User login

Breast rash

The FP was concerned about Paget disease of the breast and performed a 4 mm punch biopsy of the affected area, including a portion of the nipple. The pathology confirmed the diagnosis.

Paget disease of the breast is a low-grade malignancy that is often associated with other malignancies. It presents clinically in the nipple-areolar complex as a dermatitis that may be erythematous, eczematous, scaly, raw, vesicular, or ulcerated. The nipple is usually initially involved, and the lesion then spreads to the areola.

Most patients delay presentation (median 6-8 months), assuming the abnormality is benign. Presenting symptoms are sometimes limited to persistent pain, burning, and/or pruritus of the nipple. A palpable breast mass is present in half of all cases, but is often located more than 2 cm from the nipple-areolar complex. Twenty percent of cases will have a mammographic abnormality without a palpable mass, and 25% of cases will have neither a mass nor abnormal mammogram, but will have an occult ductal carcinoma.

The treatment and prognosis of Paget disease of the breast is first based on the stage of any underlying breast cancer. Simple mastectomy has traditionally been the standard treatment for isolated Paget disease of the breast. Breast-conserving surgery combined with breast irradiation is gaining wider acceptance.

In this case our patient chose to have a simple mastectomy with a transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) flap reconstruction.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Paget disease of the breast. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al,eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:557-560.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP was concerned about Paget disease of the breast and performed a 4 mm punch biopsy of the affected area, including a portion of the nipple. The pathology confirmed the diagnosis.

Paget disease of the breast is a low-grade malignancy that is often associated with other malignancies. It presents clinically in the nipple-areolar complex as a dermatitis that may be erythematous, eczematous, scaly, raw, vesicular, or ulcerated. The nipple is usually initially involved, and the lesion then spreads to the areola.

Most patients delay presentation (median 6-8 months), assuming the abnormality is benign. Presenting symptoms are sometimes limited to persistent pain, burning, and/or pruritus of the nipple. A palpable breast mass is present in half of all cases, but is often located more than 2 cm from the nipple-areolar complex. Twenty percent of cases will have a mammographic abnormality without a palpable mass, and 25% of cases will have neither a mass nor abnormal mammogram, but will have an occult ductal carcinoma.

The treatment and prognosis of Paget disease of the breast is first based on the stage of any underlying breast cancer. Simple mastectomy has traditionally been the standard treatment for isolated Paget disease of the breast. Breast-conserving surgery combined with breast irradiation is gaining wider acceptance.

In this case our patient chose to have a simple mastectomy with a transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) flap reconstruction.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Paget disease of the breast. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al,eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:557-560.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP was concerned about Paget disease of the breast and performed a 4 mm punch biopsy of the affected area, including a portion of the nipple. The pathology confirmed the diagnosis.

Paget disease of the breast is a low-grade malignancy that is often associated with other malignancies. It presents clinically in the nipple-areolar complex as a dermatitis that may be erythematous, eczematous, scaly, raw, vesicular, or ulcerated. The nipple is usually initially involved, and the lesion then spreads to the areola.

Most patients delay presentation (median 6-8 months), assuming the abnormality is benign. Presenting symptoms are sometimes limited to persistent pain, burning, and/or pruritus of the nipple. A palpable breast mass is present in half of all cases, but is often located more than 2 cm from the nipple-areolar complex. Twenty percent of cases will have a mammographic abnormality without a palpable mass, and 25% of cases will have neither a mass nor abnormal mammogram, but will have an occult ductal carcinoma.

The treatment and prognosis of Paget disease of the breast is first based on the stage of any underlying breast cancer. Simple mastectomy has traditionally been the standard treatment for isolated Paget disease of the breast. Breast-conserving surgery combined with breast irradiation is gaining wider acceptance.

In this case our patient chose to have a simple mastectomy with a transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) flap reconstruction.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Paget disease of the breast. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al,eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:557-560.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Firm nodules on back

The FP originally thought the nodules were abscesses, but began to suspect that they might be metastases from her breast cancer. A punch biopsy was performed with local anesthesia. There was no abscess, fluid, or fatty tissue and the solid tissue was sent for pathology. Pathology came back and confirmed the FP’s suspicion.

The FP shared the results of the biopsy with the patient and referred her to an oncologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Breast cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:551-556.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP originally thought the nodules were abscesses, but began to suspect that they might be metastases from her breast cancer. A punch biopsy was performed with local anesthesia. There was no abscess, fluid, or fatty tissue and the solid tissue was sent for pathology. Pathology came back and confirmed the FP’s suspicion.

The FP shared the results of the biopsy with the patient and referred her to an oncologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Breast cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:551-556.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP originally thought the nodules were abscesses, but began to suspect that they might be metastases from her breast cancer. A punch biopsy was performed with local anesthesia. There was no abscess, fluid, or fatty tissue and the solid tissue was sent for pathology. Pathology came back and confirmed the FP’s suspicion.

The FP shared the results of the biopsy with the patient and referred her to an oncologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Breast cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:551-556.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Swollen breast and arm

The FP, who had palpated firm, matted nodes in the left axilla, immediately recognized the peau d’orange sign of breast cancer with lymphedema. (With this sign, the skin of the breast looks that of an orange as a consequence of lymphedema.)

The FP explained to the patient that she most likely had breast cancer and referred her to the local university breast center. While the prognosis appeared poor, the FP recognized the importance of making every effort to have the disease staged to determine the most appropriate therapies.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Breast cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:551-556.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP, who had palpated firm, matted nodes in the left axilla, immediately recognized the peau d’orange sign of breast cancer with lymphedema. (With this sign, the skin of the breast looks that of an orange as a consequence of lymphedema.)

The FP explained to the patient that she most likely had breast cancer and referred her to the local university breast center. While the prognosis appeared poor, the FP recognized the importance of making every effort to have the disease staged to determine the most appropriate therapies.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Breast cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:551-556.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP, who had palpated firm, matted nodes in the left axilla, immediately recognized the peau d’orange sign of breast cancer with lymphedema. (With this sign, the skin of the breast looks that of an orange as a consequence of lymphedema.)

The FP explained to the patient that she most likely had breast cancer and referred her to the local university breast center. While the prognosis appeared poor, the FP recognized the importance of making every effort to have the disease staged to determine the most appropriate therapies.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Breast cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:551-556.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Sore throat and left ear pain

A 79 year-old man sought care at our clinic for pain in his left ear and a severe sore throat that had been bothering him for the past 2 days. He also complained of pain when he swallowed, a decreased appetite, and dizziness. He denied weight loss, fever, tinnitus, subjective hearing loss, unilateral facial droop, or weakness.

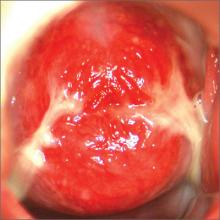

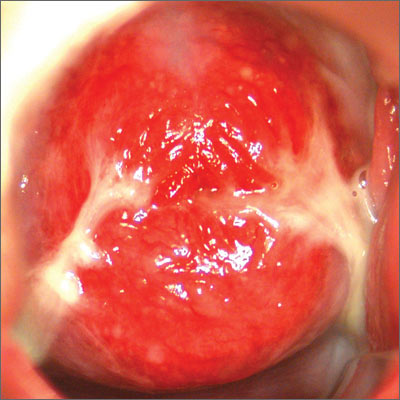

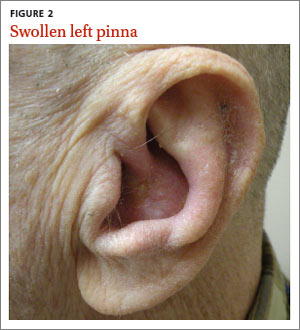

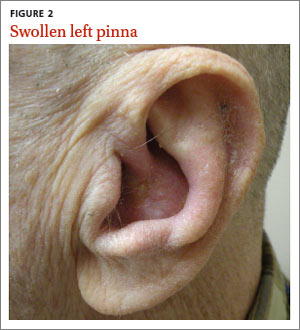

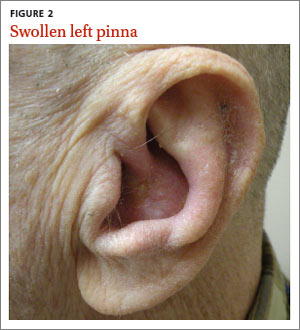

On physical exam, we noted vesicles on an erythematous base on his hard palate. They were on the left side and didn’t cross the midline (FIGURE 1). The left pinna was mildly erythematous and swollen (FIGURE 2) without obvious vesicles, although we noted vesicles in the external auditory canal on otoscopic examination. The tympanic membrane was normal, as was the patient’s right ear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.1 An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected.1 Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.1

Ramsay Hunt syndrome classically presents with unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles located ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus.2

Several types of infection are in the differential diagnosis

Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), group A Streptococcus (GAS), and measles.

HSV-1 can cause oral symptoms similar to Ramsay Hunt syndrome. However,

HSV-1 doesn’t cause vesicles in the ear. Also worth noting: Recurrent HSV-1 infections normally involve keratinized surfaces such as the vermilion border and gums, but rarely the hard palate.3

EBV can cause multiple systemic symptoms. It can cause leukoplakia in the mouth— most often on the sides of the tongue—but does not cause vesicles.4

GAS presents as a sore throat, fever, anterior cervical lymphadenitis, and a scarlatiniform rash. Oral manifestations can include tonsillar erythema with or without exudate, soft palate petechiae, and a red swollen uvula.5 Use of validated clinical prediction tools, such as the sore throat tool found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1228750/pdf/cmaj_158_1_75.pdf, can help distinguish GAS infection from other conditions.6-8

Measles typically occurs in children and young adults. Infection in immunized individuals is rare. It presents with fever and the “3 Cs”—cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Koplik’s spots are blue to white ulcerated lesions on the buccal mucosa, typically opposite the first and second molars, although they can occur anywhere in the mouth. They precede the generalized maculopapular rash of measles.9

Although it’s a clinical Dx, lab testing can provide confirmation

Diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis,10 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing,11 or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity.10 PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%),11 is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.12

For our patient, we obtained swabs of the oral vesicles and ordered a DFA analysis; however, the sample didn’t show VZV. This may have been due to inadequate sampling. (Proper sampling requires that there be an adequate collection of cells from the base of the vesicles.)

Oral antivirals, steroids are mainstays of treatment

Treatment with an oral steroid such as prednisone in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function; however, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.13

Our patient was treated with oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days. After one week of treatment, his symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Moss, MD, 4700 North Las Vegas Boulevard, Nellis AFB, NV 89191; [email protected]

1. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://www.rarediseases.org/rare-disease-information/rare-diseases/byID/1153/viewFullReport. Accessed December 30, 2014.

2. Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:149-154.

3. Habif TP. Warts, herpes simplex, and other viral infections. Clinical Dermatology. A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier; 2010: 467-471.

4. Habif TP. Premalignant and malignant nonmelanoma skin tumors. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2010:829.

5. Bope ET, Kellerman RD. Pharyngitis. Conn’s Current Therapy 2012. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:32.

6. Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1:239-246.

7. McIsaac WJ, Goel V, To T, et al. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ. 2000;163:811-815.

8. McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, et al. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ. 1998;158:75-83.

9. Habif TP. Exanthems and drug eruptions. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2010:544-547.

10. Chan EL, Brandt K, Horsman GB. Comparison of Chemicon SimulFluor direct fluorescent antibody staining with cell culture and shell vial direct immunoperoxidase staining for detection of herpes simplex virus and with cytospin direct immunofluorescence staining for detection of varicella-zoster virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:909-912.

11. Harbecke R, Oxman MN, Arnold BA, et al; Shingles Prevention Study Group. A real-time PCR assay to identify and discriminate among wild-type and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in clinical specimens, and comparison with the clinical diagnoses. J Med Virol. 2009;81: 1310-1322.

12. Lopez A, Schmid S, Bialek S. Varicella. In: Roush SW, McIntyre L, Baldy LM, eds. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 5th ed. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

13. Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, et al. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:353-357.

A 79 year-old man sought care at our clinic for pain in his left ear and a severe sore throat that had been bothering him for the past 2 days. He also complained of pain when he swallowed, a decreased appetite, and dizziness. He denied weight loss, fever, tinnitus, subjective hearing loss, unilateral facial droop, or weakness.

On physical exam, we noted vesicles on an erythematous base on his hard palate. They were on the left side and didn’t cross the midline (FIGURE 1). The left pinna was mildly erythematous and swollen (FIGURE 2) without obvious vesicles, although we noted vesicles in the external auditory canal on otoscopic examination. The tympanic membrane was normal, as was the patient’s right ear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.1 An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected.1 Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.1

Ramsay Hunt syndrome classically presents with unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles located ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus.2

Several types of infection are in the differential diagnosis

Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), group A Streptococcus (GAS), and measles.

HSV-1 can cause oral symptoms similar to Ramsay Hunt syndrome. However,

HSV-1 doesn’t cause vesicles in the ear. Also worth noting: Recurrent HSV-1 infections normally involve keratinized surfaces such as the vermilion border and gums, but rarely the hard palate.3

EBV can cause multiple systemic symptoms. It can cause leukoplakia in the mouth— most often on the sides of the tongue—but does not cause vesicles.4

GAS presents as a sore throat, fever, anterior cervical lymphadenitis, and a scarlatiniform rash. Oral manifestations can include tonsillar erythema with or without exudate, soft palate petechiae, and a red swollen uvula.5 Use of validated clinical prediction tools, such as the sore throat tool found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1228750/pdf/cmaj_158_1_75.pdf, can help distinguish GAS infection from other conditions.6-8

Measles typically occurs in children and young adults. Infection in immunized individuals is rare. It presents with fever and the “3 Cs”—cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Koplik’s spots are blue to white ulcerated lesions on the buccal mucosa, typically opposite the first and second molars, although they can occur anywhere in the mouth. They precede the generalized maculopapular rash of measles.9

Although it’s a clinical Dx, lab testing can provide confirmation

Diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis,10 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing,11 or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity.10 PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%),11 is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.12

For our patient, we obtained swabs of the oral vesicles and ordered a DFA analysis; however, the sample didn’t show VZV. This may have been due to inadequate sampling. (Proper sampling requires that there be an adequate collection of cells from the base of the vesicles.)

Oral antivirals, steroids are mainstays of treatment

Treatment with an oral steroid such as prednisone in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function; however, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.13

Our patient was treated with oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days. After one week of treatment, his symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Moss, MD, 4700 North Las Vegas Boulevard, Nellis AFB, NV 89191; [email protected]

A 79 year-old man sought care at our clinic for pain in his left ear and a severe sore throat that had been bothering him for the past 2 days. He also complained of pain when he swallowed, a decreased appetite, and dizziness. He denied weight loss, fever, tinnitus, subjective hearing loss, unilateral facial droop, or weakness.

On physical exam, we noted vesicles on an erythematous base on his hard palate. They were on the left side and didn’t cross the midline (FIGURE 1). The left pinna was mildly erythematous and swollen (FIGURE 2) without obvious vesicles, although we noted vesicles in the external auditory canal on otoscopic examination. The tympanic membrane was normal, as was the patient’s right ear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.1 An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected.1 Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.1

Ramsay Hunt syndrome classically presents with unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles located ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus.2

Several types of infection are in the differential diagnosis

Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), group A Streptococcus (GAS), and measles.

HSV-1 can cause oral symptoms similar to Ramsay Hunt syndrome. However,

HSV-1 doesn’t cause vesicles in the ear. Also worth noting: Recurrent HSV-1 infections normally involve keratinized surfaces such as the vermilion border and gums, but rarely the hard palate.3

EBV can cause multiple systemic symptoms. It can cause leukoplakia in the mouth— most often on the sides of the tongue—but does not cause vesicles.4

GAS presents as a sore throat, fever, anterior cervical lymphadenitis, and a scarlatiniform rash. Oral manifestations can include tonsillar erythema with or without exudate, soft palate petechiae, and a red swollen uvula.5 Use of validated clinical prediction tools, such as the sore throat tool found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1228750/pdf/cmaj_158_1_75.pdf, can help distinguish GAS infection from other conditions.6-8

Measles typically occurs in children and young adults. Infection in immunized individuals is rare. It presents with fever and the “3 Cs”—cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Koplik’s spots are blue to white ulcerated lesions on the buccal mucosa, typically opposite the first and second molars, although they can occur anywhere in the mouth. They precede the generalized maculopapular rash of measles.9

Although it’s a clinical Dx, lab testing can provide confirmation

Diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis,10 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing,11 or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity.10 PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%),11 is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.12

For our patient, we obtained swabs of the oral vesicles and ordered a DFA analysis; however, the sample didn’t show VZV. This may have been due to inadequate sampling. (Proper sampling requires that there be an adequate collection of cells from the base of the vesicles.)

Oral antivirals, steroids are mainstays of treatment

Treatment with an oral steroid such as prednisone in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function; however, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.13

Our patient was treated with oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days. After one week of treatment, his symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Moss, MD, 4700 North Las Vegas Boulevard, Nellis AFB, NV 89191; [email protected]

1. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://www.rarediseases.org/rare-disease-information/rare-diseases/byID/1153/viewFullReport. Accessed December 30, 2014.

2. Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:149-154.

3. Habif TP. Warts, herpes simplex, and other viral infections. Clinical Dermatology. A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier; 2010: 467-471.

4. Habif TP. Premalignant and malignant nonmelanoma skin tumors. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2010:829.

5. Bope ET, Kellerman RD. Pharyngitis. Conn’s Current Therapy 2012. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:32.

6. Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1:239-246.

7. McIsaac WJ, Goel V, To T, et al. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ. 2000;163:811-815.

8. McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, et al. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ. 1998;158:75-83.

9. Habif TP. Exanthems and drug eruptions. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2010:544-547.

10. Chan EL, Brandt K, Horsman GB. Comparison of Chemicon SimulFluor direct fluorescent antibody staining with cell culture and shell vial direct immunoperoxidase staining for detection of herpes simplex virus and with cytospin direct immunofluorescence staining for detection of varicella-zoster virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:909-912.

11. Harbecke R, Oxman MN, Arnold BA, et al; Shingles Prevention Study Group. A real-time PCR assay to identify and discriminate among wild-type and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in clinical specimens, and comparison with the clinical diagnoses. J Med Virol. 2009;81: 1310-1322.

12. Lopez A, Schmid S, Bialek S. Varicella. In: Roush SW, McIntyre L, Baldy LM, eds. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 5th ed. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

13. Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, et al. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:353-357.

1. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://www.rarediseases.org/rare-disease-information/rare-diseases/byID/1153/viewFullReport. Accessed December 30, 2014.

2. Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:149-154.

3. Habif TP. Warts, herpes simplex, and other viral infections. Clinical Dermatology. A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier; 2010: 467-471.

4. Habif TP. Premalignant and malignant nonmelanoma skin tumors. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2010:829.

5. Bope ET, Kellerman RD. Pharyngitis. Conn’s Current Therapy 2012. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:32.

6. Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1:239-246.

7. McIsaac WJ, Goel V, To T, et al. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ. 2000;163:811-815.

8. McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, et al. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ. 1998;158:75-83.

9. Habif TP. Exanthems and drug eruptions. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2010:544-547.

10. Chan EL, Brandt K, Horsman GB. Comparison of Chemicon SimulFluor direct fluorescent antibody staining with cell culture and shell vial direct immunoperoxidase staining for detection of herpes simplex virus and with cytospin direct immunofluorescence staining for detection of varicella-zoster virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:909-912.

11. Harbecke R, Oxman MN, Arnold BA, et al; Shingles Prevention Study Group. A real-time PCR assay to identify and discriminate among wild-type and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in clinical specimens, and comparison with the clinical diagnoses. J Med Virol. 2009;81: 1310-1322.

12. Lopez A, Schmid S, Bialek S. Varicella. In: Roush SW, McIntyre L, Baldy LM, eds. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 5th ed. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

13. Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, et al. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:353-357.

White vaginal areas

The FP recognized the white areas as leukoplakia suggestive of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Punch biopsies showed moderate vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia II (VIN II) along with associated human papillomavirus (HPV) changes.

More than 50% of patients presenting with vulvar dysplasia have no symptoms. When symptoms are present, pruritus is the most common one. Unlike cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, VIN is usually multifocal. The most common locations include the interlabial grooves, posterior fourchette, and the perineum. Since VIN can appear warty, lesions that are diagnosed as condyloma (as was the case with this patient) and that don’t respond to conservative therapy should be biopsied to rule out VIN.

Biopsy to exclude invasive disease is mandatory prior to any topical treatment. Patients with VIN II or III should have their lesions removed. Basaloid and warty VINs may be treated with ablation on non–hair-bearing epithelium. A CO2 laser is typically used to remove the lesions, although some physicians perform a loop electrosurgical excision procedure.

Alternatives to surgery and laser include topical agents. 5-Fluorouracil cream, which causes a chemical desquamation of the lesion, has traditionally been used to treat VIN. It may result in significant burning, pain, inflammation, edema, and occasional painful ulcerations. Imiquimod cream is a topical immune response modifier that is FDA approved for the treatment of anogenital warts, actinic keratosis, and certain basal cell carcinomas. It has been used to treat multifocal VIN II or III in a few small pilot studies. The cream is self-administered 3 times per week for periods of 6 to 34 weeks.

In this case, the patient was referred for treatment of the VIN and given 2 g of oral metronidazole for the Trichomonas infection. She was advised to inform her most recent sexual partner about the Trichomonas infection so that he might receive treatment. Testing for other sexually transmitted diseases was negative.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:519-524.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP recognized the white areas as leukoplakia suggestive of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Punch biopsies showed moderate vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia II (VIN II) along with associated human papillomavirus (HPV) changes.

More than 50% of patients presenting with vulvar dysplasia have no symptoms. When symptoms are present, pruritus is the most common one. Unlike cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, VIN is usually multifocal. The most common locations include the interlabial grooves, posterior fourchette, and the perineum. Since VIN can appear warty, lesions that are diagnosed as condyloma (as was the case with this patient) and that don’t respond to conservative therapy should be biopsied to rule out VIN.

Biopsy to exclude invasive disease is mandatory prior to any topical treatment. Patients with VIN II or III should have their lesions removed. Basaloid and warty VINs may be treated with ablation on non–hair-bearing epithelium. A CO2 laser is typically used to remove the lesions, although some physicians perform a loop electrosurgical excision procedure.

Alternatives to surgery and laser include topical agents. 5-Fluorouracil cream, which causes a chemical desquamation of the lesion, has traditionally been used to treat VIN. It may result in significant burning, pain, inflammation, edema, and occasional painful ulcerations. Imiquimod cream is a topical immune response modifier that is FDA approved for the treatment of anogenital warts, actinic keratosis, and certain basal cell carcinomas. It has been used to treat multifocal VIN II or III in a few small pilot studies. The cream is self-administered 3 times per week for periods of 6 to 34 weeks.

In this case, the patient was referred for treatment of the VIN and given 2 g of oral metronidazole for the Trichomonas infection. She was advised to inform her most recent sexual partner about the Trichomonas infection so that he might receive treatment. Testing for other sexually transmitted diseases was negative.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:519-524.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP recognized the white areas as leukoplakia suggestive of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Punch biopsies showed moderate vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia II (VIN II) along with associated human papillomavirus (HPV) changes.

More than 50% of patients presenting with vulvar dysplasia have no symptoms. When symptoms are present, pruritus is the most common one. Unlike cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, VIN is usually multifocal. The most common locations include the interlabial grooves, posterior fourchette, and the perineum. Since VIN can appear warty, lesions that are diagnosed as condyloma (as was the case with this patient) and that don’t respond to conservative therapy should be biopsied to rule out VIN.

Biopsy to exclude invasive disease is mandatory prior to any topical treatment. Patients with VIN II or III should have their lesions removed. Basaloid and warty VINs may be treated with ablation on non–hair-bearing epithelium. A CO2 laser is typically used to remove the lesions, although some physicians perform a loop electrosurgical excision procedure.

Alternatives to surgery and laser include topical agents. 5-Fluorouracil cream, which causes a chemical desquamation of the lesion, has traditionally been used to treat VIN. It may result in significant burning, pain, inflammation, edema, and occasional painful ulcerations. Imiquimod cream is a topical immune response modifier that is FDA approved for the treatment of anogenital warts, actinic keratosis, and certain basal cell carcinomas. It has been used to treat multifocal VIN II or III in a few small pilot studies. The cream is self-administered 3 times per week for periods of 6 to 34 weeks.

In this case, the patient was referred for treatment of the VIN and given 2 g of oral metronidazole for the Trichomonas infection. She was advised to inform her most recent sexual partner about the Trichomonas infection so that he might receive treatment. Testing for other sexually transmitted diseases was negative.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:519-524.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Bright red cervix

There weren’t any suspicious areas during the colposcopic examination and wet prep was normal; the FP concluded that this was an ectropion.

This patient’s ectropion was a variation of normal due to her young age and exposure to oral contraceptives. The Pap smear was sent along with screening tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea; all tests came back normal.

Ectropion is common in adolescents, pregnant women, and those taking estrogen-containing contraceptives. In some women, the juvenile type transformation zone persists into adulthood, or is present after trauma or childbirth, and is termed an ectropion. It has a reddish appearance that is similar to granulation tissue. It may contain gland openings, nabothian cysts, and islands of columnar epithelium surrounded by metaplastic squamous epithelium. Although usually asymptomatic, vaginal discharge and postcoital bleeding may occur.

An ectropion may be treated with ablation if significant discharge or postcoital bleeding is present after dysplasia and cancer have been ruled out.

Photo courtesy of EJ Mayeaux, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Colposcopy–normal and noncancerous findings. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:525-529.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

There weren’t any suspicious areas during the colposcopic examination and wet prep was normal; the FP concluded that this was an ectropion.

This patient’s ectropion was a variation of normal due to her young age and exposure to oral contraceptives. The Pap smear was sent along with screening tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea; all tests came back normal.

Ectropion is common in adolescents, pregnant women, and those taking estrogen-containing contraceptives. In some women, the juvenile type transformation zone persists into adulthood, or is present after trauma or childbirth, and is termed an ectropion. It has a reddish appearance that is similar to granulation tissue. It may contain gland openings, nabothian cysts, and islands of columnar epithelium surrounded by metaplastic squamous epithelium. Although usually asymptomatic, vaginal discharge and postcoital bleeding may occur.

An ectropion may be treated with ablation if significant discharge or postcoital bleeding is present after dysplasia and cancer have been ruled out.

Photo courtesy of EJ Mayeaux, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Colposcopy–normal and noncancerous findings. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:525-529.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

There weren’t any suspicious areas during the colposcopic examination and wet prep was normal; the FP concluded that this was an ectropion.

This patient’s ectropion was a variation of normal due to her young age and exposure to oral contraceptives. The Pap smear was sent along with screening tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea; all tests came back normal.

Ectropion is common in adolescents, pregnant women, and those taking estrogen-containing contraceptives. In some women, the juvenile type transformation zone persists into adulthood, or is present after trauma or childbirth, and is termed an ectropion. It has a reddish appearance that is similar to granulation tissue. It may contain gland openings, nabothian cysts, and islands of columnar epithelium surrounded by metaplastic squamous epithelium. Although usually asymptomatic, vaginal discharge and postcoital bleeding may occur.

An ectropion may be treated with ablation if significant discharge or postcoital bleeding is present after dysplasia and cancer have been ruled out.

Photo courtesy of EJ Mayeaux, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Colposcopy–normal and noncancerous findings. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:525-529.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Postcoital spotting

The FP diagnosed an endocervical polyp with atrophic changes to the mucosa of the vulva and cervix.

Endocervical polyps are the most common benign neoplasms of the uterine cervix in women in their 40s to 60s. They are found incidentally during pelvic exams and are usually asymptomatic, but may cause vaginal discharge or postcoital spotting.

Treatment for cervical polyps involves removing them by twisting them with ringed forceps. Smaller polyps may be removed with colposcopy biopsy forceps. Polyps with a thick stalk may require surgical or electrosurgical removal. If polyps are removed after a recently abnormal Pap smear, they should be sent for analysis as dysplasia may be found.

In this case, the patient’s endocervical polyp was removed with ring forceps. There were no complications and minimal bleeding. She declined the short course of topical estrogen cream for the atrophic changes but agreed to follow up if any additional vaginal bleeding occurred. Abstinence from sexual intercourse was recommended for 2 weeks so that the cervix could heal.

Photo courtesy of EJ Mayeaux, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Colposcopy–normal and noncancerous findings. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:525-529.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed an endocervical polyp with atrophic changes to the mucosa of the vulva and cervix.

Endocervical polyps are the most common benign neoplasms of the uterine cervix in women in their 40s to 60s. They are found incidentally during pelvic exams and are usually asymptomatic, but may cause vaginal discharge or postcoital spotting.

Treatment for cervical polyps involves removing them by twisting them with ringed forceps. Smaller polyps may be removed with colposcopy biopsy forceps. Polyps with a thick stalk may require surgical or electrosurgical removal. If polyps are removed after a recently abnormal Pap smear, they should be sent for analysis as dysplasia may be found.

In this case, the patient’s endocervical polyp was removed with ring forceps. There were no complications and minimal bleeding. She declined the short course of topical estrogen cream for the atrophic changes but agreed to follow up if any additional vaginal bleeding occurred. Abstinence from sexual intercourse was recommended for 2 weeks so that the cervix could heal.

Photo courtesy of EJ Mayeaux, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Colposcopy–normal and noncancerous findings. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:525-529.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed an endocervical polyp with atrophic changes to the mucosa of the vulva and cervix.

Endocervical polyps are the most common benign neoplasms of the uterine cervix in women in their 40s to 60s. They are found incidentally during pelvic exams and are usually asymptomatic, but may cause vaginal discharge or postcoital spotting.

Treatment for cervical polyps involves removing them by twisting them with ringed forceps. Smaller polyps may be removed with colposcopy biopsy forceps. Polyps with a thick stalk may require surgical or electrosurgical removal. If polyps are removed after a recently abnormal Pap smear, they should be sent for analysis as dysplasia may be found.

In this case, the patient’s endocervical polyp was removed with ring forceps. There were no complications and minimal bleeding. She declined the short course of topical estrogen cream for the atrophic changes but agreed to follow up if any additional vaginal bleeding occurred. Abstinence from sexual intercourse was recommended for 2 weeks so that the cervix could heal.

Photo courtesy of EJ Mayeaux, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Colposcopy–normal and noncancerous findings. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:525-529.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Red, tender nipple

The FP diagnosed mastitis with a probable abscess in this patient. Mastitis is seen in up to 3% of lactating women. Mastitis is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species, and Escherichia coli. Recurrent mastitis can result from poor selection or incomplete use of antibiotic therapy, or failure to resolve underlying lactation management problems. Mastitis recurring in the same location—or not responding to appropriate therapy—may indicate the presence of breast cancer.

Breast abscess is an uncommon problem in breastfeeding women, with an incidence of less than 1%. A breast abscess and mastitis unrelated to pregnancy and breastfeeding can occur in older women.

In this case, the FP recommended incision and drainage because of the localized area of fluctuance. After the area was drained, purulence was expressed, and the wound was packed.

The patient was started on cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days to treat the surrounding cellulitis. She was seen for follow-up the next day. The patient was feeling better and the wound was repacked. The wound culture grew out S. aureus sensitive to methicillin and cephalosporins and cleared fully in the following weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Breast abscess and mastitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:546-550.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed mastitis with a probable abscess in this patient. Mastitis is seen in up to 3% of lactating women. Mastitis is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species, and Escherichia coli. Recurrent mastitis can result from poor selection or incomplete use of antibiotic therapy, or failure to resolve underlying lactation management problems. Mastitis recurring in the same location—or not responding to appropriate therapy—may indicate the presence of breast cancer.

Breast abscess is an uncommon problem in breastfeeding women, with an incidence of less than 1%. A breast abscess and mastitis unrelated to pregnancy and breastfeeding can occur in older women.

In this case, the FP recommended incision and drainage because of the localized area of fluctuance. After the area was drained, purulence was expressed, and the wound was packed.

The patient was started on cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days to treat the surrounding cellulitis. She was seen for follow-up the next day. The patient was feeling better and the wound was repacked. The wound culture grew out S. aureus sensitive to methicillin and cephalosporins and cleared fully in the following weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Breast abscess and mastitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:546-550.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP diagnosed mastitis with a probable abscess in this patient. Mastitis is seen in up to 3% of lactating women. Mastitis is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species, and Escherichia coli. Recurrent mastitis can result from poor selection or incomplete use of antibiotic therapy, or failure to resolve underlying lactation management problems. Mastitis recurring in the same location—or not responding to appropriate therapy—may indicate the presence of breast cancer.

Breast abscess is an uncommon problem in breastfeeding women, with an incidence of less than 1%. A breast abscess and mastitis unrelated to pregnancy and breastfeeding can occur in older women.

In this case, the FP recommended incision and drainage because of the localized area of fluctuance. After the area was drained, purulence was expressed, and the wound was packed.

The patient was started on cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days to treat the surrounding cellulitis. She was seen for follow-up the next day. The patient was feeling better and the wound was repacked. The wound culture grew out S. aureus sensitive to methicillin and cephalosporins and cleared fully in the following weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Breast abscess and mastitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:546-550.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Painful recurrent toe ulcers

Lesional biopsies revealed that the patient had osteoma cutis, a skin condition in which bone ossification occurs within the dermis. It has an incidence of 1.2 to 1.7 cases per 1000 skin lesion biopsies. Sixty-eight percent of osteoma cutis cases are benign.

The primary form of osteoma cutis is associated with certain genetic disorders, such as Gardner’s syndrome and Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. It arises without a preexisting lesion.

The secondary form of osteoma cutis, which this patient had, often arises within a cancerous lesion or chronic inflammation. Given this patient’s history of trauma followed by recurrent ulceration (which may not have completely resolved), her physicians suspected that chronic inflammation was the cause of the osteoma cutis.

The differential diagnosis includes calcinosis cutis, or deposition of insoluble calcium compounds in the skin without true bone formation. Other diagnoses to consider for non-healing or treatment-resistant ulcers include infection, vasculopathy, pyoderma gangrenosum, and malnutrition. Since the diagnosis of osteoma cutis is made primarily by pathology, suspicious lesions should be biopsied.

In this case, the patient was prescribed minocycline 100 mg BID for 14 days for the superficial wound infection, with plans to extend treatment as needed based on wound healing. She also received care at a local wound clinic for incomplete resolution of the ulceration and biopsy sites.

Adapted from: Sanchez AT, Weaver SP, Glass DA. Photo Rounds: painful toe ulcers. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:37-38.

Lesional biopsies revealed that the patient had osteoma cutis, a skin condition in which bone ossification occurs within the dermis. It has an incidence of 1.2 to 1.7 cases per 1000 skin lesion biopsies. Sixty-eight percent of osteoma cutis cases are benign.

The primary form of osteoma cutis is associated with certain genetic disorders, such as Gardner’s syndrome and Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. It arises without a preexisting lesion.

The secondary form of osteoma cutis, which this patient had, often arises within a cancerous lesion or chronic inflammation. Given this patient’s history of trauma followed by recurrent ulceration (which may not have completely resolved), her physicians suspected that chronic inflammation was the cause of the osteoma cutis.

The differential diagnosis includes calcinosis cutis, or deposition of insoluble calcium compounds in the skin without true bone formation. Other diagnoses to consider for non-healing or treatment-resistant ulcers include infection, vasculopathy, pyoderma gangrenosum, and malnutrition. Since the diagnosis of osteoma cutis is made primarily by pathology, suspicious lesions should be biopsied.

In this case, the patient was prescribed minocycline 100 mg BID for 14 days for the superficial wound infection, with plans to extend treatment as needed based on wound healing. She also received care at a local wound clinic for incomplete resolution of the ulceration and biopsy sites.

Adapted from: Sanchez AT, Weaver SP, Glass DA. Photo Rounds: painful toe ulcers. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:37-38.

Lesional biopsies revealed that the patient had osteoma cutis, a skin condition in which bone ossification occurs within the dermis. It has an incidence of 1.2 to 1.7 cases per 1000 skin lesion biopsies. Sixty-eight percent of osteoma cutis cases are benign.

The primary form of osteoma cutis is associated with certain genetic disorders, such as Gardner’s syndrome and Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. It arises without a preexisting lesion.

The secondary form of osteoma cutis, which this patient had, often arises within a cancerous lesion or chronic inflammation. Given this patient’s history of trauma followed by recurrent ulceration (which may not have completely resolved), her physicians suspected that chronic inflammation was the cause of the osteoma cutis.

The differential diagnosis includes calcinosis cutis, or deposition of insoluble calcium compounds in the skin without true bone formation. Other diagnoses to consider for non-healing or treatment-resistant ulcers include infection, vasculopathy, pyoderma gangrenosum, and malnutrition. Since the diagnosis of osteoma cutis is made primarily by pathology, suspicious lesions should be biopsied.

In this case, the patient was prescribed minocycline 100 mg BID for 14 days for the superficial wound infection, with plans to extend treatment as needed based on wound healing. She also received care at a local wound clinic for incomplete resolution of the ulceration and biopsy sites.

Adapted from: Sanchez AT, Weaver SP, Glass DA. Photo Rounds: painful toe ulcers. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:37-38.

Well-defined macules on young girl’s forearms

A 14-year-old African American girl was brought to our clinic because she’d had a rash for 2 weeks. The girl’s mother reported that the rash had started as light red macules on her daughter’s arms that darkened overnight and disappeared slowly. The patient’s only complaint was that the rash burned. She denied using alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs. She’d had no recent illnesses, although she had recently begun taking amlodipine 10 mg for hypertension.

A physical examination revealed multiple dark circular macules with well-defined borders on the girl’s forearm (FIGURE). Concerned that the rash was an allergic reaction to the amlodipine she’d recently begun taking, we switched her prescription to lisinopril 20 mg.

Despite the switch to lisinopril, the patient had new lesions a week later at follow-up. The rash appeared as 5×5 cm erythematous macules in different stages of healing with central clearing. The girl said the lesions were painful to the touch and burned continuously, but did not itch. We referred her to a local dermatologist, who took biopsies of the lesions and referred her to a regional dermatology clinic.

Two months later, before visiting the regional dermatology clinic, the patient returned to our office. The lesions, which were now mainly 5-cm ovals with overlying blisters, had spread to the patient’s stomach and thighs. They were in various stages of healing, with one 7-cm bullous lesion located on the left arm. The patient said that other than the constant burning, she had no symptoms.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Salt and ice burns

The biopsy the local dermatologist took did not show any signs of an infectious disease. The physicians at the regional dermatology clinic recognized that the lesions were distributed only in places the patient could reach, and felt the wounds were self-inflicted. When they asked the patient about this with her mother in the room, she denied any self-injury. At the girl’s next appointment with a different physician, she was asked about self-injury without her mother in the room, and she admitted to injuring herself using the “salt and ice challenge.”

The salt and ice challenge involves putting salt on a person’s skin and then laying ice cubes on top of the salt, which can result in a form of frostbite.1,2 This “challenge” has become a dare among teens to see how long they can withstand the pain of the burn. In one case, a 12-year-old boy suffered third-degree burns in the shape of a cross on his back after withstanding the “challenge” for 20 minutes.1

Diagnosis can be challenging without an accurate history

As this case illustrates, the burns from the salt and ice challenge might be difficult to distinguish from a rash without an accurate history from a patient or caregiver. Suspect a salt/ice burn in patients who have lesions with sharply demarcated borders that may be blistered in appearance or have bullous like characteristics.3,4 Unlike most rashes, a burn typically will not itch until well into the healing process.

Also, check for blanching and fever—both of which can signal that other factors are at play. Blanching is characteristic of conditions such as drug eruptions, viral exanthems, and roseola. A fever may suggest that a rash is associated with infectious diseases, such as Lyme disease or Rocky Mountain spotted fever.3

Family support is key to helping nonsuicidal patients who self injure

Nonsuicidal self injury (NSSI)—self inflicted, deliberate, direct destruction of body tissue without conscious suicidal intent—is prevalent in up to 45% of adolescents worldwide.5,6 An Australian study that followed 1973 adolescents for one year found that low self-esteem and poor self-efficacy were prominent predictors of NSSI.6 These researchers also found that family support is important to getting patients to refrain from NSSI.6

Peer pressure is a major issue that most adolescents will face. Encourage patients to be open with you and their family about any concerns or issues they may be facing.

Our patient. She was referred to a counselor for family therapy as well as started on citalopram 20 mg for depression. Follow-up appointments were made monthly to reassess mood as well as monitor the healing of her burns. Some of the superficial burns healed completely. However, the deeper ones—where she kept up the “challenge” for longer periods of time—scarred. The large rash on her arm that had blistered ended up forming a keloid. At her 6-month follow-up appointment, she remained free of further NSSI.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Thomas, MD, UT Family Practice Center, 1100 East Third Street, Chattanooga, TN 37403; [email protected]

1. Templeton D. Boy, 12, badly injured in ‘salt-and-ice” challenge. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.post-gazette.com/neighborhoods-city/2012/06/29/Boy-12-badly-injured-in-salt-and-ice-challenge/stories/201206290188. Accessed December 5, 2014.

2. Salt and Ice Burn ‘Challenge Returns’, Luring Detroit Teens Into Dangerous Trend. The Huffington Post. December 26, 2012. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/12/26/salt-ice-burn-challenge-teens-video_n_2366619.html. Accessed December 5, 2014.

3. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part II. Diagnostic approach. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:735-739.

4. Morgan ED, Bledsoe SC, Barker J. Ambulatory management of burns. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:2015-2026.

5. Fischer G, Brunner R, Parzer P, et al. Short-term psychotherapeutic treatment in adolescents engaging in non-suicidal self-injury: a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:294.

6. Tatnell R, Kelada L, Hasking P, et al. Longitudinal analysis of adolescent NSSI: the role of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:885-896.

A 14-year-old African American girl was brought to our clinic because she’d had a rash for 2 weeks. The girl’s mother reported that the rash had started as light red macules on her daughter’s arms that darkened overnight and disappeared slowly. The patient’s only complaint was that the rash burned. She denied using alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs. She’d had no recent illnesses, although she had recently begun taking amlodipine 10 mg for hypertension.

A physical examination revealed multiple dark circular macules with well-defined borders on the girl’s forearm (FIGURE). Concerned that the rash was an allergic reaction to the amlodipine she’d recently begun taking, we switched her prescription to lisinopril 20 mg.

Despite the switch to lisinopril, the patient had new lesions a week later at follow-up. The rash appeared as 5×5 cm erythematous macules in different stages of healing with central clearing. The girl said the lesions were painful to the touch and burned continuously, but did not itch. We referred her to a local dermatologist, who took biopsies of the lesions and referred her to a regional dermatology clinic.

Two months later, before visiting the regional dermatology clinic, the patient returned to our office. The lesions, which were now mainly 5-cm ovals with overlying blisters, had spread to the patient’s stomach and thighs. They were in various stages of healing, with one 7-cm bullous lesion located on the left arm. The patient said that other than the constant burning, she had no symptoms.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Salt and ice burns

The biopsy the local dermatologist took did not show any signs of an infectious disease. The physicians at the regional dermatology clinic recognized that the lesions were distributed only in places the patient could reach, and felt the wounds were self-inflicted. When they asked the patient about this with her mother in the room, she denied any self-injury. At the girl’s next appointment with a different physician, she was asked about self-injury without her mother in the room, and she admitted to injuring herself using the “salt and ice challenge.”

The salt and ice challenge involves putting salt on a person’s skin and then laying ice cubes on top of the salt, which can result in a form of frostbite.1,2 This “challenge” has become a dare among teens to see how long they can withstand the pain of the burn. In one case, a 12-year-old boy suffered third-degree burns in the shape of a cross on his back after withstanding the “challenge” for 20 minutes.1

Diagnosis can be challenging without an accurate history

As this case illustrates, the burns from the salt and ice challenge might be difficult to distinguish from a rash without an accurate history from a patient or caregiver. Suspect a salt/ice burn in patients who have lesions with sharply demarcated borders that may be blistered in appearance or have bullous like characteristics.3,4 Unlike most rashes, a burn typically will not itch until well into the healing process.

Also, check for blanching and fever—both of which can signal that other factors are at play. Blanching is characteristic of conditions such as drug eruptions, viral exanthems, and roseola. A fever may suggest that a rash is associated with infectious diseases, such as Lyme disease or Rocky Mountain spotted fever.3

Family support is key to helping nonsuicidal patients who self injure

Nonsuicidal self injury (NSSI)—self inflicted, deliberate, direct destruction of body tissue without conscious suicidal intent—is prevalent in up to 45% of adolescents worldwide.5,6 An Australian study that followed 1973 adolescents for one year found that low self-esteem and poor self-efficacy were prominent predictors of NSSI.6 These researchers also found that family support is important to getting patients to refrain from NSSI.6

Peer pressure is a major issue that most adolescents will face. Encourage patients to be open with you and their family about any concerns or issues they may be facing.

Our patient. She was referred to a counselor for family therapy as well as started on citalopram 20 mg for depression. Follow-up appointments were made monthly to reassess mood as well as monitor the healing of her burns. Some of the superficial burns healed completely. However, the deeper ones—where she kept up the “challenge” for longer periods of time—scarred. The large rash on her arm that had blistered ended up forming a keloid. At her 6-month follow-up appointment, she remained free of further NSSI.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Thomas, MD, UT Family Practice Center, 1100 East Third Street, Chattanooga, TN 37403; [email protected]

A 14-year-old African American girl was brought to our clinic because she’d had a rash for 2 weeks. The girl’s mother reported that the rash had started as light red macules on her daughter’s arms that darkened overnight and disappeared slowly. The patient’s only complaint was that the rash burned. She denied using alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs. She’d had no recent illnesses, although she had recently begun taking amlodipine 10 mg for hypertension.

A physical examination revealed multiple dark circular macules with well-defined borders on the girl’s forearm (FIGURE). Concerned that the rash was an allergic reaction to the amlodipine she’d recently begun taking, we switched her prescription to lisinopril 20 mg.

Despite the switch to lisinopril, the patient had new lesions a week later at follow-up. The rash appeared as 5×5 cm erythematous macules in different stages of healing with central clearing. The girl said the lesions were painful to the touch and burned continuously, but did not itch. We referred her to a local dermatologist, who took biopsies of the lesions and referred her to a regional dermatology clinic.

Two months later, before visiting the regional dermatology clinic, the patient returned to our office. The lesions, which were now mainly 5-cm ovals with overlying blisters, had spread to the patient’s stomach and thighs. They were in various stages of healing, with one 7-cm bullous lesion located on the left arm. The patient said that other than the constant burning, she had no symptoms.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Salt and ice burns

The biopsy the local dermatologist took did not show any signs of an infectious disease. The physicians at the regional dermatology clinic recognized that the lesions were distributed only in places the patient could reach, and felt the wounds were self-inflicted. When they asked the patient about this with her mother in the room, she denied any self-injury. At the girl’s next appointment with a different physician, she was asked about self-injury without her mother in the room, and she admitted to injuring herself using the “salt and ice challenge.”

The salt and ice challenge involves putting salt on a person’s skin and then laying ice cubes on top of the salt, which can result in a form of frostbite.1,2 This “challenge” has become a dare among teens to see how long they can withstand the pain of the burn. In one case, a 12-year-old boy suffered third-degree burns in the shape of a cross on his back after withstanding the “challenge” for 20 minutes.1

Diagnosis can be challenging without an accurate history

As this case illustrates, the burns from the salt and ice challenge might be difficult to distinguish from a rash without an accurate history from a patient or caregiver. Suspect a salt/ice burn in patients who have lesions with sharply demarcated borders that may be blistered in appearance or have bullous like characteristics.3,4 Unlike most rashes, a burn typically will not itch until well into the healing process.

Also, check for blanching and fever—both of which can signal that other factors are at play. Blanching is characteristic of conditions such as drug eruptions, viral exanthems, and roseola. A fever may suggest that a rash is associated with infectious diseases, such as Lyme disease or Rocky Mountain spotted fever.3

Family support is key to helping nonsuicidal patients who self injure

Nonsuicidal self injury (NSSI)—self inflicted, deliberate, direct destruction of body tissue without conscious suicidal intent—is prevalent in up to 45% of adolescents worldwide.5,6 An Australian study that followed 1973 adolescents for one year found that low self-esteem and poor self-efficacy were prominent predictors of NSSI.6 These researchers also found that family support is important to getting patients to refrain from NSSI.6

Peer pressure is a major issue that most adolescents will face. Encourage patients to be open with you and their family about any concerns or issues they may be facing.

Our patient. She was referred to a counselor for family therapy as well as started on citalopram 20 mg for depression. Follow-up appointments were made monthly to reassess mood as well as monitor the healing of her burns. Some of the superficial burns healed completely. However, the deeper ones—where she kept up the “challenge” for longer periods of time—scarred. The large rash on her arm that had blistered ended up forming a keloid. At her 6-month follow-up appointment, she remained free of further NSSI.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Thomas, MD, UT Family Practice Center, 1100 East Third Street, Chattanooga, TN 37403; [email protected]

1. Templeton D. Boy, 12, badly injured in ‘salt-and-ice” challenge. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.post-gazette.com/neighborhoods-city/2012/06/29/Boy-12-badly-injured-in-salt-and-ice-challenge/stories/201206290188. Accessed December 5, 2014.

2. Salt and Ice Burn ‘Challenge Returns’, Luring Detroit Teens Into Dangerous Trend. The Huffington Post. December 26, 2012. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/12/26/salt-ice-burn-challenge-teens-video_n_2366619.html. Accessed December 5, 2014.

3. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part II. Diagnostic approach. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:735-739.

4. Morgan ED, Bledsoe SC, Barker J. Ambulatory management of burns. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:2015-2026.

5. Fischer G, Brunner R, Parzer P, et al. Short-term psychotherapeutic treatment in adolescents engaging in non-suicidal self-injury: a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:294.

6. Tatnell R, Kelada L, Hasking P, et al. Longitudinal analysis of adolescent NSSI: the role of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:885-896.

1. Templeton D. Boy, 12, badly injured in ‘salt-and-ice” challenge. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.post-gazette.com/neighborhoods-city/2012/06/29/Boy-12-badly-injured-in-salt-and-ice-challenge/stories/201206290188. Accessed December 5, 2014.