World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

If providers start to notice an influx of patients who identify as transgender or if they want to start seeing transgender patients, it’s really important for them to have that training before they start interacting with patients. In all of medicine, we sort of learn as we go, but this patient population has been subjected to discrimination, violence, error, and misgendering. They have dealt with providers who didn’t understand their health care needs. While this field is evolving, knowing how to appropriately address a patient (using their correct name, pronouns, etc.) is an absolute must.

That needs to be part of a provider’s routine vernacular and not something that they sort of stumble through. You can scare a patient away as soon as they walk into the office with an uneducated front desk staff and things that are seen in the office. Seeking out those educational tools, being aware of your own deficits as a provider and the educational needs of your office, and addressing those needs is really key.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Lactic Acidosis in a Chronic Marijuana User

A 57-year-old woman with a history of traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, migraines, hypothyroidism, and a hiatal hernia repair presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of nausea, vomiting, and diffuse abdominal pain. She reported that her symptoms were relieved by hot showers. She also reported having similar symptoms and a previous gastric-emptying study that showed a slow-emptying stomach. Her history also consisted of frequent cannabis use for mood and appetite stimulation along with eliminating meat and fish from her diet, an increase in consumption of simple carbohydrates in the past year, and no alcohol use. Her medications included topiramate 100 mg and clonidine 0.3 mg nightly for migraines; levothyroxine 200 mcg daily for hypothyroidism; tizanidine 4 mg twice a day for muscle spasm; famotidine 40 mg twice a day as needed for gastric reflux; and bupropion 50 mg daily, citalopram 20 mg daily, and lamotrigine 25 mg nightly for mood.

The patient’s physical examination was notable for bradycardia (43 beats/min) and epigastric tenderness. Admission laboratory results were notable for an elevated lactic acid level of 4.8 (normal range, 0.50-2.20) mmol/L and a leukocytosis count of 10.8×109 cells/L. Serum alcohol level and blood cultures were negative. Liver function test, hemoglobin A1c, and lipase test were unremarkable. Her electrocardiogram showed an unchanged right bundle branch block. Chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen/pelvis and echocardiogram were unremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

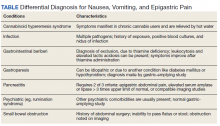

This patient was diagnosed with gastrointestinal beriberi. Because of her dietary changes, lactic acidosis, and bradycardia, thiamine deficiency was suspected after ruling out other possibilities on the differential diagnosis (Table). The patient’s symptoms resolved after administration of high-dose IV thiamine 500 mg 3 times daily for 4 days. Her white blood cell count and lactic acid level normalized. Unfortunately, thiamine levels were not obtained for the patient before treatment was initiated. After administration of IV thiamine, her plasma thiamine level was > 1,200 (normal range, 8-30) nmol/L.

Her differential diagnosis included infectious etiology. Given her leukocytosis and lactic acidosis, vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were started on admission. One day later, her leukocytosis count doubled to 20.7×109 cells/L. However, after 48 hours of negative blood cultures, antibiotics were discontinued.

Small bowel obstruction was suspected due to the patient’s history of abdominal surgery but was ruled out with CT imaging. Similarly, pancreatitis was ruled out based on negative CT imaging and the patient’s normal lipase level. Gastroparesis also was considered because of the patient’s history of hypothyroidism, tobacco use, and her prior gastric-emptying study. The patient was treated for gastroparesis with a course of metoclopramide and erythromycin without improvement in symptoms. Additionally, gastroparesis would not explain the patient’s leukocytosis.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was suspected because the patient’s symptoms improved with cannabis discontinuation and hot showers.1 In chronic users, however, tetrahydrocannabinol levels have a half-life of 5 to 13 days.2 Although lactic acidosis and leukocytosis have been previously reported with cannabis use, it is unlikely that the patient would have such significant improvement within the first 4 days after discontinuation.1,3,4 Although the patient had many psychiatric comorbidities with previous hospitalizations describing concern for somatization disorder, her leukocytosis and elevated lactic acid levels were suggestive of an organic rather than a psychiatric etiology of her symptoms.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal beriberi has been reported in chronic cannabis users who present with nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, leukocytosis, and lactic acidosis; all these symptoms rapidly improve after thiamine administration.5,6 The patient’s dietary change also eliminated her intake of vitamin B12, which compounded her condition. Thiamine deficiency produces lactic acidosis by disrupting pyruvate metabolism.7 Bradycardia also can be a sign of thiamine deficiency, although the patient’s use of clonidine for migraines is a confounder.8

Chronically ill patients are prone to nutritional deficiencies, including deficiencies of thiamine.7,9 Many patients with chronic illnesses also use cannabis to ameliorate physical and neuropsychiatric symptoms.2 Recent reports suggest cannabis users are prone to gastrointestinal beriberi and Wernicke encephalopathy.5,10 Treating gastrointestinal symptoms in these patients can be challenging to diagnose because gastrointestinal beriberi and CHS share many clinical manifestations.

The patient’s presentation is likely multifactorial resulting from the combination of gastrointestinal beriberi and CHS. However, thiamine deficiency seems to play the dominant role.

There is no standard treatment regimen for thiamine deficiency with neurologic deficits, and patients only retain about 10 to 15% of intramuscular (IM) injections of cyanocobalamin.11,12 The British Committee for Standards in Haematology recommends IM injections of 1,000 mcg of cyanocobalamin 3 times a week for 2 weeks and then reassess the need for continued treatment.13 The British Columbia guidelines also recommend IM injections of 1,000 mcg daily for 1 to 5 days before transitioning to oral repletion.14 European Neurology guidelines for the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy recommend IV cyanocobalamin 200 mg 3 times daily.15 Low-level evidence with observational studies informs these decisions and is why there is variation.

The patient’s serum lactate and leukocytosis normalized 1 day after the administration of thiamine. Thiamine deficiency classically causes Wernicke encephalopathy and wet beriberi.16 The patient did not present with Wernicke encephalopathy’s triad: ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, or confusion. She also was euvolemic without signs or symptoms of wet beriberi.

Conclusions

Thiamine deficiency is principally a clinical diagnosis. Thiamine laboratory testing may not be readily available in all medical centers, and confirming a diagnosis of thiamine deficiency should not delay treatment when thiamine deficiency is suspected. This patient’s thiamine levels resulted a week after collection. The administration of thiamine before sampling also can alter the result as it did in this case. Additionally, laboratories may offer whole blood and serum testing. Whole blood testing is more accurate because most bioactive thiamine is found in red blood cells.17

1. Price SL, Fisher C, Kumar R, Hilgerson A. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome as the underlying cause of intractable nausea and vomiting. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111(3):166-169. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2011.111.3.166

2. Sharma P, Murthy P, Bharath MM. Chemistry, metabolism, and toxicology of cannabis: clinical implications. Iran J Psychiatry. 2012;7(4):149-156.

3. Antill T, Jakkoju A, Dieguez J, Laskhmiprasad L. Lactic acidosis: a rare manifestation of synthetic marijuana intoxication. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167(3):155.

4. Sullivan S. Cannabinoid hyperemesis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):284-285. doi:10.1155/2010/481940

5. Duca J, Lum CJ, Lo AM. Elevated lactate secondary to gastrointestinal beriberi. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):133-136. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3326-2

6. Prakash S. Gastrointestinal beriberi: a forme fruste of Wernicke’s encephalopathy? BMJ Case Rep. 2018;bcr2018224841. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224841

7. Friedenberg AS, Brandoff DE, Schiffman FJ. Type B lactic acidosis as a severe metabolic complication in lymphoma and leukemia: a case series from a single institution and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86(4):225-232. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318125759a

8. Liang CC. Bradycardia in thiamin deficiency and the role of glyoxylate. J Nutrition Sci Vitaminology. 1977;23(1):1-6. doi:10.3177/jnsv.23.1

9. Attaluri P, Castillo A, Edriss H, Nugent K. Thiamine deficiency: an important consideration in critically ill patients. Am J Med Sci. 2018;356(4):382-390. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.06.015

10. Chaudhari A, Li ZY, Long A, Afshinnik A. Heavy cannabis use associated with Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Cureus. 2019;11(7):e5109. doi:10.7759/cureus.5109

11. Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):149-160. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1113996

12. Green R, Allen LH, Bjørke-Monsen A-L, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17040. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.40

13. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

14. British Columbia Ministry of Health; Guidelines and Protocols and Advisory Committee. Guidelines and protocols cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency–investigation & management. Effective January 1, 2012. Revised May 1, 2013. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/vitamin-b12

15. Galvin R, Brathen G, Ivashynka A, Hillbom M, Tanasescu R, Leone MA. EFNS guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):1408-1418. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03153.x

16. Wiley KD, Gupta M. Vitamin B1 thiamine deficiency (beriberi). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

17. Jenco J, Krcmova LK, Solichova D, Solich P. Recent trends in determination of thiamine and its derivatives in clinical practice. J Chromatogra A. 2017;1510:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2017.06.048

A 57-year-old woman with a history of traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, migraines, hypothyroidism, and a hiatal hernia repair presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of nausea, vomiting, and diffuse abdominal pain. She reported that her symptoms were relieved by hot showers. She also reported having similar symptoms and a previous gastric-emptying study that showed a slow-emptying stomach. Her history also consisted of frequent cannabis use for mood and appetite stimulation along with eliminating meat and fish from her diet, an increase in consumption of simple carbohydrates in the past year, and no alcohol use. Her medications included topiramate 100 mg and clonidine 0.3 mg nightly for migraines; levothyroxine 200 mcg daily for hypothyroidism; tizanidine 4 mg twice a day for muscle spasm; famotidine 40 mg twice a day as needed for gastric reflux; and bupropion 50 mg daily, citalopram 20 mg daily, and lamotrigine 25 mg nightly for mood.

The patient’s physical examination was notable for bradycardia (43 beats/min) and epigastric tenderness. Admission laboratory results were notable for an elevated lactic acid level of 4.8 (normal range, 0.50-2.20) mmol/L and a leukocytosis count of 10.8×109 cells/L. Serum alcohol level and blood cultures were negative. Liver function test, hemoglobin A1c, and lipase test were unremarkable. Her electrocardiogram showed an unchanged right bundle branch block. Chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen/pelvis and echocardiogram were unremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

This patient was diagnosed with gastrointestinal beriberi. Because of her dietary changes, lactic acidosis, and bradycardia, thiamine deficiency was suspected after ruling out other possibilities on the differential diagnosis (Table). The patient’s symptoms resolved after administration of high-dose IV thiamine 500 mg 3 times daily for 4 days. Her white blood cell count and lactic acid level normalized. Unfortunately, thiamine levels were not obtained for the patient before treatment was initiated. After administration of IV thiamine, her plasma thiamine level was > 1,200 (normal range, 8-30) nmol/L.

Her differential diagnosis included infectious etiology. Given her leukocytosis and lactic acidosis, vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were started on admission. One day later, her leukocytosis count doubled to 20.7×109 cells/L. However, after 48 hours of negative blood cultures, antibiotics were discontinued.

Small bowel obstruction was suspected due to the patient’s history of abdominal surgery but was ruled out with CT imaging. Similarly, pancreatitis was ruled out based on negative CT imaging and the patient’s normal lipase level. Gastroparesis also was considered because of the patient’s history of hypothyroidism, tobacco use, and her prior gastric-emptying study. The patient was treated for gastroparesis with a course of metoclopramide and erythromycin without improvement in symptoms. Additionally, gastroparesis would not explain the patient’s leukocytosis.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was suspected because the patient’s symptoms improved with cannabis discontinuation and hot showers.1 In chronic users, however, tetrahydrocannabinol levels have a half-life of 5 to 13 days.2 Although lactic acidosis and leukocytosis have been previously reported with cannabis use, it is unlikely that the patient would have such significant improvement within the first 4 days after discontinuation.1,3,4 Although the patient had many psychiatric comorbidities with previous hospitalizations describing concern for somatization disorder, her leukocytosis and elevated lactic acid levels were suggestive of an organic rather than a psychiatric etiology of her symptoms.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal beriberi has been reported in chronic cannabis users who present with nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, leukocytosis, and lactic acidosis; all these symptoms rapidly improve after thiamine administration.5,6 The patient’s dietary change also eliminated her intake of vitamin B12, which compounded her condition. Thiamine deficiency produces lactic acidosis by disrupting pyruvate metabolism.7 Bradycardia also can be a sign of thiamine deficiency, although the patient’s use of clonidine for migraines is a confounder.8

Chronically ill patients are prone to nutritional deficiencies, including deficiencies of thiamine.7,9 Many patients with chronic illnesses also use cannabis to ameliorate physical and neuropsychiatric symptoms.2 Recent reports suggest cannabis users are prone to gastrointestinal beriberi and Wernicke encephalopathy.5,10 Treating gastrointestinal symptoms in these patients can be challenging to diagnose because gastrointestinal beriberi and CHS share many clinical manifestations.

The patient’s presentation is likely multifactorial resulting from the combination of gastrointestinal beriberi and CHS. However, thiamine deficiency seems to play the dominant role.

There is no standard treatment regimen for thiamine deficiency with neurologic deficits, and patients only retain about 10 to 15% of intramuscular (IM) injections of cyanocobalamin.11,12 The British Committee for Standards in Haematology recommends IM injections of 1,000 mcg of cyanocobalamin 3 times a week for 2 weeks and then reassess the need for continued treatment.13 The British Columbia guidelines also recommend IM injections of 1,000 mcg daily for 1 to 5 days before transitioning to oral repletion.14 European Neurology guidelines for the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy recommend IV cyanocobalamin 200 mg 3 times daily.15 Low-level evidence with observational studies informs these decisions and is why there is variation.

The patient’s serum lactate and leukocytosis normalized 1 day after the administration of thiamine. Thiamine deficiency classically causes Wernicke encephalopathy and wet beriberi.16 The patient did not present with Wernicke encephalopathy’s triad: ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, or confusion. She also was euvolemic without signs or symptoms of wet beriberi.

Conclusions

Thiamine deficiency is principally a clinical diagnosis. Thiamine laboratory testing may not be readily available in all medical centers, and confirming a diagnosis of thiamine deficiency should not delay treatment when thiamine deficiency is suspected. This patient’s thiamine levels resulted a week after collection. The administration of thiamine before sampling also can alter the result as it did in this case. Additionally, laboratories may offer whole blood and serum testing. Whole blood testing is more accurate because most bioactive thiamine is found in red blood cells.17

A 57-year-old woman with a history of traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, migraines, hypothyroidism, and a hiatal hernia repair presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of nausea, vomiting, and diffuse abdominal pain. She reported that her symptoms were relieved by hot showers. She also reported having similar symptoms and a previous gastric-emptying study that showed a slow-emptying stomach. Her history also consisted of frequent cannabis use for mood and appetite stimulation along with eliminating meat and fish from her diet, an increase in consumption of simple carbohydrates in the past year, and no alcohol use. Her medications included topiramate 100 mg and clonidine 0.3 mg nightly for migraines; levothyroxine 200 mcg daily for hypothyroidism; tizanidine 4 mg twice a day for muscle spasm; famotidine 40 mg twice a day as needed for gastric reflux; and bupropion 50 mg daily, citalopram 20 mg daily, and lamotrigine 25 mg nightly for mood.

The patient’s physical examination was notable for bradycardia (43 beats/min) and epigastric tenderness. Admission laboratory results were notable for an elevated lactic acid level of 4.8 (normal range, 0.50-2.20) mmol/L and a leukocytosis count of 10.8×109 cells/L. Serum alcohol level and blood cultures were negative. Liver function test, hemoglobin A1c, and lipase test were unremarkable. Her electrocardiogram showed an unchanged right bundle branch block. Chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen/pelvis and echocardiogram were unremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

This patient was diagnosed with gastrointestinal beriberi. Because of her dietary changes, lactic acidosis, and bradycardia, thiamine deficiency was suspected after ruling out other possibilities on the differential diagnosis (Table). The patient’s symptoms resolved after administration of high-dose IV thiamine 500 mg 3 times daily for 4 days. Her white blood cell count and lactic acid level normalized. Unfortunately, thiamine levels were not obtained for the patient before treatment was initiated. After administration of IV thiamine, her plasma thiamine level was > 1,200 (normal range, 8-30) nmol/L.

Her differential diagnosis included infectious etiology. Given her leukocytosis and lactic acidosis, vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were started on admission. One day later, her leukocytosis count doubled to 20.7×109 cells/L. However, after 48 hours of negative blood cultures, antibiotics were discontinued.

Small bowel obstruction was suspected due to the patient’s history of abdominal surgery but was ruled out with CT imaging. Similarly, pancreatitis was ruled out based on negative CT imaging and the patient’s normal lipase level. Gastroparesis also was considered because of the patient’s history of hypothyroidism, tobacco use, and her prior gastric-emptying study. The patient was treated for gastroparesis with a course of metoclopramide and erythromycin without improvement in symptoms. Additionally, gastroparesis would not explain the patient’s leukocytosis.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was suspected because the patient’s symptoms improved with cannabis discontinuation and hot showers.1 In chronic users, however, tetrahydrocannabinol levels have a half-life of 5 to 13 days.2 Although lactic acidosis and leukocytosis have been previously reported with cannabis use, it is unlikely that the patient would have such significant improvement within the first 4 days after discontinuation.1,3,4 Although the patient had many psychiatric comorbidities with previous hospitalizations describing concern for somatization disorder, her leukocytosis and elevated lactic acid levels were suggestive of an organic rather than a psychiatric etiology of her symptoms.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal beriberi has been reported in chronic cannabis users who present with nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, leukocytosis, and lactic acidosis; all these symptoms rapidly improve after thiamine administration.5,6 The patient’s dietary change also eliminated her intake of vitamin B12, which compounded her condition. Thiamine deficiency produces lactic acidosis by disrupting pyruvate metabolism.7 Bradycardia also can be a sign of thiamine deficiency, although the patient’s use of clonidine for migraines is a confounder.8

Chronically ill patients are prone to nutritional deficiencies, including deficiencies of thiamine.7,9 Many patients with chronic illnesses also use cannabis to ameliorate physical and neuropsychiatric symptoms.2 Recent reports suggest cannabis users are prone to gastrointestinal beriberi and Wernicke encephalopathy.5,10 Treating gastrointestinal symptoms in these patients can be challenging to diagnose because gastrointestinal beriberi and CHS share many clinical manifestations.

The patient’s presentation is likely multifactorial resulting from the combination of gastrointestinal beriberi and CHS. However, thiamine deficiency seems to play the dominant role.

There is no standard treatment regimen for thiamine deficiency with neurologic deficits, and patients only retain about 10 to 15% of intramuscular (IM) injections of cyanocobalamin.11,12 The British Committee for Standards in Haematology recommends IM injections of 1,000 mcg of cyanocobalamin 3 times a week for 2 weeks and then reassess the need for continued treatment.13 The British Columbia guidelines also recommend IM injections of 1,000 mcg daily for 1 to 5 days before transitioning to oral repletion.14 European Neurology guidelines for the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy recommend IV cyanocobalamin 200 mg 3 times daily.15 Low-level evidence with observational studies informs these decisions and is why there is variation.

The patient’s serum lactate and leukocytosis normalized 1 day after the administration of thiamine. Thiamine deficiency classically causes Wernicke encephalopathy and wet beriberi.16 The patient did not present with Wernicke encephalopathy’s triad: ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, or confusion. She also was euvolemic without signs or symptoms of wet beriberi.

Conclusions

Thiamine deficiency is principally a clinical diagnosis. Thiamine laboratory testing may not be readily available in all medical centers, and confirming a diagnosis of thiamine deficiency should not delay treatment when thiamine deficiency is suspected. This patient’s thiamine levels resulted a week after collection. The administration of thiamine before sampling also can alter the result as it did in this case. Additionally, laboratories may offer whole blood and serum testing. Whole blood testing is more accurate because most bioactive thiamine is found in red blood cells.17

1. Price SL, Fisher C, Kumar R, Hilgerson A. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome as the underlying cause of intractable nausea and vomiting. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111(3):166-169. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2011.111.3.166

2. Sharma P, Murthy P, Bharath MM. Chemistry, metabolism, and toxicology of cannabis: clinical implications. Iran J Psychiatry. 2012;7(4):149-156.

3. Antill T, Jakkoju A, Dieguez J, Laskhmiprasad L. Lactic acidosis: a rare manifestation of synthetic marijuana intoxication. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167(3):155.

4. Sullivan S. Cannabinoid hyperemesis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):284-285. doi:10.1155/2010/481940

5. Duca J, Lum CJ, Lo AM. Elevated lactate secondary to gastrointestinal beriberi. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):133-136. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3326-2

6. Prakash S. Gastrointestinal beriberi: a forme fruste of Wernicke’s encephalopathy? BMJ Case Rep. 2018;bcr2018224841. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224841

7. Friedenberg AS, Brandoff DE, Schiffman FJ. Type B lactic acidosis as a severe metabolic complication in lymphoma and leukemia: a case series from a single institution and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86(4):225-232. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318125759a

8. Liang CC. Bradycardia in thiamin deficiency and the role of glyoxylate. J Nutrition Sci Vitaminology. 1977;23(1):1-6. doi:10.3177/jnsv.23.1

9. Attaluri P, Castillo A, Edriss H, Nugent K. Thiamine deficiency: an important consideration in critically ill patients. Am J Med Sci. 2018;356(4):382-390. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.06.015

10. Chaudhari A, Li ZY, Long A, Afshinnik A. Heavy cannabis use associated with Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Cureus. 2019;11(7):e5109. doi:10.7759/cureus.5109

11. Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):149-160. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1113996

12. Green R, Allen LH, Bjørke-Monsen A-L, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17040. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.40

13. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

14. British Columbia Ministry of Health; Guidelines and Protocols and Advisory Committee. Guidelines and protocols cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency–investigation & management. Effective January 1, 2012. Revised May 1, 2013. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/vitamin-b12

15. Galvin R, Brathen G, Ivashynka A, Hillbom M, Tanasescu R, Leone MA. EFNS guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):1408-1418. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03153.x

16. Wiley KD, Gupta M. Vitamin B1 thiamine deficiency (beriberi). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

17. Jenco J, Krcmova LK, Solichova D, Solich P. Recent trends in determination of thiamine and its derivatives in clinical practice. J Chromatogra A. 2017;1510:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2017.06.048

1. Price SL, Fisher C, Kumar R, Hilgerson A. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome as the underlying cause of intractable nausea and vomiting. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111(3):166-169. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2011.111.3.166

2. Sharma P, Murthy P, Bharath MM. Chemistry, metabolism, and toxicology of cannabis: clinical implications. Iran J Psychiatry. 2012;7(4):149-156.

3. Antill T, Jakkoju A, Dieguez J, Laskhmiprasad L. Lactic acidosis: a rare manifestation of synthetic marijuana intoxication. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167(3):155.

4. Sullivan S. Cannabinoid hyperemesis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):284-285. doi:10.1155/2010/481940

5. Duca J, Lum CJ, Lo AM. Elevated lactate secondary to gastrointestinal beriberi. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):133-136. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3326-2

6. Prakash S. Gastrointestinal beriberi: a forme fruste of Wernicke’s encephalopathy? BMJ Case Rep. 2018;bcr2018224841. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224841

7. Friedenberg AS, Brandoff DE, Schiffman FJ. Type B lactic acidosis as a severe metabolic complication in lymphoma and leukemia: a case series from a single institution and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86(4):225-232. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318125759a

8. Liang CC. Bradycardia in thiamin deficiency and the role of glyoxylate. J Nutrition Sci Vitaminology. 1977;23(1):1-6. doi:10.3177/jnsv.23.1

9. Attaluri P, Castillo A, Edriss H, Nugent K. Thiamine deficiency: an important consideration in critically ill patients. Am J Med Sci. 2018;356(4):382-390. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.06.015

10. Chaudhari A, Li ZY, Long A, Afshinnik A. Heavy cannabis use associated with Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Cureus. 2019;11(7):e5109. doi:10.7759/cureus.5109

11. Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):149-160. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1113996

12. Green R, Allen LH, Bjørke-Monsen A-L, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17040. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.40

13. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

14. British Columbia Ministry of Health; Guidelines and Protocols and Advisory Committee. Guidelines and protocols cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency–investigation & management. Effective January 1, 2012. Revised May 1, 2013. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/vitamin-b12

15. Galvin R, Brathen G, Ivashynka A, Hillbom M, Tanasescu R, Leone MA. EFNS guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):1408-1418. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03153.x

16. Wiley KD, Gupta M. Vitamin B1 thiamine deficiency (beriberi). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

17. Jenco J, Krcmova LK, Solichova D, Solich P. Recent trends in determination of thiamine and its derivatives in clinical practice. J Chromatogra A. 2017;1510:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2017.06.048

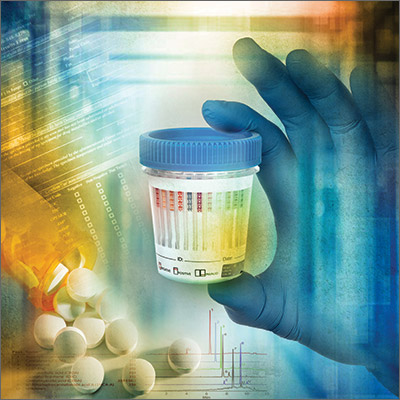

Urine drug screening: A guide to monitoring Tx with controlled substances

An estimated 20 million patients in the United States have a substance use disorder (SUD), with hundreds of millions of prescriptions for controlled substances written annually. Consequently, urine drug screening (UDS) has become widely utilized to evaluate and treat patients with an SUD or on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy.1

Used appropriately, UDS can be a valuable tool; there is ample evidence, however, that it has been misused, by some physicians, to stigmatize patients who use drugs of abuse,2 profile patients racially,2 profit from excessive testing,3 and inappropriately discontinue treatment.4

A patient-centered approach. We have extensive clinical experience in the use and interpretation of urine toxicology, serving as clinical leads in busy family medicine residency practices that care for patients with SUDs, and are often consulted regarding patients on chronic opioid or benzodiazepine therapy. We have encountered countless situations in which the correct interpretation of UDS is critical to providing care.

Over time, and after considerable trial and error, we developed the patient-centered approach to urine toxicology described in this article. We believe that the medical evidence strongly supports our approach to the appropriate use and interpretation of urine toxicology in clinical practice. Our review here is intended as a resource when you consider implementing a UDS protocol or are struggling with the management of unexpected results.

Urine toxicology for therapeutic drug monitoring

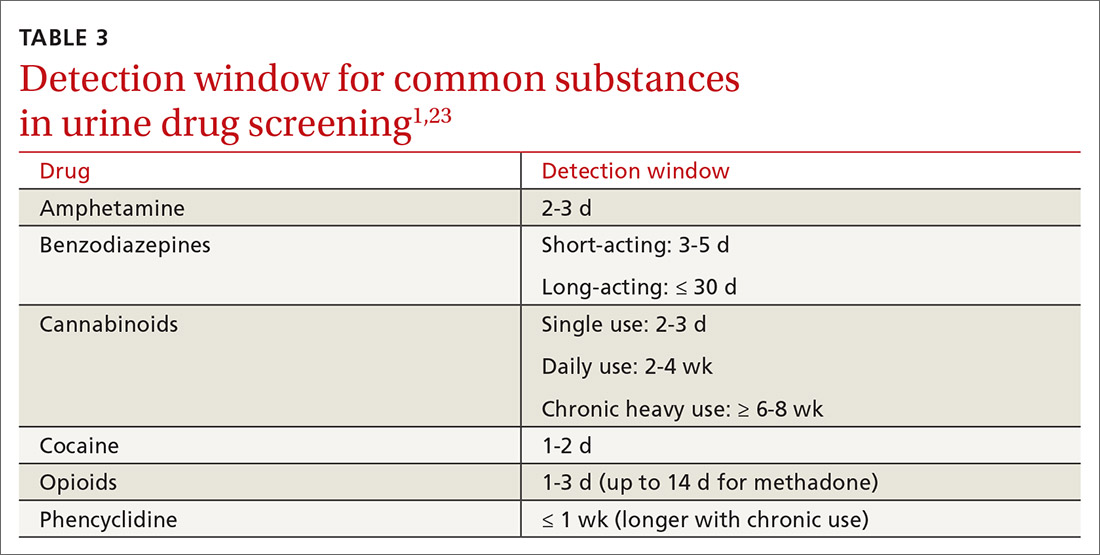

Prescribing a controlled substance carries inherent risks, including diversion, nonmedical use, and development of an SUD. Prescribed medications, particularly opioids and benzodiazepines, have been linked to a large increase in overdose deaths over the past decade.5 Several strategies have been investigated to mitigate risk (see “How frequently should a patient be tested?,” later in the article).

Clinical judgment—ie, when a physician orders a drug test upon suspecting that a patient is diverting a prescribed drug or has developed an SUD—has been shown to be highly inaccurate. Implicit racial bias might affect the physician’s judgment, leading to changes in testing and test interpretation. For example, Black patients were found to be 10% more likely to have drug screening ordered while being treated with long-term opioid therapy and 2 to 3 times more likely to have their medication discontinued as a result of a marijuana- or cocaine-positive test.2

Other studies have shown that testing patients for “bad behavior,” so to speak—reporting a prescription lost or stolen, consuming more than the prescribed dosage, visiting the office without an appointment, having multiple drug intolerances and allergies, and making frequent telephone calls to the practice—is ineffective.6 Patients with these behaviors were slightly more likely to unexpectedly test positive, or negative, on their UDS; however, many patients without suspect behavior also were found to have abnormal toxicology results.6 Data do not support therapeutic drug monitoring only of patients selected on the basis of aberrant behavior.6

Continue to: Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Questions and concerns about urine drug screening

Why not just ask the patient? Studies have evaluated whether patient self-reporting of adherence is a feasible alternative to laboratory drug screening. Regrettably, patients have repeatedly been shown to underreport their use of both prescribed and illicit drugs.7,8

That question leads to another: Why do patients lie to their physician? It is easy to assume malicious intent, but a variety of obstacles might dissuade a patient from being fully truthful with their physician:

- Monetary gain. A small, but real, percentage of medications are diverted by patients for this reason.9

- Addiction, pseudo-addiction due to tolerance, and self-medication for psychological symptoms are clinically treatable syndromes that can lead to underreporting of prescribed and nonprescribed drug and alcohol use.

- Shame. Addiction is a highly stigmatized disease, and patients might simply be ashamed to admit that they need treatment: 13% to 38% of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy in a pain management or primary care setting have a clinically diagnosable SUD.10,11

Is consent needed to test or to share test results? Historically, UDS has been performed on patients without their consent or knowledge.12 Patients give a urine specimen to their physician for a variety of reasons; it seems easy to “add on” UDS. Evidence is clear, however, that confronting a patient about an unexpected test result can make the clinical outcome worse—often resulting in irreparable damage to the patient–physician relationship.12,13 Unless the patient is experiencing a medical emergency, guidelines unanimously recommend obtaining consent prior to testing.1,5,14

Federal law requires written permission from the patient for the physician to disclose information about alcohol or substance use, unless the information is expressly needed to provide care during a medical emergency. Substance use is highly stigmatized, and patients might—legitimately—fear that sharing their history could undermine their care.1,12,14

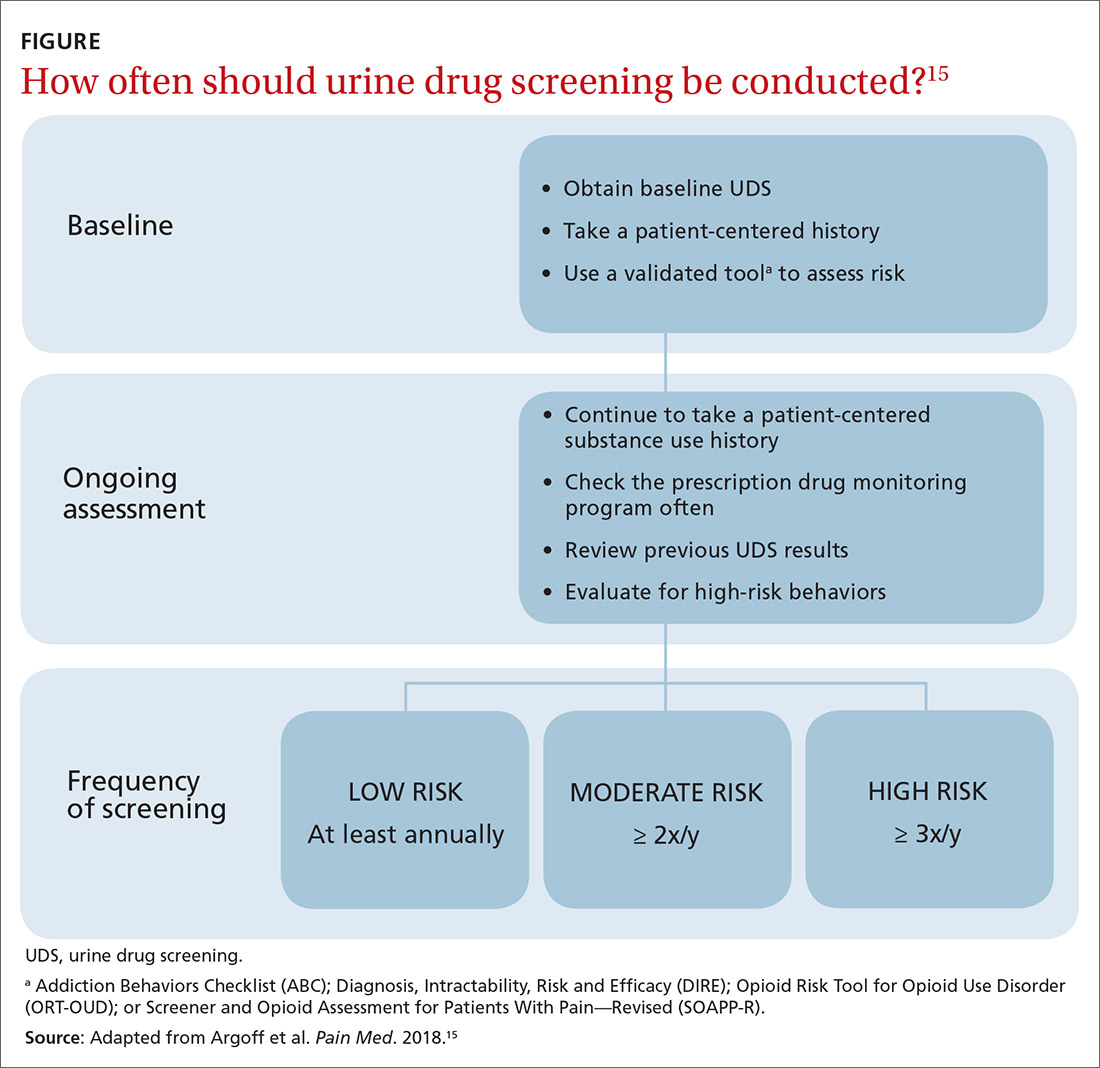

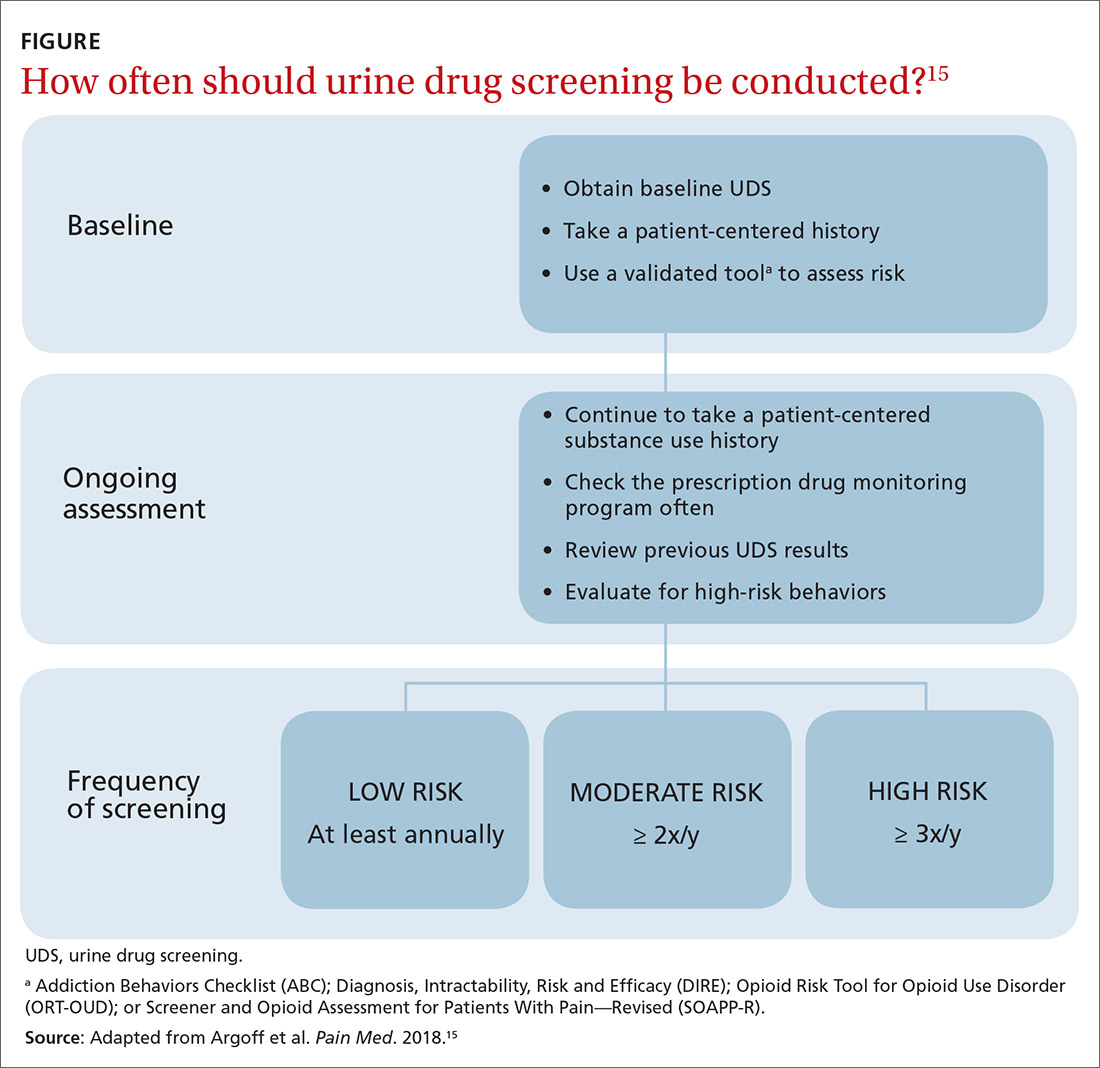

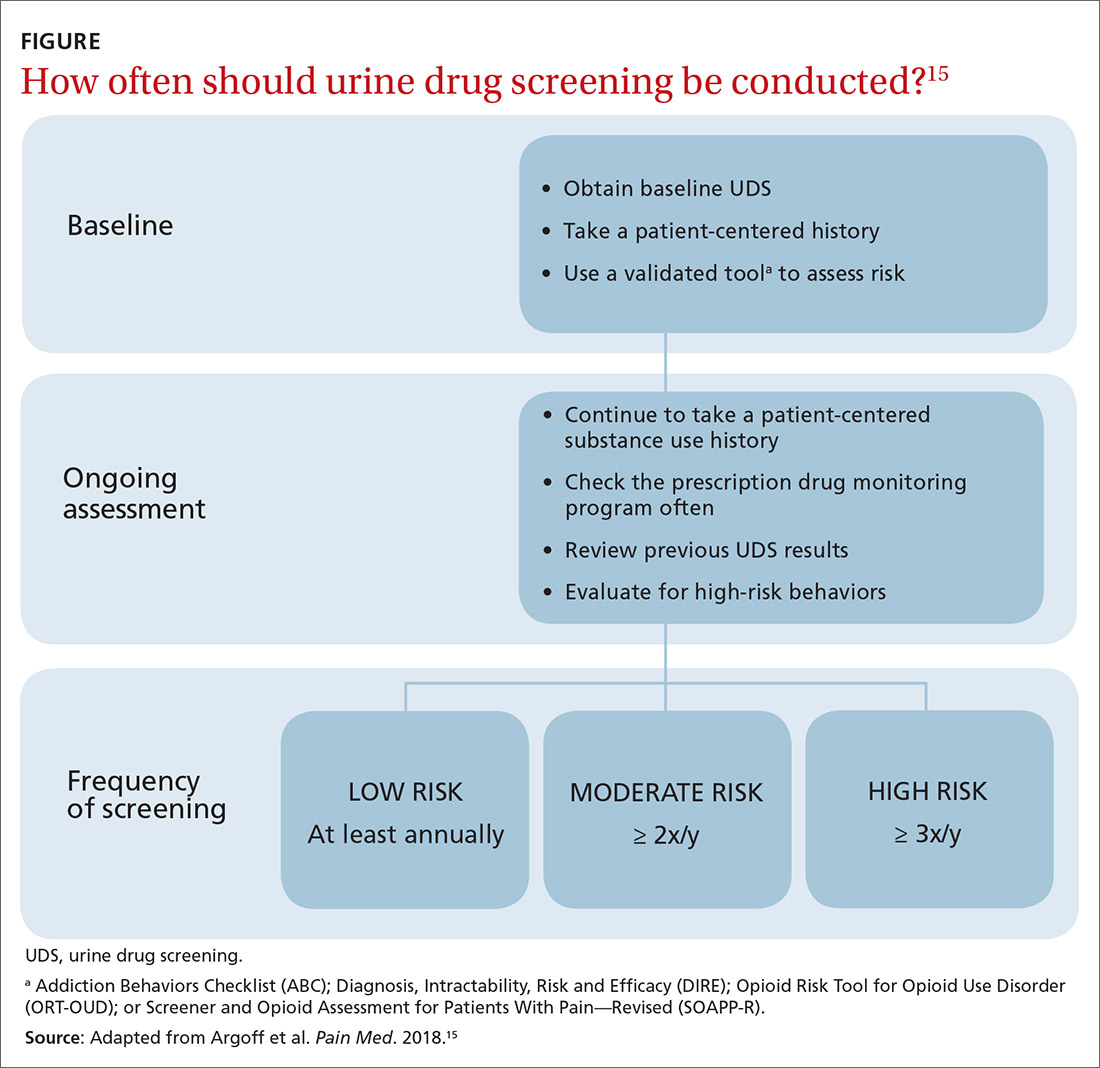

How frequently should a patient be tested? Experts recommend utilizing a risk-based strategy to determine the frequency of UDS.1,5,15 Validated risk-assessment questionnaires include:

- Opioid Risk Tool for Opioid Use Disorder (ORT-OUD)a

- Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients With Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R)b

- Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk and Efficacy (DIRE)c

- Addiction Behaviors Checklist (ABC).d

Continue to: Each of these tools...

Each of these tools takes less than 5 minutes to administer and can be used by a primary care physician to objectively quantify the risk of prescribing; there is no evidence for the use of 1 of these screeners over the others.15 It is recommended that you choose a questionnaire that works for you and incorporate the risk assessment into prescribing any high-risk medication.1,5,15

Once you have completed an initial risk assessment, the frequency of UDS can be based on ongoing assessment that incorporates baseline testing, patient self-reporting, toxicology results, behavioral monitoring, and state database monitoring through a prescription drug monitoring program. Annual screening is appropriate in low-risk patients; moderate-risk patients should be screened twice a year, and high-risk patients should be screened at least every 4 months (FIGURE).15

Many state and federal agencies, health systems, employers, and insurers mandate the frequency of testing through guidelines or legislation. These regulations often are inconsistent with the newest medical evidence.15 Consult local guidelines and review the medical evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS.

What are the cost considerations in providing UDS? Insurers have been billed as much as $4000 for definitive chromatography testing (described later).3 This has led to insurance fraud, when drug-testing practices with a financial interest routinely use large and expensive test panels, test too frequently, or unnecessarily send for confirmatory or quantitative analysis of all positive tests.3,14 Often, insurers refuse to pay for unnecessary testing, leaving patients with significant indebtedness.3,14 Take time to review the evidence and consensus recommendations on UDS to avoid waste, potential accusations of fraud, and financial burden on your patients.

Urine toxicology for addiction treatment

UDS protocols in addiction settings are often different from those in which a controlled substance is being prescribed.

Continue to: Routine and random testing

Routine and random testing. Two common practices when treating addiction are to perform UDS on all patients, at every visit, or to test randomly.1 These practices can be problematic, however. Routine testing at every visit can make urine-tampering more likely and is often unnecessary for stable patients. Random testing can reduce the risk of urine-tampering, but it is often difficult for primary care clinics to institute such a protocol. Some clinics have patients provide a urine specimen at every visit and then only send tests to the lab based on randomization.1

Contingency management—a behavioral intervention in which a patient is rewarded, or their performance is reinforced, when they display evidence of positive change—is the most effective strategy used in addiction medicine to determine the frequency of patient visits and UDS.14,16 High-risk patients with self-reported active substance use or UDS results consistent with substance use, or both, are seen more often; as their addiction behavior diminishes, visits and UDS become less frequent. If addiction behavior increases, the patient is seen more often. Keep in mind that addiction behavior decreases over months of treatment, not immediately upon initiation.14,17 For contingency management to be successful, patient-centered interviewing and UDS will need to be employed frequently as the patient works toward meaningful change.14

The technology of urine drug screening

Two general techniques are used for UDS: immunoassay and chromatography. Each plays an important role in clinical practice; physicians must therefore maintain a basic understanding of the mechanism of each technique and their comparable advantages and disadvantages. Such an understanding allows for (1) matching the appropriate technique to the individual clinical scenario and (2) correctly interpreting results.

Immunoassay technology is used for point-of-care and rapid laboratory UDS, using antibodies to detect the drug or drug metabolite of interest. Antibodies utilized in immunoassays are designed to selectively bind a specific antigen—ie, a unique chemical structure within the drug of choice. Once bound, the antigen–antibody complex can be exploited for detection through various methods.

Chromatography–mass spectrometry is considered the gold standard for UDS, yielding confirmatory results. This is a 2-step process: Chromatography separates components within a specimen; mass spectrometry then identifies those components. Most laboratories employ liquid, rather than gas, chromatography. The specificity of the liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry method is such that a false-positive result is, essentially, impossible.18

Continue to: How is the appropriate tests elected for urine drug screening?

How is the appropriate tests elected for urine drug screening?

Variables that influence your choice of the proper test method include the clinical question at hand; cost; the urgency of obtaining results; and the stakes in that decision (ie, will the results be used to simply change the dosage of a medication or, of greater consequence, to determine fitness for employment or inform criminal justice decisions?). Each method of UDS has advantages that can be utilized and disadvantages that must be considered to obtain an accurate and useful result.

Immunoassay provides rapid results, is relatively easy to perform, and is, comparatively, inexpensive.1,14 The speed of results makes this method particularly useful in settings such as the emergency department, where rapid results are crucial. Ease of use makes immunoassay ideal for the office, where non-laboratory staff can be trained to properly administer the test.

A major disadvantage of immunoassay technology, however, is interference resulting in both false-positive and false-negative results, which is discussed in detail in the next section. Immunoassay should be considered a screening test that yields presumptive results.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry is exquisitely specific and provides confirmatory test results—major advantages of the method. However, specificity comes at a price: significantly increased cost and longer wait time for results (typically days, if specimens are sent out to a laboratory). These barriers can make it impractical to employ this method in routine practice.

Interpretation of results: Not so fast

Interpreting UDS results is not as simple as noting a positive or negative result. Physicians must understand the concept of interference, so that results can be appropriately interpreted and confirmed. This is crucial when results influence clinical decisions; inappropriate action, taken on the basis of presumptive results, can have severe consequences for the patient–provider relationship and the treatment plan.1,14

Continue to: Interference falls into 2 categories...

Interference falls into 2 categories: variables inherent in the testing process and patient variables.

Antibody cross-reactivity. A major disadvantage of immunoassay technology is interference that results in false-positive and false-negative results.19,20 The source of this interference is antibody cross-reactivity—the degree to which an antibody binds to structurally similar compounds. Antibody–antigen interactions are incredibly complex; although assay antibodies are engineered to specifically detect a drug class of interest, reactivity with other, structurally similar compounds is unavoidable.

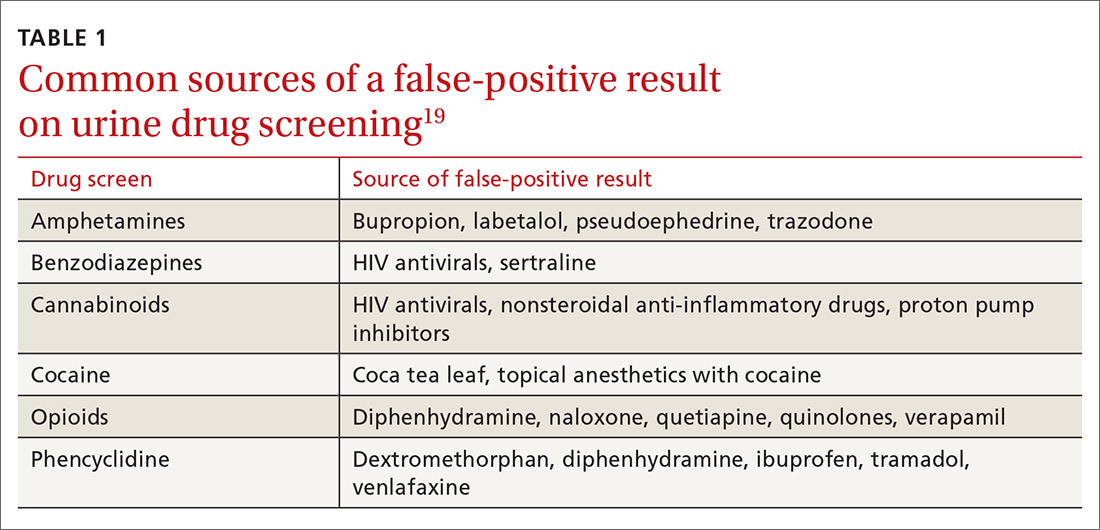

Nevertheless, cross-reactivity is a useful phenomenon that allows broad testing for multiple drugs within a class. For example, most point-of-care tests for benzodiazepines reliably detect diazepam and chlordiazepoxide. Likewise, opiate tests reliably detect natural opiates, such as morphine and codeine. Cross-reactivity is not limitless, however; most benzodiazepine immunoassays have poor reactivity to clonazepam and lorazepam, making it possible that a patient taking clonazepam tests negative for benzodiazepine on an immunoassay.14,20 Similarly, standard opioid tests have only moderate cross-reactivity for semisynthetic opioids, such as hydrocodone and hydromorphone; poor cross-reactivity for oxycodone and oxymorphone; and essentially no cross-reactivity for full synthetics, such as fentanyl and methadone.14

It is the responsibility of the ordering physician to understand cross-reactivity to various drugs within a testing class.

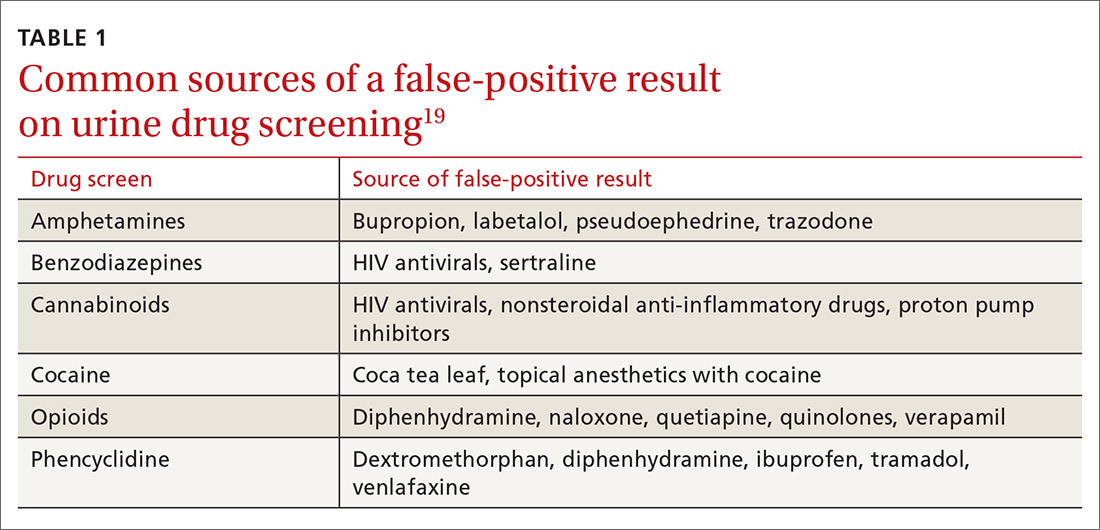

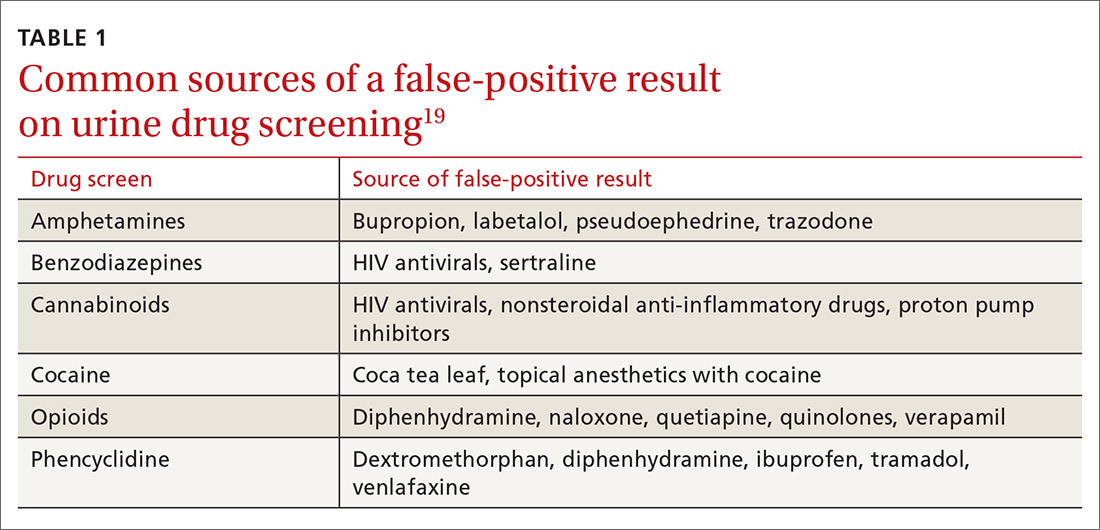

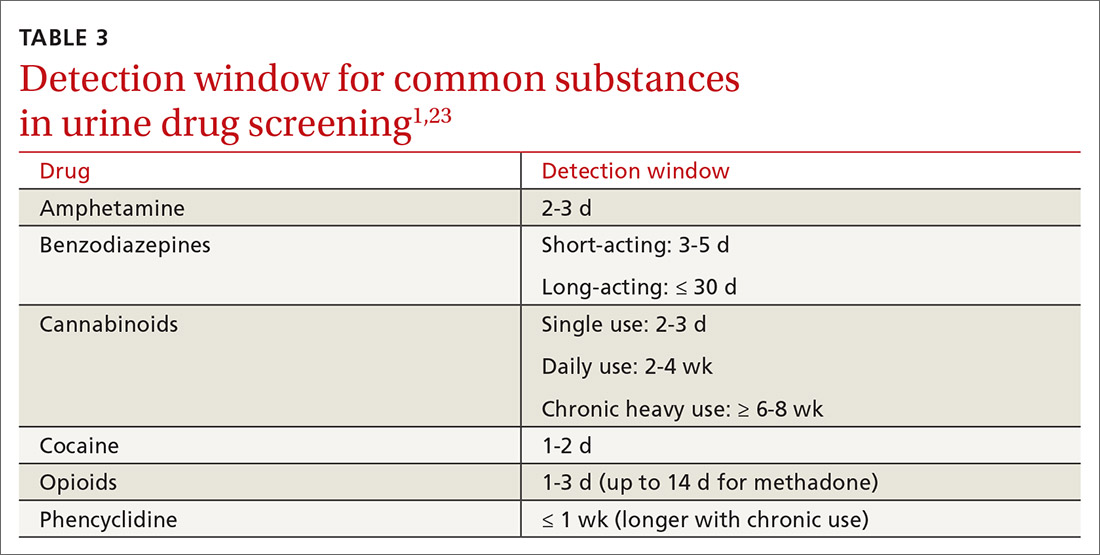

Whereas weak cross-reactivity to drugs within a class can be a source of false-negative results, cross-reactivity to drugs outside the class of interest is a source of false-positive results. An extensive review of drugs that cause false-positive immunoassay screening tests is outside the scope of this article; commonly prescribed medications implicated in false-positive results are listed in TABLE 1.19

Continue to: In general...

In general, amphetamine immunoassays produce frequent false-positive results, whereas cocaine and cannabinoid assays are more specific.1,18 Common over-the-counter medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, decongestants, and antacids, can yield false-positive results, highlighting the need to obtain a comprehensive medication list from patients, including over-the-counter and herbal medications, before ordering UDS. Because of the complexity of cross-reactivity, it might not be possible to identify the source of a false-positive result.14

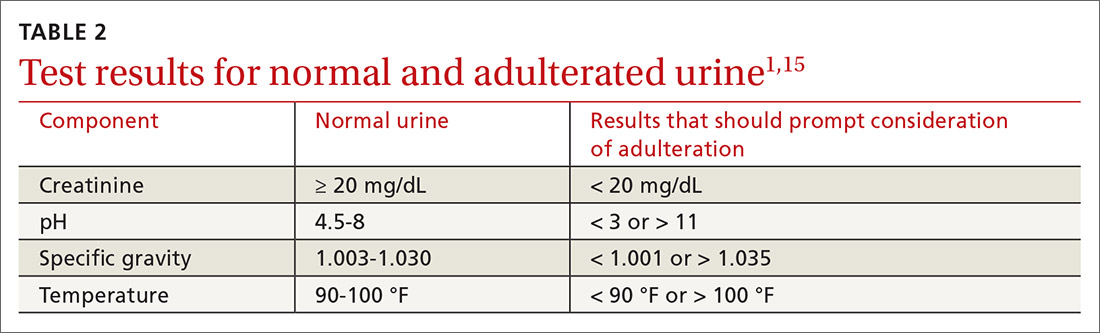

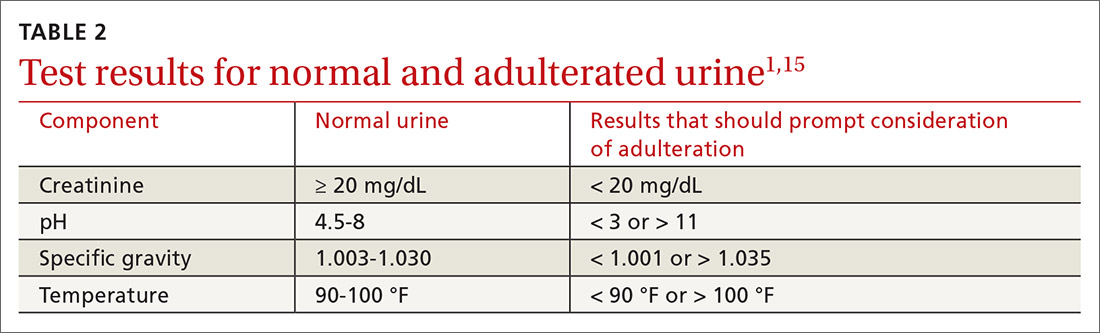

Patient variables. Intentional effort to skew results is another source of interference. The frequency of this effort varies by setting and the potential consequences of results—eg, employment testing or substance use treatment—and a range of attempts have been reported in the literature.21,22 Common practices are dilution, adulteration, and substitution.20,23

- Dilution lowers the concentration of the drug of interest below the detection limit of the assay by directly adding water to the urine specimen, drinking copious amounts of fluid, taking a diuretic, or a combination of these practices.

- Adulteration involves adding a substance to urine that interferes with the testing mechanism: for example, bleach, household cleaners, eye drops, and even commercially available products expressly marketed to interfere with UDS.24

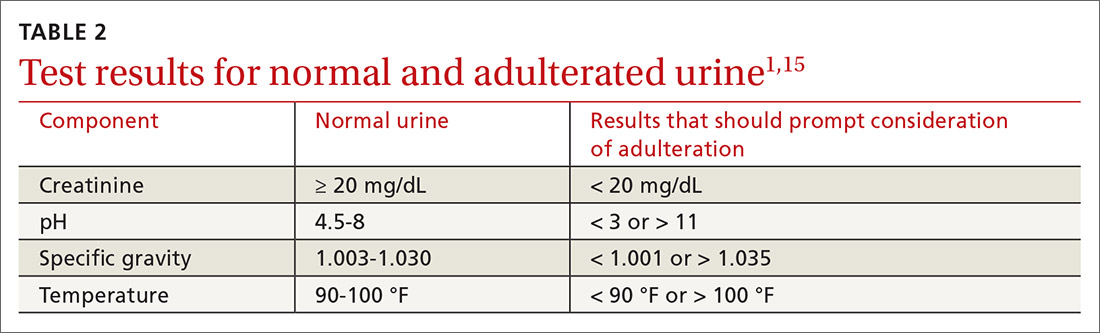

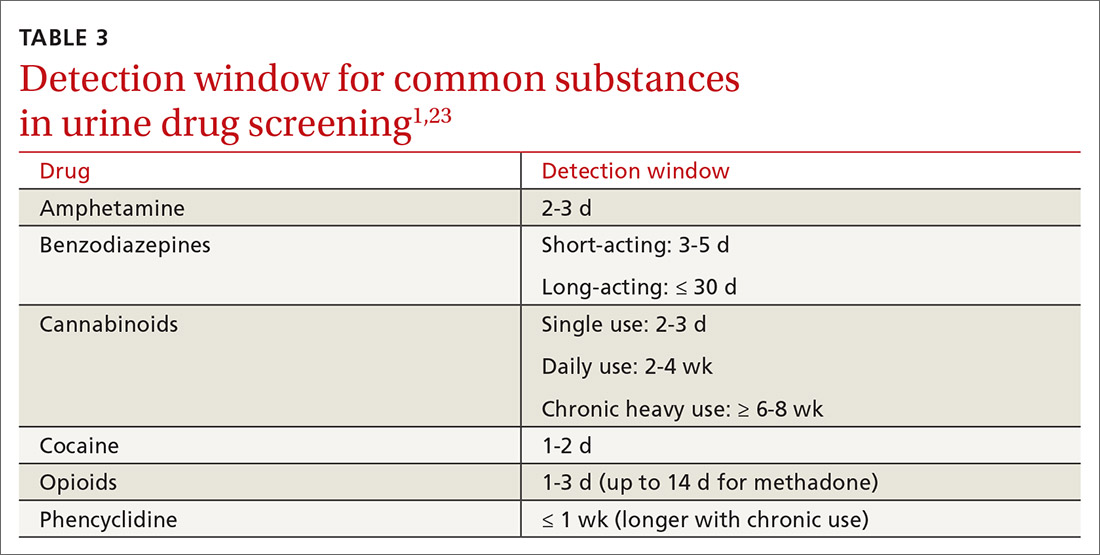

- Substitution involves providing urine or a urine-like substance for testing that did not originate from the patient.