User login

Shaun Frost: Call for Transparency in Healthcare Performance Results to Impact Hospitalists

Policymakers believe that publicly reporting healthcare performance results is essential to improving care delivery. In order to achieve a healthcare system that is consistently reliable, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently recommended that performance transparency be considered a foundational feature of healthcare systems that seek to constantly, systematically, and seamlessly improve.1 The IOM has suggested strategies (see Table 1, right) for producing readily available information on safety, quality, prices and cost, and health outcomes. As these strategies are being deployed, it is essential that hospitalists consider the impact they will have on their personal practice, key stakeholders, and the patients that they serve.

Performance Data Sources

The accessibility of publicly reported healthcare performance information is increasing rapidly. Among HM practitioners, perhaps the most widely recognized data source is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). According to CMS, its performance information on more than 4,000 hospitals is intended to help patients make decisions about where to seek healthcare, as well as encourage hospitals to improve the quality of care they provide.

The information currently reported is extensive and comprehensive (see Table 2, right). Furthermore, CMS continually adds data as new performance measures are created and validated.

Beyond the federal government, private health insurance companies, consortiums of employer purchasers of healthcare (e.g. the Leapfrog Group), and community collaboratives (e.g. Minnesota Community Measurement in the state of Minnesota) are reporting care provider performance information.

In addition, consumer advocacy groups have entered the picture. Earlier this year, Consumer Reports magazine launched an initiative to rate the quality of hospitals (and cardiac surgery groups) through the publication of patient outcomes (central-line-associated bloodstream infections, surgical site infections, readmissions, complications, mortality), patient experience (communications about medications and discharge, and other markers of satisfaction), and hospital best practices (use of EHR, and the appropriate use of abdominal and chest CT scanning). Consumer Reports also provides a composite hospital safety score, and a 36-page technical manual explaining the strategy and methodology behind their ratings.

Public performance reporting is furthermore becoming big business for healthcare entrepreneurs. Castlight Health, with its $181 million in private capital backing, is viewed by some as the “Travelocity of healthcare.” Castlight calls its searchable databases “transparency portals” that allow consumers to understand, before they visit a care provider, what they will be paying and how the care provider ranks on quality and outcomes.

Finally, numerous unregulated Internet sites that employ methodologically questionable practices are reporting on healthcare performance. Many of these sources collect and publish subjective reports of care experiences, with little or no requirement that the reporter confirm the nature of the relationship that they have with the care provider.

Transparency and Key Stakeholders

The hospital that you work in expects you to know how it performs, and to help it improve in the areas over which you have influence. Hospitals monitor publicly reported data because their futures depend on strong performance. As of October 2012, hospital Medicare reimbursement is linked to publicly reported performance measures that were incorporated into CMS’ value-based purchasing (VBP) initiative. Furthermore, hospital market share will be increasingly dependent on performance transparency as consumers and patients utilize these data to make informed decisions about where to seek high-value healthcare.

Patients have a vested interest in knowing how their care providers perform. A recent study by PricewaterhouseCoopers reported that 72% of consumers ranked provider reputation and personal experience as the top drivers of provider choice.2 Furthermore, employers and patients increasingly are demanding access to care affordability information—an interest driven in large part by the increasing popularity of consumer-directed health insurance plans (CDHPs). Under CDHPs, patients save money on premiums in exchange for higher deductibles that are typically paired with healthcare spending accounts. The intent is to increase consumer engagement and awareness of the cost of routine healthcare expenses while protecting against the cost of catastrophic events. It is estimated that 15% to 20% of people with employer-sponsored health insurance are in high-deductible plans, and many believe CDHPs will soon make up the majority of employer-provided coverage.

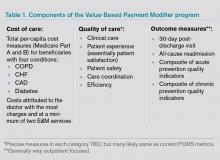

Patients interested in knowing how individual doctors perform will soon have increased access to this type of information as well. For example, CMS also produces a Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor) that offers performance information on individual doctors. Currently, Physician Compare has little detailed information. Expect this to change, however, as Medicare moves forward with developing valid and reliable individual physician performance metrics for its Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program (see “A New Measuring Stick,”).

Under VBPM, doctors will have payment modifiers assigned to their Medicare professional fee claims that will adjust payments based on the value of care that they have delivered historically. For example, it is possible in the future that physicians failing to prescribe ace inhibitors to heart failure patients will be paid less than physicians who universally provide evidence-based, best-practice heart failure care. The measurement period for the calculation of these modifiers begins this year, and hospitalists need to be aware that their performance after this time period might affect the amount of Medicare professional fee reimbursement they receive in the future.

Conclusions

Public performance reporting is a keystone healthcare reform strategy that will influence the behavior and practice patterns of hospitals and hospitalists. Hospitalists should regularly review publicly reported healthcare performance data, and commit to working collaboratively with colleagues to capitalize on improvement opportunities suggested by these data.

Dr. Frost is president of SHM.

References

- Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Institute of Medicine website. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/bestcare. Accessed Nov. 24, 2012.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Health Research Institute. Customer experience in healthcare: the moment of truth. PricewaterhouseCoopers website. Available at: http://www.pwc.com/es_MX/mx/publicaciones/archivo/2012-09-customer-experience-healthcare.pdf. Accessed Nov. 25, 2012.

Policymakers believe that publicly reporting healthcare performance results is essential to improving care delivery. In order to achieve a healthcare system that is consistently reliable, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently recommended that performance transparency be considered a foundational feature of healthcare systems that seek to constantly, systematically, and seamlessly improve.1 The IOM has suggested strategies (see Table 1, right) for producing readily available information on safety, quality, prices and cost, and health outcomes. As these strategies are being deployed, it is essential that hospitalists consider the impact they will have on their personal practice, key stakeholders, and the patients that they serve.

Performance Data Sources

The accessibility of publicly reported healthcare performance information is increasing rapidly. Among HM practitioners, perhaps the most widely recognized data source is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). According to CMS, its performance information on more than 4,000 hospitals is intended to help patients make decisions about where to seek healthcare, as well as encourage hospitals to improve the quality of care they provide.

The information currently reported is extensive and comprehensive (see Table 2, right). Furthermore, CMS continually adds data as new performance measures are created and validated.

Beyond the federal government, private health insurance companies, consortiums of employer purchasers of healthcare (e.g. the Leapfrog Group), and community collaboratives (e.g. Minnesota Community Measurement in the state of Minnesota) are reporting care provider performance information.

In addition, consumer advocacy groups have entered the picture. Earlier this year, Consumer Reports magazine launched an initiative to rate the quality of hospitals (and cardiac surgery groups) through the publication of patient outcomes (central-line-associated bloodstream infections, surgical site infections, readmissions, complications, mortality), patient experience (communications about medications and discharge, and other markers of satisfaction), and hospital best practices (use of EHR, and the appropriate use of abdominal and chest CT scanning). Consumer Reports also provides a composite hospital safety score, and a 36-page technical manual explaining the strategy and methodology behind their ratings.

Public performance reporting is furthermore becoming big business for healthcare entrepreneurs. Castlight Health, with its $181 million in private capital backing, is viewed by some as the “Travelocity of healthcare.” Castlight calls its searchable databases “transparency portals” that allow consumers to understand, before they visit a care provider, what they will be paying and how the care provider ranks on quality and outcomes.

Finally, numerous unregulated Internet sites that employ methodologically questionable practices are reporting on healthcare performance. Many of these sources collect and publish subjective reports of care experiences, with little or no requirement that the reporter confirm the nature of the relationship that they have with the care provider.

Transparency and Key Stakeholders

The hospital that you work in expects you to know how it performs, and to help it improve in the areas over which you have influence. Hospitals monitor publicly reported data because their futures depend on strong performance. As of October 2012, hospital Medicare reimbursement is linked to publicly reported performance measures that were incorporated into CMS’ value-based purchasing (VBP) initiative. Furthermore, hospital market share will be increasingly dependent on performance transparency as consumers and patients utilize these data to make informed decisions about where to seek high-value healthcare.

Patients have a vested interest in knowing how their care providers perform. A recent study by PricewaterhouseCoopers reported that 72% of consumers ranked provider reputation and personal experience as the top drivers of provider choice.2 Furthermore, employers and patients increasingly are demanding access to care affordability information—an interest driven in large part by the increasing popularity of consumer-directed health insurance plans (CDHPs). Under CDHPs, patients save money on premiums in exchange for higher deductibles that are typically paired with healthcare spending accounts. The intent is to increase consumer engagement and awareness of the cost of routine healthcare expenses while protecting against the cost of catastrophic events. It is estimated that 15% to 20% of people with employer-sponsored health insurance are in high-deductible plans, and many believe CDHPs will soon make up the majority of employer-provided coverage.

Patients interested in knowing how individual doctors perform will soon have increased access to this type of information as well. For example, CMS also produces a Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor) that offers performance information on individual doctors. Currently, Physician Compare has little detailed information. Expect this to change, however, as Medicare moves forward with developing valid and reliable individual physician performance metrics for its Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program (see “A New Measuring Stick,”).

Under VBPM, doctors will have payment modifiers assigned to their Medicare professional fee claims that will adjust payments based on the value of care that they have delivered historically. For example, it is possible in the future that physicians failing to prescribe ace inhibitors to heart failure patients will be paid less than physicians who universally provide evidence-based, best-practice heart failure care. The measurement period for the calculation of these modifiers begins this year, and hospitalists need to be aware that their performance after this time period might affect the amount of Medicare professional fee reimbursement they receive in the future.

Conclusions

Public performance reporting is a keystone healthcare reform strategy that will influence the behavior and practice patterns of hospitals and hospitalists. Hospitalists should regularly review publicly reported healthcare performance data, and commit to working collaboratively with colleagues to capitalize on improvement opportunities suggested by these data.

Dr. Frost is president of SHM.

References

- Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Institute of Medicine website. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/bestcare. Accessed Nov. 24, 2012.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Health Research Institute. Customer experience in healthcare: the moment of truth. PricewaterhouseCoopers website. Available at: http://www.pwc.com/es_MX/mx/publicaciones/archivo/2012-09-customer-experience-healthcare.pdf. Accessed Nov. 25, 2012.

Policymakers believe that publicly reporting healthcare performance results is essential to improving care delivery. In order to achieve a healthcare system that is consistently reliable, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently recommended that performance transparency be considered a foundational feature of healthcare systems that seek to constantly, systematically, and seamlessly improve.1 The IOM has suggested strategies (see Table 1, right) for producing readily available information on safety, quality, prices and cost, and health outcomes. As these strategies are being deployed, it is essential that hospitalists consider the impact they will have on their personal practice, key stakeholders, and the patients that they serve.

Performance Data Sources

The accessibility of publicly reported healthcare performance information is increasing rapidly. Among HM practitioners, perhaps the most widely recognized data source is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). According to CMS, its performance information on more than 4,000 hospitals is intended to help patients make decisions about where to seek healthcare, as well as encourage hospitals to improve the quality of care they provide.

The information currently reported is extensive and comprehensive (see Table 2, right). Furthermore, CMS continually adds data as new performance measures are created and validated.

Beyond the federal government, private health insurance companies, consortiums of employer purchasers of healthcare (e.g. the Leapfrog Group), and community collaboratives (e.g. Minnesota Community Measurement in the state of Minnesota) are reporting care provider performance information.

In addition, consumer advocacy groups have entered the picture. Earlier this year, Consumer Reports magazine launched an initiative to rate the quality of hospitals (and cardiac surgery groups) through the publication of patient outcomes (central-line-associated bloodstream infections, surgical site infections, readmissions, complications, mortality), patient experience (communications about medications and discharge, and other markers of satisfaction), and hospital best practices (use of EHR, and the appropriate use of abdominal and chest CT scanning). Consumer Reports also provides a composite hospital safety score, and a 36-page technical manual explaining the strategy and methodology behind their ratings.

Public performance reporting is furthermore becoming big business for healthcare entrepreneurs. Castlight Health, with its $181 million in private capital backing, is viewed by some as the “Travelocity of healthcare.” Castlight calls its searchable databases “transparency portals” that allow consumers to understand, before they visit a care provider, what they will be paying and how the care provider ranks on quality and outcomes.

Finally, numerous unregulated Internet sites that employ methodologically questionable practices are reporting on healthcare performance. Many of these sources collect and publish subjective reports of care experiences, with little or no requirement that the reporter confirm the nature of the relationship that they have with the care provider.

Transparency and Key Stakeholders

The hospital that you work in expects you to know how it performs, and to help it improve in the areas over which you have influence. Hospitals monitor publicly reported data because their futures depend on strong performance. As of October 2012, hospital Medicare reimbursement is linked to publicly reported performance measures that were incorporated into CMS’ value-based purchasing (VBP) initiative. Furthermore, hospital market share will be increasingly dependent on performance transparency as consumers and patients utilize these data to make informed decisions about where to seek high-value healthcare.

Patients have a vested interest in knowing how their care providers perform. A recent study by PricewaterhouseCoopers reported that 72% of consumers ranked provider reputation and personal experience as the top drivers of provider choice.2 Furthermore, employers and patients increasingly are demanding access to care affordability information—an interest driven in large part by the increasing popularity of consumer-directed health insurance plans (CDHPs). Under CDHPs, patients save money on premiums in exchange for higher deductibles that are typically paired with healthcare spending accounts. The intent is to increase consumer engagement and awareness of the cost of routine healthcare expenses while protecting against the cost of catastrophic events. It is estimated that 15% to 20% of people with employer-sponsored health insurance are in high-deductible plans, and many believe CDHPs will soon make up the majority of employer-provided coverage.

Patients interested in knowing how individual doctors perform will soon have increased access to this type of information as well. For example, CMS also produces a Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor) that offers performance information on individual doctors. Currently, Physician Compare has little detailed information. Expect this to change, however, as Medicare moves forward with developing valid and reliable individual physician performance metrics for its Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program (see “A New Measuring Stick,”).

Under VBPM, doctors will have payment modifiers assigned to their Medicare professional fee claims that will adjust payments based on the value of care that they have delivered historically. For example, it is possible in the future that physicians failing to prescribe ace inhibitors to heart failure patients will be paid less than physicians who universally provide evidence-based, best-practice heart failure care. The measurement period for the calculation of these modifiers begins this year, and hospitalists need to be aware that their performance after this time period might affect the amount of Medicare professional fee reimbursement they receive in the future.

Conclusions

Public performance reporting is a keystone healthcare reform strategy that will influence the behavior and practice patterns of hospitals and hospitalists. Hospitalists should regularly review publicly reported healthcare performance data, and commit to working collaboratively with colleagues to capitalize on improvement opportunities suggested by these data.

Dr. Frost is president of SHM.

References

- Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Institute of Medicine website. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/bestcare. Accessed Nov. 24, 2012.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Health Research Institute. Customer experience in healthcare: the moment of truth. PricewaterhouseCoopers website. Available at: http://www.pwc.com/es_MX/mx/publicaciones/archivo/2012-09-customer-experience-healthcare.pdf. Accessed Nov. 25, 2012.

Bipartisan Proposal to Repeal SGR Plan Likely to be Reintroduced

As the Obama administration begins its second term, a great deal of attention is being paid to the advance of its healthcare reform agenda. Long overdue for reform is the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula—an ill-fated attempt to provide predictable control for federal spending on Medicare by providing yearly updates (i.e. reductions) to Medicare’s physician reimbursement rates.

By adjusting the payment rates, the SGR was supposed to help control the cost of healthcare by linking it more closely with national growth and changes in the Medicare-eligible population. With each passing year, however, bipartisan consensus has grown stronger, the message being that a straight, fee-for-service system that is updated annually based on an expenditure target cannot substitute for fundamental delivery system reforms.

Congress has acted to override the SGR’s implementation every year since 2003, with the latest round being a potential 27% gutting of Medicare reimbursement rates. This cycle is not only tiresome, but threatens a massive disruption to physician practices and to seniors’ access to the Medicare program.

“The SGR, while well-intentioned, is flawed, and Congress can provide its temporary override for only so long, while Medicare spending continues to grow,” says Ryan Genzink, PA-C, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and a physician assistant with IPC: The Hospitalist Co. in Grand Rapids, Mich.

Repeal and Reform

Although various SGR repeal bills have been introduced over the years, only one—the Medicare Physician Payment Innovation Act of 2012 (H.R. 5707)—supplements repeal with a realistic plan to move away from the current fee-for-service payment system (and its inherent inefficiencies) toward more cost-effective reimbursement models that are designed to promote quality and value through coordinated patient care.

This bipartisan bill, introduced by U.S. Reps. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.) and Joe Heck, DO (R-Nev.), would repeal the SGR, stabilize payments at current rates for 2013, replace scheduled reductions with positive and predictable updates from 2014 to 2017, and set an aggressive timetable for testing and evaluating new payment systems focused on improving quality and reducing costs (see “Specific Components of the Schwartz-Heck Proposal,” left). The bill is expected to be reintroduced in 2013.

“SHM agrees that it is time finally to eliminate the SGR and move away from the prevailing fee-for-service payment system, which rewards physicians for simply providing more services, to one that provides incentives to deliver higher-quality, cost-effective care to our nation’s seniors,” wrote SHM President Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, in a letter of support last year to Schwartz and Heck, commending them for introducing their bill.

“By providing a menu of options for physician participation, including an alternative, value-driven fee-for-service system for physicians who are not able to participate in one of the new payment and delivery models, the legislation does not force all providers into a ‘one size fits all’ solution, allowing for broader support, innovation, and flexibility,” Dr. Frost said.

Advancing New Reimbursement Models

The Schwartz-Heck bill “gives a timeline for CMS to test and adopt different reimbursement models, which presents advantageous options for hospitalists,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, an SHM Public Policy Committee member, hospitalist, and medical director of the post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “Hospitalists already focus on providing higher-quality, lower-cost care to hospitalized patients in their daily practice. We build effective care transitions to the outpatient and extended care settings. Our strengths are perfectly aligned to help these new, value-based payment models succeed.”

In fact, Dr. Doctoroff notes, Beth Israel is a participant in CMS’ Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization project as well as Massachusetts Blue Cross Blue Shield’s Alternative Quality Contract, both of which use a risk-sharing global payment model in which the hospital and its physician network agree to provide for the healthcare needs of a defined population for a pre-arranged reimbursement amount.

“The global payment model is an attractive one for hospitalists because we play a key role in managing hospitalized patients efficiently and well, while also encouraging collaboration between inpatient and outpatient providers to avoid duplication of services,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “Some bundled payment models, which tie reimbursement to a defined episode of care, also could be advantageous for hospitalists, who coordinate the patient’s care throughout their entire healthcare episode, from inpatient diagnosis through post-discharge.”

Alternative Fee-for-Service System

For physicians who choose not to adopt one of the new reimbursement models, the bill directs CMS to offer an alternative fee-for-service system with incentives for improved quality and lower cost. This alternative would be available to physicians (including hospitalists) who participate in approved quality-reporting options, including the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) or an approved Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program with quality registries. It also would apply to physicians who fall into the top 25% of CMS’ Value-Based Payment Modifier program (VBPM).

Boosting Primary Care

In addition to expediting the rollout of CMS-endorsed alternate payment models, the Schwartz bill recognizes the importance of primary care as the foundation of an effective healthcare delivery system and redresses its undervaluation with a 2.5% reimbursement update for physicians and other healthcare professionals for whom 60% of their Medicare physician fee schedule allowable charges are from a designated set of primary-care, preventive, and care-coordination codes.

“SHM specifically advocated for the inclusion of primary-care billing codes that hospitalists use,” Dr. Doctoroff says, “including hospital inpatient visits and observational services.”

“Of all the attempts to deal with the SGR over the past several years, Rep. Schwartz’s bill makes the most sense,” Genzink says. “While it doesn’t answer all of the healthcare system’s problems, it encapsulates many of the goals of reform—especially the shift from fee-for-service toward a payment system based on quality and outcomes. It recognizes that no one model will work for all physicians and offers the flexibility of multiple pathways. And it has bipartisan support, which seems to be a rarity these days.”

Chris Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

As the Obama administration begins its second term, a great deal of attention is being paid to the advance of its healthcare reform agenda. Long overdue for reform is the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula—an ill-fated attempt to provide predictable control for federal spending on Medicare by providing yearly updates (i.e. reductions) to Medicare’s physician reimbursement rates.

By adjusting the payment rates, the SGR was supposed to help control the cost of healthcare by linking it more closely with national growth and changes in the Medicare-eligible population. With each passing year, however, bipartisan consensus has grown stronger, the message being that a straight, fee-for-service system that is updated annually based on an expenditure target cannot substitute for fundamental delivery system reforms.

Congress has acted to override the SGR’s implementation every year since 2003, with the latest round being a potential 27% gutting of Medicare reimbursement rates. This cycle is not only tiresome, but threatens a massive disruption to physician practices and to seniors’ access to the Medicare program.

“The SGR, while well-intentioned, is flawed, and Congress can provide its temporary override for only so long, while Medicare spending continues to grow,” says Ryan Genzink, PA-C, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and a physician assistant with IPC: The Hospitalist Co. in Grand Rapids, Mich.

Repeal and Reform

Although various SGR repeal bills have been introduced over the years, only one—the Medicare Physician Payment Innovation Act of 2012 (H.R. 5707)—supplements repeal with a realistic plan to move away from the current fee-for-service payment system (and its inherent inefficiencies) toward more cost-effective reimbursement models that are designed to promote quality and value through coordinated patient care.

This bipartisan bill, introduced by U.S. Reps. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.) and Joe Heck, DO (R-Nev.), would repeal the SGR, stabilize payments at current rates for 2013, replace scheduled reductions with positive and predictable updates from 2014 to 2017, and set an aggressive timetable for testing and evaluating new payment systems focused on improving quality and reducing costs (see “Specific Components of the Schwartz-Heck Proposal,” left). The bill is expected to be reintroduced in 2013.

“SHM agrees that it is time finally to eliminate the SGR and move away from the prevailing fee-for-service payment system, which rewards physicians for simply providing more services, to one that provides incentives to deliver higher-quality, cost-effective care to our nation’s seniors,” wrote SHM President Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, in a letter of support last year to Schwartz and Heck, commending them for introducing their bill.

“By providing a menu of options for physician participation, including an alternative, value-driven fee-for-service system for physicians who are not able to participate in one of the new payment and delivery models, the legislation does not force all providers into a ‘one size fits all’ solution, allowing for broader support, innovation, and flexibility,” Dr. Frost said.

Advancing New Reimbursement Models

The Schwartz-Heck bill “gives a timeline for CMS to test and adopt different reimbursement models, which presents advantageous options for hospitalists,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, an SHM Public Policy Committee member, hospitalist, and medical director of the post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “Hospitalists already focus on providing higher-quality, lower-cost care to hospitalized patients in their daily practice. We build effective care transitions to the outpatient and extended care settings. Our strengths are perfectly aligned to help these new, value-based payment models succeed.”

In fact, Dr. Doctoroff notes, Beth Israel is a participant in CMS’ Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization project as well as Massachusetts Blue Cross Blue Shield’s Alternative Quality Contract, both of which use a risk-sharing global payment model in which the hospital and its physician network agree to provide for the healthcare needs of a defined population for a pre-arranged reimbursement amount.

“The global payment model is an attractive one for hospitalists because we play a key role in managing hospitalized patients efficiently and well, while also encouraging collaboration between inpatient and outpatient providers to avoid duplication of services,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “Some bundled payment models, which tie reimbursement to a defined episode of care, also could be advantageous for hospitalists, who coordinate the patient’s care throughout their entire healthcare episode, from inpatient diagnosis through post-discharge.”

Alternative Fee-for-Service System

For physicians who choose not to adopt one of the new reimbursement models, the bill directs CMS to offer an alternative fee-for-service system with incentives for improved quality and lower cost. This alternative would be available to physicians (including hospitalists) who participate in approved quality-reporting options, including the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) or an approved Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program with quality registries. It also would apply to physicians who fall into the top 25% of CMS’ Value-Based Payment Modifier program (VBPM).

Boosting Primary Care

In addition to expediting the rollout of CMS-endorsed alternate payment models, the Schwartz bill recognizes the importance of primary care as the foundation of an effective healthcare delivery system and redresses its undervaluation with a 2.5% reimbursement update for physicians and other healthcare professionals for whom 60% of their Medicare physician fee schedule allowable charges are from a designated set of primary-care, preventive, and care-coordination codes.

“SHM specifically advocated for the inclusion of primary-care billing codes that hospitalists use,” Dr. Doctoroff says, “including hospital inpatient visits and observational services.”

“Of all the attempts to deal with the SGR over the past several years, Rep. Schwartz’s bill makes the most sense,” Genzink says. “While it doesn’t answer all of the healthcare system’s problems, it encapsulates many of the goals of reform—especially the shift from fee-for-service toward a payment system based on quality and outcomes. It recognizes that no one model will work for all physicians and offers the flexibility of multiple pathways. And it has bipartisan support, which seems to be a rarity these days.”

Chris Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

As the Obama administration begins its second term, a great deal of attention is being paid to the advance of its healthcare reform agenda. Long overdue for reform is the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula—an ill-fated attempt to provide predictable control for federal spending on Medicare by providing yearly updates (i.e. reductions) to Medicare’s physician reimbursement rates.

By adjusting the payment rates, the SGR was supposed to help control the cost of healthcare by linking it more closely with national growth and changes in the Medicare-eligible population. With each passing year, however, bipartisan consensus has grown stronger, the message being that a straight, fee-for-service system that is updated annually based on an expenditure target cannot substitute for fundamental delivery system reforms.

Congress has acted to override the SGR’s implementation every year since 2003, with the latest round being a potential 27% gutting of Medicare reimbursement rates. This cycle is not only tiresome, but threatens a massive disruption to physician practices and to seniors’ access to the Medicare program.

“The SGR, while well-intentioned, is flawed, and Congress can provide its temporary override for only so long, while Medicare spending continues to grow,” says Ryan Genzink, PA-C, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and a physician assistant with IPC: The Hospitalist Co. in Grand Rapids, Mich.

Repeal and Reform

Although various SGR repeal bills have been introduced over the years, only one—the Medicare Physician Payment Innovation Act of 2012 (H.R. 5707)—supplements repeal with a realistic plan to move away from the current fee-for-service payment system (and its inherent inefficiencies) toward more cost-effective reimbursement models that are designed to promote quality and value through coordinated patient care.

This bipartisan bill, introduced by U.S. Reps. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.) and Joe Heck, DO (R-Nev.), would repeal the SGR, stabilize payments at current rates for 2013, replace scheduled reductions with positive and predictable updates from 2014 to 2017, and set an aggressive timetable for testing and evaluating new payment systems focused on improving quality and reducing costs (see “Specific Components of the Schwartz-Heck Proposal,” left). The bill is expected to be reintroduced in 2013.

“SHM agrees that it is time finally to eliminate the SGR and move away from the prevailing fee-for-service payment system, which rewards physicians for simply providing more services, to one that provides incentives to deliver higher-quality, cost-effective care to our nation’s seniors,” wrote SHM President Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, in a letter of support last year to Schwartz and Heck, commending them for introducing their bill.

“By providing a menu of options for physician participation, including an alternative, value-driven fee-for-service system for physicians who are not able to participate in one of the new payment and delivery models, the legislation does not force all providers into a ‘one size fits all’ solution, allowing for broader support, innovation, and flexibility,” Dr. Frost said.

Advancing New Reimbursement Models

The Schwartz-Heck bill “gives a timeline for CMS to test and adopt different reimbursement models, which presents advantageous options for hospitalists,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, an SHM Public Policy Committee member, hospitalist, and medical director of the post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “Hospitalists already focus on providing higher-quality, lower-cost care to hospitalized patients in their daily practice. We build effective care transitions to the outpatient and extended care settings. Our strengths are perfectly aligned to help these new, value-based payment models succeed.”

In fact, Dr. Doctoroff notes, Beth Israel is a participant in CMS’ Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization project as well as Massachusetts Blue Cross Blue Shield’s Alternative Quality Contract, both of which use a risk-sharing global payment model in which the hospital and its physician network agree to provide for the healthcare needs of a defined population for a pre-arranged reimbursement amount.

“The global payment model is an attractive one for hospitalists because we play a key role in managing hospitalized patients efficiently and well, while also encouraging collaboration between inpatient and outpatient providers to avoid duplication of services,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “Some bundled payment models, which tie reimbursement to a defined episode of care, also could be advantageous for hospitalists, who coordinate the patient’s care throughout their entire healthcare episode, from inpatient diagnosis through post-discharge.”

Alternative Fee-for-Service System

For physicians who choose not to adopt one of the new reimbursement models, the bill directs CMS to offer an alternative fee-for-service system with incentives for improved quality and lower cost. This alternative would be available to physicians (including hospitalists) who participate in approved quality-reporting options, including the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) or an approved Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program with quality registries. It also would apply to physicians who fall into the top 25% of CMS’ Value-Based Payment Modifier program (VBPM).

Boosting Primary Care

In addition to expediting the rollout of CMS-endorsed alternate payment models, the Schwartz bill recognizes the importance of primary care as the foundation of an effective healthcare delivery system and redresses its undervaluation with a 2.5% reimbursement update for physicians and other healthcare professionals for whom 60% of their Medicare physician fee schedule allowable charges are from a designated set of primary-care, preventive, and care-coordination codes.

“SHM specifically advocated for the inclusion of primary-care billing codes that hospitalists use,” Dr. Doctoroff says, “including hospital inpatient visits and observational services.”

“Of all the attempts to deal with the SGR over the past several years, Rep. Schwartz’s bill makes the most sense,” Genzink says. “While it doesn’t answer all of the healthcare system’s problems, it encapsulates many of the goals of reform—especially the shift from fee-for-service toward a payment system based on quality and outcomes. It recognizes that no one model will work for all physicians and offers the flexibility of multiple pathways. And it has bipartisan support, which seems to be a rarity these days.”

Chris Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

Performance Disconnect: Measures Don’t Improve Hospitals’ Readmissions Experience

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.

“The challenge is to find a way to connect the dots between the core measures and readmissions,” he says.

Learn more about the four "core" heart failure quality measures for hospitals by visiting the Resource Rooms on the SHM website, or check out this 80-page implementation guide, “Improving Heart Failure Care for Hospitalized Patients [PDF],” also available on SHM’s website.

Read The Hospitalist columnist Win Whitcomb’s take on readmissions penalty programs.

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.

“The challenge is to find a way to connect the dots between the core measures and readmissions,” he says.

Learn more about the four "core" heart failure quality measures for hospitals by visiting the Resource Rooms on the SHM website, or check out this 80-page implementation guide, “Improving Heart Failure Care for Hospitalized Patients [PDF],” also available on SHM’s website.

Read The Hospitalist columnist Win Whitcomb’s take on readmissions penalty programs.

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.

“The challenge is to find a way to connect the dots between the core measures and readmissions,” he says.

Learn more about the four "core" heart failure quality measures for hospitals by visiting the Resource Rooms on the SHM website, or check out this 80-page implementation guide, “Improving Heart Failure Care for Hospitalized Patients [PDF],” also available on SHM’s website.

Read The Hospitalist columnist Win Whitcomb’s take on readmissions penalty programs.

Report Outlines Ways Hospital Medicine Can Redefine Healthcare Delivery

There are 10 industry-changing recommendations in the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Suggestions include reforming payment, adopting digital infrastructure, and improving the continuity of care. And to Brent James, MD, all of those recommendations are areas in which hospitalists can help lead healthcare from fee-for-service to an organized-care model.

Dr. James, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and chief quality officer at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, says hospitalists can be linchpins to that hoped-for sea change because the specialty’s growth the past 15 years shows that physicians taking a collaborative, evidence-based approach to patient care can improve outcomes and lower costs.

“In some sense, the hospitalist movement triggered [the move to organized care],” says Dr. James, one of the IOM report’s authors. “You started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. Pieces started to kind of fall into place underneath it. So I regard this as … [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold.”

The report estimates the national cost of unnecessary or wasteful healthcare at $750 billion per year. Published in September, the report was crafted by a nationwide committee of healthcare leaders, including hospitalist and medical researcher David Meltzer, MD, PhD, chief of University of Chicago’s Division of Hospital Medicine and director of the Center for Health and Social Sciences in Chicago.

Dr. Meltzer says that for a relatively young specialty, hospitalists have been “remarkably forward-looking.” The specialty, in his view, has embraced teamwork, digital infrastructure, and quality initiatives. As the U.S. healthcare system evolves, he notes, HM leaders need to keep that mentality. Hospitalists are confronted daily with a combination of sicker patients and more treatment options, and making the right decisions is paramount to a “learning healthcare system,” Dr. Meltzer adds.

“As the database of options grows, decision-making becomes more difficult,” he says. “We have an important role to play in how to think about trying to control costs.”

Gary Kaplan, MD, FACP, FACMPE, FACPE, chairman and chief executive officer of Virginia Mason Health System in Seattle, agrees that HM’s priorities dovetail nicely with reform efforts. He hopes the IOM report’s findings will serve as a springboard for hospitalists to further spearhead improvements.

In particular, Dr. Kaplan notes that healthcare delivery organizations should develop, implement, and fine-tune their “systems, engineering tools, and process-improvement methods.” Such changes would help “eliminate inefficiencies, remove unnecessary burdens on clinicians and staff, enhance patient experience, and improve patient health outcomes,” he says.

“The hospitalists and the care teams with which the hospitalist connects are very critical to streamlining operations,” Dr. Kaplan adds.

Dr. James, who has long championed process improvement as the key to improved clinical outcomes, says that extending the hospitalist model throughout healthcare can only have good results. He preaches the implementation of standardized protocols and sees hospitalists as natural torchbearers for the cause.

“When you start to focus on process—our old jargon for it was ‘continuum of care’—it forces you to patient-centered care,” he says. “Instead of building your care around the physicians, or around the hospital, or around the technology, you build the care around the patient.”

Dr. James has heard physicians say protocols are too rigid and do not improve patient care. He disagrees—vehemently.

—Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and chief quality officer, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City

“It’s not just that we allow, or even that we encourage, we demand that you modify [the protocol] for individual patient needs,” he says. “What I have is a standard process of care. That means that you don’t have to bird-dog every little step. I take my most important resource—a trained, expert mind—and focus it on that relatively small set of problems that need to be modified. We’ve found that it massively improves patient outcomes.”

Many of the IOM report’s complaints about unnecessary testing, poor communication, and inefficient care delivery connect with the quality, patient-safety, and practice-management improvements HM groups already push, Dr. Kaplan adds. To advance healthcare delivery’s evolution, hospitalists should view the task of reform as an opportunity, not a challenge.

“There are very powerful opportunities for the hospitalist now to have great impact,” he says. “To not just be the passive participants in a broken and dysfunctional system, but in many ways, [to be] one of the architects of an improved care system going forward.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

There are 10 industry-changing recommendations in the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Suggestions include reforming payment, adopting digital infrastructure, and improving the continuity of care. And to Brent James, MD, all of those recommendations are areas in which hospitalists can help lead healthcare from fee-for-service to an organized-care model.

Dr. James, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and chief quality officer at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, says hospitalists can be linchpins to that hoped-for sea change because the specialty’s growth the past 15 years shows that physicians taking a collaborative, evidence-based approach to patient care can improve outcomes and lower costs.

“In some sense, the hospitalist movement triggered [the move to organized care],” says Dr. James, one of the IOM report’s authors. “You started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. Pieces started to kind of fall into place underneath it. So I regard this as … [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold.”

The report estimates the national cost of unnecessary or wasteful healthcare at $750 billion per year. Published in September, the report was crafted by a nationwide committee of healthcare leaders, including hospitalist and medical researcher David Meltzer, MD, PhD, chief of University of Chicago’s Division of Hospital Medicine and director of the Center for Health and Social Sciences in Chicago.

Dr. Meltzer says that for a relatively young specialty, hospitalists have been “remarkably forward-looking.” The specialty, in his view, has embraced teamwork, digital infrastructure, and quality initiatives. As the U.S. healthcare system evolves, he notes, HM leaders need to keep that mentality. Hospitalists are confronted daily with a combination of sicker patients and more treatment options, and making the right decisions is paramount to a “learning healthcare system,” Dr. Meltzer adds.

“As the database of options grows, decision-making becomes more difficult,” he says. “We have an important role to play in how to think about trying to control costs.”

Gary Kaplan, MD, FACP, FACMPE, FACPE, chairman and chief executive officer of Virginia Mason Health System in Seattle, agrees that HM’s priorities dovetail nicely with reform efforts. He hopes the IOM report’s findings will serve as a springboard for hospitalists to further spearhead improvements.

In particular, Dr. Kaplan notes that healthcare delivery organizations should develop, implement, and fine-tune their “systems, engineering tools, and process-improvement methods.” Such changes would help “eliminate inefficiencies, remove unnecessary burdens on clinicians and staff, enhance patient experience, and improve patient health outcomes,” he says.

“The hospitalists and the care teams with which the hospitalist connects are very critical to streamlining operations,” Dr. Kaplan adds.

Dr. James, who has long championed process improvement as the key to improved clinical outcomes, says that extending the hospitalist model throughout healthcare can only have good results. He preaches the implementation of standardized protocols and sees hospitalists as natural torchbearers for the cause.

“When you start to focus on process—our old jargon for it was ‘continuum of care’—it forces you to patient-centered care,” he says. “Instead of building your care around the physicians, or around the hospital, or around the technology, you build the care around the patient.”

Dr. James has heard physicians say protocols are too rigid and do not improve patient care. He disagrees—vehemently.

—Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and chief quality officer, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City

“It’s not just that we allow, or even that we encourage, we demand that you modify [the protocol] for individual patient needs,” he says. “What I have is a standard process of care. That means that you don’t have to bird-dog every little step. I take my most important resource—a trained, expert mind—and focus it on that relatively small set of problems that need to be modified. We’ve found that it massively improves patient outcomes.”

Many of the IOM report’s complaints about unnecessary testing, poor communication, and inefficient care delivery connect with the quality, patient-safety, and practice-management improvements HM groups already push, Dr. Kaplan adds. To advance healthcare delivery’s evolution, hospitalists should view the task of reform as an opportunity, not a challenge.

“There are very powerful opportunities for the hospitalist now to have great impact,” he says. “To not just be the passive participants in a broken and dysfunctional system, but in many ways, [to be] one of the architects of an improved care system going forward.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

There are 10 industry-changing recommendations in the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Suggestions include reforming payment, adopting digital infrastructure, and improving the continuity of care. And to Brent James, MD, all of those recommendations are areas in which hospitalists can help lead healthcare from fee-for-service to an organized-care model.

Dr. James, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and chief quality officer at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, says hospitalists can be linchpins to that hoped-for sea change because the specialty’s growth the past 15 years shows that physicians taking a collaborative, evidence-based approach to patient care can improve outcomes and lower costs.

“In some sense, the hospitalist movement triggered [the move to organized care],” says Dr. James, one of the IOM report’s authors. “You started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. Pieces started to kind of fall into place underneath it. So I regard this as … [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold.”

The report estimates the national cost of unnecessary or wasteful healthcare at $750 billion per year. Published in September, the report was crafted by a nationwide committee of healthcare leaders, including hospitalist and medical researcher David Meltzer, MD, PhD, chief of University of Chicago’s Division of Hospital Medicine and director of the Center for Health and Social Sciences in Chicago.

Dr. Meltzer says that for a relatively young specialty, hospitalists have been “remarkably forward-looking.” The specialty, in his view, has embraced teamwork, digital infrastructure, and quality initiatives. As the U.S. healthcare system evolves, he notes, HM leaders need to keep that mentality. Hospitalists are confronted daily with a combination of sicker patients and more treatment options, and making the right decisions is paramount to a “learning healthcare system,” Dr. Meltzer adds.

“As the database of options grows, decision-making becomes more difficult,” he says. “We have an important role to play in how to think about trying to control costs.”

Gary Kaplan, MD, FACP, FACMPE, FACPE, chairman and chief executive officer of Virginia Mason Health System in Seattle, agrees that HM’s priorities dovetail nicely with reform efforts. He hopes the IOM report’s findings will serve as a springboard for hospitalists to further spearhead improvements.

In particular, Dr. Kaplan notes that healthcare delivery organizations should develop, implement, and fine-tune their “systems, engineering tools, and process-improvement methods.” Such changes would help “eliminate inefficiencies, remove unnecessary burdens on clinicians and staff, enhance patient experience, and improve patient health outcomes,” he says.

“The hospitalists and the care teams with which the hospitalist connects are very critical to streamlining operations,” Dr. Kaplan adds.

Dr. James, who has long championed process improvement as the key to improved clinical outcomes, says that extending the hospitalist model throughout healthcare can only have good results. He preaches the implementation of standardized protocols and sees hospitalists as natural torchbearers for the cause.

“When you start to focus on process—our old jargon for it was ‘continuum of care’—it forces you to patient-centered care,” he says. “Instead of building your care around the physicians, or around the hospital, or around the technology, you build the care around the patient.”

Dr. James has heard physicians say protocols are too rigid and do not improve patient care. He disagrees—vehemently.

—Brent James, MD, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and chief quality officer, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City

“It’s not just that we allow, or even that we encourage, we demand that you modify [the protocol] for individual patient needs,” he says. “What I have is a standard process of care. That means that you don’t have to bird-dog every little step. I take my most important resource—a trained, expert mind—and focus it on that relatively small set of problems that need to be modified. We’ve found that it massively improves patient outcomes.”

Many of the IOM report’s complaints about unnecessary testing, poor communication, and inefficient care delivery connect with the quality, patient-safety, and practice-management improvements HM groups already push, Dr. Kaplan adds. To advance healthcare delivery’s evolution, hospitalists should view the task of reform as an opportunity, not a challenge.

“There are very powerful opportunities for the hospitalist now to have great impact,” he says. “To not just be the passive participants in a broken and dysfunctional system, but in many ways, [to be] one of the architects of an improved care system going forward.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Soaring Healthcare Expenses Draw Attention to Price Transparency As Cost Control

As efforts intensify to rein in the soaring cost of healthcare, greater attention is being paid to the cost-control potential of price transparency. Initially envisioned as a consumer-driven dynamic, price transparency beckons physicians to consider much more seriously the cost impacts of their diagnostic and treatment decisions.

Consumer-Driven Approach

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regards price transparency as an important weapon in its armamentarium of “value-driven” approaches to drive down the cost of healthcare. By unleashing the energy of the savvy shopper and empowering consumers with the ability to compare the price and quality of healthcare services, they can make informed choices of their doctors and hospitals. In turn, HHS hopes to motivate the entire system to provide better care for less money.

That “empowered consumerism” principle is the guiding impetus for the Affordable Care Act’s state-regulated health insurance exchange apparatus, which, beginning in 2014, will present a side-by-side comparison of health plan choices, premium costs, and out-of-pocket copays in a way that is designed to help consumers shop for better-value health plans.

Some health plans are using price transparency to nudge consumers to choose lower-cost healthcare service options. Anthem BlueCross BlueShield, for example, has launched the Compass SmartShopper program (www.compasssmartshopper.com), which gives members in New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Indiana $50 to $200 if they get a diagnostic test or surgical procedure at a less expensive facility. Anthem notes that the cost for the same service can vary greatly. For example, hernia repairs range in price from $4,026 to $7,498, and colonoscopies range from $1,450 to $2,973.

New price transparency tools also are available (HealthCareBlueBook.com and FairHealthConsumer.org, for example) to help consumers who face high deductibles or out-of-pocket costs to find “fair prices” for surgeries, hospital stays, doctor visits, and medical tests—and shop accordingly.

Despite these developments, however, there is limited evidence that the “empowered consumerism” approach to price transparency will spur consumers to choose lower-cost providers. Some experts note that many consumers equate higher-cost providers with higher quality, and caution that healthcare cost-profiling initiatives might even have the perverse effect of deterring them from seeking these providers.1 Cost measures, they argue, must be tied to quality information in order to neutralize the typical association of high costs with higher quality.1

Provider-Driven Approach

There are healthcare price transparency initiatives that address the supply side of the healthcare cost equation. These initiatives seek to educate physicians about the ways in which their clinical decisions drive cost and affect what patients pay for care. Some believe that this approach has the potential to make a much bigger dent in cost containment than the empowered-consumerism approach.

“Ninety percent of healthcare cost comes from a physician’s pen, but a lot of that spending doesn’t help patients get better,” says Neel Shah, MD, a Harvard-affiliated OBGYN and executive director of Costs of Care (www.costsofcare.org), a nonprofit aimed at empowering both patients and their caregivers to deflate medical bills. The challenge, he adds, is making physicians aware of how their decisions can inflate costs unnecessarily, and giving them the training and tools they need to take appropriate action.

“Just as the patient-safety movement helped caregivers think about how to prevent unintended harm, a new movement is needed to educate doctors, nurses, and other caregivers about the cost and value of their decisions, so they can avoid waste and protect patients from unintended financial harms as well,” Dr. Shah says.

Costs of Care recently launched its Teaching Value Project, which employs Web-based video education modules to help medical students and residents learn to optimize both quality and cost in clinical decision-making.

“We’re also developing an iPhone app to put cost and quality information at physicians’ fingertips at the critical moment when medical decisions are made,” Dr. Shah adds. “Just being able to see the price variation—an ultrasound versus a CT scan, a generic versus a brand-name medication, or the cost of a marginally valuable test—can help drive physician ordering behavior.”

Hospitalist Impacts

Robert A. Bessler, MD, CEO of Tacoma, Wash.-based hospitalist management firm Sound Physicians, says his hospitalists spend about $2 million a year “with their pen or computerized physician order entry.” A quarter of the cost is pharmacy-related, and the “majority of the rest is from bed-days.”

“The most expensive thing we do is make the decision to admit,” Dr. Bessler notes. “With hospitals switching from revenue centers to cost centers in a population health/ACO [accountable-care organization] environment, an increasingly important part of the hospitalist’s job will be asking

questions, such as, ‘Could this patient go to a nursing home tonight from the ER?’ and ‘Can my colleague in the post-acute environment take care of this patient, with the same effective outcome, if we provide more intense services in the nursing home, going forward?’”

Because most diagnostic testing is done on the front end of an inpatient’s stay, the hospitalist’s main contribution to cost control is to get that diagnosis right and use consults to answer specific questions, Dr. Bessler explains. “There is a direct correlation between the number of consults and the volume of procedures which lead to higher inpatient costs,” he adds.

As hospitals convert to value-based care models, and pressure increases on hospitalists to ramp up their analysis and sharing of cost data and resource utilization, not all physicians will find that conversion easy.

—Neel Shah, MD, executive director, Costs of Care

“We are trained to take good care of our patients, not to be financial stewards of the healthcare system,” says SHM Public Policy Committee member Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM. “Now, physicians are being asked to do both—to watch our resource use without looking like we’re selling out to payors. You’re putting physicians in a difficult position. Will they say to patients, ‘You can’t have this service’? When does being pragmatic stewards of resources become rationing?” he cautions.

Dr. Shah concedes that there is a perceived tension between “what’s best” for my patient and “what’s best” for society. “We, as a profession, haven’t given serious attention to how to navigate those tensions,” he says.

Dr. Flansbaum, a hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, says it’s time to start down the transparency road.

“Otherwise, we will have a centralized body making these decisions for us,” he says.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

Reference

As efforts intensify to rein in the soaring cost of healthcare, greater attention is being paid to the cost-control potential of price transparency. Initially envisioned as a consumer-driven dynamic, price transparency beckons physicians to consider much more seriously the cost impacts of their diagnostic and treatment decisions.

Consumer-Driven Approach

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regards price transparency as an important weapon in its armamentarium of “value-driven” approaches to drive down the cost of healthcare. By unleashing the energy of the savvy shopper and empowering consumers with the ability to compare the price and quality of healthcare services, they can make informed choices of their doctors and hospitals. In turn, HHS hopes to motivate the entire system to provide better care for less money.

That “empowered consumerism” principle is the guiding impetus for the Affordable Care Act’s state-regulated health insurance exchange apparatus, which, beginning in 2014, will present a side-by-side comparison of health plan choices, premium costs, and out-of-pocket copays in a way that is designed to help consumers shop for better-value health plans.

Some health plans are using price transparency to nudge consumers to choose lower-cost healthcare service options. Anthem BlueCross BlueShield, for example, has launched the Compass SmartShopper program (www.compasssmartshopper.com), which gives members in New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Indiana $50 to $200 if they get a diagnostic test or surgical procedure at a less expensive facility. Anthem notes that the cost for the same service can vary greatly. For example, hernia repairs range in price from $4,026 to $7,498, and colonoscopies range from $1,450 to $2,973.

New price transparency tools also are available (HealthCareBlueBook.com and FairHealthConsumer.org, for example) to help consumers who face high deductibles or out-of-pocket costs to find “fair prices” for surgeries, hospital stays, doctor visits, and medical tests—and shop accordingly.

Despite these developments, however, there is limited evidence that the “empowered consumerism” approach to price transparency will spur consumers to choose lower-cost providers. Some experts note that many consumers equate higher-cost providers with higher quality, and caution that healthcare cost-profiling initiatives might even have the perverse effect of deterring them from seeking these providers.1 Cost measures, they argue, must be tied to quality information in order to neutralize the typical association of high costs with higher quality.1

Provider-Driven Approach

There are healthcare price transparency initiatives that address the supply side of the healthcare cost equation. These initiatives seek to educate physicians about the ways in which their clinical decisions drive cost and affect what patients pay for care. Some believe that this approach has the potential to make a much bigger dent in cost containment than the empowered-consumerism approach.

“Ninety percent of healthcare cost comes from a physician’s pen, but a lot of that spending doesn’t help patients get better,” says Neel Shah, MD, a Harvard-affiliated OBGYN and executive director of Costs of Care (www.costsofcare.org), a nonprofit aimed at empowering both patients and their caregivers to deflate medical bills. The challenge, he adds, is making physicians aware of how their decisions can inflate costs unnecessarily, and giving them the training and tools they need to take appropriate action.

“Just as the patient-safety movement helped caregivers think about how to prevent unintended harm, a new movement is needed to educate doctors, nurses, and other caregivers about the cost and value of their decisions, so they can avoid waste and protect patients from unintended financial harms as well,” Dr. Shah says.

Costs of Care recently launched its Teaching Value Project, which employs Web-based video education modules to help medical students and residents learn to optimize both quality and cost in clinical decision-making.

“We’re also developing an iPhone app to put cost and quality information at physicians’ fingertips at the critical moment when medical decisions are made,” Dr. Shah adds. “Just being able to see the price variation—an ultrasound versus a CT scan, a generic versus a brand-name medication, or the cost of a marginally valuable test—can help drive physician ordering behavior.”

Hospitalist Impacts

Robert A. Bessler, MD, CEO of Tacoma, Wash.-based hospitalist management firm Sound Physicians, says his hospitalists spend about $2 million a year “with their pen or computerized physician order entry.” A quarter of the cost is pharmacy-related, and the “majority of the rest is from bed-days.”

“The most expensive thing we do is make the decision to admit,” Dr. Bessler notes. “With hospitals switching from revenue centers to cost centers in a population health/ACO [accountable-care organization] environment, an increasingly important part of the hospitalist’s job will be asking

questions, such as, ‘Could this patient go to a nursing home tonight from the ER?’ and ‘Can my colleague in the post-acute environment take care of this patient, with the same effective outcome, if we provide more intense services in the nursing home, going forward?’”

Because most diagnostic testing is done on the front end of an inpatient’s stay, the hospitalist’s main contribution to cost control is to get that diagnosis right and use consults to answer specific questions, Dr. Bessler explains. “There is a direct correlation between the number of consults and the volume of procedures which lead to higher inpatient costs,” he adds.

As hospitals convert to value-based care models, and pressure increases on hospitalists to ramp up their analysis and sharing of cost data and resource utilization, not all physicians will find that conversion easy.

—Neel Shah, MD, executive director, Costs of Care

“We are trained to take good care of our patients, not to be financial stewards of the healthcare system,” says SHM Public Policy Committee member Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM. “Now, physicians are being asked to do both—to watch our resource use without looking like we’re selling out to payors. You’re putting physicians in a difficult position. Will they say to patients, ‘You can’t have this service’? When does being pragmatic stewards of resources become rationing?” he cautions.

Dr. Shah concedes that there is a perceived tension between “what’s best” for my patient and “what’s best” for society. “We, as a profession, haven’t given serious attention to how to navigate those tensions,” he says.

Dr. Flansbaum, a hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, says it’s time to start down the transparency road.

“Otherwise, we will have a centralized body making these decisions for us,” he says.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

Reference

As efforts intensify to rein in the soaring cost of healthcare, greater attention is being paid to the cost-control potential of price transparency. Initially envisioned as a consumer-driven dynamic, price transparency beckons physicians to consider much more seriously the cost impacts of their diagnostic and treatment decisions.

Consumer-Driven Approach

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regards price transparency as an important weapon in its armamentarium of “value-driven” approaches to drive down the cost of healthcare. By unleashing the energy of the savvy shopper and empowering consumers with the ability to compare the price and quality of healthcare services, they can make informed choices of their doctors and hospitals. In turn, HHS hopes to motivate the entire system to provide better care for less money.

That “empowered consumerism” principle is the guiding impetus for the Affordable Care Act’s state-regulated health insurance exchange apparatus, which, beginning in 2014, will present a side-by-side comparison of health plan choices, premium costs, and out-of-pocket copays in a way that is designed to help consumers shop for better-value health plans.

Some health plans are using price transparency to nudge consumers to choose lower-cost healthcare service options. Anthem BlueCross BlueShield, for example, has launched the Compass SmartShopper program (www.compasssmartshopper.com), which gives members in New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Indiana $50 to $200 if they get a diagnostic test or surgical procedure at a less expensive facility. Anthem notes that the cost for the same service can vary greatly. For example, hernia repairs range in price from $4,026 to $7,498, and colonoscopies range from $1,450 to $2,973.

New price transparency tools also are available (HealthCareBlueBook.com and FairHealthConsumer.org, for example) to help consumers who face high deductibles or out-of-pocket costs to find “fair prices” for surgeries, hospital stays, doctor visits, and medical tests—and shop accordingly.