User login

Jaw pain

The FP diagnosed the masses as torus mandibularis caused by bony exostoses. These masses look like a torus palatinus and have the same pathophysiology. However, they are usually bilateral rather than at the midline.

Although this patient had multiple untreated dental problems, the tori were an incidental finding and the pain was due to her severe dental caries. There were no signs of a dental abscess, so the patient was referred to a dentist for dental extractions; no antibiotics were prescribed. The patient was also counseled about the importance of good oral hygiene. Surgical excision of the tori was not indicated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Smith M. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:206-207.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed the masses as torus mandibularis caused by bony exostoses. These masses look like a torus palatinus and have the same pathophysiology. However, they are usually bilateral rather than at the midline.

Although this patient had multiple untreated dental problems, the tori were an incidental finding and the pain was due to her severe dental caries. There were no signs of a dental abscess, so the patient was referred to a dentist for dental extractions; no antibiotics were prescribed. The patient was also counseled about the importance of good oral hygiene. Surgical excision of the tori was not indicated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Smith M. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:206-207.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed the masses as torus mandibularis caused by bony exostoses. These masses look like a torus palatinus and have the same pathophysiology. However, they are usually bilateral rather than at the midline.

Although this patient had multiple untreated dental problems, the tori were an incidental finding and the pain was due to her severe dental caries. There were no signs of a dental abscess, so the patient was referred to a dentist for dental extractions; no antibiotics were prescribed. The patient was also counseled about the importance of good oral hygiene. Surgical excision of the tori was not indicated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Smith M. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:206-207.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Mass on hard palate

The FP explained that the mass was a torus palatinus and that nothing needed to be done about it.

Torus palatinus is a benign bony exostosis occurring in the midline of the hard palate. It is the most common bony maxillofacial exostosis, and it is usually diagnosed in adults older than 30 years of age. It is more common in women than men.

The differential diagnosis for a mass in this location includes an adenoid cystic carcinoma, a rare tumor that can start in a minor salivary gland over the hard palate. Note, however, that this tumor will not occur at the midline. If a suspected torus is not midline, a biopsy will be needed to rule out this potentially fatal carcinoma. Excision of a torus is only indicated if the lesion interferes with function, such as the fit of dentures or phonation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Smith M. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:206-207.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained that the mass was a torus palatinus and that nothing needed to be done about it.

Torus palatinus is a benign bony exostosis occurring in the midline of the hard palate. It is the most common bony maxillofacial exostosis, and it is usually diagnosed in adults older than 30 years of age. It is more common in women than men.

The differential diagnosis for a mass in this location includes an adenoid cystic carcinoma, a rare tumor that can start in a minor salivary gland over the hard palate. Note, however, that this tumor will not occur at the midline. If a suspected torus is not midline, a biopsy will be needed to rule out this potentially fatal carcinoma. Excision of a torus is only indicated if the lesion interferes with function, such as the fit of dentures or phonation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Smith M. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:206-207.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained that the mass was a torus palatinus and that nothing needed to be done about it.

Torus palatinus is a benign bony exostosis occurring in the midline of the hard palate. It is the most common bony maxillofacial exostosis, and it is usually diagnosed in adults older than 30 years of age. It is more common in women than men.

The differential diagnosis for a mass in this location includes an adenoid cystic carcinoma, a rare tumor that can start in a minor salivary gland over the hard palate. Note, however, that this tumor will not occur at the midline. If a suspected torus is not midline, a biopsy will be needed to rule out this potentially fatal carcinoma. Excision of a torus is only indicated if the lesion interferes with function, such as the fit of dentures or phonation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Smith M. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:206-207.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Recurrent vesicular eruption on the right hand

The parents of an 8-year-old boy brought their son to our clinic because they were worried about the recurrent painful lesions on the pinkie, ring, and middle fingers of his right hand (FIGURE 1A and 1B). The lesions, which had recurred monthly for the past 3 years, typically lasted a few days and then spontaneously resolved.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

The diagnosis: Herpetic whitlow

Herpetic whitlow, or herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the hand, was first reported by Adamson in 1909.1 Herpes infection of the hand classically has a bimodal age distribution. It may be seen in children younger than 10 years of age or in adults between 20 and 30 years of age.2 In children, it is caused almost exclusively by HSV-1, whereas in adults it can be caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2.2,3

HSV infection of the hand classically occurs as a result of autoinoculation following herpetic gingivostomatitis. After inoculation, the virus has an incubation period of 2 to 20 days before vesicles appear.4 The appearance of the lesions is associated with intense throbbing pain. Fever and systemic symptoms are rare.

What you’ll see. Patients with herpetic whitlow will develop a single vesicle or cluster of vesicles on a single digit a few days after their skin has been irritated or exposed to minor trauma.2,4 Vesicles are typically clear in color and have an erythematous base. However, they are often superinfected with bacteria and may exhibit signs of impetiginization. The most common location of the vesicles is on the terminal phalanx of the thumb, index, or middle finger.3

Differential includes dactylitis

Painful fingers may also be suggestive of dactylitis.

Blistering distal dactylitis, mostly caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococci, is a bacterial infection that manifests as a tense bullae over the anterior fat pad of the volar aspect of the distal part of a single finger (or rarely a toe); diagnosis is usually confirmed by culture.5

Sickle cell dactylitis, or hand-foot syndrome, is caused by localized bone marrow infarction of the carpal and tarsal bones and phalanges. Patients will complain of a sudden onset of warm, tender global swelling of the hands and/or feet that is occasionally accompanied by fever and leucocytosis.5

Spondyloarthritis dactylitis, or a “sausage-like” digit, is usually caused by flexor tenosynovitis and presents as diffuse painful swelling of the fingers and toes, mainly over the flexor tendons.5

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of herpetic whitlow is clinical. If the diagnosis is unclear, diagnostic tests can include viral culture, serum antibody titers, a Tzanck smear, lesion specimen antigen testing, or histopathologic examinations. In this case, swab cultures revealed moderate growth of group A b-hemolytic streptococci. Fungal smears and cultures were negative. Histopathology revealed intraepidermal vesiculation with ballooning and reticular degeneration and cytopathic changes of herpetic infection.

The natural history of the untreated, uncomplicated herpetic whitlow is complete clearance within 2 to 3 weeks.4 Rare complications include systemic viremia, ocular infection, nail dystrophy, nail loss, scarring, and localized hyperesthesia or hypoesthesia.2,4,6,7

Treatment with acyclovir

Oral acyclovir (2 g/day in 3 doses for 10 days) taken during the prodromal stage of recurrent HSV-2 herpetic whitlow has been shown to reduce the duration of symptoms from 10.1 to 3.7 days.8 Prophylactic use of oral acyclovir (200 mg, 4 times daily for up to 2 years) has been shown to be effective in suppressing recurrent HSV infection of nongenital skin.9

A good outcome

Our patient was given a 10-day course of acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily and cefadroxil 500 mg orally twice daily (for superimposed bacterial infection). The lesions had completely disappeared upon follow-up 2 weeks later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ossama Abbas, MD, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Riad El Solh/Beirut, Lebanon; [email protected]

1. Adamson HG. Herpes febrilis attacking the fingers. Br J Dermatol. 1909;21:323-324.

2. Feder HM Jr, Long SS. Herpetic whitlow. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137:861-863.

3. Gill MJ, Arlette J, Tyrrell DL, et al. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. Clinical features and management. Am J Med. 1988;85:53-56.

4. Haedicke GJ, Grossman JA, Fisher AE. Herpetic whitlow of the digits. J Hand Surg Br. 1989;14:443-446.

5. Olivieri I, Scarano E, Padula A, et al. Dactylitis, a term for different digit diseases. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:333-340.

6. Stern H, Elek SD, Millar DM, et al. Herpetic whitlow, a form of cross-infection in hospitals. Lancet. 1959;2:871-874.

7. Fowler JR. Viral infections. Hand Clin. 1989;5:613-627.

8. Gill MJ, Bryant HE. Oral acyclovir therapy of recurrent herpes simplex virus type 2 infection of the hand. Anitmicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:382-383.

9. Rubright JH, Shafritz AB. The herpetic whitlow. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:340-342.

The parents of an 8-year-old boy brought their son to our clinic because they were worried about the recurrent painful lesions on the pinkie, ring, and middle fingers of his right hand (FIGURE 1A and 1B). The lesions, which had recurred monthly for the past 3 years, typically lasted a few days and then spontaneously resolved.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

The diagnosis: Herpetic whitlow

Herpetic whitlow, or herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the hand, was first reported by Adamson in 1909.1 Herpes infection of the hand classically has a bimodal age distribution. It may be seen in children younger than 10 years of age or in adults between 20 and 30 years of age.2 In children, it is caused almost exclusively by HSV-1, whereas in adults it can be caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2.2,3

HSV infection of the hand classically occurs as a result of autoinoculation following herpetic gingivostomatitis. After inoculation, the virus has an incubation period of 2 to 20 days before vesicles appear.4 The appearance of the lesions is associated with intense throbbing pain. Fever and systemic symptoms are rare.

What you’ll see. Patients with herpetic whitlow will develop a single vesicle or cluster of vesicles on a single digit a few days after their skin has been irritated or exposed to minor trauma.2,4 Vesicles are typically clear in color and have an erythematous base. However, they are often superinfected with bacteria and may exhibit signs of impetiginization. The most common location of the vesicles is on the terminal phalanx of the thumb, index, or middle finger.3

Differential includes dactylitis

Painful fingers may also be suggestive of dactylitis.

Blistering distal dactylitis, mostly caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococci, is a bacterial infection that manifests as a tense bullae over the anterior fat pad of the volar aspect of the distal part of a single finger (or rarely a toe); diagnosis is usually confirmed by culture.5

Sickle cell dactylitis, or hand-foot syndrome, is caused by localized bone marrow infarction of the carpal and tarsal bones and phalanges. Patients will complain of a sudden onset of warm, tender global swelling of the hands and/or feet that is occasionally accompanied by fever and leucocytosis.5

Spondyloarthritis dactylitis, or a “sausage-like” digit, is usually caused by flexor tenosynovitis and presents as diffuse painful swelling of the fingers and toes, mainly over the flexor tendons.5

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of herpetic whitlow is clinical. If the diagnosis is unclear, diagnostic tests can include viral culture, serum antibody titers, a Tzanck smear, lesion specimen antigen testing, or histopathologic examinations. In this case, swab cultures revealed moderate growth of group A b-hemolytic streptococci. Fungal smears and cultures were negative. Histopathology revealed intraepidermal vesiculation with ballooning and reticular degeneration and cytopathic changes of herpetic infection.

The natural history of the untreated, uncomplicated herpetic whitlow is complete clearance within 2 to 3 weeks.4 Rare complications include systemic viremia, ocular infection, nail dystrophy, nail loss, scarring, and localized hyperesthesia or hypoesthesia.2,4,6,7

Treatment with acyclovir

Oral acyclovir (2 g/day in 3 doses for 10 days) taken during the prodromal stage of recurrent HSV-2 herpetic whitlow has been shown to reduce the duration of symptoms from 10.1 to 3.7 days.8 Prophylactic use of oral acyclovir (200 mg, 4 times daily for up to 2 years) has been shown to be effective in suppressing recurrent HSV infection of nongenital skin.9

A good outcome

Our patient was given a 10-day course of acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily and cefadroxil 500 mg orally twice daily (for superimposed bacterial infection). The lesions had completely disappeared upon follow-up 2 weeks later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ossama Abbas, MD, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Riad El Solh/Beirut, Lebanon; [email protected]

The parents of an 8-year-old boy brought their son to our clinic because they were worried about the recurrent painful lesions on the pinkie, ring, and middle fingers of his right hand (FIGURE 1A and 1B). The lesions, which had recurred monthly for the past 3 years, typically lasted a few days and then spontaneously resolved.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

The diagnosis: Herpetic whitlow

Herpetic whitlow, or herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the hand, was first reported by Adamson in 1909.1 Herpes infection of the hand classically has a bimodal age distribution. It may be seen in children younger than 10 years of age or in adults between 20 and 30 years of age.2 In children, it is caused almost exclusively by HSV-1, whereas in adults it can be caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2.2,3

HSV infection of the hand classically occurs as a result of autoinoculation following herpetic gingivostomatitis. After inoculation, the virus has an incubation period of 2 to 20 days before vesicles appear.4 The appearance of the lesions is associated with intense throbbing pain. Fever and systemic symptoms are rare.

What you’ll see. Patients with herpetic whitlow will develop a single vesicle or cluster of vesicles on a single digit a few days after their skin has been irritated or exposed to minor trauma.2,4 Vesicles are typically clear in color and have an erythematous base. However, they are often superinfected with bacteria and may exhibit signs of impetiginization. The most common location of the vesicles is on the terminal phalanx of the thumb, index, or middle finger.3

Differential includes dactylitis

Painful fingers may also be suggestive of dactylitis.

Blistering distal dactylitis, mostly caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococci, is a bacterial infection that manifests as a tense bullae over the anterior fat pad of the volar aspect of the distal part of a single finger (or rarely a toe); diagnosis is usually confirmed by culture.5

Sickle cell dactylitis, or hand-foot syndrome, is caused by localized bone marrow infarction of the carpal and tarsal bones and phalanges. Patients will complain of a sudden onset of warm, tender global swelling of the hands and/or feet that is occasionally accompanied by fever and leucocytosis.5

Spondyloarthritis dactylitis, or a “sausage-like” digit, is usually caused by flexor tenosynovitis and presents as diffuse painful swelling of the fingers and toes, mainly over the flexor tendons.5

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of herpetic whitlow is clinical. If the diagnosis is unclear, diagnostic tests can include viral culture, serum antibody titers, a Tzanck smear, lesion specimen antigen testing, or histopathologic examinations. In this case, swab cultures revealed moderate growth of group A b-hemolytic streptococci. Fungal smears and cultures were negative. Histopathology revealed intraepidermal vesiculation with ballooning and reticular degeneration and cytopathic changes of herpetic infection.

The natural history of the untreated, uncomplicated herpetic whitlow is complete clearance within 2 to 3 weeks.4 Rare complications include systemic viremia, ocular infection, nail dystrophy, nail loss, scarring, and localized hyperesthesia or hypoesthesia.2,4,6,7

Treatment with acyclovir

Oral acyclovir (2 g/day in 3 doses for 10 days) taken during the prodromal stage of recurrent HSV-2 herpetic whitlow has been shown to reduce the duration of symptoms from 10.1 to 3.7 days.8 Prophylactic use of oral acyclovir (200 mg, 4 times daily for up to 2 years) has been shown to be effective in suppressing recurrent HSV infection of nongenital skin.9

A good outcome

Our patient was given a 10-day course of acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily and cefadroxil 500 mg orally twice daily (for superimposed bacterial infection). The lesions had completely disappeared upon follow-up 2 weeks later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ossama Abbas, MD, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Riad El Solh/Beirut, Lebanon; [email protected]

1. Adamson HG. Herpes febrilis attacking the fingers. Br J Dermatol. 1909;21:323-324.

2. Feder HM Jr, Long SS. Herpetic whitlow. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137:861-863.

3. Gill MJ, Arlette J, Tyrrell DL, et al. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. Clinical features and management. Am J Med. 1988;85:53-56.

4. Haedicke GJ, Grossman JA, Fisher AE. Herpetic whitlow of the digits. J Hand Surg Br. 1989;14:443-446.

5. Olivieri I, Scarano E, Padula A, et al. Dactylitis, a term for different digit diseases. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:333-340.

6. Stern H, Elek SD, Millar DM, et al. Herpetic whitlow, a form of cross-infection in hospitals. Lancet. 1959;2:871-874.

7. Fowler JR. Viral infections. Hand Clin. 1989;5:613-627.

8. Gill MJ, Bryant HE. Oral acyclovir therapy of recurrent herpes simplex virus type 2 infection of the hand. Anitmicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:382-383.

9. Rubright JH, Shafritz AB. The herpetic whitlow. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:340-342.

1. Adamson HG. Herpes febrilis attacking the fingers. Br J Dermatol. 1909;21:323-324.

2. Feder HM Jr, Long SS. Herpetic whitlow. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137:861-863.

3. Gill MJ, Arlette J, Tyrrell DL, et al. Herpes simplex virus infection of the hand. Clinical features and management. Am J Med. 1988;85:53-56.

4. Haedicke GJ, Grossman JA, Fisher AE. Herpetic whitlow of the digits. J Hand Surg Br. 1989;14:443-446.

5. Olivieri I, Scarano E, Padula A, et al. Dactylitis, a term for different digit diseases. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:333-340.

6. Stern H, Elek SD, Millar DM, et al. Herpetic whitlow, a form of cross-infection in hospitals. Lancet. 1959;2:871-874.

7. Fowler JR. Viral infections. Hand Clin. 1989;5:613-627.

8. Gill MJ, Bryant HE. Oral acyclovir therapy of recurrent herpes simplex virus type 2 infection of the hand. Anitmicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:382-383.

9. Rubright JH, Shafritz AB. The herpetic whitlow. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:340-342.

Soreness around mouth

The FP diagnosed contact dermatitis (secondary to compulsive lip licking) and angular cheilitis (perlèche) in this patient.

Lip licking can cause a contact dermatitis to the saliva, along with perlèche. Perlèche is derived from the French word, “lecher,” meaning to lick. Patients with atopic dermatitis are predisposed to contact dermatitis, so this should be explored as an underlying factor in cases like this.

This patient was told that she had to stop licking her lips in order to get well. She was also told to apply clotrimazole cream and 1% hydrocortisone ointment twice daily (both available over the counter). Within 2 weeks she was fully healed. The FP recommended that she apply plain petrolatum to her lips should they feel dry.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Usatine R. Angular cheilitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:203-205.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed contact dermatitis (secondary to compulsive lip licking) and angular cheilitis (perlèche) in this patient.

Lip licking can cause a contact dermatitis to the saliva, along with perlèche. Perlèche is derived from the French word, “lecher,” meaning to lick. Patients with atopic dermatitis are predisposed to contact dermatitis, so this should be explored as an underlying factor in cases like this.

This patient was told that she had to stop licking her lips in order to get well. She was also told to apply clotrimazole cream and 1% hydrocortisone ointment twice daily (both available over the counter). Within 2 weeks she was fully healed. The FP recommended that she apply plain petrolatum to her lips should they feel dry.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Usatine R. Angular cheilitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:203-205.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed contact dermatitis (secondary to compulsive lip licking) and angular cheilitis (perlèche) in this patient.

Lip licking can cause a contact dermatitis to the saliva, along with perlèche. Perlèche is derived from the French word, “lecher,” meaning to lick. Patients with atopic dermatitis are predisposed to contact dermatitis, so this should be explored as an underlying factor in cases like this.

This patient was told that she had to stop licking her lips in order to get well. She was also told to apply clotrimazole cream and 1% hydrocortisone ointment twice daily (both available over the counter). Within 2 weeks she was fully healed. The FP recommended that she apply plain petrolatum to her lips should they feel dry.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Usatine R. Angular cheilitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:203-205.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Fissures near mouth

The patient was given a diagnosis of angular cheilitis (perlèche).

Angular cheilitis is an inflammatory lesion of the commissure (or corner) of the lip that is characterized by scaling and fissuring. Maceration is the usual predisposing factor. Microorganisms, most often Candida albicans, can then invade the macerated area.

Historically, the condition has been associated with vitamin B deficiency, but this association is rare in developed countries.

Maceration can be related to poor dentition, deep facial wrinkles, orthodontic treatment, or poorly fitting dentures. Other risk factors include incorrect use of dental floss causing trauma. Human immunodeficiency virus and other types of immunodeficiency may lead to a more severe case of angular cheilitis, with overgrowth of Candida.

In this case, the patient was treated with nonprescription clotrimazole cream and 1% hydrocortisone ointment twice daily. Within 2 weeks she was fully healed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Usatine R. Angular cheilitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:203-205.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was given a diagnosis of angular cheilitis (perlèche).

Angular cheilitis is an inflammatory lesion of the commissure (or corner) of the lip that is characterized by scaling and fissuring. Maceration is the usual predisposing factor. Microorganisms, most often Candida albicans, can then invade the macerated area.

Historically, the condition has been associated with vitamin B deficiency, but this association is rare in developed countries.

Maceration can be related to poor dentition, deep facial wrinkles, orthodontic treatment, or poorly fitting dentures. Other risk factors include incorrect use of dental floss causing trauma. Human immunodeficiency virus and other types of immunodeficiency may lead to a more severe case of angular cheilitis, with overgrowth of Candida.

In this case, the patient was treated with nonprescription clotrimazole cream and 1% hydrocortisone ointment twice daily. Within 2 weeks she was fully healed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Usatine R. Angular cheilitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:203-205.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was given a diagnosis of angular cheilitis (perlèche).

Angular cheilitis is an inflammatory lesion of the commissure (or corner) of the lip that is characterized by scaling and fissuring. Maceration is the usual predisposing factor. Microorganisms, most often Candida albicans, can then invade the macerated area.

Historically, the condition has been associated with vitamin B deficiency, but this association is rare in developed countries.

Maceration can be related to poor dentition, deep facial wrinkles, orthodontic treatment, or poorly fitting dentures. Other risk factors include incorrect use of dental floss causing trauma. Human immunodeficiency virus and other types of immunodeficiency may lead to a more severe case of angular cheilitis, with overgrowth of Candida.

In this case, the patient was treated with nonprescription clotrimazole cream and 1% hydrocortisone ointment twice daily. Within 2 weeks she was fully healed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L, Usatine R. Angular cheilitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:203-205.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Nasal discharge

The FP and the otolaryngologist suspected that the patient had mucormycosis sinusitis.

Mucormycosis is a rare and potentially deadly fungal infection that tends to occur in patients who are immunosuppressed. While it might involve the sinuses, mucormycosis typically involves the brain or lungs. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to survival. Patients are treated with amphotericin B intravenously in the hospital, with an infectious disease consult to help guide therapy. A consultation with an otorhinolaryngologist should be obtained, as surgery may be needed.

In this case, the diagnosis of mucormycosis was confirmed with a biopsy of the involved tissue. The patient was hospitalized and early antifungal treatment saved his life.

Photo courtesy of Randal A. Otto, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sinusitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:197-202.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP and the otolaryngologist suspected that the patient had mucormycosis sinusitis.

Mucormycosis is a rare and potentially deadly fungal infection that tends to occur in patients who are immunosuppressed. While it might involve the sinuses, mucormycosis typically involves the brain or lungs. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to survival. Patients are treated with amphotericin B intravenously in the hospital, with an infectious disease consult to help guide therapy. A consultation with an otorhinolaryngologist should be obtained, as surgery may be needed.

In this case, the diagnosis of mucormycosis was confirmed with a biopsy of the involved tissue. The patient was hospitalized and early antifungal treatment saved his life.

Photo courtesy of Randal A. Otto, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sinusitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:197-202.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP and the otolaryngologist suspected that the patient had mucormycosis sinusitis.

Mucormycosis is a rare and potentially deadly fungal infection that tends to occur in patients who are immunosuppressed. While it might involve the sinuses, mucormycosis typically involves the brain or lungs. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to survival. Patients are treated with amphotericin B intravenously in the hospital, with an infectious disease consult to help guide therapy. A consultation with an otorhinolaryngologist should be obtained, as surgery may be needed.

In this case, the diagnosis of mucormycosis was confirmed with a biopsy of the involved tissue. The patient was hospitalized and early antifungal treatment saved his life.

Photo courtesy of Randal A. Otto, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sinusitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:197-202.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Sinus pressure

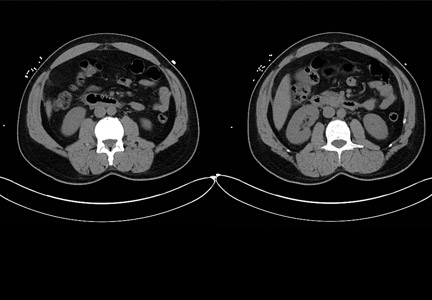

The FP reviewed the CT scan and noted that the patient had air-fluid levels in both maxillary sinuses and loculated fluid on the right side. The patient was given a diagnosis of bilateral maxillary sinusitis that was not responding to the original antibiotic.

The causes of sinusitis include:

○ infection, which is is typically viral (eg, rhinovirus, parainfluenza, influenza), but may be bacterial (eg, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis). In immunocompromised patients, fulminant fungal sinusitis may occur (eg, rhinocerebral mucormycosis).

○ a noninfectious obstruction, which may be the result of allergies, polyposis, barotrauma (eg, deep-sea diving, airplane travel), chemical irritants, tumors, or conditions that alter mucous composition (eg, cystic fibrosis).

Most sinus infections involve the maxillary sinus followed in frequency by the ethmoid (anterior), frontal, and sphenoid sinuses. Of note: Most cases involve more than one sinus. In acute disease, CT scanning is generally reserved for persistent or recurrent symptoms to confirm sinusitis, or to investigate infectious complications. The modest benefit of antibiotics for improving rates of clinical cure or improvement at 7 to 12 days must be weighed against the risks of harm (primarily gastrointestinal, but also skin rash, vaginal discharge, headache, dizziness, and fatigue).

In this case, the FP changed the patient’s antibiotic to amoxicillin/clavulanate and gave her information about nasal saline irrigation for symptom relief. The FP planned to send the patient to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for further evaluation if her symptoms didn’t improve.

Photos courtesy of Chris McMains, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sinusitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:197-202.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP reviewed the CT scan and noted that the patient had air-fluid levels in both maxillary sinuses and loculated fluid on the right side. The patient was given a diagnosis of bilateral maxillary sinusitis that was not responding to the original antibiotic.

The causes of sinusitis include:

○ infection, which is is typically viral (eg, rhinovirus, parainfluenza, influenza), but may be bacterial (eg, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis). In immunocompromised patients, fulminant fungal sinusitis may occur (eg, rhinocerebral mucormycosis).

○ a noninfectious obstruction, which may be the result of allergies, polyposis, barotrauma (eg, deep-sea diving, airplane travel), chemical irritants, tumors, or conditions that alter mucous composition (eg, cystic fibrosis).

Most sinus infections involve the maxillary sinus followed in frequency by the ethmoid (anterior), frontal, and sphenoid sinuses. Of note: Most cases involve more than one sinus. In acute disease, CT scanning is generally reserved for persistent or recurrent symptoms to confirm sinusitis, or to investigate infectious complications. The modest benefit of antibiotics for improving rates of clinical cure or improvement at 7 to 12 days must be weighed against the risks of harm (primarily gastrointestinal, but also skin rash, vaginal discharge, headache, dizziness, and fatigue).

In this case, the FP changed the patient’s antibiotic to amoxicillin/clavulanate and gave her information about nasal saline irrigation for symptom relief. The FP planned to send the patient to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for further evaluation if her symptoms didn’t improve.

Photos courtesy of Chris McMains, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sinusitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:197-202.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP reviewed the CT scan and noted that the patient had air-fluid levels in both maxillary sinuses and loculated fluid on the right side. The patient was given a diagnosis of bilateral maxillary sinusitis that was not responding to the original antibiotic.

The causes of sinusitis include:

○ infection, which is is typically viral (eg, rhinovirus, parainfluenza, influenza), but may be bacterial (eg, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis). In immunocompromised patients, fulminant fungal sinusitis may occur (eg, rhinocerebral mucormycosis).

○ a noninfectious obstruction, which may be the result of allergies, polyposis, barotrauma (eg, deep-sea diving, airplane travel), chemical irritants, tumors, or conditions that alter mucous composition (eg, cystic fibrosis).

Most sinus infections involve the maxillary sinus followed in frequency by the ethmoid (anterior), frontal, and sphenoid sinuses. Of note: Most cases involve more than one sinus. In acute disease, CT scanning is generally reserved for persistent or recurrent symptoms to confirm sinusitis, or to investigate infectious complications. The modest benefit of antibiotics for improving rates of clinical cure or improvement at 7 to 12 days must be weighed against the risks of harm (primarily gastrointestinal, but also skin rash, vaginal discharge, headache, dizziness, and fatigue).

In this case, the FP changed the patient’s antibiotic to amoxicillin/clavulanate and gave her information about nasal saline irrigation for symptom relief. The FP planned to send the patient to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for further evaluation if her symptoms didn’t improve.

Photos courtesy of Chris McMains, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sinusitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:197-202.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

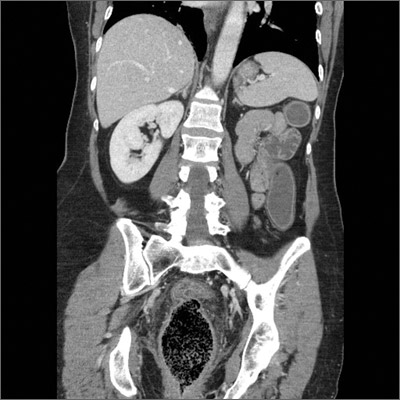

Abrupt onset of abdominal pain

Six days after being discharged from the hospital for treatment of acute pericarditis, a 49-year-old man came to our clinic for a follow-up appointment. The patient still had midsternal chest discomfort and dyspnea. He also reported new epigastric abdominal pain, which had begun 2 days earlier. The patient’s wife indicated that he’d had a low-grade fever since discharge, but the patient denied any chills, hematemesis, melanotic stools, diarrhea, or constipation. The patient’s medical history was significant for gastroesophageal reflux, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, and obesity. Along with newly prescribed indomethacin for the pericarditis (50 mg tid), he was also taking simvastatin. In addition, he occasionally took ibuprofen (800 mg/d) for osteoarthritis of his knee.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Duodenal perforation caused by indomethacin

The CT scans revealed inflammation (arrows, FIGURE 1A) and thickening of the second and third portion of the duodenum and the pres- ence of extraluminal air at the site of the perforation (arrows, FIGURE 1B). There was also free fluid along the right paracolic gutter and into the pelvis. We diagnosed a small intestinal perforation in this patient, which was likely caused by a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer.

How NSAIDs affect the GI tract

NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX), the enzyme responsible for prostaglandin production. Specifically, the COX-1 enzyme is responsible for the production of prostaglandins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Prostaglandins play an important role in protecting the GI mucosa. By inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins, the permeability of the GI tract is increased and the natural protective barrier of the mucosa is destroyed.1

Gastroduodenal damage is a well-known adverse effect of NSAIDs. Ulcers have been noted on upper endoscopy in regular NSAID users, and the risk of developing a symptomatic ulcer and complications increases with every year of regular NSAID use.2 Ulcers in the GI tract can be complicated by perforation.1

Patients will complain of sudden onset abdominal pain

Important clues in the patient history for a perforated GI tract include sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that may present initially as epigastric pain and progress to generalized abdominal pain that may radiate to one or both shoulders.3 Physical exam findings for a perforated GI tract may include abdominal tenderness and rigid abdomen; fever and tachycardia may also be present.3 Concern for possible abdominal perforation should be evaluated with a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and radiographic studies.3

The differential diagnosis of epigastric abdominal pain includes: pancreatitis, gastritis, gastric/duodenal ulcer, and obstruction. Elevated serum lipase levels or CT findings of pancreatic inflammation assist in the diagnosis of pancreatitis. Upper endoscopy is key to identifying cases of gastritis and ulcers in the GI tract. And an abdominal radiograph that shows dilated loops of bowel will confirm suspicions of obstruction.

Stabilize the patientAcute management of GI perforation begins with stabilizing the patient and determining the need for surgical intervention or medical management. Should a patient have a persistent air leak, surgery is the mainstay of treatment.3 If the perforation has healed, the patient should be medically managed.

Therapy may require placing a nasogastric tube and holding any oral intake until abdominal pain and perforation resolves. Medications in the acute treatment should include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and antibiotics. Antibiotics should cover for gram-negative enteric bacteria and anaerobes.

How to prevent NSAID-induced injury.

PPIs used with nonselective NSAIDs appear to reduce the likelihood of gastric ulceration.4 Similarly, H2-receptor antagonists (H2RA) also inhibit gastric acid secretion, and high doses of them significantly reduce the incidence of gastric ulcers.4 However, standard doses of HRAs have not been shown to be effective in reducing the risk of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers.4 Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue that inhibits gastric secretion and protects the gastric mucosa is also an option; it has been used in combination with nonselective NSAIDs to counteract the increase in GI permeability.4

What about using COX-2 inhibitors instead? The COX-2 inhibitors have a lower risk of gastrointestinal tract injury.2 Gastric ulcers, GI bleeding, and complications from ulcers have been shown to be less common with COX-2 NSAIDs compared with nonselective NSAIDs.5 A review of the literature suggests that for patients with previous GI bleeding, COX-2 inhibitors are comparable to an NSAID paired with a PPI in preventing GI bleeding; pairing a COX-2 inhibitor with a PPI, however, appears to provide the greatest defense.2,4

Consider preventive steps. Patients at risk for complications are likely to benefit from the simultaneous use of prophylactic agents with NSAID therapy. Risk factors for NSAID-related GI complications include: a previous GI event; older age; simultaneous use of anticoagulants, corticosteroids, or other NSAIDs (including low-dose aspirin); high-dose NSAID therapy; and chronic debilitating disorders (especially cardiovascular disease).6

Our patient improved with medical management

Our patient was evaluated by general surgery during his hospital admission, but because he was stable—with a healing duodenal perforation—we opted to manage him medically. We started him on esomeprazole (40 mg bid) along with ciprofloxacin (500 mg bid) and metronidazole (500 mg tid) for the microperforation of the duodenum. The patient was also scheduled for an outpatient endoscopic evaluation.

1. Park SC, Chun HJ, Kang CD, et al. Prevention and management of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-induced small intestinal injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4647-4653.

2. Ng SC, Chan F. NSAID-induced gastrointestinal and car- diovascular injury. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26: 611-617.

3. Lawrence PF, Bell RM, TM, et al. Essentials of General Surgery. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. 4. Hooper, L, Brown TJ, Elliott R, et al. The effectiveness of five strategies for the prevention of gastrointestinal toxicity in-duced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329:948.

5. Rostom A, Muir K, Dube C, et al. Prevention of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a meta-analysis of traditional NSAIDs with gastroprotection and COX-2-inhibitors. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2009;1:47-71.

6. Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gatroenterology. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gas- troenterol. 2009;104:728-738.

Six days after being discharged from the hospital for treatment of acute pericarditis, a 49-year-old man came to our clinic for a follow-up appointment. The patient still had midsternal chest discomfort and dyspnea. He also reported new epigastric abdominal pain, which had begun 2 days earlier. The patient’s wife indicated that he’d had a low-grade fever since discharge, but the patient denied any chills, hematemesis, melanotic stools, diarrhea, or constipation. The patient’s medical history was significant for gastroesophageal reflux, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, and obesity. Along with newly prescribed indomethacin for the pericarditis (50 mg tid), he was also taking simvastatin. In addition, he occasionally took ibuprofen (800 mg/d) for osteoarthritis of his knee.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Duodenal perforation caused by indomethacin

The CT scans revealed inflammation (arrows, FIGURE 1A) and thickening of the second and third portion of the duodenum and the pres- ence of extraluminal air at the site of the perforation (arrows, FIGURE 1B). There was also free fluid along the right paracolic gutter and into the pelvis. We diagnosed a small intestinal perforation in this patient, which was likely caused by a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer.

How NSAIDs affect the GI tract

NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX), the enzyme responsible for prostaglandin production. Specifically, the COX-1 enzyme is responsible for the production of prostaglandins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Prostaglandins play an important role in protecting the GI mucosa. By inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins, the permeability of the GI tract is increased and the natural protective barrier of the mucosa is destroyed.1

Gastroduodenal damage is a well-known adverse effect of NSAIDs. Ulcers have been noted on upper endoscopy in regular NSAID users, and the risk of developing a symptomatic ulcer and complications increases with every year of regular NSAID use.2 Ulcers in the GI tract can be complicated by perforation.1

Patients will complain of sudden onset abdominal pain

Important clues in the patient history for a perforated GI tract include sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that may present initially as epigastric pain and progress to generalized abdominal pain that may radiate to one or both shoulders.3 Physical exam findings for a perforated GI tract may include abdominal tenderness and rigid abdomen; fever and tachycardia may also be present.3 Concern for possible abdominal perforation should be evaluated with a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and radiographic studies.3

The differential diagnosis of epigastric abdominal pain includes: pancreatitis, gastritis, gastric/duodenal ulcer, and obstruction. Elevated serum lipase levels or CT findings of pancreatic inflammation assist in the diagnosis of pancreatitis. Upper endoscopy is key to identifying cases of gastritis and ulcers in the GI tract. And an abdominal radiograph that shows dilated loops of bowel will confirm suspicions of obstruction.

Stabilize the patientAcute management of GI perforation begins with stabilizing the patient and determining the need for surgical intervention or medical management. Should a patient have a persistent air leak, surgery is the mainstay of treatment.3 If the perforation has healed, the patient should be medically managed.

Therapy may require placing a nasogastric tube and holding any oral intake until abdominal pain and perforation resolves. Medications in the acute treatment should include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and antibiotics. Antibiotics should cover for gram-negative enteric bacteria and anaerobes.

How to prevent NSAID-induced injury.

PPIs used with nonselective NSAIDs appear to reduce the likelihood of gastric ulceration.4 Similarly, H2-receptor antagonists (H2RA) also inhibit gastric acid secretion, and high doses of them significantly reduce the incidence of gastric ulcers.4 However, standard doses of HRAs have not been shown to be effective in reducing the risk of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers.4 Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue that inhibits gastric secretion and protects the gastric mucosa is also an option; it has been used in combination with nonselective NSAIDs to counteract the increase in GI permeability.4

What about using COX-2 inhibitors instead? The COX-2 inhibitors have a lower risk of gastrointestinal tract injury.2 Gastric ulcers, GI bleeding, and complications from ulcers have been shown to be less common with COX-2 NSAIDs compared with nonselective NSAIDs.5 A review of the literature suggests that for patients with previous GI bleeding, COX-2 inhibitors are comparable to an NSAID paired with a PPI in preventing GI bleeding; pairing a COX-2 inhibitor with a PPI, however, appears to provide the greatest defense.2,4

Consider preventive steps. Patients at risk for complications are likely to benefit from the simultaneous use of prophylactic agents with NSAID therapy. Risk factors for NSAID-related GI complications include: a previous GI event; older age; simultaneous use of anticoagulants, corticosteroids, or other NSAIDs (including low-dose aspirin); high-dose NSAID therapy; and chronic debilitating disorders (especially cardiovascular disease).6

Our patient improved with medical management

Our patient was evaluated by general surgery during his hospital admission, but because he was stable—with a healing duodenal perforation—we opted to manage him medically. We started him on esomeprazole (40 mg bid) along with ciprofloxacin (500 mg bid) and metronidazole (500 mg tid) for the microperforation of the duodenum. The patient was also scheduled for an outpatient endoscopic evaluation.

Six days after being discharged from the hospital for treatment of acute pericarditis, a 49-year-old man came to our clinic for a follow-up appointment. The patient still had midsternal chest discomfort and dyspnea. He also reported new epigastric abdominal pain, which had begun 2 days earlier. The patient’s wife indicated that he’d had a low-grade fever since discharge, but the patient denied any chills, hematemesis, melanotic stools, diarrhea, or constipation. The patient’s medical history was significant for gastroesophageal reflux, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, and obesity. Along with newly prescribed indomethacin for the pericarditis (50 mg tid), he was also taking simvastatin. In addition, he occasionally took ibuprofen (800 mg/d) for osteoarthritis of his knee.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Duodenal perforation caused by indomethacin

The CT scans revealed inflammation (arrows, FIGURE 1A) and thickening of the second and third portion of the duodenum and the pres- ence of extraluminal air at the site of the perforation (arrows, FIGURE 1B). There was also free fluid along the right paracolic gutter and into the pelvis. We diagnosed a small intestinal perforation in this patient, which was likely caused by a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer.

How NSAIDs affect the GI tract

NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX), the enzyme responsible for prostaglandin production. Specifically, the COX-1 enzyme is responsible for the production of prostaglandins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Prostaglandins play an important role in protecting the GI mucosa. By inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins, the permeability of the GI tract is increased and the natural protective barrier of the mucosa is destroyed.1

Gastroduodenal damage is a well-known adverse effect of NSAIDs. Ulcers have been noted on upper endoscopy in regular NSAID users, and the risk of developing a symptomatic ulcer and complications increases with every year of regular NSAID use.2 Ulcers in the GI tract can be complicated by perforation.1

Patients will complain of sudden onset abdominal pain

Important clues in the patient history for a perforated GI tract include sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that may present initially as epigastric pain and progress to generalized abdominal pain that may radiate to one or both shoulders.3 Physical exam findings for a perforated GI tract may include abdominal tenderness and rigid abdomen; fever and tachycardia may also be present.3 Concern for possible abdominal perforation should be evaluated with a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and radiographic studies.3

The differential diagnosis of epigastric abdominal pain includes: pancreatitis, gastritis, gastric/duodenal ulcer, and obstruction. Elevated serum lipase levels or CT findings of pancreatic inflammation assist in the diagnosis of pancreatitis. Upper endoscopy is key to identifying cases of gastritis and ulcers in the GI tract. And an abdominal radiograph that shows dilated loops of bowel will confirm suspicions of obstruction.

Stabilize the patientAcute management of GI perforation begins with stabilizing the patient and determining the need for surgical intervention or medical management. Should a patient have a persistent air leak, surgery is the mainstay of treatment.3 If the perforation has healed, the patient should be medically managed.

Therapy may require placing a nasogastric tube and holding any oral intake until abdominal pain and perforation resolves. Medications in the acute treatment should include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and antibiotics. Antibiotics should cover for gram-negative enteric bacteria and anaerobes.

How to prevent NSAID-induced injury.

PPIs used with nonselective NSAIDs appear to reduce the likelihood of gastric ulceration.4 Similarly, H2-receptor antagonists (H2RA) also inhibit gastric acid secretion, and high doses of them significantly reduce the incidence of gastric ulcers.4 However, standard doses of HRAs have not been shown to be effective in reducing the risk of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers.4 Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue that inhibits gastric secretion and protects the gastric mucosa is also an option; it has been used in combination with nonselective NSAIDs to counteract the increase in GI permeability.4

What about using COX-2 inhibitors instead? The COX-2 inhibitors have a lower risk of gastrointestinal tract injury.2 Gastric ulcers, GI bleeding, and complications from ulcers have been shown to be less common with COX-2 NSAIDs compared with nonselective NSAIDs.5 A review of the literature suggests that for patients with previous GI bleeding, COX-2 inhibitors are comparable to an NSAID paired with a PPI in preventing GI bleeding; pairing a COX-2 inhibitor with a PPI, however, appears to provide the greatest defense.2,4

Consider preventive steps. Patients at risk for complications are likely to benefit from the simultaneous use of prophylactic agents with NSAID therapy. Risk factors for NSAID-related GI complications include: a previous GI event; older age; simultaneous use of anticoagulants, corticosteroids, or other NSAIDs (including low-dose aspirin); high-dose NSAID therapy; and chronic debilitating disorders (especially cardiovascular disease).6

Our patient improved with medical management

Our patient was evaluated by general surgery during his hospital admission, but because he was stable—with a healing duodenal perforation—we opted to manage him medically. We started him on esomeprazole (40 mg bid) along with ciprofloxacin (500 mg bid) and metronidazole (500 mg tid) for the microperforation of the duodenum. The patient was also scheduled for an outpatient endoscopic evaluation.

1. Park SC, Chun HJ, Kang CD, et al. Prevention and management of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-induced small intestinal injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4647-4653.

2. Ng SC, Chan F. NSAID-induced gastrointestinal and car- diovascular injury. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26: 611-617.

3. Lawrence PF, Bell RM, TM, et al. Essentials of General Surgery. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. 4. Hooper, L, Brown TJ, Elliott R, et al. The effectiveness of five strategies for the prevention of gastrointestinal toxicity in-duced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329:948.

5. Rostom A, Muir K, Dube C, et al. Prevention of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a meta-analysis of traditional NSAIDs with gastroprotection and COX-2-inhibitors. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2009;1:47-71.

6. Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gatroenterology. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gas- troenterol. 2009;104:728-738.

1. Park SC, Chun HJ, Kang CD, et al. Prevention and management of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-induced small intestinal injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4647-4653.

2. Ng SC, Chan F. NSAID-induced gastrointestinal and car- diovascular injury. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26: 611-617.

3. Lawrence PF, Bell RM, TM, et al. Essentials of General Surgery. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. 4. Hooper, L, Brown TJ, Elliott R, et al. The effectiveness of five strategies for the prevention of gastrointestinal toxicity in-duced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329:948.

5. Rostom A, Muir K, Dube C, et al. Prevention of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a meta-analysis of traditional NSAIDs with gastroprotection and COX-2-inhibitors. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2009;1:47-71.

6. Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gatroenterology. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gas- troenterol. 2009;104:728-738.

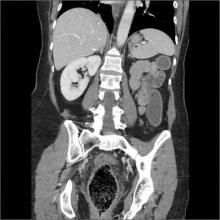

Obstipation

Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a proctophytobezoar. On follow-up questioning, the patient recalled consuming approximately 10 ounces of cooked quinoa, a nutritious, gluten-free, high-protein seed, just prior to the onset of her constipation.

A bezoar is a mass of poorly digested material that forms within the gastrointestinal tract—usually in the stomach—and less commonly in the small or large intestine. Trichobezoars (hair), lactobezoars (milk curd), phytobezoars (plant fiber), medication bezoars, and lithobezoars (small stones, pebbles, or gravel) are named after their contents.

Fecal impaction due to phytobezoars primarily composed of seeds has been associated with prickly pears, watermelons, sunflowers, pumpkins, pomegranates, and sesame seeds. This patient’s experience adds quinoa seeds to this list.

Treatment begins with a pharmacologic approach. When that fails, it’s time to perform a manual fragmentation and extraction of the fecal mass. Once fragmentation and partial expulsion has been achieved, one can then try a lubricating mineral oil enema, bisacodyl suppository, or rectal lavage. If the impaction extends beyond the reach of the fingers, sigmoidoscopic visualization and lavage are indicated.

Since conservative and comprehensive management to improve this patient’s condition failed, she was taken to the operating room for a proctosigmoidoscopic disimpaction. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on hospital Day 3.

Adapted from: Pelletier JF, Higgins GL, Haydar SA. Photo Rounds: Obstipation unresponsive to usual therapeutic maneuvers. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:353-355.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a proctophytobezoar. On follow-up questioning, the patient recalled consuming approximately 10 ounces of cooked quinoa, a nutritious, gluten-free, high-protein seed, just prior to the onset of her constipation.

A bezoar is a mass of poorly digested material that forms within the gastrointestinal tract—usually in the stomach—and less commonly in the small or large intestine. Trichobezoars (hair), lactobezoars (milk curd), phytobezoars (plant fiber), medication bezoars, and lithobezoars (small stones, pebbles, or gravel) are named after their contents.

Fecal impaction due to phytobezoars primarily composed of seeds has been associated with prickly pears, watermelons, sunflowers, pumpkins, pomegranates, and sesame seeds. This patient’s experience adds quinoa seeds to this list.

Treatment begins with a pharmacologic approach. When that fails, it’s time to perform a manual fragmentation and extraction of the fecal mass. Once fragmentation and partial expulsion has been achieved, one can then try a lubricating mineral oil enema, bisacodyl suppository, or rectal lavage. If the impaction extends beyond the reach of the fingers, sigmoidoscopic visualization and lavage are indicated.

Since conservative and comprehensive management to improve this patient’s condition failed, she was taken to the operating room for a proctosigmoidoscopic disimpaction. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on hospital Day 3.

Adapted from: Pelletier JF, Higgins GL, Haydar SA. Photo Rounds: Obstipation unresponsive to usual therapeutic maneuvers. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:353-355.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a proctophytobezoar. On follow-up questioning, the patient recalled consuming approximately 10 ounces of cooked quinoa, a nutritious, gluten-free, high-protein seed, just prior to the onset of her constipation.

A bezoar is a mass of poorly digested material that forms within the gastrointestinal tract—usually in the stomach—and less commonly in the small or large intestine. Trichobezoars (hair), lactobezoars (milk curd), phytobezoars (plant fiber), medication bezoars, and lithobezoars (small stones, pebbles, or gravel) are named after their contents.

Fecal impaction due to phytobezoars primarily composed of seeds has been associated with prickly pears, watermelons, sunflowers, pumpkins, pomegranates, and sesame seeds. This patient’s experience adds quinoa seeds to this list.

Treatment begins with a pharmacologic approach. When that fails, it’s time to perform a manual fragmentation and extraction of the fecal mass. Once fragmentation and partial expulsion has been achieved, one can then try a lubricating mineral oil enema, bisacodyl suppository, or rectal lavage. If the impaction extends beyond the reach of the fingers, sigmoidoscopic visualization and lavage are indicated.

Since conservative and comprehensive management to improve this patient’s condition failed, she was taken to the operating room for a proctosigmoidoscopic disimpaction. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on hospital Day 3.

Adapted from: Pelletier JF, Higgins GL, Haydar SA. Photo Rounds: Obstipation unresponsive to usual therapeutic maneuvers. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:353-355.

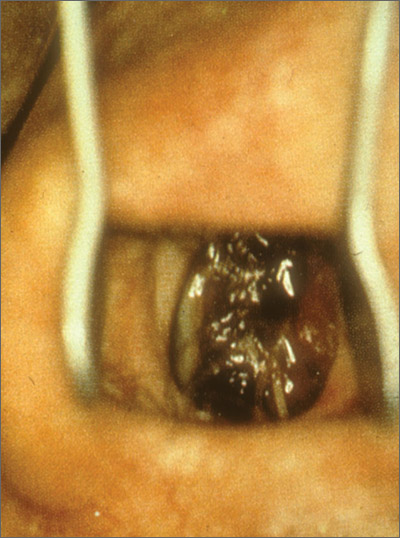

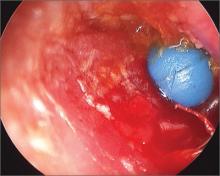

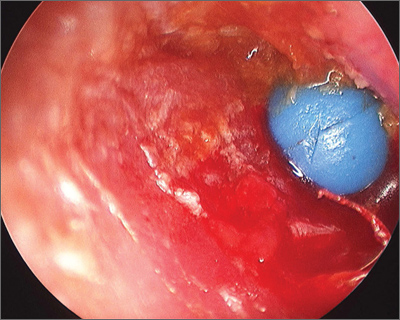

Object in ear

The parents told the family physician that their child had been playing with a toy beaded necklace when she started crying. The patient was referred to an otolaryngologist, who removed the bead using an operating microscope for visualization. She evaluated the child for a co-existing otitis externa and decided that the external canal was markedly inflamed and probably infected. The otolaryngologist prescribed Corticosporin Otic Suspension to treat the inflammation and infection. This preparation includes a topical steroid along with topical antibiotics. The child did well on the medication.

Ear foreign bodies (FBs) are commonly seen in children ages 1 to 6 years. The most common FBs in children include beads, cotton tips, paper, toy parts, crayons, eraser tips, food, or organic matter (eg, sand, sticks, stones). Ear irrigation may be attempted in the office if the object is not a battery or vegetable matter, and there is no evidence of a perforated tympanic membrane.

Referral to otolaryngology should be considered when:

- More than one attempt to remove the object has been carried out without success.

- Patients have firm rounded FBs (as was the case with this patient).

- Patients have FBs with smooth, non-graspable surfaces (also the case with this patient).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala, B. Ear: foreign body. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:185-188.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The parents told the family physician that their child had been playing with a toy beaded necklace when she started crying. The patient was referred to an otolaryngologist, who removed the bead using an operating microscope for visualization. She evaluated the child for a co-existing otitis externa and decided that the external canal was markedly inflamed and probably infected. The otolaryngologist prescribed Corticosporin Otic Suspension to treat the inflammation and infection. This preparation includes a topical steroid along with topical antibiotics. The child did well on the medication.

Ear foreign bodies (FBs) are commonly seen in children ages 1 to 6 years. The most common FBs in children include beads, cotton tips, paper, toy parts, crayons, eraser tips, food, or organic matter (eg, sand, sticks, stones). Ear irrigation may be attempted in the office if the object is not a battery or vegetable matter, and there is no evidence of a perforated tympanic membrane.

Referral to otolaryngology should be considered when:

- More than one attempt to remove the object has been carried out without success.

- Patients have firm rounded FBs (as was the case with this patient).

- Patients have FBs with smooth, non-graspable surfaces (also the case with this patient).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala, B. Ear: foreign body. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:185-188.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The parents told the family physician that their child had been playing with a toy beaded necklace when she started crying. The patient was referred to an otolaryngologist, who removed the bead using an operating microscope for visualization. She evaluated the child for a co-existing otitis externa and decided that the external canal was markedly inflamed and probably infected. The otolaryngologist prescribed Corticosporin Otic Suspension to treat the inflammation and infection. This preparation includes a topical steroid along with topical antibiotics. The child did well on the medication.

Ear foreign bodies (FBs) are commonly seen in children ages 1 to 6 years. The most common FBs in children include beads, cotton tips, paper, toy parts, crayons, eraser tips, food, or organic matter (eg, sand, sticks, stones). Ear irrigation may be attempted in the office if the object is not a battery or vegetable matter, and there is no evidence of a perforated tympanic membrane.

Referral to otolaryngology should be considered when:

- More than one attempt to remove the object has been carried out without success.

- Patients have firm rounded FBs (as was the case with this patient).

- Patients have FBs with smooth, non-graspable surfaces (also the case with this patient).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rayala, B. Ear: foreign body. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:185-188.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/