User login

Simultaneous marijuana, alcohol use linked to worse outcomes

TOPLINE:

Young adults who simultaneously use alcohol and marijuana (SAM) consume more drinks, are high for more hours in the day, and report more negative alcohol-related consequences.

METHODOLOGY:

- The 2-year study included 409 people aged 18-25 years with a history of simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (50.9% were women; 48.2% were non-Hispanic White; 48.9% were college students).

- Participants completed daily online surveys about substance use and negative substance-related consequences for 14 continuous days every 4 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alcohol use was reported on 36.1% of survey days, marijuana use on 28.0%, and alcohol and marijuana use on 15.0%.

- Negative substance-related consequences were reported on 28.0% of drinking days and 56.4% of marijuana days.

- SAM use was reported in 81.7% of alcohol users and 86.6% of marijuana users.

- On SAM use days, participants consumed an average of 37% more drinks, with 43% more negative alcohol consequences; were high for 10% more hours; and were more likely to feel clumsy or dizzy, compared with non-SAM use days.

IN PRACTICE:

“This finding should be integrated into psychoeducational programs highlighting the risk of combining alcohol and marijuana,” the authors write. “A more nuanced harm-reduction [approach] could also encourage young adults to closely monitor and limit the amount of each substance being used if they choose to combine substances.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Anne M. Fairlie, PhD, University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues, and funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The study was published online in Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Study participants were recruited based on their substance use and lived in a region where recreational marijuana is legal, so the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Substance use and consequences were self-reported and subject to bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Young adults who simultaneously use alcohol and marijuana (SAM) consume more drinks, are high for more hours in the day, and report more negative alcohol-related consequences.

METHODOLOGY:

- The 2-year study included 409 people aged 18-25 years with a history of simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (50.9% were women; 48.2% were non-Hispanic White; 48.9% were college students).

- Participants completed daily online surveys about substance use and negative substance-related consequences for 14 continuous days every 4 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alcohol use was reported on 36.1% of survey days, marijuana use on 28.0%, and alcohol and marijuana use on 15.0%.

- Negative substance-related consequences were reported on 28.0% of drinking days and 56.4% of marijuana days.

- SAM use was reported in 81.7% of alcohol users and 86.6% of marijuana users.

- On SAM use days, participants consumed an average of 37% more drinks, with 43% more negative alcohol consequences; were high for 10% more hours; and were more likely to feel clumsy or dizzy, compared with non-SAM use days.

IN PRACTICE:

“This finding should be integrated into psychoeducational programs highlighting the risk of combining alcohol and marijuana,” the authors write. “A more nuanced harm-reduction [approach] could also encourage young adults to closely monitor and limit the amount of each substance being used if they choose to combine substances.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Anne M. Fairlie, PhD, University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues, and funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The study was published online in Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Study participants were recruited based on their substance use and lived in a region where recreational marijuana is legal, so the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Substance use and consequences were self-reported and subject to bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Young adults who simultaneously use alcohol and marijuana (SAM) consume more drinks, are high for more hours in the day, and report more negative alcohol-related consequences.

METHODOLOGY:

- The 2-year study included 409 people aged 18-25 years with a history of simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (50.9% were women; 48.2% were non-Hispanic White; 48.9% were college students).

- Participants completed daily online surveys about substance use and negative substance-related consequences for 14 continuous days every 4 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alcohol use was reported on 36.1% of survey days, marijuana use on 28.0%, and alcohol and marijuana use on 15.0%.

- Negative substance-related consequences were reported on 28.0% of drinking days and 56.4% of marijuana days.

- SAM use was reported in 81.7% of alcohol users and 86.6% of marijuana users.

- On SAM use days, participants consumed an average of 37% more drinks, with 43% more negative alcohol consequences; were high for 10% more hours; and were more likely to feel clumsy or dizzy, compared with non-SAM use days.

IN PRACTICE:

“This finding should be integrated into psychoeducational programs highlighting the risk of combining alcohol and marijuana,” the authors write. “A more nuanced harm-reduction [approach] could also encourage young adults to closely monitor and limit the amount of each substance being used if they choose to combine substances.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Anne M. Fairlie, PhD, University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues, and funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The study was published online in Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Study participants were recruited based on their substance use and lived in a region where recreational marijuana is legal, so the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Substance use and consequences were self-reported and subject to bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. counties hit hard by a lack of psychiatric care

TOPLINE:

, new research shows.

METHODOLOGY:

- In the United States, there is a severe lack of psychiatrists and access to mental health care. In 2019, 21.3 million U.S. residents were without broadband access. These patients were forced either to use telephone consultation or to not use telehealth services at all, although use of telehealth during COVID-19 somewhat improved access to psychiatric care.

- For the study, researchers gathered sociodemographic and other county-level information from the American Community Survey. They also used data on the psychiatrist workforce from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Area Health Resources Files.

- Information on broadband Internet coverage came from the Federal Communications Commission, and measures of mental health outcomes were from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study identified 596 counties (19% of all U.S. counties) that were without psychiatrists and in which there was inadequate broadband coverage. The population represented 10.5 million residents.

- Compared with other counties, those with lack of coverage were more likely to be rural (adjusted odds ratio, 3.05; 95% confidence interval, 2.41-3.84), to have higher unemployment (aOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24), and to have higher uninsurance rates (aOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00-1.06). In those counties, there were also fewer residents with a bachelor’s degree (aOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.90-0.94) and fewer Hispanics (aOR 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97-0.99), although those counties were not designated by the HRSA as having a psychiatrist shortage. That designation brings additional funding for the recruitment of clinicians.

- After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, counties without psychiatrists and broadband had significantly higher rates of adult depression, frequent mental distress, drug overdose mortality, and completed suicide, compared with other counties.

- Further analysis showed that the adjusted difference remained statistically significant for drug overdose mortality per 100,000 (9.2; 95% CI, 8.0-10.5, vs. 5.2; 95% CI, 4.9-5.6; P < .001) and completed suicide (10.6; 95% CI, 8.9-12.3, vs. 7.6; 95% CI, 7.0-8.2; P < .001), but not for the other two measures.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our finding suggests that lacking access to virtual and in-person psychiatric care continues to be a key factor associated with adverse outcomes,” the investigators write. They note that federal and state-level investments in broadband and the psychiatric workforce are needed.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Tarun Ramesh, BS, department of population medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, and colleagues. It was published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators did not consider whether recent legislation, including the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and the American Rescue Plan, which expanded psychiatry residency slots and broadband infrastructure, reduces adverse outcomes, something the authors say future research should examine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new research shows.

METHODOLOGY:

- In the United States, there is a severe lack of psychiatrists and access to mental health care. In 2019, 21.3 million U.S. residents were without broadband access. These patients were forced either to use telephone consultation or to not use telehealth services at all, although use of telehealth during COVID-19 somewhat improved access to psychiatric care.

- For the study, researchers gathered sociodemographic and other county-level information from the American Community Survey. They also used data on the psychiatrist workforce from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Area Health Resources Files.

- Information on broadband Internet coverage came from the Federal Communications Commission, and measures of mental health outcomes were from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study identified 596 counties (19% of all U.S. counties) that were without psychiatrists and in which there was inadequate broadband coverage. The population represented 10.5 million residents.

- Compared with other counties, those with lack of coverage were more likely to be rural (adjusted odds ratio, 3.05; 95% confidence interval, 2.41-3.84), to have higher unemployment (aOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24), and to have higher uninsurance rates (aOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00-1.06). In those counties, there were also fewer residents with a bachelor’s degree (aOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.90-0.94) and fewer Hispanics (aOR 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97-0.99), although those counties were not designated by the HRSA as having a psychiatrist shortage. That designation brings additional funding for the recruitment of clinicians.

- After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, counties without psychiatrists and broadband had significantly higher rates of adult depression, frequent mental distress, drug overdose mortality, and completed suicide, compared with other counties.

- Further analysis showed that the adjusted difference remained statistically significant for drug overdose mortality per 100,000 (9.2; 95% CI, 8.0-10.5, vs. 5.2; 95% CI, 4.9-5.6; P < .001) and completed suicide (10.6; 95% CI, 8.9-12.3, vs. 7.6; 95% CI, 7.0-8.2; P < .001), but not for the other two measures.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our finding suggests that lacking access to virtual and in-person psychiatric care continues to be a key factor associated with adverse outcomes,” the investigators write. They note that federal and state-level investments in broadband and the psychiatric workforce are needed.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Tarun Ramesh, BS, department of population medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, and colleagues. It was published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators did not consider whether recent legislation, including the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and the American Rescue Plan, which expanded psychiatry residency slots and broadband infrastructure, reduces adverse outcomes, something the authors say future research should examine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new research shows.

METHODOLOGY:

- In the United States, there is a severe lack of psychiatrists and access to mental health care. In 2019, 21.3 million U.S. residents were without broadband access. These patients were forced either to use telephone consultation or to not use telehealth services at all, although use of telehealth during COVID-19 somewhat improved access to psychiatric care.

- For the study, researchers gathered sociodemographic and other county-level information from the American Community Survey. They also used data on the psychiatrist workforce from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Area Health Resources Files.

- Information on broadband Internet coverage came from the Federal Communications Commission, and measures of mental health outcomes were from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study identified 596 counties (19% of all U.S. counties) that were without psychiatrists and in which there was inadequate broadband coverage. The population represented 10.5 million residents.

- Compared with other counties, those with lack of coverage were more likely to be rural (adjusted odds ratio, 3.05; 95% confidence interval, 2.41-3.84), to have higher unemployment (aOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24), and to have higher uninsurance rates (aOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00-1.06). In those counties, there were also fewer residents with a bachelor’s degree (aOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.90-0.94) and fewer Hispanics (aOR 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97-0.99), although those counties were not designated by the HRSA as having a psychiatrist shortage. That designation brings additional funding for the recruitment of clinicians.

- After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, counties without psychiatrists and broadband had significantly higher rates of adult depression, frequent mental distress, drug overdose mortality, and completed suicide, compared with other counties.

- Further analysis showed that the adjusted difference remained statistically significant for drug overdose mortality per 100,000 (9.2; 95% CI, 8.0-10.5, vs. 5.2; 95% CI, 4.9-5.6; P < .001) and completed suicide (10.6; 95% CI, 8.9-12.3, vs. 7.6; 95% CI, 7.0-8.2; P < .001), but not for the other two measures.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our finding suggests that lacking access to virtual and in-person psychiatric care continues to be a key factor associated with adverse outcomes,” the investigators write. They note that federal and state-level investments in broadband and the psychiatric workforce are needed.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Tarun Ramesh, BS, department of population medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, and colleagues. It was published online as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators did not consider whether recent legislation, including the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and the American Rescue Plan, which expanded psychiatry residency slots and broadband infrastructure, reduces adverse outcomes, something the authors say future research should examine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Supplements Are Not a Synonym for Safe: Suspected Liver Injury From Ashwagandha

Many patients take herbals as alternative supplements to boost energy and mood. There are increasing reports of unintended adverse effects related to these supplements, particularly to the liver.1-3 A study by the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network found that liver injury caused by herbals and dietary supplements has increased from 7% in 2004 to 20% in 2013.4

The supplement ashwagandha has become increasingly popular. Ashwagandha is extracted from the root of Withania somnifera (

To date, the factors defining the population at risk for ashwagandha toxicity are unclear, and an understanding of how to diagnose drug-induced liver injury is still immature in clinical practice. The regulation and study of the herbal and dietary supplement industry remain challenging. While many so-called natural substances are well tolerated, others can have unanticipated and harmful adverse effects and drug interactions. Future research should not only identify potentially harmful substances, but also which patients may be at greatest risk.

Case Presentation

A 48-year-old man with a history of severe alcohol use disorder (AUD) complicated by fatty liver and withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens, hypertension, depression, and anxiety presented to the emergency department (ED) after 4 days of having jaundice, epigastric abdominal pain, dark urine, and pale stools. In the preceding months, he had increased his alcohol use to as many as 12 drinks daily due to depression. After experiencing a blackout, he stopped drinking 7 days before presenting to the ED. He felt withdrawal symptoms, including tremors, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. On the third day of withdrawals, he reported that he had started taking an over-the-counter testosterone-boosting supplement to increase his energy, which he referred to as TestBoost—a mix of 8 ingredients, including ashwagandha, eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry, longjack, ginseng root, mushroom extract, bindii, and horny goat weed. After taking the supplement for 2 days, he noticed that his urine darkened, his stools became paler, his abdominal pain worsened, and he became jaundiced. After 2 additional days without improvement, and still taking the supplement, he presented to the ED. He reported having no fever, chills, recent illness, chest pain, shortness of breath, melena, lower extremity swelling, recent travel, or any changes in medications.

The patient had a 100.1 °F temperature, 102 beats per minute pulse; 129/94 mm Hg blood pressure, 18 beats per minute respiratory rate, and 97% oxygen saturation on room air on admission. He was in no acute distress, though his examination was notable for generalized jaundice and scleral icterus. He was mildly tender to palpation in the epigastric and right upper quadrant region. He was alert and oriented without confusion. He did not have any asterixis or spider angiomas, though he had scattered bruises on his left flank and left calf. His laboratory results were notable for mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 58 U/L (reference range, 13-35); alanine transaminase (ALT), 49 U/L (reference range, 7-45); and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 98 U/L (reference range 33-94); total bilirubin, 13.6 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.0); direct bilirubin, 8.4 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1); and international normalized ratio (INR), 1.11 (reference range, 2-3). His white blood cell and platelet counts were not remarkable at 9790/μL (reference range, 4500-11,000) and 337,000/μL (reference range, 150,000-440,000), respectively. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) revealed fatty liver with contracted gallbladder and no biliary dilatation. Urine ethanol levels were negative. The gastrointestinal (GI) service was consulted and agreed that his cholestatic injury was nonobstructive and likely related to the ashwagandha component of his supplement. The recommendation was cessation with close outpatient follow-up.

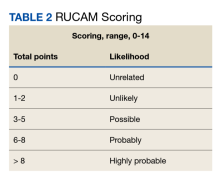

The patient was not prescribed any additional medications, such as steroids or ursodiol. He ceased supplement use following hospitalization; but relapsed into alcohol use 1 month after his discharge. Within 3 weeks, his total bilirubin had improved to 2.87 mg/dL, though AST, ALT, and ALP worsened to 127 U/L, 152 U/L, and 140 U/L, respectively. According to the notes of his psychiatrist who saw him at the time the laboratory tests were drawn, he had remained sober since discharge. His acute hepatitis panel drawn on admission was negative, and he demonstrated immunity to hepatitis A and B. Urine toxicology was negative. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was negative 1 year prior to discharge. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), ANA, antismooth muscle antibody, and immunoglobulins were not checked as suspicion for these etiologies was low. The Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) score was calculated as 6 (+1 for timing, +2 for drop in total bilirubin, +1 for ethanol risk factor, 0 for no other drugs, 0 for rule out of other diseases, +2 for known hepatotoxicity, 0 no repeat administration) for this patient indicating probable adverse drug reaction liver injury (Tables 1 and 2). However, we acknowledge that CMV, EBV, and herpes simplex virus status were not tested.

The 8 ingredients contained in TestBoost aside from ashwagandha did not have any major known liver adverse effects per a major database of medications. The other ingredients include eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry (crataegus laevigata), longjack (eurycoma longifolla) root, American ginseng root (American panax ginseng—panax quinquefolius), and Cordyceps mycelium (mushroom) extract, bindii (Tribulus terrestris), and epimedium grandiflorum (horny goat weed).6 No assays were performed to confirm purity of the ingredients in the patient’s supplement container.

Alcoholic hepatitis is an important consideration in this patient with AUD, though the timing of symptoms with supplement use and the cholestatic injury pattern with normal INR seems more consistent with drug-induced injury. Viral, infectious, and obstructive etiologies also were investigated. Acute viral hepatitis was ruled out based on bloodwork. The normal hepatobiliary tree on both ultrasound and CT effectively ruled out acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, and choledocholithiasis and there was no further indication for magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. There was no hepatic vein clot suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Autoimmune hepatitis was thought to be unlikely given that the etiology of injury seemed cholestatic in nature. Given the timing of the liver injury relative to supplement use it is likely that ashwagandha was a causative factor of this patient’s liver injury overlaid on an already strained liver from increased alcohol abuse.

The patient did not follow up with the GI service as an outpatient. There are no reports that the patient continued using the testosterone booster. His bilirubin improved dramatically within 1.5 months while his liver enzymes peaked 3 weeks later, with ALT ≥ AST. During his next admission 3 months later, he had relapsed, and his liver enzymes had the classic 2:1 AST to ALT ratio.

Discussion

Generally, ashwagandha has been thought to be well tolerated and possibly hepatoprotective.7-10 However, recent studies suggest potential for hepatotoxicity, though without clear guidance about which patients are most at risk.5,11,12 A study by Inagaki and colleagues suggests the potential for dose-dependent mechanism of liver injury, and this is supported by in vitro CYP450 inhibition with high doses of W Somnifera extract.11,13 We hypothesize that there may be a multihit process that makes some patients more susceptible to supplement harm, particularly those with repeated exposures and with ongoing exposure to hepatic toxins, such as AUD.14 Supplements should be used with more caution in these individuals.

Additionally, although there are no validated guidelines to confirm the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) from a manufactured medication or herbal remedy, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) developed RUCAM, a set of diagnostic criteria for DILI, which can be used to determine the probability of DILI based on pattern of injury.15 Although not widely used in clinical practice, RUCAM can help identify the possibility of DILI outside of expert consensus.16 It seems to have better discriminative ability than the Maria and Victorino scale, also used to identify DILI.16,17 While there is no replacement for clinical judgment, these scales may aid in identifying potential causes of DILI. The National Institutes of Health also has a LiverTox online tool that can assist health care professionals in identifying potentially hepatotoxic substances.6

Conclusions

We present a patient with AUD who developed cholestatic liver injury after ashwagandha use. Crucial to the diagnostic process is quantifying the amount ingested before presentation and the presence of contaminants, which is currently difficult to quantify given the lack of mechanisms to test supplements expediently in this manner in the clinical setting, which also requires the patient to bring in the supplements directly. There is also a lack of regulation and uniformity in these products. A clinician may be inclined to measure ashwagandha serum levels; however, such a test is not available to our knowledge. Nonetheless, using clinical tools such as RUCAM and utilizing databases, such as LiverTox, may help clinicians identify and remove potentially unsafe supplements. While there are many possible synergies between current medical practice and herbal remedies, practitioners must take care to first do no harm, as outlined in our Hippocratic Oath.

1. Navarro VJ. Herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29(4):373-382. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1240006

2. Suk KT, Kim DJ, Kim CH, et al. A prospective nationwide study of drug-induced liver injury in Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1380-1387. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.138

3. Shen T, Liu Y, Shang J, et al. Incidence and etiology of drug-induced liver injury in mainland China. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(8):2230-2241.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.002

4. Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology. 2014;60(4):1399-1408. doi:10.1002/hep.27317

5. Björnsson HK, Björnsson, Avula B, et al. (2020). Ashwagandha‐induced liver injury: a case series from Iceland and the US Drug‐Induced Liver Injury Network. Liver Int. 2020;40(4):825-829. doi:10.1111/liv.14393

6. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury [internet]. Ashwagandha. Updated May 2, 2019. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548536

7. Kumar G, Srivastava A, Sharma SK, Rao TD, Gupta YK. Efficacy and safety evaluation of Ayurvedic treatment (ashwagandha powder & Sidh Makardhwaj) in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a pilot prospective study. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141(1):100-106. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.154510

8. Kumar G, Srivastava A, Sharma SK, Gupta YK. Safety and efficacy evaluation of Ayurvedic treatment (arjuna powder and Arogyavardhini Vati) in dyslipidemia patients: a pilot prospective cohort clinical study. 2012;33(2):197-201. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.105238

9. Sultana N, Shimmi S, Parash MT, Akhtar J. Effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) root extract on some serum liver marker enzymes (AST, ALT) in gentamicin intoxicated rats. J Bangladesh Soc Physiologist. 2012;7(1): 1-7. doi:10.3329/JBSP.V7I1.11152

10. Patel DP, Yan T, Kim D, et al. Withaferin A improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371(2):360-374. doi:10.1124/jpet.119.256792

11. Inagaki K, Mori N, Honda Y, Takaki S, Tsuji K, Chayama K. A case of drug-induced liver injury with prolonged severe intrahepatic cholestasis induced by ashwagandha. Kanzo. 2017;58(8):448-454. doi:10.2957/kanzo.58.448

12. Alali F, Hermez K, Ullah N. Acute hepatitis induced by a unique combination of herbal supplements. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1661.

13. Sava J, Varghese A, Pandita N. Lack of the cytochrome P450 3A interaction of methanolic extract of Withania somnifera, Withaferin A, Withanolide A and Withanoside IV. J Pharm Negative Results. 2013;4(1):26.

14. Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):474-485. doi:10.1056/NEJMra021844.

15. Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs-I. A novel method based on the conclusions of International Consensus Meeting: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323–1333. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(93)90101-6

16. Hayashi PH. Causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29(4):348-356. doi.10.1002/cld.615

17. Lucena MI, Camargo R, Andrade RJ, Perez-Sanchez CJ, Sanchez De La Cuesta F. Comparison of two clinical scales for causality assessment in hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):123-130. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.20645

Many patients take herbals as alternative supplements to boost energy and mood. There are increasing reports of unintended adverse effects related to these supplements, particularly to the liver.1-3 A study by the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network found that liver injury caused by herbals and dietary supplements has increased from 7% in 2004 to 20% in 2013.4

The supplement ashwagandha has become increasingly popular. Ashwagandha is extracted from the root of Withania somnifera (

To date, the factors defining the population at risk for ashwagandha toxicity are unclear, and an understanding of how to diagnose drug-induced liver injury is still immature in clinical practice. The regulation and study of the herbal and dietary supplement industry remain challenging. While many so-called natural substances are well tolerated, others can have unanticipated and harmful adverse effects and drug interactions. Future research should not only identify potentially harmful substances, but also which patients may be at greatest risk.

Case Presentation

A 48-year-old man with a history of severe alcohol use disorder (AUD) complicated by fatty liver and withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens, hypertension, depression, and anxiety presented to the emergency department (ED) after 4 days of having jaundice, epigastric abdominal pain, dark urine, and pale stools. In the preceding months, he had increased his alcohol use to as many as 12 drinks daily due to depression. After experiencing a blackout, he stopped drinking 7 days before presenting to the ED. He felt withdrawal symptoms, including tremors, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. On the third day of withdrawals, he reported that he had started taking an over-the-counter testosterone-boosting supplement to increase his energy, which he referred to as TestBoost—a mix of 8 ingredients, including ashwagandha, eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry, longjack, ginseng root, mushroom extract, bindii, and horny goat weed. After taking the supplement for 2 days, he noticed that his urine darkened, his stools became paler, his abdominal pain worsened, and he became jaundiced. After 2 additional days without improvement, and still taking the supplement, he presented to the ED. He reported having no fever, chills, recent illness, chest pain, shortness of breath, melena, lower extremity swelling, recent travel, or any changes in medications.

The patient had a 100.1 °F temperature, 102 beats per minute pulse; 129/94 mm Hg blood pressure, 18 beats per minute respiratory rate, and 97% oxygen saturation on room air on admission. He was in no acute distress, though his examination was notable for generalized jaundice and scleral icterus. He was mildly tender to palpation in the epigastric and right upper quadrant region. He was alert and oriented without confusion. He did not have any asterixis or spider angiomas, though he had scattered bruises on his left flank and left calf. His laboratory results were notable for mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 58 U/L (reference range, 13-35); alanine transaminase (ALT), 49 U/L (reference range, 7-45); and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 98 U/L (reference range 33-94); total bilirubin, 13.6 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.0); direct bilirubin, 8.4 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1); and international normalized ratio (INR), 1.11 (reference range, 2-3). His white blood cell and platelet counts were not remarkable at 9790/μL (reference range, 4500-11,000) and 337,000/μL (reference range, 150,000-440,000), respectively. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) revealed fatty liver with contracted gallbladder and no biliary dilatation. Urine ethanol levels were negative. The gastrointestinal (GI) service was consulted and agreed that his cholestatic injury was nonobstructive and likely related to the ashwagandha component of his supplement. The recommendation was cessation with close outpatient follow-up.

The patient was not prescribed any additional medications, such as steroids or ursodiol. He ceased supplement use following hospitalization; but relapsed into alcohol use 1 month after his discharge. Within 3 weeks, his total bilirubin had improved to 2.87 mg/dL, though AST, ALT, and ALP worsened to 127 U/L, 152 U/L, and 140 U/L, respectively. According to the notes of his psychiatrist who saw him at the time the laboratory tests were drawn, he had remained sober since discharge. His acute hepatitis panel drawn on admission was negative, and he demonstrated immunity to hepatitis A and B. Urine toxicology was negative. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was negative 1 year prior to discharge. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), ANA, antismooth muscle antibody, and immunoglobulins were not checked as suspicion for these etiologies was low. The Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) score was calculated as 6 (+1 for timing, +2 for drop in total bilirubin, +1 for ethanol risk factor, 0 for no other drugs, 0 for rule out of other diseases, +2 for known hepatotoxicity, 0 no repeat administration) for this patient indicating probable adverse drug reaction liver injury (Tables 1 and 2). However, we acknowledge that CMV, EBV, and herpes simplex virus status were not tested.

The 8 ingredients contained in TestBoost aside from ashwagandha did not have any major known liver adverse effects per a major database of medications. The other ingredients include eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry (crataegus laevigata), longjack (eurycoma longifolla) root, American ginseng root (American panax ginseng—panax quinquefolius), and Cordyceps mycelium (mushroom) extract, bindii (Tribulus terrestris), and epimedium grandiflorum (horny goat weed).6 No assays were performed to confirm purity of the ingredients in the patient’s supplement container.

Alcoholic hepatitis is an important consideration in this patient with AUD, though the timing of symptoms with supplement use and the cholestatic injury pattern with normal INR seems more consistent with drug-induced injury. Viral, infectious, and obstructive etiologies also were investigated. Acute viral hepatitis was ruled out based on bloodwork. The normal hepatobiliary tree on both ultrasound and CT effectively ruled out acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, and choledocholithiasis and there was no further indication for magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. There was no hepatic vein clot suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Autoimmune hepatitis was thought to be unlikely given that the etiology of injury seemed cholestatic in nature. Given the timing of the liver injury relative to supplement use it is likely that ashwagandha was a causative factor of this patient’s liver injury overlaid on an already strained liver from increased alcohol abuse.

The patient did not follow up with the GI service as an outpatient. There are no reports that the patient continued using the testosterone booster. His bilirubin improved dramatically within 1.5 months while his liver enzymes peaked 3 weeks later, with ALT ≥ AST. During his next admission 3 months later, he had relapsed, and his liver enzymes had the classic 2:1 AST to ALT ratio.

Discussion

Generally, ashwagandha has been thought to be well tolerated and possibly hepatoprotective.7-10 However, recent studies suggest potential for hepatotoxicity, though without clear guidance about which patients are most at risk.5,11,12 A study by Inagaki and colleagues suggests the potential for dose-dependent mechanism of liver injury, and this is supported by in vitro CYP450 inhibition with high doses of W Somnifera extract.11,13 We hypothesize that there may be a multihit process that makes some patients more susceptible to supplement harm, particularly those with repeated exposures and with ongoing exposure to hepatic toxins, such as AUD.14 Supplements should be used with more caution in these individuals.

Additionally, although there are no validated guidelines to confirm the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) from a manufactured medication or herbal remedy, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) developed RUCAM, a set of diagnostic criteria for DILI, which can be used to determine the probability of DILI based on pattern of injury.15 Although not widely used in clinical practice, RUCAM can help identify the possibility of DILI outside of expert consensus.16 It seems to have better discriminative ability than the Maria and Victorino scale, also used to identify DILI.16,17 While there is no replacement for clinical judgment, these scales may aid in identifying potential causes of DILI. The National Institutes of Health also has a LiverTox online tool that can assist health care professionals in identifying potentially hepatotoxic substances.6

Conclusions

We present a patient with AUD who developed cholestatic liver injury after ashwagandha use. Crucial to the diagnostic process is quantifying the amount ingested before presentation and the presence of contaminants, which is currently difficult to quantify given the lack of mechanisms to test supplements expediently in this manner in the clinical setting, which also requires the patient to bring in the supplements directly. There is also a lack of regulation and uniformity in these products. A clinician may be inclined to measure ashwagandha serum levels; however, such a test is not available to our knowledge. Nonetheless, using clinical tools such as RUCAM and utilizing databases, such as LiverTox, may help clinicians identify and remove potentially unsafe supplements. While there are many possible synergies between current medical practice and herbal remedies, practitioners must take care to first do no harm, as outlined in our Hippocratic Oath.

Many patients take herbals as alternative supplements to boost energy and mood. There are increasing reports of unintended adverse effects related to these supplements, particularly to the liver.1-3 A study by the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network found that liver injury caused by herbals and dietary supplements has increased from 7% in 2004 to 20% in 2013.4

The supplement ashwagandha has become increasingly popular. Ashwagandha is extracted from the root of Withania somnifera (

To date, the factors defining the population at risk for ashwagandha toxicity are unclear, and an understanding of how to diagnose drug-induced liver injury is still immature in clinical practice. The regulation and study of the herbal and dietary supplement industry remain challenging. While many so-called natural substances are well tolerated, others can have unanticipated and harmful adverse effects and drug interactions. Future research should not only identify potentially harmful substances, but also which patients may be at greatest risk.

Case Presentation

A 48-year-old man with a history of severe alcohol use disorder (AUD) complicated by fatty liver and withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens, hypertension, depression, and anxiety presented to the emergency department (ED) after 4 days of having jaundice, epigastric abdominal pain, dark urine, and pale stools. In the preceding months, he had increased his alcohol use to as many as 12 drinks daily due to depression. After experiencing a blackout, he stopped drinking 7 days before presenting to the ED. He felt withdrawal symptoms, including tremors, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. On the third day of withdrawals, he reported that he had started taking an over-the-counter testosterone-boosting supplement to increase his energy, which he referred to as TestBoost—a mix of 8 ingredients, including ashwagandha, eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry, longjack, ginseng root, mushroom extract, bindii, and horny goat weed. After taking the supplement for 2 days, he noticed that his urine darkened, his stools became paler, his abdominal pain worsened, and he became jaundiced. After 2 additional days without improvement, and still taking the supplement, he presented to the ED. He reported having no fever, chills, recent illness, chest pain, shortness of breath, melena, lower extremity swelling, recent travel, or any changes in medications.

The patient had a 100.1 °F temperature, 102 beats per minute pulse; 129/94 mm Hg blood pressure, 18 beats per minute respiratory rate, and 97% oxygen saturation on room air on admission. He was in no acute distress, though his examination was notable for generalized jaundice and scleral icterus. He was mildly tender to palpation in the epigastric and right upper quadrant region. He was alert and oriented without confusion. He did not have any asterixis or spider angiomas, though he had scattered bruises on his left flank and left calf. His laboratory results were notable for mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 58 U/L (reference range, 13-35); alanine transaminase (ALT), 49 U/L (reference range, 7-45); and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 98 U/L (reference range 33-94); total bilirubin, 13.6 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1.0); direct bilirubin, 8.4 mg/dL (reference range, 0.2-1); and international normalized ratio (INR), 1.11 (reference range, 2-3). His white blood cell and platelet counts were not remarkable at 9790/μL (reference range, 4500-11,000) and 337,000/μL (reference range, 150,000-440,000), respectively. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) revealed fatty liver with contracted gallbladder and no biliary dilatation. Urine ethanol levels were negative. The gastrointestinal (GI) service was consulted and agreed that his cholestatic injury was nonobstructive and likely related to the ashwagandha component of his supplement. The recommendation was cessation with close outpatient follow-up.

The patient was not prescribed any additional medications, such as steroids or ursodiol. He ceased supplement use following hospitalization; but relapsed into alcohol use 1 month after his discharge. Within 3 weeks, his total bilirubin had improved to 2.87 mg/dL, though AST, ALT, and ALP worsened to 127 U/L, 152 U/L, and 140 U/L, respectively. According to the notes of his psychiatrist who saw him at the time the laboratory tests were drawn, he had remained sober since discharge. His acute hepatitis panel drawn on admission was negative, and he demonstrated immunity to hepatitis A and B. Urine toxicology was negative. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was negative 1 year prior to discharge. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), ANA, antismooth muscle antibody, and immunoglobulins were not checked as suspicion for these etiologies was low. The Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) score was calculated as 6 (+1 for timing, +2 for drop in total bilirubin, +1 for ethanol risk factor, 0 for no other drugs, 0 for rule out of other diseases, +2 for known hepatotoxicity, 0 no repeat administration) for this patient indicating probable adverse drug reaction liver injury (Tables 1 and 2). However, we acknowledge that CMV, EBV, and herpes simplex virus status were not tested.

The 8 ingredients contained in TestBoost aside from ashwagandha did not have any major known liver adverse effects per a major database of medications. The other ingredients include eleuthero root, Hawthorn berry (crataegus laevigata), longjack (eurycoma longifolla) root, American ginseng root (American panax ginseng—panax quinquefolius), and Cordyceps mycelium (mushroom) extract, bindii (Tribulus terrestris), and epimedium grandiflorum (horny goat weed).6 No assays were performed to confirm purity of the ingredients in the patient’s supplement container.

Alcoholic hepatitis is an important consideration in this patient with AUD, though the timing of symptoms with supplement use and the cholestatic injury pattern with normal INR seems more consistent with drug-induced injury. Viral, infectious, and obstructive etiologies also were investigated. Acute viral hepatitis was ruled out based on bloodwork. The normal hepatobiliary tree on both ultrasound and CT effectively ruled out acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, and choledocholithiasis and there was no further indication for magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. There was no hepatic vein clot suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Autoimmune hepatitis was thought to be unlikely given that the etiology of injury seemed cholestatic in nature. Given the timing of the liver injury relative to supplement use it is likely that ashwagandha was a causative factor of this patient’s liver injury overlaid on an already strained liver from increased alcohol abuse.

The patient did not follow up with the GI service as an outpatient. There are no reports that the patient continued using the testosterone booster. His bilirubin improved dramatically within 1.5 months while his liver enzymes peaked 3 weeks later, with ALT ≥ AST. During his next admission 3 months later, he had relapsed, and his liver enzymes had the classic 2:1 AST to ALT ratio.

Discussion

Generally, ashwagandha has been thought to be well tolerated and possibly hepatoprotective.7-10 However, recent studies suggest potential for hepatotoxicity, though without clear guidance about which patients are most at risk.5,11,12 A study by Inagaki and colleagues suggests the potential for dose-dependent mechanism of liver injury, and this is supported by in vitro CYP450 inhibition with high doses of W Somnifera extract.11,13 We hypothesize that there may be a multihit process that makes some patients more susceptible to supplement harm, particularly those with repeated exposures and with ongoing exposure to hepatic toxins, such as AUD.14 Supplements should be used with more caution in these individuals.

Additionally, although there are no validated guidelines to confirm the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) from a manufactured medication or herbal remedy, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) developed RUCAM, a set of diagnostic criteria for DILI, which can be used to determine the probability of DILI based on pattern of injury.15 Although not widely used in clinical practice, RUCAM can help identify the possibility of DILI outside of expert consensus.16 It seems to have better discriminative ability than the Maria and Victorino scale, also used to identify DILI.16,17 While there is no replacement for clinical judgment, these scales may aid in identifying potential causes of DILI. The National Institutes of Health also has a LiverTox online tool that can assist health care professionals in identifying potentially hepatotoxic substances.6

Conclusions

We present a patient with AUD who developed cholestatic liver injury after ashwagandha use. Crucial to the diagnostic process is quantifying the amount ingested before presentation and the presence of contaminants, which is currently difficult to quantify given the lack of mechanisms to test supplements expediently in this manner in the clinical setting, which also requires the patient to bring in the supplements directly. There is also a lack of regulation and uniformity in these products. A clinician may be inclined to measure ashwagandha serum levels; however, such a test is not available to our knowledge. Nonetheless, using clinical tools such as RUCAM and utilizing databases, such as LiverTox, may help clinicians identify and remove potentially unsafe supplements. While there are many possible synergies between current medical practice and herbal remedies, practitioners must take care to first do no harm, as outlined in our Hippocratic Oath.

1. Navarro VJ. Herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29(4):373-382. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1240006

2. Suk KT, Kim DJ, Kim CH, et al. A prospective nationwide study of drug-induced liver injury in Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1380-1387. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.138

3. Shen T, Liu Y, Shang J, et al. Incidence and etiology of drug-induced liver injury in mainland China. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(8):2230-2241.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.002

4. Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology. 2014;60(4):1399-1408. doi:10.1002/hep.27317

5. Björnsson HK, Björnsson, Avula B, et al. (2020). Ashwagandha‐induced liver injury: a case series from Iceland and the US Drug‐Induced Liver Injury Network. Liver Int. 2020;40(4):825-829. doi:10.1111/liv.14393

6. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury [internet]. Ashwagandha. Updated May 2, 2019. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548536

7. Kumar G, Srivastava A, Sharma SK, Rao TD, Gupta YK. Efficacy and safety evaluation of Ayurvedic treatment (ashwagandha powder & Sidh Makardhwaj) in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a pilot prospective study. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141(1):100-106. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.154510

8. Kumar G, Srivastava A, Sharma SK, Gupta YK. Safety and efficacy evaluation of Ayurvedic treatment (arjuna powder and Arogyavardhini Vati) in dyslipidemia patients: a pilot prospective cohort clinical study. 2012;33(2):197-201. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.105238

9. Sultana N, Shimmi S, Parash MT, Akhtar J. Effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) root extract on some serum liver marker enzymes (AST, ALT) in gentamicin intoxicated rats. J Bangladesh Soc Physiologist. 2012;7(1): 1-7. doi:10.3329/JBSP.V7I1.11152

10. Patel DP, Yan T, Kim D, et al. Withaferin A improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371(2):360-374. doi:10.1124/jpet.119.256792

11. Inagaki K, Mori N, Honda Y, Takaki S, Tsuji K, Chayama K. A case of drug-induced liver injury with prolonged severe intrahepatic cholestasis induced by ashwagandha. Kanzo. 2017;58(8):448-454. doi:10.2957/kanzo.58.448

12. Alali F, Hermez K, Ullah N. Acute hepatitis induced by a unique combination of herbal supplements. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1661.

13. Sava J, Varghese A, Pandita N. Lack of the cytochrome P450 3A interaction of methanolic extract of Withania somnifera, Withaferin A, Withanolide A and Withanoside IV. J Pharm Negative Results. 2013;4(1):26.

14. Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):474-485. doi:10.1056/NEJMra021844.

15. Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs-I. A novel method based on the conclusions of International Consensus Meeting: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323–1333. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(93)90101-6

16. Hayashi PH. Causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29(4):348-356. doi.10.1002/cld.615

17. Lucena MI, Camargo R, Andrade RJ, Perez-Sanchez CJ, Sanchez De La Cuesta F. Comparison of two clinical scales for causality assessment in hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):123-130. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.20645

1. Navarro VJ. Herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29(4):373-382. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1240006

2. Suk KT, Kim DJ, Kim CH, et al. A prospective nationwide study of drug-induced liver injury in Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1380-1387. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.138

3. Shen T, Liu Y, Shang J, et al. Incidence and etiology of drug-induced liver injury in mainland China. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(8):2230-2241.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.002

4. Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology. 2014;60(4):1399-1408. doi:10.1002/hep.27317

5. Björnsson HK, Björnsson, Avula B, et al. (2020). Ashwagandha‐induced liver injury: a case series from Iceland and the US Drug‐Induced Liver Injury Network. Liver Int. 2020;40(4):825-829. doi:10.1111/liv.14393

6. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury [internet]. Ashwagandha. Updated May 2, 2019. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548536

7. Kumar G, Srivastava A, Sharma SK, Rao TD, Gupta YK. Efficacy and safety evaluation of Ayurvedic treatment (ashwagandha powder & Sidh Makardhwaj) in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a pilot prospective study. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141(1):100-106. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.154510

8. Kumar G, Srivastava A, Sharma SK, Gupta YK. Safety and efficacy evaluation of Ayurvedic treatment (arjuna powder and Arogyavardhini Vati) in dyslipidemia patients: a pilot prospective cohort clinical study. 2012;33(2):197-201. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.105238

9. Sultana N, Shimmi S, Parash MT, Akhtar J. Effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) root extract on some serum liver marker enzymes (AST, ALT) in gentamicin intoxicated rats. J Bangladesh Soc Physiologist. 2012;7(1): 1-7. doi:10.3329/JBSP.V7I1.11152

10. Patel DP, Yan T, Kim D, et al. Withaferin A improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371(2):360-374. doi:10.1124/jpet.119.256792

11. Inagaki K, Mori N, Honda Y, Takaki S, Tsuji K, Chayama K. A case of drug-induced liver injury with prolonged severe intrahepatic cholestasis induced by ashwagandha. Kanzo. 2017;58(8):448-454. doi:10.2957/kanzo.58.448

12. Alali F, Hermez K, Ullah N. Acute hepatitis induced by a unique combination of herbal supplements. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1661.

13. Sava J, Varghese A, Pandita N. Lack of the cytochrome P450 3A interaction of methanolic extract of Withania somnifera, Withaferin A, Withanolide A and Withanoside IV. J Pharm Negative Results. 2013;4(1):26.

14. Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):474-485. doi:10.1056/NEJMra021844.

15. Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs-I. A novel method based on the conclusions of International Consensus Meeting: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323–1333. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(93)90101-6

16. Hayashi PH. Causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29(4):348-356. doi.10.1002/cld.615

17. Lucena MI, Camargo R, Andrade RJ, Perez-Sanchez CJ, Sanchez De La Cuesta F. Comparison of two clinical scales for causality assessment in hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):123-130. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.20645

Nurses maintain more stigma toward pregnant women with OUD

Opioid use disorder among pregnant women continues to rise, and untreated opioid use is associated with complications including preterm delivery, placental abruption, and stillbirth, wrote Alexis Braverman, MD, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and colleagues. However, many perinatal women who seek care and medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) report stigma that limits their ability to reduce these risks.

In a study published in the American Journal on Addictions , the researchers conducted an anonymous survey of 132 health care workers at six outpatient locations and a main hospital of an urban medical center. The survey was designed to assess attitudes toward pregnant women who were using opioids. The 119 complete responses in the final analysis included 40 nurses and 79 clinicians across ob.gyn., family medicine, and pediatrics. A total of 19 respondents were waivered to prescribe outpatient buprenorphine for OUD.

Nurses were significantly less likely than clinicians to agree that OUD is a chronic illness, to feel sympathy for women who use opioids during pregnancy, and to see pregnancy as an opportunity for behavior change (P = .000, P = .003, and P = .001, respectively).

Overall, family medicine providers and clinicians with 11-20 years of practice experience were significantly more sympathetic to pregnant women who used opioids, compared with providers from other departments and with fewer years of practice (P = .025 and P = .039, respectively).

Providers in pediatrics departments were significantly more likely than those from other departments to agree strongly with feeling anger at pregnant women who use opioids (P = .009), and that these women should not be allowed to parent (P = .013). However, providers in pediatrics were significantly more comfortable than those in other departments with discussing the involvement of social services in patient care (P = .020) and with counseling patients on neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, known as NOWS (P = .027).

“We hypothesize that nurses who perform more acute, inpatient work rather than outpatient work may not be exposed as frequently to a patient’s personal progress on their journey with OUD,” and therefore might not be exposed to the rewarding experiences and progress made by patients, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

However, the overall low level of comfort in discussing NOWS and social service involvement across provider groups (one-quarter for pediatrics, one-fifth for ob.gyn, and one-sixth for family medicine) highlights the need for further training in this area, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the potential for responder bias; however, the results identify a need for greater training in stigma reduction and in counseling families on issues related to OUD, the researchers said. More studies are needed to examine attitude changes after the implementation of stigma reduction strategies, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Opioid use disorder among pregnant women continues to rise, and untreated opioid use is associated with complications including preterm delivery, placental abruption, and stillbirth, wrote Alexis Braverman, MD, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and colleagues. However, many perinatal women who seek care and medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) report stigma that limits their ability to reduce these risks.

In a study published in the American Journal on Addictions , the researchers conducted an anonymous survey of 132 health care workers at six outpatient locations and a main hospital of an urban medical center. The survey was designed to assess attitudes toward pregnant women who were using opioids. The 119 complete responses in the final analysis included 40 nurses and 79 clinicians across ob.gyn., family medicine, and pediatrics. A total of 19 respondents were waivered to prescribe outpatient buprenorphine for OUD.

Nurses were significantly less likely than clinicians to agree that OUD is a chronic illness, to feel sympathy for women who use opioids during pregnancy, and to see pregnancy as an opportunity for behavior change (P = .000, P = .003, and P = .001, respectively).

Overall, family medicine providers and clinicians with 11-20 years of practice experience were significantly more sympathetic to pregnant women who used opioids, compared with providers from other departments and with fewer years of practice (P = .025 and P = .039, respectively).

Providers in pediatrics departments were significantly more likely than those from other departments to agree strongly with feeling anger at pregnant women who use opioids (P = .009), and that these women should not be allowed to parent (P = .013). However, providers in pediatrics were significantly more comfortable than those in other departments with discussing the involvement of social services in patient care (P = .020) and with counseling patients on neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, known as NOWS (P = .027).

“We hypothesize that nurses who perform more acute, inpatient work rather than outpatient work may not be exposed as frequently to a patient’s personal progress on their journey with OUD,” and therefore might not be exposed to the rewarding experiences and progress made by patients, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

However, the overall low level of comfort in discussing NOWS and social service involvement across provider groups (one-quarter for pediatrics, one-fifth for ob.gyn, and one-sixth for family medicine) highlights the need for further training in this area, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the potential for responder bias; however, the results identify a need for greater training in stigma reduction and in counseling families on issues related to OUD, the researchers said. More studies are needed to examine attitude changes after the implementation of stigma reduction strategies, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Opioid use disorder among pregnant women continues to rise, and untreated opioid use is associated with complications including preterm delivery, placental abruption, and stillbirth, wrote Alexis Braverman, MD, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and colleagues. However, many perinatal women who seek care and medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) report stigma that limits their ability to reduce these risks.

In a study published in the American Journal on Addictions , the researchers conducted an anonymous survey of 132 health care workers at six outpatient locations and a main hospital of an urban medical center. The survey was designed to assess attitudes toward pregnant women who were using opioids. The 119 complete responses in the final analysis included 40 nurses and 79 clinicians across ob.gyn., family medicine, and pediatrics. A total of 19 respondents were waivered to prescribe outpatient buprenorphine for OUD.

Nurses were significantly less likely than clinicians to agree that OUD is a chronic illness, to feel sympathy for women who use opioids during pregnancy, and to see pregnancy as an opportunity for behavior change (P = .000, P = .003, and P = .001, respectively).

Overall, family medicine providers and clinicians with 11-20 years of practice experience were significantly more sympathetic to pregnant women who used opioids, compared with providers from other departments and with fewer years of practice (P = .025 and P = .039, respectively).

Providers in pediatrics departments were significantly more likely than those from other departments to agree strongly with feeling anger at pregnant women who use opioids (P = .009), and that these women should not be allowed to parent (P = .013). However, providers in pediatrics were significantly more comfortable than those in other departments with discussing the involvement of social services in patient care (P = .020) and with counseling patients on neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, known as NOWS (P = .027).

“We hypothesize that nurses who perform more acute, inpatient work rather than outpatient work may not be exposed as frequently to a patient’s personal progress on their journey with OUD,” and therefore might not be exposed to the rewarding experiences and progress made by patients, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

However, the overall low level of comfort in discussing NOWS and social service involvement across provider groups (one-quarter for pediatrics, one-fifth for ob.gyn, and one-sixth for family medicine) highlights the need for further training in this area, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the potential for responder bias; however, the results identify a need for greater training in stigma reduction and in counseling families on issues related to OUD, the researchers said. More studies are needed to examine attitude changes after the implementation of stigma reduction strategies, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL ON ADDICTIONS

Growing public perception that cannabis is safer than tobacco

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- While aggressive campaigns have led to a dramatic reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking and created safer smoke-free environments, regulation governing cannabis – which is associated with some health benefits but also many negative health outcomes – has been less restrictive.

- The study included a nationally representative sample of 5,035 mostly White U.S. adults, mean age 53.4 years, who completed three online surveys between 2017 and 2021 on the safety of tobacco and cannabis.

- In all three waves of the survey, respondents were asked to rate the safety of smoking one marijuana joint a day to smoking one cigarette a day, and of secondhand smoke from marijuana to that from tobacco.

- Respondents also expressed views on the safety of secondhand smoke exposure (of both marijuana and tobacco) on specific populations, including children, pregnant women, and adults (ratings were from “completely unsafe” to “completely safe”).

- Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, annual income, employment status, marital status, and state of residence.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a significant shift over time toward an increasingly favorable perception of cannabis; more respondents reported cannabis was “somewhat safer” or “much safer” than tobacco in 2021 than 2017 (44.3% vs. 36.7%; P < .001), and more believed secondhand smoke was somewhat or much safer for cannabis vs. tobacco in 2021 than in 2017 (40.2% vs. 35.1%; P < .001).

- More people endorsed the greater safety of secondhand smoke from cannabis vs. tobacco for children and pregnant women, and these perceptions remained similar over the study period.

- Younger and unmarried individuals were significantly more likely to move toward viewing smoking cannabis as safer than cigarettes, but legality of cannabis in respondents’ state of residence was not associated with change over time, suggesting the increasing perception of cannabis safety may be a national trend rather than a trend seen only in states with legalized cannabis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding changing views on tobacco and cannabis risk is important given that increases in social acceptance and decreases in risk perception may be directly associated with public health and policies,” the investigators write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Julia Chambers, MD, department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The generalizability of the study may be limited by nonresponse and loss to follow-up over time. The wording of survey questions may have introduced bias in respondents. Participants were asked about safety of smoking cannabis joints vs. tobacco cigarettes and not to compare safety of other forms of smoked and vaped cannabis, tobacco, and nicotine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. Dr. Chambers has no relevant conflicts of interest; author Katherine J. Hoggatt, PhD, MPH, department of medicine, UCSF, reported receiving grants from the Veterans Health Administration during the conduct of the study and grants from the National Institutes of Health, Rubin Family Foundation, and Veterans Health Administration outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- While aggressive campaigns have led to a dramatic reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking and created safer smoke-free environments, regulation governing cannabis – which is associated with some health benefits but also many negative health outcomes – has been less restrictive.

- The study included a nationally representative sample of 5,035 mostly White U.S. adults, mean age 53.4 years, who completed three online surveys between 2017 and 2021 on the safety of tobacco and cannabis.

- In all three waves of the survey, respondents were asked to rate the safety of smoking one marijuana joint a day to smoking one cigarette a day, and of secondhand smoke from marijuana to that from tobacco.

- Respondents also expressed views on the safety of secondhand smoke exposure (of both marijuana and tobacco) on specific populations, including children, pregnant women, and adults (ratings were from “completely unsafe” to “completely safe”).

- Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, annual income, employment status, marital status, and state of residence.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a significant shift over time toward an increasingly favorable perception of cannabis; more respondents reported cannabis was “somewhat safer” or “much safer” than tobacco in 2021 than 2017 (44.3% vs. 36.7%; P < .001), and more believed secondhand smoke was somewhat or much safer for cannabis vs. tobacco in 2021 than in 2017 (40.2% vs. 35.1%; P < .001).

- More people endorsed the greater safety of secondhand smoke from cannabis vs. tobacco for children and pregnant women, and these perceptions remained similar over the study period.

- Younger and unmarried individuals were significantly more likely to move toward viewing smoking cannabis as safer than cigarettes, but legality of cannabis in respondents’ state of residence was not associated with change over time, suggesting the increasing perception of cannabis safety may be a national trend rather than a trend seen only in states with legalized cannabis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding changing views on tobacco and cannabis risk is important given that increases in social acceptance and decreases in risk perception may be directly associated with public health and policies,” the investigators write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Julia Chambers, MD, department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The generalizability of the study may be limited by nonresponse and loss to follow-up over time. The wording of survey questions may have introduced bias in respondents. Participants were asked about safety of smoking cannabis joints vs. tobacco cigarettes and not to compare safety of other forms of smoked and vaped cannabis, tobacco, and nicotine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. Dr. Chambers has no relevant conflicts of interest; author Katherine J. Hoggatt, PhD, MPH, department of medicine, UCSF, reported receiving grants from the Veterans Health Administration during the conduct of the study and grants from the National Institutes of Health, Rubin Family Foundation, and Veterans Health Administration outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- While aggressive campaigns have led to a dramatic reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking and created safer smoke-free environments, regulation governing cannabis – which is associated with some health benefits but also many negative health outcomes – has been less restrictive.

- The study included a nationally representative sample of 5,035 mostly White U.S. adults, mean age 53.4 years, who completed three online surveys between 2017 and 2021 on the safety of tobacco and cannabis.

- In all three waves of the survey, respondents were asked to rate the safety of smoking one marijuana joint a day to smoking one cigarette a day, and of secondhand smoke from marijuana to that from tobacco.

- Respondents also expressed views on the safety of secondhand smoke exposure (of both marijuana and tobacco) on specific populations, including children, pregnant women, and adults (ratings were from “completely unsafe” to “completely safe”).

- Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, annual income, employment status, marital status, and state of residence.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a significant shift over time toward an increasingly favorable perception of cannabis; more respondents reported cannabis was “somewhat safer” or “much safer” than tobacco in 2021 than 2017 (44.3% vs. 36.7%; P < .001), and more believed secondhand smoke was somewhat or much safer for cannabis vs. tobacco in 2021 than in 2017 (40.2% vs. 35.1%; P < .001).

- More people endorsed the greater safety of secondhand smoke from cannabis vs. tobacco for children and pregnant women, and these perceptions remained similar over the study period.

- Younger and unmarried individuals were significantly more likely to move toward viewing smoking cannabis as safer than cigarettes, but legality of cannabis in respondents’ state of residence was not associated with change over time, suggesting the increasing perception of cannabis safety may be a national trend rather than a trend seen only in states with legalized cannabis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding changing views on tobacco and cannabis risk is important given that increases in social acceptance and decreases in risk perception may be directly associated with public health and policies,” the investigators write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Julia Chambers, MD, department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The generalizability of the study may be limited by nonresponse and loss to follow-up over time. The wording of survey questions may have introduced bias in respondents. Participants were asked about safety of smoking cannabis joints vs. tobacco cigarettes and not to compare safety of other forms of smoked and vaped cannabis, tobacco, and nicotine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. Dr. Chambers has no relevant conflicts of interest; author Katherine J. Hoggatt, PhD, MPH, department of medicine, UCSF, reported receiving grants from the Veterans Health Administration during the conduct of the study and grants from the National Institutes of Health, Rubin Family Foundation, and Veterans Health Administration outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adaptive treatment aids smoking cessation

Smokers who followed an adaptive treatment regimen with drug patches had greater smoking abstinence after 12 weeks than did those who followed a standard regimen, based on data from 188 individuals.

Adaptive pharmacotherapy is a common strategy across many medical conditions, but its use in smoking cessation treatments involving skin patches has not been examined, wrote James M. Davis, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 188 adults who sought smoking cessation treatment at a university health system between February 2018 and May 2020. The researchers planned to enroll 300 adults, but enrollment was truncated because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants chose between varenicline or nicotine patches, and then were randomized to an adaptive or standard treatment regimen. All participants started their medication 4 weeks before their target quit smoking day.

A total of 127 participants chose varenicline, with 64 randomized to adaptive treatment and 63 randomized to standard treatment; 61 participants chose nicotine patches, with 31 randomized to adaptive treatment and 30 randomized to standard treatment. Overall, participants smoked a mean of 15.4 cigarettes per day at baseline. The mean age of the participants was 49.1 years; 54% were female, 52% were White, and 48% were Black. Baseline demographics were similar between the groups.

The primary outcome was 30-day continuous abstinence from smoking (biochemically verified) at 12 weeks after each participant’s target quit date.

After 2 weeks (2 weeks before the target quit smoking day), all participants were assessed for treatment response. Those in the adaptive group who were deemed responders, defined as a reduction in daily cigarettes of at least 50%, received placebo bupropion. Those in the adaptive group deemed nonresponders received 150 mg bupropion twice daily in addition to their patch regimen. The standard treatment group also received placebo bupropion.

At 12 weeks after the target quit day, 24% of the adaptive group demonstrated 30-day continuous smoking abstinence, compared with 9% of the standard group (odds ratio, 3.38; P = .004). Smoking abstinence was higher in the adaptive vs. placebo groups for those who used varenicline patches (28% vs. 8%; OR, 4.54) and for those who used nicotine patches (16% vs. 10%; OR, 1.73).