User login

Hoarseness and chronic cough

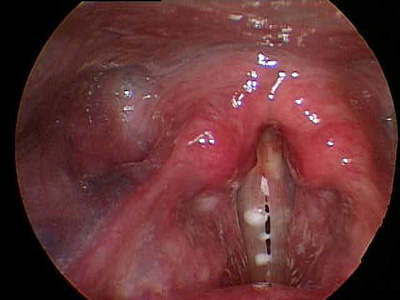

The FP diagnosed laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) based on the edema and visible mucus. The vocal cords showed no masses or lesions.

LPR symptoms include hoarseness, throat clearing, “postnasal drip,” chronic cough, dysphagia, globus pharyngeus, and sore throat. LPR must be differentiated from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), in which acid reflux is more likely to cause heartburn, indigestion, and regurgitation and does not necessarily reach the larynx or upper aerodigestive tract.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid acidic and greasy foods, limit alcohol and caffeine, consider losing some weight, and avoid meals shortly before lying down. Medical therapy consisted of twice daily proton pump inhibitors 30 to 60 minutes before meals, which can often be weaned after several months of therapy. Some patients benefit from adding an H2 blocker, such as ranitidine 300 mg, at bedtime.

Photos courtesy of Blake Simpson, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Matrka L, Simpson CB, King JM. The larynx (hoarseness). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:220-226.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) based on the edema and visible mucus. The vocal cords showed no masses or lesions.

LPR symptoms include hoarseness, throat clearing, “postnasal drip,” chronic cough, dysphagia, globus pharyngeus, and sore throat. LPR must be differentiated from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), in which acid reflux is more likely to cause heartburn, indigestion, and regurgitation and does not necessarily reach the larynx or upper aerodigestive tract.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid acidic and greasy foods, limit alcohol and caffeine, consider losing some weight, and avoid meals shortly before lying down. Medical therapy consisted of twice daily proton pump inhibitors 30 to 60 minutes before meals, which can often be weaned after several months of therapy. Some patients benefit from adding an H2 blocker, such as ranitidine 300 mg, at bedtime.

Photos courtesy of Blake Simpson, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Matrka L, Simpson CB, King JM. The larynx (hoarseness). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:220-226.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) based on the edema and visible mucus. The vocal cords showed no masses or lesions.

LPR symptoms include hoarseness, throat clearing, “postnasal drip,” chronic cough, dysphagia, globus pharyngeus, and sore throat. LPR must be differentiated from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), in which acid reflux is more likely to cause heartburn, indigestion, and regurgitation and does not necessarily reach the larynx or upper aerodigestive tract.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid acidic and greasy foods, limit alcohol and caffeine, consider losing some weight, and avoid meals shortly before lying down. Medical therapy consisted of twice daily proton pump inhibitors 30 to 60 minutes before meals, which can often be weaned after several months of therapy. Some patients benefit from adding an H2 blocker, such as ranitidine 300 mg, at bedtime.

Photos courtesy of Blake Simpson, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Matrka L, Simpson CB, King JM. The larynx (hoarseness). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:220-226.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Purpuric lesions in an elderly woman

A 68-year-old woman presented with a 5-day history of extensive pruritic purpuric skin lesions of varying sizes on her trunk and extremities (FIGURE 1A and 1B). In addition, the patient had a few nonblanching, erythematous macules on her extremities.

The patient had no neurological complaints and her family history was negative for a similar condition. We performed a punch biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Churg-Strauss syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS)—also known as allergic granulomatosis and angiitis—is a rare multisystemic vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels characterized by asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia.1,2 Mean diagnosis age is 50 years with no gender predilection.2 Any organ system can be affected, although the lungs are most commonly involved, followed by the skin.1,2

Based on criteria from the American College of Rheumatology, the diagnosis of CSS can be made if 4 of the following 6 criteria are met: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia >10% on a differential white blood cell (WBC) count, (3) paranasal sinus abnormalities, (4) a transient pulmonary infiltrate detected on chest x-ray, (5) mono- or polyneuropathy, and (6) a biopsy specimen showing extravascular accumulation of eosinophils.2

Skin biopsy specimen from our patient showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with prominent tissue eosinophilia. Laboratory studies showed an elevated WBC count of 12,300/mcL (reference range, 4500-11,000/mcL), and eosinophilia of 40% (reference range, 1%-4%). A serologic test for perinuclear pattern antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) was positive. (More on this in a moment.) Radiography of the chest showed transient pulmonary infiltrates.

Based on the clinical and laboratory findings, the patient was positive for 4 of 6 criteria and given a diagnosis of CSS.

What we know—and don’t know—about CSS

The exact etiopathogenesis of CSS is unknown.2-4 Although ANCAs are detected in about 40% to 60% of CSS patients, it is not yet known whether ANCAs have a pathogenic role.2-3 Abnormalities in immunologic function also occur, including heightened Th1 and Th2 lymphocyte function, increased recruitment of eosinophils, and decreased eosinophil apoptosis. Genetic factors, including certain interleukin-10 polymorphisms and HLA classes such as HLA-DRB4, may also contribute to CSS pathogenesis.4

Three distinct sequential phases have been described, although these are not always clearly distinguishable.2,5

• The first is the prodromal or allergic phase, which is characterized by the onset of asthma later in life in patients with no family history of atopy. There may or may not be an associated allergic rhinitis.

• In the eosinophilic phase, peripheral blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs (especially the lungs and gastrointestinal [GI] tract) occur.

• The vasculitis phase is characterized by life-threatening systemic vasculitis of the small and medium vessels that is often associated with vascular and extravascular granulomatosis.

Cutaneous and extracutaneous findings

One-half to two-thirds of patients with CSS have cutaneous manifestations that typically present in the vasculitis phase.2,5 The most common skin finding is palpable purpura on the lower extremities. Macular or papular erythematous eruption, urticaria, subcutaneous skin-colored or erythematous nodules, livedo reticularis, and erythema multiforme–like eruption may also be seen.2,5,6 Skin biopsies will show numerous eosinophils with either leukocytoclastic vasculitis or extravascular necrotizing granuloma.5

Extracutaneous manifestations of CSS include renal, cardiac, GI tract, and nervous system involvement.2,7

To identify patients with a poor prognosis, the 5-factor score (FFS) can be used. This score assigns 1 point each to GI tract involvement, renal insufficiency, proteinuria, central nervous system involvement, and cardiomyopathy.7 CSS patients with an FFS ≥2 have a considerably greater risk of mortality.7

Treatment involves corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day) are the primary treatment for patients with CSS; most patients improve dramatically with therapy.2 Adjunctive therapy with immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate (10-15 mg per week), chlorambucil, or azathioprine may be needed if a patient does not respond adequately to steroids alone.2

Prednisone for our patient

We started our patient on prednisone 1 mg/kg/d. Her skin lesions resolved and subsequent laboratory tests, including eosinophil counts, normalized. Prednisone therapy was gradually tapered over several months to attain the lowest dose required for control of symptoms—in this case, 5 mg/d.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ossama Abbas, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Dermatology, American University of Beirut Medical Center, PO Box 11-0236, Riad El Solh, Beirut 1107 2020, Beirut, Lebanon; [email protected]

1. Churg J, Strauss L. Allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Pathol. 1951;27:277-301.

2. Sinico RA, Bottero P. Churg-Strauss angiitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:355-366.

3. Zwerina J, Axmann R, Jatzwauk M, et al. Pathogenesis of Churg-Strauss syndrome: recent insights. Autoimmunity. 2009;42:376-379.

4. Vaglio A, Martorana D, Maggiore U, et al; Secondary and Primary Vasculitis Study Group. HLA-DRB4 as a genetic risk factor for Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3159-3166.

5. Davis MD, Daoud MS, McEvoy MT, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome: a clinicopathologic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 pt 1):199-203.

6. Tlacuilo-Parra A, Soto-Ortíz JA, Guevara-Gutiérrez E. Churg-Strauss syndrome manifested by urticarial plaques. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:386-388.

7. Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, et al. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:17-28.

A 68-year-old woman presented with a 5-day history of extensive pruritic purpuric skin lesions of varying sizes on her trunk and extremities (FIGURE 1A and 1B). In addition, the patient had a few nonblanching, erythematous macules on her extremities.

The patient had no neurological complaints and her family history was negative for a similar condition. We performed a punch biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Churg-Strauss syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS)—also known as allergic granulomatosis and angiitis—is a rare multisystemic vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels characterized by asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia.1,2 Mean diagnosis age is 50 years with no gender predilection.2 Any organ system can be affected, although the lungs are most commonly involved, followed by the skin.1,2

Based on criteria from the American College of Rheumatology, the diagnosis of CSS can be made if 4 of the following 6 criteria are met: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia >10% on a differential white blood cell (WBC) count, (3) paranasal sinus abnormalities, (4) a transient pulmonary infiltrate detected on chest x-ray, (5) mono- or polyneuropathy, and (6) a biopsy specimen showing extravascular accumulation of eosinophils.2

Skin biopsy specimen from our patient showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with prominent tissue eosinophilia. Laboratory studies showed an elevated WBC count of 12,300/mcL (reference range, 4500-11,000/mcL), and eosinophilia of 40% (reference range, 1%-4%). A serologic test for perinuclear pattern antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) was positive. (More on this in a moment.) Radiography of the chest showed transient pulmonary infiltrates.

Based on the clinical and laboratory findings, the patient was positive for 4 of 6 criteria and given a diagnosis of CSS.

What we know—and don’t know—about CSS

The exact etiopathogenesis of CSS is unknown.2-4 Although ANCAs are detected in about 40% to 60% of CSS patients, it is not yet known whether ANCAs have a pathogenic role.2-3 Abnormalities in immunologic function also occur, including heightened Th1 and Th2 lymphocyte function, increased recruitment of eosinophils, and decreased eosinophil apoptosis. Genetic factors, including certain interleukin-10 polymorphisms and HLA classes such as HLA-DRB4, may also contribute to CSS pathogenesis.4

Three distinct sequential phases have been described, although these are not always clearly distinguishable.2,5

• The first is the prodromal or allergic phase, which is characterized by the onset of asthma later in life in patients with no family history of atopy. There may or may not be an associated allergic rhinitis.

• In the eosinophilic phase, peripheral blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs (especially the lungs and gastrointestinal [GI] tract) occur.

• The vasculitis phase is characterized by life-threatening systemic vasculitis of the small and medium vessels that is often associated with vascular and extravascular granulomatosis.

Cutaneous and extracutaneous findings

One-half to two-thirds of patients with CSS have cutaneous manifestations that typically present in the vasculitis phase.2,5 The most common skin finding is palpable purpura on the lower extremities. Macular or papular erythematous eruption, urticaria, subcutaneous skin-colored or erythematous nodules, livedo reticularis, and erythema multiforme–like eruption may also be seen.2,5,6 Skin biopsies will show numerous eosinophils with either leukocytoclastic vasculitis or extravascular necrotizing granuloma.5

Extracutaneous manifestations of CSS include renal, cardiac, GI tract, and nervous system involvement.2,7

To identify patients with a poor prognosis, the 5-factor score (FFS) can be used. This score assigns 1 point each to GI tract involvement, renal insufficiency, proteinuria, central nervous system involvement, and cardiomyopathy.7 CSS patients with an FFS ≥2 have a considerably greater risk of mortality.7

Treatment involves corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day) are the primary treatment for patients with CSS; most patients improve dramatically with therapy.2 Adjunctive therapy with immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate (10-15 mg per week), chlorambucil, or azathioprine may be needed if a patient does not respond adequately to steroids alone.2

Prednisone for our patient

We started our patient on prednisone 1 mg/kg/d. Her skin lesions resolved and subsequent laboratory tests, including eosinophil counts, normalized. Prednisone therapy was gradually tapered over several months to attain the lowest dose required for control of symptoms—in this case, 5 mg/d.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ossama Abbas, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Dermatology, American University of Beirut Medical Center, PO Box 11-0236, Riad El Solh, Beirut 1107 2020, Beirut, Lebanon; [email protected]

A 68-year-old woman presented with a 5-day history of extensive pruritic purpuric skin lesions of varying sizes on her trunk and extremities (FIGURE 1A and 1B). In addition, the patient had a few nonblanching, erythematous macules on her extremities.

The patient had no neurological complaints and her family history was negative for a similar condition. We performed a punch biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Churg-Strauss syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS)—also known as allergic granulomatosis and angiitis—is a rare multisystemic vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels characterized by asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia.1,2 Mean diagnosis age is 50 years with no gender predilection.2 Any organ system can be affected, although the lungs are most commonly involved, followed by the skin.1,2

Based on criteria from the American College of Rheumatology, the diagnosis of CSS can be made if 4 of the following 6 criteria are met: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia >10% on a differential white blood cell (WBC) count, (3) paranasal sinus abnormalities, (4) a transient pulmonary infiltrate detected on chest x-ray, (5) mono- or polyneuropathy, and (6) a biopsy specimen showing extravascular accumulation of eosinophils.2

Skin biopsy specimen from our patient showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with prominent tissue eosinophilia. Laboratory studies showed an elevated WBC count of 12,300/mcL (reference range, 4500-11,000/mcL), and eosinophilia of 40% (reference range, 1%-4%). A serologic test for perinuclear pattern antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) was positive. (More on this in a moment.) Radiography of the chest showed transient pulmonary infiltrates.

Based on the clinical and laboratory findings, the patient was positive for 4 of 6 criteria and given a diagnosis of CSS.

What we know—and don’t know—about CSS

The exact etiopathogenesis of CSS is unknown.2-4 Although ANCAs are detected in about 40% to 60% of CSS patients, it is not yet known whether ANCAs have a pathogenic role.2-3 Abnormalities in immunologic function also occur, including heightened Th1 and Th2 lymphocyte function, increased recruitment of eosinophils, and decreased eosinophil apoptosis. Genetic factors, including certain interleukin-10 polymorphisms and HLA classes such as HLA-DRB4, may also contribute to CSS pathogenesis.4

Three distinct sequential phases have been described, although these are not always clearly distinguishable.2,5

• The first is the prodromal or allergic phase, which is characterized by the onset of asthma later in life in patients with no family history of atopy. There may or may not be an associated allergic rhinitis.

• In the eosinophilic phase, peripheral blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs (especially the lungs and gastrointestinal [GI] tract) occur.

• The vasculitis phase is characterized by life-threatening systemic vasculitis of the small and medium vessels that is often associated with vascular and extravascular granulomatosis.

Cutaneous and extracutaneous findings

One-half to two-thirds of patients with CSS have cutaneous manifestations that typically present in the vasculitis phase.2,5 The most common skin finding is palpable purpura on the lower extremities. Macular or papular erythematous eruption, urticaria, subcutaneous skin-colored or erythematous nodules, livedo reticularis, and erythema multiforme–like eruption may also be seen.2,5,6 Skin biopsies will show numerous eosinophils with either leukocytoclastic vasculitis or extravascular necrotizing granuloma.5

Extracutaneous manifestations of CSS include renal, cardiac, GI tract, and nervous system involvement.2,7

To identify patients with a poor prognosis, the 5-factor score (FFS) can be used. This score assigns 1 point each to GI tract involvement, renal insufficiency, proteinuria, central nervous system involvement, and cardiomyopathy.7 CSS patients with an FFS ≥2 have a considerably greater risk of mortality.7

Treatment involves corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day) are the primary treatment for patients with CSS; most patients improve dramatically with therapy.2 Adjunctive therapy with immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate (10-15 mg per week), chlorambucil, or azathioprine may be needed if a patient does not respond adequately to steroids alone.2

Prednisone for our patient

We started our patient on prednisone 1 mg/kg/d. Her skin lesions resolved and subsequent laboratory tests, including eosinophil counts, normalized. Prednisone therapy was gradually tapered over several months to attain the lowest dose required for control of symptoms—in this case, 5 mg/d.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ossama Abbas, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Dermatology, American University of Beirut Medical Center, PO Box 11-0236, Riad El Solh, Beirut 1107 2020, Beirut, Lebanon; [email protected]

1. Churg J, Strauss L. Allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Pathol. 1951;27:277-301.

2. Sinico RA, Bottero P. Churg-Strauss angiitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:355-366.

3. Zwerina J, Axmann R, Jatzwauk M, et al. Pathogenesis of Churg-Strauss syndrome: recent insights. Autoimmunity. 2009;42:376-379.

4. Vaglio A, Martorana D, Maggiore U, et al; Secondary and Primary Vasculitis Study Group. HLA-DRB4 as a genetic risk factor for Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3159-3166.

5. Davis MD, Daoud MS, McEvoy MT, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome: a clinicopathologic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 pt 1):199-203.

6. Tlacuilo-Parra A, Soto-Ortíz JA, Guevara-Gutiérrez E. Churg-Strauss syndrome manifested by urticarial plaques. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:386-388.

7. Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, et al. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:17-28.

1. Churg J, Strauss L. Allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Pathol. 1951;27:277-301.

2. Sinico RA, Bottero P. Churg-Strauss angiitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:355-366.

3. Zwerina J, Axmann R, Jatzwauk M, et al. Pathogenesis of Churg-Strauss syndrome: recent insights. Autoimmunity. 2009;42:376-379.

4. Vaglio A, Martorana D, Maggiore U, et al; Secondary and Primary Vasculitis Study Group. HLA-DRB4 as a genetic risk factor for Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3159-3166.

5. Davis MD, Daoud MS, McEvoy MT, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome: a clinicopathologic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 pt 1):199-203.

6. Tlacuilo-Parra A, Soto-Ortíz JA, Guevara-Gutiérrez E. Churg-Strauss syndrome manifested by urticarial plaques. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:386-388.

7. Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, et al. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:17-28.

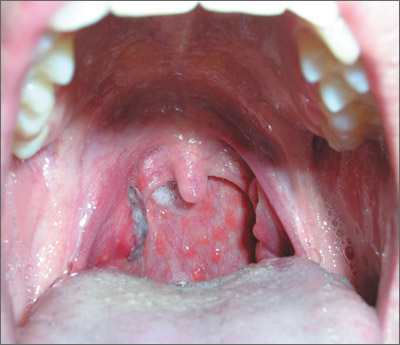

Dark area on tonsil

The family physician (FP) suspected strep pharyngitis, but decided to order a rapid strep test to confirm this impression. The test was positive.

The FP explained that the dark area on the tonsil was secondary to infection and would resolve over time. He also told the patient that the cobblestone pattern on the posterior pharynx may have been secondary to a history of allergic rhinitis or could have been newly acquired as part of the strep pharyngitis.

Posterior lymphoid hyperplasia is not a specific finding, even though it is commonly seen in allergic rhinitis and viral pharyngitis. Note, too, that patients may have strep pharyngitis even without tonsillar exudate.

In this case, the patient was given a course of penicillin VK for 10 days. The physician recommended oral analgesics/antipyretics as needed, plenty of fluids, and rest.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The family physician (FP) suspected strep pharyngitis, but decided to order a rapid strep test to confirm this impression. The test was positive.

The FP explained that the dark area on the tonsil was secondary to infection and would resolve over time. He also told the patient that the cobblestone pattern on the posterior pharynx may have been secondary to a history of allergic rhinitis or could have been newly acquired as part of the strep pharyngitis.

Posterior lymphoid hyperplasia is not a specific finding, even though it is commonly seen in allergic rhinitis and viral pharyngitis. Note, too, that patients may have strep pharyngitis even without tonsillar exudate.

In this case, the patient was given a course of penicillin VK for 10 days. The physician recommended oral analgesics/antipyretics as needed, plenty of fluids, and rest.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The family physician (FP) suspected strep pharyngitis, but decided to order a rapid strep test to confirm this impression. The test was positive.

The FP explained that the dark area on the tonsil was secondary to infection and would resolve over time. He also told the patient that the cobblestone pattern on the posterior pharynx may have been secondary to a history of allergic rhinitis or could have been newly acquired as part of the strep pharyngitis.

Posterior lymphoid hyperplasia is not a specific finding, even though it is commonly seen in allergic rhinitis and viral pharyngitis. Note, too, that patients may have strep pharyngitis even without tonsillar exudate.

In this case, the patient was given a course of penicillin VK for 10 days. The physician recommended oral analgesics/antipyretics as needed, plenty of fluids, and rest.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Throat and neck pain

The FP suspected that the patient had infectious mononucleosis caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. She performed an abdominal exam, but there was no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly. Other features of mononucleosis may include nausea, anorexia without vomiting, uvular edema, generalized symmetric lymphadenopathy, and lethargy.

The FP recommended supportive measures including ibuprofen and/or acetaminophen for pain and fever, plenty of fluids, and rest. The patient was sent to the lab for a Monospot test, and the result came back positive the following day. At that point, the FP also recommended avoidance of contact sports for the next few months because of the risk of splenic rupture associated with mononucleosis. At a follow-up appointment a week later, the patient was doing somewhat better but continued to have some fatigue, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy. Fortunately, this was the start of summer vacation for the student, so she was able to take time off to recuperate.

Photo courtesy of Tracey Cawthorn, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP suspected that the patient had infectious mononucleosis caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. She performed an abdominal exam, but there was no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly. Other features of mononucleosis may include nausea, anorexia without vomiting, uvular edema, generalized symmetric lymphadenopathy, and lethargy.

The FP recommended supportive measures including ibuprofen and/or acetaminophen for pain and fever, plenty of fluids, and rest. The patient was sent to the lab for a Monospot test, and the result came back positive the following day. At that point, the FP also recommended avoidance of contact sports for the next few months because of the risk of splenic rupture associated with mononucleosis. At a follow-up appointment a week later, the patient was doing somewhat better but continued to have some fatigue, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy. Fortunately, this was the start of summer vacation for the student, so she was able to take time off to recuperate.

Photo courtesy of Tracey Cawthorn, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP suspected that the patient had infectious mononucleosis caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. She performed an abdominal exam, but there was no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly. Other features of mononucleosis may include nausea, anorexia without vomiting, uvular edema, generalized symmetric lymphadenopathy, and lethargy.

The FP recommended supportive measures including ibuprofen and/or acetaminophen for pain and fever, plenty of fluids, and rest. The patient was sent to the lab for a Monospot test, and the result came back positive the following day. At that point, the FP also recommended avoidance of contact sports for the next few months because of the risk of splenic rupture associated with mononucleosis. At a follow-up appointment a week later, the patient was doing somewhat better but continued to have some fatigue, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy. Fortunately, this was the start of summer vacation for the student, so she was able to take time off to recuperate.

Photo courtesy of Tracey Cawthorn, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Throat pain and red spots on palate

The absence of fever, tonsillar swelling and exudate, and anterior cervical adenopathy and the presence of rhinorrhea and cough all pointed to a viral upper respiratory infection. The red spots were palatal petechiae, which are seen in all types of pharyngitis and are benign.

Testing for strep pharyngitis is unnecessary. Treatment is directed at the symptoms only.

The treatment for most cases of non-group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) pharyngitis includes education. Explain to patients the difference between a viral and a bacterial infection to help them understand why antibiotics are not being prescribed.

Studies have demonstrated that spending time with patients to explain the disease process is associated with greater patient satisfaction than prescribing an antibiotic. Fortunately, this patient was not seeking antibiotics and was happy to hear that the viral infection was self-limited. The family physician recommended analgesics as needed, plenty of fluids, and moderate rest.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The absence of fever, tonsillar swelling and exudate, and anterior cervical adenopathy and the presence of rhinorrhea and cough all pointed to a viral upper respiratory infection. The red spots were palatal petechiae, which are seen in all types of pharyngitis and are benign.

Testing for strep pharyngitis is unnecessary. Treatment is directed at the symptoms only.

The treatment for most cases of non-group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) pharyngitis includes education. Explain to patients the difference between a viral and a bacterial infection to help them understand why antibiotics are not being prescribed.

Studies have demonstrated that spending time with patients to explain the disease process is associated with greater patient satisfaction than prescribing an antibiotic. Fortunately, this patient was not seeking antibiotics and was happy to hear that the viral infection was self-limited. The family physician recommended analgesics as needed, plenty of fluids, and moderate rest.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The absence of fever, tonsillar swelling and exudate, and anterior cervical adenopathy and the presence of rhinorrhea and cough all pointed to a viral upper respiratory infection. The red spots were palatal petechiae, which are seen in all types of pharyngitis and are benign.

Testing for strep pharyngitis is unnecessary. Treatment is directed at the symptoms only.

The treatment for most cases of non-group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) pharyngitis includes education. Explain to patients the difference between a viral and a bacterial infection to help them understand why antibiotics are not being prescribed.

Studies have demonstrated that spending time with patients to explain the disease process is associated with greater patient satisfaction than prescribing an antibiotic. Fortunately, this patient was not seeking antibiotics and was happy to hear that the viral infection was self-limited. The family physician recommended analgesics as needed, plenty of fluids, and moderate rest.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Severe throat pain

Based on the presence of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, and tonsillar exudate—and the absence of cough—the physician strongly suspected group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) pharyngitis and prescribed oral penicillin VK. GABHS accounts for 5% to 10% of pharyngitis in adults and 15% to 30% in children. Up to 38% of cases of tonsillitis are because of GABHS.

The following criteria are helpful in the diagnosis of GABHS pharyngitis:

○ history of fever or temperature of 38°C (100.4°F) (1 point)

○ absence of cough (1 point)

○ tender anterior cervical lymph nodes (1 point)

○ tonsillar swelling or exudates (1 point)

○ age: <15 years (1 point); 15 to 45 years (0 points); >45 years (–1 point).

The probability of GABHS is approximately 1% with –1 to 0 points and approximately 51% with 4 to 5 points.

Rapid antigen detection is often used to diagnose GABHS. Test options include enzyme immunoassays, latex agglutination, liposomal method, and immunochromatographic assays. The immunochromatographic assay has the highest reported sensitivity (97%), specificity (97%), and positive (32.3) and negative (0.03) likelihood ratios.

In this patient’s case, the likelihood of strep pharyngitis was high enough that a rapid strep test was not performed. For suspected or proven GABHS, penicillin VK 500 mg orally 2 to 3 times daily for 10 days continues to be the treatment of choice for adults. Erythromycin 500 mg orally 4 times daily may be used in penicillin allergic patients. Treatment should also include analgesics/antipyretics, as needed, plenty of fluids, and rest.

Photo courtesy of Michael Nguyen, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Based on the presence of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, and tonsillar exudate—and the absence of cough—the physician strongly suspected group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) pharyngitis and prescribed oral penicillin VK. GABHS accounts for 5% to 10% of pharyngitis in adults and 15% to 30% in children. Up to 38% of cases of tonsillitis are because of GABHS.

The following criteria are helpful in the diagnosis of GABHS pharyngitis:

○ history of fever or temperature of 38°C (100.4°F) (1 point)

○ absence of cough (1 point)

○ tender anterior cervical lymph nodes (1 point)

○ tonsillar swelling or exudates (1 point)

○ age: <15 years (1 point); 15 to 45 years (0 points); >45 years (–1 point).

The probability of GABHS is approximately 1% with –1 to 0 points and approximately 51% with 4 to 5 points.

Rapid antigen detection is often used to diagnose GABHS. Test options include enzyme immunoassays, latex agglutination, liposomal method, and immunochromatographic assays. The immunochromatographic assay has the highest reported sensitivity (97%), specificity (97%), and positive (32.3) and negative (0.03) likelihood ratios.

In this patient’s case, the likelihood of strep pharyngitis was high enough that a rapid strep test was not performed. For suspected or proven GABHS, penicillin VK 500 mg orally 2 to 3 times daily for 10 days continues to be the treatment of choice for adults. Erythromycin 500 mg orally 4 times daily may be used in penicillin allergic patients. Treatment should also include analgesics/antipyretics, as needed, plenty of fluids, and rest.

Photo courtesy of Michael Nguyen, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Based on the presence of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, and tonsillar exudate—and the absence of cough—the physician strongly suspected group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) pharyngitis and prescribed oral penicillin VK. GABHS accounts for 5% to 10% of pharyngitis in adults and 15% to 30% in children. Up to 38% of cases of tonsillitis are because of GABHS.

The following criteria are helpful in the diagnosis of GABHS pharyngitis:

○ history of fever or temperature of 38°C (100.4°F) (1 point)

○ absence of cough (1 point)

○ tender anterior cervical lymph nodes (1 point)

○ tonsillar swelling or exudates (1 point)

○ age: <15 years (1 point); 15 to 45 years (0 points); >45 years (–1 point).

The probability of GABHS is approximately 1% with –1 to 0 points and approximately 51% with 4 to 5 points.

Rapid antigen detection is often used to diagnose GABHS. Test options include enzyme immunoassays, latex agglutination, liposomal method, and immunochromatographic assays. The immunochromatographic assay has the highest reported sensitivity (97%), specificity (97%), and positive (32.3) and negative (0.03) likelihood ratios.

In this patient’s case, the likelihood of strep pharyngitis was high enough that a rapid strep test was not performed. For suspected or proven GABHS, penicillin VK 500 mg orally 2 to 3 times daily for 10 days continues to be the treatment of choice for adults. Erythromycin 500 mg orally 4 times daily may be used in penicillin allergic patients. Treatment should also include analgesics/antipyretics, as needed, plenty of fluids, and rest.

Photo courtesy of Michael Nguyen, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Williams, B, Usatine R, Smith M. Pharyngitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:213-219.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Painful toes

Upon closer inspection, the physicians discovered hair thread tourniquets constricting the fourth and fifth toes on the baby’s left foot.

Hair tourniquet syndrome primarily affects infants in the first few months of life. The average age of occurrence is 4 months, a time when maternal postpartum hair loss is at its maximum.

Toes are most frequently involved, although cases of hair tourniquets affecting the fingers, penis, labia, clitoris, and uvula have been reported.

To remove this patient’s hair tourniquets, the physician carefully cut the fibers with hooked Littauer suture-removal scissors and unwrapped the hair. Damage to the plantar aspect of both toes was significant enough that the physician had to cut through the soft tissue and into the flexor tendon to completely remove the hair. No sutures were required, as the wound edges were well approximated without closure.

The injured toes were cleaned and dressed. The patient’s recovery was complete and uneventful.

Adapted from: Moore EP, Strout TD, Saucier JR. Photo Rounds: Crying infant with painful toes. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:675-677.

Upon closer inspection, the physicians discovered hair thread tourniquets constricting the fourth and fifth toes on the baby’s left foot.

Hair tourniquet syndrome primarily affects infants in the first few months of life. The average age of occurrence is 4 months, a time when maternal postpartum hair loss is at its maximum.

Toes are most frequently involved, although cases of hair tourniquets affecting the fingers, penis, labia, clitoris, and uvula have been reported.

To remove this patient’s hair tourniquets, the physician carefully cut the fibers with hooked Littauer suture-removal scissors and unwrapped the hair. Damage to the plantar aspect of both toes was significant enough that the physician had to cut through the soft tissue and into the flexor tendon to completely remove the hair. No sutures were required, as the wound edges were well approximated without closure.

The injured toes were cleaned and dressed. The patient’s recovery was complete and uneventful.

Adapted from: Moore EP, Strout TD, Saucier JR. Photo Rounds: Crying infant with painful toes. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:675-677.

Upon closer inspection, the physicians discovered hair thread tourniquets constricting the fourth and fifth toes on the baby’s left foot.

Hair tourniquet syndrome primarily affects infants in the first few months of life. The average age of occurrence is 4 months, a time when maternal postpartum hair loss is at its maximum.

Toes are most frequently involved, although cases of hair tourniquets affecting the fingers, penis, labia, clitoris, and uvula have been reported.

To remove this patient’s hair tourniquets, the physician carefully cut the fibers with hooked Littauer suture-removal scissors and unwrapped the hair. Damage to the plantar aspect of both toes was significant enough that the physician had to cut through the soft tissue and into the flexor tendon to completely remove the hair. No sutures were required, as the wound edges were well approximated without closure.

The injured toes were cleaned and dressed. The patient’s recovery was complete and uneventful.

Adapted from: Moore EP, Strout TD, Saucier JR. Photo Rounds: Crying infant with painful toes. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:675-677.

Mucocutaneous ulceration in a previously healthy man

A 36-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our facility for rapidly progressive painful ulcers that were affecting his throat, tongue, genital area, and other parts of his body. He said that the lesions erupted 6 days earlier, and indicated that he had a history of recurrent oral aphthous ulcers.

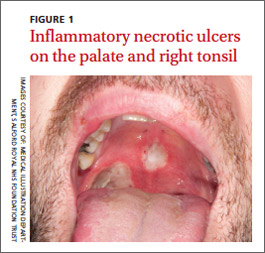

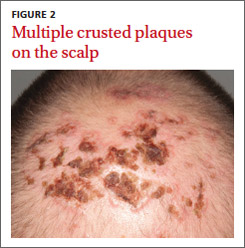

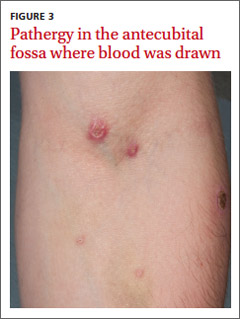

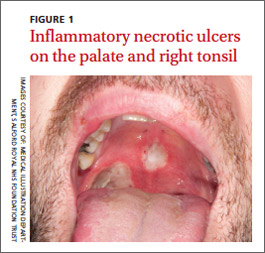

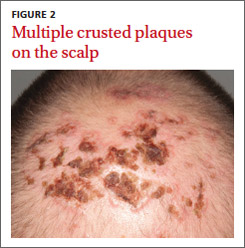

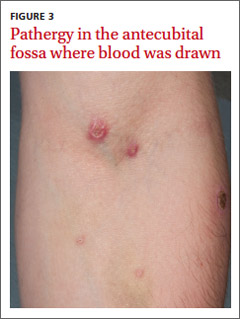

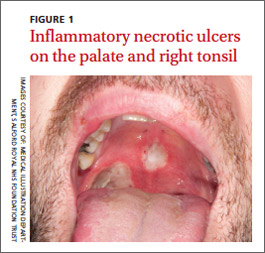

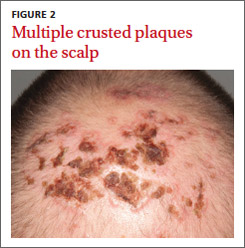

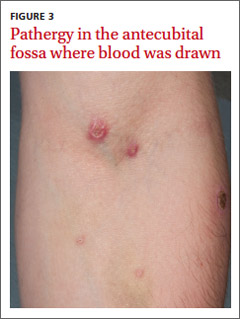

Physical examination revealed 2 large inflammatory necrotic ulcers on his palate and right tonsil, with multiple small ulcers on the border of his tongue (FIGURE 1). Skin examination revealed scattered crateriform ulcerated plaques—particularly over his forearms, back, and scalp (FIGURE 2). Genital examination revealed a large necrotic ulcer underneath his glans penis, with several satellite perigenital ulcers in the groin. Examination of the antecubital fossa revealed pathergy from a blood test and intravenous cannula (FIGURE 3). There was no ocular involvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Behçet’s disease

We diagnosed Behçet’s disease (BD) in this patient based on his clinical presentation.

BD was first described by Hulushi Behçet in 1937 as a triad of oral ulcers, genital ulcers, and uveitis.1 BD is a rare multisystem inflammatory disorder of unknown cause and is prevalent along the Silk Road, an ancient trade route from the Far East to the Mediterranean.

The prevalence is highest in Turkey (80-370/100,000 people) and <1/100,000 people in the United Kingdom and United States.2 Research suggests that the HLA-B*501 allele contributes to the risk of BD in places where the disease is prevalent, but not in Western countries.2

The development of ulceration at the site of superficial skin injury is typical of BD and is termed pathergy. Before he was referred to us, he had had multiple venipunctures while being investigated for a presumed infective illness.

Consider these conditions in the differential

The differential diagnosis includes erythema multiforme, herpes simplex, and Crohn’s disease.

Erythema multiforme is a type of hypersensitivity reaction that commonly occurs in response to infections such as herpes simplex and mycoplasma or medications such as barbiturates or penicillins. It often is diagnosed by the appearance of targetoid skin lesions.

Herpes simplex usually presents with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base and the diagnosis can be confirmed by virology; it responds to antiviral medication.

Crohn’s disease patients may develop abscesses and ulcers in the perineal/perianal region, but they will primarily complain of crampy abdominal pain, loss of appetite, weight loss, and bloody diarrhea.

No lab test to turn to

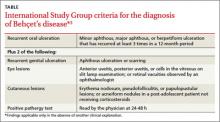

There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for BD; laboratory findings usually reflect systemic inflammation. The International Study Group for BD, however, has derived classification criteria for use in clinical research studies (TABLE).3

Recurrent mouth ulcers—which our patient reported—are essential for the diagnosis of BD. There are typically several such ulcers at any given time and they frequently involve the soft palate and oropharynx. Genital ulceration is the second most common manifestation of BD and is present in 57% to 93% of patients.4 The scrotum is most commonly involved, although the shaft and glans penis may also be affected. Ulcers in the groin and perineum also occur.

Ocular involvement is seen in 30% to 70% of patients and is more frequent and severe in men.5 Panuveitis, posterior uveitis, anterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis, optic neuritis, and retinal vein occlusion cause significant morbidity.

It is induced by a needle prick or injection and is associated with a papule or pustule on an erythematous base. A positive test is defined as a lesion that arises within 24 to 48 hours of the needle prick.

Treatment focuses on alleviating symptoms

There is no curative treatment for BD. The goals of treatment are to prevent end organ damage and alleviate the symptoms.

Mucocutaneous disease is treated with potent topical corticosteroids. Severe attacks are treated with oral corticosteroids—1 mg/kg of prednisolone.7 The drug is tapered and discontinued once the disease is under control. Colchicine or dapsone also is an option. In refractory cases, consider thalidomide (50 mg once a day) or azathioprine (1-3 mg/kg).2,7 An anti-tumor necrosis factor agent also may be considered.

A good outcome for our patient

Our patient was evaluated by an ophthalmology colleague who found no evidence of ocular involvement.

We initially prescribed prednisolone 60 mg once a day for this patient, but when he was weaned off of it, he relapsed. We then prescribed thalidomide 50 mg once a day for 4 months, and the disease resolved completely. The thalidomide was then reduced to 50 mg 3 times a week for 4 weeks, and then stopped completely.

Nearly 2 years later, our patient remains disease free.

CORRESPONDENCE

Arif Aslam, MBChB, MRCP (UK), Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Stott Lane, Salford, Manchester M6 8HD United Kingdom; [email protected]

1. Behçet H. Über rezidivierende, aphthöse, durch ein Virus verursachte Geschwüre am Mund, am Auge und an den Genitalien. Dermatol Wochenschr. 1937;36:1152-1157.

2. Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, et al. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291.

3. Criteria for the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078-1080.

4. Zouboulis CC. Epidemiology of Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1999;150:488-498.

5. Kaçmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, et al; Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Cohort Study Group. Ocular inflammation in Behçet’s disease: incidence of ocular complications and of loss of visual acuity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:828-836.

6. Baker MR, Smith EV, Seidi OA. Pathergy test. Pract Neurol. 2011;11:301-302.

7. Dalvi SR, Yildirim R, Yazici Y. Behcet’s syndrome. Drugs. 2012;72:2223-2241.

A 36-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our facility for rapidly progressive painful ulcers that were affecting his throat, tongue, genital area, and other parts of his body. He said that the lesions erupted 6 days earlier, and indicated that he had a history of recurrent oral aphthous ulcers.

Physical examination revealed 2 large inflammatory necrotic ulcers on his palate and right tonsil, with multiple small ulcers on the border of his tongue (FIGURE 1). Skin examination revealed scattered crateriform ulcerated plaques—particularly over his forearms, back, and scalp (FIGURE 2). Genital examination revealed a large necrotic ulcer underneath his glans penis, with several satellite perigenital ulcers in the groin. Examination of the antecubital fossa revealed pathergy from a blood test and intravenous cannula (FIGURE 3). There was no ocular involvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Behçet’s disease

We diagnosed Behçet’s disease (BD) in this patient based on his clinical presentation.

BD was first described by Hulushi Behçet in 1937 as a triad of oral ulcers, genital ulcers, and uveitis.1 BD is a rare multisystem inflammatory disorder of unknown cause and is prevalent along the Silk Road, an ancient trade route from the Far East to the Mediterranean.

The prevalence is highest in Turkey (80-370/100,000 people) and <1/100,000 people in the United Kingdom and United States.2 Research suggests that the HLA-B*501 allele contributes to the risk of BD in places where the disease is prevalent, but not in Western countries.2

The development of ulceration at the site of superficial skin injury is typical of BD and is termed pathergy. Before he was referred to us, he had had multiple venipunctures while being investigated for a presumed infective illness.

Consider these conditions in the differential

The differential diagnosis includes erythema multiforme, herpes simplex, and Crohn’s disease.

Erythema multiforme is a type of hypersensitivity reaction that commonly occurs in response to infections such as herpes simplex and mycoplasma or medications such as barbiturates or penicillins. It often is diagnosed by the appearance of targetoid skin lesions.

Herpes simplex usually presents with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base and the diagnosis can be confirmed by virology; it responds to antiviral medication.

Crohn’s disease patients may develop abscesses and ulcers in the perineal/perianal region, but they will primarily complain of crampy abdominal pain, loss of appetite, weight loss, and bloody diarrhea.

No lab test to turn to

There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for BD; laboratory findings usually reflect systemic inflammation. The International Study Group for BD, however, has derived classification criteria for use in clinical research studies (TABLE).3

Recurrent mouth ulcers—which our patient reported—are essential for the diagnosis of BD. There are typically several such ulcers at any given time and they frequently involve the soft palate and oropharynx. Genital ulceration is the second most common manifestation of BD and is present in 57% to 93% of patients.4 The scrotum is most commonly involved, although the shaft and glans penis may also be affected. Ulcers in the groin and perineum also occur.

Ocular involvement is seen in 30% to 70% of patients and is more frequent and severe in men.5 Panuveitis, posterior uveitis, anterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis, optic neuritis, and retinal vein occlusion cause significant morbidity.

It is induced by a needle prick or injection and is associated with a papule or pustule on an erythematous base. A positive test is defined as a lesion that arises within 24 to 48 hours of the needle prick.

Treatment focuses on alleviating symptoms

There is no curative treatment for BD. The goals of treatment are to prevent end organ damage and alleviate the symptoms.

Mucocutaneous disease is treated with potent topical corticosteroids. Severe attacks are treated with oral corticosteroids—1 mg/kg of prednisolone.7 The drug is tapered and discontinued once the disease is under control. Colchicine or dapsone also is an option. In refractory cases, consider thalidomide (50 mg once a day) or azathioprine (1-3 mg/kg).2,7 An anti-tumor necrosis factor agent also may be considered.

A good outcome for our patient

Our patient was evaluated by an ophthalmology colleague who found no evidence of ocular involvement.

We initially prescribed prednisolone 60 mg once a day for this patient, but when he was weaned off of it, he relapsed. We then prescribed thalidomide 50 mg once a day for 4 months, and the disease resolved completely. The thalidomide was then reduced to 50 mg 3 times a week for 4 weeks, and then stopped completely.

Nearly 2 years later, our patient remains disease free.

CORRESPONDENCE

Arif Aslam, MBChB, MRCP (UK), Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Stott Lane, Salford, Manchester M6 8HD United Kingdom; [email protected]

A 36-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our facility for rapidly progressive painful ulcers that were affecting his throat, tongue, genital area, and other parts of his body. He said that the lesions erupted 6 days earlier, and indicated that he had a history of recurrent oral aphthous ulcers.

Physical examination revealed 2 large inflammatory necrotic ulcers on his palate and right tonsil, with multiple small ulcers on the border of his tongue (FIGURE 1). Skin examination revealed scattered crateriform ulcerated plaques—particularly over his forearms, back, and scalp (FIGURE 2). Genital examination revealed a large necrotic ulcer underneath his glans penis, with several satellite perigenital ulcers in the groin. Examination of the antecubital fossa revealed pathergy from a blood test and intravenous cannula (FIGURE 3). There was no ocular involvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Behçet’s disease

We diagnosed Behçet’s disease (BD) in this patient based on his clinical presentation.

BD was first described by Hulushi Behçet in 1937 as a triad of oral ulcers, genital ulcers, and uveitis.1 BD is a rare multisystem inflammatory disorder of unknown cause and is prevalent along the Silk Road, an ancient trade route from the Far East to the Mediterranean.

The prevalence is highest in Turkey (80-370/100,000 people) and <1/100,000 people in the United Kingdom and United States.2 Research suggests that the HLA-B*501 allele contributes to the risk of BD in places where the disease is prevalent, but not in Western countries.2

The development of ulceration at the site of superficial skin injury is typical of BD and is termed pathergy. Before he was referred to us, he had had multiple venipunctures while being investigated for a presumed infective illness.

Consider these conditions in the differential

The differential diagnosis includes erythema multiforme, herpes simplex, and Crohn’s disease.

Erythema multiforme is a type of hypersensitivity reaction that commonly occurs in response to infections such as herpes simplex and mycoplasma or medications such as barbiturates or penicillins. It often is diagnosed by the appearance of targetoid skin lesions.

Herpes simplex usually presents with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base and the diagnosis can be confirmed by virology; it responds to antiviral medication.

Crohn’s disease patients may develop abscesses and ulcers in the perineal/perianal region, but they will primarily complain of crampy abdominal pain, loss of appetite, weight loss, and bloody diarrhea.

No lab test to turn to

There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for BD; laboratory findings usually reflect systemic inflammation. The International Study Group for BD, however, has derived classification criteria for use in clinical research studies (TABLE).3

Recurrent mouth ulcers—which our patient reported—are essential for the diagnosis of BD. There are typically several such ulcers at any given time and they frequently involve the soft palate and oropharynx. Genital ulceration is the second most common manifestation of BD and is present in 57% to 93% of patients.4 The scrotum is most commonly involved, although the shaft and glans penis may also be affected. Ulcers in the groin and perineum also occur.

Ocular involvement is seen in 30% to 70% of patients and is more frequent and severe in men.5 Panuveitis, posterior uveitis, anterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis, optic neuritis, and retinal vein occlusion cause significant morbidity.

It is induced by a needle prick or injection and is associated with a papule or pustule on an erythematous base. A positive test is defined as a lesion that arises within 24 to 48 hours of the needle prick.

Treatment focuses on alleviating symptoms

There is no curative treatment for BD. The goals of treatment are to prevent end organ damage and alleviate the symptoms.

Mucocutaneous disease is treated with potent topical corticosteroids. Severe attacks are treated with oral corticosteroids—1 mg/kg of prednisolone.7 The drug is tapered and discontinued once the disease is under control. Colchicine or dapsone also is an option. In refractory cases, consider thalidomide (50 mg once a day) or azathioprine (1-3 mg/kg).2,7 An anti-tumor necrosis factor agent also may be considered.

A good outcome for our patient

Our patient was evaluated by an ophthalmology colleague who found no evidence of ocular involvement.

We initially prescribed prednisolone 60 mg once a day for this patient, but when he was weaned off of it, he relapsed. We then prescribed thalidomide 50 mg once a day for 4 months, and the disease resolved completely. The thalidomide was then reduced to 50 mg 3 times a week for 4 weeks, and then stopped completely.

Nearly 2 years later, our patient remains disease free.

CORRESPONDENCE

Arif Aslam, MBChB, MRCP (UK), Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Stott Lane, Salford, Manchester M6 8HD United Kingdom; [email protected]

1. Behçet H. Über rezidivierende, aphthöse, durch ein Virus verursachte Geschwüre am Mund, am Auge und an den Genitalien. Dermatol Wochenschr. 1937;36:1152-1157.

2. Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, et al. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291.

3. Criteria for the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078-1080.

4. Zouboulis CC. Epidemiology of Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1999;150:488-498.

5. Kaçmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, et al; Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Cohort Study Group. Ocular inflammation in Behçet’s disease: incidence of ocular complications and of loss of visual acuity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:828-836.

6. Baker MR, Smith EV, Seidi OA. Pathergy test. Pract Neurol. 2011;11:301-302.

7. Dalvi SR, Yildirim R, Yazici Y. Behcet’s syndrome. Drugs. 2012;72:2223-2241.

1. Behçet H. Über rezidivierende, aphthöse, durch ein Virus verursachte Geschwüre am Mund, am Auge und an den Genitalien. Dermatol Wochenschr. 1937;36:1152-1157.

2. Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, et al. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291.

3. Criteria for the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078-1080.

4. Zouboulis CC. Epidemiology of Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1999;150:488-498.

5. Kaçmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, et al; Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases Cohort Study Group. Ocular inflammation in Behçet’s disease: incidence of ocular complications and of loss of visual acuity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:828-836.

6. Baker MR, Smith EV, Seidi OA. Pathergy test. Pract Neurol. 2011;11:301-302.

7. Dalvi SR, Yildirim R, Yazici Y. Behcet’s syndrome. Drugs. 2012;72:2223-2241.

Papillae on tongue

The child had a strawberry tongue and scarlet fever caused by strep pharyngitis. The tongue had prominent papillae along with erythema, making it resemble a strawberry. Strawberry tongue is most commonly seen in children with scarlet fever or Kawasaki disease. Strawberry tongue usually develops within the first 2 to 3 days of illness. A white or yellowish coating usually precedes the classic red tongue with white papillae.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis to the mother and prescribed oral penicillin VK. She also recommended ibuprofen for the fever and sore throat. The girl felt somewhat better by the next day, and the mother continued to give the penicillin for the full 10 days as directed to prevent rheumatic fever.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sanders MJ, French L. Scarlet fever and strawberry tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:208-212.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as a portable app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

The child had a strawberry tongue and scarlet fever caused by strep pharyngitis. The tongue had prominent papillae along with erythema, making it resemble a strawberry. Strawberry tongue is most commonly seen in children with scarlet fever or Kawasaki disease. Strawberry tongue usually develops within the first 2 to 3 days of illness. A white or yellowish coating usually precedes the classic red tongue with white papillae.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis to the mother and prescribed oral penicillin VK. She also recommended ibuprofen for the fever and sore throat. The girl felt somewhat better by the next day, and the mother continued to give the penicillin for the full 10 days as directed to prevent rheumatic fever.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sanders MJ, French L. Scarlet fever and strawberry tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:208-212.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as a portable app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

The child had a strawberry tongue and scarlet fever caused by strep pharyngitis. The tongue had prominent papillae along with erythema, making it resemble a strawberry. Strawberry tongue is most commonly seen in children with scarlet fever or Kawasaki disease. Strawberry tongue usually develops within the first 2 to 3 days of illness. A white or yellowish coating usually precedes the classic red tongue with white papillae.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis to the mother and prescribed oral penicillin VK. She also recommended ibuprofen for the fever and sore throat. The girl felt somewhat better by the next day, and the mother continued to give the penicillin for the full 10 days as directed to prevent rheumatic fever.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sanders MJ, French L. Scarlet fever and strawberry tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:208-212.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as a portable app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

Rash on trunk

The FP diagnosed scarlet fever based on the scarlatiniform rash, the fever, and the pharyngitis. Scarlet fever is an illness caused by toxin-producing group A β-hemolytic streptococci.

Most commonly, scarlet fever evolves from an exudative pharyngitis. Headache, sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, decreased oral intake, malaise, and fever may precede rash. Forchheimer spots (palatal and uvular petechiae and erythematous macules) may be present. The sandpaper rash, associated with blanching erythema and occasional pruritus, erupts 1 to 2 days after the fever starts.

Pastia’s lines are pink or red lines seen in the body folds (especially elbows and axillae) during scarlet fever. Linear hyperpigmentation may persist after the rash fades. Desquamation of the skin (especially of the hands and feet) ensues 3 to 4 days after the rash fades, and can persist for 2 to 4 weeks.

Scarlet fever usually follows a benign course; it is not the killer of children that it was in the pre-antibiotic era.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis to the mother and prescribed oral penicillin VK. The boy felt markedly better by the next day, and his mother continued to give him the penicillin for the full 10 days to prevent rheumatic fever.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sanders MJ, French L. Scarlet fever and strawberry tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:208-212.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed scarlet fever based on the scarlatiniform rash, the fever, and the pharyngitis. Scarlet fever is an illness caused by toxin-producing group A β-hemolytic streptococci.

Most commonly, scarlet fever evolves from an exudative pharyngitis. Headache, sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, decreased oral intake, malaise, and fever may precede rash. Forchheimer spots (palatal and uvular petechiae and erythematous macules) may be present. The sandpaper rash, associated with blanching erythema and occasional pruritus, erupts 1 to 2 days after the fever starts.

Pastia’s lines are pink or red lines seen in the body folds (especially elbows and axillae) during scarlet fever. Linear hyperpigmentation may persist after the rash fades. Desquamation of the skin (especially of the hands and feet) ensues 3 to 4 days after the rash fades, and can persist for 2 to 4 weeks.

Scarlet fever usually follows a benign course; it is not the killer of children that it was in the pre-antibiotic era.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis to the mother and prescribed oral penicillin VK. The boy felt markedly better by the next day, and his mother continued to give him the penicillin for the full 10 days to prevent rheumatic fever.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sanders MJ, French L. Scarlet fever and strawberry tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:208-212.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed scarlet fever based on the scarlatiniform rash, the fever, and the pharyngitis. Scarlet fever is an illness caused by toxin-producing group A β-hemolytic streptococci.

Most commonly, scarlet fever evolves from an exudative pharyngitis. Headache, sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, decreased oral intake, malaise, and fever may precede rash. Forchheimer spots (palatal and uvular petechiae and erythematous macules) may be present. The sandpaper rash, associated with blanching erythema and occasional pruritus, erupts 1 to 2 days after the fever starts.

Pastia’s lines are pink or red lines seen in the body folds (especially elbows and axillae) during scarlet fever. Linear hyperpigmentation may persist after the rash fades. Desquamation of the skin (especially of the hands and feet) ensues 3 to 4 days after the rash fades, and can persist for 2 to 4 weeks.

Scarlet fever usually follows a benign course; it is not the killer of children that it was in the pre-antibiotic era.

In this case, the FP explained the diagnosis to the mother and prescribed oral penicillin VK. The boy felt markedly better by the next day, and his mother continued to give him the penicillin for the full 10 days to prevent rheumatic fever.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sanders MJ, French L. Scarlet fever and strawberry tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:208-212.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/ref=dp_ob_title_bk

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/