User login

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

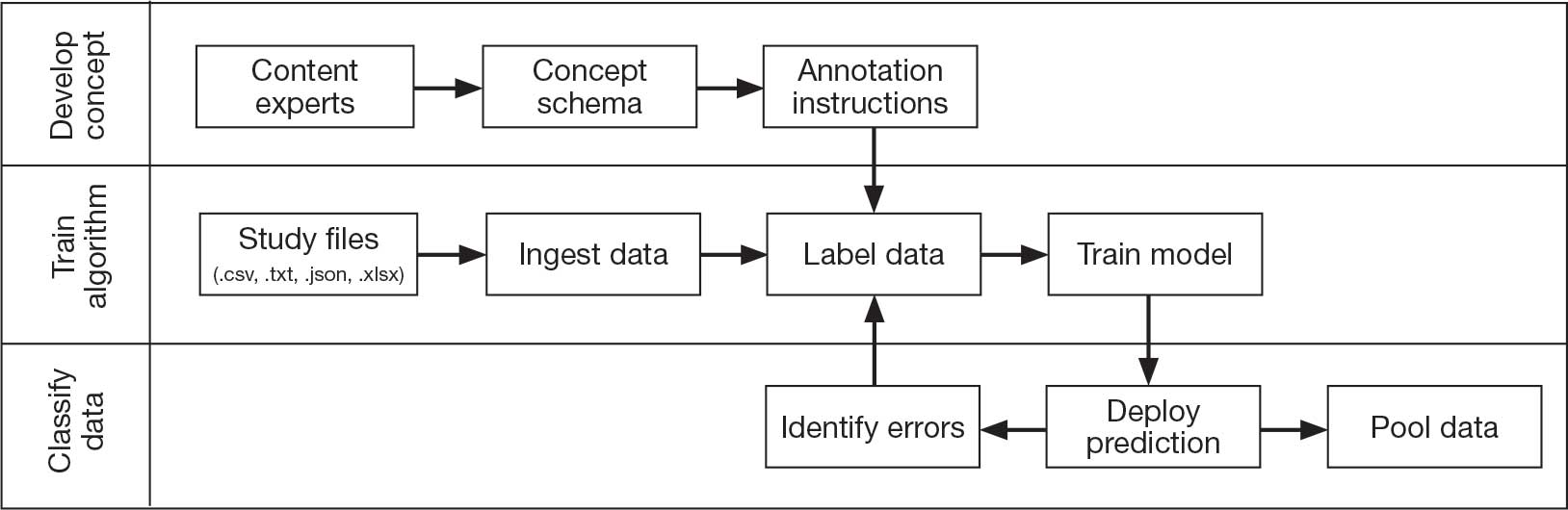

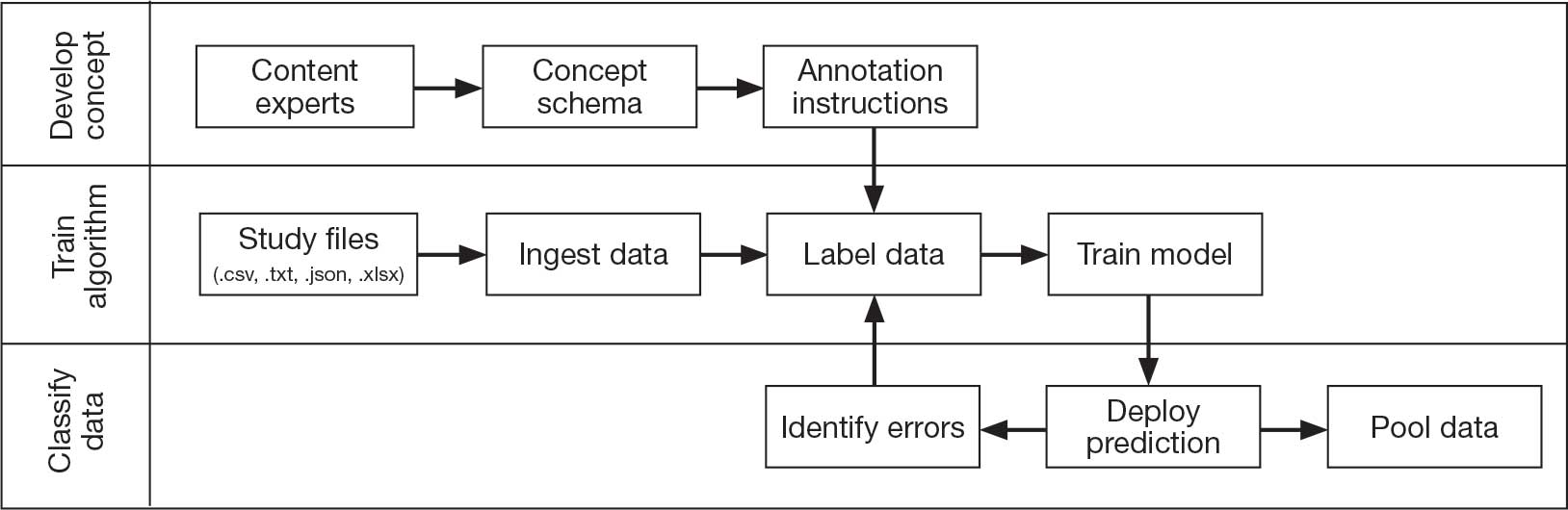

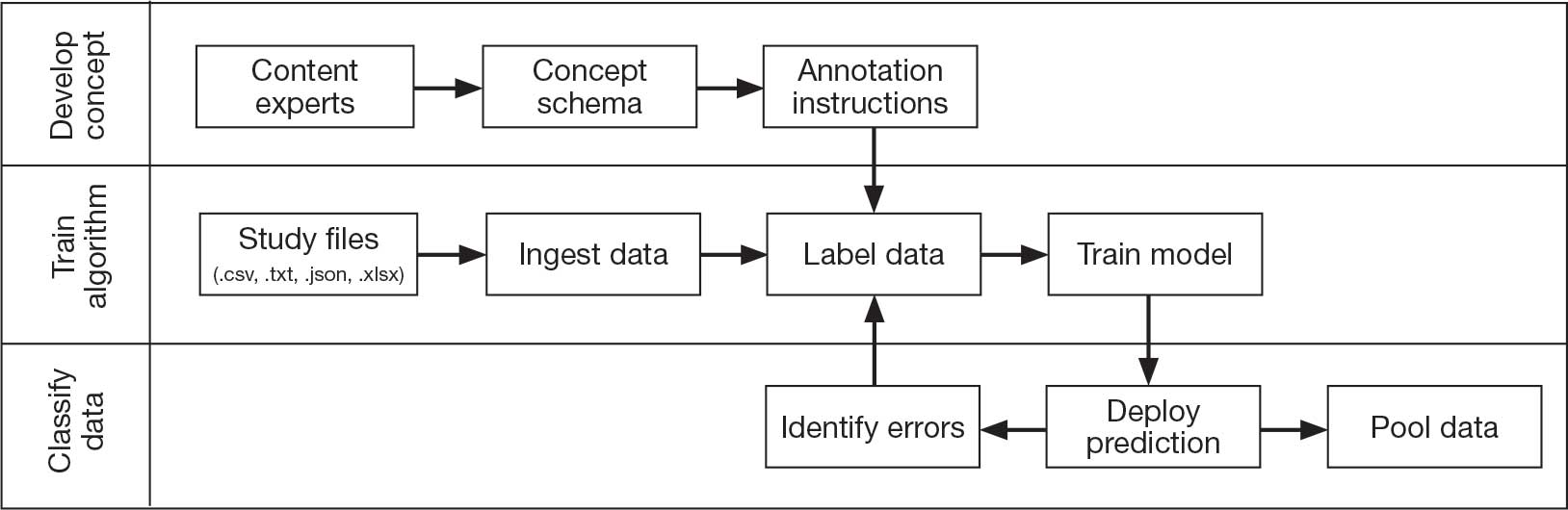

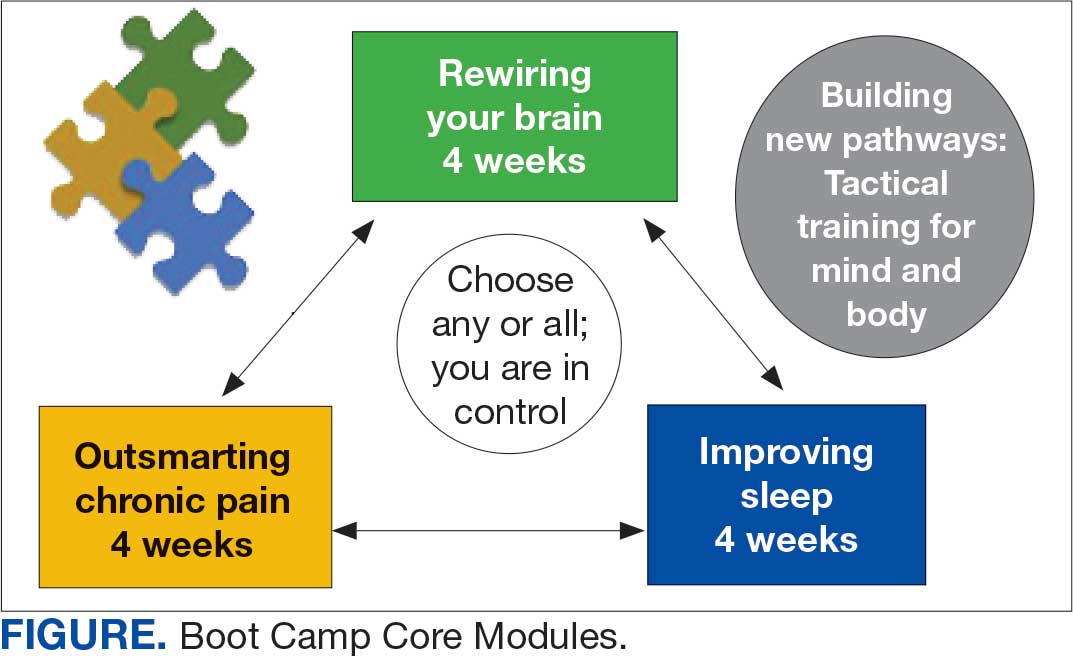

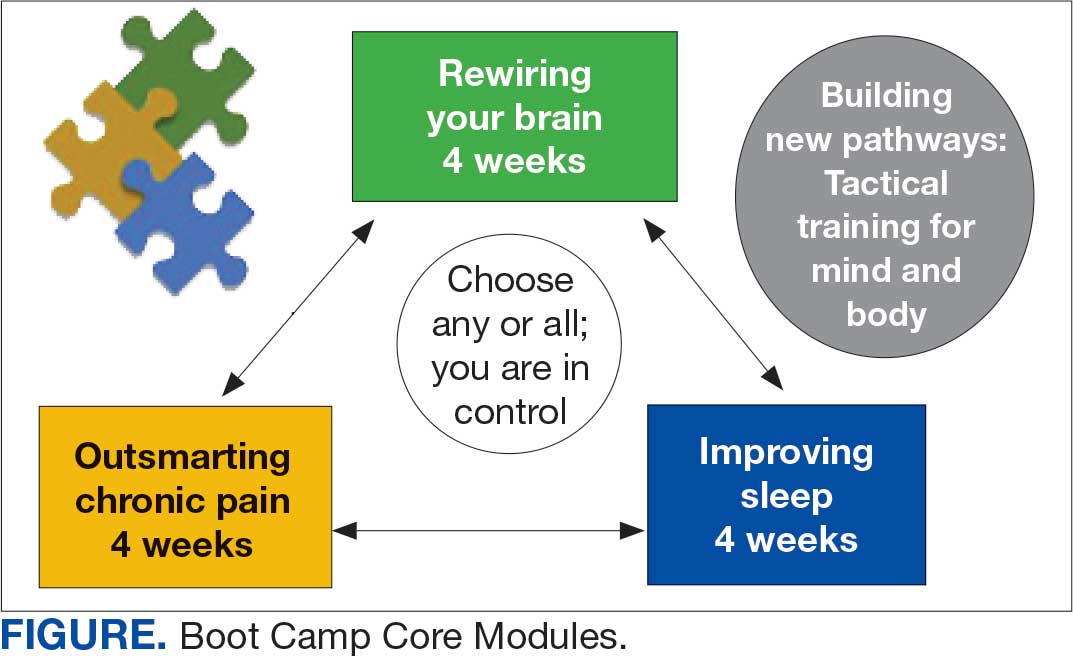

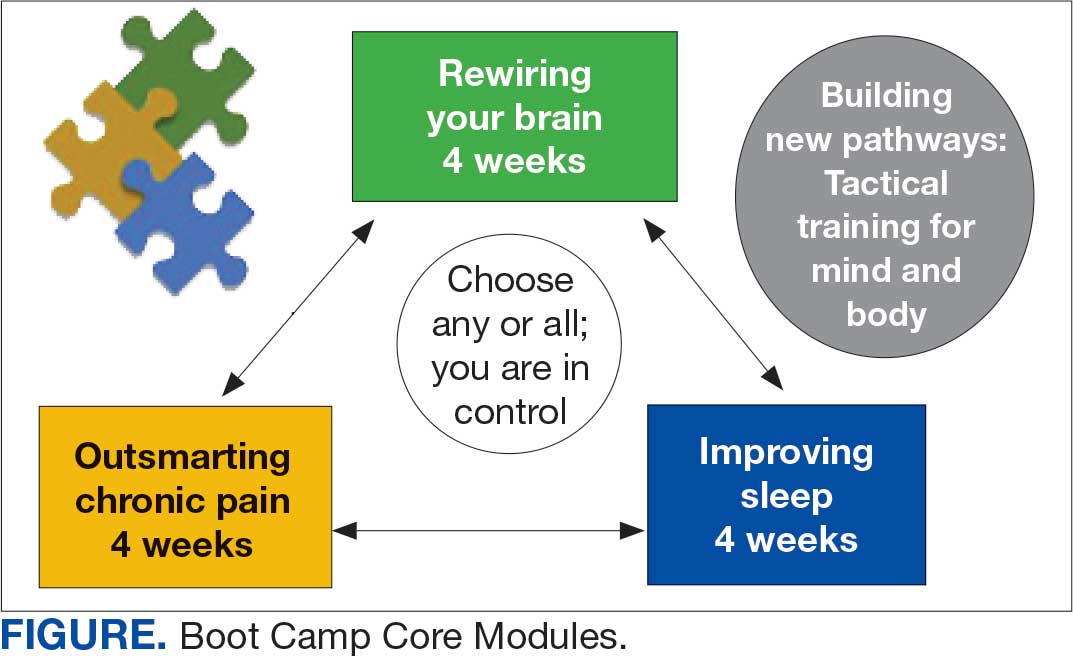

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

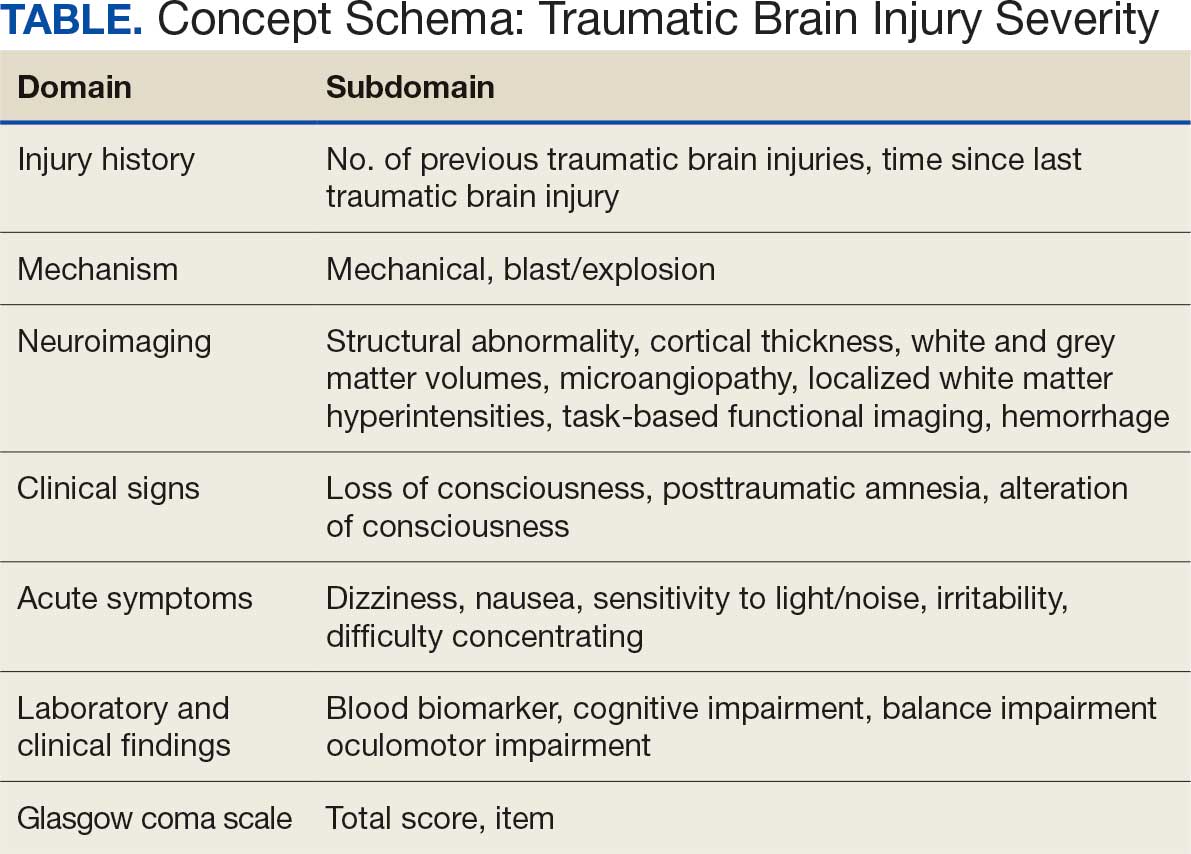

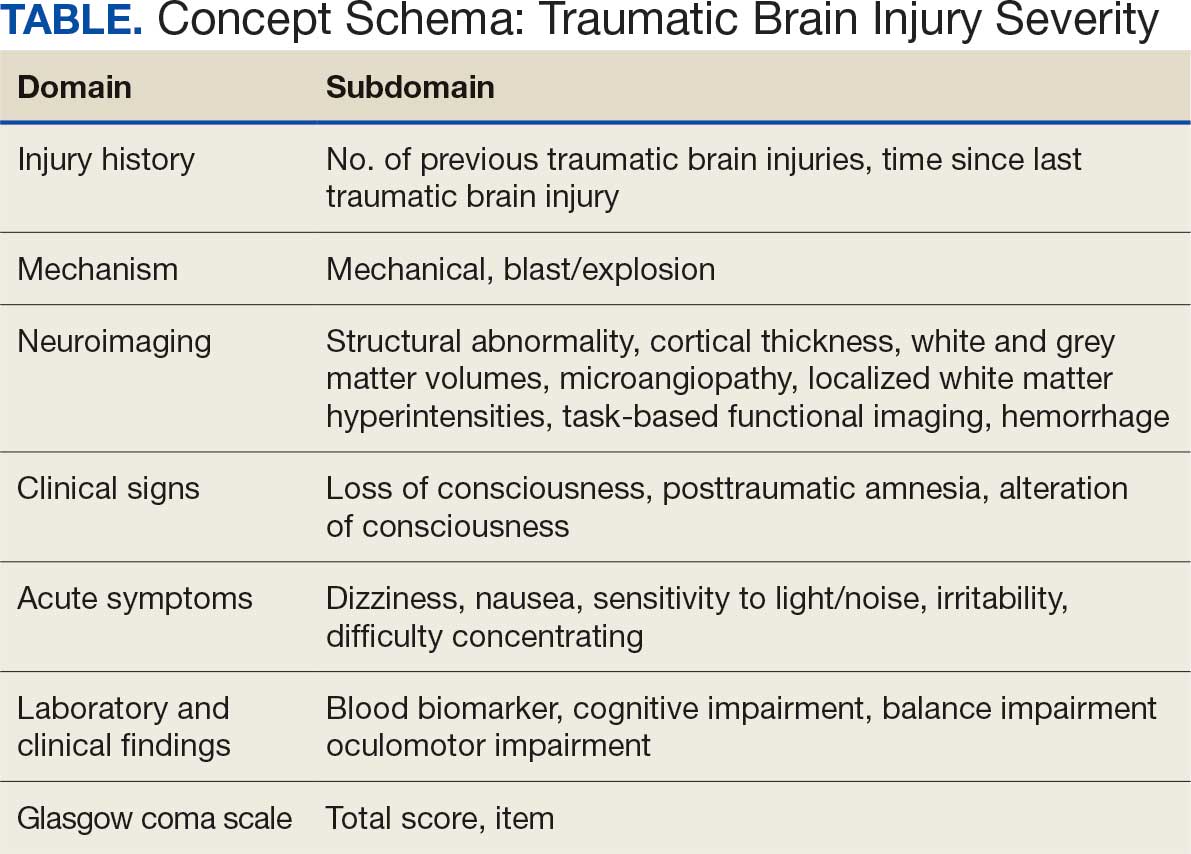

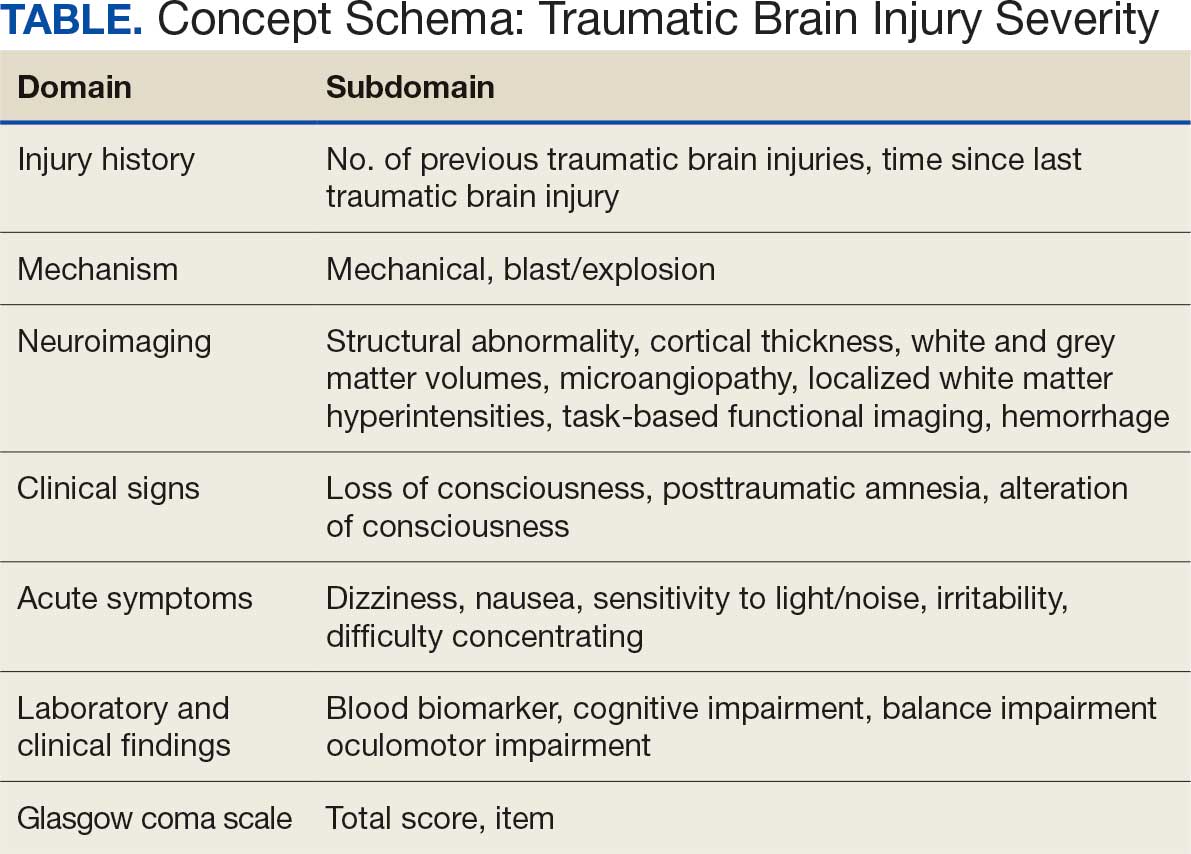

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

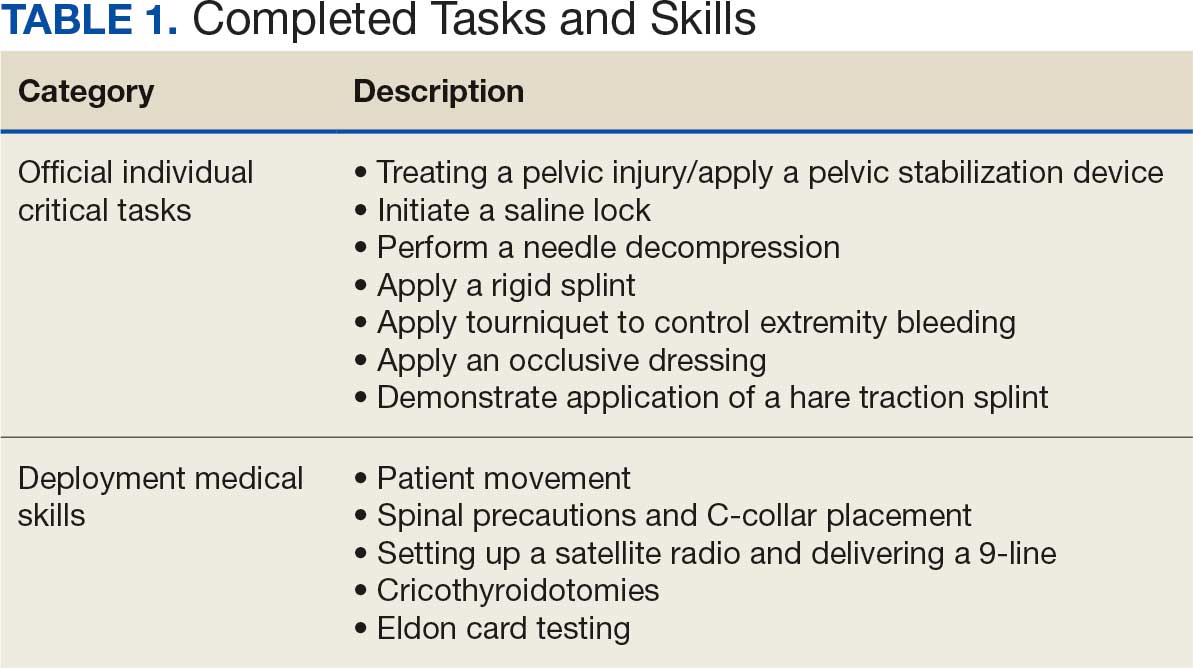

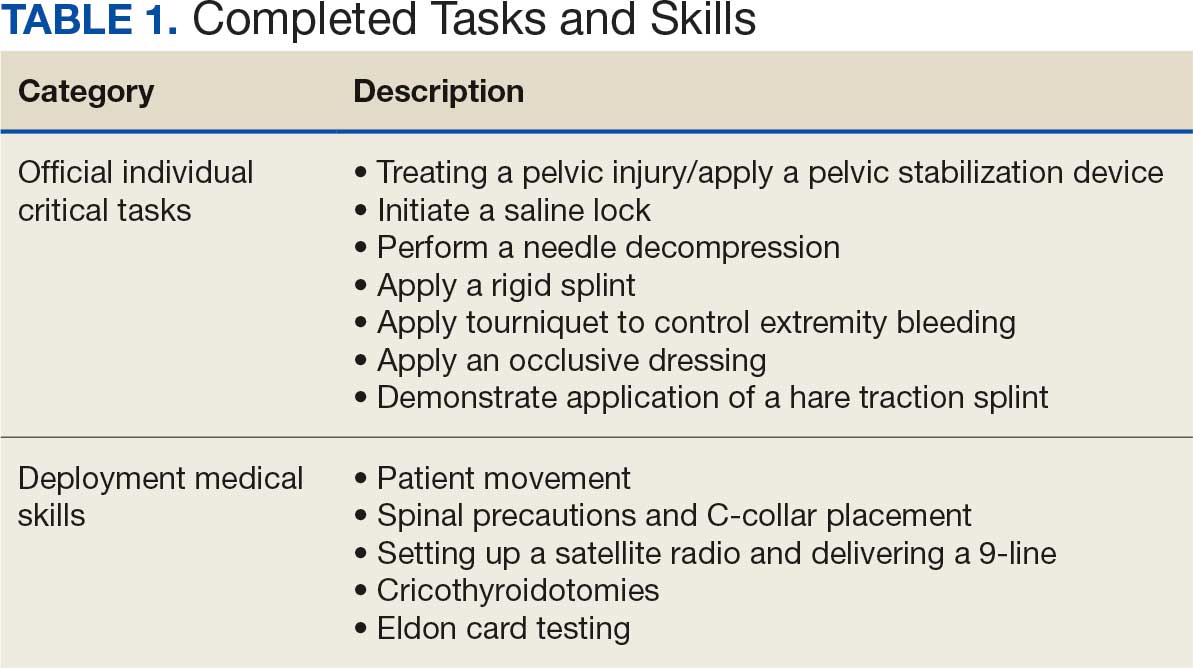

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Implementation of Harm Reduction Syringe Services Programs at 2 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers

Implementation of Harm Reduction Syringe Services Programs at 2 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers

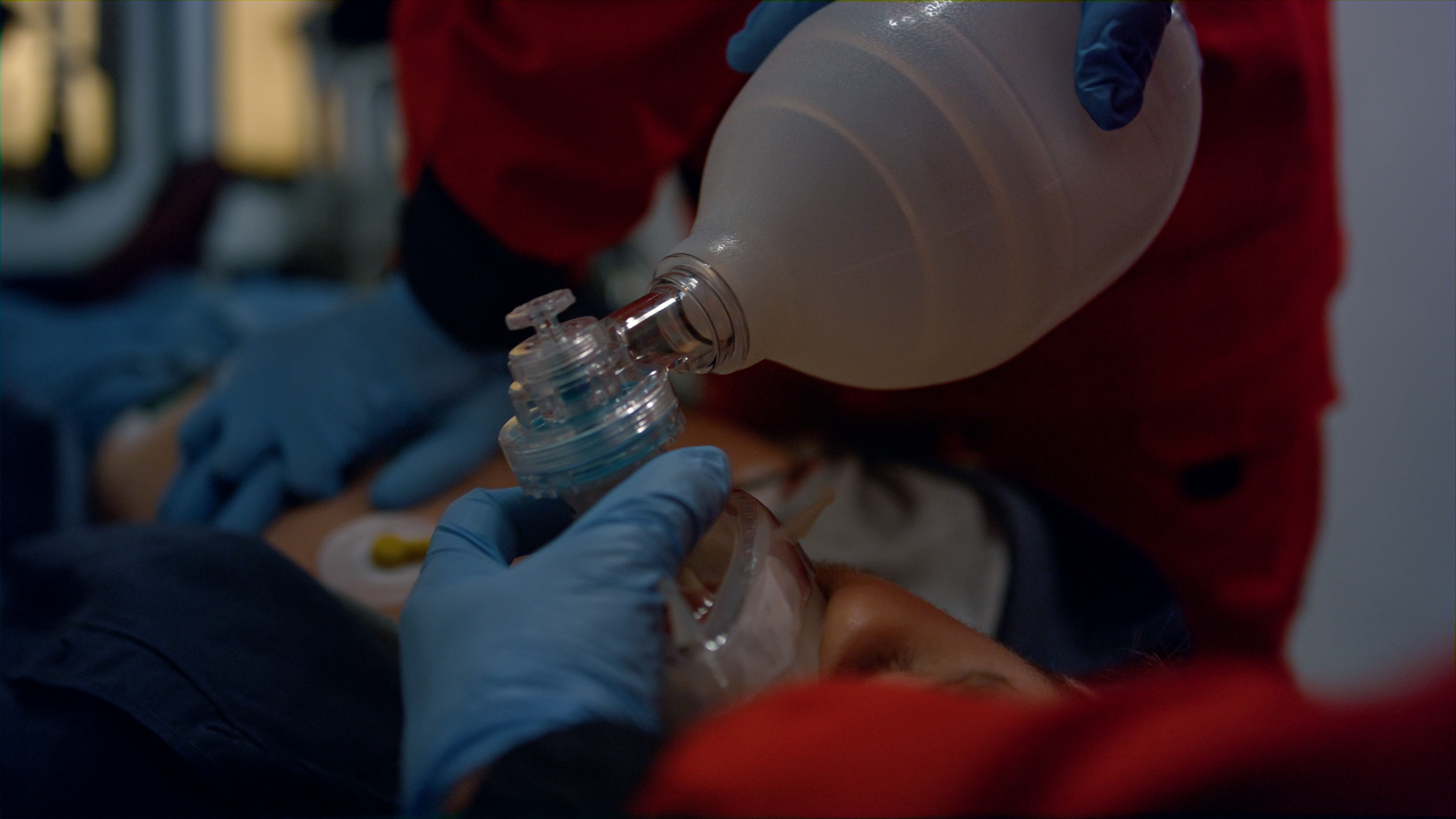

A syringe services program (SSP) is a harm reduction strategy designed to improve the quality of care provided to people who use drugs (PWUD). SSPs not only provide sterile syringes but establish a connection to medical services and resources for the safe disposal of syringes. By engaging with an SSP, patients may receive naloxone, condoms, fentanyl test strips, opioid use disorder medications, vaccinations, or testing for infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Patients may also be connected to housing or social work services.

SSPs do not lead to increased drug use,1 increased improperly disposed supplies needed for drug use in the community, or increased crime.2,3 New users of SSPs are 5 times more likely to enter treatment for drug use than those who do not use SSPs.4-8 Further, SSPs have been found to reduce HIV and HCV transmission and are cost-effective in HIV prevention.9-11

Syringe Services Program

SSPs were implemented at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Alaska VA Healthcare System (AVAHCS) and VA Southern Oregon Healthcare System (VASOHCS). AVAHCS provides outpatient care across Alaska, with sites in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Homer, Juneau, Wasilla, and Soldotna. VASOHCS provides outpatient care to Southern Oregon and Northern California, with sites in White City, Grants Pass, and Klamath Falls, Oregon. Both are part of Veterans Integrated Service Network 20

Workgroups at AVAHCS and VASOHCS developed SSPs to reduce risks associated with drug use, promote positive outcomes for PWUD, and increase availability of harm reduction resources. During the July 2023 to June 2024 pharmacy residency cycle, an ambulatory care pharmacy resident from the Veterans Integrated Services Network 20 Clinical Resource Hub—a regional resource for clinical services—joined the workgroups. The workgroups established a goal that SSP resources would be made available to enrolled patients without any exclusions, prioritizing health equity.

SSP implementation needed buy-in from AVAHCS and VASOHCS leadership and key stakeholders who could participate in the workgroups. Following AVAHCS and VASOHCS leadership approval, each facility workgroup drafted standard operating procedures (SOPs). Both facilities planned to implement the program using prepackaged kits (sterile syringes, alcohol pads, cotton swabs, a sharps container, and an educational brochure on safe injection practices) supplied by the VA National Harm Reduction Program.

Each SSP offered patients direct links to additional care options at the time of kit distribution, including information regarding medications/supplies (ie, hepatitis A/B vaccines, HIV preexposure prophylaxis, substance use disorder pharmacotherapy, naloxone, and condoms), laboratory tests for infectious and sexually transmitted diseases, and referrals to substance use disorder treatment, social work, suicide prevention, mental health, and primary care.

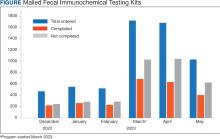

The goal was to implement both SSPs during the July 2023 to June 2024 residency year. Other goals included tracking the quantity of supplies distributed, the number of patients reached, the impact of clinician education on the distribution of supplies, and comparing the implementation of the SSPs in the electronic health record (EHR) systems.

Alaska VA Healthcare System

An SOP was approved on December 20, 2023, and national supply kits were stocked in collaboration with the logistics department at the Anchorage AVAHCS campus. Social and behavioral health teams, primary care social workers, primary care clinicians, and nursing staff received training on the resources available through the SSP. A local adaptation of a template was created in the Computerized Patient Records System (CPRS) EHR. The template facilitates SSP kit distribution and patient screening for additional resources. Patients can engage with the SSP through any trained staff member. The staff member then completes the template and helps to distribute the SSP kit, in collaboration with the logistics department. The SSP does not operate in a dedicated physical space. The behavioral health team is most actively engaged in the SSP. The goal of SSP is to have resources available anywhere a patient requests services, including primary care and specialty clinics and to empower staff to meet patients’ needs. One patient has utilized the SSP as of June 2025.

Southern Oregon Healthcare System

Kits were ordered and stocked as pharmacy items in preparation for dispensing while awaiting medical center policy approval. Education began with the primary care mental health integration team. After initial education, an interdisciplinary presentation was given to VASOHCS clinicians to increase knowledge of the SSP. To enable documentation of SSP engagement, a local template was developed in the Cerner EHR to be shared among care team members at the facility. Similar to AVAHCS, the SSP does not have a physical space. All trained facility staff may engage in the SSP and distribute SSP kits. The workgroup that implemented this program remains available to support staff. Five patients have accessed the SSP since November 2024 and 7 SSP kits have been distributed as of June 2025.

Discussion

The SSP workgroups sought to expand the program through additional education. A number of factors should be considered when implementing an SSP. Across facilities, program implementation can be time-consuming and the timeline for administrative processes may be long. The workgroups met weekly or monthly depending on the status of the program and the administrative processes. Materials developed included SOP and MCP documents, a 1-page educational handout on SSP offerings, and a PowerPoint presentation for initial clinician education. Involving a pharmacy resident supported professional development and accelerated implementation timelines.

The facilities differed in implementation. AVAHCS collaborated with the logistics department to distribute kits, while VASOHCS worked with the Pharmacy service. A benefit of collaborating with logistics is that patients can receive a kit at the point of contact with the health care system, receiving it directly from the clinic the patient is visiting while eliminating the need to make an additional stop at the pharmacy. Conversely, partnering with the Pharmacy service allowed supply kits to be distributed by mail, enabling patients direct access to kits without having to present in-person. This is particularly valuable considering the large geographical area and remote care services available at VASOHCS.

Implementation varied significantly because AVAHCS operated on CPRS while VASOHCS used Cerner, a newer EHR. AVAHCS adapted a national template produced for CPRS sites, while VASOHCS had to prepare a local template (auto-text) for SSP documentation. Future plans at AVAHCS may include adding fentanyl test strips as an orderable item in the EHR given that AVAHCS has a local instance of CPRS; however, VASOHCS cannot order fentanyl test strips through the Pharmacy service due to legal restrictions. While Oregon permits fentanyl test strip use, the Cerner instance used by VA is a national program, and therefore the addition of fentanyl test strips as an orderable item in the EHR would carry national implications, including for VA health care systems in states where fentanyl test strip legality is variable. Despite the challenges, efforts to include fentanyl test strips in both SSPs are ongoing.

No significant EHR changes were needed to make the national supply kits available in the Cerner EHR through the VASOHCS Pharmacy service. To have national supply kits available through the AVAHCS Pharmacy service, the EHR would need to be manipulated by adding a local drug file in CPRS. Differences between the EHRs often facilitated the need for adaptation from existing models of SSPs within VA, which were all based in CPRS.

Conclusions

The implementation of SSPs at AVAHCS and VASOHCS enable clinicians to provide quality harm reduction services to PWUD. Despite variations in EHR systems, AVAHCS and VASOHCS implemented SSP within 1 year. Tracking of program engagement via the number of patients interacting with the program and the number of SSP kits distributed will continue. SSP implementation in states where it is permitted may help provide optimal patient care for PWUD.

- Hagan H, McGough JP, Thiede H, Hopkins S, Duchin J, Alexander ER. Reduced injection frequency and increased entry and retention in drug treatment associated with needle-exchange participation in Seattle drug injectors. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19(3):247-252. doi:10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00104-5

- Marx MA, Crape B, Brookmeyer RS, et al. Trends in crime and the introduction of a needle exchange program. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1933-1936. doi:10.2105/ajph.90.12.1933

- Galea S, Ahern J, Fuller C, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D. Needle exchange programs and experience of violence in an inner city neighborhood. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(3):282-288. doi:10.1097/00042560-200111010-00014

- Des Jarlais DC, Nugent A, Solberg A, Feelemyer J, Mermin J, Holtzman D. Syringe service programs for persons who inject drugs in urban, suburban, and rural areas — United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(48):1337-1341. doi:10.15585/ mmwr.mm6448a3

- Tookes HE, Kral AH, Wenger LD, et al. A comparison of syringe disposal practices among injection drug users in a city with versus a city without needle and syringe programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1-3):255-259. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.001

- Klein SJ, Candelas AR, Cooper JG, et al. Increasing safe syringe collection sites in New York State. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(4):433-440. doi:10.1177/003335490812300404

- de Montigny L, Vernez Moudon A, Leigh B, Kim SY. Assessing a drop box programme: a spatial analysis of discarded needles. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(3):208-214. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.07.003

- Bluthenthal RN, Anderson R, Flynn NM, Kral AH. Higher syringe coverage is associated with lower odds of HIV risk and does not increase unsafe syringe disposal among syringe exchange program clients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(2-3):214-222. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.035

- Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD012021. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012021.pub2

- Fernandes RM, Cary M, Duarte G, et al. Effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes in people who inject drugs — an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):309. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4210-2

- Bernard CL, Owens DK, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Brandeau ML. Estimation of the cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention portfolios for people who inject drugs in the United States: a model-based analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(5):e1002312. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002312

A syringe services program (SSP) is a harm reduction strategy designed to improve the quality of care provided to people who use drugs (PWUD). SSPs not only provide sterile syringes but establish a connection to medical services and resources for the safe disposal of syringes. By engaging with an SSP, patients may receive naloxone, condoms, fentanyl test strips, opioid use disorder medications, vaccinations, or testing for infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Patients may also be connected to housing or social work services.

SSPs do not lead to increased drug use,1 increased improperly disposed supplies needed for drug use in the community, or increased crime.2,3 New users of SSPs are 5 times more likely to enter treatment for drug use than those who do not use SSPs.4-8 Further, SSPs have been found to reduce HIV and HCV transmission and are cost-effective in HIV prevention.9-11

Syringe Services Program

SSPs were implemented at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Alaska VA Healthcare System (AVAHCS) and VA Southern Oregon Healthcare System (VASOHCS). AVAHCS provides outpatient care across Alaska, with sites in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Homer, Juneau, Wasilla, and Soldotna. VASOHCS provides outpatient care to Southern Oregon and Northern California, with sites in White City, Grants Pass, and Klamath Falls, Oregon. Both are part of Veterans Integrated Service Network 20

Workgroups at AVAHCS and VASOHCS developed SSPs to reduce risks associated with drug use, promote positive outcomes for PWUD, and increase availability of harm reduction resources. During the July 2023 to June 2024 pharmacy residency cycle, an ambulatory care pharmacy resident from the Veterans Integrated Services Network 20 Clinical Resource Hub—a regional resource for clinical services—joined the workgroups. The workgroups established a goal that SSP resources would be made available to enrolled patients without any exclusions, prioritizing health equity.

SSP implementation needed buy-in from AVAHCS and VASOHCS leadership and key stakeholders who could participate in the workgroups. Following AVAHCS and VASOHCS leadership approval, each facility workgroup drafted standard operating procedures (SOPs). Both facilities planned to implement the program using prepackaged kits (sterile syringes, alcohol pads, cotton swabs, a sharps container, and an educational brochure on safe injection practices) supplied by the VA National Harm Reduction Program.

Each SSP offered patients direct links to additional care options at the time of kit distribution, including information regarding medications/supplies (ie, hepatitis A/B vaccines, HIV preexposure prophylaxis, substance use disorder pharmacotherapy, naloxone, and condoms), laboratory tests for infectious and sexually transmitted diseases, and referrals to substance use disorder treatment, social work, suicide prevention, mental health, and primary care.

The goal was to implement both SSPs during the July 2023 to June 2024 residency year. Other goals included tracking the quantity of supplies distributed, the number of patients reached, the impact of clinician education on the distribution of supplies, and comparing the implementation of the SSPs in the electronic health record (EHR) systems.

Alaska VA Healthcare System

An SOP was approved on December 20, 2023, and national supply kits were stocked in collaboration with the logistics department at the Anchorage AVAHCS campus. Social and behavioral health teams, primary care social workers, primary care clinicians, and nursing staff received training on the resources available through the SSP. A local adaptation of a template was created in the Computerized Patient Records System (CPRS) EHR. The template facilitates SSP kit distribution and patient screening for additional resources. Patients can engage with the SSP through any trained staff member. The staff member then completes the template and helps to distribute the SSP kit, in collaboration with the logistics department. The SSP does not operate in a dedicated physical space. The behavioral health team is most actively engaged in the SSP. The goal of SSP is to have resources available anywhere a patient requests services, including primary care and specialty clinics and to empower staff to meet patients’ needs. One patient has utilized the SSP as of June 2025.

Southern Oregon Healthcare System

Kits were ordered and stocked as pharmacy items in preparation for dispensing while awaiting medical center policy approval. Education began with the primary care mental health integration team. After initial education, an interdisciplinary presentation was given to VASOHCS clinicians to increase knowledge of the SSP. To enable documentation of SSP engagement, a local template was developed in the Cerner EHR to be shared among care team members at the facility. Similar to AVAHCS, the SSP does not have a physical space. All trained facility staff may engage in the SSP and distribute SSP kits. The workgroup that implemented this program remains available to support staff. Five patients have accessed the SSP since November 2024 and 7 SSP kits have been distributed as of June 2025.

Discussion

The SSP workgroups sought to expand the program through additional education. A number of factors should be considered when implementing an SSP. Across facilities, program implementation can be time-consuming and the timeline for administrative processes may be long. The workgroups met weekly or monthly depending on the status of the program and the administrative processes. Materials developed included SOP and MCP documents, a 1-page educational handout on SSP offerings, and a PowerPoint presentation for initial clinician education. Involving a pharmacy resident supported professional development and accelerated implementation timelines.

The facilities differed in implementation. AVAHCS collaborated with the logistics department to distribute kits, while VASOHCS worked with the Pharmacy service. A benefit of collaborating with logistics is that patients can receive a kit at the point of contact with the health care system, receiving it directly from the clinic the patient is visiting while eliminating the need to make an additional stop at the pharmacy. Conversely, partnering with the Pharmacy service allowed supply kits to be distributed by mail, enabling patients direct access to kits without having to present in-person. This is particularly valuable considering the large geographical area and remote care services available at VASOHCS.

Implementation varied significantly because AVAHCS operated on CPRS while VASOHCS used Cerner, a newer EHR. AVAHCS adapted a national template produced for CPRS sites, while VASOHCS had to prepare a local template (auto-text) for SSP documentation. Future plans at AVAHCS may include adding fentanyl test strips as an orderable item in the EHR given that AVAHCS has a local instance of CPRS; however, VASOHCS cannot order fentanyl test strips through the Pharmacy service due to legal restrictions. While Oregon permits fentanyl test strip use, the Cerner instance used by VA is a national program, and therefore the addition of fentanyl test strips as an orderable item in the EHR would carry national implications, including for VA health care systems in states where fentanyl test strip legality is variable. Despite the challenges, efforts to include fentanyl test strips in both SSPs are ongoing.

No significant EHR changes were needed to make the national supply kits available in the Cerner EHR through the VASOHCS Pharmacy service. To have national supply kits available through the AVAHCS Pharmacy service, the EHR would need to be manipulated by adding a local drug file in CPRS. Differences between the EHRs often facilitated the need for adaptation from existing models of SSPs within VA, which were all based in CPRS.

Conclusions

The implementation of SSPs at AVAHCS and VASOHCS enable clinicians to provide quality harm reduction services to PWUD. Despite variations in EHR systems, AVAHCS and VASOHCS implemented SSP within 1 year. Tracking of program engagement via the number of patients interacting with the program and the number of SSP kits distributed will continue. SSP implementation in states where it is permitted may help provide optimal patient care for PWUD.

A syringe services program (SSP) is a harm reduction strategy designed to improve the quality of care provided to people who use drugs (PWUD). SSPs not only provide sterile syringes but establish a connection to medical services and resources for the safe disposal of syringes. By engaging with an SSP, patients may receive naloxone, condoms, fentanyl test strips, opioid use disorder medications, vaccinations, or testing for infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Patients may also be connected to housing or social work services.

SSPs do not lead to increased drug use,1 increased improperly disposed supplies needed for drug use in the community, or increased crime.2,3 New users of SSPs are 5 times more likely to enter treatment for drug use than those who do not use SSPs.4-8 Further, SSPs have been found to reduce HIV and HCV transmission and are cost-effective in HIV prevention.9-11

Syringe Services Program

SSPs were implemented at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Alaska VA Healthcare System (AVAHCS) and VA Southern Oregon Healthcare System (VASOHCS). AVAHCS provides outpatient care across Alaska, with sites in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Homer, Juneau, Wasilla, and Soldotna. VASOHCS provides outpatient care to Southern Oregon and Northern California, with sites in White City, Grants Pass, and Klamath Falls, Oregon. Both are part of Veterans Integrated Service Network 20

Workgroups at AVAHCS and VASOHCS developed SSPs to reduce risks associated with drug use, promote positive outcomes for PWUD, and increase availability of harm reduction resources. During the July 2023 to June 2024 pharmacy residency cycle, an ambulatory care pharmacy resident from the Veterans Integrated Services Network 20 Clinical Resource Hub—a regional resource for clinical services—joined the workgroups. The workgroups established a goal that SSP resources would be made available to enrolled patients without any exclusions, prioritizing health equity.