User login

The Hospitalist only

CMS pushes ACOs to take on more risk

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are playing it too safe, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which wants to change the rules and push more ACOs into taking on more financial risk – with a little flexibility added in.

“ACOs were designed to move Medicare away from fee for service by encouraging providers to find efficiencies and innovative ways to deliver high-quality care to their patients while reducing costs, giving them the flexibility they need to focus on health outcomes over process,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during an Aug. 9 press conference.

That’s not what is happening now, Ms. Verma said. Under the current program, physicians and other health care professionals can participate in an ACO that takes on upside risk only – that is, to share in any of the savings it is able to generate – for up to 6 years before having to take on downside risk to return payment to the government if the ACO fails to hit spending targets.

“This environment has created a perverse incentive leading to the shocking present day reality that, after 6 years, over 82% of shared saving program ACOs are in an upside-only track, meaning that these ACOs have no incentive at all to reduce health care cost while improving outcomes as they were intended,” she said. “The program has not lived up to the accountability part of their name.”

In the aggregate, ACOs that only take on upside risk generally are spending more money and not generating the savings that ACOs in a two-sided risk arrangement are, she added.

To get more health care professionals into two-sided risk arrangements, the CMS released a proposed rule Aug. 9 that caps ACO participation in an upside risk–only arrangement for 2 years before having to migrate to a two-sided risk arrangement. To sweeten the pot, the CMS proposes to allow more flexibility for innovation and encouraging patients to maintain their health.

“On top of [antikickback law] waivers they already receive, we are proposing to allow ACOs that are taking risk to give incentive payments in order to reward patients for taking steps to achieve good health, such as gift cards for patients who receive necessary primary and preventive care,” she said, adding that ACOs who take on downside risk also will be eligible to receive payments for providing telehealth services.

ACOs also will need to adopt the 2015 edition of certified EHR technology and the CMS also will be looking to streamline quality measures, according to the proposal.

The CMS is extending current ACO contracts for 6 months, with the new rules, if finalized, going into effect in the middle of 2019.

The proposal also simplifies the ACO program by offering two tracks, as detailed in a blog post penned by Administrator Verma that appeared Aug. 9 in Health Affairs.

The Basic track “would feature a glide path for taking risk,” she wrote. “It would begin with up to 2 years of upside-only risk and then gradually transition in years 3, 4, and 5 to increasing levels of performance risk, concluding in year 5 at a level of risk that meets the standard to qualify as an advanced alternative payment model [APM]” under the Quality Payment Program. Those entering the enhanced track, taking on two-sided risk immediately, would need to meet the standard of an APM immediately.

The proposal also calls for more transparency and would require providers to alert Medicare beneficiaries that services are being provided in the context of an ACO and to explain what that means for their care.

Spending benchmarks would continue to be calculated using both regional and national spending trends. Program integrity also will be enhanced “by holding ACOs in two-sided models accountable for losses even if they exit midway through a performance year, and by authorizing termination of ACOs with multiple years of poor financial performance,” Ms. Verma wrote.

The Pathways to Success proposed rule was slated to be published in the Federal Register on Aug. 17. Comments are being accepted at regulations.gov until Oct. 16.

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are playing it too safe, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which wants to change the rules and push more ACOs into taking on more financial risk – with a little flexibility added in.

“ACOs were designed to move Medicare away from fee for service by encouraging providers to find efficiencies and innovative ways to deliver high-quality care to their patients while reducing costs, giving them the flexibility they need to focus on health outcomes over process,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during an Aug. 9 press conference.

That’s not what is happening now, Ms. Verma said. Under the current program, physicians and other health care professionals can participate in an ACO that takes on upside risk only – that is, to share in any of the savings it is able to generate – for up to 6 years before having to take on downside risk to return payment to the government if the ACO fails to hit spending targets.

“This environment has created a perverse incentive leading to the shocking present day reality that, after 6 years, over 82% of shared saving program ACOs are in an upside-only track, meaning that these ACOs have no incentive at all to reduce health care cost while improving outcomes as they were intended,” she said. “The program has not lived up to the accountability part of their name.”

In the aggregate, ACOs that only take on upside risk generally are spending more money and not generating the savings that ACOs in a two-sided risk arrangement are, she added.

To get more health care professionals into two-sided risk arrangements, the CMS released a proposed rule Aug. 9 that caps ACO participation in an upside risk–only arrangement for 2 years before having to migrate to a two-sided risk arrangement. To sweeten the pot, the CMS proposes to allow more flexibility for innovation and encouraging patients to maintain their health.

“On top of [antikickback law] waivers they already receive, we are proposing to allow ACOs that are taking risk to give incentive payments in order to reward patients for taking steps to achieve good health, such as gift cards for patients who receive necessary primary and preventive care,” she said, adding that ACOs who take on downside risk also will be eligible to receive payments for providing telehealth services.

ACOs also will need to adopt the 2015 edition of certified EHR technology and the CMS also will be looking to streamline quality measures, according to the proposal.

The CMS is extending current ACO contracts for 6 months, with the new rules, if finalized, going into effect in the middle of 2019.

The proposal also simplifies the ACO program by offering two tracks, as detailed in a blog post penned by Administrator Verma that appeared Aug. 9 in Health Affairs.

The Basic track “would feature a glide path for taking risk,” she wrote. “It would begin with up to 2 years of upside-only risk and then gradually transition in years 3, 4, and 5 to increasing levels of performance risk, concluding in year 5 at a level of risk that meets the standard to qualify as an advanced alternative payment model [APM]” under the Quality Payment Program. Those entering the enhanced track, taking on two-sided risk immediately, would need to meet the standard of an APM immediately.

The proposal also calls for more transparency and would require providers to alert Medicare beneficiaries that services are being provided in the context of an ACO and to explain what that means for their care.

Spending benchmarks would continue to be calculated using both regional and national spending trends. Program integrity also will be enhanced “by holding ACOs in two-sided models accountable for losses even if they exit midway through a performance year, and by authorizing termination of ACOs with multiple years of poor financial performance,” Ms. Verma wrote.

The Pathways to Success proposed rule was slated to be published in the Federal Register on Aug. 17. Comments are being accepted at regulations.gov until Oct. 16.

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are playing it too safe, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which wants to change the rules and push more ACOs into taking on more financial risk – with a little flexibility added in.

“ACOs were designed to move Medicare away from fee for service by encouraging providers to find efficiencies and innovative ways to deliver high-quality care to their patients while reducing costs, giving them the flexibility they need to focus on health outcomes over process,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during an Aug. 9 press conference.

That’s not what is happening now, Ms. Verma said. Under the current program, physicians and other health care professionals can participate in an ACO that takes on upside risk only – that is, to share in any of the savings it is able to generate – for up to 6 years before having to take on downside risk to return payment to the government if the ACO fails to hit spending targets.

“This environment has created a perverse incentive leading to the shocking present day reality that, after 6 years, over 82% of shared saving program ACOs are in an upside-only track, meaning that these ACOs have no incentive at all to reduce health care cost while improving outcomes as they were intended,” she said. “The program has not lived up to the accountability part of their name.”

In the aggregate, ACOs that only take on upside risk generally are spending more money and not generating the savings that ACOs in a two-sided risk arrangement are, she added.

To get more health care professionals into two-sided risk arrangements, the CMS released a proposed rule Aug. 9 that caps ACO participation in an upside risk–only arrangement for 2 years before having to migrate to a two-sided risk arrangement. To sweeten the pot, the CMS proposes to allow more flexibility for innovation and encouraging patients to maintain their health.

“On top of [antikickback law] waivers they already receive, we are proposing to allow ACOs that are taking risk to give incentive payments in order to reward patients for taking steps to achieve good health, such as gift cards for patients who receive necessary primary and preventive care,” she said, adding that ACOs who take on downside risk also will be eligible to receive payments for providing telehealth services.

ACOs also will need to adopt the 2015 edition of certified EHR technology and the CMS also will be looking to streamline quality measures, according to the proposal.

The CMS is extending current ACO contracts for 6 months, with the new rules, if finalized, going into effect in the middle of 2019.

The proposal also simplifies the ACO program by offering two tracks, as detailed in a blog post penned by Administrator Verma that appeared Aug. 9 in Health Affairs.

The Basic track “would feature a glide path for taking risk,” she wrote. “It would begin with up to 2 years of upside-only risk and then gradually transition in years 3, 4, and 5 to increasing levels of performance risk, concluding in year 5 at a level of risk that meets the standard to qualify as an advanced alternative payment model [APM]” under the Quality Payment Program. Those entering the enhanced track, taking on two-sided risk immediately, would need to meet the standard of an APM immediately.

The proposal also calls for more transparency and would require providers to alert Medicare beneficiaries that services are being provided in the context of an ACO and to explain what that means for their care.

Spending benchmarks would continue to be calculated using both regional and national spending trends. Program integrity also will be enhanced “by holding ACOs in two-sided models accountable for losses even if they exit midway through a performance year, and by authorizing termination of ACOs with multiple years of poor financial performance,” Ms. Verma wrote.

The Pathways to Success proposed rule was slated to be published in the Federal Register on Aug. 17. Comments are being accepted at regulations.gov until Oct. 16.

Ranked: State of the states’ health care

In the wild world of health care rankings, a year can make a big difference … or not.

Iowa fell from second to ninth over the course of the last year while Connecticut and South Dakota moved out of the top 10 to make way for Colorado and Maryland, according to WalletHub.

There was less movement at the other end of the rankings, however, with no change at all in the bottom five: Louisiana finished 51st again (the rankings include the District of Columbia), preceded by fellow repeaters Mississippi (50), Alaska (49), Arkansas (48), and North Carolina (47). Texas and Nevada did manage to move on up out of the bottom 11 – to 38th and 40th, respectively – at the expense of Oklahoma and Tennessee, WalletHub reported.

For 2018, the company compared the states and D.C. “across 40 measures of cost, accessibility and outcome,” which is five more measures than last year and a possible explanation for the changes at the top. The cost dimension’s five metrics included cost of medical visits and share of high out-of-pocket medical spending. The accessibility dimension consisted of 21 metrics, including average emergency department wait time and share of insured children. The outcomes dimension included 14 metrics, among them maternal mortality rate and share of adults with type 2 diabetes.

Vermont did well in both the outcomes (first) and cost (third) dimensions but only middle of the pack (23rd) in access. The District of Columbia was ranked first in cost and Maine was the leader in access. The lowest-ranked states in each category were Alaska (cost), Texas (access), and Mississippi (outcomes), according to the WalletHub analysis, which was based on data from such sources as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the United Health Foundation.

In the wild world of health care rankings, a year can make a big difference … or not.

Iowa fell from second to ninth over the course of the last year while Connecticut and South Dakota moved out of the top 10 to make way for Colorado and Maryland, according to WalletHub.

There was less movement at the other end of the rankings, however, with no change at all in the bottom five: Louisiana finished 51st again (the rankings include the District of Columbia), preceded by fellow repeaters Mississippi (50), Alaska (49), Arkansas (48), and North Carolina (47). Texas and Nevada did manage to move on up out of the bottom 11 – to 38th and 40th, respectively – at the expense of Oklahoma and Tennessee, WalletHub reported.

For 2018, the company compared the states and D.C. “across 40 measures of cost, accessibility and outcome,” which is five more measures than last year and a possible explanation for the changes at the top. The cost dimension’s five metrics included cost of medical visits and share of high out-of-pocket medical spending. The accessibility dimension consisted of 21 metrics, including average emergency department wait time and share of insured children. The outcomes dimension included 14 metrics, among them maternal mortality rate and share of adults with type 2 diabetes.

Vermont did well in both the outcomes (first) and cost (third) dimensions but only middle of the pack (23rd) in access. The District of Columbia was ranked first in cost and Maine was the leader in access. The lowest-ranked states in each category were Alaska (cost), Texas (access), and Mississippi (outcomes), according to the WalletHub analysis, which was based on data from such sources as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the United Health Foundation.

In the wild world of health care rankings, a year can make a big difference … or not.

Iowa fell from second to ninth over the course of the last year while Connecticut and South Dakota moved out of the top 10 to make way for Colorado and Maryland, according to WalletHub.

There was less movement at the other end of the rankings, however, with no change at all in the bottom five: Louisiana finished 51st again (the rankings include the District of Columbia), preceded by fellow repeaters Mississippi (50), Alaska (49), Arkansas (48), and North Carolina (47). Texas and Nevada did manage to move on up out of the bottom 11 – to 38th and 40th, respectively – at the expense of Oklahoma and Tennessee, WalletHub reported.

For 2018, the company compared the states and D.C. “across 40 measures of cost, accessibility and outcome,” which is five more measures than last year and a possible explanation for the changes at the top. The cost dimension’s five metrics included cost of medical visits and share of high out-of-pocket medical spending. The accessibility dimension consisted of 21 metrics, including average emergency department wait time and share of insured children. The outcomes dimension included 14 metrics, among them maternal mortality rate and share of adults with type 2 diabetes.

Vermont did well in both the outcomes (first) and cost (third) dimensions but only middle of the pack (23rd) in access. The District of Columbia was ranked first in cost and Maine was the leader in access. The lowest-ranked states in each category were Alaska (cost), Texas (access), and Mississippi (outcomes), according to the WalletHub analysis, which was based on data from such sources as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the United Health Foundation.

Documentation and billing: Tips for hospitalists

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

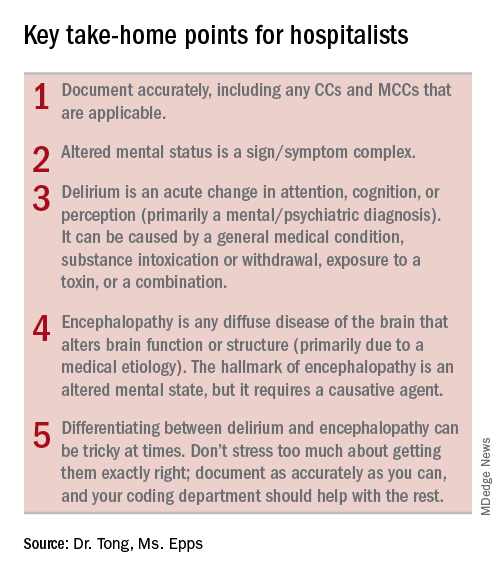

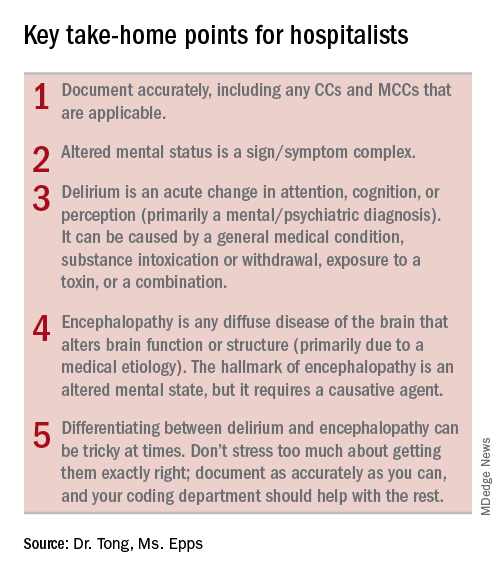

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

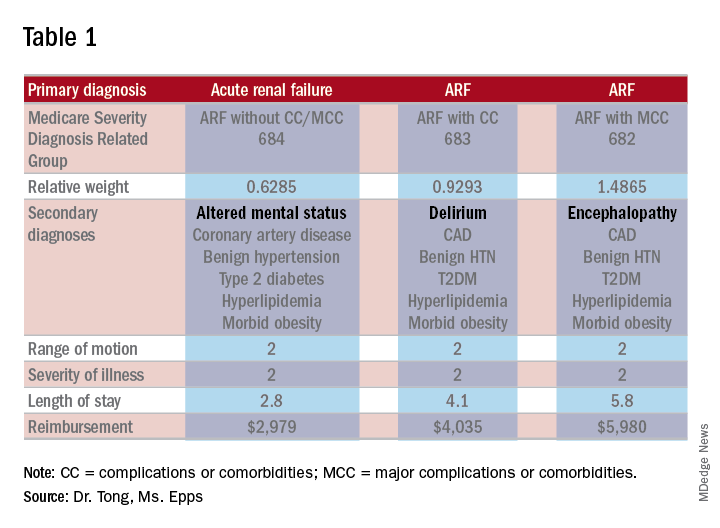

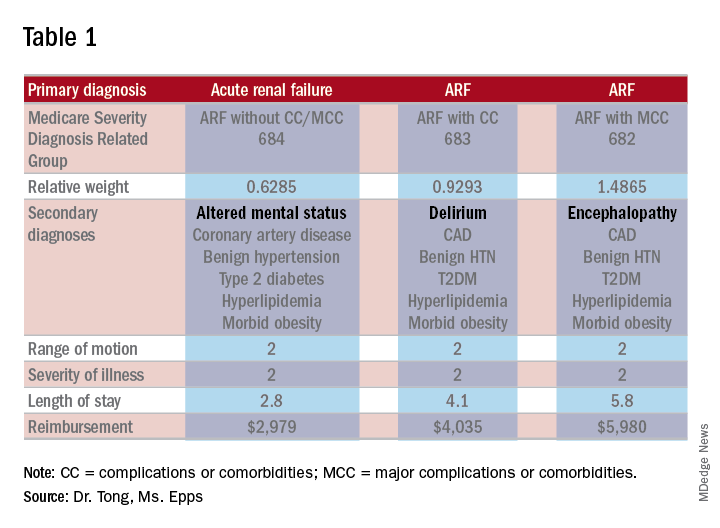

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

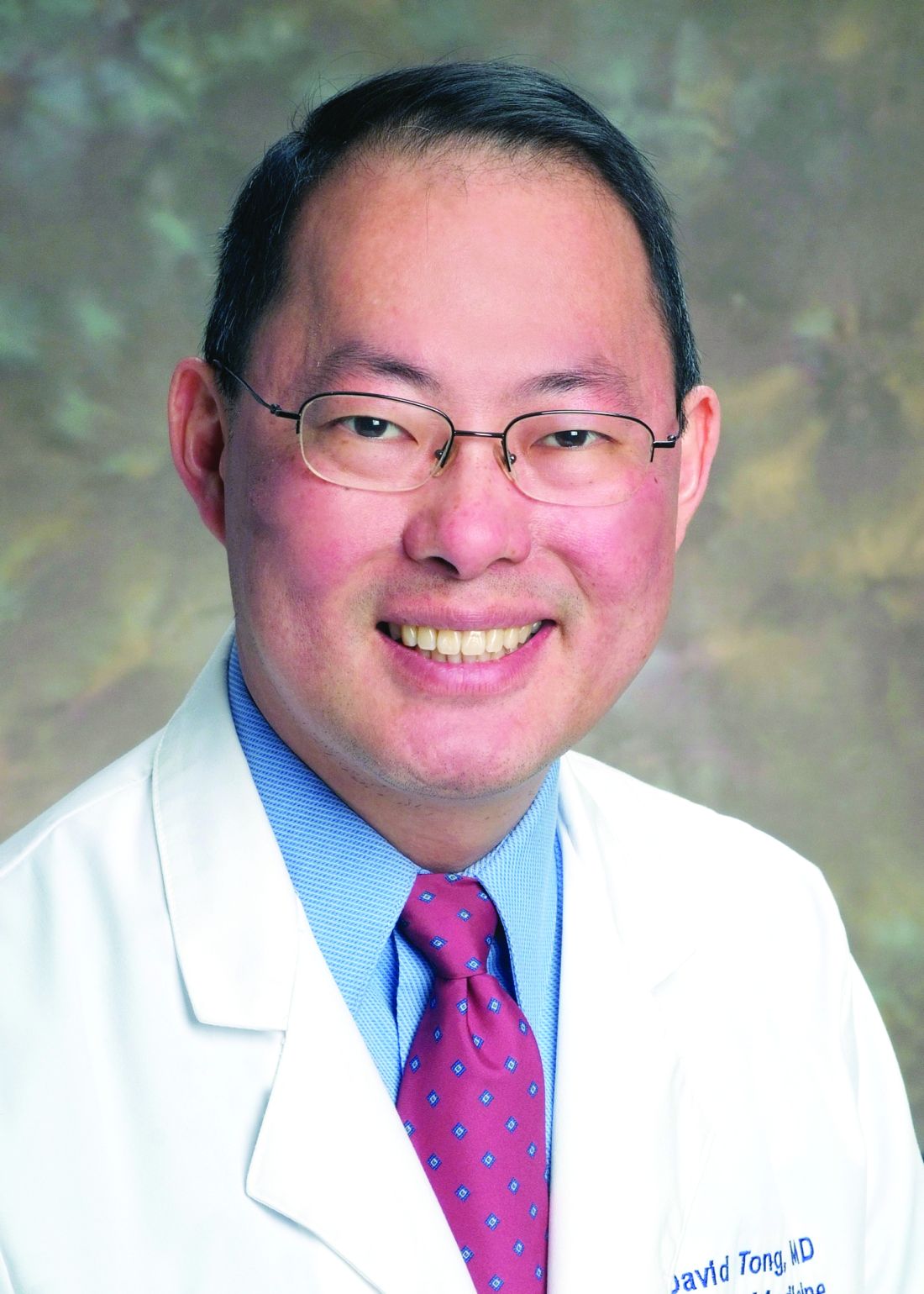

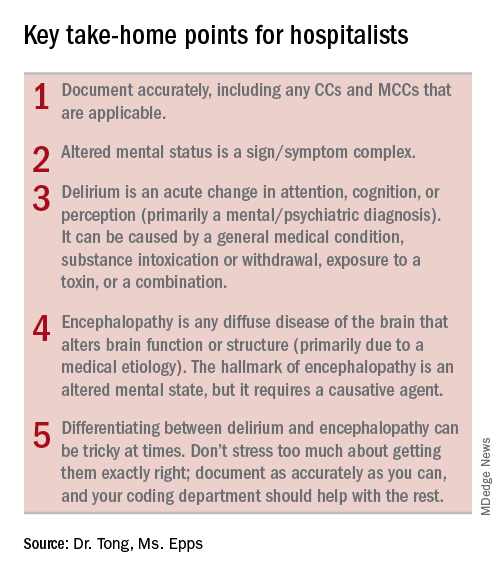

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

Who are the 'high-need, high-cost' patients?

Among patients hospitalized with gastrointestinal and liver diseases, a clearly identifiable subset uses significantly more health care resources, which incurs significantly greater costs, according to the results of a national database analysis published in the August issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Compared with otherwise similar inpatients, these “high-need, high-cost” individuals are significantly more likely to be enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid, to have lower income, to initially be admitted to a large, rural hospital, to have multiple comorbidities, to be obese, or to be hospitalized for infection, said Nghia Nguyen, MD, and his associates. “[A] small fraction of high-need, high-cost patients contribute disproportionately to hospitalization costs,” they wrote. “Population health management directed toward these patients would facilitate high-value care.”

Gastrointestinal and liver diseases incur more than $100 billion in health care expenses annually in the United States, of which more than 60% is related to inpatient care, the researchers noted. However, few studies have comprehensively evaluated the annual burden and costs of hospitalization in patients with chronic gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Therefore, using the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the investigators studied patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), chronic liver disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or pancreatic diseases who were hospitalized at least once during the first 6 months of 2013. All patients were diagnosed with IBD, chronic liver diseases, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or pancreatic diseases and followed for at least 6 months. The researchers stratified hospital days and costs and characterized the subset of patients who fell into the highest decile of days spent in the hospital per month.

The most common reason for hospitalization was chronic liver disease (nearly 377,000 patients), followed by functional gastrointestinal disorders (more than 351,000 patients), gastrointestinal hemorrhage (nearly 191,000 patients), pancreatic diseases (more than 98,000 patients), and IBD (more than 47,000 patients). Patients spent a median of 6-7 days in the hospital per year, with an interquartile range of 3-14 days. Compared with patients in the lowest decile for annual hospital stay (median, 0.13-0.14 days per month), patients in the highest decile spent a median of 3.7-5.1 days in the hospital per month. In this high-cost, high-need subset of patients, the costs of each hospitalization ranged from $7,438 per month to $11,425 per month, and they were typically hospitalized once every 2 months.

“Gastrointestinal diseases, infections, and cardiopulmonary causes were leading reasons for hospitalization of these patients,” the researchers wrote. “At a patient level, modifiable risk factors may include tackling the obesity epidemic and mental health issues and minimizing risk of iatrogenic or health care–associated infections, whereas at a health system level, interventions may include better access to care and connectivity between rural and specialty hospitals.”

Funders included the American College of Gastroenterology, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. Senior author Siddharth Singh disclosed unrelated grant funding from Pifzer and AbbVie. The other investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nguyen NH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.015.

Understanding the reasons underlying variations in health care utilization is central to any plan to reduce costs at the population level. To this end, Nguyen et al. provide crucial data for the patients for whom we care as gastroenterologists. Studying a longitudinal database of hospitalizations in 2013, the authors provide comprehensive demographic data for the top decile of inpatient health care utilizers (defined by hospital-days/month) with inflammatory bowel disease, chronic liver disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and pancreatic diseases. Although constrained by the limits of administrative data and the lack of outpatient/pharmaceutical data linkage, these findings are strengthened by their consistency across conditions. Indeed, despite the heterogeneous disorders surveyed, a remarkably consistent high-need/high-cost "phenotype" emerges: publicly insured, low-income, rural, obese but malnourished, and beset by infections and the complications of diabetes.

What are the next steps?

When a minority of the patients are responsible for a substantial portion of the costs (i.e., the 80/20 rule), one strategy for cost containment is "hot-spotting." Hot-spotting is a two-step process: Identify high-need, high-cost patients, and then deploy interventions tailored to their needs. Nguyen and colleague's work is a landmark for the first step. However, before these findings may be translated into policy or intervention, we need granular data to explain these associations and suggest clear action items. Solutions will likely be multifactorial including early, intensified care for obesity and diabetes (before end-stage complications arise), novel care delivery methods for gastroenterology specialty care in rural hospitals, and intensified outpatient resources for high-need patients in order to coordinate alternatives to hospitalization.

Elliot B. Tapper, MD, is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He reports consulting for Novartis and receiving unrestricted research grants from Valeant and Gilead, all unrelated to this work.

Understanding the reasons underlying variations in health care utilization is central to any plan to reduce costs at the population level. To this end, Nguyen et al. provide crucial data for the patients for whom we care as gastroenterologists. Studying a longitudinal database of hospitalizations in 2013, the authors provide comprehensive demographic data for the top decile of inpatient health care utilizers (defined by hospital-days/month) with inflammatory bowel disease, chronic liver disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and pancreatic diseases. Although constrained by the limits of administrative data and the lack of outpatient/pharmaceutical data linkage, these findings are strengthened by their consistency across conditions. Indeed, despite the heterogeneous disorders surveyed, a remarkably consistent high-need/high-cost "phenotype" emerges: publicly insured, low-income, rural, obese but malnourished, and beset by infections and the complications of diabetes.

What are the next steps?

When a minority of the patients are responsible for a substantial portion of the costs (i.e., the 80/20 rule), one strategy for cost containment is "hot-spotting." Hot-spotting is a two-step process: Identify high-need, high-cost patients, and then deploy interventions tailored to their needs. Nguyen and colleague's work is a landmark for the first step. However, before these findings may be translated into policy or intervention, we need granular data to explain these associations and suggest clear action items. Solutions will likely be multifactorial including early, intensified care for obesity and diabetes (before end-stage complications arise), novel care delivery methods for gastroenterology specialty care in rural hospitals, and intensified outpatient resources for high-need patients in order to coordinate alternatives to hospitalization.

Elliot B. Tapper, MD, is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He reports consulting for Novartis and receiving unrestricted research grants from Valeant and Gilead, all unrelated to this work.

Understanding the reasons underlying variations in health care utilization is central to any plan to reduce costs at the population level. To this end, Nguyen et al. provide crucial data for the patients for whom we care as gastroenterologists. Studying a longitudinal database of hospitalizations in 2013, the authors provide comprehensive demographic data for the top decile of inpatient health care utilizers (defined by hospital-days/month) with inflammatory bowel disease, chronic liver disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and pancreatic diseases. Although constrained by the limits of administrative data and the lack of outpatient/pharmaceutical data linkage, these findings are strengthened by their consistency across conditions. Indeed, despite the heterogeneous disorders surveyed, a remarkably consistent high-need/high-cost "phenotype" emerges: publicly insured, low-income, rural, obese but malnourished, and beset by infections and the complications of diabetes.

What are the next steps?

When a minority of the patients are responsible for a substantial portion of the costs (i.e., the 80/20 rule), one strategy for cost containment is "hot-spotting." Hot-spotting is a two-step process: Identify high-need, high-cost patients, and then deploy interventions tailored to their needs. Nguyen and colleague's work is a landmark for the first step. However, before these findings may be translated into policy or intervention, we need granular data to explain these associations and suggest clear action items. Solutions will likely be multifactorial including early, intensified care for obesity and diabetes (before end-stage complications arise), novel care delivery methods for gastroenterology specialty care in rural hospitals, and intensified outpatient resources for high-need patients in order to coordinate alternatives to hospitalization.

Elliot B. Tapper, MD, is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He reports consulting for Novartis and receiving unrestricted research grants from Valeant and Gilead, all unrelated to this work.

Among patients hospitalized with gastrointestinal and liver diseases, a clearly identifiable subset uses significantly more health care resources, which incurs significantly greater costs, according to the results of a national database analysis published in the August issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Compared with otherwise similar inpatients, these “high-need, high-cost” individuals are significantly more likely to be enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid, to have lower income, to initially be admitted to a large, rural hospital, to have multiple comorbidities, to be obese, or to be hospitalized for infection, said Nghia Nguyen, MD, and his associates. “[A] small fraction of high-need, high-cost patients contribute disproportionately to hospitalization costs,” they wrote. “Population health management directed toward these patients would facilitate high-value care.”

Gastrointestinal and liver diseases incur more than $100 billion in health care expenses annually in the United States, of which more than 60% is related to inpatient care, the researchers noted. However, few studies have comprehensively evaluated the annual burden and costs of hospitalization in patients with chronic gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Therefore, using the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the investigators studied patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), chronic liver disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or pancreatic diseases who were hospitalized at least once during the first 6 months of 2013. All patients were diagnosed with IBD, chronic liver diseases, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or pancreatic diseases and followed for at least 6 months. The researchers stratified hospital days and costs and characterized the subset of patients who fell into the highest decile of days spent in the hospital per month.

The most common reason for hospitalization was chronic liver disease (nearly 377,000 patients), followed by functional gastrointestinal disorders (more than 351,000 patients), gastrointestinal hemorrhage (nearly 191,000 patients), pancreatic diseases (more than 98,000 patients), and IBD (more than 47,000 patients). Patients spent a median of 6-7 days in the hospital per year, with an interquartile range of 3-14 days. Compared with patients in the lowest decile for annual hospital stay (median, 0.13-0.14 days per month), patients in the highest decile spent a median of 3.7-5.1 days in the hospital per month. In this high-cost, high-need subset of patients, the costs of each hospitalization ranged from $7,438 per month to $11,425 per month, and they were typically hospitalized once every 2 months.

“Gastrointestinal diseases, infections, and cardiopulmonary causes were leading reasons for hospitalization of these patients,” the researchers wrote. “At a patient level, modifiable risk factors may include tackling the obesity epidemic and mental health issues and minimizing risk of iatrogenic or health care–associated infections, whereas at a health system level, interventions may include better access to care and connectivity between rural and specialty hospitals.”

Funders included the American College of Gastroenterology, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. Senior author Siddharth Singh disclosed unrelated grant funding from Pifzer and AbbVie. The other investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nguyen NH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.015.

Among patients hospitalized with gastrointestinal and liver diseases, a clearly identifiable subset uses significantly more health care resources, which incurs significantly greater costs, according to the results of a national database analysis published in the August issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Compared with otherwise similar inpatients, these “high-need, high-cost” individuals are significantly more likely to be enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid, to have lower income, to initially be admitted to a large, rural hospital, to have multiple comorbidities, to be obese, or to be hospitalized for infection, said Nghia Nguyen, MD, and his associates. “[A] small fraction of high-need, high-cost patients contribute disproportionately to hospitalization costs,” they wrote. “Population health management directed toward these patients would facilitate high-value care.”

Gastrointestinal and liver diseases incur more than $100 billion in health care expenses annually in the United States, of which more than 60% is related to inpatient care, the researchers noted. However, few studies have comprehensively evaluated the annual burden and costs of hospitalization in patients with chronic gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Therefore, using the Nationwide Readmissions Database, the investigators studied patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), chronic liver disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or pancreatic diseases who were hospitalized at least once during the first 6 months of 2013. All patients were diagnosed with IBD, chronic liver diseases, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or pancreatic diseases and followed for at least 6 months. The researchers stratified hospital days and costs and characterized the subset of patients who fell into the highest decile of days spent in the hospital per month.

The most common reason for hospitalization was chronic liver disease (nearly 377,000 patients), followed by functional gastrointestinal disorders (more than 351,000 patients), gastrointestinal hemorrhage (nearly 191,000 patients), pancreatic diseases (more than 98,000 patients), and IBD (more than 47,000 patients). Patients spent a median of 6-7 days in the hospital per year, with an interquartile range of 3-14 days. Compared with patients in the lowest decile for annual hospital stay (median, 0.13-0.14 days per month), patients in the highest decile spent a median of 3.7-5.1 days in the hospital per month. In this high-cost, high-need subset of patients, the costs of each hospitalization ranged from $7,438 per month to $11,425 per month, and they were typically hospitalized once every 2 months.

“Gastrointestinal diseases, infections, and cardiopulmonary causes were leading reasons for hospitalization of these patients,” the researchers wrote. “At a patient level, modifiable risk factors may include tackling the obesity epidemic and mental health issues and minimizing risk of iatrogenic or health care–associated infections, whereas at a health system level, interventions may include better access to care and connectivity between rural and specialty hospitals.”

Funders included the American College of Gastroenterology, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. Senior author Siddharth Singh disclosed unrelated grant funding from Pifzer and AbbVie. The other investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nguyen NH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.015.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: For patients with gastrointestinal or liver disease, significant predictors of high need and cost during hospitalization included Medicare or Medicaid insurance, lower income, first hospitalization in a large rural hospital, high comorbidity burden, obesity, and hospitalization for infection.

Major finding: Patients in the highest decile spent a median of 3.7-4.1 days in the hospital per month for all causes. Gastrointestinal disease, infections, and cardiopulmonary morbidity were the most common reasons for hospitalization.

Study details: Analysis of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, chronic liver disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or pancreatic diseases hospitalized at least once during 2013.

Disclosures: Funders included the American College of Gastroenterology, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. Senior author Siddharth Singh disclosed unrelated grant funding from Pifzer and AbbVie. The other investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Nguyen NH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.015.

CMS proposes site-neutral payments for hospital outpatient setting

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) for 2019, released July 27 and scheduled to be published July 31 in the Federal Register, the CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under the OPPS.

“The clinic visit is the most common service billed under the OPPS and is often furnished in the physician office setting,” the CMS said in a fact sheet detailing its proposal.

According to the CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by the CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

However, Farzad Mostashari, MD, founder of the health care technology company Aledade and National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama, suggested that this could actually be a good thing for hospitals.

“The truth is that this proposal could help hospitals be more competitive in value-based contracts/alternative-payment models, and they should embrace the changes,” he said in a tweet.

The OPPS update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ambulatory surgical center, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

The CMS also will review all procedures added to the covered procedure list in the past 3 years to determine whether such procedures should continue to be covered.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

The CMS also is seeking information about relaunching a revamped competitive acquisition program that would have private vendors administer payment arrangements for Part B drugs. The agency is soliciting feedback on ways to design a model for testing.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) for 2019, released July 27 and scheduled to be published July 31 in the Federal Register, the CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under the OPPS.

“The clinic visit is the most common service billed under the OPPS and is often furnished in the physician office setting,” the CMS said in a fact sheet detailing its proposal.

According to the CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by the CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

However, Farzad Mostashari, MD, founder of the health care technology company Aledade and National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama, suggested that this could actually be a good thing for hospitals.

“The truth is that this proposal could help hospitals be more competitive in value-based contracts/alternative-payment models, and they should embrace the changes,” he said in a tweet.

The OPPS update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ambulatory surgical center, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

The CMS also will review all procedures added to the covered procedure list in the past 3 years to determine whether such procedures should continue to be covered.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

The CMS also is seeking information about relaunching a revamped competitive acquisition program that would have private vendors administer payment arrangements for Part B drugs. The agency is soliciting feedback on ways to design a model for testing.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

In the proposed update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) for 2019, released July 27 and scheduled to be published July 31 in the Federal Register, the CMS is proposing to apply a physician fee schedule–equivalent for the clinic visit service when provided at an off-campus, provider-based department that is paid under the OPPS.

“The clinic visit is the most common service billed under the OPPS and is often furnished in the physician office setting,” the CMS said in a fact sheet detailing its proposal.

According to the CMS, the average current clinical visit paid by the CMS is $116 with $23 being the average copay by the patient. If the proposal is finalized, the payment would drop to about $46 with an average patient copay of $9.

“This is intended to address concerns about recent consolidations in the market that reduce competition,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 25 press conference.

The American Hospital Association already is pushing back on this proposal.

“With today’s proposed rule, CMS has once again showed a lack of understanding about the reality in which hospitals and health systems operate daily to serve the needs of their communities,” AHA Executive Vice President Tom Nickels said in a statement. “In 2015, Congress clearly intended to provide current off-campus hospital clinics with the existing outpatient payment rate in recognition of the critical role they play in their communities. But CMS’s proposal runs counter to this and will instead impede access to care for the most vulnerable patients.”

However, Farzad Mostashari, MD, founder of the health care technology company Aledade and National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama, suggested that this could actually be a good thing for hospitals.

“The truth is that this proposal could help hospitals be more competitive in value-based contracts/alternative-payment models, and they should embrace the changes,” he said in a tweet.

The OPPS update also includes proposals to expand the list of covered surgical procedures that can be performed in an ambulatory surgical center, a move that Ms. Verma said would “provide patients with more choices and options for lower-priced care.”

“For CY 2019, CMS is proposing to allow certain CPT codes outside of the surgical code range that directly crosswalk or are clinically similar to procedures within the CPT surgical code range to be included on the [covered procedure list] and is proposing to add certain cardiovascular codes to the ASC [covered procedure list] as a result,” the CMS fact sheet notes.

The CMS also will review all procedures added to the covered procedure list in the past 3 years to determine whether such procedures should continue to be covered.

In addition, the OPPS is seeking feedback on a number of topics.

One is related to price transparency. The agency is asking “whether providers and suppliers can and should be required to inform patients about charges and payment information for healthcare services and out-of-pocket costs, what data elements the public would find most useful, and what other charges are needed to empower patients,” according to the fact sheet.

The CMS also is seeking information about relaunching a revamped competitive acquisition program that would have private vendors administer payment arrangements for Part B drugs. The agency is soliciting feedback on ways to design a model for testing.

Finally, the agency is seeking more information on solutions to better promote interoperability.

CMS considers expanding telemedicine payments

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.

“The needle is finally moving, albeit too slowly for some of us,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “There are still some areas users of telemedicine and organizations supporting the use of telemedicine want to address, including the need for verbal informed consent, the requirements for established relationships with patients, and of course, rate valuations for the remote patient monitoring and professional codes. But again, this is good news for patients.”

Public comments on the proposed rule are due by Sept. 10, 2018. Comments can be submitted to regulations.gov.

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.