User login

Prescribing medications in an emergency situation? Document your rationale

Emergent medication use is indicated in numerous clinical scenarios, including psychotic agitation, physical aggression, or withdrawal from substances. While there is plenty of literature to help clinicians with medical record documentation in various other settings,1-3 there is minimal guidance on how to document your rationale for using psychiatric medications in emergency situations.

I have designed a template for structuring progress notes that has helped me to quickly explain my decision-making for using psychiatric medications during an emergency. When writing a progress note to justify your clinical actions in these situations, ask yourself the following questions:

- What symptoms/behaviors needed to be emergently treated? (Use direct quotes from the patient.)

- Which nonpharmacologic interventions were attempted prior to using a medication?

- Does the patient have any medication allergies? (Document if you were unable to assess for allergies.)

- Why did you select this specific route for medication administration?

- What was your rationale for using the specific medication(s)?

- What was the rationale for the selected dose?

- Who was present during medication administration?

- Which (if any) concurrent interventions did you order during or after medication administration?

- Were any safety follow-up checks ordered after medication administration?

A sample progress note

To help illustrate how these questions could guide a clinician’s writing, the following is a progress note I created using this template:

“Patient woke up at 3:15

1. Gutheil TG. Fundamentals of medical record documentation. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2004;1(3):26-28.

2. Guth T, Morrissey T. Medical documentation and ED charting. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine. https://saem.org/cdem/education/online-education/m3-curriculum/documentation/documentation-of-em-encounters. Updated 2015. Accessed October 10, 2019.

3. Aftab A, Latorre S, Nagle-Yang S. Effective note-writing: a primer for psychiatry residents. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/couch-crisis/effective-note-writing-primer-psychiatry-residents. Published January 13, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2019.

Emergent medication use is indicated in numerous clinical scenarios, including psychotic agitation, physical aggression, or withdrawal from substances. While there is plenty of literature to help clinicians with medical record documentation in various other settings,1-3 there is minimal guidance on how to document your rationale for using psychiatric medications in emergency situations.

I have designed a template for structuring progress notes that has helped me to quickly explain my decision-making for using psychiatric medications during an emergency. When writing a progress note to justify your clinical actions in these situations, ask yourself the following questions:

- What symptoms/behaviors needed to be emergently treated? (Use direct quotes from the patient.)

- Which nonpharmacologic interventions were attempted prior to using a medication?

- Does the patient have any medication allergies? (Document if you were unable to assess for allergies.)

- Why did you select this specific route for medication administration?

- What was your rationale for using the specific medication(s)?

- What was the rationale for the selected dose?

- Who was present during medication administration?

- Which (if any) concurrent interventions did you order during or after medication administration?

- Were any safety follow-up checks ordered after medication administration?

A sample progress note

To help illustrate how these questions could guide a clinician’s writing, the following is a progress note I created using this template:

“Patient woke up at 3:15

Emergent medication use is indicated in numerous clinical scenarios, including psychotic agitation, physical aggression, or withdrawal from substances. While there is plenty of literature to help clinicians with medical record documentation in various other settings,1-3 there is minimal guidance on how to document your rationale for using psychiatric medications in emergency situations.

I have designed a template for structuring progress notes that has helped me to quickly explain my decision-making for using psychiatric medications during an emergency. When writing a progress note to justify your clinical actions in these situations, ask yourself the following questions:

- What symptoms/behaviors needed to be emergently treated? (Use direct quotes from the patient.)

- Which nonpharmacologic interventions were attempted prior to using a medication?

- Does the patient have any medication allergies? (Document if you were unable to assess for allergies.)

- Why did you select this specific route for medication administration?

- What was your rationale for using the specific medication(s)?

- What was the rationale for the selected dose?

- Who was present during medication administration?

- Which (if any) concurrent interventions did you order during or after medication administration?

- Were any safety follow-up checks ordered after medication administration?

A sample progress note

To help illustrate how these questions could guide a clinician’s writing, the following is a progress note I created using this template:

“Patient woke up at 3:15

1. Gutheil TG. Fundamentals of medical record documentation. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2004;1(3):26-28.

2. Guth T, Morrissey T. Medical documentation and ED charting. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine. https://saem.org/cdem/education/online-education/m3-curriculum/documentation/documentation-of-em-encounters. Updated 2015. Accessed October 10, 2019.

3. Aftab A, Latorre S, Nagle-Yang S. Effective note-writing: a primer for psychiatry residents. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/couch-crisis/effective-note-writing-primer-psychiatry-residents. Published January 13, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2019.

1. Gutheil TG. Fundamentals of medical record documentation. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2004;1(3):26-28.

2. Guth T, Morrissey T. Medical documentation and ED charting. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine. https://saem.org/cdem/education/online-education/m3-curriculum/documentation/documentation-of-em-encounters. Updated 2015. Accessed October 10, 2019.

3. Aftab A, Latorre S, Nagle-Yang S. Effective note-writing: a primer for psychiatry residents. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/couch-crisis/effective-note-writing-primer-psychiatry-residents. Published January 13, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2019.

Dealing with deception: How to manage patients who are ‘faking it’

Patients who fabricate or exaggerate psychiatric symptoms for primary or secondary gain may elicit negative responses from health care professionals. As clinicians, we may believe that such patients are wasting our time and taking resources away from other patients who are genuinely struggling with mental illness and are more deserving of assistance. However, patients who are fabricating or exaggerating their symptoms have legitimate clinical needs that we should strive to understand. If we view them as having reasons for their actions without becoming complicit in their deception, we may find it easier to work with them.

Managing patients who are fabricating or exaggerating

Caring for patients who attempt to mislead us is a challenging proposition. The relevant research is scarce, and there are few recommended interventions for managing patients who fabricate or exaggerate symptoms.1 Direct confrontation and accusation are often unproductive and should be used sparingly. Indirect approaches tend to be more effective.

It is important to manage our countertransference at the outset while establishing and maintaining rapport. Although we may become frustrated, we should avoid using sarcasm or overt skepticism; instead, we should validate these patients’ emotions because their emotional turmoil could be driving their fabrication or exaggeration. We should attempt to explore their specific motivations by focusing our questions on detecting the underlying stressors or conditions.2

To assess our patients’ motives, consider asking the following:

- What kind of problems have these symptoms caused you in your day-to-day life?

- What would make life better for you?

- What are you hoping I can do for you today?

We should ask open-ended questions as well as interview patients over a long period of time and on multiple occasions to observe the consistency of their reported symptoms. In addition, we should take good notes and document our observations to compare what our patients tell us during their appointments.

Addressing inconsistencies

While exploring our patients’ motives, when it is appropriate, we can gently confront discrepancies in their report by asking:

- I am confused about your symptoms. Help me understand what is happening. Can you tell me more? (Then ask specific follow-up questions based on their answer.)

- What do you mean when you say you are experiencing this symptom?

- I am not sure if I understand what you said correctly. These symptoms do not typically occur in the way that you described. Could you tell me more?

- The symptoms you described are unusual to me. Is there something else going on that I am not aware of?

- Do you think these symptoms have been coming up because you are under stress?

- Is it possible that you want to (avoid work, avoid jail, be prescribed a specific medication, etc.) and that this is the only way you could think of to get what you need?

- Is it possible that you are describing what you are experiencing so that you can convince others that you are having problems?

Despite our best efforts, some patients may not drop their guard and will continue to fabricate or exaggerate their symptoms. However, establishing and maintaining rapport, exploring our patients’ potential motives to mislead, and gently confronting discrepancies in their report may maximize the chances of successfully engaging them and developing appropriate treatment plans.

1. Brady MC, Scher LM, Newman W. “I just saw Big Bird. He was 100 feet tall!” Malingering in the emergency room. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(10):33-40.

2. Schnellbacher S, O’Mara H. Identifying and managing malingering and factitious disorder in the military. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(11):105.

Patients who fabricate or exaggerate psychiatric symptoms for primary or secondary gain may elicit negative responses from health care professionals. As clinicians, we may believe that such patients are wasting our time and taking resources away from other patients who are genuinely struggling with mental illness and are more deserving of assistance. However, patients who are fabricating or exaggerating their symptoms have legitimate clinical needs that we should strive to understand. If we view them as having reasons for their actions without becoming complicit in their deception, we may find it easier to work with them.

Managing patients who are fabricating or exaggerating

Caring for patients who attempt to mislead us is a challenging proposition. The relevant research is scarce, and there are few recommended interventions for managing patients who fabricate or exaggerate symptoms.1 Direct confrontation and accusation are often unproductive and should be used sparingly. Indirect approaches tend to be more effective.

It is important to manage our countertransference at the outset while establishing and maintaining rapport. Although we may become frustrated, we should avoid using sarcasm or overt skepticism; instead, we should validate these patients’ emotions because their emotional turmoil could be driving their fabrication or exaggeration. We should attempt to explore their specific motivations by focusing our questions on detecting the underlying stressors or conditions.2

To assess our patients’ motives, consider asking the following:

- What kind of problems have these symptoms caused you in your day-to-day life?

- What would make life better for you?

- What are you hoping I can do for you today?

We should ask open-ended questions as well as interview patients over a long period of time and on multiple occasions to observe the consistency of their reported symptoms. In addition, we should take good notes and document our observations to compare what our patients tell us during their appointments.

Addressing inconsistencies

While exploring our patients’ motives, when it is appropriate, we can gently confront discrepancies in their report by asking:

- I am confused about your symptoms. Help me understand what is happening. Can you tell me more? (Then ask specific follow-up questions based on their answer.)

- What do you mean when you say you are experiencing this symptom?

- I am not sure if I understand what you said correctly. These symptoms do not typically occur in the way that you described. Could you tell me more?

- The symptoms you described are unusual to me. Is there something else going on that I am not aware of?

- Do you think these symptoms have been coming up because you are under stress?

- Is it possible that you want to (avoid work, avoid jail, be prescribed a specific medication, etc.) and that this is the only way you could think of to get what you need?

- Is it possible that you are describing what you are experiencing so that you can convince others that you are having problems?

Despite our best efforts, some patients may not drop their guard and will continue to fabricate or exaggerate their symptoms. However, establishing and maintaining rapport, exploring our patients’ potential motives to mislead, and gently confronting discrepancies in their report may maximize the chances of successfully engaging them and developing appropriate treatment plans.

Patients who fabricate or exaggerate psychiatric symptoms for primary or secondary gain may elicit negative responses from health care professionals. As clinicians, we may believe that such patients are wasting our time and taking resources away from other patients who are genuinely struggling with mental illness and are more deserving of assistance. However, patients who are fabricating or exaggerating their symptoms have legitimate clinical needs that we should strive to understand. If we view them as having reasons for their actions without becoming complicit in their deception, we may find it easier to work with them.

Managing patients who are fabricating or exaggerating

Caring for patients who attempt to mislead us is a challenging proposition. The relevant research is scarce, and there are few recommended interventions for managing patients who fabricate or exaggerate symptoms.1 Direct confrontation and accusation are often unproductive and should be used sparingly. Indirect approaches tend to be more effective.

It is important to manage our countertransference at the outset while establishing and maintaining rapport. Although we may become frustrated, we should avoid using sarcasm or overt skepticism; instead, we should validate these patients’ emotions because their emotional turmoil could be driving their fabrication or exaggeration. We should attempt to explore their specific motivations by focusing our questions on detecting the underlying stressors or conditions.2

To assess our patients’ motives, consider asking the following:

- What kind of problems have these symptoms caused you in your day-to-day life?

- What would make life better for you?

- What are you hoping I can do for you today?

We should ask open-ended questions as well as interview patients over a long period of time and on multiple occasions to observe the consistency of their reported symptoms. In addition, we should take good notes and document our observations to compare what our patients tell us during their appointments.

Addressing inconsistencies

While exploring our patients’ motives, when it is appropriate, we can gently confront discrepancies in their report by asking:

- I am confused about your symptoms. Help me understand what is happening. Can you tell me more? (Then ask specific follow-up questions based on their answer.)

- What do you mean when you say you are experiencing this symptom?

- I am not sure if I understand what you said correctly. These symptoms do not typically occur in the way that you described. Could you tell me more?

- The symptoms you described are unusual to me. Is there something else going on that I am not aware of?

- Do you think these symptoms have been coming up because you are under stress?

- Is it possible that you want to (avoid work, avoid jail, be prescribed a specific medication, etc.) and that this is the only way you could think of to get what you need?

- Is it possible that you are describing what you are experiencing so that you can convince others that you are having problems?

Despite our best efforts, some patients may not drop their guard and will continue to fabricate or exaggerate their symptoms. However, establishing and maintaining rapport, exploring our patients’ potential motives to mislead, and gently confronting discrepancies in their report may maximize the chances of successfully engaging them and developing appropriate treatment plans.

1. Brady MC, Scher LM, Newman W. “I just saw Big Bird. He was 100 feet tall!” Malingering in the emergency room. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(10):33-40.

2. Schnellbacher S, O’Mara H. Identifying and managing malingering and factitious disorder in the military. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(11):105.

1. Brady MC, Scher LM, Newman W. “I just saw Big Bird. He was 100 feet tall!” Malingering in the emergency room. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(10):33-40.

2. Schnellbacher S, O’Mara H. Identifying and managing malingering and factitious disorder in the military. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(11):105.

Recognizing and treating ketamine abuse

The N-methyl-

Physicians need to be aware, however, that many patients use illicit ketamine, either for recreational purposes or as self-treatment to control depressive symptoms. To help clinicians identify the signs of ketamine abuse, we discuss the adverse effects of illicit use, and suggest treatment approaches.

Ad

Ketamine can be consumed in various ways; snorting it in a powder form is a preferred route for recreational use.2 The primary disadvantage of oral use is that it increases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting.2

While ketamine is generally safe in a supervised clinical setting, approximately 2.5 million individuals use various illicit forms of ketamine—which is known as Special K and by other names—in recreational settings (eg, dance clubs) where it might be used with other substances.3 Alcohol, in particular, compounds the sedative effects of ketamine and can lead to death by overdose.

At a subanesthetic dose, ketamine can induce dissociative and/or transcendental states that are particularly attractive to those intrigued by mystical experiences, pronounced changes in perception, or euphoria.4 High doses of ketamine—relative to a commonly used recreational dose—can produce a unique “K-hole” state in which a user is unable to control his/her body and could lose consciousness.5 A K-hole state may trigger a cycle of delirium that warrants immediate clinical attention.3

Researchers have postulated that NMDA antagonism may negatively impact memory consolidation.3,6 Even more troubling is the potential for systemic injuries because illicit ketamine use may contribute to ulcerative cystitis, severely disturbed kidney function (eg, hydronephrosis), or epigastric pain.3 Chronic abuse tends to result in more systemic sequelae, affecting the bladder, kidneys, and heart. Adverse effects that require emergent care include blood in urine, changes in vision (eg, nystagmus), chest discomfort, labored breathing, agitation, seizures, and/or altered consciousness.6

Treating ketamine abuse

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s symptoms. If the patient presents with “K-bladder” (ie, ketamine bladder syndrome), he/she may need surgical intervention or a cystectomy.4,7 Therapeutic management of K-bladder entails recognizing bladder symptoms that are specific to ketamine use, such as interstitial or ulcerative cystitis and lower urinary tract symptoms.7 Clinicians should monitor patients for increased voiding episodes during the day, voiding urgency, or a general sense of bladder fullness. Patients with K-bladder also may complain of suprapubic pain or blood in the urine.7

Continue to: Consider referring patients to...

Consider referring patients to an individualized, ketamine-specific rehabilitation program that is modeled after other substance-specific rehabilitation programs. It is critical to address withdrawal symptoms (eg, anorexia, fatigue, tremors, chills, tachycardia, nightmares, etc.). Patients undergoing ketamine withdrawal may develop anxiety and depression, with or without suicidal ideation, that might persist during a 4- to 5-day withdrawal period.8

‘Self-medicating’ ketamine users

Clinicians need to be particularly vigilant for situations in which a patient has used ketamine in an attempt to control his/her depressive symptoms. Some researchers have described ketamine as a revolutionary drug for TRD, and it is reasonable to suspect that some patients with depressive symptoms may have consulted Internet sources to learn how to self-medicate using ketamine. Patients who have consumed smaller doses of ketamine recreationally may have developed a tolerance in which the receptors are no longer responsive to the effects at that dose, and therefore might not respond when given ketamine in a clinical setting. Proper history taking and patient education are essential for these users, and clinicians may need to develop a personalized therapeutic plan for ketamine administration. If, on the other hand, a patient has a history of chronic ketamine use (perhaps at high doses), depression may occur secondary to this type of ketamine abuse. For such patients, clinicians should explore alternative treatment modalities, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation.

1. Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283-290.

2. Davis K. What are the uses of ketamine? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/302663.php. Updated October 12, 2017. Published October 11, 2019.

3. Chaverneff F. Ketamine: mechanisms of action, uses in pain medicine, and side effects. Clinical Pain Advisor. https://www.clinicalpainadvisor.com/home/conference-highlights/painweek-2018/ketamine-mechanisms-of-action-uses-in-pain-medicine-and-side-effects/. Published 2018. Accessed October 11, 2019.

4. Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):865-872.

5. Orhurhu VJ, Claus LE, Cohen SP. Ketamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087. Updated April 11, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019.

6. Pai A, Heining M. Ketamine. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 20071;7(2):59-63.

7. Logan K. Addressing ketamine bladder syndrome. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/medicine-management/addressing-ketamine-bladder-syndrome-19-06-2011/. Published June 19, 2011. Accessed October 11, 2019.

8. Lin PC, Lane HY, Lin CH. Spontaneous remission of ketamine withdrawal-related depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(1):51-52.

The N-methyl-

Physicians need to be aware, however, that many patients use illicit ketamine, either for recreational purposes or as self-treatment to control depressive symptoms. To help clinicians identify the signs of ketamine abuse, we discuss the adverse effects of illicit use, and suggest treatment approaches.

Ad

Ketamine can be consumed in various ways; snorting it in a powder form is a preferred route for recreational use.2 The primary disadvantage of oral use is that it increases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting.2

While ketamine is generally safe in a supervised clinical setting, approximately 2.5 million individuals use various illicit forms of ketamine—which is known as Special K and by other names—in recreational settings (eg, dance clubs) where it might be used with other substances.3 Alcohol, in particular, compounds the sedative effects of ketamine and can lead to death by overdose.

At a subanesthetic dose, ketamine can induce dissociative and/or transcendental states that are particularly attractive to those intrigued by mystical experiences, pronounced changes in perception, or euphoria.4 High doses of ketamine—relative to a commonly used recreational dose—can produce a unique “K-hole” state in which a user is unable to control his/her body and could lose consciousness.5 A K-hole state may trigger a cycle of delirium that warrants immediate clinical attention.3

Researchers have postulated that NMDA antagonism may negatively impact memory consolidation.3,6 Even more troubling is the potential for systemic injuries because illicit ketamine use may contribute to ulcerative cystitis, severely disturbed kidney function (eg, hydronephrosis), or epigastric pain.3 Chronic abuse tends to result in more systemic sequelae, affecting the bladder, kidneys, and heart. Adverse effects that require emergent care include blood in urine, changes in vision (eg, nystagmus), chest discomfort, labored breathing, agitation, seizures, and/or altered consciousness.6

Treating ketamine abuse

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s symptoms. If the patient presents with “K-bladder” (ie, ketamine bladder syndrome), he/she may need surgical intervention or a cystectomy.4,7 Therapeutic management of K-bladder entails recognizing bladder symptoms that are specific to ketamine use, such as interstitial or ulcerative cystitis and lower urinary tract symptoms.7 Clinicians should monitor patients for increased voiding episodes during the day, voiding urgency, or a general sense of bladder fullness. Patients with K-bladder also may complain of suprapubic pain or blood in the urine.7

Continue to: Consider referring patients to...

Consider referring patients to an individualized, ketamine-specific rehabilitation program that is modeled after other substance-specific rehabilitation programs. It is critical to address withdrawal symptoms (eg, anorexia, fatigue, tremors, chills, tachycardia, nightmares, etc.). Patients undergoing ketamine withdrawal may develop anxiety and depression, with or without suicidal ideation, that might persist during a 4- to 5-day withdrawal period.8

‘Self-medicating’ ketamine users

Clinicians need to be particularly vigilant for situations in which a patient has used ketamine in an attempt to control his/her depressive symptoms. Some researchers have described ketamine as a revolutionary drug for TRD, and it is reasonable to suspect that some patients with depressive symptoms may have consulted Internet sources to learn how to self-medicate using ketamine. Patients who have consumed smaller doses of ketamine recreationally may have developed a tolerance in which the receptors are no longer responsive to the effects at that dose, and therefore might not respond when given ketamine in a clinical setting. Proper history taking and patient education are essential for these users, and clinicians may need to develop a personalized therapeutic plan for ketamine administration. If, on the other hand, a patient has a history of chronic ketamine use (perhaps at high doses), depression may occur secondary to this type of ketamine abuse. For such patients, clinicians should explore alternative treatment modalities, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation.

The N-methyl-

Physicians need to be aware, however, that many patients use illicit ketamine, either for recreational purposes or as self-treatment to control depressive symptoms. To help clinicians identify the signs of ketamine abuse, we discuss the adverse effects of illicit use, and suggest treatment approaches.

Ad

Ketamine can be consumed in various ways; snorting it in a powder form is a preferred route for recreational use.2 The primary disadvantage of oral use is that it increases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting.2

While ketamine is generally safe in a supervised clinical setting, approximately 2.5 million individuals use various illicit forms of ketamine—which is known as Special K and by other names—in recreational settings (eg, dance clubs) where it might be used with other substances.3 Alcohol, in particular, compounds the sedative effects of ketamine and can lead to death by overdose.

At a subanesthetic dose, ketamine can induce dissociative and/or transcendental states that are particularly attractive to those intrigued by mystical experiences, pronounced changes in perception, or euphoria.4 High doses of ketamine—relative to a commonly used recreational dose—can produce a unique “K-hole” state in which a user is unable to control his/her body and could lose consciousness.5 A K-hole state may trigger a cycle of delirium that warrants immediate clinical attention.3

Researchers have postulated that NMDA antagonism may negatively impact memory consolidation.3,6 Even more troubling is the potential for systemic injuries because illicit ketamine use may contribute to ulcerative cystitis, severely disturbed kidney function (eg, hydronephrosis), or epigastric pain.3 Chronic abuse tends to result in more systemic sequelae, affecting the bladder, kidneys, and heart. Adverse effects that require emergent care include blood in urine, changes in vision (eg, nystagmus), chest discomfort, labored breathing, agitation, seizures, and/or altered consciousness.6

Treating ketamine abuse

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s symptoms. If the patient presents with “K-bladder” (ie, ketamine bladder syndrome), he/she may need surgical intervention or a cystectomy.4,7 Therapeutic management of K-bladder entails recognizing bladder symptoms that are specific to ketamine use, such as interstitial or ulcerative cystitis and lower urinary tract symptoms.7 Clinicians should monitor patients for increased voiding episodes during the day, voiding urgency, or a general sense of bladder fullness. Patients with K-bladder also may complain of suprapubic pain or blood in the urine.7

Continue to: Consider referring patients to...

Consider referring patients to an individualized, ketamine-specific rehabilitation program that is modeled after other substance-specific rehabilitation programs. It is critical to address withdrawal symptoms (eg, anorexia, fatigue, tremors, chills, tachycardia, nightmares, etc.). Patients undergoing ketamine withdrawal may develop anxiety and depression, with or without suicidal ideation, that might persist during a 4- to 5-day withdrawal period.8

‘Self-medicating’ ketamine users

Clinicians need to be particularly vigilant for situations in which a patient has used ketamine in an attempt to control his/her depressive symptoms. Some researchers have described ketamine as a revolutionary drug for TRD, and it is reasonable to suspect that some patients with depressive symptoms may have consulted Internet sources to learn how to self-medicate using ketamine. Patients who have consumed smaller doses of ketamine recreationally may have developed a tolerance in which the receptors are no longer responsive to the effects at that dose, and therefore might not respond when given ketamine in a clinical setting. Proper history taking and patient education are essential for these users, and clinicians may need to develop a personalized therapeutic plan for ketamine administration. If, on the other hand, a patient has a history of chronic ketamine use (perhaps at high doses), depression may occur secondary to this type of ketamine abuse. For such patients, clinicians should explore alternative treatment modalities, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation.

1. Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283-290.

2. Davis K. What are the uses of ketamine? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/302663.php. Updated October 12, 2017. Published October 11, 2019.

3. Chaverneff F. Ketamine: mechanisms of action, uses in pain medicine, and side effects. Clinical Pain Advisor. https://www.clinicalpainadvisor.com/home/conference-highlights/painweek-2018/ketamine-mechanisms-of-action-uses-in-pain-medicine-and-side-effects/. Published 2018. Accessed October 11, 2019.

4. Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):865-872.

5. Orhurhu VJ, Claus LE, Cohen SP. Ketamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087. Updated April 11, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019.

6. Pai A, Heining M. Ketamine. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 20071;7(2):59-63.

7. Logan K. Addressing ketamine bladder syndrome. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/medicine-management/addressing-ketamine-bladder-syndrome-19-06-2011/. Published June 19, 2011. Accessed October 11, 2019.

8. Lin PC, Lane HY, Lin CH. Spontaneous remission of ketamine withdrawal-related depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(1):51-52.

1. Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283-290.

2. Davis K. What are the uses of ketamine? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/302663.php. Updated October 12, 2017. Published October 11, 2019.

3. Chaverneff F. Ketamine: mechanisms of action, uses in pain medicine, and side effects. Clinical Pain Advisor. https://www.clinicalpainadvisor.com/home/conference-highlights/painweek-2018/ketamine-mechanisms-of-action-uses-in-pain-medicine-and-side-effects/. Published 2018. Accessed October 11, 2019.

4. Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):865-872.

5. Orhurhu VJ, Claus LE, Cohen SP. Ketamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087. Updated April 11, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019.

6. Pai A, Heining M. Ketamine. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 20071;7(2):59-63.

7. Logan K. Addressing ketamine bladder syndrome. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/medicine-management/addressing-ketamine-bladder-syndrome-19-06-2011/. Published June 19, 2011. Accessed October 11, 2019.

8. Lin PC, Lane HY, Lin CH. Spontaneous remission of ketamine withdrawal-related depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(1):51-52.

Would you recognize this ‘invisible’ encephalopathy?

Mr. Z, an obese adult with a history of portal hypertension and cirrhosis from alcoholism, visits your clinic because he is having difficulty sleeping and concentrating at work. He recently reduced his alcohol use and has improved support from his spouse. He walks into your office with an unremarkable gait before stopping to jot down a note in crisp, neat handwriting. He sits facing you, making good eye contact and exhibiting no involuntary movements. As has been the case at previous visits, Mr. Z is fully oriented to person, place, and time. You can follow one another’s train of thought and collaborate on treatment decisions. You’ve ruled out hepatic encephalopathy. Could you be missing something?

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric condition caused by metabolic changes secondary to liver dysfunction and/or by blood flow bypassing the portal venous system. Signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy range from subtle changes in cognition and affect to coma.Pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in hepatic encephalopathy include inflammation, neurotoxins, oxidative stress, permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier, and impaired brain energy metabolism.1

Patients with poor liver function commonly have psychometrically detectable cognitive and psychomotor deficits that can substantially affect their lives. When such deficits are undetectable by

Approximately 22% to 74% of patients with liver dysfunction develop MHE.2 Prevalence estimates vary widely because of the poor standardization of diagnostic criteria and potential underdiagnosis due to a lack of obvious symptoms.2

How is MHE diagnosed?

The most commonly administered psychometric test to assess for MHE is the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score, a written test that measures motor speed and accuracy, concentration, attention, visual perception, visual-spatial orientation, visual construction, and memory.3,4 Other methods for evaluating MHE, including EEG, MRI, single-photon emission CT, positron emission tomography, and determining a patient’s frequency threshold of perceiving a flickering light, have predictive power, but they do not have a well-defined, standardized role in the diagnosis of MHE.2 Although ammonia levels can correlate with severity of impairment in episodic hepatic encephalopathy, they are not well correlated with the deficits in MHE, and often it is not feasible to properly measure ammonia concentrations in outpatient settings.2

Limited treatment options

Few studies have investigated interventions specifically for MHE. The beststudied treatments are lactulose5 and rifaximin.6 Lactulose reduces the formation of ammonia and the absorption of both ammonia and glutamine in the colonic lumen.5 In addition to improving MHE, lactulose helps prevent the recurrence of episodic overt hepatic encephalopathy.5 The antibiotic rifaximin kills ammonia-producing gut bacteria because it is minimally absorbed in the digestive system. No studies investigating rifaximin have observed antibiotic resistance, even with prolonged use. Rifaximin improves cognitive ability, driving ability, and quality of life in patients with MHE. Adding rifaximin to a treatment regimen that includes lactulose also can reduce the recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy.6 Branched chain amino acids, L-carnitine, L-ornithine aspartate, treating a comorbid zinc deficiency, probiotics, and increasing vegetable protein intake relative to animal protein intake may also have roles in treating MHE.2

1. Hadjihambi A, Arias N, Sheikh M, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy: a critical current review. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(suppl 1):S135-S147.

2. Zhan T, Stremmel W. The diagnosis and treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(10):180-1877.

3. Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, et al. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34(5):768-773.

4. Nabi E, Bajaj J. Useful tests for hepatic encephalopathy in clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(1):362.

5. Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, et al. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):885-891.

6. Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071-1081.

Mr. Z, an obese adult with a history of portal hypertension and cirrhosis from alcoholism, visits your clinic because he is having difficulty sleeping and concentrating at work. He recently reduced his alcohol use and has improved support from his spouse. He walks into your office with an unremarkable gait before stopping to jot down a note in crisp, neat handwriting. He sits facing you, making good eye contact and exhibiting no involuntary movements. As has been the case at previous visits, Mr. Z is fully oriented to person, place, and time. You can follow one another’s train of thought and collaborate on treatment decisions. You’ve ruled out hepatic encephalopathy. Could you be missing something?

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric condition caused by metabolic changes secondary to liver dysfunction and/or by blood flow bypassing the portal venous system. Signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy range from subtle changes in cognition and affect to coma.Pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in hepatic encephalopathy include inflammation, neurotoxins, oxidative stress, permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier, and impaired brain energy metabolism.1

Patients with poor liver function commonly have psychometrically detectable cognitive and psychomotor deficits that can substantially affect their lives. When such deficits are undetectable by

Approximately 22% to 74% of patients with liver dysfunction develop MHE.2 Prevalence estimates vary widely because of the poor standardization of diagnostic criteria and potential underdiagnosis due to a lack of obvious symptoms.2

How is MHE diagnosed?

The most commonly administered psychometric test to assess for MHE is the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score, a written test that measures motor speed and accuracy, concentration, attention, visual perception, visual-spatial orientation, visual construction, and memory.3,4 Other methods for evaluating MHE, including EEG, MRI, single-photon emission CT, positron emission tomography, and determining a patient’s frequency threshold of perceiving a flickering light, have predictive power, but they do not have a well-defined, standardized role in the diagnosis of MHE.2 Although ammonia levels can correlate with severity of impairment in episodic hepatic encephalopathy, they are not well correlated with the deficits in MHE, and often it is not feasible to properly measure ammonia concentrations in outpatient settings.2

Limited treatment options

Few studies have investigated interventions specifically for MHE. The beststudied treatments are lactulose5 and rifaximin.6 Lactulose reduces the formation of ammonia and the absorption of both ammonia and glutamine in the colonic lumen.5 In addition to improving MHE, lactulose helps prevent the recurrence of episodic overt hepatic encephalopathy.5 The antibiotic rifaximin kills ammonia-producing gut bacteria because it is minimally absorbed in the digestive system. No studies investigating rifaximin have observed antibiotic resistance, even with prolonged use. Rifaximin improves cognitive ability, driving ability, and quality of life in patients with MHE. Adding rifaximin to a treatment regimen that includes lactulose also can reduce the recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy.6 Branched chain amino acids, L-carnitine, L-ornithine aspartate, treating a comorbid zinc deficiency, probiotics, and increasing vegetable protein intake relative to animal protein intake may also have roles in treating MHE.2

Mr. Z, an obese adult with a history of portal hypertension and cirrhosis from alcoholism, visits your clinic because he is having difficulty sleeping and concentrating at work. He recently reduced his alcohol use and has improved support from his spouse. He walks into your office with an unremarkable gait before stopping to jot down a note in crisp, neat handwriting. He sits facing you, making good eye contact and exhibiting no involuntary movements. As has been the case at previous visits, Mr. Z is fully oriented to person, place, and time. You can follow one another’s train of thought and collaborate on treatment decisions. You’ve ruled out hepatic encephalopathy. Could you be missing something?

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric condition caused by metabolic changes secondary to liver dysfunction and/or by blood flow bypassing the portal venous system. Signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy range from subtle changes in cognition and affect to coma.Pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in hepatic encephalopathy include inflammation, neurotoxins, oxidative stress, permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier, and impaired brain energy metabolism.1

Patients with poor liver function commonly have psychometrically detectable cognitive and psychomotor deficits that can substantially affect their lives. When such deficits are undetectable by

Approximately 22% to 74% of patients with liver dysfunction develop MHE.2 Prevalence estimates vary widely because of the poor standardization of diagnostic criteria and potential underdiagnosis due to a lack of obvious symptoms.2

How is MHE diagnosed?

The most commonly administered psychometric test to assess for MHE is the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score, a written test that measures motor speed and accuracy, concentration, attention, visual perception, visual-spatial orientation, visual construction, and memory.3,4 Other methods for evaluating MHE, including EEG, MRI, single-photon emission CT, positron emission tomography, and determining a patient’s frequency threshold of perceiving a flickering light, have predictive power, but they do not have a well-defined, standardized role in the diagnosis of MHE.2 Although ammonia levels can correlate with severity of impairment in episodic hepatic encephalopathy, they are not well correlated with the deficits in MHE, and often it is not feasible to properly measure ammonia concentrations in outpatient settings.2

Limited treatment options

Few studies have investigated interventions specifically for MHE. The beststudied treatments are lactulose5 and rifaximin.6 Lactulose reduces the formation of ammonia and the absorption of both ammonia and glutamine in the colonic lumen.5 In addition to improving MHE, lactulose helps prevent the recurrence of episodic overt hepatic encephalopathy.5 The antibiotic rifaximin kills ammonia-producing gut bacteria because it is minimally absorbed in the digestive system. No studies investigating rifaximin have observed antibiotic resistance, even with prolonged use. Rifaximin improves cognitive ability, driving ability, and quality of life in patients with MHE. Adding rifaximin to a treatment regimen that includes lactulose also can reduce the recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy.6 Branched chain amino acids, L-carnitine, L-ornithine aspartate, treating a comorbid zinc deficiency, probiotics, and increasing vegetable protein intake relative to animal protein intake may also have roles in treating MHE.2

1. Hadjihambi A, Arias N, Sheikh M, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy: a critical current review. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(suppl 1):S135-S147.

2. Zhan T, Stremmel W. The diagnosis and treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(10):180-1877.

3. Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, et al. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34(5):768-773.

4. Nabi E, Bajaj J. Useful tests for hepatic encephalopathy in clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(1):362.

5. Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, et al. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):885-891.

6. Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071-1081.

1. Hadjihambi A, Arias N, Sheikh M, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy: a critical current review. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(suppl 1):S135-S147.

2. Zhan T, Stremmel W. The diagnosis and treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(10):180-1877.

3. Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, et al. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34(5):768-773.

4. Nabi E, Bajaj J. Useful tests for hepatic encephalopathy in clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(1):362.

5. Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, et al. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):885-891.

6. Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071-1081.

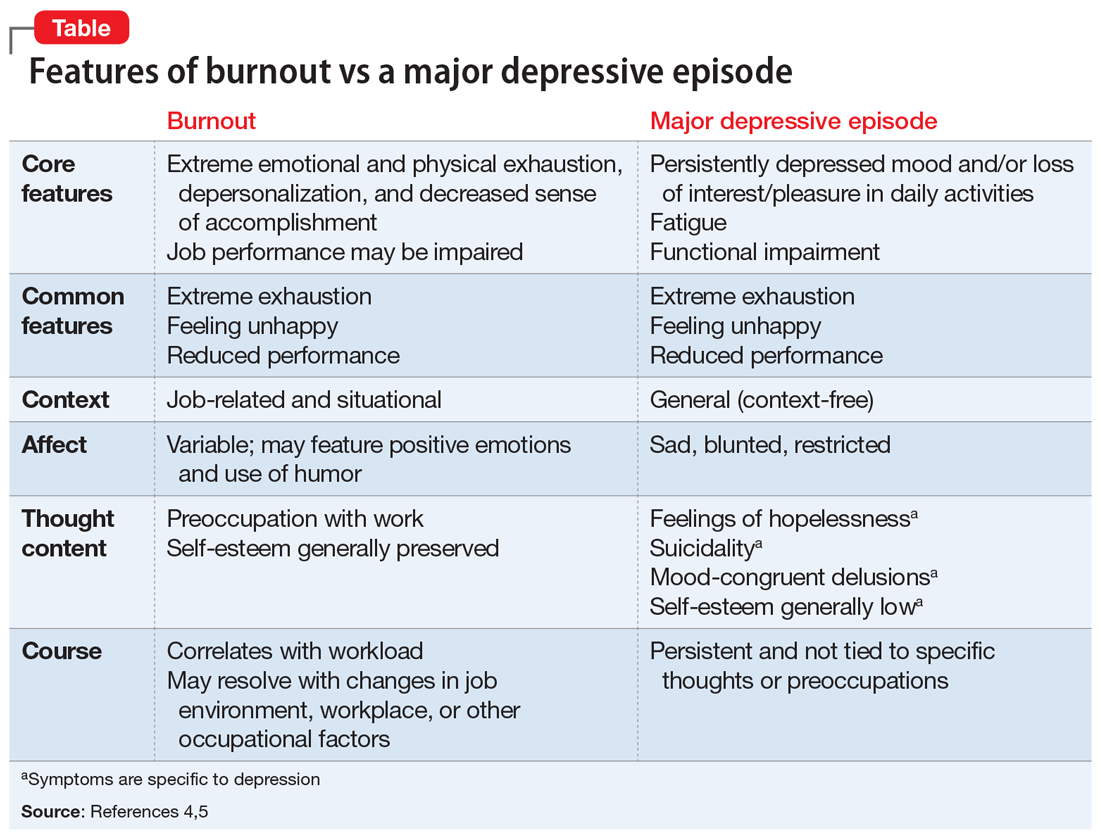

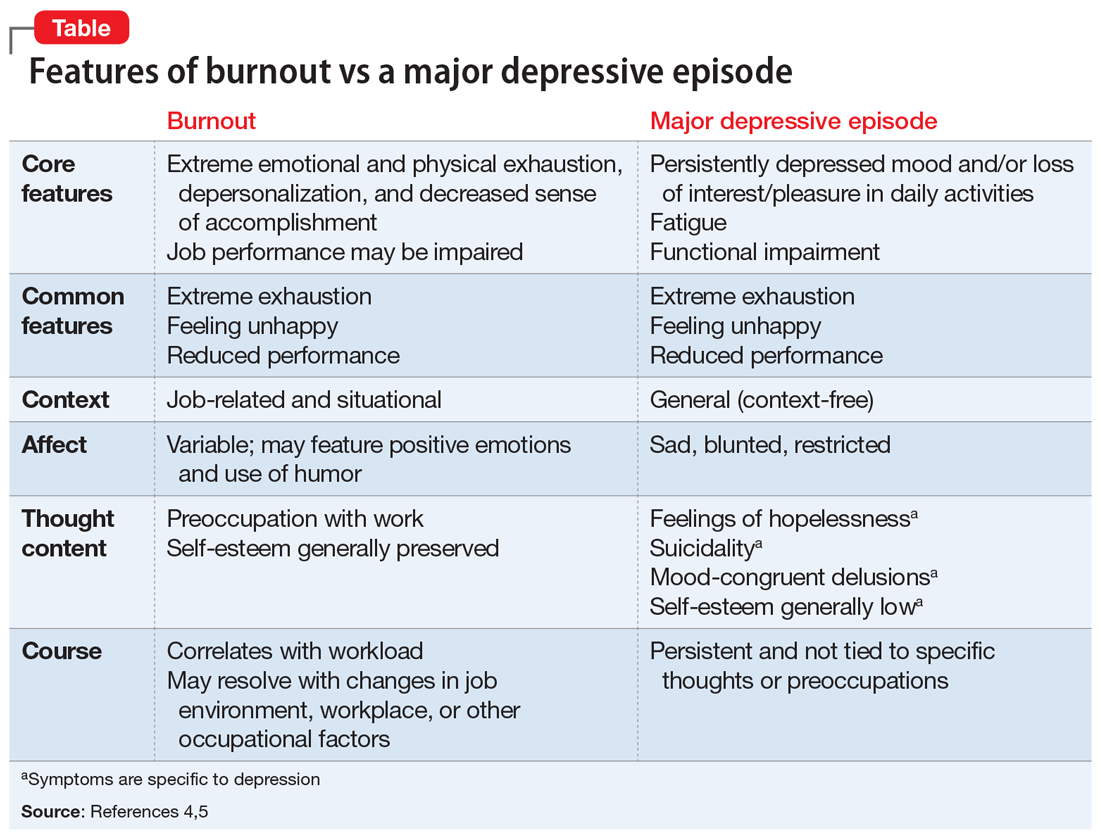

Physician burnout vs depression: Recognize the signs

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

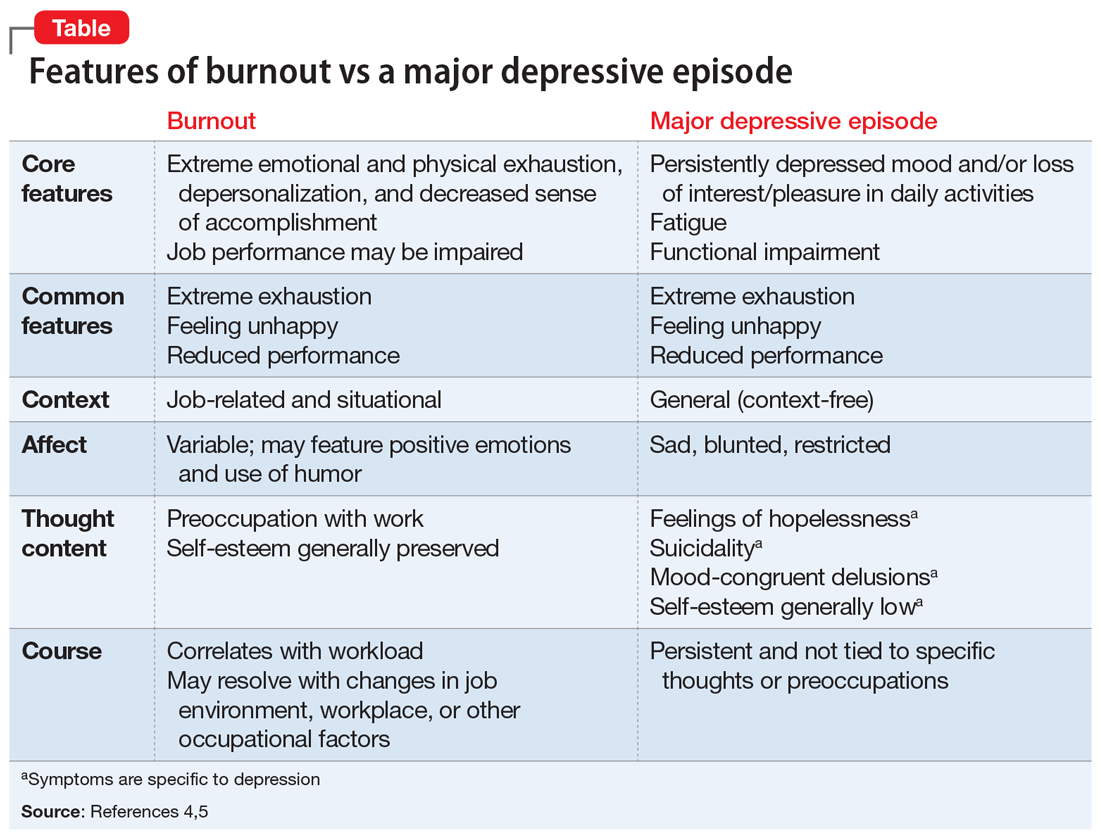

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

DBS vs TMS for treatment-resistant depression: A comparison

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond to pharmacotherapy.1 For patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—typically defined as an inadequate response to at least 1 antidepressant trial of adequate dose and duration—neurostimulation may be an effective treatment option.

Two forms of neurostimulation used to treat TRD are deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In DBS, electrodes are placed within the patient’s cranium and affixed to specific target locations. These electrodes are electrically stimulated at various frequencies. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive treatment in which a magnetic field is produced over a patient’s cranium, stimulating brain tissue via electromagnetic induction.

Media portraya

In this article, I compare DBS and TMS, and offer suggestions for educating patients about the potential adverse effects and therapeutic outcomes of each modality.

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation is FDA-approved for treating Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, dystonia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).3 It has been used off-label for TRD, and some preliminary evidence suggests it is effective for this purpose. A review of 22 studies found that for patients with TRD, the rate of response to DBS (defined as >50% improvement on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score) ranges from 40% to 70%.1 Additional research, including larger, randomized, sham-controlled trials, is needed.

A consensus on the optimal target location for DBS has not yet been reached. Studies have had varying degrees of symptom improvement targeting the subgenual cingulate gyrus, posterior gyrus rectus, nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum, inferior thalamic peduncle, and lateral habenula.1

A worsening of depressive symptoms and increased risk of suicide have been reported in—but are not exclusive to—DBS. Patients treated with DBS may still meet the criteria for treatment resistance.

Continue to: The lack of insurance coverage...

The lack of insurance coverage for DBS for treating depression is a deterrent to its use. Because DBS is not FDA-approved for treating depression, the costs (approximately $65,000) that are not covered by a facility or study will fall on the patient.4 Patients may abandon hope for a positive therapeutic outcome if they must struggle with the financial responsibility for procedures and follow-up.4

Serious potential adverse events of DBS include infections, skin erosions, and postoperative seizure.4 Patients who are treated with DBS should be educated about these adverse effects, and how they may affect outcomes.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is FDA-approved for treating depression, OCD, and migraine. Randomized, sham-controlled trials have found that TMS is effective for TRD.5 Studies have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy, with response rates ranging from 47% to 58%.6

The most commonly used target area for TMS for patients with depression is the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.7 Potential adverse effects are relatively few and benign. The most serious adverse effect of TMS is a risk for seizure, which is reported to occur at a frequency of <0.1%.7

Although it varies by practice and location, the cost for an acute course of TMS (20 to 30 sessions) may range from $6,000 to $12,000.8 Most insurance companies cover TMS treatment for depression.

Continue to: TMS

TMS: A more accessible option

Compared with DBS, TMS is a more affordable and accessible therapy for patients with TRD. Further studies are needed to learn more about the therapeutic potential of DBS for TRD, and to develop methods that help decrease the risk of adverse effects. In addition, insurance coverage needs to be expanded to DBS to avoid having patients be responsible for the full costs of this treatment. Until then, TMS should be a recommended therapy for patients with TRD. If TRD persists in patients treated with TMS, consider electroconvulsive therapy.

1. Morishita T, Fayad SM, Higuchi MA, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review of clinical outcomes. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-484.

2. Lawrence RE, Kaufmann CR, DeSilva RB, et al. Patients’ belief about deep brain stimulation for treatment resistant depression. AJOB Neuroscience, 2018;9(4):210-218.

3. Rossi PJ, Giordano J, Okun MS. The problem of funding off-label deep brain stimulation: bait-and-switch tactics and the need for policy reform. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):9-10.

4. Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):839-849.

5. Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

6. Janicak PG, Sackett V, Kudrna K, et al. Advances in transcranial magnetic stimulation for managing major depressive disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):49-56.

7. Dobek CE, Blumberger DM, Downar J, et al. Risk of seizures in transcranial magnetic stimulation: a clinical review to inform consent process focused on bupropion. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2975-2987.

8. McClintock SM, Reti IM, Carpenter LL, et al; National Network of Depression Centers rTMS Task Group; American Psychiatric Association Council on Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Consensus recommendations for the clinical application of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.16cs10905.

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond to pharmacotherapy.1 For patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—typically defined as an inadequate response to at least 1 antidepressant trial of adequate dose and duration—neurostimulation may be an effective treatment option.

Two forms of neurostimulation used to treat TRD are deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In DBS, electrodes are placed within the patient’s cranium and affixed to specific target locations. These electrodes are electrically stimulated at various frequencies. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive treatment in which a magnetic field is produced over a patient’s cranium, stimulating brain tissue via electromagnetic induction.

Media portraya

In this article, I compare DBS and TMS, and offer suggestions for educating patients about the potential adverse effects and therapeutic outcomes of each modality.

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation is FDA-approved for treating Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, dystonia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).3 It has been used off-label for TRD, and some preliminary evidence suggests it is effective for this purpose. A review of 22 studies found that for patients with TRD, the rate of response to DBS (defined as >50% improvement on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score) ranges from 40% to 70%.1 Additional research, including larger, randomized, sham-controlled trials, is needed.

A consensus on the optimal target location for DBS has not yet been reached. Studies have had varying degrees of symptom improvement targeting the subgenual cingulate gyrus, posterior gyrus rectus, nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum, inferior thalamic peduncle, and lateral habenula.1

A worsening of depressive symptoms and increased risk of suicide have been reported in—but are not exclusive to—DBS. Patients treated with DBS may still meet the criteria for treatment resistance.

Continue to: The lack of insurance coverage...

The lack of insurance coverage for DBS for treating depression is a deterrent to its use. Because DBS is not FDA-approved for treating depression, the costs (approximately $65,000) that are not covered by a facility or study will fall on the patient.4 Patients may abandon hope for a positive therapeutic outcome if they must struggle with the financial responsibility for procedures and follow-up.4

Serious potential adverse events of DBS include infections, skin erosions, and postoperative seizure.4 Patients who are treated with DBS should be educated about these adverse effects, and how they may affect outcomes.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is FDA-approved for treating depression, OCD, and migraine. Randomized, sham-controlled trials have found that TMS is effective for TRD.5 Studies have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy, with response rates ranging from 47% to 58%.6

The most commonly used target area for TMS for patients with depression is the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.7 Potential adverse effects are relatively few and benign. The most serious adverse effect of TMS is a risk for seizure, which is reported to occur at a frequency of <0.1%.7

Although it varies by practice and location, the cost for an acute course of TMS (20 to 30 sessions) may range from $6,000 to $12,000.8 Most insurance companies cover TMS treatment for depression.

Continue to: TMS

TMS: A more accessible option

Compared with DBS, TMS is a more affordable and accessible therapy for patients with TRD. Further studies are needed to learn more about the therapeutic potential of DBS for TRD, and to develop methods that help decrease the risk of adverse effects. In addition, insurance coverage needs to be expanded to DBS to avoid having patients be responsible for the full costs of this treatment. Until then, TMS should be a recommended therapy for patients with TRD. If TRD persists in patients treated with TMS, consider electroconvulsive therapy.

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond to pharmacotherapy.1 For patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—typically defined as an inadequate response to at least 1 antidepressant trial of adequate dose and duration—neurostimulation may be an effective treatment option.

Two forms of neurostimulation used to treat TRD are deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In DBS, electrodes are placed within the patient’s cranium and affixed to specific target locations. These electrodes are electrically stimulated at various frequencies. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive treatment in which a magnetic field is produced over a patient’s cranium, stimulating brain tissue via electromagnetic induction.

Media portraya

In this article, I compare DBS and TMS, and offer suggestions for educating patients about the potential adverse effects and therapeutic outcomes of each modality.

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation is FDA-approved for treating Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, dystonia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).3 It has been used off-label for TRD, and some preliminary evidence suggests it is effective for this purpose. A review of 22 studies found that for patients with TRD, the rate of response to DBS (defined as >50% improvement on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score) ranges from 40% to 70%.1 Additional research, including larger, randomized, sham-controlled trials, is needed.

A consensus on the optimal target location for DBS has not yet been reached. Studies have had varying degrees of symptom improvement targeting the subgenual cingulate gyrus, posterior gyrus rectus, nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum, inferior thalamic peduncle, and lateral habenula.1

A worsening of depressive symptoms and increased risk of suicide have been reported in—but are not exclusive to—DBS. Patients treated with DBS may still meet the criteria for treatment resistance.

Continue to: The lack of insurance coverage...

The lack of insurance coverage for DBS for treating depression is a deterrent to its use. Because DBS is not FDA-approved for treating depression, the costs (approximately $65,000) that are not covered by a facility or study will fall on the patient.4 Patients may abandon hope for a positive therapeutic outcome if they must struggle with the financial responsibility for procedures and follow-up.4

Serious potential adverse events of DBS include infections, skin erosions, and postoperative seizure.4 Patients who are treated with DBS should be educated about these adverse effects, and how they may affect outcomes.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is FDA-approved for treating depression, OCD, and migraine. Randomized, sham-controlled trials have found that TMS is effective for TRD.5 Studies have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy, with response rates ranging from 47% to 58%.6

The most commonly used target area for TMS for patients with depression is the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.7 Potential adverse effects are relatively few and benign. The most serious adverse effect of TMS is a risk for seizure, which is reported to occur at a frequency of <0.1%.7

Although it varies by practice and location, the cost for an acute course of TMS (20 to 30 sessions) may range from $6,000 to $12,000.8 Most insurance companies cover TMS treatment for depression.

Continue to: TMS

TMS: A more accessible option

Compared with DBS, TMS is a more affordable and accessible therapy for patients with TRD. Further studies are needed to learn more about the therapeutic potential of DBS for TRD, and to develop methods that help decrease the risk of adverse effects. In addition, insurance coverage needs to be expanded to DBS to avoid having patients be responsible for the full costs of this treatment. Until then, TMS should be a recommended therapy for patients with TRD. If TRD persists in patients treated with TMS, consider electroconvulsive therapy.

1. Morishita T, Fayad SM, Higuchi MA, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review of clinical outcomes. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-484.

2. Lawrence RE, Kaufmann CR, DeSilva RB, et al. Patients’ belief about deep brain stimulation for treatment resistant depression. AJOB Neuroscience, 2018;9(4):210-218.

3. Rossi PJ, Giordano J, Okun MS. The problem of funding off-label deep brain stimulation: bait-and-switch tactics and the need for policy reform. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):9-10.

4. Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):839-849.

5. Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

6. Janicak PG, Sackett V, Kudrna K, et al. Advances in transcranial magnetic stimulation for managing major depressive disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):49-56.

7. Dobek CE, Blumberger DM, Downar J, et al. Risk of seizures in transcranial magnetic stimulation: a clinical review to inform consent process focused on bupropion. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2975-2987.

8. McClintock SM, Reti IM, Carpenter LL, et al; National Network of Depression Centers rTMS Task Group; American Psychiatric Association Council on Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Consensus recommendations for the clinical application of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.16cs10905.

1. Morishita T, Fayad SM, Higuchi MA, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review of clinical outcomes. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-484.

2. Lawrence RE, Kaufmann CR, DeSilva RB, et al. Patients’ belief about deep brain stimulation for treatment resistant depression. AJOB Neuroscience, 2018;9(4):210-218.

3. Rossi PJ, Giordano J, Okun MS. The problem of funding off-label deep brain stimulation: bait-and-switch tactics and the need for policy reform. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):9-10.

4. Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):839-849.

5. Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

6. Janicak PG, Sackett V, Kudrna K, et al. Advances in transcranial magnetic stimulation for managing major depressive disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):49-56.

7. Dobek CE, Blumberger DM, Downar J, et al. Risk of seizures in transcranial magnetic stimulation: a clinical review to inform consent process focused on bupropion. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2975-2987.