User login

Football for the young

A few weeks ago I was at a Friday-night football game, but not to watch the game. I’ve been there and done that too many times when I used to be the team physician. I was there to listen to my granddaughter drumming in the pep band. And there was a lot of drumming because her high school’s team is having a hot year and outscoring opponents by three and four touchdowns every week.

At half time, the field was swarmed by 45-50 early grade schoolers looking like bobblehead dolls in their oversize helmets and surprisingly professional-appearing miniature football outfits. Under the lights, on the local college’s turf field, they were in football heaven. The pep band got into it and there was more drumming as the few kids who had a clue what football was about were scampering over and around their teammates and opponents who were roughhousing with each other, rolling around on the turf having a grand time, blissfully unimpressed by such trivial concepts as the line of scrimmage or the difference between blocking and tackling or even offense and defense.

Despite all the alarming articles both lay and professional that you and I see, this was an evening on which no one seemed particularly concerned about sports-related concussions. This is class B football in Maine, not a state well known as an incubator of Division I college football players. While there were a few scrawny kids with some speed,

Watching 4- and 5-year-olds in their football uniforms seemed to me to be a rather harmless exercise and certainly a more positive investment in their time on a Friday night than sitting on the couch with an electronic device clutched in their little hands. A recent report in JAMA Pediatrics suggests that my lack of concern has some validity (“Consensus statement on sports-related concussions in youth sports using a modified delphi approach.” JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4006). Eleven experts in sports-related injuries were surveyed with multiple rounds of questionnaires. Their anonymous responses were aggregated and shared with the group after each round until a consensus could be arrived on for each of seven broad questions about sports-related concussions. It is a paper worth reading and like most good literature surveys determined that in many situations more study needs to be done.

Among the many findings that impressed me was the group’s failure to find an “association between repetitive head impact exposure in youth and long-term neurocognitive outcomes.” In addition, “there is little evidence that age at first exposure repetitive head impacts in sports is independently associated with neurodegenerative changes.” The experts also could find “no evidence that growth or development affect the risk of sports-related concussions.”

The problem with youth football is that it is the portal that can lead to college and professional football, in which large bodies are allowed to collide after accelerating at speeds we mortals only can achieve behind the wheel of our motor vehicles. Rules to minimize those collisions do exist, but lax enforcement has failed to prevent their cumulative damage.

Whether the culture of big-time football is going to change to a point at which a conscientious parent could encourage his or her child to play after adolescence remains to be seen. However, the evidence seems to suggest that allowing young children to bang themselves around imitating the big guys seems to be reasonably safe. At least as safe as what kids used to do to each other before we adults invented television and video games.

When my son was 3 or 4 years old, he played on a hockey team he thought was called the Toronto Make-Believes (Maple Leafs). Maybe we should be telling parents it’s safe for their children to play make-believe contact sports. The challenge comes after those kids reach puberty and want to start playing the real thing.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

A few weeks ago I was at a Friday-night football game, but not to watch the game. I’ve been there and done that too many times when I used to be the team physician. I was there to listen to my granddaughter drumming in the pep band. And there was a lot of drumming because her high school’s team is having a hot year and outscoring opponents by three and four touchdowns every week.

At half time, the field was swarmed by 45-50 early grade schoolers looking like bobblehead dolls in their oversize helmets and surprisingly professional-appearing miniature football outfits. Under the lights, on the local college’s turf field, they were in football heaven. The pep band got into it and there was more drumming as the few kids who had a clue what football was about were scampering over and around their teammates and opponents who were roughhousing with each other, rolling around on the turf having a grand time, blissfully unimpressed by such trivial concepts as the line of scrimmage or the difference between blocking and tackling or even offense and defense.

Despite all the alarming articles both lay and professional that you and I see, this was an evening on which no one seemed particularly concerned about sports-related concussions. This is class B football in Maine, not a state well known as an incubator of Division I college football players. While there were a few scrawny kids with some speed,

Watching 4- and 5-year-olds in their football uniforms seemed to me to be a rather harmless exercise and certainly a more positive investment in their time on a Friday night than sitting on the couch with an electronic device clutched in their little hands. A recent report in JAMA Pediatrics suggests that my lack of concern has some validity (“Consensus statement on sports-related concussions in youth sports using a modified delphi approach.” JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4006). Eleven experts in sports-related injuries were surveyed with multiple rounds of questionnaires. Their anonymous responses were aggregated and shared with the group after each round until a consensus could be arrived on for each of seven broad questions about sports-related concussions. It is a paper worth reading and like most good literature surveys determined that in many situations more study needs to be done.

Among the many findings that impressed me was the group’s failure to find an “association between repetitive head impact exposure in youth and long-term neurocognitive outcomes.” In addition, “there is little evidence that age at first exposure repetitive head impacts in sports is independently associated with neurodegenerative changes.” The experts also could find “no evidence that growth or development affect the risk of sports-related concussions.”

The problem with youth football is that it is the portal that can lead to college and professional football, in which large bodies are allowed to collide after accelerating at speeds we mortals only can achieve behind the wheel of our motor vehicles. Rules to minimize those collisions do exist, but lax enforcement has failed to prevent their cumulative damage.

Whether the culture of big-time football is going to change to a point at which a conscientious parent could encourage his or her child to play after adolescence remains to be seen. However, the evidence seems to suggest that allowing young children to bang themselves around imitating the big guys seems to be reasonably safe. At least as safe as what kids used to do to each other before we adults invented television and video games.

When my son was 3 or 4 years old, he played on a hockey team he thought was called the Toronto Make-Believes (Maple Leafs). Maybe we should be telling parents it’s safe for their children to play make-believe contact sports. The challenge comes after those kids reach puberty and want to start playing the real thing.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

A few weeks ago I was at a Friday-night football game, but not to watch the game. I’ve been there and done that too many times when I used to be the team physician. I was there to listen to my granddaughter drumming in the pep band. And there was a lot of drumming because her high school’s team is having a hot year and outscoring opponents by three and four touchdowns every week.

At half time, the field was swarmed by 45-50 early grade schoolers looking like bobblehead dolls in their oversize helmets and surprisingly professional-appearing miniature football outfits. Under the lights, on the local college’s turf field, they were in football heaven. The pep band got into it and there was more drumming as the few kids who had a clue what football was about were scampering over and around their teammates and opponents who were roughhousing with each other, rolling around on the turf having a grand time, blissfully unimpressed by such trivial concepts as the line of scrimmage or the difference between blocking and tackling or even offense and defense.

Despite all the alarming articles both lay and professional that you and I see, this was an evening on which no one seemed particularly concerned about sports-related concussions. This is class B football in Maine, not a state well known as an incubator of Division I college football players. While there were a few scrawny kids with some speed,

Watching 4- and 5-year-olds in their football uniforms seemed to me to be a rather harmless exercise and certainly a more positive investment in their time on a Friday night than sitting on the couch with an electronic device clutched in their little hands. A recent report in JAMA Pediatrics suggests that my lack of concern has some validity (“Consensus statement on sports-related concussions in youth sports using a modified delphi approach.” JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Nov 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4006). Eleven experts in sports-related injuries were surveyed with multiple rounds of questionnaires. Their anonymous responses were aggregated and shared with the group after each round until a consensus could be arrived on for each of seven broad questions about sports-related concussions. It is a paper worth reading and like most good literature surveys determined that in many situations more study needs to be done.

Among the many findings that impressed me was the group’s failure to find an “association between repetitive head impact exposure in youth and long-term neurocognitive outcomes.” In addition, “there is little evidence that age at first exposure repetitive head impacts in sports is independently associated with neurodegenerative changes.” The experts also could find “no evidence that growth or development affect the risk of sports-related concussions.”

The problem with youth football is that it is the portal that can lead to college and professional football, in which large bodies are allowed to collide after accelerating at speeds we mortals only can achieve behind the wheel of our motor vehicles. Rules to minimize those collisions do exist, but lax enforcement has failed to prevent their cumulative damage.

Whether the culture of big-time football is going to change to a point at which a conscientious parent could encourage his or her child to play after adolescence remains to be seen. However, the evidence seems to suggest that allowing young children to bang themselves around imitating the big guys seems to be reasonably safe. At least as safe as what kids used to do to each other before we adults invented television and video games.

When my son was 3 or 4 years old, he played on a hockey team he thought was called the Toronto Make-Believes (Maple Leafs). Maybe we should be telling parents it’s safe for their children to play make-believe contact sports. The challenge comes after those kids reach puberty and want to start playing the real thing.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Lay press stories about research: Putting them into perspective for patients

I recently had an unusual patient call. A woman I’ve seen for many years for migraines called to tell me her son was being hospitalized for appendicitis. He was scheduled for surgery in the morning.

She called because she’d recently seen a news report about how people without an appendix may have a higher rate of Parkinson’s disease as they age. She was, understandably, concerned about the long-term risks the procedure could pose.

On the surface, as a medical professional, the call sounds frivolous and silly. The risks of untreated acute appendicitis, such as peritonitis and death, are pretty well documented. Surgery offers the best possibility for a cure without recurrence. Compared with the long-term, uncertain, risk of Parkinson’s disease, the benefit-to-risk ratio and options are pretty obvious.

The question of the GI tract’s involvement in neurologic diseases is a legitimate one that needs to be answered. It may provide new insight into their causes and potential treatments. The research she brought up raises some interesting points.

But that doesn’t mean there should be any delay in treating something as easily cured – and potentially serious – as acute appendicitis.

My patient called to ask questions, and I have no issue with that. To someone with no medical training, it’s a legitimate concern. But not everyone will call to ask.

This is a hazard of early stages of medical research making it into the lay press. It may be right, it may be wrong, but it’s too early to tell either way. We have years of training to help us recognize the uncertainties of preliminary data, but the general public doesn’t. Stories like this create interest and raise questions in the medical literature and fear and anxiety in the lay press.

I’m a strong supporter of freedom of the press, and certainly they have every right to air or publish such stories. But they should also be put in perspective at the beginning, not the bottom, and make it clear the findings are far from proven.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I recently had an unusual patient call. A woman I’ve seen for many years for migraines called to tell me her son was being hospitalized for appendicitis. He was scheduled for surgery in the morning.

She called because she’d recently seen a news report about how people without an appendix may have a higher rate of Parkinson’s disease as they age. She was, understandably, concerned about the long-term risks the procedure could pose.

On the surface, as a medical professional, the call sounds frivolous and silly. The risks of untreated acute appendicitis, such as peritonitis and death, are pretty well documented. Surgery offers the best possibility for a cure without recurrence. Compared with the long-term, uncertain, risk of Parkinson’s disease, the benefit-to-risk ratio and options are pretty obvious.

The question of the GI tract’s involvement in neurologic diseases is a legitimate one that needs to be answered. It may provide new insight into their causes and potential treatments. The research she brought up raises some interesting points.

But that doesn’t mean there should be any delay in treating something as easily cured – and potentially serious – as acute appendicitis.

My patient called to ask questions, and I have no issue with that. To someone with no medical training, it’s a legitimate concern. But not everyone will call to ask.

This is a hazard of early stages of medical research making it into the lay press. It may be right, it may be wrong, but it’s too early to tell either way. We have years of training to help us recognize the uncertainties of preliminary data, but the general public doesn’t. Stories like this create interest and raise questions in the medical literature and fear and anxiety in the lay press.

I’m a strong supporter of freedom of the press, and certainly they have every right to air or publish such stories. But they should also be put in perspective at the beginning, not the bottom, and make it clear the findings are far from proven.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I recently had an unusual patient call. A woman I’ve seen for many years for migraines called to tell me her son was being hospitalized for appendicitis. He was scheduled for surgery in the morning.

She called because she’d recently seen a news report about how people without an appendix may have a higher rate of Parkinson’s disease as they age. She was, understandably, concerned about the long-term risks the procedure could pose.

On the surface, as a medical professional, the call sounds frivolous and silly. The risks of untreated acute appendicitis, such as peritonitis and death, are pretty well documented. Surgery offers the best possibility for a cure without recurrence. Compared with the long-term, uncertain, risk of Parkinson’s disease, the benefit-to-risk ratio and options are pretty obvious.

The question of the GI tract’s involvement in neurologic diseases is a legitimate one that needs to be answered. It may provide new insight into their causes and potential treatments. The research she brought up raises some interesting points.

But that doesn’t mean there should be any delay in treating something as easily cured – and potentially serious – as acute appendicitis.

My patient called to ask questions, and I have no issue with that. To someone with no medical training, it’s a legitimate concern. But not everyone will call to ask.

This is a hazard of early stages of medical research making it into the lay press. It may be right, it may be wrong, but it’s too early to tell either way. We have years of training to help us recognize the uncertainties of preliminary data, but the general public doesn’t. Stories like this create interest and raise questions in the medical literature and fear and anxiety in the lay press.

I’m a strong supporter of freedom of the press, and certainly they have every right to air or publish such stories. But they should also be put in perspective at the beginning, not the bottom, and make it clear the findings are far from proven.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Office of Inspector General

Question: Which one of the following statements is incorrect?

A. Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a federal agency of Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that investigates statutory violations of health care fraud and abuse.

B. The three main legal minefields for physicians are false claims, kickbacks, and self-referrals.

C. Jail terms are part of the penalties provided by law.

D. OIG is also responsible for excluding violators from participating in Medicare/Medicaid programs, as well as curtailing a physician’s license to practice.

E. A private citizen can file a qui tam lawsuit against an errant practitioner or health care entity for fraud and abuse.

Answer: D. Health care fraud, waste, and abuse consume some 10% of federal health expenditures despite well-established laws that attempt to prevent and reduce such losses. The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General, as well as the Department of Justice and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are charged with enforcing these and other laws like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. Their web pages, referenced throughout this article, contain a wealth of information for the practitioner.

The term “Office of Inspector General” (OIG) refers to the oversight division of a federal or state agency charged with identifying and investigating fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement within that department or agency. There are currently 73 separate federal offices of inspectors general, which employ armed and unarmed criminal investigators, auditors, forensic auditors called “audigators,” and a variety of other specialists. An Act of Congress in 1976 established the first OIG under HHS. Besides being the first, HHS-OIG is also the largest, with a staff of approximately 1,600. A majority of resources goes toward the oversight of Medicare and Medicaid, as well as programs under other HHS institutions such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration.1

HHS-OIG has the authority to seek civil monetary penalties, assessments, and exclusion against an individual or entity based on a wide variety of prohibited conduct affecting federal health care programs. Stiff penalties are regularly assessed against violators, and jail terms are not uncommon; however, it has no direct jurisdictions over physician licensure or nonfederal programs. The government maintains a pictorial list of its most wanted health care fugitives2 and provides an excellent set of Physician Education Training Materials on its website.3

False Claims Act (FCA)

In the health care arena, violation of FCA (31 U.S.C. §§3729-3733) is the foremost infraction. False claims by physicians can include billing for noncovered services such as experimental treatments, double billing, billing the government as the primary payer, or regularly waiving deductibles and copayments, as well as quality of care issues and unnecessary services. Wrongdoing also includes knowingly using another patient’s name for purposes of, say, federal drug coverage, billing for no-shows, and misrepresenting the diagnosis to justify services, as well as other claims. In the modern doctor’s office, the EMR enables easy check-offs on a preprinted form as documentation of actual work done. However, fraud is implicated if the information is deliberately misleading such as for purposes of upcoding. Importantly, physicians are liable for the actions of their office staff, so it is prudent to oversee and supervise all such activities. Naturally, one should document all claims that are sent and know the rules for allowable and excluded services.

FCA is an old law that was first enacted in 1863. It imposes liability for submitting a payment demand to the federal government where there is actual or constructive knowledge that the claim is false. Intent to defraud is not a required element but knowing or showing reckless disregard of the truth is. However, an error that is negligently committed is insufficient to constitute a violation. Penalties include treble damages, costs and attorney fees, and fines of $11,000 per false claim, as well as possible imprisonment and criminal fines. A so-called whistle-blower may file a lawsuit on behalf of the government and is entitled to a percentage of any recoveries. Whistle-blowers may be current or ex-business partners, hospital or office staff, patients, or competitors. The fact that a claim results from a kickback or is made in violation of the Stark law (discussed below) may also render it fraudulent, thus creating additional liability under FCA.

HHS-OIG, as well as the Department of Justice, discloses named cases of statutory violations on their websites. A few random 2019 examples include a New York licensed doctor was convicted of nine counts in connection with Oxycodone and Fentanyl diversion scheme; a Newton, Mass., geriatrician agreed to pay $680,000 to resolve allegations that he violated the False Claims Act by submitting inflated claims to Medicare and the Massachusetts Medicaid program (MassHealth) for care rendered to nursing home patients; and two Clermont, Fla., ophthalmologists agreed to pay a combined total of $157,312.32 to resolve allegations that they violated FCA by knowingly billing the government for mutually exclusive eyelid repair surgeries.

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

AKS (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b[b]) is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by federal health care programs. Remuneration includes anything of value and can take many forms besides cash, such as free rent, lavish travel, and excessive compensation for medical directorships or consultancies. Rewarding a referral source may be acceptable in some industries, but is a crime in federal health care programs.

Moreover, the statute covers both the payers of kickbacks (those who offer or pay remuneration) and the recipients of kickbacks. Each party’s intent is a key element of their liability under AKS. Physicians who pay or accept kickbacks face penalties of up to $50,000 per kickback plus three times the amount of the remuneration and criminal prosecution. As an example, a Tulsa, Okla., doctor earlier this year agreed to pay the government $84,666.42 for allegedly accepting illegal kickback payments from a pharmacy, and in another case, a marketer agreed to pay nearly $340,000 for receiving kickbacks in exchange for prescription referrals.

A physician is an attractive target for kickback schemes. The kickback prohibition applies to all sources, even patients. For example, where the Medicare and Medicaid programs require patients to be responsible for copays for services, the health care provider is generally required to collect that money from the patients. Advertising the forgiveness of copayments or routinely waiving these copays would violate AKS. However, one may waive a copayment when a patient cannot afford to pay one or is uninsured. AKS also imposes civil monetary penalties on physicians who offer remuneration to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to influence them to use their services. Note that the government does not need to prove patient harm or financial loss to show that a violation has occurred, and physicians can be guilty even if they rendered services that are medically necessary.

There are so-called safe harbors that protect certain payment and business practices from running afoul of AKS. The rules and requirements are complex, and require full understanding and strict adherence.4

Physician Self-Referral Law

The Physician Self-Referral Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn), commonly referred to as the Stark law, prohibits physicians from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial relationship, unless an exception applies. Financial relationships include both ownership/investment interests and compensation arrangements. A partial list of “designated health services” includes services related to clinical laboratory, physical therapy, radiology, parenteral and enteral supplies, prosthetic devices and supplies, home health care outpatient prescription drugs, and inpatient and outpatient hospital services. This list is not meant to be an exhaustive one.

Stark is a strict liability statute, which means proof of specific intent to violate the law is not required. The law prohibits the submission, or causing the submission, of claims in violation of the law’s restrictions on referrals. Penalties for physicians who violate the Stark law include fines, as well as exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. Like AKS, Stark law features its own safe harbors.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some materials may have been discussed in earlier columns. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. HHS Office of Inspector General. About OIG. https://oig.hhs.gov/about-oig/about-us/index.asp

2. HHS Office of Inspector General. OIG most wanted fugitives.

3. HHS Office of Inspector General. “Physician education training materials.” A roadmap for new physicians: Avoiding Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse.

4. HHS Office of Inspector General. Safe harbor regulations.

Question: Which one of the following statements is incorrect?

A. Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a federal agency of Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that investigates statutory violations of health care fraud and abuse.

B. The three main legal minefields for physicians are false claims, kickbacks, and self-referrals.

C. Jail terms are part of the penalties provided by law.

D. OIG is also responsible for excluding violators from participating in Medicare/Medicaid programs, as well as curtailing a physician’s license to practice.

E. A private citizen can file a qui tam lawsuit against an errant practitioner or health care entity for fraud and abuse.

Answer: D. Health care fraud, waste, and abuse consume some 10% of federal health expenditures despite well-established laws that attempt to prevent and reduce such losses. The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General, as well as the Department of Justice and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are charged with enforcing these and other laws like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. Their web pages, referenced throughout this article, contain a wealth of information for the practitioner.

The term “Office of Inspector General” (OIG) refers to the oversight division of a federal or state agency charged with identifying and investigating fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement within that department or agency. There are currently 73 separate federal offices of inspectors general, which employ armed and unarmed criminal investigators, auditors, forensic auditors called “audigators,” and a variety of other specialists. An Act of Congress in 1976 established the first OIG under HHS. Besides being the first, HHS-OIG is also the largest, with a staff of approximately 1,600. A majority of resources goes toward the oversight of Medicare and Medicaid, as well as programs under other HHS institutions such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration.1

HHS-OIG has the authority to seek civil monetary penalties, assessments, and exclusion against an individual or entity based on a wide variety of prohibited conduct affecting federal health care programs. Stiff penalties are regularly assessed against violators, and jail terms are not uncommon; however, it has no direct jurisdictions over physician licensure or nonfederal programs. The government maintains a pictorial list of its most wanted health care fugitives2 and provides an excellent set of Physician Education Training Materials on its website.3

False Claims Act (FCA)

In the health care arena, violation of FCA (31 U.S.C. §§3729-3733) is the foremost infraction. False claims by physicians can include billing for noncovered services such as experimental treatments, double billing, billing the government as the primary payer, or regularly waiving deductibles and copayments, as well as quality of care issues and unnecessary services. Wrongdoing also includes knowingly using another patient’s name for purposes of, say, federal drug coverage, billing for no-shows, and misrepresenting the diagnosis to justify services, as well as other claims. In the modern doctor’s office, the EMR enables easy check-offs on a preprinted form as documentation of actual work done. However, fraud is implicated if the information is deliberately misleading such as for purposes of upcoding. Importantly, physicians are liable for the actions of their office staff, so it is prudent to oversee and supervise all such activities. Naturally, one should document all claims that are sent and know the rules for allowable and excluded services.

FCA is an old law that was first enacted in 1863. It imposes liability for submitting a payment demand to the federal government where there is actual or constructive knowledge that the claim is false. Intent to defraud is not a required element but knowing or showing reckless disregard of the truth is. However, an error that is negligently committed is insufficient to constitute a violation. Penalties include treble damages, costs and attorney fees, and fines of $11,000 per false claim, as well as possible imprisonment and criminal fines. A so-called whistle-blower may file a lawsuit on behalf of the government and is entitled to a percentage of any recoveries. Whistle-blowers may be current or ex-business partners, hospital or office staff, patients, or competitors. The fact that a claim results from a kickback or is made in violation of the Stark law (discussed below) may also render it fraudulent, thus creating additional liability under FCA.

HHS-OIG, as well as the Department of Justice, discloses named cases of statutory violations on their websites. A few random 2019 examples include a New York licensed doctor was convicted of nine counts in connection with Oxycodone and Fentanyl diversion scheme; a Newton, Mass., geriatrician agreed to pay $680,000 to resolve allegations that he violated the False Claims Act by submitting inflated claims to Medicare and the Massachusetts Medicaid program (MassHealth) for care rendered to nursing home patients; and two Clermont, Fla., ophthalmologists agreed to pay a combined total of $157,312.32 to resolve allegations that they violated FCA by knowingly billing the government for mutually exclusive eyelid repair surgeries.

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

AKS (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b[b]) is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by federal health care programs. Remuneration includes anything of value and can take many forms besides cash, such as free rent, lavish travel, and excessive compensation for medical directorships or consultancies. Rewarding a referral source may be acceptable in some industries, but is a crime in federal health care programs.

Moreover, the statute covers both the payers of kickbacks (those who offer or pay remuneration) and the recipients of kickbacks. Each party’s intent is a key element of their liability under AKS. Physicians who pay or accept kickbacks face penalties of up to $50,000 per kickback plus three times the amount of the remuneration and criminal prosecution. As an example, a Tulsa, Okla., doctor earlier this year agreed to pay the government $84,666.42 for allegedly accepting illegal kickback payments from a pharmacy, and in another case, a marketer agreed to pay nearly $340,000 for receiving kickbacks in exchange for prescription referrals.

A physician is an attractive target for kickback schemes. The kickback prohibition applies to all sources, even patients. For example, where the Medicare and Medicaid programs require patients to be responsible for copays for services, the health care provider is generally required to collect that money from the patients. Advertising the forgiveness of copayments or routinely waiving these copays would violate AKS. However, one may waive a copayment when a patient cannot afford to pay one or is uninsured. AKS also imposes civil monetary penalties on physicians who offer remuneration to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to influence them to use their services. Note that the government does not need to prove patient harm or financial loss to show that a violation has occurred, and physicians can be guilty even if they rendered services that are medically necessary.

There are so-called safe harbors that protect certain payment and business practices from running afoul of AKS. The rules and requirements are complex, and require full understanding and strict adherence.4

Physician Self-Referral Law

The Physician Self-Referral Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn), commonly referred to as the Stark law, prohibits physicians from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial relationship, unless an exception applies. Financial relationships include both ownership/investment interests and compensation arrangements. A partial list of “designated health services” includes services related to clinical laboratory, physical therapy, radiology, parenteral and enteral supplies, prosthetic devices and supplies, home health care outpatient prescription drugs, and inpatient and outpatient hospital services. This list is not meant to be an exhaustive one.

Stark is a strict liability statute, which means proof of specific intent to violate the law is not required. The law prohibits the submission, or causing the submission, of claims in violation of the law’s restrictions on referrals. Penalties for physicians who violate the Stark law include fines, as well as exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. Like AKS, Stark law features its own safe harbors.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some materials may have been discussed in earlier columns. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. HHS Office of Inspector General. About OIG. https://oig.hhs.gov/about-oig/about-us/index.asp

2. HHS Office of Inspector General. OIG most wanted fugitives.

3. HHS Office of Inspector General. “Physician education training materials.” A roadmap for new physicians: Avoiding Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse.

4. HHS Office of Inspector General. Safe harbor regulations.

Question: Which one of the following statements is incorrect?

A. Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a federal agency of Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that investigates statutory violations of health care fraud and abuse.

B. The three main legal minefields for physicians are false claims, kickbacks, and self-referrals.

C. Jail terms are part of the penalties provided by law.

D. OIG is also responsible for excluding violators from participating in Medicare/Medicaid programs, as well as curtailing a physician’s license to practice.

E. A private citizen can file a qui tam lawsuit against an errant practitioner or health care entity for fraud and abuse.

Answer: D. Health care fraud, waste, and abuse consume some 10% of federal health expenditures despite well-established laws that attempt to prevent and reduce such losses. The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General, as well as the Department of Justice and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are charged with enforcing these and other laws like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. Their web pages, referenced throughout this article, contain a wealth of information for the practitioner.

The term “Office of Inspector General” (OIG) refers to the oversight division of a federal or state agency charged with identifying and investigating fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement within that department or agency. There are currently 73 separate federal offices of inspectors general, which employ armed and unarmed criminal investigators, auditors, forensic auditors called “audigators,” and a variety of other specialists. An Act of Congress in 1976 established the first OIG under HHS. Besides being the first, HHS-OIG is also the largest, with a staff of approximately 1,600. A majority of resources goes toward the oversight of Medicare and Medicaid, as well as programs under other HHS institutions such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration.1

HHS-OIG has the authority to seek civil monetary penalties, assessments, and exclusion against an individual or entity based on a wide variety of prohibited conduct affecting federal health care programs. Stiff penalties are regularly assessed against violators, and jail terms are not uncommon; however, it has no direct jurisdictions over physician licensure or nonfederal programs. The government maintains a pictorial list of its most wanted health care fugitives2 and provides an excellent set of Physician Education Training Materials on its website.3

False Claims Act (FCA)

In the health care arena, violation of FCA (31 U.S.C. §§3729-3733) is the foremost infraction. False claims by physicians can include billing for noncovered services such as experimental treatments, double billing, billing the government as the primary payer, or regularly waiving deductibles and copayments, as well as quality of care issues and unnecessary services. Wrongdoing also includes knowingly using another patient’s name for purposes of, say, federal drug coverage, billing for no-shows, and misrepresenting the diagnosis to justify services, as well as other claims. In the modern doctor’s office, the EMR enables easy check-offs on a preprinted form as documentation of actual work done. However, fraud is implicated if the information is deliberately misleading such as for purposes of upcoding. Importantly, physicians are liable for the actions of their office staff, so it is prudent to oversee and supervise all such activities. Naturally, one should document all claims that are sent and know the rules for allowable and excluded services.

FCA is an old law that was first enacted in 1863. It imposes liability for submitting a payment demand to the federal government where there is actual or constructive knowledge that the claim is false. Intent to defraud is not a required element but knowing or showing reckless disregard of the truth is. However, an error that is negligently committed is insufficient to constitute a violation. Penalties include treble damages, costs and attorney fees, and fines of $11,000 per false claim, as well as possible imprisonment and criminal fines. A so-called whistle-blower may file a lawsuit on behalf of the government and is entitled to a percentage of any recoveries. Whistle-blowers may be current or ex-business partners, hospital or office staff, patients, or competitors. The fact that a claim results from a kickback or is made in violation of the Stark law (discussed below) may also render it fraudulent, thus creating additional liability under FCA.

HHS-OIG, as well as the Department of Justice, discloses named cases of statutory violations on their websites. A few random 2019 examples include a New York licensed doctor was convicted of nine counts in connection with Oxycodone and Fentanyl diversion scheme; a Newton, Mass., geriatrician agreed to pay $680,000 to resolve allegations that he violated the False Claims Act by submitting inflated claims to Medicare and the Massachusetts Medicaid program (MassHealth) for care rendered to nursing home patients; and two Clermont, Fla., ophthalmologists agreed to pay a combined total of $157,312.32 to resolve allegations that they violated FCA by knowingly billing the government for mutually exclusive eyelid repair surgeries.

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

AKS (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b[b]) is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by federal health care programs. Remuneration includes anything of value and can take many forms besides cash, such as free rent, lavish travel, and excessive compensation for medical directorships or consultancies. Rewarding a referral source may be acceptable in some industries, but is a crime in federal health care programs.

Moreover, the statute covers both the payers of kickbacks (those who offer or pay remuneration) and the recipients of kickbacks. Each party’s intent is a key element of their liability under AKS. Physicians who pay or accept kickbacks face penalties of up to $50,000 per kickback plus three times the amount of the remuneration and criminal prosecution. As an example, a Tulsa, Okla., doctor earlier this year agreed to pay the government $84,666.42 for allegedly accepting illegal kickback payments from a pharmacy, and in another case, a marketer agreed to pay nearly $340,000 for receiving kickbacks in exchange for prescription referrals.

A physician is an attractive target for kickback schemes. The kickback prohibition applies to all sources, even patients. For example, where the Medicare and Medicaid programs require patients to be responsible for copays for services, the health care provider is generally required to collect that money from the patients. Advertising the forgiveness of copayments or routinely waiving these copays would violate AKS. However, one may waive a copayment when a patient cannot afford to pay one or is uninsured. AKS also imposes civil monetary penalties on physicians who offer remuneration to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to influence them to use their services. Note that the government does not need to prove patient harm or financial loss to show that a violation has occurred, and physicians can be guilty even if they rendered services that are medically necessary.

There are so-called safe harbors that protect certain payment and business practices from running afoul of AKS. The rules and requirements are complex, and require full understanding and strict adherence.4

Physician Self-Referral Law

The Physician Self-Referral Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn), commonly referred to as the Stark law, prohibits physicians from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial relationship, unless an exception applies. Financial relationships include both ownership/investment interests and compensation arrangements. A partial list of “designated health services” includes services related to clinical laboratory, physical therapy, radiology, parenteral and enteral supplies, prosthetic devices and supplies, home health care outpatient prescription drugs, and inpatient and outpatient hospital services. This list is not meant to be an exhaustive one.

Stark is a strict liability statute, which means proof of specific intent to violate the law is not required. The law prohibits the submission, or causing the submission, of claims in violation of the law’s restrictions on referrals. Penalties for physicians who violate the Stark law include fines, as well as exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. Like AKS, Stark law features its own safe harbors.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some materials may have been discussed in earlier columns. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. HHS Office of Inspector General. About OIG. https://oig.hhs.gov/about-oig/about-us/index.asp

2. HHS Office of Inspector General. OIG most wanted fugitives.

3. HHS Office of Inspector General. “Physician education training materials.” A roadmap for new physicians: Avoiding Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse.

4. HHS Office of Inspector General. Safe harbor regulations.

Letters From Maine: An albatross or your identity?

The last time I saw her she was coiled up like a garter snake resting comfortable in the old toiletries travel case that was my “black bag” for more than 40 years. Joining her in peaceful solitude were a couple of ear curettes, an insufflator, and a dead pocket flashlight. The Kermit the Frog sticker on her diaphragm was faded to a barely recognizable blur. The chest piece was frozen in the diaphragm position as it had been for several decades. I never felt comfortable using the bell side.

She was the gift from a drug company back when medical students were more interested in freebies than making a statement about conflicts of interest. I have had to change her tubing several times when cracks at the bifurcation would allow me to hear my own breath sounds better than the patient’s. The ear pieces were the originals that I modified to fit my auditory canals more comfortably.

I suspect that many of you have developed a close relationship with your stethoscope, as I did. We were always close. She was either her coiled up in my pants’ pocket or clasped around my neck where she wore through collars at a costly clip. Her chest piece was kept tucked in my shirt to keep it warm for the patients. I never hung her over my shoulders the way physicians do in publicity photos. I always found that practice pretentious and impractical.

If I decided tomorrow to leave the challenges of retirement behind and reopen my practice would it make any sense to go down to the basement and roust out my old stethoscope from her slumber? There are better ways evaluate hearts and lungs and many of them will fit in my pocket just as well as that old stethoscope. Paul Wallach, MD, an executive associate dean at the Indiana University, Indianapolis, predicts that within a decade hand-held ultrasound devices with become part of a routine part of the physical exam (Lindsey Tanner. “Is the stethoscope dying? High-tech rivals pose a challenge.” Associated Press. 2019 Oct 23). Instruction in the use of these devices has already become part of the curriculum in some medical schools.

There have been several studies demonstrating that chest auscultation is a skill that some of us have lost and many others never successfully mastered. As much as I treasure my old stethoscope, is it time to get rid of those albatrosses hanging around our necks? They do bang against desks with a deafening ring. Cute infants and toddlers yank on them while we are trying to listen to their chests. If there are better ways to auscultate chests that will fit in our pockets shouldn’t we be using them?

Well, there is the cost for one thing. But, inevitably the price will come down and portability will go up. If we allow our stethoscopes to become nothing more than nostalgic museum pieces to sit along with the head mirror, What will photographers drape over our shoulders? With very few of us in office practice wearing white coats or scrub suits, we run the risk of losing our identity.

Sadly, I fear we will have to accept the disappearance of the stethoscope as a natural consequence of the technological march. But, it also is an unfortunate reflection of the fact that the art of doing a physical exam is fading. With auscultation and palpation disappearing from our diagnostic tool kit we must be careful to preserve and improve the one skill that is indispensable to the practice of medicine.

And, that is listening to what the patient has to tell us.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The last time I saw her she was coiled up like a garter snake resting comfortable in the old toiletries travel case that was my “black bag” for more than 40 years. Joining her in peaceful solitude were a couple of ear curettes, an insufflator, and a dead pocket flashlight. The Kermit the Frog sticker on her diaphragm was faded to a barely recognizable blur. The chest piece was frozen in the diaphragm position as it had been for several decades. I never felt comfortable using the bell side.

She was the gift from a drug company back when medical students were more interested in freebies than making a statement about conflicts of interest. I have had to change her tubing several times when cracks at the bifurcation would allow me to hear my own breath sounds better than the patient’s. The ear pieces were the originals that I modified to fit my auditory canals more comfortably.

I suspect that many of you have developed a close relationship with your stethoscope, as I did. We were always close. She was either her coiled up in my pants’ pocket or clasped around my neck where she wore through collars at a costly clip. Her chest piece was kept tucked in my shirt to keep it warm for the patients. I never hung her over my shoulders the way physicians do in publicity photos. I always found that practice pretentious and impractical.

If I decided tomorrow to leave the challenges of retirement behind and reopen my practice would it make any sense to go down to the basement and roust out my old stethoscope from her slumber? There are better ways evaluate hearts and lungs and many of them will fit in my pocket just as well as that old stethoscope. Paul Wallach, MD, an executive associate dean at the Indiana University, Indianapolis, predicts that within a decade hand-held ultrasound devices with become part of a routine part of the physical exam (Lindsey Tanner. “Is the stethoscope dying? High-tech rivals pose a challenge.” Associated Press. 2019 Oct 23). Instruction in the use of these devices has already become part of the curriculum in some medical schools.

There have been several studies demonstrating that chest auscultation is a skill that some of us have lost and many others never successfully mastered. As much as I treasure my old stethoscope, is it time to get rid of those albatrosses hanging around our necks? They do bang against desks with a deafening ring. Cute infants and toddlers yank on them while we are trying to listen to their chests. If there are better ways to auscultate chests that will fit in our pockets shouldn’t we be using them?

Well, there is the cost for one thing. But, inevitably the price will come down and portability will go up. If we allow our stethoscopes to become nothing more than nostalgic museum pieces to sit along with the head mirror, What will photographers drape over our shoulders? With very few of us in office practice wearing white coats or scrub suits, we run the risk of losing our identity.

Sadly, I fear we will have to accept the disappearance of the stethoscope as a natural consequence of the technological march. But, it also is an unfortunate reflection of the fact that the art of doing a physical exam is fading. With auscultation and palpation disappearing from our diagnostic tool kit we must be careful to preserve and improve the one skill that is indispensable to the practice of medicine.

And, that is listening to what the patient has to tell us.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The last time I saw her she was coiled up like a garter snake resting comfortable in the old toiletries travel case that was my “black bag” for more than 40 years. Joining her in peaceful solitude were a couple of ear curettes, an insufflator, and a dead pocket flashlight. The Kermit the Frog sticker on her diaphragm was faded to a barely recognizable blur. The chest piece was frozen in the diaphragm position as it had been for several decades. I never felt comfortable using the bell side.

She was the gift from a drug company back when medical students were more interested in freebies than making a statement about conflicts of interest. I have had to change her tubing several times when cracks at the bifurcation would allow me to hear my own breath sounds better than the patient’s. The ear pieces were the originals that I modified to fit my auditory canals more comfortably.

I suspect that many of you have developed a close relationship with your stethoscope, as I did. We were always close. She was either her coiled up in my pants’ pocket or clasped around my neck where she wore through collars at a costly clip. Her chest piece was kept tucked in my shirt to keep it warm for the patients. I never hung her over my shoulders the way physicians do in publicity photos. I always found that practice pretentious and impractical.

If I decided tomorrow to leave the challenges of retirement behind and reopen my practice would it make any sense to go down to the basement and roust out my old stethoscope from her slumber? There are better ways evaluate hearts and lungs and many of them will fit in my pocket just as well as that old stethoscope. Paul Wallach, MD, an executive associate dean at the Indiana University, Indianapolis, predicts that within a decade hand-held ultrasound devices with become part of a routine part of the physical exam (Lindsey Tanner. “Is the stethoscope dying? High-tech rivals pose a challenge.” Associated Press. 2019 Oct 23). Instruction in the use of these devices has already become part of the curriculum in some medical schools.

There have been several studies demonstrating that chest auscultation is a skill that some of us have lost and many others never successfully mastered. As much as I treasure my old stethoscope, is it time to get rid of those albatrosses hanging around our necks? They do bang against desks with a deafening ring. Cute infants and toddlers yank on them while we are trying to listen to their chests. If there are better ways to auscultate chests that will fit in our pockets shouldn’t we be using them?

Well, there is the cost for one thing. But, inevitably the price will come down and portability will go up. If we allow our stethoscopes to become nothing more than nostalgic museum pieces to sit along with the head mirror, What will photographers drape over our shoulders? With very few of us in office practice wearing white coats or scrub suits, we run the risk of losing our identity.

Sadly, I fear we will have to accept the disappearance of the stethoscope as a natural consequence of the technological march. But, it also is an unfortunate reflection of the fact that the art of doing a physical exam is fading. With auscultation and palpation disappearing from our diagnostic tool kit we must be careful to preserve and improve the one skill that is indispensable to the practice of medicine.

And, that is listening to what the patient has to tell us.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Long-term care insurance

A few years ago, my seemingly indestructible 94-year-old mother suffered a series of medical setbacks. As her health problems accumulated, so did the complexity and cost of her care, progressing from her home to an assisted-living facility to a nursing home. It was heartbreaking – and expensive. My wife likened it to “putting another kid through college” – an elite private college, at that.

Medicare, of course, did not cover any of this, except for physician visits and some of her medications. When it was finally over, my wife and I resolved that, should we face a similar situation in our final years, we could not put ourselves or our children through a similar financial ordeal.

, in-home services, and other end-of-life expenses. (Covered services vary by policy; and as always, I have no financial interest in any product or service mentioned here.)

According to the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI), the average annual LTCI premium for a 60-year-old couple is $3,490. Not cheap; but there are ways to lower premiums without gutting your coverage.

The best way to keep costs down is to get in early. In general, the younger you are and the better health you are in, the lower your premiums will be. For example – again according to the AALTCI – that “average” annual premium of $3,490 for a hypothetical 60-year-old couple would increase 34%, to $4,675, if they waited until they were 65 to buy the policy. And if their health were to decline in the interim, they might not be able to obtain adequate coverage at all.

You can also lower premiums by decreasing daily benefits, or increasing the “elimination period” – the length of time after you become eligible for benefits that the policy starts paying them; 30-, 60-, and 90-day periods are common. As long as you have sufficient savings to realistically cover costs until the elimination period is over, choosing a longer one can reduce your costs significantly.

Another variable is the maximum length of time the policy will pay out benefits. Ideally, you would want a payout to continue for as long as necessary, but few if any companies are willing to write uncapped policies anymore. Two to five years of benefits is a common time frame. (The “average” premiums quoted above assume a benefit of $150 per day with a 3-year cap and a 90-day elimination period.)

As with any insurance, it is important not to overbuy LTCI. It isn’t necessary to obtain coverage that will pay for 100% of your long-term care costs – just the portion that your projected retirement income (Social Security, pensions, income from savings) may not be sufficient to cover. Buying only the amount of coverage you need will substantially reduce your premium costs over the life of the policy.

If you work for a hospital or a large group, it’s worth checking to see if your employer offers LTCI. Employer-sponsored plans are often offered at discounted group rates, and you can usually keep the policy even if you leave. If you’re a member of any social or religious groups, check their insurance plans as well.

To be sure, there is considerable debate about whether LTCI is worth the cost. Premiums for new policies are rising at a steep clip – 9% annually, according to the AALTCI – and insurers are allowed to raise premiums even after you buy the policy, so you’ll need to factor that possibility into your budget.

But forgoing coverage can be costly too: If you know you will have to cover your own long-term care costs, you won’t be able to spend that money on things you really care about – like your grandkids, or travel, or charitable work. You might even forgo necessary medical care for fear of running out of money.

Everyone must make their own decision. My wife and I decided that a few thousand dollars per year is a fair price to pay for the peace of mind of knowing we will be able to afford proper supportive care, without help from our children or anyone else, regardless of what happens in the years to come.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

A few years ago, my seemingly indestructible 94-year-old mother suffered a series of medical setbacks. As her health problems accumulated, so did the complexity and cost of her care, progressing from her home to an assisted-living facility to a nursing home. It was heartbreaking – and expensive. My wife likened it to “putting another kid through college” – an elite private college, at that.

Medicare, of course, did not cover any of this, except for physician visits and some of her medications. When it was finally over, my wife and I resolved that, should we face a similar situation in our final years, we could not put ourselves or our children through a similar financial ordeal.

, in-home services, and other end-of-life expenses. (Covered services vary by policy; and as always, I have no financial interest in any product or service mentioned here.)

According to the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI), the average annual LTCI premium for a 60-year-old couple is $3,490. Not cheap; but there are ways to lower premiums without gutting your coverage.

The best way to keep costs down is to get in early. In general, the younger you are and the better health you are in, the lower your premiums will be. For example – again according to the AALTCI – that “average” annual premium of $3,490 for a hypothetical 60-year-old couple would increase 34%, to $4,675, if they waited until they were 65 to buy the policy. And if their health were to decline in the interim, they might not be able to obtain adequate coverage at all.

You can also lower premiums by decreasing daily benefits, or increasing the “elimination period” – the length of time after you become eligible for benefits that the policy starts paying them; 30-, 60-, and 90-day periods are common. As long as you have sufficient savings to realistically cover costs until the elimination period is over, choosing a longer one can reduce your costs significantly.

Another variable is the maximum length of time the policy will pay out benefits. Ideally, you would want a payout to continue for as long as necessary, but few if any companies are willing to write uncapped policies anymore. Two to five years of benefits is a common time frame. (The “average” premiums quoted above assume a benefit of $150 per day with a 3-year cap and a 90-day elimination period.)

As with any insurance, it is important not to overbuy LTCI. It isn’t necessary to obtain coverage that will pay for 100% of your long-term care costs – just the portion that your projected retirement income (Social Security, pensions, income from savings) may not be sufficient to cover. Buying only the amount of coverage you need will substantially reduce your premium costs over the life of the policy.

If you work for a hospital or a large group, it’s worth checking to see if your employer offers LTCI. Employer-sponsored plans are often offered at discounted group rates, and you can usually keep the policy even if you leave. If you’re a member of any social or religious groups, check their insurance plans as well.

To be sure, there is considerable debate about whether LTCI is worth the cost. Premiums for new policies are rising at a steep clip – 9% annually, according to the AALTCI – and insurers are allowed to raise premiums even after you buy the policy, so you’ll need to factor that possibility into your budget.

But forgoing coverage can be costly too: If you know you will have to cover your own long-term care costs, you won’t be able to spend that money on things you really care about – like your grandkids, or travel, or charitable work. You might even forgo necessary medical care for fear of running out of money.

Everyone must make their own decision. My wife and I decided that a few thousand dollars per year is a fair price to pay for the peace of mind of knowing we will be able to afford proper supportive care, without help from our children or anyone else, regardless of what happens in the years to come.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

A few years ago, my seemingly indestructible 94-year-old mother suffered a series of medical setbacks. As her health problems accumulated, so did the complexity and cost of her care, progressing from her home to an assisted-living facility to a nursing home. It was heartbreaking – and expensive. My wife likened it to “putting another kid through college” – an elite private college, at that.

Medicare, of course, did not cover any of this, except for physician visits and some of her medications. When it was finally over, my wife and I resolved that, should we face a similar situation in our final years, we could not put ourselves or our children through a similar financial ordeal.

, in-home services, and other end-of-life expenses. (Covered services vary by policy; and as always, I have no financial interest in any product or service mentioned here.)

According to the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI), the average annual LTCI premium for a 60-year-old couple is $3,490. Not cheap; but there are ways to lower premiums without gutting your coverage.

The best way to keep costs down is to get in early. In general, the younger you are and the better health you are in, the lower your premiums will be. For example – again according to the AALTCI – that “average” annual premium of $3,490 for a hypothetical 60-year-old couple would increase 34%, to $4,675, if they waited until they were 65 to buy the policy. And if their health were to decline in the interim, they might not be able to obtain adequate coverage at all.

You can also lower premiums by decreasing daily benefits, or increasing the “elimination period” – the length of time after you become eligible for benefits that the policy starts paying them; 30-, 60-, and 90-day periods are common. As long as you have sufficient savings to realistically cover costs until the elimination period is over, choosing a longer one can reduce your costs significantly.

Another variable is the maximum length of time the policy will pay out benefits. Ideally, you would want a payout to continue for as long as necessary, but few if any companies are willing to write uncapped policies anymore. Two to five years of benefits is a common time frame. (The “average” premiums quoted above assume a benefit of $150 per day with a 3-year cap and a 90-day elimination period.)

As with any insurance, it is important not to overbuy LTCI. It isn’t necessary to obtain coverage that will pay for 100% of your long-term care costs – just the portion that your projected retirement income (Social Security, pensions, income from savings) may not be sufficient to cover. Buying only the amount of coverage you need will substantially reduce your premium costs over the life of the policy.

If you work for a hospital or a large group, it’s worth checking to see if your employer offers LTCI. Employer-sponsored plans are often offered at discounted group rates, and you can usually keep the policy even if you leave. If you’re a member of any social or religious groups, check their insurance plans as well.

To be sure, there is considerable debate about whether LTCI is worth the cost. Premiums for new policies are rising at a steep clip – 9% annually, according to the AALTCI – and insurers are allowed to raise premiums even after you buy the policy, so you’ll need to factor that possibility into your budget.

But forgoing coverage can be costly too: If you know you will have to cover your own long-term care costs, you won’t be able to spend that money on things you really care about – like your grandkids, or travel, or charitable work. You might even forgo necessary medical care for fear of running out of money.

Everyone must make their own decision. My wife and I decided that a few thousand dollars per year is a fair price to pay for the peace of mind of knowing we will be able to afford proper supportive care, without help from our children or anyone else, regardless of what happens in the years to come.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Don’t let a foodborne illness dampen the holiday season

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a foodborne disease occurs in one in six persons (48 million), resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths annually in the United States. The Foodborne Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program monitors cases of eight laboratory diagnosed infections from 10 U.S. sites (covering 15% of the U.S. population). Monitored organisms include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia. In 2018, FoodNet identified 25,606 cases of infection, 5,893 hospitalizations, and 120 deaths. The incidence of infection (cases/100,000) was highest for Campylobacter (20), Salmonella (18), STEC (6), Shigella (5), Vibrio (1), Yersinia (0.9), Cyclospora (0.7), and Listeria (0.3). How might these pathogens affect your patients? First, a quick review about the four more common infections. Treatment is beyond the scope of our discussion and you are referred to the 2018-2021 Red Book for assistance. The goal of this column is to prevent your patients from becoming a statistic this holiday season.

Campylobacter

It has been the most common infection reported in FoodNet since 2013. Clinically, patients present with fever, abdominal pain, and nonbloody diarrhea. However, bloody diarrhea maybe the only symptom in neonates and young infants. Abdominal pain can mimic acute appendicitis or intussusception. Bacteremia is rare but has been reported in the elderly and in some patients with underlying conditions. During convalescence, immunoreactive complications including Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis, and erythema nodosum may occur. In patients with diarrhea, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli are the most frequently isolated species.

Campylobacter is present in the intestinal tract of both domestic and wild birds and animals. Transmission is via consumption of contaminated food or water. Undercooked poultry, untreated water, and unpasteurized milk are the three main vehicles of transmission. Campylobacter can be isolated in stool and blood, however isolation from stool requires special media. Rehydration is the primary therapy. Use of azithromycin or erythromycin can shorten both the duration of symptoms and bacterial shedding.

Salmonella

Nontyphoidal salmonella (NTS) are responsible for a variety of infections including asymptomatic carriage, gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and serious focal infections. Gastroenteritis is the most common illness and is manifested as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. If bacteremia occurs, up to 10% of patients will develop focal infections. Invasive disease occurs most frequently in infants, persons with hemoglobinopathies, immunosuppressive disorders, and malignancies. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species, S. enterica and S. bongori with S. enterica subspecies accounting for about half of culture-confirmed Salmonella isolates reported by public health laboratories.

Although infections are more common in the summer, infections can occur year-round. In 2018, the CDC investigated at least 15 food-related NTS outbreaks and 6 have been investigated so far in 2019. In industrialized countries, acquisition usually occurs from ingestion of poultry, eggs, and milk products. Infection also has been reported after animal contact and consumption of fresh produce, meats, and contaminated water. Ground beef is the source of the November 2019 outbreak of S. dublin. Diarrhea develops within 12-72 hours. Salmonella can be isolated from stool, blood, and urine. Treatment usually is not indicated for uncomplicated gastroenteritis. While benefit has not been proven, it is recommended for those at increased risk for developing invasive disease.

Shigella

Shigella is the classic cause of colonic or dysenteric diarrhea. Humans are the primary hosts but other primates can be infected. Transmission occurs through direct person-to-person spread, from ingestion of contaminated food and water, and contact with contaminated inanimate objects. Bacteria can survive up to 6 months in food and 30 days in water. As few as 10 organisms can initiate disease. Typically mucoid or bloody diarrhea with abdominal cramps and fever occurs 1-7 days following exposure. Isolation is from stool. Bacteremia is unusual. Therapy is recommended for severe disease.

Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC)

STEC causes hemorrhagic colitis, which can be complicated by hemolytic uremic syndrome. While E. coli O157:H7 is the serotype most often implicated, other serotypes can cause disease. STEC is shed in feces of cattle and other animals. Infection most often is associated with ingestion of undercooked ground beef, but outbreaks also have confirmed that contaminated leafy vegetables, drinking water, peanut butter, and unpasteurized milk have been the source. Symptoms usually develop 3 to 4 days after exposure. Stools initially may be nonbloody. Abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea occur over the next 2-3 days. Fever often is absent or low grade. Stools should be sent for culture and Shiga toxin for diagnosis. Antimicrobial treatment generally is not warranted if STEC is suspected or diagnosed.

Prevention

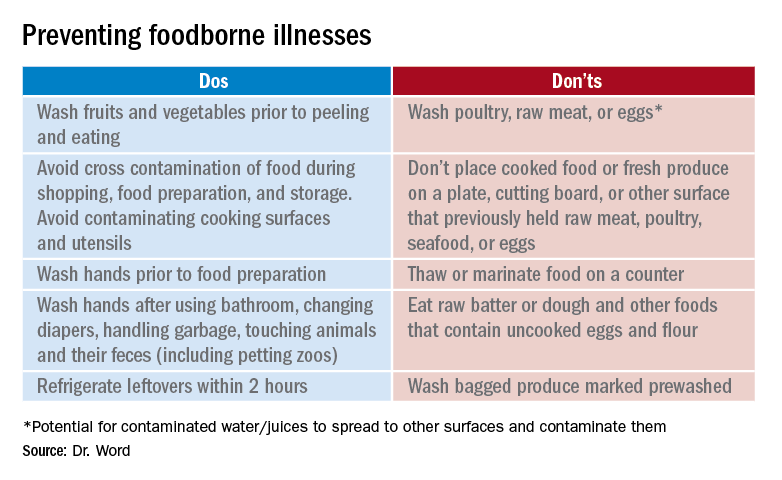

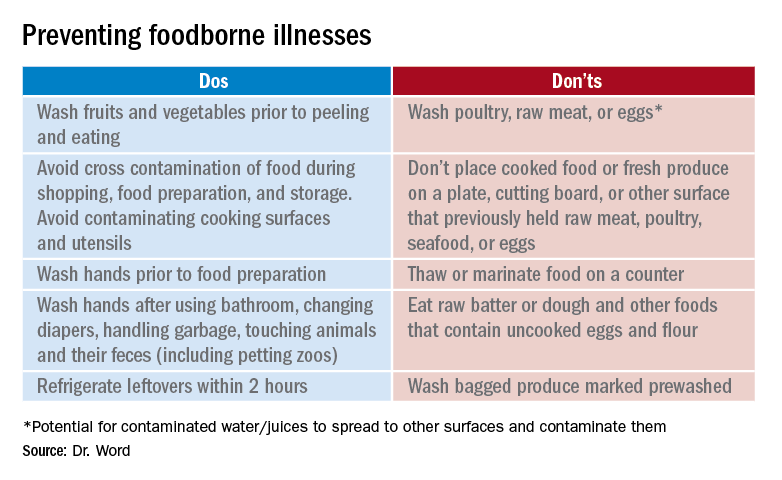

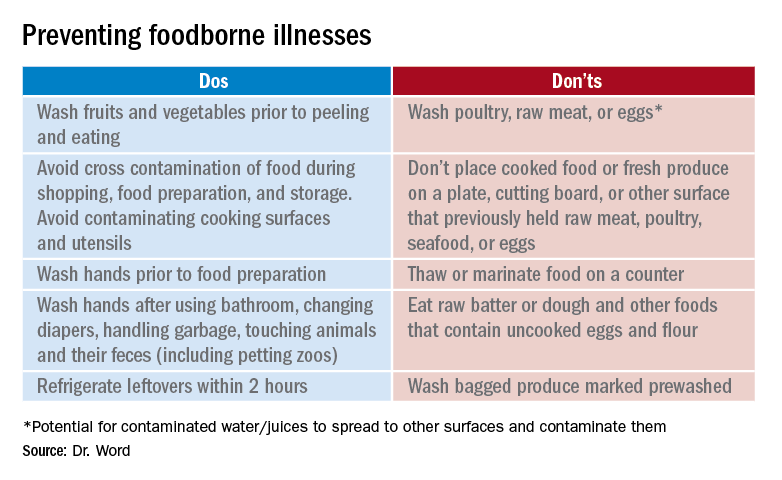

It seems so simple. Here are the basic guidelines:

- Clean. Wash hands and surfaces frequently.

- Separate. Separate raw meats and eggs from other foods.

- Cook. Cook all meats to the right temperature.

- Chill. Refrigerate food properly.

Finally, two comments about food poisoning:

Abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping due to staphylococcal food poisoning begins 30 minutes to 6 hours after ingestion of food contaminated by enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus which is usually introduced by a food preparer with a purulent lesion. Food left at room temperature allows bacteria to multiply and produce a heat stable toxin. Individuals with purulent lesions of the hands, face, eyes, or nose should not be involved with food preparation.

Clostridium perfringens is the second most common bacterial cause of food poisoning. Symptoms (watery diarrhea and cramping) begin 6-24 hours after ingestion of C. perfringens spores not killed during cooking, which now have multiplied in food left at room temperature that was inadequately reheated. Illness is caused by the production of enterotoxin in the intestine. Outbreaks occur most often in November and December.

This article was updated on 11/12/19.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Information sources

1. foodsafety.gov

2. cdc.gov/foodsafety

3. The United States Department of Agriculture Meat and Poultry Hotline: 888-674-6854

4. Appendix VII: Clinical syndromes associated with foodborne diseases, Red Book online, 31st ed. (Washington DC: Red Book online, 2018, pp. 1086-92).

5. Foodkeeper App available at the App store. Provides appropriate food storage information; food recalls also are available.