User login

Nasal obstruction

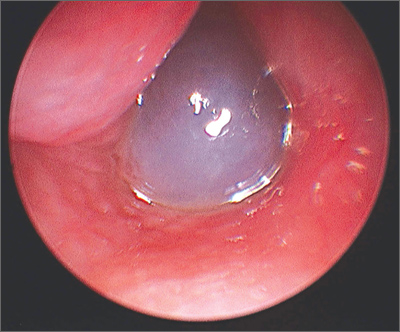

The FP diagnosed a nasal polyp, secondary to allergic rhinitis, in this patient. Nasal polyps are benign lesions arising from the mucosa of the nasal passages, including the paranasal sinuses. They are most commonly semitransparent.

Nasal polyps are associated with the following conditions:

- nonallergic and allergic rhinitis and rhinosinusitis

- asthma

- cystic fibrosis

- aspirin intolerance

- alcohol intolerance.

Medical treatment consists of intranasal corticosteroids. An initial short course (2-4 weeks) of oral steroids may be considered in severe cases. Steroid treatment reduces polyp size, but is not likely to eliminate them. Oral doxycycline 100 mg daily for 20 days was shown to decrease polyp size, providing benefit for 12 weeks in one randomized controlled trial. Topical nasal decongestants may provide some symptom relief, but will not reduce polyp size. Montelukast reduces symptoms when used as an adjunct to oral and inhaled steroid therapy in patients with bilateral nasal polyposis. Surgical excision is often required to relieve symptoms.

The FP prescribed nasal fluticasone daily and the patient had some relief, but his obstructive symptoms persisted. After 2 months of persistent symptoms, the patient was referred to an otolaryngologist to discuss the benefits and risks of polypectomy.

Photo courtesy of William Clark, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Nasal polyps. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:193-196.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed a nasal polyp, secondary to allergic rhinitis, in this patient. Nasal polyps are benign lesions arising from the mucosa of the nasal passages, including the paranasal sinuses. They are most commonly semitransparent.

Nasal polyps are associated with the following conditions:

- nonallergic and allergic rhinitis and rhinosinusitis

- asthma

- cystic fibrosis

- aspirin intolerance

- alcohol intolerance.

Medical treatment consists of intranasal corticosteroids. An initial short course (2-4 weeks) of oral steroids may be considered in severe cases. Steroid treatment reduces polyp size, but is not likely to eliminate them. Oral doxycycline 100 mg daily for 20 days was shown to decrease polyp size, providing benefit for 12 weeks in one randomized controlled trial. Topical nasal decongestants may provide some symptom relief, but will not reduce polyp size. Montelukast reduces symptoms when used as an adjunct to oral and inhaled steroid therapy in patients with bilateral nasal polyposis. Surgical excision is often required to relieve symptoms.

The FP prescribed nasal fluticasone daily and the patient had some relief, but his obstructive symptoms persisted. After 2 months of persistent symptoms, the patient was referred to an otolaryngologist to discuss the benefits and risks of polypectomy.

Photo courtesy of William Clark, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Nasal polyps. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:193-196.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed a nasal polyp, secondary to allergic rhinitis, in this patient. Nasal polyps are benign lesions arising from the mucosa of the nasal passages, including the paranasal sinuses. They are most commonly semitransparent.

Nasal polyps are associated with the following conditions:

- nonallergic and allergic rhinitis and rhinosinusitis

- asthma

- cystic fibrosis

- aspirin intolerance

- alcohol intolerance.

Medical treatment consists of intranasal corticosteroids. An initial short course (2-4 weeks) of oral steroids may be considered in severe cases. Steroid treatment reduces polyp size, but is not likely to eliminate them. Oral doxycycline 100 mg daily for 20 days was shown to decrease polyp size, providing benefit for 12 weeks in one randomized controlled trial. Topical nasal decongestants may provide some symptom relief, but will not reduce polyp size. Montelukast reduces symptoms when used as an adjunct to oral and inhaled steroid therapy in patients with bilateral nasal polyposis. Surgical excision is often required to relieve symptoms.

The FP prescribed nasal fluticasone daily and the patient had some relief, but his obstructive symptoms persisted. After 2 months of persistent symptoms, the patient was referred to an otolaryngologist to discuss the benefits and risks of polypectomy.

Photo courtesy of William Clark, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Nasal polyps. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:193-196.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Fleshy growths on ear

The FP explained to the patient’s mother that the boy had preauricular tags. These occur in approximately 1 out of 10,000 to 12,500 births, without predilection for gender or race. Ear malformations may occur in isolation, or as part of a constellation of abnormalities--often involving the renal system. Children with preauricular tags have a 5-fold increased risk of hearing impairment. Several chromosomal abnormalities (eg, Goldenhar syndrome) include preauricular tags as one of the phenotypic expressions.

Preauricular tags arise from remnants of supernumerary branchial hillocks. Early stage embryology involves the formation of several slit-like structures on the side of the head, the branchial clefts. The 3 hillocks between the first 4 clefts eventually form the structure of the outer ear. Preauricular tags are generally minor malformations arising from remnants of the hillocks. Preauricular tags can be left alone or surgically excised for cosmetic reasons.

In this case, the child had normal hearing and hadn’t had any urinary tract infections. The FP explained that the changing size of the tags was not worrisome and that they could be removed for cosmetic purposes, but her son would have to undergo general anesthesia for the surgery. The mother agreed with the FP that the benefits of the surgery did not outweigh the risks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis and preauricular tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:189-192.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained to the patient’s mother that the boy had preauricular tags. These occur in approximately 1 out of 10,000 to 12,500 births, without predilection for gender or race. Ear malformations may occur in isolation, or as part of a constellation of abnormalities--often involving the renal system. Children with preauricular tags have a 5-fold increased risk of hearing impairment. Several chromosomal abnormalities (eg, Goldenhar syndrome) include preauricular tags as one of the phenotypic expressions.

Preauricular tags arise from remnants of supernumerary branchial hillocks. Early stage embryology involves the formation of several slit-like structures on the side of the head, the branchial clefts. The 3 hillocks between the first 4 clefts eventually form the structure of the outer ear. Preauricular tags are generally minor malformations arising from remnants of the hillocks. Preauricular tags can be left alone or surgically excised for cosmetic reasons.

In this case, the child had normal hearing and hadn’t had any urinary tract infections. The FP explained that the changing size of the tags was not worrisome and that they could be removed for cosmetic purposes, but her son would have to undergo general anesthesia for the surgery. The mother agreed with the FP that the benefits of the surgery did not outweigh the risks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis and preauricular tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:189-192.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained to the patient’s mother that the boy had preauricular tags. These occur in approximately 1 out of 10,000 to 12,500 births, without predilection for gender or race. Ear malformations may occur in isolation, or as part of a constellation of abnormalities--often involving the renal system. Children with preauricular tags have a 5-fold increased risk of hearing impairment. Several chromosomal abnormalities (eg, Goldenhar syndrome) include preauricular tags as one of the phenotypic expressions.

Preauricular tags arise from remnants of supernumerary branchial hillocks. Early stage embryology involves the formation of several slit-like structures on the side of the head, the branchial clefts. The 3 hillocks between the first 4 clefts eventually form the structure of the outer ear. Preauricular tags are generally minor malformations arising from remnants of the hillocks. Preauricular tags can be left alone or surgically excised for cosmetic reasons.

In this case, the child had normal hearing and hadn’t had any urinary tract infections. The FP explained that the changing size of the tags was not worrisome and that they could be removed for cosmetic purposes, but her son would have to undergo general anesthesia for the surgery. The mother agreed with the FP that the benefits of the surgery did not outweigh the risks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis and preauricular tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:189-192.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Nodule on ear

The FP told the patient that this was likely a benign condition called chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. A shave biopsy/removal was performed to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out skin cancer. The biopsy confirmed the FP’s suspicions.

Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis is a benign neoplasm of the ear cartilage that is believed to be related to excessive pressure during sleep. The result is a localized overgrowth of cartilage and subsequent skin changes. It is more commonly seen in men. The helix is most often affected in men and the antihelix in women.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, intralesional steroid injection, electrodesiccation, and curettage and elliptical excision. Less aggressive treatment options (cryosurgery and intralesional steroids) tend to be less successful.

If a patient does not want surgery, a pressure-relieving prosthesis or donut-shaped pillow can be used. Patients can create such a prosthesis by cutting a hole from the center of a bath sponge. The sponge can then be held in place with a headband, if needed.

In this case, elliptical excision including curettage of the involved cartilage was used to treat the patient, with excellent results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis and preauricular tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:189-192.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP told the patient that this was likely a benign condition called chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. A shave biopsy/removal was performed to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out skin cancer. The biopsy confirmed the FP’s suspicions.

Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis is a benign neoplasm of the ear cartilage that is believed to be related to excessive pressure during sleep. The result is a localized overgrowth of cartilage and subsequent skin changes. It is more commonly seen in men. The helix is most often affected in men and the antihelix in women.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, intralesional steroid injection, electrodesiccation, and curettage and elliptical excision. Less aggressive treatment options (cryosurgery and intralesional steroids) tend to be less successful.

If a patient does not want surgery, a pressure-relieving prosthesis or donut-shaped pillow can be used. Patients can create such a prosthesis by cutting a hole from the center of a bath sponge. The sponge can then be held in place with a headband, if needed.

In this case, elliptical excision including curettage of the involved cartilage was used to treat the patient, with excellent results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis and preauricular tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:189-192.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP told the patient that this was likely a benign condition called chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. A shave biopsy/removal was performed to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out skin cancer. The biopsy confirmed the FP’s suspicions.

Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis is a benign neoplasm of the ear cartilage that is believed to be related to excessive pressure during sleep. The result is a localized overgrowth of cartilage and subsequent skin changes. It is more commonly seen in men. The helix is most often affected in men and the antihelix in women.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, intralesional steroid injection, electrodesiccation, and curettage and elliptical excision. Less aggressive treatment options (cryosurgery and intralesional steroids) tend to be less successful.

If a patient does not want surgery, a pressure-relieving prosthesis or donut-shaped pillow can be used. Patients can create such a prosthesis by cutting a hole from the center of a bath sponge. The sponge can then be held in place with a headband, if needed.

In this case, elliptical excision including curettage of the involved cartilage was used to treat the patient, with excellent results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis and preauricular tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:189-192.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

An incidental finding

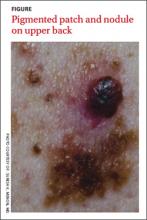

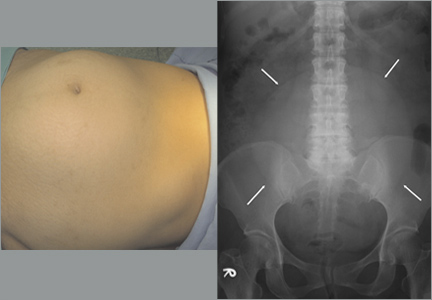

A 37-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for the pruritic patches on his trunk and extremities that had developed 3 days earlier. The patient said that the lesions started on his right arm but had spread to his left arm, posterior legs, and trunk. He reported that the trunk lesions had resolved, but the extremity lesions persisted. He’d had no specific contact exposures.

Upon further questioning, the patient indicated that he had noted the pigmented patch for at least 4 years, but was not sure how long the nodular area had been there. He thought it was a birthmark. He grew up spending a lot of time at the beach in the sun and recalled at least one blistering sunburn on his back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Melanoma

The patient underwent elliptical excisional biopsy of the primary lesion after no palpable lymphadenopathy was noted. The lateral and deep margins were negative for melanoma; the mitotic rate was <1/mm2. Aggregates of lymphocytes were associated with the lesion, but did not infiltrate it. There was no tumor regression or ulceration of the lesion. The Breslow depth was 1.25 mm.

A histopathologic evaluation revealed a superficial spreading melanoma (inferior lesion in the FIGURE) and a nodular lesion (the superior reddish-black lesion in the FIGURE). (For more on these and other forms of melanoma, see “The 4 main types of melanoma”1-4 see below.) It was unclear from the patient’s history whether this represented 2 types of melanoma (superficial spreading and nodular) in the same field of skin or the development of a nodular component in a superficial spreading lesion. Important clinical information was also missing, including the evolution of the lesions and how quickly the nodule had grown.

Who’s affected most? More than 45,000 cases of melanoma occurred in 45 states and the District of Columbia annually between 2004 and 2006, according to a 2011 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.5 White, non-Hispanics have a far higher incidence of melanoma than any other race or ethnicity.6 Women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with melanoma early in life, while men are twice as likely as women to be diagnosed after age 60.6 The etiology for the malignant transformation of melanocytes has not been fully clarified, but it is likely multifactorial, including genetic susceptibility and ultraviolet (UV) radiation damage.4

The ABCDE mnemonic is widely taught to aid in the detection of melanomas: A = asymmetry of the lesion; B = border irregularities; C = color variegation; D = diameter >6 mm; and E = evolution. The evolution of the lesion has been shown in some studies to be the most specific finding for detecting melanomas.4

Regional lymph nodes should also be carefully examined for evidence of clinical spread prior to biopsy of a suspicious lesion. This is important because biopsy may cause regional lymphadenopathy, which could confound later examinations and staging of the disease.1

The differential: Is it a worrisome lesion—or not?

The differential diagnosis of melanoma includes both benign and malignant lesions. Malignant and potentially malignant diagnoses to consider include pigmented basal cell carcinoma, pigmented squamous cell carcinoma, carcinoma metastatic to the skin, and dysplastic nevi.2,3

Benign diagnoses to consider include pigmented seborrheic keratoses, lentigo, pyogenic granuloma, Kaposi sarcoma, cherry angioma, subungual traumatic hematoma, dermatofibroma, and nevi (including blue nevi).2,3

The biopsy is paramount

A diagnosis is established based on the microscopic evaluation of suspicious lesions. Studies suggest that one-third to one-half of melanomas arise from existing nevi, with the remainder developing from previously normal-appearing skin.1,2 Patients with increased numbers of either common or dysplastic nevi are at increased risk of melanoma compared with the general population.4 Historical clues include changes in a lesion’s size, color, or symmetry; new growths; personal or family history of melanoma; and bleeding.

A biopsy for histopathologic evaluation is mandatory when a lesion is suspicious for melanoma. Dermoscopy, which involves a device that magnifies skin lesions, may reveal highly specific dermoscopic features for melanoma that can help in determining the need for biopsy.4

The preferred method for biopsy is complete elliptical excision with 2- to 3-mm margins of normal skin.2,3 However, a deep shave biopsy may also be appropriate, depending upon the clinical situation and physician experience with the technique.4

A deep shave biopsy is less time consuming than elliptical excision, making it easier to perform at the time the lesion is first evaluated. Deep shave biopsy may provide several benefits, including reducing the amount of normal tissue that is removed (especially if pathology is benign) as well as, the cost, scarring, and likelihood of wound infections. Deep shave biopsy also can avoid the need for a second elliptical excision.7,8

Determine margins, proceed with surgical excision

Early surgical excision is the primary treatment for malignant melanoma. After the diagnosis is confirmed by initial biopsy, the depth of the lesion dictates the surgical recommendations. Recommended surgical margins based on depth are: 5 mm with a layer of subcutaneous fat for melanoma in situ, 1 cm down to the fascia for lesions with a Breslow depth ≤2 mm, and 2 cm down to the fascia for lesions with a depth >2 mm.1,4

The surgical treatment of lentigo maligna melanoma can be challenging due to indistinct borders and large size. Mohs micrographic surgery can be helpful to fully remove the lesion with sparing of healthy surrounding tissue.4 When surgical excision of large lentigo maligna is technically difficult, radiation therapy is another option.3

Subungual melanoma may necessitate amputation or grafting of the digit. Mohs micrographic surgery can be useful in these situations for tissue sparing.2 (To learn more, see “When to consider Mohs surgery,” J Fam Pract. 2013;558-564.)

Is a sentinel lymph node biopsy needed?

Sentinel lymph node biopsy is often recommended for melanomas >1 mm in depth.2-4 It provides guidance on who may benefit from regional lymphadenectomy and adjuvant immunotherapy.1,3

Adjuvant therapy for patients without evidence of distant metastases can be considered in patients with positive nodes or node-negative melanoma that is 4 mm thick or Clark Level IV or V. Adjuvant high-dose interferon alpha-2b is the most commonly used agent in these situations.2 Some studies suggest an increase in median overall survival of up to 11 months with high-dose interferon as compared to no treatment.3 Limitations include toxicity from these high-dose regimens.3 Treatment with interferon does not represent a cure; rather, it should be considered a palliative intervention with marginal benefit.1

When there are distant metastases…

Once distant metastases are identified, the goal of therapy should be palliative care as this condition is generally incurable. Chemotherapy, radiation, and excision of solitary metastases are all interventions that have traditionally been employed.1 The primary site for metastasis is the skin, but all organs are potential sites of spread. Central nervous system metastasis is the most common cause of the death.2

Novel therapies include inhibition of BRAF, an enzyme of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (MAPK), and blocking of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4).

BRAF-enzyme inhibitor. Mutated BRAF contributes to uncontrolled cell growth and resistance to programmed cell death (apoptosis).9,10 In August 2011, vemurafenib (Zelboraf ), a BRAF-enzyme inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of late-stage melanoma. It works only in patients with the BRAFV600E mutation, which is found in approximately 60% of melanomas.11,12 One phase 1 study showed partial to complete regression in 80% of patients treated, but this regression lasted only 2 to 18 months.13

Anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes can recognize and potentially destroy cancer cells.14 However, CTLA-4, which is expressed on the surface of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, has a suppressive effect on the T-lymphocyte response after interaction with the antigen-presenting cell. Researchers deduced that blocking CTLA-4 would allow the immune system to remain responsive to abnormal antigens, including those from melanoma.9

Ipilimumab (Yervoy), an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, was approved by the FDA in March 2011 for the treatment of late-stage melanoma.11 Partial and complete responses have been shown in trials of ipilimumab as monotherapy and in combination with vaccines, chemotherapy, and interleukin-2, but these responses have not been sustained.9

Although these novel therapies represent significant advancements in the understanding of the pathogenesis of melanoma, the short duration of efficacy highlights the cancer’s ability to develop resistance to these treatments. This ability to adapt suggests that melanoma harbors multiple oncogenes and several pathways for carcinogenesis. Combination targeted therapies may be required to improve clinical results; research is ongoing.9 Toxicities associated with these medications are also a limiting factor.

What about vaccines? Vaccine studies are also ongoing. Although some have shown promising results, no clearly effective therapy has been produced to date.2

Factors that affect prognosis

The prognosis for melanoma is related to tumor thickness, presence or absence of melanoma in regional lymph nodes, and extent of metastases.1-4 The TNM classification system takes these factors into account in staging melanoma.4 Based on this staging, a 5- and 10-year survival estimate can be discussed with the patient.

Survival estimates based on depth of invasion alone are also used. As an example, one study cited a 5-year survival rate of 95% for a tumor thickness <.75 mm; 85% (.75-1.4 mm); 66% (1.5-3.9 mm); and 46% (≥4 mm).1

Other variables that affect prognosis include lymphocytic infiltrate (more brisk and tumor infiltrating is better prognostically), mitotic rate (less is better; >6/mm2 is worse), ulceration (worse prognostically), and regression of the tumor.2 Regression will appear as areas of depigmentation in a previously completely pigmented lesion; it is associated with a poorer prognosis.1

Follow-up with patients is key

Regular skin, lymph node, and general follow-up exams are recommended to detect metastatic disease or new primary lesions. It has been estimated that approximately 5% of patients with a history of melanoma will develop a new primary lesion.3 Lab and imaging studies should be used when prompted by clinical findings.2

Some protocols recommend routine use of labs, including lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood count, and chemistries, as well as imaging such as chest x-ray, positron emission tomography (PET), or computed tomography (CT) based on the stage of the disease.4 No evidence has shown that routine laboratory or imaging studies affect prognosis.2

Close surveillance for my patient

My patient underwent re-excision of the tumor site with wide margins. Sentinel lymph nodes excised from the bilateral axilla were negative for melanoma. He was seen by colleagues in the oncology department, and his lab work and chest x-ray were normal. PET/CT revealed no evidence of fluorodeoxyglucose avid metastatic disease.

Based on staging, my patient’s 5-year survival was estimated at 81% and his 10-year survival at 67%. No further oncology follow-up was planned and the patient was instructed to be seen by a dermatologist for close clinical surveillance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Suresh K. Menon, MD, Hahn Medical Practices, 5078 Williamsport Pike, Martinsburg, WV 25404; [email protected]

1. Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, Clayton E, et al. Melanoma. In: Hefta J, Noujaim SR, Edmonson KG, eds. 20 Common Problems in Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000:201-217.

2. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Melanoma (malignant melanoma). In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:694-699.

3. Marks JG, Miller JJ. Malignant melanoma. In: Marks JG, Miller JJ, Lookingbill DP, eds. Principles of Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:78-81.

4. Shenenberger DW. Cutaneous malignant melanoma: a primary care perspective. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:161-168.

5. Melanoma surveillance in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/what_cdc_is_doing/melanoma_supplement.htm. Accessed October 11, 2013.

6. Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, et al, eds. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH Pub. No. 06-5767; 2006.

7. Usatine RP, Pfenninger JL, Stulberg DL, et al. Choosing the biopsy type. In: Usatine RP, Pfenninger, JL, Stulberg DL, et al, eds. Dermatologic and Cosmetic Procedures in Office Practice. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011: 75.

8. Usatine RP, Pfenninger JL, Stulberg DL, et al. The shave biopsy. In: Usatine RP, Pfenninger, JL, Stulberg DL, et al, eds. Dermatologic and Cosmetic Procedures in Office Practice. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011: 88.

9. Weber, JS. A New Era Approaches: Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Malignant Melanoma. Medscape Education Web site. Available at: http://www.medscape.org/viewprogram/17800. Accessed July 7, 2012.

10. Shao Y, Aplin AE. Akt3-mediated resistance to apoptosis in B-RAF-targeted melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6670-6681.

11. Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435.

12. Halaban R, Zhang W, Bacchiocchi A, et al. PLX4032, a selective BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor, activates the ERK pathway and enhances cell migration and proliferation of BRAF melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:190-200.

13. Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809-819.

14. Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2517-2519.

A 37-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for the pruritic patches on his trunk and extremities that had developed 3 days earlier. The patient said that the lesions started on his right arm but had spread to his left arm, posterior legs, and trunk. He reported that the trunk lesions had resolved, but the extremity lesions persisted. He’d had no specific contact exposures.

Upon further questioning, the patient indicated that he had noted the pigmented patch for at least 4 years, but was not sure how long the nodular area had been there. He thought it was a birthmark. He grew up spending a lot of time at the beach in the sun and recalled at least one blistering sunburn on his back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Melanoma

The patient underwent elliptical excisional biopsy of the primary lesion after no palpable lymphadenopathy was noted. The lateral and deep margins were negative for melanoma; the mitotic rate was <1/mm2. Aggregates of lymphocytes were associated with the lesion, but did not infiltrate it. There was no tumor regression or ulceration of the lesion. The Breslow depth was 1.25 mm.

A histopathologic evaluation revealed a superficial spreading melanoma (inferior lesion in the FIGURE) and a nodular lesion (the superior reddish-black lesion in the FIGURE). (For more on these and other forms of melanoma, see “The 4 main types of melanoma”1-4 see below.) It was unclear from the patient’s history whether this represented 2 types of melanoma (superficial spreading and nodular) in the same field of skin or the development of a nodular component in a superficial spreading lesion. Important clinical information was also missing, including the evolution of the lesions and how quickly the nodule had grown.

Who’s affected most? More than 45,000 cases of melanoma occurred in 45 states and the District of Columbia annually between 2004 and 2006, according to a 2011 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.5 White, non-Hispanics have a far higher incidence of melanoma than any other race or ethnicity.6 Women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with melanoma early in life, while men are twice as likely as women to be diagnosed after age 60.6 The etiology for the malignant transformation of melanocytes has not been fully clarified, but it is likely multifactorial, including genetic susceptibility and ultraviolet (UV) radiation damage.4

The ABCDE mnemonic is widely taught to aid in the detection of melanomas: A = asymmetry of the lesion; B = border irregularities; C = color variegation; D = diameter >6 mm; and E = evolution. The evolution of the lesion has been shown in some studies to be the most specific finding for detecting melanomas.4

Regional lymph nodes should also be carefully examined for evidence of clinical spread prior to biopsy of a suspicious lesion. This is important because biopsy may cause regional lymphadenopathy, which could confound later examinations and staging of the disease.1

The differential: Is it a worrisome lesion—or not?

The differential diagnosis of melanoma includes both benign and malignant lesions. Malignant and potentially malignant diagnoses to consider include pigmented basal cell carcinoma, pigmented squamous cell carcinoma, carcinoma metastatic to the skin, and dysplastic nevi.2,3

Benign diagnoses to consider include pigmented seborrheic keratoses, lentigo, pyogenic granuloma, Kaposi sarcoma, cherry angioma, subungual traumatic hematoma, dermatofibroma, and nevi (including blue nevi).2,3

The biopsy is paramount

A diagnosis is established based on the microscopic evaluation of suspicious lesions. Studies suggest that one-third to one-half of melanomas arise from existing nevi, with the remainder developing from previously normal-appearing skin.1,2 Patients with increased numbers of either common or dysplastic nevi are at increased risk of melanoma compared with the general population.4 Historical clues include changes in a lesion’s size, color, or symmetry; new growths; personal or family history of melanoma; and bleeding.

A biopsy for histopathologic evaluation is mandatory when a lesion is suspicious for melanoma. Dermoscopy, which involves a device that magnifies skin lesions, may reveal highly specific dermoscopic features for melanoma that can help in determining the need for biopsy.4

The preferred method for biopsy is complete elliptical excision with 2- to 3-mm margins of normal skin.2,3 However, a deep shave biopsy may also be appropriate, depending upon the clinical situation and physician experience with the technique.4

A deep shave biopsy is less time consuming than elliptical excision, making it easier to perform at the time the lesion is first evaluated. Deep shave biopsy may provide several benefits, including reducing the amount of normal tissue that is removed (especially if pathology is benign) as well as, the cost, scarring, and likelihood of wound infections. Deep shave biopsy also can avoid the need for a second elliptical excision.7,8

Determine margins, proceed with surgical excision

Early surgical excision is the primary treatment for malignant melanoma. After the diagnosis is confirmed by initial biopsy, the depth of the lesion dictates the surgical recommendations. Recommended surgical margins based on depth are: 5 mm with a layer of subcutaneous fat for melanoma in situ, 1 cm down to the fascia for lesions with a Breslow depth ≤2 mm, and 2 cm down to the fascia for lesions with a depth >2 mm.1,4

The surgical treatment of lentigo maligna melanoma can be challenging due to indistinct borders and large size. Mohs micrographic surgery can be helpful to fully remove the lesion with sparing of healthy surrounding tissue.4 When surgical excision of large lentigo maligna is technically difficult, radiation therapy is another option.3

Subungual melanoma may necessitate amputation or grafting of the digit. Mohs micrographic surgery can be useful in these situations for tissue sparing.2 (To learn more, see “When to consider Mohs surgery,” J Fam Pract. 2013;558-564.)

Is a sentinel lymph node biopsy needed?

Sentinel lymph node biopsy is often recommended for melanomas >1 mm in depth.2-4 It provides guidance on who may benefit from regional lymphadenectomy and adjuvant immunotherapy.1,3

Adjuvant therapy for patients without evidence of distant metastases can be considered in patients with positive nodes or node-negative melanoma that is 4 mm thick or Clark Level IV or V. Adjuvant high-dose interferon alpha-2b is the most commonly used agent in these situations.2 Some studies suggest an increase in median overall survival of up to 11 months with high-dose interferon as compared to no treatment.3 Limitations include toxicity from these high-dose regimens.3 Treatment with interferon does not represent a cure; rather, it should be considered a palliative intervention with marginal benefit.1

When there are distant metastases…

Once distant metastases are identified, the goal of therapy should be palliative care as this condition is generally incurable. Chemotherapy, radiation, and excision of solitary metastases are all interventions that have traditionally been employed.1 The primary site for metastasis is the skin, but all organs are potential sites of spread. Central nervous system metastasis is the most common cause of the death.2

Novel therapies include inhibition of BRAF, an enzyme of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (MAPK), and blocking of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4).

BRAF-enzyme inhibitor. Mutated BRAF contributes to uncontrolled cell growth and resistance to programmed cell death (apoptosis).9,10 In August 2011, vemurafenib (Zelboraf ), a BRAF-enzyme inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of late-stage melanoma. It works only in patients with the BRAFV600E mutation, which is found in approximately 60% of melanomas.11,12 One phase 1 study showed partial to complete regression in 80% of patients treated, but this regression lasted only 2 to 18 months.13

Anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes can recognize and potentially destroy cancer cells.14 However, CTLA-4, which is expressed on the surface of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, has a suppressive effect on the T-lymphocyte response after interaction with the antigen-presenting cell. Researchers deduced that blocking CTLA-4 would allow the immune system to remain responsive to abnormal antigens, including those from melanoma.9

Ipilimumab (Yervoy), an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, was approved by the FDA in March 2011 for the treatment of late-stage melanoma.11 Partial and complete responses have been shown in trials of ipilimumab as monotherapy and in combination with vaccines, chemotherapy, and interleukin-2, but these responses have not been sustained.9

Although these novel therapies represent significant advancements in the understanding of the pathogenesis of melanoma, the short duration of efficacy highlights the cancer’s ability to develop resistance to these treatments. This ability to adapt suggests that melanoma harbors multiple oncogenes and several pathways for carcinogenesis. Combination targeted therapies may be required to improve clinical results; research is ongoing.9 Toxicities associated with these medications are also a limiting factor.

What about vaccines? Vaccine studies are also ongoing. Although some have shown promising results, no clearly effective therapy has been produced to date.2

Factors that affect prognosis

The prognosis for melanoma is related to tumor thickness, presence or absence of melanoma in regional lymph nodes, and extent of metastases.1-4 The TNM classification system takes these factors into account in staging melanoma.4 Based on this staging, a 5- and 10-year survival estimate can be discussed with the patient.

Survival estimates based on depth of invasion alone are also used. As an example, one study cited a 5-year survival rate of 95% for a tumor thickness <.75 mm; 85% (.75-1.4 mm); 66% (1.5-3.9 mm); and 46% (≥4 mm).1

Other variables that affect prognosis include lymphocytic infiltrate (more brisk and tumor infiltrating is better prognostically), mitotic rate (less is better; >6/mm2 is worse), ulceration (worse prognostically), and regression of the tumor.2 Regression will appear as areas of depigmentation in a previously completely pigmented lesion; it is associated with a poorer prognosis.1

Follow-up with patients is key

Regular skin, lymph node, and general follow-up exams are recommended to detect metastatic disease or new primary lesions. It has been estimated that approximately 5% of patients with a history of melanoma will develop a new primary lesion.3 Lab and imaging studies should be used when prompted by clinical findings.2

Some protocols recommend routine use of labs, including lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood count, and chemistries, as well as imaging such as chest x-ray, positron emission tomography (PET), or computed tomography (CT) based on the stage of the disease.4 No evidence has shown that routine laboratory or imaging studies affect prognosis.2

Close surveillance for my patient

My patient underwent re-excision of the tumor site with wide margins. Sentinel lymph nodes excised from the bilateral axilla were negative for melanoma. He was seen by colleagues in the oncology department, and his lab work and chest x-ray were normal. PET/CT revealed no evidence of fluorodeoxyglucose avid metastatic disease.

Based on staging, my patient’s 5-year survival was estimated at 81% and his 10-year survival at 67%. No further oncology follow-up was planned and the patient was instructed to be seen by a dermatologist for close clinical surveillance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Suresh K. Menon, MD, Hahn Medical Practices, 5078 Williamsport Pike, Martinsburg, WV 25404; [email protected]

A 37-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for the pruritic patches on his trunk and extremities that had developed 3 days earlier. The patient said that the lesions started on his right arm but had spread to his left arm, posterior legs, and trunk. He reported that the trunk lesions had resolved, but the extremity lesions persisted. He’d had no specific contact exposures.

Upon further questioning, the patient indicated that he had noted the pigmented patch for at least 4 years, but was not sure how long the nodular area had been there. He thought it was a birthmark. He grew up spending a lot of time at the beach in the sun and recalled at least one blistering sunburn on his back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Melanoma

The patient underwent elliptical excisional biopsy of the primary lesion after no palpable lymphadenopathy was noted. The lateral and deep margins were negative for melanoma; the mitotic rate was <1/mm2. Aggregates of lymphocytes were associated with the lesion, but did not infiltrate it. There was no tumor regression or ulceration of the lesion. The Breslow depth was 1.25 mm.

A histopathologic evaluation revealed a superficial spreading melanoma (inferior lesion in the FIGURE) and a nodular lesion (the superior reddish-black lesion in the FIGURE). (For more on these and other forms of melanoma, see “The 4 main types of melanoma”1-4 see below.) It was unclear from the patient’s history whether this represented 2 types of melanoma (superficial spreading and nodular) in the same field of skin or the development of a nodular component in a superficial spreading lesion. Important clinical information was also missing, including the evolution of the lesions and how quickly the nodule had grown.

Who’s affected most? More than 45,000 cases of melanoma occurred in 45 states and the District of Columbia annually between 2004 and 2006, according to a 2011 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.5 White, non-Hispanics have a far higher incidence of melanoma than any other race or ethnicity.6 Women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with melanoma early in life, while men are twice as likely as women to be diagnosed after age 60.6 The etiology for the malignant transformation of melanocytes has not been fully clarified, but it is likely multifactorial, including genetic susceptibility and ultraviolet (UV) radiation damage.4

The ABCDE mnemonic is widely taught to aid in the detection of melanomas: A = asymmetry of the lesion; B = border irregularities; C = color variegation; D = diameter >6 mm; and E = evolution. The evolution of the lesion has been shown in some studies to be the most specific finding for detecting melanomas.4

Regional lymph nodes should also be carefully examined for evidence of clinical spread prior to biopsy of a suspicious lesion. This is important because biopsy may cause regional lymphadenopathy, which could confound later examinations and staging of the disease.1

The differential: Is it a worrisome lesion—or not?

The differential diagnosis of melanoma includes both benign and malignant lesions. Malignant and potentially malignant diagnoses to consider include pigmented basal cell carcinoma, pigmented squamous cell carcinoma, carcinoma metastatic to the skin, and dysplastic nevi.2,3

Benign diagnoses to consider include pigmented seborrheic keratoses, lentigo, pyogenic granuloma, Kaposi sarcoma, cherry angioma, subungual traumatic hematoma, dermatofibroma, and nevi (including blue nevi).2,3

The biopsy is paramount

A diagnosis is established based on the microscopic evaluation of suspicious lesions. Studies suggest that one-third to one-half of melanomas arise from existing nevi, with the remainder developing from previously normal-appearing skin.1,2 Patients with increased numbers of either common or dysplastic nevi are at increased risk of melanoma compared with the general population.4 Historical clues include changes in a lesion’s size, color, or symmetry; new growths; personal or family history of melanoma; and bleeding.

A biopsy for histopathologic evaluation is mandatory when a lesion is suspicious for melanoma. Dermoscopy, which involves a device that magnifies skin lesions, may reveal highly specific dermoscopic features for melanoma that can help in determining the need for biopsy.4

The preferred method for biopsy is complete elliptical excision with 2- to 3-mm margins of normal skin.2,3 However, a deep shave biopsy may also be appropriate, depending upon the clinical situation and physician experience with the technique.4

A deep shave biopsy is less time consuming than elliptical excision, making it easier to perform at the time the lesion is first evaluated. Deep shave biopsy may provide several benefits, including reducing the amount of normal tissue that is removed (especially if pathology is benign) as well as, the cost, scarring, and likelihood of wound infections. Deep shave biopsy also can avoid the need for a second elliptical excision.7,8

Determine margins, proceed with surgical excision

Early surgical excision is the primary treatment for malignant melanoma. After the diagnosis is confirmed by initial biopsy, the depth of the lesion dictates the surgical recommendations. Recommended surgical margins based on depth are: 5 mm with a layer of subcutaneous fat for melanoma in situ, 1 cm down to the fascia for lesions with a Breslow depth ≤2 mm, and 2 cm down to the fascia for lesions with a depth >2 mm.1,4

The surgical treatment of lentigo maligna melanoma can be challenging due to indistinct borders and large size. Mohs micrographic surgery can be helpful to fully remove the lesion with sparing of healthy surrounding tissue.4 When surgical excision of large lentigo maligna is technically difficult, radiation therapy is another option.3

Subungual melanoma may necessitate amputation or grafting of the digit. Mohs micrographic surgery can be useful in these situations for tissue sparing.2 (To learn more, see “When to consider Mohs surgery,” J Fam Pract. 2013;558-564.)

Is a sentinel lymph node biopsy needed?

Sentinel lymph node biopsy is often recommended for melanomas >1 mm in depth.2-4 It provides guidance on who may benefit from regional lymphadenectomy and adjuvant immunotherapy.1,3

Adjuvant therapy for patients without evidence of distant metastases can be considered in patients with positive nodes or node-negative melanoma that is 4 mm thick or Clark Level IV or V. Adjuvant high-dose interferon alpha-2b is the most commonly used agent in these situations.2 Some studies suggest an increase in median overall survival of up to 11 months with high-dose interferon as compared to no treatment.3 Limitations include toxicity from these high-dose regimens.3 Treatment with interferon does not represent a cure; rather, it should be considered a palliative intervention with marginal benefit.1

When there are distant metastases…

Once distant metastases are identified, the goal of therapy should be palliative care as this condition is generally incurable. Chemotherapy, radiation, and excision of solitary metastases are all interventions that have traditionally been employed.1 The primary site for metastasis is the skin, but all organs are potential sites of spread. Central nervous system metastasis is the most common cause of the death.2

Novel therapies include inhibition of BRAF, an enzyme of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (MAPK), and blocking of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4).

BRAF-enzyme inhibitor. Mutated BRAF contributes to uncontrolled cell growth and resistance to programmed cell death (apoptosis).9,10 In August 2011, vemurafenib (Zelboraf ), a BRAF-enzyme inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of late-stage melanoma. It works only in patients with the BRAFV600E mutation, which is found in approximately 60% of melanomas.11,12 One phase 1 study showed partial to complete regression in 80% of patients treated, but this regression lasted only 2 to 18 months.13

Anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes can recognize and potentially destroy cancer cells.14 However, CTLA-4, which is expressed on the surface of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, has a suppressive effect on the T-lymphocyte response after interaction with the antigen-presenting cell. Researchers deduced that blocking CTLA-4 would allow the immune system to remain responsive to abnormal antigens, including those from melanoma.9

Ipilimumab (Yervoy), an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, was approved by the FDA in March 2011 for the treatment of late-stage melanoma.11 Partial and complete responses have been shown in trials of ipilimumab as monotherapy and in combination with vaccines, chemotherapy, and interleukin-2, but these responses have not been sustained.9

Although these novel therapies represent significant advancements in the understanding of the pathogenesis of melanoma, the short duration of efficacy highlights the cancer’s ability to develop resistance to these treatments. This ability to adapt suggests that melanoma harbors multiple oncogenes and several pathways for carcinogenesis. Combination targeted therapies may be required to improve clinical results; research is ongoing.9 Toxicities associated with these medications are also a limiting factor.

What about vaccines? Vaccine studies are also ongoing. Although some have shown promising results, no clearly effective therapy has been produced to date.2

Factors that affect prognosis

The prognosis for melanoma is related to tumor thickness, presence or absence of melanoma in regional lymph nodes, and extent of metastases.1-4 The TNM classification system takes these factors into account in staging melanoma.4 Based on this staging, a 5- and 10-year survival estimate can be discussed with the patient.

Survival estimates based on depth of invasion alone are also used. As an example, one study cited a 5-year survival rate of 95% for a tumor thickness <.75 mm; 85% (.75-1.4 mm); 66% (1.5-3.9 mm); and 46% (≥4 mm).1

Other variables that affect prognosis include lymphocytic infiltrate (more brisk and tumor infiltrating is better prognostically), mitotic rate (less is better; >6/mm2 is worse), ulceration (worse prognostically), and regression of the tumor.2 Regression will appear as areas of depigmentation in a previously completely pigmented lesion; it is associated with a poorer prognosis.1

Follow-up with patients is key

Regular skin, lymph node, and general follow-up exams are recommended to detect metastatic disease or new primary lesions. It has been estimated that approximately 5% of patients with a history of melanoma will develop a new primary lesion.3 Lab and imaging studies should be used when prompted by clinical findings.2

Some protocols recommend routine use of labs, including lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood count, and chemistries, as well as imaging such as chest x-ray, positron emission tomography (PET), or computed tomography (CT) based on the stage of the disease.4 No evidence has shown that routine laboratory or imaging studies affect prognosis.2

Close surveillance for my patient

My patient underwent re-excision of the tumor site with wide margins. Sentinel lymph nodes excised from the bilateral axilla were negative for melanoma. He was seen by colleagues in the oncology department, and his lab work and chest x-ray were normal. PET/CT revealed no evidence of fluorodeoxyglucose avid metastatic disease.

Based on staging, my patient’s 5-year survival was estimated at 81% and his 10-year survival at 67%. No further oncology follow-up was planned and the patient was instructed to be seen by a dermatologist for close clinical surveillance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Suresh K. Menon, MD, Hahn Medical Practices, 5078 Williamsport Pike, Martinsburg, WV 25404; [email protected]

1. Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, Clayton E, et al. Melanoma. In: Hefta J, Noujaim SR, Edmonson KG, eds. 20 Common Problems in Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000:201-217.

2. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Melanoma (malignant melanoma). In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:694-699.

3. Marks JG, Miller JJ. Malignant melanoma. In: Marks JG, Miller JJ, Lookingbill DP, eds. Principles of Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:78-81.

4. Shenenberger DW. Cutaneous malignant melanoma: a primary care perspective. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:161-168.

5. Melanoma surveillance in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/what_cdc_is_doing/melanoma_supplement.htm. Accessed October 11, 2013.

6. Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, et al, eds. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH Pub. No. 06-5767; 2006.

7. Usatine RP, Pfenninger JL, Stulberg DL, et al. Choosing the biopsy type. In: Usatine RP, Pfenninger, JL, Stulberg DL, et al, eds. Dermatologic and Cosmetic Procedures in Office Practice. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011: 75.

8. Usatine RP, Pfenninger JL, Stulberg DL, et al. The shave biopsy. In: Usatine RP, Pfenninger, JL, Stulberg DL, et al, eds. Dermatologic and Cosmetic Procedures in Office Practice. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011: 88.

9. Weber, JS. A New Era Approaches: Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Malignant Melanoma. Medscape Education Web site. Available at: http://www.medscape.org/viewprogram/17800. Accessed July 7, 2012.

10. Shao Y, Aplin AE. Akt3-mediated resistance to apoptosis in B-RAF-targeted melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6670-6681.

11. Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435.

12. Halaban R, Zhang W, Bacchiocchi A, et al. PLX4032, a selective BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor, activates the ERK pathway and enhances cell migration and proliferation of BRAF melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:190-200.

13. Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809-819.

14. Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2517-2519.

1. Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, Clayton E, et al. Melanoma. In: Hefta J, Noujaim SR, Edmonson KG, eds. 20 Common Problems in Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000:201-217.

2. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Melanoma (malignant melanoma). In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:694-699.

3. Marks JG, Miller JJ. Malignant melanoma. In: Marks JG, Miller JJ, Lookingbill DP, eds. Principles of Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:78-81.

4. Shenenberger DW. Cutaneous malignant melanoma: a primary care perspective. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:161-168.

5. Melanoma surveillance in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/what_cdc_is_doing/melanoma_supplement.htm. Accessed October 11, 2013.

6. Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, et al, eds. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH Pub. No. 06-5767; 2006.

7. Usatine RP, Pfenninger JL, Stulberg DL, et al. Choosing the biopsy type. In: Usatine RP, Pfenninger, JL, Stulberg DL, et al, eds. Dermatologic and Cosmetic Procedures in Office Practice. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011: 75.

8. Usatine RP, Pfenninger JL, Stulberg DL, et al. The shave biopsy. In: Usatine RP, Pfenninger, JL, Stulberg DL, et al, eds. Dermatologic and Cosmetic Procedures in Office Practice. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011: 88.

9. Weber, JS. A New Era Approaches: Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Malignant Melanoma. Medscape Education Web site. Available at: http://www.medscape.org/viewprogram/17800. Accessed July 7, 2012.

10. Shao Y, Aplin AE. Akt3-mediated resistance to apoptosis in B-RAF-targeted melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6670-6681.

11. Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435.

12. Halaban R, Zhang W, Bacchiocchi A, et al. PLX4032, a selective BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor, activates the ERK pathway and enhances cell migration and proliferation of BRAF melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:190-200.

13. Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809-819.

14. Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2517-2519.

Earache

The FP diagnosed acute otitis externa (OE), secondary to the ear canal damage done by using the new hearing aid. Note the viscous purulent discharge and narrowing of the ear canal.

In general, the management of acute OE should include an assessment of pain. The physician should recommend or prescribe analgesic treatment based on the severity of pain. Topical treatments alone are effective for uncomplicated acute OE. Additional oral antibiotics are usually not required.

There is some evidence indicating that patients treated with topical preparations containing antibiotics and steroids see improvements in swelling, redness, secretion, and analgesic consumption compared with preparations without steroids. Topical aluminum acetate may be as effective as a topical antibiotic/steroid at improving cure rates in people with acute OE.

Patients prescribed antibiotic/steroid drops can expect their symptoms to last for approximately 6 days after treatment begins. When prescribing ear drops, instruct patients to use them for at least a week. If they have symptoms beyond the first week, they should continue the drops until their symptoms resolve--and possibly for a few days longer--for a maximum of 2 weeks (total).

In this case, the patient was instructed to remove the hearing aid and to start a topical antibiotic. He also received treatment for the pain.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Roy F. Sullivan and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed acute otitis externa (OE), secondary to the ear canal damage done by using the new hearing aid. Note the viscous purulent discharge and narrowing of the ear canal.

In general, the management of acute OE should include an assessment of pain. The physician should recommend or prescribe analgesic treatment based on the severity of pain. Topical treatments alone are effective for uncomplicated acute OE. Additional oral antibiotics are usually not required.

There is some evidence indicating that patients treated with topical preparations containing antibiotics and steroids see improvements in swelling, redness, secretion, and analgesic consumption compared with preparations without steroids. Topical aluminum acetate may be as effective as a topical antibiotic/steroid at improving cure rates in people with acute OE.

Patients prescribed antibiotic/steroid drops can expect their symptoms to last for approximately 6 days after treatment begins. When prescribing ear drops, instruct patients to use them for at least a week. If they have symptoms beyond the first week, they should continue the drops until their symptoms resolve--and possibly for a few days longer--for a maximum of 2 weeks (total).

In this case, the patient was instructed to remove the hearing aid and to start a topical antibiotic. He also received treatment for the pain.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Roy F. Sullivan and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed acute otitis externa (OE), secondary to the ear canal damage done by using the new hearing aid. Note the viscous purulent discharge and narrowing of the ear canal.

In general, the management of acute OE should include an assessment of pain. The physician should recommend or prescribe analgesic treatment based on the severity of pain. Topical treatments alone are effective for uncomplicated acute OE. Additional oral antibiotics are usually not required.

There is some evidence indicating that patients treated with topical preparations containing antibiotics and steroids see improvements in swelling, redness, secretion, and analgesic consumption compared with preparations without steroids. Topical aluminum acetate may be as effective as a topical antibiotic/steroid at improving cure rates in people with acute OE.

Patients prescribed antibiotic/steroid drops can expect their symptoms to last for approximately 6 days after treatment begins. When prescribing ear drops, instruct patients to use them for at least a week. If they have symptoms beyond the first week, they should continue the drops until their symptoms resolve--and possibly for a few days longer--for a maximum of 2 weeks (total).

In this case, the patient was instructed to remove the hearing aid and to start a topical antibiotic. He also received treatment for the pain.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Roy F. Sullivan and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Rash around ear

The FP diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis, which can cause erythema and greasy scale of the external ear and ear canal. The seborrheic dermatitis itself causes breaks in the skin and the coexisting pruritus may lead a patient to damage his or her ear canal while scratching with a Q-tip or other implement. Scratching in this manner also puts the patient at risk for a secondary infection. Fortunately, the patient in this case did not have a secondary infection.

Treatment for seborrhea anywhere on the skin or scalp involves decreasing the Malassezia overgrowth with antifungal agents and using a topical steroid to control the inflammation. Typical antifungal agents include dandruff shampoos with selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, or ketoconazole. Patients are directed to use the shampoo on their hair and scalp and then apply the lather to other affected areas such as the ears. It helps if this is done daily or every other day.

Low-potency topical steroids are sufficient to treat the inflammation of seborrhea in most cases. Studies show that desonide cream or lotion is a good choice for seborrheic dermatitis. Topical antifungal creams including the azoles may also be used, if needed.

This patient was treated with OTC selenium sulfide shampoo and topical desonide lotion with good results.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Eric Kraus and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis, which can cause erythema and greasy scale of the external ear and ear canal. The seborrheic dermatitis itself causes breaks in the skin and the coexisting pruritus may lead a patient to damage his or her ear canal while scratching with a Q-tip or other implement. Scratching in this manner also puts the patient at risk for a secondary infection. Fortunately, the patient in this case did not have a secondary infection.

Treatment for seborrhea anywhere on the skin or scalp involves decreasing the Malassezia overgrowth with antifungal agents and using a topical steroid to control the inflammation. Typical antifungal agents include dandruff shampoos with selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, or ketoconazole. Patients are directed to use the shampoo on their hair and scalp and then apply the lather to other affected areas such as the ears. It helps if this is done daily or every other day.

Low-potency topical steroids are sufficient to treat the inflammation of seborrhea in most cases. Studies show that desonide cream or lotion is a good choice for seborrheic dermatitis. Topical antifungal creams including the azoles may also be used, if needed.

This patient was treated with OTC selenium sulfide shampoo and topical desonide lotion with good results.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Eric Kraus and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis, which can cause erythema and greasy scale of the external ear and ear canal. The seborrheic dermatitis itself causes breaks in the skin and the coexisting pruritus may lead a patient to damage his or her ear canal while scratching with a Q-tip or other implement. Scratching in this manner also puts the patient at risk for a secondary infection. Fortunately, the patient in this case did not have a secondary infection.

Treatment for seborrhea anywhere on the skin or scalp involves decreasing the Malassezia overgrowth with antifungal agents and using a topical steroid to control the inflammation. Typical antifungal agents include dandruff shampoos with selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, or ketoconazole. Patients are directed to use the shampoo on their hair and scalp and then apply the lather to other affected areas such as the ears. It helps if this is done daily or every other day.

Low-potency topical steroids are sufficient to treat the inflammation of seborrhea in most cases. Studies show that desonide cream or lotion is a good choice for seborrheic dermatitis. Topical antifungal creams including the azoles may also be used, if needed.

This patient was treated with OTC selenium sulfide shampoo and topical desonide lotion with good results.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Eric Kraus and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

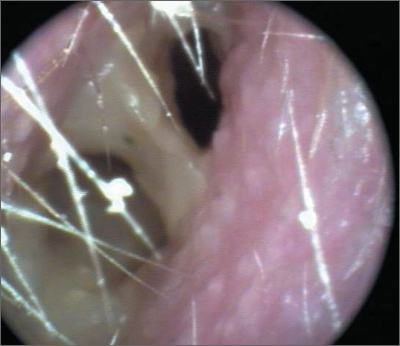

Draining ear

The patient had chronic suppurative otitis media with purulent discharge. The FP started the patient on amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg bid for 10 days and referred him to an ear nose and throat (ENT) specialist. The ENT ordered a computed tomography scan to see if the patient had a cholesteatoma, but did not find any evidence of one.

When the acute infection cleared, the ear canal was cleaned with an operating microscope and a perforated tympanic membrane (TM) was found. The patient opted to have a tympanoplasty to repair his TM.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient had chronic suppurative otitis media with purulent discharge. The FP started the patient on amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg bid for 10 days and referred him to an ear nose and throat (ENT) specialist. The ENT ordered a computed tomography scan to see if the patient had a cholesteatoma, but did not find any evidence of one.

When the acute infection cleared, the ear canal was cleaned with an operating microscope and a perforated tympanic membrane (TM) was found. The patient opted to have a tympanoplasty to repair his TM.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient had chronic suppurative otitis media with purulent discharge. The FP started the patient on amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg bid for 10 days and referred him to an ear nose and throat (ENT) specialist. The ENT ordered a computed tomography scan to see if the patient had a cholesteatoma, but did not find any evidence of one.

When the acute infection cleared, the ear canal was cleaned with an operating microscope and a perforated tympanic membrane (TM) was found. The patient opted to have a tympanoplasty to repair his TM.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Hearing loss

The FP consulted an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) colleague and the patient was admitted to the hospital with a presumptive diagnosis of malignant otitis externa. The patient’s diabetes was also out of control. The necrotizing or malignant form of otitis externa is defined by destruction of the temporal bone, usually in patients with diabetes or those who are immunocompromised. It is often life threatening.

In this case, a computed tomography scan showed some destruction of the temporal bone. The patient was started on IV ciprofloxacin and the ear culture grew out Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive to ciprofloxacin. The patient responded well to treatment for the otitis externa (and to treatment for her diabetes); she went home on oral ciprofloxacin 5 days later.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of EJ Mayaeux, Jr, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP consulted an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) colleague and the patient was admitted to the hospital with a presumptive diagnosis of malignant otitis externa. The patient’s diabetes was also out of control. The necrotizing or malignant form of otitis externa is defined by destruction of the temporal bone, usually in patients with diabetes or those who are immunocompromised. It is often life threatening.

In this case, a computed tomography scan showed some destruction of the temporal bone. The patient was started on IV ciprofloxacin and the ear culture grew out Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive to ciprofloxacin. The patient responded well to treatment for the otitis externa (and to treatment for her diabetes); she went home on oral ciprofloxacin 5 days later.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of EJ Mayaeux, Jr, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala B. Otitis externa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:180-184.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/