User login

Interacting with colleagues on social media: Tips for avoiding trouble

As clinicians, we increasingly communicate with each other via social media platforms to network, collaborate on research, find professional and personal support, refer patients, or hold academic conversations.1,2 Although it is convenient, this form of online communication directly and indirectly breaks down barriers between our professional and personal lives, which can make it challenging to avoid behavior that could negatively affect one’s professional image.2

Although some medical organizations have offered guidelines on health care professionals’ use of social media,2,3 these are subjective and not evidence-based. Here I offer some suggestions for appropriately interacting with your colleagues (ie, individuals who are not your personal friends) on social media.

Think before you post. Consider the potential professional ramifications of what you are about to post, and don’t post anything that may have adverse consequences on your image or that of psychiatry as a whole.

Don’t post derogatory or defamatory statements about colleagues. Such actions may violate professional codes of conduct. Disagreeing with colleagues on social media is common, but your posts should be respectful, friendly, and reflect positively on the profession.2 Avoid making negative statements—even in jest—about your colleagues’ skills or professional experience, because such communication is not appropriate for public dissemination.2

If you notice colleagues posting unprofessional content that could negatively affect their careers or the public’s trust in psychiatry, tactfully express your concerns to them, and suggest that they take appropriate measures to rectify the situation.2 Be aware of your state’s laws and regulations about mandated reporting if you discover a colleague’s online content violates the scope of clinical practice or ethical standards.1 If the content is in violation of the law or medical board regulations, you may have a legal obligation to report that colleague to law enforcement, the licensing board, and/or his/her employer.1,2

Avoid online snooping into the personal lives of colleagues. Respect their privacy when viewing their posts about personal activities that are not germane to their professional services.1 If you find videos, images, or messages that reveal private, confidential, or sensitive information about a colleague, do not distribute that information without the colleague’s consent.1

Be careful when accepting friend requests. Conflicts could arise if you accept friend requests from some but not all of your colleagues; this could be interpreted as favoritism and potentially create problematic work relationships.2 Be consistent in accepting or rejecting colleagues’ friend requests. Consider using an employment-oriented social media platform to connect with colleagues outside of the workplace.2

1. Reamer FG. Evolving standards of care in the age of cybertechnology. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(2):257-269.

2. Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best practices for surgeons’ social media use: statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):317-327.

3. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499,520.

As clinicians, we increasingly communicate with each other via social media platforms to network, collaborate on research, find professional and personal support, refer patients, or hold academic conversations.1,2 Although it is convenient, this form of online communication directly and indirectly breaks down barriers between our professional and personal lives, which can make it challenging to avoid behavior that could negatively affect one’s professional image.2

Although some medical organizations have offered guidelines on health care professionals’ use of social media,2,3 these are subjective and not evidence-based. Here I offer some suggestions for appropriately interacting with your colleagues (ie, individuals who are not your personal friends) on social media.

Think before you post. Consider the potential professional ramifications of what you are about to post, and don’t post anything that may have adverse consequences on your image or that of psychiatry as a whole.

Don’t post derogatory or defamatory statements about colleagues. Such actions may violate professional codes of conduct. Disagreeing with colleagues on social media is common, but your posts should be respectful, friendly, and reflect positively on the profession.2 Avoid making negative statements—even in jest—about your colleagues’ skills or professional experience, because such communication is not appropriate for public dissemination.2

If you notice colleagues posting unprofessional content that could negatively affect their careers or the public’s trust in psychiatry, tactfully express your concerns to them, and suggest that they take appropriate measures to rectify the situation.2 Be aware of your state’s laws and regulations about mandated reporting if you discover a colleague’s online content violates the scope of clinical practice or ethical standards.1 If the content is in violation of the law or medical board regulations, you may have a legal obligation to report that colleague to law enforcement, the licensing board, and/or his/her employer.1,2

Avoid online snooping into the personal lives of colleagues. Respect their privacy when viewing their posts about personal activities that are not germane to their professional services.1 If you find videos, images, or messages that reveal private, confidential, or sensitive information about a colleague, do not distribute that information without the colleague’s consent.1

Be careful when accepting friend requests. Conflicts could arise if you accept friend requests from some but not all of your colleagues; this could be interpreted as favoritism and potentially create problematic work relationships.2 Be consistent in accepting or rejecting colleagues’ friend requests. Consider using an employment-oriented social media platform to connect with colleagues outside of the workplace.2

As clinicians, we increasingly communicate with each other via social media platforms to network, collaborate on research, find professional and personal support, refer patients, or hold academic conversations.1,2 Although it is convenient, this form of online communication directly and indirectly breaks down barriers between our professional and personal lives, which can make it challenging to avoid behavior that could negatively affect one’s professional image.2

Although some medical organizations have offered guidelines on health care professionals’ use of social media,2,3 these are subjective and not evidence-based. Here I offer some suggestions for appropriately interacting with your colleagues (ie, individuals who are not your personal friends) on social media.

Think before you post. Consider the potential professional ramifications of what you are about to post, and don’t post anything that may have adverse consequences on your image or that of psychiatry as a whole.

Don’t post derogatory or defamatory statements about colleagues. Such actions may violate professional codes of conduct. Disagreeing with colleagues on social media is common, but your posts should be respectful, friendly, and reflect positively on the profession.2 Avoid making negative statements—even in jest—about your colleagues’ skills or professional experience, because such communication is not appropriate for public dissemination.2

If you notice colleagues posting unprofessional content that could negatively affect their careers or the public’s trust in psychiatry, tactfully express your concerns to them, and suggest that they take appropriate measures to rectify the situation.2 Be aware of your state’s laws and regulations about mandated reporting if you discover a colleague’s online content violates the scope of clinical practice or ethical standards.1 If the content is in violation of the law or medical board regulations, you may have a legal obligation to report that colleague to law enforcement, the licensing board, and/or his/her employer.1,2

Avoid online snooping into the personal lives of colleagues. Respect their privacy when viewing their posts about personal activities that are not germane to their professional services.1 If you find videos, images, or messages that reveal private, confidential, or sensitive information about a colleague, do not distribute that information without the colleague’s consent.1

Be careful when accepting friend requests. Conflicts could arise if you accept friend requests from some but not all of your colleagues; this could be interpreted as favoritism and potentially create problematic work relationships.2 Be consistent in accepting or rejecting colleagues’ friend requests. Consider using an employment-oriented social media platform to connect with colleagues outside of the workplace.2

1. Reamer FG. Evolving standards of care in the age of cybertechnology. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(2):257-269.

2. Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best practices for surgeons’ social media use: statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):317-327.

3. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499,520.

1. Reamer FG. Evolving standards of care in the age of cybertechnology. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(2):257-269.

2. Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best practices for surgeons’ social media use: statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):317-327.

3. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499,520.

MAPS.EDU, GAS POPS, and AEIOU: Acronyms to guide your assessments

Mnemonics and acronyms are part of our daily lives, helping us to memorize and retain clinical information. They play an invaluable role in medical school because they can help students recall vast amounts of information in a moment’s notice, such as psychiatric conditions to consider during a “review of systems.”

Most medical students are trained to conduct a review of systems as a standard approach when a thorough medical history is indicated. Clinicians need to assess all patients for an extremely broad range of syndromes. Because of the extensive comorbidity of many psychiatric disorders, it is important to review the most common conditions before establishing a diagnosis and formulating a treatment plan.1

For example, a patient presenting with a chief complaint consistent with a depressive disorder may have unipolar depression, bipolar depression, or substance-induced depression (after general medical comorbidity has been excluded). In this scenario, it would be equally important to identify co-occurring conditions, such as an anxiety disorder or psychotic symptoms, because these can have a major impact on treatment and prognosis.

In our work as clinical educators, we have noticed that many students struggle with a review of psychiatric systems during their evaluation of a new patient. Acronyms could serve as a map to guide them during assessments. While these may be most valuable to medical students, they are also helpful for clinicians on the frontline of medical practice (primary care, family practice, OB-GYN) as well as for early-career psychiatrists.

MAPS.EDU

The acronym MAPS.EDU covers several common psychiatric conditions seen in routine practice: Mood disorders, Anxiety disorders, Personality disorders, Schizophrenia and related disorders, Eating disorders, Developmental disorders (eg, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and substance Use disorders. While not comprehensive, MAPS.EDU can be a quick method to help psychiatrists remember these common conditions.

GAS POPS

Anxiety is a core symptom of several psychiatric disorders. The mnemonic GAS POPS can help clinicians recall disorders to consider when screening patients who report anxiety: Generalized anxiety disorder, Agoraphobia, Social anxiety disorder, Panic disorder, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and Specific phobias.

AEIOU for PTSD

The diagnostic criteria of PTSD can be memorized by using the acronym AEIOU: Avoidance (of triggers), Exposure (to trauma), Intrusions (reliving phenomena), Outbursts (or other manifestations of hyperarousal), and Unhappiness (negative alterations in mood and cognition).

1. Rush J, Zimmerman M, Wisniewski S, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: demographic and clinical features. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(1):43-55.

Mnemonics and acronyms are part of our daily lives, helping us to memorize and retain clinical information. They play an invaluable role in medical school because they can help students recall vast amounts of information in a moment’s notice, such as psychiatric conditions to consider during a “review of systems.”

Most medical students are trained to conduct a review of systems as a standard approach when a thorough medical history is indicated. Clinicians need to assess all patients for an extremely broad range of syndromes. Because of the extensive comorbidity of many psychiatric disorders, it is important to review the most common conditions before establishing a diagnosis and formulating a treatment plan.1

For example, a patient presenting with a chief complaint consistent with a depressive disorder may have unipolar depression, bipolar depression, or substance-induced depression (after general medical comorbidity has been excluded). In this scenario, it would be equally important to identify co-occurring conditions, such as an anxiety disorder or psychotic symptoms, because these can have a major impact on treatment and prognosis.

In our work as clinical educators, we have noticed that many students struggle with a review of psychiatric systems during their evaluation of a new patient. Acronyms could serve as a map to guide them during assessments. While these may be most valuable to medical students, they are also helpful for clinicians on the frontline of medical practice (primary care, family practice, OB-GYN) as well as for early-career psychiatrists.

MAPS.EDU

The acronym MAPS.EDU covers several common psychiatric conditions seen in routine practice: Mood disorders, Anxiety disorders, Personality disorders, Schizophrenia and related disorders, Eating disorders, Developmental disorders (eg, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and substance Use disorders. While not comprehensive, MAPS.EDU can be a quick method to help psychiatrists remember these common conditions.

GAS POPS

Anxiety is a core symptom of several psychiatric disorders. The mnemonic GAS POPS can help clinicians recall disorders to consider when screening patients who report anxiety: Generalized anxiety disorder, Agoraphobia, Social anxiety disorder, Panic disorder, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and Specific phobias.

AEIOU for PTSD

The diagnostic criteria of PTSD can be memorized by using the acronym AEIOU: Avoidance (of triggers), Exposure (to trauma), Intrusions (reliving phenomena), Outbursts (or other manifestations of hyperarousal), and Unhappiness (negative alterations in mood and cognition).

Mnemonics and acronyms are part of our daily lives, helping us to memorize and retain clinical information. They play an invaluable role in medical school because they can help students recall vast amounts of information in a moment’s notice, such as psychiatric conditions to consider during a “review of systems.”

Most medical students are trained to conduct a review of systems as a standard approach when a thorough medical history is indicated. Clinicians need to assess all patients for an extremely broad range of syndromes. Because of the extensive comorbidity of many psychiatric disorders, it is important to review the most common conditions before establishing a diagnosis and formulating a treatment plan.1

For example, a patient presenting with a chief complaint consistent with a depressive disorder may have unipolar depression, bipolar depression, or substance-induced depression (after general medical comorbidity has been excluded). In this scenario, it would be equally important to identify co-occurring conditions, such as an anxiety disorder or psychotic symptoms, because these can have a major impact on treatment and prognosis.

In our work as clinical educators, we have noticed that many students struggle with a review of psychiatric systems during their evaluation of a new patient. Acronyms could serve as a map to guide them during assessments. While these may be most valuable to medical students, they are also helpful for clinicians on the frontline of medical practice (primary care, family practice, OB-GYN) as well as for early-career psychiatrists.

MAPS.EDU

The acronym MAPS.EDU covers several common psychiatric conditions seen in routine practice: Mood disorders, Anxiety disorders, Personality disorders, Schizophrenia and related disorders, Eating disorders, Developmental disorders (eg, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and substance Use disorders. While not comprehensive, MAPS.EDU can be a quick method to help psychiatrists remember these common conditions.

GAS POPS

Anxiety is a core symptom of several psychiatric disorders. The mnemonic GAS POPS can help clinicians recall disorders to consider when screening patients who report anxiety: Generalized anxiety disorder, Agoraphobia, Social anxiety disorder, Panic disorder, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and Specific phobias.

AEIOU for PTSD

The diagnostic criteria of PTSD can be memorized by using the acronym AEIOU: Avoidance (of triggers), Exposure (to trauma), Intrusions (reliving phenomena), Outbursts (or other manifestations of hyperarousal), and Unhappiness (negative alterations in mood and cognition).

1. Rush J, Zimmerman M, Wisniewski S, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: demographic and clinical features. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(1):43-55.

1. Rush J, Zimmerman M, Wisniewski S, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: demographic and clinical features. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(1):43-55.

Called to court? Tips for testifying

As a psychiatrist, you could be called to court to testify as a fact witness in a hearing or trial. Your role as a fact witness would differ from that of an expert witness in that you would likely testify about the information that you have gathered through direct observation of patients or others. Fact witnesses are generally not asked to give expert opinions regarding forensic issues, and treating psychiatrists should not do so about their patients. As a fact witness, depending on the form of litigation, you might be in one of the following 4 roles1:

- Observer. As the term implies, you have observed an event. For example, you are asked to testify about a fight that you witnessed between another clinician’s patient and a nurse while you were making your rounds on an inpatient unit.

- Non-defendant treater. You are the treating psychiatrist for a patient who is involved in litigation to recover damages for injuries sustained from a third party. For example, you are asked to testify about your patient’s premorbid functioning before a claimed injury that spurred the lawsuit.

- Plaintiff. You are suing someone else and may be claiming your own damages. For example, in your attempt to claim damages as a plaintiff, you use your clinical knowledge to testify about your own mental health symptoms and the adverse impact these have had on you.

- Defendant treater. You are being sued by one of your patients. For example, a patient brings a malpractice case against you for allegations of not meeting the standard of care. You testify about your direct observations of the patient, the diagnoses you provided, and your rationale for the implemented treatment plan.

Preparing yourself as a fact witness

For many psychiatrists, testifying can be an intimidating process. Although there are similarities between testifying in a courtroom and giving a deposition, there are also significant differences. For guidelines on providing depositions, see Knoll and Resnick’s “Deposition dos and don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions” (

Don’t panic. Although your first reaction may be to panic upon receiving a subpoena or court order, you should “keep your cool” and remember that the observations you made or treatment provided have already taken place.1 Your role as a fact witness is to inform the judge and jury about what you saw and did.1

Continue to: Refresh your memory and practice

Refresh your memory and practice. Gather all required information (eg, medical records, your notes, etc.) and review it before testifying. This will help you to recall the facts more accurately when you are asked a question. Consider practicing your testimony with the attorney who requested you to get feedback on how you present yourself.1 However, do not try to memorize what you are going to say because this could make your testimony sound rehearsed and unconvincing.

Plan ahead, and have a pretrial conference. Because court proceedings are unpredictable, you should clear your schedule to allow enough time to appear in court. Before your court appearance, meet with the attorney who requested you to discuss any new facts or issues as well as learn what the attorney aims to accomplish with your testimony.1

Speak clearly in your own words, and avoid jargon. Courtroom officials are unlikely to understand psychiatric jargon. Therefore, you should explain psychiatric terms in language that laypeople would comprehend. Because the court stenographer will require you to use actual words for the court transcripts, you should answer clearly and verbally or respond with a definitive “yes” or “no” (and not by nodding or shaking your head).

Testimony is also not a time for guessing. If you don’t know the answer, you should say “I don’t know.”

1. Gutheil TG. The psychiatrist in court: a survival guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1998.

2. Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

As a psychiatrist, you could be called to court to testify as a fact witness in a hearing or trial. Your role as a fact witness would differ from that of an expert witness in that you would likely testify about the information that you have gathered through direct observation of patients or others. Fact witnesses are generally not asked to give expert opinions regarding forensic issues, and treating psychiatrists should not do so about their patients. As a fact witness, depending on the form of litigation, you might be in one of the following 4 roles1:

- Observer. As the term implies, you have observed an event. For example, you are asked to testify about a fight that you witnessed between another clinician’s patient and a nurse while you were making your rounds on an inpatient unit.

- Non-defendant treater. You are the treating psychiatrist for a patient who is involved in litigation to recover damages for injuries sustained from a third party. For example, you are asked to testify about your patient’s premorbid functioning before a claimed injury that spurred the lawsuit.

- Plaintiff. You are suing someone else and may be claiming your own damages. For example, in your attempt to claim damages as a plaintiff, you use your clinical knowledge to testify about your own mental health symptoms and the adverse impact these have had on you.

- Defendant treater. You are being sued by one of your patients. For example, a patient brings a malpractice case against you for allegations of not meeting the standard of care. You testify about your direct observations of the patient, the diagnoses you provided, and your rationale for the implemented treatment plan.

Preparing yourself as a fact witness

For many psychiatrists, testifying can be an intimidating process. Although there are similarities between testifying in a courtroom and giving a deposition, there are also significant differences. For guidelines on providing depositions, see Knoll and Resnick’s “Deposition dos and don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions” (

Don’t panic. Although your first reaction may be to panic upon receiving a subpoena or court order, you should “keep your cool” and remember that the observations you made or treatment provided have already taken place.1 Your role as a fact witness is to inform the judge and jury about what you saw and did.1

Continue to: Refresh your memory and practice

Refresh your memory and practice. Gather all required information (eg, medical records, your notes, etc.) and review it before testifying. This will help you to recall the facts more accurately when you are asked a question. Consider practicing your testimony with the attorney who requested you to get feedback on how you present yourself.1 However, do not try to memorize what you are going to say because this could make your testimony sound rehearsed and unconvincing.

Plan ahead, and have a pretrial conference. Because court proceedings are unpredictable, you should clear your schedule to allow enough time to appear in court. Before your court appearance, meet with the attorney who requested you to discuss any new facts or issues as well as learn what the attorney aims to accomplish with your testimony.1

Speak clearly in your own words, and avoid jargon. Courtroom officials are unlikely to understand psychiatric jargon. Therefore, you should explain psychiatric terms in language that laypeople would comprehend. Because the court stenographer will require you to use actual words for the court transcripts, you should answer clearly and verbally or respond with a definitive “yes” or “no” (and not by nodding or shaking your head).

Testimony is also not a time for guessing. If you don’t know the answer, you should say “I don’t know.”

As a psychiatrist, you could be called to court to testify as a fact witness in a hearing or trial. Your role as a fact witness would differ from that of an expert witness in that you would likely testify about the information that you have gathered through direct observation of patients or others. Fact witnesses are generally not asked to give expert opinions regarding forensic issues, and treating psychiatrists should not do so about their patients. As a fact witness, depending on the form of litigation, you might be in one of the following 4 roles1:

- Observer. As the term implies, you have observed an event. For example, you are asked to testify about a fight that you witnessed between another clinician’s patient and a nurse while you were making your rounds on an inpatient unit.

- Non-defendant treater. You are the treating psychiatrist for a patient who is involved in litigation to recover damages for injuries sustained from a third party. For example, you are asked to testify about your patient’s premorbid functioning before a claimed injury that spurred the lawsuit.

- Plaintiff. You are suing someone else and may be claiming your own damages. For example, in your attempt to claim damages as a plaintiff, you use your clinical knowledge to testify about your own mental health symptoms and the adverse impact these have had on you.

- Defendant treater. You are being sued by one of your patients. For example, a patient brings a malpractice case against you for allegations of not meeting the standard of care. You testify about your direct observations of the patient, the diagnoses you provided, and your rationale for the implemented treatment plan.

Preparing yourself as a fact witness

For many psychiatrists, testifying can be an intimidating process. Although there are similarities between testifying in a courtroom and giving a deposition, there are also significant differences. For guidelines on providing depositions, see Knoll and Resnick’s “Deposition dos and don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions” (

Don’t panic. Although your first reaction may be to panic upon receiving a subpoena or court order, you should “keep your cool” and remember that the observations you made or treatment provided have already taken place.1 Your role as a fact witness is to inform the judge and jury about what you saw and did.1

Continue to: Refresh your memory and practice

Refresh your memory and practice. Gather all required information (eg, medical records, your notes, etc.) and review it before testifying. This will help you to recall the facts more accurately when you are asked a question. Consider practicing your testimony with the attorney who requested you to get feedback on how you present yourself.1 However, do not try to memorize what you are going to say because this could make your testimony sound rehearsed and unconvincing.

Plan ahead, and have a pretrial conference. Because court proceedings are unpredictable, you should clear your schedule to allow enough time to appear in court. Before your court appearance, meet with the attorney who requested you to discuss any new facts or issues as well as learn what the attorney aims to accomplish with your testimony.1

Speak clearly in your own words, and avoid jargon. Courtroom officials are unlikely to understand psychiatric jargon. Therefore, you should explain psychiatric terms in language that laypeople would comprehend. Because the court stenographer will require you to use actual words for the court transcripts, you should answer clearly and verbally or respond with a definitive “yes” or “no” (and not by nodding or shaking your head).

Testimony is also not a time for guessing. If you don’t know the answer, you should say “I don’t know.”

1. Gutheil TG. The psychiatrist in court: a survival guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1998.

2. Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

1. Gutheil TG. The psychiatrist in court: a survival guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1998.

2. Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

The evolution of manic and hypomanic symptoms

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

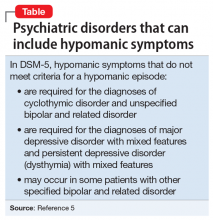

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

Lofexidine: An option for treating opioid withdrawal

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and deaths by opioid overdose are a major public health concern, especially with the advent of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.1 Enrolling patients with OUD into substance abuse treatment programs can be a difficult hurdle to cross because patients do not want to experience withdrawal. The fear of withdrawal leads many individuals to refuse appropriate interventions. For these patients, consider the alpha-2 agonist lofexidine, which was FDA-approved in 2018 to help diminish the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal.1-3 Use of lofexidine might encourage more patients with OUD to accept substance abuse treatment.1,4,5

How to prescribe lofexidine

For decades, clinicians in Britain have prescribed lofexidine to attenuate opioid withdrawal.1An analog of clonidine, lofexidine is reportedly less likely than clonidine to induce hypotension.1,4 While this agent does not diminish drug toxicity, it can provide symptomatic relief for patients undergoing opioid withdrawal, and is efficacious as a supplement to and/or replacement for methadone, buprenorphine, clonidine, or other symptomatic pharmacotherapies.1,4,5

Lofexidine is available in 0.18-mg tablets. For patients experiencing overt symptoms of opioid withdrawal, initially prescribe 3 0.18-mg tablets, 4 times a day.3 The recommended maximum dosage is 2.88 mg/d, and each dose generally should not exceed 0.72 mg/d. Lofexidine may be continued for up to 14 days, with dosing guided by symptoms. Initiate a taper once the patient no longer experiences withdrawal symptoms.3

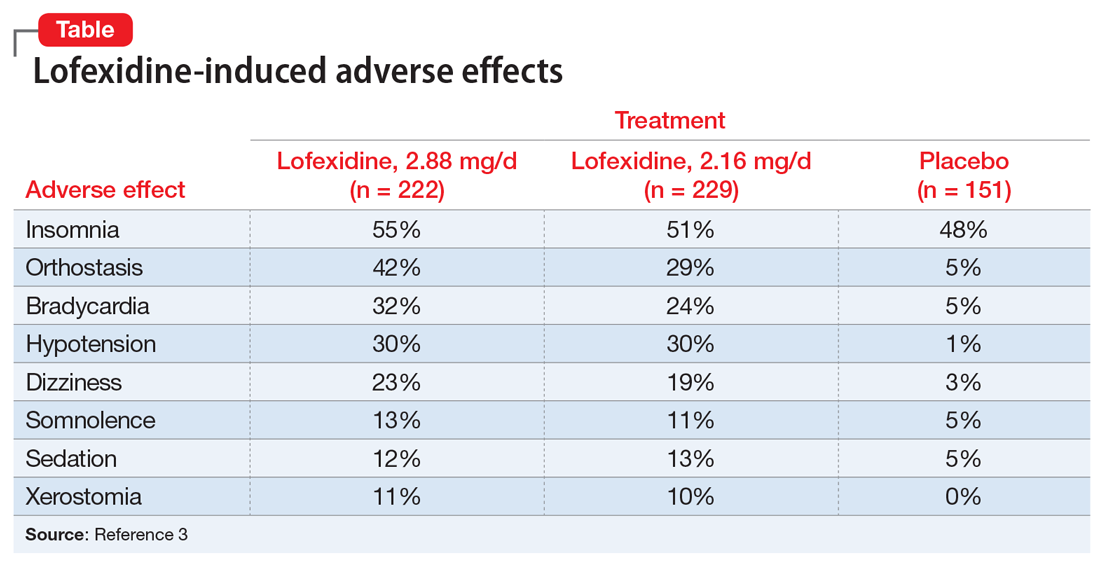

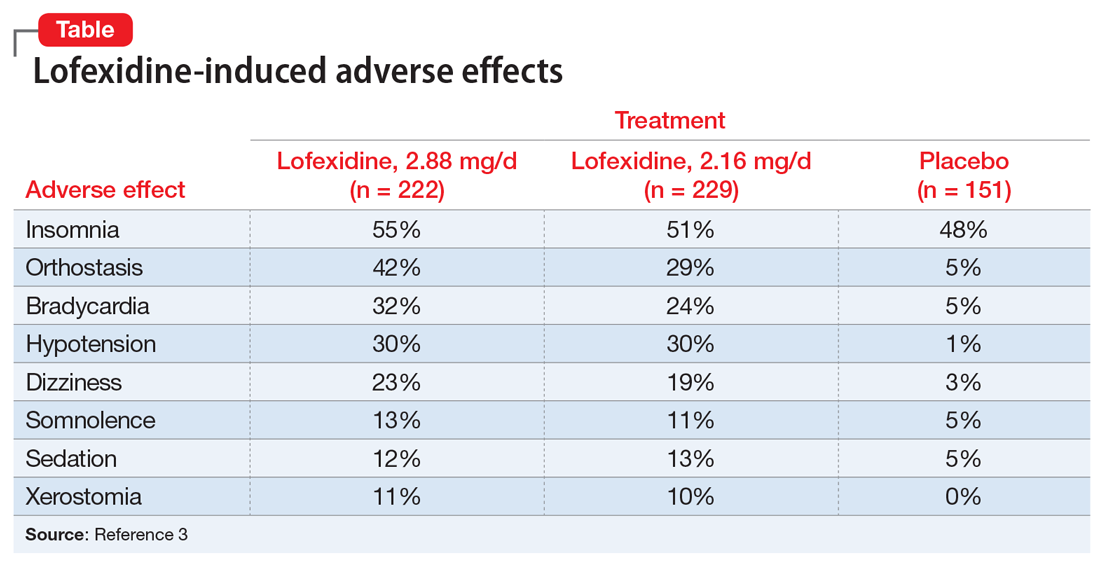

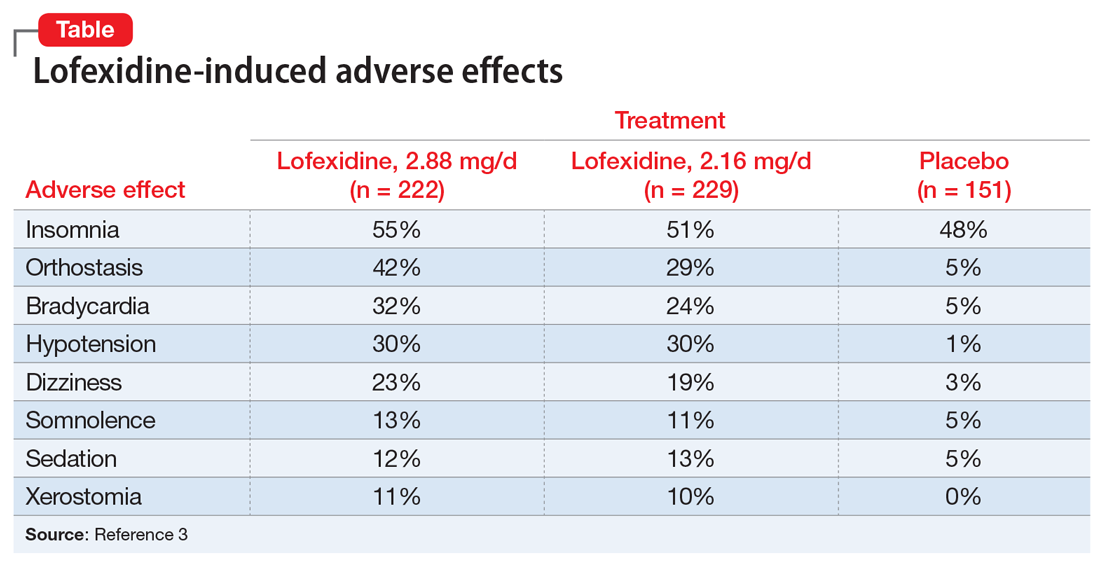

Adverse effects. Lofexidine’s efficacy and safety were evaluated in 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that included 935 participants dependent on short-acting opioids who were experiencing abrupt opioid withdrawal and received lofexidine, 2.16 or 2.88 mg/d, or placebo.3 The most common adverse effects of lofexidine were insomnia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension, dizziness, somnolence, sedation, and dry mouth.3 In the 3 trials, these effects were reported by ≥10% of patients receiving lofexidine, and occurred more frequently compared with placebo (Table3).

Take precautions when prescribing lofexidine because it can cause QT prolongation and CNS depression, especially when co-administered with sedative agents.3 It also can result in rebound hypertension once discontinued. This may be minimized by gradually reducing the dosage.3

A pathway to OUD treatment

Lofexidine can help relieve symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as stomach cramps, muscle spasms or twitching, feeling cold, muscular tension, and aches and pains.1-5 This new option might help clinicians encourage more patients with OUD to fully engage in substance abuse treatment.

1. Rehman SU, Maqsood MH, Bajwa H, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of lofexidine hydrochloride in treating opioid withdrawal symptoms: a review of literature. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4827. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4827.

2. FDA approves the first non-opioid treatment for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in adults. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607884.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed December 13, 2019.

3. Lucemyra [package insert]. Louisville, KY: US WorldMeds, LLC; 2018.

4. Carnwath T, Hardman J. Randomized double-blind comparison of lofexidine and clonidine in the out-patient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(3):251-254.

5. Gonzalez G, Oliveto A, Kosten TR. Combating opiate dependence: a comparison among the available pharmacological options. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(4):713-725.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and deaths by opioid overdose are a major public health concern, especially with the advent of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.1 Enrolling patients with OUD into substance abuse treatment programs can be a difficult hurdle to cross because patients do not want to experience withdrawal. The fear of withdrawal leads many individuals to refuse appropriate interventions. For these patients, consider the alpha-2 agonist lofexidine, which was FDA-approved in 2018 to help diminish the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal.1-3 Use of lofexidine might encourage more patients with OUD to accept substance abuse treatment.1,4,5

How to prescribe lofexidine

For decades, clinicians in Britain have prescribed lofexidine to attenuate opioid withdrawal.1An analog of clonidine, lofexidine is reportedly less likely than clonidine to induce hypotension.1,4 While this agent does not diminish drug toxicity, it can provide symptomatic relief for patients undergoing opioid withdrawal, and is efficacious as a supplement to and/or replacement for methadone, buprenorphine, clonidine, or other symptomatic pharmacotherapies.1,4,5

Lofexidine is available in 0.18-mg tablets. For patients experiencing overt symptoms of opioid withdrawal, initially prescribe 3 0.18-mg tablets, 4 times a day.3 The recommended maximum dosage is 2.88 mg/d, and each dose generally should not exceed 0.72 mg/d. Lofexidine may be continued for up to 14 days, with dosing guided by symptoms. Initiate a taper once the patient no longer experiences withdrawal symptoms.3

Adverse effects. Lofexidine’s efficacy and safety were evaluated in 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that included 935 participants dependent on short-acting opioids who were experiencing abrupt opioid withdrawal and received lofexidine, 2.16 or 2.88 mg/d, or placebo.3 The most common adverse effects of lofexidine were insomnia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension, dizziness, somnolence, sedation, and dry mouth.3 In the 3 trials, these effects were reported by ≥10% of patients receiving lofexidine, and occurred more frequently compared with placebo (Table3).

Take precautions when prescribing lofexidine because it can cause QT prolongation and CNS depression, especially when co-administered with sedative agents.3 It also can result in rebound hypertension once discontinued. This may be minimized by gradually reducing the dosage.3

A pathway to OUD treatment

Lofexidine can help relieve symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as stomach cramps, muscle spasms or twitching, feeling cold, muscular tension, and aches and pains.1-5 This new option might help clinicians encourage more patients with OUD to fully engage in substance abuse treatment.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and deaths by opioid overdose are a major public health concern, especially with the advent of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.1 Enrolling patients with OUD into substance abuse treatment programs can be a difficult hurdle to cross because patients do not want to experience withdrawal. The fear of withdrawal leads many individuals to refuse appropriate interventions. For these patients, consider the alpha-2 agonist lofexidine, which was FDA-approved in 2018 to help diminish the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal.1-3 Use of lofexidine might encourage more patients with OUD to accept substance abuse treatment.1,4,5

How to prescribe lofexidine

For decades, clinicians in Britain have prescribed lofexidine to attenuate opioid withdrawal.1An analog of clonidine, lofexidine is reportedly less likely than clonidine to induce hypotension.1,4 While this agent does not diminish drug toxicity, it can provide symptomatic relief for patients undergoing opioid withdrawal, and is efficacious as a supplement to and/or replacement for methadone, buprenorphine, clonidine, or other symptomatic pharmacotherapies.1,4,5

Lofexidine is available in 0.18-mg tablets. For patients experiencing overt symptoms of opioid withdrawal, initially prescribe 3 0.18-mg tablets, 4 times a day.3 The recommended maximum dosage is 2.88 mg/d, and each dose generally should not exceed 0.72 mg/d. Lofexidine may be continued for up to 14 days, with dosing guided by symptoms. Initiate a taper once the patient no longer experiences withdrawal symptoms.3

Adverse effects. Lofexidine’s efficacy and safety were evaluated in 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that included 935 participants dependent on short-acting opioids who were experiencing abrupt opioid withdrawal and received lofexidine, 2.16 or 2.88 mg/d, or placebo.3 The most common adverse effects of lofexidine were insomnia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension, dizziness, somnolence, sedation, and dry mouth.3 In the 3 trials, these effects were reported by ≥10% of patients receiving lofexidine, and occurred more frequently compared with placebo (Table3).

Take precautions when prescribing lofexidine because it can cause QT prolongation and CNS depression, especially when co-administered with sedative agents.3 It also can result in rebound hypertension once discontinued. This may be minimized by gradually reducing the dosage.3

A pathway to OUD treatment

Lofexidine can help relieve symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as stomach cramps, muscle spasms or twitching, feeling cold, muscular tension, and aches and pains.1-5 This new option might help clinicians encourage more patients with OUD to fully engage in substance abuse treatment.

1. Rehman SU, Maqsood MH, Bajwa H, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of lofexidine hydrochloride in treating opioid withdrawal symptoms: a review of literature. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4827. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4827.

2. FDA approves the first non-opioid treatment for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in adults. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607884.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed December 13, 2019.

3. Lucemyra [package insert]. Louisville, KY: US WorldMeds, LLC; 2018.

4. Carnwath T, Hardman J. Randomized double-blind comparison of lofexidine and clonidine in the out-patient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(3):251-254.

5. Gonzalez G, Oliveto A, Kosten TR. Combating opiate dependence: a comparison among the available pharmacological options. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(4):713-725.

1. Rehman SU, Maqsood MH, Bajwa H, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of lofexidine hydrochloride in treating opioid withdrawal symptoms: a review of literature. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4827. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4827.

2. FDA approves the first non-opioid treatment for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in adults. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607884.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed December 13, 2019.

3. Lucemyra [package insert]. Louisville, KY: US WorldMeds, LLC; 2018.

4. Carnwath T, Hardman J. Randomized double-blind comparison of lofexidine and clonidine in the out-patient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(3):251-254.

5. Gonzalez G, Oliveto A, Kosten TR. Combating opiate dependence: a comparison among the available pharmacological options. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(4):713-725.

In-flight psychiatric emergencies: What you should know

Although they are rare, in-flight psychiatric emergencies occur because of large numbers of passengers, nonstop flights over longer distances, delayed flights, cramped cabins, and/or alcohol consumption.1,2 Psychiatric symptoms and substance intoxication/withdrawal each represent up to

When a passenger requires medical or psychiatric treatment, the flight crew often requests aid from any trained medical professionals who are on board to augment their capabilities and resources (eg, the flight crew’s training, ground-based medical support).1 In the United States, off-duty medical professionals are not legally required to assist during an in-flight medical emergency.1 The Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998 protects passengers who provide medical assistance from liability, except in cases of gross negligence or willful misconduct.1,3 Flights outside of the United States are governed by a complex combination of public and private international laws.1 Here I suggest how to initiate care during in-flight psychiatric emergencies, and offer therapeutic options to employ for a passenger who is exhibiting psychiatric symptoms.

What to do first

Before volunteering to assist in a mental health emergency, consider your capabilities and limitations. Do not volunteer if you are under the influence of alcohol, illicit substances, or any medications (prescription or over-the-counter) that could affect your judgment.

Inform the flight crew that you are a mental health clinician, and outline your current clinical expertise. While the flight crew obtains the medical emergency kit, work to establish rapport with the passenger to identify the psychiatric problem and help de-escalate the situation. Initiate care by1:

- eliciting a psychiatric history

- inquiring about any use of alcohol, illicit substances, or other mood-altering substances (eg, type, amount, and time of use)

- identifying any use of psychotropic medications (eg, doses, last dose taken, and if these agents are on the aircraft).

The Federal Aviation Administration has minimum requirements for the contents of medical emergency kits aboard US airlines.1,4 However, they are not required to contain antipsychotics, naloxone, or benzodiazepines.1,4 Although you may have limited medical resources at your disposal, you can still help passengers in the following ways1:

Monitor vital signs and mental status changes, identify signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal, and assess for respiratory distress. Provide reassurance to the passenger if appropriate.1

Administer naloxone (if available) for suspected opioid ingestion.1 Antiemetics, which are available in these medical kits, can be used if needed. Encourage passengers to remain hydrated and use oxygen as needed.

Continue to: If verbal de-escalation is ineffective...

If verbal de-escalation is ineffective, consider administering a benzodiazepine or antipsychotic (if available).1 If the passenger is combative, refer to the flight crew for the airline’s security protocols, which may include restraining the passenger or diverting the aircraft. Safety takes priority over attempts at medical management.

If the passenger has respiratory distress, instruct the flight crew to contact ground-based medical support for additional recommendations.1

A challenging situation

Ultimately, the pilot coordinates with the flight dispatcher to manage all operational decisions for the aircraft and is responsible for decisions regarding flight diversion.1 In-flight medical volunteers, the flight crew, and ground-based medical experts can offer recommendations for care.1 Cruising at altitudes of 30,000 to 40,000 feet with limited medical equipment, often hours away from the closest medical facility, will create unfamiliar challenges for any medical professional who volunteers for in-flight psychiatric emergencies.1

1. Martin-Gill C, Doyle TJ, Yealy DM. In-flight medical emergencies: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(24):2580-2590.

2. Naouri D, Lapostolle F, Rondet C, et al. Prevention of medical events during air travel: a narrative review. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1000.e1-e6.

3. Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998, 49 USC §44701, 105th Cong, Public Law 170 (1998).

4. Federal Aviation Administration. FAA Advisory circular No 121-33B: emergency medical equipment. https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC121-33B.pdf. Published January 12, 2006. Accessed November 14, 2019.

Although they are rare, in-flight psychiatric emergencies occur because of large numbers of passengers, nonstop flights over longer distances, delayed flights, cramped cabins, and/or alcohol consumption.1,2 Psychiatric symptoms and substance intoxication/withdrawal each represent up to

When a passenger requires medical or psychiatric treatment, the flight crew often requests aid from any trained medical professionals who are on board to augment their capabilities and resources (eg, the flight crew’s training, ground-based medical support).1 In the United States, off-duty medical professionals are not legally required to assist during an in-flight medical emergency.1 The Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998 protects passengers who provide medical assistance from liability, except in cases of gross negligence or willful misconduct.1,3 Flights outside of the United States are governed by a complex combination of public and private international laws.1 Here I suggest how to initiate care during in-flight psychiatric emergencies, and offer therapeutic options to employ for a passenger who is exhibiting psychiatric symptoms.

What to do first

Before volunteering to assist in a mental health emergency, consider your capabilities and limitations. Do not volunteer if you are under the influence of alcohol, illicit substances, or any medications (prescription or over-the-counter) that could affect your judgment.

Inform the flight crew that you are a mental health clinician, and outline your current clinical expertise. While the flight crew obtains the medical emergency kit, work to establish rapport with the passenger to identify the psychiatric problem and help de-escalate the situation. Initiate care by1:

- eliciting a psychiatric history

- inquiring about any use of alcohol, illicit substances, or other mood-altering substances (eg, type, amount, and time of use)

- identifying any use of psychotropic medications (eg, doses, last dose taken, and if these agents are on the aircraft).

The Federal Aviation Administration has minimum requirements for the contents of medical emergency kits aboard US airlines.1,4 However, they are not required to contain antipsychotics, naloxone, or benzodiazepines.1,4 Although you may have limited medical resources at your disposal, you can still help passengers in the following ways1:

Monitor vital signs and mental status changes, identify signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal, and assess for respiratory distress. Provide reassurance to the passenger if appropriate.1

Administer naloxone (if available) for suspected opioid ingestion.1 Antiemetics, which are available in these medical kits, can be used if needed. Encourage passengers to remain hydrated and use oxygen as needed.

Continue to: If verbal de-escalation is ineffective...

If verbal de-escalation is ineffective, consider administering a benzodiazepine or antipsychotic (if available).1 If the passenger is combative, refer to the flight crew for the airline’s security protocols, which may include restraining the passenger or diverting the aircraft. Safety takes priority over attempts at medical management.

If the passenger has respiratory distress, instruct the flight crew to contact ground-based medical support for additional recommendations.1

A challenging situation

Ultimately, the pilot coordinates with the flight dispatcher to manage all operational decisions for the aircraft and is responsible for decisions regarding flight diversion.1 In-flight medical volunteers, the flight crew, and ground-based medical experts can offer recommendations for care.1 Cruising at altitudes of 30,000 to 40,000 feet with limited medical equipment, often hours away from the closest medical facility, will create unfamiliar challenges for any medical professional who volunteers for in-flight psychiatric emergencies.1

Although they are rare, in-flight psychiatric emergencies occur because of large numbers of passengers, nonstop flights over longer distances, delayed flights, cramped cabins, and/or alcohol consumption.1,2 Psychiatric symptoms and substance intoxication/withdrawal each represent up to

When a passenger requires medical or psychiatric treatment, the flight crew often requests aid from any trained medical professionals who are on board to augment their capabilities and resources (eg, the flight crew’s training, ground-based medical support).1 In the United States, off-duty medical professionals are not legally required to assist during an in-flight medical emergency.1 The Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998 protects passengers who provide medical assistance from liability, except in cases of gross negligence or willful misconduct.1,3 Flights outside of the United States are governed by a complex combination of public and private international laws.1 Here I suggest how to initiate care during in-flight psychiatric emergencies, and offer therapeutic options to employ for a passenger who is exhibiting psychiatric symptoms.

What to do first

Before volunteering to assist in a mental health emergency, consider your capabilities and limitations. Do not volunteer if you are under the influence of alcohol, illicit substances, or any medications (prescription or over-the-counter) that could affect your judgment.

Inform the flight crew that you are a mental health clinician, and outline your current clinical expertise. While the flight crew obtains the medical emergency kit, work to establish rapport with the passenger to identify the psychiatric problem and help de-escalate the situation. Initiate care by1:

- eliciting a psychiatric history

- inquiring about any use of alcohol, illicit substances, or other mood-altering substances (eg, type, amount, and time of use)

- identifying any use of psychotropic medications (eg, doses, last dose taken, and if these agents are on the aircraft).

The Federal Aviation Administration has minimum requirements for the contents of medical emergency kits aboard US airlines.1,4 However, they are not required to contain antipsychotics, naloxone, or benzodiazepines.1,4 Although you may have limited medical resources at your disposal, you can still help passengers in the following ways1:

Monitor vital signs and mental status changes, identify signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal, and assess for respiratory distress. Provide reassurance to the passenger if appropriate.1

Administer naloxone (if available) for suspected opioid ingestion.1 Antiemetics, which are available in these medical kits, can be used if needed. Encourage passengers to remain hydrated and use oxygen as needed.

Continue to: If verbal de-escalation is ineffective...

If verbal de-escalation is ineffective, consider administering a benzodiazepine or antipsychotic (if available).1 If the passenger is combative, refer to the flight crew for the airline’s security protocols, which may include restraining the passenger or diverting the aircraft. Safety takes priority over attempts at medical management.

If the passenger has respiratory distress, instruct the flight crew to contact ground-based medical support for additional recommendations.1

A challenging situation

Ultimately, the pilot coordinates with the flight dispatcher to manage all operational decisions for the aircraft and is responsible for decisions regarding flight diversion.1 In-flight medical volunteers, the flight crew, and ground-based medical experts can offer recommendations for care.1 Cruising at altitudes of 30,000 to 40,000 feet with limited medical equipment, often hours away from the closest medical facility, will create unfamiliar challenges for any medical professional who volunteers for in-flight psychiatric emergencies.1

1. Martin-Gill C, Doyle TJ, Yealy DM. In-flight medical emergencies: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(24):2580-2590.

2. Naouri D, Lapostolle F, Rondet C, et al. Prevention of medical events during air travel: a narrative review. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1000.e1-e6.

3. Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998, 49 USC §44701, 105th Cong, Public Law 170 (1998).

4. Federal Aviation Administration. FAA Advisory circular No 121-33B: emergency medical equipment. https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC121-33B.pdf. Published January 12, 2006. Accessed November 14, 2019.

1. Martin-Gill C, Doyle TJ, Yealy DM. In-flight medical emergencies: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(24):2580-2590.

2. Naouri D, Lapostolle F, Rondet C, et al. Prevention of medical events during air travel: a narrative review. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1000.e1-e6.

3. Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998, 49 USC §44701, 105th Cong, Public Law 170 (1998).

4. Federal Aviation Administration. FAA Advisory circular No 121-33B: emergency medical equipment. https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC121-33B.pdf. Published January 12, 2006. Accessed November 14, 2019.