User login

Doctor’s illegal opioid prescriptions lead to five deaths

According to court documents, between January 2014 and October 2019, family physician David Chisholm, MD, 64, of Wasilla, Alaska, wrote more than 20,000 prescriptions to approximately 350 patients for oxycodone, methadone, and hydrocodone, often prescribing the pills using variations of patients’ names in an attempt to avoid being red-flagged by payers.

When Walmart refused to continue filling the prescriptions, Dr. Chisholm told his staff to advise the patients to use other pharmacies. In addition, he often prescribed combinations of medications, such as concurrent opioids, benzodiazepines, sedatives, and carisoprodol, thus increasing the chances that his patients would become addicted to or overdose on the drugs. Chisholm, who pleaded guilty in June, acknowledged to federal officials that his prescriptions were a significant contributing factor to the overdose deaths of five of his patients during this time, according to a statement by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Alaska.

According to the Anchorage Daily News, Dr. Chisholm, who was not board certified in pain medicine, said his reason for prescribing the drugs was not to make money but to help patients suffering from chronic pain and because he enjoyed the challenge.

Dr. Chisholm’s attorney, Nick Oberheiden, told CNN his client “sacrificed his reputation as a patient advocate and his years of service to the Alaskan community” in overprescribing opioids. “He expressed his sincere remorse in open court and he accepts the consequences of his misconduct. He hopes that his case serves as a warning to other physicians facing the same dilemma when treating chronic pain.”

He surrendered his medical license in November 2020 before being formally charged in April 2021.

Texas hospital CEO, seven doctors settle kickback

A hospital executive and seven physicians have agreed to pay a total of $1.1 million to settle allegations that they violated the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law. The eight have also agreed to cooperate in investigations and litigation involving other parties.

The Texas physicians involved in the settlement are internist Jaspaul Bhangoo, MD, of Denton; family physician Robert Megna, DO, of Ferris; cardiologist Baxter Montgomery, MD, of Houston; internist Murtaza Mussaji, DO, of Houston; family physician David Sneed, DO, of Austin; family physician Kevin Lewis, DO, of Houston; and family physician Angela Mosley-Nunnery, MD, of Kingwood.

Also settling was Richard DeFoore, former CEO of Jones County Regional Healthcare (dba Stamford Memorial Hospital).

The physicians were accused of accepting payments from organizations in exchange for ordering lab tests from True Health Diagnostics, Little River Healthcare, and Boston Heart. The payments to the physicians were disguised as investment returns but, according to the allegations, were in fact offered in exchange for the doctors’ referrals. Mr. DeFoore, the hospital executive involved in the settlement, allegedly oversaw a similar scheme that benefited the now-defunct Stamford Memorial.

“Paying kickbacks to physicians distorts the medical decision-making process, corrupts our health care system, and increases the cost of healthcare funded by the taxpayer,” Brit Featherston, U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas, said in a statement announcing the agreement. “Laboratories, marketers, and physicians cannot immunize their conduct by attempting to disguise the kickbacks as some sort of investment arrangement.”

Practice administrative assistant sentenced for fraudulent prescriptions

An administrative assistant at an Illinois orthopedics office was sentenced to a year and a day in federal prison for writing fraudulent prescriptions for opioids.

Amanda Biesiada, 39, of Alsip, Ill., who worked as an administrative assistant at Hinsdale Orthopaedics in Westmont, Ill., was not a licensed physician and could not legally write the prescriptions unless instructed to do so and supervised by licensed doctors.

According to a statement by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois, the prescriptions for hydrocodone, oxycodone, and other controlled substances – 85 prescriptions in all from 2017 to 2019 – were made out to an acquaintance of Biesiada’s and written without the knowledge or approval of the providers in whose names she wrote them.

Federal officials said Ms. Biesiada attempted to conceal the fraudulent prescriptions by marking them “filed in error” in the practice’s prescription system.

Lab owner pleads guilty to $6.9 million testing fraud scheme

A Florida lab owner has pleaded guilty to conspiracy to defraud Medicare through false and fraudulent claims totaling more than $6.9 million.

According to court documents, Christopher Licata, 45, of Delray Beach, Fla., admitted to bribing patient brokers to refer orders for medically unnecessary genetic testing to his lab. The tests were then billed to Medicare.

Mr. Licata and the patient brokers entered sham agreements meant to disguise the true purpose of the payments, according to a statement from the Department of Justice. The 45-year-old owner of Boca Toxicology (dba Lab Dynamics) pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to commit health care fraud.

The scheme began in 2018; however, once the pandemic began, Mr. Licata shifted strategies, playing on patients’ fears of COVID-19 to bundle inexpensive COVID tests with more expensive medically unnecessary tests. These tests included respiratory pathogen panels and genetic testing for cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and other illnesses. In all, Mr. Licata’s laboratory submitted over $6.9 million in false and fraudulent claims to Medicare for these unnecessary tests, according to the DOJ statement.

The case is a part of the U.S. Attorney General’s COVID-19 Fraud Enforcement Task Force that was established to enhance the efforts of agencies and governments across the country to combat and prevent pandemic-related fraud.

Mr. Licata faces a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison. His sentencing is scheduled for March 24.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

According to court documents, between January 2014 and October 2019, family physician David Chisholm, MD, 64, of Wasilla, Alaska, wrote more than 20,000 prescriptions to approximately 350 patients for oxycodone, methadone, and hydrocodone, often prescribing the pills using variations of patients’ names in an attempt to avoid being red-flagged by payers.

When Walmart refused to continue filling the prescriptions, Dr. Chisholm told his staff to advise the patients to use other pharmacies. In addition, he often prescribed combinations of medications, such as concurrent opioids, benzodiazepines, sedatives, and carisoprodol, thus increasing the chances that his patients would become addicted to or overdose on the drugs. Chisholm, who pleaded guilty in June, acknowledged to federal officials that his prescriptions were a significant contributing factor to the overdose deaths of five of his patients during this time, according to a statement by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Alaska.

According to the Anchorage Daily News, Dr. Chisholm, who was not board certified in pain medicine, said his reason for prescribing the drugs was not to make money but to help patients suffering from chronic pain and because he enjoyed the challenge.

Dr. Chisholm’s attorney, Nick Oberheiden, told CNN his client “sacrificed his reputation as a patient advocate and his years of service to the Alaskan community” in overprescribing opioids. “He expressed his sincere remorse in open court and he accepts the consequences of his misconduct. He hopes that his case serves as a warning to other physicians facing the same dilemma when treating chronic pain.”

He surrendered his medical license in November 2020 before being formally charged in April 2021.

Texas hospital CEO, seven doctors settle kickback

A hospital executive and seven physicians have agreed to pay a total of $1.1 million to settle allegations that they violated the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law. The eight have also agreed to cooperate in investigations and litigation involving other parties.

The Texas physicians involved in the settlement are internist Jaspaul Bhangoo, MD, of Denton; family physician Robert Megna, DO, of Ferris; cardiologist Baxter Montgomery, MD, of Houston; internist Murtaza Mussaji, DO, of Houston; family physician David Sneed, DO, of Austin; family physician Kevin Lewis, DO, of Houston; and family physician Angela Mosley-Nunnery, MD, of Kingwood.

Also settling was Richard DeFoore, former CEO of Jones County Regional Healthcare (dba Stamford Memorial Hospital).

The physicians were accused of accepting payments from organizations in exchange for ordering lab tests from True Health Diagnostics, Little River Healthcare, and Boston Heart. The payments to the physicians were disguised as investment returns but, according to the allegations, were in fact offered in exchange for the doctors’ referrals. Mr. DeFoore, the hospital executive involved in the settlement, allegedly oversaw a similar scheme that benefited the now-defunct Stamford Memorial.

“Paying kickbacks to physicians distorts the medical decision-making process, corrupts our health care system, and increases the cost of healthcare funded by the taxpayer,” Brit Featherston, U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas, said in a statement announcing the agreement. “Laboratories, marketers, and physicians cannot immunize their conduct by attempting to disguise the kickbacks as some sort of investment arrangement.”

Practice administrative assistant sentenced for fraudulent prescriptions

An administrative assistant at an Illinois orthopedics office was sentenced to a year and a day in federal prison for writing fraudulent prescriptions for opioids.

Amanda Biesiada, 39, of Alsip, Ill., who worked as an administrative assistant at Hinsdale Orthopaedics in Westmont, Ill., was not a licensed physician and could not legally write the prescriptions unless instructed to do so and supervised by licensed doctors.

According to a statement by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois, the prescriptions for hydrocodone, oxycodone, and other controlled substances – 85 prescriptions in all from 2017 to 2019 – were made out to an acquaintance of Biesiada’s and written without the knowledge or approval of the providers in whose names she wrote them.

Federal officials said Ms. Biesiada attempted to conceal the fraudulent prescriptions by marking them “filed in error” in the practice’s prescription system.

Lab owner pleads guilty to $6.9 million testing fraud scheme

A Florida lab owner has pleaded guilty to conspiracy to defraud Medicare through false and fraudulent claims totaling more than $6.9 million.

According to court documents, Christopher Licata, 45, of Delray Beach, Fla., admitted to bribing patient brokers to refer orders for medically unnecessary genetic testing to his lab. The tests were then billed to Medicare.

Mr. Licata and the patient brokers entered sham agreements meant to disguise the true purpose of the payments, according to a statement from the Department of Justice. The 45-year-old owner of Boca Toxicology (dba Lab Dynamics) pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to commit health care fraud.

The scheme began in 2018; however, once the pandemic began, Mr. Licata shifted strategies, playing on patients’ fears of COVID-19 to bundle inexpensive COVID tests with more expensive medically unnecessary tests. These tests included respiratory pathogen panels and genetic testing for cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and other illnesses. In all, Mr. Licata’s laboratory submitted over $6.9 million in false and fraudulent claims to Medicare for these unnecessary tests, according to the DOJ statement.

The case is a part of the U.S. Attorney General’s COVID-19 Fraud Enforcement Task Force that was established to enhance the efforts of agencies and governments across the country to combat and prevent pandemic-related fraud.

Mr. Licata faces a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison. His sentencing is scheduled for March 24.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

According to court documents, between January 2014 and October 2019, family physician David Chisholm, MD, 64, of Wasilla, Alaska, wrote more than 20,000 prescriptions to approximately 350 patients for oxycodone, methadone, and hydrocodone, often prescribing the pills using variations of patients’ names in an attempt to avoid being red-flagged by payers.

When Walmart refused to continue filling the prescriptions, Dr. Chisholm told his staff to advise the patients to use other pharmacies. In addition, he often prescribed combinations of medications, such as concurrent opioids, benzodiazepines, sedatives, and carisoprodol, thus increasing the chances that his patients would become addicted to or overdose on the drugs. Chisholm, who pleaded guilty in June, acknowledged to federal officials that his prescriptions were a significant contributing factor to the overdose deaths of five of his patients during this time, according to a statement by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Alaska.

According to the Anchorage Daily News, Dr. Chisholm, who was not board certified in pain medicine, said his reason for prescribing the drugs was not to make money but to help patients suffering from chronic pain and because he enjoyed the challenge.

Dr. Chisholm’s attorney, Nick Oberheiden, told CNN his client “sacrificed his reputation as a patient advocate and his years of service to the Alaskan community” in overprescribing opioids. “He expressed his sincere remorse in open court and he accepts the consequences of his misconduct. He hopes that his case serves as a warning to other physicians facing the same dilemma when treating chronic pain.”

He surrendered his medical license in November 2020 before being formally charged in April 2021.

Texas hospital CEO, seven doctors settle kickback

A hospital executive and seven physicians have agreed to pay a total of $1.1 million to settle allegations that they violated the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law. The eight have also agreed to cooperate in investigations and litigation involving other parties.

The Texas physicians involved in the settlement are internist Jaspaul Bhangoo, MD, of Denton; family physician Robert Megna, DO, of Ferris; cardiologist Baxter Montgomery, MD, of Houston; internist Murtaza Mussaji, DO, of Houston; family physician David Sneed, DO, of Austin; family physician Kevin Lewis, DO, of Houston; and family physician Angela Mosley-Nunnery, MD, of Kingwood.

Also settling was Richard DeFoore, former CEO of Jones County Regional Healthcare (dba Stamford Memorial Hospital).

The physicians were accused of accepting payments from organizations in exchange for ordering lab tests from True Health Diagnostics, Little River Healthcare, and Boston Heart. The payments to the physicians were disguised as investment returns but, according to the allegations, were in fact offered in exchange for the doctors’ referrals. Mr. DeFoore, the hospital executive involved in the settlement, allegedly oversaw a similar scheme that benefited the now-defunct Stamford Memorial.

“Paying kickbacks to physicians distorts the medical decision-making process, corrupts our health care system, and increases the cost of healthcare funded by the taxpayer,” Brit Featherston, U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas, said in a statement announcing the agreement. “Laboratories, marketers, and physicians cannot immunize their conduct by attempting to disguise the kickbacks as some sort of investment arrangement.”

Practice administrative assistant sentenced for fraudulent prescriptions

An administrative assistant at an Illinois orthopedics office was sentenced to a year and a day in federal prison for writing fraudulent prescriptions for opioids.

Amanda Biesiada, 39, of Alsip, Ill., who worked as an administrative assistant at Hinsdale Orthopaedics in Westmont, Ill., was not a licensed physician and could not legally write the prescriptions unless instructed to do so and supervised by licensed doctors.

According to a statement by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois, the prescriptions for hydrocodone, oxycodone, and other controlled substances – 85 prescriptions in all from 2017 to 2019 – were made out to an acquaintance of Biesiada’s and written without the knowledge or approval of the providers in whose names she wrote them.

Federal officials said Ms. Biesiada attempted to conceal the fraudulent prescriptions by marking them “filed in error” in the practice’s prescription system.

Lab owner pleads guilty to $6.9 million testing fraud scheme

A Florida lab owner has pleaded guilty to conspiracy to defraud Medicare through false and fraudulent claims totaling more than $6.9 million.

According to court documents, Christopher Licata, 45, of Delray Beach, Fla., admitted to bribing patient brokers to refer orders for medically unnecessary genetic testing to his lab. The tests were then billed to Medicare.

Mr. Licata and the patient brokers entered sham agreements meant to disguise the true purpose of the payments, according to a statement from the Department of Justice. The 45-year-old owner of Boca Toxicology (dba Lab Dynamics) pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to commit health care fraud.

The scheme began in 2018; however, once the pandemic began, Mr. Licata shifted strategies, playing on patients’ fears of COVID-19 to bundle inexpensive COVID tests with more expensive medically unnecessary tests. These tests included respiratory pathogen panels and genetic testing for cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and other illnesses. In all, Mr. Licata’s laboratory submitted over $6.9 million in false and fraudulent claims to Medicare for these unnecessary tests, according to the DOJ statement.

The case is a part of the U.S. Attorney General’s COVID-19 Fraud Enforcement Task Force that was established to enhance the efforts of agencies and governments across the country to combat and prevent pandemic-related fraud.

Mr. Licata faces a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison. His sentencing is scheduled for March 24.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ketamine an ‘intriguing new therapy’ for alcoholism

Three weekly infusions of the dissociative anesthetic ketamine coupled with mindfulness-based relapse prevention therapy may help adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) maintain abstinence, new research suggests.

Preliminary results from a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial show ketamine was well tolerated and, compared with placebo, associated with more days of abstinence from alcohol at 6 months.

The results suggest ketamine plus psychological therapy may be a “new, relatively brief treatment that has long lasting effects in AUD,” Celia Morgan, PhD, professor of psychopharmacology, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, told this news organization.

The study was published online Jan. 11 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Target depression

Depressive symptoms are common in patients under treatment for AUD and increase relapse risk.

“Ketamine may support alcohol abstinence by temporarily alleviating depressive symptoms during the high-risk relapse period in the weeks after detoxification,” the investigators note.

Ketamine may also provide a “temporary boost to synaptogenesis and neurogenesis, which may allow psychological therapies and new strategies for managing addiction to embed more readily,” they add.

To test these theories, the researchers recruited 96 adults (mean age, 44 years, 35 women) with severe AUD to participate in the trial.

All participants had to abstain from alcohol for at least 24 hours before the trial started and have a reading of 0.0 on a breath alcohol test at the baseline visit.

Participants were randomly allocated to one of four groups:

1. three weekly ketamine infusions of 0.8 mg/kg IV over 40 minutes plus psychological therapy

2. three saline infusions plus psychological therapy

3. three ketamine infusions plus alcohol education

4. three saline infusions plus alcohol education

The primary outcome was self-reported percentage of days abstinent, as well as confirmed alcohol relapse at 6-month follow-up.

(mean difference, 10.1%; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-19.0), “although confidence intervals were wide, consistent with a proof-of-concept study,” the authors note.

The greatest reduction in total days off alcohol occurred in the ketamine plus relapse-prevention therapy group compared with the saline plus alcohol education group (mean difference, 15.9%; 95% CI, 3.8-28.1).

There was no significant difference in relapse rate between the ketamine and placebo groups. No serious adverse effects were reported in any participant.

Growing evidence

These findings support some other studies that have also suggested a benefit of ketamine in AUD.

As reported by this news organization, one recent study found a single infusion of ketamine combined with counseling may help alcohol-dependent patients curb their drinking.

A separate study showed that a single dose of ketamine plus therapy that focused on reactivating drinking-related “maladaptive reward memories” reduced drinking urges and alcohol intake more than just ketamine or a placebo infusion alone.

“That ketamine can reduce both alcohol use and depression in AUD is encouraging therapeutically,” the researchers write.

“While a clear link between depression and AUD is acknowledged, alcohol and mental health services still struggle to meet the needs of dual-diagnosis patients, so ketamine may represent a solution to this long-standing comorbidity,” they add.

Dr. Morgan said in an interview that adjunctive ketamine with relapse-prevention therapy is “currently being delivered in Awakn Clinics in the U.K. and Norway, but we need to conduct the phase 3 trial in order to make the treatment more widely accessible.”

An ‘Intriguing new therapy’

Reached for comment, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services, Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai, New York, said ketamine “continues to be an intriguing new therapy for a variety of mental health conditions.”

“Unfortunately, the study did not show any difference in rates of relapse to alcohol, though an improvement in days of abstinence is certainly noteworthy,” Dr. Brennan said in an interview.

“Because this was just a proof-of-concept study and did not compare ketamine to any FDA-approved pharmacotherapy for alcohol, it remains too early to recommend ketamine infusions to those suffering from alcohol use disorder,” he cautioned.

The study was supported by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Morgan has received royalties for KARE (Ketamine for Reduction of Alcoholic Relapse) therapy license distribution. KARE therapy is licensed from University of Exeter to Awakn Life Sciences. Dr. Morgan has received research funding from Awakn Life Sciences and has served as a consultant for Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Other coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry; the full list can be found with the original article. Dr. Brennan has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three weekly infusions of the dissociative anesthetic ketamine coupled with mindfulness-based relapse prevention therapy may help adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) maintain abstinence, new research suggests.

Preliminary results from a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial show ketamine was well tolerated and, compared with placebo, associated with more days of abstinence from alcohol at 6 months.

The results suggest ketamine plus psychological therapy may be a “new, relatively brief treatment that has long lasting effects in AUD,” Celia Morgan, PhD, professor of psychopharmacology, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, told this news organization.

The study was published online Jan. 11 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Target depression

Depressive symptoms are common in patients under treatment for AUD and increase relapse risk.

“Ketamine may support alcohol abstinence by temporarily alleviating depressive symptoms during the high-risk relapse period in the weeks after detoxification,” the investigators note.

Ketamine may also provide a “temporary boost to synaptogenesis and neurogenesis, which may allow psychological therapies and new strategies for managing addiction to embed more readily,” they add.

To test these theories, the researchers recruited 96 adults (mean age, 44 years, 35 women) with severe AUD to participate in the trial.

All participants had to abstain from alcohol for at least 24 hours before the trial started and have a reading of 0.0 on a breath alcohol test at the baseline visit.

Participants were randomly allocated to one of four groups:

1. three weekly ketamine infusions of 0.8 mg/kg IV over 40 minutes plus psychological therapy

2. three saline infusions plus psychological therapy

3. three ketamine infusions plus alcohol education

4. three saline infusions plus alcohol education

The primary outcome was self-reported percentage of days abstinent, as well as confirmed alcohol relapse at 6-month follow-up.

(mean difference, 10.1%; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-19.0), “although confidence intervals were wide, consistent with a proof-of-concept study,” the authors note.

The greatest reduction in total days off alcohol occurred in the ketamine plus relapse-prevention therapy group compared with the saline plus alcohol education group (mean difference, 15.9%; 95% CI, 3.8-28.1).

There was no significant difference in relapse rate between the ketamine and placebo groups. No serious adverse effects were reported in any participant.

Growing evidence

These findings support some other studies that have also suggested a benefit of ketamine in AUD.

As reported by this news organization, one recent study found a single infusion of ketamine combined with counseling may help alcohol-dependent patients curb their drinking.

A separate study showed that a single dose of ketamine plus therapy that focused on reactivating drinking-related “maladaptive reward memories” reduced drinking urges and alcohol intake more than just ketamine or a placebo infusion alone.

“That ketamine can reduce both alcohol use and depression in AUD is encouraging therapeutically,” the researchers write.

“While a clear link between depression and AUD is acknowledged, alcohol and mental health services still struggle to meet the needs of dual-diagnosis patients, so ketamine may represent a solution to this long-standing comorbidity,” they add.

Dr. Morgan said in an interview that adjunctive ketamine with relapse-prevention therapy is “currently being delivered in Awakn Clinics in the U.K. and Norway, but we need to conduct the phase 3 trial in order to make the treatment more widely accessible.”

An ‘Intriguing new therapy’

Reached for comment, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services, Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai, New York, said ketamine “continues to be an intriguing new therapy for a variety of mental health conditions.”

“Unfortunately, the study did not show any difference in rates of relapse to alcohol, though an improvement in days of abstinence is certainly noteworthy,” Dr. Brennan said in an interview.

“Because this was just a proof-of-concept study and did not compare ketamine to any FDA-approved pharmacotherapy for alcohol, it remains too early to recommend ketamine infusions to those suffering from alcohol use disorder,” he cautioned.

The study was supported by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Morgan has received royalties for KARE (Ketamine for Reduction of Alcoholic Relapse) therapy license distribution. KARE therapy is licensed from University of Exeter to Awakn Life Sciences. Dr. Morgan has received research funding from Awakn Life Sciences and has served as a consultant for Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Other coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry; the full list can be found with the original article. Dr. Brennan has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three weekly infusions of the dissociative anesthetic ketamine coupled with mindfulness-based relapse prevention therapy may help adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) maintain abstinence, new research suggests.

Preliminary results from a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial show ketamine was well tolerated and, compared with placebo, associated with more days of abstinence from alcohol at 6 months.

The results suggest ketamine plus psychological therapy may be a “new, relatively brief treatment that has long lasting effects in AUD,” Celia Morgan, PhD, professor of psychopharmacology, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, told this news organization.

The study was published online Jan. 11 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Target depression

Depressive symptoms are common in patients under treatment for AUD and increase relapse risk.

“Ketamine may support alcohol abstinence by temporarily alleviating depressive symptoms during the high-risk relapse period in the weeks after detoxification,” the investigators note.

Ketamine may also provide a “temporary boost to synaptogenesis and neurogenesis, which may allow psychological therapies and new strategies for managing addiction to embed more readily,” they add.

To test these theories, the researchers recruited 96 adults (mean age, 44 years, 35 women) with severe AUD to participate in the trial.

All participants had to abstain from alcohol for at least 24 hours before the trial started and have a reading of 0.0 on a breath alcohol test at the baseline visit.

Participants were randomly allocated to one of four groups:

1. three weekly ketamine infusions of 0.8 mg/kg IV over 40 minutes plus psychological therapy

2. three saline infusions plus psychological therapy

3. three ketamine infusions plus alcohol education

4. three saline infusions plus alcohol education

The primary outcome was self-reported percentage of days abstinent, as well as confirmed alcohol relapse at 6-month follow-up.

(mean difference, 10.1%; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-19.0), “although confidence intervals were wide, consistent with a proof-of-concept study,” the authors note.

The greatest reduction in total days off alcohol occurred in the ketamine plus relapse-prevention therapy group compared with the saline plus alcohol education group (mean difference, 15.9%; 95% CI, 3.8-28.1).

There was no significant difference in relapse rate between the ketamine and placebo groups. No serious adverse effects were reported in any participant.

Growing evidence

These findings support some other studies that have also suggested a benefit of ketamine in AUD.

As reported by this news organization, one recent study found a single infusion of ketamine combined with counseling may help alcohol-dependent patients curb their drinking.

A separate study showed that a single dose of ketamine plus therapy that focused on reactivating drinking-related “maladaptive reward memories” reduced drinking urges and alcohol intake more than just ketamine or a placebo infusion alone.

“That ketamine can reduce both alcohol use and depression in AUD is encouraging therapeutically,” the researchers write.

“While a clear link between depression and AUD is acknowledged, alcohol and mental health services still struggle to meet the needs of dual-diagnosis patients, so ketamine may represent a solution to this long-standing comorbidity,” they add.

Dr. Morgan said in an interview that adjunctive ketamine with relapse-prevention therapy is “currently being delivered in Awakn Clinics in the U.K. and Norway, but we need to conduct the phase 3 trial in order to make the treatment more widely accessible.”

An ‘Intriguing new therapy’

Reached for comment, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services, Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai, New York, said ketamine “continues to be an intriguing new therapy for a variety of mental health conditions.”

“Unfortunately, the study did not show any difference in rates of relapse to alcohol, though an improvement in days of abstinence is certainly noteworthy,” Dr. Brennan said in an interview.

“Because this was just a proof-of-concept study and did not compare ketamine to any FDA-approved pharmacotherapy for alcohol, it remains too early to recommend ketamine infusions to those suffering from alcohol use disorder,” he cautioned.

The study was supported by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Morgan has received royalties for KARE (Ketamine for Reduction of Alcoholic Relapse) therapy license distribution. KARE therapy is licensed from University of Exeter to Awakn Life Sciences. Dr. Morgan has received research funding from Awakn Life Sciences and has served as a consultant for Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Other coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry; the full list can be found with the original article. Dr. Brennan has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How to screen for and treat teen alcohol use

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

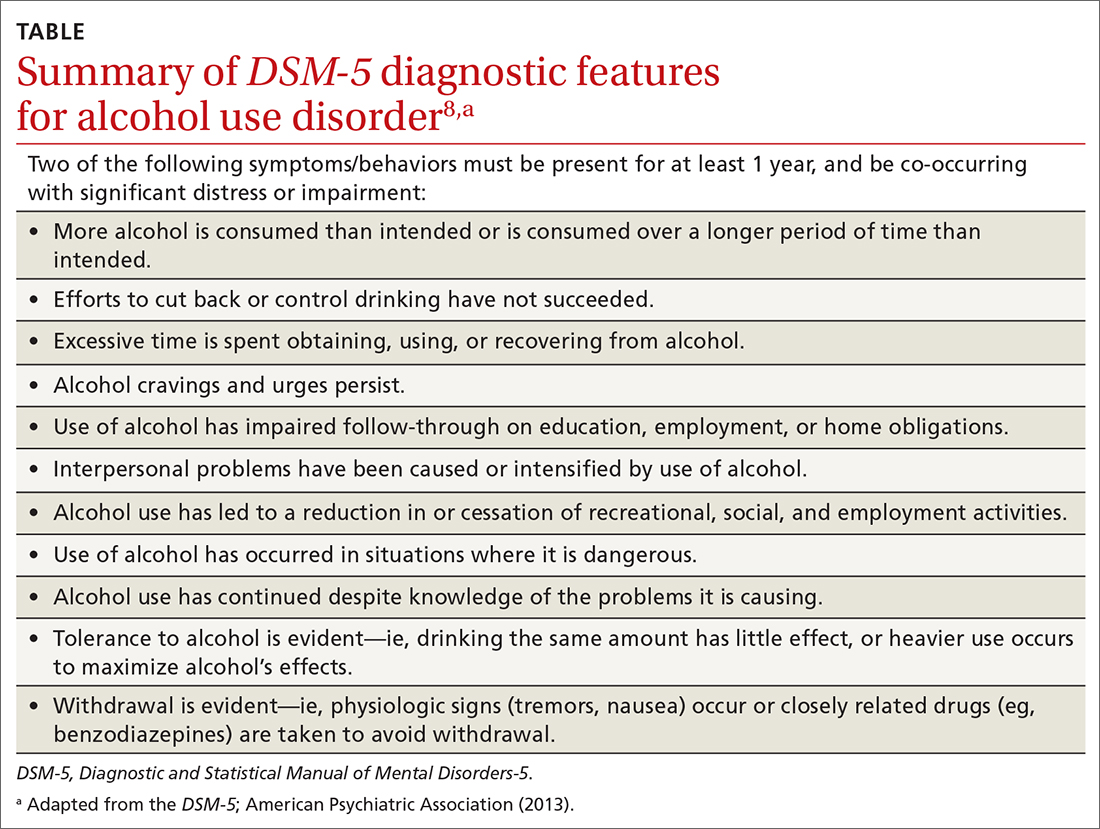

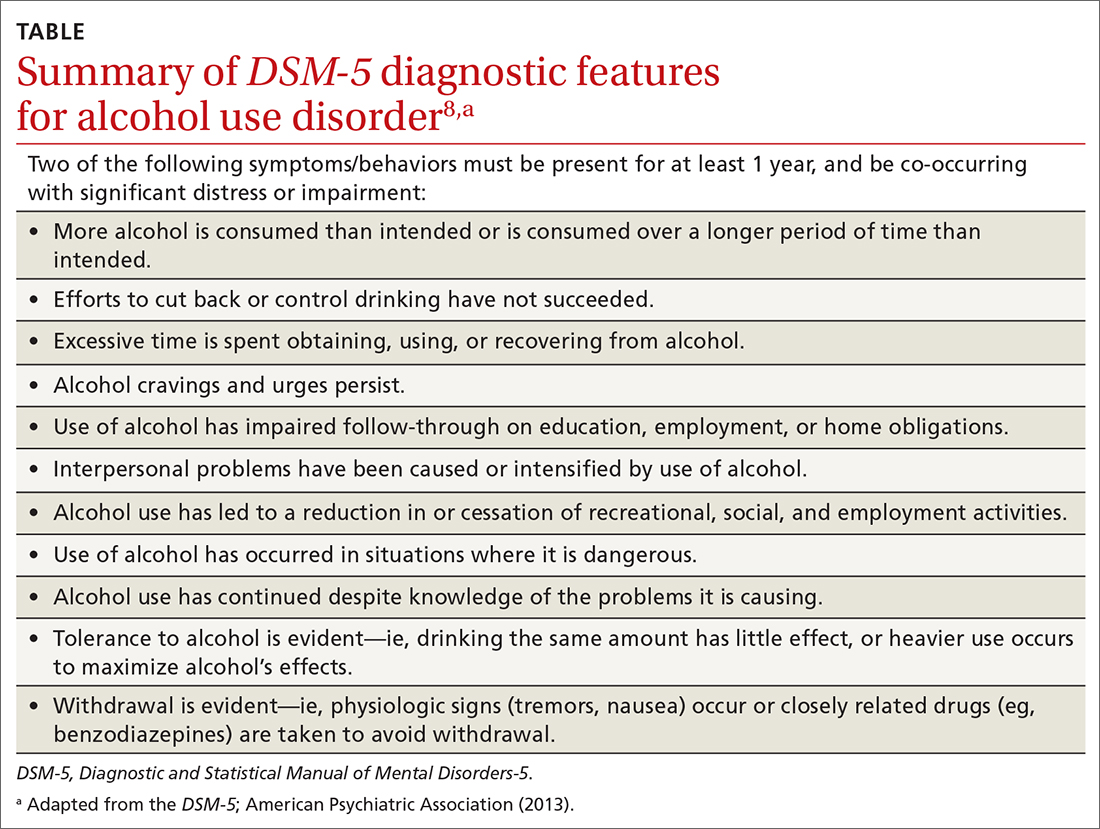

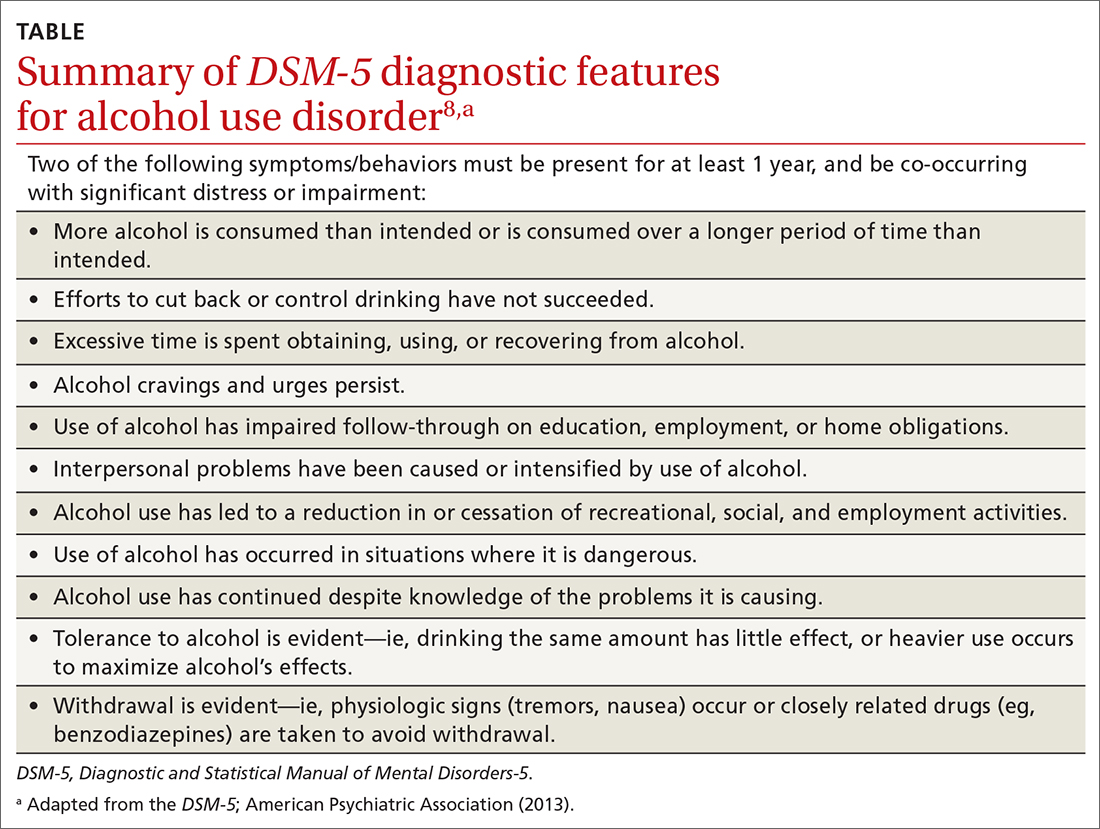

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; [email protected]

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; [email protected]

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; [email protected]

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

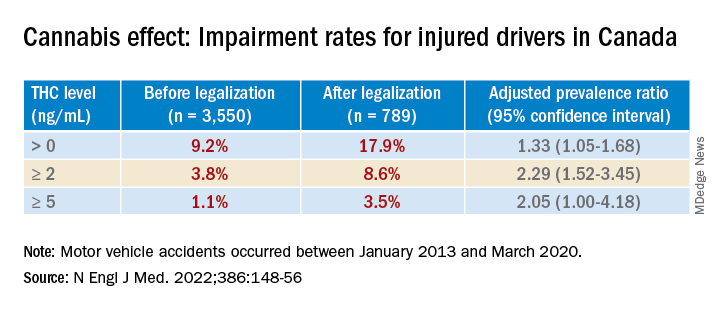

Dramatic increase in driving high after cannabis legislation

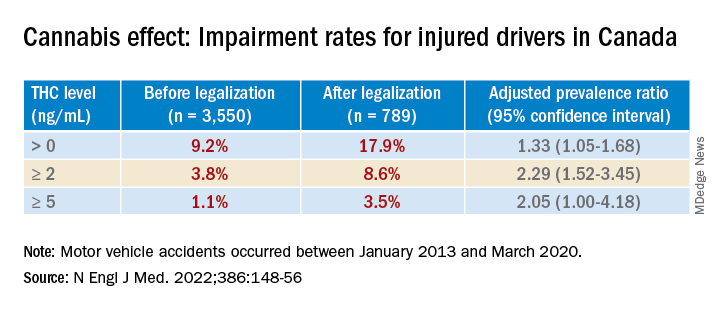

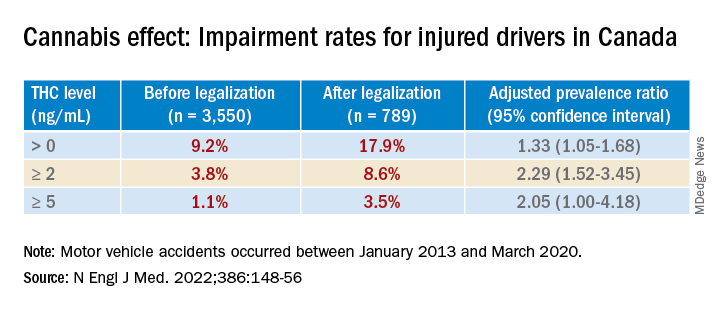

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.