User login

VIDEO: Anemia more than doubles risk of postpartum depression

AUSTIN, TEX. – The risk of depression was more than doubled in women who were anemic during pregnancy, according to a recent retrospective cohort study of nearly 1,000 women. Among patients who had anemia at any point, the relative risk of screening positive for postpartum depression was 2.25 (95% confidence interval, 1.22-4.16).

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“This was an unexpected finding,” said Shannon Sutherland, MD, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, in an interview after she presented the findings at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“Maternal suicide exceeds hemorrhage and hypertensive disease as a cause of U.S. maternal mortality,” wrote Dr. Sutherland and her collaborators in the poster accompanying the presentation. And anemia is common: “Anemia in pregnancy can be as high as 27.4% in low-income minority pregnant women in the third trimester,” they wrote.

“If we can find something like this that affects depression, and screen for it and correct for it, we can make a real big difference in patients’ lives,” said Dr. Sutherland in a video interview. “Screening for anemia ... is such a simple thing for us to do, and I also think it’s very easy for us to correct, and very cheap for us to correct.”

The 922 study participants were at least 16 years old and receiving postpartum care at an outpatient women’s health clinic. Patients who had diseases that disrupted iron metabolism or were tobacco users, and those on antidepressants, anxiolytics, or antipsychotics were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria included anemia that required transfusion, and intrauterine fetal demise or neonatal mortality.

To assess depression, Dr. Sutherland and her colleagues administered the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at routine postpartum visits. Dr. Sutherland and her coinvestigators calculated the numbers of respondents who fell above and below the cutoff for potential depression on the 10-item self-report scale. They then looked at the proportion of women who scored positive for depression among those who were, and those who were not, anemic.

Possible depression was indicated by depression scale scores of 9.2% of participants, while three quarters (75.2%) were anemic either during pregnancy or in the immediate postpartum period. Among anemic patients, 10.8% screened positive for depression, while 4.8% of those without anemia met positive screening criteria for postpartum depression (P = .007).

Dr. Sutherland and her collaborators noted that fewer women in their cohort had postpartum depression than the national average of 19%. They may have missed some patients who would later develop depression since the screening occurred at the first postpartum visit; also, “it is possible that women deeply affected by [postpartum depression] may have been lost to follow-up,” they wrote.

Participants had a mean age of about 26 years, and body mass index was slightly higher for those with anemia than without (mean, 32.2 vs 31.2 kg/m2; P = .025).

Postpartum depression was not associated with marital status, substance use, ethnicity, parity, or the occurrence of postpartum hemorrhage, in the investigators’ analysis.

Dr. Sutherland said that, in their analysis, she and her coinvestigators did not find an association between degree of anemia and the likelihood, or severity, of postpartum depression. However, they did find that anemia of any degree in the immediate peripartum period was most strongly associated with postpartum depression.

Though the exact mechanism of the anemia-depression link isn’t known, the fatigue associated with anemia may help predispose women to postpartum depression, said Dr. Sutherland. Also, she said, “iron can make a difference in synthesizing neurotransmitters” such as serotonin, “so it may follow that you might have some depressive symptoms.”

“The next step after this study, which was a launching point, is to see if we correct the degree of anemia and bring them to normal levels, if that can help decrease the risk of postpartum depression,” said Dr. Sutherland.

Dr. Sutherland and her coinvestigators reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sutherland S et al. ACOG 2018. Abstract 35C.

AUSTIN, TEX. – The risk of depression was more than doubled in women who were anemic during pregnancy, according to a recent retrospective cohort study of nearly 1,000 women. Among patients who had anemia at any point, the relative risk of screening positive for postpartum depression was 2.25 (95% confidence interval, 1.22-4.16).

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“This was an unexpected finding,” said Shannon Sutherland, MD, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, in an interview after she presented the findings at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“Maternal suicide exceeds hemorrhage and hypertensive disease as a cause of U.S. maternal mortality,” wrote Dr. Sutherland and her collaborators in the poster accompanying the presentation. And anemia is common: “Anemia in pregnancy can be as high as 27.4% in low-income minority pregnant women in the third trimester,” they wrote.

“If we can find something like this that affects depression, and screen for it and correct for it, we can make a real big difference in patients’ lives,” said Dr. Sutherland in a video interview. “Screening for anemia ... is such a simple thing for us to do, and I also think it’s very easy for us to correct, and very cheap for us to correct.”

The 922 study participants were at least 16 years old and receiving postpartum care at an outpatient women’s health clinic. Patients who had diseases that disrupted iron metabolism or were tobacco users, and those on antidepressants, anxiolytics, or antipsychotics were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria included anemia that required transfusion, and intrauterine fetal demise or neonatal mortality.

To assess depression, Dr. Sutherland and her colleagues administered the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at routine postpartum visits. Dr. Sutherland and her coinvestigators calculated the numbers of respondents who fell above and below the cutoff for potential depression on the 10-item self-report scale. They then looked at the proportion of women who scored positive for depression among those who were, and those who were not, anemic.

Possible depression was indicated by depression scale scores of 9.2% of participants, while three quarters (75.2%) were anemic either during pregnancy or in the immediate postpartum period. Among anemic patients, 10.8% screened positive for depression, while 4.8% of those without anemia met positive screening criteria for postpartum depression (P = .007).

Dr. Sutherland and her collaborators noted that fewer women in their cohort had postpartum depression than the national average of 19%. They may have missed some patients who would later develop depression since the screening occurred at the first postpartum visit; also, “it is possible that women deeply affected by [postpartum depression] may have been lost to follow-up,” they wrote.

Participants had a mean age of about 26 years, and body mass index was slightly higher for those with anemia than without (mean, 32.2 vs 31.2 kg/m2; P = .025).

Postpartum depression was not associated with marital status, substance use, ethnicity, parity, or the occurrence of postpartum hemorrhage, in the investigators’ analysis.

Dr. Sutherland said that, in their analysis, she and her coinvestigators did not find an association between degree of anemia and the likelihood, or severity, of postpartum depression. However, they did find that anemia of any degree in the immediate peripartum period was most strongly associated with postpartum depression.

Though the exact mechanism of the anemia-depression link isn’t known, the fatigue associated with anemia may help predispose women to postpartum depression, said Dr. Sutherland. Also, she said, “iron can make a difference in synthesizing neurotransmitters” such as serotonin, “so it may follow that you might have some depressive symptoms.”

“The next step after this study, which was a launching point, is to see if we correct the degree of anemia and bring them to normal levels, if that can help decrease the risk of postpartum depression,” said Dr. Sutherland.

Dr. Sutherland and her coinvestigators reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sutherland S et al. ACOG 2018. Abstract 35C.

AUSTIN, TEX. – The risk of depression was more than doubled in women who were anemic during pregnancy, according to a recent retrospective cohort study of nearly 1,000 women. Among patients who had anemia at any point, the relative risk of screening positive for postpartum depression was 2.25 (95% confidence interval, 1.22-4.16).

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“This was an unexpected finding,” said Shannon Sutherland, MD, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, in an interview after she presented the findings at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“Maternal suicide exceeds hemorrhage and hypertensive disease as a cause of U.S. maternal mortality,” wrote Dr. Sutherland and her collaborators in the poster accompanying the presentation. And anemia is common: “Anemia in pregnancy can be as high as 27.4% in low-income minority pregnant women in the third trimester,” they wrote.

“If we can find something like this that affects depression, and screen for it and correct for it, we can make a real big difference in patients’ lives,” said Dr. Sutherland in a video interview. “Screening for anemia ... is such a simple thing for us to do, and I also think it’s very easy for us to correct, and very cheap for us to correct.”

The 922 study participants were at least 16 years old and receiving postpartum care at an outpatient women’s health clinic. Patients who had diseases that disrupted iron metabolism or were tobacco users, and those on antidepressants, anxiolytics, or antipsychotics were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria included anemia that required transfusion, and intrauterine fetal demise or neonatal mortality.

To assess depression, Dr. Sutherland and her colleagues administered the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at routine postpartum visits. Dr. Sutherland and her coinvestigators calculated the numbers of respondents who fell above and below the cutoff for potential depression on the 10-item self-report scale. They then looked at the proportion of women who scored positive for depression among those who were, and those who were not, anemic.

Possible depression was indicated by depression scale scores of 9.2% of participants, while three quarters (75.2%) were anemic either during pregnancy or in the immediate postpartum period. Among anemic patients, 10.8% screened positive for depression, while 4.8% of those without anemia met positive screening criteria for postpartum depression (P = .007).

Dr. Sutherland and her collaborators noted that fewer women in their cohort had postpartum depression than the national average of 19%. They may have missed some patients who would later develop depression since the screening occurred at the first postpartum visit; also, “it is possible that women deeply affected by [postpartum depression] may have been lost to follow-up,” they wrote.

Participants had a mean age of about 26 years, and body mass index was slightly higher for those with anemia than without (mean, 32.2 vs 31.2 kg/m2; P = .025).

Postpartum depression was not associated with marital status, substance use, ethnicity, parity, or the occurrence of postpartum hemorrhage, in the investigators’ analysis.

Dr. Sutherland said that, in their analysis, she and her coinvestigators did not find an association between degree of anemia and the likelihood, or severity, of postpartum depression. However, they did find that anemia of any degree in the immediate peripartum period was most strongly associated with postpartum depression.

Though the exact mechanism of the anemia-depression link isn’t known, the fatigue associated with anemia may help predispose women to postpartum depression, said Dr. Sutherland. Also, she said, “iron can make a difference in synthesizing neurotransmitters” such as serotonin, “so it may follow that you might have some depressive symptoms.”

“The next step after this study, which was a launching point, is to see if we correct the degree of anemia and bring them to normal levels, if that can help decrease the risk of postpartum depression,” said Dr. Sutherland.

Dr. Sutherland and her coinvestigators reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sutherland S et al. ACOG 2018. Abstract 35C.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

VIDEO: Consider unique stressors when treating members of peacekeeping operations

NEW YORK – Sustained peacekeeping operations are associated with unique psychological stressors, and understanding of these stressors on the part of both community and military psychiatrists can help make a difference at each stage of a deployment cycle, according to Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

During a workshop at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association entitled “War and Peace: Understanding the Psychological Stressors Associated with Sustained Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs),” chaired by Dr. Ritchie of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., various dimensions of salient psychological stress were discussed, as were approaches for minimizing any resultant impact on the psychological health of peacekeepers.

In this video interview, Dr. Ritchie discussed the differences and similarities between peacekeeping operations and military operations with respect to stressors and their effects, and the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder among peacekeepers.

Although treatment for PTSD is “pretty much the same,” it is important to “tailor the treatment for the situation,” she said.

“Lay out the different options, explain them to the patient, and partner with the patient in terms of what is the best option for them,” she said.

Dr. Ritchie reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Ritchie EC et al. APA Workshop

NEW YORK – Sustained peacekeeping operations are associated with unique psychological stressors, and understanding of these stressors on the part of both community and military psychiatrists can help make a difference at each stage of a deployment cycle, according to Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

During a workshop at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association entitled “War and Peace: Understanding the Psychological Stressors Associated with Sustained Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs),” chaired by Dr. Ritchie of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., various dimensions of salient psychological stress were discussed, as were approaches for minimizing any resultant impact on the psychological health of peacekeepers.

In this video interview, Dr. Ritchie discussed the differences and similarities between peacekeeping operations and military operations with respect to stressors and their effects, and the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder among peacekeepers.

Although treatment for PTSD is “pretty much the same,” it is important to “tailor the treatment for the situation,” she said.

“Lay out the different options, explain them to the patient, and partner with the patient in terms of what is the best option for them,” she said.

Dr. Ritchie reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Ritchie EC et al. APA Workshop

NEW YORK – Sustained peacekeeping operations are associated with unique psychological stressors, and understanding of these stressors on the part of both community and military psychiatrists can help make a difference at each stage of a deployment cycle, according to Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

During a workshop at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association entitled “War and Peace: Understanding the Psychological Stressors Associated with Sustained Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs),” chaired by Dr. Ritchie of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., various dimensions of salient psychological stress were discussed, as were approaches for minimizing any resultant impact on the psychological health of peacekeepers.

In this video interview, Dr. Ritchie discussed the differences and similarities between peacekeeping operations and military operations with respect to stressors and their effects, and the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder among peacekeepers.

Although treatment for PTSD is “pretty much the same,” it is important to “tailor the treatment for the situation,” she said.

“Lay out the different options, explain them to the patient, and partner with the patient in terms of what is the best option for them,” she said.

Dr. Ritchie reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Ritchie EC et al. APA Workshop

VIDEO: Research underscores murky relationship between mental illness, gun violence

NEW YORK – Legislation enacted in some states in the wake of mass shootings seeks to limit access to firearms for people with mental illness, but research presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association raises questions about the value of that approach.

During a workshop entitled “The ‘Crazed Gunman’ Myth: Examining Mental Illness and Firearm Violence,” researchers from the Yale University in New Haven, Conn., presented new findings that support existing data calling into question whether laws considered to be “common-sense approaches” to stopping gun violence really can reduce the likelihood of mass shootings.

It appears, based on the frequency and context of firearm use in more than 400 crimes that resulted in an insanity acquittal in Connecticut, for example, that individuals with mental illness are less likely than others to misuse firearms.

In this video, workshop chair Reena Kapoor, MD, also of Yale University, discusses the findings and notes that she and her colleagues seek to move past politics and ideology to focus on science that can guide policy and legislative efforts in a potentially more effective direction.

“We’ve also found that in spite of the media narrative, there has also been a slight decrease in how often [mentally ill offenders] use guns, over the years in the study,” she said. “Although the data are preliminary, it doesn’t support this idea that mentally ill people are more dangerous than ever, that they’re using guns more often in their violence; it actually says quite the opposite.”

Dr. Kapoor reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kapoor R et al. APA 2018 Workshop.

NEW YORK – Legislation enacted in some states in the wake of mass shootings seeks to limit access to firearms for people with mental illness, but research presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association raises questions about the value of that approach.

During a workshop entitled “The ‘Crazed Gunman’ Myth: Examining Mental Illness and Firearm Violence,” researchers from the Yale University in New Haven, Conn., presented new findings that support existing data calling into question whether laws considered to be “common-sense approaches” to stopping gun violence really can reduce the likelihood of mass shootings.

It appears, based on the frequency and context of firearm use in more than 400 crimes that resulted in an insanity acquittal in Connecticut, for example, that individuals with mental illness are less likely than others to misuse firearms.

In this video, workshop chair Reena Kapoor, MD, also of Yale University, discusses the findings and notes that she and her colleagues seek to move past politics and ideology to focus on science that can guide policy and legislative efforts in a potentially more effective direction.

“We’ve also found that in spite of the media narrative, there has also been a slight decrease in how often [mentally ill offenders] use guns, over the years in the study,” she said. “Although the data are preliminary, it doesn’t support this idea that mentally ill people are more dangerous than ever, that they’re using guns more often in their violence; it actually says quite the opposite.”

Dr. Kapoor reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kapoor R et al. APA 2018 Workshop.

NEW YORK – Legislation enacted in some states in the wake of mass shootings seeks to limit access to firearms for people with mental illness, but research presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association raises questions about the value of that approach.

During a workshop entitled “The ‘Crazed Gunman’ Myth: Examining Mental Illness and Firearm Violence,” researchers from the Yale University in New Haven, Conn., presented new findings that support existing data calling into question whether laws considered to be “common-sense approaches” to stopping gun violence really can reduce the likelihood of mass shootings.

It appears, based on the frequency and context of firearm use in more than 400 crimes that resulted in an insanity acquittal in Connecticut, for example, that individuals with mental illness are less likely than others to misuse firearms.

In this video, workshop chair Reena Kapoor, MD, also of Yale University, discusses the findings and notes that she and her colleagues seek to move past politics and ideology to focus on science that can guide policy and legislative efforts in a potentially more effective direction.

“We’ve also found that in spite of the media narrative, there has also been a slight decrease in how often [mentally ill offenders] use guns, over the years in the study,” she said. “Although the data are preliminary, it doesn’t support this idea that mentally ill people are more dangerous than ever, that they’re using guns more often in their violence; it actually says quite the opposite.”

Dr. Kapoor reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kapoor R et al. APA 2018 Workshop.

REPORTING FROM APA

VIDEO: Few transgender patients desire care in a transgender-only clinic

AUSTIN, TEX. – Transgender patients face many barriers to care, including a lack of necessary expertise among providers, but a large majority of those surveyed in a study in which they were asked whether they would want to go to a transgender-only clinic said they would not.

Lauren Abern, MD, of Atrius Health, Cambridge, Mass., discussed the aims and results of her survey at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The anonymous online survey consisted of 120 individuals, aged 18-64 years: 100 transgender men and 20 transgender women. Of these, 83 reported experiencing barriers to care. The most common problem cited was cost (68, 82%), and other barriers were access to care (47, 57%), stigma (33, 40%), and discrimination (23, 26%). Cost was a factor even though a large majority of the respondents had health insurance; a majority of respondents had an income of less than $24,000 per year.

The most common way respondents found transgender-competent health care was through word of mouth (79, 77%).

When asked whether they would want to go to a transgender-only clinic, a majority of both transgender women and transgender men respondents either answered, “no,” or that they were unsure (86, 77%). Some respondents cited a desire not to out themselves as transgender, and others considered the separate clinic medically unnecessary. One wrote: “You wouldn’t need a broken foot–only clinic.”

“Basic preventative services can be provided without specific expertise in transgender health. If providers are uncomfortable, they should refer [transgender patients] elsewhere.” said Dr. Abern.

The survey project was conducted in collaboration with the University of Miami and the YES Institute in Miami.

Dr. Abern also spoke about wider transgender health considerations for the ob.gyn. in a separate presentation at the meeting and in a video interview.

For example, transgender men on testosterone may have persistent bleeding and may be uncomfortable with pelvic exams.

Making more inclusive intake forms and fostering a respectful office environment (for example, having a nondiscrimination policy displayed in the waiting area) are measures beneficial to all patients, she said.

“My dream or goal would be that transgender people can be seen and accepted at any office and feel comfortable and not avoid seeking health care.”

AUSTIN, TEX. – Transgender patients face many barriers to care, including a lack of necessary expertise among providers, but a large majority of those surveyed in a study in which they were asked whether they would want to go to a transgender-only clinic said they would not.

Lauren Abern, MD, of Atrius Health, Cambridge, Mass., discussed the aims and results of her survey at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The anonymous online survey consisted of 120 individuals, aged 18-64 years: 100 transgender men and 20 transgender women. Of these, 83 reported experiencing barriers to care. The most common problem cited was cost (68, 82%), and other barriers were access to care (47, 57%), stigma (33, 40%), and discrimination (23, 26%). Cost was a factor even though a large majority of the respondents had health insurance; a majority of respondents had an income of less than $24,000 per year.

The most common way respondents found transgender-competent health care was through word of mouth (79, 77%).

When asked whether they would want to go to a transgender-only clinic, a majority of both transgender women and transgender men respondents either answered, “no,” or that they were unsure (86, 77%). Some respondents cited a desire not to out themselves as transgender, and others considered the separate clinic medically unnecessary. One wrote: “You wouldn’t need a broken foot–only clinic.”

“Basic preventative services can be provided without specific expertise in transgender health. If providers are uncomfortable, they should refer [transgender patients] elsewhere.” said Dr. Abern.

The survey project was conducted in collaboration with the University of Miami and the YES Institute in Miami.

Dr. Abern also spoke about wider transgender health considerations for the ob.gyn. in a separate presentation at the meeting and in a video interview.

For example, transgender men on testosterone may have persistent bleeding and may be uncomfortable with pelvic exams.

Making more inclusive intake forms and fostering a respectful office environment (for example, having a nondiscrimination policy displayed in the waiting area) are measures beneficial to all patients, she said.

“My dream or goal would be that transgender people can be seen and accepted at any office and feel comfortable and not avoid seeking health care.”

AUSTIN, TEX. – Transgender patients face many barriers to care, including a lack of necessary expertise among providers, but a large majority of those surveyed in a study in which they were asked whether they would want to go to a transgender-only clinic said they would not.

Lauren Abern, MD, of Atrius Health, Cambridge, Mass., discussed the aims and results of her survey at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The anonymous online survey consisted of 120 individuals, aged 18-64 years: 100 transgender men and 20 transgender women. Of these, 83 reported experiencing barriers to care. The most common problem cited was cost (68, 82%), and other barriers were access to care (47, 57%), stigma (33, 40%), and discrimination (23, 26%). Cost was a factor even though a large majority of the respondents had health insurance; a majority of respondents had an income of less than $24,000 per year.

The most common way respondents found transgender-competent health care was through word of mouth (79, 77%).

When asked whether they would want to go to a transgender-only clinic, a majority of both transgender women and transgender men respondents either answered, “no,” or that they were unsure (86, 77%). Some respondents cited a desire not to out themselves as transgender, and others considered the separate clinic medically unnecessary. One wrote: “You wouldn’t need a broken foot–only clinic.”

“Basic preventative services can be provided without specific expertise in transgender health. If providers are uncomfortable, they should refer [transgender patients] elsewhere.” said Dr. Abern.

The survey project was conducted in collaboration with the University of Miami and the YES Institute in Miami.

Dr. Abern also spoke about wider transgender health considerations for the ob.gyn. in a separate presentation at the meeting and in a video interview.

For example, transgender men on testosterone may have persistent bleeding and may be uncomfortable with pelvic exams.

Making more inclusive intake forms and fostering a respectful office environment (for example, having a nondiscrimination policy displayed in the waiting area) are measures beneficial to all patients, she said.

“My dream or goal would be that transgender people can be seen and accepted at any office and feel comfortable and not avoid seeking health care.”

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Maternal morbidity and BMI: A dose-response relationship

AUSTIN, TEX. – Women with the highest levels of obesity were at higher odds of experiencing a composite serious maternal morbidity outcome, while women at all levels of obesity experienced elevated risks of some serious complications of pregnancy, compared with women with a body mass index (BMI) in the normal range, according to a recent study.

Looking at individual indicators of severe maternal morbidity, Marissa Platner, MD, and her study coauthors saw that women who fell into the higher levels of obesity had significantly elevated odds of some complications.

“Those risks are really impressive, with odds ratios of two and three times that of a normal-weight patient,” said Dr. Platner in a video interview.

The adjusted odds ratio of acute renal failure for women with superobesity (BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more) was 3.62 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-7.52); odds ratios for renal failure were not significantly elevated for less-obese women.

Women with all levels of obesity had elevated risks of experiencing heart failure during a procedure or surgery, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.68 (95% CI, 1.48-1.93) for women with class I obesity (BMI, 30-34.9 kg/m2) to 2.23 for women with superobesity (95% CI, 1.15-4.33).

Results from the retrospective cohort study were presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Platner and her colleagues examined 4 years of New York City delivery data that were linked to birth certificates, identifying those singleton live births for whom maternal prepregnancy BMI data were available.

From this group, they included women aged 15-50 years who delivered at 20-45 weeks’ gestational age. Women with prepregnancy BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2 – those who were underweight – were excluded.

Dr. Platner and her coinvestigators used multivariable analysis to see what association the full range of obesity classes had with severe maternal morbidity, adjusting for many socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Of the 539,870 women included in the study, 3.3% experienced severe maternal morbidity, and 17.4% of patients met criteria for obesity. “Across all classes of obesity, there was a significantly greater risk of severe maternal morbidity, compared to nonobese women,” wrote Dr. Platner and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation.

These risks climbed for women with the highest BMIs, however. “Women with higher levels of obesity, not surprisingly, are at increased risk” of severe maternal morbidity, said Dr. Platner. She and her colleagues noted in the poster that, “There is a significant dose-response relationship between increasing obesity class and risk of [severe maternal morbidity] at delivery hospitalization.”

It had been known that women with obesity are at increased risk of some serious complications of pregnancy, including severe maternal morbidity and mortality, and that those considered morbidly obese – with BMIs of 40 and above – are most likely to experience these complications, Dr. Platner said. However, she added, there’s a paucity of data to inform maternal risk stratification by level of obesity.

“We included the group of superobese women, which is significant in the surgical literature, and that’s a BMI of 50 and above ... we thought that would be an important subgroup to analyze in this population,” she said.

Dr. Platner said that she and her colleagues already had the clinical impressions that women with the highest BMIs were most likely to have serious complications. “I don’t think that these findings are particularly surprising,” she said. “This is what our hypothesis was in terms of why we did this study.”

The greater surprise, she said, was the magnitude of increased risk seen for serious morbidity with higher levels of obesity.

“Really, the risk is truly increased for those women with class III or superobesity, and when we start to stratify ... those are the women we need to be concerned about in terms of our prenatal counseling,” said Dr. Platner, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“What can we do to intervene before we get there?” asked Dr. Platner. Although data are lacking about what specific interventions might be able to reduce the risk of these serious complications, she said she could envision such steps as acquiring predelivery baseline ECGs and cardiac ultrasounds in women with higher levels of obesity and being sure to follow renal function closely as well.

The findings also may help physicians provide more evidence-based preconception advice to women who are among the 35% of American adults who have obesity.

Dr. Platner reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Platner M et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 39I.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AUSTIN, TEX. – Women with the highest levels of obesity were at higher odds of experiencing a composite serious maternal morbidity outcome, while women at all levels of obesity experienced elevated risks of some serious complications of pregnancy, compared with women with a body mass index (BMI) in the normal range, according to a recent study.

Looking at individual indicators of severe maternal morbidity, Marissa Platner, MD, and her study coauthors saw that women who fell into the higher levels of obesity had significantly elevated odds of some complications.

“Those risks are really impressive, with odds ratios of two and three times that of a normal-weight patient,” said Dr. Platner in a video interview.

The adjusted odds ratio of acute renal failure for women with superobesity (BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more) was 3.62 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-7.52); odds ratios for renal failure were not significantly elevated for less-obese women.

Women with all levels of obesity had elevated risks of experiencing heart failure during a procedure or surgery, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.68 (95% CI, 1.48-1.93) for women with class I obesity (BMI, 30-34.9 kg/m2) to 2.23 for women with superobesity (95% CI, 1.15-4.33).

Results from the retrospective cohort study were presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Platner and her colleagues examined 4 years of New York City delivery data that were linked to birth certificates, identifying those singleton live births for whom maternal prepregnancy BMI data were available.

From this group, they included women aged 15-50 years who delivered at 20-45 weeks’ gestational age. Women with prepregnancy BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2 – those who were underweight – were excluded.

Dr. Platner and her coinvestigators used multivariable analysis to see what association the full range of obesity classes had with severe maternal morbidity, adjusting for many socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Of the 539,870 women included in the study, 3.3% experienced severe maternal morbidity, and 17.4% of patients met criteria for obesity. “Across all classes of obesity, there was a significantly greater risk of severe maternal morbidity, compared to nonobese women,” wrote Dr. Platner and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation.

These risks climbed for women with the highest BMIs, however. “Women with higher levels of obesity, not surprisingly, are at increased risk” of severe maternal morbidity, said Dr. Platner. She and her colleagues noted in the poster that, “There is a significant dose-response relationship between increasing obesity class and risk of [severe maternal morbidity] at delivery hospitalization.”

It had been known that women with obesity are at increased risk of some serious complications of pregnancy, including severe maternal morbidity and mortality, and that those considered morbidly obese – with BMIs of 40 and above – are most likely to experience these complications, Dr. Platner said. However, she added, there’s a paucity of data to inform maternal risk stratification by level of obesity.

“We included the group of superobese women, which is significant in the surgical literature, and that’s a BMI of 50 and above ... we thought that would be an important subgroup to analyze in this population,” she said.

Dr. Platner said that she and her colleagues already had the clinical impressions that women with the highest BMIs were most likely to have serious complications. “I don’t think that these findings are particularly surprising,” she said. “This is what our hypothesis was in terms of why we did this study.”

The greater surprise, she said, was the magnitude of increased risk seen for serious morbidity with higher levels of obesity.

“Really, the risk is truly increased for those women with class III or superobesity, and when we start to stratify ... those are the women we need to be concerned about in terms of our prenatal counseling,” said Dr. Platner, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“What can we do to intervene before we get there?” asked Dr. Platner. Although data are lacking about what specific interventions might be able to reduce the risk of these serious complications, she said she could envision such steps as acquiring predelivery baseline ECGs and cardiac ultrasounds in women with higher levels of obesity and being sure to follow renal function closely as well.

The findings also may help physicians provide more evidence-based preconception advice to women who are among the 35% of American adults who have obesity.

Dr. Platner reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Platner M et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 39I.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AUSTIN, TEX. – Women with the highest levels of obesity were at higher odds of experiencing a composite serious maternal morbidity outcome, while women at all levels of obesity experienced elevated risks of some serious complications of pregnancy, compared with women with a body mass index (BMI) in the normal range, according to a recent study.

Looking at individual indicators of severe maternal morbidity, Marissa Platner, MD, and her study coauthors saw that women who fell into the higher levels of obesity had significantly elevated odds of some complications.

“Those risks are really impressive, with odds ratios of two and three times that of a normal-weight patient,” said Dr. Platner in a video interview.

The adjusted odds ratio of acute renal failure for women with superobesity (BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more) was 3.62 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-7.52); odds ratios for renal failure were not significantly elevated for less-obese women.

Women with all levels of obesity had elevated risks of experiencing heart failure during a procedure or surgery, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.68 (95% CI, 1.48-1.93) for women with class I obesity (BMI, 30-34.9 kg/m2) to 2.23 for women with superobesity (95% CI, 1.15-4.33).

Results from the retrospective cohort study were presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Platner and her colleagues examined 4 years of New York City delivery data that were linked to birth certificates, identifying those singleton live births for whom maternal prepregnancy BMI data were available.

From this group, they included women aged 15-50 years who delivered at 20-45 weeks’ gestational age. Women with prepregnancy BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2 – those who were underweight – were excluded.

Dr. Platner and her coinvestigators used multivariable analysis to see what association the full range of obesity classes had with severe maternal morbidity, adjusting for many socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Of the 539,870 women included in the study, 3.3% experienced severe maternal morbidity, and 17.4% of patients met criteria for obesity. “Across all classes of obesity, there was a significantly greater risk of severe maternal morbidity, compared to nonobese women,” wrote Dr. Platner and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation.

These risks climbed for women with the highest BMIs, however. “Women with higher levels of obesity, not surprisingly, are at increased risk” of severe maternal morbidity, said Dr. Platner. She and her colleagues noted in the poster that, “There is a significant dose-response relationship between increasing obesity class and risk of [severe maternal morbidity] at delivery hospitalization.”

It had been known that women with obesity are at increased risk of some serious complications of pregnancy, including severe maternal morbidity and mortality, and that those considered morbidly obese – with BMIs of 40 and above – are most likely to experience these complications, Dr. Platner said. However, she added, there’s a paucity of data to inform maternal risk stratification by level of obesity.

“We included the group of superobese women, which is significant in the surgical literature, and that’s a BMI of 50 and above ... we thought that would be an important subgroup to analyze in this population,” she said.

Dr. Platner said that she and her colleagues already had the clinical impressions that women with the highest BMIs were most likely to have serious complications. “I don’t think that these findings are particularly surprising,” she said. “This is what our hypothesis was in terms of why we did this study.”

The greater surprise, she said, was the magnitude of increased risk seen for serious morbidity with higher levels of obesity.

“Really, the risk is truly increased for those women with class III or superobesity, and when we start to stratify ... those are the women we need to be concerned about in terms of our prenatal counseling,” said Dr. Platner, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“What can we do to intervene before we get there?” asked Dr. Platner. Although data are lacking about what specific interventions might be able to reduce the risk of these serious complications, she said she could envision such steps as acquiring predelivery baseline ECGs and cardiac ultrasounds in women with higher levels of obesity and being sure to follow renal function closely as well.

The findings also may help physicians provide more evidence-based preconception advice to women who are among the 35% of American adults who have obesity.

Dr. Platner reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Platner M et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 39I.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Tardive dyskinesia: Screening and management

Underserved populations and colorectal cancer screening: Patient perceptions of barriers to care and effective interventions

Editor's Note:

Importantly, these barriers often vary between specific population subsets. In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, the members of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee provide an enlightening overview of the barriers affecting underserved populations as well as strategies that can be employed to overcome these impediments. Better understanding of patient-specific barriers will, I hope, allow us to more effectively redress them and ultimately increase colorectal cancer screening rates in all populations.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Despite the positive public health effects of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, there remains differential uptake of CRC screening in the United States. Minority populations born in the United States and immigrant populations are among those with the lowest rates of CRC screening, and both socioeconomic status and ethnicity are strongly associated with stage of CRC at diagnosis.1,2 Thus, recognizing the economic, social, and cultural factors that result in low rates of CRC screening in underserved populations is important in order to devise targeted interventions to increase CRC uptake and reduce morbidity and mortality in these populations.

What are the facts and figures?

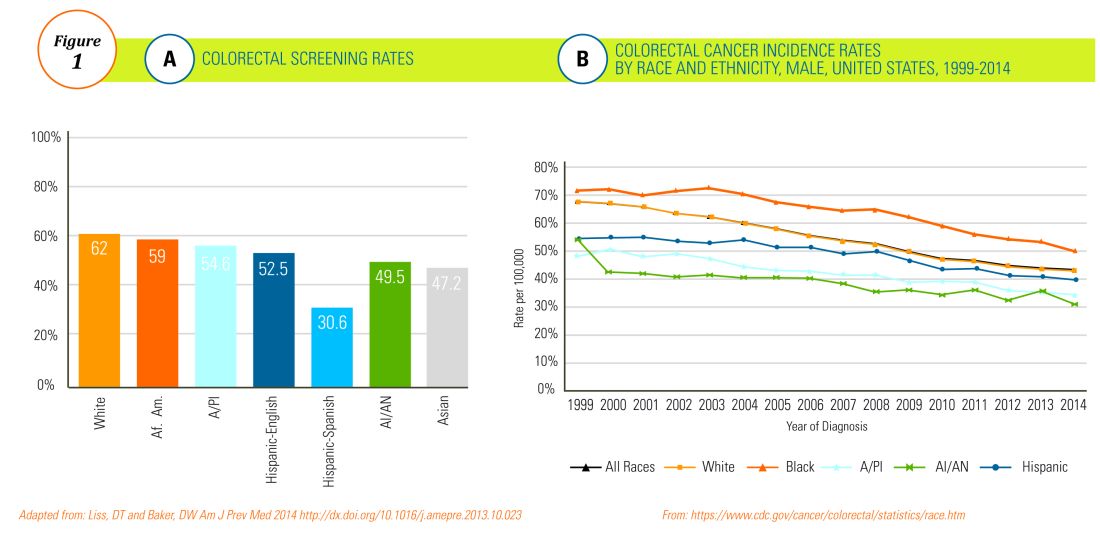

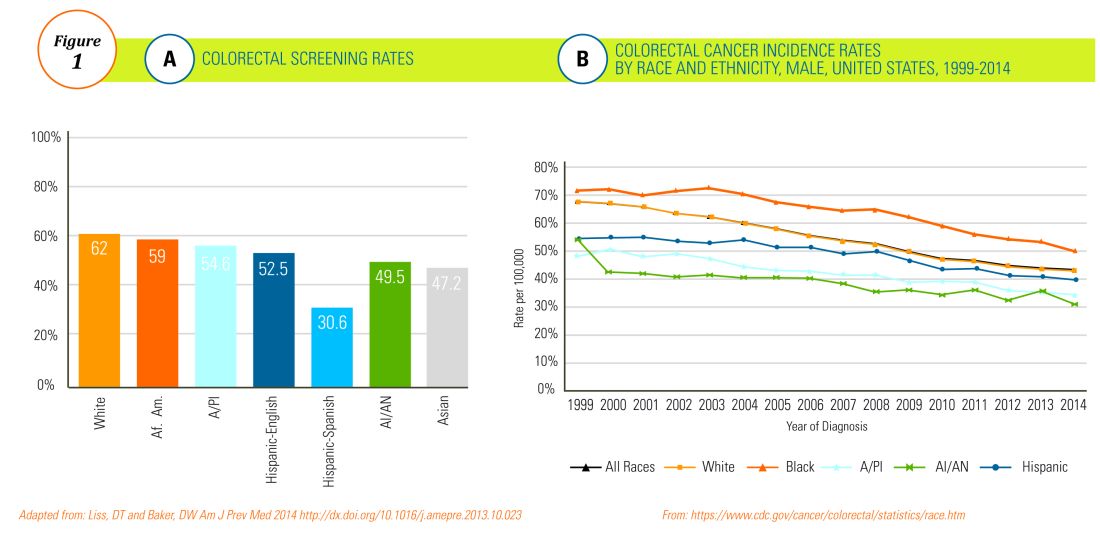

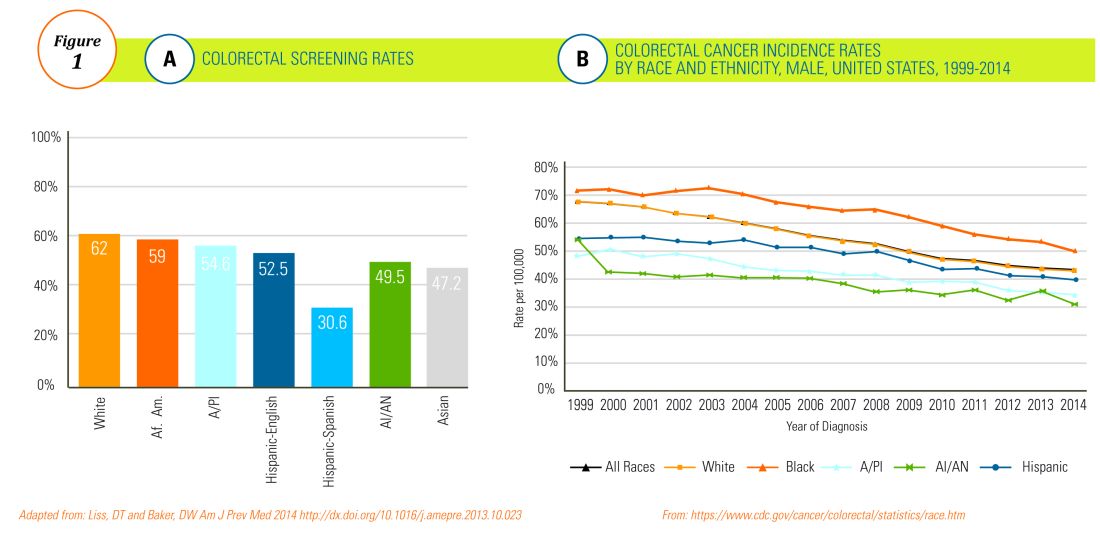

The overall rate of screening colonoscopies has increased in all ethnic groups in the past 10 years but still falls below the goal of 71% established by the Healthy People project (www.healthypeople.gov) for the year 2020.3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ethnicity-specific data for U.S.-born populations, 60% of whites, 55% of African Americans (AA), 50% of American Indian/Alaskan natives (AI/AN), 46% of Latino Americans, and 47% of Asians undergo CRC screening (Figure 1A).4 While CRC incidence in non-Hispanic whites age 50 years and older has dropped by 32% since 2000 because of screening, this trend has not been observed in AAs.5,6

The incidence of CRC in AAs is estimated at 49/10,000, one of the highest amongst U.S. populations and is the second and third most common cancer in AA women and men, respectively (Figure 1B).

Similar to AAs, AI/AN patients present with more advanced CRC disease and at younger ages and have lower survival rates, compared with other racial groups, a trend that has not changed in the last decade.7 CRC screening data in this population vary according to sex, geographic location, and health care utilization, with as few as 4.0% of asymptomatic, average-risk AI/ANs who receive medical care in the Indian Health Services being screened for CRC.8

The low rate of CRC screening among Latinos also poses a significant obstacle to the Healthy People project since it is expected that by 2060 Latinos will constitute 30% of the U.S. population. Therefore, strategies to improve CRC screening in this population are needed to continue the gains made in overall CRC mortality rates.

The percentage of immigrants in the U.S. population increased from 4.7% in 1970 to 13.5% in 2015. Immigrants, regardless of their ethnicity, represent a very vulnerable population, and CRC screening data in this population are not as robust as for U.S.-born groups. In general, immigrants have substantially lower CRC screening rates, compared with U.S.-born populations (21% vs. 60%),9 and it is suspected that additional, significant barriers to CRC screening and care exist for undocumented immigrants.

Another often overlooked group, are individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. In this group, screening rates range from 49% to 65%.10

Finally, while information is available for many health care conditions and disparities faced by various ethnic groups, there are few CRC screening data for the LGBTQ community. Perhaps amplifying this problem is the existence of conflicting data in this population, with some studies suggesting there is no difference in CRC risk across groups in the LGBTQ community and others suggesting an increased risk.11,12 Notably, sexual orientation has been identified as a positive predictor of CRC screening in gay and bisexual men – CRC screening rates are higher in these groups, compared with heterosexual men.13 In contrast, no such difference has been found between homosexual and heterosexual women.14

What are the barriers?

Several common themes contribute to disparities in CRC screening among minority groups, including psychosocial/cultural, socioeconomic, provider-specific, and insurance-related factors. Some patient-related barriers include issues of illiteracy, having poor health literacy or English proficiency, having only grade school education,15,16 cultural misconceptions, transportation issues, difficulties affording copayments or deductibles, and a lack of follow-up for scheduled appointments and exams.17-20 Poor health literacy has a profound effect on exam perceptions, fear of test results, and compliance with scheduling tests and bowel preparation instructions21-25; it also affects one’s understanding of the importance of CRC screening, the recommended screening age, and the available choice of screening tests.

Even when some apparent barriers are mitigated, disparities in CRC screening remain. For example, even among the insured and among Medicare beneficiaries, screening rates and adequate follow-up rates after abnormal findings remain lower among AAs and those of low socioeconomic status than they are among whites.26-28 At least part of this paradox results from the presence of unmeasured cultural/belief systems that affect CRC screening uptake. Some of these factors include fear and/or denial of CRC diagnoses, mistrust of the health care system, and reluctance to undergo medical treatment and surgery.16,29 AAs are also less likely to be aware of a family history of CRC and to discuss personal and/or family history of CRC or polyps, which can thereby hinder the identification of high-risk individuals who would benefit from early screening.15,30

The deeply rooted sense of fatalism also plays a crucial role and has been cited for many minority and immigrant populations. Fatalism leads patients to view a diagnosis of cancer as a matter of “fate” or “God’s will,” and therefore, it is to be endured.23,31 Similarly, in a qualitative study of 44 Somali men living in St. Paul and Minneapolis, believing cancer was more common in whites, believing they were protected from cancer by God, fearing a cancer diagnosis, and fearing ostracism from their community were reported as barriers to cancer screening.32

Perceptions about CRC screening methods in Latino populations also have a tremendous influence and can include fear, stigma of sexual prejudice, embarrassment of being exposed during the exam, worries about humiliation in a male sense of masculinity, a lack of trust in the medical professionals, a sense of being a “guinea pig” for physicians, concerns about health care racism, and expectations of pain.33-37 Studies have reported that immigrants are afraid to seek health care because of the increasingly hostile environment associated with immigration enforcement.38 In addition, the impending dissolution of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals act is likely to augment the barriers to care for Latino groups.39

In addition, provider-specific barriers to care also exist. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than whites to receive recommendations for screening by their physician. In fact, this factor alone has been demonstrated to be the main reason for lack of screening among AAs in a Californian cohort.40 In addition, patients from rural areas or those from AI/AN communities are at especially increased risk for lack of access to care because of a scarcity of providers along with patient perceptions regarding their primary care provider’s ability to connect them to subspecialists.41-43 Other cited examples include misconceptions about and poor treatment of the LGBTQ population by health care providers/systems.44

How can we intervene successfully?

Characterization of barriers is important because it promotes the development of targeted interventions. Intervention models include community engagement programs, incorporation of fecal occult testing, and patient navigator programs.45-47 In response to the alarming disparity in CRC screening rates in Latino communities, several interventions have been set in motion in different clinical scenarios, which include patient navigation and a focus on patient education.

Randomized trials have shown that outreach efforts and patient navigation increase CRC screening rates in AAs.48,54,55 Studies evaluating the effects of print-based educational materials on improving screening showed improvement in screening rates, decreases in cancer-related fatalistic attitudes, and patients had a better understanding of the benefits of screening as compared with the cost associated with screening and the cost of advanced disease.56 Similarly, the use of touch-screen computers that tailor informational messages to decisional stage and screening barriers increased participation in CRC screening.57 Including patient navigators along with printed education material was even more effective at increasing the proportion of patients getting colonoscopy screening than providing printed material alone, with more-intensive navigation needed for individuals with low literacy.58 Grubbs et al.reported the success of their patient navigation program, which included wider comprehensive screening and coverage for colonoscopy screening.59 In AAs, they estimated an annual reduction of CRC incidence and mortality of 4,200 and 2,700 patients, respectively.

Among immigrants, there is an increased likelihood of CRC screening in those immigrants with a higher number of primary care visits.60 The intersection of culture, race, socioeconomic status, housing enclaves, limited English proficiency, low health literacy, and immigration policy all play a role in immigrant health and access to health care.61

Therefore, different strategies may be needed for each immigrant group to improve CRC screening. For this group of patients, efforts aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of national immigration policies on immigrant populations may have the additional consequence of improving health care access and CRC screening for these patients.

Data gaps still exist in our understanding of patient perceptions, perspectives, and barriers that present opportunities for further study to develop long-lasting interventions that will improve health care of underserved populations. By raising awareness of the barriers, physicians can enhance their own self-awareness to keenly be attuned to these challenges as patients cross their clinic threshold for medical care.

Additional resources link: www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/

References

1. Klabunde CN et al. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 Aug;20(8):1611-21.

2. Parikh-Patel A et al. Colorectal cancer stage at diagnosis by socioeconomic and urban/rural status in California, 1988-2000. Cancer. 2006 Sep;107(5 Suppl):1189-95.

3. Promotion OoDPaH. Healthy People 2020. Cancer. Volume 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening – United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Jan 27;61(3):41-5.

5. Doubeni CA et al. Racial and ethnic trends of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Feb;38(2):184-91.

6. Kupfer SS et al. Reducing colorectal cancer risk among African Americans. Gastroenterology. 2015 Nov;149(6):1302-4.

7. Espey DK et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007 Nov;110(10):2119-52.

8. Day LW et al. Screening prevalence and incidence of colorectal cancer among American Indian/Alaskan natives in the Indian Health Service. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Jul;56(7):2104-13.

9. Gupta S et al. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Apr;106(4):dju032.

10. Steele CB et al. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening – United States, 2008 and 2010. MMWR Suppl. 2013 Nov 22;62(3):53-60.

11. Boehmer U et al. Cancer survivorship and sexual orientation. Cancer 2011 Aug 15;117(16):3796-804.

12. Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Wei EK, et al. Application of the Rosner-Wei risk-prediction model to estimate sexual orientation patterns in colon cancer risk in a prospective cohort of US women. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Aug;25(8):999-1006.

13. Heslin KC et al. Sexual orientation and testing for prostate and colorectal cancers among men in California. Med Care. 2008 Dec;46(12):1240-8.

14. McElroy JA et al. Advancing Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients in Missouri. Mo Med. 2015 Jul-Aug;112(4):262-5.

15. Greiner KA et al. Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Nov;20(11):977-83.

16. Green PM, Kelly BA. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004 May-Jun;27(3):206-15; quiz 216-7.

17. Berkowitz Z et al. Beliefs, risk perceptions, and gaps in knowledge as barriers to colorectal cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Feb;56(2):307-14.

18. Dolan NC et al. Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among veterans: Does literacy make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jul;22(13):2617-22.

19. Peterson NB et al. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007 Oct;99(10):1105-12.

20. Haddock MG et al. Intraoperative irradiation for locally recurrent colorectal cancer in previously irradiated patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Apr 1;49(5):1267-74.

21. Jones RM et al. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010 May;38(5):508-16.

22. Basch CH et al. Screening colonoscopy bowel preparation: experience in an urban minority population. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov;6(6):442-6.

23. Davis JL et al. Sociodemographic differences in fears and mistrust contributing to unwillingness to participate in cancer screenings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012 Nov;23(4 Suppl):67-76.

24. Robinson CM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among publicly insured urban women: no knowledge of tests and no clinician recommendation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011 Aug;103(8):746-53.

25. Goldman RE et al. Perspectives of colorectal cancer risk and screening among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans: Stigma and misperceptions. Qual Health Res. 2009 Nov;19(11):1559-68.

26. Laiyemo AO et al. Race and colorectal cancer disparities: Health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010 Apr 21;102(8):538-46.

27. White A et al. Racial disparities and treatment trends in a large cohort of elderly African Americans and Caucasians with colorectal cancer, 1991 to 2002. Cancer. 2008 Dec 15;113(12):3400-9.

28. Doubeni CA et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and use of colonoscopy in an insured population – A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36392.

29. Tammana VS, Laiyemo AO. Colorectal cancer disparities: Issues, controversies and solutions. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan 28;20(4):869-76.

30. Carethers JM. Screening for colorectal cancer in African Americans: determinants and rationale for an earlier age to commence screening. Dig Dis Sci. 2015 Mar;60(3):711-21.

31. Miranda-Diaz C et al. Barriers for Compliance to Breast, Colorectal, and Cervical Screening Cancer Tests among Hispanic Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Dec 22;13(1):ijerph13010021.

32. Sewali B et al. Understanding cancer screening service utilization by Somali men in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015 Jun;17(3):773-80.

33. Walsh JM et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. Compared with non-Latino white Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):156-66.

34. Perez-Stable EJ et al. Self-reported use of cancer screening tests among Latinos and Anglos in a prepaid health plan. Arch Intern Med. 1994 May 23;154(10):1073-81.

35. Shariff-Marco S et al. Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported racism and its association with cancer-related health behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100(2):364-74.

36. Powe BD et al. Comparing knowledge of colorectal and prostate cancer among African American and Hispanic men. Cancer Nurs. 2009 Sep-Oct;32(5):412-7.

37. Jun J, Oh KM. Asian and Hispanic Americans’ cancer fatalism and colon cancer screening. Am J Health Behav. 2013 Mar;37(2):145-54.

38. Hacker K et al. The impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on immigrant health: Perceptions of immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2011 Aug;73(4):586-94.

39. Firger J. Rescinding DACA could spur a public health crisis, from lost services to higher rates of depression, substance abuse. Newsweek.

40. May FP et al. Racial minorities are more likely than whites to report lack of provider recommendation for colon cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Oct;110(10):1388-94.

41. Levy BT et al. Why hasn’t this patient been screened for colon cancer? An Iowa Research Network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;20(5):458-68.

42. Rosenblatt RA. A view from the periphery – health care in rural America. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 9;351(11):1049-51.

43. Young WF et al. Predictors of colorectal screening in rural Colorado: testing to prevent colon cancer in the high plains research network. J Rural Health. 2007 Summer;23(3):238-45.

44. Kates J et al. Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Individuals in the U.S. In: Foundation KF, ed. Disparities Policy Issue Brief. Volume 2017; Aug 30, 2017.

45. Katz ML et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007 Oct 1;110(7):1602-10.

46. Jean-Jacques M et al. Program to improve colorectal cancer screening in a low-income, racially diverse population: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012 Sep-Oct;10(5):412-7.

47. Reuland DS et al. Effect of combined patient decision aid and patient navigation vs usual care for colorectal cancer screening in a vulnerable patient population: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jul 1;177(7):967-74.

48. Percac-Lima S et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Feb;24(2):211-7.

49. Nash D et al. Evaluation of an intervention to increase screening colonoscopy in an urban public hospital setting. J Urban Health. 2006 Mar;83(2):231-43.

50. Lebwohl B et al. Effect of a patient navigator program on the volume and quality of colonoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 May-Jun;45(5):e47-53.

51. Khankari K et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening among the medically underserved: A pilot study within a federally qualified health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Oct;22(10):1410-4.

52. Wang JH et al. Recruiting Chinese Americans into cancer screening intervention trials: Strategies and outcomes. Clin Trials. 2014 Apr;11(2):167-77.

53. Katz ML et al. Patient activation increases colorectal cancer screening rates: a randomized trial among low-income minority patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Jan;21(1):45-52.

54. Ford ME et al. Enhancing adherence among older African American men enrolled in a longitudinal cancer screening trial. Gerontologist. 2006 Aug;46(4):545-50.

55. Christie J et al. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008 Mar;100(3):278-84.

56. Philip EJ et al. Evaluating the impact of an educational intervention to increase CRC screening rates in the African American community: A preliminary study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010 Oct;21(10):1685-91.

57. Greiner KA et al. Implementation intentions and colorectal screening: A randomized trial in safety-net clinics. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Dec;47(6):703-14.

58. Horne HN et al. Effect of patient navigation on colorectal cancer screening in a community-based randomized controlled trial of urban African American adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2015 Feb;26(2):239-46.

59. Grubbs SS et al. Eliminating racial disparities in colorectal cancer in the real world: It took a village. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jun 1;31(16):1928-30.

60. Jung MY et al. The Chinese and Korean American immigrant experience: a mixed-methods examination of facilitators and barriers of colorectal cancer screening. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb 25:1-20.

61. Viruell-Fuentes EA et al. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Dec;75(12):2099-106.

Dr. Oduyebo is a third-year fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Malespin is an assistant professor in the department of medicine and the medical director of hepatology at the University of Florida Health, Jacksonville; Dr. Mendoza Ladd is an assistant professor of medicine at Texas Tech University, El Paso; Dr. Day is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Charabaty is an associate professor of medicine and the director of the IBD Center in the division of gastroenterology at Medstar-Georgetown University Center, Washington; Dr. Chen is an associate professor of medicine, the director of patient safety and quality, and the director of the small-bowel endoscopy program in division of gastroenterology at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Carr is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Dr. Quezada is an assistant dean for admissions, an assistant dean for academic and multicultural affairs, and an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore; and Dr. Lamousé-Smith is a director of translational medicine, immunology, and early development at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Research and Development, Spring House, Penn.

Editor's Note:

Importantly, these barriers often vary between specific population subsets. In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, the members of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee provide an enlightening overview of the barriers affecting underserved populations as well as strategies that can be employed to overcome these impediments. Better understanding of patient-specific barriers will, I hope, allow us to more effectively redress them and ultimately increase colorectal cancer screening rates in all populations.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Despite the positive public health effects of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, there remains differential uptake of CRC screening in the United States. Minority populations born in the United States and immigrant populations are among those with the lowest rates of CRC screening, and both socioeconomic status and ethnicity are strongly associated with stage of CRC at diagnosis.1,2 Thus, recognizing the economic, social, and cultural factors that result in low rates of CRC screening in underserved populations is important in order to devise targeted interventions to increase CRC uptake and reduce morbidity and mortality in these populations.

What are the facts and figures?

The overall rate of screening colonoscopies has increased in all ethnic groups in the past 10 years but still falls below the goal of 71% established by the Healthy People project (www.healthypeople.gov) for the year 2020.3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ethnicity-specific data for U.S.-born populations, 60% of whites, 55% of African Americans (AA), 50% of American Indian/Alaskan natives (AI/AN), 46% of Latino Americans, and 47% of Asians undergo CRC screening (Figure 1A).4 While CRC incidence in non-Hispanic whites age 50 years and older has dropped by 32% since 2000 because of screening, this trend has not been observed in AAs.5,6

The incidence of CRC in AAs is estimated at 49/10,000, one of the highest amongst U.S. populations and is the second and third most common cancer in AA women and men, respectively (Figure 1B).

Similar to AAs, AI/AN patients present with more advanced CRC disease and at younger ages and have lower survival rates, compared with other racial groups, a trend that has not changed in the last decade.7 CRC screening data in this population vary according to sex, geographic location, and health care utilization, with as few as 4.0% of asymptomatic, average-risk AI/ANs who receive medical care in the Indian Health Services being screened for CRC.8

The low rate of CRC screening among Latinos also poses a significant obstacle to the Healthy People project since it is expected that by 2060 Latinos will constitute 30% of the U.S. population. Therefore, strategies to improve CRC screening in this population are needed to continue the gains made in overall CRC mortality rates.

The percentage of immigrants in the U.S. population increased from 4.7% in 1970 to 13.5% in 2015. Immigrants, regardless of their ethnicity, represent a very vulnerable population, and CRC screening data in this population are not as robust as for U.S.-born groups. In general, immigrants have substantially lower CRC screening rates, compared with U.S.-born populations (21% vs. 60%),9 and it is suspected that additional, significant barriers to CRC screening and care exist for undocumented immigrants.

Another often overlooked group, are individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. In this group, screening rates range from 49% to 65%.10

Finally, while information is available for many health care conditions and disparities faced by various ethnic groups, there are few CRC screening data for the LGBTQ community. Perhaps amplifying this problem is the existence of conflicting data in this population, with some studies suggesting there is no difference in CRC risk across groups in the LGBTQ community and others suggesting an increased risk.11,12 Notably, sexual orientation has been identified as a positive predictor of CRC screening in gay and bisexual men – CRC screening rates are higher in these groups, compared with heterosexual men.13 In contrast, no such difference has been found between homosexual and heterosexual women.14

What are the barriers?

Several common themes contribute to disparities in CRC screening among minority groups, including psychosocial/cultural, socioeconomic, provider-specific, and insurance-related factors. Some patient-related barriers include issues of illiteracy, having poor health literacy or English proficiency, having only grade school education,15,16 cultural misconceptions, transportation issues, difficulties affording copayments or deductibles, and a lack of follow-up for scheduled appointments and exams.17-20 Poor health literacy has a profound effect on exam perceptions, fear of test results, and compliance with scheduling tests and bowel preparation instructions21-25; it also affects one’s understanding of the importance of CRC screening, the recommended screening age, and the available choice of screening tests.

Even when some apparent barriers are mitigated, disparities in CRC screening remain. For example, even among the insured and among Medicare beneficiaries, screening rates and adequate follow-up rates after abnormal findings remain lower among AAs and those of low socioeconomic status than they are among whites.26-28 At least part of this paradox results from the presence of unmeasured cultural/belief systems that affect CRC screening uptake. Some of these factors include fear and/or denial of CRC diagnoses, mistrust of the health care system, and reluctance to undergo medical treatment and surgery.16,29 AAs are also less likely to be aware of a family history of CRC and to discuss personal and/or family history of CRC or polyps, which can thereby hinder the identification of high-risk individuals who would benefit from early screening.15,30

The deeply rooted sense of fatalism also plays a crucial role and has been cited for many minority and immigrant populations. Fatalism leads patients to view a diagnosis of cancer as a matter of “fate” or “God’s will,” and therefore, it is to be endured.23,31 Similarly, in a qualitative study of 44 Somali men living in St. Paul and Minneapolis, believing cancer was more common in whites, believing they were protected from cancer by God, fearing a cancer diagnosis, and fearing ostracism from their community were reported as barriers to cancer screening.32

Perceptions about CRC screening methods in Latino populations also have a tremendous influence and can include fear, stigma of sexual prejudice, embarrassment of being exposed during the exam, worries about humiliation in a male sense of masculinity, a lack of trust in the medical professionals, a sense of being a “guinea pig” for physicians, concerns about health care racism, and expectations of pain.33-37 Studies have reported that immigrants are afraid to seek health care because of the increasingly hostile environment associated with immigration enforcement.38 In addition, the impending dissolution of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals act is likely to augment the barriers to care for Latino groups.39

In addition, provider-specific barriers to care also exist. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than whites to receive recommendations for screening by their physician. In fact, this factor alone has been demonstrated to be the main reason for lack of screening among AAs in a Californian cohort.40 In addition, patients from rural areas or those from AI/AN communities are at especially increased risk for lack of access to care because of a scarcity of providers along with patient perceptions regarding their primary care provider’s ability to connect them to subspecialists.41-43 Other cited examples include misconceptions about and poor treatment of the LGBTQ population by health care providers/systems.44

How can we intervene successfully?

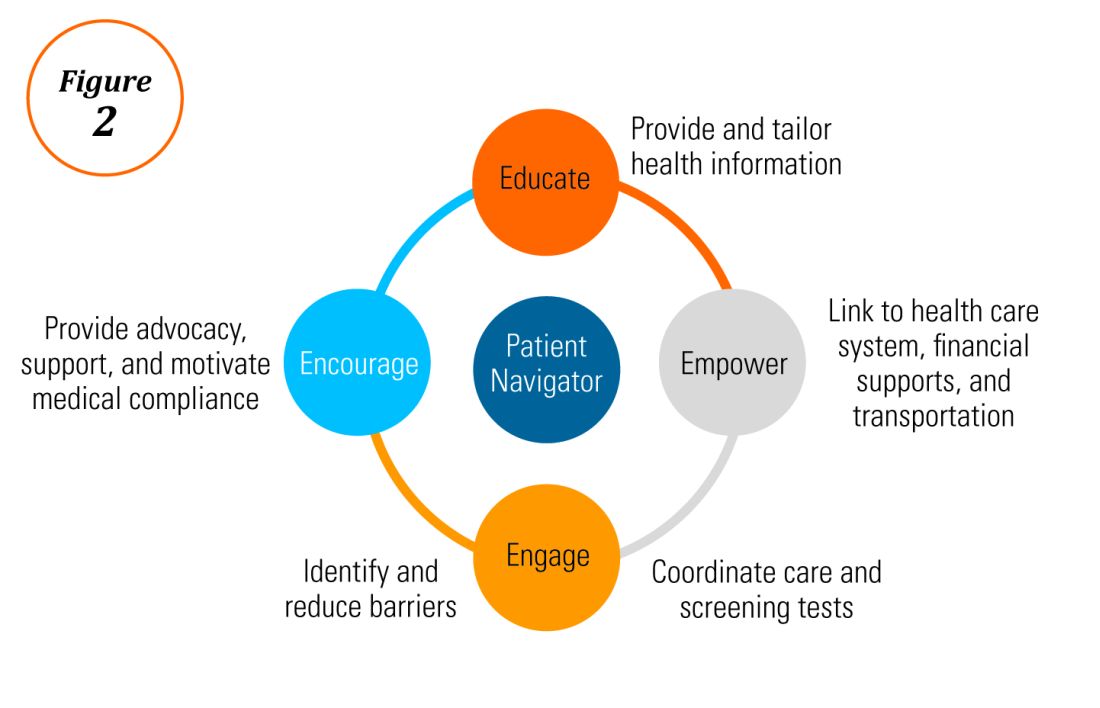

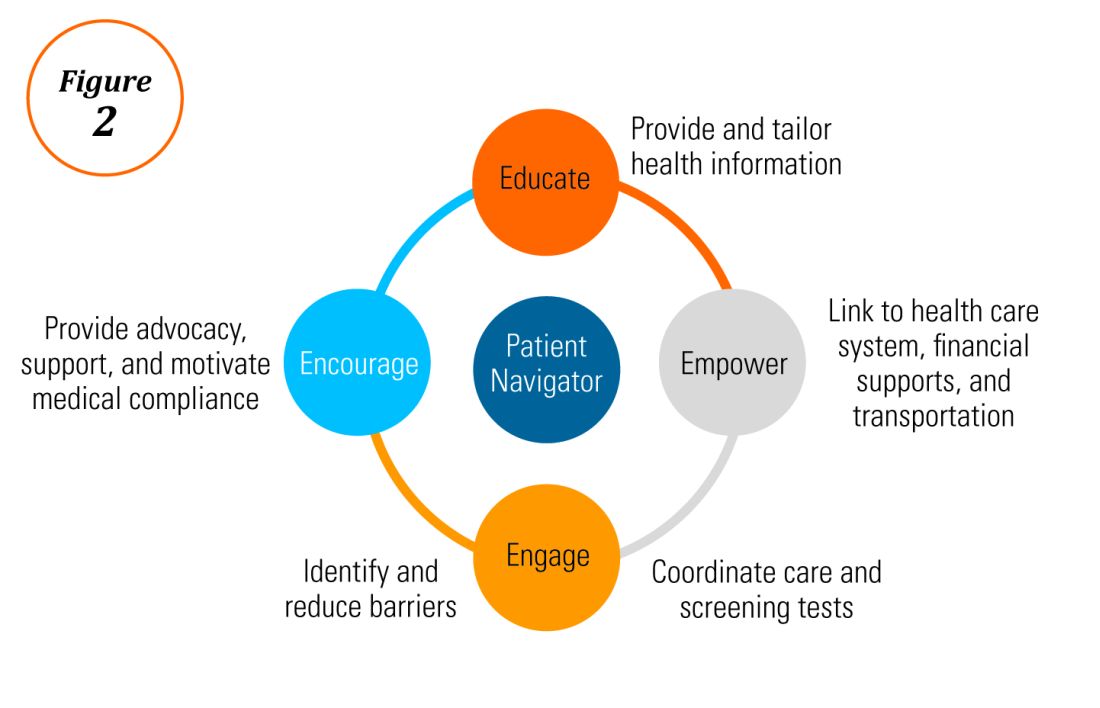

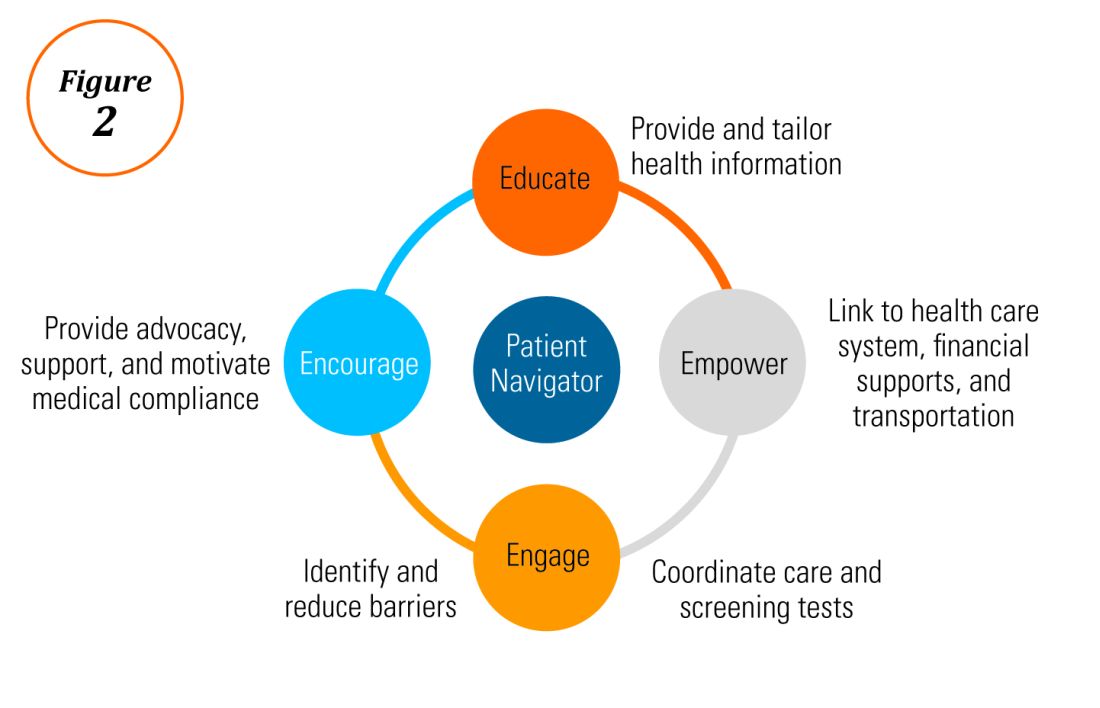

Characterization of barriers is important because it promotes the development of targeted interventions. Intervention models include community engagement programs, incorporation of fecal occult testing, and patient navigator programs.45-47 In response to the alarming disparity in CRC screening rates in Latino communities, several interventions have been set in motion in different clinical scenarios, which include patient navigation and a focus on patient education.

Randomized trials have shown that outreach efforts and patient navigation increase CRC screening rates in AAs.48,54,55 Studies evaluating the effects of print-based educational materials on improving screening showed improvement in screening rates, decreases in cancer-related fatalistic attitudes, and patients had a better understanding of the benefits of screening as compared with the cost associated with screening and the cost of advanced disease.56 Similarly, the use of touch-screen computers that tailor informational messages to decisional stage and screening barriers increased participation in CRC screening.57 Including patient navigators along with printed education material was even more effective at increasing the proportion of patients getting colonoscopy screening than providing printed material alone, with more-intensive navigation needed for individuals with low literacy.58 Grubbs et al.reported the success of their patient navigation program, which included wider comprehensive screening and coverage for colonoscopy screening.59 In AAs, they estimated an annual reduction of CRC incidence and mortality of 4,200 and 2,700 patients, respectively.

Among immigrants, there is an increased likelihood of CRC screening in those immigrants with a higher number of primary care visits.60 The intersection of culture, race, socioeconomic status, housing enclaves, limited English proficiency, low health literacy, and immigration policy all play a role in immigrant health and access to health care.61

Therefore, different strategies may be needed for each immigrant group to improve CRC screening. For this group of patients, efforts aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of national immigration policies on immigrant populations may have the additional consequence of improving health care access and CRC screening for these patients.