User login

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing Off-Label Drugs

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Defining a Safe Workload for Pediatric Hospitalists

As I write this column, I am on the second leg of an overnight flight back home to Austin, Texas. I think it actually went pretty well, considering my 2-year-old daughter was wide awake after sleeping for the first three hours of this 14-hour odyssey. The remainder of the trip is a blur of awkward sleep positions interspersed with brief periods of semilucidity. Those of you with first-hand knowledge of what this experience is like might be feeling sorry for me, but you shouldn’t. I am returning from a “why don’t I live here” kind of vacation week in Hawaii. The rest of you are probably wondering how anyone could write a coherent column at this point, which is fair, but to which I would reply: Aren’t all hospitalists expected to function at high levels during periods of sleep deprivation?

While the issue of resident duty-hours has been discussed endlessly and studied increasingly, in terms of effects on outcomes, I am surprised there has not been more discussion surrounding the concept of attending duty-hours. The subject might not always be phrased to include the term “duty-hours,” but it seems that when it comes to scheduling, strong opinions come out in my group when the duration of, frequency of, or time off between night shifts are brought up. And when it comes to safety, I am certain sleep deprivation and sleep inertia (that period of haziness immediately after being awakened in the middle of the night) have led to questionable decisions on my part.

Why? Well...

So why do pediatric hospitalists avoid the issue of sleep hygiene, work schedules, and clinical impact? I think the reasons are multifactorial.

First, there are definitely individual variations in how all of us tolerate this work, and I suspect some of this is based on such traits as age and general ability to adapt to uncomfortable circadian flip-flops. I will admit that every time I wake up achy after a call night, I begin to wonder if I will be able to handle this in 10 to 15 years.

Second, I think pediatric HM as a field has not yet explored this topic fully because we are young both in terms of chronological age as well as nocturnal work-years. The work has not yet aged us to the point of making this a critical issue. We’re also somewhat behind our adult-hospitalist colleagues in terms of the volume of nocturnal work. Adult HM groups have long explored different shift schedules (seven-on/seven-off, day/evening/overnight distribution, etc.) because they routinely cover large services of more than 100 patients in large hospitals with more than 500 beds. In pediatrics, most of us operate in small community hospital settings or large academic centers where the nightly in-house quantity of work is relatively low, mitigated by the smaller size of most community programs and the presence of residents in most large children’s hospitals.

But I see this as an important issue for us to define: the imperative to define safe, round-the-clock clinical care and sustainable careers. Although we will need to learn from other fields, HM is somewhat different from other types of 24/7 medicine in that we require more continuity in our daytime work, which also carries over to night shifts both in terms of how the schedule is made as well as the benefit on the clinical side. The need for continuity adds an extra degree of difficulty in creating and studying different schedules that try to optimize nocturnal functioning.

Clarity, Please

Unfortunately, those looking for evidence-based, or even consensus-based, solutions might have to wait. A recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine does a nice job of synthesizing the literature and highlights the lack of clear answers for what kind of shift schedules work best.1

In the absence of scientific solutions, it might be too easy to say that we need “more research,” because what doesn’t need more research? (OK, we don’t need more research on interventions for bronchiolitis.) But in the same manner in which pediatric hospitalists have taken the lead in defining a night curriculum for residents (congratulations, Becky Blankenburg, on winning the Ray E. Helfer award in pediatric education), I believe there is an opportunity to improve circadian functioning for all hospital-based physicians, but more specifically attendings. This is even more important as residents work less and a 24/7 attending presence becomes the norm in teaching facilities. While the link between safety and fatigue may have been seen as a nonissue in past decades, I think that in our current era, this is something that we own and/or will be asked to define in the near future.

In the meantime, I think we’re left to our own schedules. And in defense of all schedulers like me out there, I will say that there are no proven solutions, so local culture will predominate. Different groups with different personalities and family makeups will have varying preferences. Smaller groups will tend to have longer shift times with less flexibility in “swing”-type midday or evening shifts, while larger groups might have increased flexibility in defining different shifts at the expense of added complexity in terms of creating a schedule with no gaps.

As we come up with more rules about night shifts, such as “clockwise” scheduling of day-evening-overnight shifts, single versus clustered nights based on frequency, and days off after night shifts, the more complex and awkward our Tetris-like schedule will become. I predict that this is something hospitalists will begin to think about more, with a necessary push for safe and sustainable schedules. In the short-term, allowing for financial and structural wiggle room in the scheduling process (i.e. adjusting shift patterns and differential pay for night work) might be the most balanced approach for the immediate future.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

As I write this column, I am on the second leg of an overnight flight back home to Austin, Texas. I think it actually went pretty well, considering my 2-year-old daughter was wide awake after sleeping for the first three hours of this 14-hour odyssey. The remainder of the trip is a blur of awkward sleep positions interspersed with brief periods of semilucidity. Those of you with first-hand knowledge of what this experience is like might be feeling sorry for me, but you shouldn’t. I am returning from a “why don’t I live here” kind of vacation week in Hawaii. The rest of you are probably wondering how anyone could write a coherent column at this point, which is fair, but to which I would reply: Aren’t all hospitalists expected to function at high levels during periods of sleep deprivation?

While the issue of resident duty-hours has been discussed endlessly and studied increasingly, in terms of effects on outcomes, I am surprised there has not been more discussion surrounding the concept of attending duty-hours. The subject might not always be phrased to include the term “duty-hours,” but it seems that when it comes to scheduling, strong opinions come out in my group when the duration of, frequency of, or time off between night shifts are brought up. And when it comes to safety, I am certain sleep deprivation and sleep inertia (that period of haziness immediately after being awakened in the middle of the night) have led to questionable decisions on my part.

Why? Well...

So why do pediatric hospitalists avoid the issue of sleep hygiene, work schedules, and clinical impact? I think the reasons are multifactorial.

First, there are definitely individual variations in how all of us tolerate this work, and I suspect some of this is based on such traits as age and general ability to adapt to uncomfortable circadian flip-flops. I will admit that every time I wake up achy after a call night, I begin to wonder if I will be able to handle this in 10 to 15 years.

Second, I think pediatric HM as a field has not yet explored this topic fully because we are young both in terms of chronological age as well as nocturnal work-years. The work has not yet aged us to the point of making this a critical issue. We’re also somewhat behind our adult-hospitalist colleagues in terms of the volume of nocturnal work. Adult HM groups have long explored different shift schedules (seven-on/seven-off, day/evening/overnight distribution, etc.) because they routinely cover large services of more than 100 patients in large hospitals with more than 500 beds. In pediatrics, most of us operate in small community hospital settings or large academic centers where the nightly in-house quantity of work is relatively low, mitigated by the smaller size of most community programs and the presence of residents in most large children’s hospitals.

But I see this as an important issue for us to define: the imperative to define safe, round-the-clock clinical care and sustainable careers. Although we will need to learn from other fields, HM is somewhat different from other types of 24/7 medicine in that we require more continuity in our daytime work, which also carries over to night shifts both in terms of how the schedule is made as well as the benefit on the clinical side. The need for continuity adds an extra degree of difficulty in creating and studying different schedules that try to optimize nocturnal functioning.

Clarity, Please

Unfortunately, those looking for evidence-based, or even consensus-based, solutions might have to wait. A recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine does a nice job of synthesizing the literature and highlights the lack of clear answers for what kind of shift schedules work best.1

In the absence of scientific solutions, it might be too easy to say that we need “more research,” because what doesn’t need more research? (OK, we don’t need more research on interventions for bronchiolitis.) But in the same manner in which pediatric hospitalists have taken the lead in defining a night curriculum for residents (congratulations, Becky Blankenburg, on winning the Ray E. Helfer award in pediatric education), I believe there is an opportunity to improve circadian functioning for all hospital-based physicians, but more specifically attendings. This is even more important as residents work less and a 24/7 attending presence becomes the norm in teaching facilities. While the link between safety and fatigue may have been seen as a nonissue in past decades, I think that in our current era, this is something that we own and/or will be asked to define in the near future.

In the meantime, I think we’re left to our own schedules. And in defense of all schedulers like me out there, I will say that there are no proven solutions, so local culture will predominate. Different groups with different personalities and family makeups will have varying preferences. Smaller groups will tend to have longer shift times with less flexibility in “swing”-type midday or evening shifts, while larger groups might have increased flexibility in defining different shifts at the expense of added complexity in terms of creating a schedule with no gaps.

As we come up with more rules about night shifts, such as “clockwise” scheduling of day-evening-overnight shifts, single versus clustered nights based on frequency, and days off after night shifts, the more complex and awkward our Tetris-like schedule will become. I predict that this is something hospitalists will begin to think about more, with a necessary push for safe and sustainable schedules. In the short-term, allowing for financial and structural wiggle room in the scheduling process (i.e. adjusting shift patterns and differential pay for night work) might be the most balanced approach for the immediate future.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

As I write this column, I am on the second leg of an overnight flight back home to Austin, Texas. I think it actually went pretty well, considering my 2-year-old daughter was wide awake after sleeping for the first three hours of this 14-hour odyssey. The remainder of the trip is a blur of awkward sleep positions interspersed with brief periods of semilucidity. Those of you with first-hand knowledge of what this experience is like might be feeling sorry for me, but you shouldn’t. I am returning from a “why don’t I live here” kind of vacation week in Hawaii. The rest of you are probably wondering how anyone could write a coherent column at this point, which is fair, but to which I would reply: Aren’t all hospitalists expected to function at high levels during periods of sleep deprivation?

While the issue of resident duty-hours has been discussed endlessly and studied increasingly, in terms of effects on outcomes, I am surprised there has not been more discussion surrounding the concept of attending duty-hours. The subject might not always be phrased to include the term “duty-hours,” but it seems that when it comes to scheduling, strong opinions come out in my group when the duration of, frequency of, or time off between night shifts are brought up. And when it comes to safety, I am certain sleep deprivation and sleep inertia (that period of haziness immediately after being awakened in the middle of the night) have led to questionable decisions on my part.

Why? Well...

So why do pediatric hospitalists avoid the issue of sleep hygiene, work schedules, and clinical impact? I think the reasons are multifactorial.

First, there are definitely individual variations in how all of us tolerate this work, and I suspect some of this is based on such traits as age and general ability to adapt to uncomfortable circadian flip-flops. I will admit that every time I wake up achy after a call night, I begin to wonder if I will be able to handle this in 10 to 15 years.

Second, I think pediatric HM as a field has not yet explored this topic fully because we are young both in terms of chronological age as well as nocturnal work-years. The work has not yet aged us to the point of making this a critical issue. We’re also somewhat behind our adult-hospitalist colleagues in terms of the volume of nocturnal work. Adult HM groups have long explored different shift schedules (seven-on/seven-off, day/evening/overnight distribution, etc.) because they routinely cover large services of more than 100 patients in large hospitals with more than 500 beds. In pediatrics, most of us operate in small community hospital settings or large academic centers where the nightly in-house quantity of work is relatively low, mitigated by the smaller size of most community programs and the presence of residents in most large children’s hospitals.

But I see this as an important issue for us to define: the imperative to define safe, round-the-clock clinical care and sustainable careers. Although we will need to learn from other fields, HM is somewhat different from other types of 24/7 medicine in that we require more continuity in our daytime work, which also carries over to night shifts both in terms of how the schedule is made as well as the benefit on the clinical side. The need for continuity adds an extra degree of difficulty in creating and studying different schedules that try to optimize nocturnal functioning.

Clarity, Please

Unfortunately, those looking for evidence-based, or even consensus-based, solutions might have to wait. A recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine does a nice job of synthesizing the literature and highlights the lack of clear answers for what kind of shift schedules work best.1

In the absence of scientific solutions, it might be too easy to say that we need “more research,” because what doesn’t need more research? (OK, we don’t need more research on interventions for bronchiolitis.) But in the same manner in which pediatric hospitalists have taken the lead in defining a night curriculum for residents (congratulations, Becky Blankenburg, on winning the Ray E. Helfer award in pediatric education), I believe there is an opportunity to improve circadian functioning for all hospital-based physicians, but more specifically attendings. This is even more important as residents work less and a 24/7 attending presence becomes the norm in teaching facilities. While the link between safety and fatigue may have been seen as a nonissue in past decades, I think that in our current era, this is something that we own and/or will be asked to define in the near future.

In the meantime, I think we’re left to our own schedules. And in defense of all schedulers like me out there, I will say that there are no proven solutions, so local culture will predominate. Different groups with different personalities and family makeups will have varying preferences. Smaller groups will tend to have longer shift times with less flexibility in “swing”-type midday or evening shifts, while larger groups might have increased flexibility in defining different shifts at the expense of added complexity in terms of creating a schedule with no gaps.

As we come up with more rules about night shifts, such as “clockwise” scheduling of day-evening-overnight shifts, single versus clustered nights based on frequency, and days off after night shifts, the more complex and awkward our Tetris-like schedule will become. I predict that this is something hospitalists will begin to think about more, with a necessary push for safe and sustainable schedules. In the short-term, allowing for financial and structural wiggle room in the scheduling process (i.e. adjusting shift patterns and differential pay for night work) might be the most balanced approach for the immediate future.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

Pay-for-Performance Challenged as Best Model for Healthcare

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Accountable-Care Organizations on the Horizon for Hospitalists

Every HM group should look into transitioning from a fee-for-service model to an accountable-care organization (ACO), a leading hospitalist told conference attendees recently at the Third National Accountable Care Organization Congress.

"You need to be tackling it now, but that doesn't mean you need to be aggressively doing it now," Edward Murphy, MD, chairman of Sound Physicians, told eWire days before he spoke at the ACO Congress on Oct. 31 in Los Angeles. "By tackling it, you need to be doing a hard-nosed assessment of what's best for your group and your patients."

Question: Why is the ACO model so difficult in some instances?

Answer: The problem with the healthcare system today is we’ve spent 100 years building up a system that is designed around, and competent at, delivering services for fees. We're really not set up to manage care.

Q: What is the No. 1 thing you want hospitalists to know about ACOs today?

A: Figure out every single day how to improve the care of your patients at a lower cost. And then, how you can demonstrate it in a quantitative and clear way. ACO-style payments are really only a value proposition centered on providing superior outcomes for patients at higher satisfaction for lower cost. That’s a fundamental value that will always be noteworthy.

Q: Is a hospitalist's job to lead the charge toward ACOs, or support those who do?

A: That's the sort of thing that people on the ground don't have to be told. They just know. If I were the leader of a hospitalist group someplace and really thought the smart thing to do was to think about how to move to an accountable-care model … I would know from my discussions with my colleagues, my discussions with hospital executives where everybody was.

Visit our website for more information about ACOs.

Every HM group should look into transitioning from a fee-for-service model to an accountable-care organization (ACO), a leading hospitalist told conference attendees recently at the Third National Accountable Care Organization Congress.

"You need to be tackling it now, but that doesn't mean you need to be aggressively doing it now," Edward Murphy, MD, chairman of Sound Physicians, told eWire days before he spoke at the ACO Congress on Oct. 31 in Los Angeles. "By tackling it, you need to be doing a hard-nosed assessment of what's best for your group and your patients."

Question: Why is the ACO model so difficult in some instances?

Answer: The problem with the healthcare system today is we’ve spent 100 years building up a system that is designed around, and competent at, delivering services for fees. We're really not set up to manage care.

Q: What is the No. 1 thing you want hospitalists to know about ACOs today?

A: Figure out every single day how to improve the care of your patients at a lower cost. And then, how you can demonstrate it in a quantitative and clear way. ACO-style payments are really only a value proposition centered on providing superior outcomes for patients at higher satisfaction for lower cost. That’s a fundamental value that will always be noteworthy.

Q: Is a hospitalist's job to lead the charge toward ACOs, or support those who do?

A: That's the sort of thing that people on the ground don't have to be told. They just know. If I were the leader of a hospitalist group someplace and really thought the smart thing to do was to think about how to move to an accountable-care model … I would know from my discussions with my colleagues, my discussions with hospital executives where everybody was.

Visit our website for more information about ACOs.

Every HM group should look into transitioning from a fee-for-service model to an accountable-care organization (ACO), a leading hospitalist told conference attendees recently at the Third National Accountable Care Organization Congress.

"You need to be tackling it now, but that doesn't mean you need to be aggressively doing it now," Edward Murphy, MD, chairman of Sound Physicians, told eWire days before he spoke at the ACO Congress on Oct. 31 in Los Angeles. "By tackling it, you need to be doing a hard-nosed assessment of what's best for your group and your patients."

Question: Why is the ACO model so difficult in some instances?

Answer: The problem with the healthcare system today is we’ve spent 100 years building up a system that is designed around, and competent at, delivering services for fees. We're really not set up to manage care.

Q: What is the No. 1 thing you want hospitalists to know about ACOs today?

A: Figure out every single day how to improve the care of your patients at a lower cost. And then, how you can demonstrate it in a quantitative and clear way. ACO-style payments are really only a value proposition centered on providing superior outcomes for patients at higher satisfaction for lower cost. That’s a fundamental value that will always be noteworthy.

Q: Is a hospitalist's job to lead the charge toward ACOs, or support those who do?

A: That's the sort of thing that people on the ground don't have to be told. They just know. If I were the leader of a hospitalist group someplace and really thought the smart thing to do was to think about how to move to an accountable-care model … I would know from my discussions with my colleagues, my discussions with hospital executives where everybody was.

Visit our website for more information about ACOs.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Anticoagulant's Receives FDA Approval to Treat Deep Vein Thrombosis, Pulmonary Embolism

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) has won another approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Already green-lighted for use to reduce the risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) after knee or hip replacement surgery—and reduce the risk of stroke in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients—the anticoagulant therapy has been approved for use in the treatment of acute DVT and PE, and to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE after initial treatment. It’s a landmark step that will likely have big implications for hospitalists.

“Xarelto is the first oral anti-clotting drug approved to treat and reduce the recurrence of blood clots since the approval of warfarin nearly 60 years ago,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

—Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, medical director, hospital medicine, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

“Single-drug therapy without the need for parental bridging treatment, or drug-level monitoring, is a breakthrough in the treatment of VTE, and represents a paradigm shift that we have not seen in a long time for a very common emergency room and hospital-based medical condition,” says Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director of hospital medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Ian Jenkins, assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Diego, says factors that will help determine whether a patient is a candidate for rivaroxaban include the ability to pay for it; compliance, because the duration of effect is shorter than it is for warfarin; and good and stable renal function.

“We now have the first approved oral warfarin alternative for VTE, and for appropriate candidates, it's a more convenient if not better treatment,” Dr. Jenkins says. “The main downside is that warfarin remains reversible, and the new drugs are minimally so.”

Dr. Shah predicts a more efficient discharge process, which, for rivaroxaban patients, will no longer include arranging for international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring or time-consuming counseling on taking injections and drug interactions with vitamin-K antagonists.

“That’s a very complex, 30-minute process,” says Dr. Shah, who also who runs Northwestern’s VTE-prevention program. “With a single agent, I think the value here is you don’t need that complex care coordination anymore, and that’s time-saving for a hospitalist.”

Dr. Shah notes coordination of care will still be very important with this indication, especially because the dose for rivaroxaban in the treatment of acute DVT changes from twice a day to once a day starting at Day 21. “Whatever education initiatives we undertake, they have to extend that entire spectrum,” he adds.

Visit our website for more information about treating acute DVT.

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) has won another approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Already green-lighted for use to reduce the risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) after knee or hip replacement surgery—and reduce the risk of stroke in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients—the anticoagulant therapy has been approved for use in the treatment of acute DVT and PE, and to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE after initial treatment. It’s a landmark step that will likely have big implications for hospitalists.

“Xarelto is the first oral anti-clotting drug approved to treat and reduce the recurrence of blood clots since the approval of warfarin nearly 60 years ago,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

—Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, medical director, hospital medicine, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

“Single-drug therapy without the need for parental bridging treatment, or drug-level monitoring, is a breakthrough in the treatment of VTE, and represents a paradigm shift that we have not seen in a long time for a very common emergency room and hospital-based medical condition,” says Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director of hospital medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Ian Jenkins, assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Diego, says factors that will help determine whether a patient is a candidate for rivaroxaban include the ability to pay for it; compliance, because the duration of effect is shorter than it is for warfarin; and good and stable renal function.

“We now have the first approved oral warfarin alternative for VTE, and for appropriate candidates, it's a more convenient if not better treatment,” Dr. Jenkins says. “The main downside is that warfarin remains reversible, and the new drugs are minimally so.”

Dr. Shah predicts a more efficient discharge process, which, for rivaroxaban patients, will no longer include arranging for international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring or time-consuming counseling on taking injections and drug interactions with vitamin-K antagonists.

“That’s a very complex, 30-minute process,” says Dr. Shah, who also who runs Northwestern’s VTE-prevention program. “With a single agent, I think the value here is you don’t need that complex care coordination anymore, and that’s time-saving for a hospitalist.”

Dr. Shah notes coordination of care will still be very important with this indication, especially because the dose for rivaroxaban in the treatment of acute DVT changes from twice a day to once a day starting at Day 21. “Whatever education initiatives we undertake, they have to extend that entire spectrum,” he adds.

Visit our website for more information about treating acute DVT.

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) has won another approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Already green-lighted for use to reduce the risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) after knee or hip replacement surgery—and reduce the risk of stroke in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients—the anticoagulant therapy has been approved for use in the treatment of acute DVT and PE, and to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE after initial treatment. It’s a landmark step that will likely have big implications for hospitalists.

“Xarelto is the first oral anti-clotting drug approved to treat and reduce the recurrence of blood clots since the approval of warfarin nearly 60 years ago,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

—Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, medical director, hospital medicine, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

“Single-drug therapy without the need for parental bridging treatment, or drug-level monitoring, is a breakthrough in the treatment of VTE, and represents a paradigm shift that we have not seen in a long time for a very common emergency room and hospital-based medical condition,” says Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director of hospital medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Ian Jenkins, assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Diego, says factors that will help determine whether a patient is a candidate for rivaroxaban include the ability to pay for it; compliance, because the duration of effect is shorter than it is for warfarin; and good and stable renal function.

“We now have the first approved oral warfarin alternative for VTE, and for appropriate candidates, it's a more convenient if not better treatment,” Dr. Jenkins says. “The main downside is that warfarin remains reversible, and the new drugs are minimally so.”

Dr. Shah predicts a more efficient discharge process, which, for rivaroxaban patients, will no longer include arranging for international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring or time-consuming counseling on taking injections and drug interactions with vitamin-K antagonists.

“That’s a very complex, 30-minute process,” says Dr. Shah, who also who runs Northwestern’s VTE-prevention program. “With a single agent, I think the value here is you don’t need that complex care coordination anymore, and that’s time-saving for a hospitalist.”

Dr. Shah notes coordination of care will still be very important with this indication, especially because the dose for rivaroxaban in the treatment of acute DVT changes from twice a day to once a day starting at Day 21. “Whatever education initiatives we undertake, they have to extend that entire spectrum,” he adds.

Visit our website for more information about treating acute DVT.

Win Whitcomb: Hospitalists Must Grin and Bear the Hospital-Acquired Conditions Program

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

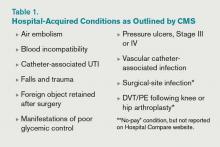

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Hospitalists' Voices to be Heard on Capitol Hill

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people from all parts of the country travel to Washington, D.C., and visit Congress. Regardless of the organizations they represent, almost all of them have one thing in common: They go to Capitol Hill with an “ask.”

Some ask for a vote on a particular piece of legislation; some request funding for their projects. Regardless, there is almost always an ask.

But hospitalists are different, according to SHM Public Policy Committee chair Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, and committee member Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM. They are featured in a new video about “Hospitalists on the Hill,” SHM’s day to meet with members of Congress.

Rather than lobbying or asking for assistance, hospitalists bring solutions to the healthcare problems currently vexing communities throughout the country. By introducing the hospitalist model and its role in quality improvement (QI) to some of the most influential government figures in public health, hospitalists who make the visit to Capitol Hill help to spread some of the best practices in hospital-based healthcare and share their personal experiences at the same time.

“Every constituency that comes in is asking them for something,” Dr. Greeno says in one of the SHM-produced videos. “We don’t ask for anything. We offer. We offer our expertise. We offer to help them make better decisions than they would make otherwise.”

That contribution matters to members of Congress and their healthcare staff. Drs. Greeno and Flansbaum are “Hill Day” veterans who have seen firsthand how legislators and their staff absorb SHM’s message and materials.

“I thought that if we are leaving materials behind, that the minute we walk out of the office, it was going in the trash,” Dr. Greeno says. “That’s not what happens. They read this stuff.”

In 2013, Hospitalists on the Hill will take place May 16, the day before the official start of HM’s annual meeting at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just a few minutes south of Washington, D.C. The agenda is ambitious, starting with a briefing about what to expect when meeting Congress members on Capitol Hill, followed by a full day of meetings with policymakers, regulators, and their staff.

“We spend our day going back and forth, from the Senate side of the Capitol to the House side of the Capitol, in and out of the office buildings, walking the halls of Congress,” Dr. Greeno says. “It’s a blast. It’s so interesting. And we’re getting a chance to sit down and deliver our message.”

For Dr. Flansbaum, it’s an opportunity to promote action in Washington.

“It really brings government to life,” he says. “You realize that, as bottlenecked as things might be sometimes, things have to get done.”

HM13 attendees can sign-up for Hospitalists on the Hill during annual-meeing registration. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine2013.org/onthehill.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people from all parts of the country travel to Washington, D.C., and visit Congress. Regardless of the organizations they represent, almost all of them have one thing in common: They go to Capitol Hill with an “ask.”

Some ask for a vote on a particular piece of legislation; some request funding for their projects. Regardless, there is almost always an ask.

But hospitalists are different, according to SHM Public Policy Committee chair Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, and committee member Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM. They are featured in a new video about “Hospitalists on the Hill,” SHM’s day to meet with members of Congress.

Rather than lobbying or asking for assistance, hospitalists bring solutions to the healthcare problems currently vexing communities throughout the country. By introducing the hospitalist model and its role in quality improvement (QI) to some of the most influential government figures in public health, hospitalists who make the visit to Capitol Hill help to spread some of the best practices in hospital-based healthcare and share their personal experiences at the same time.

“Every constituency that comes in is asking them for something,” Dr. Greeno says in one of the SHM-produced videos. “We don’t ask for anything. We offer. We offer our expertise. We offer to help them make better decisions than they would make otherwise.”

That contribution matters to members of Congress and their healthcare staff. Drs. Greeno and Flansbaum are “Hill Day” veterans who have seen firsthand how legislators and their staff absorb SHM’s message and materials.

“I thought that if we are leaving materials behind, that the minute we walk out of the office, it was going in the trash,” Dr. Greeno says. “That’s not what happens. They read this stuff.”

In 2013, Hospitalists on the Hill will take place May 16, the day before the official start of HM’s annual meeting at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just a few minutes south of Washington, D.C. The agenda is ambitious, starting with a briefing about what to expect when meeting Congress members on Capitol Hill, followed by a full day of meetings with policymakers, regulators, and their staff.

“We spend our day going back and forth, from the Senate side of the Capitol to the House side of the Capitol, in and out of the office buildings, walking the halls of Congress,” Dr. Greeno says. “It’s a blast. It’s so interesting. And we’re getting a chance to sit down and deliver our message.”

For Dr. Flansbaum, it’s an opportunity to promote action in Washington.

“It really brings government to life,” he says. “You realize that, as bottlenecked as things might be sometimes, things have to get done.”

HM13 attendees can sign-up for Hospitalists on the Hill during annual-meeing registration. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine2013.org/onthehill.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people from all parts of the country travel to Washington, D.C., and visit Congress. Regardless of the organizations they represent, almost all of them have one thing in common: They go to Capitol Hill with an “ask.”

Some ask for a vote on a particular piece of legislation; some request funding for their projects. Regardless, there is almost always an ask.

But hospitalists are different, according to SHM Public Policy Committee chair Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, and committee member Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM. They are featured in a new video about “Hospitalists on the Hill,” SHM’s day to meet with members of Congress.

Rather than lobbying or asking for assistance, hospitalists bring solutions to the healthcare problems currently vexing communities throughout the country. By introducing the hospitalist model and its role in quality improvement (QI) to some of the most influential government figures in public health, hospitalists who make the visit to Capitol Hill help to spread some of the best practices in hospital-based healthcare and share their personal experiences at the same time.

“Every constituency that comes in is asking them for something,” Dr. Greeno says in one of the SHM-produced videos. “We don’t ask for anything. We offer. We offer our expertise. We offer to help them make better decisions than they would make otherwise.”

That contribution matters to members of Congress and their healthcare staff. Drs. Greeno and Flansbaum are “Hill Day” veterans who have seen firsthand how legislators and their staff absorb SHM’s message and materials.

“I thought that if we are leaving materials behind, that the minute we walk out of the office, it was going in the trash,” Dr. Greeno says. “That’s not what happens. They read this stuff.”

In 2013, Hospitalists on the Hill will take place May 16, the day before the official start of HM’s annual meeting at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just a few minutes south of Washington, D.C. The agenda is ambitious, starting with a briefing about what to expect when meeting Congress members on Capitol Hill, followed by a full day of meetings with policymakers, regulators, and their staff.

“We spend our day going back and forth, from the Senate side of the Capitol to the House side of the Capitol, in and out of the office buildings, walking the halls of Congress,” Dr. Greeno says. “It’s a blast. It’s so interesting. And we’re getting a chance to sit down and deliver our message.”

For Dr. Flansbaum, it’s an opportunity to promote action in Washington.

“It really brings government to life,” he says. “You realize that, as bottlenecked as things might be sometimes, things have to get done.”

HM13 attendees can sign-up for Hospitalists on the Hill during annual-meeing registration. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine2013.org/onthehill.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

New 'Meaningful Use' Exemption is Valuable Option for Growing Number of Hospitalists

Hospital-based eligible professionals do not qualify for the Medicare or Medicaid electronic health record (EHR) incentive program or the impending payment penalties for not being “meaningful users” of EHR technology.

A hospital-based “eligible professional” (EP) is defined by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as an EP who furnishes 90% or more of their covered professional services in either the inpatient or emergency departments of a hospital. This exemption applies to most hospitalists and recognizes they have very little control over whether their respective institutions invest in this technology.

Although this 90% threshold should qualify most hospitalists for the exemption, it does not tell the entire story. A growing number of hospitalists are spending time rounding in skilled nursing or other post-acute facilities, and some are focusing the entirety of their practice in the post-acute setting. Under the current CMS definition, these hospitalists are not hospital-based and will, therefore, be subject to the upcoming penalties for not being meaningful users of EHR technology.

Contrary to the 90% threshold, the reality for post-acute hospitalists is that when it comes to EHRs, they are no different than their hospital-based colleagues. A hospitalist, irrespective of setting, has very little control over what kind of technology, if any, a facility invests in.