User login

Multiple Facial Papules

The Diagnosis: Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

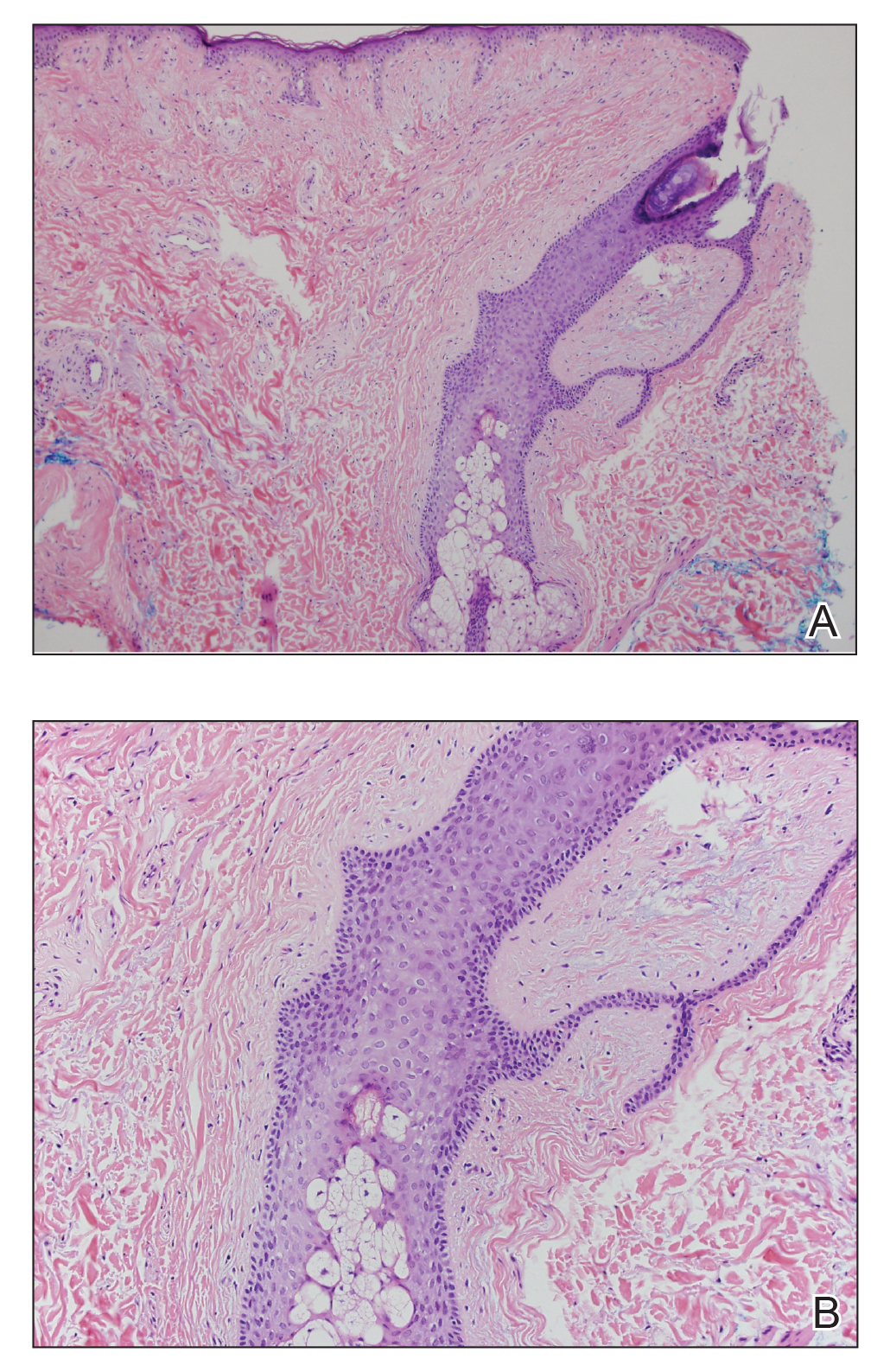

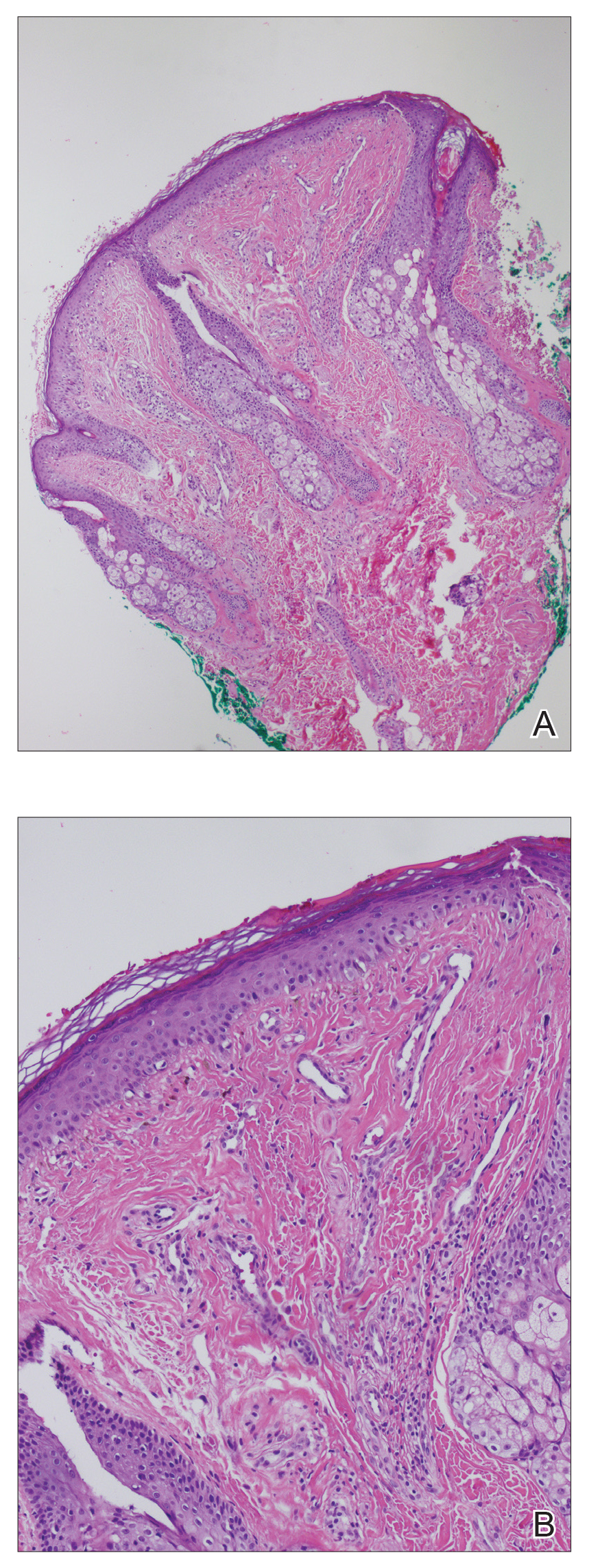

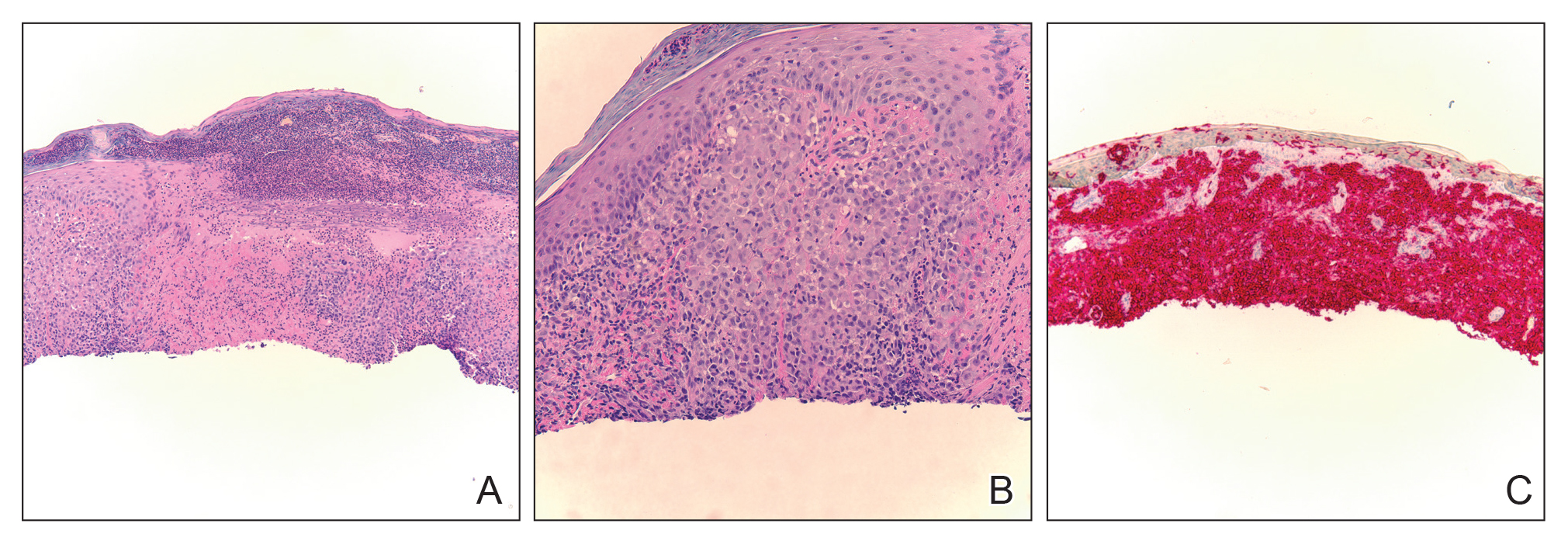

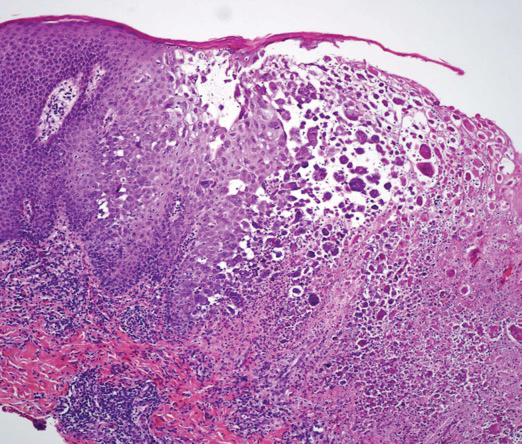

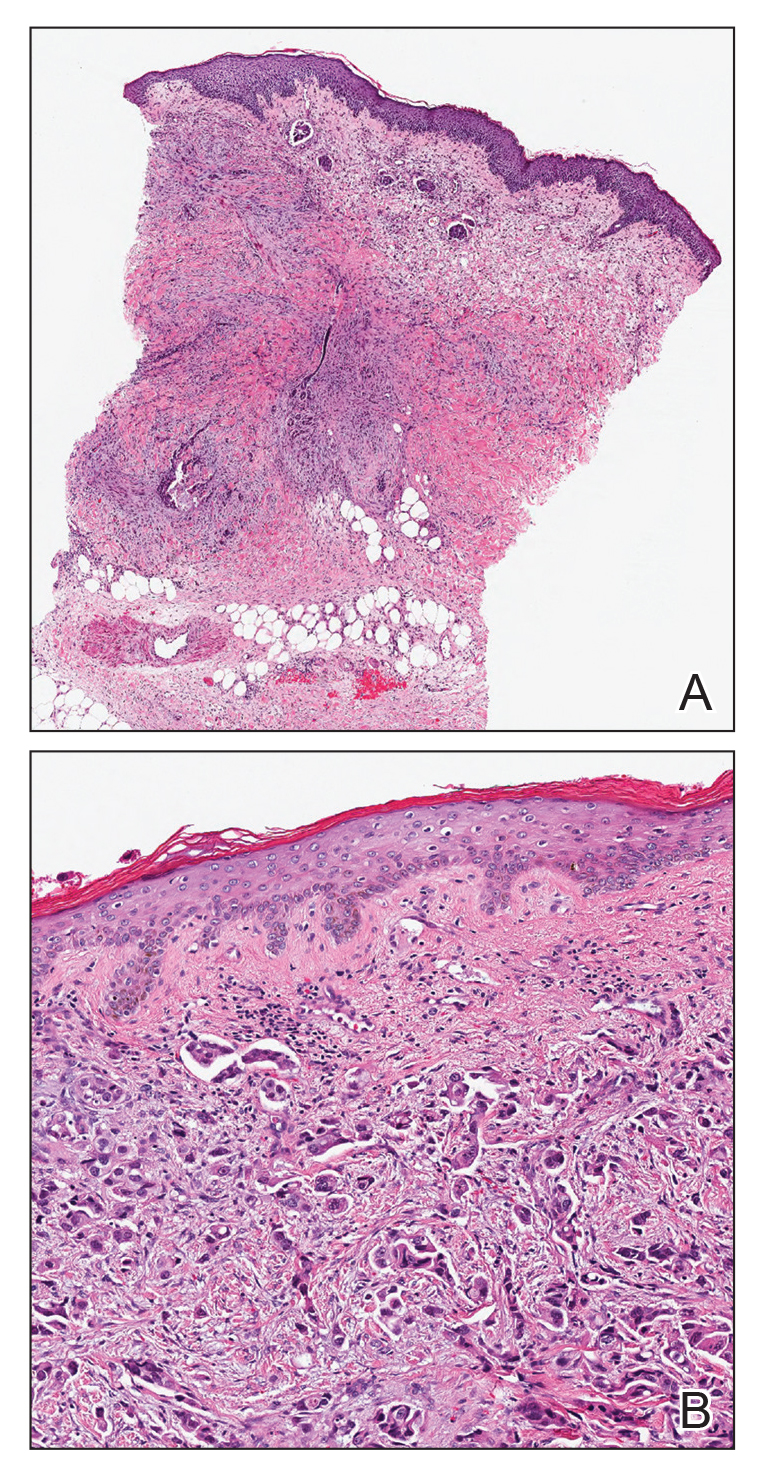

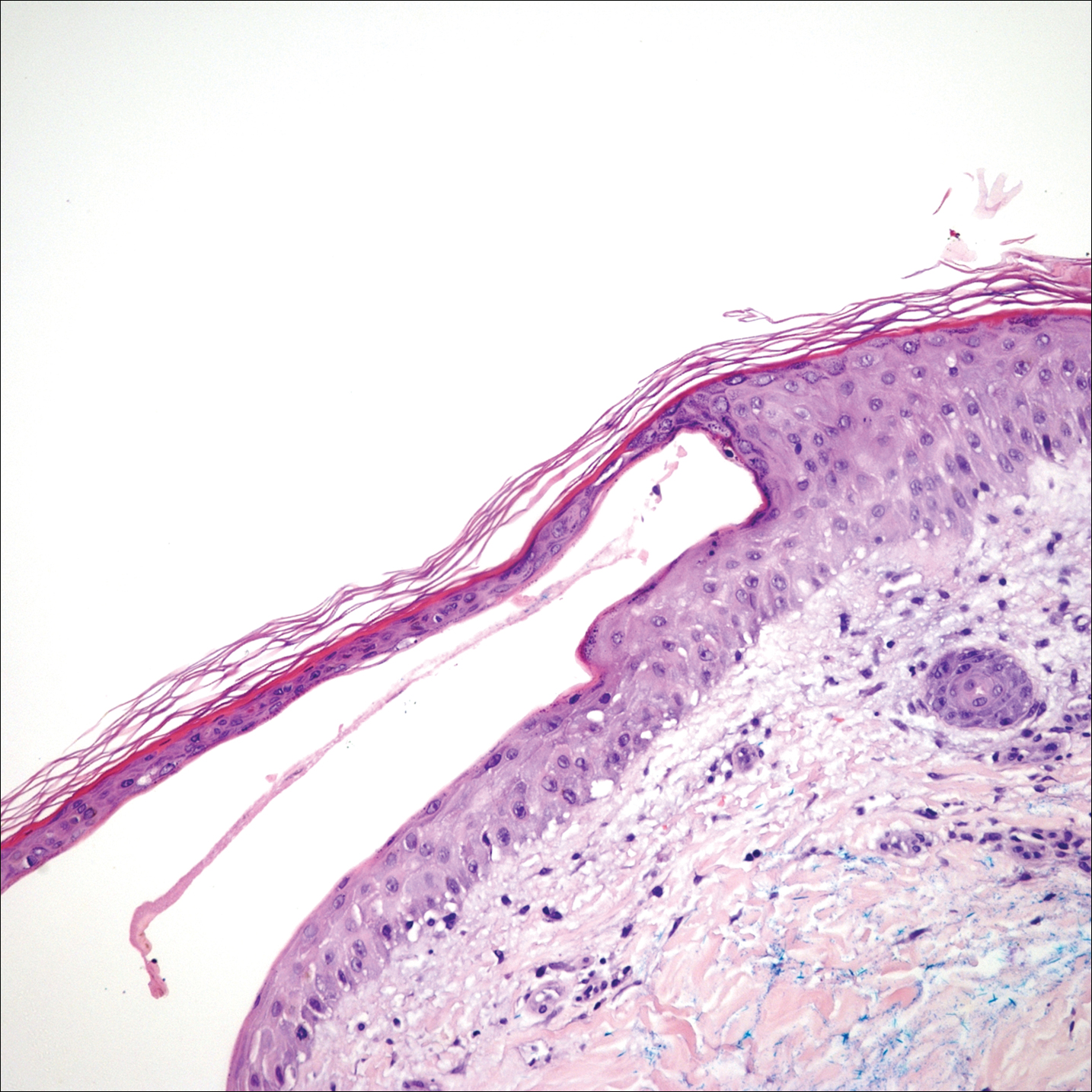

Histopathologic examination revealed a collection of bland spindle cells with perifollicular fibrosis consistent with a fibrofolliculoma, confirming the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (Figure). Cosmetic treatment with ablative therapy was offered, but the patient declined.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the folliculin gene, FLCN, on chromosome arm 17p11.2.1 Cutaneous findings include benign follicular hamartomas, such as fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas. Angiofibromas, perifollicular fibromas, oral papillomas, and acrochordons also can be present.1 Cutaneous lesions usually appear on the head and neck in the third decade of life.

Patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome are at an increased risk for pneumothorax and renal cancer, specifically hybrid oncocytic-chromophobe renal cell carcinomas.2 In a study of 89 patients with a FLCN mutation, 90% (80/89) of patients had cutaneous lesions, 84% (34/89) had pulmonary cysts, and 34% (30/89) had kidney tumors. Affected individuals were at a higher risk for pneumothorax and kidney tumors if there was a family history of these tumors.2

Proposed diagnostic criteria include any 1 of the following: 2 or more skin lesions clinically consistent with fibrofolliculomas and 1 histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma; multiple bilateral pulmonary cysts in the basilar lung with or without pneumothorax before 40 years of age; bilateral multifocal chromophobe renal carcinomas or hybrid oncocytic tumors; combination of cutaneous, pulmonary, or renal manifestation in the patient and family; or a FLCN mutation.3

Current recommendations for the workup of a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome include referral to genetic counseling for the patient and family, a baseline computed tomography of the chest to evaluate for pulmonary cysts, and gadolinium-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging starting at 20 years of age and repeated every 3 to 4 years to screen for renal tumors.1 Pulmonary function tests can be considered if the patient is symptomatic or has a high cyst burden. Patients should be advised against smoking and scuba diving.

The differential diagnosis of multiple facial papules includes Cowden syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, and Muir-Torre syndrome. Cowden syndrome is caused by a mutation in the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene, PTEN.4 The characteristic cutaneous findings on the face are trichilemmomas, which appear as flesh-colored papules that may have a verrucous surface.

Tuberous sclerosis is caused by mutations in hamartin (TSC1) or tuberin (TSC2). Angiofibromas are most commonly found on the face and appear as flesh-colored to red-brown papules. Fibrous plaques, periungual fibromas, gingival fibromas, hypopigmented macules, and connective tissue nevi also are found in tuberous sclerosis.5

Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by a mutation in the CYLD lysine 63 deubiquitinase gene, CYLD. Trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas are caused by the CYLD mutation and appear on the head and neck. Trichoepitheliomas are flesh-colored to pink papules found on the face, often concentrated in the nasolabial folds.6 Cylindromas and spiradenomas are flesh-colored to pink papules or nodules most commonly found on the scalp.6

Muir-Torre syndrome is caused by a mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2 and/or MLH1.7 Sebaceous neoplasms, including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and less frequently sebaceous carcinomas, are characteristic cutaneous findings and appear as pink to yellow papules commonly found on the head and neck.

Careful history taking, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis are important in recognizing the features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Accurate and timely diagnosis is essential for the appropriate care of patients and their families, given the syndrome's systemic implications.

- Gupta N, Sunwoo BY, Kotloff RM. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:475-486.

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, et al. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321-331.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:558-569.

- Marsh D, Kum JB, Lunetta KL, et al. PTEN mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggest a single entity with Cowden syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1461-1472.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Uemura M, Fujita K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: recent advances in manifestations and therapy. Int J Urol. 2017;24:681-691.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Mahalingam M. MSH6, Past and present and Muir-Torre syndrome--connecting the dots. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:239-249.

The Diagnosis: Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

Histopathologic examination revealed a collection of bland spindle cells with perifollicular fibrosis consistent with a fibrofolliculoma, confirming the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (Figure). Cosmetic treatment with ablative therapy was offered, but the patient declined.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the folliculin gene, FLCN, on chromosome arm 17p11.2.1 Cutaneous findings include benign follicular hamartomas, such as fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas. Angiofibromas, perifollicular fibromas, oral papillomas, and acrochordons also can be present.1 Cutaneous lesions usually appear on the head and neck in the third decade of life.

Patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome are at an increased risk for pneumothorax and renal cancer, specifically hybrid oncocytic-chromophobe renal cell carcinomas.2 In a study of 89 patients with a FLCN mutation, 90% (80/89) of patients had cutaneous lesions, 84% (34/89) had pulmonary cysts, and 34% (30/89) had kidney tumors. Affected individuals were at a higher risk for pneumothorax and kidney tumors if there was a family history of these tumors.2

Proposed diagnostic criteria include any 1 of the following: 2 or more skin lesions clinically consistent with fibrofolliculomas and 1 histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma; multiple bilateral pulmonary cysts in the basilar lung with or without pneumothorax before 40 years of age; bilateral multifocal chromophobe renal carcinomas or hybrid oncocytic tumors; combination of cutaneous, pulmonary, or renal manifestation in the patient and family; or a FLCN mutation.3

Current recommendations for the workup of a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome include referral to genetic counseling for the patient and family, a baseline computed tomography of the chest to evaluate for pulmonary cysts, and gadolinium-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging starting at 20 years of age and repeated every 3 to 4 years to screen for renal tumors.1 Pulmonary function tests can be considered if the patient is symptomatic or has a high cyst burden. Patients should be advised against smoking and scuba diving.

The differential diagnosis of multiple facial papules includes Cowden syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, and Muir-Torre syndrome. Cowden syndrome is caused by a mutation in the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene, PTEN.4 The characteristic cutaneous findings on the face are trichilemmomas, which appear as flesh-colored papules that may have a verrucous surface.

Tuberous sclerosis is caused by mutations in hamartin (TSC1) or tuberin (TSC2). Angiofibromas are most commonly found on the face and appear as flesh-colored to red-brown papules. Fibrous plaques, periungual fibromas, gingival fibromas, hypopigmented macules, and connective tissue nevi also are found in tuberous sclerosis.5

Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by a mutation in the CYLD lysine 63 deubiquitinase gene, CYLD. Trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas are caused by the CYLD mutation and appear on the head and neck. Trichoepitheliomas are flesh-colored to pink papules found on the face, often concentrated in the nasolabial folds.6 Cylindromas and spiradenomas are flesh-colored to pink papules or nodules most commonly found on the scalp.6

Muir-Torre syndrome is caused by a mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2 and/or MLH1.7 Sebaceous neoplasms, including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and less frequently sebaceous carcinomas, are characteristic cutaneous findings and appear as pink to yellow papules commonly found on the head and neck.

Careful history taking, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis are important in recognizing the features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Accurate and timely diagnosis is essential for the appropriate care of patients and their families, given the syndrome's systemic implications.

The Diagnosis: Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

Histopathologic examination revealed a collection of bland spindle cells with perifollicular fibrosis consistent with a fibrofolliculoma, confirming the diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (Figure). Cosmetic treatment with ablative therapy was offered, but the patient declined.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the folliculin gene, FLCN, on chromosome arm 17p11.2.1 Cutaneous findings include benign follicular hamartomas, such as fibrofolliculomas and trichodiscomas. Angiofibromas, perifollicular fibromas, oral papillomas, and acrochordons also can be present.1 Cutaneous lesions usually appear on the head and neck in the third decade of life.

Patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome are at an increased risk for pneumothorax and renal cancer, specifically hybrid oncocytic-chromophobe renal cell carcinomas.2 In a study of 89 patients with a FLCN mutation, 90% (80/89) of patients had cutaneous lesions, 84% (34/89) had pulmonary cysts, and 34% (30/89) had kidney tumors. Affected individuals were at a higher risk for pneumothorax and kidney tumors if there was a family history of these tumors.2

Proposed diagnostic criteria include any 1 of the following: 2 or more skin lesions clinically consistent with fibrofolliculomas and 1 histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma; multiple bilateral pulmonary cysts in the basilar lung with or without pneumothorax before 40 years of age; bilateral multifocal chromophobe renal carcinomas or hybrid oncocytic tumors; combination of cutaneous, pulmonary, or renal manifestation in the patient and family; or a FLCN mutation.3

Current recommendations for the workup of a patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome include referral to genetic counseling for the patient and family, a baseline computed tomography of the chest to evaluate for pulmonary cysts, and gadolinium-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging starting at 20 years of age and repeated every 3 to 4 years to screen for renal tumors.1 Pulmonary function tests can be considered if the patient is symptomatic or has a high cyst burden. Patients should be advised against smoking and scuba diving.

The differential diagnosis of multiple facial papules includes Cowden syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, and Muir-Torre syndrome. Cowden syndrome is caused by a mutation in the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene, PTEN.4 The characteristic cutaneous findings on the face are trichilemmomas, which appear as flesh-colored papules that may have a verrucous surface.

Tuberous sclerosis is caused by mutations in hamartin (TSC1) or tuberin (TSC2). Angiofibromas are most commonly found on the face and appear as flesh-colored to red-brown papules. Fibrous plaques, periungual fibromas, gingival fibromas, hypopigmented macules, and connective tissue nevi also are found in tuberous sclerosis.5

Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by a mutation in the CYLD lysine 63 deubiquitinase gene, CYLD. Trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas are caused by the CYLD mutation and appear on the head and neck. Trichoepitheliomas are flesh-colored to pink papules found on the face, often concentrated in the nasolabial folds.6 Cylindromas and spiradenomas are flesh-colored to pink papules or nodules most commonly found on the scalp.6

Muir-Torre syndrome is caused by a mutation in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2 and/or MLH1.7 Sebaceous neoplasms, including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and less frequently sebaceous carcinomas, are characteristic cutaneous findings and appear as pink to yellow papules commonly found on the head and neck.

Careful history taking, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis are important in recognizing the features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Accurate and timely diagnosis is essential for the appropriate care of patients and their families, given the syndrome's systemic implications.

- Gupta N, Sunwoo BY, Kotloff RM. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:475-486.

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, et al. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321-331.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:558-569.

- Marsh D, Kum JB, Lunetta KL, et al. PTEN mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggest a single entity with Cowden syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1461-1472.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Uemura M, Fujita K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: recent advances in manifestations and therapy. Int J Urol. 2017;24:681-691.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Mahalingam M. MSH6, Past and present and Muir-Torre syndrome--connecting the dots. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:239-249.

- Gupta N, Sunwoo BY, Kotloff RM. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:475-486.

- Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, et al. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45:321-331.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:558-569.

- Marsh D, Kum JB, Lunetta KL, et al. PTEN mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggest a single entity with Cowden syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1461-1472.

- Wataya-Kaneda M, Uemura M, Fujita K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: recent advances in manifestations and therapy. Int J Urol. 2017;24:681-691.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Mahalingam M. MSH6, Past and present and Muir-Torre syndrome--connecting the dots. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:239-249.

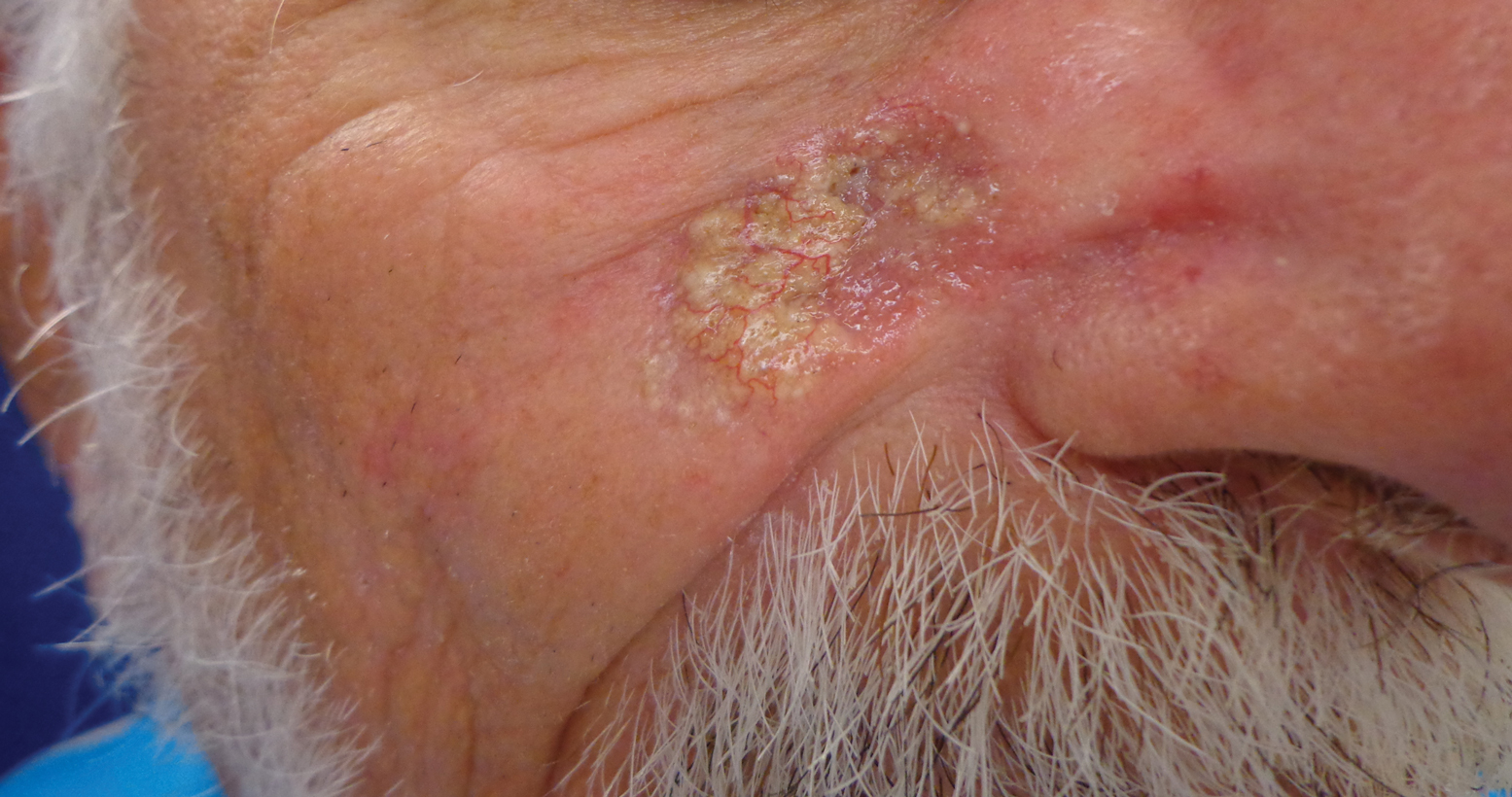

A 50-year-old man presented with facial papules on the cheeks that had appeared approximately 1.5 years prior and gradually spread over the face and neck. They were occasionally pruritic but otherwise were asymptomatic. His mother and brother reportedly had similar clinical findings. Family history was notable for a maternal uncle who had died in his 30s of an unknown type of renal cancer. Physical examination revealed innumerable white-gray papules that measured 1 to 5 mm and were scattered across the face and neck. Punch biopsies were obtained. Computed tomography of the chest showed multiple bibasilar pulmonary cysts. Magnetic resonance imaging was negative for renal tumors.

New Plaques Arising at Site of Previously Excised Basal Cell Carcinoma

The Diagnosis: Actinic Comedonal Plaque

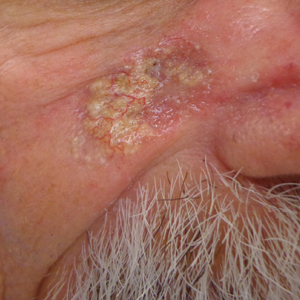

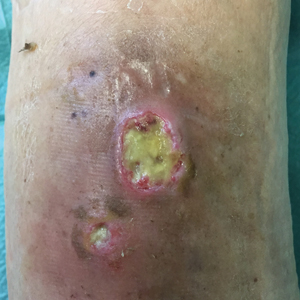

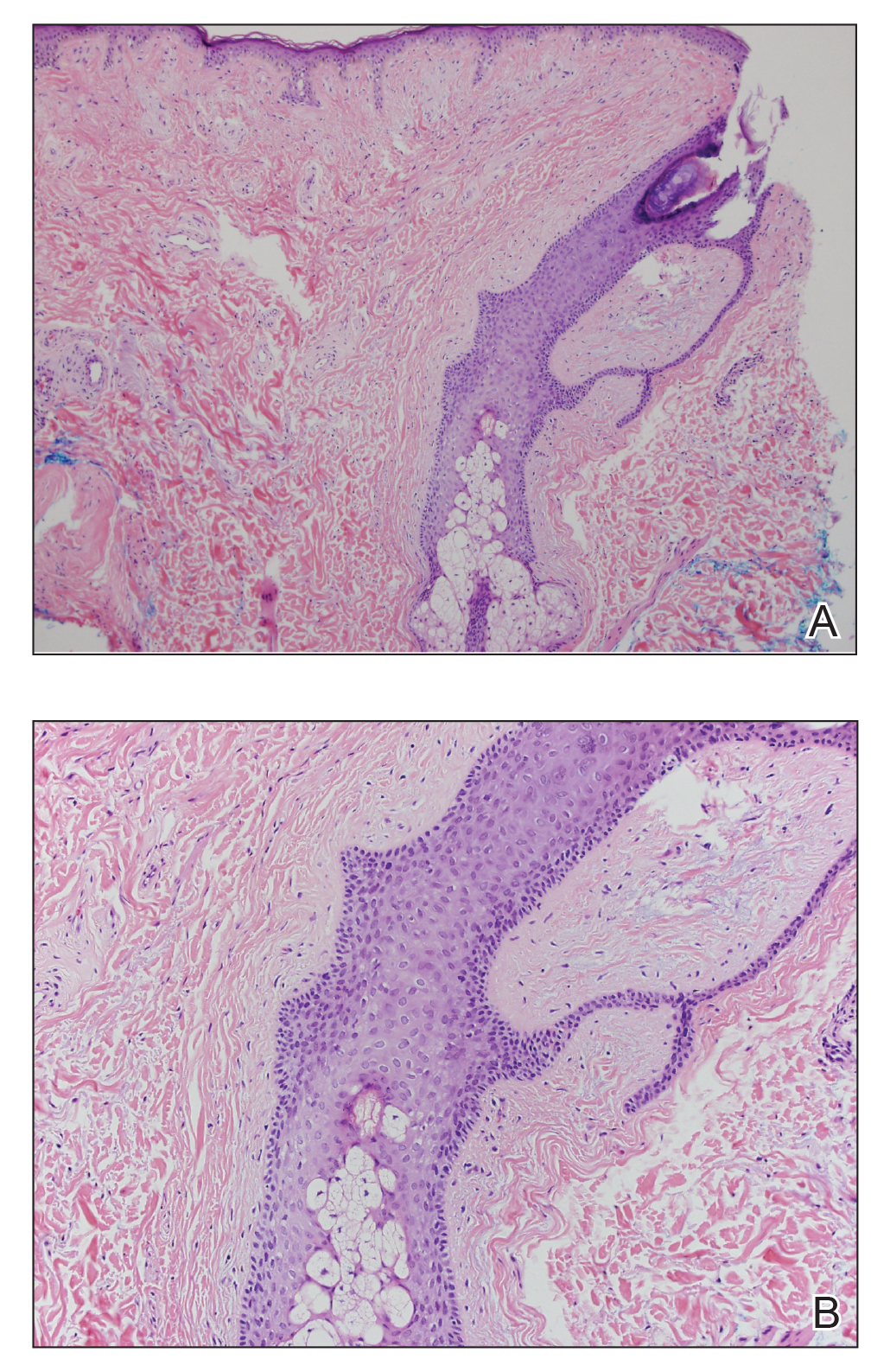

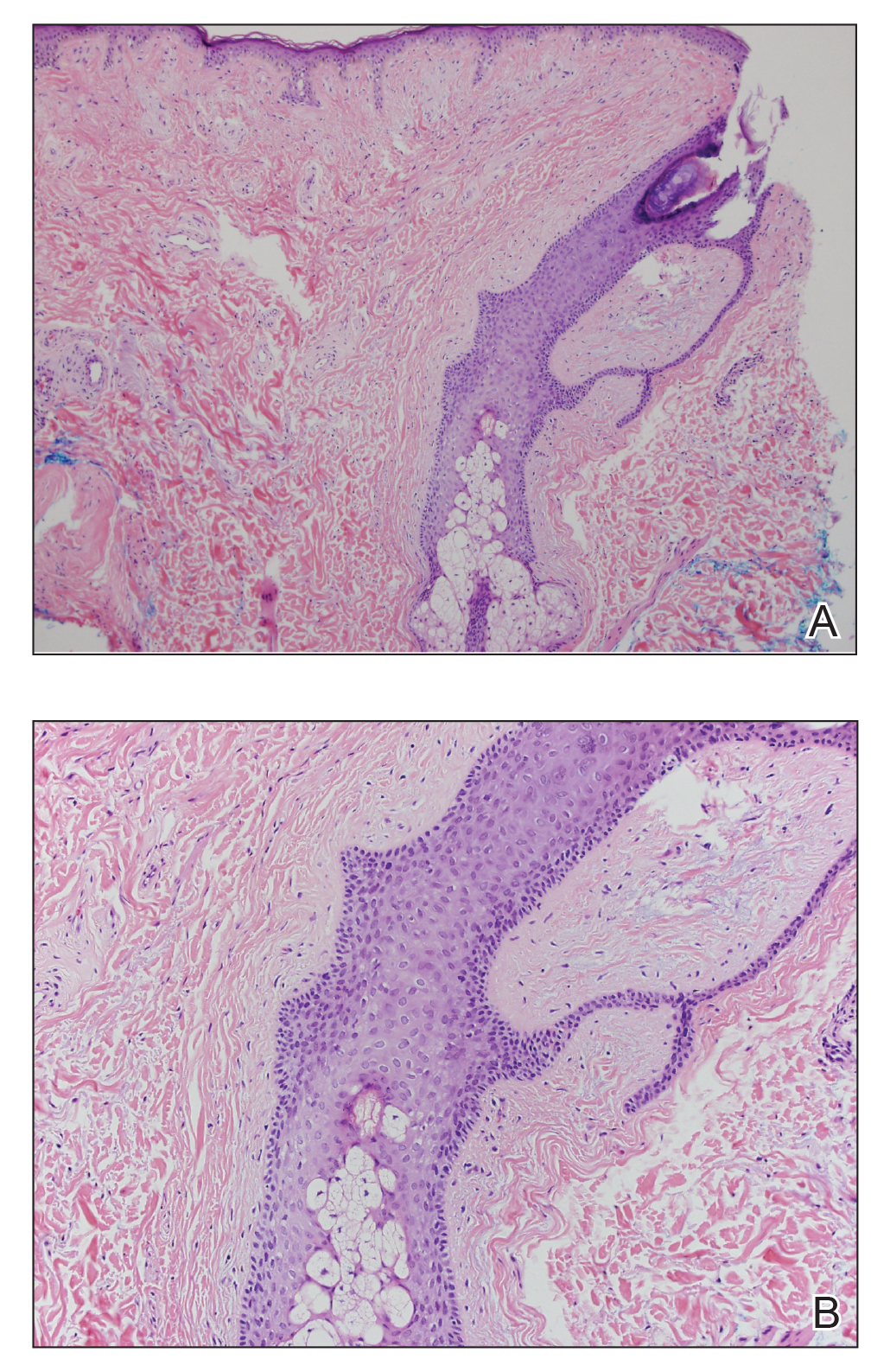

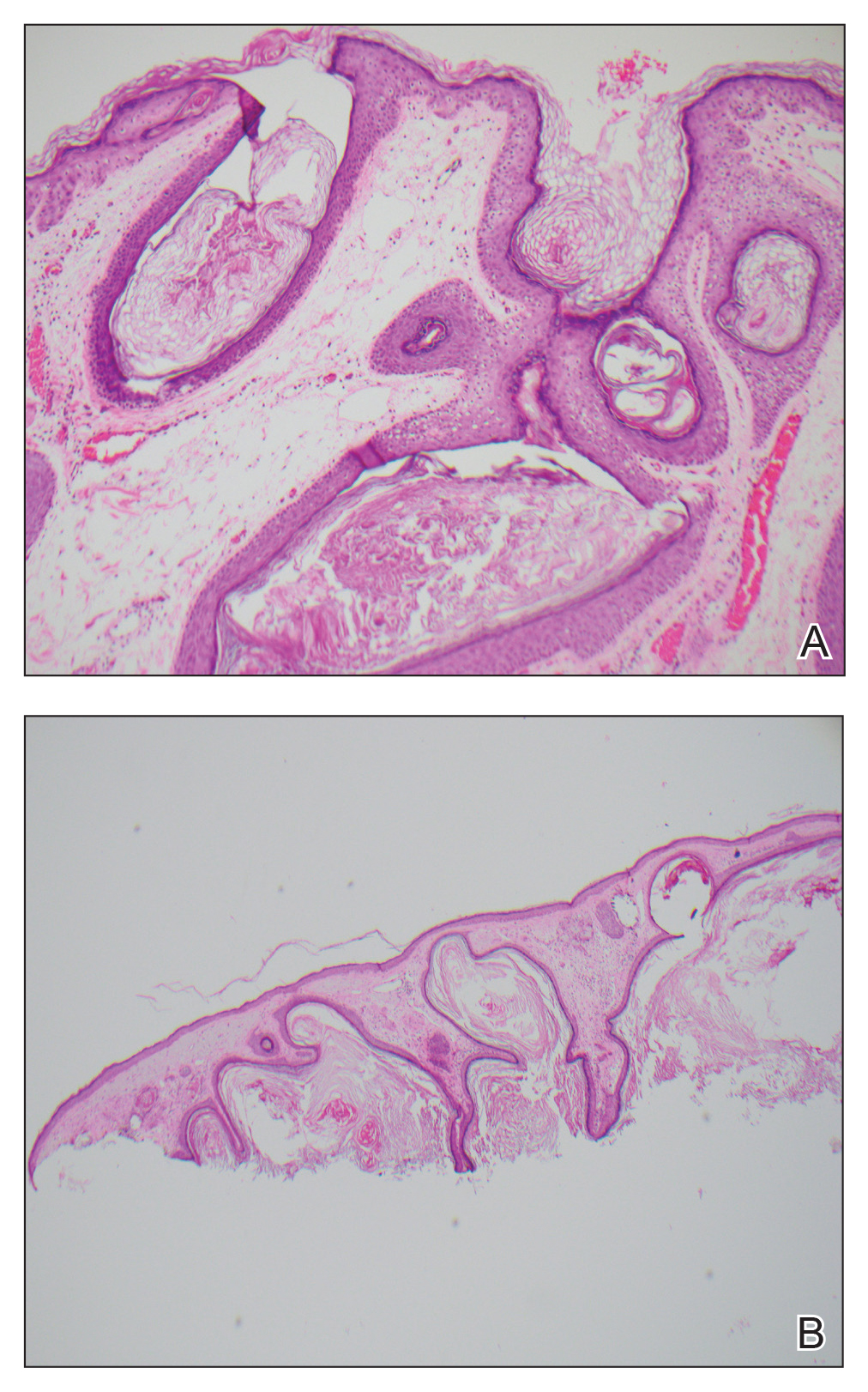

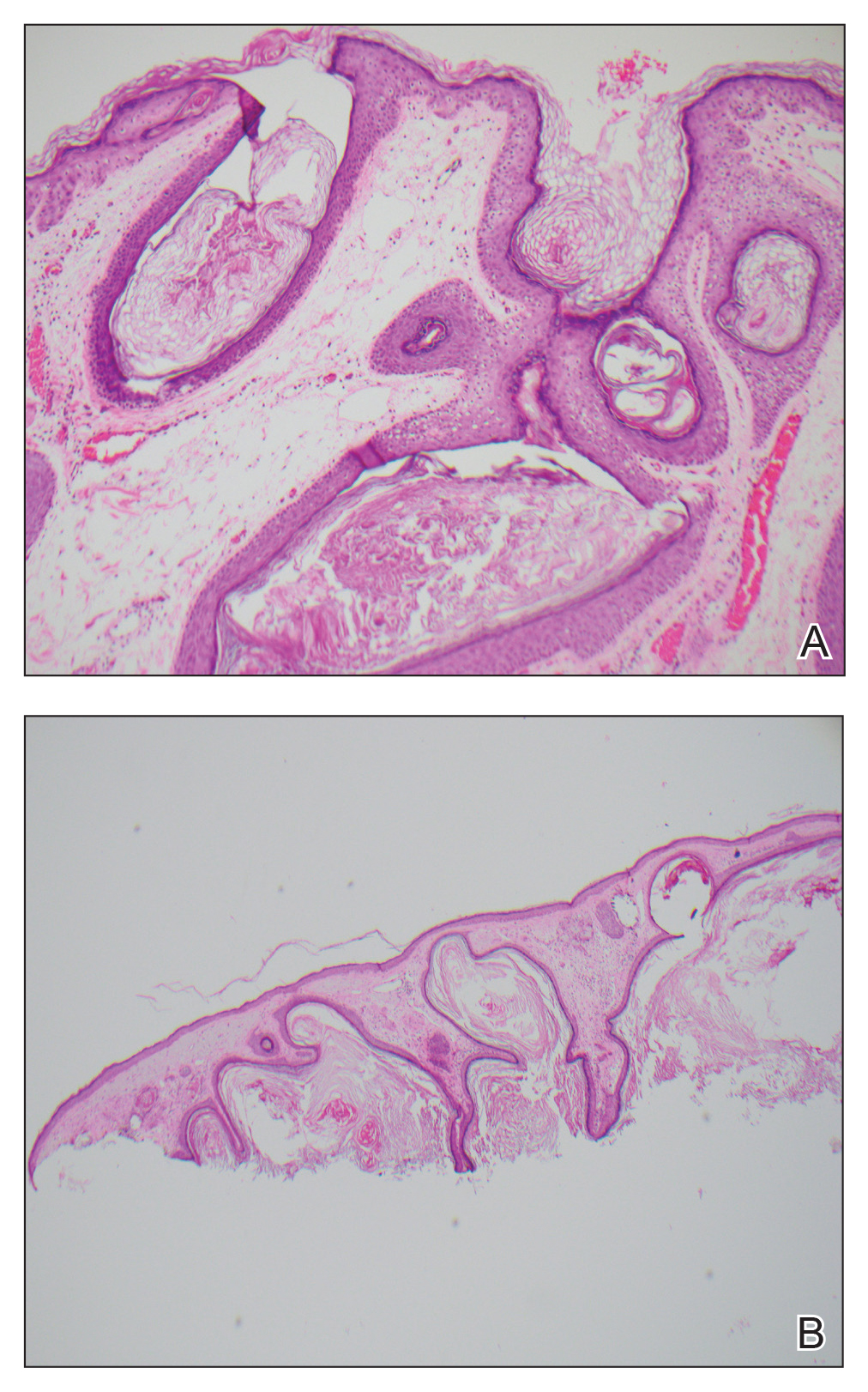

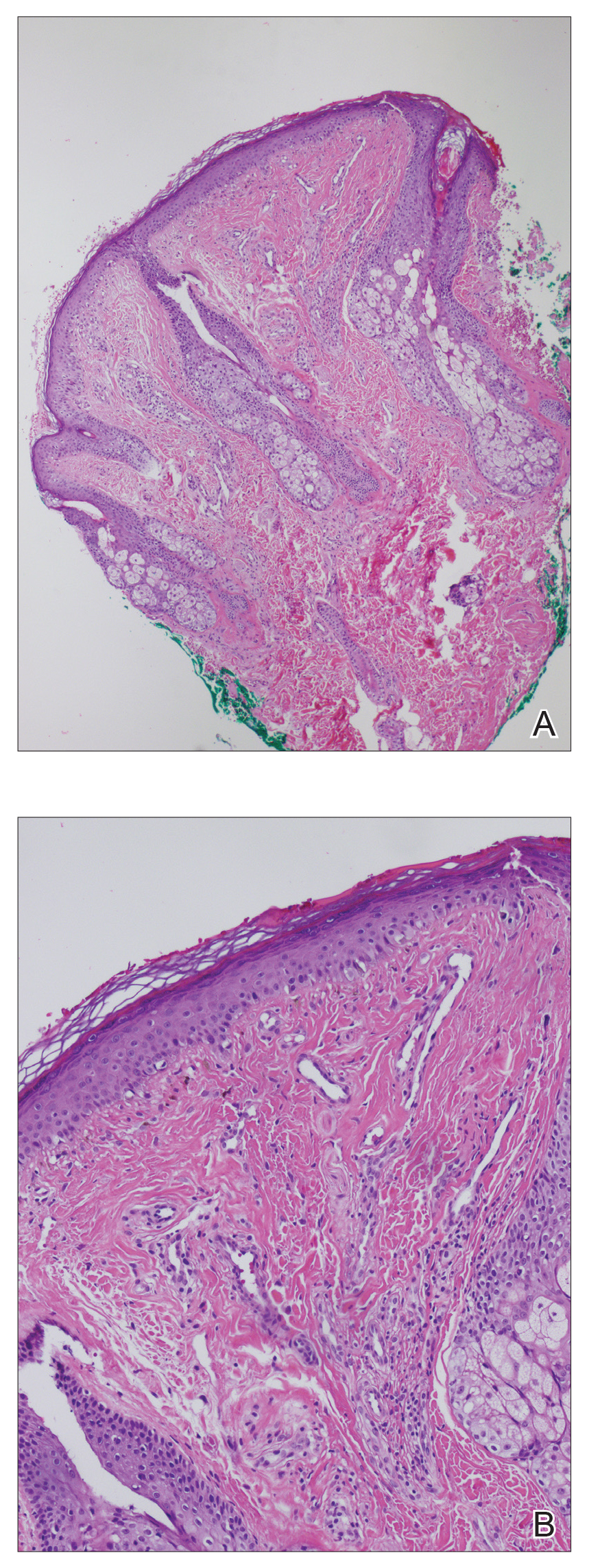

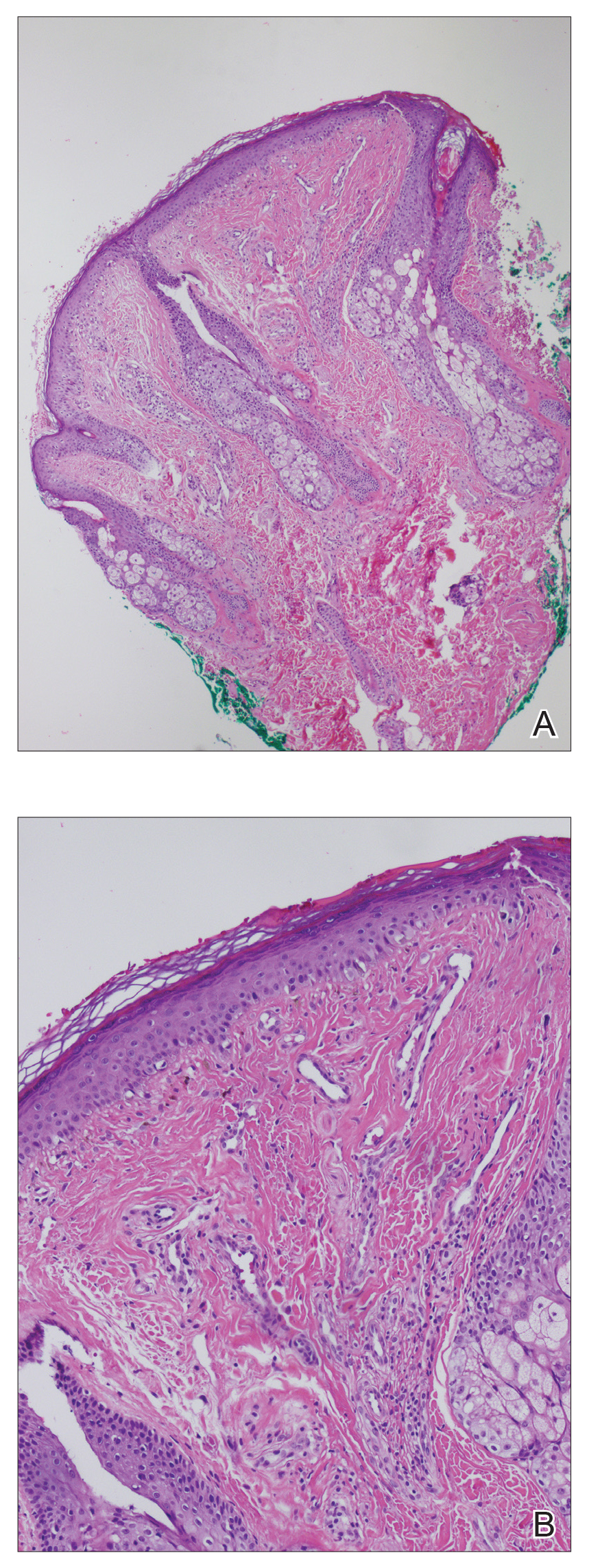

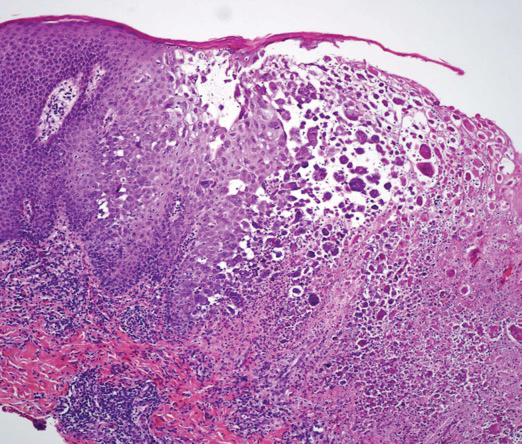

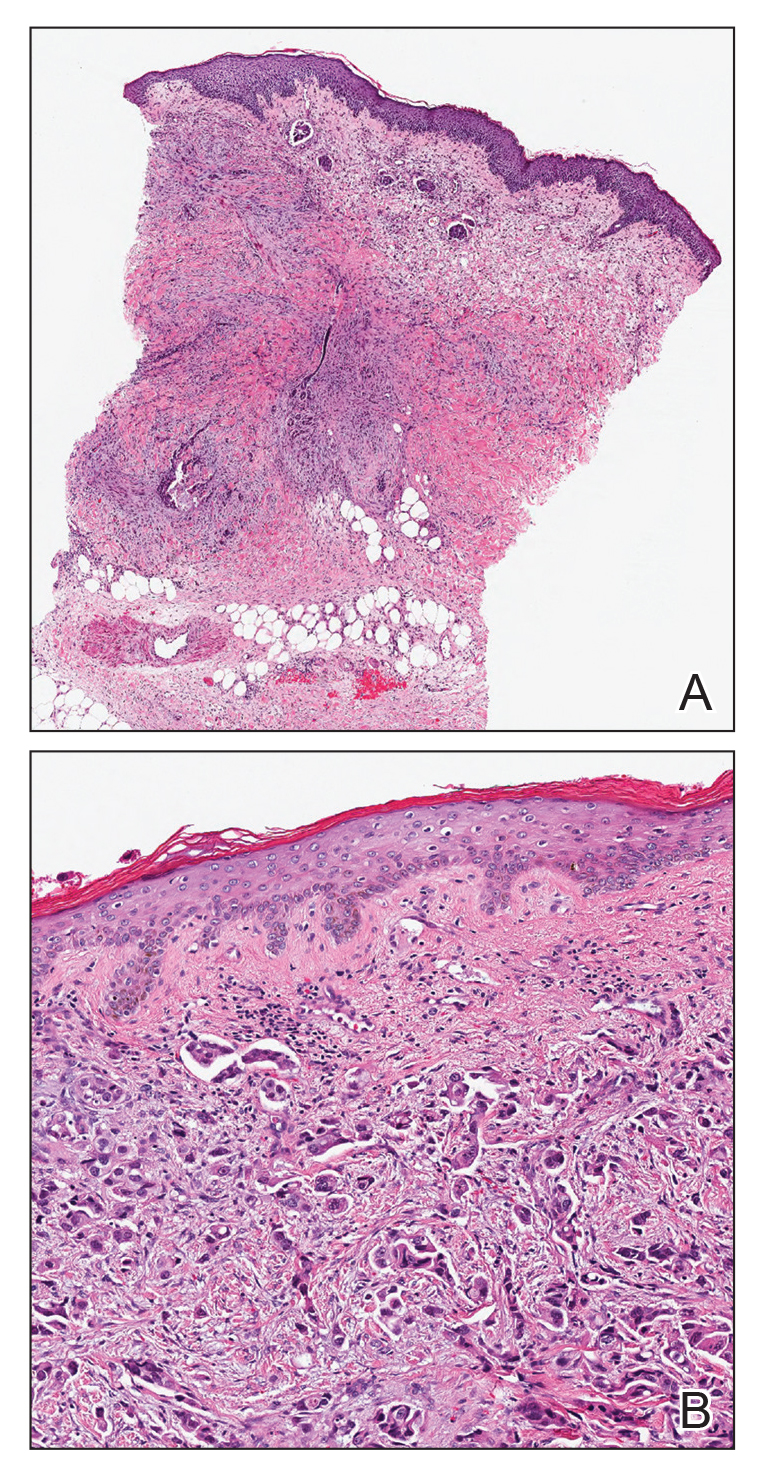

Histopathologic examination showed multiple small, keratin-filled cystic spaces in the superficial dermis lined by stratified squamous epithelium that keratinized with a granular layer with surrounding solar elastosis (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with an actinic comedonal plaque (ACP), a rare variant of Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS). Due to other cases of invasive squamous cell carcinomas developing within these lesions1 and the patient's history of basal cell carcinoma in the area, it was important to rule out malignancy and further confirm the diagnosis. Thus, an additional biopsy was obtained, which revealed no sign of cellular atypia. The patient was bothered by the appearance and texture of the lesion, so he elected to pursue treatment. Because of the lesion's moderate size and location, surgical excision was not recommended. He was treated with cryosurgery followed by tretinoin gel 0.025% for 3 months (Figure 2). At 1-year follow-up, there was no recurrence and an acceptable cosmetic outcome.

Actinic comedonal plaques are characterized by cysts, comedones, and papules that form well-defined yellow plaques on the skin after chronic sun exposure.2 First described in 1980 by Eastern and Martin,3 these lesions are most often found on the neck, thorax, nasal dorsum, helix, and forearms; they often are mistaken for basal cell carcinomas, chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, and amyloidosis.2,4

Similar to the cases described by Eastern and Martin,3 our patient presented with a solitary 2.8×1.6-cm yellowish and bumpy plaque that was growing on chronically sun-exposed skin of the medial right cheek. The patient's history of smoking and basal cell carcinoma removal led to the following differential diagnoses: recurrent malignancy, tumors of dermal appendages, and xanthelasmalike deposition within a scar, among others.

Histologic examination demonstrated keratin-filled cystic spaces in the superficial dermis, along with hyperkeratosis and solar elastosis. These findings were consistent with the original histologic descriptions of ACP that were cited as a rare ectopic form of FRS.5 Leeuwis-Fedorovich et al1 described multifocal squamous cell carcinomas arising in a FRS lesion in 2 cases. Additional biopsy was performed in our patient to rule out this possibility.

Aside from its role in dermatologic malignancy, exposure to UV light can lead to dilation of the sebaceous gland infundibulum and formation of comedones in various locations.2 Histologically, lesions of ACP feature dilated, keratin-filled follicles within a matrix of amorphous damaged collagen in the middle and lower dermis, along with elastosis and basophilic degeneration with fragmentation of collagen bundles in the upper dermis coated with flattened epidermis.2,3

Several clinical diagnoses were considered in the differential for our patient. In contrast to our patient's solitary lesion, classic FRS--nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones--is characterized by a diffuse yellowish hue of large open black comedones that are symmetrically distributed on the temporal and periorbital areas.6

Xanthoma has several clinical presentations. Plane xanthomas typically develop in skin folds, especially in palmar creases, while xanthelasma typically consists of yellow soft plaques on the eyelids and periorbital skin. Histologically, xanthomas contain lipid-laden macrophages, which were absent in our patient.7

Cutaneous amyloidosis can be characterized as macular, papular, and nodular. Nodular, the rarest subtype, commonly manifests on the face.8 However, its characteristic histologic features include atrophic epidermal changes with an amorphous, eosinophilic-appearing dermis due to amyloid deposition. These findings were absent in our case.

Recurrent neoplasm would be in the differential diagnosis of any solitary nodule arising within a previously treated site of malignancy, which was excluded by histologic examination of our patient.7

Topical tretinoin has been demonstrated as effective treatment of both FRS and ACP.2,9 Other effective treatment modalities include cryotherapy and photoprotection.9 For our patient, a combination of cryosurgery and topical tretinoin resulted in depression of the plaque and a good cosmetic outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this article. We also are indebted to Morgan L. Wilson, MD (Springfield, Illinois), for his expert dermatopathologic evaluation in this case. He has received no compensation for his contribution.

- Leeuwis-Fedorovich NE, Starink M, van der Wal AC. Multifocal squamous cell carcinoma arising in a Favre-Racouchot lesion—report of two cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:103-106.

- Cardoso F, Nakandakari S, Zattar GA, et al. Actinic comedonal plaquevariant of Favre-Racouchot syndrome: report of two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(suppl 1):185-187.

- Eastern JS, Martin S. Actinic comedonal plaque. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:633-636.

- Hauptman G, Kopf A, Rabinovitz HS, et al. The actinic comedonal plaque. Cutis. 1997;60:145-146.

- John SM, Hamm H. Actinic comedonal plaque—a rare ectopic form of the Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:256-258.

- Sonthalia S, Arora R, Chhabra N, et al. Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 2):S128-S129.

- Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Murphy GF, et al. Benign pigmented lesions and malignant melanoma. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:699-790.

- Lee DY, Kim YJ, Lee JY, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis following local trauma. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:515-518.

- Patterson WM, Fox MD, Schwartz RA. Favre-Racouchot disease. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:167-169.

The Diagnosis: Actinic Comedonal Plaque

Histopathologic examination showed multiple small, keratin-filled cystic spaces in the superficial dermis lined by stratified squamous epithelium that keratinized with a granular layer with surrounding solar elastosis (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with an actinic comedonal plaque (ACP), a rare variant of Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS). Due to other cases of invasive squamous cell carcinomas developing within these lesions1 and the patient's history of basal cell carcinoma in the area, it was important to rule out malignancy and further confirm the diagnosis. Thus, an additional biopsy was obtained, which revealed no sign of cellular atypia. The patient was bothered by the appearance and texture of the lesion, so he elected to pursue treatment. Because of the lesion's moderate size and location, surgical excision was not recommended. He was treated with cryosurgery followed by tretinoin gel 0.025% for 3 months (Figure 2). At 1-year follow-up, there was no recurrence and an acceptable cosmetic outcome.

Actinic comedonal plaques are characterized by cysts, comedones, and papules that form well-defined yellow plaques on the skin after chronic sun exposure.2 First described in 1980 by Eastern and Martin,3 these lesions are most often found on the neck, thorax, nasal dorsum, helix, and forearms; they often are mistaken for basal cell carcinomas, chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, and amyloidosis.2,4

Similar to the cases described by Eastern and Martin,3 our patient presented with a solitary 2.8×1.6-cm yellowish and bumpy plaque that was growing on chronically sun-exposed skin of the medial right cheek. The patient's history of smoking and basal cell carcinoma removal led to the following differential diagnoses: recurrent malignancy, tumors of dermal appendages, and xanthelasmalike deposition within a scar, among others.

Histologic examination demonstrated keratin-filled cystic spaces in the superficial dermis, along with hyperkeratosis and solar elastosis. These findings were consistent with the original histologic descriptions of ACP that were cited as a rare ectopic form of FRS.5 Leeuwis-Fedorovich et al1 described multifocal squamous cell carcinomas arising in a FRS lesion in 2 cases. Additional biopsy was performed in our patient to rule out this possibility.

Aside from its role in dermatologic malignancy, exposure to UV light can lead to dilation of the sebaceous gland infundibulum and formation of comedones in various locations.2 Histologically, lesions of ACP feature dilated, keratin-filled follicles within a matrix of amorphous damaged collagen in the middle and lower dermis, along with elastosis and basophilic degeneration with fragmentation of collagen bundles in the upper dermis coated with flattened epidermis.2,3

Several clinical diagnoses were considered in the differential for our patient. In contrast to our patient's solitary lesion, classic FRS--nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones--is characterized by a diffuse yellowish hue of large open black comedones that are symmetrically distributed on the temporal and periorbital areas.6

Xanthoma has several clinical presentations. Plane xanthomas typically develop in skin folds, especially in palmar creases, while xanthelasma typically consists of yellow soft plaques on the eyelids and periorbital skin. Histologically, xanthomas contain lipid-laden macrophages, which were absent in our patient.7

Cutaneous amyloidosis can be characterized as macular, papular, and nodular. Nodular, the rarest subtype, commonly manifests on the face.8 However, its characteristic histologic features include atrophic epidermal changes with an amorphous, eosinophilic-appearing dermis due to amyloid deposition. These findings were absent in our case.

Recurrent neoplasm would be in the differential diagnosis of any solitary nodule arising within a previously treated site of malignancy, which was excluded by histologic examination of our patient.7

Topical tretinoin has been demonstrated as effective treatment of both FRS and ACP.2,9 Other effective treatment modalities include cryotherapy and photoprotection.9 For our patient, a combination of cryosurgery and topical tretinoin resulted in depression of the plaque and a good cosmetic outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this article. We also are indebted to Morgan L. Wilson, MD (Springfield, Illinois), for his expert dermatopathologic evaluation in this case. He has received no compensation for his contribution.

The Diagnosis: Actinic Comedonal Plaque

Histopathologic examination showed multiple small, keratin-filled cystic spaces in the superficial dermis lined by stratified squamous epithelium that keratinized with a granular layer with surrounding solar elastosis (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with an actinic comedonal plaque (ACP), a rare variant of Favre-Racouchot syndrome (FRS). Due to other cases of invasive squamous cell carcinomas developing within these lesions1 and the patient's history of basal cell carcinoma in the area, it was important to rule out malignancy and further confirm the diagnosis. Thus, an additional biopsy was obtained, which revealed no sign of cellular atypia. The patient was bothered by the appearance and texture of the lesion, so he elected to pursue treatment. Because of the lesion's moderate size and location, surgical excision was not recommended. He was treated with cryosurgery followed by tretinoin gel 0.025% for 3 months (Figure 2). At 1-year follow-up, there was no recurrence and an acceptable cosmetic outcome.

Actinic comedonal plaques are characterized by cysts, comedones, and papules that form well-defined yellow plaques on the skin after chronic sun exposure.2 First described in 1980 by Eastern and Martin,3 these lesions are most often found on the neck, thorax, nasal dorsum, helix, and forearms; they often are mistaken for basal cell carcinomas, chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica helicis, and amyloidosis.2,4

Similar to the cases described by Eastern and Martin,3 our patient presented with a solitary 2.8×1.6-cm yellowish and bumpy plaque that was growing on chronically sun-exposed skin of the medial right cheek. The patient's history of smoking and basal cell carcinoma removal led to the following differential diagnoses: recurrent malignancy, tumors of dermal appendages, and xanthelasmalike deposition within a scar, among others.

Histologic examination demonstrated keratin-filled cystic spaces in the superficial dermis, along with hyperkeratosis and solar elastosis. These findings were consistent with the original histologic descriptions of ACP that were cited as a rare ectopic form of FRS.5 Leeuwis-Fedorovich et al1 described multifocal squamous cell carcinomas arising in a FRS lesion in 2 cases. Additional biopsy was performed in our patient to rule out this possibility.

Aside from its role in dermatologic malignancy, exposure to UV light can lead to dilation of the sebaceous gland infundibulum and formation of comedones in various locations.2 Histologically, lesions of ACP feature dilated, keratin-filled follicles within a matrix of amorphous damaged collagen in the middle and lower dermis, along with elastosis and basophilic degeneration with fragmentation of collagen bundles in the upper dermis coated with flattened epidermis.2,3

Several clinical diagnoses were considered in the differential for our patient. In contrast to our patient's solitary lesion, classic FRS--nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones--is characterized by a diffuse yellowish hue of large open black comedones that are symmetrically distributed on the temporal and periorbital areas.6

Xanthoma has several clinical presentations. Plane xanthomas typically develop in skin folds, especially in palmar creases, while xanthelasma typically consists of yellow soft plaques on the eyelids and periorbital skin. Histologically, xanthomas contain lipid-laden macrophages, which were absent in our patient.7

Cutaneous amyloidosis can be characterized as macular, papular, and nodular. Nodular, the rarest subtype, commonly manifests on the face.8 However, its characteristic histologic features include atrophic epidermal changes with an amorphous, eosinophilic-appearing dermis due to amyloid deposition. These findings were absent in our case.

Recurrent neoplasm would be in the differential diagnosis of any solitary nodule arising within a previously treated site of malignancy, which was excluded by histologic examination of our patient.7

Topical tretinoin has been demonstrated as effective treatment of both FRS and ACP.2,9 Other effective treatment modalities include cryotherapy and photoprotection.9 For our patient, a combination of cryosurgery and topical tretinoin resulted in depression of the plaque and a good cosmetic outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this article. We also are indebted to Morgan L. Wilson, MD (Springfield, Illinois), for his expert dermatopathologic evaluation in this case. He has received no compensation for his contribution.

- Leeuwis-Fedorovich NE, Starink M, van der Wal AC. Multifocal squamous cell carcinoma arising in a Favre-Racouchot lesion—report of two cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:103-106.

- Cardoso F, Nakandakari S, Zattar GA, et al. Actinic comedonal plaquevariant of Favre-Racouchot syndrome: report of two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(suppl 1):185-187.

- Eastern JS, Martin S. Actinic comedonal plaque. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:633-636.

- Hauptman G, Kopf A, Rabinovitz HS, et al. The actinic comedonal plaque. Cutis. 1997;60:145-146.

- John SM, Hamm H. Actinic comedonal plaque—a rare ectopic form of the Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:256-258.

- Sonthalia S, Arora R, Chhabra N, et al. Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 2):S128-S129.

- Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Murphy GF, et al. Benign pigmented lesions and malignant melanoma. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:699-790.

- Lee DY, Kim YJ, Lee JY, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis following local trauma. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:515-518.

- Patterson WM, Fox MD, Schwartz RA. Favre-Racouchot disease. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:167-169.

- Leeuwis-Fedorovich NE, Starink M, van der Wal AC. Multifocal squamous cell carcinoma arising in a Favre-Racouchot lesion—report of two cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:103-106.

- Cardoso F, Nakandakari S, Zattar GA, et al. Actinic comedonal plaquevariant of Favre-Racouchot syndrome: report of two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(suppl 1):185-187.

- Eastern JS, Martin S. Actinic comedonal plaque. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:633-636.

- Hauptman G, Kopf A, Rabinovitz HS, et al. The actinic comedonal plaque. Cutis. 1997;60:145-146.

- John SM, Hamm H. Actinic comedonal plaque—a rare ectopic form of the Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:256-258.

- Sonthalia S, Arora R, Chhabra N, et al. Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 2):S128-S129.

- Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Murphy GF, et al. Benign pigmented lesions and malignant melanoma. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:699-790.

- Lee DY, Kim YJ, Lee JY, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis following local trauma. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:515-518.

- Patterson WM, Fox MD, Schwartz RA. Favre-Racouchot disease. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:167-169.

A 79-year-old man presented to dermatology with an enlarging bump on the right cheek. He reported a history of basal cell carcinoma on the medial right cheek that was removed 15 years prior with a resultant scar. Over the last 6 months, the area became more red and bumpy, and the lesion increased in size but was otherwise asymptomatic. The patient reported no history of other dermatologic conditions or skin cancer aside from the prior basal cell carcinoma. His medical history was notable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. He had a history of smoking for many years (only recently quit) with extensive sun exposure in his lifetime as an outdoor worker. Physical examination revealed a 2.8.2 ×1.6-cm, pink, telangiectatic, and slightly depressed plaque, with the surface consisting of multiple white to yellowish coalescing papules. As part of the dermatologic workup, 4-mm punch and shave biopsies were obtained.

Unilateral Papules on the Face

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

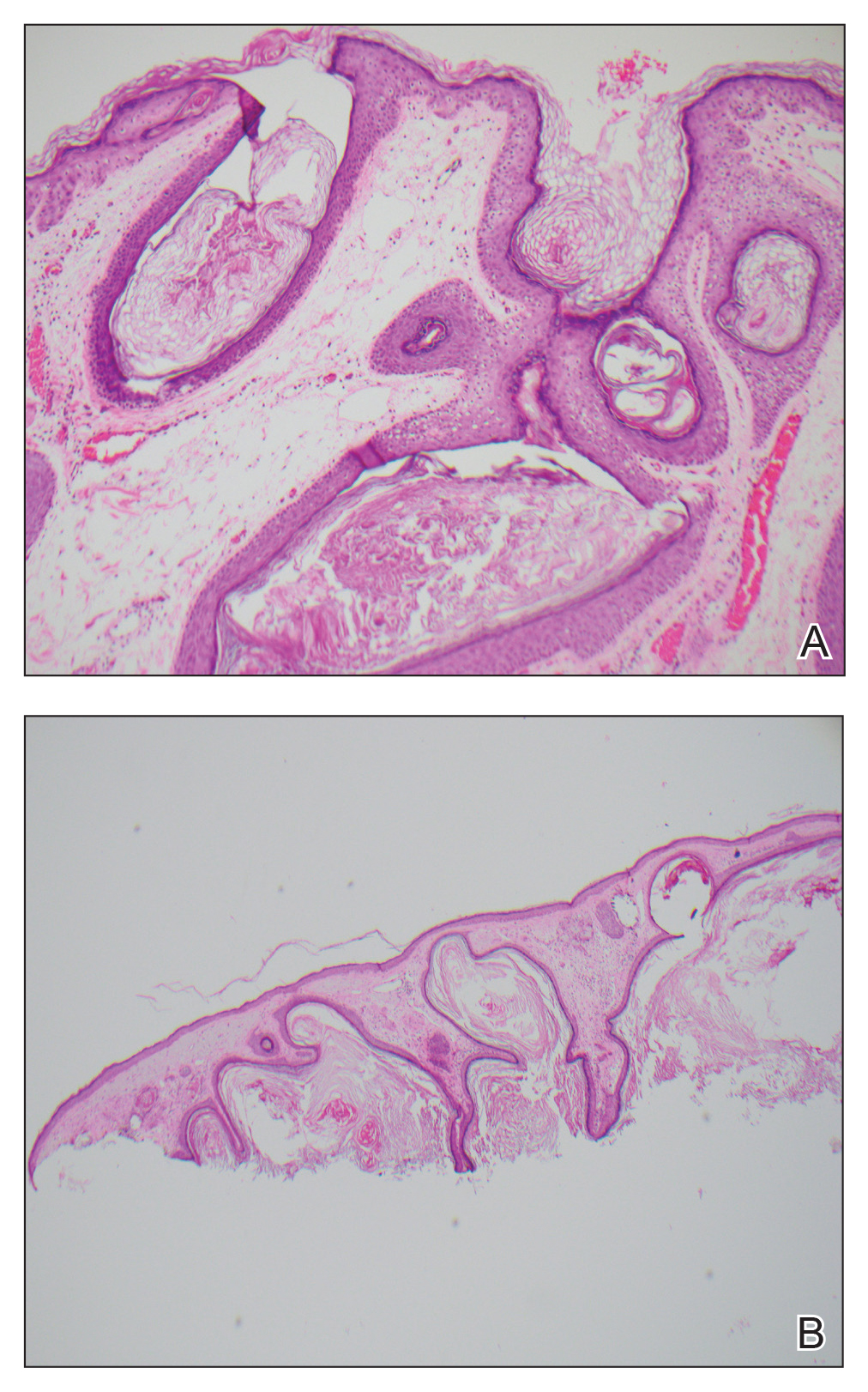

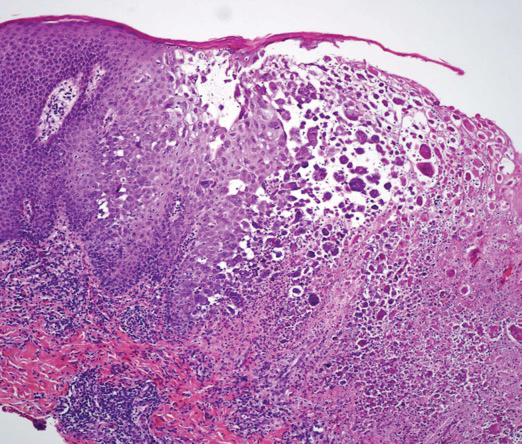

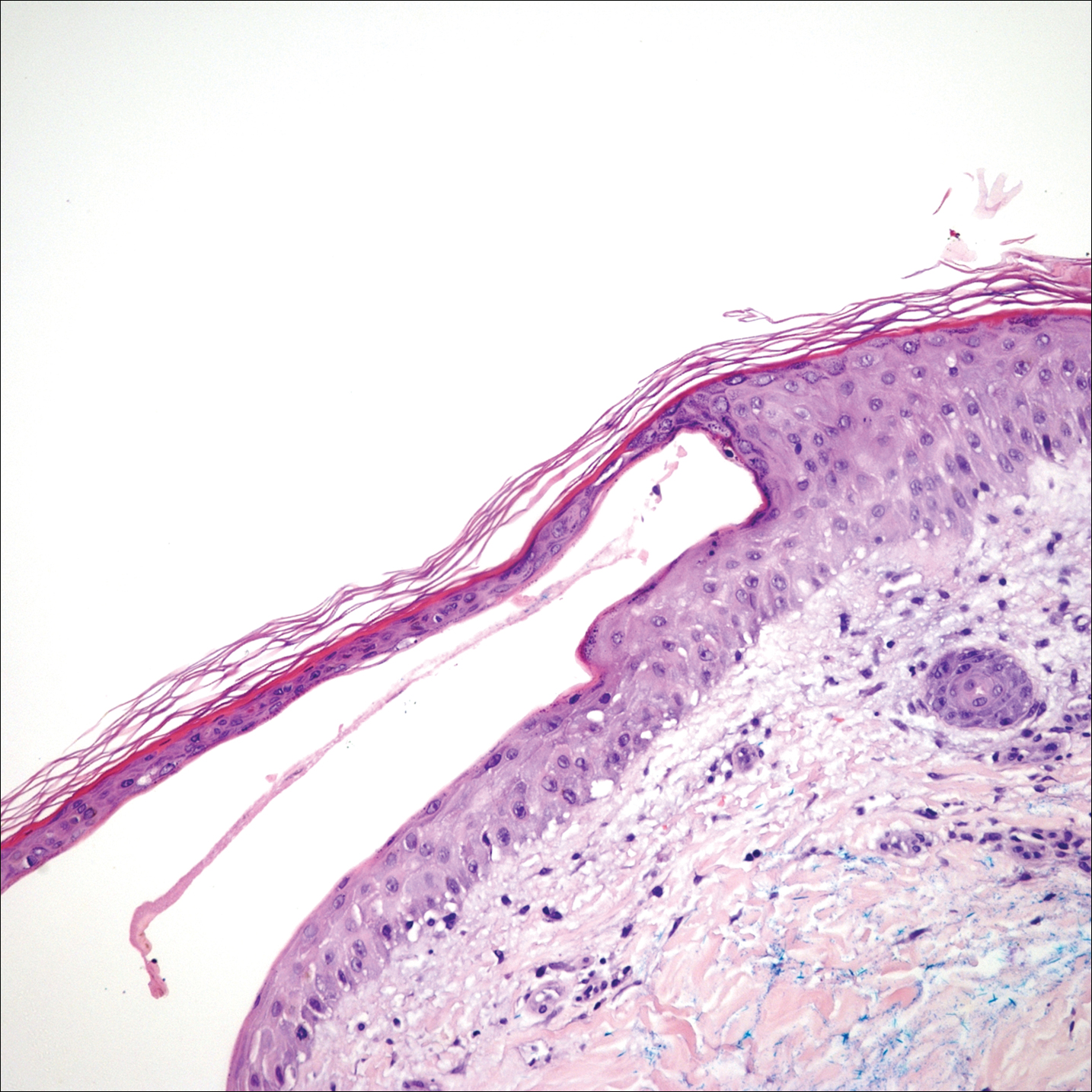

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

An 18-year-old woman presented with a progressive appearance of firm, red-brown, asymptomatic, 1- to 3-mm, dome-shaped papules on the right cheek that developed over the course of 2 years. She had 10 lesions that covered a 2.2 ×4-cm area on the right medial cheek. No similar-appearing lesions were detectable on a full-body skin examination, and no periungual tumors, café au lait macules, or shagreen patches were noted. A full-body skin examination using a Wood lamp revealed 1 small hypopigmented macule on the right second finger. The patient had a history of treatment-refractory migraines; magnetic resonance imaging 5 years prior to the current presentation revealed a nonspecific lesion in the left parietal gyrus. There was no personal or family history of seizures, cognitive delay, kidney disease, or ocular disease. Punch biopsy of a facial lesion was performed for histopathologic correlation.

Yellow-Brown Ulcerated Papule in a Newborn

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

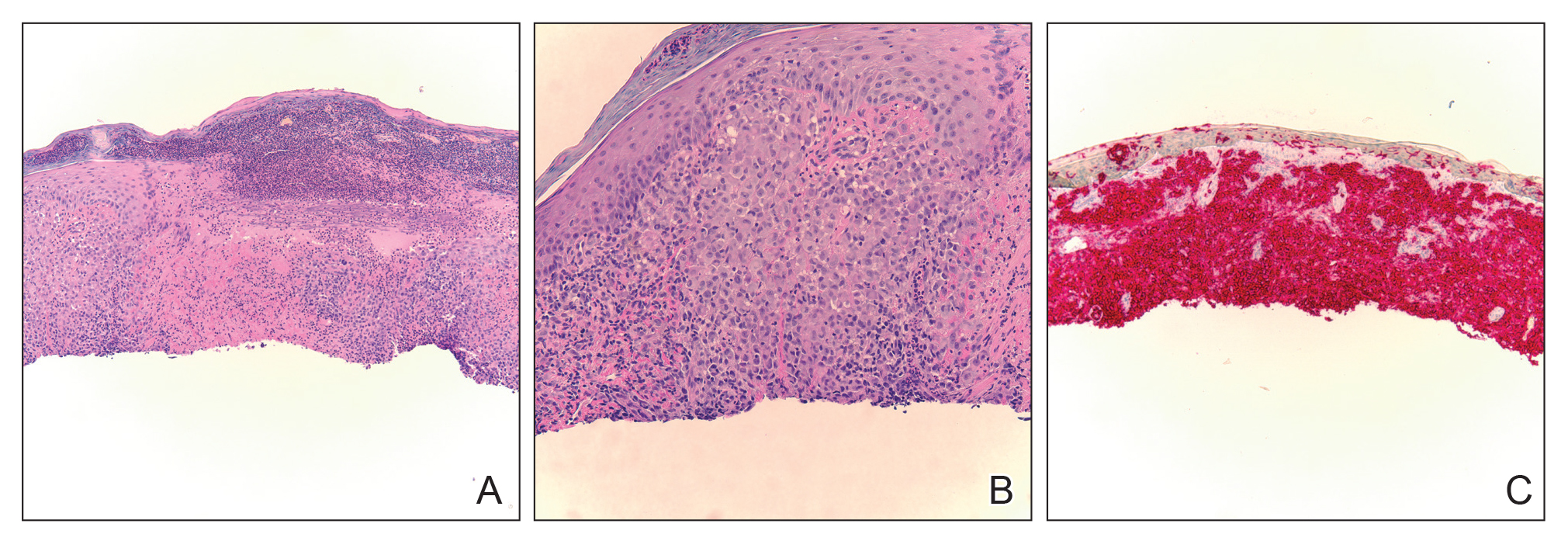

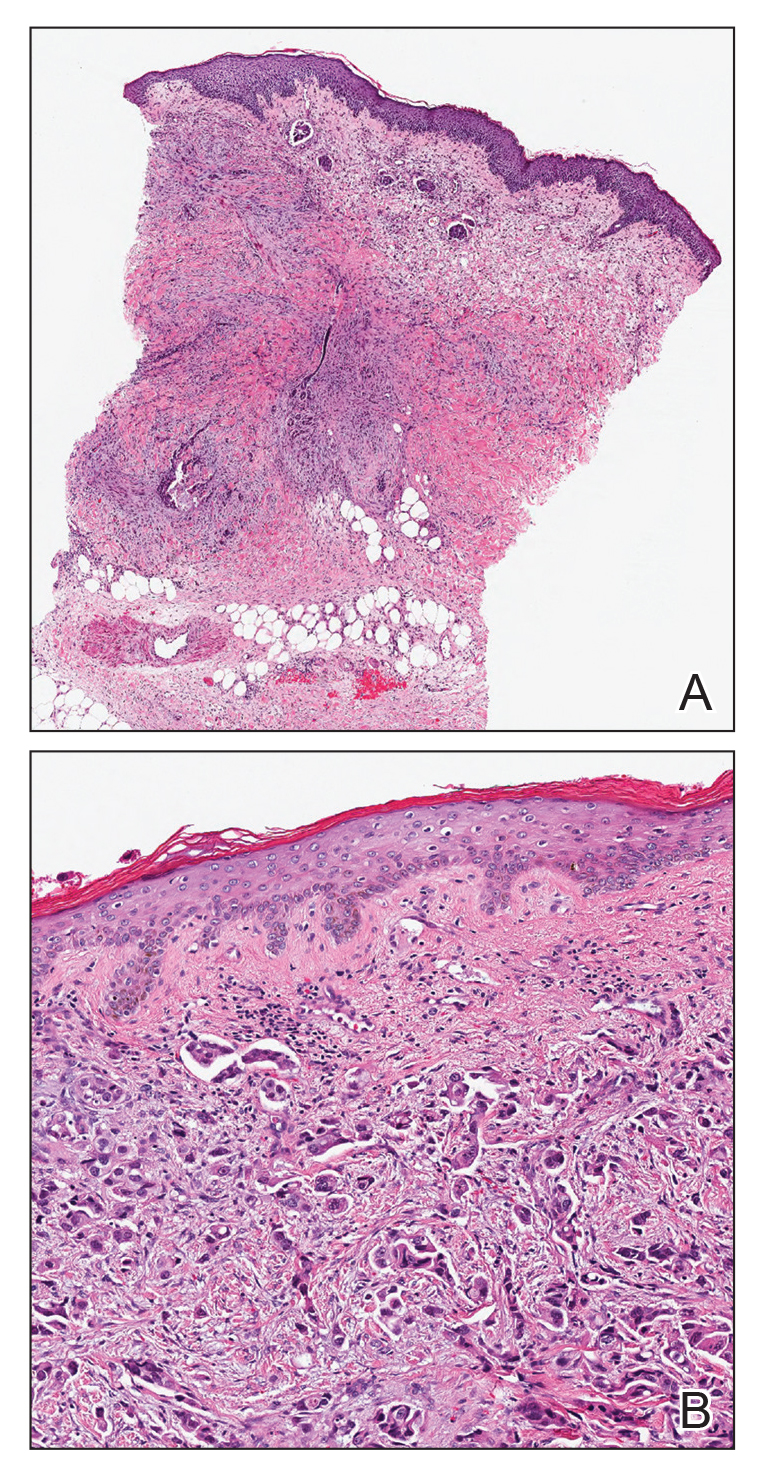

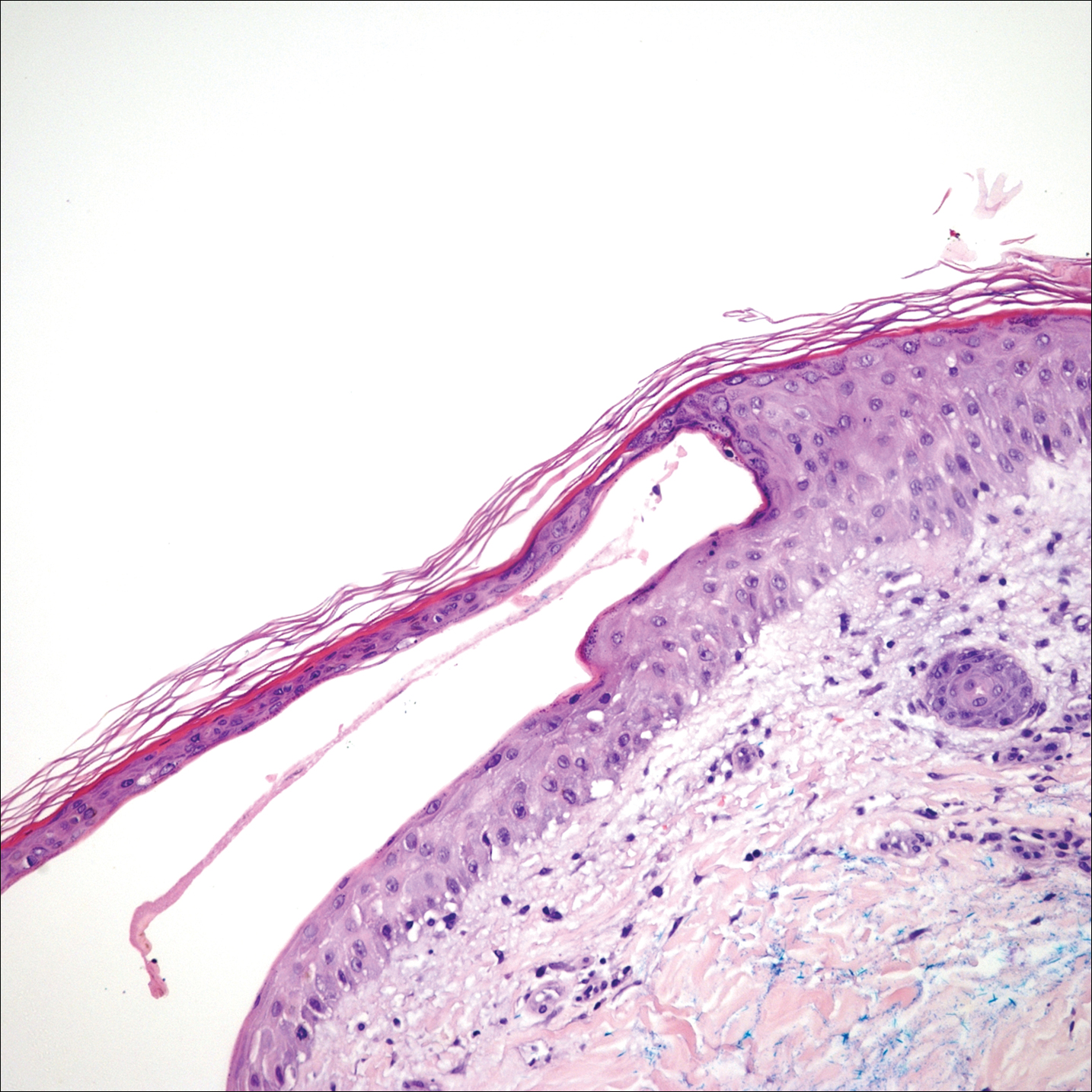

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

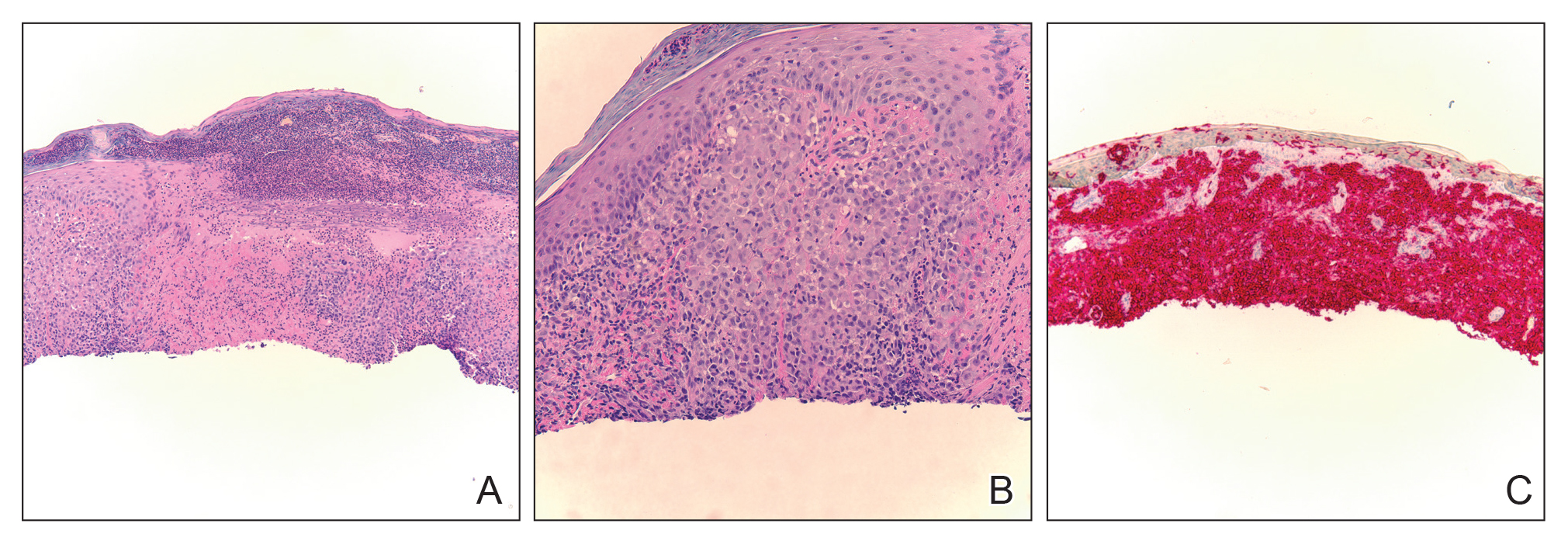

An 18-day-old infant boy presented with yellow-brown ulcerated papules on the left posterior leg (top) and left posterior shoulder (bottom). He was born via spontaneous vaginal delivery at 33 1/7 weeks' gestation complicated by preeclampsia. The lesions were unchanged during the infant's stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. However, his mother noted that one lesion crusted once home without an increase in size. His fraternal twin sister did not have any similar lesions. Jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly were absent. He was referred to hematology/oncology. A complete blood cell count revealed nonconcerning slight anemia. Liver function tests, coagulation studies, a chest radiograph, and a skeletal survey were ordered.

Pink Polycyclic Ulcerations on the Lower Back and Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

A 32-year-old woman with stage IV cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was admitted with pancytopenia and septic shock secondary to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Dermatology was consulted regarding sacral ulcerations. The lesions were asymptomatic and had been slowly enlarging over the course of 1 month. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, pink, polycyclic ulcerations on the lower back and buttocks extending onto the perineum. There was no pain or tingling associated with the ulcerations. She denied a history of cold sore lesions on the lips or genitals. A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and histopathologic examination.

Erythematous Plaques and Nodules on the Abdomen and Groin

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

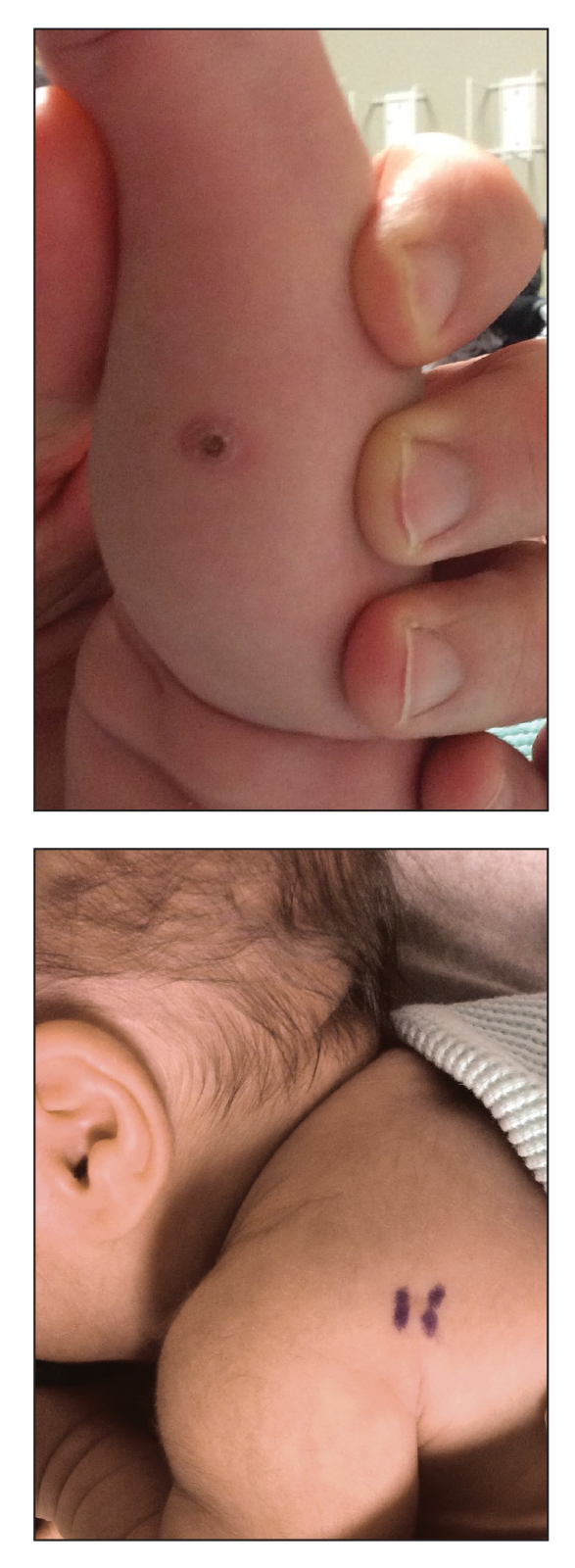

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.