User login

Hand pain

The family physician (FP) recognized that this patient was having an attack of gout, which was most likely exacerbated by the new prescription for hydrochlorothiazide. The patient’s serum uric acid level was highly elevated (12.1 mg/dL). No joint aspiration was attempted because the diagnosis was well supported by the history, physical exam, and elevated serum uric acid level.

Crystalline arthritis is caused by the deposition of uric acid crystals (gout) or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals (calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease) resulting in episodic flares with periods of remission.

Treatment for acute cases of gout include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or colchicine. The treatment of chronic gout includes modifications to diet and existing medications and the lowering of urate levels. Patients are encouraged to:

- reduce the intake of purine-rich foods (eg, organ meats, red meats, and seafood)

- increase fluid intake to 2000 mL/d

- lower alcohol intake

- consume dairy products as these may be protective against gout

- change medications. Specifically, discontinue aspirin and consider stopping a thiazide diuretic. Lower urate levels with xanthine oxidase inhibitors (eg, allopurinol), uricosuric agents (eg, probenecid), or uricase agents (eg, pegloticase).

In this case, the FP replaced the thiazide diuretic with a calcium channel blocker. The patient was treated with colchicine to stop the acute inflammation. He was also told to drink less alcohol (or abstain from it) and to avoid red meat in his diet.

Photo courtesy of Robin Treadwell, MD and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized that this patient was having an attack of gout, which was most likely exacerbated by the new prescription for hydrochlorothiazide. The patient’s serum uric acid level was highly elevated (12.1 mg/dL). No joint aspiration was attempted because the diagnosis was well supported by the history, physical exam, and elevated serum uric acid level.

Crystalline arthritis is caused by the deposition of uric acid crystals (gout) or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals (calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease) resulting in episodic flares with periods of remission.

Treatment for acute cases of gout include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or colchicine. The treatment of chronic gout includes modifications to diet and existing medications and the lowering of urate levels. Patients are encouraged to:

- reduce the intake of purine-rich foods (eg, organ meats, red meats, and seafood)

- increase fluid intake to 2000 mL/d

- lower alcohol intake

- consume dairy products as these may be protective against gout

- change medications. Specifically, discontinue aspirin and consider stopping a thiazide diuretic. Lower urate levels with xanthine oxidase inhibitors (eg, allopurinol), uricosuric agents (eg, probenecid), or uricase agents (eg, pegloticase).

In this case, the FP replaced the thiazide diuretic with a calcium channel blocker. The patient was treated with colchicine to stop the acute inflammation. He was also told to drink less alcohol (or abstain from it) and to avoid red meat in his diet.

Photo courtesy of Robin Treadwell, MD and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized that this patient was having an attack of gout, which was most likely exacerbated by the new prescription for hydrochlorothiazide. The patient’s serum uric acid level was highly elevated (12.1 mg/dL). No joint aspiration was attempted because the diagnosis was well supported by the history, physical exam, and elevated serum uric acid level.

Crystalline arthritis is caused by the deposition of uric acid crystals (gout) or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals (calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease) resulting in episodic flares with periods of remission.

Treatment for acute cases of gout include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or colchicine. The treatment of chronic gout includes modifications to diet and existing medications and the lowering of urate levels. Patients are encouraged to:

- reduce the intake of purine-rich foods (eg, organ meats, red meats, and seafood)

- increase fluid intake to 2000 mL/d

- lower alcohol intake

- consume dairy products as these may be protective against gout

- change medications. Specifically, discontinue aspirin and consider stopping a thiazide diuretic. Lower urate levels with xanthine oxidase inhibitors (eg, allopurinol), uricosuric agents (eg, probenecid), or uricase agents (eg, pegloticase).

In this case, the FP replaced the thiazide diuretic with a calcium channel blocker. The patient was treated with colchicine to stop the acute inflammation. He was also told to drink less alcohol (or abstain from it) and to avoid red meat in his diet.

Photo courtesy of Robin Treadwell, MD and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

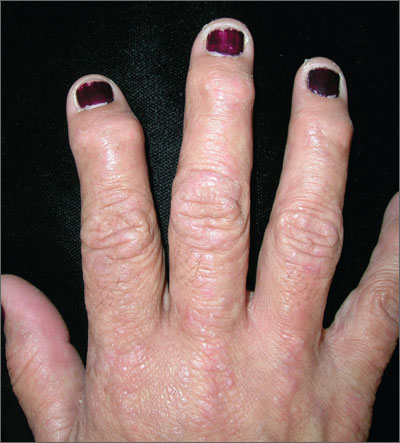

Finger pain and swelling

The FP diagnosed psoriatic arthritis (with dactylitis and significant distal interphalangeal joint [DIP] involvement) in this patient. Both of the patient’s hands were involved, but his left hand was worse. The condition of the patient’s nails was not surprising, given that almost all patients with psoriatic arthritis have nail involvement.

Radiographs of the patient’s hands showed periarticular erosions and new bone formation. There was also telescoping of the third DIP joint.

Treatment choices for psoriatic arthritis include methotrexate and the new biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α medications.

This patient was referred to a rheumatologist. Methotrexate treatment was avoided because of the liver toxicity issue in a patient with active hepatitis C. The rheumatologist started him on the biologic adalimumab with injections every 2 weeks (not contraindicated with hepatitis C).

Photo courtesy of Ricardo Zuniga-Montes, MD and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed psoriatic arthritis (with dactylitis and significant distal interphalangeal joint [DIP] involvement) in this patient. Both of the patient’s hands were involved, but his left hand was worse. The condition of the patient’s nails was not surprising, given that almost all patients with psoriatic arthritis have nail involvement.

Radiographs of the patient’s hands showed periarticular erosions and new bone formation. There was also telescoping of the third DIP joint.

Treatment choices for psoriatic arthritis include methotrexate and the new biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α medications.

This patient was referred to a rheumatologist. Methotrexate treatment was avoided because of the liver toxicity issue in a patient with active hepatitis C. The rheumatologist started him on the biologic adalimumab with injections every 2 weeks (not contraindicated with hepatitis C).

Photo courtesy of Ricardo Zuniga-Montes, MD and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed psoriatic arthritis (with dactylitis and significant distal interphalangeal joint [DIP] involvement) in this patient. Both of the patient’s hands were involved, but his left hand was worse. The condition of the patient’s nails was not surprising, given that almost all patients with psoriatic arthritis have nail involvement.

Radiographs of the patient’s hands showed periarticular erosions and new bone formation. There was also telescoping of the third DIP joint.

Treatment choices for psoriatic arthritis include methotrexate and the new biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α medications.

This patient was referred to a rheumatologist. Methotrexate treatment was avoided because of the liver toxicity issue in a patient with active hepatitis C. The rheumatologist started him on the biologic adalimumab with injections every 2 weeks (not contraindicated with hepatitis C).

Photo courtesy of Ricardo Zuniga-Montes, MD and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Nodules on nose and tattoos

A 38-year-old African American man with no significant medical history presented to our dermatology clinic with a 5-month history of nodules on the right side of his nose (FIGURE 1). For several years, he’d also had nodules that gradually appeared on several red-inked tattoos shortly after he received each tattoo (FIGURE 2). He also had a 5-year history of nontender swelling of his fingers.

The patient denied any trauma to the areas with nodules or being in contact with anyone who was sick. He had no respiratory complaints, but chest x-rays from recent and past records showed stable bilateral intrathoracic lymphadenopathy without any lobar infiltration or pleural effusion.

Physical examination revealed 3 reddish-brown soft nodules on the nasal ala and multiple, nontender, 3- to 5-mm firm nodules located in the red-inked areas of tattoos on his arms and neck. The tattoo nodules were asymptomatic and stable in size. He had clubbing of multiple digits and nail dystrophy. His distal fingers were edematous, but nontender. X-rays revealed lytic, lace-like lucencies of the middle and distal phalanges and erosions of the distal phalanges on both hands (FIGURE 3).

We biopsied the nodules on his nose and on one of his tattoos.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sarcoidosis

Based on his clinical presentation and skin biopsy results, the patient was given a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. A biopsy from the right side of his nose demonstrated sarcoidal granulomas. Acid-fast bacilli and periodic acid-Schiff stains were negative. A biopsy of one of the tattoo nodules showed sarcoidal granulomas, and close inspection revealed red tattoo pigment within the granulomatous inflammation.

X-rays showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, which was consistent with pulmonary sarcoidosis, and the lace-like appearance of the middle and distal phalanges was consistent with skeletal sarcoidosis.

Systemic sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, granulomatous disease that affects multiple organ systems but primarily the lungs and lymphatic system.1 The estimated prevalence of systemic sarcoidosis ranges from less than 1 to 40 cases per 100,000 people, and the condition is more common among African Americans.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis can occur as a manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis. It occurs in 20% to 35% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis2 and may present as asymptomatic red or skin-colored papules and firm nodules within tattoos, old scars, or permanent makeup. Cutaneous sarcoidosis in tattoos may be the first manifestation of sarcoidosis, and the time between acquiring the tattoo and developing sarcoidal nodules varies widely.

It is not clear why sarcoidal granulomas occur in tattoos. One possibility is that chronic low-grade exposure of the immune system to foreign materials such as tattoo ink leads to granulomatous hypersensitivity.2,3 Sarcoidosis usually occurs in red (cinnabar), black (ferric oxide), or blue-black areas of tattoos,4 in which the pigment acts as a nidus for granuloma formation.

A skin biopsy is helpful in making a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. The histopathology shows noncaseating epithelioid granulomas.

Because skin manifestations may be the first and only sign of systemic sarcoidosis, patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis should be evaluated for systemic disease. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been associated with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, pulmonary sarcoidosis, uveitis, arthritis, and dactylitis.3

Foreign-body reactions, syphilis are part of the differential Dx

Nonsarcoidal tattoo granulomas are a foreignbody reaction to the pigment used in tattooing and are characterized by lesions occurring only at the site of tattoos. This type of granulomatous reaction is most commonly seen in redpigmented tattoos, but can be seen in other tattoo colors as well. Macrophages containing pigment and “naked” granulomas are seen on histology.

Atypical mycobacterial skin infection can occur in tattoos that were created with contaminated ink or ink diluted with nonsterile water.5 Mycobacterial species such as Mycobacterium chelonae have been isolated from skin biopsies taken from the margins of new tattoos that developed a persistent erythematous eruption.5

Granuloma annulare is characterized by red or skin-colored plaques in annular and rope-like patterns with central clearing and nonscaly borders. A localized variant is frequently found on the extremities.6 There are associations between granuloma annulare, diabetes mellitus, and internal malignancy.7

Secondary syphilis classically presents with symmetric macules or papules distributed on the trunk and extremities. However, cutaneous manifestations vary widely. Lesions involving the palms and soles are important clues to a syphilis diagnosis, and patients often have malaise and fever.

Treatment includes topical, intralesional corticosteroids

The evidence for the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis is largely drawn from uncontrolled case series; there have been few double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.8 The first-line treatment for limited papules is a high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied twice weekly) and an intralesional corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone, one 5-10 mg/mL injection every 4 weeks).8

Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice a day for at least 6 months) or methotrexate (10-15 mg/week taken at once orally or as a subcutaneous or intramuscular injection) can also be helpful. Treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream twice a day and doxycycline hyclate (100 mg twice a day for 4 months) has been reported to clear cutaneous lesions in tattoos.3

Oral corticosteroids are the gold standard for severe cutaneous sarcoidosis, but their multiple adverse effects, such as diabetes and adrenal suppression, may prevent prolonged use.8 For most cutaneous lesions, intralesional corticosteroids and/or hydroxychloroquine followed by methotrexate can be effective.8

The nodules on our patient’s nose were successfully treated with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL. No treatment was initiated for the tattoo nodules because they were asymptomatic and the patient was not concerned about their appearance. He continues to get new tattoos, but is minimizing the use of red ink.

The patient was also started on prednisone 10 mg/d, which improved his hand swelling. Rheumatologists were considering a steroidsparing immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jinmeng Zhang, MD, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; [email protected]

1. American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society, the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.

2. Guerra JR, Alderuccio JP, Sandhu J, et al. Granulomatous tattoo reaction in a young man. Lancet. 2013;382:284.

3. Antonovich DD, Callen JP. Development of sarcoidosis in cosmetic tattoos. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:869-872.

4. Baumgartner M, Feldmann R, Breier F, et al. Sarcoidal granulomas in a cosmetic tattoo in association with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:900-902.

5. Kennedy BS, Bedard B, Younge M, et al. Outbreak of Mycobacterium

chelonae infection associated with tattoo ink. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1020-1024.

6. Hsu S, Lehner AC, Chang JR. Granuloma annulare localized to the palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:287-288.

7. Thornsberry LA, English JC 3rd. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

8. Lodha S, Sanchez M, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis of the skin: a review for the pulmonologist. Chest. 2009;136:583-596.

A 38-year-old African American man with no significant medical history presented to our dermatology clinic with a 5-month history of nodules on the right side of his nose (FIGURE 1). For several years, he’d also had nodules that gradually appeared on several red-inked tattoos shortly after he received each tattoo (FIGURE 2). He also had a 5-year history of nontender swelling of his fingers.

The patient denied any trauma to the areas with nodules or being in contact with anyone who was sick. He had no respiratory complaints, but chest x-rays from recent and past records showed stable bilateral intrathoracic lymphadenopathy without any lobar infiltration or pleural effusion.

Physical examination revealed 3 reddish-brown soft nodules on the nasal ala and multiple, nontender, 3- to 5-mm firm nodules located in the red-inked areas of tattoos on his arms and neck. The tattoo nodules were asymptomatic and stable in size. He had clubbing of multiple digits and nail dystrophy. His distal fingers were edematous, but nontender. X-rays revealed lytic, lace-like lucencies of the middle and distal phalanges and erosions of the distal phalanges on both hands (FIGURE 3).

We biopsied the nodules on his nose and on one of his tattoos.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sarcoidosis

Based on his clinical presentation and skin biopsy results, the patient was given a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. A biopsy from the right side of his nose demonstrated sarcoidal granulomas. Acid-fast bacilli and periodic acid-Schiff stains were negative. A biopsy of one of the tattoo nodules showed sarcoidal granulomas, and close inspection revealed red tattoo pigment within the granulomatous inflammation.

X-rays showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, which was consistent with pulmonary sarcoidosis, and the lace-like appearance of the middle and distal phalanges was consistent with skeletal sarcoidosis.

Systemic sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, granulomatous disease that affects multiple organ systems but primarily the lungs and lymphatic system.1 The estimated prevalence of systemic sarcoidosis ranges from less than 1 to 40 cases per 100,000 people, and the condition is more common among African Americans.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis can occur as a manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis. It occurs in 20% to 35% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis2 and may present as asymptomatic red or skin-colored papules and firm nodules within tattoos, old scars, or permanent makeup. Cutaneous sarcoidosis in tattoos may be the first manifestation of sarcoidosis, and the time between acquiring the tattoo and developing sarcoidal nodules varies widely.

It is not clear why sarcoidal granulomas occur in tattoos. One possibility is that chronic low-grade exposure of the immune system to foreign materials such as tattoo ink leads to granulomatous hypersensitivity.2,3 Sarcoidosis usually occurs in red (cinnabar), black (ferric oxide), or blue-black areas of tattoos,4 in which the pigment acts as a nidus for granuloma formation.

A skin biopsy is helpful in making a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. The histopathology shows noncaseating epithelioid granulomas.

Because skin manifestations may be the first and only sign of systemic sarcoidosis, patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis should be evaluated for systemic disease. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been associated with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, pulmonary sarcoidosis, uveitis, arthritis, and dactylitis.3

Foreign-body reactions, syphilis are part of the differential Dx

Nonsarcoidal tattoo granulomas are a foreignbody reaction to the pigment used in tattooing and are characterized by lesions occurring only at the site of tattoos. This type of granulomatous reaction is most commonly seen in redpigmented tattoos, but can be seen in other tattoo colors as well. Macrophages containing pigment and “naked” granulomas are seen on histology.

Atypical mycobacterial skin infection can occur in tattoos that were created with contaminated ink or ink diluted with nonsterile water.5 Mycobacterial species such as Mycobacterium chelonae have been isolated from skin biopsies taken from the margins of new tattoos that developed a persistent erythematous eruption.5

Granuloma annulare is characterized by red or skin-colored plaques in annular and rope-like patterns with central clearing and nonscaly borders. A localized variant is frequently found on the extremities.6 There are associations between granuloma annulare, diabetes mellitus, and internal malignancy.7

Secondary syphilis classically presents with symmetric macules or papules distributed on the trunk and extremities. However, cutaneous manifestations vary widely. Lesions involving the palms and soles are important clues to a syphilis diagnosis, and patients often have malaise and fever.

Treatment includes topical, intralesional corticosteroids

The evidence for the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis is largely drawn from uncontrolled case series; there have been few double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.8 The first-line treatment for limited papules is a high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied twice weekly) and an intralesional corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone, one 5-10 mg/mL injection every 4 weeks).8

Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice a day for at least 6 months) or methotrexate (10-15 mg/week taken at once orally or as a subcutaneous or intramuscular injection) can also be helpful. Treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream twice a day and doxycycline hyclate (100 mg twice a day for 4 months) has been reported to clear cutaneous lesions in tattoos.3

Oral corticosteroids are the gold standard for severe cutaneous sarcoidosis, but their multiple adverse effects, such as diabetes and adrenal suppression, may prevent prolonged use.8 For most cutaneous lesions, intralesional corticosteroids and/or hydroxychloroquine followed by methotrexate can be effective.8

The nodules on our patient’s nose were successfully treated with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL. No treatment was initiated for the tattoo nodules because they were asymptomatic and the patient was not concerned about their appearance. He continues to get new tattoos, but is minimizing the use of red ink.

The patient was also started on prednisone 10 mg/d, which improved his hand swelling. Rheumatologists were considering a steroidsparing immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jinmeng Zhang, MD, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; [email protected]

A 38-year-old African American man with no significant medical history presented to our dermatology clinic with a 5-month history of nodules on the right side of his nose (FIGURE 1). For several years, he’d also had nodules that gradually appeared on several red-inked tattoos shortly after he received each tattoo (FIGURE 2). He also had a 5-year history of nontender swelling of his fingers.

The patient denied any trauma to the areas with nodules or being in contact with anyone who was sick. He had no respiratory complaints, but chest x-rays from recent and past records showed stable bilateral intrathoracic lymphadenopathy without any lobar infiltration or pleural effusion.

Physical examination revealed 3 reddish-brown soft nodules on the nasal ala and multiple, nontender, 3- to 5-mm firm nodules located in the red-inked areas of tattoos on his arms and neck. The tattoo nodules were asymptomatic and stable in size. He had clubbing of multiple digits and nail dystrophy. His distal fingers were edematous, but nontender. X-rays revealed lytic, lace-like lucencies of the middle and distal phalanges and erosions of the distal phalanges on both hands (FIGURE 3).

We biopsied the nodules on his nose and on one of his tattoos.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sarcoidosis

Based on his clinical presentation and skin biopsy results, the patient was given a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. A biopsy from the right side of his nose demonstrated sarcoidal granulomas. Acid-fast bacilli and periodic acid-Schiff stains were negative. A biopsy of one of the tattoo nodules showed sarcoidal granulomas, and close inspection revealed red tattoo pigment within the granulomatous inflammation.

X-rays showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, which was consistent with pulmonary sarcoidosis, and the lace-like appearance of the middle and distal phalanges was consistent with skeletal sarcoidosis.

Systemic sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, granulomatous disease that affects multiple organ systems but primarily the lungs and lymphatic system.1 The estimated prevalence of systemic sarcoidosis ranges from less than 1 to 40 cases per 100,000 people, and the condition is more common among African Americans.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis can occur as a manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis. It occurs in 20% to 35% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis2 and may present as asymptomatic red or skin-colored papules and firm nodules within tattoos, old scars, or permanent makeup. Cutaneous sarcoidosis in tattoos may be the first manifestation of sarcoidosis, and the time between acquiring the tattoo and developing sarcoidal nodules varies widely.

It is not clear why sarcoidal granulomas occur in tattoos. One possibility is that chronic low-grade exposure of the immune system to foreign materials such as tattoo ink leads to granulomatous hypersensitivity.2,3 Sarcoidosis usually occurs in red (cinnabar), black (ferric oxide), or blue-black areas of tattoos,4 in which the pigment acts as a nidus for granuloma formation.

A skin biopsy is helpful in making a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. The histopathology shows noncaseating epithelioid granulomas.

Because skin manifestations may be the first and only sign of systemic sarcoidosis, patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis should be evaluated for systemic disease. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been associated with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, pulmonary sarcoidosis, uveitis, arthritis, and dactylitis.3

Foreign-body reactions, syphilis are part of the differential Dx

Nonsarcoidal tattoo granulomas are a foreignbody reaction to the pigment used in tattooing and are characterized by lesions occurring only at the site of tattoos. This type of granulomatous reaction is most commonly seen in redpigmented tattoos, but can be seen in other tattoo colors as well. Macrophages containing pigment and “naked” granulomas are seen on histology.

Atypical mycobacterial skin infection can occur in tattoos that were created with contaminated ink or ink diluted with nonsterile water.5 Mycobacterial species such as Mycobacterium chelonae have been isolated from skin biopsies taken from the margins of new tattoos that developed a persistent erythematous eruption.5

Granuloma annulare is characterized by red or skin-colored plaques in annular and rope-like patterns with central clearing and nonscaly borders. A localized variant is frequently found on the extremities.6 There are associations between granuloma annulare, diabetes mellitus, and internal malignancy.7

Secondary syphilis classically presents with symmetric macules or papules distributed on the trunk and extremities. However, cutaneous manifestations vary widely. Lesions involving the palms and soles are important clues to a syphilis diagnosis, and patients often have malaise and fever.

Treatment includes topical, intralesional corticosteroids

The evidence for the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis is largely drawn from uncontrolled case series; there have been few double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.8 The first-line treatment for limited papules is a high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied twice weekly) and an intralesional corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone, one 5-10 mg/mL injection every 4 weeks).8

Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice a day for at least 6 months) or methotrexate (10-15 mg/week taken at once orally or as a subcutaneous or intramuscular injection) can also be helpful. Treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream twice a day and doxycycline hyclate (100 mg twice a day for 4 months) has been reported to clear cutaneous lesions in tattoos.3

Oral corticosteroids are the gold standard for severe cutaneous sarcoidosis, but their multiple adverse effects, such as diabetes and adrenal suppression, may prevent prolonged use.8 For most cutaneous lesions, intralesional corticosteroids and/or hydroxychloroquine followed by methotrexate can be effective.8

The nodules on our patient’s nose were successfully treated with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL. No treatment was initiated for the tattoo nodules because they were asymptomatic and the patient was not concerned about their appearance. He continues to get new tattoos, but is minimizing the use of red ink.

The patient was also started on prednisone 10 mg/d, which improved his hand swelling. Rheumatologists were considering a steroidsparing immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jinmeng Zhang, MD, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; [email protected]

1. American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society, the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.

2. Guerra JR, Alderuccio JP, Sandhu J, et al. Granulomatous tattoo reaction in a young man. Lancet. 2013;382:284.

3. Antonovich DD, Callen JP. Development of sarcoidosis in cosmetic tattoos. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:869-872.

4. Baumgartner M, Feldmann R, Breier F, et al. Sarcoidal granulomas in a cosmetic tattoo in association with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:900-902.

5. Kennedy BS, Bedard B, Younge M, et al. Outbreak of Mycobacterium

chelonae infection associated with tattoo ink. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1020-1024.

6. Hsu S, Lehner AC, Chang JR. Granuloma annulare localized to the palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:287-288.

7. Thornsberry LA, English JC 3rd. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

8. Lodha S, Sanchez M, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis of the skin: a review for the pulmonologist. Chest. 2009;136:583-596.

1. American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society, the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.

2. Guerra JR, Alderuccio JP, Sandhu J, et al. Granulomatous tattoo reaction in a young man. Lancet. 2013;382:284.

3. Antonovich DD, Callen JP. Development of sarcoidosis in cosmetic tattoos. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:869-872.

4. Baumgartner M, Feldmann R, Breier F, et al. Sarcoidal granulomas in a cosmetic tattoo in association with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:900-902.

5. Kennedy BS, Bedard B, Younge M, et al. Outbreak of Mycobacterium

chelonae infection associated with tattoo ink. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1020-1024.

6. Hsu S, Lehner AC, Chang JR. Granuloma annulare localized to the palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:287-288.

7. Thornsberry LA, English JC 3rd. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

8. Lodha S, Sanchez M, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis of the skin: a review for the pulmonologist. Chest. 2009;136:583-596.

Crooked fingers

The FP made the clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) based on the patient’s bilateral MCP joint swelling, ulnar deviation, and morning stiffness.

Patients with RA initially experience swelling and stiffness in their wrists, as well as their MCP and metatarsophalangeal joints. Later, the larger joints are affected. When RA is advanced, severe destruction and subluxation occur.

Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in identifying early RA changes, such as synovitis, effusions, and bone marrow changes. Later on, x-rays will reveal joint erosions and loss of joint space.

To treat the patient’s pain and inflammation, the FP prescribed a COX-2 inhibitor (along with a proton pump inhibitor to protect the stomach). The FP also referred her to a rheumatologist for further work-up and to determine whether a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug was in order.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) based on the patient’s bilateral MCP joint swelling, ulnar deviation, and morning stiffness.

Patients with RA initially experience swelling and stiffness in their wrists, as well as their MCP and metatarsophalangeal joints. Later, the larger joints are affected. When RA is advanced, severe destruction and subluxation occur.

Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in identifying early RA changes, such as synovitis, effusions, and bone marrow changes. Later on, x-rays will reveal joint erosions and loss of joint space.

To treat the patient’s pain and inflammation, the FP prescribed a COX-2 inhibitor (along with a proton pump inhibitor to protect the stomach). The FP also referred her to a rheumatologist for further work-up and to determine whether a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug was in order.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) based on the patient’s bilateral MCP joint swelling, ulnar deviation, and morning stiffness.

Patients with RA initially experience swelling and stiffness in their wrists, as well as their MCP and metatarsophalangeal joints. Later, the larger joints are affected. When RA is advanced, severe destruction and subluxation occur.

Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in identifying early RA changes, such as synovitis, effusions, and bone marrow changes. Later on, x-rays will reveal joint erosions and loss of joint space.

To treat the patient’s pain and inflammation, the FP prescribed a COX-2 inhibitor (along with a proton pump inhibitor to protect the stomach). The FP also referred her to a rheumatologist for further work-up and to determine whether a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug was in order.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Left knee pain

The FP suspected osteoarthritis (OA) was causing the knee effusion. Radiography wasn’t available and a decision was made to do a joint aspiration and steroid injection (if there were no signs of infection). The skin was anesthetized at the site of the aspiration and straw-colored fluid was removed; there were no signs of infection.

The FP injected triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg into the knee. The patient received considerable symptomatic relief from the aspiration and within days of her visit, the intra-articular steroid provided further relief.

A subsequent x-ray confirmed the FP’s suspicions and showed early signs of OA. At follow-up, the FP provided further education on the treatment of OA.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected osteoarthritis (OA) was causing the knee effusion. Radiography wasn’t available and a decision was made to do a joint aspiration and steroid injection (if there were no signs of infection). The skin was anesthetized at the site of the aspiration and straw-colored fluid was removed; there were no signs of infection.

The FP injected triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg into the knee. The patient received considerable symptomatic relief from the aspiration and within days of her visit, the intra-articular steroid provided further relief.

A subsequent x-ray confirmed the FP’s suspicions and showed early signs of OA. At follow-up, the FP provided further education on the treatment of OA.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected osteoarthritis (OA) was causing the knee effusion. Radiography wasn’t available and a decision was made to do a joint aspiration and steroid injection (if there were no signs of infection). The skin was anesthetized at the site of the aspiration and straw-colored fluid was removed; there were no signs of infection.

The FP injected triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg into the knee. The patient received considerable symptomatic relief from the aspiration and within days of her visit, the intra-articular steroid provided further relief.

A subsequent x-ray confirmed the FP’s suspicions and showed early signs of OA. At follow-up, the FP provided further education on the treatment of OA.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Hand pain

The FP diagnosed osteoarthritis (OA) after noting Heberden’s nodes and Bouchard’s nodes at the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints, respectively.

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States. Twenty-one million adults have functional limitations because of arthritis. Fifty percent of adults ages 65 years or older have been given an arthritis diagnosis. The most commonly affected joints are the knees, hips, hands (distal and proximal interphalangeal joints), and spine. If the diagnosis is uncertain, plain x-rays can often differentiate between OA and other forms of arthritis.

Treatment for OA centers around pain relief and includes acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Since there is no real inflammation, anti-inflammatory medications have no proven advantage over analgesics such as acetaminophen. The FP suggested acetaminophen at a dose not to exceed 4 g/d. The FP also suggested that the patient exercise, as well as use over-the-counter NSAIDs in addition to acetaminophen intermittently if the acetaminophen failed to provide sufficient pain relief.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed osteoarthritis (OA) after noting Heberden’s nodes and Bouchard’s nodes at the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints, respectively.

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States. Twenty-one million adults have functional limitations because of arthritis. Fifty percent of adults ages 65 years or older have been given an arthritis diagnosis. The most commonly affected joints are the knees, hips, hands (distal and proximal interphalangeal joints), and spine. If the diagnosis is uncertain, plain x-rays can often differentiate between OA and other forms of arthritis.

Treatment for OA centers around pain relief and includes acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Since there is no real inflammation, anti-inflammatory medications have no proven advantage over analgesics such as acetaminophen. The FP suggested acetaminophen at a dose not to exceed 4 g/d. The FP also suggested that the patient exercise, as well as use over-the-counter NSAIDs in addition to acetaminophen intermittently if the acetaminophen failed to provide sufficient pain relief.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed osteoarthritis (OA) after noting Heberden’s nodes and Bouchard’s nodes at the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints, respectively.

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States. Twenty-one million adults have functional limitations because of arthritis. Fifty percent of adults ages 65 years or older have been given an arthritis diagnosis. The most commonly affected joints are the knees, hips, hands (distal and proximal interphalangeal joints), and spine. If the diagnosis is uncertain, plain x-rays can often differentiate between OA and other forms of arthritis.

Treatment for OA centers around pain relief and includes acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Since there is no real inflammation, anti-inflammatory medications have no proven advantage over analgesics such as acetaminophen. The FP suggested acetaminophen at a dose not to exceed 4 g/d. The FP also suggested that the patient exercise, as well as use over-the-counter NSAIDs in addition to acetaminophen intermittently if the acetaminophen failed to provide sufficient pain relief.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Finger pain, rashes

The FP suspected psoriatic arthritis (PsA) based on the silvery plaques on the dorsum of her hand and the swelling of her distal interphalangeal joints. The patient also had silvery plaques on her elbows and some pitting of the nails. Lab tests confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The patient had an elevated ESR that was consistent with an inflammatory process (rather than the degenerative changes of osteoarthritis [OA]). In addition, radiographs showed periarticular joint erosions typical of PsA.

Changes of PsA on x-rays may show periarticular joint erosions, “pencil-in-cup” deformity, osteolysis, telescoping of digits, and asymmetric sacroiliitis. The distribution of PsA can involve the hands, feet, knees, spine, and sacroiliac joints. There are 5 types of PsA:

- Symmetric arthritis involves multiple pairs of symmetric joints in the hands and feet. It resembles rheumatoid arthritis.

- Asymmetric arthritis involves one to 3 joints (eg, knee, hip, ankle, or wrist) in an asymmetric pattern. Hands and feet may have enlarged “sausage” digits due to dactylitis. It is the most common type of PsA.

- Distal interphalangeal predominant (DIP) arthritis involves distal joints of the fingers and toes. It may be confused with OA, but nail changes (eg, pitting) are common in this type of PsA.

- Spondylitis (axial arthritis) includes inflammation of the spinal column that causes a stiff neck and pain in the lower back and sacroiliac area. The arthritis may involve peripheral joints in the hands, arms, hips, legs, or feet.

- Arthritis mutilans is a severe, deforming type of arthritis that usually affects a few joints in the hands and feet.

Treatment options include methotrexate and biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor-α medications. In this case, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist and chose to begin a low dose of oral methotrexate weekly.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected psoriatic arthritis (PsA) based on the silvery plaques on the dorsum of her hand and the swelling of her distal interphalangeal joints. The patient also had silvery plaques on her elbows and some pitting of the nails. Lab tests confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The patient had an elevated ESR that was consistent with an inflammatory process (rather than the degenerative changes of osteoarthritis [OA]). In addition, radiographs showed periarticular joint erosions typical of PsA.

Changes of PsA on x-rays may show periarticular joint erosions, “pencil-in-cup” deformity, osteolysis, telescoping of digits, and asymmetric sacroiliitis. The distribution of PsA can involve the hands, feet, knees, spine, and sacroiliac joints. There are 5 types of PsA:

- Symmetric arthritis involves multiple pairs of symmetric joints in the hands and feet. It resembles rheumatoid arthritis.

- Asymmetric arthritis involves one to 3 joints (eg, knee, hip, ankle, or wrist) in an asymmetric pattern. Hands and feet may have enlarged “sausage” digits due to dactylitis. It is the most common type of PsA.

- Distal interphalangeal predominant (DIP) arthritis involves distal joints of the fingers and toes. It may be confused with OA, but nail changes (eg, pitting) are common in this type of PsA.

- Spondylitis (axial arthritis) includes inflammation of the spinal column that causes a stiff neck and pain in the lower back and sacroiliac area. The arthritis may involve peripheral joints in the hands, arms, hips, legs, or feet.

- Arthritis mutilans is a severe, deforming type of arthritis that usually affects a few joints in the hands and feet.

Treatment options include methotrexate and biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor-α medications. In this case, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist and chose to begin a low dose of oral methotrexate weekly.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected psoriatic arthritis (PsA) based on the silvery plaques on the dorsum of her hand and the swelling of her distal interphalangeal joints. The patient also had silvery plaques on her elbows and some pitting of the nails. Lab tests confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The patient had an elevated ESR that was consistent with an inflammatory process (rather than the degenerative changes of osteoarthritis [OA]). In addition, radiographs showed periarticular joint erosions typical of PsA.

Changes of PsA on x-rays may show periarticular joint erosions, “pencil-in-cup” deformity, osteolysis, telescoping of digits, and asymmetric sacroiliitis. The distribution of PsA can involve the hands, feet, knees, spine, and sacroiliac joints. There are 5 types of PsA:

- Symmetric arthritis involves multiple pairs of symmetric joints in the hands and feet. It resembles rheumatoid arthritis.

- Asymmetric arthritis involves one to 3 joints (eg, knee, hip, ankle, or wrist) in an asymmetric pattern. Hands and feet may have enlarged “sausage” digits due to dactylitis. It is the most common type of PsA.

- Distal interphalangeal predominant (DIP) arthritis involves distal joints of the fingers and toes. It may be confused with OA, but nail changes (eg, pitting) are common in this type of PsA.

- Spondylitis (axial arthritis) includes inflammation of the spinal column that causes a stiff neck and pain in the lower back and sacroiliac area. The arthritis may involve peripheral joints in the hands, arms, hips, legs, or feet.

- Arthritis mutilans is a severe, deforming type of arthritis that usually affects a few joints in the hands and feet.

Treatment options include methotrexate and biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor-α medications. In this case, the patient was referred to a rheumatologist and chose to begin a low dose of oral methotrexate weekly.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Usatine R. Arthritis overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:562-568.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

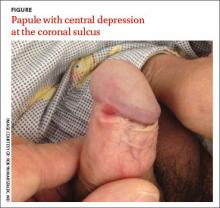

Painless penile papule

A 36-year-old man sought treatment at our outpatient dermatology clinic for an asymptomatic penile lesion that he’d had for a month. He’d been diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection 5 years earlier, and was taking highly active antiretroviral therapy of emtricitabine 200 mg/tenofovir 300 mg daily and nevirapine 200 mg twice a day. The patient’s CD4 T-cell count was 530 cells/mm3 (normal for a nonimmunocompromised adult is 500-1200 cells/mm3) and his viral load was undetectable. He wasn’t in a committed relationship and reported having no sexual partners for many years.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, 7 mm white to pink keratotic papule with a central depression near the coronal sulcus (FIGURE). No ulcers or erosions were seen. The patient denied having urethral discharge, pain, or pruritus. During the previous week, he said he’d applied triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily to the area with no improvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Syphilis

The asymptomatic nature and clinical presentation of the patient’s lesion prompted us to suspect syphilis. Skin biopsy of the lesion revealed features that were consistent with syphilis and a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was positive with a titer of 1:32, confirming our suspicions. (His RPR was checked 3 years earlier and it was nonreactive.) Despite the diagnosis, the patient continued to deny having had any recent sexual encounters.

The “great mimicker”

Syphilis infection occurs after inoculation of Treponema pallidum through microscopic breaks in the mucosal surfaces followed by attachment and invasion of spirochete into host cells. Treponemes then multiply and circulate to the regional lymph nodes and internal organs, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations based on the stage of the infection (primary, secondary, and latent/late), the time that has elapsed since inoculation, and the host’s immune response.

Syphilis is often referred to as the “great mimicker” based on its propensity to present as one of a variety of phenotypes. Syphilitic chancres often mimic other genital ulcers, including those caused by different sexually transmitted diseases such as chancroid (as a result of infection with Haemophilus ducreyi) or granuloma inguinale (Klebsiella granulomatis). Syphilitic chancres may also appear clinically similar to genital aphthous ulcers or cutaneous manifestations of herpes simplex virus.

Chancroid. While the tender ulcer of chancroid has a ragged and undermined border with a dirty gray base, the classic, nontender, syphilitic chancre has a clean base with an indurated border reminiscent of the firm quality of cartilage.1

Granuloma inguinale presents as one or multiple nontender, friable, soft, red granulating papules that lack the firm border or clean base of the syphilitic chancre.1

Aphthous ulcers are often soft, shallow, and tender, appearing punched-out with surrounding rims of erythema and clean, white, even bases.2

Genital herpes simplex virus is characterized by tender eroded coalescing vesicles with scalloped, soft borders, contrasted by the indurated smooth rounded border of the syphilitic chancre.1

How syphilis affects HIV, and vice versa

HIV infection has been known to alter the natural history and presentation of syphilis, and syphilis may also impact the course and evaluation of HIV infection.3 Syphilis and other infections that lead to genital ulcers increase an individual’s propensity to acquire HIV due to the loss of the barrier function of the epithelial membrane and the production of cytokines stimulated by treponemal lipoproteins.4 This facilitates transmission of the virus.

In the typical clinical presentation of primary syphilis in an immunocompetent patient, an indolent papule develops 10 to 90 days after inoculation and subsequently ulcerates into an indurated chancre. Patients with HIV may develop multiple chancres that are larger, deeper, and more ulcerative.4-6 Approximately one-quarter of these patients present with lesions of both primary and secondary syphilis at the time of diagnosis.5 However, our patient presented with a solitary painless indurated papule after years of stable and well-controlled HIV infection; this suggests that cutaneous manifestations of syphilis may have atypical clinical presentations in patients who are also infected with HIV.5,6

What you’ll see in the secondary stage

In immunocompetent patients, secondary syphilis is characterized by fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, moth-eaten alopecia, focal neurologic findings, condyloma lata, mucocutaneous aphthae, and a generalized papulosquamous eruption.7 After 3 to

12 weeks, the secondary infection spontaneously disappears and leads into the latency period, which may last years. Thirty percent of untreated patients progress from latent to tertiary syphilis.7 During this stage, treponemes invade the central nervous system, heart, bone, and skin, triggering vigorous host cellular immune responses and delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

When complicated by HIV, secondary syphilis may present along a more aggressive course, with early neurologic and ophthalmologic involvement.8 Patients coinfected with syphilis and HIV are also more prone to developing neurosyphilis—even after completing penicillin therapy—and a more intensive diagnostic evaluation should be considered for such patients.9 Higher protein levels and lower glucose levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are also reported in HIV-infected patients with syphilis,10 likely due to the weakened host immune response.

What you’ll see on the labwork

Like other acute infections, syphilis may cause transient increases in viral load with decreases in the CD4 count that resolve after treatment.11-14 Also worth noting:

- RPR at titers of >1:32 and CD4 counts <350 cells/mm3 may be associated with neurosyphilis in patients with HIV.10

- High RPR titers have been linked to elevated liver function enzymes in patients with syphilis and HIV, although the clinical significance of this is

unknown.15

Treat with penicillin

All stages of syphilis can be treated with penicillin G, a standard benzathine penicillin.16 Adult patients with primary and secondary syphilis should receive a single intramuscular dose of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G.16

Our patient responded well to the recommended course of penicillin therapy and no other systemic signs of the infection were noted. He was also counseled on safe sexual practices and barrier protection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Masterpol, 955 Main Street Suite G6, Winchester, MA 01890; [email protected]

1. Goldsmith, Lowell, Fischer B. Syphilis. Rochester, NY: VisualDx. Available at: http://www.visualdx.com/. Updated January 19, 2015. Accessed February 13, 2015.

2. Allen C, Woo SB. Aphthous Stomatitis. Rochester, NY: VisualDx. Available at: http://www.visualdx.com/. Updated August 21, 2013. Accessed February 13, 2015.

3. Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Syphilis and HIV Infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 2007:44:1222-1228.

4. Marra CM. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Neurol. 1992;12:43-50.

5. Rompalo AM, Lawlor J, Seaman P, et al. Modification of syphilitic genital ulcer manifestations by coexistent HIV infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:448-454.

6. Schöfer H, Imhof M, Thoma-Greber E, et al. Active syphilis in HIV infection: a multicentre retrospective survey. The German AIDS Study Group (GASG). Genitourin Med. 1996;72:176-181.

7. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011.

8. Lynn WA, Lightman S. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:456-466.

9. Musher DM. Syphilis, neurosyphilis, penicillin, and AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1201-1206.

10. Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Smith SL, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients with syphilis: association with clinical and laboratory features. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:369-376.

11. Sadiq ST, McSorley J, Copas AJ, et al. The effects of early syphilis on CD4 counts and HIV-1 RNA viral loads in blood and semen. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:380-385.

12. Kofoed K, Gerstoft J, Mathiesen LR, et al. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 coinfection: influence on CD4 T-cell count, HIV-1 viral load, and treatment response. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:143-148.

13. Dyer JR, Eron JJ, Hoffman IF, et al. Association of CD4 cell depletion and elevated blood and seminal plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) RNA concentrations with genital ulcer disease in HIV-1-infected men in Malawi. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:224-227.

14. Buchacz K, Patel P, Taylor M, et al. Syphilis increases HIV viral load and decreases CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients with new syphilis infections. AIDS. 2004;18:2075-2079.

15. Palacios R, Navarro F, Narankiewicz D, et al. Liver involvement in HIV-infected patients with early syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:31-33.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 STD Treatment Guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/genital-ulcers.htm#a5. Accessed February 4, 2015.

A 36-year-old man sought treatment at our outpatient dermatology clinic for an asymptomatic penile lesion that he’d had for a month. He’d been diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection 5 years earlier, and was taking highly active antiretroviral therapy of emtricitabine 200 mg/tenofovir 300 mg daily and nevirapine 200 mg twice a day. The patient’s CD4 T-cell count was 530 cells/mm3 (normal for a nonimmunocompromised adult is 500-1200 cells/mm3) and his viral load was undetectable. He wasn’t in a committed relationship and reported having no sexual partners for many years.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, 7 mm white to pink keratotic papule with a central depression near the coronal sulcus (FIGURE). No ulcers or erosions were seen. The patient denied having urethral discharge, pain, or pruritus. During the previous week, he said he’d applied triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily to the area with no improvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Syphilis

The asymptomatic nature and clinical presentation of the patient’s lesion prompted us to suspect syphilis. Skin biopsy of the lesion revealed features that were consistent with syphilis and a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was positive with a titer of 1:32, confirming our suspicions. (His RPR was checked 3 years earlier and it was nonreactive.) Despite the diagnosis, the patient continued to deny having had any recent sexual encounters.

The “great mimicker”

Syphilis infection occurs after inoculation of Treponema pallidum through microscopic breaks in the mucosal surfaces followed by attachment and invasion of spirochete into host cells. Treponemes then multiply and circulate to the regional lymph nodes and internal organs, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations based on the stage of the infection (primary, secondary, and latent/late), the time that has elapsed since inoculation, and the host’s immune response.

Syphilis is often referred to as the “great mimicker” based on its propensity to present as one of a variety of phenotypes. Syphilitic chancres often mimic other genital ulcers, including those caused by different sexually transmitted diseases such as chancroid (as a result of infection with Haemophilus ducreyi) or granuloma inguinale (Klebsiella granulomatis). Syphilitic chancres may also appear clinically similar to genital aphthous ulcers or cutaneous manifestations of herpes simplex virus.

Chancroid. While the tender ulcer of chancroid has a ragged and undermined border with a dirty gray base, the classic, nontender, syphilitic chancre has a clean base with an indurated border reminiscent of the firm quality of cartilage.1

Granuloma inguinale presents as one or multiple nontender, friable, soft, red granulating papules that lack the firm border or clean base of the syphilitic chancre.1

Aphthous ulcers are often soft, shallow, and tender, appearing punched-out with surrounding rims of erythema and clean, white, even bases.2

Genital herpes simplex virus is characterized by tender eroded coalescing vesicles with scalloped, soft borders, contrasted by the indurated smooth rounded border of the syphilitic chancre.1

How syphilis affects HIV, and vice versa

HIV infection has been known to alter the natural history and presentation of syphilis, and syphilis may also impact the course and evaluation of HIV infection.3 Syphilis and other infections that lead to genital ulcers increase an individual’s propensity to acquire HIV due to the loss of the barrier function of the epithelial membrane and the production of cytokines stimulated by treponemal lipoproteins.4 This facilitates transmission of the virus.

In the typical clinical presentation of primary syphilis in an immunocompetent patient, an indolent papule develops 10 to 90 days after inoculation and subsequently ulcerates into an indurated chancre. Patients with HIV may develop multiple chancres that are larger, deeper, and more ulcerative.4-6 Approximately one-quarter of these patients present with lesions of both primary and secondary syphilis at the time of diagnosis.5 However, our patient presented with a solitary painless indurated papule after years of stable and well-controlled HIV infection; this suggests that cutaneous manifestations of syphilis may have atypical clinical presentations in patients who are also infected with HIV.5,6

What you’ll see in the secondary stage

In immunocompetent patients, secondary syphilis is characterized by fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, moth-eaten alopecia, focal neurologic findings, condyloma lata, mucocutaneous aphthae, and a generalized papulosquamous eruption.7 After 3 to

12 weeks, the secondary infection spontaneously disappears and leads into the latency period, which may last years. Thirty percent of untreated patients progress from latent to tertiary syphilis.7 During this stage, treponemes invade the central nervous system, heart, bone, and skin, triggering vigorous host cellular immune responses and delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

When complicated by HIV, secondary syphilis may present along a more aggressive course, with early neurologic and ophthalmologic involvement.8 Patients coinfected with syphilis and HIV are also more prone to developing neurosyphilis—even after completing penicillin therapy—and a more intensive diagnostic evaluation should be considered for such patients.9 Higher protein levels and lower glucose levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are also reported in HIV-infected patients with syphilis,10 likely due to the weakened host immune response.

What you’ll see on the labwork

Like other acute infections, syphilis may cause transient increases in viral load with decreases in the CD4 count that resolve after treatment.11-14 Also worth noting:

- RPR at titers of >1:32 and CD4 counts <350 cells/mm3 may be associated with neurosyphilis in patients with HIV.10

- High RPR titers have been linked to elevated liver function enzymes in patients with syphilis and HIV, although the clinical significance of this is

unknown.15

Treat with penicillin

All stages of syphilis can be treated with penicillin G, a standard benzathine penicillin.16 Adult patients with primary and secondary syphilis should receive a single intramuscular dose of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G.16

Our patient responded well to the recommended course of penicillin therapy and no other systemic signs of the infection were noted. He was also counseled on safe sexual practices and barrier protection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Masterpol, 955 Main Street Suite G6, Winchester, MA 01890; [email protected]

A 36-year-old man sought treatment at our outpatient dermatology clinic for an asymptomatic penile lesion that he’d had for a month. He’d been diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection 5 years earlier, and was taking highly active antiretroviral therapy of emtricitabine 200 mg/tenofovir 300 mg daily and nevirapine 200 mg twice a day. The patient’s CD4 T-cell count was 530 cells/mm3 (normal for a nonimmunocompromised adult is 500-1200 cells/mm3) and his viral load was undetectable. He wasn’t in a committed relationship and reported having no sexual partners for many years.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, 7 mm white to pink keratotic papule with a central depression near the coronal sulcus (FIGURE). No ulcers or erosions were seen. The patient denied having urethral discharge, pain, or pruritus. During the previous week, he said he’d applied triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily to the area with no improvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Syphilis

The asymptomatic nature and clinical presentation of the patient’s lesion prompted us to suspect syphilis. Skin biopsy of the lesion revealed features that were consistent with syphilis and a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was positive with a titer of 1:32, confirming our suspicions. (His RPR was checked 3 years earlier and it was nonreactive.) Despite the diagnosis, the patient continued to deny having had any recent sexual encounters.

The “great mimicker”

Syphilis infection occurs after inoculation of Treponema pallidum through microscopic breaks in the mucosal surfaces followed by attachment and invasion of spirochete into host cells. Treponemes then multiply and circulate to the regional lymph nodes and internal organs, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations based on the stage of the infection (primary, secondary, and latent/late), the time that has elapsed since inoculation, and the host’s immune response.

Syphilis is often referred to as the “great mimicker” based on its propensity to present as one of a variety of phenotypes. Syphilitic chancres often mimic other genital ulcers, including those caused by different sexually transmitted diseases such as chancroid (as a result of infection with Haemophilus ducreyi) or granuloma inguinale (Klebsiella granulomatis). Syphilitic chancres may also appear clinically similar to genital aphthous ulcers or cutaneous manifestations of herpes simplex virus.

Chancroid. While the tender ulcer of chancroid has a ragged and undermined border with a dirty gray base, the classic, nontender, syphilitic chancre has a clean base with an indurated border reminiscent of the firm quality of cartilage.1

Granuloma inguinale presents as one or multiple nontender, friable, soft, red granulating papules that lack the firm border or clean base of the syphilitic chancre.1

Aphthous ulcers are often soft, shallow, and tender, appearing punched-out with surrounding rims of erythema and clean, white, even bases.2

Genital herpes simplex virus is characterized by tender eroded coalescing vesicles with scalloped, soft borders, contrasted by the indurated smooth rounded border of the syphilitic chancre.1

How syphilis affects HIV, and vice versa

HIV infection has been known to alter the natural history and presentation of syphilis, and syphilis may also impact the course and evaluation of HIV infection.3 Syphilis and other infections that lead to genital ulcers increase an individual’s propensity to acquire HIV due to the loss of the barrier function of the epithelial membrane and the production of cytokines stimulated by treponemal lipoproteins.4 This facilitates transmission of the virus.

In the typical clinical presentation of primary syphilis in an immunocompetent patient, an indolent papule develops 10 to 90 days after inoculation and subsequently ulcerates into an indurated chancre. Patients with HIV may develop multiple chancres that are larger, deeper, and more ulcerative.4-6 Approximately one-quarter of these patients present with lesions of both primary and secondary syphilis at the time of diagnosis.5 However, our patient presented with a solitary painless indurated papule after years of stable and well-controlled HIV infection; this suggests that cutaneous manifestations of syphilis may have atypical clinical presentations in patients who are also infected with HIV.5,6

What you’ll see in the secondary stage

In immunocompetent patients, secondary syphilis is characterized by fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, moth-eaten alopecia, focal neurologic findings, condyloma lata, mucocutaneous aphthae, and a generalized papulosquamous eruption.7 After 3 to

12 weeks, the secondary infection spontaneously disappears and leads into the latency period, which may last years. Thirty percent of untreated patients progress from latent to tertiary syphilis.7 During this stage, treponemes invade the central nervous system, heart, bone, and skin, triggering vigorous host cellular immune responses and delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

When complicated by HIV, secondary syphilis may present along a more aggressive course, with early neurologic and ophthalmologic involvement.8 Patients coinfected with syphilis and HIV are also more prone to developing neurosyphilis—even after completing penicillin therapy—and a more intensive diagnostic evaluation should be considered for such patients.9 Higher protein levels and lower glucose levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are also reported in HIV-infected patients with syphilis,10 likely due to the weakened host immune response.

What you’ll see on the labwork

Like other acute infections, syphilis may cause transient increases in viral load with decreases in the CD4 count that resolve after treatment.11-14 Also worth noting:

- RPR at titers of >1:32 and CD4 counts <350 cells/mm3 may be associated with neurosyphilis in patients with HIV.10

- High RPR titers have been linked to elevated liver function enzymes in patients with syphilis and HIV, although the clinical significance of this is

unknown.15

Treat with penicillin

All stages of syphilis can be treated with penicillin G, a standard benzathine penicillin.16 Adult patients with primary and secondary syphilis should receive a single intramuscular dose of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G.16

Our patient responded well to the recommended course of penicillin therapy and no other systemic signs of the infection were noted. He was also counseled on safe sexual practices and barrier protection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Masterpol, 955 Main Street Suite G6, Winchester, MA 01890; [email protected]

1. Goldsmith, Lowell, Fischer B. Syphilis. Rochester, NY: VisualDx. Available at: http://www.visualdx.com/. Updated January 19, 2015. Accessed February 13, 2015.

2. Allen C, Woo SB. Aphthous Stomatitis. Rochester, NY: VisualDx. Available at: http://www.visualdx.com/. Updated August 21, 2013. Accessed February 13, 2015.

3. Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Syphilis and HIV Infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 2007:44:1222-1228.

4. Marra CM. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Neurol. 1992;12:43-50.