User login

Time series analysis of poison control data

The US Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS) publishes annual reports describing exposures to various substances among the general population.1 Table 22B of each NPDS report shows the number of outcomes from exposures to different pharmacologic treatments in the United States, including psychotropic medications.2 In this Table, the relative morbidity (RM) of a medication is calculated as the ratio of serious outcomes (SO) to single exposures (SE), where SO = moderate + major + death. In this article, I use the NPDS data to demonstrate how time series analysis of the RM ratios for hypertension and psychiatric medications can help predict SO associated with these agents, which may help guide clinicians’ prescribing decisions.2,3

Time series analysis of hypertension medications

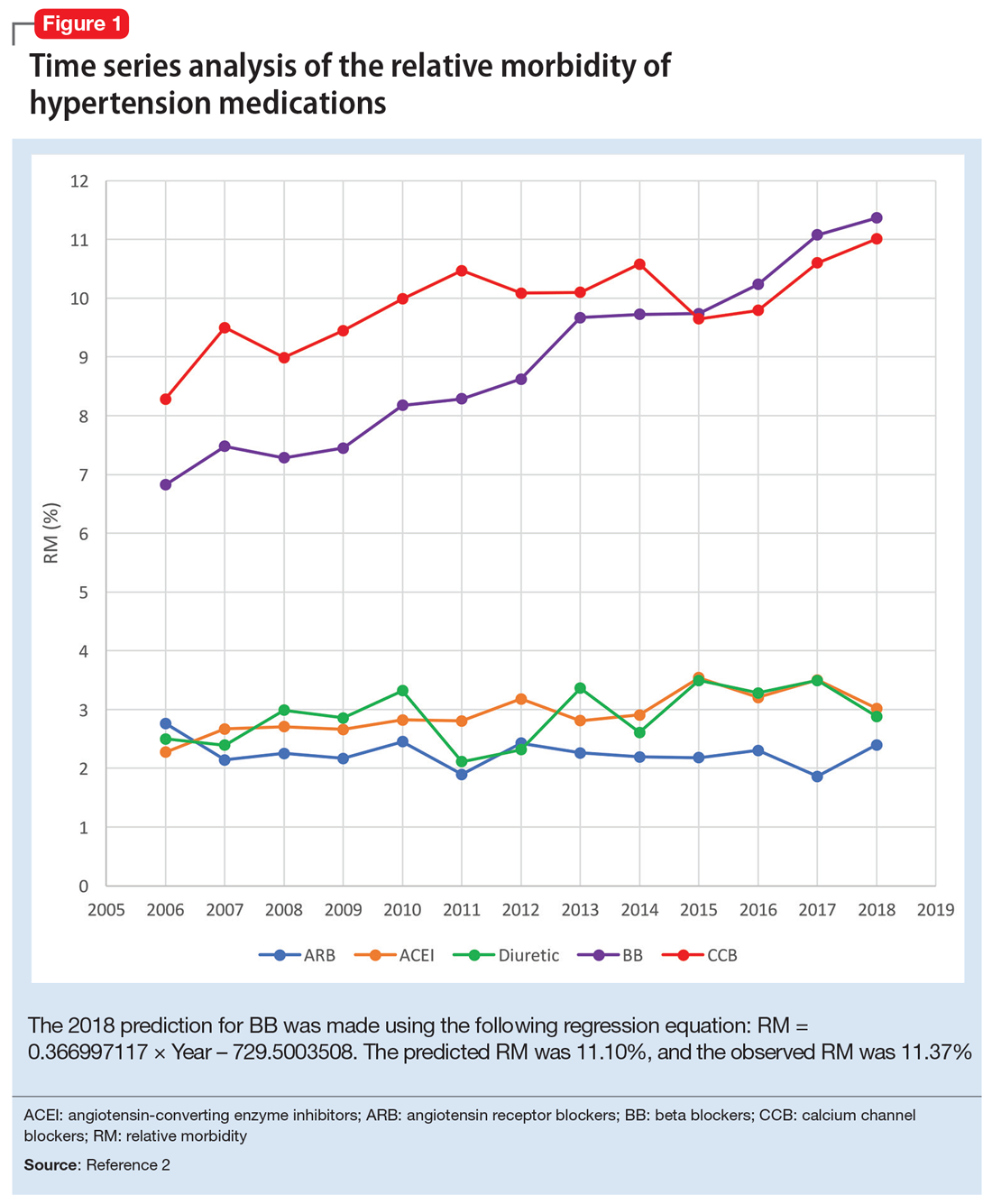

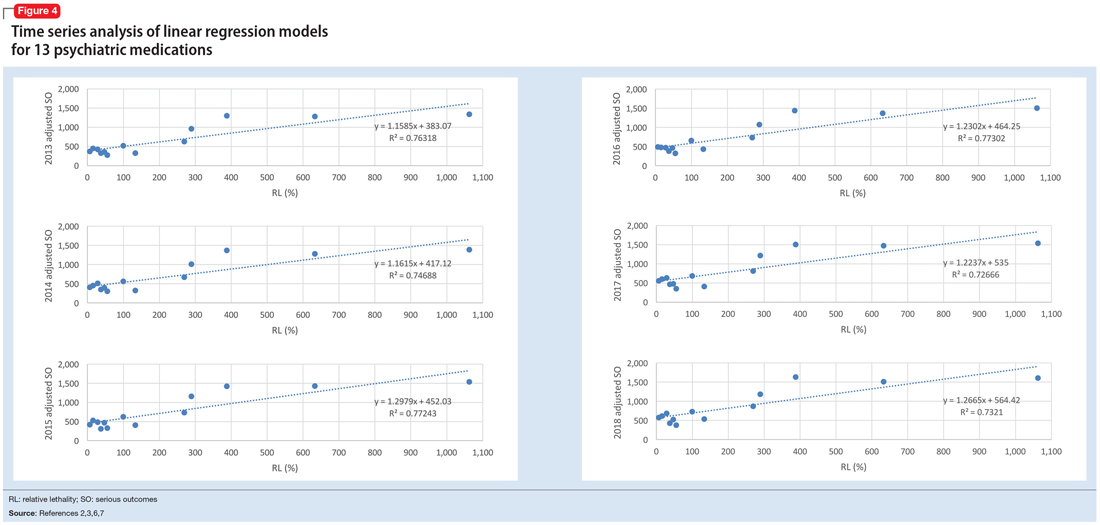

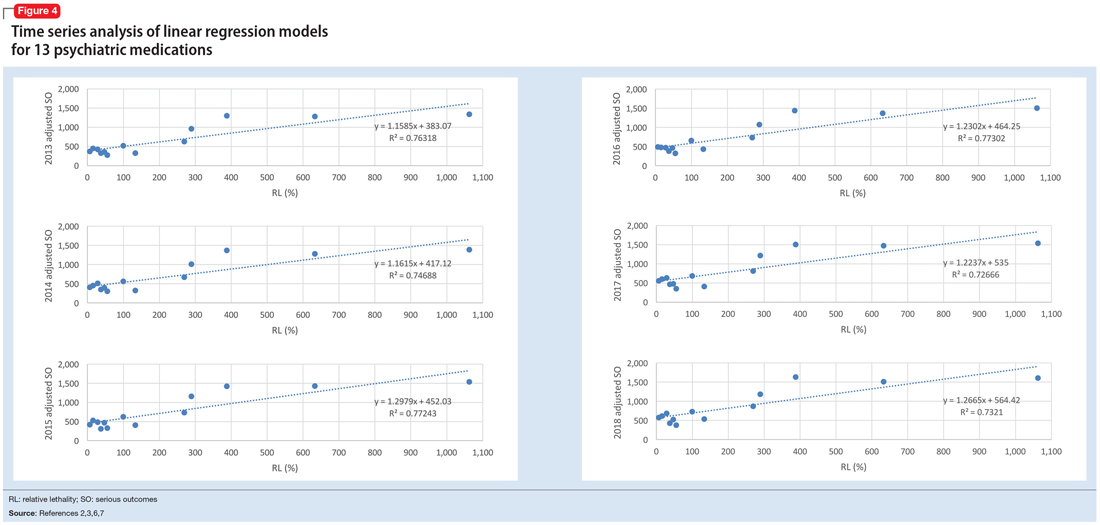

Due to the high prevalence of hypertension, it is not surprising that more suicide deaths occur each year from calcium channel blockers (CCB) than from lithium (37 vs 2, according to 2017 NPDS data).3 I used time series analysis to compare SO during 2006-2017 for 5 classes of hypertension medications: CCB, beta blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and diuretics (Figure 1).

Time series analysis of 2006-2017 data predicted the following number of deaths for 2018: CCB ≥33, BB ≥17, ACEI ≤2, ARB 0, and diuretics ≤1. The observed deaths in 2018 were 41, 23, 0, 0, and 1, respectively.2 The 2018 predicted RM were CCB 10.66%, BB 11.10%, ACEI 3.51%, ARB 2.04%, and diuretics 3.38%. The 2018 observed RM for these medications were 11.01%, 11.37%, 3.02%, 2.40%, and 2.88%, respectively.2

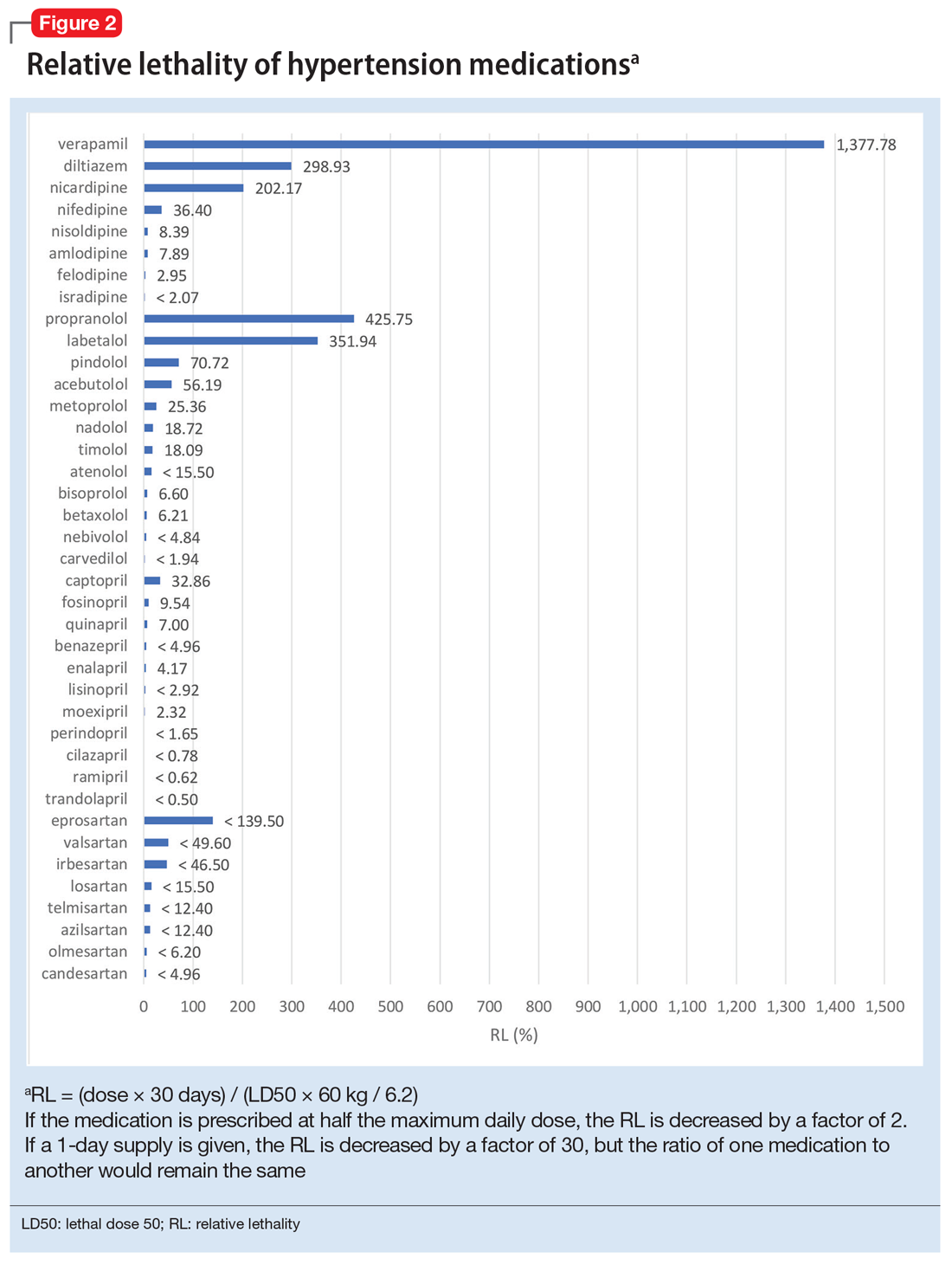

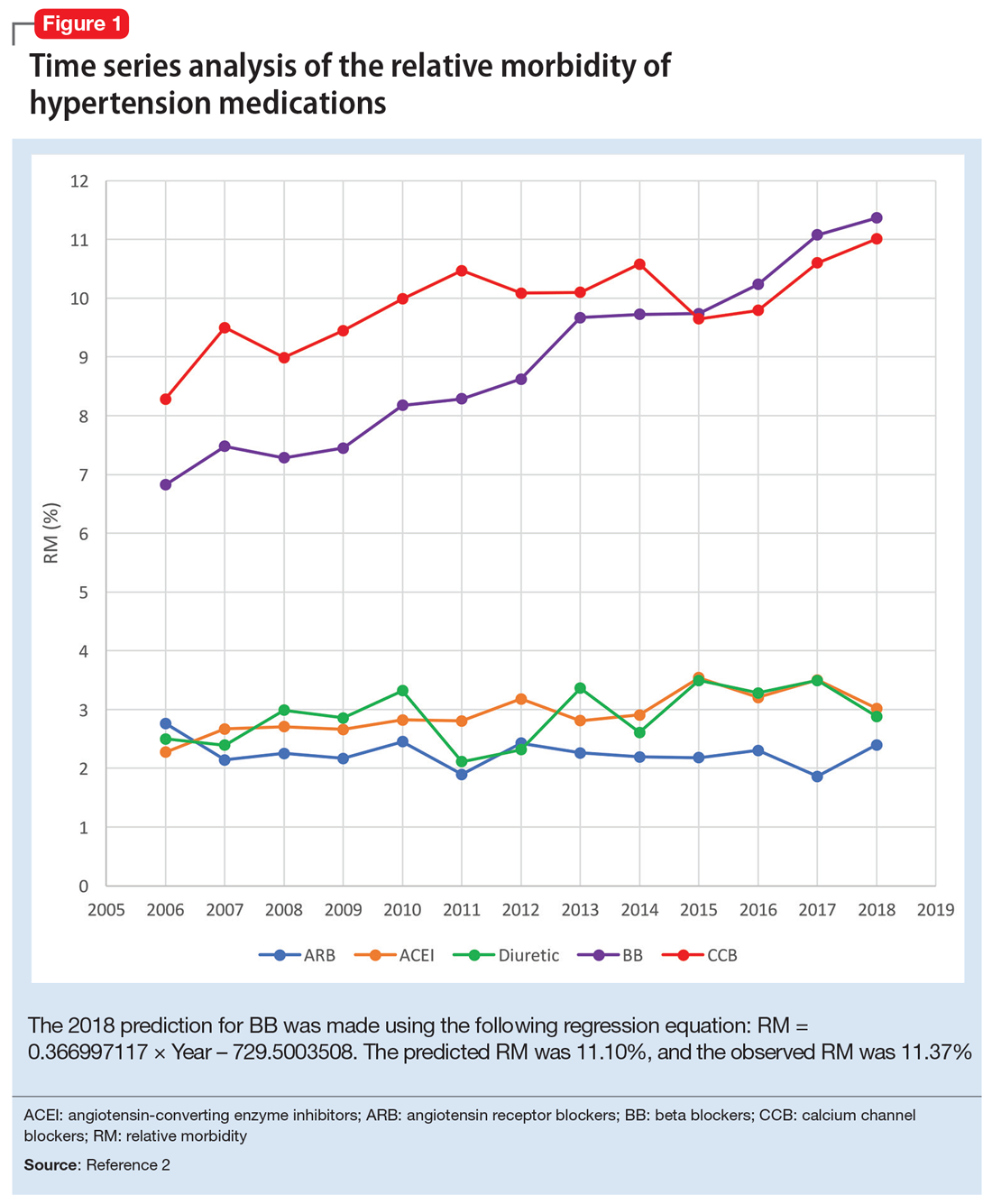

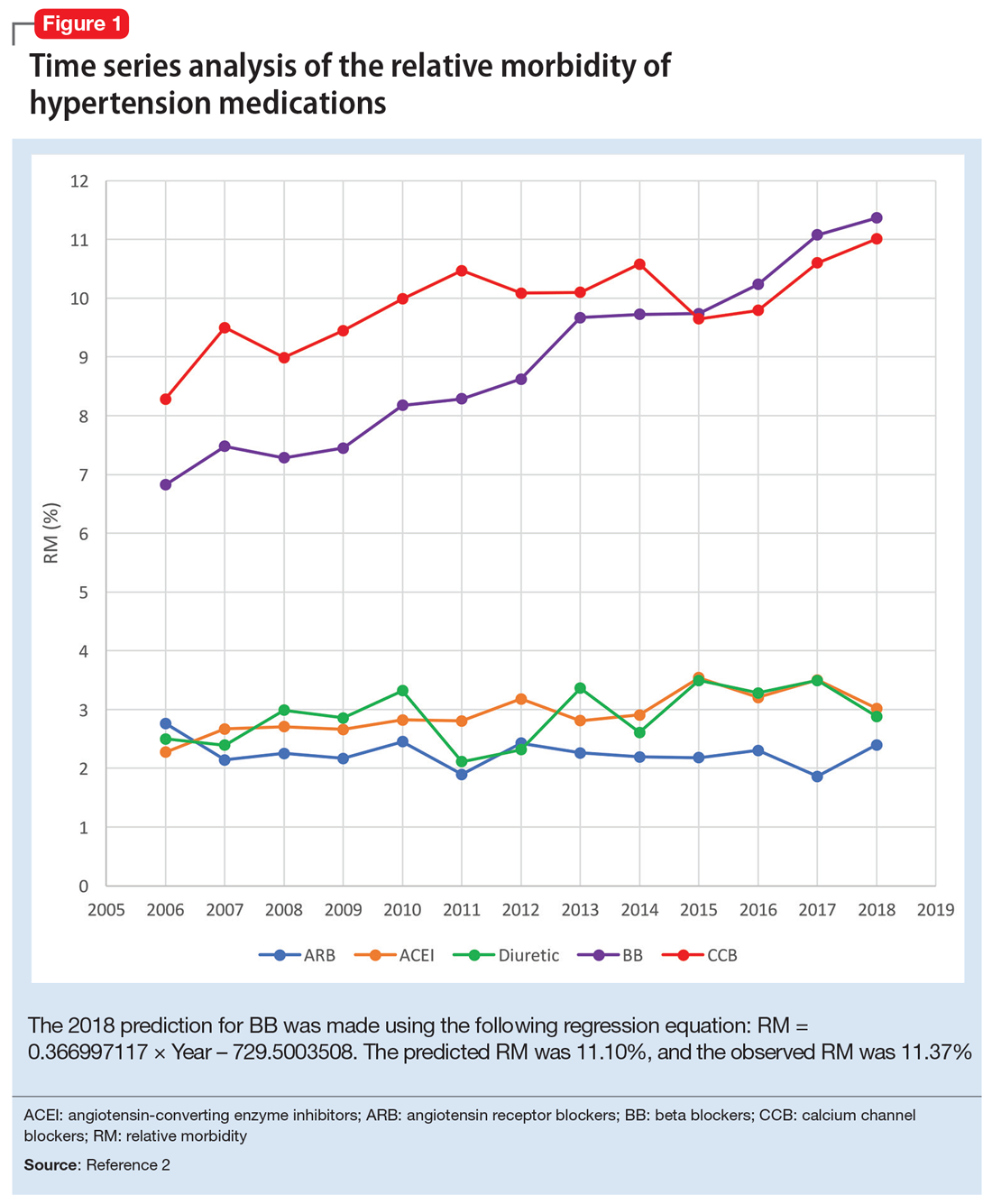

Because the NPDS data for hypertension medications was only provided by class, in order to detect differences within each class, I used the relative lethality (RL) equation: RL = 310x / LD50, where x is the maximum daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days, and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50. The RL equation represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person.4 The RL equation is useful for comparing the safety of various medications, and can help clinicians avoid prescribing a lethal amount of a given medication (Figure 2). For example, the equation shows that among CCB, felodipine is 466 times safer than verapamil and 101 times safer than diltiazem. Not surprisingly, 2006-2018 data shows many deaths via intentional verapamil or diltiazem overdose vs only 1 reference to felodipine. A regression model shows significant correlation and causality between RL and SO over time.5 Integrating all 3 mathematical models suggests that the higher RM of CCB and BB may be caused by the high RL of verapamil, diltiazem, nicardipine, propranolol, and labetalol.

These mathematical models can help physicians consider whether to switch the patient’s current medication to another class with a lower RM. For patients who need a BB or CCB, prescribing a medication with a lower RL within the same class may be another option. The data suggest that avoiding hypertension medications with RL >100% may significantly decrease morbidity and mortality.

Predicting serious outcomes of psychiatric medications

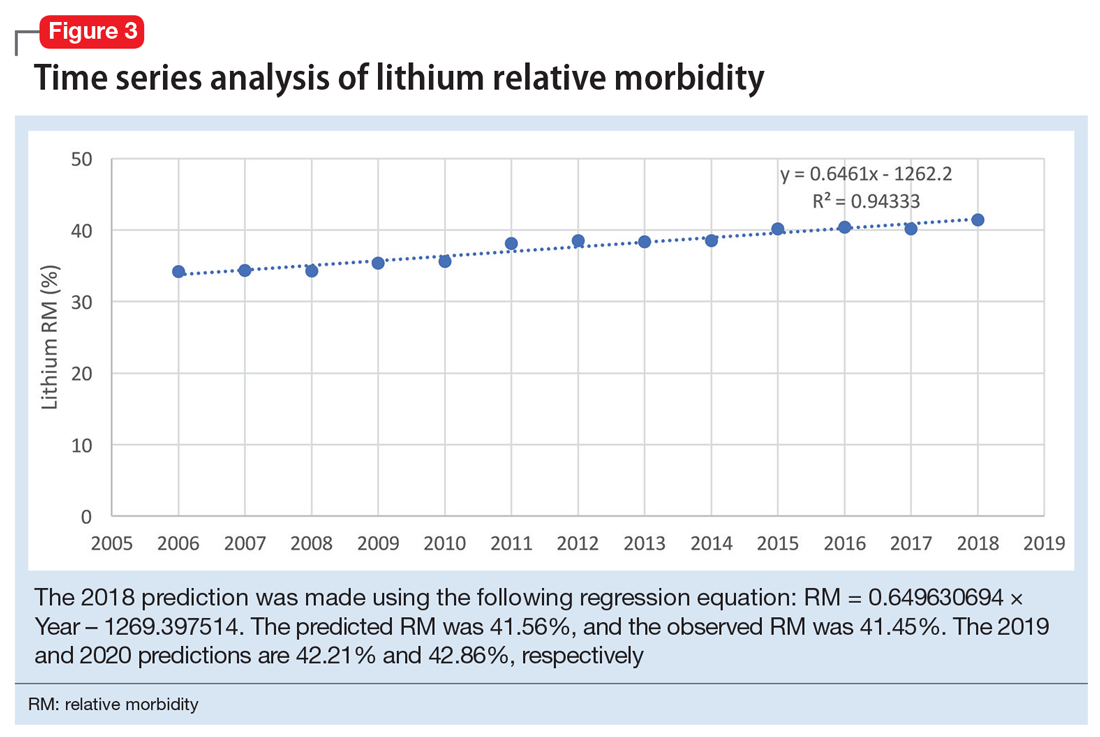

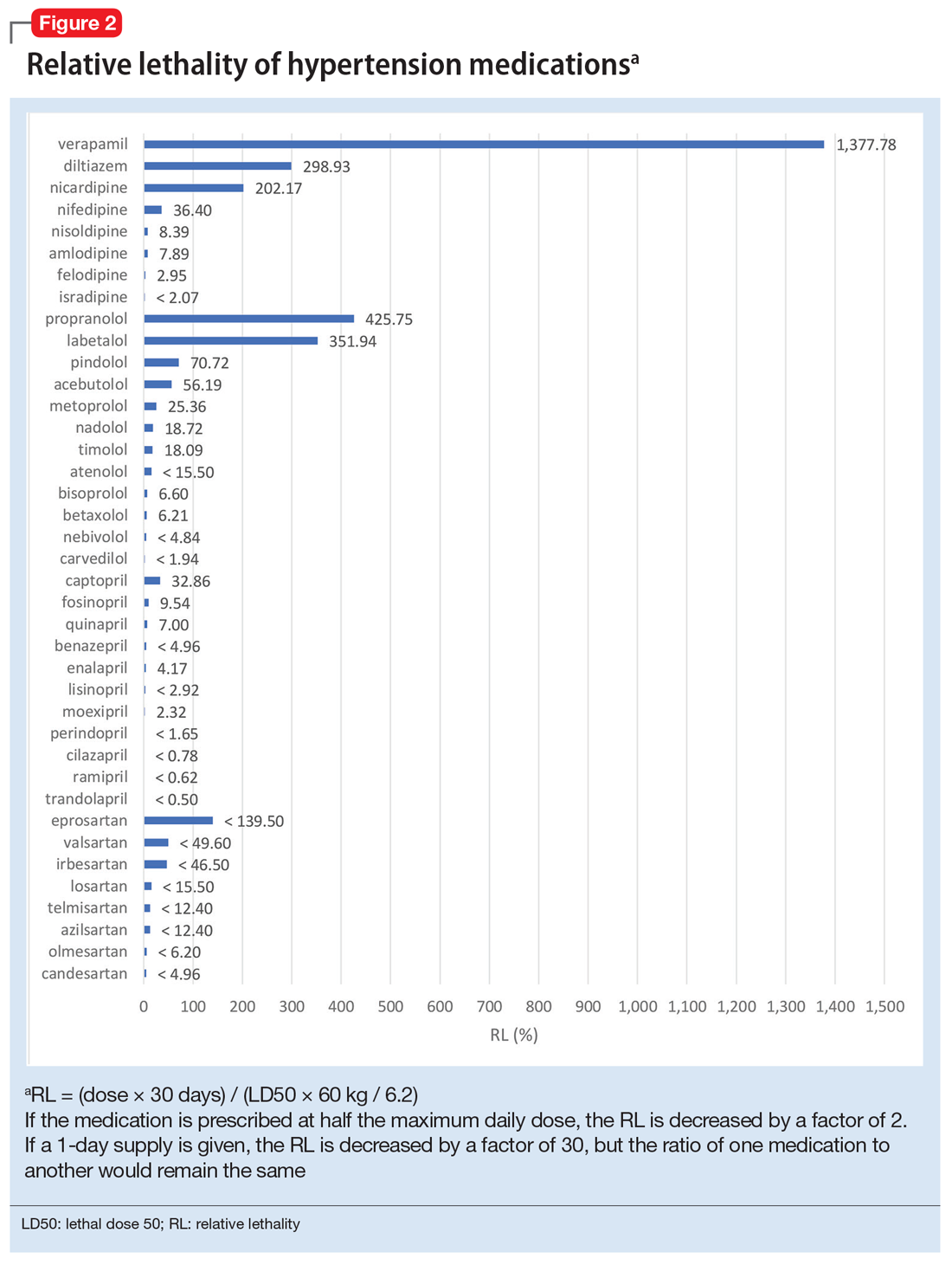

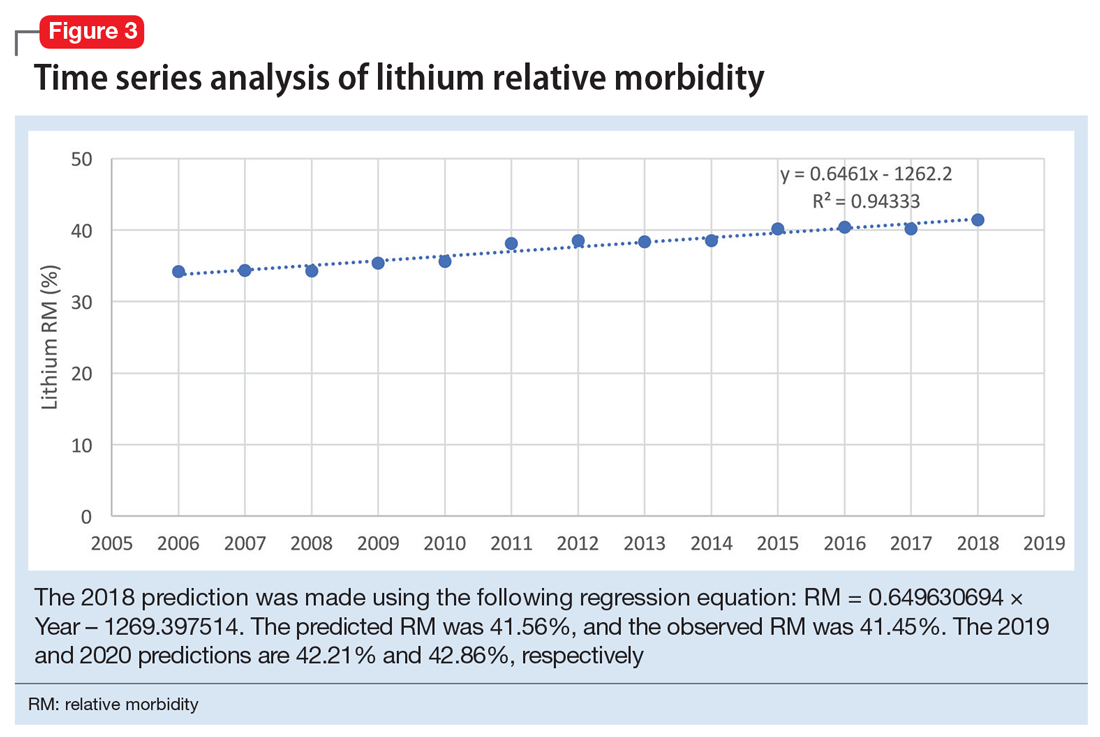

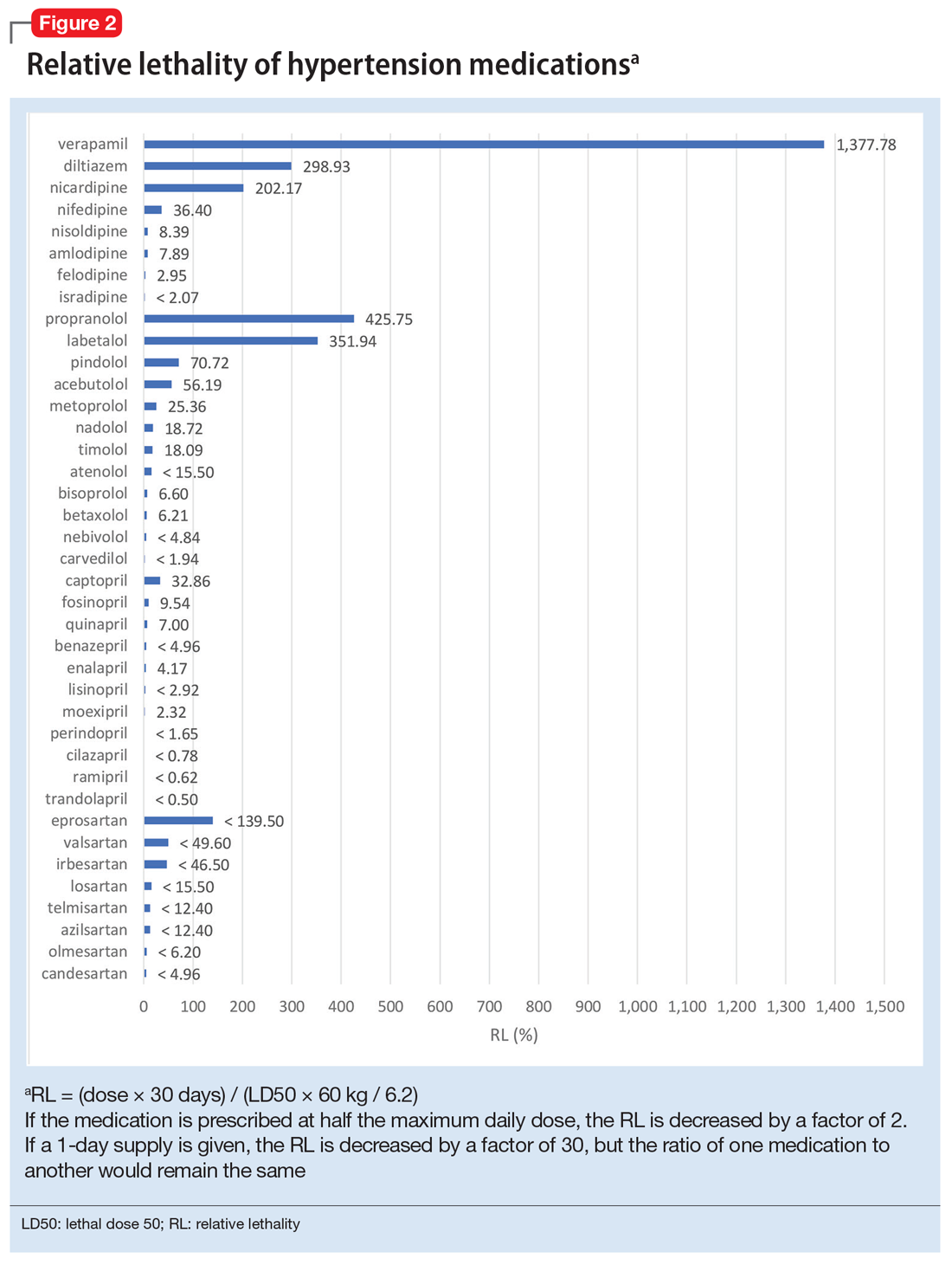

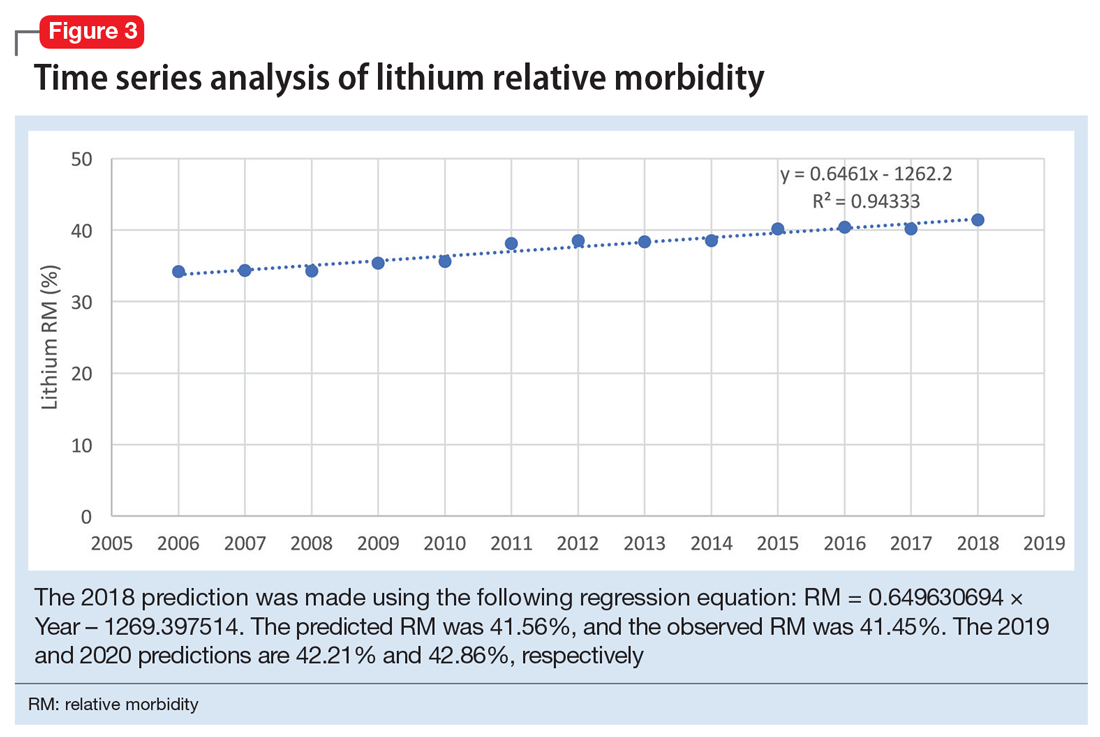

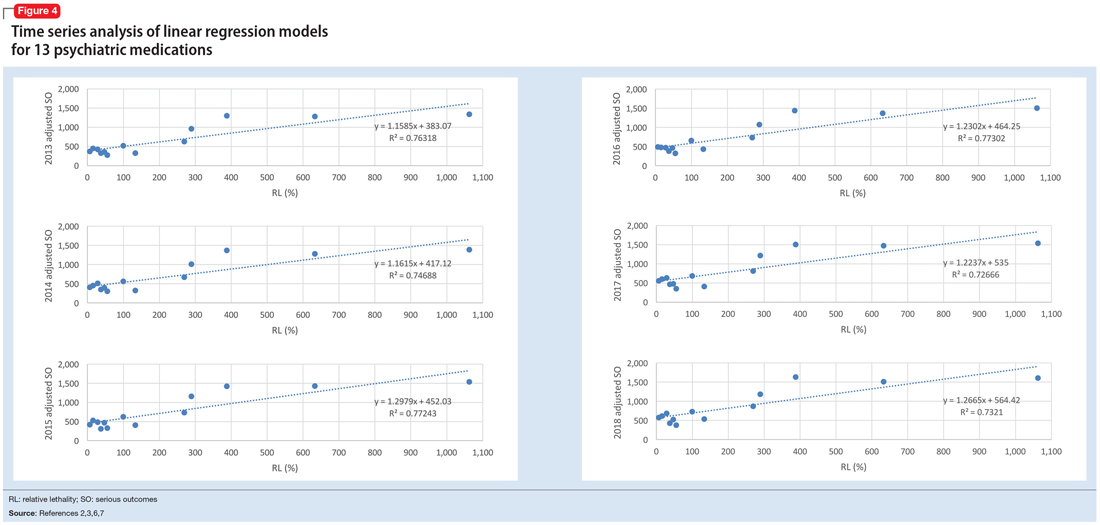

The 2018 NPDS data for psychiatric medications show similarly important results.2 For example, the lithium RM is predictable over time (Figure 3) and has been consistently the highest among psychiatric medications. Using 2006-2017 NPDS data,3 I predicted that the 2018 lithium RM would be 41.56%. The 2018 observed lithium RM was 41.45%.2 I created a linear regression model for each NPDS report from 2013 to 2018 to illustrate the correlation between RL and adjusted SO for 13 psychiatric medications.2,3,6,7 To account for different sample sizes among medications, the lithium SE for each respective year was used for all medications (adjusted SO = SE × RM). A time series analysis of these regression models shows that SO data points hover in the same y-axis region from year to year, with a corresponding RL on the x-axis: escitalopram 6.33%, citalopram 15.50%, mirtazapine 28.47%, paroxetine 37.35%, sertraline 46.72%, fluoxetine 54.87%, venlafaxine 99.64%, duloxetine 133.33%, trazodone 269.57%, bupropion 289.42%, amitriptyline 387.50%, doxepin 632.65%, and lithium 1062.86% (Figure 4). Every year, the scatter plot shape remains approximately the same, which suggests that both SO and RM can be predicted over time. Medications with RL >300% have SO ≈ 1500 (RM ≈ 40%), and those with RL <100% have SO ≈ 500 (RM ≈ 13%).

Time series analysis of NPDS data sheds light on hidden patterns. It may help clinicians discern patterns of potential SO associated with various hypertension and psychiatric medications. RL based on rat experimental data is highly correlated to RM based on human observational data, and the causality is self-evident. On a global scale, data-driven prescribing of medications with RL <100% could potentially help prevent millions of SO every year.

1. National Poison Data System Annual Reports. American Association of Poison Control Centers. https://www.aapcc.org/annual-reports. Updated November 2019. Accessed May 5, 2020.

2. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1220-1413.

3. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2017 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(12):1213-1415.

4. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

5. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

6. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(10):924-1109.

7. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2016 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(10):1072-1252.

The US Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS) publishes annual reports describing exposures to various substances among the general population.1 Table 22B of each NPDS report shows the number of outcomes from exposures to different pharmacologic treatments in the United States, including psychotropic medications.2 In this Table, the relative morbidity (RM) of a medication is calculated as the ratio of serious outcomes (SO) to single exposures (SE), where SO = moderate + major + death. In this article, I use the NPDS data to demonstrate how time series analysis of the RM ratios for hypertension and psychiatric medications can help predict SO associated with these agents, which may help guide clinicians’ prescribing decisions.2,3

Time series analysis of hypertension medications

Due to the high prevalence of hypertension, it is not surprising that more suicide deaths occur each year from calcium channel blockers (CCB) than from lithium (37 vs 2, according to 2017 NPDS data).3 I used time series analysis to compare SO during 2006-2017 for 5 classes of hypertension medications: CCB, beta blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and diuretics (Figure 1).

Time series analysis of 2006-2017 data predicted the following number of deaths for 2018: CCB ≥33, BB ≥17, ACEI ≤2, ARB 0, and diuretics ≤1. The observed deaths in 2018 were 41, 23, 0, 0, and 1, respectively.2 The 2018 predicted RM were CCB 10.66%, BB 11.10%, ACEI 3.51%, ARB 2.04%, and diuretics 3.38%. The 2018 observed RM for these medications were 11.01%, 11.37%, 3.02%, 2.40%, and 2.88%, respectively.2

Because the NPDS data for hypertension medications was only provided by class, in order to detect differences within each class, I used the relative lethality (RL) equation: RL = 310x / LD50, where x is the maximum daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days, and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50. The RL equation represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person.4 The RL equation is useful for comparing the safety of various medications, and can help clinicians avoid prescribing a lethal amount of a given medication (Figure 2). For example, the equation shows that among CCB, felodipine is 466 times safer than verapamil and 101 times safer than diltiazem. Not surprisingly, 2006-2018 data shows many deaths via intentional verapamil or diltiazem overdose vs only 1 reference to felodipine. A regression model shows significant correlation and causality between RL and SO over time.5 Integrating all 3 mathematical models suggests that the higher RM of CCB and BB may be caused by the high RL of verapamil, diltiazem, nicardipine, propranolol, and labetalol.

These mathematical models can help physicians consider whether to switch the patient’s current medication to another class with a lower RM. For patients who need a BB or CCB, prescribing a medication with a lower RL within the same class may be another option. The data suggest that avoiding hypertension medications with RL >100% may significantly decrease morbidity and mortality.

Predicting serious outcomes of psychiatric medications

The 2018 NPDS data for psychiatric medications show similarly important results.2 For example, the lithium RM is predictable over time (Figure 3) and has been consistently the highest among psychiatric medications. Using 2006-2017 NPDS data,3 I predicted that the 2018 lithium RM would be 41.56%. The 2018 observed lithium RM was 41.45%.2 I created a linear regression model for each NPDS report from 2013 to 2018 to illustrate the correlation between RL and adjusted SO for 13 psychiatric medications.2,3,6,7 To account for different sample sizes among medications, the lithium SE for each respective year was used for all medications (adjusted SO = SE × RM). A time series analysis of these regression models shows that SO data points hover in the same y-axis region from year to year, with a corresponding RL on the x-axis: escitalopram 6.33%, citalopram 15.50%, mirtazapine 28.47%, paroxetine 37.35%, sertraline 46.72%, fluoxetine 54.87%, venlafaxine 99.64%, duloxetine 133.33%, trazodone 269.57%, bupropion 289.42%, amitriptyline 387.50%, doxepin 632.65%, and lithium 1062.86% (Figure 4). Every year, the scatter plot shape remains approximately the same, which suggests that both SO and RM can be predicted over time. Medications with RL >300% have SO ≈ 1500 (RM ≈ 40%), and those with RL <100% have SO ≈ 500 (RM ≈ 13%).

Time series analysis of NPDS data sheds light on hidden patterns. It may help clinicians discern patterns of potential SO associated with various hypertension and psychiatric medications. RL based on rat experimental data is highly correlated to RM based on human observational data, and the causality is self-evident. On a global scale, data-driven prescribing of medications with RL <100% could potentially help prevent millions of SO every year.

The US Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS) publishes annual reports describing exposures to various substances among the general population.1 Table 22B of each NPDS report shows the number of outcomes from exposures to different pharmacologic treatments in the United States, including psychotropic medications.2 In this Table, the relative morbidity (RM) of a medication is calculated as the ratio of serious outcomes (SO) to single exposures (SE), where SO = moderate + major + death. In this article, I use the NPDS data to demonstrate how time series analysis of the RM ratios for hypertension and psychiatric medications can help predict SO associated with these agents, which may help guide clinicians’ prescribing decisions.2,3

Time series analysis of hypertension medications

Due to the high prevalence of hypertension, it is not surprising that more suicide deaths occur each year from calcium channel blockers (CCB) than from lithium (37 vs 2, according to 2017 NPDS data).3 I used time series analysis to compare SO during 2006-2017 for 5 classes of hypertension medications: CCB, beta blockers (BB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and diuretics (Figure 1).

Time series analysis of 2006-2017 data predicted the following number of deaths for 2018: CCB ≥33, BB ≥17, ACEI ≤2, ARB 0, and diuretics ≤1. The observed deaths in 2018 were 41, 23, 0, 0, and 1, respectively.2 The 2018 predicted RM were CCB 10.66%, BB 11.10%, ACEI 3.51%, ARB 2.04%, and diuretics 3.38%. The 2018 observed RM for these medications were 11.01%, 11.37%, 3.02%, 2.40%, and 2.88%, respectively.2

Because the NPDS data for hypertension medications was only provided by class, in order to detect differences within each class, I used the relative lethality (RL) equation: RL = 310x / LD50, where x is the maximum daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days, and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50. The RL equation represents the ratio of a 30-day supply of medication to the human equivalent LD50 for a 60-kg person.4 The RL equation is useful for comparing the safety of various medications, and can help clinicians avoid prescribing a lethal amount of a given medication (Figure 2). For example, the equation shows that among CCB, felodipine is 466 times safer than verapamil and 101 times safer than diltiazem. Not surprisingly, 2006-2018 data shows many deaths via intentional verapamil or diltiazem overdose vs only 1 reference to felodipine. A regression model shows significant correlation and causality between RL and SO over time.5 Integrating all 3 mathematical models suggests that the higher RM of CCB and BB may be caused by the high RL of verapamil, diltiazem, nicardipine, propranolol, and labetalol.

These mathematical models can help physicians consider whether to switch the patient’s current medication to another class with a lower RM. For patients who need a BB or CCB, prescribing a medication with a lower RL within the same class may be another option. The data suggest that avoiding hypertension medications with RL >100% may significantly decrease morbidity and mortality.

Predicting serious outcomes of psychiatric medications

The 2018 NPDS data for psychiatric medications show similarly important results.2 For example, the lithium RM is predictable over time (Figure 3) and has been consistently the highest among psychiatric medications. Using 2006-2017 NPDS data,3 I predicted that the 2018 lithium RM would be 41.56%. The 2018 observed lithium RM was 41.45%.2 I created a linear regression model for each NPDS report from 2013 to 2018 to illustrate the correlation between RL and adjusted SO for 13 psychiatric medications.2,3,6,7 To account for different sample sizes among medications, the lithium SE for each respective year was used for all medications (adjusted SO = SE × RM). A time series analysis of these regression models shows that SO data points hover in the same y-axis region from year to year, with a corresponding RL on the x-axis: escitalopram 6.33%, citalopram 15.50%, mirtazapine 28.47%, paroxetine 37.35%, sertraline 46.72%, fluoxetine 54.87%, venlafaxine 99.64%, duloxetine 133.33%, trazodone 269.57%, bupropion 289.42%, amitriptyline 387.50%, doxepin 632.65%, and lithium 1062.86% (Figure 4). Every year, the scatter plot shape remains approximately the same, which suggests that both SO and RM can be predicted over time. Medications with RL >300% have SO ≈ 1500 (RM ≈ 40%), and those with RL <100% have SO ≈ 500 (RM ≈ 13%).

Time series analysis of NPDS data sheds light on hidden patterns. It may help clinicians discern patterns of potential SO associated with various hypertension and psychiatric medications. RL based on rat experimental data is highly correlated to RM based on human observational data, and the causality is self-evident. On a global scale, data-driven prescribing of medications with RL <100% could potentially help prevent millions of SO every year.

1. National Poison Data System Annual Reports. American Association of Poison Control Centers. https://www.aapcc.org/annual-reports. Updated November 2019. Accessed May 5, 2020.

2. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1220-1413.

3. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2017 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(12):1213-1415.

4. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

5. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

6. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(10):924-1109.

7. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2016 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(10):1072-1252.

1. National Poison Data System Annual Reports. American Association of Poison Control Centers. https://www.aapcc.org/annual-reports. Updated November 2019. Accessed May 5, 2020.

2. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2018 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 36th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1220-1413.

3. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2017 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(12):1213-1415.

4. Giurca D. Decreasing suicide risk with math. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):57-59,A,B.

5. Giurca D. Data-driven prescribing. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(10):e6-e8.

6. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(10):924-1109.

7. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2016 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(10):1072-1252.

Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: Understanding the rules

In addition to affecting our personal lives, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has altered the way we practice psychiatry. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of mental health services via remote communication—is being used to replace face-to-face outpatient encounters. Several rules and regulations governing the provision of care and prescribing have been temporarily modified or suspended to allow clinicians to more easily use telepsychiatry to care for their patients. Although these requirements are continually changing, here I review some of the telepsychiatry rules and regulations clinicians need to understand to minimize their risk for liability.

Changes in light of COVID-19

In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance that allows Medicare beneficiaries to receive various services at home through telehealth without having to travel to a doctor’s office or hospital.1 Many commercial insurers also are allowing patients to receive telehealth services in their home. The US Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights, which enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), reported in March 2020 that it will not impose penalties for not complying with HIPAA requirements on clinicians who provide good-faith telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 crisis.2

Clinicians who want to use audio or video remote communication to provide any type of telehealth services (not just those related to COVID-19) should use “non-public facing” products.2 Non-public facing products (eg, Skype, WhatsApp video call, Zoom) allow only the intended parties to participate in the communication.3 Usually, these products employ end-to-end encryption, which allows only those engaging in communication to see and hear what is transmitted.3 To limit access and verify the participants, these products also support individual user accounts, login names, and passwords.3 In addition, these products usually allow participants and/or “the host” to exert some degree of control over particular features, such as choosing to record the communication, mute, or turn off the video or audio signal.3 When using these products, clinicians should enable all available encryption and privacy modes.2

“Public-facing” products (eg, Facebook Live, TikTok, Twitch) should not be used to provide telepsychiatry services because they are designed to be open to the public or allow for wide or indiscriminate access to the communication.2,3 Clinicians who desire additional privacy protections (and a more permanent solution) should choose a HIPAA-compliant telehealth vendor (eg, Doxy.me, VSee, Zoom for Healthcare) and obtain a Business Associate Agreement with the vendor to ensure data protection and security.2,4

Regardless of the product, obtain informed consent from your patients that authorizes the use of remote communication.4 Inform your patients of any potential privacy or security breaches, the need for interactions to be conducted in a location that provides privacy, and whether the specific technology used is HIPAA-compliant.4 Document that your patients understand these issues before using remote communication.4

How licensing requirements have changed

As of March 31, 2020, the CMS temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state clinicians be licensed in the state where they are providing services to Medicare beneficiaries.5 The CMS waived this requirement for clinicians who meet the following 4 conditions5,6:

- must be enrolled in Medicare

- must possess a valid license to practice in the state that relates to his/her Medicare enrollment

- are furnishing services—whether in person or via telepsychiatry—in a state where the emergency is occurring to contribute to relief efforts in his/her professional capacity

- are not excluded from practicing in any state that is part of the nationally declared emergency area.

Note that individual state licensure requirements continue to apply unless waived by the state.6 Therefore, in order for clinicians to see Medicare patients via remote communication under the 4 conditions described above, the state also would have to waive its licensure requirements for the type of practice for which the clinicians are licensed in their own state.6 Regarding commercial payers, in general, clinicians providing telepsychiatry services need a license to practice in the state where the patient is located at the time services are provided.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many governors issued executive orders waiving licensure requirements, and many have accelerated granting temporary licenses to out-of-state clinicians who wish to provide telepsychiatry services to the residents of their state.4

Continue to: Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Effective March 31, 2020 and lasting for the duration of COVID-19 emergency declaration, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) suspended the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which requires clinicians to conduct initial, in-person examinations of patients before they can prescribe controlled substances electronically.6,7 The DEA suspension allows clinicians to prescribe controlled substances after conducting an initial evaluation via remote communication. In addition, the DEA waived the requirement that a clinician needs to hold a DEA license in the state where the patient is located to be able to prescribe a controlled substance electronically.4,6 However, you still must comply with all other state laws and regulations for prescribing controlled substances.4

Staying informed

Although several telepsychiatry rules and regulations have been modified or suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, the standard of care for services rendered via telepsychiatry remains the same as services provided via face-to-face encounters, including patient evaluation and assessment, treatment plans, medication, and documentation.4 Clinicians can keep up-to-date on how practicing telepsychiatry may evolve during these times by using the following resources from the American Psychiatric Association:

- Telepsychiatry Toolkit: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry

- Practice Guidance for COVID-19: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus/practice-guidance-for-covid-19.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19: President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-educationoutreachffsprovpartprogprovider-partnership-email-archive/2020-03-17. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

3. US Department of Health & Human Services. What is a “non-public facing” remote communication product? https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/3024/what-is-a-non-public-facing-remote-communication-product/index.html. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

4. Huben-Kearney A. Risk management amid a global pandemic. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.5a38. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Published April 29, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Update on telehealth restrictions in response to COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/blog/apa-resources-on-telepsychiatry-and-covid-19. Updated May 1, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

7. US Drug Enforcement Agency. How to prescribe controlled substances to patients during the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-023)(DEA075)Decision_Tree_(Final)_33120_2007.pdf. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed on May 6, 2020.

In addition to affecting our personal lives, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has altered the way we practice psychiatry. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of mental health services via remote communication—is being used to replace face-to-face outpatient encounters. Several rules and regulations governing the provision of care and prescribing have been temporarily modified or suspended to allow clinicians to more easily use telepsychiatry to care for their patients. Although these requirements are continually changing, here I review some of the telepsychiatry rules and regulations clinicians need to understand to minimize their risk for liability.

Changes in light of COVID-19

In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance that allows Medicare beneficiaries to receive various services at home through telehealth without having to travel to a doctor’s office or hospital.1 Many commercial insurers also are allowing patients to receive telehealth services in their home. The US Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights, which enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), reported in March 2020 that it will not impose penalties for not complying with HIPAA requirements on clinicians who provide good-faith telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 crisis.2

Clinicians who want to use audio or video remote communication to provide any type of telehealth services (not just those related to COVID-19) should use “non-public facing” products.2 Non-public facing products (eg, Skype, WhatsApp video call, Zoom) allow only the intended parties to participate in the communication.3 Usually, these products employ end-to-end encryption, which allows only those engaging in communication to see and hear what is transmitted.3 To limit access and verify the participants, these products also support individual user accounts, login names, and passwords.3 In addition, these products usually allow participants and/or “the host” to exert some degree of control over particular features, such as choosing to record the communication, mute, or turn off the video or audio signal.3 When using these products, clinicians should enable all available encryption and privacy modes.2

“Public-facing” products (eg, Facebook Live, TikTok, Twitch) should not be used to provide telepsychiatry services because they are designed to be open to the public or allow for wide or indiscriminate access to the communication.2,3 Clinicians who desire additional privacy protections (and a more permanent solution) should choose a HIPAA-compliant telehealth vendor (eg, Doxy.me, VSee, Zoom for Healthcare) and obtain a Business Associate Agreement with the vendor to ensure data protection and security.2,4

Regardless of the product, obtain informed consent from your patients that authorizes the use of remote communication.4 Inform your patients of any potential privacy or security breaches, the need for interactions to be conducted in a location that provides privacy, and whether the specific technology used is HIPAA-compliant.4 Document that your patients understand these issues before using remote communication.4

How licensing requirements have changed

As of March 31, 2020, the CMS temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state clinicians be licensed in the state where they are providing services to Medicare beneficiaries.5 The CMS waived this requirement for clinicians who meet the following 4 conditions5,6:

- must be enrolled in Medicare

- must possess a valid license to practice in the state that relates to his/her Medicare enrollment

- are furnishing services—whether in person or via telepsychiatry—in a state where the emergency is occurring to contribute to relief efforts in his/her professional capacity

- are not excluded from practicing in any state that is part of the nationally declared emergency area.

Note that individual state licensure requirements continue to apply unless waived by the state.6 Therefore, in order for clinicians to see Medicare patients via remote communication under the 4 conditions described above, the state also would have to waive its licensure requirements for the type of practice for which the clinicians are licensed in their own state.6 Regarding commercial payers, in general, clinicians providing telepsychiatry services need a license to practice in the state where the patient is located at the time services are provided.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many governors issued executive orders waiving licensure requirements, and many have accelerated granting temporary licenses to out-of-state clinicians who wish to provide telepsychiatry services to the residents of their state.4

Continue to: Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Effective March 31, 2020 and lasting for the duration of COVID-19 emergency declaration, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) suspended the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which requires clinicians to conduct initial, in-person examinations of patients before they can prescribe controlled substances electronically.6,7 The DEA suspension allows clinicians to prescribe controlled substances after conducting an initial evaluation via remote communication. In addition, the DEA waived the requirement that a clinician needs to hold a DEA license in the state where the patient is located to be able to prescribe a controlled substance electronically.4,6 However, you still must comply with all other state laws and regulations for prescribing controlled substances.4

Staying informed

Although several telepsychiatry rules and regulations have been modified or suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, the standard of care for services rendered via telepsychiatry remains the same as services provided via face-to-face encounters, including patient evaluation and assessment, treatment plans, medication, and documentation.4 Clinicians can keep up-to-date on how practicing telepsychiatry may evolve during these times by using the following resources from the American Psychiatric Association:

- Telepsychiatry Toolkit: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry

- Practice Guidance for COVID-19: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus/practice-guidance-for-covid-19.

In addition to affecting our personal lives, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has altered the way we practice psychiatry. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of mental health services via remote communication—is being used to replace face-to-face outpatient encounters. Several rules and regulations governing the provision of care and prescribing have been temporarily modified or suspended to allow clinicians to more easily use telepsychiatry to care for their patients. Although these requirements are continually changing, here I review some of the telepsychiatry rules and regulations clinicians need to understand to minimize their risk for liability.

Changes in light of COVID-19

In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance that allows Medicare beneficiaries to receive various services at home through telehealth without having to travel to a doctor’s office or hospital.1 Many commercial insurers also are allowing patients to receive telehealth services in their home. The US Department of Health & Human Services Office for Civil Rights, which enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), reported in March 2020 that it will not impose penalties for not complying with HIPAA requirements on clinicians who provide good-faith telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 crisis.2

Clinicians who want to use audio or video remote communication to provide any type of telehealth services (not just those related to COVID-19) should use “non-public facing” products.2 Non-public facing products (eg, Skype, WhatsApp video call, Zoom) allow only the intended parties to participate in the communication.3 Usually, these products employ end-to-end encryption, which allows only those engaging in communication to see and hear what is transmitted.3 To limit access and verify the participants, these products also support individual user accounts, login names, and passwords.3 In addition, these products usually allow participants and/or “the host” to exert some degree of control over particular features, such as choosing to record the communication, mute, or turn off the video or audio signal.3 When using these products, clinicians should enable all available encryption and privacy modes.2

“Public-facing” products (eg, Facebook Live, TikTok, Twitch) should not be used to provide telepsychiatry services because they are designed to be open to the public or allow for wide or indiscriminate access to the communication.2,3 Clinicians who desire additional privacy protections (and a more permanent solution) should choose a HIPAA-compliant telehealth vendor (eg, Doxy.me, VSee, Zoom for Healthcare) and obtain a Business Associate Agreement with the vendor to ensure data protection and security.2,4

Regardless of the product, obtain informed consent from your patients that authorizes the use of remote communication.4 Inform your patients of any potential privacy or security breaches, the need for interactions to be conducted in a location that provides privacy, and whether the specific technology used is HIPAA-compliant.4 Document that your patients understand these issues before using remote communication.4

How licensing requirements have changed

As of March 31, 2020, the CMS temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state clinicians be licensed in the state where they are providing services to Medicare beneficiaries.5 The CMS waived this requirement for clinicians who meet the following 4 conditions5,6:

- must be enrolled in Medicare

- must possess a valid license to practice in the state that relates to his/her Medicare enrollment

- are furnishing services—whether in person or via telepsychiatry—in a state where the emergency is occurring to contribute to relief efforts in his/her professional capacity

- are not excluded from practicing in any state that is part of the nationally declared emergency area.

Note that individual state licensure requirements continue to apply unless waived by the state.6 Therefore, in order for clinicians to see Medicare patients via remote communication under the 4 conditions described above, the state also would have to waive its licensure requirements for the type of practice for which the clinicians are licensed in their own state.6 Regarding commercial payers, in general, clinicians providing telepsychiatry services need a license to practice in the state where the patient is located at the time services are provided.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many governors issued executive orders waiving licensure requirements, and many have accelerated granting temporary licenses to out-of-state clinicians who wish to provide telepsychiatry services to the residents of their state.4

Continue to: Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Prescribing via telepsychiatry

Effective March 31, 2020 and lasting for the duration of COVID-19 emergency declaration, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) suspended the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which requires clinicians to conduct initial, in-person examinations of patients before they can prescribe controlled substances electronically.6,7 The DEA suspension allows clinicians to prescribe controlled substances after conducting an initial evaluation via remote communication. In addition, the DEA waived the requirement that a clinician needs to hold a DEA license in the state where the patient is located to be able to prescribe a controlled substance electronically.4,6 However, you still must comply with all other state laws and regulations for prescribing controlled substances.4

Staying informed

Although several telepsychiatry rules and regulations have been modified or suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, the standard of care for services rendered via telepsychiatry remains the same as services provided via face-to-face encounters, including patient evaluation and assessment, treatment plans, medication, and documentation.4 Clinicians can keep up-to-date on how practicing telepsychiatry may evolve during these times by using the following resources from the American Psychiatric Association:

- Telepsychiatry Toolkit: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry

- Practice Guidance for COVID-19: www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus/practice-guidance-for-covid-19.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19: President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-educationoutreachffsprovpartprogprovider-partnership-email-archive/2020-03-17. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

3. US Department of Health & Human Services. What is a “non-public facing” remote communication product? https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/3024/what-is-a-non-public-facing-remote-communication-product/index.html. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

4. Huben-Kearney A. Risk management amid a global pandemic. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.5a38. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Published April 29, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Update on telehealth restrictions in response to COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/blog/apa-resources-on-telepsychiatry-and-covid-19. Updated May 1, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

7. US Drug Enforcement Agency. How to prescribe controlled substances to patients during the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-023)(DEA075)Decision_Tree_(Final)_33120_2007.pdf. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed on May 6, 2020.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19: President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-educationoutreachffsprovpartprogprovider-partnership-email-archive/2020-03-17. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

3. US Department of Health & Human Services. What is a “non-public facing” remote communication product? https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/3024/what-is-a-non-public-facing-remote-communication-product/index.html. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

4. Huben-Kearney A. Risk management amid a global pandemic. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.5a38. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Published April 29, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Update on telehealth restrictions in response to COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/blog/apa-resources-on-telepsychiatry-and-covid-19. Updated May 1, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

7. US Drug Enforcement Agency. How to prescribe controlled substances to patients during the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-023)(DEA075)Decision_Tree_(Final)_33120_2007.pdf. Published March 31, 2020. Accessed on May 6, 2020.

Taking care of ourselves during the COVID-19 pandemic

Since early March 2020, when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the

COVID-19 has created uncertainty in our lives, both professionally and personally. This can be difficult to face because we are programmed to desire certainty, to want to know what is happening around us, and to notice threatening people and/or situations.2 Uncertainty can lead us to feel stressed or overwhelmed due to a sense of losing control.2 Our mental and physical well-being can begin to deteriorate. We can feel more frazzled, angry, helpless, sad, frustrated, or confused,2 and we can become more isolated. These thoughts and feelings can make our daily activities more cumbersome.

To maintain our own mental and physical well-being, we must give ourselves permission to change the narrative from “the patient is always first” to “the patient always—but not always first.”3 Doing so will allow us to continue to help our patients.3 Despite the pervasive uncertainty, taking the following actions can help us to maintain our own mental and physical health.2-5

Minimize news that causes us to feel worse. COVID-19 news dominates the headlines. The near-constant, ever-changing stream of reports can cause us to feel overwhelmed and stressed. We should get information only from trusted sources, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO, and do so only once or twice a day. We should seek out only facts, and not focus on rumors that could worsen our thoughts and feelings.

Social distancing does not mean social isolation. To reduce the spread of COVID-19, social distancing has become necessary, but we should not completely avoid each other. We can still communicate with others via texting, e-mail, social media, video conferences, and phone calls. Despite not being able to engage in socially accepted physical greetings such as handshakes or hugs, we should not hesitate to verbally greet each other, albeit from a distance. In addition, we can still go outside while maintaining a safe distance from each other.

Keep a routine. Because we are creatures of habit, a routine (even a new one) can help sustain our mental and physical well-being. We should continue to:

- remain active at our usual times

- get adequate sleep and rest

- eat nutritious food

- engage in physical activity

- maintain contact with our family and friends

- continue treatments for any physical and/or mental conditions.

Avoid unhealthy coping strategies, such as binge-watching TV shows, because these can worsen psychological and physical well-being. You are likely to know what to do to “de-stress” yourself, and you should not hesitate to keep yourself psychologically and physically fit. Continue to engage in CDC-recommended hygienic practices such as frequently washing your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, avoiding close contact with people who are sick, and staying at home when you are sick. Seek mental health and/or medical treatment as necessary.

Continue to: Put the uncertainty in perspective

Put the uncertainty in perspective. Hopefully, there will come a time when we will resume our normal lives. Until then, we should acknowledge the uncertainty without immediately reacting to the worries that it creates. It is important to take a step back and think before reacting. This involves challenging ourselves to stay in the present and resist projecting into the future. Use this time for self-care, reflection, and/or catching up on the “to-do list.” We should be kind to ourselves and those around us. As best we can, we should show empathy to others and try to help our friends, families, and colleagues who are having a difficult time managing this crisis.

1. Ghebreyesus TA. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

2. Marshall D. Taking care of your mental health in the face of uncertainty. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. https://afsp.org/taking-care-of-your-mental-health-in-the-face-of-uncertainty/. Published March 10, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

3. Unadkat S, Farquhar M. Doctors’ wellbeing: self-care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1150. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1150.

4. World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVD-19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf. Published March 18, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

5. Brewer K. Coronavirus: how to protect your mental health. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-51873799. Published March 16, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

Since early March 2020, when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the

COVID-19 has created uncertainty in our lives, both professionally and personally. This can be difficult to face because we are programmed to desire certainty, to want to know what is happening around us, and to notice threatening people and/or situations.2 Uncertainty can lead us to feel stressed or overwhelmed due to a sense of losing control.2 Our mental and physical well-being can begin to deteriorate. We can feel more frazzled, angry, helpless, sad, frustrated, or confused,2 and we can become more isolated. These thoughts and feelings can make our daily activities more cumbersome.

To maintain our own mental and physical well-being, we must give ourselves permission to change the narrative from “the patient is always first” to “the patient always—but not always first.”3 Doing so will allow us to continue to help our patients.3 Despite the pervasive uncertainty, taking the following actions can help us to maintain our own mental and physical health.2-5

Minimize news that causes us to feel worse. COVID-19 news dominates the headlines. The near-constant, ever-changing stream of reports can cause us to feel overwhelmed and stressed. We should get information only from trusted sources, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO, and do so only once or twice a day. We should seek out only facts, and not focus on rumors that could worsen our thoughts and feelings.

Social distancing does not mean social isolation. To reduce the spread of COVID-19, social distancing has become necessary, but we should not completely avoid each other. We can still communicate with others via texting, e-mail, social media, video conferences, and phone calls. Despite not being able to engage in socially accepted physical greetings such as handshakes or hugs, we should not hesitate to verbally greet each other, albeit from a distance. In addition, we can still go outside while maintaining a safe distance from each other.

Keep a routine. Because we are creatures of habit, a routine (even a new one) can help sustain our mental and physical well-being. We should continue to:

- remain active at our usual times

- get adequate sleep and rest

- eat nutritious food

- engage in physical activity

- maintain contact with our family and friends

- continue treatments for any physical and/or mental conditions.

Avoid unhealthy coping strategies, such as binge-watching TV shows, because these can worsen psychological and physical well-being. You are likely to know what to do to “de-stress” yourself, and you should not hesitate to keep yourself psychologically and physically fit. Continue to engage in CDC-recommended hygienic practices such as frequently washing your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, avoiding close contact with people who are sick, and staying at home when you are sick. Seek mental health and/or medical treatment as necessary.

Continue to: Put the uncertainty in perspective

Put the uncertainty in perspective. Hopefully, there will come a time when we will resume our normal lives. Until then, we should acknowledge the uncertainty without immediately reacting to the worries that it creates. It is important to take a step back and think before reacting. This involves challenging ourselves to stay in the present and resist projecting into the future. Use this time for self-care, reflection, and/or catching up on the “to-do list.” We should be kind to ourselves and those around us. As best we can, we should show empathy to others and try to help our friends, families, and colleagues who are having a difficult time managing this crisis.

Since early March 2020, when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the

COVID-19 has created uncertainty in our lives, both professionally and personally. This can be difficult to face because we are programmed to desire certainty, to want to know what is happening around us, and to notice threatening people and/or situations.2 Uncertainty can lead us to feel stressed or overwhelmed due to a sense of losing control.2 Our mental and physical well-being can begin to deteriorate. We can feel more frazzled, angry, helpless, sad, frustrated, or confused,2 and we can become more isolated. These thoughts and feelings can make our daily activities more cumbersome.

To maintain our own mental and physical well-being, we must give ourselves permission to change the narrative from “the patient is always first” to “the patient always—but not always first.”3 Doing so will allow us to continue to help our patients.3 Despite the pervasive uncertainty, taking the following actions can help us to maintain our own mental and physical health.2-5

Minimize news that causes us to feel worse. COVID-19 news dominates the headlines. The near-constant, ever-changing stream of reports can cause us to feel overwhelmed and stressed. We should get information only from trusted sources, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO, and do so only once or twice a day. We should seek out only facts, and not focus on rumors that could worsen our thoughts and feelings.

Social distancing does not mean social isolation. To reduce the spread of COVID-19, social distancing has become necessary, but we should not completely avoid each other. We can still communicate with others via texting, e-mail, social media, video conferences, and phone calls. Despite not being able to engage in socially accepted physical greetings such as handshakes or hugs, we should not hesitate to verbally greet each other, albeit from a distance. In addition, we can still go outside while maintaining a safe distance from each other.

Keep a routine. Because we are creatures of habit, a routine (even a new one) can help sustain our mental and physical well-being. We should continue to:

- remain active at our usual times

- get adequate sleep and rest

- eat nutritious food

- engage in physical activity

- maintain contact with our family and friends

- continue treatments for any physical and/or mental conditions.

Avoid unhealthy coping strategies, such as binge-watching TV shows, because these can worsen psychological and physical well-being. You are likely to know what to do to “de-stress” yourself, and you should not hesitate to keep yourself psychologically and physically fit. Continue to engage in CDC-recommended hygienic practices such as frequently washing your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, avoiding close contact with people who are sick, and staying at home when you are sick. Seek mental health and/or medical treatment as necessary.

Continue to: Put the uncertainty in perspective

Put the uncertainty in perspective. Hopefully, there will come a time when we will resume our normal lives. Until then, we should acknowledge the uncertainty without immediately reacting to the worries that it creates. It is important to take a step back and think before reacting. This involves challenging ourselves to stay in the present and resist projecting into the future. Use this time for self-care, reflection, and/or catching up on the “to-do list.” We should be kind to ourselves and those around us. As best we can, we should show empathy to others and try to help our friends, families, and colleagues who are having a difficult time managing this crisis.

1. Ghebreyesus TA. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

2. Marshall D. Taking care of your mental health in the face of uncertainty. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. https://afsp.org/taking-care-of-your-mental-health-in-the-face-of-uncertainty/. Published March 10, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

3. Unadkat S, Farquhar M. Doctors’ wellbeing: self-care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1150. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1150.

4. World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVD-19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf. Published March 18, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

5. Brewer K. Coronavirus: how to protect your mental health. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-51873799. Published March 16, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

1. Ghebreyesus TA. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

2. Marshall D. Taking care of your mental health in the face of uncertainty. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. https://afsp.org/taking-care-of-your-mental-health-in-the-face-of-uncertainty/. Published March 10, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

3. Unadkat S, Farquhar M. Doctors’ wellbeing: self-care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1150. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1150.

4. World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVD-19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf. Published March 18, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

5. Brewer K. Coronavirus: how to protect your mental health. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-51873799. Published March 16, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

Strategies for treating patients with health anxiety

Up to 20% of patients in medical settings experience health anxiety.1,2 In DSM-IV-TR, this condition was called hypochondriasis, and its core feature was having a preoccupation with fears or the idea that one has a serious disease based on a misinterpretation of ≥1 bodily signs or symptoms despite undergoing appropriate medical evaluation.3 In DSM-5, hypochondriasis was removed, and somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder were introduced.1 Approximately 75% of patients with a previous diagnosis of hypochondriasis meet the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder, and approximately 25% meet the criteria for illness anxiety disorder.1 In clinical practice, the less pejorative and more commonly used term for these conditions is “health anxiety.”

Patients with health anxiety can be challenging to treat because they persist in believing they have an illness despite appropriate medical evaluation. Clinicians’ responses to such patients can range from feeling the need to do more to alleviate their suffering to strongly disliking them. Although these patients can elicit negative countertransference, we should remember that their lives are being adversely affected due to the substantial functional impairment they experience from their health worries. As psychiatrists, we can help our patients with health anxiety by employing the following strategies.

Maintain constant communication with other clinicians who manage the patient’s medical complaints. A clear line of communication with other clinicians can help minimize inconsistent or conflicting messages and potentially reduce splitting. This also can allow other clinicians to air their concerns, and for you to emphasize to them that patients with health anxiety can have an actual medical disease.

Allow patients to discuss their symptoms without interrupting them. This will help them understand that you are listening to them and taking their worries seriously.2 Elicit further discussion by asking them about2:

- their perception of their health

- how frequently they worry about their health

- fears about what could happen

- triggers for their worries

- how seriously they feel other clinicians regard their concerns

- behaviors they use to subdue their worries

- avoidance behaviors

- the impact their worries have on their lives.

Assess patients for the presence of comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Treating these conditions can help reduce your patients’ health anxiety–related distress and impairment.

Acknowledge that your patients’ symptoms are real to them and genuinely experienced.2 By focusing on worry as the most important symptom and recognizing how discomforting and serious that worry can be, you can validate your patients’ feelings and increase their motivation for continuing treatment.2

Avoid reassuring patients that they are medically healthy, because any relief your patients gain from this can quickly fade, and their anxiety may worsen.2 Instead, acknowledge their concerns by saying, “It’s clear that you are worried about your health. We have ways of helping this, and this will not affect any other treatment you are receiving.”2 This could allow your patients to recognize that they have health anxiety without believing that their medical problems will be disregarded or dismissed.2

Explain to patients that their perceptions could be symptoms of anxiety instead of an actual medical illness, equating health anxiety to a false alarm.2 Ask patients to summarize any information you present to them, because misinterpreting health information is a core feature of health anxiety.2

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Tyrer P, Hague J, et al. Health anxiety. BMJ. 2019;364:I774. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I774.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Up to 20% of patients in medical settings experience health anxiety.1,2 In DSM-IV-TR, this condition was called hypochondriasis, and its core feature was having a preoccupation with fears or the idea that one has a serious disease based on a misinterpretation of ≥1 bodily signs or symptoms despite undergoing appropriate medical evaluation.3 In DSM-5, hypochondriasis was removed, and somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder were introduced.1 Approximately 75% of patients with a previous diagnosis of hypochondriasis meet the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder, and approximately 25% meet the criteria for illness anxiety disorder.1 In clinical practice, the less pejorative and more commonly used term for these conditions is “health anxiety.”

Patients with health anxiety can be challenging to treat because they persist in believing they have an illness despite appropriate medical evaluation. Clinicians’ responses to such patients can range from feeling the need to do more to alleviate their suffering to strongly disliking them. Although these patients can elicit negative countertransference, we should remember that their lives are being adversely affected due to the substantial functional impairment they experience from their health worries. As psychiatrists, we can help our patients with health anxiety by employing the following strategies.

Maintain constant communication with other clinicians who manage the patient’s medical complaints. A clear line of communication with other clinicians can help minimize inconsistent or conflicting messages and potentially reduce splitting. This also can allow other clinicians to air their concerns, and for you to emphasize to them that patients with health anxiety can have an actual medical disease.

Allow patients to discuss their symptoms without interrupting them. This will help them understand that you are listening to them and taking their worries seriously.2 Elicit further discussion by asking them about2:

- their perception of their health

- how frequently they worry about their health

- fears about what could happen

- triggers for their worries

- how seriously they feel other clinicians regard their concerns

- behaviors they use to subdue their worries

- avoidance behaviors

- the impact their worries have on their lives.

Assess patients for the presence of comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Treating these conditions can help reduce your patients’ health anxiety–related distress and impairment.

Acknowledge that your patients’ symptoms are real to them and genuinely experienced.2 By focusing on worry as the most important symptom and recognizing how discomforting and serious that worry can be, you can validate your patients’ feelings and increase their motivation for continuing treatment.2

Avoid reassuring patients that they are medically healthy, because any relief your patients gain from this can quickly fade, and their anxiety may worsen.2 Instead, acknowledge their concerns by saying, “It’s clear that you are worried about your health. We have ways of helping this, and this will not affect any other treatment you are receiving.”2 This could allow your patients to recognize that they have health anxiety without believing that their medical problems will be disregarded or dismissed.2

Explain to patients that their perceptions could be symptoms of anxiety instead of an actual medical illness, equating health anxiety to a false alarm.2 Ask patients to summarize any information you present to them, because misinterpreting health information is a core feature of health anxiety.2

Up to 20% of patients in medical settings experience health anxiety.1,2 In DSM-IV-TR, this condition was called hypochondriasis, and its core feature was having a preoccupation with fears or the idea that one has a serious disease based on a misinterpretation of ≥1 bodily signs or symptoms despite undergoing appropriate medical evaluation.3 In DSM-5, hypochondriasis was removed, and somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder were introduced.1 Approximately 75% of patients with a previous diagnosis of hypochondriasis meet the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder, and approximately 25% meet the criteria for illness anxiety disorder.1 In clinical practice, the less pejorative and more commonly used term for these conditions is “health anxiety.”

Patients with health anxiety can be challenging to treat because they persist in believing they have an illness despite appropriate medical evaluation. Clinicians’ responses to such patients can range from feeling the need to do more to alleviate their suffering to strongly disliking them. Although these patients can elicit negative countertransference, we should remember that their lives are being adversely affected due to the substantial functional impairment they experience from their health worries. As psychiatrists, we can help our patients with health anxiety by employing the following strategies.

Maintain constant communication with other clinicians who manage the patient’s medical complaints. A clear line of communication with other clinicians can help minimize inconsistent or conflicting messages and potentially reduce splitting. This also can allow other clinicians to air their concerns, and for you to emphasize to them that patients with health anxiety can have an actual medical disease.

Allow patients to discuss their symptoms without interrupting them. This will help them understand that you are listening to them and taking their worries seriously.2 Elicit further discussion by asking them about2:

- their perception of their health

- how frequently they worry about their health

- fears about what could happen

- triggers for their worries

- how seriously they feel other clinicians regard their concerns

- behaviors they use to subdue their worries

- avoidance behaviors

- the impact their worries have on their lives.

Assess patients for the presence of comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Treating these conditions can help reduce your patients’ health anxiety–related distress and impairment.

Acknowledge that your patients’ symptoms are real to them and genuinely experienced.2 By focusing on worry as the most important symptom and recognizing how discomforting and serious that worry can be, you can validate your patients’ feelings and increase their motivation for continuing treatment.2

Avoid reassuring patients that they are medically healthy, because any relief your patients gain from this can quickly fade, and their anxiety may worsen.2 Instead, acknowledge their concerns by saying, “It’s clear that you are worried about your health. We have ways of helping this, and this will not affect any other treatment you are receiving.”2 This could allow your patients to recognize that they have health anxiety without believing that their medical problems will be disregarded or dismissed.2

Explain to patients that their perceptions could be symptoms of anxiety instead of an actual medical illness, equating health anxiety to a false alarm.2 Ask patients to summarize any information you present to them, because misinterpreting health information is a core feature of health anxiety.2

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Tyrer P, Hague J, et al. Health anxiety. BMJ. 2019;364:I774. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I774.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Tyrer P, Hague J, et al. Health anxiety. BMJ. 2019;364:I774. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I774.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

The ABCDs of treating tardive dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia (TD)—involuntary movement persisting for >1 month—is often caused by exposure to dopamine receptor–blocking agents such as antipsychotics.1 The pathophysiology of TD is attributed to dopamine receptor hypersensitivity and upregulation of dopamine receptors in response to chronic receptor blockade, although striatal dysfunction, oxidative stress, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) dysfunction may play a role.1 Because discontinuing the antipsychotic may not improve the patient’s TD symptoms and may worsen mood or psychosis, clinicians often prescribe adjunctive agents to reduce TD symptoms while continuing the antipsychotic. Clinicians can use the mnemonic ABCD to help recall 4 evidence-based treatments for TD.

Amantadine is an N-methyl-

Ginkgo Biloba contains antioxidant properties that may help reduce TD symptoms by alleviating oxidative stress. In a meta-analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials from China (N = 299), ginkgo biloba extract, 240 mg/d, significantly improved symptoms of TD compared with placebo.3 Ginkgo biloba has an antiplatelet effect and therefore should not be used in patients with an increased bleeding risk.

Clonazepam. Several small studies have examined the use of this GABA agonist for TD. In a study of 19 patients with TD, researchers found a symptom reduction of up to 35% with doses up to 4.5 mg/d.4 However, many studies have had small sample sizes or poor methodology. A 2018 Cochrane review recommended using other agents before considering clonazepam for TD because this medication has uncertain efficacy in treating TD, and it can cause sedation and dependence.5

Deutetrabenazine and valbenazine, the only FDA-approved treatments for TD, are vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors, which inhibit dopamine release and decrease dopamine receptor hypersensitivity.6 In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 117 patients with moderate-to-severe TD, those who received deutetrabenazine (up to 48 mg/d) had a significant mean reduction in AIMS score (3 points) compared with placebo.7 In the 1-year KINECT 3 study, 124 patients with TD who received valbenazine, 40 or 80 mg/d, had significant mean reductions in AIMS scores of 3.0 and 4.8 points, respectively.8 Adverse effects of these medications include somnolence, headache, akathisia, urinary tract infection, worsening mood, and suicidality. Tetrabenazine is another VMAT2 inhibitor that may be effective in doses up to 150 mg/d, but its off-label use is limited by the need for frequent dosing and a risk for suicidality.6

Other adjunctive treatments, such as vitamin B6, vitamin E, zonisamide, and levetiracetam, might offer some benefit in TD.6 However, further evidence is needed to support including these interventions in treatment guidelines.

1. Elkurd MT, Bahroo L. Keeping up with the clinical advances: tardive dyskinesia. CNS Spectr. 2019;24(suppl 1):70-81.

2. Pappa S, Tsouli S, Apostolu G, et al. Effects of amantadine on tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):271-275.

3. Zheng W, Xiang YQ, Ng CH, et al. Extract of ginkgo biloba for tardive dyskinesia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2016;49(3):107-111.

4. Thaker GK, Nguyen JA, Strauss ME, et al. Clonazepam treatment of tardive dyskinesia: a practical GABAmimetic strategy. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(4):445-451.

5. Bergman H, Bhoopathi PS, Soares-Weiser K. Benzodiazepines for antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD000205.

6. Sreeram V, Shagufta S, Kagadkar F. Role of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors in tardive dyskinesia management. Cureus. 2019;11(8):e5471. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5471.

7. Fernandez HH, Factor SA, Hauser RA. Randomized controlled trial of deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia. The ARM-TD study. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2003-2010.

8. Factor SA, Remington G, Comella CL, et al. The effects of valbenazine in participants with tardive dyskinesia: results of the 1-year KINECT 3 extension study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(9):1344-1350.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD)—involuntary movement persisting for >1 month—is often caused by exposure to dopamine receptor–blocking agents such as antipsychotics.1 The pathophysiology of TD is attributed to dopamine receptor hypersensitivity and upregulation of dopamine receptors in response to chronic receptor blockade, although striatal dysfunction, oxidative stress, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) dysfunction may play a role.1 Because discontinuing the antipsychotic may not improve the patient’s TD symptoms and may worsen mood or psychosis, clinicians often prescribe adjunctive agents to reduce TD symptoms while continuing the antipsychotic. Clinicians can use the mnemonic ABCD to help recall 4 evidence-based treatments for TD.

Amantadine is an N-methyl-

Ginkgo Biloba contains antioxidant properties that may help reduce TD symptoms by alleviating oxidative stress. In a meta-analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials from China (N = 299), ginkgo biloba extract, 240 mg/d, significantly improved symptoms of TD compared with placebo.3 Ginkgo biloba has an antiplatelet effect and therefore should not be used in patients with an increased bleeding risk.

Clonazepam. Several small studies have examined the use of this GABA agonist for TD. In a study of 19 patients with TD, researchers found a symptom reduction of up to 35% with doses up to 4.5 mg/d.4 However, many studies have had small sample sizes or poor methodology. A 2018 Cochrane review recommended using other agents before considering clonazepam for TD because this medication has uncertain efficacy in treating TD, and it can cause sedation and dependence.5

Deutetrabenazine and valbenazine, the only FDA-approved treatments for TD, are vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors, which inhibit dopamine release and decrease dopamine receptor hypersensitivity.6 In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 117 patients with moderate-to-severe TD, those who received deutetrabenazine (up to 48 mg/d) had a significant mean reduction in AIMS score (3 points) compared with placebo.7 In the 1-year KINECT 3 study, 124 patients with TD who received valbenazine, 40 or 80 mg/d, had significant mean reductions in AIMS scores of 3.0 and 4.8 points, respectively.8 Adverse effects of these medications include somnolence, headache, akathisia, urinary tract infection, worsening mood, and suicidality. Tetrabenazine is another VMAT2 inhibitor that may be effective in doses up to 150 mg/d, but its off-label use is limited by the need for frequent dosing and a risk for suicidality.6

Other adjunctive treatments, such as vitamin B6, vitamin E, zonisamide, and levetiracetam, might offer some benefit in TD.6 However, further evidence is needed to support including these interventions in treatment guidelines.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD)—involuntary movement persisting for >1 month—is often caused by exposure to dopamine receptor–blocking agents such as antipsychotics.1 The pathophysiology of TD is attributed to dopamine receptor hypersensitivity and upregulation of dopamine receptors in response to chronic receptor blockade, although striatal dysfunction, oxidative stress, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) dysfunction may play a role.1 Because discontinuing the antipsychotic may not improve the patient’s TD symptoms and may worsen mood or psychosis, clinicians often prescribe adjunctive agents to reduce TD symptoms while continuing the antipsychotic. Clinicians can use the mnemonic ABCD to help recall 4 evidence-based treatments for TD.

Amantadine is an N-methyl-

Ginkgo Biloba contains antioxidant properties that may help reduce TD symptoms by alleviating oxidative stress. In a meta-analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials from China (N = 299), ginkgo biloba extract, 240 mg/d, significantly improved symptoms of TD compared with placebo.3 Ginkgo biloba has an antiplatelet effect and therefore should not be used in patients with an increased bleeding risk.