User login

Control of COPD Symptoms: Addressing an Unmet Need

This series for primary care physicians covers key topics in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma within the context of current national guidelines and clinical practice.

Click here to read the supplement

Randall Brown, MD, MPH, AE-C

Center for Managing Chronic Disease

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

This series for primary care physicians covers key topics in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma within the context of current national guidelines and clinical practice.

Click here to read the supplement

Randall Brown, MD, MPH, AE-C

Center for Managing Chronic Disease

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

This series for primary care physicians covers key topics in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma within the context of current national guidelines and clinical practice.

Click here to read the supplement

Randall Brown, MD, MPH, AE-C

Center for Managing Chronic Disease

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Maan A. Fares

Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: A frontier in cardiac intervention

Amar Krishnaswamy, Stephanie Mick, Jose Navia, A. Marc Gillinov, E. Murrat Tuzcu, and Samir R. Kapadia

Bioresorbable stents: The future of Interventional cardiology?

Stephen G. Ellis and Haris Riaz

Leadless cardiac pacing: What primary care providers and non-EP cardiologists should know

Erich L. Kiehl and Daniel J. Cantillon

PCSK9 inhibition: A promise fulfilled?

Khendi White, Chaitra Mohan, and Michael Rocco

Fibromuscular dysplasia: Advances in understanding and management

Ellen K. Brinza and Heather L. Gornik

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Maan A. Fares

Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: A frontier in cardiac intervention

Amar Krishnaswamy, Stephanie Mick, Jose Navia, A. Marc Gillinov, E. Murrat Tuzcu, and Samir R. Kapadia

Bioresorbable stents: The future of Interventional cardiology?

Stephen G. Ellis and Haris Riaz

Leadless cardiac pacing: What primary care providers and non-EP cardiologists should know

Erich L. Kiehl and Daniel J. Cantillon

PCSK9 inhibition: A promise fulfilled?

Khendi White, Chaitra Mohan, and Michael Rocco

Fibromuscular dysplasia: Advances in understanding and management

Ellen K. Brinza and Heather L. Gornik

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Maan A. Fares

Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: A frontier in cardiac intervention

Amar Krishnaswamy, Stephanie Mick, Jose Navia, A. Marc Gillinov, E. Murrat Tuzcu, and Samir R. Kapadia

Bioresorbable stents: The future of Interventional cardiology?

Stephen G. Ellis and Haris Riaz

Leadless cardiac pacing: What primary care providers and non-EP cardiologists should know

Erich L. Kiehl and Daniel J. Cantillon

PCSK9 inhibition: A promise fulfilled?

Khendi White, Chaitra Mohan, and Michael Rocco

Fibromuscular dysplasia: Advances in understanding and management

Ellen K. Brinza and Heather L. Gornik

Role of the Kidney in Type 2 Diabetes and Mechanism of Action of Sodium Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors

While type 2 diabetes (T2D) is commonly seen in primary care, it is difficult to manage successfully over time. This series offers brief eNewsletters written by clinical experts that are designed to assist in the clinical management of patients with T2D.

While type 2 diabetes (T2D) is commonly seen in primary care, it is difficult to manage successfully over time. This series offers brief eNewsletters written by clinical experts that are designed to assist in the clinical management of patients with T2D.

While type 2 diabetes (T2D) is commonly seen in primary care, it is difficult to manage successfully over time. This series offers brief eNewsletters written by clinical experts that are designed to assist in the clinical management of patients with T2D.

The Role of Hysteroscopy in Minimally Invasive Management of Intrauterine Health

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Linda D. Bradley, MD

Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women’s

Health Institute,

Cleveland Clinic,

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Competing Interest and Financial Disclosures: Dr. Bradley reports that she has received grant/research/clinical trial support from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc. She is a consultant and on the advisory board for Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boston Scientific Corporation, and Smith & Nephew; she is on the advisory board for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; she is on the speakers' bureau for Smith & Nephew (Medtronic); she is on the scientific advisory panel for Karl Storz; and she is on the data safety and monitoring board for Gynesonics.

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Linda D. Bradley, MD

Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women’s

Health Institute,

Cleveland Clinic,

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Competing Interest and Financial Disclosures: Dr. Bradley reports that she has received grant/research/clinical trial support from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc. She is a consultant and on the advisory board for Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boston Scientific Corporation, and Smith & Nephew; she is on the advisory board for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; she is on the speakers' bureau for Smith & Nephew (Medtronic); she is on the scientific advisory panel for Karl Storz; and she is on the data safety and monitoring board for Gynesonics.

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Linda D. Bradley, MD

Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women’s

Health Institute,

Cleveland Clinic,

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Competing Interest and Financial Disclosures: Dr. Bradley reports that she has received grant/research/clinical trial support from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc. She is a consultant and on the advisory board for Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boston Scientific Corporation, and Smith & Nephew; she is on the advisory board for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; she is on the speakers' bureau for Smith & Nephew (Medtronic); she is on the scientific advisory panel for Karl Storz; and she is on the data safety and monitoring board for Gynesonics.

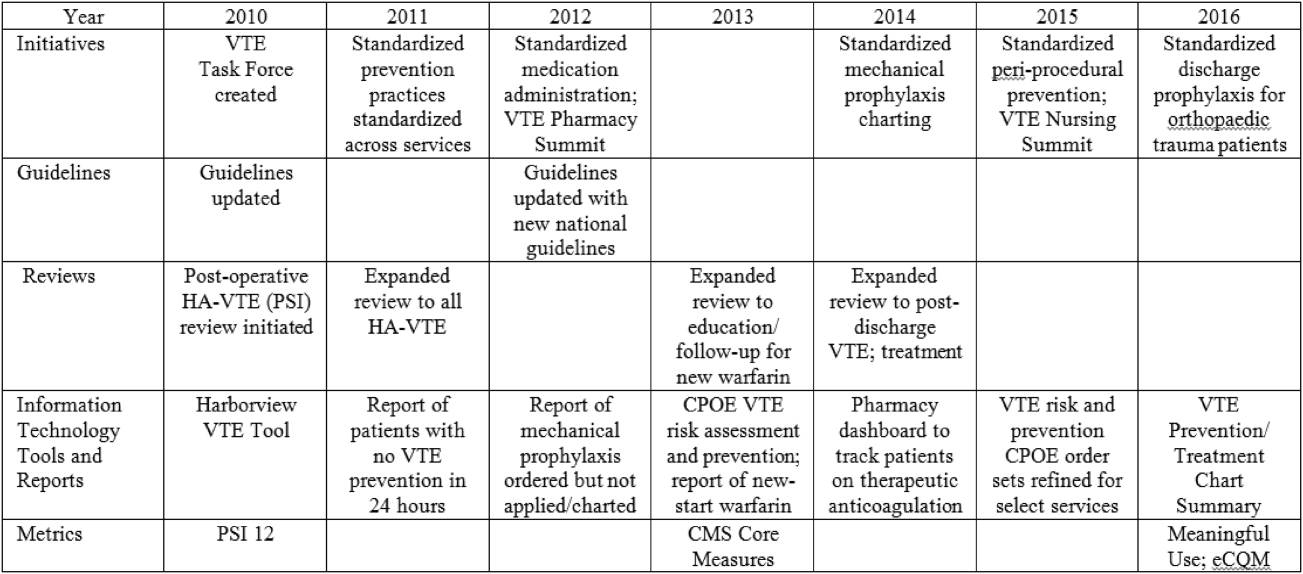

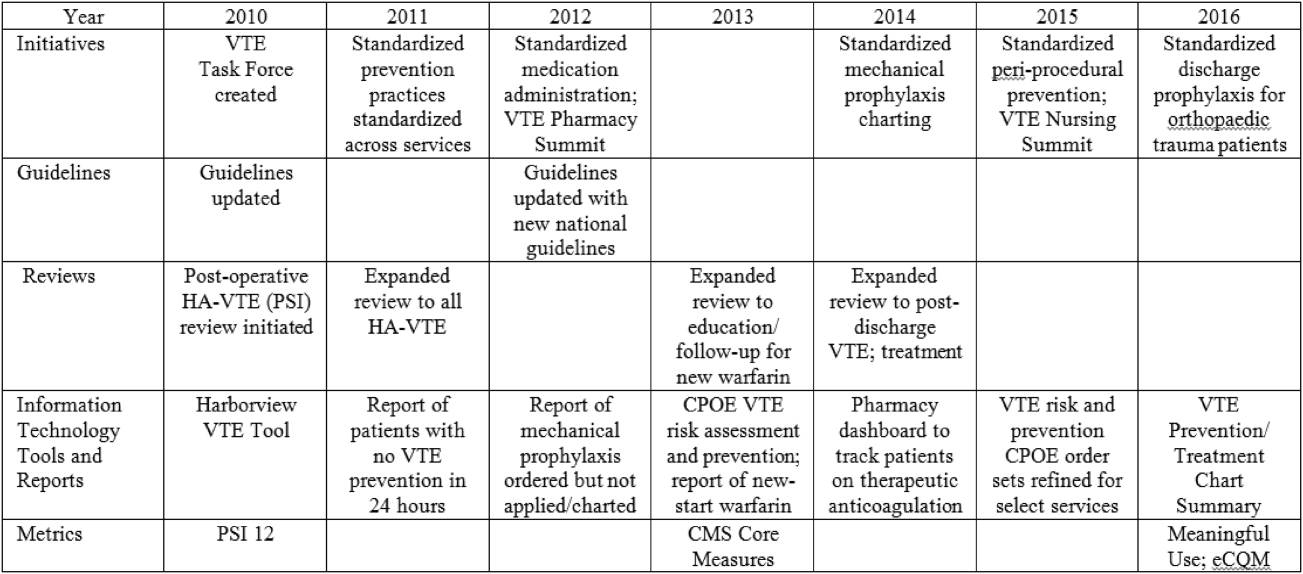

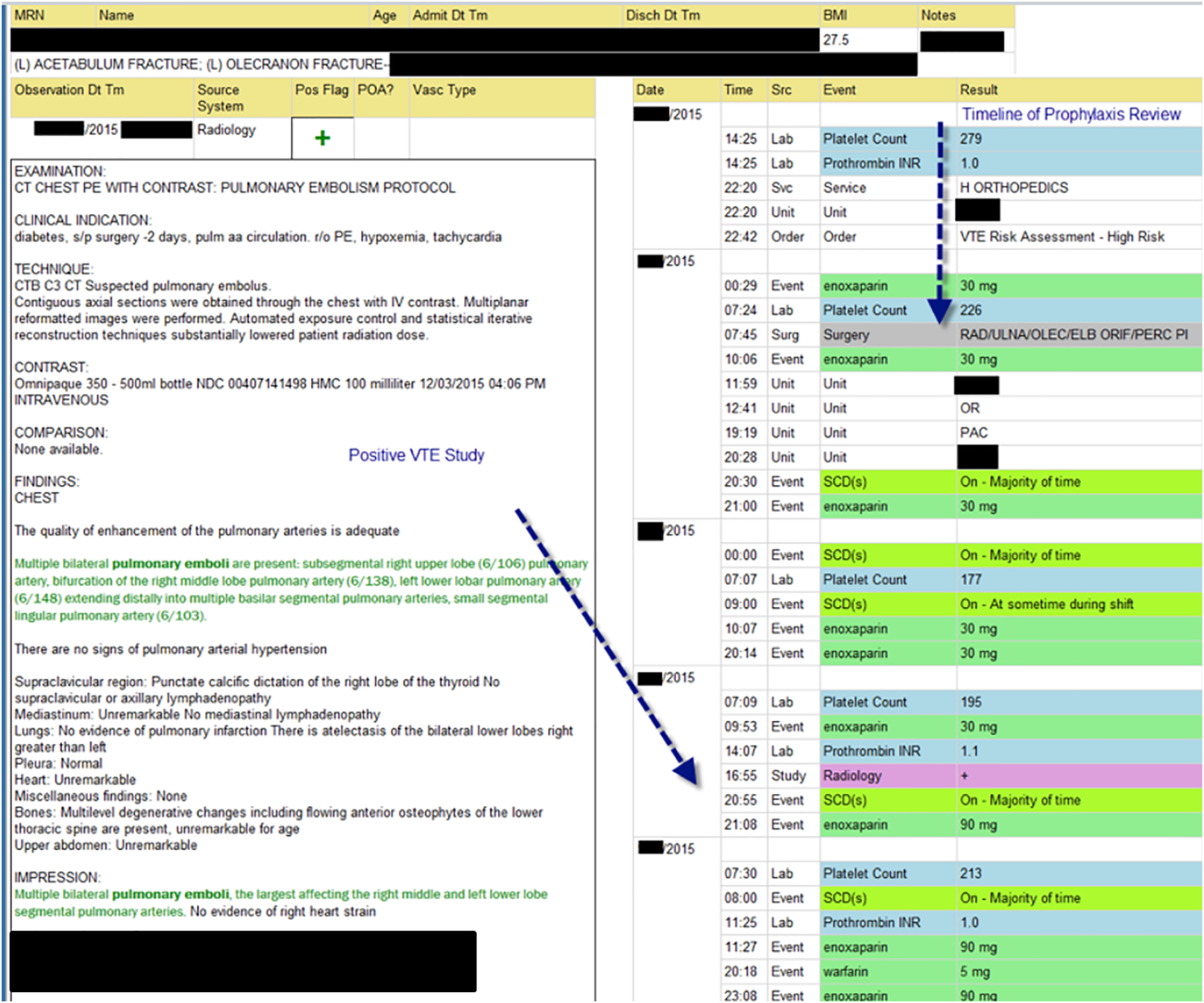

Large Healthcare System VTE Prevention

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is a major cause of preventable hospital death and long‐term morbidity. VTE accounts for approximately 100,000 to 200,000 hospital deaths annually,[1] and preventable DVT costs an estimated $2.5 billion annually, with each case resulting in direct hospital costs of an estimated $25,977.[2] Although VTE is less common in children, its incidence is increasing in the medically ill hospitalized pediatric patient. The most recent analysis of a large national children's hospital database showed VTE rates increasing from 34 to 58 per 10,000 admissions from 2001 to 2007.[3] Rates in pediatric trauma patients are higher, at 60 to 100 per 10,000 admissions.[4, 5, 6]

The Joint Commission, the Surgeon General, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have supported initiatives to increase awareness and promote strategies designed to prevent hospital acquired VTE.[7, 8] There are several high‐quality, evidence‐based VTE prophylaxis (VTE‐P) guidelines for adult hospitalized populations.[9, 10, 11] Pediatric VTE‐P guidelines are not well established, but the literature regarding VTE risk stratification and prophylaxis guidelines for medically complex children is growing.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

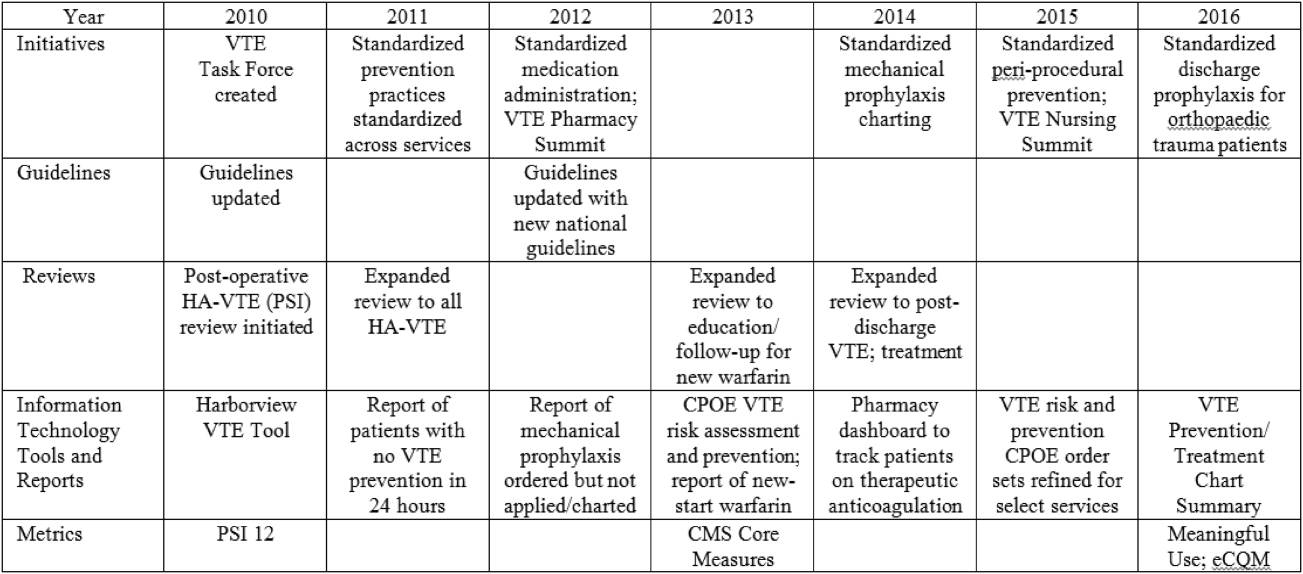

A significant challenge has been developing systems that ensure that evidence and consensus‐based care recommendations are reliably implemented. This summary will describe the methods applied across an integrated health system that includes 22 acute care facilities and 1 pediatric hospital across 5 states that have resulted in a significant reduction in preventable VTE.

SETTING

Mayo Clinic is an integrated health system that owns 22 acute care facilities across 5 states, housing 3971 beds with approximately 122,000 admissions per year. Mayo Clinic Rochester, Arizona, and Florida are all tertiary academic medical centers with trauma and transplant programs. During this project, Arizona and Florida utilized a common build of the Cerner (Kansas City, MO) electronic health record (EHR). The other facilities, collectively referred to as the Mayo Clinic Health System (MCHS) hospitals, include 1 level II trauma center and 11 critical access hospitals and serve communities of varying sizes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. A different build of the Cerner EHR served the MCHS during this project.

Mayo Clinic Rochester is responsible for nearly 50% of all admissions and procedures. Mayo Eugenio Litta Children's Hospital, Rochester, Minnesota is a tertiary children's hospital facility housing 44 general pediatric beds, 26 neonatal intensive care unit beds, 24 intermediate nursery special care beds, and 16 pediatric intensive care unit beds. Mayo Clinic Rochester used the GE Centricity (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) EHR and custom‐designed computerized decision support.

METHODS

Mayo Clinic has developed a system to deliberately speed the diffusion of best practices across our system to drive reliable, evidence‐based care, reduce unwanted variation in processes and outcomes, and improve value.[18] The 3 main components of this system are (1) discovery: wherein we learn a practice that demonstrably solves the clinical problem well in at least 1 of our facilities, (2) assessment of readiness for diffusion, and (3) diffusion of the best practice across all of Mayo Clinic. The diffusion process is active and equipped with a project team and execution timeline. Both adult and pediatric projects began with discovery phases. The adult program has fully diffused; the pediatric program is diffusing at this writing.

ADULT ACUTE CARE PATIENTS

Discovery Through Pilot Projects

Beginning in 2006, 2 spontaneously convened interdisciplinary teams worked independently in selected medical and surgical practices in our Rochester hospital to improve VTE‐P. Each team's work resulted in the reduction of defect rates on pilot hospital services to <10%. Key findings were: (1) the vast majority of patients in the pilot had at least 1 risk factor for VTE and (2) when physicians explicitly determined a VTE‐P plan, they made the correct decision 98% of the time without any specific risk rule or point system.[18] Both teams found that efforts to ensure declaration of VTE‐P plans in the workflow of admission resulted in the most improvement in appropriate VTE‐P rates.

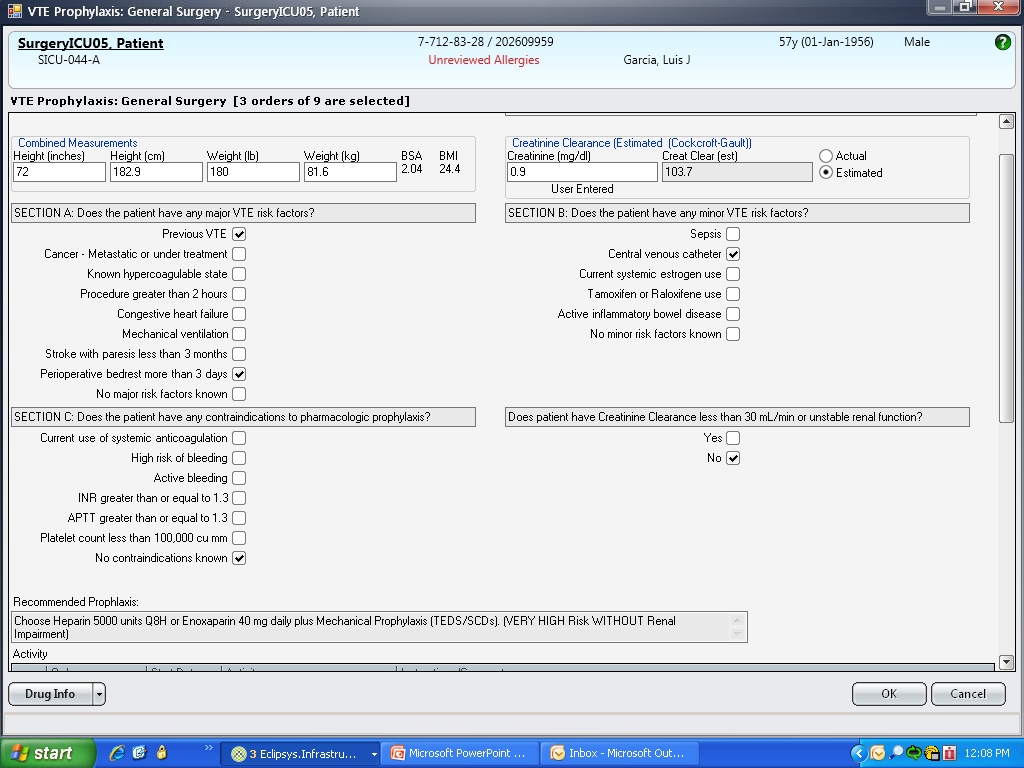

Creation of VTE‐Prevention Plans and the VTE Prophylaxis Tollgate

Based on lessons learned from the pilot projects, multidisciplinary improvement teams focused on adaptation of optimal VTE‐P plans for individual practices (eg, preferred VTE‐P for a neurosurgery patient is not the same as for a medical patient), and a VTE‐P tollgatea requirement for providers to complete a VTE‐P plan for each patientwas integrated into the clinical workflow of all order sets used for admissions, transfers, and for selected postoperative order sets. As we moved from the paper systems to computerized order entry, tollgates were subsequently converted to the GE Centricity electronic environment. To minimize burden on clinicians, designs were tested in a usability laboratory prior to operational deployment to ensure that they were as clear and easy as our software would allow.

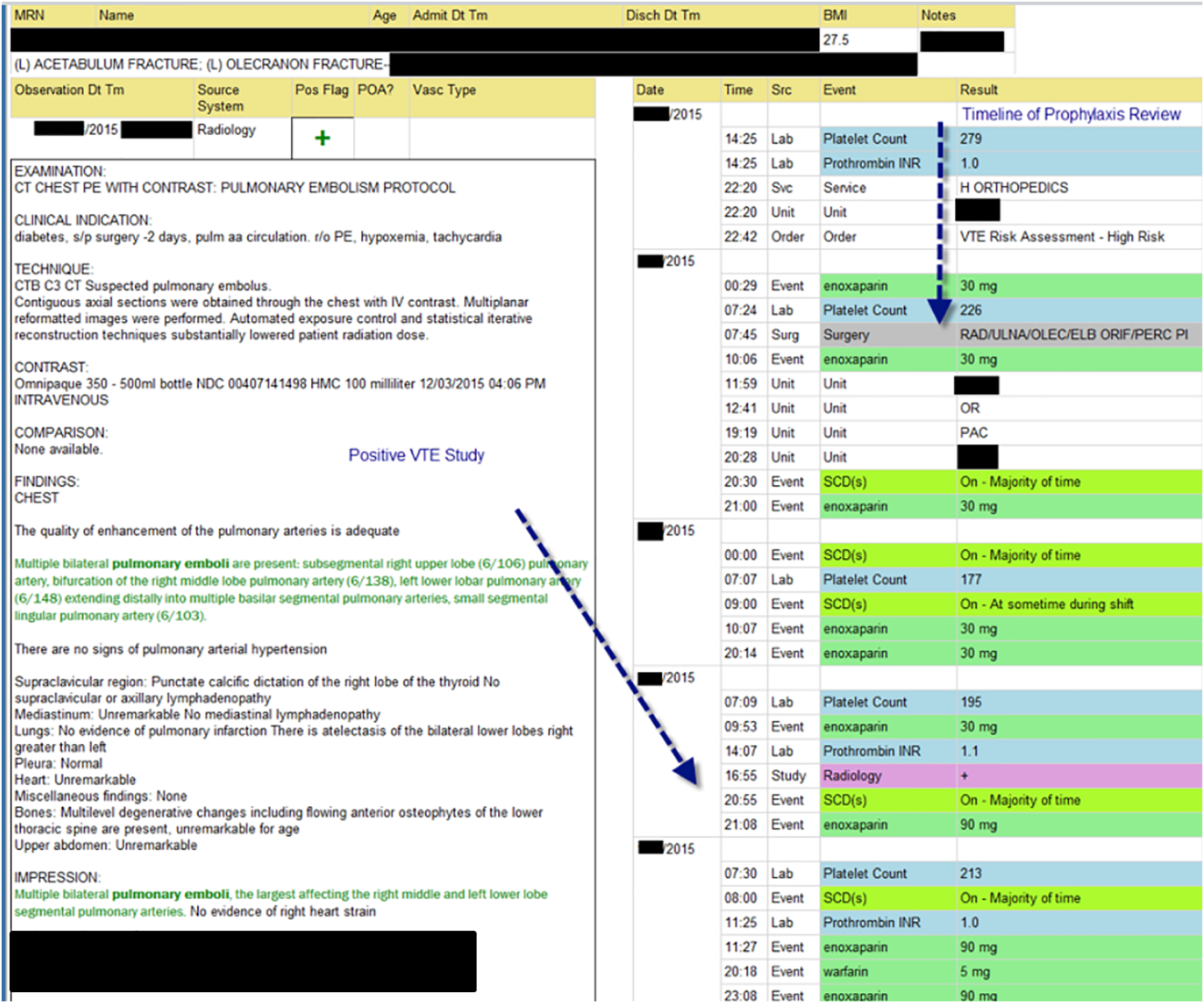

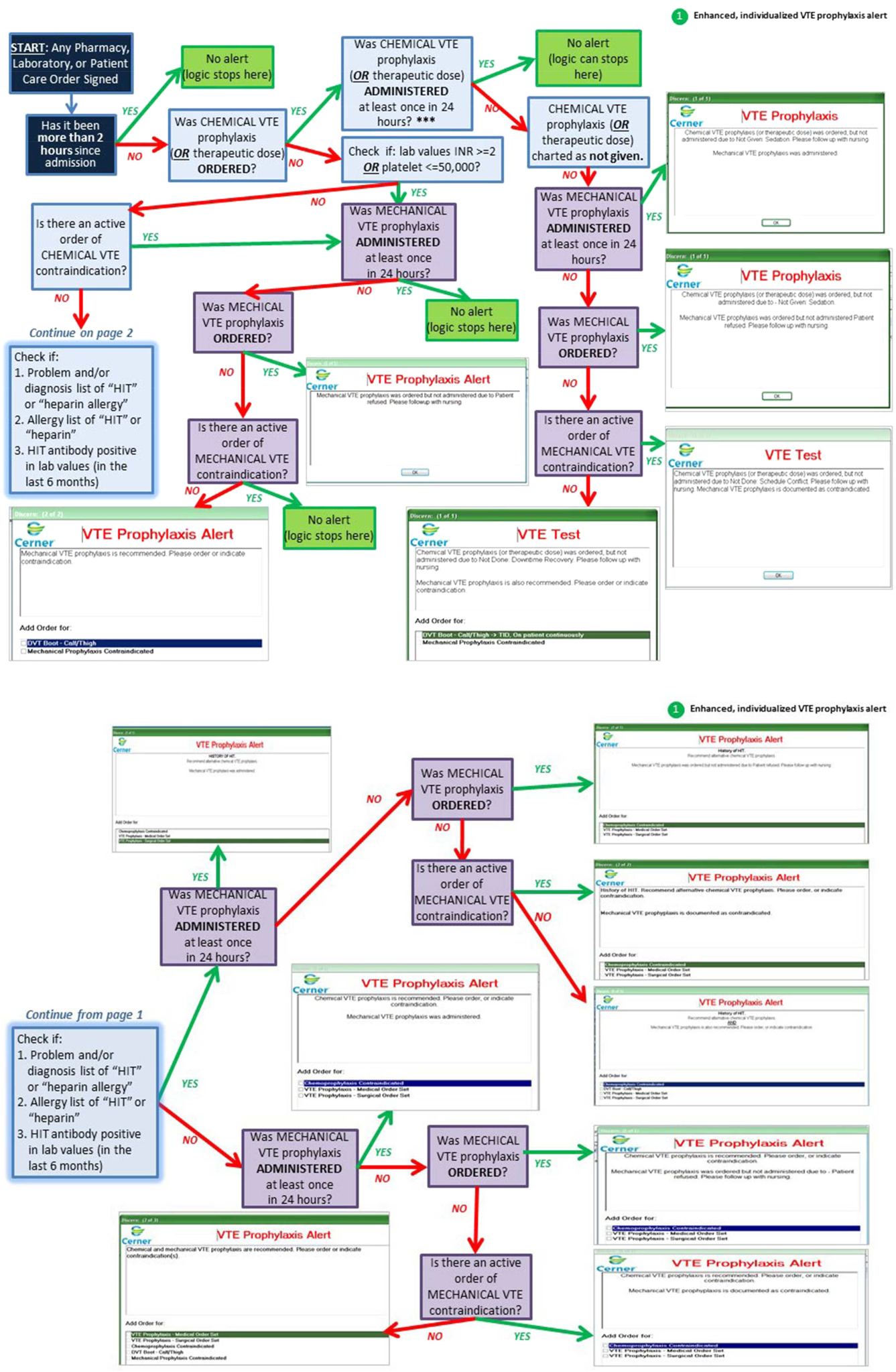

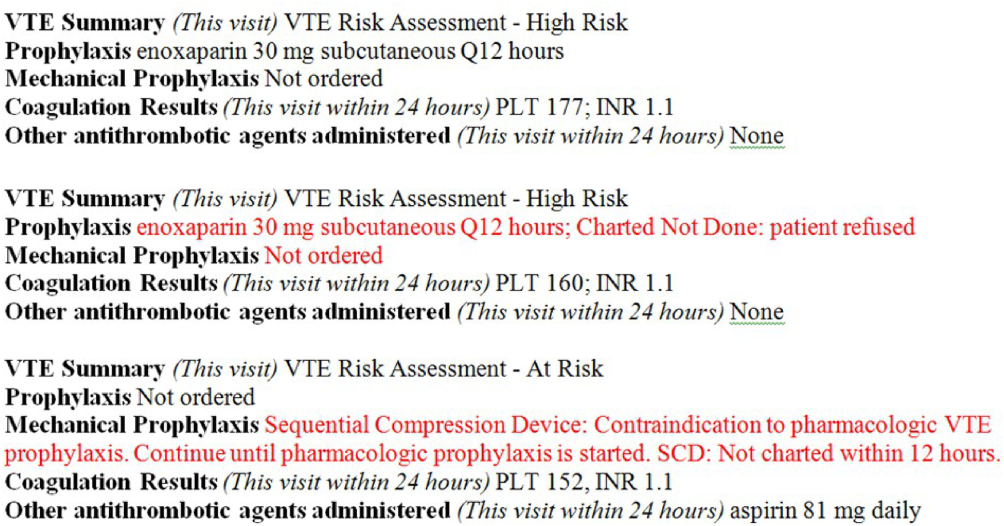

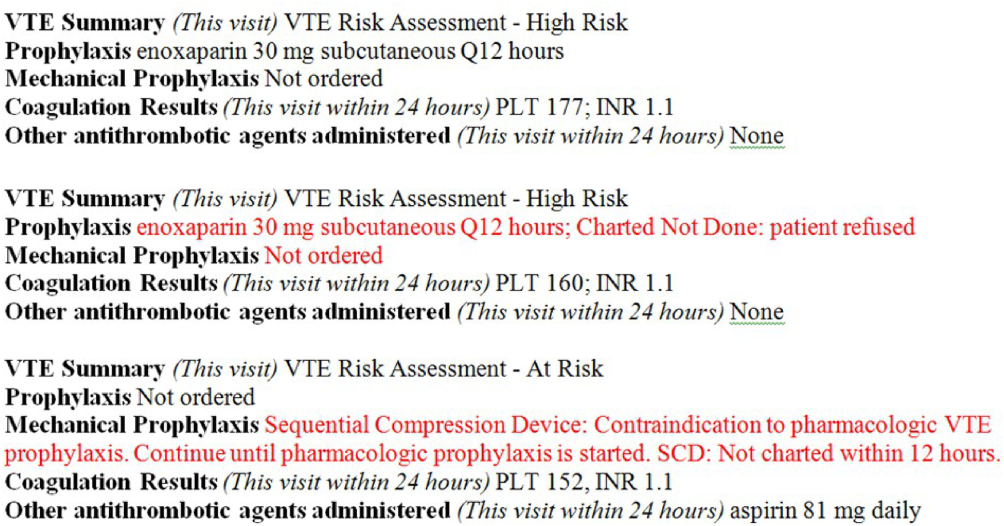

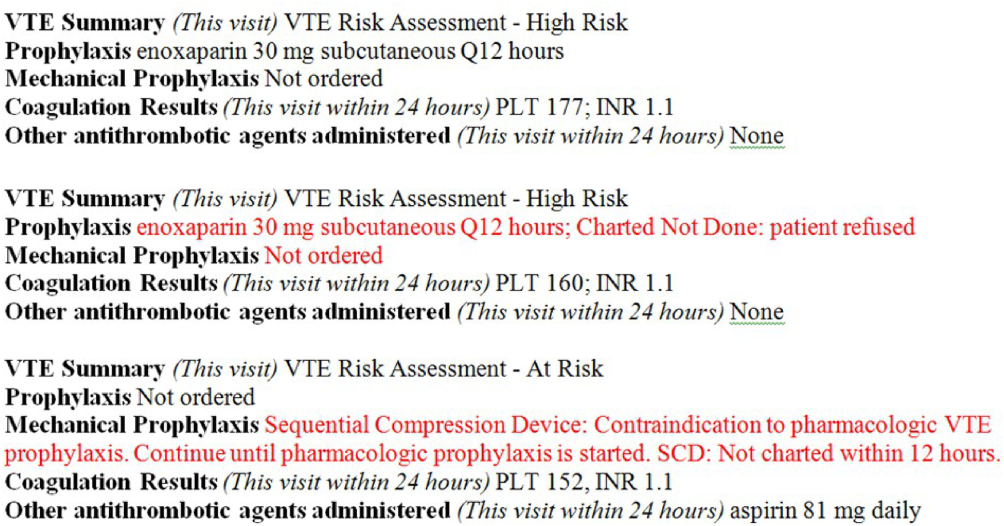

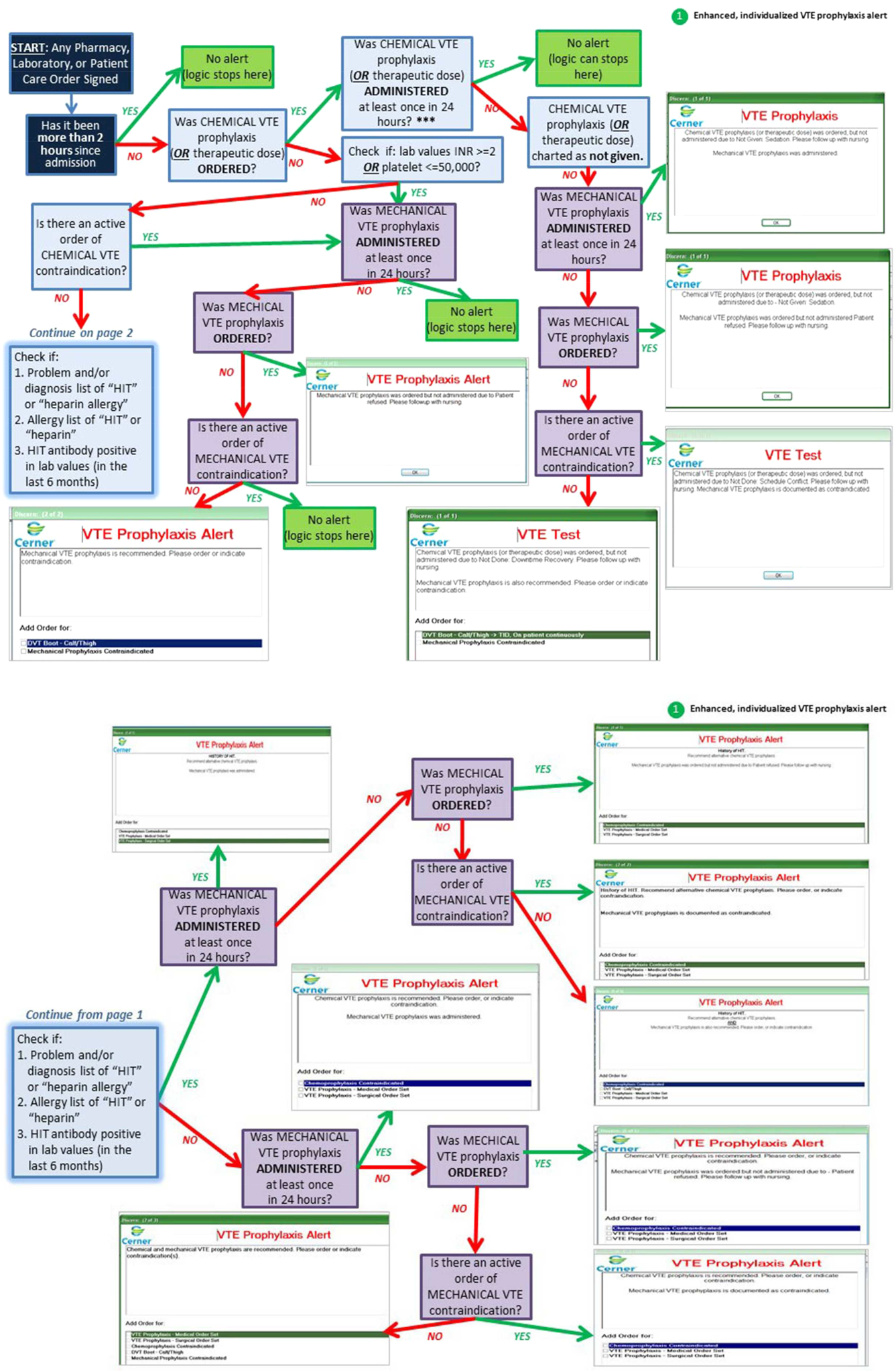

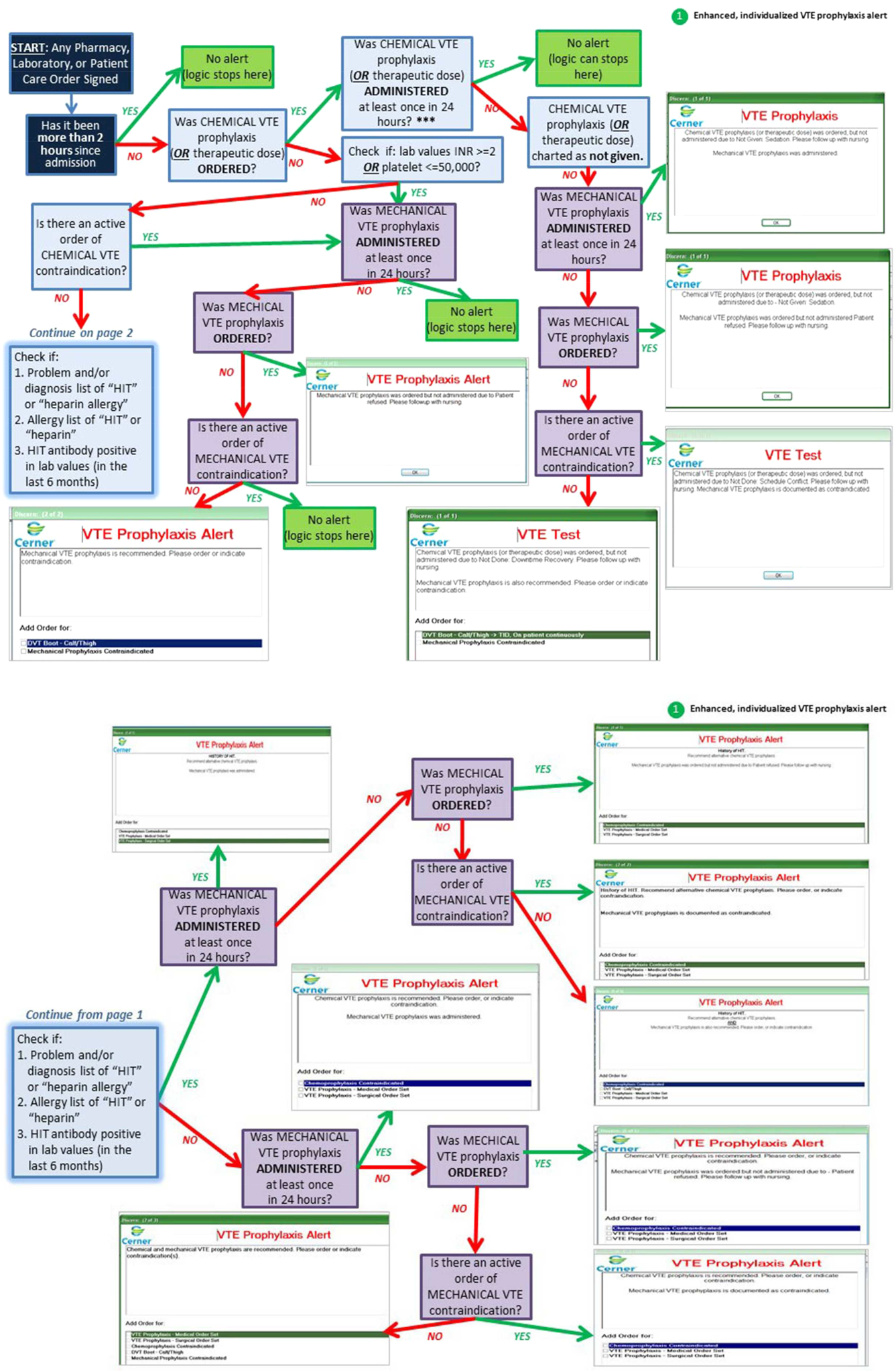

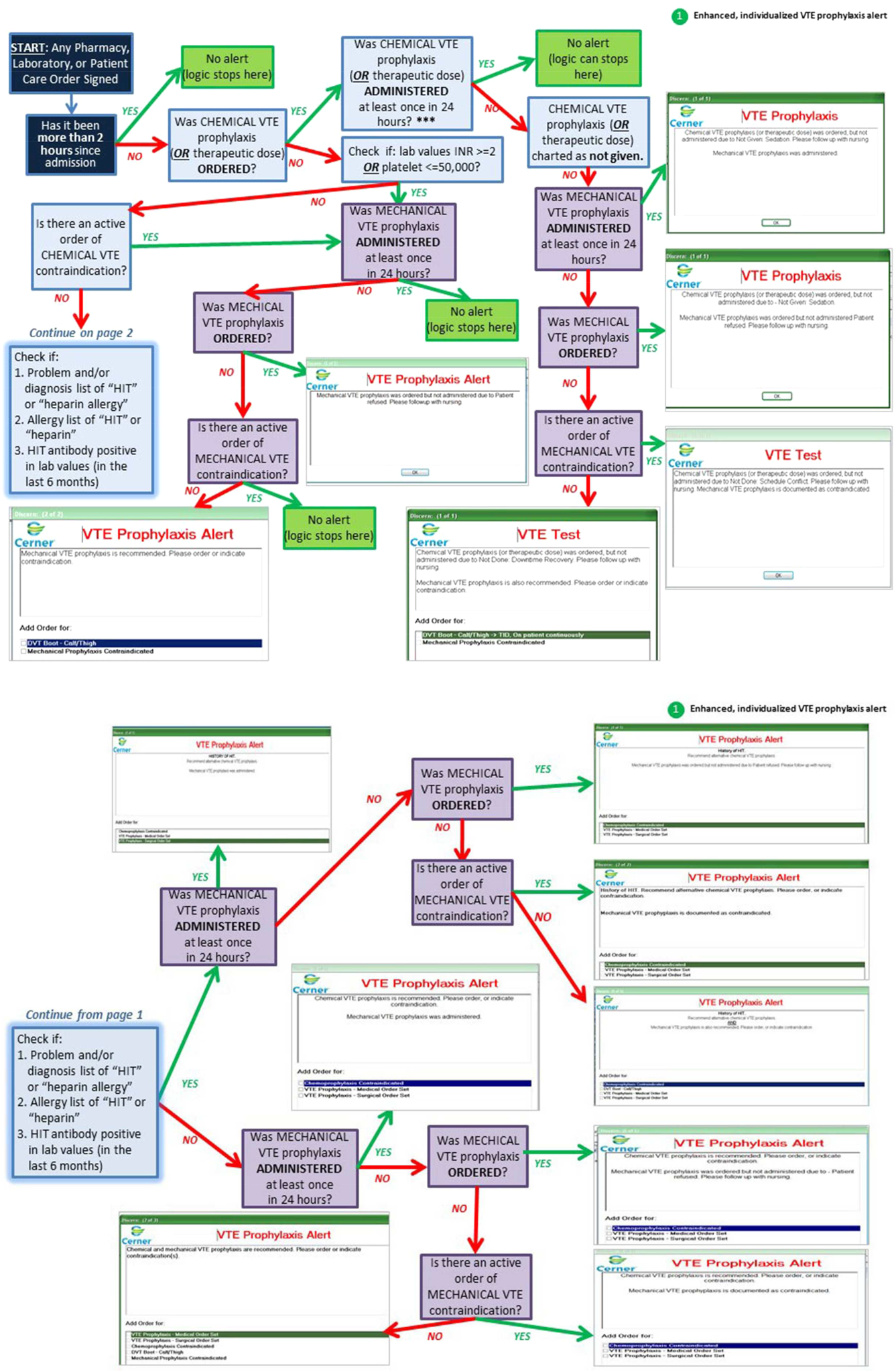

Alerts

Based on initial reports and feedback, our clinical decision support (CDS) team designed alerts that notify the clinician when (1) any patient previously declared as at least moderate risk for VTE did not have a valid VTE‐P plan in place for any 24‐hour period, or (2) when any patient carried a low‐risk categorization for >3 days (because this should prompt reconsideration of risk status). Alerts were designed to be clear and to facilitate steps to correct the situation.

VTE‐P alerts would present to any member of the patient's provider team who accessed the patient's EHR, and would continue to alert with each access until conditions were rendered to satisfy the requirements of the alert. Each alert provided easy access to an abbreviated VTE‐P tollgate order that would allow the provider to select a clinically appropriate response: either restate the low‐risk status, change the low‐risk status and add an active VTE‐P order, specify why neither mechanical nor pharmacologic VTE‐P may be given, or restart a VTE‐P order.

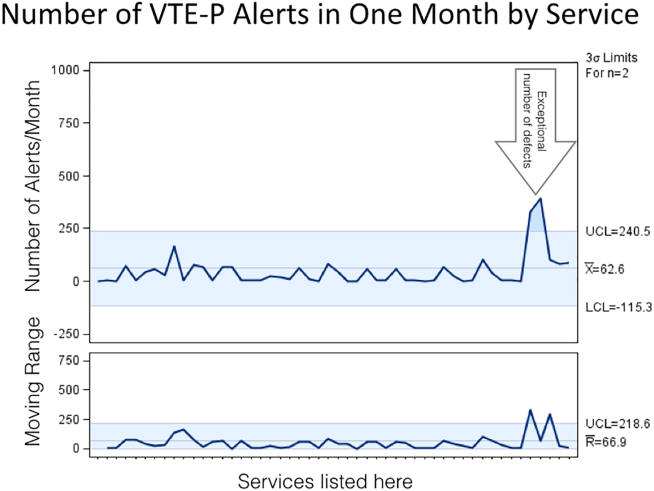

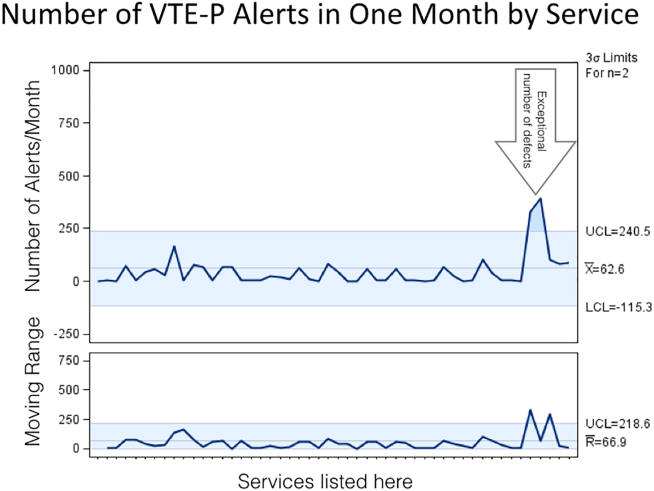

Monitoring

Both process and outcome measures were used to monitor the effectiveness of VTE‐P activities. During initial roll‐out, the teams measured and reported the proportion of patients where either (1) VTE risk factors were present (patient is determined to be at least at moderate risk for VTE) and either pharmacologic or mechanical VTE‐P was ordered within 24 hours of admission, or (2) VTE risk factors were not present, and VTE‐P not indicated was documented within 24 hours of admission. The CDS system also provided ongoing monitoring of CDS‐alert firing frequency, which closely correlated with the prevalence of patients without a valid VTE‐P plan.

Diffusion Across All Units of Mayo Rochester

Diffusion teams included physician champions, project managers, a pharmacist, and a nurse. To emphasize the engagement of institutional leadership, the project was commissioned by the institution's Clinical Practice Quality Oversight Committee and co‐chaired by the Department of Medicine Associate Chair for Quality and the Chair of the Surgical Quality and Safety Subcommittee.

Implementation of this integrated system resulted in substantial improvement to 97% hospital‐wide VTE‐P rates that were sustained over 3 quarters. At that time, a decision was made to diffuse this new best practice across all Mayo Clinic acute care facilities.

Diffusion to All 22 Mayo Clinic Acute Care Facilities

After readiness for diffusion assessment,[18] an enterprise diffusion team, this time led by the Mayo Clinic Patient Safety Officer (an MD), 3 other physician champions (1 from each region of the Mayo Clinic), a project manager, a pharmacist, a computerized physician order entry system content specialist, and the institutional quality office personnel who assisted with the measurement, analysis, and display of data at the work sites. The best practices diffused were: (1) All admission or transfer order sets will have a VTE‐P tollgate. (2) All VTE‐P tollgates will be a force function (ie, they cannot be bypassed). (3) Over 95% of all eligible patients in the facility at any given moment will have a valid VTE‐P plan in place. (4) Ongoing compliance monitoring must be available as an automatic feed, not by chart review. The end goal of our diffusion process was to ensure that all best practices were ensured at all of our facilities.

Key issues in the diffusion process included implementation of the VTE‐P tollgates into all admission or transfer order sets and the computer decision support logic that had been developed in the GE Centricity system into the Cerner EHR. Each system had slightly different constraints to 4 best practices to be diffused. We had difficulty designing the GE Centricity order sets or flags in such a way that absolutely forced an action (best practice items 1 and 2). Instead, our design had to alert the ordering provider until the appropriate conditions were met. This is suboptimal in that it creates the potential for alarm fatigue and subsequent error. It is for that reason that a tight monitoring system was necessary to provide feedback on a per‐provider level if the alerts were too numerous (suggesting that alarm fatigue or misunderstanding might be leading to failure to correct the unsafe situation producing the alarm).

In contrast, the Cerner system did not have as much capability for our IT support to provide as much customization of decision support but was fully capable of forcing functions. Therefore, we needed to provide a more rigid logic into the order sets. This led to a less than optimal user interface each time a patient was admitted or transferred, but fulfilled mission goals.

Pediatric Patients

Pediatric Discovery Project

Development of Pediatric VTE Risk‐Assessment Tool

To develop a VTE‐P system for our pediatric hospital, our first task was to design a VTE risk‐stratification tool. The improvement team included a physician, pharmacist, and clinical nurse specialists from pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), cardiac intensive care units, and general pediatric services. A literature review identified the most common published risk factors for VTE in children. We next performed a retrospective review of pediatric hospital‐acquired VTE in 2011 to 2012. Eight VTEs were identified (infants to age 18 years). All were related to central venous catheters, sepsis, congenital heart disease, leukemia, myocarditis, and extreme prematurity (Table 1). In contrast to other series, our patients were younger (80% less than 14 years of age). Based on these reviews and iterative consensus with our pediatric staff, an initial pediatric VTE risk‐screening tool was designed and piloted first in the PICU for usability and to assess face validity.

| Age/Gender | Main Diagnosis | Comorbidities | Central Lines Prior to VTE Event | VTE Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| 18 y/M | Congenital heart disease | Heart transplant | Right and left IJV, right arterial, left femoral vein and artery | DVT left IJV, innominate, subclavian, axillary veins |

| 3 y/M | Idiopathic myocarditis | ECMO | Left radial arterial, right brachial PICC, RIJ venous, left arterial femoral, right venous femoral, | Cerebral embolism with multiple infarcts |

| 0.2 y/F | Premature | NEC | Right IJ PICC | Right axillary, subclavian DVT, left greater saphenous vein |

| 0.5 y/M | Premature | Hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy | Umbilical artery and vein catheters, right IJ PICC, right femoral venous | IVC thrombosis and bilateral renal veins |

| 0.1 y/F | Sepsis | RSV pneumonia | Right femoral venous | Right common femoral and right external iliac DVT |

| 12 y/M | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Renal dysfunction | Left femoral arterial, right femoral venous | Right common femoral DVT |

| 0.1 y/M | Congenital heart disease | Umbilical artery and vein catheters, left femoral artery, right IJV | Left femoral artery thrombosis | |

| 1 y/M | Seizures | Partially treated meningitis/hyponatremia | Left femoral vein | Left common femoral and external iliac DVT |

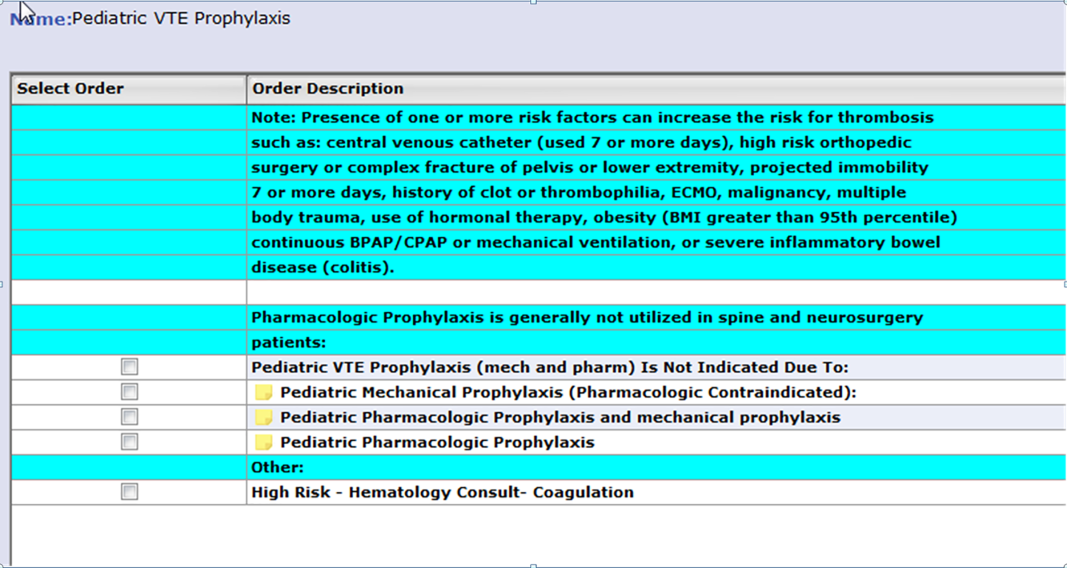

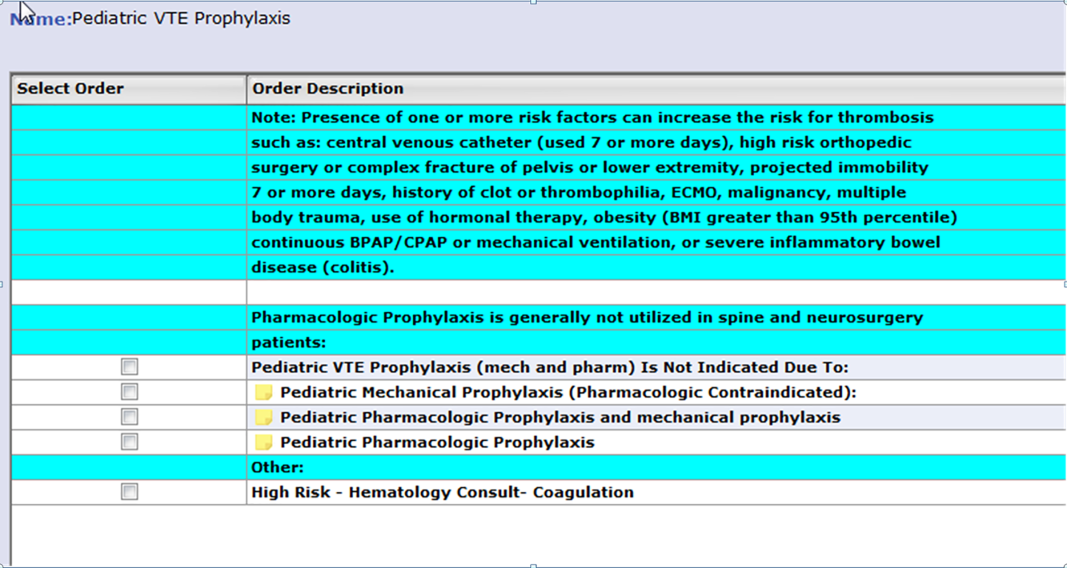

Developing Consensus About Appropriate VTE‐P

The risk of even low‐dose anticoagulation may be higher in children than in adults. Therefore, in addition to first estimating the risk for VTE, we also incorporated into the risk‐assessment tool an estimate of risk for bleeding (Table 2). Physicians were responsible for using the VTE‐P screening. Bleeding risk‐assessment categories included: intracranial bleed, premature infant, internal injury (eg, organ injury, splenic laceration), planned surgery within 24 hours, renal failure, liver dysfunction, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia (eg, platelets <50,000), disseminated intravascular coagulation, congenital bleeding disorder, and neurosurgical and spine fusion patients. If any of these were present, pharmacologic prophylaxis was contraindicated. If a patient was considered at risk for VTE, a pediatric hematology consult was recommended or advised. If there was no increased bleeding risk and the child had 2 or more risk factors or a central venous catheter with additional thrombosis risk factors, the consensus was to use appropriately dosed low‐molecular‐weight heparin or unfractionated heparin in addition to mechanical prophylaxis. A patient considered at increased risk for bleeding but with risk factors for thrombosis would receive early ambulation and/or mechanical prophylaxis. In all cases, removal of central catheters was recommended within 72 hours if possible.

|

| Risk factors |

| Central venous catheter 7 days |

| High‐risk orthopedic surgery |

| Complex fracture of pelvis or lower extremity |

| Projected immobility for 7 days |

| History of prior VTE |

| History of prior thrombophilia |

| ECMO |

| Malignancy |

| Multiple body trauma |

| Use of hormonal therapy |

| BMI > 95th percentile |

| Continuous BPAP/CPAP or mechanical ventilation |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Guidance if no increased bleeding risk |

| 2 risk factorsmechanical combined with pharmacologic prophylaxis |

| Central venous catheter 7 days and additional thrombosis risk factorsmechanical combined with pharmacologic prophylaxis |

| Pharmacologic prophylaxis generally not utilized in spine or neurosurgery patients |

| Guidance if increased bleeding risk |

| 2 risk factors or central venous catheter and additional thrombosis risk factors 7 days hematology consult |

| 2 risk factors or central venous catheter 7 days and additional thrombosis risk factorsearly ambulation + mechanical VTE‐P |

Pilot Implementation

We initiated use of the risk‐assessment tool and VTE‐P algorithm in the PICU using a paper system at first, and measured via chart review (1) the proportion of patients for whom a VTE‐P risk assessment was completed according to the recommended plan and (2) the proportion with the appropriate VTE‐P plan selected based upon risk factors present. The risk‐assessment tool was iteratively improved and built into the electronic order system (Table 2). This would ensure diffusion across the children's hospital, and would be subsequently diffused across the rest of Mayo Clinic.

Metrics

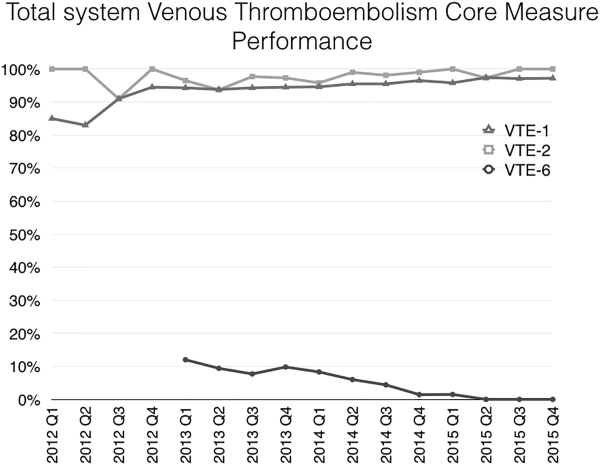

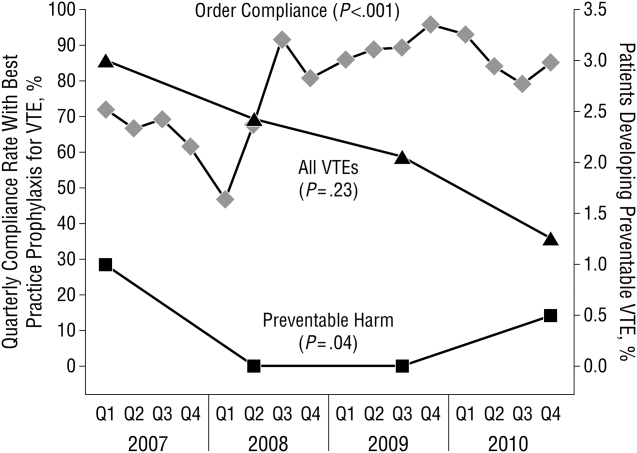

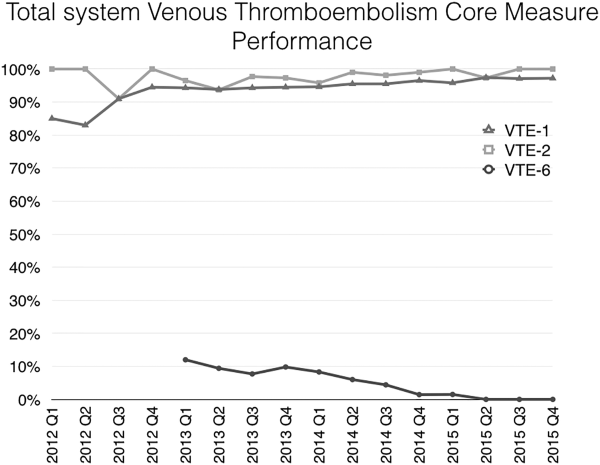

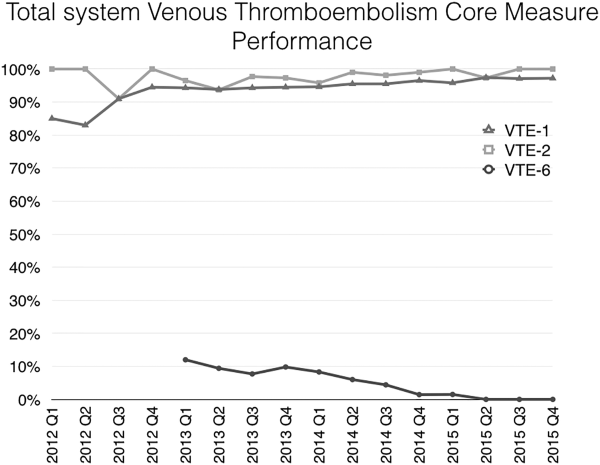

During the system diffusion for the adult system, we relied on 2 metrics to measure improvement: the CDS alert frequency and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) VTE Core Measures. The CDS alert frequency is cross‐sectional and can be used to estimate what percentage of patients at any given moment in time in our hospital have a valid VTE‐P. From chart audits, we anticipate that at target, approximately 4% of patients would generate CDS alerts because needs and plans change in the dynamic care environment. For example, VTE‐P may be held for a procedure, or during transition from 1 to another unit. Or, observation patients may have been classified as low risk, but when converted to admission status there may be a lag while the VTE risk status is changed. These data can be provided by service and provider, and are reported back to the providers to help reduce practice variation.

In addition, the CMS Core Measures provided a manual chart review metric to supplement the automated data. VTE‐1 and VTE‐2 measures the proportion of sampled charts demonstrating either delivery of VTE‐P or declaration of low risk in non‐ICU and ICU patients, respectively. VTE‐6, the proportion of patients acquiring a VTE who did not receive prophylaxis, served as our outcome measure. For the pediatric efforts, manual chart review served during the improvement pilots, but will be supplanted by a similar automated system.

RESULTS

Adult Acute Care Patients

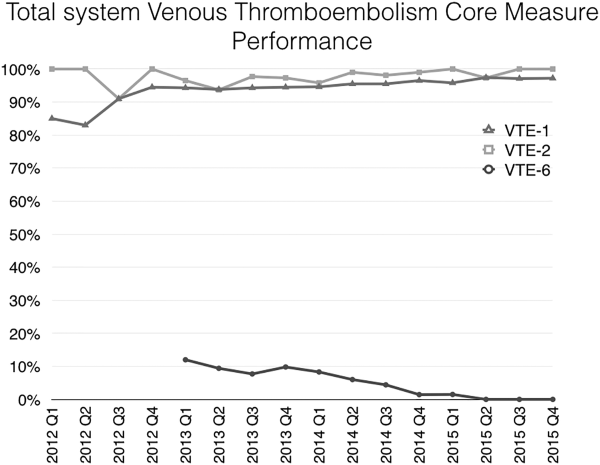

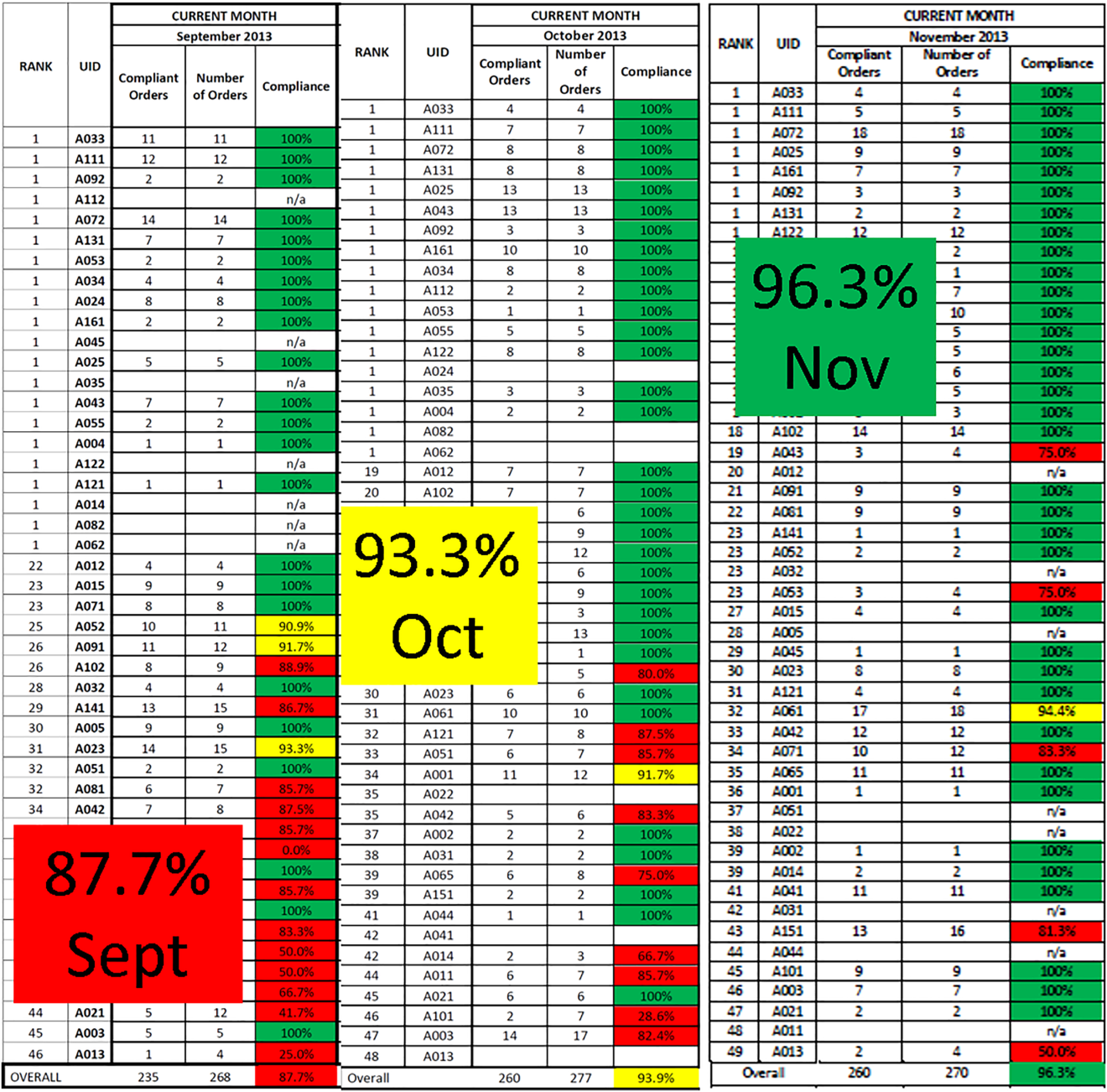

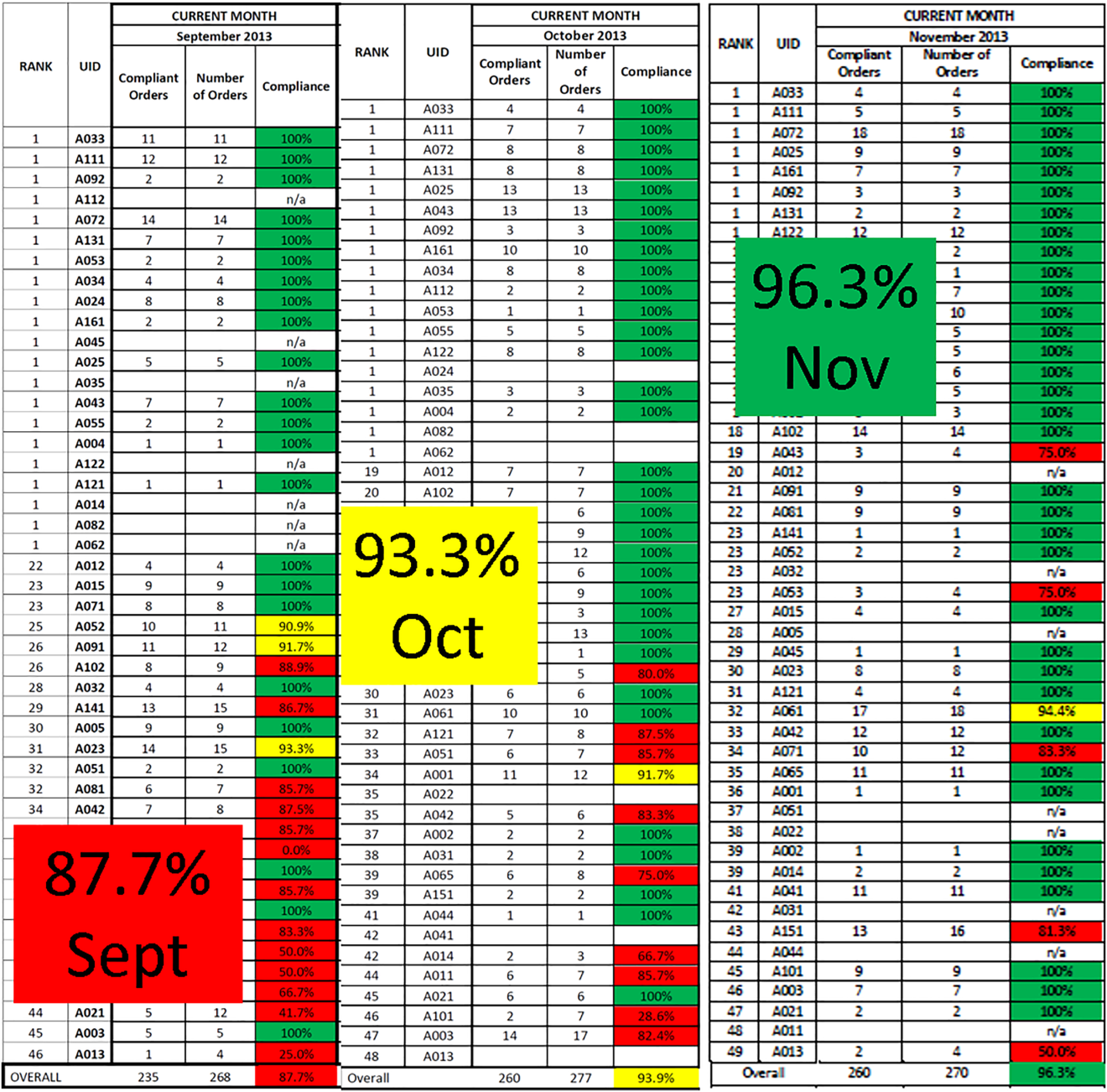

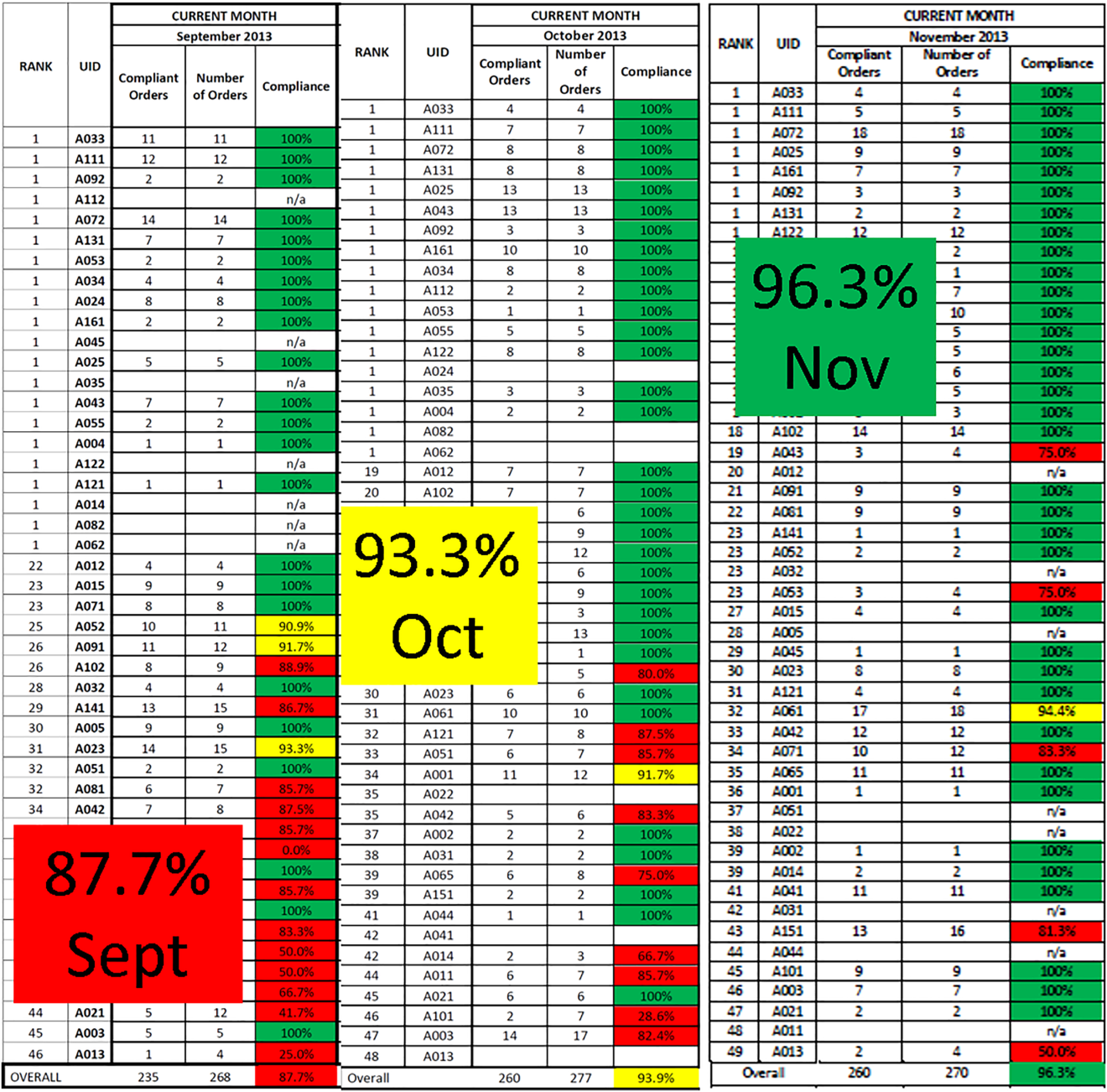

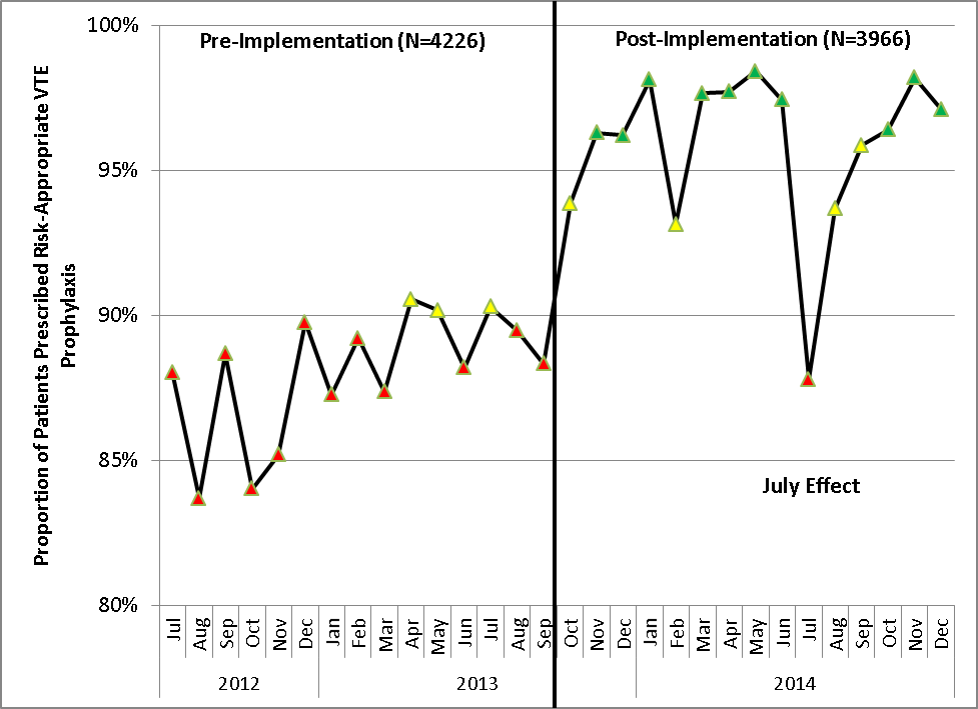

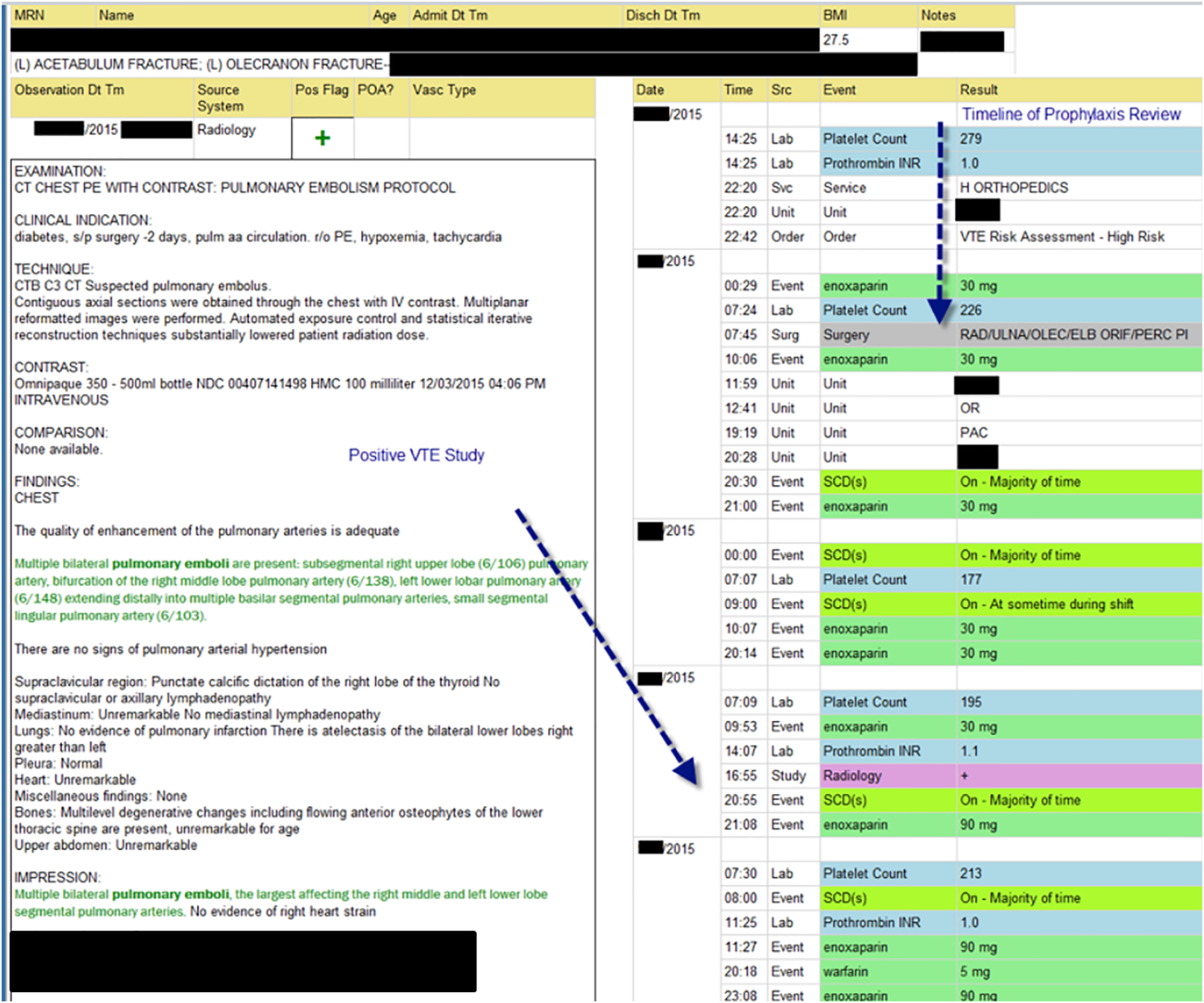

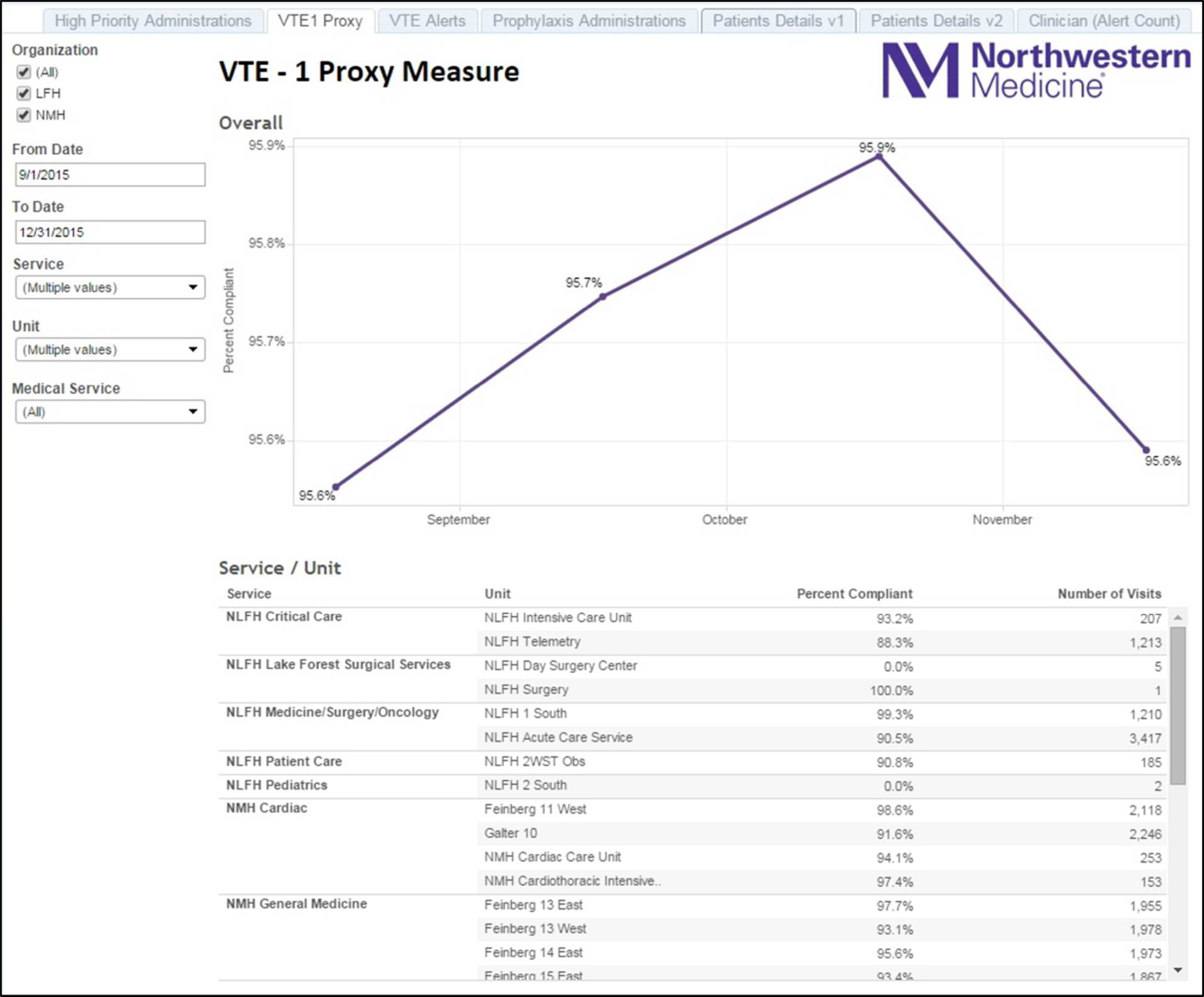

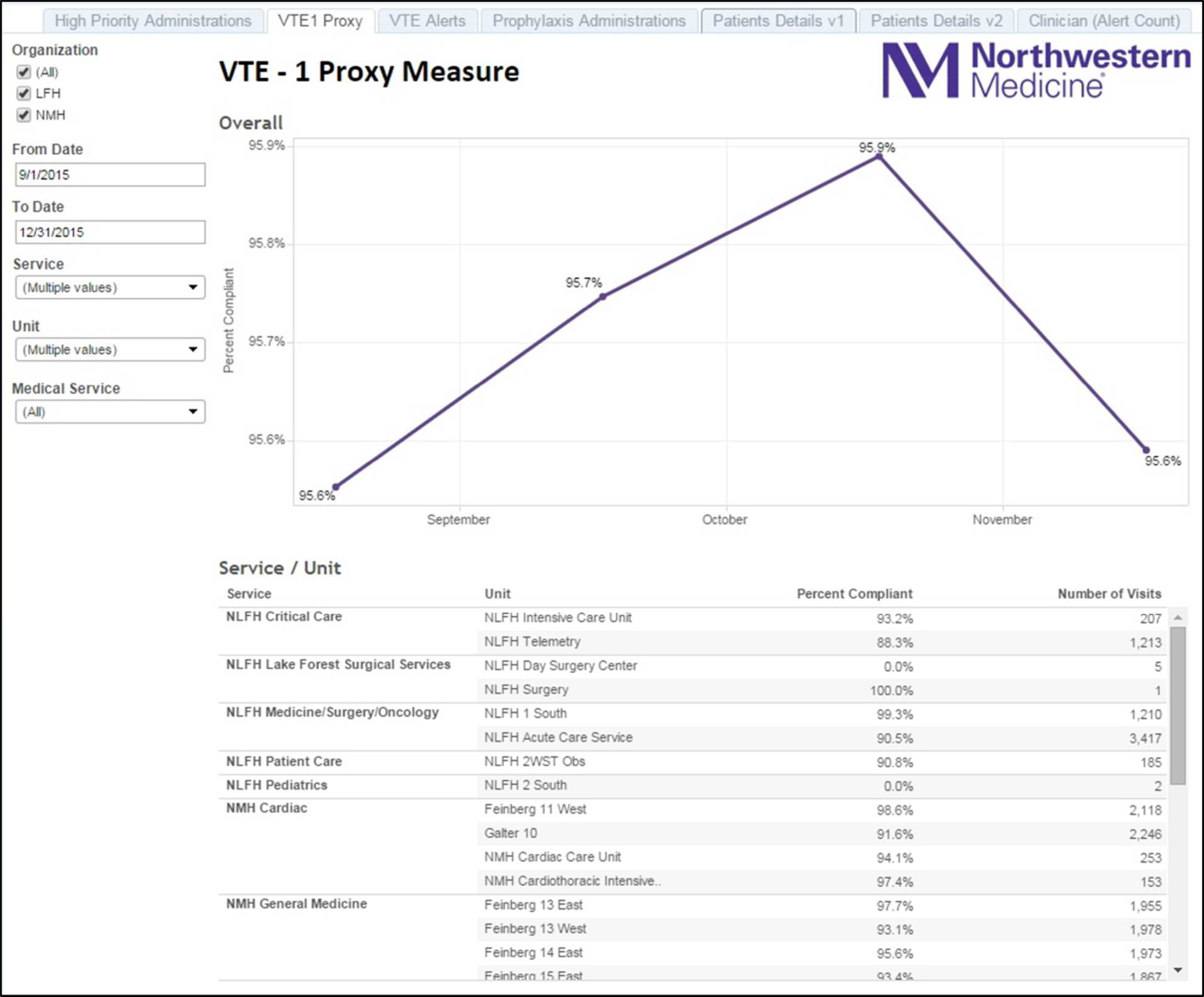

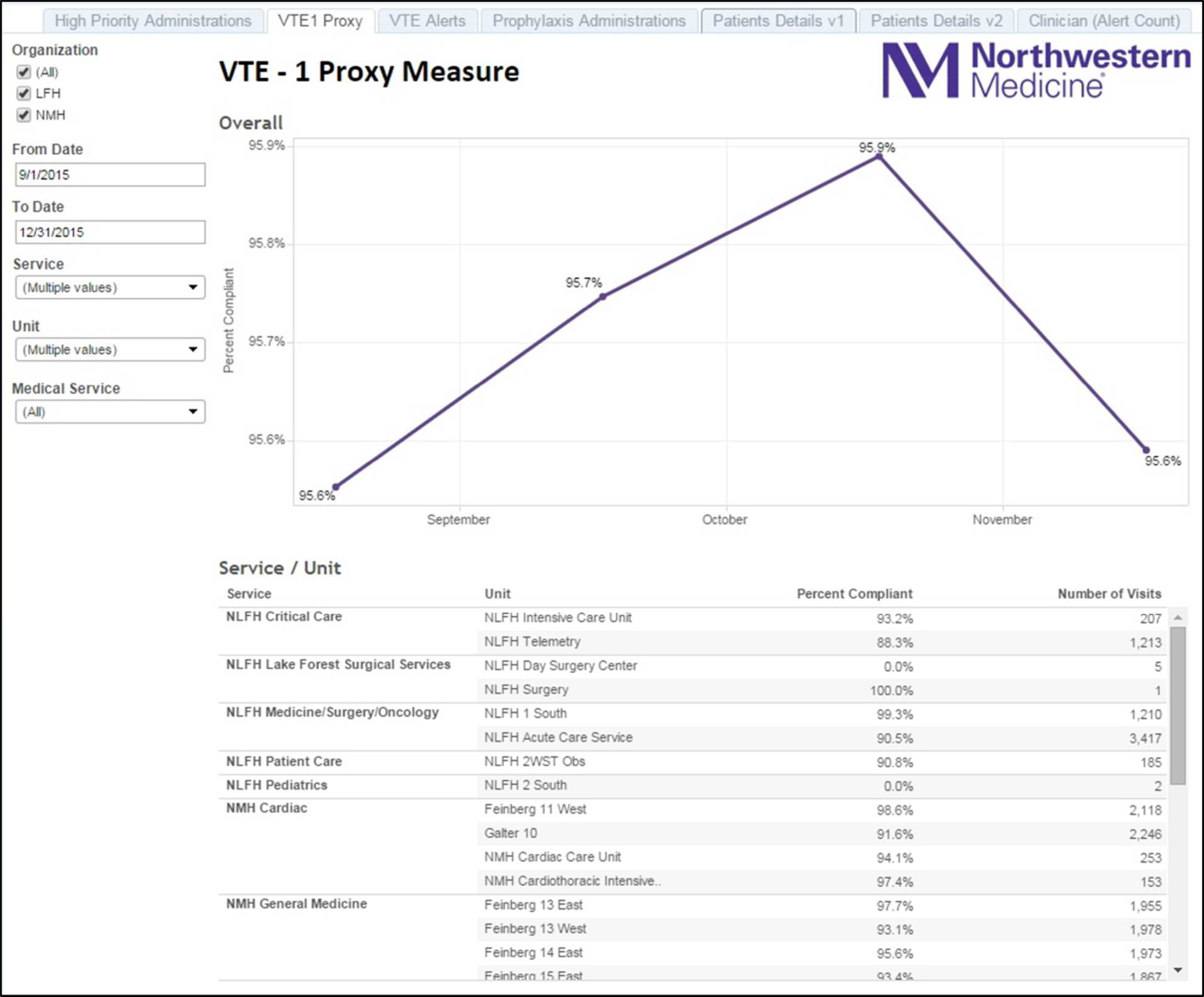

Mayo Clinic used CMS Core Measures in all 22 hospitals in the system from 2013 onward. The results are shown in Figure 1. Of note, VTE‐1 has improved from its project start values in the mid‐80% range to consistently above 95% for the last 6 quarters (most recently above 97%), VTE‐2 has averaged 97.3%, and most recently is at 100%, and VTE‐6 has declined from about 12% to 0% in the recent quarters.

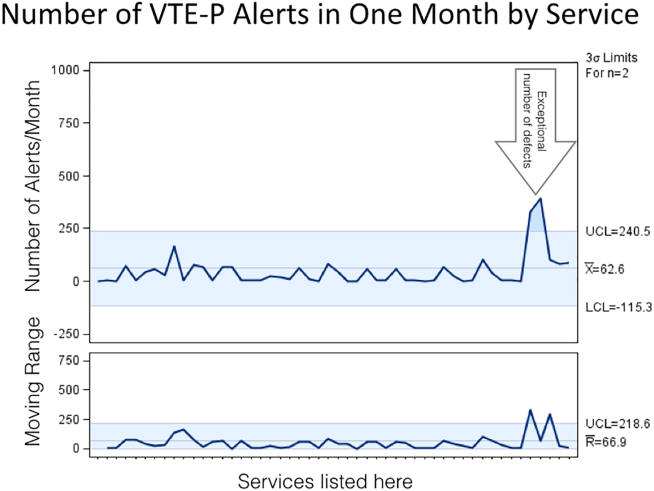

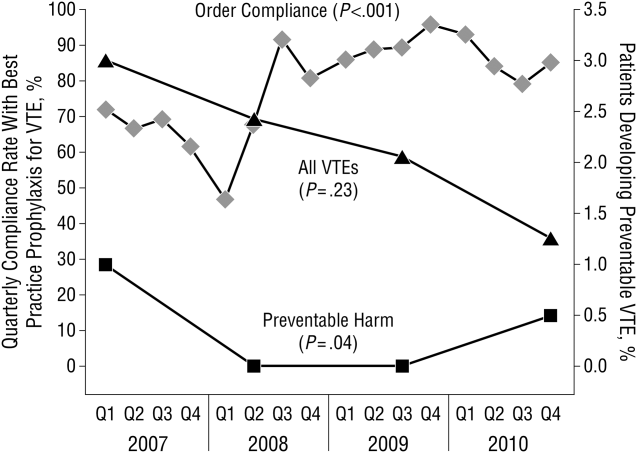

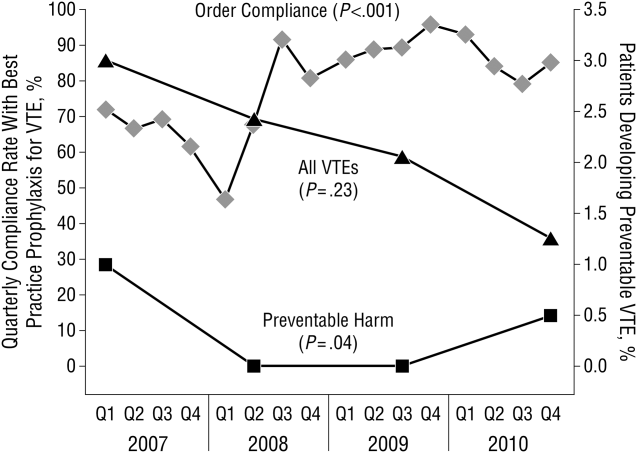

Figure 2 shows the number of VTE‐P alerts generated during 1 month by service in Mayo Clinic Rochester. We display these data as control charts so that practices on services with a statistically excessive number of alerts can be targeted for improvement. Similar data are available at all institutions.

Pediatric Patients

The PICU had an average of 101 admissions per month during study period (range, 72120) with a mean of 11 patients per day (range, 912 patients). Prior to the VTE‐P pilot, none had VTE risks documented. A total of 773 patients were screened for VTE in the intensive care unit during the study period, of which 194 were identified with 2 or greater VTE risk factors (25%). Sixty‐six of 194 patients (34%) had pharmacologic and/or mechanical prophylaxis (n = 83, 44%) selected for VTE‐P. No bleeding events were reported among these patients. During the discovery pilot, the VTE screening tool resulted in >92% compliance with risk documentation, >64% appropriate VTE‐P use, and 0 VTE events. The subsequently improved screening tool resulted in approximately 88% compliance over the subsequent 6 months of use, and in 9 months 2 VTE were diagnosed (both occurring in hospital units not using the screening tool).

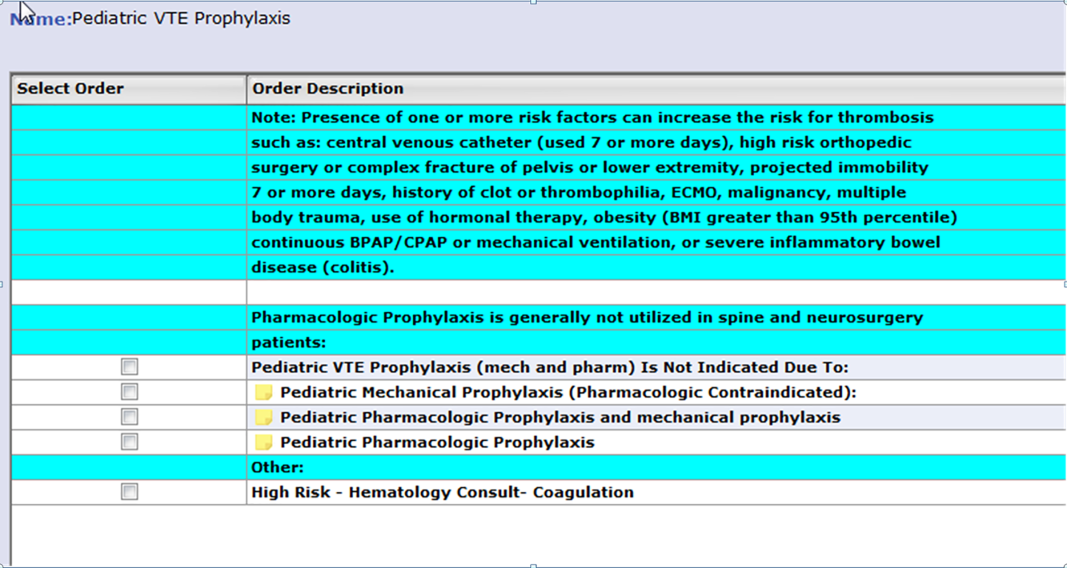

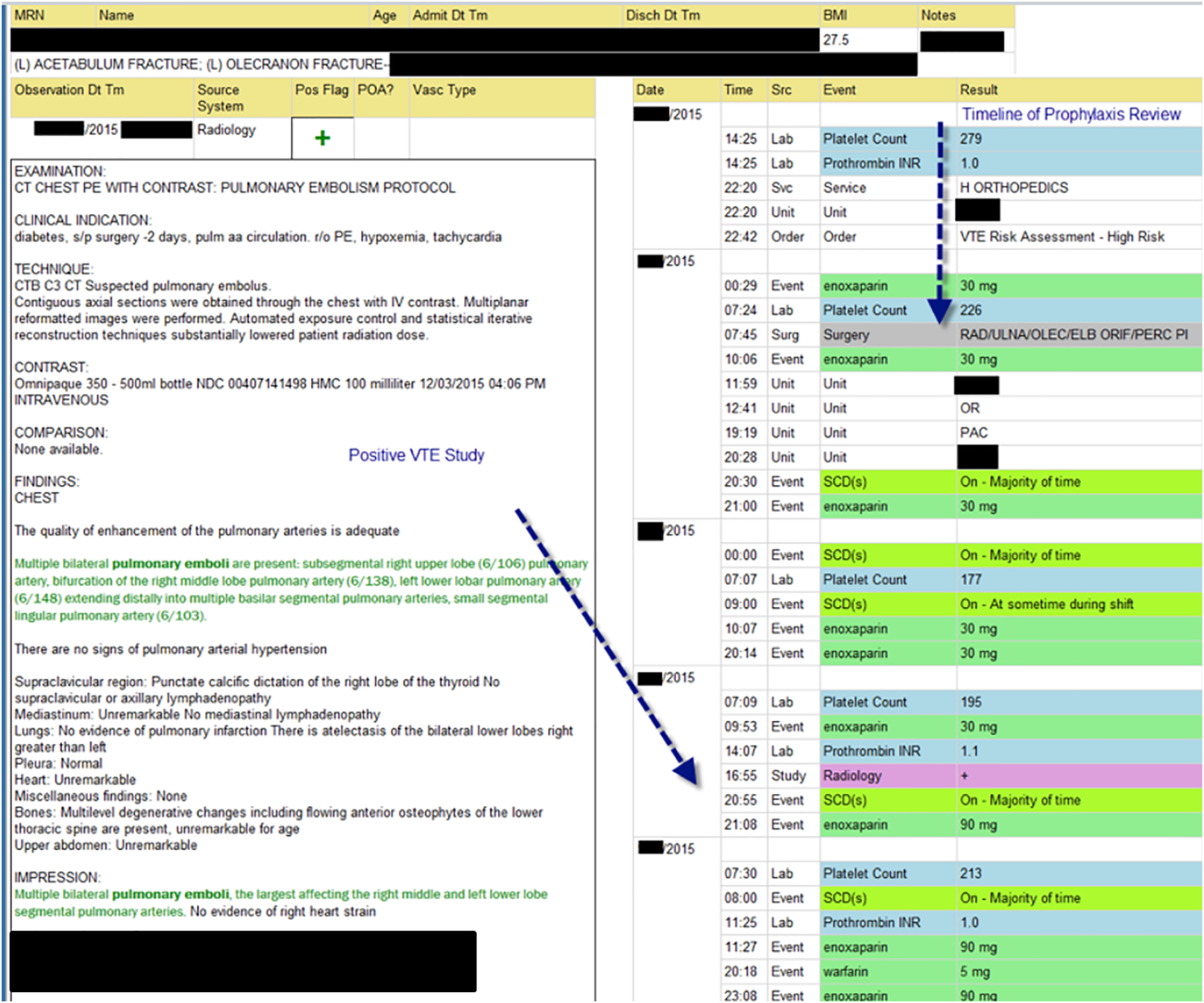

An electronic VTE‐P tollgate for pediatric patients went live on March 17, 2016 (Figure 3). We have also developed a CDS alert for pediatric patients not having an appropriate VTE‐P plan documented, and alert frequency reports will allow focused improvement efforts if needed.

DISCUSSION

Our VTE‐P system has resulted in significant reductions in preventable VTE. The key components of our system are: (1) Ensure that a VTE‐P is declared at admission by providing a mandatory VTE‐P tollgate that requires the provider to assess the risk for VTE and provide an appropriate order for VTE‐P. (2) Use clinical decision support to provide ongoing surveillance and alerting providers when there is a lapse in the VTE‐P plan. With these, we have driven CMS Core Measures VTE‐6 to 0 over 3 quarters.

Different VTE‐P strategies have been implemented among hospitalized medically ill patients. Despite the morbidity and mortality risks inherent to VTE, some studies have shown that more than half and nearly 79% of high‐risk hospitalized medical patients received no VTE prevention.[19] Among those who received prophylactic therapy, inadequate duration or type was prescribed in nearly 44%.[20] Electronic orders have resulted in improved prophylaxis in some literature reports.[21, 22] One study showed that a physician alert reduced VTE incidence from 4.13 to 2.23 events per 10,000 patients.[21] Our system, combining prompted electronic orders with clinical decision support for ongoing real‐time monitoring for VTE‐P plans appears to have been effective in producing reliable ordering of VTE‐P in both adults and children.

However, our system has limitations, some inherent in its design and others not addressed yet. Intrinsically, we depend upon clinicians to rightly gauge the patient risk for VTE‐P. Because a significant majority of our patients have at least moderate risk for VTE, the construction of the order sets tend to guide the clinician to select some form of prophylaxis. However, our system does not specifically provide guidance as to what VTE‐P to choose. If the clinician deems the patient at low risk, the CDS criteria will accept this judgment for up to 3 days without questioning the provider. Similarly, by national criteria, some patients at very high risk would ideally receive both mechanical and pharmacologic VTE‐P.[23] Our monitoring system does not distinguish between very high risk and moderately high risk when determining if a valid VTE‐P is in place. Audits of clinician decision making have shown that at present the appropriate decisions are being made 98% of the time, but this could change over time and with new guideline recommendations. Another challenge concerns the difference between ordering and delivering prophylaxis. When ordered, pharmacologic VTE‐P is reliably delivered. In contrast, providing ongoing delivery of ordered mechanical VTE‐P is more challenging. In addition, our current system does not extend to VTE‐P plans for discharge. Future clinical decision support might suggest which patients should receive combined prophylaxis while in the hospital or which home‐going prophylaxis plans should be considered.

We acknowledged the limitations of diffusing a VTE and bleeding risk‐assessment tool that has not been validated in our hospitalized pediatric population. Validation of pediatric VTE risk assessment tools have been recently developed but not widely validated in large prospective studies to be considered the standard of care.[6, 12] Based on our own institutional experience, the vast majority of VTE events occurred in pediatric patients with a central venous catheter (CVC) and other risk factors for thrombosis, and this category was arbitrarily chosen as one to consider pharmacologic prophylaxis if no bleeding risk factors and a central line to be in placed greater than 7 days duration. Although, pediatric evidence guidelines do not support the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in patients with CVC,[15] risk factors for thrombosis in children, although less frequent than adults, are still present, and VTE‐P should be assessed and individualized in each patient considered at risk for thrombosis. Other groups have attempted a similar approach as the one taken by our group, with variations in the criteria used for thromboprophylaxis in the pediatric population.[5, 14] Our data illustrate that not all pediatric patients require pharmacologic prophylaxis (34%), and VTE‐P should be individualized based on patient risk factors for thrombosis and bleeding risk.

A strength of our system is derived from the substantial clinician and expert input, the codification of consensus, and the hard wiring of that consensus into the electronic ordering, clinical decision rules, and reporting environment. As new advances to VTE‐P are developed, we will strive to codify those new processes into our workflow, building on our past success.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all of the members involved in the VTE prevention effort at Mayo Clinic including nurses, pharmacists, and information technology support staff.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178. Published 2008. Accessed May 23, 2016.

- , , , , . Deep‐vein thrombosis: a United States cost model for a preventable and costly adverse event. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:405–415.

- , , , . Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children's hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1001–1008.

- , , , , . Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in pediatric trauma. J Trauma. 2002;52:922–927.

- , , , , , . Incidence and risk factors for venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma. 2010;68:52–56.

- , , , , , . Risk factors for in‐hospital venous thromboembolism in children: a case‐control study employing diagnostic validation. Haematologica. 2012;97:509–515.

- . Prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(4):420–421.

- . Bridging the gap between evidence and practice in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: the quality improvement process. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1762–1770.

- , , , et al. Lessons from the Johns Hopkins Multi‐Disciplinary Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Prevention Collaborative. BMJ. 2012;344:e3935.

- , , , et al. Improved prophylaxis and decreased rates of preventable harm with the use of a mandatory computerized clinical decision support tool for prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in trauma. Arch Surg. 2012;14(10):901–907.

- , , , et al. Impact of a venous thromboembolism prophylaxis “smart order set”: improved compliance, fewer events. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:545–549.

- , , , et al. Risk‐prediction tool for identifying hospitalized children with a predisposition for development of venous thromboembolism: Peds‐Clot clinical Decision Rule. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1326–1334.

- , , , et al. Effectiveness of clinical guidelines for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1292–1297.

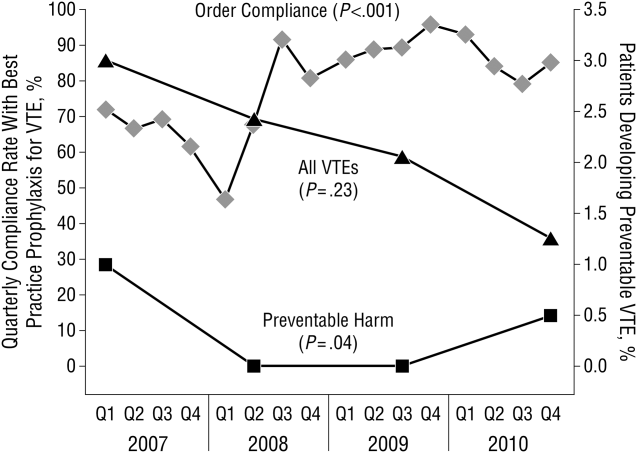

- , , , . Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric hospital: a patient‐safety and quality‐improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1326–e1332.

- , , , et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e737S–e801S.

- , , , et al. Safety and efficacy of low molecular weight heparins in children: a systematic review of the literature and meta‐analysis of single‐arm studies. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:814–825.

- , , , . Safety of prophylactic anticoagulation at a pediatric hospital. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35:e287–e291.

- , , , et al. Accelerating the use of best practices: the Mayo Clinic Model of Diffusion. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39:167–176.

- , , , , . Disease burden and unmet needs for prevention of venous thromboembolism in medically ill patients in Europe show underutilisation of preventive therapies. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:600–608.

- , , , . Pharmacological thromboembolic prophylaxis in a medical ward: room for improvement. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:788–791.

- , , , et al. Maintained effectiveness of an electronic alert system to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:699–704.

- , , , et al. Validation of a clinical guideline on prevention of venous thromboembolism in medical inpatients: a before‐and‐after study with systematic ultrasound examination. J Intern Med. 2004;256:338–348.

- , , , et al. Low‐molecular‐weight heparin and mortality in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:26: 2463–2472.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is a major cause of preventable hospital death and long‐term morbidity. VTE accounts for approximately 100,000 to 200,000 hospital deaths annually,[1] and preventable DVT costs an estimated $2.5 billion annually, with each case resulting in direct hospital costs of an estimated $25,977.[2] Although VTE is less common in children, its incidence is increasing in the medically ill hospitalized pediatric patient. The most recent analysis of a large national children's hospital database showed VTE rates increasing from 34 to 58 per 10,000 admissions from 2001 to 2007.[3] Rates in pediatric trauma patients are higher, at 60 to 100 per 10,000 admissions.[4, 5, 6]

The Joint Commission, the Surgeon General, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have supported initiatives to increase awareness and promote strategies designed to prevent hospital acquired VTE.[7, 8] There are several high‐quality, evidence‐based VTE prophylaxis (VTE‐P) guidelines for adult hospitalized populations.[9, 10, 11] Pediatric VTE‐P guidelines are not well established, but the literature regarding VTE risk stratification and prophylaxis guidelines for medically complex children is growing.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

A significant challenge has been developing systems that ensure that evidence and consensus‐based care recommendations are reliably implemented. This summary will describe the methods applied across an integrated health system that includes 22 acute care facilities and 1 pediatric hospital across 5 states that have resulted in a significant reduction in preventable VTE.

SETTING

Mayo Clinic is an integrated health system that owns 22 acute care facilities across 5 states, housing 3971 beds with approximately 122,000 admissions per year. Mayo Clinic Rochester, Arizona, and Florida are all tertiary academic medical centers with trauma and transplant programs. During this project, Arizona and Florida utilized a common build of the Cerner (Kansas City, MO) electronic health record (EHR). The other facilities, collectively referred to as the Mayo Clinic Health System (MCHS) hospitals, include 1 level II trauma center and 11 critical access hospitals and serve communities of varying sizes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. A different build of the Cerner EHR served the MCHS during this project.

Mayo Clinic Rochester is responsible for nearly 50% of all admissions and procedures. Mayo Eugenio Litta Children's Hospital, Rochester, Minnesota is a tertiary children's hospital facility housing 44 general pediatric beds, 26 neonatal intensive care unit beds, 24 intermediate nursery special care beds, and 16 pediatric intensive care unit beds. Mayo Clinic Rochester used the GE Centricity (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) EHR and custom‐designed computerized decision support.

METHODS

Mayo Clinic has developed a system to deliberately speed the diffusion of best practices across our system to drive reliable, evidence‐based care, reduce unwanted variation in processes and outcomes, and improve value.[18] The 3 main components of this system are (1) discovery: wherein we learn a practice that demonstrably solves the clinical problem well in at least 1 of our facilities, (2) assessment of readiness for diffusion, and (3) diffusion of the best practice across all of Mayo Clinic. The diffusion process is active and equipped with a project team and execution timeline. Both adult and pediatric projects began with discovery phases. The adult program has fully diffused; the pediatric program is diffusing at this writing.

ADULT ACUTE CARE PATIENTS

Discovery Through Pilot Projects

Beginning in 2006, 2 spontaneously convened interdisciplinary teams worked independently in selected medical and surgical practices in our Rochester hospital to improve VTE‐P. Each team's work resulted in the reduction of defect rates on pilot hospital services to <10%. Key findings were: (1) the vast majority of patients in the pilot had at least 1 risk factor for VTE and (2) when physicians explicitly determined a VTE‐P plan, they made the correct decision 98% of the time without any specific risk rule or point system.[18] Both teams found that efforts to ensure declaration of VTE‐P plans in the workflow of admission resulted in the most improvement in appropriate VTE‐P rates.

Creation of VTE‐Prevention Plans and the VTE Prophylaxis Tollgate

Based on lessons learned from the pilot projects, multidisciplinary improvement teams focused on adaptation of optimal VTE‐P plans for individual practices (eg, preferred VTE‐P for a neurosurgery patient is not the same as for a medical patient), and a VTE‐P tollgatea requirement for providers to complete a VTE‐P plan for each patientwas integrated into the clinical workflow of all order sets used for admissions, transfers, and for selected postoperative order sets. As we moved from the paper systems to computerized order entry, tollgates were subsequently converted to the GE Centricity electronic environment. To minimize burden on clinicians, designs were tested in a usability laboratory prior to operational deployment to ensure that they were as clear and easy as our software would allow.

Alerts

Based on initial reports and feedback, our clinical decision support (CDS) team designed alerts that notify the clinician when (1) any patient previously declared as at least moderate risk for VTE did not have a valid VTE‐P plan in place for any 24‐hour period, or (2) when any patient carried a low‐risk categorization for >3 days (because this should prompt reconsideration of risk status). Alerts were designed to be clear and to facilitate steps to correct the situation.

VTE‐P alerts would present to any member of the patient's provider team who accessed the patient's EHR, and would continue to alert with each access until conditions were rendered to satisfy the requirements of the alert. Each alert provided easy access to an abbreviated VTE‐P tollgate order that would allow the provider to select a clinically appropriate response: either restate the low‐risk status, change the low‐risk status and add an active VTE‐P order, specify why neither mechanical nor pharmacologic VTE‐P may be given, or restart a VTE‐P order.

Monitoring

Both process and outcome measures were used to monitor the effectiveness of VTE‐P activities. During initial roll‐out, the teams measured and reported the proportion of patients where either (1) VTE risk factors were present (patient is determined to be at least at moderate risk for VTE) and either pharmacologic or mechanical VTE‐P was ordered within 24 hours of admission, or (2) VTE risk factors were not present, and VTE‐P not indicated was documented within 24 hours of admission. The CDS system also provided ongoing monitoring of CDS‐alert firing frequency, which closely correlated with the prevalence of patients without a valid VTE‐P plan.

Diffusion Across All Units of Mayo Rochester

Diffusion teams included physician champions, project managers, a pharmacist, and a nurse. To emphasize the engagement of institutional leadership, the project was commissioned by the institution's Clinical Practice Quality Oversight Committee and co‐chaired by the Department of Medicine Associate Chair for Quality and the Chair of the Surgical Quality and Safety Subcommittee.

Implementation of this integrated system resulted in substantial improvement to 97% hospital‐wide VTE‐P rates that were sustained over 3 quarters. At that time, a decision was made to diffuse this new best practice across all Mayo Clinic acute care facilities.

Diffusion to All 22 Mayo Clinic Acute Care Facilities

After readiness for diffusion assessment,[18] an enterprise diffusion team, this time led by the Mayo Clinic Patient Safety Officer (an MD), 3 other physician champions (1 from each region of the Mayo Clinic), a project manager, a pharmacist, a computerized physician order entry system content specialist, and the institutional quality office personnel who assisted with the measurement, analysis, and display of data at the work sites. The best practices diffused were: (1) All admission or transfer order sets will have a VTE‐P tollgate. (2) All VTE‐P tollgates will be a force function (ie, they cannot be bypassed). (3) Over 95% of all eligible patients in the facility at any given moment will have a valid VTE‐P plan in place. (4) Ongoing compliance monitoring must be available as an automatic feed, not by chart review. The end goal of our diffusion process was to ensure that all best practices were ensured at all of our facilities.

Key issues in the diffusion process included implementation of the VTE‐P tollgates into all admission or transfer order sets and the computer decision support logic that had been developed in the GE Centricity system into the Cerner EHR. Each system had slightly different constraints to 4 best practices to be diffused. We had difficulty designing the GE Centricity order sets or flags in such a way that absolutely forced an action (best practice items 1 and 2). Instead, our design had to alert the ordering provider until the appropriate conditions were met. This is suboptimal in that it creates the potential for alarm fatigue and subsequent error. It is for that reason that a tight monitoring system was necessary to provide feedback on a per‐provider level if the alerts were too numerous (suggesting that alarm fatigue or misunderstanding might be leading to failure to correct the unsafe situation producing the alarm).

In contrast, the Cerner system did not have as much capability for our IT support to provide as much customization of decision support but was fully capable of forcing functions. Therefore, we needed to provide a more rigid logic into the order sets. This led to a less than optimal user interface each time a patient was admitted or transferred, but fulfilled mission goals.

Pediatric Patients

Pediatric Discovery Project

Development of Pediatric VTE Risk‐Assessment Tool

To develop a VTE‐P system for our pediatric hospital, our first task was to design a VTE risk‐stratification tool. The improvement team included a physician, pharmacist, and clinical nurse specialists from pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), cardiac intensive care units, and general pediatric services. A literature review identified the most common published risk factors for VTE in children. We next performed a retrospective review of pediatric hospital‐acquired VTE in 2011 to 2012. Eight VTEs were identified (infants to age 18 years). All were related to central venous catheters, sepsis, congenital heart disease, leukemia, myocarditis, and extreme prematurity (Table 1). In contrast to other series, our patients were younger (80% less than 14 years of age). Based on these reviews and iterative consensus with our pediatric staff, an initial pediatric VTE risk‐screening tool was designed and piloted first in the PICU for usability and to assess face validity.

| Age/Gender | Main Diagnosis | Comorbidities | Central Lines Prior to VTE Event | VTE Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| 18 y/M | Congenital heart disease | Heart transplant | Right and left IJV, right arterial, left femoral vein and artery | DVT left IJV, innominate, subclavian, axillary veins |

| 3 y/M | Idiopathic myocarditis | ECMO | Left radial arterial, right brachial PICC, RIJ venous, left arterial femoral, right venous femoral, | Cerebral embolism with multiple infarcts |

| 0.2 y/F | Premature | NEC | Right IJ PICC | Right axillary, subclavian DVT, left greater saphenous vein |

| 0.5 y/M | Premature | Hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy | Umbilical artery and vein catheters, right IJ PICC, right femoral venous | IVC thrombosis and bilateral renal veins |

| 0.1 y/F | Sepsis | RSV pneumonia | Right femoral venous | Right common femoral and right external iliac DVT |

| 12 y/M | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Renal dysfunction | Left femoral arterial, right femoral venous | Right common femoral DVT |

| 0.1 y/M | Congenital heart disease | Umbilical artery and vein catheters, left femoral artery, right IJV | Left femoral artery thrombosis | |

| 1 y/M | Seizures | Partially treated meningitis/hyponatremia | Left femoral vein | Left common femoral and external iliac DVT |

Developing Consensus About Appropriate VTE‐P

The risk of even low‐dose anticoagulation may be higher in children than in adults. Therefore, in addition to first estimating the risk for VTE, we also incorporated into the risk‐assessment tool an estimate of risk for bleeding (Table 2). Physicians were responsible for using the VTE‐P screening. Bleeding risk‐assessment categories included: intracranial bleed, premature infant, internal injury (eg, organ injury, splenic laceration), planned surgery within 24 hours, renal failure, liver dysfunction, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia (eg, platelets <50,000), disseminated intravascular coagulation, congenital bleeding disorder, and neurosurgical and spine fusion patients. If any of these were present, pharmacologic prophylaxis was contraindicated. If a patient was considered at risk for VTE, a pediatric hematology consult was recommended or advised. If there was no increased bleeding risk and the child had 2 or more risk factors or a central venous catheter with additional thrombosis risk factors, the consensus was to use appropriately dosed low‐molecular‐weight heparin or unfractionated heparin in addition to mechanical prophylaxis. A patient considered at increased risk for bleeding but with risk factors for thrombosis would receive early ambulation and/or mechanical prophylaxis. In all cases, removal of central catheters was recommended within 72 hours if possible.

|

| Risk factors |

| Central venous catheter 7 days |

| High‐risk orthopedic surgery |

| Complex fracture of pelvis or lower extremity |

| Projected immobility for 7 days |

| History of prior VTE |

| History of prior thrombophilia |

| ECMO |

| Malignancy |

| Multiple body trauma |

| Use of hormonal therapy |

| BMI > 95th percentile |

| Continuous BPAP/CPAP or mechanical ventilation |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Guidance if no increased bleeding risk |

| 2 risk factorsmechanical combined with pharmacologic prophylaxis |

| Central venous catheter 7 days and additional thrombosis risk factorsmechanical combined with pharmacologic prophylaxis |

| Pharmacologic prophylaxis generally not utilized in spine or neurosurgery patients |

| Guidance if increased bleeding risk |

| 2 risk factors or central venous catheter and additional thrombosis risk factors 7 days hematology consult |

| 2 risk factors or central venous catheter 7 days and additional thrombosis risk factorsearly ambulation + mechanical VTE‐P |

Pilot Implementation

We initiated use of the risk‐assessment tool and VTE‐P algorithm in the PICU using a paper system at first, and measured via chart review (1) the proportion of patients for whom a VTE‐P risk assessment was completed according to the recommended plan and (2) the proportion with the appropriate VTE‐P plan selected based upon risk factors present. The risk‐assessment tool was iteratively improved and built into the electronic order system (Table 2). This would ensure diffusion across the children's hospital, and would be subsequently diffused across the rest of Mayo Clinic.

Metrics

During the system diffusion for the adult system, we relied on 2 metrics to measure improvement: the CDS alert frequency and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) VTE Core Measures. The CDS alert frequency is cross‐sectional and can be used to estimate what percentage of patients at any given moment in time in our hospital have a valid VTE‐P. From chart audits, we anticipate that at target, approximately 4% of patients would generate CDS alerts because needs and plans change in the dynamic care environment. For example, VTE‐P may be held for a procedure, or during transition from 1 to another unit. Or, observation patients may have been classified as low risk, but when converted to admission status there may be a lag while the VTE risk status is changed. These data can be provided by service and provider, and are reported back to the providers to help reduce practice variation.

In addition, the CMS Core Measures provided a manual chart review metric to supplement the automated data. VTE‐1 and VTE‐2 measures the proportion of sampled charts demonstrating either delivery of VTE‐P or declaration of low risk in non‐ICU and ICU patients, respectively. VTE‐6, the proportion of patients acquiring a VTE who did not receive prophylaxis, served as our outcome measure. For the pediatric efforts, manual chart review served during the improvement pilots, but will be supplanted by a similar automated system.

RESULTS

Adult Acute Care Patients

Mayo Clinic used CMS Core Measures in all 22 hospitals in the system from 2013 onward. The results are shown in Figure 1. Of note, VTE‐1 has improved from its project start values in the mid‐80% range to consistently above 95% for the last 6 quarters (most recently above 97%), VTE‐2 has averaged 97.3%, and most recently is at 100%, and VTE‐6 has declined from about 12% to 0% in the recent quarters.

Figure 2 shows the number of VTE‐P alerts generated during 1 month by service in Mayo Clinic Rochester. We display these data as control charts so that practices on services with a statistically excessive number of alerts can be targeted for improvement. Similar data are available at all institutions.

Pediatric Patients

The PICU had an average of 101 admissions per month during study period (range, 72120) with a mean of 11 patients per day (range, 912 patients). Prior to the VTE‐P pilot, none had VTE risks documented. A total of 773 patients were screened for VTE in the intensive care unit during the study period, of which 194 were identified with 2 or greater VTE risk factors (25%). Sixty‐six of 194 patients (34%) had pharmacologic and/or mechanical prophylaxis (n = 83, 44%) selected for VTE‐P. No bleeding events were reported among these patients. During the discovery pilot, the VTE screening tool resulted in >92% compliance with risk documentation, >64% appropriate VTE‐P use, and 0 VTE events. The subsequently improved screening tool resulted in approximately 88% compliance over the subsequent 6 months of use, and in 9 months 2 VTE were diagnosed (both occurring in hospital units not using the screening tool).

An electronic VTE‐P tollgate for pediatric patients went live on March 17, 2016 (Figure 3). We have also developed a CDS alert for pediatric patients not having an appropriate VTE‐P plan documented, and alert frequency reports will allow focused improvement efforts if needed.

DISCUSSION

Our VTE‐P system has resulted in significant reductions in preventable VTE. The key components of our system are: (1) Ensure that a VTE‐P is declared at admission by providing a mandatory VTE‐P tollgate that requires the provider to assess the risk for VTE and provide an appropriate order for VTE‐P. (2) Use clinical decision support to provide ongoing surveillance and alerting providers when there is a lapse in the VTE‐P plan. With these, we have driven CMS Core Measures VTE‐6 to 0 over 3 quarters.

Different VTE‐P strategies have been implemented among hospitalized medically ill patients. Despite the morbidity and mortality risks inherent to VTE, some studies have shown that more than half and nearly 79% of high‐risk hospitalized medical patients received no VTE prevention.[19] Among those who received prophylactic therapy, inadequate duration or type was prescribed in nearly 44%.[20] Electronic orders have resulted in improved prophylaxis in some literature reports.[21, 22] One study showed that a physician alert reduced VTE incidence from 4.13 to 2.23 events per 10,000 patients.[21] Our system, combining prompted electronic orders with clinical decision support for ongoing real‐time monitoring for VTE‐P plans appears to have been effective in producing reliable ordering of VTE‐P in both adults and children.

However, our system has limitations, some inherent in its design and others not addressed yet. Intrinsically, we depend upon clinicians to rightly gauge the patient risk for VTE‐P. Because a significant majority of our patients have at least moderate risk for VTE, the construction of the order sets tend to guide the clinician to select some form of prophylaxis. However, our system does not specifically provide guidance as to what VTE‐P to choose. If the clinician deems the patient at low risk, the CDS criteria will accept this judgment for up to 3 days without questioning the provider. Similarly, by national criteria, some patients at very high risk would ideally receive both mechanical and pharmacologic VTE‐P.[23] Our monitoring system does not distinguish between very high risk and moderately high risk when determining if a valid VTE‐P is in place. Audits of clinician decision making have shown that at present the appropriate decisions are being made 98% of the time, but this could change over time and with new guideline recommendations. Another challenge concerns the difference between ordering and delivering prophylaxis. When ordered, pharmacologic VTE‐P is reliably delivered. In contrast, providing ongoing delivery of ordered mechanical VTE‐P is more challenging. In addition, our current system does not extend to VTE‐P plans for discharge. Future clinical decision support might suggest which patients should receive combined prophylaxis while in the hospital or which home‐going prophylaxis plans should be considered.

We acknowledged the limitations of diffusing a VTE and bleeding risk‐assessment tool that has not been validated in our hospitalized pediatric population. Validation of pediatric VTE risk assessment tools have been recently developed but not widely validated in large prospective studies to be considered the standard of care.[6, 12] Based on our own institutional experience, the vast majority of VTE events occurred in pediatric patients with a central venous catheter (CVC) and other risk factors for thrombosis, and this category was arbitrarily chosen as one to consider pharmacologic prophylaxis if no bleeding risk factors and a central line to be in placed greater than 7 days duration. Although, pediatric evidence guidelines do not support the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in patients with CVC,[15] risk factors for thrombosis in children, although less frequent than adults, are still present, and VTE‐P should be assessed and individualized in each patient considered at risk for thrombosis. Other groups have attempted a similar approach as the one taken by our group, with variations in the criteria used for thromboprophylaxis in the pediatric population.[5, 14] Our data illustrate that not all pediatric patients require pharmacologic prophylaxis (34%), and VTE‐P should be individualized based on patient risk factors for thrombosis and bleeding risk.

A strength of our system is derived from the substantial clinician and expert input, the codification of consensus, and the hard wiring of that consensus into the electronic ordering, clinical decision rules, and reporting environment. As new advances to VTE‐P are developed, we will strive to codify those new processes into our workflow, building on our past success.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all of the members involved in the VTE prevention effort at Mayo Clinic including nurses, pharmacists, and information technology support staff.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is a major cause of preventable hospital death and long‐term morbidity. VTE accounts for approximately 100,000 to 200,000 hospital deaths annually,[1] and preventable DVT costs an estimated $2.5 billion annually, with each case resulting in direct hospital costs of an estimated $25,977.[2] Although VTE is less common in children, its incidence is increasing in the medically ill hospitalized pediatric patient. The most recent analysis of a large national children's hospital database showed VTE rates increasing from 34 to 58 per 10,000 admissions from 2001 to 2007.[3] Rates in pediatric trauma patients are higher, at 60 to 100 per 10,000 admissions.[4, 5, 6]

The Joint Commission, the Surgeon General, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have supported initiatives to increase awareness and promote strategies designed to prevent hospital acquired VTE.[7, 8] There are several high‐quality, evidence‐based VTE prophylaxis (VTE‐P) guidelines for adult hospitalized populations.[9, 10, 11] Pediatric VTE‐P guidelines are not well established, but the literature regarding VTE risk stratification and prophylaxis guidelines for medically complex children is growing.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

A significant challenge has been developing systems that ensure that evidence and consensus‐based care recommendations are reliably implemented. This summary will describe the methods applied across an integrated health system that includes 22 acute care facilities and 1 pediatric hospital across 5 states that have resulted in a significant reduction in preventable VTE.

SETTING

Mayo Clinic is an integrated health system that owns 22 acute care facilities across 5 states, housing 3971 beds with approximately 122,000 admissions per year. Mayo Clinic Rochester, Arizona, and Florida are all tertiary academic medical centers with trauma and transplant programs. During this project, Arizona and Florida utilized a common build of the Cerner (Kansas City, MO) electronic health record (EHR). The other facilities, collectively referred to as the Mayo Clinic Health System (MCHS) hospitals, include 1 level II trauma center and 11 critical access hospitals and serve communities of varying sizes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. A different build of the Cerner EHR served the MCHS during this project.

Mayo Clinic Rochester is responsible for nearly 50% of all admissions and procedures. Mayo Eugenio Litta Children's Hospital, Rochester, Minnesota is a tertiary children's hospital facility housing 44 general pediatric beds, 26 neonatal intensive care unit beds, 24 intermediate nursery special care beds, and 16 pediatric intensive care unit beds. Mayo Clinic Rochester used the GE Centricity (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) EHR and custom‐designed computerized decision support.

METHODS

Mayo Clinic has developed a system to deliberately speed the diffusion of best practices across our system to drive reliable, evidence‐based care, reduce unwanted variation in processes and outcomes, and improve value.[18] The 3 main components of this system are (1) discovery: wherein we learn a practice that demonstrably solves the clinical problem well in at least 1 of our facilities, (2) assessment of readiness for diffusion, and (3) diffusion of the best practice across all of Mayo Clinic. The diffusion process is active and equipped with a project team and execution timeline. Both adult and pediatric projects began with discovery phases. The adult program has fully diffused; the pediatric program is diffusing at this writing.

ADULT ACUTE CARE PATIENTS

Discovery Through Pilot Projects

Beginning in 2006, 2 spontaneously convened interdisciplinary teams worked independently in selected medical and surgical practices in our Rochester hospital to improve VTE‐P. Each team's work resulted in the reduction of defect rates on pilot hospital services to <10%. Key findings were: (1) the vast majority of patients in the pilot had at least 1 risk factor for VTE and (2) when physicians explicitly determined a VTE‐P plan, they made the correct decision 98% of the time without any specific risk rule or point system.[18] Both teams found that efforts to ensure declaration of VTE‐P plans in the workflow of admission resulted in the most improvement in appropriate VTE‐P rates.

Creation of VTE‐Prevention Plans and the VTE Prophylaxis Tollgate

Based on lessons learned from the pilot projects, multidisciplinary improvement teams focused on adaptation of optimal VTE‐P plans for individual practices (eg, preferred VTE‐P for a neurosurgery patient is not the same as for a medical patient), and a VTE‐P tollgatea requirement for providers to complete a VTE‐P plan for each patientwas integrated into the clinical workflow of all order sets used for admissions, transfers, and for selected postoperative order sets. As we moved from the paper systems to computerized order entry, tollgates were subsequently converted to the GE Centricity electronic environment. To minimize burden on clinicians, designs were tested in a usability laboratory prior to operational deployment to ensure that they were as clear and easy as our software would allow.

Alerts

Based on initial reports and feedback, our clinical decision support (CDS) team designed alerts that notify the clinician when (1) any patient previously declared as at least moderate risk for VTE did not have a valid VTE‐P plan in place for any 24‐hour period, or (2) when any patient carried a low‐risk categorization for >3 days (because this should prompt reconsideration of risk status). Alerts were designed to be clear and to facilitate steps to correct the situation.

VTE‐P alerts would present to any member of the patient's provider team who accessed the patient's EHR, and would continue to alert with each access until conditions were rendered to satisfy the requirements of the alert. Each alert provided easy access to an abbreviated VTE‐P tollgate order that would allow the provider to select a clinically appropriate response: either restate the low‐risk status, change the low‐risk status and add an active VTE‐P order, specify why neither mechanical nor pharmacologic VTE‐P may be given, or restart a VTE‐P order.

Monitoring

Both process and outcome measures were used to monitor the effectiveness of VTE‐P activities. During initial roll‐out, the teams measured and reported the proportion of patients where either (1) VTE risk factors were present (patient is determined to be at least at moderate risk for VTE) and either pharmacologic or mechanical VTE‐P was ordered within 24 hours of admission, or (2) VTE risk factors were not present, and VTE‐P not indicated was documented within 24 hours of admission. The CDS system also provided ongoing monitoring of CDS‐alert firing frequency, which closely correlated with the prevalence of patients without a valid VTE‐P plan.

Diffusion Across All Units of Mayo Rochester

Diffusion teams included physician champions, project managers, a pharmacist, and a nurse. To emphasize the engagement of institutional leadership, the project was commissioned by the institution's Clinical Practice Quality Oversight Committee and co‐chaired by the Department of Medicine Associate Chair for Quality and the Chair of the Surgical Quality and Safety Subcommittee.

Implementation of this integrated system resulted in substantial improvement to 97% hospital‐wide VTE‐P rates that were sustained over 3 quarters. At that time, a decision was made to diffuse this new best practice across all Mayo Clinic acute care facilities.

Diffusion to All 22 Mayo Clinic Acute Care Facilities

After readiness for diffusion assessment,[18] an enterprise diffusion team, this time led by the Mayo Clinic Patient Safety Officer (an MD), 3 other physician champions (1 from each region of the Mayo Clinic), a project manager, a pharmacist, a computerized physician order entry system content specialist, and the institutional quality office personnel who assisted with the measurement, analysis, and display of data at the work sites. The best practices diffused were: (1) All admission or transfer order sets will have a VTE‐P tollgate. (2) All VTE‐P tollgates will be a force function (ie, they cannot be bypassed). (3) Over 95% of all eligible patients in the facility at any given moment will have a valid VTE‐P plan in place. (4) Ongoing compliance monitoring must be available as an automatic feed, not by chart review. The end goal of our diffusion process was to ensure that all best practices were ensured at all of our facilities.

Key issues in the diffusion process included implementation of the VTE‐P tollgates into all admission or transfer order sets and the computer decision support logic that had been developed in the GE Centricity system into the Cerner EHR. Each system had slightly different constraints to 4 best practices to be diffused. We had difficulty designing the GE Centricity order sets or flags in such a way that absolutely forced an action (best practice items 1 and 2). Instead, our design had to alert the ordering provider until the appropriate conditions were met. This is suboptimal in that it creates the potential for alarm fatigue and subsequent error. It is for that reason that a tight monitoring system was necessary to provide feedback on a per‐provider level if the alerts were too numerous (suggesting that alarm fatigue or misunderstanding might be leading to failure to correct the unsafe situation producing the alarm).

In contrast, the Cerner system did not have as much capability for our IT support to provide as much customization of decision support but was fully capable of forcing functions. Therefore, we needed to provide a more rigid logic into the order sets. This led to a less than optimal user interface each time a patient was admitted or transferred, but fulfilled mission goals.

Pediatric Patients

Pediatric Discovery Project

Development of Pediatric VTE Risk‐Assessment Tool

To develop a VTE‐P system for our pediatric hospital, our first task was to design a VTE risk‐stratification tool. The improvement team included a physician, pharmacist, and clinical nurse specialists from pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), cardiac intensive care units, and general pediatric services. A literature review identified the most common published risk factors for VTE in children. We next performed a retrospective review of pediatric hospital‐acquired VTE in 2011 to 2012. Eight VTEs were identified (infants to age 18 years). All were related to central venous catheters, sepsis, congenital heart disease, leukemia, myocarditis, and extreme prematurity (Table 1). In contrast to other series, our patients were younger (80% less than 14 years of age). Based on these reviews and iterative consensus with our pediatric staff, an initial pediatric VTE risk‐screening tool was designed and piloted first in the PICU for usability and to assess face validity.

| Age/Gender | Main Diagnosis | Comorbidities | Central Lines Prior to VTE Event | VTE Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| 18 y/M | Congenital heart disease | Heart transplant | Right and left IJV, right arterial, left femoral vein and artery | DVT left IJV, innominate, subclavian, axillary veins |

| 3 y/M | Idiopathic myocarditis | ECMO | Left radial arterial, right brachial PICC, RIJ venous, left arterial femoral, right venous femoral, | Cerebral embolism with multiple infarcts |

| 0.2 y/F | Premature | NEC | Right IJ PICC | Right axillary, subclavian DVT, left greater saphenous vein |

| 0.5 y/M | Premature | Hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy | Umbilical artery and vein catheters, right IJ PICC, right femoral venous | IVC thrombosis and bilateral renal veins |

| 0.1 y/F | Sepsis | RSV pneumonia | Right femoral venous | Right common femoral and right external iliac DVT |

| 12 y/M | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Renal dysfunction | Left femoral arterial, right femoral venous | Right common femoral DVT |

| 0.1 y/M | Congenital heart disease | Umbilical artery and vein catheters, left femoral artery, right IJV | Left femoral artery thrombosis | |

| 1 y/M | Seizures | Partially treated meningitis/hyponatremia | Left femoral vein | Left common femoral and external iliac DVT |

Developing Consensus About Appropriate VTE‐P

The risk of even low‐dose anticoagulation may be higher in children than in adults. Therefore, in addition to first estimating the risk for VTE, we also incorporated into the risk‐assessment tool an estimate of risk for bleeding (Table 2). Physicians were responsible for using the VTE‐P screening. Bleeding risk‐assessment categories included: intracranial bleed, premature infant, internal injury (eg, organ injury, splenic laceration), planned surgery within 24 hours, renal failure, liver dysfunction, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia (eg, platelets <50,000), disseminated intravascular coagulation, congenital bleeding disorder, and neurosurgical and spine fusion patients. If any of these were present, pharmacologic prophylaxis was contraindicated. If a patient was considered at risk for VTE, a pediatric hematology consult was recommended or advised. If there was no increased bleeding risk and the child had 2 or more risk factors or a central venous catheter with additional thrombosis risk factors, the consensus was to use appropriately dosed low‐molecular‐weight heparin or unfractionated heparin in addition to mechanical prophylaxis. A patient considered at increased risk for bleeding but with risk factors for thrombosis would receive early ambulation and/or mechanical prophylaxis. In all cases, removal of central catheters was recommended within 72 hours if possible.

|

| Risk factors |

| Central venous catheter 7 days |

| High‐risk orthopedic surgery |

| Complex fracture of pelvis or lower extremity |

| Projected immobility for 7 days |

| History of prior VTE |

| History of prior thrombophilia |

| ECMO |

| Malignancy |

| Multiple body trauma |

| Use of hormonal therapy |

| BMI > 95th percentile |

| Continuous BPAP/CPAP or mechanical ventilation |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Guidance if no increased bleeding risk |

| 2 risk factorsmechanical combined with pharmacologic prophylaxis |

| Central venous catheter 7 days and additional thrombosis risk factorsmechanical combined with pharmacologic prophylaxis |

| Pharmacologic prophylaxis generally not utilized in spine or neurosurgery patients |

| Guidance if increased bleeding risk |

| 2 risk factors or central venous catheter and additional thrombosis risk factors 7 days hematology consult |

| 2 risk factors or central venous catheter 7 days and additional thrombosis risk factorsearly ambulation + mechanical VTE‐P |

Pilot Implementation

We initiated use of the risk‐assessment tool and VTE‐P algorithm in the PICU using a paper system at first, and measured via chart review (1) the proportion of patients for whom a VTE‐P risk assessment was completed according to the recommended plan and (2) the proportion with the appropriate VTE‐P plan selected based upon risk factors present. The risk‐assessment tool was iteratively improved and built into the electronic order system (Table 2). This would ensure diffusion across the children's hospital, and would be subsequently diffused across the rest of Mayo Clinic.

Metrics

During the system diffusion for the adult system, we relied on 2 metrics to measure improvement: the CDS alert frequency and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) VTE Core Measures. The CDS alert frequency is cross‐sectional and can be used to estimate what percentage of patients at any given moment in time in our hospital have a valid VTE‐P. From chart audits, we anticipate that at target, approximately 4% of patients would generate CDS alerts because needs and plans change in the dynamic care environment. For example, VTE‐P may be held for a procedure, or during transition from 1 to another unit. Or, observation patients may have been classified as low risk, but when converted to admission status there may be a lag while the VTE risk status is changed. These data can be provided by service and provider, and are reported back to the providers to help reduce practice variation.

In addition, the CMS Core Measures provided a manual chart review metric to supplement the automated data. VTE‐1 and VTE‐2 measures the proportion of sampled charts demonstrating either delivery of VTE‐P or declaration of low risk in non‐ICU and ICU patients, respectively. VTE‐6, the proportion of patients acquiring a VTE who did not receive prophylaxis, served as our outcome measure. For the pediatric efforts, manual chart review served during the improvement pilots, but will be supplanted by a similar automated system.

RESULTS

Adult Acute Care Patients

Mayo Clinic used CMS Core Measures in all 22 hospitals in the system from 2013 onward. The results are shown in Figure 1. Of note, VTE‐1 has improved from its project start values in the mid‐80% range to consistently above 95% for the last 6 quarters (most recently above 97%), VTE‐2 has averaged 97.3%, and most recently is at 100%, and VTE‐6 has declined from about 12% to 0% in the recent quarters.

Figure 2 shows the number of VTE‐P alerts generated during 1 month by service in Mayo Clinic Rochester. We display these data as control charts so that practices on services with a statistically excessive number of alerts can be targeted for improvement. Similar data are available at all institutions.

Pediatric Patients

The PICU had an average of 101 admissions per month during study period (range, 72120) with a mean of 11 patients per day (range, 912 patients). Prior to the VTE‐P pilot, none had VTE risks documented. A total of 773 patients were screened for VTE in the intensive care unit during the study period, of which 194 were identified with 2 or greater VTE risk factors (25%). Sixty‐six of 194 patients (34%) had pharmacologic and/or mechanical prophylaxis (n = 83, 44%) selected for VTE‐P. No bleeding events were reported among these patients. During the discovery pilot, the VTE screening tool resulted in >92% compliance with risk documentation, >64% appropriate VTE‐P use, and 0 VTE events. The subsequently improved screening tool resulted in approximately 88% compliance over the subsequent 6 months of use, and in 9 months 2 VTE were diagnosed (both occurring in hospital units not using the screening tool).

An electronic VTE‐P tollgate for pediatric patients went live on March 17, 2016 (Figure 3). We have also developed a CDS alert for pediatric patients not having an appropriate VTE‐P plan documented, and alert frequency reports will allow focused improvement efforts if needed.

DISCUSSION

Our VTE‐P system has resulted in significant reductions in preventable VTE. The key components of our system are: (1) Ensure that a VTE‐P is declared at admission by providing a mandatory VTE‐P tollgate that requires the provider to assess the risk for VTE and provide an appropriate order for VTE‐P. (2) Use clinical decision support to provide ongoing surveillance and alerting providers when there is a lapse in the VTE‐P plan. With these, we have driven CMS Core Measures VTE‐6 to 0 over 3 quarters.

Different VTE‐P strategies have been implemented among hospitalized medically ill patients. Despite the morbidity and mortality risks inherent to VTE, some studies have shown that more than half and nearly 79% of high‐risk hospitalized medical patients received no VTE prevention.[19] Among those who received prophylactic therapy, inadequate duration or type was prescribed in nearly 44%.[20] Electronic orders have resulted in improved prophylaxis in some literature reports.[21, 22] One study showed that a physician alert reduced VTE incidence from 4.13 to 2.23 events per 10,000 patients.[21] Our system, combining prompted electronic orders with clinical decision support for ongoing real‐time monitoring for VTE‐P plans appears to have been effective in producing reliable ordering of VTE‐P in both adults and children.