User login

The Hospitalist only

Giving hospitalists a larger clinical footprint

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader blog

“We are playing the same sport, but a different game,” the wise, thoughtful emergency medicine attending physician once told me. “I am playing speed chess – I need to make a move quickly, or I lose – no matter what. My moves have to be right, but they don’t always necessarily need to be the optimal one. I am not always thinking five moves ahead. You guys [in internal medicine] are playing master chess. You have more time, but that means you are trying to always think about the whole game and make the best move possible.”

The pendulum has swung quickly from, “problem #7, chronic anemia: stable but I am not sure it has been worked up before, so I ordered a smear, retic count, and iron panel,” to “problem #1, acute blood loss anemia: now stable after transfusion, seems safe for discharge and GI follow-up.” (NOTE: “Acute blood loss anemia” is a phrase I learned from our “clinical documentation integrity specialist” – I think it gets me “50 CDI points” or something.)

Our job is not merely to work shifts and stabilize patients – there already is a specialty for that, and it is not the one we chose.

Clearly the correct balance is somewhere between the two extremes of “working up everything” and “deferring (nearly) everything to the outpatient setting.”

There are many forces that are contributing to current hospitalist work styles. As the work continues to become more exhaustingly intense and the average number of patients seen by a hospitalist grows impossibly upward, the duration of on-service stints has shortened.

In most settings, long gone are the days of the month-long teaching attending rotation. By day 12, I feel worn and ragged. For “nonteaching” services, hospitalists seem to increasingly treat each day as a separate shift to be covered, oftentimes handing the service back-and-forth every few days, or a week at most. With this structure, who can possibly think about the “whole patient”? Whose patient is this anyways?

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- How Hospitalists See the Forgotten Victims of Gun Violence by Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, MHM

- Hospitals, Hospice and SNFs: The Big Deceit by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

- But He’s a Good Doctor by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader blog

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader blog

“We are playing the same sport, but a different game,” the wise, thoughtful emergency medicine attending physician once told me. “I am playing speed chess – I need to make a move quickly, or I lose – no matter what. My moves have to be right, but they don’t always necessarily need to be the optimal one. I am not always thinking five moves ahead. You guys [in internal medicine] are playing master chess. You have more time, but that means you are trying to always think about the whole game and make the best move possible.”

The pendulum has swung quickly from, “problem #7, chronic anemia: stable but I am not sure it has been worked up before, so I ordered a smear, retic count, and iron panel,” to “problem #1, acute blood loss anemia: now stable after transfusion, seems safe for discharge and GI follow-up.” (NOTE: “Acute blood loss anemia” is a phrase I learned from our “clinical documentation integrity specialist” – I think it gets me “50 CDI points” or something.)

Our job is not merely to work shifts and stabilize patients – there already is a specialty for that, and it is not the one we chose.

Clearly the correct balance is somewhere between the two extremes of “working up everything” and “deferring (nearly) everything to the outpatient setting.”

There are many forces that are contributing to current hospitalist work styles. As the work continues to become more exhaustingly intense and the average number of patients seen by a hospitalist grows impossibly upward, the duration of on-service stints has shortened.

In most settings, long gone are the days of the month-long teaching attending rotation. By day 12, I feel worn and ragged. For “nonteaching” services, hospitalists seem to increasingly treat each day as a separate shift to be covered, oftentimes handing the service back-and-forth every few days, or a week at most. With this structure, who can possibly think about the “whole patient”? Whose patient is this anyways?

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- How Hospitalists See the Forgotten Victims of Gun Violence by Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, MHM

- Hospitals, Hospice and SNFs: The Big Deceit by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

- But He’s a Good Doctor by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

“We are playing the same sport, but a different game,” the wise, thoughtful emergency medicine attending physician once told me. “I am playing speed chess – I need to make a move quickly, or I lose – no matter what. My moves have to be right, but they don’t always necessarily need to be the optimal one. I am not always thinking five moves ahead. You guys [in internal medicine] are playing master chess. You have more time, but that means you are trying to always think about the whole game and make the best move possible.”

The pendulum has swung quickly from, “problem #7, chronic anemia: stable but I am not sure it has been worked up before, so I ordered a smear, retic count, and iron panel,” to “problem #1, acute blood loss anemia: now stable after transfusion, seems safe for discharge and GI follow-up.” (NOTE: “Acute blood loss anemia” is a phrase I learned from our “clinical documentation integrity specialist” – I think it gets me “50 CDI points” or something.)

Our job is not merely to work shifts and stabilize patients – there already is a specialty for that, and it is not the one we chose.

Clearly the correct balance is somewhere between the two extremes of “working up everything” and “deferring (nearly) everything to the outpatient setting.”

There are many forces that are contributing to current hospitalist work styles. As the work continues to become more exhaustingly intense and the average number of patients seen by a hospitalist grows impossibly upward, the duration of on-service stints has shortened.

In most settings, long gone are the days of the month-long teaching attending rotation. By day 12, I feel worn and ragged. For “nonteaching” services, hospitalists seem to increasingly treat each day as a separate shift to be covered, oftentimes handing the service back-and-forth every few days, or a week at most. With this structure, who can possibly think about the “whole patient”? Whose patient is this anyways?

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- How Hospitalists See the Forgotten Victims of Gun Violence by Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, MHM

- Hospitals, Hospice and SNFs: The Big Deceit by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

- But He’s a Good Doctor by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

The work schedule that prevents burnout

The schedule is easier to change than the work itself

Burnout is influenced by a seemingly infinite combination of variables. An optimal schedule alone isn’t the key to preventing it, but maybe a good schedule can reduce your risk you’ll suffer from it.

Smart people who have spent years as hospitalists, working multiple different schedules, have formed a variety of conclusions about which work schedules best reduce the risk of burnout. There’s no meaningful research to settle the question, so everyone will have to reach their own conclusions, as I’ve done here.

Scheduling flexibility: Often overlooked?

Someone who typically works the same number of consecutive day shifts, each of which is the same duration, might suffer from the monotony and inexorable predictability. Schedules that vary the number of consecutive day shifts, the intensity or length of shifts, and the number of consecutive days off might result in lower rates of burnout. This is especially likely to be the case if each provider has some flexibility to control how her schedule varies over time.

Personal time goes on the calendar first

Those who have a regularly repeating work schedule tend to work hard arranging such important things as family vacations on days the schedule dictates. In other words, the first thing that goes on the personal calendar are the weeks of work; they’re “X-ed” out and personal events filled into the remaining days.

That’s fine for many personal activities, but it means the hospitalist might tend to set a pretty high bar for activities that are worth negotiating alterations to the usual schedule. For example, you might want to see U2 but decide to skip their concert in your town since it falls in the middle of your regularly scheduled week of work. Maybe that’s not a big deal (Isn’t U2 overplayed and out of date anyway?), but an accumulation of small sacrifices like this might increase resentment of work.

It’s possible to organize a hospitalist group schedule in which each provider’s personally requested days off, like the U2 concert, go on the work calendar first, and the clinical schedule is built around them. It can get pretty time consuming to manage, but might be a worthwhile investment to reduce burnout risk.

A paradox: Fewer shifts could increase burnout risk

I’m convinced many hospitalists make the mistake of seeking to maximize their number of days off with the idea that it will be good for happiness, career longevity, burnout, etc. While having more days off provides more time for nonwork activities and rest/recovery from work, it usually means the average workday is busier and more stressful to maintain expected levels of productivity. The net effect for some seems to be increased burnout.

Consider someone who has been working 182 hospitalist shifts and generating a total of 2,114 billed encounters annually (both are the most recent national medians available from surveys). This hospitalist successfully negotiates a reduction to 161 annual shifts. This would probably feel good to anyone at first, but keep in mind that it means the average number of daily encounters to maintain median annual productivity would increase 13% (from 11.6 to 13.1 in this example). That is, each day of work just got 13% busier.

I regularly encounter career hospitalists with more than 10 years of experience who say they still appreciate – or even are addicted to – having lots of days off. But the worked days often are so busy they don’t know how long they can keep doing it. It is possible some of them might be happier and less burned out if they work more shifts annually, and the average shift is meaningfully less busy.

The “right” number of shifts depends on a combination of personal and economic factors. Rather than focusing almost exclusively on the number of shifts worked annually, it may be better to think about the total amount of annual work measured in billed encounters, or wRVUs [work relative value units], and how it is titrated out on the calendar.

Other scheduling attributes and burnout

I think it’s really important to ensure the hospitalist group always has the target number of providers working each day. Many groups have experienced staffing deficits for so long that they’ve essentially given up on this goal, and staffing levels vary day to day. This means each provider has uncertainty regarding how often he will be scheduled on days with fewer than the targeted numbers of providers working.

All hospitalist groups should ensure their schedule has day-shift providers work a meaningful series of shifts consecutively to support good patient-provider continuity. I think “continuity is king” and influences efficiency, quality of care, and provider burnout. Of course, there is tension between working many consecutive day shifts and still having a reasonable lifestyle; you’ll have to make up your own mind about the sweet spot between these to competing needs.

Schedule and number of shifts are only part of the burnout picture. The nature of hospitalist work, including EHR frustrations and distressing conversations regarding observation status, etc., probably has more significant influence on burnout and job satisfaction than does the work schedule itself.

But there is still lots of value in thinking carefully about your group’s work schedule and making adjustments where needed. The schedule is a lot easier to change than the nature of the work itself.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Contact him at [email protected].

The schedule is easier to change than the work itself

The schedule is easier to change than the work itself

Burnout is influenced by a seemingly infinite combination of variables. An optimal schedule alone isn’t the key to preventing it, but maybe a good schedule can reduce your risk you’ll suffer from it.

Smart people who have spent years as hospitalists, working multiple different schedules, have formed a variety of conclusions about which work schedules best reduce the risk of burnout. There’s no meaningful research to settle the question, so everyone will have to reach their own conclusions, as I’ve done here.

Scheduling flexibility: Often overlooked?

Someone who typically works the same number of consecutive day shifts, each of which is the same duration, might suffer from the monotony and inexorable predictability. Schedules that vary the number of consecutive day shifts, the intensity or length of shifts, and the number of consecutive days off might result in lower rates of burnout. This is especially likely to be the case if each provider has some flexibility to control how her schedule varies over time.

Personal time goes on the calendar first

Those who have a regularly repeating work schedule tend to work hard arranging such important things as family vacations on days the schedule dictates. In other words, the first thing that goes on the personal calendar are the weeks of work; they’re “X-ed” out and personal events filled into the remaining days.

That’s fine for many personal activities, but it means the hospitalist might tend to set a pretty high bar for activities that are worth negotiating alterations to the usual schedule. For example, you might want to see U2 but decide to skip their concert in your town since it falls in the middle of your regularly scheduled week of work. Maybe that’s not a big deal (Isn’t U2 overplayed and out of date anyway?), but an accumulation of small sacrifices like this might increase resentment of work.

It’s possible to organize a hospitalist group schedule in which each provider’s personally requested days off, like the U2 concert, go on the work calendar first, and the clinical schedule is built around them. It can get pretty time consuming to manage, but might be a worthwhile investment to reduce burnout risk.

A paradox: Fewer shifts could increase burnout risk

I’m convinced many hospitalists make the mistake of seeking to maximize their number of days off with the idea that it will be good for happiness, career longevity, burnout, etc. While having more days off provides more time for nonwork activities and rest/recovery from work, it usually means the average workday is busier and more stressful to maintain expected levels of productivity. The net effect for some seems to be increased burnout.

Consider someone who has been working 182 hospitalist shifts and generating a total of 2,114 billed encounters annually (both are the most recent national medians available from surveys). This hospitalist successfully negotiates a reduction to 161 annual shifts. This would probably feel good to anyone at first, but keep in mind that it means the average number of daily encounters to maintain median annual productivity would increase 13% (from 11.6 to 13.1 in this example). That is, each day of work just got 13% busier.

I regularly encounter career hospitalists with more than 10 years of experience who say they still appreciate – or even are addicted to – having lots of days off. But the worked days often are so busy they don’t know how long they can keep doing it. It is possible some of them might be happier and less burned out if they work more shifts annually, and the average shift is meaningfully less busy.

The “right” number of shifts depends on a combination of personal and economic factors. Rather than focusing almost exclusively on the number of shifts worked annually, it may be better to think about the total amount of annual work measured in billed encounters, or wRVUs [work relative value units], and how it is titrated out on the calendar.

Other scheduling attributes and burnout

I think it’s really important to ensure the hospitalist group always has the target number of providers working each day. Many groups have experienced staffing deficits for so long that they’ve essentially given up on this goal, and staffing levels vary day to day. This means each provider has uncertainty regarding how often he will be scheduled on days with fewer than the targeted numbers of providers working.

All hospitalist groups should ensure their schedule has day-shift providers work a meaningful series of shifts consecutively to support good patient-provider continuity. I think “continuity is king” and influences efficiency, quality of care, and provider burnout. Of course, there is tension between working many consecutive day shifts and still having a reasonable lifestyle; you’ll have to make up your own mind about the sweet spot between these to competing needs.

Schedule and number of shifts are only part of the burnout picture. The nature of hospitalist work, including EHR frustrations and distressing conversations regarding observation status, etc., probably has more significant influence on burnout and job satisfaction than does the work schedule itself.

But there is still lots of value in thinking carefully about your group’s work schedule and making adjustments where needed. The schedule is a lot easier to change than the nature of the work itself.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Contact him at [email protected].

Burnout is influenced by a seemingly infinite combination of variables. An optimal schedule alone isn’t the key to preventing it, but maybe a good schedule can reduce your risk you’ll suffer from it.

Smart people who have spent years as hospitalists, working multiple different schedules, have formed a variety of conclusions about which work schedules best reduce the risk of burnout. There’s no meaningful research to settle the question, so everyone will have to reach their own conclusions, as I’ve done here.

Scheduling flexibility: Often overlooked?

Someone who typically works the same number of consecutive day shifts, each of which is the same duration, might suffer from the monotony and inexorable predictability. Schedules that vary the number of consecutive day shifts, the intensity or length of shifts, and the number of consecutive days off might result in lower rates of burnout. This is especially likely to be the case if each provider has some flexibility to control how her schedule varies over time.

Personal time goes on the calendar first

Those who have a regularly repeating work schedule tend to work hard arranging such important things as family vacations on days the schedule dictates. In other words, the first thing that goes on the personal calendar are the weeks of work; they’re “X-ed” out and personal events filled into the remaining days.

That’s fine for many personal activities, but it means the hospitalist might tend to set a pretty high bar for activities that are worth negotiating alterations to the usual schedule. For example, you might want to see U2 but decide to skip their concert in your town since it falls in the middle of your regularly scheduled week of work. Maybe that’s not a big deal (Isn’t U2 overplayed and out of date anyway?), but an accumulation of small sacrifices like this might increase resentment of work.

It’s possible to organize a hospitalist group schedule in which each provider’s personally requested days off, like the U2 concert, go on the work calendar first, and the clinical schedule is built around them. It can get pretty time consuming to manage, but might be a worthwhile investment to reduce burnout risk.

A paradox: Fewer shifts could increase burnout risk

I’m convinced many hospitalists make the mistake of seeking to maximize their number of days off with the idea that it will be good for happiness, career longevity, burnout, etc. While having more days off provides more time for nonwork activities and rest/recovery from work, it usually means the average workday is busier and more stressful to maintain expected levels of productivity. The net effect for some seems to be increased burnout.

Consider someone who has been working 182 hospitalist shifts and generating a total of 2,114 billed encounters annually (both are the most recent national medians available from surveys). This hospitalist successfully negotiates a reduction to 161 annual shifts. This would probably feel good to anyone at first, but keep in mind that it means the average number of daily encounters to maintain median annual productivity would increase 13% (from 11.6 to 13.1 in this example). That is, each day of work just got 13% busier.

I regularly encounter career hospitalists with more than 10 years of experience who say they still appreciate – or even are addicted to – having lots of days off. But the worked days often are so busy they don’t know how long they can keep doing it. It is possible some of them might be happier and less burned out if they work more shifts annually, and the average shift is meaningfully less busy.

The “right” number of shifts depends on a combination of personal and economic factors. Rather than focusing almost exclusively on the number of shifts worked annually, it may be better to think about the total amount of annual work measured in billed encounters, or wRVUs [work relative value units], and how it is titrated out on the calendar.

Other scheduling attributes and burnout

I think it’s really important to ensure the hospitalist group always has the target number of providers working each day. Many groups have experienced staffing deficits for so long that they’ve essentially given up on this goal, and staffing levels vary day to day. This means each provider has uncertainty regarding how often he will be scheduled on days with fewer than the targeted numbers of providers working.

All hospitalist groups should ensure their schedule has day-shift providers work a meaningful series of shifts consecutively to support good patient-provider continuity. I think “continuity is king” and influences efficiency, quality of care, and provider burnout. Of course, there is tension between working many consecutive day shifts and still having a reasonable lifestyle; you’ll have to make up your own mind about the sweet spot between these to competing needs.

Schedule and number of shifts are only part of the burnout picture. The nature of hospitalist work, including EHR frustrations and distressing conversations regarding observation status, etc., probably has more significant influence on burnout and job satisfaction than does the work schedule itself.

But there is still lots of value in thinking carefully about your group’s work schedule and making adjustments where needed. The schedule is a lot easier to change than the nature of the work itself.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Contact him at [email protected].

A U.S. model for Italian hospitals?

In the United States, family physicians (general practitioners) used to manage their patients in the hospital, either as the primary care doctor or in consultation with specialists. Only since the 1990s has a new kind of physician gained widespread acceptance: the hospitalist (“specialist of inpatient care”).1

In Italy the process has not been the same. In our health care system, primary care physicians have always transferred the responsibility of hospital care to an inpatient team. Actually, our hospital-based doctors dedicate their whole working time to inpatient care, and general practitioners are not expected to go to the hospital. The patients were (and are) admitted to one ward or another according to their main clinical problem.

Little by little, a huge number of organ specialty and subspecialty wards have filled Italian hospitals. In this context, the internal medicine specialty was unable to occupy its characteristic role, so that, a few years ago, the medical community wondered if the specialty should have continued to exist.

Anyway, as a result of hyperspecialization, we have many different specialists in inpatient care who are not specialists in global inpatient care.

Nowadays, in our country we are faced with a dramatic epidemiologic change. The Italian population is aging and the majority of patients have not only one clinical problem but multiple comorbidities. When these patients reach the emergency department, it is not easy to identify the main clinical problem and assign him/her to an organ specialty unit. And when he or she eventually arrives there, a considerable number of consultants is frequently required. The vision of organ specialists is not holistic, and they are more prone to maximizing their tools than rationalizing them. So, at present, our traditional hospital model has been generating care fragmentation, overproduction of diagnoses, overprescription of drugs, and increasing costs.

It is obvious that a new model is necessary for the future, and we look with great interest at the American hospitalist model.

We need a new hospital-based clinician who has wide-ranging competencies, and is able to define priorities and appropriateness of care when a patient requires multiple specialists’ interventions; one who is autonomous in performing basic procedures and expert in perioperative medicine; prompt to communicate with primary care doctors at the time of admission and discharge; and prepared to work in managed-care organizations.

We wonder: Are Italian hospital-based internists – the only specialists in global inpatient care – suited to this role?

We think so. However, current Italian training in internal medicine is focused mainly on scientific bases of diseases, pathophysiological, and clinical aspects. Concepts such as complexity or the management of patients with comorbidities are quite difficult to teach to medical school students and therefore often neglected. As a result, internal medicine physicians require a prolonged practical training.

Inspired by the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine published by the Society of Hospital Medicine, this year in Genoa (the birthplace of Christopher Columbus) we started a 2-year second-level University Master course, called “Hospitalist: Managing complexity in Internal Medicine inpatients” for 35 internal medicine specialists. It is the fruit of collaboration between the main association of Italian hospital-based internists (Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine, or FADOI) and the University of Genoa’s Department of Internal Medicine, Academy of Health Management, and the Center of Simulation and Advanced Training.

In Italy, this is the first concrete initiative to train, and better define, this new type of physician expert in the management of inpatients.

According to SHM’s definition of a hospitalist, we think that the activities of this new physician should also include teaching and research related to hospital medicine. And as Dr. Steven Pantilat wrote, “patient safety, leadership, palliative care and quality improvement are the issues that pertain to all hospitalists.”2

Theoretically, the development of the hospitalist model should be easier in Italy when compared to the United States. Dr. Robert Wachter and Dr. Lee Goldman wrote in 1996 about the objections to the hospitalist model of American primary care physicians (“to preserve continuity”) and specialists (“fewer consultations, lower income”), but in Italy family doctors do not usually follow their patients in the hospital, and specialists have no incentive for in-hospital consultations.3 Moreover, patients with comorbidities, or pathologies on the border between medicine and surgery (e.g. cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, polytrauma, etc.), are already often assigned to internal medicine, and in the smallest hospitals, the internist is most of the time the only specialist doctor continually present.

Nevertheless, the Italian hospitalist model will be a challenge. We know we have to deal with organ specialists, but we strongly believe that this is the most appropriate and the most sustainable model for the future of the Italian hospitals. Our wish is not to become the “bosses” of the hospital, but to ensure global, coordinated, and respectful care to present and future patients.

Published outcomes studies demonstrate that the U.S. hospitalist model has led to consistent and pronounced cost saving with no loss in quality.4 In the United States, the hospitalist field has grown from a few hundred physicians to more than 50,000,5 making it the fastest growing physician specialty in medical history.

Why should the same not occur in Italy?

References

1. Baudendistel TE, Watcher RM. The evolution of the hospitalist movement in USA. Clin Med JRCPL. 2002;2:327-30.

2. Pantilat S. What is a Hospitalist? The Hospitalist 2006 February;2006(2).

3. Wachter RM, Goldman Lee. The emerging role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

4. White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:58:1-22. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/58.

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-11.

Valerio Verdiani, MD, director of internal medicine, Grosseto, Italy. Francesco Orlandini, MD, internal medicine, health administrator, ASL4 Liguria, Chiavari (GE), Italy. Micaela La Regina, MD, internal medicine, risk management and clinical governance, ASL5 Liguria, La Spezia, Italy. Giovanni Murialdo, MD, department of internal medicine and medical specialty, University of Genoa (Italy). Andrea Fontanella, MD, director of medicine department, president of the Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine (FADOI), Naples, Italy. Mauro Silingardi, MD, director of internal medicine, director of training and refresher of FADOI, Bologna, Italy.

In the United States, family physicians (general practitioners) used to manage their patients in the hospital, either as the primary care doctor or in consultation with specialists. Only since the 1990s has a new kind of physician gained widespread acceptance: the hospitalist (“specialist of inpatient care”).1

In Italy the process has not been the same. In our health care system, primary care physicians have always transferred the responsibility of hospital care to an inpatient team. Actually, our hospital-based doctors dedicate their whole working time to inpatient care, and general practitioners are not expected to go to the hospital. The patients were (and are) admitted to one ward or another according to their main clinical problem.

Little by little, a huge number of organ specialty and subspecialty wards have filled Italian hospitals. In this context, the internal medicine specialty was unable to occupy its characteristic role, so that, a few years ago, the medical community wondered if the specialty should have continued to exist.

Anyway, as a result of hyperspecialization, we have many different specialists in inpatient care who are not specialists in global inpatient care.

Nowadays, in our country we are faced with a dramatic epidemiologic change. The Italian population is aging and the majority of patients have not only one clinical problem but multiple comorbidities. When these patients reach the emergency department, it is not easy to identify the main clinical problem and assign him/her to an organ specialty unit. And when he or she eventually arrives there, a considerable number of consultants is frequently required. The vision of organ specialists is not holistic, and they are more prone to maximizing their tools than rationalizing them. So, at present, our traditional hospital model has been generating care fragmentation, overproduction of diagnoses, overprescription of drugs, and increasing costs.

It is obvious that a new model is necessary for the future, and we look with great interest at the American hospitalist model.

We need a new hospital-based clinician who has wide-ranging competencies, and is able to define priorities and appropriateness of care when a patient requires multiple specialists’ interventions; one who is autonomous in performing basic procedures and expert in perioperative medicine; prompt to communicate with primary care doctors at the time of admission and discharge; and prepared to work in managed-care organizations.

We wonder: Are Italian hospital-based internists – the only specialists in global inpatient care – suited to this role?

We think so. However, current Italian training in internal medicine is focused mainly on scientific bases of diseases, pathophysiological, and clinical aspects. Concepts such as complexity or the management of patients with comorbidities are quite difficult to teach to medical school students and therefore often neglected. As a result, internal medicine physicians require a prolonged practical training.

Inspired by the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine published by the Society of Hospital Medicine, this year in Genoa (the birthplace of Christopher Columbus) we started a 2-year second-level University Master course, called “Hospitalist: Managing complexity in Internal Medicine inpatients” for 35 internal medicine specialists. It is the fruit of collaboration between the main association of Italian hospital-based internists (Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine, or FADOI) and the University of Genoa’s Department of Internal Medicine, Academy of Health Management, and the Center of Simulation and Advanced Training.

In Italy, this is the first concrete initiative to train, and better define, this new type of physician expert in the management of inpatients.

According to SHM’s definition of a hospitalist, we think that the activities of this new physician should also include teaching and research related to hospital medicine. And as Dr. Steven Pantilat wrote, “patient safety, leadership, palliative care and quality improvement are the issues that pertain to all hospitalists.”2

Theoretically, the development of the hospitalist model should be easier in Italy when compared to the United States. Dr. Robert Wachter and Dr. Lee Goldman wrote in 1996 about the objections to the hospitalist model of American primary care physicians (“to preserve continuity”) and specialists (“fewer consultations, lower income”), but in Italy family doctors do not usually follow their patients in the hospital, and specialists have no incentive for in-hospital consultations.3 Moreover, patients with comorbidities, or pathologies on the border between medicine and surgery (e.g. cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, polytrauma, etc.), are already often assigned to internal medicine, and in the smallest hospitals, the internist is most of the time the only specialist doctor continually present.

Nevertheless, the Italian hospitalist model will be a challenge. We know we have to deal with organ specialists, but we strongly believe that this is the most appropriate and the most sustainable model for the future of the Italian hospitals. Our wish is not to become the “bosses” of the hospital, but to ensure global, coordinated, and respectful care to present and future patients.

Published outcomes studies demonstrate that the U.S. hospitalist model has led to consistent and pronounced cost saving with no loss in quality.4 In the United States, the hospitalist field has grown from a few hundred physicians to more than 50,000,5 making it the fastest growing physician specialty in medical history.

Why should the same not occur in Italy?

References

1. Baudendistel TE, Watcher RM. The evolution of the hospitalist movement in USA. Clin Med JRCPL. 2002;2:327-30.

2. Pantilat S. What is a Hospitalist? The Hospitalist 2006 February;2006(2).

3. Wachter RM, Goldman Lee. The emerging role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

4. White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:58:1-22. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/58.

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-11.

Valerio Verdiani, MD, director of internal medicine, Grosseto, Italy. Francesco Orlandini, MD, internal medicine, health administrator, ASL4 Liguria, Chiavari (GE), Italy. Micaela La Regina, MD, internal medicine, risk management and clinical governance, ASL5 Liguria, La Spezia, Italy. Giovanni Murialdo, MD, department of internal medicine and medical specialty, University of Genoa (Italy). Andrea Fontanella, MD, director of medicine department, president of the Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine (FADOI), Naples, Italy. Mauro Silingardi, MD, director of internal medicine, director of training and refresher of FADOI, Bologna, Italy.

In the United States, family physicians (general practitioners) used to manage their patients in the hospital, either as the primary care doctor or in consultation with specialists. Only since the 1990s has a new kind of physician gained widespread acceptance: the hospitalist (“specialist of inpatient care”).1

In Italy the process has not been the same. In our health care system, primary care physicians have always transferred the responsibility of hospital care to an inpatient team. Actually, our hospital-based doctors dedicate their whole working time to inpatient care, and general practitioners are not expected to go to the hospital. The patients were (and are) admitted to one ward or another according to their main clinical problem.

Little by little, a huge number of organ specialty and subspecialty wards have filled Italian hospitals. In this context, the internal medicine specialty was unable to occupy its characteristic role, so that, a few years ago, the medical community wondered if the specialty should have continued to exist.

Anyway, as a result of hyperspecialization, we have many different specialists in inpatient care who are not specialists in global inpatient care.

Nowadays, in our country we are faced with a dramatic epidemiologic change. The Italian population is aging and the majority of patients have not only one clinical problem but multiple comorbidities. When these patients reach the emergency department, it is not easy to identify the main clinical problem and assign him/her to an organ specialty unit. And when he or she eventually arrives there, a considerable number of consultants is frequently required. The vision of organ specialists is not holistic, and they are more prone to maximizing their tools than rationalizing them. So, at present, our traditional hospital model has been generating care fragmentation, overproduction of diagnoses, overprescription of drugs, and increasing costs.

It is obvious that a new model is necessary for the future, and we look with great interest at the American hospitalist model.

We need a new hospital-based clinician who has wide-ranging competencies, and is able to define priorities and appropriateness of care when a patient requires multiple specialists’ interventions; one who is autonomous in performing basic procedures and expert in perioperative medicine; prompt to communicate with primary care doctors at the time of admission and discharge; and prepared to work in managed-care organizations.

We wonder: Are Italian hospital-based internists – the only specialists in global inpatient care – suited to this role?

We think so. However, current Italian training in internal medicine is focused mainly on scientific bases of diseases, pathophysiological, and clinical aspects. Concepts such as complexity or the management of patients with comorbidities are quite difficult to teach to medical school students and therefore often neglected. As a result, internal medicine physicians require a prolonged practical training.

Inspired by the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine published by the Society of Hospital Medicine, this year in Genoa (the birthplace of Christopher Columbus) we started a 2-year second-level University Master course, called “Hospitalist: Managing complexity in Internal Medicine inpatients” for 35 internal medicine specialists. It is the fruit of collaboration between the main association of Italian hospital-based internists (Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine, or FADOI) and the University of Genoa’s Department of Internal Medicine, Academy of Health Management, and the Center of Simulation and Advanced Training.

In Italy, this is the first concrete initiative to train, and better define, this new type of physician expert in the management of inpatients.

According to SHM’s definition of a hospitalist, we think that the activities of this new physician should also include teaching and research related to hospital medicine. And as Dr. Steven Pantilat wrote, “patient safety, leadership, palliative care and quality improvement are the issues that pertain to all hospitalists.”2

Theoretically, the development of the hospitalist model should be easier in Italy when compared to the United States. Dr. Robert Wachter and Dr. Lee Goldman wrote in 1996 about the objections to the hospitalist model of American primary care physicians (“to preserve continuity”) and specialists (“fewer consultations, lower income”), but in Italy family doctors do not usually follow their patients in the hospital, and specialists have no incentive for in-hospital consultations.3 Moreover, patients with comorbidities, or pathologies on the border between medicine and surgery (e.g. cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, polytrauma, etc.), are already often assigned to internal medicine, and in the smallest hospitals, the internist is most of the time the only specialist doctor continually present.

Nevertheless, the Italian hospitalist model will be a challenge. We know we have to deal with organ specialists, but we strongly believe that this is the most appropriate and the most sustainable model for the future of the Italian hospitals. Our wish is not to become the “bosses” of the hospital, but to ensure global, coordinated, and respectful care to present and future patients.

Published outcomes studies demonstrate that the U.S. hospitalist model has led to consistent and pronounced cost saving with no loss in quality.4 In the United States, the hospitalist field has grown from a few hundred physicians to more than 50,000,5 making it the fastest growing physician specialty in medical history.

Why should the same not occur in Italy?

References

1. Baudendistel TE, Watcher RM. The evolution of the hospitalist movement in USA. Clin Med JRCPL. 2002;2:327-30.

2. Pantilat S. What is a Hospitalist? The Hospitalist 2006 February;2006(2).

3. Wachter RM, Goldman Lee. The emerging role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

4. White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:58:1-22. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/58.

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-11.

Valerio Verdiani, MD, director of internal medicine, Grosseto, Italy. Francesco Orlandini, MD, internal medicine, health administrator, ASL4 Liguria, Chiavari (GE), Italy. Micaela La Regina, MD, internal medicine, risk management and clinical governance, ASL5 Liguria, La Spezia, Italy. Giovanni Murialdo, MD, department of internal medicine and medical specialty, University of Genoa (Italy). Andrea Fontanella, MD, director of medicine department, president of the Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine (FADOI), Naples, Italy. Mauro Silingardi, MD, director of internal medicine, director of training and refresher of FADOI, Bologna, Italy.

Peer mentorship, groups help combat burnout in female physicians

NEW YORK – Female physicians are at higher risk for burnout compared with their male counterparts, and the reasons and potential solutions for the problem were addressed at a symposium during the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The work environment for women has improved over time, but lingering implicit and unconscious biases are part of the reason for the high burnout rate among women who are physicians, as are some inherent biological differences, according to Cynthia M. Stonnington, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix.

In this video interview, Dr. Stonnington, symposium chair, discussed potential solutions, including facilitated peer mentorship and group support. She also reviewed recent data on how group support can be of benefit, and noted that “there is power in numbers.

“,” she said.

Dr. Stonnington reported having no disclosures.

NEW YORK – Female physicians are at higher risk for burnout compared with their male counterparts, and the reasons and potential solutions for the problem were addressed at a symposium during the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The work environment for women has improved over time, but lingering implicit and unconscious biases are part of the reason for the high burnout rate among women who are physicians, as are some inherent biological differences, according to Cynthia M. Stonnington, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix.

In this video interview, Dr. Stonnington, symposium chair, discussed potential solutions, including facilitated peer mentorship and group support. She also reviewed recent data on how group support can be of benefit, and noted that “there is power in numbers.

“,” she said.

Dr. Stonnington reported having no disclosures.

NEW YORK – Female physicians are at higher risk for burnout compared with their male counterparts, and the reasons and potential solutions for the problem were addressed at a symposium during the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The work environment for women has improved over time, but lingering implicit and unconscious biases are part of the reason for the high burnout rate among women who are physicians, as are some inherent biological differences, according to Cynthia M. Stonnington, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix.

In this video interview, Dr. Stonnington, symposium chair, discussed potential solutions, including facilitated peer mentorship and group support. She also reviewed recent data on how group support can be of benefit, and noted that “there is power in numbers.

“,” she said.

Dr. Stonnington reported having no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM APA

Specialty practices hire more physician assistants and nurse practitioners

based on data from a review of approximately 90% of physician practices in the United States.

The employment of advanced practice clinicians in primary care continues to grow, but their presence in specialty practices has not been well studied, wrote Grant R. Martsolf, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues. In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers used the proprietary SK&A data set to examine employment in specialty practices between 2008 and 2016.

Overall, 28% of all specialty practices employed advanced practice clinicians in 2016 – a 22% increase from 2008. Nearly half of multispecialty practices (49%) employed advanced practice clinicians, as did at least 25% of dermatology, cardiology, obstetrics-gynecology, orthopedic surgery, and gastroenterology practices.

Plastic surgery and ophthalmology practices were the least likely to employ advanced practice clinicians. Surgical practices were more likely to employ physician assistants than nurse practitioners, but the other specialty practices were more likely to employ NPs than PAs.

The growth in employment of advanced practice clinicians may be driven by factors such as economics and the expanding roles for advanced practice clinicians in specialty practice, the researchers said.

The findings were limited by the inclusion of outpatient providers only, and by the lack of information about the exact duties of advanced practice clinicians in each practice, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that advanced practice clinicians will become even more prevalent in specialty care, and “future research will need to understand their contributions to access, quality, and value,” they wrote.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Martsolf GR et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1515 .

based on data from a review of approximately 90% of physician practices in the United States.

The employment of advanced practice clinicians in primary care continues to grow, but their presence in specialty practices has not been well studied, wrote Grant R. Martsolf, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues. In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers used the proprietary SK&A data set to examine employment in specialty practices between 2008 and 2016.

Overall, 28% of all specialty practices employed advanced practice clinicians in 2016 – a 22% increase from 2008. Nearly half of multispecialty practices (49%) employed advanced practice clinicians, as did at least 25% of dermatology, cardiology, obstetrics-gynecology, orthopedic surgery, and gastroenterology practices.

Plastic surgery and ophthalmology practices were the least likely to employ advanced practice clinicians. Surgical practices were more likely to employ physician assistants than nurse practitioners, but the other specialty practices were more likely to employ NPs than PAs.

The growth in employment of advanced practice clinicians may be driven by factors such as economics and the expanding roles for advanced practice clinicians in specialty practice, the researchers said.

The findings were limited by the inclusion of outpatient providers only, and by the lack of information about the exact duties of advanced practice clinicians in each practice, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that advanced practice clinicians will become even more prevalent in specialty care, and “future research will need to understand their contributions to access, quality, and value,” they wrote.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Martsolf GR et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1515 .

based on data from a review of approximately 90% of physician practices in the United States.

The employment of advanced practice clinicians in primary care continues to grow, but their presence in specialty practices has not been well studied, wrote Grant R. Martsolf, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues. In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers used the proprietary SK&A data set to examine employment in specialty practices between 2008 and 2016.

Overall, 28% of all specialty practices employed advanced practice clinicians in 2016 – a 22% increase from 2008. Nearly half of multispecialty practices (49%) employed advanced practice clinicians, as did at least 25% of dermatology, cardiology, obstetrics-gynecology, orthopedic surgery, and gastroenterology practices.

Plastic surgery and ophthalmology practices were the least likely to employ advanced practice clinicians. Surgical practices were more likely to employ physician assistants than nurse practitioners, but the other specialty practices were more likely to employ NPs than PAs.

The growth in employment of advanced practice clinicians may be driven by factors such as economics and the expanding roles for advanced practice clinicians in specialty practice, the researchers said.

The findings were limited by the inclusion of outpatient providers only, and by the lack of information about the exact duties of advanced practice clinicians in each practice, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that advanced practice clinicians will become even more prevalent in specialty care, and “future research will need to understand their contributions to access, quality, and value,” they wrote.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Martsolf GR et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1515 .

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Prompt palliative care cut hospital costs in pooled study

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Average cost savings per admission were $3,237 overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P-values less than .001).

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of six cohort studies of 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease.

Disclosures: Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

CMS floats Medicare direct provider contracting

Under a direct provider contracting (DPC) arrangement, Medicare could pay physicians or physician groups a monthly fee to deliver a specific set of services to beneficiaries, who would gain greater access to the physicians. The physicians would be accountable for those Medicare patients’ costs and care quality.

CMS is looking at how to incorporate this concept into the Medicare ranks. On April 23, CMS issued a request for information (RFI) seeking input across a wide range of topics, including provider/state participation, beneficiary participation, payment, general model design, program integrity and beneficiary protection, and how such models would fit within the existing accountable care organization framework.

The RFI offered one possible vision on how a direct provider contracting model could work.

“Under a primary care–focused DPC model, CMS could enter into arrangements with primary care practices under which CMS would pay these participating practices a fixed per beneficiary per month (PBPM) payment to cover the primary care services the practice would be expected to furnish under the model, which may include office visits, certain office-based procedures, and other non–visit-based services covered under the physician fee schedule, and flexibility in how otherwise billable services are delivered,” the RFI states.

Physicians could also earn performance bonuses, depending on how the DPC is structured, through “performance-based incentives for total cost of care and quality.”

CMS noted it also “could test ways to reduce administrative burden though innovative changes to claims submission processes for services included in the PBPM payment under these models.”

The direct provider contracting idea grew out of a previous RFI issued in 2017 by CMS’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to collect ideas on new ways to deliver patient-centered care. The agency released the more than 1,000 comments received from that request on the same day it issued the RFI on direct provider contracting.

In those comments, a number of physician groups offered support for a direct-contracting approach.

For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that it “sees continued growth and interest in family physicians adopting this practice model in all settings types, including rural and underserved communities.” And the AAFP suggested that the innovation center should work with DPC organizations to learn more about them.

The American College of Physicians reiterated its previous position that it “supports physician and patient choice of practice and delivery models that are accessible, ethical, and viable and that strengthen the patient-physician relationship.” But the ACP raised a number of issues that could impede access to care or result in lower quality care.

The American Medical Association offered support for “testing of models in which physicians have the ability to deliver more or different services to patients who need them and to be paid more for doing so.”

The AMA suggested that some of the models to be tested include allowing patients to contract directly with physicians, with Medicare paying its fee schedule rates and patients paying the difference; allowing patients to receive their care from DPC practices and get reimbursed by Medicare; or allowing “physicians to define a team of providers who will provide all of the treatment needed for an acute condition or management of a chronic condition, and then allowing patients who select the team to receive all of the services related to their condition from the team in return for a single predefined cost-sharing amount.”

Comments on the RFI are due May 25.

Under a direct provider contracting (DPC) arrangement, Medicare could pay physicians or physician groups a monthly fee to deliver a specific set of services to beneficiaries, who would gain greater access to the physicians. The physicians would be accountable for those Medicare patients’ costs and care quality.

CMS is looking at how to incorporate this concept into the Medicare ranks. On April 23, CMS issued a request for information (RFI) seeking input across a wide range of topics, including provider/state participation, beneficiary participation, payment, general model design, program integrity and beneficiary protection, and how such models would fit within the existing accountable care organization framework.

The RFI offered one possible vision on how a direct provider contracting model could work.

“Under a primary care–focused DPC model, CMS could enter into arrangements with primary care practices under which CMS would pay these participating practices a fixed per beneficiary per month (PBPM) payment to cover the primary care services the practice would be expected to furnish under the model, which may include office visits, certain office-based procedures, and other non–visit-based services covered under the physician fee schedule, and flexibility in how otherwise billable services are delivered,” the RFI states.

Physicians could also earn performance bonuses, depending on how the DPC is structured, through “performance-based incentives for total cost of care and quality.”

CMS noted it also “could test ways to reduce administrative burden though innovative changes to claims submission processes for services included in the PBPM payment under these models.”

The direct provider contracting idea grew out of a previous RFI issued in 2017 by CMS’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to collect ideas on new ways to deliver patient-centered care. The agency released the more than 1,000 comments received from that request on the same day it issued the RFI on direct provider contracting.

In those comments, a number of physician groups offered support for a direct-contracting approach.

For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that it “sees continued growth and interest in family physicians adopting this practice model in all settings types, including rural and underserved communities.” And the AAFP suggested that the innovation center should work with DPC organizations to learn more about them.

The American College of Physicians reiterated its previous position that it “supports physician and patient choice of practice and delivery models that are accessible, ethical, and viable and that strengthen the patient-physician relationship.” But the ACP raised a number of issues that could impede access to care or result in lower quality care.

The American Medical Association offered support for “testing of models in which physicians have the ability to deliver more or different services to patients who need them and to be paid more for doing so.”

The AMA suggested that some of the models to be tested include allowing patients to contract directly with physicians, with Medicare paying its fee schedule rates and patients paying the difference; allowing patients to receive their care from DPC practices and get reimbursed by Medicare; or allowing “physicians to define a team of providers who will provide all of the treatment needed for an acute condition or management of a chronic condition, and then allowing patients who select the team to receive all of the services related to their condition from the team in return for a single predefined cost-sharing amount.”

Comments on the RFI are due May 25.

Under a direct provider contracting (DPC) arrangement, Medicare could pay physicians or physician groups a monthly fee to deliver a specific set of services to beneficiaries, who would gain greater access to the physicians. The physicians would be accountable for those Medicare patients’ costs and care quality.

CMS is looking at how to incorporate this concept into the Medicare ranks. On April 23, CMS issued a request for information (RFI) seeking input across a wide range of topics, including provider/state participation, beneficiary participation, payment, general model design, program integrity and beneficiary protection, and how such models would fit within the existing accountable care organization framework.

The RFI offered one possible vision on how a direct provider contracting model could work.

“Under a primary care–focused DPC model, CMS could enter into arrangements with primary care practices under which CMS would pay these participating practices a fixed per beneficiary per month (PBPM) payment to cover the primary care services the practice would be expected to furnish under the model, which may include office visits, certain office-based procedures, and other non–visit-based services covered under the physician fee schedule, and flexibility in how otherwise billable services are delivered,” the RFI states.

Physicians could also earn performance bonuses, depending on how the DPC is structured, through “performance-based incentives for total cost of care and quality.”

CMS noted it also “could test ways to reduce administrative burden though innovative changes to claims submission processes for services included in the PBPM payment under these models.”

The direct provider contracting idea grew out of a previous RFI issued in 2017 by CMS’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to collect ideas on new ways to deliver patient-centered care. The agency released the more than 1,000 comments received from that request on the same day it issued the RFI on direct provider contracting.

In those comments, a number of physician groups offered support for a direct-contracting approach.

For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that it “sees continued growth and interest in family physicians adopting this practice model in all settings types, including rural and underserved communities.” And the AAFP suggested that the innovation center should work with DPC organizations to learn more about them.

The American College of Physicians reiterated its previous position that it “supports physician and patient choice of practice and delivery models that are accessible, ethical, and viable and that strengthen the patient-physician relationship.” But the ACP raised a number of issues that could impede access to care or result in lower quality care.

The American Medical Association offered support for “testing of models in which physicians have the ability to deliver more or different services to patients who need them and to be paid more for doing so.”

The AMA suggested that some of the models to be tested include allowing patients to contract directly with physicians, with Medicare paying its fee schedule rates and patients paying the difference; allowing patients to receive their care from DPC practices and get reimbursed by Medicare; or allowing “physicians to define a team of providers who will provide all of the treatment needed for an acute condition or management of a chronic condition, and then allowing patients who select the team to receive all of the services related to their condition from the team in return for a single predefined cost-sharing amount.”

Comments on the RFI are due May 25.

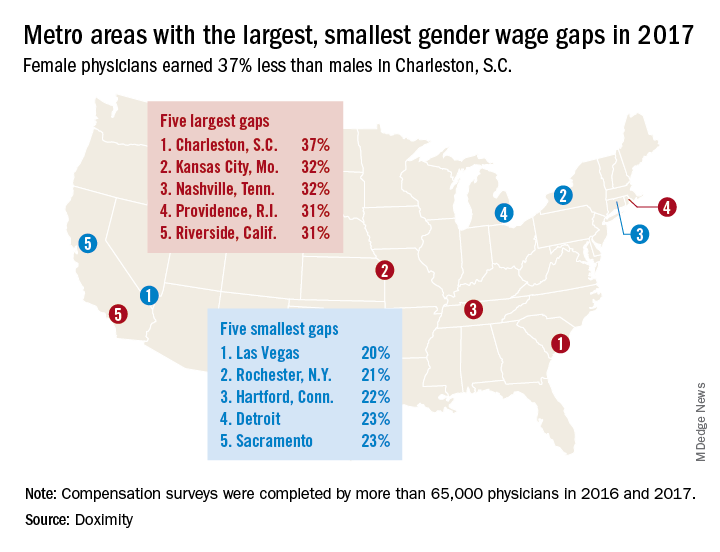

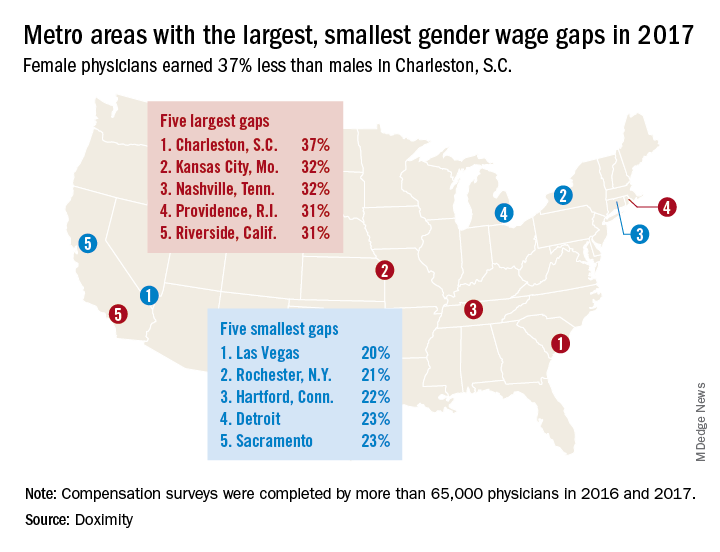

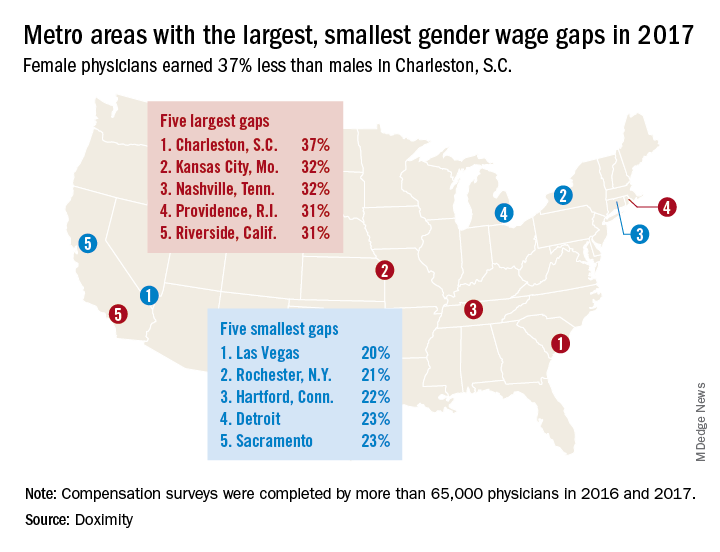

Female physicians face enduring wage gap

Male physicians make more money than female physicians, and that seems to be a rule with few exceptions. Among the 50 largest metro areas, there were none where women earn as much as men, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

The metro area that comes the closest is Las Vegas, where female physicians earned 20% less – that works out to $73,654 – than their male counterparts in 2017. Rochester, N.Y., had the smallest gap in terms of dollars ($68,758) and the second-smallest percent difference (21%), Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report.

A quick look at the 2016 data shows that the wage gap between female and male physicians increased from 26.5% to 27.7% in 2017, going from more than $92,000 to $105,000. “Medicine is a highly trained field, and as such, one might expect the gender wage gap to be less prominent here than in other industries. However, the gap endures, despite the level of education required to practice medicine and market forces suggesting that this gap should shrink,” Doximity said.

Male physicians make more money than female physicians, and that seems to be a rule with few exceptions. Among the 50 largest metro areas, there were none where women earn as much as men, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

The metro area that comes the closest is Las Vegas, where female physicians earned 20% less – that works out to $73,654 – than their male counterparts in 2017. Rochester, N.Y., had the smallest gap in terms of dollars ($68,758) and the second-smallest percent difference (21%), Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report.

A quick look at the 2016 data shows that the wage gap between female and male physicians increased from 26.5% to 27.7% in 2017, going from more than $92,000 to $105,000. “Medicine is a highly trained field, and as such, one might expect the gender wage gap to be less prominent here than in other industries. However, the gap endures, despite the level of education required to practice medicine and market forces suggesting that this gap should shrink,” Doximity said.

Male physicians make more money than female physicians, and that seems to be a rule with few exceptions. Among the 50 largest metro areas, there were none where women earn as much as men, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

The metro area that comes the closest is Las Vegas, where female physicians earned 20% less – that works out to $73,654 – than their male counterparts in 2017. Rochester, N.Y., had the smallest gap in terms of dollars ($68,758) and the second-smallest percent difference (21%), Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report.

A quick look at the 2016 data shows that the wage gap between female and male physicians increased from 26.5% to 27.7% in 2017, going from more than $92,000 to $105,000. “Medicine is a highly trained field, and as such, one might expect the gender wage gap to be less prominent here than in other industries. However, the gap endures, despite the level of education required to practice medicine and market forces suggesting that this gap should shrink,” Doximity said.

VIDEO: Fix physician burnout? You need more than yoga

NEW ORLEANS – Among a growing number of physicians, the words of a Righteous Brothers’ song ring true about their careers: They’ve lost that loving feeling.

For burned-out physicians, “they’ve lost that sense that they’re making a difference,” explained Susan Thompson Hingle, MD, of Southern Illinois University in Springfield. And the solutions aren’t simple. “You can’t yoga your way out of this,” Dr. Hingle cautioned.

At the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Dr. Hingle and Daisy Smith, MD, vice president of clinical programs at the ACP, talked about solutions to burnout, including how more traditional approaches can boost physician well-being, such as team-based care, physician champions, and increasing the pool of primary care providers.

But they also detailed ways that struggling physicians can find support from an unlikely source: their patients.

Dr. Smith’s video interview:

Dr. Hingle’s video interview: