User login

What to tell parents whose child saw them having sex

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.

Discuss what happened. Tell parents to explore their child’s impression of what he/she saw. Tailoring the discussion to the child’s age is important. For example, a 3-year-old might wonder if anyone was harmed, and might need reassurance, whereas a 12-year-old is likely to have a better understanding of sex but still feel uncomfortable. Educational conversations about sexuality might be appropriate for children age 8 to 12. The parents’ goal should be to answer questions honestly without oversharing, and to leave the door open—so to speak—for future conversations.

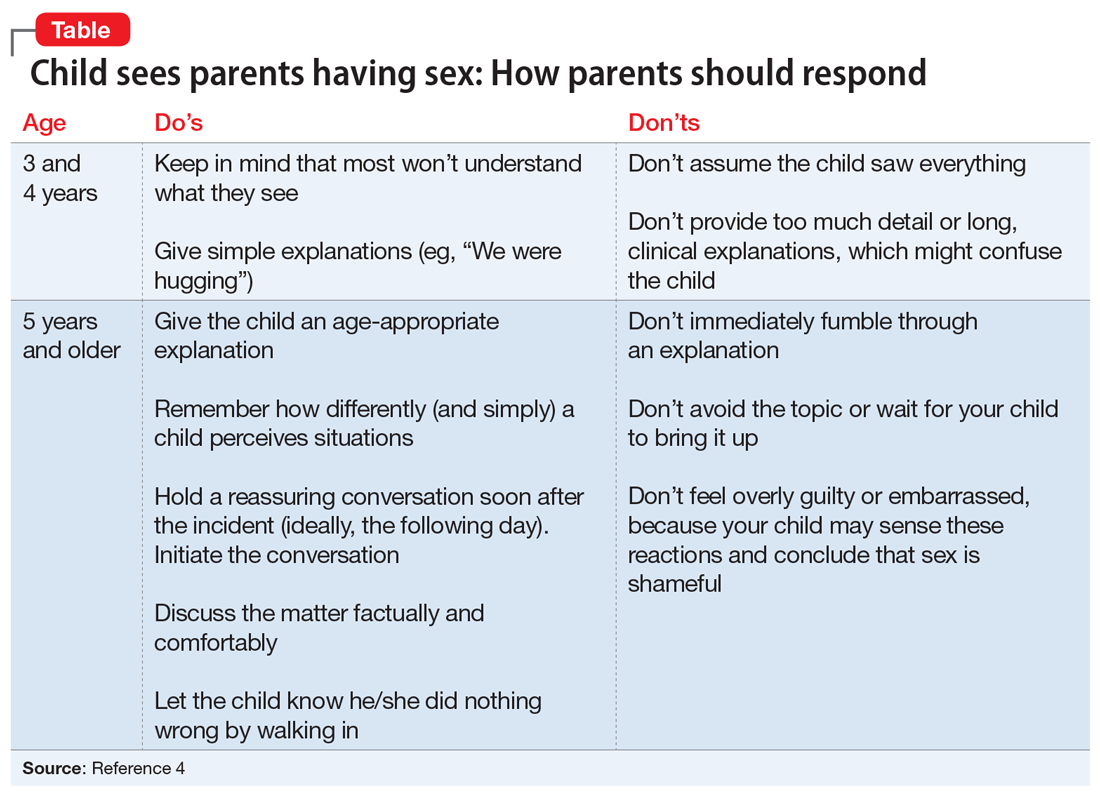

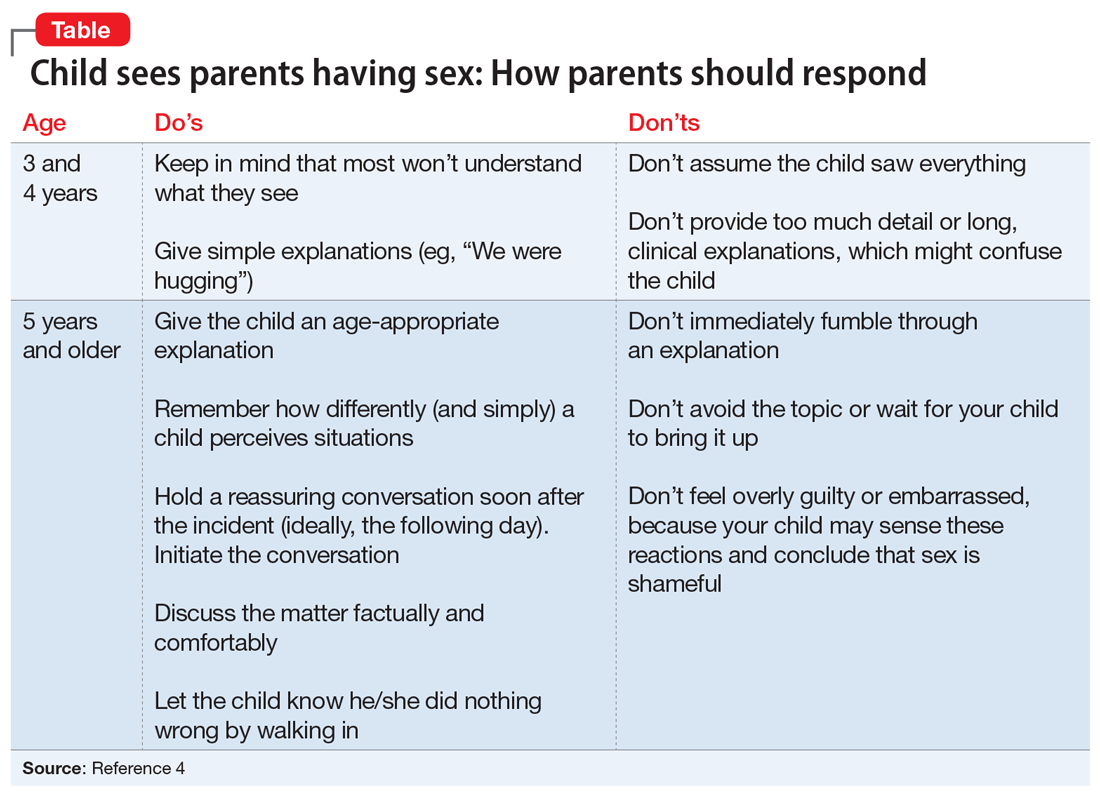

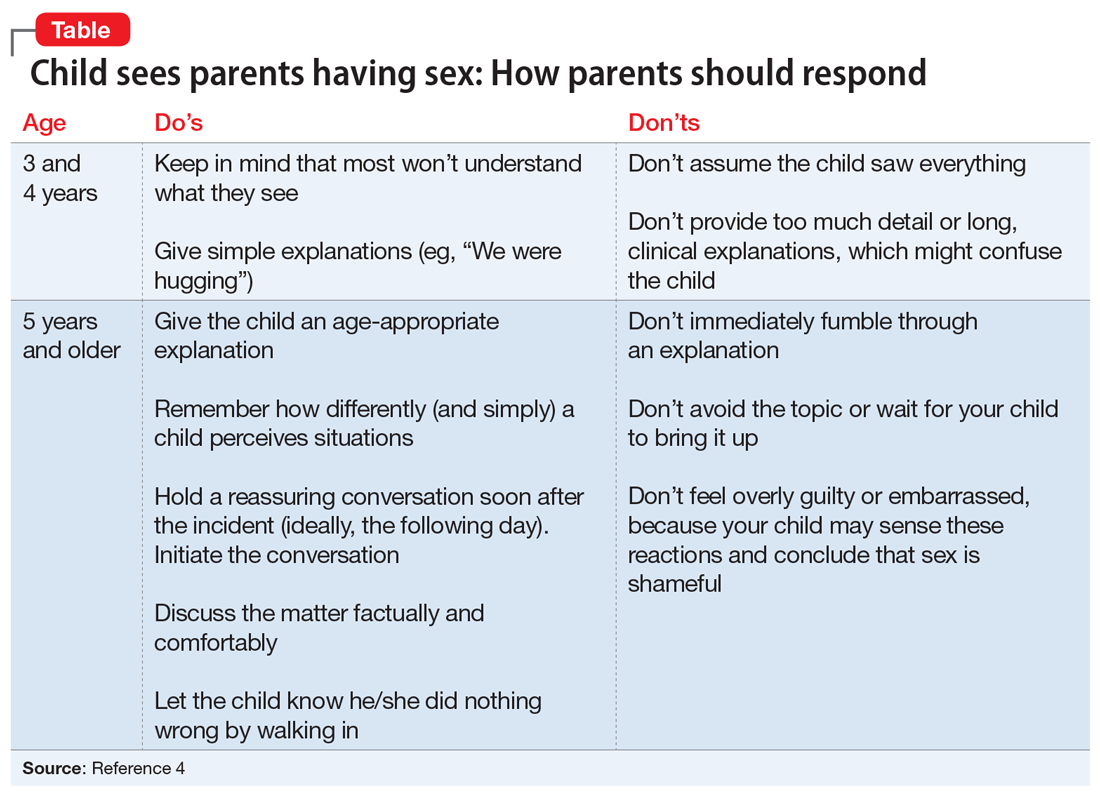

Recommend that parents use plain, factual language to answer any questions their child asks. Statements such as “We were having a private, adult moment” can be helpful. Parents can categorize sex as a universal activity that is not harmful or scary by telling their child something such as, “This is what all parents do.” Parents should avoid providing unnecessary information or answering questions their child is not asking. The Table4 offers guidance on how parents might handle such conversations.

Consider potentially positive outcomes. Although parents may feel guilty or describe this as a terrible situation, remind them that there are some potentially healthy outcomes. For example, such incidents may help reassure the child that their parents love each other, which might give him/her a sense of happiness and security.

Take steps to prevent this from happening again. Advise parents to lock the door when having sex. Remind them to consider the proximity of rooms because their child might hear noises and become curious.

1. Blum HP. On the concept and consequences of the primal scene. Psychoanal Q. 1979;48(1):27-47.

2. Hoyt MF. On the psychology and psychopathology of primal-scene experience. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1980;8(3):311-335.

3. Ikonen P, Rechardt E. On the universal nature of primal scene fantasies. Int J Psychoanal. 1984;65(pt 1):63-72.

4. Pelly J. Four things my four-year-old already knows about sex. Today’s Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/4-things-my-4-year-old-already-knows-about-sex/. Published February 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.

Discuss what happened. Tell parents to explore their child’s impression of what he/she saw. Tailoring the discussion to the child’s age is important. For example, a 3-year-old might wonder if anyone was harmed, and might need reassurance, whereas a 12-year-old is likely to have a better understanding of sex but still feel uncomfortable. Educational conversations about sexuality might be appropriate for children age 8 to 12. The parents’ goal should be to answer questions honestly without oversharing, and to leave the door open—so to speak—for future conversations.

Recommend that parents use plain, factual language to answer any questions their child asks. Statements such as “We were having a private, adult moment” can be helpful. Parents can categorize sex as a universal activity that is not harmful or scary by telling their child something such as, “This is what all parents do.” Parents should avoid providing unnecessary information or answering questions their child is not asking. The Table4 offers guidance on how parents might handle such conversations.

Consider potentially positive outcomes. Although parents may feel guilty or describe this as a terrible situation, remind them that there are some potentially healthy outcomes. For example, such incidents may help reassure the child that their parents love each other, which might give him/her a sense of happiness and security.

Take steps to prevent this from happening again. Advise parents to lock the door when having sex. Remind them to consider the proximity of rooms because their child might hear noises and become curious.

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.

Discuss what happened. Tell parents to explore their child’s impression of what he/she saw. Tailoring the discussion to the child’s age is important. For example, a 3-year-old might wonder if anyone was harmed, and might need reassurance, whereas a 12-year-old is likely to have a better understanding of sex but still feel uncomfortable. Educational conversations about sexuality might be appropriate for children age 8 to 12. The parents’ goal should be to answer questions honestly without oversharing, and to leave the door open—so to speak—for future conversations.

Recommend that parents use plain, factual language to answer any questions their child asks. Statements such as “We were having a private, adult moment” can be helpful. Parents can categorize sex as a universal activity that is not harmful or scary by telling their child something such as, “This is what all parents do.” Parents should avoid providing unnecessary information or answering questions their child is not asking. The Table4 offers guidance on how parents might handle such conversations.

Consider potentially positive outcomes. Although parents may feel guilty or describe this as a terrible situation, remind them that there are some potentially healthy outcomes. For example, such incidents may help reassure the child that their parents love each other, which might give him/her a sense of happiness and security.

Take steps to prevent this from happening again. Advise parents to lock the door when having sex. Remind them to consider the proximity of rooms because their child might hear noises and become curious.

1. Blum HP. On the concept and consequences of the primal scene. Psychoanal Q. 1979;48(1):27-47.

2. Hoyt MF. On the psychology and psychopathology of primal-scene experience. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1980;8(3):311-335.

3. Ikonen P, Rechardt E. On the universal nature of primal scene fantasies. Int J Psychoanal. 1984;65(pt 1):63-72.

4. Pelly J. Four things my four-year-old already knows about sex. Today’s Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/4-things-my-4-year-old-already-knows-about-sex/. Published February 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

1. Blum HP. On the concept and consequences of the primal scene. Psychoanal Q. 1979;48(1):27-47.

2. Hoyt MF. On the psychology and psychopathology of primal-scene experience. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1980;8(3):311-335.

3. Ikonen P, Rechardt E. On the universal nature of primal scene fantasies. Int J Psychoanal. 1984;65(pt 1):63-72.

4. Pelly J. Four things my four-year-old already knows about sex. Today’s Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/4-things-my-4-year-old-already-knows-about-sex/. Published February 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.