User login

Clinical Pearl: Mastering the Flexible Scalpel Blade With the Banana Practice Model

The flexible scalpel blade (FSB) is a 2-sided handheld razor blade that serves as a pivotal instrument in certain dermatologic procedures. Its unrivaled sharpness1 permits pinpoint precision for shave biopsies, excisions of superficial lesions,2 scar contouring, and harvesting of split-thickness skin grafts.3 Given its flexibility and long edge, considerable manual dexterity and skill are required to maximize its full potential.

Practice Gap

Prior to practicing on live patients, students on clinical rotation would benefit from in vitro skin simulators to practice correct hand position, FSB control for concave and convex surface cutting, and safety. Prior practice models have included mannequins, tomatoes, and eggplants.4,5 Here, the authors recommend the use of a banana (genus Musa). In addition to its year-round availability, economic feasibility, simplicity, and portability, the banana has colored skin that well represents the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue, allowing for visual feedback. Furthermore, its contour irregularities simulate convexities and concavities for various anatomic locations. Although the firmness of a yellow-green banana provides immediate tissue feedback, the softness and pliability of a ripe banana simulates the consistency of older skin and the use of appropriate traction.

Tools

To begin, one simply requires a marking pen, banana, and razor blade. Various shapes, including a circle, ellipse, rectangle, trapezoid, triangle, and multilobed lesion are demarcated by students or attendings (Figure 1).

The Technique

To handle the FSB, one can hold the lateral edges of the blade between the thumb and index finger or between the thumb and middle finger. The thumb and index finger position allows for additional flexible working space and visualization, increased traction by the remaining 3 fingers, and greater ease of removal of lesions with considerable height. The thumb and middle finger hold allows for versatile use of the index finger of the same hand for stabilizing the center of the blade, fixing the tissue on the FSB while it is removed, and sliding the specimen off the FSB. It is important to maintain a fixed distance from the blade to the metacarpals at all times to ensure smooth advancement of the blade and visualization. Beginners can lift the pinky finger of the hand holding the FSB and move the finger up and down to control the angle of the blade.

Practice Implications

Generally, we utilize various techniques of shaving using the FSB. We approach the target lesion 2 to 3 mm from the marked location and slide parallel to the skin surface and perpendicular to the lesion until the epidermis is penetrated. Second, we advance the blade toward the lesion with careful attention paid to the perimeter of the lesion and the points of contact of the FSB. For lesions with hardier consistencies, a sawing motion of the blade is employed, which also requires controlled tilting of the wrist to maintain an even depth and smooth bevel. To cut deeper, flexing the FSB with lateral pressure is helpful. More shallow lesions require the instrument to be flatter and less bowed. When finishing the shave, it is important to start angling the blade upward early, either at the center of the targeted lesion or 2 to 3 mm before the demarcated edge of the skin graft, while applying traction away from the lesion and slight downward pressure with the nondominant hand.

For larger lesions, the perimeter may be more difficult to remove precisely and can be achieved by rotating the blade around the lesion with focus on one point of contact of the FSB to cut and glide through the tissue’s perimeter. To achieve a more exact wound edge and to preclude jagged borders, a No. 15 blade can be used to score the perimeter very superficially to the papillary dermis prior to shave removal. The main disadvantage, however, is that the beveled edge is removed.

In summary, the FSB is an exceptional tool for biopsies, tumor removal, scar contouring, and split-thickness skin grafts. Through the banana practice model, one can attain fine control and reap the benefits of the FSB after meticulous and dedicated training.

- Awadalla B, Hexsel C, Goldberg LH. The sharpness of blades used in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:105-107.

- Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Goldberg LH, Firoz B, et al. Horizontal excision of in situ epidermal tumors using a flexible blade. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:234-236.

- Hexsel CL, Loosemore M, Goldberg LH, et al. Postauricular skin: an excellent donor site for split-thickness skin grafts for the head, neck, and upper chest. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:48-52.

- Chen TM, Mellette JR. Surgical pearl: tomato—an alternative model for shave biopsy training. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:517-518.

- Wang X, Albahrani Y, Pan M, et al. Skin simulators for dermatological procedures. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt33j6x4nx.

The flexible scalpel blade (FSB) is a 2-sided handheld razor blade that serves as a pivotal instrument in certain dermatologic procedures. Its unrivaled sharpness1 permits pinpoint precision for shave biopsies, excisions of superficial lesions,2 scar contouring, and harvesting of split-thickness skin grafts.3 Given its flexibility and long edge, considerable manual dexterity and skill are required to maximize its full potential.

Practice Gap

Prior to practicing on live patients, students on clinical rotation would benefit from in vitro skin simulators to practice correct hand position, FSB control for concave and convex surface cutting, and safety. Prior practice models have included mannequins, tomatoes, and eggplants.4,5 Here, the authors recommend the use of a banana (genus Musa). In addition to its year-round availability, economic feasibility, simplicity, and portability, the banana has colored skin that well represents the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue, allowing for visual feedback. Furthermore, its contour irregularities simulate convexities and concavities for various anatomic locations. Although the firmness of a yellow-green banana provides immediate tissue feedback, the softness and pliability of a ripe banana simulates the consistency of older skin and the use of appropriate traction.

Tools

To begin, one simply requires a marking pen, banana, and razor blade. Various shapes, including a circle, ellipse, rectangle, trapezoid, triangle, and multilobed lesion are demarcated by students or attendings (Figure 1).

The Technique

To handle the FSB, one can hold the lateral edges of the blade between the thumb and index finger or between the thumb and middle finger. The thumb and index finger position allows for additional flexible working space and visualization, increased traction by the remaining 3 fingers, and greater ease of removal of lesions with considerable height. The thumb and middle finger hold allows for versatile use of the index finger of the same hand for stabilizing the center of the blade, fixing the tissue on the FSB while it is removed, and sliding the specimen off the FSB. It is important to maintain a fixed distance from the blade to the metacarpals at all times to ensure smooth advancement of the blade and visualization. Beginners can lift the pinky finger of the hand holding the FSB and move the finger up and down to control the angle of the blade.

Practice Implications

Generally, we utilize various techniques of shaving using the FSB. We approach the target lesion 2 to 3 mm from the marked location and slide parallel to the skin surface and perpendicular to the lesion until the epidermis is penetrated. Second, we advance the blade toward the lesion with careful attention paid to the perimeter of the lesion and the points of contact of the FSB. For lesions with hardier consistencies, a sawing motion of the blade is employed, which also requires controlled tilting of the wrist to maintain an even depth and smooth bevel. To cut deeper, flexing the FSB with lateral pressure is helpful. More shallow lesions require the instrument to be flatter and less bowed. When finishing the shave, it is important to start angling the blade upward early, either at the center of the targeted lesion or 2 to 3 mm before the demarcated edge of the skin graft, while applying traction away from the lesion and slight downward pressure with the nondominant hand.

For larger lesions, the perimeter may be more difficult to remove precisely and can be achieved by rotating the blade around the lesion with focus on one point of contact of the FSB to cut and glide through the tissue’s perimeter. To achieve a more exact wound edge and to preclude jagged borders, a No. 15 blade can be used to score the perimeter very superficially to the papillary dermis prior to shave removal. The main disadvantage, however, is that the beveled edge is removed.

In summary, the FSB is an exceptional tool for biopsies, tumor removal, scar contouring, and split-thickness skin grafts. Through the banana practice model, one can attain fine control and reap the benefits of the FSB after meticulous and dedicated training.

The flexible scalpel blade (FSB) is a 2-sided handheld razor blade that serves as a pivotal instrument in certain dermatologic procedures. Its unrivaled sharpness1 permits pinpoint precision for shave biopsies, excisions of superficial lesions,2 scar contouring, and harvesting of split-thickness skin grafts.3 Given its flexibility and long edge, considerable manual dexterity and skill are required to maximize its full potential.

Practice Gap

Prior to practicing on live patients, students on clinical rotation would benefit from in vitro skin simulators to practice correct hand position, FSB control for concave and convex surface cutting, and safety. Prior practice models have included mannequins, tomatoes, and eggplants.4,5 Here, the authors recommend the use of a banana (genus Musa). In addition to its year-round availability, economic feasibility, simplicity, and portability, the banana has colored skin that well represents the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue, allowing for visual feedback. Furthermore, its contour irregularities simulate convexities and concavities for various anatomic locations. Although the firmness of a yellow-green banana provides immediate tissue feedback, the softness and pliability of a ripe banana simulates the consistency of older skin and the use of appropriate traction.

Tools

To begin, one simply requires a marking pen, banana, and razor blade. Various shapes, including a circle, ellipse, rectangle, trapezoid, triangle, and multilobed lesion are demarcated by students or attendings (Figure 1).

The Technique

To handle the FSB, one can hold the lateral edges of the blade between the thumb and index finger or between the thumb and middle finger. The thumb and index finger position allows for additional flexible working space and visualization, increased traction by the remaining 3 fingers, and greater ease of removal of lesions with considerable height. The thumb and middle finger hold allows for versatile use of the index finger of the same hand for stabilizing the center of the blade, fixing the tissue on the FSB while it is removed, and sliding the specimen off the FSB. It is important to maintain a fixed distance from the blade to the metacarpals at all times to ensure smooth advancement of the blade and visualization. Beginners can lift the pinky finger of the hand holding the FSB and move the finger up and down to control the angle of the blade.

Practice Implications

Generally, we utilize various techniques of shaving using the FSB. We approach the target lesion 2 to 3 mm from the marked location and slide parallel to the skin surface and perpendicular to the lesion until the epidermis is penetrated. Second, we advance the blade toward the lesion with careful attention paid to the perimeter of the lesion and the points of contact of the FSB. For lesions with hardier consistencies, a sawing motion of the blade is employed, which also requires controlled tilting of the wrist to maintain an even depth and smooth bevel. To cut deeper, flexing the FSB with lateral pressure is helpful. More shallow lesions require the instrument to be flatter and less bowed. When finishing the shave, it is important to start angling the blade upward early, either at the center of the targeted lesion or 2 to 3 mm before the demarcated edge of the skin graft, while applying traction away from the lesion and slight downward pressure with the nondominant hand.

For larger lesions, the perimeter may be more difficult to remove precisely and can be achieved by rotating the blade around the lesion with focus on one point of contact of the FSB to cut and glide through the tissue’s perimeter. To achieve a more exact wound edge and to preclude jagged borders, a No. 15 blade can be used to score the perimeter very superficially to the papillary dermis prior to shave removal. The main disadvantage, however, is that the beveled edge is removed.

In summary, the FSB is an exceptional tool for biopsies, tumor removal, scar contouring, and split-thickness skin grafts. Through the banana practice model, one can attain fine control and reap the benefits of the FSB after meticulous and dedicated training.

- Awadalla B, Hexsel C, Goldberg LH. The sharpness of blades used in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:105-107.

- Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Goldberg LH, Firoz B, et al. Horizontal excision of in situ epidermal tumors using a flexible blade. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:234-236.

- Hexsel CL, Loosemore M, Goldberg LH, et al. Postauricular skin: an excellent donor site for split-thickness skin grafts for the head, neck, and upper chest. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:48-52.

- Chen TM, Mellette JR. Surgical pearl: tomato—an alternative model for shave biopsy training. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:517-518.

- Wang X, Albahrani Y, Pan M, et al. Skin simulators for dermatological procedures. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt33j6x4nx.

- Awadalla B, Hexsel C, Goldberg LH. The sharpness of blades used in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:105-107.

- Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Goldberg LH, Firoz B, et al. Horizontal excision of in situ epidermal tumors using a flexible blade. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:234-236.

- Hexsel CL, Loosemore M, Goldberg LH, et al. Postauricular skin: an excellent donor site for split-thickness skin grafts for the head, neck, and upper chest. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:48-52.

- Chen TM, Mellette JR. Surgical pearl: tomato—an alternative model for shave biopsy training. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:517-518.

- Wang X, Albahrani Y, Pan M, et al. Skin simulators for dermatological procedures. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt33j6x4nx.

Cosmeceuticals and Alternative Therapies for Rosacea

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

Isotretinoin for Acne: Tips for Prescribing and Managing Patient Concerns

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Most important is what you need to know before the first visit. As the prescribing physician, you must be familiar with the iPLEDGE program. Because of the complexity of the program, consider identifying a physician in your area to refer patients if you are not going to be a regular prescriber of the medication.

If you are enrolled in iPLEDGE, let your patients (and/or their parents/guardians) know that there is a great deal of misinformation on the Internet. Reiterate that you and your staff are available to discuss their concerns. Also, give them reliable sources of information, such as the American Academy of Dermatology's patient information sheet as well as the Mayo Clinic's acne information. Drugs.com is another resource.

All patients—males, females who cannot become pregnant, and females of childbearing potential (FCBPs)—must be aware that this medication can cause birth defects if taken during pregnancy. They must be informed that the medication is not to be shared with anyone and that they should not give blood while taking this medication.

What treatment course do you recommend?

My evidence-based approach is a course of isotretinoin totaling a minimum of 150 mg per kilogram body weight. Do not give a more abbreviated course unless the patient has cleared early; even then I tend to complete 150 mg when possible. There is published evidence that pushing the course to a total of 220 mg per kilogram body weight results in a longer remission.

Generally, I do few laboratory tests other than pretreatment lipid panels as well as 1 or 2 follow-up lipid panels at monthly intervals. To comply with the iPLEDGE program, FCBP patients must have a monthly pregnancy test, which is reported on the iPLEDGE website before the patient can be prescribed the drug and receive the drug from a pharmacist who is participating in the iPLEDGE program.

One of the defects of the iPLEDGE system is that although only a 30-day supply of pills can be prescribed, it is difficult to always bring a patient back in exactly 30 days; for example, we work on a 4-week cycle and 30 days brings us into the next week or uncommonly the weekend when we do not see patients. Our male patients or females not of childbearing potential are not affected, but for our FCBP patients, it means usually scheduling visits at 35-day intervals because the pregnancy tests must be performed at minimum 28-day intervals and the prescription cannot be written and the pregnancy test recorded until after at least 30 days.

What are the side effects?

The common side effects are what you would expect from a medicine that is supposed to dry up the oil on your skin: dryness of the lips, mouth, and skin, as well as rashes due to the dryness. There also can be minor swelling of the eyelids or lips, nosebleeds, upset stomach, and thinning of the hair; dryness of the scalp may occur. I recommend using a little petroleum jelly inside the nostrils at night to counteract the dryness that leads to nosebleeds, and saline drops or gel for the eyes, especially for contact lens wearers.

Joint aches and pains have been reported, though I rarely see those effects in patients who are physically active such as those participating in competitive sports. Mood changes have been reported, including suicidal ideation.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

There is so much false information on the Internet about the dangers of isotretinoin, leaving some patients (and parents/guardians) too afraid to use it. I sympathize with this anxiety, but I do endeavor to point out that the birth defects occur only in women taking the drug while pregnant and have not been reported to occur after the drug is out of the patient's system.

Similarly, I point out that almost all of the evidence-based studies failed to confirm any association between the use of isotretinoin and depression, teenage suicide, and subsequent inflammatory bowel disease. Nonetheless, I mention these issues and recommend that the parents/guardians observe the teenager; in the case of adult patients, they themselves must be sensitive to symptoms.

Suggested Readings

American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on isotretinoin. https://www.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Published December 9, 2000. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed May 18, 2017.

Blasiak RC, Stamey CR, Burkhart CN, et al. High-dose isotretinoin treatment and the rate of retrial, relapse, and adverse effects in patients with acne vulgaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1392-1398.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Most important is what you need to know before the first visit. As the prescribing physician, you must be familiar with the iPLEDGE program. Because of the complexity of the program, consider identifying a physician in your area to refer patients if you are not going to be a regular prescriber of the medication.

If you are enrolled in iPLEDGE, let your patients (and/or their parents/guardians) know that there is a great deal of misinformation on the Internet. Reiterate that you and your staff are available to discuss their concerns. Also, give them reliable sources of information, such as the American Academy of Dermatology's patient information sheet as well as the Mayo Clinic's acne information. Drugs.com is another resource.

All patients—males, females who cannot become pregnant, and females of childbearing potential (FCBPs)—must be aware that this medication can cause birth defects if taken during pregnancy. They must be informed that the medication is not to be shared with anyone and that they should not give blood while taking this medication.

What treatment course do you recommend?

My evidence-based approach is a course of isotretinoin totaling a minimum of 150 mg per kilogram body weight. Do not give a more abbreviated course unless the patient has cleared early; even then I tend to complete 150 mg when possible. There is published evidence that pushing the course to a total of 220 mg per kilogram body weight results in a longer remission.

Generally, I do few laboratory tests other than pretreatment lipid panels as well as 1 or 2 follow-up lipid panels at monthly intervals. To comply with the iPLEDGE program, FCBP patients must have a monthly pregnancy test, which is reported on the iPLEDGE website before the patient can be prescribed the drug and receive the drug from a pharmacist who is participating in the iPLEDGE program.

One of the defects of the iPLEDGE system is that although only a 30-day supply of pills can be prescribed, it is difficult to always bring a patient back in exactly 30 days; for example, we work on a 4-week cycle and 30 days brings us into the next week or uncommonly the weekend when we do not see patients. Our male patients or females not of childbearing potential are not affected, but for our FCBP patients, it means usually scheduling visits at 35-day intervals because the pregnancy tests must be performed at minimum 28-day intervals and the prescription cannot be written and the pregnancy test recorded until after at least 30 days.

What are the side effects?

The common side effects are what you would expect from a medicine that is supposed to dry up the oil on your skin: dryness of the lips, mouth, and skin, as well as rashes due to the dryness. There also can be minor swelling of the eyelids or lips, nosebleeds, upset stomach, and thinning of the hair; dryness of the scalp may occur. I recommend using a little petroleum jelly inside the nostrils at night to counteract the dryness that leads to nosebleeds, and saline drops or gel for the eyes, especially for contact lens wearers.

Joint aches and pains have been reported, though I rarely see those effects in patients who are physically active such as those participating in competitive sports. Mood changes have been reported, including suicidal ideation.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

There is so much false information on the Internet about the dangers of isotretinoin, leaving some patients (and parents/guardians) too afraid to use it. I sympathize with this anxiety, but I do endeavor to point out that the birth defects occur only in women taking the drug while pregnant and have not been reported to occur after the drug is out of the patient's system.

Similarly, I point out that almost all of the evidence-based studies failed to confirm any association between the use of isotretinoin and depression, teenage suicide, and subsequent inflammatory bowel disease. Nonetheless, I mention these issues and recommend that the parents/guardians observe the teenager; in the case of adult patients, they themselves must be sensitive to symptoms.

Suggested Readings

American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on isotretinoin. https://www.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Published December 9, 2000. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed May 18, 2017.

Blasiak RC, Stamey CR, Burkhart CN, et al. High-dose isotretinoin treatment and the rate of retrial, relapse, and adverse effects in patients with acne vulgaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1392-1398.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Most important is what you need to know before the first visit. As the prescribing physician, you must be familiar with the iPLEDGE program. Because of the complexity of the program, consider identifying a physician in your area to refer patients if you are not going to be a regular prescriber of the medication.

If you are enrolled in iPLEDGE, let your patients (and/or their parents/guardians) know that there is a great deal of misinformation on the Internet. Reiterate that you and your staff are available to discuss their concerns. Also, give them reliable sources of information, such as the American Academy of Dermatology's patient information sheet as well as the Mayo Clinic's acne information. Drugs.com is another resource.

All patients—males, females who cannot become pregnant, and females of childbearing potential (FCBPs)—must be aware that this medication can cause birth defects if taken during pregnancy. They must be informed that the medication is not to be shared with anyone and that they should not give blood while taking this medication.

What treatment course do you recommend?

My evidence-based approach is a course of isotretinoin totaling a minimum of 150 mg per kilogram body weight. Do not give a more abbreviated course unless the patient has cleared early; even then I tend to complete 150 mg when possible. There is published evidence that pushing the course to a total of 220 mg per kilogram body weight results in a longer remission.

Generally, I do few laboratory tests other than pretreatment lipid panels as well as 1 or 2 follow-up lipid panels at monthly intervals. To comply with the iPLEDGE program, FCBP patients must have a monthly pregnancy test, which is reported on the iPLEDGE website before the patient can be prescribed the drug and receive the drug from a pharmacist who is participating in the iPLEDGE program.

One of the defects of the iPLEDGE system is that although only a 30-day supply of pills can be prescribed, it is difficult to always bring a patient back in exactly 30 days; for example, we work on a 4-week cycle and 30 days brings us into the next week or uncommonly the weekend when we do not see patients. Our male patients or females not of childbearing potential are not affected, but for our FCBP patients, it means usually scheduling visits at 35-day intervals because the pregnancy tests must be performed at minimum 28-day intervals and the prescription cannot be written and the pregnancy test recorded until after at least 30 days.

What are the side effects?

The common side effects are what you would expect from a medicine that is supposed to dry up the oil on your skin: dryness of the lips, mouth, and skin, as well as rashes due to the dryness. There also can be minor swelling of the eyelids or lips, nosebleeds, upset stomach, and thinning of the hair; dryness of the scalp may occur. I recommend using a little petroleum jelly inside the nostrils at night to counteract the dryness that leads to nosebleeds, and saline drops or gel for the eyes, especially for contact lens wearers.

Joint aches and pains have been reported, though I rarely see those effects in patients who are physically active such as those participating in competitive sports. Mood changes have been reported, including suicidal ideation.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

There is so much false information on the Internet about the dangers of isotretinoin, leaving some patients (and parents/guardians) too afraid to use it. I sympathize with this anxiety, but I do endeavor to point out that the birth defects occur only in women taking the drug while pregnant and have not been reported to occur after the drug is out of the patient's system.

Similarly, I point out that almost all of the evidence-based studies failed to confirm any association between the use of isotretinoin and depression, teenage suicide, and subsequent inflammatory bowel disease. Nonetheless, I mention these issues and recommend that the parents/guardians observe the teenager; in the case of adult patients, they themselves must be sensitive to symptoms.

Suggested Readings

American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on isotretinoin. https://www.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Published December 9, 2000. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed May 18, 2017.

Blasiak RC, Stamey CR, Burkhart CN, et al. High-dose isotretinoin treatment and the rate of retrial, relapse, and adverse effects in patients with acne vulgaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1392-1398.

Psoriasis on the Hands and Feet: How Patients Should Care for These Areas

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Patients with this condition need to avoid friction and excessive moisture. They should be counseled to use gloves for excessive wet work. I recommend they use cotton gloves on the hands, and then cover those with rubber gloves. Patients should use a hand emollient regularly, including after each time they wash their hands or have exposure to water. If the patient lifts weights, I recommend he/she use weight-lifting gloves to reduce friction.

What are your go to treatments? What are the side effects?

The first line of therapy for hand and foot psoriasis is a topical agent. I most often use a combination of topical steroids and a topical vitamin D analogue. If insurance is amenable, I may use a fixed combination of topical steroid and vitamin D analogue.

If topical therapies are not successful, I often consider using excimer laser therapy, which requires the patient to come to the office twice weekly, so it is important to determine if this therapy is compatible with the patient's schedule. Other options include oral and biological therapies. Apremilast is a reasonable first-line systemic therapy given that it is an oral therapy, requires no laboratory monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile. Alternatively, biologic agents can be utilized. There are several analyses available looking at the efficacy of different biologics in hand and foot psoriasis, but at this point there is no consensus first choice for a biologic in this condition. Many available biologics may have a notable impact though.

The side effects of therapies for psoriasis are well established. Topical therapies and excimer laser are relatively safe choices. Apremilast has been associated with early gastrointestinal tract side effects that tend to resolve over time. Each biologic has a unique safety profile, with a rare incidence of side effects that should be reviewed carefully with any prospective patients before starting therapy.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

It is important to reinforce gentle hand care and foot care. Patients need to understand that lack of compliance with treatment will lead to recurrence of disease.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

I try to educate them as best as possible, and ask them to return and reconsider therapy if they find that this condition affects their quality of life.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Patients with this condition need to avoid friction and excessive moisture. They should be counseled to use gloves for excessive wet work. I recommend they use cotton gloves on the hands, and then cover those with rubber gloves. Patients should use a hand emollient regularly, including after each time they wash their hands or have exposure to water. If the patient lifts weights, I recommend he/she use weight-lifting gloves to reduce friction.

What are your go to treatments? What are the side effects?

The first line of therapy for hand and foot psoriasis is a topical agent. I most often use a combination of topical steroids and a topical vitamin D analogue. If insurance is amenable, I may use a fixed combination of topical steroid and vitamin D analogue.

If topical therapies are not successful, I often consider using excimer laser therapy, which requires the patient to come to the office twice weekly, so it is important to determine if this therapy is compatible with the patient's schedule. Other options include oral and biological therapies. Apremilast is a reasonable first-line systemic therapy given that it is an oral therapy, requires no laboratory monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile. Alternatively, biologic agents can be utilized. There are several analyses available looking at the efficacy of different biologics in hand and foot psoriasis, but at this point there is no consensus first choice for a biologic in this condition. Many available biologics may have a notable impact though.

The side effects of therapies for psoriasis are well established. Topical therapies and excimer laser are relatively safe choices. Apremilast has been associated with early gastrointestinal tract side effects that tend to resolve over time. Each biologic has a unique safety profile, with a rare incidence of side effects that should be reviewed carefully with any prospective patients before starting therapy.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

It is important to reinforce gentle hand care and foot care. Patients need to understand that lack of compliance with treatment will lead to recurrence of disease.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

I try to educate them as best as possible, and ask them to return and reconsider therapy if they find that this condition affects their quality of life.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

Patients with this condition need to avoid friction and excessive moisture. They should be counseled to use gloves for excessive wet work. I recommend they use cotton gloves on the hands, and then cover those with rubber gloves. Patients should use a hand emollient regularly, including after each time they wash their hands or have exposure to water. If the patient lifts weights, I recommend he/she use weight-lifting gloves to reduce friction.

What are your go to treatments? What are the side effects?

The first line of therapy for hand and foot psoriasis is a topical agent. I most often use a combination of topical steroids and a topical vitamin D analogue. If insurance is amenable, I may use a fixed combination of topical steroid and vitamin D analogue.

If topical therapies are not successful, I often consider using excimer laser therapy, which requires the patient to come to the office twice weekly, so it is important to determine if this therapy is compatible with the patient's schedule. Other options include oral and biological therapies. Apremilast is a reasonable first-line systemic therapy given that it is an oral therapy, requires no laboratory monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile. Alternatively, biologic agents can be utilized. There are several analyses available looking at the efficacy of different biologics in hand and foot psoriasis, but at this point there is no consensus first choice for a biologic in this condition. Many available biologics may have a notable impact though.

The side effects of therapies for psoriasis are well established. Topical therapies and excimer laser are relatively safe choices. Apremilast has been associated with early gastrointestinal tract side effects that tend to resolve over time. Each biologic has a unique safety profile, with a rare incidence of side effects that should be reviewed carefully with any prospective patients before starting therapy.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

It is important to reinforce gentle hand care and foot care. Patients need to understand that lack of compliance with treatment will lead to recurrence of disease.

What do you do if patients refuse treatment?

I try to educate them as best as possible, and ask them to return and reconsider therapy if they find that this condition affects their quality of life.

Genital Wart Treatment

What does your patient need to know?

When a patient presents with a history of genital warts (GWs), find out when and where the lesions started; where the lesions are currently located; what new lesions have developed; what treatments have been administered (eg, physician applied, prescription) and which one(s) worked; what side effects to treatments have been experienced and at what dose; does a partner(s) have similar lesions; is there a history of other sexually transmitted diseases or genital cancer; is he/she immunocompromised (eg, human immunodeficiency virus, transplant, medications); and what is his/her sexual orientation.

Once all of the information has been gathered and the entire anogenital region has been examined, a treatment plan can be formulated. If the patient is immunocompromised or is a man who has sex with men, the risk for anogenital malignancy due to human papillomavirus (HPV) is higher, and GWs, which can be coinfected with oncogenic HPV types, should be treated more aggressively. If the patient is still getting new lesions, use of only a destructive method such as cryotherapy will likely lead to suboptimal results.

Any patients with GWs in the anal region but particularly those in high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients should have an anoscopy to evaluate for lesions on the anal mucosa and in the rectum.

What are your go-to treatments?

Prior treatments need to be taken into account; make sure to understand any side effects and how he/she applied the prior treatment before eliminating it as a viable option. Treatment usually depends on the number of lesions, surface area, anatomic locations involved, and size of the lesions. I start with a 2-pronged approach—a debulking therapy and a patient-applied topical therapy—which allows me to physically remove some of the lesions, typically the larger ones, and then have the patient apply a topical medication at home that will treat the smaller lesions as well as help to clear or decrease the burden of HPV virus on the skin. I use cryotherapy as a debulking agent, but curettage or podophyllin 25% also can be used in the office. I use imiquimod cream 5% as a first-line topical agent at the recommended dose of 3 times weekly; however, if after the first 2 weeks the patient has little response or too much irritation, I titrate the dose so that the patient has mild inflammation on the skin. The dose ultimately can range from daily to once weekly. Some patients who can only tolerate imiquimod once or twice weekly may require zinc oxide paste for the inguinal folds and scrotum to protect from irritation. Alternate topical medications for GWs include sinecatechins ointment 15% or cidofovir ointment 2%.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Start the visit with open communication about the disease, where it came from, what the risks are if it is not treated, and how we can best treat it to make sure we minimize those risks. I explain all of the treatment options as well as our role in treating these lesions and minimizing the risk for disease progression.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Most patients with GWs are motivated to be treated. If pain is a concern, such as with cryotherapy, I recommend topical treatments.

What patient resources do you recommend?

The American Academy of Dermatology (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/genital-warts), Harvard Medical School patient education center (Boston, Massachusetts)(http://www.patienteducationcenter.org/articles/genital-warts/), and American Family Physician (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/1215/p2345.html) provide patient materials that I recommend.

What does your patient need to know?

When a patient presents with a history of genital warts (GWs), find out when and where the lesions started; where the lesions are currently located; what new lesions have developed; what treatments have been administered (eg, physician applied, prescription) and which one(s) worked; what side effects to treatments have been experienced and at what dose; does a partner(s) have similar lesions; is there a history of other sexually transmitted diseases or genital cancer; is he/she immunocompromised (eg, human immunodeficiency virus, transplant, medications); and what is his/her sexual orientation.

Once all of the information has been gathered and the entire anogenital region has been examined, a treatment plan can be formulated. If the patient is immunocompromised or is a man who has sex with men, the risk for anogenital malignancy due to human papillomavirus (HPV) is higher, and GWs, which can be coinfected with oncogenic HPV types, should be treated more aggressively. If the patient is still getting new lesions, use of only a destructive method such as cryotherapy will likely lead to suboptimal results.

Any patients with GWs in the anal region but particularly those in high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients should have an anoscopy to evaluate for lesions on the anal mucosa and in the rectum.

What are your go-to treatments?

Prior treatments need to be taken into account; make sure to understand any side effects and how he/she applied the prior treatment before eliminating it as a viable option. Treatment usually depends on the number of lesions, surface area, anatomic locations involved, and size of the lesions. I start with a 2-pronged approach—a debulking therapy and a patient-applied topical therapy—which allows me to physically remove some of the lesions, typically the larger ones, and then have the patient apply a topical medication at home that will treat the smaller lesions as well as help to clear or decrease the burden of HPV virus on the skin. I use cryotherapy as a debulking agent, but curettage or podophyllin 25% also can be used in the office. I use imiquimod cream 5% as a first-line topical agent at the recommended dose of 3 times weekly; however, if after the first 2 weeks the patient has little response or too much irritation, I titrate the dose so that the patient has mild inflammation on the skin. The dose ultimately can range from daily to once weekly. Some patients who can only tolerate imiquimod once or twice weekly may require zinc oxide paste for the inguinal folds and scrotum to protect from irritation. Alternate topical medications for GWs include sinecatechins ointment 15% or cidofovir ointment 2%.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Start the visit with open communication about the disease, where it came from, what the risks are if it is not treated, and how we can best treat it to make sure we minimize those risks. I explain all of the treatment options as well as our role in treating these lesions and minimizing the risk for disease progression.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Most patients with GWs are motivated to be treated. If pain is a concern, such as with cryotherapy, I recommend topical treatments.

What patient resources do you recommend?

The American Academy of Dermatology (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/genital-warts), Harvard Medical School patient education center (Boston, Massachusetts)(http://www.patienteducationcenter.org/articles/genital-warts/), and American Family Physician (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/1215/p2345.html) provide patient materials that I recommend.

What does your patient need to know?

When a patient presents with a history of genital warts (GWs), find out when and where the lesions started; where the lesions are currently located; what new lesions have developed; what treatments have been administered (eg, physician applied, prescription) and which one(s) worked; what side effects to treatments have been experienced and at what dose; does a partner(s) have similar lesions; is there a history of other sexually transmitted diseases or genital cancer; is he/she immunocompromised (eg, human immunodeficiency virus, transplant, medications); and what is his/her sexual orientation.

Once all of the information has been gathered and the entire anogenital region has been examined, a treatment plan can be formulated. If the patient is immunocompromised or is a man who has sex with men, the risk for anogenital malignancy due to human papillomavirus (HPV) is higher, and GWs, which can be coinfected with oncogenic HPV types, should be treated more aggressively. If the patient is still getting new lesions, use of only a destructive method such as cryotherapy will likely lead to suboptimal results.

Any patients with GWs in the anal region but particularly those in high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients should have an anoscopy to evaluate for lesions on the anal mucosa and in the rectum.

What are your go-to treatments?

Prior treatments need to be taken into account; make sure to understand any side effects and how he/she applied the prior treatment before eliminating it as a viable option. Treatment usually depends on the number of lesions, surface area, anatomic locations involved, and size of the lesions. I start with a 2-pronged approach—a debulking therapy and a patient-applied topical therapy—which allows me to physically remove some of the lesions, typically the larger ones, and then have the patient apply a topical medication at home that will treat the smaller lesions as well as help to clear or decrease the burden of HPV virus on the skin. I use cryotherapy as a debulking agent, but curettage or podophyllin 25% also can be used in the office. I use imiquimod cream 5% as a first-line topical agent at the recommended dose of 3 times weekly; however, if after the first 2 weeks the patient has little response or too much irritation, I titrate the dose so that the patient has mild inflammation on the skin. The dose ultimately can range from daily to once weekly. Some patients who can only tolerate imiquimod once or twice weekly may require zinc oxide paste for the inguinal folds and scrotum to protect from irritation. Alternate topical medications for GWs include sinecatechins ointment 15% or cidofovir ointment 2%.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Start the visit with open communication about the disease, where it came from, what the risks are if it is not treated, and how we can best treat it to make sure we minimize those risks. I explain all of the treatment options as well as our role in treating these lesions and minimizing the risk for disease progression.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Most patients with GWs are motivated to be treated. If pain is a concern, such as with cryotherapy, I recommend topical treatments.

What patient resources do you recommend?

The American Academy of Dermatology (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/genital-warts), Harvard Medical School patient education center (Boston, Massachusetts)(http://www.patienteducationcenter.org/articles/genital-warts/), and American Family Physician (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/1215/p2345.html) provide patient materials that I recommend.

Clinical Pearl: Early Diagnosis of Nail Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis

Practice Gap

Early diagnosis of nail psoriasis is challenging because nail changes, including pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, crumbling, oil spots, salmon patches, onycholysis, and splinter hemorrhages, may be subtle and nonspecific. Furthermore, 5% to 10% of psoriasis patients do not have skin findings, making the diagnosis of nail psoriasis even more difficult. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is more common in patients with nail psoriasis than in those with cutaneous psoriasis, and early joint damage may be asymptomatic.1 Both nail psoriasis and PsA may progress rapidly, leading to functional impairment with poor quality of life.2

Diagnostic Tool

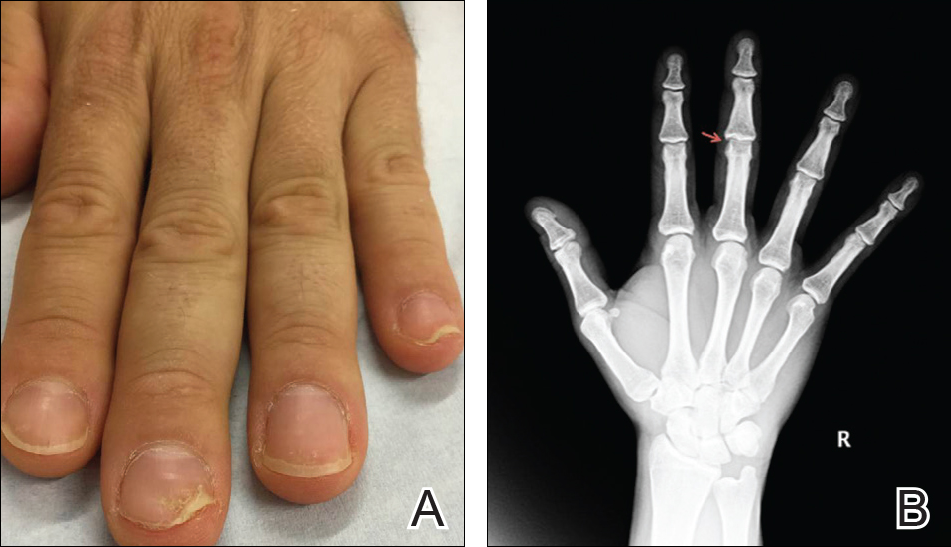

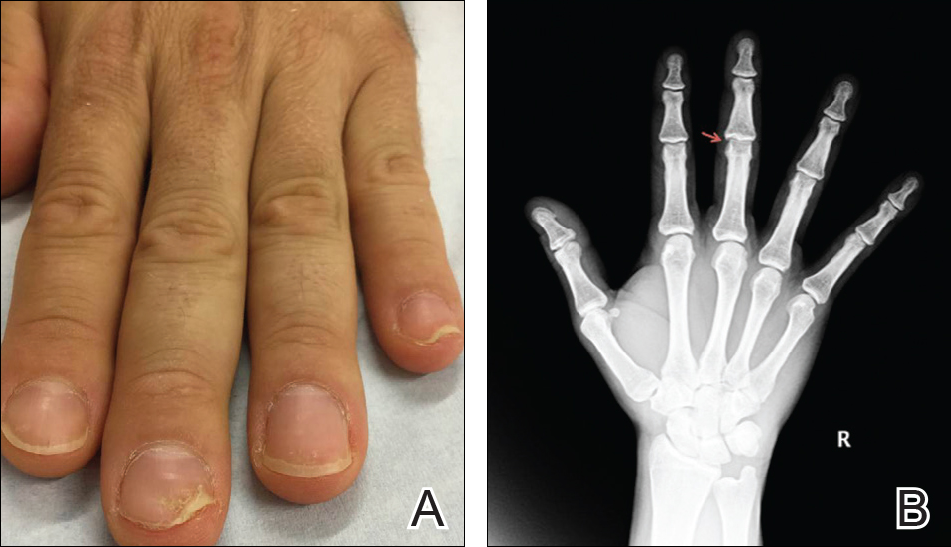

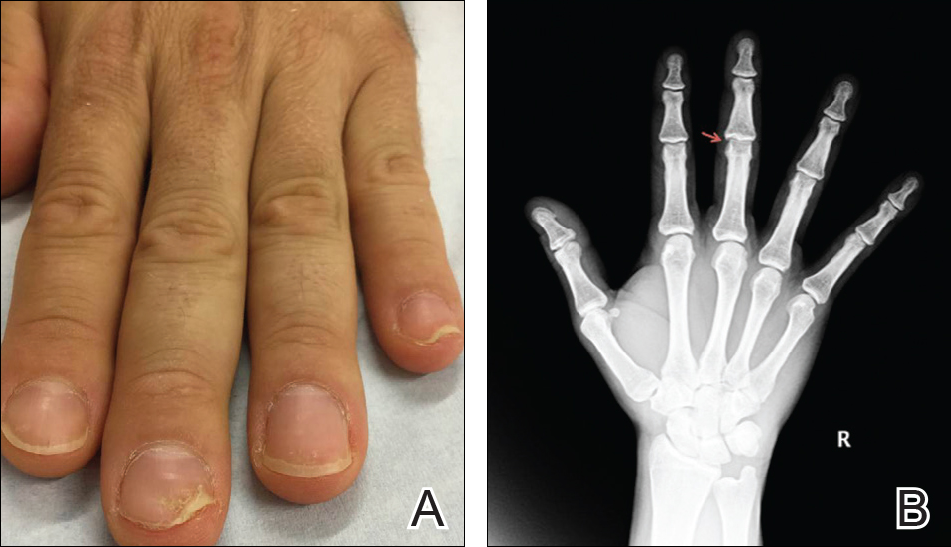

A 36-year-old man presented with a 4-year history of abnormal fingernails. He denied nail pain but stated that the nails felt sensitive at times and it was difficult to pick up small objects. His medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and attention deficit disorder. He denied joint pain or skin rash.

Physical examination revealed pitting and onycholysis of the fingernails (Figure, A) without involvement of the toenails. A nail clipping was negative for fungus but revealed an incompletely keratinized nail plate with subungual parakeratotic scale, consistent with nail psoriasis. A radiograph showed erosive changes of the third finger of the right hand that were compatible with PsA (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

A nail clipping may be performed to diagnose nail psoriasis. Imaging and/or referral to a rheumatologist should be performed in all patients with isolated nail psoriasis to evaluate for early arthritic changes. If present, appropriate therapy is initiated to prevent further joint damage. In patients with nail psoriasis with or without associated joint pain, dermatologists should consider using radiograph imaging to screen patients for PsA.

- 1. Balestri R, Rech G, Rossi E, et al. Natural history of isolated nail psoriasis and its role as a risk factor for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a single center cross sectional study [published online September 2, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15026.

- Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis, the unknown burden of disease [published online January 15, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1690-1695.

Practice Gap

Early diagnosis of nail psoriasis is challenging because nail changes, including pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, crumbling, oil spots, salmon patches, onycholysis, and splinter hemorrhages, may be subtle and nonspecific. Furthermore, 5% to 10% of psoriasis patients do not have skin findings, making the diagnosis of nail psoriasis even more difficult. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is more common in patients with nail psoriasis than in those with cutaneous psoriasis, and early joint damage may be asymptomatic.1 Both nail psoriasis and PsA may progress rapidly, leading to functional impairment with poor quality of life.2

Diagnostic Tool

A 36-year-old man presented with a 4-year history of abnormal fingernails. He denied nail pain but stated that the nails felt sensitive at times and it was difficult to pick up small objects. His medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and attention deficit disorder. He denied joint pain or skin rash.

Physical examination revealed pitting and onycholysis of the fingernails (Figure, A) without involvement of the toenails. A nail clipping was negative for fungus but revealed an incompletely keratinized nail plate with subungual parakeratotic scale, consistent with nail psoriasis. A radiograph showed erosive changes of the third finger of the right hand that were compatible with PsA (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

A nail clipping may be performed to diagnose nail psoriasis. Imaging and/or referral to a rheumatologist should be performed in all patients with isolated nail psoriasis to evaluate for early arthritic changes. If present, appropriate therapy is initiated to prevent further joint damage. In patients with nail psoriasis with or without associated joint pain, dermatologists should consider using radiograph imaging to screen patients for PsA.

Practice Gap

Early diagnosis of nail psoriasis is challenging because nail changes, including pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, crumbling, oil spots, salmon patches, onycholysis, and splinter hemorrhages, may be subtle and nonspecific. Furthermore, 5% to 10% of psoriasis patients do not have skin findings, making the diagnosis of nail psoriasis even more difficult. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is more common in patients with nail psoriasis than in those with cutaneous psoriasis, and early joint damage may be asymptomatic.1 Both nail psoriasis and PsA may progress rapidly, leading to functional impairment with poor quality of life.2

Diagnostic Tool

A 36-year-old man presented with a 4-year history of abnormal fingernails. He denied nail pain but stated that the nails felt sensitive at times and it was difficult to pick up small objects. His medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and attention deficit disorder. He denied joint pain or skin rash.

Physical examination revealed pitting and onycholysis of the fingernails (Figure, A) without involvement of the toenails. A nail clipping was negative for fungus but revealed an incompletely keratinized nail plate with subungual parakeratotic scale, consistent with nail psoriasis. A radiograph showed erosive changes of the third finger of the right hand that were compatible with PsA (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

A nail clipping may be performed to diagnose nail psoriasis. Imaging and/or referral to a rheumatologist should be performed in all patients with isolated nail psoriasis to evaluate for early arthritic changes. If present, appropriate therapy is initiated to prevent further joint damage. In patients with nail psoriasis with or without associated joint pain, dermatologists should consider using radiograph imaging to screen patients for PsA.

- 1. Balestri R, Rech G, Rossi E, et al. Natural history of isolated nail psoriasis and its role as a risk factor for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a single center cross sectional study [published online September 2, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15026.

- Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis, the unknown burden of disease [published online January 15, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1690-1695.

- 1. Balestri R, Rech G, Rossi E, et al. Natural history of isolated nail psoriasis and its role as a risk factor for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a single center cross sectional study [published online September 2, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15026.

- Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis, the unknown burden of disease [published online January 15, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1690-1695.

Spot Psoriatic Arthritis Early in Psoriasis Patients

How does psoriatic arthritis present?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) can present in psoriasis patients with an average latency of approximately 10 years. In patients with a strong genetic predisposition, another more severe form of PsA can present earlier in life (<20 years of age). Although PsA generally is classified as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy, more than 10% of patients may in fact be rheumatoid factor-positive. Nail pitting is a feature that can suggest the possibility of PsA, present in almost 90% of patients with PsA.

Who should treat PsA?

Although involving our colleagues in rheumatology is usually beneficial for our patients, in most cases dermatologists can and should effectively manage the care of PsA. The immunology of PsA is the same as psoriasis, which contrasts with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Although active human immunodeficiency virus infection can trigger widespread psoriasis and PsA, RA conversely improves with the depletion of CD4+ cells. Methotrexate, which is used cavalierly by rheumatologists for RA, has a different effect in psoriasis; liver damage is 3 times as likely in psoriasis versus RA at the same doses, while cirrhosis without transaminitis is much more likely with psoriasis patients. Thus, a dermatologist's experience with using systemic medications to treat psoriasis is paramount in successful treatment of PsA.

What medications can we use to treat PsA?

Because halting the progression of PsA is the key to limiting long-term sequelae, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Treatment options range from methotrexate to most of the newer biologics. Acitretin tends to be ineffective. Apremilast is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors also have demonstrated efficacy in PsA trials. There are some biologics that are used for PsA but do not have an approval for psoriasis, such as certolizumab pegol.

What's new in PsA?

The literature is well established in the classic progression and presentation of PsA, but there is new evidence that the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms, such as joint pain, arthralgia, fatigue, heel pain, and stiffness (Eder et al). The presence of these symptoms may help guide focused questioning and examination.

Another recent study has shown that the incidence of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are more likely in patients with PsA (Zohar et al). It is another important consideration for our patients, especially with recent concerns regarding onset of inflammatory bowel disease with some of the newer biologics we may use to treat psoriasis.

As newer classes of biologic treatments emerge, it will be interesting to see how effective they are in treating PsA in addition to plaque psoriasis. We should be aggressive about treating our patients with psoriasis using systemic therapy if they develop joint pain.

Suggested Readings

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study [published online October 28, 2016]. Arthritis Rheumatol. doi:10.1002/art.39973.

Zohar A, Cohen AD, Bitterman H, et al. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis [published online August 17, 2016]. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2679-2684.

How does psoriatic arthritis present?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) can present in psoriasis patients with an average latency of approximately 10 years. In patients with a strong genetic predisposition, another more severe form of PsA can present earlier in life (<20 years of age). Although PsA generally is classified as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy, more than 10% of patients may in fact be rheumatoid factor-positive. Nail pitting is a feature that can suggest the possibility of PsA, present in almost 90% of patients with PsA.

Who should treat PsA?

Although involving our colleagues in rheumatology is usually beneficial for our patients, in most cases dermatologists can and should effectively manage the care of PsA. The immunology of PsA is the same as psoriasis, which contrasts with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Although active human immunodeficiency virus infection can trigger widespread psoriasis and PsA, RA conversely improves with the depletion of CD4+ cells. Methotrexate, which is used cavalierly by rheumatologists for RA, has a different effect in psoriasis; liver damage is 3 times as likely in psoriasis versus RA at the same doses, while cirrhosis without transaminitis is much more likely with psoriasis patients. Thus, a dermatologist's experience with using systemic medications to treat psoriasis is paramount in successful treatment of PsA.

What medications can we use to treat PsA?

Because halting the progression of PsA is the key to limiting long-term sequelae, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Treatment options range from methotrexate to most of the newer biologics. Acitretin tends to be ineffective. Apremilast is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors also have demonstrated efficacy in PsA trials. There are some biologics that are used for PsA but do not have an approval for psoriasis, such as certolizumab pegol.

What's new in PsA?

The literature is well established in the classic progression and presentation of PsA, but there is new evidence that the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms, such as joint pain, arthralgia, fatigue, heel pain, and stiffness (Eder et al). The presence of these symptoms may help guide focused questioning and examination.

Another recent study has shown that the incidence of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are more likely in patients with PsA (Zohar et al). It is another important consideration for our patients, especially with recent concerns regarding onset of inflammatory bowel disease with some of the newer biologics we may use to treat psoriasis.

As newer classes of biologic treatments emerge, it will be interesting to see how effective they are in treating PsA in addition to plaque psoriasis. We should be aggressive about treating our patients with psoriasis using systemic therapy if they develop joint pain.

Suggested Readings

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study [published online October 28, 2016]. Arthritis Rheumatol. doi:10.1002/art.39973.

Zohar A, Cohen AD, Bitterman H, et al. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis [published online August 17, 2016]. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2679-2684.

How does psoriatic arthritis present?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) can present in psoriasis patients with an average latency of approximately 10 years. In patients with a strong genetic predisposition, another more severe form of PsA can present earlier in life (<20 years of age). Although PsA generally is classified as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy, more than 10% of patients may in fact be rheumatoid factor-positive. Nail pitting is a feature that can suggest the possibility of PsA, present in almost 90% of patients with PsA.

Who should treat PsA?

Although involving our colleagues in rheumatology is usually beneficial for our patients, in most cases dermatologists can and should effectively manage the care of PsA. The immunology of PsA is the same as psoriasis, which contrasts with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Although active human immunodeficiency virus infection can trigger widespread psoriasis and PsA, RA conversely improves with the depletion of CD4+ cells. Methotrexate, which is used cavalierly by rheumatologists for RA, has a different effect in psoriasis; liver damage is 3 times as likely in psoriasis versus RA at the same doses, while cirrhosis without transaminitis is much more likely with psoriasis patients. Thus, a dermatologist's experience with using systemic medications to treat psoriasis is paramount in successful treatment of PsA.

What medications can we use to treat PsA?

Because halting the progression of PsA is the key to limiting long-term sequelae, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Treatment options range from methotrexate to most of the newer biologics. Acitretin tends to be ineffective. Apremilast is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors also have demonstrated efficacy in PsA trials. There are some biologics that are used for PsA but do not have an approval for psoriasis, such as certolizumab pegol.

What's new in PsA?

The literature is well established in the classic progression and presentation of PsA, but there is new evidence that the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms, such as joint pain, arthralgia, fatigue, heel pain, and stiffness (Eder et al). The presence of these symptoms may help guide focused questioning and examination.

Another recent study has shown that the incidence of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are more likely in patients with PsA (Zohar et al). It is another important consideration for our patients, especially with recent concerns regarding onset of inflammatory bowel disease with some of the newer biologics we may use to treat psoriasis.

As newer classes of biologic treatments emerge, it will be interesting to see how effective they are in treating PsA in addition to plaque psoriasis. We should be aggressive about treating our patients with psoriasis using systemic therapy if they develop joint pain.

Suggested Readings

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study [published online October 28, 2016]. Arthritis Rheumatol. doi:10.1002/art.39973.

Zohar A, Cohen AD, Bitterman H, et al. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis [published online August 17, 2016]. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2679-2684.

Proper Wound Management: How to Work With Patients

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.