User login

Blisters on an elderly woman’s toes

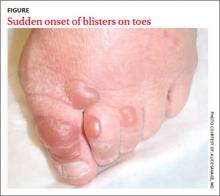

A 69-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and depression presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-day history of blisters on the dorsal aspect of her toes on both feet. She had been wearing sandals so as not to disrupt them. The bullae appeared over the course of one day and progressively grew. The patient had no fever, chills, pain, or itching. She said she’d never had blisters like these before, and she had no history of cellulitis; she also denied trauma to her feet. There were no recent changes to any prescription or nonprescription medications. She also had not had any prolonged exposure to the sun or anything new that would suggest contact dermatitis.

The physical exam revealed an otherwise healthy woman with multiple, clear, fluid-filled bullae of varying sizes on her toes (FIGURE). There was no erythema, warmth, or tenderness. She could walk without difficulty. Her vital signs were normal. A white blood cell count and differential were normal, as well.

Our patient was admitted because of a mistaken concern for cellulitis, despite the absence of any systemic findings or surrounding erythema. She was discharged the next day with no change in status and without treatment. She returned to the ED several days later with the bullae still intact; a biopsy was performed and sent for immunofluorescence.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Bullosis diabeticorum

Direct immunofluorescence was negative. This, along with the patient’s history of diabetes, led us to diagnose bullosis diabeticorum in this patient. This condition, also known as bullous disease of diabetes, is characterized by abrupt development of noninflammatory bullae on acral areas in patients with diabetes. The skin appears normal except for the bullae.1 Bullosis diabeticorum occurs in just .5% of patients with diabetes.2 It is twice as common in men as in women.2

The etiology of bullosis diabeticorum is unknown. The acral location suggests that trauma may be a contributing factor. Although electron microscopy has suggested an abnormality in anchoring fibrils, this cellular change does not fully explain the development of multiple blisters at varying sites. Glycemic control is not thought to play a role.2

A large differential

The distribution of lesions and the presence—or absence—of systemic symptoms go a long way toward narrowing the differential of blistering diseases. The presence of generalized blistering and systemic symptoms would suggest conditions related to medication exposure, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis; infectious etiologies (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome); autoimmune causes; or underlying malignancy.3 Generalized blistering in the absence of systemic symptoms would support diagnoses such as bullous impetigo and pemphigoid.3

Lesion distribution provides important clues, too. Sun exposure-related causes typically leave lesions on the hands and forearms, not just the toes. A dermatomal distribution would suggest herpes zoster. A linear distribution of blisters argues for contact dermatitis. Mucous membrane involvement would suggest etiologies such as herpes simplex virus, erythema multiforme, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Some conditions cannot be excluded from the differential diagnosis upon presentation. Hereditary epidermolysis bullosa (EB) represents a set of inherited diseases in which trauma causes blisters. Localized EB simplex, Weber-Cockayne subtype, can present in adulthood. Blisters can result from trauma on the hands or feet after excessive exercise.4 Although our patient did not give a history of excessive exercise, and this condition is rare, it and similar conditions must be ruled out.

Making the diagnosis

A diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum can be made when biopsy with immunofluorescence excludes other histologically similar entities such as EB, noninflammatory bullous pemphigoid, and porphyria cutanea tarda. And while immunofluorescence findings are typically negative, elevated levels of immunoglobulin M and C3 have, on occasion, been reported.5,6 Cultures are warranted only if a secondary infection is suspected.

Treatment is usually unnecessary

The bullae of this condition spontaneously resolve over several weeks without treatment, but tend to recur. The lesions typically heal without significant scarring, although they may have a darker pigmentation after the first occurrence.4 Treatment may be warranted if a patient develops a secondary infection.

In our patient’s case…The bullae resolved within 2 weeks without treatment, although mild hyperpigmentation remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lisa Mims, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 5 Charleston Center Drive, Suite 263, MSC 192, Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected]

1. Kramer DW. Early or warning signs of impending gangrene in diabetes. Med J Rec. 1930;132:338-342.

2. Poh-Fitzpatrick MB, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Bullous disease of diabetes. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1062235-overview. Accessed March 31, 2014.

3. Hull C, Zone JJ. Approach to the patient with cutaneous blisters. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-cutaneous-blisters. Accessed March 11, 2014.

4. Rocca FF, Pereyra E. Phlyctenar lesions in the feet of diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1963;12:220-222.

5. James WD, Odom RB, Goette DK. Bullous eruption of diabetes. A case with positive immunofluorescence microscopy findings. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1191-1192.

6. Basarab T, Munn SE, McGrath J, et al. Bullous diabeticorum. A case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:218-220.

A 69-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and depression presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-day history of blisters on the dorsal aspect of her toes on both feet. She had been wearing sandals so as not to disrupt them. The bullae appeared over the course of one day and progressively grew. The patient had no fever, chills, pain, or itching. She said she’d never had blisters like these before, and she had no history of cellulitis; she also denied trauma to her feet. There were no recent changes to any prescription or nonprescription medications. She also had not had any prolonged exposure to the sun or anything new that would suggest contact dermatitis.

The physical exam revealed an otherwise healthy woman with multiple, clear, fluid-filled bullae of varying sizes on her toes (FIGURE). There was no erythema, warmth, or tenderness. She could walk without difficulty. Her vital signs were normal. A white blood cell count and differential were normal, as well.

Our patient was admitted because of a mistaken concern for cellulitis, despite the absence of any systemic findings or surrounding erythema. She was discharged the next day with no change in status and without treatment. She returned to the ED several days later with the bullae still intact; a biopsy was performed and sent for immunofluorescence.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Bullosis diabeticorum

Direct immunofluorescence was negative. This, along with the patient’s history of diabetes, led us to diagnose bullosis diabeticorum in this patient. This condition, also known as bullous disease of diabetes, is characterized by abrupt development of noninflammatory bullae on acral areas in patients with diabetes. The skin appears normal except for the bullae.1 Bullosis diabeticorum occurs in just .5% of patients with diabetes.2 It is twice as common in men as in women.2

The etiology of bullosis diabeticorum is unknown. The acral location suggests that trauma may be a contributing factor. Although electron microscopy has suggested an abnormality in anchoring fibrils, this cellular change does not fully explain the development of multiple blisters at varying sites. Glycemic control is not thought to play a role.2

A large differential

The distribution of lesions and the presence—or absence—of systemic symptoms go a long way toward narrowing the differential of blistering diseases. The presence of generalized blistering and systemic symptoms would suggest conditions related to medication exposure, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis; infectious etiologies (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome); autoimmune causes; or underlying malignancy.3 Generalized blistering in the absence of systemic symptoms would support diagnoses such as bullous impetigo and pemphigoid.3

Lesion distribution provides important clues, too. Sun exposure-related causes typically leave lesions on the hands and forearms, not just the toes. A dermatomal distribution would suggest herpes zoster. A linear distribution of blisters argues for contact dermatitis. Mucous membrane involvement would suggest etiologies such as herpes simplex virus, erythema multiforme, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Some conditions cannot be excluded from the differential diagnosis upon presentation. Hereditary epidermolysis bullosa (EB) represents a set of inherited diseases in which trauma causes blisters. Localized EB simplex, Weber-Cockayne subtype, can present in adulthood. Blisters can result from trauma on the hands or feet after excessive exercise.4 Although our patient did not give a history of excessive exercise, and this condition is rare, it and similar conditions must be ruled out.

Making the diagnosis

A diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum can be made when biopsy with immunofluorescence excludes other histologically similar entities such as EB, noninflammatory bullous pemphigoid, and porphyria cutanea tarda. And while immunofluorescence findings are typically negative, elevated levels of immunoglobulin M and C3 have, on occasion, been reported.5,6 Cultures are warranted only if a secondary infection is suspected.

Treatment is usually unnecessary

The bullae of this condition spontaneously resolve over several weeks without treatment, but tend to recur. The lesions typically heal without significant scarring, although they may have a darker pigmentation after the first occurrence.4 Treatment may be warranted if a patient develops a secondary infection.

In our patient’s case…The bullae resolved within 2 weeks without treatment, although mild hyperpigmentation remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lisa Mims, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 5 Charleston Center Drive, Suite 263, MSC 192, Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected]

A 69-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and depression presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-day history of blisters on the dorsal aspect of her toes on both feet. She had been wearing sandals so as not to disrupt them. The bullae appeared over the course of one day and progressively grew. The patient had no fever, chills, pain, or itching. She said she’d never had blisters like these before, and she had no history of cellulitis; she also denied trauma to her feet. There were no recent changes to any prescription or nonprescription medications. She also had not had any prolonged exposure to the sun or anything new that would suggest contact dermatitis.

The physical exam revealed an otherwise healthy woman with multiple, clear, fluid-filled bullae of varying sizes on her toes (FIGURE). There was no erythema, warmth, or tenderness. She could walk without difficulty. Her vital signs were normal. A white blood cell count and differential were normal, as well.

Our patient was admitted because of a mistaken concern for cellulitis, despite the absence of any systemic findings or surrounding erythema. She was discharged the next day with no change in status and without treatment. She returned to the ED several days later with the bullae still intact; a biopsy was performed and sent for immunofluorescence.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Bullosis diabeticorum

Direct immunofluorescence was negative. This, along with the patient’s history of diabetes, led us to diagnose bullosis diabeticorum in this patient. This condition, also known as bullous disease of diabetes, is characterized by abrupt development of noninflammatory bullae on acral areas in patients with diabetes. The skin appears normal except for the bullae.1 Bullosis diabeticorum occurs in just .5% of patients with diabetes.2 It is twice as common in men as in women.2

The etiology of bullosis diabeticorum is unknown. The acral location suggests that trauma may be a contributing factor. Although electron microscopy has suggested an abnormality in anchoring fibrils, this cellular change does not fully explain the development of multiple blisters at varying sites. Glycemic control is not thought to play a role.2

A large differential

The distribution of lesions and the presence—or absence—of systemic symptoms go a long way toward narrowing the differential of blistering diseases. The presence of generalized blistering and systemic symptoms would suggest conditions related to medication exposure, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis; infectious etiologies (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome); autoimmune causes; or underlying malignancy.3 Generalized blistering in the absence of systemic symptoms would support diagnoses such as bullous impetigo and pemphigoid.3

Lesion distribution provides important clues, too. Sun exposure-related causes typically leave lesions on the hands and forearms, not just the toes. A dermatomal distribution would suggest herpes zoster. A linear distribution of blisters argues for contact dermatitis. Mucous membrane involvement would suggest etiologies such as herpes simplex virus, erythema multiforme, pemphigus vulgaris, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Some conditions cannot be excluded from the differential diagnosis upon presentation. Hereditary epidermolysis bullosa (EB) represents a set of inherited diseases in which trauma causes blisters. Localized EB simplex, Weber-Cockayne subtype, can present in adulthood. Blisters can result from trauma on the hands or feet after excessive exercise.4 Although our patient did not give a history of excessive exercise, and this condition is rare, it and similar conditions must be ruled out.

Making the diagnosis

A diagnosis of bullosis diabeticorum can be made when biopsy with immunofluorescence excludes other histologically similar entities such as EB, noninflammatory bullous pemphigoid, and porphyria cutanea tarda. And while immunofluorescence findings are typically negative, elevated levels of immunoglobulin M and C3 have, on occasion, been reported.5,6 Cultures are warranted only if a secondary infection is suspected.

Treatment is usually unnecessary

The bullae of this condition spontaneously resolve over several weeks without treatment, but tend to recur. The lesions typically heal without significant scarring, although they may have a darker pigmentation after the first occurrence.4 Treatment may be warranted if a patient develops a secondary infection.

In our patient’s case…The bullae resolved within 2 weeks without treatment, although mild hyperpigmentation remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lisa Mims, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 5 Charleston Center Drive, Suite 263, MSC 192, Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected]

1. Kramer DW. Early or warning signs of impending gangrene in diabetes. Med J Rec. 1930;132:338-342.

2. Poh-Fitzpatrick MB, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Bullous disease of diabetes. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1062235-overview. Accessed March 31, 2014.

3. Hull C, Zone JJ. Approach to the patient with cutaneous blisters. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-cutaneous-blisters. Accessed March 11, 2014.

4. Rocca FF, Pereyra E. Phlyctenar lesions in the feet of diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1963;12:220-222.

5. James WD, Odom RB, Goette DK. Bullous eruption of diabetes. A case with positive immunofluorescence microscopy findings. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1191-1192.

6. Basarab T, Munn SE, McGrath J, et al. Bullous diabeticorum. A case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:218-220.

1. Kramer DW. Early or warning signs of impending gangrene in diabetes. Med J Rec. 1930;132:338-342.

2. Poh-Fitzpatrick MB, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Bullous disease of diabetes. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1062235-overview. Accessed March 31, 2014.

3. Hull C, Zone JJ. Approach to the patient with cutaneous blisters. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-cutaneous-blisters. Accessed March 11, 2014.

4. Rocca FF, Pereyra E. Phlyctenar lesions in the feet of diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1963;12:220-222.

5. James WD, Odom RB, Goette DK. Bullous eruption of diabetes. A case with positive immunofluorescence microscopy findings. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1191-1192.

6. Basarab T, Munn SE, McGrath J, et al. Bullous diabeticorum. A case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:218-220.

Lesions on feet and hands

The FP hospitalized the patient for suspected acute bacterial endocarditis and ordered an echocardiogram, which showed vegetations on the tricuspid valve. He realized that the non-painful lesions on the palms and soles were Janeway lesions. The one painful lesion within the pulp of the big toe was an Osler node. (Remember “O” for “ouch” and Osler.) Janeway lesions are caused by septic emboli that form microabscesses in the dermis (without epidermal involvement). Osler nodes are tender and the result of the deposition of immune complexes.

Other clinical features of endocarditis include:

- fever, seen in 85% to 99% of patients. It is typically low-grade—less than 39°C (102.2°F).

- new or changing heart murmur

- septic emboli, seen in up to 60% of patients

- intracranial hemorrhages, seen in up to 40% of patients

- mycotic aneurysms

- splinter hemorrhages

- glomerulonephritis

- Roth spots—that is, retinal hemorrhages from microemboli

- positive rheumatoid factor.

Treatment begins with empiric antibiotics after the initial blood cultures are drawn. It is important to cover Staphylococcus aureus in injection drug users.

In this case, the FP started the patient on nafcillin 2 g every 4 hours and gentamicin 1 mg/kg every 8 hours. Vancomycin is used instead of nafcillin when there is a concern about methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a prior history of MRSA infection.

This patient’s blood cultures grew out methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, so her antibiotic regimen was continued for 6 weeks with full clearance of the endocarditis. The patient was also willing to enter a drug rehabilitation program.

Photos courtesy of David A. Kasper DO. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Endocarditis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:287-291.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP hospitalized the patient for suspected acute bacterial endocarditis and ordered an echocardiogram, which showed vegetations on the tricuspid valve. He realized that the non-painful lesions on the palms and soles were Janeway lesions. The one painful lesion within the pulp of the big toe was an Osler node. (Remember “O” for “ouch” and Osler.) Janeway lesions are caused by septic emboli that form microabscesses in the dermis (without epidermal involvement). Osler nodes are tender and the result of the deposition of immune complexes.

Other clinical features of endocarditis include:

- fever, seen in 85% to 99% of patients. It is typically low-grade—less than 39°C (102.2°F).

- new or changing heart murmur

- septic emboli, seen in up to 60% of patients

- intracranial hemorrhages, seen in up to 40% of patients

- mycotic aneurysms

- splinter hemorrhages

- glomerulonephritis

- Roth spots—that is, retinal hemorrhages from microemboli

- positive rheumatoid factor.

Treatment begins with empiric antibiotics after the initial blood cultures are drawn. It is important to cover Staphylococcus aureus in injection drug users.

In this case, the FP started the patient on nafcillin 2 g every 4 hours and gentamicin 1 mg/kg every 8 hours. Vancomycin is used instead of nafcillin when there is a concern about methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a prior history of MRSA infection.

This patient’s blood cultures grew out methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, so her antibiotic regimen was continued for 6 weeks with full clearance of the endocarditis. The patient was also willing to enter a drug rehabilitation program.

Photos courtesy of David A. Kasper DO. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Endocarditis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:287-291.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP hospitalized the patient for suspected acute bacterial endocarditis and ordered an echocardiogram, which showed vegetations on the tricuspid valve. He realized that the non-painful lesions on the palms and soles were Janeway lesions. The one painful lesion within the pulp of the big toe was an Osler node. (Remember “O” for “ouch” and Osler.) Janeway lesions are caused by septic emboli that form microabscesses in the dermis (without epidermal involvement). Osler nodes are tender and the result of the deposition of immune complexes.

Other clinical features of endocarditis include:

- fever, seen in 85% to 99% of patients. It is typically low-grade—less than 39°C (102.2°F).

- new or changing heart murmur

- septic emboli, seen in up to 60% of patients

- intracranial hemorrhages, seen in up to 40% of patients

- mycotic aneurysms

- splinter hemorrhages

- glomerulonephritis

- Roth spots—that is, retinal hemorrhages from microemboli

- positive rheumatoid factor.

Treatment begins with empiric antibiotics after the initial blood cultures are drawn. It is important to cover Staphylococcus aureus in injection drug users.

In this case, the FP started the patient on nafcillin 2 g every 4 hours and gentamicin 1 mg/kg every 8 hours. Vancomycin is used instead of nafcillin when there is a concern about methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a prior history of MRSA infection.

This patient’s blood cultures grew out methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, so her antibiotic regimen was continued for 6 weeks with full clearance of the endocarditis. The patient was also willing to enter a drug rehabilitation program.

Photos courtesy of David A. Kasper DO. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Endocarditis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:287-291.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Enlarged gums

The FP diagnosed gingival overgrowth (hyperplasia) secondary to the use of phenytoin.

Gingival overgrowth (GO) can be a hereditary condition or an adverse effect of certain systemic drugs, including phenytoin, cyclosporine, or calcium channel blockers. The estimated prevalence of GO is 15% to 50% among patients taking phenytoin, up to 70% in patients who take cyclosporine for more than 3 months, and 10% to 20% in patients treated with calcium channel blockers. In addition to its cosmetic effect, GO can make good oral hygiene more difficult to maintain.

Patients with GO should practice good oral hygiene, including going to the dentist for cleanings at least every 3 months to control plaque. In a 12-month study of pediatric transplant patients taking cyclosporine, a group that used a power toothbrush and received oral hygiene instructions had less severe GO than did the control group.

When possible, stopping a drug that induces GO may reverse the condition (except in patients taking phenytoin, for whom GO is not reversible). If the medication cannot be stopped, reducing the dose when possible may be an option, because GO can be dose-dependent. Patients with GO need to be monitored by a periodontist or oral medicine specialist for as long as they are taking a medication that can induce GO.

In this case, the FP recommended good oral hygiene, including going to the dentist for cleanings at least every 3 months to control plaque. The patient continued to take phenytoin to prevent seizures.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Gingival overgrowth. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:240-243.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed gingival overgrowth (hyperplasia) secondary to the use of phenytoin.

Gingival overgrowth (GO) can be a hereditary condition or an adverse effect of certain systemic drugs, including phenytoin, cyclosporine, or calcium channel blockers. The estimated prevalence of GO is 15% to 50% among patients taking phenytoin, up to 70% in patients who take cyclosporine for more than 3 months, and 10% to 20% in patients treated with calcium channel blockers. In addition to its cosmetic effect, GO can make good oral hygiene more difficult to maintain.

Patients with GO should practice good oral hygiene, including going to the dentist for cleanings at least every 3 months to control plaque. In a 12-month study of pediatric transplant patients taking cyclosporine, a group that used a power toothbrush and received oral hygiene instructions had less severe GO than did the control group.

When possible, stopping a drug that induces GO may reverse the condition (except in patients taking phenytoin, for whom GO is not reversible). If the medication cannot be stopped, reducing the dose when possible may be an option, because GO can be dose-dependent. Patients with GO need to be monitored by a periodontist or oral medicine specialist for as long as they are taking a medication that can induce GO.

In this case, the FP recommended good oral hygiene, including going to the dentist for cleanings at least every 3 months to control plaque. The patient continued to take phenytoin to prevent seizures.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Gingival overgrowth. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:240-243.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed gingival overgrowth (hyperplasia) secondary to the use of phenytoin.

Gingival overgrowth (GO) can be a hereditary condition or an adverse effect of certain systemic drugs, including phenytoin, cyclosporine, or calcium channel blockers. The estimated prevalence of GO is 15% to 50% among patients taking phenytoin, up to 70% in patients who take cyclosporine for more than 3 months, and 10% to 20% in patients treated with calcium channel blockers. In addition to its cosmetic effect, GO can make good oral hygiene more difficult to maintain.

Patients with GO should practice good oral hygiene, including going to the dentist for cleanings at least every 3 months to control plaque. In a 12-month study of pediatric transplant patients taking cyclosporine, a group that used a power toothbrush and received oral hygiene instructions had less severe GO than did the control group.

When possible, stopping a drug that induces GO may reverse the condition (except in patients taking phenytoin, for whom GO is not reversible). If the medication cannot be stopped, reducing the dose when possible may be an option, because GO can be dose-dependent. Patients with GO need to be monitored by a periodontist or oral medicine specialist for as long as they are taking a medication that can induce GO.

In this case, the FP recommended good oral hygiene, including going to the dentist for cleanings at least every 3 months to control plaque. The patient continued to take phenytoin to prevent seizures.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Gingival overgrowth. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:240-243.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Swollen, bleeding gums

The FP explained to the patient that she had gingivitis.

Gingivitis—a reversible inflammation of the gingiva--occurs when gingival tissue is exposed to plaque and tartar for a prolonged period of time. Gingivitis may be classified by appearance (eg, ulcerative, hemorrhagic), etiology (eg, drugs, hormones), duration (eg, acute, chronic), or quality (eg, mild, moderate, or severe). Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG)—also known as trench mouth—is a severe form of gingivitis associated with α-hemolytic streptococci, anaerobic fusiform bacteria, and nontreponemal oral spirochetes. Predisposing factors include diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus, and chemotherapy.

The most common form of gingivitis is chronic gingivitis induced by plaque, which occurs in one-half of the population. The inflammation worsens as mineralized plaque forms tartar at and below the gum line. The plaque that covers tartar causes destruction of bone (an irreversible condition) and loosens teeth, which can result in tooth loss.

Gingivitis by itself does not affect the underlying supporting structures of the teeth and may persist for months or years without progressing to periodontal disease (periodontitis). Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that includes gingivitis and a loss of connective tissue and bone support for the teeth. Periodontitis is a major cause of tooth loss in adults.

All patients should receive ongoing care from a dental professional to prevent periodontal disease. Dental experts recommend that patients brush their teeth twice a day and floss daily. Some experts suggest that powered toothbrushes offer advantages over manual brushing, but this remains unproven. Strong evidence from systematic reviews supports the efficacy of chlorhexidine as an antiplaque, antigingivitis mouth rinse. Mouthwashes should not, however, be used as a replacement for brushing one’s teeth.

In this case, the FP told the patient that she should brush her teeth twice a day and floss daily. He offered her help to quit smoking and referred her to a dentist for a cleaning and full dental examination.

Photo courtesy of Gerald Ferreti, DMD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Gingivitis and periodontal disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:236-239.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained to the patient that she had gingivitis.

Gingivitis—a reversible inflammation of the gingiva--occurs when gingival tissue is exposed to plaque and tartar for a prolonged period of time. Gingivitis may be classified by appearance (eg, ulcerative, hemorrhagic), etiology (eg, drugs, hormones), duration (eg, acute, chronic), or quality (eg, mild, moderate, or severe). Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG)—also known as trench mouth—is a severe form of gingivitis associated with α-hemolytic streptococci, anaerobic fusiform bacteria, and nontreponemal oral spirochetes. Predisposing factors include diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus, and chemotherapy.

The most common form of gingivitis is chronic gingivitis induced by plaque, which occurs in one-half of the population. The inflammation worsens as mineralized plaque forms tartar at and below the gum line. The plaque that covers tartar causes destruction of bone (an irreversible condition) and loosens teeth, which can result in tooth loss.

Gingivitis by itself does not affect the underlying supporting structures of the teeth and may persist for months or years without progressing to periodontal disease (periodontitis). Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that includes gingivitis and a loss of connective tissue and bone support for the teeth. Periodontitis is a major cause of tooth loss in adults.

All patients should receive ongoing care from a dental professional to prevent periodontal disease. Dental experts recommend that patients brush their teeth twice a day and floss daily. Some experts suggest that powered toothbrushes offer advantages over manual brushing, but this remains unproven. Strong evidence from systematic reviews supports the efficacy of chlorhexidine as an antiplaque, antigingivitis mouth rinse. Mouthwashes should not, however, be used as a replacement for brushing one’s teeth.

In this case, the FP told the patient that she should brush her teeth twice a day and floss daily. He offered her help to quit smoking and referred her to a dentist for a cleaning and full dental examination.

Photo courtesy of Gerald Ferreti, DMD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Gingivitis and periodontal disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:236-239.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained to the patient that she had gingivitis.

Gingivitis—a reversible inflammation of the gingiva--occurs when gingival tissue is exposed to plaque and tartar for a prolonged period of time. Gingivitis may be classified by appearance (eg, ulcerative, hemorrhagic), etiology (eg, drugs, hormones), duration (eg, acute, chronic), or quality (eg, mild, moderate, or severe). Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG)—also known as trench mouth—is a severe form of gingivitis associated with α-hemolytic streptococci, anaerobic fusiform bacteria, and nontreponemal oral spirochetes. Predisposing factors include diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus, and chemotherapy.

The most common form of gingivitis is chronic gingivitis induced by plaque, which occurs in one-half of the population. The inflammation worsens as mineralized plaque forms tartar at and below the gum line. The plaque that covers tartar causes destruction of bone (an irreversible condition) and loosens teeth, which can result in tooth loss.

Gingivitis by itself does not affect the underlying supporting structures of the teeth and may persist for months or years without progressing to periodontal disease (periodontitis). Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that includes gingivitis and a loss of connective tissue and bone support for the teeth. Periodontitis is a major cause of tooth loss in adults.

All patients should receive ongoing care from a dental professional to prevent periodontal disease. Dental experts recommend that patients brush their teeth twice a day and floss daily. Some experts suggest that powered toothbrushes offer advantages over manual brushing, but this remains unproven. Strong evidence from systematic reviews supports the efficacy of chlorhexidine as an antiplaque, antigingivitis mouth rinse. Mouthwashes should not, however, be used as a replacement for brushing one’s teeth.

In this case, the FP told the patient that she should brush her teeth twice a day and floss daily. He offered her help to quit smoking and referred her to a dentist for a cleaning and full dental examination.

Photo courtesy of Gerald Ferreti, DMD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Gingivitis and periodontal disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:236-239.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Deep lines in tongue

The FP recognized that the patient had a fissured tongue, and it was likely that she’d had these fissures since birth or early childhood. The FP reassured the patient that the condition has no negative health consequences.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Valdez E, Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Geographic tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:232-235.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP recognized that the patient had a fissured tongue, and it was likely that she’d had these fissures since birth or early childhood. The FP reassured the patient that the condition has no negative health consequences.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Valdez E, Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Geographic tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:232-235.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP recognized that the patient had a fissured tongue, and it was likely that she’d had these fissures since birth or early childhood. The FP reassured the patient that the condition has no negative health consequences.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Valdez E, Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Geographic tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:232-235.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Lesions on the tongue

The FP concluded that the patient had geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis). This is a recurrent, usually asymptomatic inflammatory disorder of the mucosa of the dorsum and lateral borders of the tongue. The lesions are suggestive of a geographic map, with pink continents surrounded by white oceans. The lesions exhibit central erythema (because of atrophy of the filiform papillae) and usually are surrounded by slightly elevated, curving, white-to-yellow borders. The condition typically waxes and wanes over time, so the lesions may appear to be migrating.

The lesions, which do not scar, may last for days to years. Most patients are asymptomatic, but some may complain of pain or burning, especially when eating spicy foods. Suspect systemic intraoral manifestations of psoriasis or reactive arthritis if the patient has psoriatic skin lesions or conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis, or skin involvement suggestive of reactive arthritis.

There are several proposed treatments for symptomatic patients, but there is no evidence to support their use. Topical steroids, such as triamcinolone dental paste, is one option; an oral supplement, such as zinc, vitamin B12, niacin, and riboflavin, is another. Antihistamine mouth rinses (eg, diphenhydramine elixir 12.5 mg per 5 mL diluted in a 1:4 ratio with water) also have been suggested as a treatment option.

In this case, the FP explained to the patient that her condition was benign and that she did not need treatment unless her tongue started to bother her.

Photo courtesy of Michael Huber, DMD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Valdez E, Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Geographic tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:232-235.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP concluded that the patient had geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis). This is a recurrent, usually asymptomatic inflammatory disorder of the mucosa of the dorsum and lateral borders of the tongue. The lesions are suggestive of a geographic map, with pink continents surrounded by white oceans. The lesions exhibit central erythema (because of atrophy of the filiform papillae) and usually are surrounded by slightly elevated, curving, white-to-yellow borders. The condition typically waxes and wanes over time, so the lesions may appear to be migrating.

The lesions, which do not scar, may last for days to years. Most patients are asymptomatic, but some may complain of pain or burning, especially when eating spicy foods. Suspect systemic intraoral manifestations of psoriasis or reactive arthritis if the patient has psoriatic skin lesions or conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis, or skin involvement suggestive of reactive arthritis.

There are several proposed treatments for symptomatic patients, but there is no evidence to support their use. Topical steroids, such as triamcinolone dental paste, is one option; an oral supplement, such as zinc, vitamin B12, niacin, and riboflavin, is another. Antihistamine mouth rinses (eg, diphenhydramine elixir 12.5 mg per 5 mL diluted in a 1:4 ratio with water) also have been suggested as a treatment option.

In this case, the FP explained to the patient that her condition was benign and that she did not need treatment unless her tongue started to bother her.

Photo courtesy of Michael Huber, DMD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Valdez E, Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Geographic tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:232-235.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP concluded that the patient had geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis). This is a recurrent, usually asymptomatic inflammatory disorder of the mucosa of the dorsum and lateral borders of the tongue. The lesions are suggestive of a geographic map, with pink continents surrounded by white oceans. The lesions exhibit central erythema (because of atrophy of the filiform papillae) and usually are surrounded by slightly elevated, curving, white-to-yellow borders. The condition typically waxes and wanes over time, so the lesions may appear to be migrating.

The lesions, which do not scar, may last for days to years. Most patients are asymptomatic, but some may complain of pain or burning, especially when eating spicy foods. Suspect systemic intraoral manifestations of psoriasis or reactive arthritis if the patient has psoriatic skin lesions or conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis, or skin involvement suggestive of reactive arthritis.

There are several proposed treatments for symptomatic patients, but there is no evidence to support their use. Topical steroids, such as triamcinolone dental paste, is one option; an oral supplement, such as zinc, vitamin B12, niacin, and riboflavin, is another. Antihistamine mouth rinses (eg, diphenhydramine elixir 12.5 mg per 5 mL diluted in a 1:4 ratio with water) also have been suggested as a treatment option.

In this case, the FP explained to the patient that her condition was benign and that she did not need treatment unless her tongue started to bother her.

Photo courtesy of Michael Huber, DMD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Valdez E, Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Geographic tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:232-235.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Adolescent with rash on face and scalp

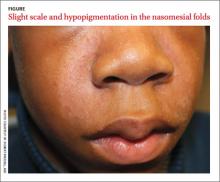

A 13-year-old African American male presented with a 2-year history of a mildly pruritic central facial rash (FIGURE) and dandruff. Recent treatment with hydrocortisone 1% cream and nystatin cream (100,000 U/gm) for 1 week resulted in no improvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Seborrheic dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a chronic dermatitis caused by Malassezia yeast species, including Malassezia (Pityrosporum ovale).1 SD affects 1% to 3% of the general population in the United States and has 2 incidence peaks: the first occurs during infancy and the second between 30 to 50 years of age.2 The abnormal response to the yeast organism leads to inflammation, proliferation, and desquamation.2

The diagnosis of SD is made based on the presence of sharply marginated scaled patches in areas with a high concentration of sebaceous glands including the scalp, eyebrows, and nasomesial folds. Pruritus, erythema, and greasy scales also are commonly seen.3 Raised lateral margins reminiscent of the advancing border of dermatophyte infections and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may also be present in African American patients. Both of these findings in the nasomesial folds, eyebrows, and scalp led to the diagnosis of SD in this patient.

Differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, lichen simplex chronicus

The differential for dandruff includes psoriasis, as well as lichen simplex chronicus and tinea capitis. Psoriasis often is associated with thicker, white micaceous scaling. The latter 2 conditions would not produce the symmetrical scaling in nasomesial folds that we saw with our patient.

SD in the central face can appear similar to pityriasis versicolor, allergic contact dermatitis, and irritant dermatitis (pityriasis alba), but these conditions are not associated with diffuse dandruff.

Antifungals are the mainstay of treatment

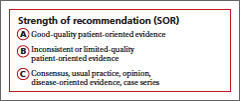

Because there is no cure for SD, the goal of therapy is to control the dermatitis. Topical antifungal agents are used to suppress the Malassezia yeast and topical steroids are used to suppress inflammation. Azole antifungal medications such as ketoconazole are effective and can be used for long periods of time with minimal risk of adverse effects3-5 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C).

Our patient had used nystatin cream, which is effective against Candida yeast infections, but not especially effective for Malassezia sp.6

To reduce inflammation, mild topical steroids such as hydrocortisone cream 2.5% should be used. However, they must be used for short periods to avoid atrophy, telangiectasias, and steroid-induced acne. An alternative evolving treatment is to use a calcineurin inhibitor, such as pimecrolimus cream 1% or tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. These drugs do not exacerbate hypopigmentation, an effect that sometimes is attributed to topical steroids.7

Scalp treatments include shampoos such as ketoconazole 2%, selenium sulfide 2.5%, and ciclopirox 1%.3 Shampoos should be lathered up and left on the scalp for 3 to 5 minutes before rinsing.

Two forms of ketoconazole for our patient

Our patient responded well to ketoconazole cream 2% applied twice daily to the face and other areas without hair and ketoconazole 2% shampoo twice weekly. At a 6-week follow-up, the patient had significant improvement in scaling and pruritus on the central face and scalp. The associated facial hypopigmentation faded over 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Nakabayashi A, Sei Y, Guillot J. Identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor and normal subjects. Med Mycology. 2000;38:337-341.

2. Sampaio AL, Mameri AC, Vargas TJ, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1061-1071;quiz 1072-1074.

3. Naldi L. Seborrhoeic dermatitis. Clin Evid (Online). 2010;2010:pii:1713.

4. Draelos ZD, Feldman SR, Butners V, et al. Long-term safety of ketoconazole foam, 2% in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: results of a phase IV, open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:e1-e6.

5. Apasrawirote W, Udompataikul M, Rattanamongkolgul S. Topical antifungal agents for seborrheic dermatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:756-760.

6. Pedrosa AF, Lisboa, C, Rodrigues AG. Malassezia infections: A medical conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb 22. Epub ahead of print.

7. High WA, Pandya AG. Pilot trial of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in African American adults with associated hypopigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1083-1088.

A 13-year-old African American male presented with a 2-year history of a mildly pruritic central facial rash (FIGURE) and dandruff. Recent treatment with hydrocortisone 1% cream and nystatin cream (100,000 U/gm) for 1 week resulted in no improvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Seborrheic dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a chronic dermatitis caused by Malassezia yeast species, including Malassezia (Pityrosporum ovale).1 SD affects 1% to 3% of the general population in the United States and has 2 incidence peaks: the first occurs during infancy and the second between 30 to 50 years of age.2 The abnormal response to the yeast organism leads to inflammation, proliferation, and desquamation.2

The diagnosis of SD is made based on the presence of sharply marginated scaled patches in areas with a high concentration of sebaceous glands including the scalp, eyebrows, and nasomesial folds. Pruritus, erythema, and greasy scales also are commonly seen.3 Raised lateral margins reminiscent of the advancing border of dermatophyte infections and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may also be present in African American patients. Both of these findings in the nasomesial folds, eyebrows, and scalp led to the diagnosis of SD in this patient.

Differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, lichen simplex chronicus

The differential for dandruff includes psoriasis, as well as lichen simplex chronicus and tinea capitis. Psoriasis often is associated with thicker, white micaceous scaling. The latter 2 conditions would not produce the symmetrical scaling in nasomesial folds that we saw with our patient.

SD in the central face can appear similar to pityriasis versicolor, allergic contact dermatitis, and irritant dermatitis (pityriasis alba), but these conditions are not associated with diffuse dandruff.

Antifungals are the mainstay of treatment

Because there is no cure for SD, the goal of therapy is to control the dermatitis. Topical antifungal agents are used to suppress the Malassezia yeast and topical steroids are used to suppress inflammation. Azole antifungal medications such as ketoconazole are effective and can be used for long periods of time with minimal risk of adverse effects3-5 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C).

Our patient had used nystatin cream, which is effective against Candida yeast infections, but not especially effective for Malassezia sp.6

To reduce inflammation, mild topical steroids such as hydrocortisone cream 2.5% should be used. However, they must be used for short periods to avoid atrophy, telangiectasias, and steroid-induced acne. An alternative evolving treatment is to use a calcineurin inhibitor, such as pimecrolimus cream 1% or tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. These drugs do not exacerbate hypopigmentation, an effect that sometimes is attributed to topical steroids.7

Scalp treatments include shampoos such as ketoconazole 2%, selenium sulfide 2.5%, and ciclopirox 1%.3 Shampoos should be lathered up and left on the scalp for 3 to 5 minutes before rinsing.

Two forms of ketoconazole for our patient

Our patient responded well to ketoconazole cream 2% applied twice daily to the face and other areas without hair and ketoconazole 2% shampoo twice weekly. At a 6-week follow-up, the patient had significant improvement in scaling and pruritus on the central face and scalp. The associated facial hypopigmentation faded over 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

A 13-year-old African American male presented with a 2-year history of a mildly pruritic central facial rash (FIGURE) and dandruff. Recent treatment with hydrocortisone 1% cream and nystatin cream (100,000 U/gm) for 1 week resulted in no improvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Seborrheic dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a chronic dermatitis caused by Malassezia yeast species, including Malassezia (Pityrosporum ovale).1 SD affects 1% to 3% of the general population in the United States and has 2 incidence peaks: the first occurs during infancy and the second between 30 to 50 years of age.2 The abnormal response to the yeast organism leads to inflammation, proliferation, and desquamation.2

The diagnosis of SD is made based on the presence of sharply marginated scaled patches in areas with a high concentration of sebaceous glands including the scalp, eyebrows, and nasomesial folds. Pruritus, erythema, and greasy scales also are commonly seen.3 Raised lateral margins reminiscent of the advancing border of dermatophyte infections and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may also be present in African American patients. Both of these findings in the nasomesial folds, eyebrows, and scalp led to the diagnosis of SD in this patient.

Differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, lichen simplex chronicus

The differential for dandruff includes psoriasis, as well as lichen simplex chronicus and tinea capitis. Psoriasis often is associated with thicker, white micaceous scaling. The latter 2 conditions would not produce the symmetrical scaling in nasomesial folds that we saw with our patient.

SD in the central face can appear similar to pityriasis versicolor, allergic contact dermatitis, and irritant dermatitis (pityriasis alba), but these conditions are not associated with diffuse dandruff.

Antifungals are the mainstay of treatment

Because there is no cure for SD, the goal of therapy is to control the dermatitis. Topical antifungal agents are used to suppress the Malassezia yeast and topical steroids are used to suppress inflammation. Azole antifungal medications such as ketoconazole are effective and can be used for long periods of time with minimal risk of adverse effects3-5 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C).

Our patient had used nystatin cream, which is effective against Candida yeast infections, but not especially effective for Malassezia sp.6

To reduce inflammation, mild topical steroids such as hydrocortisone cream 2.5% should be used. However, they must be used for short periods to avoid atrophy, telangiectasias, and steroid-induced acne. An alternative evolving treatment is to use a calcineurin inhibitor, such as pimecrolimus cream 1% or tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. These drugs do not exacerbate hypopigmentation, an effect that sometimes is attributed to topical steroids.7

Scalp treatments include shampoos such as ketoconazole 2%, selenium sulfide 2.5%, and ciclopirox 1%.3 Shampoos should be lathered up and left on the scalp for 3 to 5 minutes before rinsing.

Two forms of ketoconazole for our patient

Our patient responded well to ketoconazole cream 2% applied twice daily to the face and other areas without hair and ketoconazole 2% shampoo twice weekly. At a 6-week follow-up, the patient had significant improvement in scaling and pruritus on the central face and scalp. The associated facial hypopigmentation faded over 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Nakabayashi A, Sei Y, Guillot J. Identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor and normal subjects. Med Mycology. 2000;38:337-341.

2. Sampaio AL, Mameri AC, Vargas TJ, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1061-1071;quiz 1072-1074.

3. Naldi L. Seborrhoeic dermatitis. Clin Evid (Online). 2010;2010:pii:1713.

4. Draelos ZD, Feldman SR, Butners V, et al. Long-term safety of ketoconazole foam, 2% in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: results of a phase IV, open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:e1-e6.

5. Apasrawirote W, Udompataikul M, Rattanamongkolgul S. Topical antifungal agents for seborrheic dermatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:756-760.

6. Pedrosa AF, Lisboa, C, Rodrigues AG. Malassezia infections: A medical conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb 22. Epub ahead of print.

7. High WA, Pandya AG. Pilot trial of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in African American adults with associated hypopigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1083-1088.

1. Nakabayashi A, Sei Y, Guillot J. Identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor and normal subjects. Med Mycology. 2000;38:337-341.

2. Sampaio AL, Mameri AC, Vargas TJ, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1061-1071;quiz 1072-1074.

3. Naldi L. Seborrhoeic dermatitis. Clin Evid (Online). 2010;2010:pii:1713.

4. Draelos ZD, Feldman SR, Butners V, et al. Long-term safety of ketoconazole foam, 2% in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: results of a phase IV, open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:e1-e6.

5. Apasrawirote W, Udompataikul M, Rattanamongkolgul S. Topical antifungal agents for seborrheic dermatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:756-760.

6. Pedrosa AF, Lisboa, C, Rodrigues AG. Malassezia infections: A medical conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb 22. Epub ahead of print.

7. High WA, Pandya AG. Pilot trial of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in African American adults with associated hypopigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1083-1088.

Mouth pain

The FP suspected that this might be a case of pemphigus vulgaris and called a colleague who had additional fellowship training in dermatology. The colleague performed a shave biopsy on a skin lesion at the edge of a previous blister on the breast. He sent the blister edge for standard pathology and the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence. He also started the patient on prednisone 60 mg/day and gave her dexamethasone mouth solution.

He encouraged her to drink plenty of fluids and 2 days later, at a follow-up appointment, the patient was feeling better and able to eat some solid foods. The pathology reports confirmed pemphigus vulgaris and long-term management was initiated. The black coating of the tongue was secondary to poor oral hygiene related to the disease and the patient’s inability to brush her teeth while suffering from painful oral ulcers.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Black hairy tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:226-231.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP suspected that this might be a case of pemphigus vulgaris and called a colleague who had additional fellowship training in dermatology. The colleague performed a shave biopsy on a skin lesion at the edge of a previous blister on the breast. He sent the blister edge for standard pathology and the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence. He also started the patient on prednisone 60 mg/day and gave her dexamethasone mouth solution.

He encouraged her to drink plenty of fluids and 2 days later, at a follow-up appointment, the patient was feeling better and able to eat some solid foods. The pathology reports confirmed pemphigus vulgaris and long-term management was initiated. The black coating of the tongue was secondary to poor oral hygiene related to the disease and the patient’s inability to brush her teeth while suffering from painful oral ulcers.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Black hairy tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:226-231.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP suspected that this might be a case of pemphigus vulgaris and called a colleague who had additional fellowship training in dermatology. The colleague performed a shave biopsy on a skin lesion at the edge of a previous blister on the breast. He sent the blister edge for standard pathology and the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence. He also started the patient on prednisone 60 mg/day and gave her dexamethasone mouth solution.

He encouraged her to drink plenty of fluids and 2 days later, at a follow-up appointment, the patient was feeling better and able to eat some solid foods. The pathology reports confirmed pemphigus vulgaris and long-term management was initiated. The black coating of the tongue was secondary to poor oral hygiene related to the disease and the patient’s inability to brush her teeth while suffering from painful oral ulcers.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Black hairy tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:226-231.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Discoloration of the tongue

This patient had a black hairy tongue (BHT), poor oral hygiene, and tobacco and alcohol addiction. BHT is a benign disorder of the tongue characterized by abnormally hypertrophied and elongated filiform papillae on the surface of the tongue. In addition, there is defective desquamation of the papillae on the dorsal tongue, resulting in a hair-like appearance. These papillae, which are normally about 1 mm in length, may become as long as 12 mm. The elongated filiform papillae can then collect debris, bacteria, fungus, or other foreign materials.

In a literature review of reported cases of drug-induced BHT, 82% were caused by antibiotics. Dry mouth (xerostomia) from medications, tobacco, and radiation therapy can also lead to BHT. Patients may be asymptomatic. However, the accumulation of debris in the elongated papillae may cause taste alterations, nausea, gagging, halitosis, and pain or burning of the tongue.

The diagnosis is made by visual inspection. Patients with BHT have a black, brown, or yellow discoloration of their tongue, depending on foods ingested, tobacco use, and the amount of coffee or tea consumed. In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid predisposing risk factors (eg, tobacco, alcohol). She also recommended regular tongue brushing (using a soft toothbrush or tongue scraper) and an appointment with a dentist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Black hairy tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:226-231.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

This patient had a black hairy tongue (BHT), poor oral hygiene, and tobacco and alcohol addiction. BHT is a benign disorder of the tongue characterized by abnormally hypertrophied and elongated filiform papillae on the surface of the tongue. In addition, there is defective desquamation of the papillae on the dorsal tongue, resulting in a hair-like appearance. These papillae, which are normally about 1 mm in length, may become as long as 12 mm. The elongated filiform papillae can then collect debris, bacteria, fungus, or other foreign materials.

In a literature review of reported cases of drug-induced BHT, 82% were caused by antibiotics. Dry mouth (xerostomia) from medications, tobacco, and radiation therapy can also lead to BHT. Patients may be asymptomatic. However, the accumulation of debris in the elongated papillae may cause taste alterations, nausea, gagging, halitosis, and pain or burning of the tongue.

The diagnosis is made by visual inspection. Patients with BHT have a black, brown, or yellow discoloration of their tongue, depending on foods ingested, tobacco use, and the amount of coffee or tea consumed. In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid predisposing risk factors (eg, tobacco, alcohol). She also recommended regular tongue brushing (using a soft toothbrush or tongue scraper) and an appointment with a dentist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Black hairy tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:226-231.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

This patient had a black hairy tongue (BHT), poor oral hygiene, and tobacco and alcohol addiction. BHT is a benign disorder of the tongue characterized by abnormally hypertrophied and elongated filiform papillae on the surface of the tongue. In addition, there is defective desquamation of the papillae on the dorsal tongue, resulting in a hair-like appearance. These papillae, which are normally about 1 mm in length, may become as long as 12 mm. The elongated filiform papillae can then collect debris, bacteria, fungus, or other foreign materials.

In a literature review of reported cases of drug-induced BHT, 82% were caused by antibiotics. Dry mouth (xerostomia) from medications, tobacco, and radiation therapy can also lead to BHT. Patients may be asymptomatic. However, the accumulation of debris in the elongated papillae may cause taste alterations, nausea, gagging, halitosis, and pain or burning of the tongue.

The diagnosis is made by visual inspection. Patients with BHT have a black, brown, or yellow discoloration of their tongue, depending on foods ingested, tobacco use, and the amount of coffee or tea consumed. In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid predisposing risk factors (eg, tobacco, alcohol). She also recommended regular tongue brushing (using a soft toothbrush or tongue scraper) and an appointment with a dentist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Gonsalves W. Black hairy tongue. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:226-231.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Difficulty swallowing

The FP suspected that the patient had squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and referred him to Otolaryngology for a biopsy and workup. SCC accounts for 95% of laryngeal cancer cases. Approximately 11,000 new cases of laryngeal cancer are diagnosed in the United States each year. Peak incidence of laryngeal cancer is in the sixth and seventh decades of life with a strong male predominance.

SCC has a multifactorial etiology, but 90% of patients have a history of heavy tobacco and/or alcohol use. These risk factors have a synergistic effect. Other independent risk factors include employment as a painter or metalworker, exposure to diesel or gasoline fumes, and exposure to therapeutic doses of radiation.

The patient’s biopsy confirmed SCC of the larynx. Fortunately, the metastatic workup was negative and the patient underwent a laryngectomy.

Photo courtesy of Blake Simpson, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Matrka L, Simpson CB, King JM. The larynx (hoarseness). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:220-226.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP suspected that the patient had squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and referred him to Otolaryngology for a biopsy and workup. SCC accounts for 95% of laryngeal cancer cases. Approximately 11,000 new cases of laryngeal cancer are diagnosed in the United States each year. Peak incidence of laryngeal cancer is in the sixth and seventh decades of life with a strong male predominance.

SCC has a multifactorial etiology, but 90% of patients have a history of heavy tobacco and/or alcohol use. These risk factors have a synergistic effect. Other independent risk factors include employment as a painter or metalworker, exposure to diesel or gasoline fumes, and exposure to therapeutic doses of radiation.

The patient’s biopsy confirmed SCC of the larynx. Fortunately, the metastatic workup was negative and the patient underwent a laryngectomy.

Photo courtesy of Blake Simpson, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Matrka L, Simpson CB, King JM. The larynx (hoarseness). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:220-226.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP suspected that the patient had squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and referred him to Otolaryngology for a biopsy and workup. SCC accounts for 95% of laryngeal cancer cases. Approximately 11,000 new cases of laryngeal cancer are diagnosed in the United States each year. Peak incidence of laryngeal cancer is in the sixth and seventh decades of life with a strong male predominance.

SCC has a multifactorial etiology, but 90% of patients have a history of heavy tobacco and/or alcohol use. These risk factors have a synergistic effect. Other independent risk factors include employment as a painter or metalworker, exposure to diesel or gasoline fumes, and exposure to therapeutic doses of radiation.

The patient’s biopsy confirmed SCC of the larynx. Fortunately, the metastatic workup was negative and the patient underwent a laryngectomy.

Photo courtesy of Blake Simpson, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Matrka L, Simpson CB, King JM. The larynx (hoarseness). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:220-226.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/