User login

Off-label prescribing: How to limit your liability

The FDA defines “off-label” prescribing as prescribing an FDA-approved medication for an unapproved use, such as for an unapproved clinical indication, for a higher-than-approved dose, or for a patient who is not part of the FDA-approved population (eg, children or geriatric patients).1 Off-label prescribing is common in psychiatry; approximately 13% of psychiatry patients are prescribed off-label psychotropic medications.2 The American Psychiatric Association strongly supports “the autonomous clinical decision-making authority of a physician” and “a physician’s lawful use of an FDA-approved drug product or medical device for an off-label indication when such use is based upon sound scientific evidence in conjunction with sound medical judgment.”3 Because many psychiatric diagnoses have no FDA-approved medications, off-label prescribing often may be a psychiatrist’s only pharmacologic option.

Unfortunately, off-label prescribing can increase a psychiatrist’s risk for liability when treatment falls short of patients’ expectations, or when patients allege that they were injured by the use of an off-label medication. Off-label prescribing does not automatically lead to losing a malpractice suit because the FDA states that physicians can prescribe approved medications for any scientifically supported use, including off-label.1 Medical malpractice lawsuits alleging negligence in prescribing practices, such as off-label prescribing, typically include allegations against the psychiatrist for failure to4:

- adequately assess the patient

- consult the patient’s medical records

- obtain informed consent from the patient

- appropriately prescribe a medication for the clinical indication, dosage, patient’s age, etc.

- monitor for adverse effects and therapeutic effectiveness.

Steps to minimize your risk

When prescribing a medication off-label, the following approaches can help reduce your liability risk:

Conduct a comprehensive clinical assessment. This should include requesting and reviewing your patient’s medical records.

Explain your motivation. Explain to your patient how prescribing an off-label medication can directly benefit him/her. Make it clear that you are not conducting experimental research by prescribing off-label because some patients might perceive this as a covert form of research.

Know the medications you prescribe. Although this sounds obvious, psychiatrists should thoroughly understand how each medication they prescribe is likely to clinically affect their patient. This information is available from many sources, including the FDA’s medication information sheets and the manufacturer’s medication package inserts. If possible, make sure that your off-label prescribing is supported by reputable, peer-reviewed literature.

Obtain informed consent. Tell your patient that the medication you are recommending is being prescribed off-label. Discuss the medication’s risks, benefits, adverse effects, associated “black-box” warnings, off-label uses, and alternatives to the off-label medication.4 Allow time for the patient to ask questions about these treatments.

Continue to: Document all steps

Document all steps. There is an adage in medicine that “If it’s not written, it wasn’t done.” To help reduce your liability risk when prescribing off-label, be sure to document the following4:

- your clinical assessment

- information you gleaned from the patient’s medical records

- your review of information regarding both therapeutic and adverse effects of the medication you want to prescribe

- your discussion of informed consent, including documentation that the patient is aware that the medication is being prescribed off-label

- your clinical rationale for why the off-label medication is in the patient’s best interest.

Also, document the steps you take to monitor for adverse events and therapeutic effectiveness.4 Overall, the goal of documentation should be to support the adequate continuing care of our patients.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Understanding unapproved use of approved drugs “off label.” https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-expanded-access-and-other-treatment-options/understanding-unapproved-use-approved-drugs-label. Updated February 5, 2018. Accessed August 6, 2020.

2. Vijay A, Becker JE, Ross JS. Patterns and predictors of off-label prescription of psychiatric drugs. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0198363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198363.

3. McLeer S, Mawhinney J; Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing. Position statement on off-label treatments. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-2016-Off-Label-Treatment.pdf. Published July 2016. Accessed August 6, 2020.

4. Funicelli A. What to consider when prescribing off-label. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(14):12.

The FDA defines “off-label” prescribing as prescribing an FDA-approved medication for an unapproved use, such as for an unapproved clinical indication, for a higher-than-approved dose, or for a patient who is not part of the FDA-approved population (eg, children or geriatric patients).1 Off-label prescribing is common in psychiatry; approximately 13% of psychiatry patients are prescribed off-label psychotropic medications.2 The American Psychiatric Association strongly supports “the autonomous clinical decision-making authority of a physician” and “a physician’s lawful use of an FDA-approved drug product or medical device for an off-label indication when such use is based upon sound scientific evidence in conjunction with sound medical judgment.”3 Because many psychiatric diagnoses have no FDA-approved medications, off-label prescribing often may be a psychiatrist’s only pharmacologic option.

Unfortunately, off-label prescribing can increase a psychiatrist’s risk for liability when treatment falls short of patients’ expectations, or when patients allege that they were injured by the use of an off-label medication. Off-label prescribing does not automatically lead to losing a malpractice suit because the FDA states that physicians can prescribe approved medications for any scientifically supported use, including off-label.1 Medical malpractice lawsuits alleging negligence in prescribing practices, such as off-label prescribing, typically include allegations against the psychiatrist for failure to4:

- adequately assess the patient

- consult the patient’s medical records

- obtain informed consent from the patient

- appropriately prescribe a medication for the clinical indication, dosage, patient’s age, etc.

- monitor for adverse effects and therapeutic effectiveness.

Steps to minimize your risk

When prescribing a medication off-label, the following approaches can help reduce your liability risk:

Conduct a comprehensive clinical assessment. This should include requesting and reviewing your patient’s medical records.

Explain your motivation. Explain to your patient how prescribing an off-label medication can directly benefit him/her. Make it clear that you are not conducting experimental research by prescribing off-label because some patients might perceive this as a covert form of research.

Know the medications you prescribe. Although this sounds obvious, psychiatrists should thoroughly understand how each medication they prescribe is likely to clinically affect their patient. This information is available from many sources, including the FDA’s medication information sheets and the manufacturer’s medication package inserts. If possible, make sure that your off-label prescribing is supported by reputable, peer-reviewed literature.

Obtain informed consent. Tell your patient that the medication you are recommending is being prescribed off-label. Discuss the medication’s risks, benefits, adverse effects, associated “black-box” warnings, off-label uses, and alternatives to the off-label medication.4 Allow time for the patient to ask questions about these treatments.

Continue to: Document all steps

Document all steps. There is an adage in medicine that “If it’s not written, it wasn’t done.” To help reduce your liability risk when prescribing off-label, be sure to document the following4:

- your clinical assessment

- information you gleaned from the patient’s medical records

- your review of information regarding both therapeutic and adverse effects of the medication you want to prescribe

- your discussion of informed consent, including documentation that the patient is aware that the medication is being prescribed off-label

- your clinical rationale for why the off-label medication is in the patient’s best interest.

Also, document the steps you take to monitor for adverse events and therapeutic effectiveness.4 Overall, the goal of documentation should be to support the adequate continuing care of our patients.

The FDA defines “off-label” prescribing as prescribing an FDA-approved medication for an unapproved use, such as for an unapproved clinical indication, for a higher-than-approved dose, or for a patient who is not part of the FDA-approved population (eg, children or geriatric patients).1 Off-label prescribing is common in psychiatry; approximately 13% of psychiatry patients are prescribed off-label psychotropic medications.2 The American Psychiatric Association strongly supports “the autonomous clinical decision-making authority of a physician” and “a physician’s lawful use of an FDA-approved drug product or medical device for an off-label indication when such use is based upon sound scientific evidence in conjunction with sound medical judgment.”3 Because many psychiatric diagnoses have no FDA-approved medications, off-label prescribing often may be a psychiatrist’s only pharmacologic option.

Unfortunately, off-label prescribing can increase a psychiatrist’s risk for liability when treatment falls short of patients’ expectations, or when patients allege that they were injured by the use of an off-label medication. Off-label prescribing does not automatically lead to losing a malpractice suit because the FDA states that physicians can prescribe approved medications for any scientifically supported use, including off-label.1 Medical malpractice lawsuits alleging negligence in prescribing practices, such as off-label prescribing, typically include allegations against the psychiatrist for failure to4:

- adequately assess the patient

- consult the patient’s medical records

- obtain informed consent from the patient

- appropriately prescribe a medication for the clinical indication, dosage, patient’s age, etc.

- monitor for adverse effects and therapeutic effectiveness.

Steps to minimize your risk

When prescribing a medication off-label, the following approaches can help reduce your liability risk:

Conduct a comprehensive clinical assessment. This should include requesting and reviewing your patient’s medical records.

Explain your motivation. Explain to your patient how prescribing an off-label medication can directly benefit him/her. Make it clear that you are not conducting experimental research by prescribing off-label because some patients might perceive this as a covert form of research.

Know the medications you prescribe. Although this sounds obvious, psychiatrists should thoroughly understand how each medication they prescribe is likely to clinically affect their patient. This information is available from many sources, including the FDA’s medication information sheets and the manufacturer’s medication package inserts. If possible, make sure that your off-label prescribing is supported by reputable, peer-reviewed literature.

Obtain informed consent. Tell your patient that the medication you are recommending is being prescribed off-label. Discuss the medication’s risks, benefits, adverse effects, associated “black-box” warnings, off-label uses, and alternatives to the off-label medication.4 Allow time for the patient to ask questions about these treatments.

Continue to: Document all steps

Document all steps. There is an adage in medicine that “If it’s not written, it wasn’t done.” To help reduce your liability risk when prescribing off-label, be sure to document the following4:

- your clinical assessment

- information you gleaned from the patient’s medical records

- your review of information regarding both therapeutic and adverse effects of the medication you want to prescribe

- your discussion of informed consent, including documentation that the patient is aware that the medication is being prescribed off-label

- your clinical rationale for why the off-label medication is in the patient’s best interest.

Also, document the steps you take to monitor for adverse events and therapeutic effectiveness.4 Overall, the goal of documentation should be to support the adequate continuing care of our patients.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Understanding unapproved use of approved drugs “off label.” https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-expanded-access-and-other-treatment-options/understanding-unapproved-use-approved-drugs-label. Updated February 5, 2018. Accessed August 6, 2020.

2. Vijay A, Becker JE, Ross JS. Patterns and predictors of off-label prescription of psychiatric drugs. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0198363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198363.

3. McLeer S, Mawhinney J; Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing. Position statement on off-label treatments. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-2016-Off-Label-Treatment.pdf. Published July 2016. Accessed August 6, 2020.

4. Funicelli A. What to consider when prescribing off-label. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(14):12.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Understanding unapproved use of approved drugs “off label.” https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-expanded-access-and-other-treatment-options/understanding-unapproved-use-approved-drugs-label. Updated February 5, 2018. Accessed August 6, 2020.

2. Vijay A, Becker JE, Ross JS. Patterns and predictors of off-label prescription of psychiatric drugs. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0198363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198363.

3. McLeer S, Mawhinney J; Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing. Position statement on off-label treatments. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-2016-Off-Label-Treatment.pdf. Published July 2016. Accessed August 6, 2020.

4. Funicelli A. What to consider when prescribing off-label. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(14):12.

Psychiatric emergency? What to consider before prescribing

Psychiatric emergencies—such as a patient who is agitated, self-destructive, or suicidal—may arise in a variety of settings, including emergency departments and inpatient units.1 Before emergently prescribing psychotropic medications to address acute psychiatric symptoms, there are numerous factors a clinician needs to consider.1-3 Asking the following questions may help you quickly obtain important clinical information to determine which medication to use during a psychiatric emergency:

Age. Is the patient a child, adolescent, adult, or older adult?

Allergies. Does the patient have any medication allergies or sensitivities?

Behaviors. What are the imminent dangerous behaviors that warrant emergent medication use

Collateral information. If the patient was brought by police or family, how was he/she behaving in the community or at home? If brought from a correctional facility or other institution, how did he/she behave in that setting?

Concurrent diagnoses/interventions. Does the patient have a psychiatric or medical diagnosis? Is the patient receiving any pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic treatments?

First visit. Is this the patient’s first visit to your facility? Or has the patient been to the facility previously and/or repeatedly? Has the patient ever been prescribed psychotropic medications? If the patient has received emergent medications before, which medications were used, and were they helpful?

Continue to: Legal status

Legal status. Is the patient voluntary for treatment or involuntary for treatment? If voluntary, is involuntary treatment needed?

Street. Was this patient evaluated in a medical setting before presenting to your facility? Or did this patient arrive directly from the community/street?

Substance use. Has the patient been using any licit and/or illicit substances?

In my experience with psychiatric emergencies, asking these questions has helped guide my decision-making during these situations. They have helped me to determine the appropriate medication, route of administration, dose, and monitoring requirements. Although other factors can impact clinicians’ decision-making in these situations, I have found these questions to be a good starting point.

1. Mavrogiorgou P, Brüne M, Juckel G. The management of psychiatric emergencies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(13):222-230.

2. Glick RL, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al (eds). Emergency psychiatry: principles and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolter Kluwer; 2020.

3. Garriga M, Pacchiarotti I, Kasper S, et al. Assessment and management of agitation in psychiatry: expert consensus. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17(2):86-128.

Psychiatric emergencies—such as a patient who is agitated, self-destructive, or suicidal—may arise in a variety of settings, including emergency departments and inpatient units.1 Before emergently prescribing psychotropic medications to address acute psychiatric symptoms, there are numerous factors a clinician needs to consider.1-3 Asking the following questions may help you quickly obtain important clinical information to determine which medication to use during a psychiatric emergency:

Age. Is the patient a child, adolescent, adult, or older adult?

Allergies. Does the patient have any medication allergies or sensitivities?

Behaviors. What are the imminent dangerous behaviors that warrant emergent medication use

Collateral information. If the patient was brought by police or family, how was he/she behaving in the community or at home? If brought from a correctional facility or other institution, how did he/she behave in that setting?

Concurrent diagnoses/interventions. Does the patient have a psychiatric or medical diagnosis? Is the patient receiving any pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic treatments?

First visit. Is this the patient’s first visit to your facility? Or has the patient been to the facility previously and/or repeatedly? Has the patient ever been prescribed psychotropic medications? If the patient has received emergent medications before, which medications were used, and were they helpful?

Continue to: Legal status

Legal status. Is the patient voluntary for treatment or involuntary for treatment? If voluntary, is involuntary treatment needed?

Street. Was this patient evaluated in a medical setting before presenting to your facility? Or did this patient arrive directly from the community/street?

Substance use. Has the patient been using any licit and/or illicit substances?

In my experience with psychiatric emergencies, asking these questions has helped guide my decision-making during these situations. They have helped me to determine the appropriate medication, route of administration, dose, and monitoring requirements. Although other factors can impact clinicians’ decision-making in these situations, I have found these questions to be a good starting point.

Psychiatric emergencies—such as a patient who is agitated, self-destructive, or suicidal—may arise in a variety of settings, including emergency departments and inpatient units.1 Before emergently prescribing psychotropic medications to address acute psychiatric symptoms, there are numerous factors a clinician needs to consider.1-3 Asking the following questions may help you quickly obtain important clinical information to determine which medication to use during a psychiatric emergency:

Age. Is the patient a child, adolescent, adult, or older adult?

Allergies. Does the patient have any medication allergies or sensitivities?

Behaviors. What are the imminent dangerous behaviors that warrant emergent medication use

Collateral information. If the patient was brought by police or family, how was he/she behaving in the community or at home? If brought from a correctional facility or other institution, how did he/she behave in that setting?

Concurrent diagnoses/interventions. Does the patient have a psychiatric or medical diagnosis? Is the patient receiving any pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic treatments?

First visit. Is this the patient’s first visit to your facility? Or has the patient been to the facility previously and/or repeatedly? Has the patient ever been prescribed psychotropic medications? If the patient has received emergent medications before, which medications were used, and were they helpful?

Continue to: Legal status

Legal status. Is the patient voluntary for treatment or involuntary for treatment? If voluntary, is involuntary treatment needed?

Street. Was this patient evaluated in a medical setting before presenting to your facility? Or did this patient arrive directly from the community/street?

Substance use. Has the patient been using any licit and/or illicit substances?

In my experience with psychiatric emergencies, asking these questions has helped guide my decision-making during these situations. They have helped me to determine the appropriate medication, route of administration, dose, and monitoring requirements. Although other factors can impact clinicians’ decision-making in these situations, I have found these questions to be a good starting point.

1. Mavrogiorgou P, Brüne M, Juckel G. The management of psychiatric emergencies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(13):222-230.

2. Glick RL, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al (eds). Emergency psychiatry: principles and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolter Kluwer; 2020.

3. Garriga M, Pacchiarotti I, Kasper S, et al. Assessment and management of agitation in psychiatry: expert consensus. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17(2):86-128.

1. Mavrogiorgou P, Brüne M, Juckel G. The management of psychiatric emergencies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(13):222-230.

2. Glick RL, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al (eds). Emergency psychiatry: principles and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolter Kluwer; 2020.

3. Garriga M, Pacchiarotti I, Kasper S, et al. Assessment and management of agitation in psychiatry: expert consensus. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17(2):86-128.

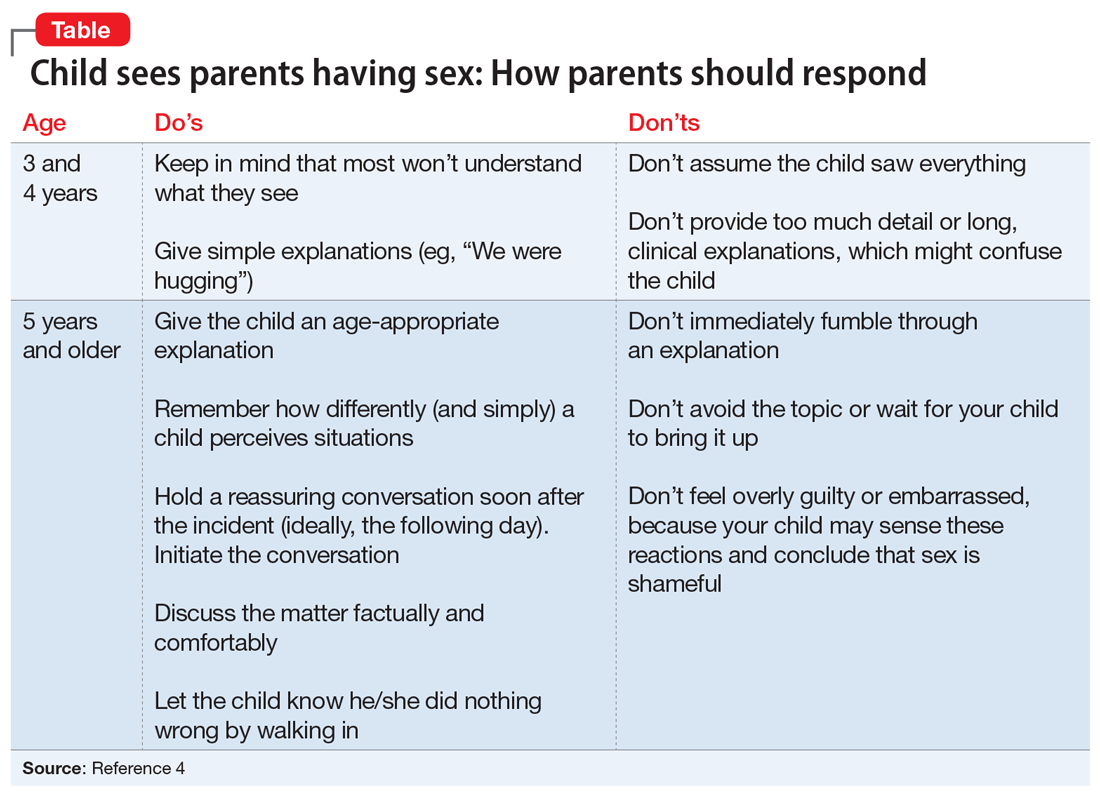

What to tell parents whose child saw them having sex

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.

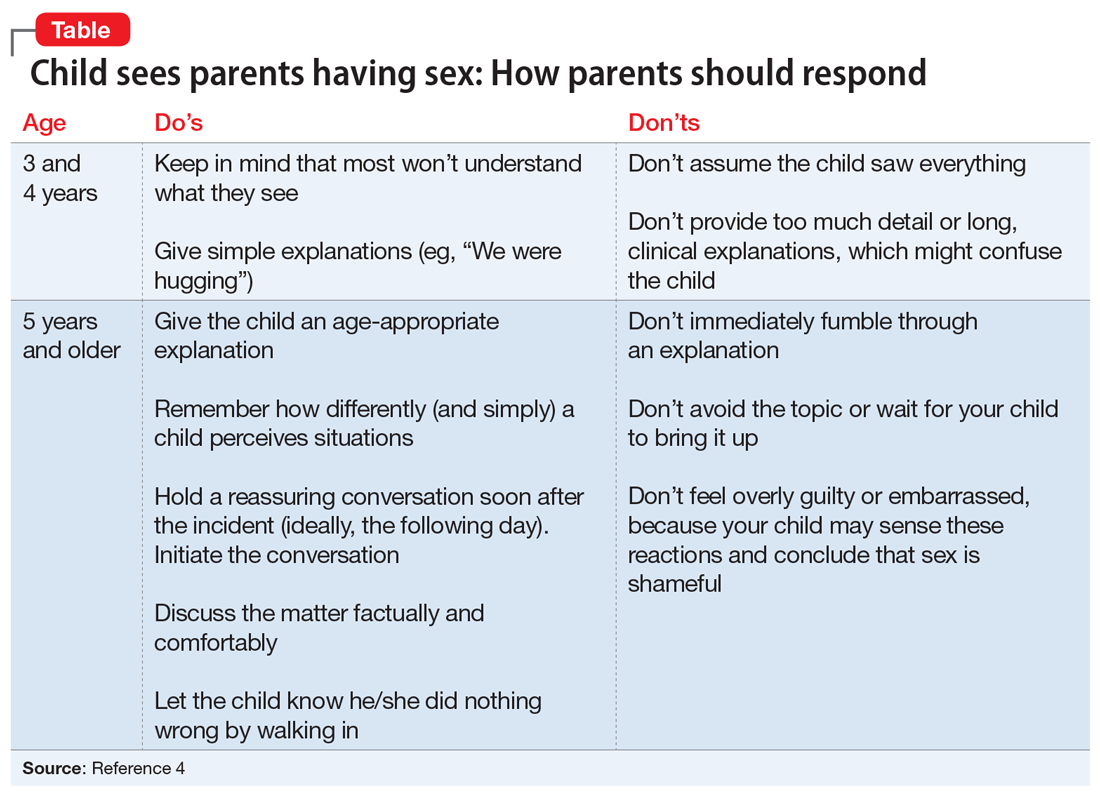

Discuss what happened. Tell parents to explore their child’s impression of what he/she saw. Tailoring the discussion to the child’s age is important. For example, a 3-year-old might wonder if anyone was harmed, and might need reassurance, whereas a 12-year-old is likely to have a better understanding of sex but still feel uncomfortable. Educational conversations about sexuality might be appropriate for children age 8 to 12. The parents’ goal should be to answer questions honestly without oversharing, and to leave the door open—so to speak—for future conversations.

Recommend that parents use plain, factual language to answer any questions their child asks. Statements such as “We were having a private, adult moment” can be helpful. Parents can categorize sex as a universal activity that is not harmful or scary by telling their child something such as, “This is what all parents do.” Parents should avoid providing unnecessary information or answering questions their child is not asking. The Table4 offers guidance on how parents might handle such conversations.

Consider potentially positive outcomes. Although parents may feel guilty or describe this as a terrible situation, remind them that there are some potentially healthy outcomes. For example, such incidents may help reassure the child that their parents love each other, which might give him/her a sense of happiness and security.

Take steps to prevent this from happening again. Advise parents to lock the door when having sex. Remind them to consider the proximity of rooms because their child might hear noises and become curious.

1. Blum HP. On the concept and consequences of the primal scene. Psychoanal Q. 1979;48(1):27-47.

2. Hoyt MF. On the psychology and psychopathology of primal-scene experience. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1980;8(3):311-335.

3. Ikonen P, Rechardt E. On the universal nature of primal scene fantasies. Int J Psychoanal. 1984;65(pt 1):63-72.

4. Pelly J. Four things my four-year-old already knows about sex. Today’s Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/4-things-my-4-year-old-already-knows-about-sex/. Published February 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.

Discuss what happened. Tell parents to explore their child’s impression of what he/she saw. Tailoring the discussion to the child’s age is important. For example, a 3-year-old might wonder if anyone was harmed, and might need reassurance, whereas a 12-year-old is likely to have a better understanding of sex but still feel uncomfortable. Educational conversations about sexuality might be appropriate for children age 8 to 12. The parents’ goal should be to answer questions honestly without oversharing, and to leave the door open—so to speak—for future conversations.

Recommend that parents use plain, factual language to answer any questions their child asks. Statements such as “We were having a private, adult moment” can be helpful. Parents can categorize sex as a universal activity that is not harmful or scary by telling their child something such as, “This is what all parents do.” Parents should avoid providing unnecessary information or answering questions their child is not asking. The Table4 offers guidance on how parents might handle such conversations.

Consider potentially positive outcomes. Although parents may feel guilty or describe this as a terrible situation, remind them that there are some potentially healthy outcomes. For example, such incidents may help reassure the child that their parents love each other, which might give him/her a sense of happiness and security.

Take steps to prevent this from happening again. Advise parents to lock the door when having sex. Remind them to consider the proximity of rooms because their child might hear noises and become curious.

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.

Discuss what happened. Tell parents to explore their child’s impression of what he/she saw. Tailoring the discussion to the child’s age is important. For example, a 3-year-old might wonder if anyone was harmed, and might need reassurance, whereas a 12-year-old is likely to have a better understanding of sex but still feel uncomfortable. Educational conversations about sexuality might be appropriate for children age 8 to 12. The parents’ goal should be to answer questions honestly without oversharing, and to leave the door open—so to speak—for future conversations.

Recommend that parents use plain, factual language to answer any questions their child asks. Statements such as “We were having a private, adult moment” can be helpful. Parents can categorize sex as a universal activity that is not harmful or scary by telling their child something such as, “This is what all parents do.” Parents should avoid providing unnecessary information or answering questions their child is not asking. The Table4 offers guidance on how parents might handle such conversations.

Consider potentially positive outcomes. Although parents may feel guilty or describe this as a terrible situation, remind them that there are some potentially healthy outcomes. For example, such incidents may help reassure the child that their parents love each other, which might give him/her a sense of happiness and security.

Take steps to prevent this from happening again. Advise parents to lock the door when having sex. Remind them to consider the proximity of rooms because their child might hear noises and become curious.

1. Blum HP. On the concept and consequences of the primal scene. Psychoanal Q. 1979;48(1):27-47.

2. Hoyt MF. On the psychology and psychopathology of primal-scene experience. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1980;8(3):311-335.

3. Ikonen P, Rechardt E. On the universal nature of primal scene fantasies. Int J Psychoanal. 1984;65(pt 1):63-72.

4. Pelly J. Four things my four-year-old already knows about sex. Today’s Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/4-things-my-4-year-old-already-knows-about-sex/. Published February 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

1. Blum HP. On the concept and consequences of the primal scene. Psychoanal Q. 1979;48(1):27-47.

2. Hoyt MF. On the psychology and psychopathology of primal-scene experience. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1980;8(3):311-335.

3. Ikonen P, Rechardt E. On the universal nature of primal scene fantasies. Int J Psychoanal. 1984;65(pt 1):63-72.

4. Pelly J. Four things my four-year-old already knows about sex. Today’s Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/4-things-my-4-year-old-already-knows-about-sex/. Published February 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

Kleptomania: 4 Tips for better diagnosis and treatment

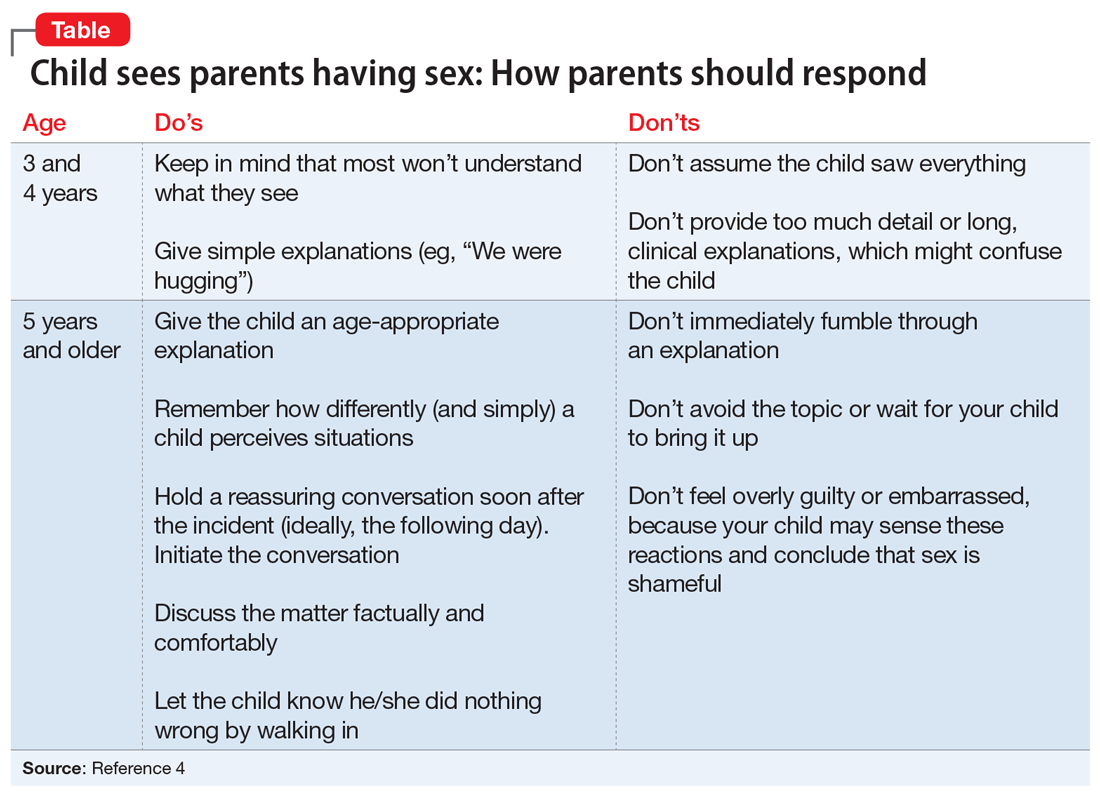

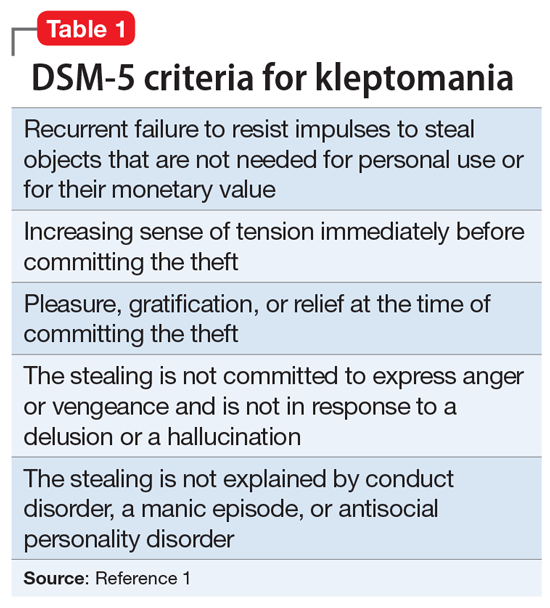

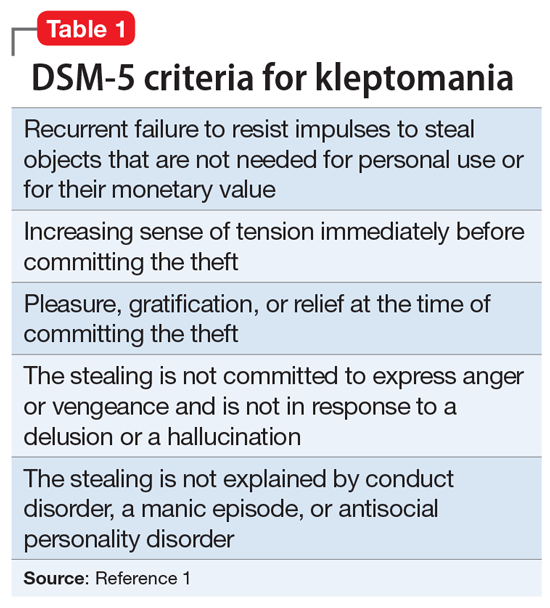

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

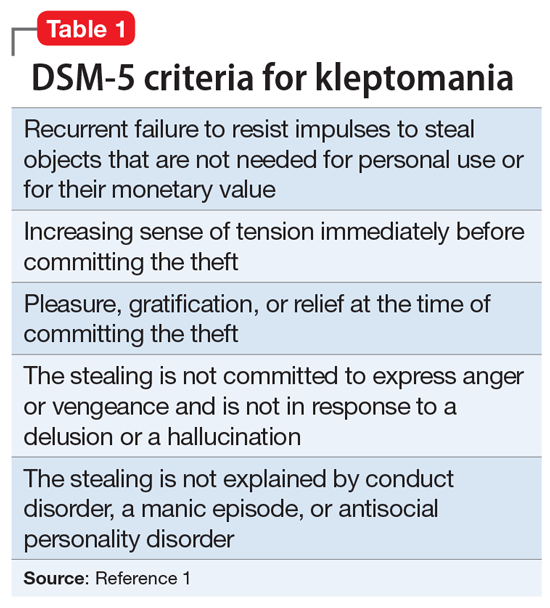

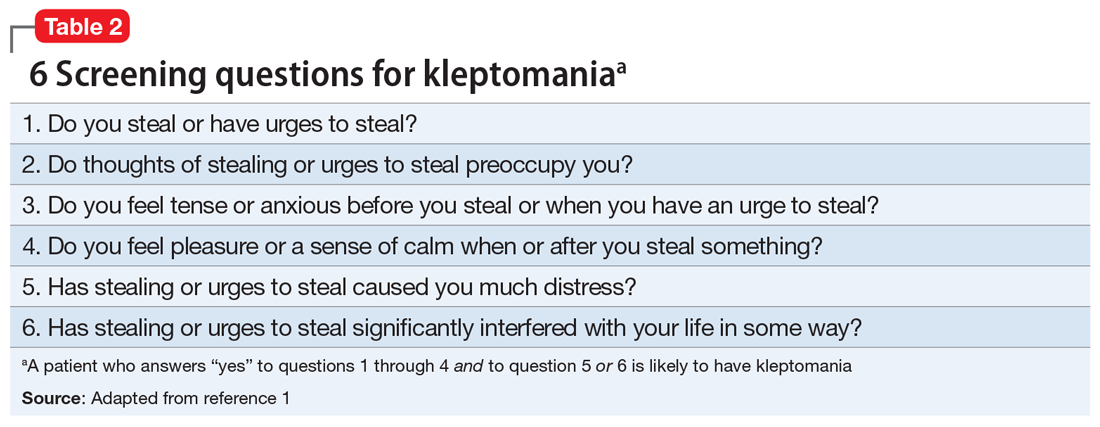

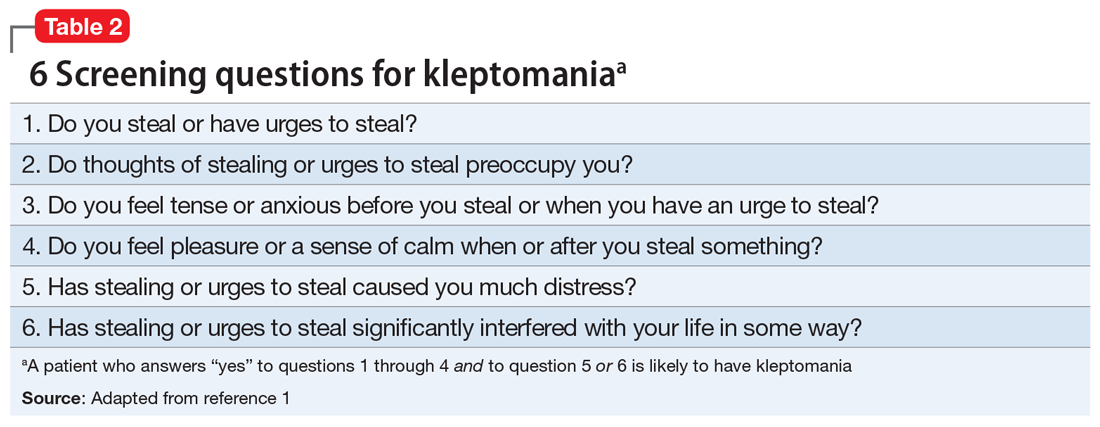

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

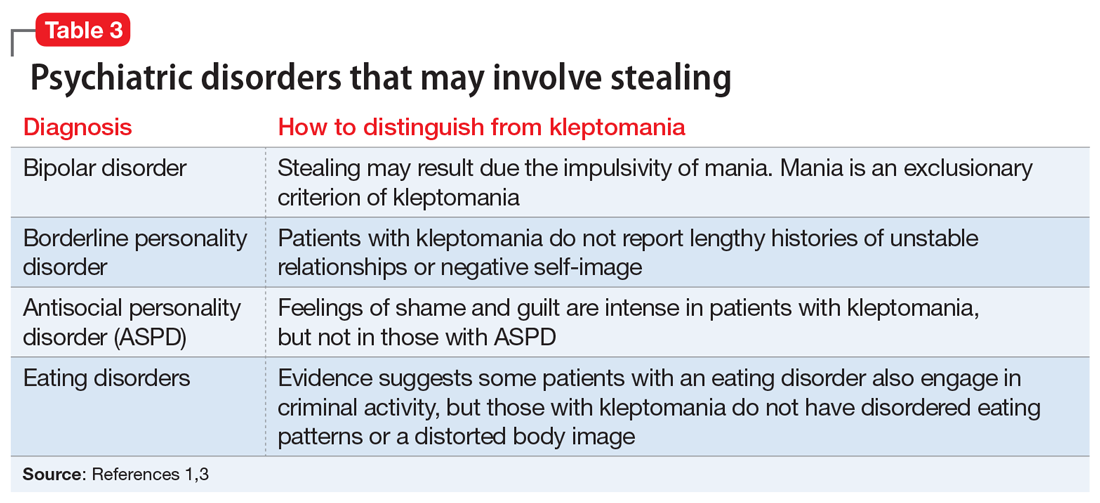

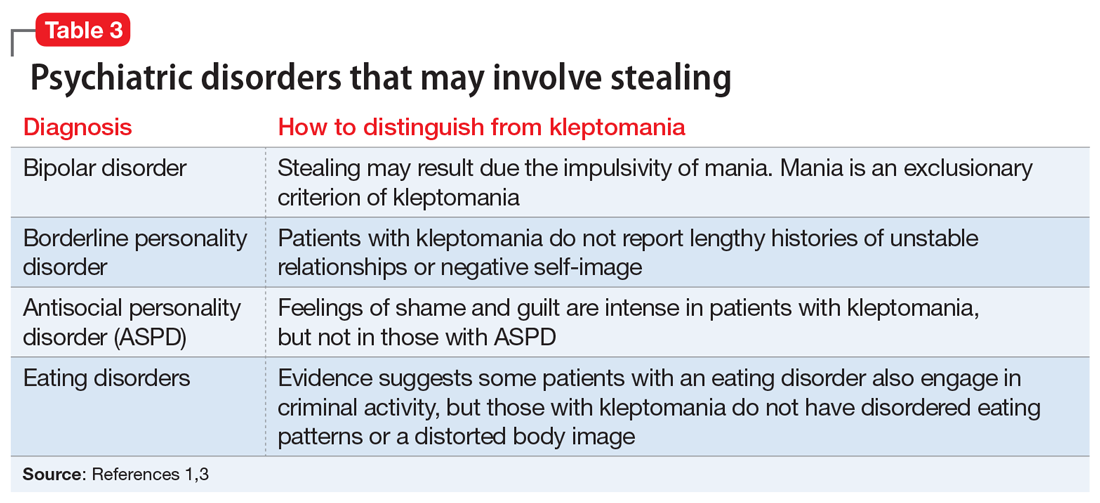

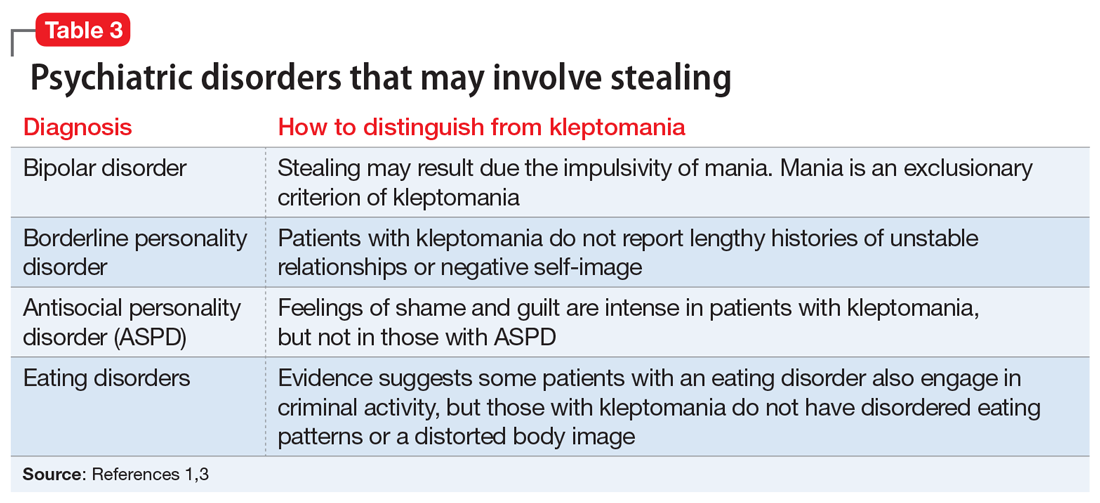

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

Improving your experience with electronic health records

The electronic health record (EHR) was introduced to improve how clinicians document patient information, contribute to medical research, and allow for medical records to be universally transferable.1 However, many clinicians find EHRs to be burdensome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Clinicians often spend multiple hours each day navigating their EHR system, which reduces the amount of time they spend interacting with patients and contributes to physician burnout.1-3 For example, in a study of 142 family medicine physicians, clinicians reported that they spent approximately 6 hours per work day interacting with their EHR.3

Clearly, the EHR needs a fundamental revision. In the meantime, how can we adapt to improve the situation? Here I suggest practical steps clinicians can take to improve their experience with their EHR system.4-8

Steps to take during patient visits

Because entering information into the EHR can be distracting, be prepared to multitask during each clinical encounter.1-7 Be ready to address pertinent inquiries and issues your patient raises, and provide instructions on therapies and interventions. Because interpersonal relations are important during clinical encounters, establish interaction with your patient by acknowledging them and maintaining frequent eye contact.7 Consider allowing your patient to view the EHR screen because doing so might increase his/her involvement in the visit.

So that you can pay closer attention to your patient, consider taking notes during the visit and entering the information into the EHR later. Consider improving your typing skills to increase the speed of your note-taking. Alternatively, using a voice-recognition recording tool to transcribe your notes via speech might help you spend less time on note-taking.3 Whenever possible, finish charting for one patient before meeting with the next because doing so will save time and help you to better remember details.7

In addition, lowering your overall stress might help reduce the burden of using the EHR.3-5 Adopt healthy behaviors, including good sleep, nutrition, exercise, and hobbies, and strive for balance in your routines. Attend to any personal medical or psychiatric conditions, and avoid misusing alcohol, medications, or other substances.

Optimize how your practice functions

With your clinical group and colleagues, create a comfortable environment, good patient-to-doctor interactions, and a smooth flow within the practice. Simplify registration. Ask patients to complete screening forms before an appointment; this information could be entered directly into their EHR.3 Consider using physician-extender staff and other personnel, such as scribes, to complete documentation into the EHR.3,8 This may help reduce burnout, create more time for clinical care, and improve face-to-face patient interactions.8 Employing scribes can allow doctors to be better able to directly attend to their patients while complying with record-keeping needs. Although scribes make charting easier, they are an additional expense, and must be trained.

Consider EHR training

EHR training sessions can teach you how to use your EHR system more efficiently.6 Such education may help boost confidence, aid documentation, and reduce the amount of time spent correcting coding errors. In a study of 3,500 physicians who underwent a 3-day intensive EHR training course, 85% to 98% reported having improved the quality, readability, and clinical accuracy of their documentation.6

Help shape future EHRs

Individual doctors and professional groups can promote EHR improvements through their state, regional, and/or national organizations and medical societies. These bodies should deliver EHR revision recommendations to government officials, who can craft laws and regulations, and can influence regulators and/or insurance companies. Clinicians also can communicate with EHR developers on ways to simplify the usability of these tools, such as reducing the amount of steps the EHR’s interface requires.5 With a more efficient EHR, we can better concentrate on patient care, which will reduce expenses and should yield better outcomes.

1. Ehrenfeld JM, Wonderer JP. Technology as friend or foe? Do electronic health records increase burnout? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2018;31(3):357-360.

2. Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016;13:1d.

3. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426.

4. Fogarty CT, Winters P, Farah S. Improving patient-centered communication while using an electronic health record: report from a curriculum evaluation. Int J Psych Med. 2016;51(4):379-389.

5. Guo U, Chen L, Mehta PH. Electronic health record innovations: helping physicians - one less click at a time. Health Inf Manag. 2017;46(3):140-144.

6. Robinson KE, Kersey JA. Novel electronic health record (EHR) education intervention in large healthcare organization improves quality, efficiency, time, and impact on burnout. Medicine. 2018;91(38):e123419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012319.

7. Fogarty CT. Getting your notes done on time. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(2):40.

8. DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384-408.

The electronic health record (EHR) was introduced to improve how clinicians document patient information, contribute to medical research, and allow for medical records to be universally transferable.1 However, many clinicians find EHRs to be burdensome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Clinicians often spend multiple hours each day navigating their EHR system, which reduces the amount of time they spend interacting with patients and contributes to physician burnout.1-3 For example, in a study of 142 family medicine physicians, clinicians reported that they spent approximately 6 hours per work day interacting with their EHR.3

Clearly, the EHR needs a fundamental revision. In the meantime, how can we adapt to improve the situation? Here I suggest practical steps clinicians can take to improve their experience with their EHR system.4-8

Steps to take during patient visits

Because entering information into the EHR can be distracting, be prepared to multitask during each clinical encounter.1-7 Be ready to address pertinent inquiries and issues your patient raises, and provide instructions on therapies and interventions. Because interpersonal relations are important during clinical encounters, establish interaction with your patient by acknowledging them and maintaining frequent eye contact.7 Consider allowing your patient to view the EHR screen because doing so might increase his/her involvement in the visit.

So that you can pay closer attention to your patient, consider taking notes during the visit and entering the information into the EHR later. Consider improving your typing skills to increase the speed of your note-taking. Alternatively, using a voice-recognition recording tool to transcribe your notes via speech might help you spend less time on note-taking.3 Whenever possible, finish charting for one patient before meeting with the next because doing so will save time and help you to better remember details.7

In addition, lowering your overall stress might help reduce the burden of using the EHR.3-5 Adopt healthy behaviors, including good sleep, nutrition, exercise, and hobbies, and strive for balance in your routines. Attend to any personal medical or psychiatric conditions, and avoid misusing alcohol, medications, or other substances.

Optimize how your practice functions

With your clinical group and colleagues, create a comfortable environment, good patient-to-doctor interactions, and a smooth flow within the practice. Simplify registration. Ask patients to complete screening forms before an appointment; this information could be entered directly into their EHR.3 Consider using physician-extender staff and other personnel, such as scribes, to complete documentation into the EHR.3,8 This may help reduce burnout, create more time for clinical care, and improve face-to-face patient interactions.8 Employing scribes can allow doctors to be better able to directly attend to their patients while complying with record-keeping needs. Although scribes make charting easier, they are an additional expense, and must be trained.

Consider EHR training

EHR training sessions can teach you how to use your EHR system more efficiently.6 Such education may help boost confidence, aid documentation, and reduce the amount of time spent correcting coding errors. In a study of 3,500 physicians who underwent a 3-day intensive EHR training course, 85% to 98% reported having improved the quality, readability, and clinical accuracy of their documentation.6

Help shape future EHRs

Individual doctors and professional groups can promote EHR improvements through their state, regional, and/or national organizations and medical societies. These bodies should deliver EHR revision recommendations to government officials, who can craft laws and regulations, and can influence regulators and/or insurance companies. Clinicians also can communicate with EHR developers on ways to simplify the usability of these tools, such as reducing the amount of steps the EHR’s interface requires.5 With a more efficient EHR, we can better concentrate on patient care, which will reduce expenses and should yield better outcomes.

The electronic health record (EHR) was introduced to improve how clinicians document patient information, contribute to medical research, and allow for medical records to be universally transferable.1 However, many clinicians find EHRs to be burdensome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Clinicians often spend multiple hours each day navigating their EHR system, which reduces the amount of time they spend interacting with patients and contributes to physician burnout.1-3 For example, in a study of 142 family medicine physicians, clinicians reported that they spent approximately 6 hours per work day interacting with their EHR.3

Clearly, the EHR needs a fundamental revision. In the meantime, how can we adapt to improve the situation? Here I suggest practical steps clinicians can take to improve their experience with their EHR system.4-8

Steps to take during patient visits

Because entering information into the EHR can be distracting, be prepared to multitask during each clinical encounter.1-7 Be ready to address pertinent inquiries and issues your patient raises, and provide instructions on therapies and interventions. Because interpersonal relations are important during clinical encounters, establish interaction with your patient by acknowledging them and maintaining frequent eye contact.7 Consider allowing your patient to view the EHR screen because doing so might increase his/her involvement in the visit.

So that you can pay closer attention to your patient, consider taking notes during the visit and entering the information into the EHR later. Consider improving your typing skills to increase the speed of your note-taking. Alternatively, using a voice-recognition recording tool to transcribe your notes via speech might help you spend less time on note-taking.3 Whenever possible, finish charting for one patient before meeting with the next because doing so will save time and help you to better remember details.7

In addition, lowering your overall stress might help reduce the burden of using the EHR.3-5 Adopt healthy behaviors, including good sleep, nutrition, exercise, and hobbies, and strive for balance in your routines. Attend to any personal medical or psychiatric conditions, and avoid misusing alcohol, medications, or other substances.

Optimize how your practice functions

With your clinical group and colleagues, create a comfortable environment, good patient-to-doctor interactions, and a smooth flow within the practice. Simplify registration. Ask patients to complete screening forms before an appointment; this information could be entered directly into their EHR.3 Consider using physician-extender staff and other personnel, such as scribes, to complete documentation into the EHR.3,8 This may help reduce burnout, create more time for clinical care, and improve face-to-face patient interactions.8 Employing scribes can allow doctors to be better able to directly attend to their patients while complying with record-keeping needs. Although scribes make charting easier, they are an additional expense, and must be trained.

Consider EHR training

EHR training sessions can teach you how to use your EHR system more efficiently.6 Such education may help boost confidence, aid documentation, and reduce the amount of time spent correcting coding errors. In a study of 3,500 physicians who underwent a 3-day intensive EHR training course, 85% to 98% reported having improved the quality, readability, and clinical accuracy of their documentation.6

Help shape future EHRs

Individual doctors and professional groups can promote EHR improvements through their state, regional, and/or national organizations and medical societies. These bodies should deliver EHR revision recommendations to government officials, who can craft laws and regulations, and can influence regulators and/or insurance companies. Clinicians also can communicate with EHR developers on ways to simplify the usability of these tools, such as reducing the amount of steps the EHR’s interface requires.5 With a more efficient EHR, we can better concentrate on patient care, which will reduce expenses and should yield better outcomes.

1. Ehrenfeld JM, Wonderer JP. Technology as friend or foe? Do electronic health records increase burnout? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2018;31(3):357-360.

2. Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016;13:1d.

3. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426.

4. Fogarty CT, Winters P, Farah S. Improving patient-centered communication while using an electronic health record: report from a curriculum evaluation. Int J Psych Med. 2016;51(4):379-389.

5. Guo U, Chen L, Mehta PH. Electronic health record innovations: helping physicians - one less click at a time. Health Inf Manag. 2017;46(3):140-144.

6. Robinson KE, Kersey JA. Novel electronic health record (EHR) education intervention in large healthcare organization improves quality, efficiency, time, and impact on burnout. Medicine. 2018;91(38):e123419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012319.

7. Fogarty CT. Getting your notes done on time. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(2):40.

8. DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384-408.

1. Ehrenfeld JM, Wonderer JP. Technology as friend or foe? Do electronic health records increase burnout? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2018;31(3):357-360.

2. Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016;13:1d.

3. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426.

4. Fogarty CT, Winters P, Farah S. Improving patient-centered communication while using an electronic health record: report from a curriculum evaluation. Int J Psych Med. 2016;51(4):379-389.

5. Guo U, Chen L, Mehta PH. Electronic health record innovations: helping physicians - one less click at a time. Health Inf Manag. 2017;46(3):140-144.

6. Robinson KE, Kersey JA. Novel electronic health record (EHR) education intervention in large healthcare organization improves quality, efficiency, time, and impact on burnout. Medicine. 2018;91(38):e123419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012319.

7. Fogarty CT. Getting your notes done on time. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(2):40.

8. DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384-408.

How to best use digital technology to help your patients

As psychiatrists, we are increasingly using digital technology, such as e-mail, video conferencing, social media, and text messaging, to communicate with and even treat our patients.1 The benefits of using digital technology for treating patients include, but are not limited to, enhancing access to psychiatric services that are unavailable due to a patient’s geographical location and/or physical disability; providing more cost‐effective delivery of services; and creating more ways for patients to communicate with their physicians.1 While there are benefits to using digital technology, there are also possible repercussions, such as breaches of confidentiality or boundary violations.2 Although there is no evidence-based guidance about how to best use digital technology in patient care,3 the following approaches can help you protect your patients and minimize your liability.

Assess competence. Determine how familiar and comfortable both you and your patient are with the specific software and/or devices you intend to use. Confirm that your patient can access the technology, and inform them of the benefits and risks of using digital technology in their care.1

Create a written policy about your use of digital technology, and review it with all patients to explain how it will be used in their treatment.1 This policy should include a back-up plan in the event of technology failures.1 It should clearly explain that the information gathered with this technology can become part of the patient’s medical record. It should also prohibit patients from using their devices to record other patients in the waiting room or other areas. Such a policy could enhance the protection of private information and help maintain clear boundaries.1 Review and update your policy as often as needed.

Obtain your patients’ written consent to use digital technology. If you want to post information about your patients on social media, obtain their written consent to do so, and mutually agree as to what information would be posted. This should not include their identity or confidential information.1

Do not accept friend requests or contact requests from current or former patients on any social networking platform. Do not follow your patients’ blogs, Twitter accounts, or any other accounts. Be aware that if you and your patients share the same “friend” network on social media, this may create boundary confusion, inappropriate dual relationships, and potential conflicts of interest.1 Keep personal and professional accounts separate to maintain appropriate boundaries and minimize compromising patient confidentiality. Do not post private information on professional practice accounts, and do not link/sync your personal accounts with professional accounts.

Do not store patient information on your personal electronic devices because these devices could be lost or hacked. Avoid contacting your patients via non-secured platforms because doing so could compromise patient confidentiality. Use encrypted software and firewalls for communicating with your patients and storing their information.1 Also, periodically assess your confidentiality policies and procedures to ensure compliance with appropriate statutes and laws.1

1. Reamer FG. Evolving standards of care in the age of cybertechnology. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(2):257-269.

2. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499, 520.

3. Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best practices for surgeons’ social media use: statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):317-327.

As psychiatrists, we are increasingly using digital technology, such as e-mail, video conferencing, social media, and text messaging, to communicate with and even treat our patients.1 The benefits of using digital technology for treating patients include, but are not limited to, enhancing access to psychiatric services that are unavailable due to a patient’s geographical location and/or physical disability; providing more cost‐effective delivery of services; and creating more ways for patients to communicate with their physicians.1 While there are benefits to using digital technology, there are also possible repercussions, such as breaches of confidentiality or boundary violations.2 Although there is no evidence-based guidance about how to best use digital technology in patient care,3 the following approaches can help you protect your patients and minimize your liability.

Assess competence. Determine how familiar and comfortable both you and your patient are with the specific software and/or devices you intend to use. Confirm that your patient can access the technology, and inform them of the benefits and risks of using digital technology in their care.1

Create a written policy about your use of digital technology, and review it with all patients to explain how it will be used in their treatment.1 This policy should include a back-up plan in the event of technology failures.1 It should clearly explain that the information gathered with this technology can become part of the patient’s medical record. It should also prohibit patients from using their devices to record other patients in the waiting room or other areas. Such a policy could enhance the protection of private information and help maintain clear boundaries.1 Review and update your policy as often as needed.

Obtain your patients’ written consent to use digital technology. If you want to post information about your patients on social media, obtain their written consent to do so, and mutually agree as to what information would be posted. This should not include their identity or confidential information.1

Do not accept friend requests or contact requests from current or former patients on any social networking platform. Do not follow your patients’ blogs, Twitter accounts, or any other accounts. Be aware that if you and your patients share the same “friend” network on social media, this may create boundary confusion, inappropriate dual relationships, and potential conflicts of interest.1 Keep personal and professional accounts separate to maintain appropriate boundaries and minimize compromising patient confidentiality. Do not post private information on professional practice accounts, and do not link/sync your personal accounts with professional accounts.

Do not store patient information on your personal electronic devices because these devices could be lost or hacked. Avoid contacting your patients via non-secured platforms because doing so could compromise patient confidentiality. Use encrypted software and firewalls for communicating with your patients and storing their information.1 Also, periodically assess your confidentiality policies and procedures to ensure compliance with appropriate statutes and laws.1

As psychiatrists, we are increasingly using digital technology, such as e-mail, video conferencing, social media, and text messaging, to communicate with and even treat our patients.1 The benefits of using digital technology for treating patients include, but are not limited to, enhancing access to psychiatric services that are unavailable due to a patient’s geographical location and/or physical disability; providing more cost‐effective delivery of services; and creating more ways for patients to communicate with their physicians.1 While there are benefits to using digital technology, there are also possible repercussions, such as breaches of confidentiality or boundary violations.2 Although there is no evidence-based guidance about how to best use digital technology in patient care,3 the following approaches can help you protect your patients and minimize your liability.

Assess competence. Determine how familiar and comfortable both you and your patient are with the specific software and/or devices you intend to use. Confirm that your patient can access the technology, and inform them of the benefits and risks of using digital technology in their care.1

Create a written policy about your use of digital technology, and review it with all patients to explain how it will be used in their treatment.1 This policy should include a back-up plan in the event of technology failures.1 It should clearly explain that the information gathered with this technology can become part of the patient’s medical record. It should also prohibit patients from using their devices to record other patients in the waiting room or other areas. Such a policy could enhance the protection of private information and help maintain clear boundaries.1 Review and update your policy as often as needed.

Obtain your patients’ written consent to use digital technology. If you want to post information about your patients on social media, obtain their written consent to do so, and mutually agree as to what information would be posted. This should not include their identity or confidential information.1

Do not accept friend requests or contact requests from current or former patients on any social networking platform. Do not follow your patients’ blogs, Twitter accounts, or any other accounts. Be aware that if you and your patients share the same “friend” network on social media, this may create boundary confusion, inappropriate dual relationships, and potential conflicts of interest.1 Keep personal and professional accounts separate to maintain appropriate boundaries and minimize compromising patient confidentiality. Do not post private information on professional practice accounts, and do not link/sync your personal accounts with professional accounts.

Do not store patient information on your personal electronic devices because these devices could be lost or hacked. Avoid contacting your patients via non-secured platforms because doing so could compromise patient confidentiality. Use encrypted software and firewalls for communicating with your patients and storing their information.1 Also, periodically assess your confidentiality policies and procedures to ensure compliance with appropriate statutes and laws.1

1. Reamer FG. Evolving standards of care in the age of cybertechnology. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(2):257-269.

2. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499, 520.

3. Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best practices for surgeons’ social media use: statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):317-327.

1. Reamer FG. Evolving standards of care in the age of cybertechnology. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(2):257-269.

2. Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. 2014;39(7):491-499, 520.

3. Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best practices for surgeons’ social media use: statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):317-327.

Changes in patient behavior during COVID-19: What I’ve observed

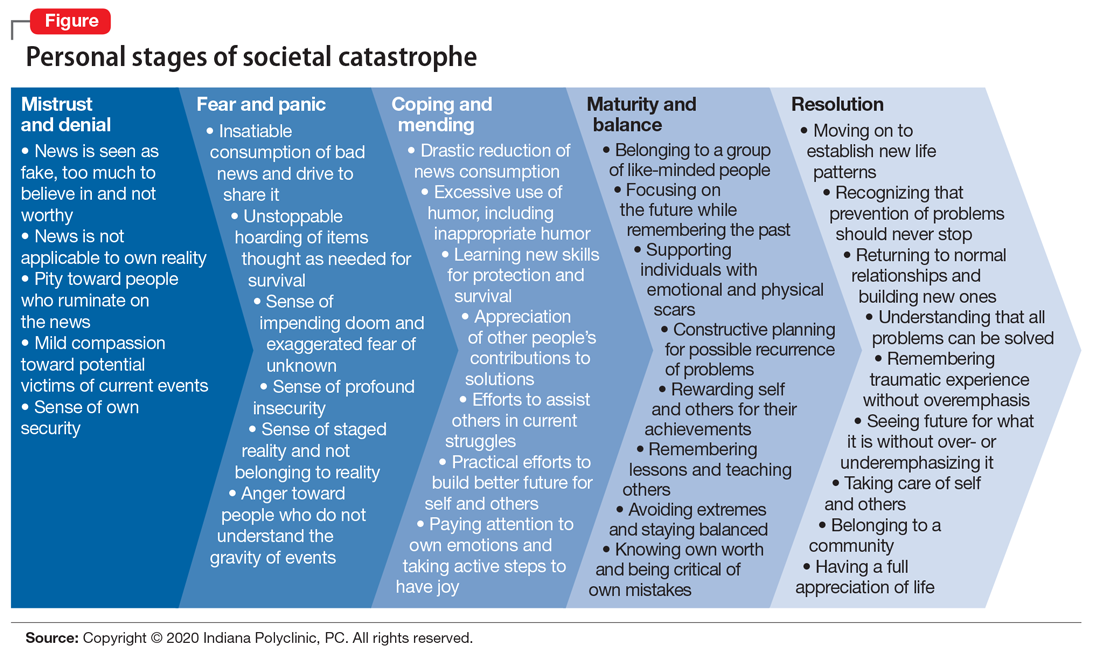

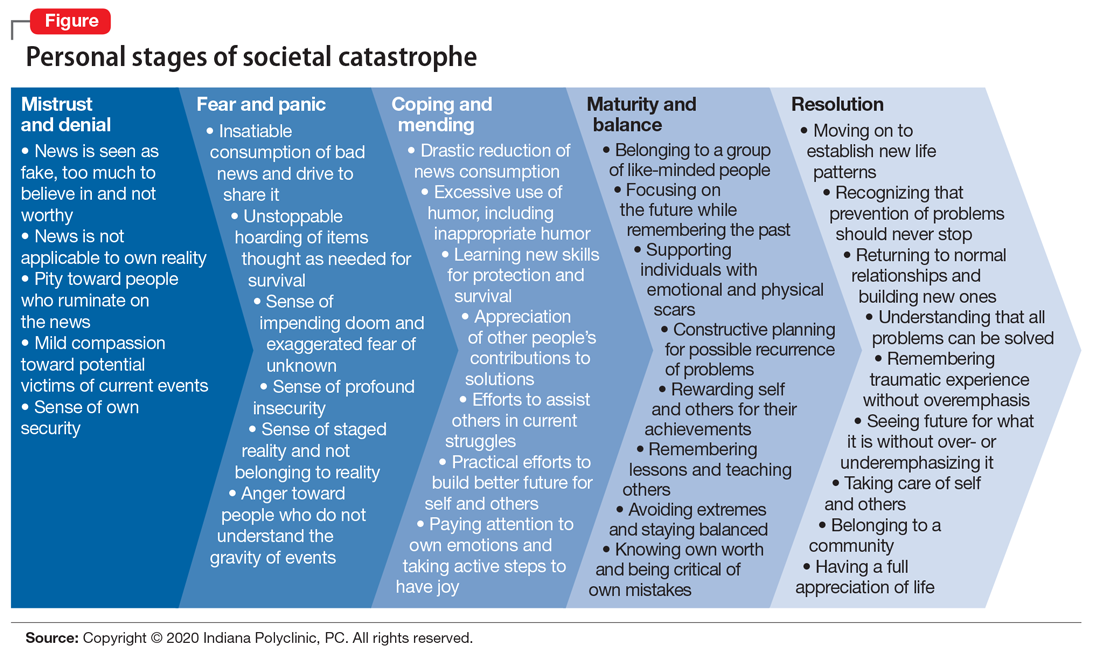

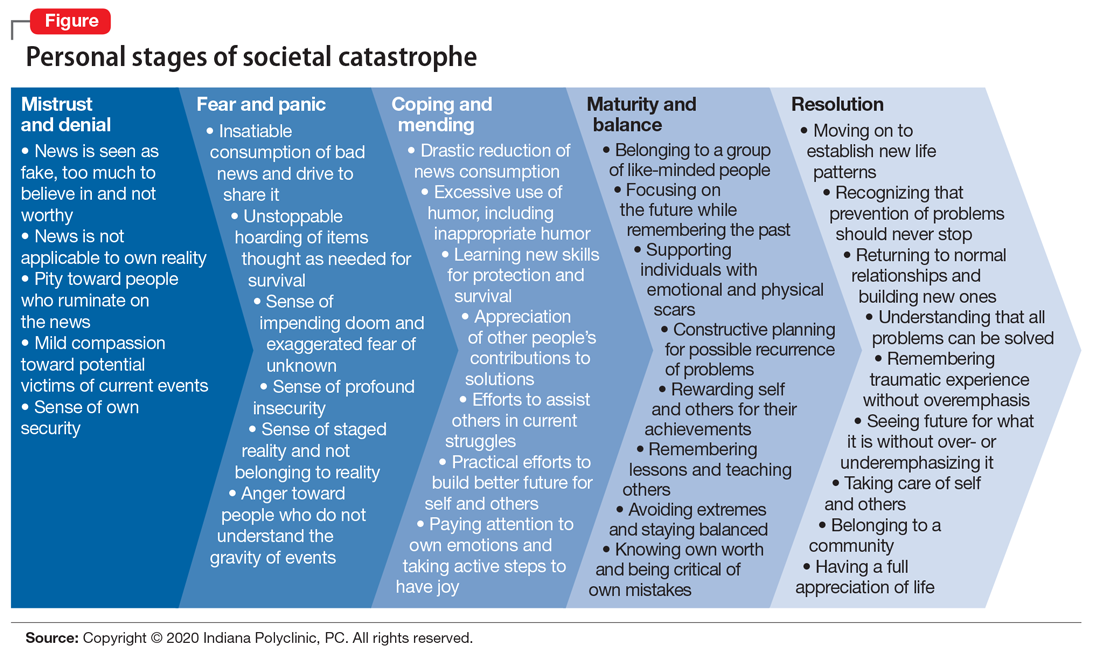

Unprecedented circumstances, extraordinary times, continental shift, life-altering experience—the descriptions of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have been endless, and accurate. Every clinician who has cared for patients during these trying times has noticed new patterns in patient behavior. Psychiatrists are acutely aware of the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive methods that patients are using to protect themselves from the chaos around them, and the ways in which they process a societal catastrophe such as COVID-19 (Figure). Here are some new patterns I have noticed among my own patients.

Physical and emotional separation

I first noticed the changes in my patients’ behavior at the front desk, where they now spend less time talking with the staff. They bring their own pens for filling out the paperwork, avoid touching items around them, and try to keep social interactions brief and to the point. Patients have been more cooperative about scheduling and rescheduling their appointments. They have generally been nicer to the staff, frequently thanking us for the work we do, and verbalizing their support for health care professionals in general.

Patients have been more supportive of their family members and other patients in the clinic, with some noticeable exceptions, such as maintaining social distancing for their own comfort and safety. Some patients wear face masks not just for safety but also to separate themselves and hide their emotions from the world. This allows them to feel more emotionally secure when interacting with other people.

The use of telehealth has given many patients the security of not having to leave their home, and the decreased need for travel adds to their comfort.

Changes I didn’t expect

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in some unexpected changes in my patients. Only a minority of my patients have expressed increased anxiety, while most have become less anxious overall on issues other than the pandemic. Many of my patients who have stressful jobs, especially teachers, say they feel more comfortable working from home and have less anxiety and depression because they are removed from their daily stressors. There also has been an increase in patients’ use of humor, including inappropriate humor, to defend against their fear of COVID-19.

Our clinic is a multidisciplinary facility that specializes in integrating mental and physical health treatments for pain, and for some patients, increased anxiety is clearly associated with an increase in pain. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients have recognized this connection and verbalized their concerns. Some somatic patients have had a decrease in their physical symptoms, including chronic pain, because they see that the whole world is not well, which somehow helps to validate their concerns.

The changes in our patients’ psychological well-being will likely continue to morph as we enter a more stable period. The eventual resolution of the pandemic will bring further changes to our patients’ emotional lives. As we go through these times together, we will continue to uncover new ways that our patients will use to defend themselves against stress and adversities.

Unprecedented circumstances, extraordinary times, continental shift, life-altering experience—the descriptions of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have been endless, and accurate. Every clinician who has cared for patients during these trying times has noticed new patterns in patient behavior. Psychiatrists are acutely aware of the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive methods that patients are using to protect themselves from the chaos around them, and the ways in which they process a societal catastrophe such as COVID-19 (Figure). Here are some new patterns I have noticed among my own patients.

Physical and emotional separation

I first noticed the changes in my patients’ behavior at the front desk, where they now spend less time talking with the staff. They bring their own pens for filling out the paperwork, avoid touching items around them, and try to keep social interactions brief and to the point. Patients have been more cooperative about scheduling and rescheduling their appointments. They have generally been nicer to the staff, frequently thanking us for the work we do, and verbalizing their support for health care professionals in general.