User login

Painful nail with longitudinal erythronychia

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

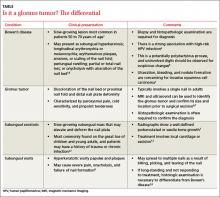

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

Chronic headaches

The family physician (FP) recognized the papilledema on funduscopic exam and ordered a lumbar puncture, which led to a diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. (A brain MRI was also ordered, but it showed no mass or hydrocephalus.)

The term papilledema refers specifically to optic disc swelling related to increased intracranial pressure. When no localizing neurologic signs or space-occupying lesion is present, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is likely the cause in patients younger than age 45 years—especially obese women. Patients with IIH usually present with daily pulsatile headaches with nausea, and often have transient visual disturbances and/or pulsatile tinnitus. Patients often report hearing a “whooshing” sound. Bilateral papilledema and visual field defects on a perimetry test are found in almost all patients. Elevated opening pressure on lumbar puncture is required for the diagnosis.

In many cases, IIH is self-limiting, presents without visual symptoms, and will resolve over several years without loss of vision. However, when patients present with persistent or worsening visual disturbances, treatment is required to lower the intracranial pressure to prevent optic nerve damage and irreversible loss of vision. Management of the headache is a key factor when choosing a therapeutic plan. Management includes the following:

Nonpharmacologic options

- careful observation—often by an ophthalmologist—with documentation of any visual changes (formal visual field testing is indicated).

- weight loss of 15% of body weight is beneficial, but will not decrease intracranial pressure quickly enough if visual compromise is present.

Medications

- acetazolamide 1000 to 2000 mg/day; early studies indicate that topiramate may also be effective; other diuretics such as furosemide are less effective.

- high-dose corticosteroids for short periods for rare cases of rapidly advancing vision loss.

In this case, the patient was started on acetazolamide and joined a weight-loss program. Her symptoms resolved over the course of 18 months.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Paul D. Comeau. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Papilledema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:151-154.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) recognized the papilledema on funduscopic exam and ordered a lumbar puncture, which led to a diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. (A brain MRI was also ordered, but it showed no mass or hydrocephalus.)

The term papilledema refers specifically to optic disc swelling related to increased intracranial pressure. When no localizing neurologic signs or space-occupying lesion is present, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is likely the cause in patients younger than age 45 years—especially obese women. Patients with IIH usually present with daily pulsatile headaches with nausea, and often have transient visual disturbances and/or pulsatile tinnitus. Patients often report hearing a “whooshing” sound. Bilateral papilledema and visual field defects on a perimetry test are found in almost all patients. Elevated opening pressure on lumbar puncture is required for the diagnosis.

In many cases, IIH is self-limiting, presents without visual symptoms, and will resolve over several years without loss of vision. However, when patients present with persistent or worsening visual disturbances, treatment is required to lower the intracranial pressure to prevent optic nerve damage and irreversible loss of vision. Management of the headache is a key factor when choosing a therapeutic plan. Management includes the following:

Nonpharmacologic options

- careful observation—often by an ophthalmologist—with documentation of any visual changes (formal visual field testing is indicated).

- weight loss of 15% of body weight is beneficial, but will not decrease intracranial pressure quickly enough if visual compromise is present.

Medications

- acetazolamide 1000 to 2000 mg/day; early studies indicate that topiramate may also be effective; other diuretics such as furosemide are less effective.

- high-dose corticosteroids for short periods for rare cases of rapidly advancing vision loss.

In this case, the patient was started on acetazolamide and joined a weight-loss program. Her symptoms resolved over the course of 18 months.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Paul D. Comeau. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Papilledema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:151-154.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) recognized the papilledema on funduscopic exam and ordered a lumbar puncture, which led to a diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. (A brain MRI was also ordered, but it showed no mass or hydrocephalus.)

The term papilledema refers specifically to optic disc swelling related to increased intracranial pressure. When no localizing neurologic signs or space-occupying lesion is present, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is likely the cause in patients younger than age 45 years—especially obese women. Patients with IIH usually present with daily pulsatile headaches with nausea, and often have transient visual disturbances and/or pulsatile tinnitus. Patients often report hearing a “whooshing” sound. Bilateral papilledema and visual field defects on a perimetry test are found in almost all patients. Elevated opening pressure on lumbar puncture is required for the diagnosis.

In many cases, IIH is self-limiting, presents without visual symptoms, and will resolve over several years without loss of vision. However, when patients present with persistent or worsening visual disturbances, treatment is required to lower the intracranial pressure to prevent optic nerve damage and irreversible loss of vision. Management of the headache is a key factor when choosing a therapeutic plan. Management includes the following:

Nonpharmacologic options

- careful observation—often by an ophthalmologist—with documentation of any visual changes (formal visual field testing is indicated).

- weight loss of 15% of body weight is beneficial, but will not decrease intracranial pressure quickly enough if visual compromise is present.

Medications

- acetazolamide 1000 to 2000 mg/day; early studies indicate that topiramate may also be effective; other diuretics such as furosemide are less effective.

- high-dose corticosteroids for short periods for rare cases of rapidly advancing vision loss.

In this case, the patient was started on acetazolamide and joined a weight-loss program. Her symptoms resolved over the course of 18 months.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Paul D. Comeau. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Papilledema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:151-154.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link:

Skin dimpling in a healthy newborn

A MOTHER BROUGHT HER 6-MONTH-OLD BOY in for a routine well-child check and asked that we look at a skin dimple in his right leg (FIGURE). The mother, who was a healthy 43-year-old, indicated that she hadn’t noticed the dimple until he was several weeks old, and since then it hadn’t changed significantly. She said that the dimple didn’t seem to bother him, and he was able to move all of his extremities without difficulty.

The baby was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and was discharged from the hospital at 2 days of age. He’d had no significant illnesses, all of his immunizations were up to date, and he’d been meeting all of his development milestones. There were no family members with similar findings.

The baby was developmentally appropriate for his age and his physical exam was unremarkable, including his neurological exam. The only significant finding was a 2-mm circular dimple on the lateral aspect of his proximal right leg.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Amniocentesis scar

Our patient had a classic skin dimple resulting from an inadvertent puncture during routine amniocentesis.

Amniocentesis is generally performed under real-time ultrasonography during the second trimester, when the fetus occupies approximately half of the amniotic cavity and the ratio of viable to nonviable cells in the amniotic fluid is greatest. It is typically performed on women of advanced maternal age (as was the case with our patient), who are at greater risk of delivering babies with genetic disorders. While amniocentesis is generally considered safe, complications—including puncture of placental and fetal vessels, peripheral nerve damage, fistula formation, pneumothorax, ocular trauma, and fetal death—have been reported.1

Scar formation from puncture of the fetus is estimated to occur in 1% to 3% of all amniocentesis procedures performed,2 although this may be an underestimation because the scars are often inconspicuous.3 The nonpigmented, depressed, dimplelike lesions generally measure 1 to 2 mm in diameter1 (although linear scars have also been reported4), and are not associated with any limitations in movement or underlying signs of injury. The chest, abdomen, back, and extremities are the most commonly affected sites.1

The main risk factors for needle puncture during amniocentesis are a history of repetitive needle insertion attempts and limited operator experience.2 Most lesions are present at birth, although others may become more evident as the infant gains weight and the scar retracts to form a dimple.5 The lesions are benign and require no further work-up.

Amniocentesis wasn’t performed? Time to look further

Most lesions caused by amniocentesis are present at birth, although others become more evident as the baby gains weight and the scar retracts to form a dimple. When assessing a newborn, the gluteal folds should be separated to look for any dimpling. Small “sacral dimples” that overlie the coccyx and have well-visualized, intact bases are considered benign normal variants and do not require further work-up.6,7 However, if there are multiple dimples, midline dimpling more than 2.5 cm from the anus, or dimples associated with excess hair, pigmentation, skin tags, or vascular anomalies, further evaluation (ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) and neurosurgical referral may be necessary to evaluate for a closed neural tube defect.8

Abnormalities that should be considered part of the differential for midline skin dimpling include:

- congenital dermal sinus tracts (remnants of incomplete neural tube closure during fetal development)

- diastematomyelia (a longitudinal split in the spinal cord, usually the result of an osseous or fibrous band that forms 2 hemicords)

- tethered spinal cord (an abnormal attachment of the cord to surrounding structures).8

Skin dimpling has also been reported in association with congenital rubella; in such cases, the dimples have been located on the patella and other bony prominences.9

Nothing to worry about

Our patient’s skin dimple was not along the spine, and the mother acknowledged having had amniocentesis during her pregnancy, so no further work-up was indicated. We simply reassured her that the dimple on her son’s leg was completely benign.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott Akin, MD, FAAFP,

1364 Clifton Road, NE, Box M-7, Atlanta, GA 30322

[email protected]

1. Raimer SS, Raimer BG. Needle puncture scars from midtrimester amniocentesis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1360-1362.

2. Epley SL, Hanson JW, Cruiksank DP. Fetal injury with midtrimester diagnostic amniocentesis. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:77-80.

3. Bruce S, Duffy JO, Wolf JE Jr. Skin dimpling associated with midtrimester amniocentesis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1984;2:140-142.

4. Broome DL, Wilson MG, Weiss B, et al. Needle puncture of fetus: a complication of second-trimester amniocentesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:247-252.

5. Ahluwalia J, Lowenstein E. Skin dimpling as a delayed manifestation of traumatic amniocentesis. Skinmed. 2005;4:323-324.

6. Ben-Sira L, Ponger P, Miller E, et al. Low-risk lumbar skin stigmata in infants: the role of ultrasound screening. J Pediatr. 2009;155:864-869.

7. Medina LS, Crone K, Kuntz KM. Newborns with suspected occult spinal dysraphism: a cost-effectiveness analysis of diagnostic strategies. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e101.

8. Zywicke HA, Rozzelle CJ. Sacral dimples. Pediatr Rev. 2011; 32:109-113.

9. Hammond K. Skin dimples and rubella. Pediatrics. 1967;39:291-292.

A MOTHER BROUGHT HER 6-MONTH-OLD BOY in for a routine well-child check and asked that we look at a skin dimple in his right leg (FIGURE). The mother, who was a healthy 43-year-old, indicated that she hadn’t noticed the dimple until he was several weeks old, and since then it hadn’t changed significantly. She said that the dimple didn’t seem to bother him, and he was able to move all of his extremities without difficulty.

The baby was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and was discharged from the hospital at 2 days of age. He’d had no significant illnesses, all of his immunizations were up to date, and he’d been meeting all of his development milestones. There were no family members with similar findings.

The baby was developmentally appropriate for his age and his physical exam was unremarkable, including his neurological exam. The only significant finding was a 2-mm circular dimple on the lateral aspect of his proximal right leg.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Amniocentesis scar

Our patient had a classic skin dimple resulting from an inadvertent puncture during routine amniocentesis.

Amniocentesis is generally performed under real-time ultrasonography during the second trimester, when the fetus occupies approximately half of the amniotic cavity and the ratio of viable to nonviable cells in the amniotic fluid is greatest. It is typically performed on women of advanced maternal age (as was the case with our patient), who are at greater risk of delivering babies with genetic disorders. While amniocentesis is generally considered safe, complications—including puncture of placental and fetal vessels, peripheral nerve damage, fistula formation, pneumothorax, ocular trauma, and fetal death—have been reported.1

Scar formation from puncture of the fetus is estimated to occur in 1% to 3% of all amniocentesis procedures performed,2 although this may be an underestimation because the scars are often inconspicuous.3 The nonpigmented, depressed, dimplelike lesions generally measure 1 to 2 mm in diameter1 (although linear scars have also been reported4), and are not associated with any limitations in movement or underlying signs of injury. The chest, abdomen, back, and extremities are the most commonly affected sites.1

The main risk factors for needle puncture during amniocentesis are a history of repetitive needle insertion attempts and limited operator experience.2 Most lesions are present at birth, although others may become more evident as the infant gains weight and the scar retracts to form a dimple.5 The lesions are benign and require no further work-up.

Amniocentesis wasn’t performed? Time to look further

Most lesions caused by amniocentesis are present at birth, although others become more evident as the baby gains weight and the scar retracts to form a dimple. When assessing a newborn, the gluteal folds should be separated to look for any dimpling. Small “sacral dimples” that overlie the coccyx and have well-visualized, intact bases are considered benign normal variants and do not require further work-up.6,7 However, if there are multiple dimples, midline dimpling more than 2.5 cm from the anus, or dimples associated with excess hair, pigmentation, skin tags, or vascular anomalies, further evaluation (ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) and neurosurgical referral may be necessary to evaluate for a closed neural tube defect.8

Abnormalities that should be considered part of the differential for midline skin dimpling include:

- congenital dermal sinus tracts (remnants of incomplete neural tube closure during fetal development)

- diastematomyelia (a longitudinal split in the spinal cord, usually the result of an osseous or fibrous band that forms 2 hemicords)

- tethered spinal cord (an abnormal attachment of the cord to surrounding structures).8

Skin dimpling has also been reported in association with congenital rubella; in such cases, the dimples have been located on the patella and other bony prominences.9

Nothing to worry about

Our patient’s skin dimple was not along the spine, and the mother acknowledged having had amniocentesis during her pregnancy, so no further work-up was indicated. We simply reassured her that the dimple on her son’s leg was completely benign.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott Akin, MD, FAAFP,

1364 Clifton Road, NE, Box M-7, Atlanta, GA 30322

[email protected]

A MOTHER BROUGHT HER 6-MONTH-OLD BOY in for a routine well-child check and asked that we look at a skin dimple in his right leg (FIGURE). The mother, who was a healthy 43-year-old, indicated that she hadn’t noticed the dimple until he was several weeks old, and since then it hadn’t changed significantly. She said that the dimple didn’t seem to bother him, and he was able to move all of his extremities without difficulty.

The baby was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and was discharged from the hospital at 2 days of age. He’d had no significant illnesses, all of his immunizations were up to date, and he’d been meeting all of his development milestones. There were no family members with similar findings.

The baby was developmentally appropriate for his age and his physical exam was unremarkable, including his neurological exam. The only significant finding was a 2-mm circular dimple on the lateral aspect of his proximal right leg.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Amniocentesis scar

Our patient had a classic skin dimple resulting from an inadvertent puncture during routine amniocentesis.

Amniocentesis is generally performed under real-time ultrasonography during the second trimester, when the fetus occupies approximately half of the amniotic cavity and the ratio of viable to nonviable cells in the amniotic fluid is greatest. It is typically performed on women of advanced maternal age (as was the case with our patient), who are at greater risk of delivering babies with genetic disorders. While amniocentesis is generally considered safe, complications—including puncture of placental and fetal vessels, peripheral nerve damage, fistula formation, pneumothorax, ocular trauma, and fetal death—have been reported.1

Scar formation from puncture of the fetus is estimated to occur in 1% to 3% of all amniocentesis procedures performed,2 although this may be an underestimation because the scars are often inconspicuous.3 The nonpigmented, depressed, dimplelike lesions generally measure 1 to 2 mm in diameter1 (although linear scars have also been reported4), and are not associated with any limitations in movement or underlying signs of injury. The chest, abdomen, back, and extremities are the most commonly affected sites.1

The main risk factors for needle puncture during amniocentesis are a history of repetitive needle insertion attempts and limited operator experience.2 Most lesions are present at birth, although others may become more evident as the infant gains weight and the scar retracts to form a dimple.5 The lesions are benign and require no further work-up.

Amniocentesis wasn’t performed? Time to look further

Most lesions caused by amniocentesis are present at birth, although others become more evident as the baby gains weight and the scar retracts to form a dimple. When assessing a newborn, the gluteal folds should be separated to look for any dimpling. Small “sacral dimples” that overlie the coccyx and have well-visualized, intact bases are considered benign normal variants and do not require further work-up.6,7 However, if there are multiple dimples, midline dimpling more than 2.5 cm from the anus, or dimples associated with excess hair, pigmentation, skin tags, or vascular anomalies, further evaluation (ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) and neurosurgical referral may be necessary to evaluate for a closed neural tube defect.8

Abnormalities that should be considered part of the differential for midline skin dimpling include:

- congenital dermal sinus tracts (remnants of incomplete neural tube closure during fetal development)

- diastematomyelia (a longitudinal split in the spinal cord, usually the result of an osseous or fibrous band that forms 2 hemicords)

- tethered spinal cord (an abnormal attachment of the cord to surrounding structures).8

Skin dimpling has also been reported in association with congenital rubella; in such cases, the dimples have been located on the patella and other bony prominences.9

Nothing to worry about

Our patient’s skin dimple was not along the spine, and the mother acknowledged having had amniocentesis during her pregnancy, so no further work-up was indicated. We simply reassured her that the dimple on her son’s leg was completely benign.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott Akin, MD, FAAFP,

1364 Clifton Road, NE, Box M-7, Atlanta, GA 30322

[email protected]

1. Raimer SS, Raimer BG. Needle puncture scars from midtrimester amniocentesis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1360-1362.

2. Epley SL, Hanson JW, Cruiksank DP. Fetal injury with midtrimester diagnostic amniocentesis. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:77-80.

3. Bruce S, Duffy JO, Wolf JE Jr. Skin dimpling associated with midtrimester amniocentesis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1984;2:140-142.

4. Broome DL, Wilson MG, Weiss B, et al. Needle puncture of fetus: a complication of second-trimester amniocentesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:247-252.

5. Ahluwalia J, Lowenstein E. Skin dimpling as a delayed manifestation of traumatic amniocentesis. Skinmed. 2005;4:323-324.

6. Ben-Sira L, Ponger P, Miller E, et al. Low-risk lumbar skin stigmata in infants: the role of ultrasound screening. J Pediatr. 2009;155:864-869.

7. Medina LS, Crone K, Kuntz KM. Newborns with suspected occult spinal dysraphism: a cost-effectiveness analysis of diagnostic strategies. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e101.

8. Zywicke HA, Rozzelle CJ. Sacral dimples. Pediatr Rev. 2011; 32:109-113.

9. Hammond K. Skin dimples and rubella. Pediatrics. 1967;39:291-292.

1. Raimer SS, Raimer BG. Needle puncture scars from midtrimester amniocentesis. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1360-1362.

2. Epley SL, Hanson JW, Cruiksank DP. Fetal injury with midtrimester diagnostic amniocentesis. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:77-80.

3. Bruce S, Duffy JO, Wolf JE Jr. Skin dimpling associated with midtrimester amniocentesis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1984;2:140-142.

4. Broome DL, Wilson MG, Weiss B, et al. Needle puncture of fetus: a complication of second-trimester amniocentesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:247-252.

5. Ahluwalia J, Lowenstein E. Skin dimpling as a delayed manifestation of traumatic amniocentesis. Skinmed. 2005;4:323-324.

6. Ben-Sira L, Ponger P, Miller E, et al. Low-risk lumbar skin stigmata in infants: the role of ultrasound screening. J Pediatr. 2009;155:864-869.

7. Medina LS, Crone K, Kuntz KM. Newborns with suspected occult spinal dysraphism: a cost-effectiveness analysis of diagnostic strategies. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e101.

8. Zywicke HA, Rozzelle CJ. Sacral dimples. Pediatr Rev. 2011; 32:109-113.

9. Hammond K. Skin dimples and rubella. Pediatrics. 1967;39:291-292.

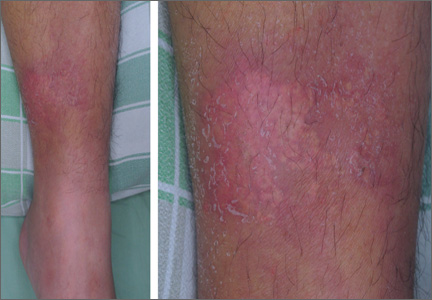

Erythematous plaque with yellowish papules on the shin

A 53-YEAR-OLD MAN with a 10-year history of poorly controlled hypertension was brought to our emergency department (ED) because he’d had a sudden loss of consciousness. The ED physicians discovered a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in his brainstem with fourth ventricle compression and immediately transferred him to the intensive care unit (ICU).

During the patient’s hospitalization, he was treated for ventilator-associated pneumonia and a gastric ulcer with cefepime 1 g IV 3 times daily and esomeprazole 40 mg/d IV via the long saphenous vein of his lower left leg. The patient subsequently developed acute renal failure with hyperkalemia and was treated with furosemide, glucose, and insulin. He also received parenteral calcium gluconate, also via the long saphenous vein in his left leg.

One week later, while still in the ICU, the patient developed an erythematous plaque with several firm yellowish papules on his lower left leg (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis

Calcinosis cutis is characterized by calcification of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is categorized into 5 major types based on the etiology: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, calciphylaxis, and iatrogenic.1 Calcification results from local tissue injury inducing alterations in collagen, subcutaneous fat, and elastic fibers. Typically, the ectopic calcification mass consists of amorphous calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite. Serum levels of calcium and phosphate in these patients are typically in the normal range.2

Iatrogenic calcification typically occurs in patients who have received IV calcium chloride or calcium gluconate therapy.2 When extravasation of calcium gluconate occurs, the venipuncture site can rapidly become tender, warm, and swollen, with erythema and whitish papuloplaques; in severe cases, signs of soft tissue necrosis or infection may also be seen.3 The lesions appear about 13 days after the infusion of calcium gluconate.4 Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the skin lesions appear.4

Not always obvious. Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis is easy to diagnose when a massive extravasation of calcium infusion is followed by tender, swollen whitish papuloplaques with surrounding erythema and skin necrosis.3 The diagnosis can be more challenging when the extravasation is not obvious. In such cases, a thorough history and careful exam will help distinguish it from 3 other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Distinguishing calcinosis cutis from these conditions

The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, eruptive xanthoma, and gouty tophus.

Patients with cellulitis will complain of areas of increased warmth, tenderness, redness, and swelling. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and tachycardia may also be present. Laboratory results will reveal leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels.Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the initial appearance of the skin lesions.

Eruptive xanthoma affects patients with hypertriglyceridemia with a sudden onset of monomorphous erythematous to yellowish papules over the buttocks, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. High serum triglyceride levels confirm this diagnosis.

In gouty tophus, hyperuricemia is a key risk factor. Patients initially present with extreme pain and swelling in a single joint—especially the first metacarpophalangeal. When left untreated, the pain and swelling may extend to the soft tissue of other articular joints and the auricular helix. Hard yellowish to whitish papulonodules with an erythematous halo may also appear. A histopathologic examination will reveal granulomatous inflammation surrounding yellow-brown urate crystals; in contrast, you will see deposits of blue calcium phosphate with calcinosis cutis.2

A conservative approach to treatmentThere is no consensus on the management of calcinosis cutis, although it is typically managed conservatively.5 Progressive clearing of the calcification often occurs spontaneously 2 to 3 months after onset, with no evidence of tissue calcification after 5 or 6 months.6 When calcinosis cutis is complicated by serious extravasation injuries, such as secondary infection or skin necrosis, debridement, drainage, or skin grafting may be needed.

Our patient’s road to recoveryOur patient was transferred to the respiratory care unit after he was stabilized. His lesions improved gradually, without any treatment. One month after being hospitalized, he was discharged to an assisted living facility.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan (ROC); [email protected]

1. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Calcifying disorders of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:693-706.

2. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Cutaneous mineralization and ossification. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill;2007:1293-1296.

3. Goldminz D, Barnhill R, McGuire J, et al. Calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium chloride. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:922-925.

4. Sonohata M, Akiyama T, Fujita I, et al. Neonate with calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium gluconate. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:269-272.

5. Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:15-22.

6. Ramamurthy RS, Harris V, Pildes RS. Subcutaneous calcium deposition in the neonate associated with intravenous administration of calcium gluconate. Pediatrics. 1975;55:802-806.

A 53-YEAR-OLD MAN with a 10-year history of poorly controlled hypertension was brought to our emergency department (ED) because he’d had a sudden loss of consciousness. The ED physicians discovered a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in his brainstem with fourth ventricle compression and immediately transferred him to the intensive care unit (ICU).

During the patient’s hospitalization, he was treated for ventilator-associated pneumonia and a gastric ulcer with cefepime 1 g IV 3 times daily and esomeprazole 40 mg/d IV via the long saphenous vein of his lower left leg. The patient subsequently developed acute renal failure with hyperkalemia and was treated with furosemide, glucose, and insulin. He also received parenteral calcium gluconate, also via the long saphenous vein in his left leg.

One week later, while still in the ICU, the patient developed an erythematous plaque with several firm yellowish papules on his lower left leg (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis

Calcinosis cutis is characterized by calcification of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is categorized into 5 major types based on the etiology: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, calciphylaxis, and iatrogenic.1 Calcification results from local tissue injury inducing alterations in collagen, subcutaneous fat, and elastic fibers. Typically, the ectopic calcification mass consists of amorphous calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite. Serum levels of calcium and phosphate in these patients are typically in the normal range.2

Iatrogenic calcification typically occurs in patients who have received IV calcium chloride or calcium gluconate therapy.2 When extravasation of calcium gluconate occurs, the venipuncture site can rapidly become tender, warm, and swollen, with erythema and whitish papuloplaques; in severe cases, signs of soft tissue necrosis or infection may also be seen.3 The lesions appear about 13 days after the infusion of calcium gluconate.4 Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the skin lesions appear.4

Not always obvious. Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis is easy to diagnose when a massive extravasation of calcium infusion is followed by tender, swollen whitish papuloplaques with surrounding erythema and skin necrosis.3 The diagnosis can be more challenging when the extravasation is not obvious. In such cases, a thorough history and careful exam will help distinguish it from 3 other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Distinguishing calcinosis cutis from these conditions

The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, eruptive xanthoma, and gouty tophus.

Patients with cellulitis will complain of areas of increased warmth, tenderness, redness, and swelling. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and tachycardia may also be present. Laboratory results will reveal leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels.Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the initial appearance of the skin lesions.

Eruptive xanthoma affects patients with hypertriglyceridemia with a sudden onset of monomorphous erythematous to yellowish papules over the buttocks, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. High serum triglyceride levels confirm this diagnosis.

In gouty tophus, hyperuricemia is a key risk factor. Patients initially present with extreme pain and swelling in a single joint—especially the first metacarpophalangeal. When left untreated, the pain and swelling may extend to the soft tissue of other articular joints and the auricular helix. Hard yellowish to whitish papulonodules with an erythematous halo may also appear. A histopathologic examination will reveal granulomatous inflammation surrounding yellow-brown urate crystals; in contrast, you will see deposits of blue calcium phosphate with calcinosis cutis.2

A conservative approach to treatmentThere is no consensus on the management of calcinosis cutis, although it is typically managed conservatively.5 Progressive clearing of the calcification often occurs spontaneously 2 to 3 months after onset, with no evidence of tissue calcification after 5 or 6 months.6 When calcinosis cutis is complicated by serious extravasation injuries, such as secondary infection or skin necrosis, debridement, drainage, or skin grafting may be needed.

Our patient’s road to recoveryOur patient was transferred to the respiratory care unit after he was stabilized. His lesions improved gradually, without any treatment. One month after being hospitalized, he was discharged to an assisted living facility.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan (ROC); [email protected]

A 53-YEAR-OLD MAN with a 10-year history of poorly controlled hypertension was brought to our emergency department (ED) because he’d had a sudden loss of consciousness. The ED physicians discovered a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in his brainstem with fourth ventricle compression and immediately transferred him to the intensive care unit (ICU).

During the patient’s hospitalization, he was treated for ventilator-associated pneumonia and a gastric ulcer with cefepime 1 g IV 3 times daily and esomeprazole 40 mg/d IV via the long saphenous vein of his lower left leg. The patient subsequently developed acute renal failure with hyperkalemia and was treated with furosemide, glucose, and insulin. He also received parenteral calcium gluconate, also via the long saphenous vein in his left leg.

One week later, while still in the ICU, the patient developed an erythematous plaque with several firm yellowish papules on his lower left leg (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis

Calcinosis cutis is characterized by calcification of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is categorized into 5 major types based on the etiology: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, calciphylaxis, and iatrogenic.1 Calcification results from local tissue injury inducing alterations in collagen, subcutaneous fat, and elastic fibers. Typically, the ectopic calcification mass consists of amorphous calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite. Serum levels of calcium and phosphate in these patients are typically in the normal range.2

Iatrogenic calcification typically occurs in patients who have received IV calcium chloride or calcium gluconate therapy.2 When extravasation of calcium gluconate occurs, the venipuncture site can rapidly become tender, warm, and swollen, with erythema and whitish papuloplaques; in severe cases, signs of soft tissue necrosis or infection may also be seen.3 The lesions appear about 13 days after the infusion of calcium gluconate.4 Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the skin lesions appear.4

Not always obvious. Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis is easy to diagnose when a massive extravasation of calcium infusion is followed by tender, swollen whitish papuloplaques with surrounding erythema and skin necrosis.3 The diagnosis can be more challenging when the extravasation is not obvious. In such cases, a thorough history and careful exam will help distinguish it from 3 other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Distinguishing calcinosis cutis from these conditions

The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, eruptive xanthoma, and gouty tophus.

Patients with cellulitis will complain of areas of increased warmth, tenderness, redness, and swelling. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and tachycardia may also be present. Laboratory results will reveal leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels.Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the initial appearance of the skin lesions.

Eruptive xanthoma affects patients with hypertriglyceridemia with a sudden onset of monomorphous erythematous to yellowish papules over the buttocks, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. High serum triglyceride levels confirm this diagnosis.

In gouty tophus, hyperuricemia is a key risk factor. Patients initially present with extreme pain and swelling in a single joint—especially the first metacarpophalangeal. When left untreated, the pain and swelling may extend to the soft tissue of other articular joints and the auricular helix. Hard yellowish to whitish papulonodules with an erythematous halo may also appear. A histopathologic examination will reveal granulomatous inflammation surrounding yellow-brown urate crystals; in contrast, you will see deposits of blue calcium phosphate with calcinosis cutis.2

A conservative approach to treatmentThere is no consensus on the management of calcinosis cutis, although it is typically managed conservatively.5 Progressive clearing of the calcification often occurs spontaneously 2 to 3 months after onset, with no evidence of tissue calcification after 5 or 6 months.6 When calcinosis cutis is complicated by serious extravasation injuries, such as secondary infection or skin necrosis, debridement, drainage, or skin grafting may be needed.

Our patient’s road to recoveryOur patient was transferred to the respiratory care unit after he was stabilized. His lesions improved gradually, without any treatment. One month after being hospitalized, he was discharged to an assisted living facility.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan (ROC); [email protected]

1. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Calcifying disorders of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:693-706.

2. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Cutaneous mineralization and ossification. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill;2007:1293-1296.

3. Goldminz D, Barnhill R, McGuire J, et al. Calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium chloride. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:922-925.

4. Sonohata M, Akiyama T, Fujita I, et al. Neonate with calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium gluconate. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:269-272.

5. Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:15-22.

6. Ramamurthy RS, Harris V, Pildes RS. Subcutaneous calcium deposition in the neonate associated with intravenous administration of calcium gluconate. Pediatrics. 1975;55:802-806.

1. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Calcifying disorders of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:693-706.

2. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Cutaneous mineralization and ossification. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill;2007:1293-1296.

3. Goldminz D, Barnhill R, McGuire J, et al. Calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium chloride. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:922-925.

4. Sonohata M, Akiyama T, Fujita I, et al. Neonate with calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium gluconate. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:269-272.

5. Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:15-22.

6. Ramamurthy RS, Harris V, Pildes RS. Subcutaneous calcium deposition in the neonate associated with intravenous administration of calcium gluconate. Pediatrics. 1975;55:802-806.

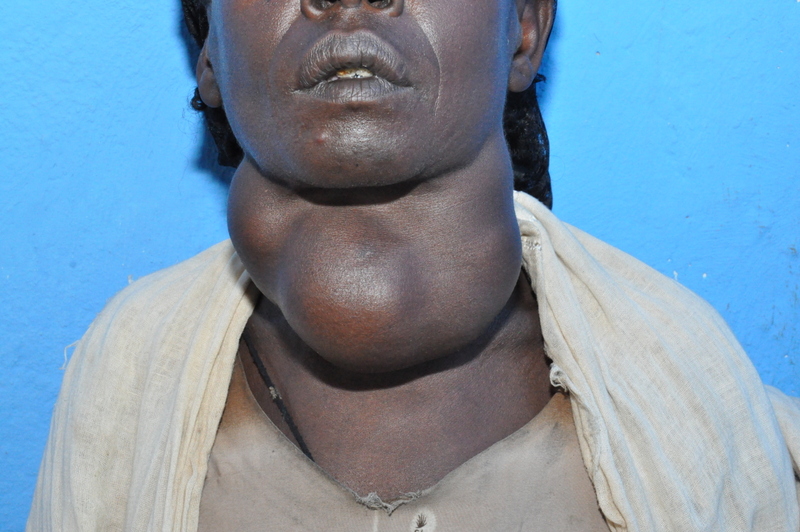

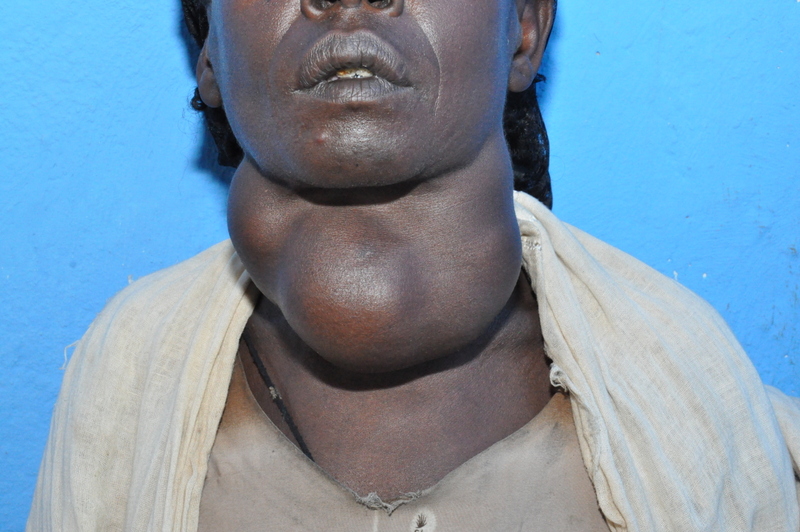

Unusual shoulder injury from a motorcycle crash

A 38-YEAR-OLD MAN was brought into our emergency department (ED) after driving his motorcycle at high speed into a tree. The patient, who hadn’t been wearing a helmet, was thrown 30 feet. When EMS arrived, the patient was unresponsive, with his right arm in the air. En route, the patient regained consciousness; he appeared intoxicated and became combative.

The patient was evaluated in the ED and his vital signs were normal. His right arm was abducted and over his head (FIGURE 1). He reported significant pain with palpation and attempts at range of motion. We were unable to place the patient’s arm at his side. Other than some minor abrasions, the patient appeared to have no other injuries.

FIGURE 1Right upper extremity on presentation

Routine laboratory tests showed an alcohol level of 0.175 g/dL and urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and tetrahydrocannabinol. A focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam was negative. We ordered a right shoulder x-ray and a chest x-ray.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Inferior dislocation of the shoulder

The right shoulder x-ray (FIGURE 2) revealed luxatio erecta—an inferior dislocation of the shoulder. The humeral head was displaced inferiorly with respect to the glenoid fossa and there was an associated greater tuberosity fracture. The chest x-ray demonstrated mild pulmonary contusions.

FIGURE 2

Right shoulder radiograph reveals luxatio erecta with greater tuberosity fracture

An uncommon dislocation

Inferior shoulder dislocation or luxatio erecta is the least common type of glenohumeral dislocation, comprising only about 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 The 2 other types of shoulder dislocations—anterior and posterior—account for 95% to 97% and 2% to 4% of dislocations, respectively.2

Injury occurs in one of 2 ways, either by a direct or indirect mechanism. A direct dislocation occurs when there is axial loading on an arm that is fully abducted at the shoulder.3 The indirect mechanism, which is more common, is caused by a hyperabduction stress that directs the humeral neck superiorly against the acromion process, forcing the humeral head out of the glenoid fossa inferiorly.2 The indirect mechanism usually occurs when a patient falls and reacts by grasping an object above his or her head, resulting in hyperabduction.

Sometimes, there is no trauma. True inferior dislocations have also been reported in patients with stroke, septic arthritis, and other neuromuscular diseases.4

The presentation is distinctive

Patients with this type of dislocation present with their arm elevated, elbow flexed, and hand behind their head. Due to mechanical entrapment of the humeral head, patients can’t move their arm. The abducted position of the arm may hinder further assessment with computed tomography (CT) for life-threatening injuries, as was the case with our patient.

While an immobile, abducted arm is virtually pathognomonic, radiographs are useful for confirming the diagnosis and assessing for associated fractures. It is essential to obtain anteroposterior, axillary, and Y views.5 Radiographs typically show the shaft of the humerus directed superiorly and parallel to the scapular spine, with the humeral head below the coracoid process or glenoid fossa.3,5

Rotator cuff tears are a common complication

There are a number of complications associated with luxatio erecta. Eighty percent of patients with this injury have either an associated rotator cuff tear or a fracture of the greater tuberosity (which we’ll get to in a bit).3 Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown rotator cuff injuries to involve the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and, less frequently, the subscapularis tendon.6 It’s believed that rotator cuff tears may be even more prevalent than reported in the literature since they are often underrecognized at the time of presentation with the dislocation.6

Other complications. Sixty percent of patients report some degree of neurologic dysfunction after the dislocation.5 The most common nerve affected is the axillary, followed by the radial, ulnar, and median nerves.3 These injuries are more likely to occur with associated fractures of the greater tuberosity or axillary artery injuries.7 Symptoms generally resolve after reduction, although there have been cases that have taken up to 6 weeks to resolve.8

Vascular compromise, most commonly occurring as a result of axillary artery injury, has been reported in 3.3% of cases.5 This injury is most common in elderly patients, with 75% of cases occurring in patients older than 60 years.7 It’s been hypothesized that this is due to the loss of arterial elasticity as an individual ages. The most common presenting signs and symptoms include absent radial and/or brachial pulses, severe pain, axillary swelling, axillary masses due to hematoma formation, and neurologic deficits.7 Complications are minimal if diagnosed and treated early.

The most expeditious way to diagnose this complication is to obtain a Doppler ultrasound of the injured extremity. If surgery is indicated, saphenous vein graft has been reported as a successful treatment.3

Fractures are another complication to watch for. The most common fractures are of the greater tuberosity, although fractures to the glenoid, humeral head, acromion, and scapular body have also been reported.8 Fracture management depends on the characteristics of the fracture, including displacement, size of the fragment, and joint stability.

Treatment involves traction and countertraction

Luxatio erecta is normally treated by closed reduction using the traction-countertraction technique. In this maneuver, the shoulder is reduced with direct traction, while countertraction is applied with a sheet wrapped over the clavicle on the affected side and pulled down and across the chest toward the unaffected side. The affected arm is pulled in a cephalad direction and further abducted until the humeral head is reduced within the glenoid fossa. After reduction, the arm is gradually moved downwards toward the patient’s side and splinted in the adducted position.8

Special care should be taken with patients who are at risk of cervical spine injuries. Postreduction radiographs should be obtained to verify proper humeral placement and to assess for any associated fractures. While closed reduction is the definitive treatment, patients run the risk of recurrent instability that may necessitate capsular reconstruction.1

Our patient recovered well

Our patient was sedated with fentanyl and midazolam, and his shoulder was reduced with the traction-countertraction technique described earlier. Postreduction radiographs revealed satisfactory alignment of the right glenohumeral joint and that the greater tuberosity was reduced to within a centimeter of its normal position. No additional fractures were identified.

After the reduction, a head CT scan was done; it revealed a small intracerebral hemorrhage. The patient was admitted overnight and discharged the following day with a sling and swathe and instructions to follow up with orthopedics.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Z. MacVane, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA, Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:423-426.

2. Goldstein JR, Eilbert WP. Locked anterior-inferior shoulder subluxation presenting as luxatio erecta. J Emerg Med 2004;27:245-248.

3. Yamamoto T, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M, et al. Luxatio erecta: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop 2003;32:601-603.

4. Sonanis SV, Das S, Deshmukh N, et al. A true traumatic inferior dislocation of shoulder. Injury 2002;33:842-844.

5. Yanturali S, Aksay E, Holliman CJ, et al. Luxatio erecta: clinical presentation and management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:85-89.

6. Krug DK, Vinson EN, Helms CA. MRI findings associated with luxatio erecta humeri. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:27-33.

7. Plaga BR, Looby P, Feldhaus SJ, et al. Axillary artery injury secondary to inferior shoulder dislocation. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:599-601.

8. Sewecke JJ, Varitimidis SE. Bilateral luxatio erecta: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 2006;35:578-580.

A 38-YEAR-OLD MAN was brought into our emergency department (ED) after driving his motorcycle at high speed into a tree. The patient, who hadn’t been wearing a helmet, was thrown 30 feet. When EMS arrived, the patient was unresponsive, with his right arm in the air. En route, the patient regained consciousness; he appeared intoxicated and became combative.

The patient was evaluated in the ED and his vital signs were normal. His right arm was abducted and over his head (FIGURE 1). He reported significant pain with palpation and attempts at range of motion. We were unable to place the patient’s arm at his side. Other than some minor abrasions, the patient appeared to have no other injuries.

FIGURE 1Right upper extremity on presentation

Routine laboratory tests showed an alcohol level of 0.175 g/dL and urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and tetrahydrocannabinol. A focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam was negative. We ordered a right shoulder x-ray and a chest x-ray.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Inferior dislocation of the shoulder

The right shoulder x-ray (FIGURE 2) revealed luxatio erecta—an inferior dislocation of the shoulder. The humeral head was displaced inferiorly with respect to the glenoid fossa and there was an associated greater tuberosity fracture. The chest x-ray demonstrated mild pulmonary contusions.

FIGURE 2

Right shoulder radiograph reveals luxatio erecta with greater tuberosity fracture

An uncommon dislocation

Inferior shoulder dislocation or luxatio erecta is the least common type of glenohumeral dislocation, comprising only about 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 The 2 other types of shoulder dislocations—anterior and posterior—account for 95% to 97% and 2% to 4% of dislocations, respectively.2

Injury occurs in one of 2 ways, either by a direct or indirect mechanism. A direct dislocation occurs when there is axial loading on an arm that is fully abducted at the shoulder.3 The indirect mechanism, which is more common, is caused by a hyperabduction stress that directs the humeral neck superiorly against the acromion process, forcing the humeral head out of the glenoid fossa inferiorly.2 The indirect mechanism usually occurs when a patient falls and reacts by grasping an object above his or her head, resulting in hyperabduction.

Sometimes, there is no trauma. True inferior dislocations have also been reported in patients with stroke, septic arthritis, and other neuromuscular diseases.4

The presentation is distinctive

Patients with this type of dislocation present with their arm elevated, elbow flexed, and hand behind their head. Due to mechanical entrapment of the humeral head, patients can’t move their arm. The abducted position of the arm may hinder further assessment with computed tomography (CT) for life-threatening injuries, as was the case with our patient.

While an immobile, abducted arm is virtually pathognomonic, radiographs are useful for confirming the diagnosis and assessing for associated fractures. It is essential to obtain anteroposterior, axillary, and Y views.5 Radiographs typically show the shaft of the humerus directed superiorly and parallel to the scapular spine, with the humeral head below the coracoid process or glenoid fossa.3,5

Rotator cuff tears are a common complication

There are a number of complications associated with luxatio erecta. Eighty percent of patients with this injury have either an associated rotator cuff tear or a fracture of the greater tuberosity (which we’ll get to in a bit).3 Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown rotator cuff injuries to involve the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and, less frequently, the subscapularis tendon.6 It’s believed that rotator cuff tears may be even more prevalent than reported in the literature since they are often underrecognized at the time of presentation with the dislocation.6

Other complications. Sixty percent of patients report some degree of neurologic dysfunction after the dislocation.5 The most common nerve affected is the axillary, followed by the radial, ulnar, and median nerves.3 These injuries are more likely to occur with associated fractures of the greater tuberosity or axillary artery injuries.7 Symptoms generally resolve after reduction, although there have been cases that have taken up to 6 weeks to resolve.8

Vascular compromise, most commonly occurring as a result of axillary artery injury, has been reported in 3.3% of cases.5 This injury is most common in elderly patients, with 75% of cases occurring in patients older than 60 years.7 It’s been hypothesized that this is due to the loss of arterial elasticity as an individual ages. The most common presenting signs and symptoms include absent radial and/or brachial pulses, severe pain, axillary swelling, axillary masses due to hematoma formation, and neurologic deficits.7 Complications are minimal if diagnosed and treated early.

The most expeditious way to diagnose this complication is to obtain a Doppler ultrasound of the injured extremity. If surgery is indicated, saphenous vein graft has been reported as a successful treatment.3