User login

The Hospitalist only

Reviving rural health care

Hospitalists have an important role to play

Health care in the United States has seen tremendous change in the last 2-3 decades, stemming from a dramatic push to contain spending, a call to action to improve quality and safety, and a boom in technology and medical advancement.

While the specialty of hospital medicine in the United States matured in response to these calls to action, it mostly flourished amidst – and as a result of – market consolidation, cost containment, the rise in the underinsured, and the flight of primary care from hospitals.

Changes in the health care industry have paralleled other parts of our society. Health care organizations, like schools, churches, theaters, parks, and sports teams, are part of the social fabric of communities. They provide stability to communities as employers, educators, social supporters, and the provision of services. It is no wonder then, that smaller communities, rural areas in particular, flourish or wither when one or more of these institutions, especially health care, fail them.

Health disparities result from any number of factors but particularly when communities are destabilized. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has studied this across the United States. For example, in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn., where I live, life expectancy varies by over 10 years along the interstate highway that runs through the metro area. Similarly, this disparity is seen between urban and rural Kentucky.

To be sure, the confounding social determinants of health and the mitigating strategies for the communities are different in urban Minneapolis than in Wolfe County, Kentucky. However, much of the work around health care reform (and therefore, hospital medicine) has centered around urban populations such as Minneapolis rather than rural populations such as Wolfe County. While 80% of the U.S. population lives in urban centers, that still means that 1 in 5 people live in rural America – spread across 97% of the U.S. land mass. These rural populations are exceedingly diverse, and warrant exceedingly diverse solutions.

Eighteen years ago, when I started my career in hospital medicine, I would never have thought I would be a spokesman for rural care. I identified as an urban academic hospitalist at a safety net hospital known for serving the urban poor and diverse refugee populations. But I had not anticipated mergers involving urban and rural hospitals, nor our resulting responsibility for staffing several critical access hospitals in another state.

It was hard in the beginning to recruit hospitalists to rural areas, so I worked in those areas myself, and experienced the rich practice in nonurban centers. As our partners also joined in our efforts to staff these hospitals, they had similar experiences. Now we can’t keep physicians away. That is not to say that the challenges are over.

Since 2010, 26 states lost rural hospitals – over 80 hospitals in total. High premiums in the individual health insurance market have driven healthy people out of risk pools, pushed payers out of the market, driving premiums higher still, resulting in coverage deserts. Consolidation and alignment with urban and national health care organizations initially brought hope to cash-strapped rural hospitals. Instead of improving local access, however, referrals to urban centers drained rural hospitals of their sources of income.

Economic instability has further destabilized communities. Rural America is exceptionally diverse, and has higher rates of poverty and the working poor, a shrinking job market that still hasn’t recovered from the 2008 recession, and higher rates of disability when compared to urban America. Do I even need to mention the rural opioid epidemic? Or the rural physician crisis, with a dwindling 12% of primary care and 8% of specialty care in these communities?

There is hope. During a late-night text conversation with a millennial nocturnist who splits his time between large and small hospitals, I received this message at 11:42 p.m.: “I think I feel more appreciated/valued/respected out here. You know how it is at the smaller hospitals.”

This was a comment the young hospitalist made after he shared with me that, lately, he had been in a “funk.” Innovations such as telemedicine have brought balance to overworked rural family doctors and excitement to young, tech savvy hospitalists. Opportunities to educate rural nurses and increase the level of care, keeping patients local, have excited academic hospitalists and rural CFOs alike. For a physician in a high burnout specialty, a long peaceful drive through the country might be just what’s needed to encourage a few moments of mindfulness.

Many of our urban health systems have combined with rural ones. It’s time to embrace it. Ignoring the health disparities in rural America divides us and diminishes essential parts of our health care system. Calling the hospitals our patients are referred from “OSH” (Outside Hospitals) will only perpetuate that.

Hospitalists have an opportunity to play an important role in stabilizing rural communities, reviving rural health systems, and providing local access to health care. Let’s embrace this opportunity to make a lasting impact on this frontier in hospital medicine.

Dr. Siy is chair of the department of hospital medicine at HealthPartners in Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn., and a member of the SHM board of directors.

Hospitalists have an important role to play

Hospitalists have an important role to play

Health care in the United States has seen tremendous change in the last 2-3 decades, stemming from a dramatic push to contain spending, a call to action to improve quality and safety, and a boom in technology and medical advancement.

While the specialty of hospital medicine in the United States matured in response to these calls to action, it mostly flourished amidst – and as a result of – market consolidation, cost containment, the rise in the underinsured, and the flight of primary care from hospitals.

Changes in the health care industry have paralleled other parts of our society. Health care organizations, like schools, churches, theaters, parks, and sports teams, are part of the social fabric of communities. They provide stability to communities as employers, educators, social supporters, and the provision of services. It is no wonder then, that smaller communities, rural areas in particular, flourish or wither when one or more of these institutions, especially health care, fail them.

Health disparities result from any number of factors but particularly when communities are destabilized. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has studied this across the United States. For example, in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn., where I live, life expectancy varies by over 10 years along the interstate highway that runs through the metro area. Similarly, this disparity is seen between urban and rural Kentucky.

To be sure, the confounding social determinants of health and the mitigating strategies for the communities are different in urban Minneapolis than in Wolfe County, Kentucky. However, much of the work around health care reform (and therefore, hospital medicine) has centered around urban populations such as Minneapolis rather than rural populations such as Wolfe County. While 80% of the U.S. population lives in urban centers, that still means that 1 in 5 people live in rural America – spread across 97% of the U.S. land mass. These rural populations are exceedingly diverse, and warrant exceedingly diverse solutions.

Eighteen years ago, when I started my career in hospital medicine, I would never have thought I would be a spokesman for rural care. I identified as an urban academic hospitalist at a safety net hospital known for serving the urban poor and diverse refugee populations. But I had not anticipated mergers involving urban and rural hospitals, nor our resulting responsibility for staffing several critical access hospitals in another state.

It was hard in the beginning to recruit hospitalists to rural areas, so I worked in those areas myself, and experienced the rich practice in nonurban centers. As our partners also joined in our efforts to staff these hospitals, they had similar experiences. Now we can’t keep physicians away. That is not to say that the challenges are over.

Since 2010, 26 states lost rural hospitals – over 80 hospitals in total. High premiums in the individual health insurance market have driven healthy people out of risk pools, pushed payers out of the market, driving premiums higher still, resulting in coverage deserts. Consolidation and alignment with urban and national health care organizations initially brought hope to cash-strapped rural hospitals. Instead of improving local access, however, referrals to urban centers drained rural hospitals of their sources of income.

Economic instability has further destabilized communities. Rural America is exceptionally diverse, and has higher rates of poverty and the working poor, a shrinking job market that still hasn’t recovered from the 2008 recession, and higher rates of disability when compared to urban America. Do I even need to mention the rural opioid epidemic? Or the rural physician crisis, with a dwindling 12% of primary care and 8% of specialty care in these communities?

There is hope. During a late-night text conversation with a millennial nocturnist who splits his time between large and small hospitals, I received this message at 11:42 p.m.: “I think I feel more appreciated/valued/respected out here. You know how it is at the smaller hospitals.”

This was a comment the young hospitalist made after he shared with me that, lately, he had been in a “funk.” Innovations such as telemedicine have brought balance to overworked rural family doctors and excitement to young, tech savvy hospitalists. Opportunities to educate rural nurses and increase the level of care, keeping patients local, have excited academic hospitalists and rural CFOs alike. For a physician in a high burnout specialty, a long peaceful drive through the country might be just what’s needed to encourage a few moments of mindfulness.

Many of our urban health systems have combined with rural ones. It’s time to embrace it. Ignoring the health disparities in rural America divides us and diminishes essential parts of our health care system. Calling the hospitals our patients are referred from “OSH” (Outside Hospitals) will only perpetuate that.

Hospitalists have an opportunity to play an important role in stabilizing rural communities, reviving rural health systems, and providing local access to health care. Let’s embrace this opportunity to make a lasting impact on this frontier in hospital medicine.

Dr. Siy is chair of the department of hospital medicine at HealthPartners in Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn., and a member of the SHM board of directors.

Health care in the United States has seen tremendous change in the last 2-3 decades, stemming from a dramatic push to contain spending, a call to action to improve quality and safety, and a boom in technology and medical advancement.

While the specialty of hospital medicine in the United States matured in response to these calls to action, it mostly flourished amidst – and as a result of – market consolidation, cost containment, the rise in the underinsured, and the flight of primary care from hospitals.

Changes in the health care industry have paralleled other parts of our society. Health care organizations, like schools, churches, theaters, parks, and sports teams, are part of the social fabric of communities. They provide stability to communities as employers, educators, social supporters, and the provision of services. It is no wonder then, that smaller communities, rural areas in particular, flourish or wither when one or more of these institutions, especially health care, fail them.

Health disparities result from any number of factors but particularly when communities are destabilized. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has studied this across the United States. For example, in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn., where I live, life expectancy varies by over 10 years along the interstate highway that runs through the metro area. Similarly, this disparity is seen between urban and rural Kentucky.

To be sure, the confounding social determinants of health and the mitigating strategies for the communities are different in urban Minneapolis than in Wolfe County, Kentucky. However, much of the work around health care reform (and therefore, hospital medicine) has centered around urban populations such as Minneapolis rather than rural populations such as Wolfe County. While 80% of the U.S. population lives in urban centers, that still means that 1 in 5 people live in rural America – spread across 97% of the U.S. land mass. These rural populations are exceedingly diverse, and warrant exceedingly diverse solutions.

Eighteen years ago, when I started my career in hospital medicine, I would never have thought I would be a spokesman for rural care. I identified as an urban academic hospitalist at a safety net hospital known for serving the urban poor and diverse refugee populations. But I had not anticipated mergers involving urban and rural hospitals, nor our resulting responsibility for staffing several critical access hospitals in another state.

It was hard in the beginning to recruit hospitalists to rural areas, so I worked in those areas myself, and experienced the rich practice in nonurban centers. As our partners also joined in our efforts to staff these hospitals, they had similar experiences. Now we can’t keep physicians away. That is not to say that the challenges are over.

Since 2010, 26 states lost rural hospitals – over 80 hospitals in total. High premiums in the individual health insurance market have driven healthy people out of risk pools, pushed payers out of the market, driving premiums higher still, resulting in coverage deserts. Consolidation and alignment with urban and national health care organizations initially brought hope to cash-strapped rural hospitals. Instead of improving local access, however, referrals to urban centers drained rural hospitals of their sources of income.

Economic instability has further destabilized communities. Rural America is exceptionally diverse, and has higher rates of poverty and the working poor, a shrinking job market that still hasn’t recovered from the 2008 recession, and higher rates of disability when compared to urban America. Do I even need to mention the rural opioid epidemic? Or the rural physician crisis, with a dwindling 12% of primary care and 8% of specialty care in these communities?

There is hope. During a late-night text conversation with a millennial nocturnist who splits his time between large and small hospitals, I received this message at 11:42 p.m.: “I think I feel more appreciated/valued/respected out here. You know how it is at the smaller hospitals.”

This was a comment the young hospitalist made after he shared with me that, lately, he had been in a “funk.” Innovations such as telemedicine have brought balance to overworked rural family doctors and excitement to young, tech savvy hospitalists. Opportunities to educate rural nurses and increase the level of care, keeping patients local, have excited academic hospitalists and rural CFOs alike. For a physician in a high burnout specialty, a long peaceful drive through the country might be just what’s needed to encourage a few moments of mindfulness.

Many of our urban health systems have combined with rural ones. It’s time to embrace it. Ignoring the health disparities in rural America divides us and diminishes essential parts of our health care system. Calling the hospitals our patients are referred from “OSH” (Outside Hospitals) will only perpetuate that.

Hospitalists have an opportunity to play an important role in stabilizing rural communities, reviving rural health systems, and providing local access to health care. Let’s embrace this opportunity to make a lasting impact on this frontier in hospital medicine.

Dr. Siy is chair of the department of hospital medicine at HealthPartners in Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minn., and a member of the SHM board of directors.

Trump, not health care, likely focus of midterm elections

Provider community must be “creative and participative”

Come November 2018, Americans will return to the polls to vote for their representatives in Congress, for governors, and for state legislative seats.

Health care has been a topic of debate since the 2016 elections brought a Republican sweep to the executive and legislative branches, but other issues have since moved to the forefront. Will the midterm elections this year prove health care to be a significant issue at the polls?

Unlikely, said Robert Berenson, MD, FACP, Institute Fellow of the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute. More likely, the election will be a referendum on President Donald Trump, he said. “Things are so partisan right now and it’s all about Trump. I don’t see serious discussion about health policy.”

Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, FCCP, immediate past president of SHM and former chair of the Public Policy Committee, also doesn’t see health care rising to the top of election year issues. But that doesn’t mean health care doesn’t matter to American voters.

“Whether Democrats control the House or Republicans control the House won’t likely make a big difference in terms of impact on the things we care about,” said Dr. Greeno. “The issues they debate in Washington are not going to save the health care system. They are just debating about who is going to pay for what and for whom. To save our health care system, we have to lower the cost of care and only providers can do that.”

What the government can do, he said, is create the right incentives for providers to move away from fee for service and participate in new models that may lower the cost of care. At the same time, “the economy also has to grow at a robust pace, which will make a huge difference. So, recent increases in economic growth rate are welcomed,” said Dr. Greeno.

In 2015, Republicans and Democrats came together to pass bipartisan legislation aimed at moving the health care system away from fee for service: the Medicare and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA.

However, the law has not been without frustrations, and these concerns will likely not be part of any candidate campaigns in 2018, Dr. Greeno predicted: “There’s not a lot of appetite to reopen the statute (more than) 2 years after it passed.”

MACRA provides clinicians two pathways to reimbursement. The first track, called MIPS (Merit-Based Incentive Payment System), bases a portion of physician reimbursement on scores measured across several categories, including cost and quality. It still operates largely under a fee-for-service framework but is meant to be budget neutral; for every winner there is a loser.

The second track, called the APMs (Alternative Payment Models), requires physicians to take on substantial risk (with potential for reward), if they can achieve specific patient volumes under approved models. However, few providers qualify, especially among hospitalists, though the structure of the program makes it clear that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services intends to have most providers ultimately transition to APMs.

“There’s growing recognition that MACRA, at least the MIPS portion, was a big mistake but Congress can’t go back and say we blew it,” Dr. Berenson said. “CMS has now exempted somewhere between 550,000 and 900,000 clinicians from MACRA,” because they cannot meet the requirements of either pathway without significant hardship.1

CMS wasn’t considering hospitalists specifically when implementing the law, though hospitalists admit half of the Medicare patients in the United States, Dr. Greeno said. There are very few hospitalists currently participating in Advanced APMs and those that are, do not see the volume of patients the pathway requires.

“What hospitalists do is very conducive to alternative payment models, and we can help those alternative payment models drive improved quality and lowered costs,” said Dr. Greeno. “Hospitals use hospitalists to help them manage risk, so it’s frustrating that most hospitalists will not meet the thresholds for the APM track and benefit from the incentives created.”

However, the Society of Hospital Medicine continues to work on behalf of hospitalists. Thanks to its efforts, Dr. Greeno explained, CMS is planning in 2019 to allow hospitalists to choose to be scored under MIPS based on their hospital’s performance across reporting categories. Or, they can choose to report on their own and opt out of this new “facility-based” option.

“We are working with (CMS) to figure out how to make this new option work,” said Dr. Greeno.

At the state level, 36 governorships are up for grabs and those outcomes could influence the direction of Medicaid. In Kentucky, the Trump administration approved a waiver allowing the state to enforce work requirements for Medicaid recipients. However, on June 29, 2018, the D.C. federal district court invalidated the Kentucky HEALTH waiver approval (with the exception of Kentucky’s IMD SUD [institutions for mental disease for substance use disorders] payment waiver authority) and sent it back to HHS to reconsider. Ten other states as of August 2018 had applied for similar waivers.2 However, Dr. Berenson believes that most of what could happen to Medicaid will be a topic after the midterm elections and not before.

He also believes drug prices could become an issue in national elections, though there will not be an easy solution from either side. “Democrats will be reluctant to say they’re going to negotiate drug prices; they’re going to want the government to negotiate for Medicare-like pricing.” Republicans, on the other hand, will be reluctant to consider government regulation.

As a general principle leading into the midterms: “Democrats want to avoid an internal war about whether they are for Medicare for all or single payer or not,” Dr. Berenson said. “What I’m hoping doesn’t happen is that it becomes a litmus test for purity where you have to be for single payer. I think would be huge mistake because it’s not realistic that it would ever get there.”

However, he cites an idea from left-leaning Princeton University’s Paul Starr, a professor of sociology and public affairs, that Democrats could consider: so-called Midlife Medicare, an option that could be made available to Americans beginning at age 50 years.3 It would represent a new Medicare option, funded by general revenues and premiums, available to people age 50 years and older and those younger than 65 years who are without employer-sponsored health insurance.

Regardless, as the United States catapults toward another election that could disrupt the political system or maintain the relative status quo, Dr. Greeno said hospitalists continue to play key roles in improving American health care.

“There are programs in place where we can get the job done if we in the provider community are creative and participative,” he said. “Some of the most important work being done is coming out of the CMS Innovation Center. Hospitalists continue to be a big part of that, but we knew it would take decades of really hard work and I don’t see anything happening in the midterms to derail this or bring about a massive increase in the pace of change.”

References

1. Dickson V. CMS gives more small practices a pass on MACRA. Modern Healthcare. Published June 20, 2017.

2. Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Which States Have Approved and Pending Section 1115 Medicaid Waivers? Kaiser Family Foundation. Published Aug. 8, 2018.

3. Starr P. A new strategy for health care. The American Prospect. Published Jan. 4, 2018. Accessed March 5, 2018.

Provider community must be “creative and participative”

Provider community must be “creative and participative”

Come November 2018, Americans will return to the polls to vote for their representatives in Congress, for governors, and for state legislative seats.

Health care has been a topic of debate since the 2016 elections brought a Republican sweep to the executive and legislative branches, but other issues have since moved to the forefront. Will the midterm elections this year prove health care to be a significant issue at the polls?

Unlikely, said Robert Berenson, MD, FACP, Institute Fellow of the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute. More likely, the election will be a referendum on President Donald Trump, he said. “Things are so partisan right now and it’s all about Trump. I don’t see serious discussion about health policy.”

Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, FCCP, immediate past president of SHM and former chair of the Public Policy Committee, also doesn’t see health care rising to the top of election year issues. But that doesn’t mean health care doesn’t matter to American voters.

“Whether Democrats control the House or Republicans control the House won’t likely make a big difference in terms of impact on the things we care about,” said Dr. Greeno. “The issues they debate in Washington are not going to save the health care system. They are just debating about who is going to pay for what and for whom. To save our health care system, we have to lower the cost of care and only providers can do that.”

What the government can do, he said, is create the right incentives for providers to move away from fee for service and participate in new models that may lower the cost of care. At the same time, “the economy also has to grow at a robust pace, which will make a huge difference. So, recent increases in economic growth rate are welcomed,” said Dr. Greeno.

In 2015, Republicans and Democrats came together to pass bipartisan legislation aimed at moving the health care system away from fee for service: the Medicare and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA.

However, the law has not been without frustrations, and these concerns will likely not be part of any candidate campaigns in 2018, Dr. Greeno predicted: “There’s not a lot of appetite to reopen the statute (more than) 2 years after it passed.”

MACRA provides clinicians two pathways to reimbursement. The first track, called MIPS (Merit-Based Incentive Payment System), bases a portion of physician reimbursement on scores measured across several categories, including cost and quality. It still operates largely under a fee-for-service framework but is meant to be budget neutral; for every winner there is a loser.

The second track, called the APMs (Alternative Payment Models), requires physicians to take on substantial risk (with potential for reward), if they can achieve specific patient volumes under approved models. However, few providers qualify, especially among hospitalists, though the structure of the program makes it clear that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services intends to have most providers ultimately transition to APMs.

“There’s growing recognition that MACRA, at least the MIPS portion, was a big mistake but Congress can’t go back and say we blew it,” Dr. Berenson said. “CMS has now exempted somewhere between 550,000 and 900,000 clinicians from MACRA,” because they cannot meet the requirements of either pathway without significant hardship.1

CMS wasn’t considering hospitalists specifically when implementing the law, though hospitalists admit half of the Medicare patients in the United States, Dr. Greeno said. There are very few hospitalists currently participating in Advanced APMs and those that are, do not see the volume of patients the pathway requires.

“What hospitalists do is very conducive to alternative payment models, and we can help those alternative payment models drive improved quality and lowered costs,” said Dr. Greeno. “Hospitals use hospitalists to help them manage risk, so it’s frustrating that most hospitalists will not meet the thresholds for the APM track and benefit from the incentives created.”

However, the Society of Hospital Medicine continues to work on behalf of hospitalists. Thanks to its efforts, Dr. Greeno explained, CMS is planning in 2019 to allow hospitalists to choose to be scored under MIPS based on their hospital’s performance across reporting categories. Or, they can choose to report on their own and opt out of this new “facility-based” option.

“We are working with (CMS) to figure out how to make this new option work,” said Dr. Greeno.

At the state level, 36 governorships are up for grabs and those outcomes could influence the direction of Medicaid. In Kentucky, the Trump administration approved a waiver allowing the state to enforce work requirements for Medicaid recipients. However, on June 29, 2018, the D.C. federal district court invalidated the Kentucky HEALTH waiver approval (with the exception of Kentucky’s IMD SUD [institutions for mental disease for substance use disorders] payment waiver authority) and sent it back to HHS to reconsider. Ten other states as of August 2018 had applied for similar waivers.2 However, Dr. Berenson believes that most of what could happen to Medicaid will be a topic after the midterm elections and not before.

He also believes drug prices could become an issue in national elections, though there will not be an easy solution from either side. “Democrats will be reluctant to say they’re going to negotiate drug prices; they’re going to want the government to negotiate for Medicare-like pricing.” Republicans, on the other hand, will be reluctant to consider government regulation.

As a general principle leading into the midterms: “Democrats want to avoid an internal war about whether they are for Medicare for all or single payer or not,” Dr. Berenson said. “What I’m hoping doesn’t happen is that it becomes a litmus test for purity where you have to be for single payer. I think would be huge mistake because it’s not realistic that it would ever get there.”

However, he cites an idea from left-leaning Princeton University’s Paul Starr, a professor of sociology and public affairs, that Democrats could consider: so-called Midlife Medicare, an option that could be made available to Americans beginning at age 50 years.3 It would represent a new Medicare option, funded by general revenues and premiums, available to people age 50 years and older and those younger than 65 years who are without employer-sponsored health insurance.

Regardless, as the United States catapults toward another election that could disrupt the political system or maintain the relative status quo, Dr. Greeno said hospitalists continue to play key roles in improving American health care.

“There are programs in place where we can get the job done if we in the provider community are creative and participative,” he said. “Some of the most important work being done is coming out of the CMS Innovation Center. Hospitalists continue to be a big part of that, but we knew it would take decades of really hard work and I don’t see anything happening in the midterms to derail this or bring about a massive increase in the pace of change.”

References

1. Dickson V. CMS gives more small practices a pass on MACRA. Modern Healthcare. Published June 20, 2017.

2. Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Which States Have Approved and Pending Section 1115 Medicaid Waivers? Kaiser Family Foundation. Published Aug. 8, 2018.

3. Starr P. A new strategy for health care. The American Prospect. Published Jan. 4, 2018. Accessed March 5, 2018.

Come November 2018, Americans will return to the polls to vote for their representatives in Congress, for governors, and for state legislative seats.

Health care has been a topic of debate since the 2016 elections brought a Republican sweep to the executive and legislative branches, but other issues have since moved to the forefront. Will the midterm elections this year prove health care to be a significant issue at the polls?

Unlikely, said Robert Berenson, MD, FACP, Institute Fellow of the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute. More likely, the election will be a referendum on President Donald Trump, he said. “Things are so partisan right now and it’s all about Trump. I don’t see serious discussion about health policy.”

Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, FCCP, immediate past president of SHM and former chair of the Public Policy Committee, also doesn’t see health care rising to the top of election year issues. But that doesn’t mean health care doesn’t matter to American voters.

“Whether Democrats control the House or Republicans control the House won’t likely make a big difference in terms of impact on the things we care about,” said Dr. Greeno. “The issues they debate in Washington are not going to save the health care system. They are just debating about who is going to pay for what and for whom. To save our health care system, we have to lower the cost of care and only providers can do that.”

What the government can do, he said, is create the right incentives for providers to move away from fee for service and participate in new models that may lower the cost of care. At the same time, “the economy also has to grow at a robust pace, which will make a huge difference. So, recent increases in economic growth rate are welcomed,” said Dr. Greeno.

In 2015, Republicans and Democrats came together to pass bipartisan legislation aimed at moving the health care system away from fee for service: the Medicare and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA.

However, the law has not been without frustrations, and these concerns will likely not be part of any candidate campaigns in 2018, Dr. Greeno predicted: “There’s not a lot of appetite to reopen the statute (more than) 2 years after it passed.”

MACRA provides clinicians two pathways to reimbursement. The first track, called MIPS (Merit-Based Incentive Payment System), bases a portion of physician reimbursement on scores measured across several categories, including cost and quality. It still operates largely under a fee-for-service framework but is meant to be budget neutral; for every winner there is a loser.

The second track, called the APMs (Alternative Payment Models), requires physicians to take on substantial risk (with potential for reward), if they can achieve specific patient volumes under approved models. However, few providers qualify, especially among hospitalists, though the structure of the program makes it clear that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services intends to have most providers ultimately transition to APMs.

“There’s growing recognition that MACRA, at least the MIPS portion, was a big mistake but Congress can’t go back and say we blew it,” Dr. Berenson said. “CMS has now exempted somewhere between 550,000 and 900,000 clinicians from MACRA,” because they cannot meet the requirements of either pathway without significant hardship.1

CMS wasn’t considering hospitalists specifically when implementing the law, though hospitalists admit half of the Medicare patients in the United States, Dr. Greeno said. There are very few hospitalists currently participating in Advanced APMs and those that are, do not see the volume of patients the pathway requires.

“What hospitalists do is very conducive to alternative payment models, and we can help those alternative payment models drive improved quality and lowered costs,” said Dr. Greeno. “Hospitals use hospitalists to help them manage risk, so it’s frustrating that most hospitalists will not meet the thresholds for the APM track and benefit from the incentives created.”

However, the Society of Hospital Medicine continues to work on behalf of hospitalists. Thanks to its efforts, Dr. Greeno explained, CMS is planning in 2019 to allow hospitalists to choose to be scored under MIPS based on their hospital’s performance across reporting categories. Or, they can choose to report on their own and opt out of this new “facility-based” option.

“We are working with (CMS) to figure out how to make this new option work,” said Dr. Greeno.

At the state level, 36 governorships are up for grabs and those outcomes could influence the direction of Medicaid. In Kentucky, the Trump administration approved a waiver allowing the state to enforce work requirements for Medicaid recipients. However, on June 29, 2018, the D.C. federal district court invalidated the Kentucky HEALTH waiver approval (with the exception of Kentucky’s IMD SUD [institutions for mental disease for substance use disorders] payment waiver authority) and sent it back to HHS to reconsider. Ten other states as of August 2018 had applied for similar waivers.2 However, Dr. Berenson believes that most of what could happen to Medicaid will be a topic after the midterm elections and not before.

He also believes drug prices could become an issue in national elections, though there will not be an easy solution from either side. “Democrats will be reluctant to say they’re going to negotiate drug prices; they’re going to want the government to negotiate for Medicare-like pricing.” Republicans, on the other hand, will be reluctant to consider government regulation.

As a general principle leading into the midterms: “Democrats want to avoid an internal war about whether they are for Medicare for all or single payer or not,” Dr. Berenson said. “What I’m hoping doesn’t happen is that it becomes a litmus test for purity where you have to be for single payer. I think would be huge mistake because it’s not realistic that it would ever get there.”

However, he cites an idea from left-leaning Princeton University’s Paul Starr, a professor of sociology and public affairs, that Democrats could consider: so-called Midlife Medicare, an option that could be made available to Americans beginning at age 50 years.3 It would represent a new Medicare option, funded by general revenues and premiums, available to people age 50 years and older and those younger than 65 years who are without employer-sponsored health insurance.

Regardless, as the United States catapults toward another election that could disrupt the political system or maintain the relative status quo, Dr. Greeno said hospitalists continue to play key roles in improving American health care.

“There are programs in place where we can get the job done if we in the provider community are creative and participative,” he said. “Some of the most important work being done is coming out of the CMS Innovation Center. Hospitalists continue to be a big part of that, but we knew it would take decades of really hard work and I don’t see anything happening in the midterms to derail this or bring about a massive increase in the pace of change.”

References

1. Dickson V. CMS gives more small practices a pass on MACRA. Modern Healthcare. Published June 20, 2017.

2. Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Which States Have Approved and Pending Section 1115 Medicaid Waivers? Kaiser Family Foundation. Published Aug. 8, 2018.

3. Starr P. A new strategy for health care. The American Prospect. Published Jan. 4, 2018. Accessed March 5, 2018.

White coats and provider attire: Does it matter to patients?

What is appropriate “ward garb”?

The question of appropriate ward garb is a problem for the ages. Compared with photo stills and films from the 1960s, the doctors of today appear like vagabonds. No ties, no lab coats, and scrub tops have become the norm for a number (a majority?) of hospital-based docs – and even more so on the surgical wards and in the ER.

Past studies have addressed patient preferences for provider dress, but none like the results of a recent survey.

From the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, comes a physician attire survey of a convenience sample of 4,000 patients at 10 U.S. academic medical centers. It included both inpatients and outpatients, and used the design of many previous studies, showing patients the same doctor dressed seven different ways. After viewing the photographs, the patients received surveys as to their preference of physician based on attire, as well as being asked to rate the physician in the areas of knowledge, trust, care, approachability, and comfort.

You can see the domains: casual, scrubs, and formal, each with and without a lab coat. The seventh category is business attire (future C-suite wannabes – you know who you are).

Over half of the participants indicated that how a physician dresses was important to them, with more than one in three stating that this influenced how happy they were with care received. Overall, respondents indicated that formal attire with white coats was the most preferred form of physician dress.

I found the discussion in the study worthwhile, along with the strengths and weaknesses of the author’s outline. They went to great lengths to design a nonbiased questionnaire and used a consistent approach to shooting their photos. They also discussed lab coats, long sleeves, and hygiene.

But what to draw from the findings? Does patient satisfaction matter or just clinical outcomes? Is patient happiness a means to an end or an end unto itself? Can I even get you exercised about a score of 6 versus 8 (a 25% difference)? For instance, imagine the worst-dressed doc – say shorts and flip-flops. Is that a 5.8 or a 2.3? The anchor matters, and it helps to put the ratings in context.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Dr. Flansbaum works for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., in both the divisions of hospital medicine and population health. He is a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine and served as a board member and officer.

Also in The Hospital Leader

•Hospitalists Can Improve Patient Trust…in Their Colleagues by Chris Moriates, MD, SFHM

•Treatment of Type II MIs by Brad Flansbaum, MD, MPH, MHM

•The $64,000 Question: How Can Hospitalists Improve Their HCAHPS Scores? by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

What is appropriate “ward garb”?

What is appropriate “ward garb”?

The question of appropriate ward garb is a problem for the ages. Compared with photo stills and films from the 1960s, the doctors of today appear like vagabonds. No ties, no lab coats, and scrub tops have become the norm for a number (a majority?) of hospital-based docs – and even more so on the surgical wards and in the ER.

Past studies have addressed patient preferences for provider dress, but none like the results of a recent survey.

From the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, comes a physician attire survey of a convenience sample of 4,000 patients at 10 U.S. academic medical centers. It included both inpatients and outpatients, and used the design of many previous studies, showing patients the same doctor dressed seven different ways. After viewing the photographs, the patients received surveys as to their preference of physician based on attire, as well as being asked to rate the physician in the areas of knowledge, trust, care, approachability, and comfort.

You can see the domains: casual, scrubs, and formal, each with and without a lab coat. The seventh category is business attire (future C-suite wannabes – you know who you are).

Over half of the participants indicated that how a physician dresses was important to them, with more than one in three stating that this influenced how happy they were with care received. Overall, respondents indicated that formal attire with white coats was the most preferred form of physician dress.

I found the discussion in the study worthwhile, along with the strengths and weaknesses of the author’s outline. They went to great lengths to design a nonbiased questionnaire and used a consistent approach to shooting their photos. They also discussed lab coats, long sleeves, and hygiene.

But what to draw from the findings? Does patient satisfaction matter or just clinical outcomes? Is patient happiness a means to an end or an end unto itself? Can I even get you exercised about a score of 6 versus 8 (a 25% difference)? For instance, imagine the worst-dressed doc – say shorts and flip-flops. Is that a 5.8 or a 2.3? The anchor matters, and it helps to put the ratings in context.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Dr. Flansbaum works for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., in both the divisions of hospital medicine and population health. He is a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine and served as a board member and officer.

Also in The Hospital Leader

•Hospitalists Can Improve Patient Trust…in Their Colleagues by Chris Moriates, MD, SFHM

•Treatment of Type II MIs by Brad Flansbaum, MD, MPH, MHM

•The $64,000 Question: How Can Hospitalists Improve Their HCAHPS Scores? by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

The question of appropriate ward garb is a problem for the ages. Compared with photo stills and films from the 1960s, the doctors of today appear like vagabonds. No ties, no lab coats, and scrub tops have become the norm for a number (a majority?) of hospital-based docs – and even more so on the surgical wards and in the ER.

Past studies have addressed patient preferences for provider dress, but none like the results of a recent survey.

From the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, comes a physician attire survey of a convenience sample of 4,000 patients at 10 U.S. academic medical centers. It included both inpatients and outpatients, and used the design of many previous studies, showing patients the same doctor dressed seven different ways. After viewing the photographs, the patients received surveys as to their preference of physician based on attire, as well as being asked to rate the physician in the areas of knowledge, trust, care, approachability, and comfort.

You can see the domains: casual, scrubs, and formal, each with and without a lab coat. The seventh category is business attire (future C-suite wannabes – you know who you are).

Over half of the participants indicated that how a physician dresses was important to them, with more than one in three stating that this influenced how happy they were with care received. Overall, respondents indicated that formal attire with white coats was the most preferred form of physician dress.

I found the discussion in the study worthwhile, along with the strengths and weaknesses of the author’s outline. They went to great lengths to design a nonbiased questionnaire and used a consistent approach to shooting their photos. They also discussed lab coats, long sleeves, and hygiene.

But what to draw from the findings? Does patient satisfaction matter or just clinical outcomes? Is patient happiness a means to an end or an end unto itself? Can I even get you exercised about a score of 6 versus 8 (a 25% difference)? For instance, imagine the worst-dressed doc – say shorts and flip-flops. Is that a 5.8 or a 2.3? The anchor matters, and it helps to put the ratings in context.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Dr. Flansbaum works for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., in both the divisions of hospital medicine and population health. He is a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine and served as a board member and officer.

Also in The Hospital Leader

•Hospitalists Can Improve Patient Trust…in Their Colleagues by Chris Moriates, MD, SFHM

•Treatment of Type II MIs by Brad Flansbaum, MD, MPH, MHM

•The $64,000 Question: How Can Hospitalists Improve Their HCAHPS Scores? by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

Disruptive physicians: Is this an HR or MEC issue?

it can greatly lower staff morale and compromise patient care. Addressing this behavior head-on is imperative, experts said, but knowing which route to take is not always clear.

Physician leaders may wonder: When is this a human resources (HR) issue and when should the medical executive committee (MEC) step in?

The answer depends on the circumstances and the employment status of the physician in question, said Mark Peters, a labor and employment attorney based in Nashville, Tenn.

“There are a couple of different considerations when deciding how, or more accurately who, should address disruptive physician behavior in the workplace,” Mr. Peters said in an interview. “The first consideration is whether the physician is employed by the health care entity or is a contractor. Typically, absent an employment relationship with the physician, human resources is not involved directly with the physician and the issue is handled through the MEC.”

However, in some cases both HR and the MEC may become involved. For instance, if the complaint is made by an employee, HR would likely get involved – regardless of whether the disruptive physician is a contractor – because employers have a legal duty to ensure a “hostile-free environment,” Mr. Peters said.

The hospital may also ask that the MEC intervene to ensure the medical staff understands all of the facts and can weigh in on whether the doctor is being treated fairly by the hospital, he said.

There are a range of advantages and disadvantages to each resolution path, said Jeffrey Moseley, a health law attorney based in Franklin, Tenn. The HR route usually means dealing with a single point person and typically the issue is resolved more swiftly. Going through the MEC, on the other hand, often takes months. The MEC path also means more people will be involved, and it’s possible the case may become more political, depending on the culture of the MEC.

“If you have to end up taking an action, the employment setting may be a quicker way to address the issue than going through the medical staff side,” Mr. Moseley said in an interview. “Most medical staffs, if they were to try to restrict or revoke privileges, they are going to have to go through a fair hearing and appeals, [which] can take 6 months easily. The downside to the employment side is you don’t get all the immunities that you get on the medical staff side.”

A disruptive physician issue handled by the MEC as a peer review matter or professional review action is protected under the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act, which shields the medical staff and/or hospital from civil damages in the event that they are sued. Additionally, information disclosed during the MEC process that is part of the peer review privilege is confidential and not necessarily discoverable by plaintiff’s attorneys in a subsequent court case.

The way the MEC handles the issue often hinges on the makeup of the committee, Mr. Moseley noted. In his experience, older medical staffs tend to be more sensitive to the accused physician and question whether the behavior is egregious. Older physicians are generally used to a more “captain of the ship” leadership style, with the doctor as the authority figure. Younger staffs are generally more sensitive to concerns about a hostile work environment and lean toward a team approach to health care.

“If your leadership on the medical staff is a [group of older doctors] versus a mix or younger docs, they might be more or less receptive to discipline [for] a behavioral issue, based on their worldview,” he said.

Disruptive behavior is best avoided by implementing sensitivity training and employing a zero tolerance policy for unprofessional behavior that applies to all staff members from the highest revenue generators to the lowest, no exceptions, Mr. Peters advised. “A top down culture that expects and requires professionalism amongst all medical staff [is key].”

it can greatly lower staff morale and compromise patient care. Addressing this behavior head-on is imperative, experts said, but knowing which route to take is not always clear.

Physician leaders may wonder: When is this a human resources (HR) issue and when should the medical executive committee (MEC) step in?

The answer depends on the circumstances and the employment status of the physician in question, said Mark Peters, a labor and employment attorney based in Nashville, Tenn.

“There are a couple of different considerations when deciding how, or more accurately who, should address disruptive physician behavior in the workplace,” Mr. Peters said in an interview. “The first consideration is whether the physician is employed by the health care entity or is a contractor. Typically, absent an employment relationship with the physician, human resources is not involved directly with the physician and the issue is handled through the MEC.”

However, in some cases both HR and the MEC may become involved. For instance, if the complaint is made by an employee, HR would likely get involved – regardless of whether the disruptive physician is a contractor – because employers have a legal duty to ensure a “hostile-free environment,” Mr. Peters said.

The hospital may also ask that the MEC intervene to ensure the medical staff understands all of the facts and can weigh in on whether the doctor is being treated fairly by the hospital, he said.

There are a range of advantages and disadvantages to each resolution path, said Jeffrey Moseley, a health law attorney based in Franklin, Tenn. The HR route usually means dealing with a single point person and typically the issue is resolved more swiftly. Going through the MEC, on the other hand, often takes months. The MEC path also means more people will be involved, and it’s possible the case may become more political, depending on the culture of the MEC.

“If you have to end up taking an action, the employment setting may be a quicker way to address the issue than going through the medical staff side,” Mr. Moseley said in an interview. “Most medical staffs, if they were to try to restrict or revoke privileges, they are going to have to go through a fair hearing and appeals, [which] can take 6 months easily. The downside to the employment side is you don’t get all the immunities that you get on the medical staff side.”

A disruptive physician issue handled by the MEC as a peer review matter or professional review action is protected under the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act, which shields the medical staff and/or hospital from civil damages in the event that they are sued. Additionally, information disclosed during the MEC process that is part of the peer review privilege is confidential and not necessarily discoverable by plaintiff’s attorneys in a subsequent court case.

The way the MEC handles the issue often hinges on the makeup of the committee, Mr. Moseley noted. In his experience, older medical staffs tend to be more sensitive to the accused physician and question whether the behavior is egregious. Older physicians are generally used to a more “captain of the ship” leadership style, with the doctor as the authority figure. Younger staffs are generally more sensitive to concerns about a hostile work environment and lean toward a team approach to health care.

“If your leadership on the medical staff is a [group of older doctors] versus a mix or younger docs, they might be more or less receptive to discipline [for] a behavioral issue, based on their worldview,” he said.

Disruptive behavior is best avoided by implementing sensitivity training and employing a zero tolerance policy for unprofessional behavior that applies to all staff members from the highest revenue generators to the lowest, no exceptions, Mr. Peters advised. “A top down culture that expects and requires professionalism amongst all medical staff [is key].”

it can greatly lower staff morale and compromise patient care. Addressing this behavior head-on is imperative, experts said, but knowing which route to take is not always clear.

Physician leaders may wonder: When is this a human resources (HR) issue and when should the medical executive committee (MEC) step in?

The answer depends on the circumstances and the employment status of the physician in question, said Mark Peters, a labor and employment attorney based in Nashville, Tenn.

“There are a couple of different considerations when deciding how, or more accurately who, should address disruptive physician behavior in the workplace,” Mr. Peters said in an interview. “The first consideration is whether the physician is employed by the health care entity or is a contractor. Typically, absent an employment relationship with the physician, human resources is not involved directly with the physician and the issue is handled through the MEC.”

However, in some cases both HR and the MEC may become involved. For instance, if the complaint is made by an employee, HR would likely get involved – regardless of whether the disruptive physician is a contractor – because employers have a legal duty to ensure a “hostile-free environment,” Mr. Peters said.

The hospital may also ask that the MEC intervene to ensure the medical staff understands all of the facts and can weigh in on whether the doctor is being treated fairly by the hospital, he said.

There are a range of advantages and disadvantages to each resolution path, said Jeffrey Moseley, a health law attorney based in Franklin, Tenn. The HR route usually means dealing with a single point person and typically the issue is resolved more swiftly. Going through the MEC, on the other hand, often takes months. The MEC path also means more people will be involved, and it’s possible the case may become more political, depending on the culture of the MEC.

“If you have to end up taking an action, the employment setting may be a quicker way to address the issue than going through the medical staff side,” Mr. Moseley said in an interview. “Most medical staffs, if they were to try to restrict or revoke privileges, they are going to have to go through a fair hearing and appeals, [which] can take 6 months easily. The downside to the employment side is you don’t get all the immunities that you get on the medical staff side.”

A disruptive physician issue handled by the MEC as a peer review matter or professional review action is protected under the Healthcare Quality Improvement Act, which shields the medical staff and/or hospital from civil damages in the event that they are sued. Additionally, information disclosed during the MEC process that is part of the peer review privilege is confidential and not necessarily discoverable by plaintiff’s attorneys in a subsequent court case.

The way the MEC handles the issue often hinges on the makeup of the committee, Mr. Moseley noted. In his experience, older medical staffs tend to be more sensitive to the accused physician and question whether the behavior is egregious. Older physicians are generally used to a more “captain of the ship” leadership style, with the doctor as the authority figure. Younger staffs are generally more sensitive to concerns about a hostile work environment and lean toward a team approach to health care.

“If your leadership on the medical staff is a [group of older doctors] versus a mix or younger docs, they might be more or less receptive to discipline [for] a behavioral issue, based on their worldview,” he said.

Disruptive behavior is best avoided by implementing sensitivity training and employing a zero tolerance policy for unprofessional behavior that applies to all staff members from the highest revenue generators to the lowest, no exceptions, Mr. Peters advised. “A top down culture that expects and requires professionalism amongst all medical staff [is key].”

Hospitalist NPs and PAs note progress

But remain underutilized

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) have become a more prominent part of the hospitalist workforce, and at many institutions, they account for a large proportion of patient care and have a powerful effect on a patient’s experience. But NP and PA roles in hospital medicine continue to evolve – and understanding what they do is still, at times, a work in progress.

One myth that persists regarding NPs and PAs is that, if you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all.

At the 2018 Annual Conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, Noam Shabani, MS, PA-C, lead physician assistant at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Hospital Medicine Unit, Boston, offered an example to help shatter this misperception.

Mr. Shabani described a 28-year-old woman who had a bachelor’s in biology with a premed track and spent 4 years as a paramedic before attending the physician assistant program at Duke University, Durham, N.C. As a new PA graduate, she was hired as a hospitalist at a community hospital in Kentucky.

Given this new PA’s clinical experience and formal education, there are certain skills she should bring to the table: the ability to develop a differential diagnosis and a good understanding of disease pathophysiology and the mechanisms of action of drugs. And because of her paramedic experience, she should be comfortable with making urgent clinical care decisions and should be proficient with electrocardiograms, as well as chest and abdominal x-rays.

But compared with a newly graduated NP with registered nurse (RN) floor experience, the PA is likely to be less familiar with hospital mechanics and systems, with leading goal of care discussions with patients and families, and with understanding nuances involved with transitions of care.

The subtle differences between NPs and PAs don’t end there. Because of the progressive policies and recently updated bylaws at the Kentucky hospital where the PA was hired, this health care professional can see patients and write notes independently without a physician signature. But because she practices in Kentucky, she is not allowed to prescribe Schedule II medications, per state law.

“This example demonstrates how nuanced and multi-layered the process of integrating NPs and PAs into hospitalist groups can be,” Mr. Shabani said.

Goals, roles, and expectations

Physician assistants and nurse practitioners have reported that their job descriptions, and the variety of roles they can play within HM teams, are becoming better understood by hospitalist physicians and administrators. However, they also have acknowledged that both PAs and NPs are still underutilized.

Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, an orthopedic service line administrator at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Waterbury, Conn., and an expert in NP and PA policy, has noticed growing enlightenment about PAs and NPs in her travels to conferences in recent years.

“I’m no longer explaining what a PA is and what an NP is, and the questions have become very sophisticated,” she said at HM18. “However, I spent the last two days in the exhibit hall, and some of the conversations I had with physicians are interesting in that the practice and utilization styles have not become sophisticated. So I think there is a lot of opportunity out there.”

Mr. Shabani said the hospitalist care provided by PAs and NPs sits “at the intersection” of state regulations, hospital bylaws, department utilization, and – of course – clinical experience and formal medical education.

“What this boils down to is first understanding these factors, followed by strategizing recruitment and training as a response,” he said.

Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM, associate director of clinical integration at Adfinitas Health in Hanover, Md., and a Society of Hospital Medicine board member, said that, even though she usually sees and hears about a 10%-15% productivity gap between physicians and PAs or NPs, there is no good reason that an experienced PA or NP should not be able to handle the same patient load as a physician hospitalist – if that’s the goal.

“Part of it is about communication of expectation,” she said, noting that organizations must provide the training to allows NPs and PAs to reach prescribed goals along with an adequate level of administrative support. “I think we shouldn’t accept those gaps in productivity.”

Nicolas Houghton, DNP, ACNP-BC, CFRN, nurse practitioner/physician assistant manager at the Cleveland Clinic, thinks that it is completely reasonable for health care organizations to have an expectation that, at the 3- to 5-year mark, NPs and PAs “are really going to be functioning at very high levels that may be nearly indistinguishable.”

Dr. Houghton and Mr. Shabani agreed that, while they had considerably different duties at the start of their careers, they now have clinical roles which mirror one another.

For example, they agreed on these basics: NPs must be a certified RN, while a PA can have any undergraduate degree with certain prerequisite courses such as biology and chemistry. All PAs are trained in general medicine, while NPs specialize in areas such as acute care, family medicine, geriatrics, and women’s health. NPs need 500 didactic hours and 500-700 clinical hours in their area of expertise, while physician assistants need 1,000 didactic and 2,000 clinical hours spread over many disciplines.

For NP’s, required clinical rotations depend on the specialty, while all PAs need to complete rotations in inpatient medicine, emergency medicine, primary care, surgery, psychiatry, pediatrics, and ob.gyn. Also, NPs can practice independently in 23 states and the District of Columbia, while PAs must have a supervising physician. About 10% of NPs work in hospital settings, and about 39% of PAs work in hospital settings, they said.

Dr. Houghton and Mr. Shabani emphasized that Medicare does recognize NP and PA services as physician services. The official language, in place since 1998, is that their services “are the type that are considered physician’s services if furnished by a doctor of medicine or osteopathy.”

Mr. Shabani said this remained a very relevant issue. “I can’t overstate how important this is,” he said.

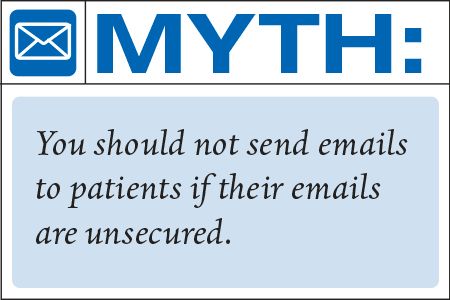

Debunking myths

Several myths continue to persist about PAs and NPs, Ms. Marriott said. Some administrators and physicians believe that they can’t see new patients, that a physician must see every patient, that a physician cosignature means that a claim can be submitted under the physician’s name, that reimbursement for services provided by PAs and NPs “leaves 15% on the table,” and that patients won’t be happy being seen by a PA or an NP. All of those things are false, she said.

“We really need to improve people’s understanding in a lot of different places – it’s not just at the clinician level,” she said. “It goes all the way through the operations team, and the operations team has some very old-fashioned thinking about what PAs and NPs really are, which is – they believe – clinical support staff.”

But she suggested that the phrase “working at the top of one’s license” can be used too freely – individual experience and ability will encompass a range of practices, she said.

“I’m licensed to drive a car,” she said. “But you do not want me in the Daytona 500. I am not capable of driving a race car.”

She cautioned that nurse practitioner care must still involve an element of collaboration, according to the Medicaid benefit policy manual, even if they work in states that allow NPs to provide “independent” care. They must have documentation “indicating the relationships that they have with physicians to deal with issues outside their scope of practice,” the manual says.

“Don’t ask me how people prove it,” Ms. Marriott said. “Just know that, if someone were to audit you, then you would need to show what this looks like.”

Regarding the 15% myth, she showed a calculation: Data from the Medical Group Management Association show that median annual compensation for a physician is $134 an hour and that it’s approximately $52 an hour for a PA or NP. An admission history and physical that takes an hour can be reimbursed at $102 for a physician and at 85% of that – $87 – for a PA or NP. That leaves a deficit of $32 for the physician and a surplus of $35 for the PA or NP.

“If you properly deploy your PAs and NPs, you’re going to generate positive margins,” Ms. Marriott said.

Physicians often scurry about seeing all the patients that have already been seen by a PA, she said, because they think they must capture the extra 15% reimbursement. But that is unnecessary, she said.

“Go do another admission. You should see patients because of their clinical condition. My point is not that you go running around because you want to capture the extra 15% – because that provides no additional medically necessary care.”

Changing practice

Many institutions continue to be hamstrung by their own bylaws in the use of NPs and PAs. It’s true that a physician doesn’t have to see every patient, unless it’s required in a hospital’s rules, Ms. Marriott noted.

“Somebody step up, get on the bylaws committee, and say, ‘Let’s update these.’ ” she said.

As for patient satisfaction, access and convenience routinely rank higher on the patient priority lists than provider credentials. “The patient wants to get off the gurney in the ED and get to a room,” she said.

But changing hospital bylaws and practices is also about the responsible use of health care dollars, Ms. Marriott affirmed.

“More patients seen in a timely fashion, and quality metrics improvement: Those are all things that are really, really important,” she said. “As a result, [if bylaws and practice patterns are changed] the physicians are hopefully going to be happier, certainly the administration is going to be happier, and the patients are going to fare better.”

Scott Faust, MS, APRN, CNP, an acute care nurse practitioner at Health Partners in St. Paul, Minn., said that teamwork without egos is crucial to success for all providers on the hospital medicine team, especially at busier moments.

“Nobody wants to be in this alone,” he said. “I think the hospitalist teams that work well are the ones that check their titles at the door.”

PAs and NPs generally agree that, as long as all clinical staffers are working within their areas of skill without being overly concerned about specific titles and roles, hospitals and patients will benefit.

“I’ve had physicians at my organization say ‘We need to have an NP and PA set of educational requirements,’ and I said, ‘We have some already for physicians, right? Why aren’t we using that?’ ” Dr. Houghton said. “I think we should have the same expectations clinically. At the end of the day, the patient deserves the same outcomes and the same care, whether they’re being cared for by a physician, an NP, or a PA.”

Onboarding NPs and PAs

According to SHM’s Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant Committee, the integration of a new NP or PA hire, whether experienced or not, requires up-front organization and planning for the employee as he or she enters into a new practice.

To that end, the NP/PA Committee created a toolkit to aid health care organizations in their integration of NP and PA staffers into hospital medicine practice groups. The document includes resources for recruiting and interviewing NPs and PAs, information about orientation and onboarding, detailed descriptions of models of care to aid in the utilization of NPs and PAs, best practices for staff retention, insights on billing and reimbursement, and ideas for program evaluation.

Readers can download the Onboarding Toolkit in PDF format at shm.hospitalmedicine.org/acton/attachment/25526/f-040f/1/-/-/-/-/SHM_NPPA_OboardingToolkit.pdf.

But remain underutilized

But remain underutilized

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) have become a more prominent part of the hospitalist workforce, and at many institutions, they account for a large proportion of patient care and have a powerful effect on a patient’s experience. But NP and PA roles in hospital medicine continue to evolve – and understanding what they do is still, at times, a work in progress.

One myth that persists regarding NPs and PAs is that, if you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all.

At the 2018 Annual Conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, Noam Shabani, MS, PA-C, lead physician assistant at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Hospital Medicine Unit, Boston, offered an example to help shatter this misperception.

Mr. Shabani described a 28-year-old woman who had a bachelor’s in biology with a premed track and spent 4 years as a paramedic before attending the physician assistant program at Duke University, Durham, N.C. As a new PA graduate, she was hired as a hospitalist at a community hospital in Kentucky.

Given this new PA’s clinical experience and formal education, there are certain skills she should bring to the table: the ability to develop a differential diagnosis and a good understanding of disease pathophysiology and the mechanisms of action of drugs. And because of her paramedic experience, she should be comfortable with making urgent clinical care decisions and should be proficient with electrocardiograms, as well as chest and abdominal x-rays.

But compared with a newly graduated NP with registered nurse (RN) floor experience, the PA is likely to be less familiar with hospital mechanics and systems, with leading goal of care discussions with patients and families, and with understanding nuances involved with transitions of care.

The subtle differences between NPs and PAs don’t end there. Because of the progressive policies and recently updated bylaws at the Kentucky hospital where the PA was hired, this health care professional can see patients and write notes independently without a physician signature. But because she practices in Kentucky, she is not allowed to prescribe Schedule II medications, per state law.

“This example demonstrates how nuanced and multi-layered the process of integrating NPs and PAs into hospitalist groups can be,” Mr. Shabani said.

Goals, roles, and expectations

Physician assistants and nurse practitioners have reported that their job descriptions, and the variety of roles they can play within HM teams, are becoming better understood by hospitalist physicians and administrators. However, they also have acknowledged that both PAs and NPs are still underutilized.

Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, an orthopedic service line administrator at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Waterbury, Conn., and an expert in NP and PA policy, has noticed growing enlightenment about PAs and NPs in her travels to conferences in recent years.

“I’m no longer explaining what a PA is and what an NP is, and the questions have become very sophisticated,” she said at HM18. “However, I spent the last two days in the exhibit hall, and some of the conversations I had with physicians are interesting in that the practice and utilization styles have not become sophisticated. So I think there is a lot of opportunity out there.”

Mr. Shabani said the hospitalist care provided by PAs and NPs sits “at the intersection” of state regulations, hospital bylaws, department utilization, and – of course – clinical experience and formal medical education.

“What this boils down to is first understanding these factors, followed by strategizing recruitment and training as a response,” he said.

Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM, associate director of clinical integration at Adfinitas Health in Hanover, Md., and a Society of Hospital Medicine board member, said that, even though she usually sees and hears about a 10%-15% productivity gap between physicians and PAs or NPs, there is no good reason that an experienced PA or NP should not be able to handle the same patient load as a physician hospitalist – if that’s the goal.

“Part of it is about communication of expectation,” she said, noting that organizations must provide the training to allows NPs and PAs to reach prescribed goals along with an adequate level of administrative support. “I think we shouldn’t accept those gaps in productivity.”

Nicolas Houghton, DNP, ACNP-BC, CFRN, nurse practitioner/physician assistant manager at the Cleveland Clinic, thinks that it is completely reasonable for health care organizations to have an expectation that, at the 3- to 5-year mark, NPs and PAs “are really going to be functioning at very high levels that may be nearly indistinguishable.”

Dr. Houghton and Mr. Shabani agreed that, while they had considerably different duties at the start of their careers, they now have clinical roles which mirror one another.

For example, they agreed on these basics: NPs must be a certified RN, while a PA can have any undergraduate degree with certain prerequisite courses such as biology and chemistry. All PAs are trained in general medicine, while NPs specialize in areas such as acute care, family medicine, geriatrics, and women’s health. NPs need 500 didactic hours and 500-700 clinical hours in their area of expertise, while physician assistants need 1,000 didactic and 2,000 clinical hours spread over many disciplines.

For NP’s, required clinical rotations depend on the specialty, while all PAs need to complete rotations in inpatient medicine, emergency medicine, primary care, surgery, psychiatry, pediatrics, and ob.gyn. Also, NPs can practice independently in 23 states and the District of Columbia, while PAs must have a supervising physician. About 10% of NPs work in hospital settings, and about 39% of PAs work in hospital settings, they said.

Dr. Houghton and Mr. Shabani emphasized that Medicare does recognize NP and PA services as physician services. The official language, in place since 1998, is that their services “are the type that are considered physician’s services if furnished by a doctor of medicine or osteopathy.”

Mr. Shabani said this remained a very relevant issue. “I can’t overstate how important this is,” he said.

Debunking myths

Several myths continue to persist about PAs and NPs, Ms. Marriott said. Some administrators and physicians believe that they can’t see new patients, that a physician must see every patient, that a physician cosignature means that a claim can be submitted under the physician’s name, that reimbursement for services provided by PAs and NPs “leaves 15% on the table,” and that patients won’t be happy being seen by a PA or an NP. All of those things are false, she said.

“We really need to improve people’s understanding in a lot of different places – it’s not just at the clinician level,” she said. “It goes all the way through the operations team, and the operations team has some very old-fashioned thinking about what PAs and NPs really are, which is – they believe – clinical support staff.”

But she suggested that the phrase “working at the top of one’s license” can be used too freely – individual experience and ability will encompass a range of practices, she said.

“I’m licensed to drive a car,” she said. “But you do not want me in the Daytona 500. I am not capable of driving a race car.”