User login

Child trafficking: How to recognize the signs

Child trafficking—a modern-day form of slavery that continues to destroy many lives—often is hidden, even from the clinicians who see its victims. Traffickers typically exploit children for labor or commercial sexual work. The signs and symptoms that suggest a child is being trafficked may be less clear than those of the psychiatric illnesses we usually diagnose and treat. In this article, I summarize characteristics that could be helpful to note when you suspect a child is being trafficked, and offer some resources for helping victims.

How to identify possible victims

Children can be trafficked anywhere. The concept of a child being picked up off a street corner is outdated. Trafficking occurs in cities, suburbs, and rural areas. It happens in hotel rooms, at truck stops, on quiet residential streets, and in expensive homes. The internet has made it easier for traffickers to find victims.

Traffickers typically target youth who are emotionally and physically vulnerable. They often seek out teenagers who are undergoing financial hardships, experiencing family conflict, or have survived natural disasters. Many victims are runaways. In 2016, 1 in 6 child runaways reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children were likely victims of trafficking.1 Of those children, 86% were receiving social services support or living in foster homes.

Traffickers are adept at emotional manipulation, which may explain why a child or adolescent might minimize the abuse during a clinical visit. Traffickers shroud the realities of trafficking with notions of love and inclusion. They use several physical and mental schemes to keep children and adolescents in their grip, such as withholding food, sleep, or medical care. Therefore, we should check for signs and symptoms of chronic medical conditions that have gone untreated, malnutrition, or bruises in various stages of healing.

Connecting risk factors for trafficking to dramatic changes in a young patient’s behavior is challenging. These youth often have dropped out of school, lack consistent family support, and spend their nights in search of a warm place to sleep. Their lives are upended. A child who once was more social may be forced into isolation and make excuses for why she no longer spends time with her friends.

In a study of 106 survivors of domestic sex trafficking, approximately 89% of respondents reported depression during depression. Many respondents reported experiencing anxiety (76.4%), nightmares (73.6%), flashbacks (68%), low self-esteem (81.1%), or feelings of shame or guilt (82.1%).2 Almost 88% of respondents said that they saw a doctor or other clinician while being trafficked, but their clinicians were unable to recognize the signs of trafficking. Part of the challenge is that many children and adolescents are not comfortable discussing their situations with clinicians because they may struggle with shame and guilt. Their traffickers also might have convinced them that they are criminals, not victims. These patients also may have an overwhelming fear of their trafficker, being reported to child welfare authorities, being arrested, being deported, or having their traffickers retaliate against their families. Gaining the trust of a patient who is being trafficked is critical, but not easy, because children may be skeptical of a clinician’s promise of confidentiality.

Some signs of trafficking overlap with the psychiatric presentations with which we are more familiar. These patients may abuse drugs or alcohol as means of escape or because their traffickers force them to use substances.2 They may show symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and may be disoriented. Other indicators may be more telling, such as if a child or adolescent describes:

- having no control of their schedules or forms of identification

- having to work excessively long hours, often to pay off an overwhelming debt

- having high security measures installed in their place of residence (such as cameras or barred windows).

Continue to: Also, they may be...

Also, they may be dressed inappropriately for the weather.

We should be concerned when patients’ responses seem coached, if they say they are isolated from their family and community, or if they are submissive or overly timid. In addition, our suspicions should be raised if an accompanying adult guardian insists on sitting in on the appointment or translating for the child. In such instances, we may request that the guardian remain in the waiting area during the appointment so the child will have the opportunity to speak freely.2

How to help a suspected victim

Several local and national organizations help trafficking victims. These organizations provide educational materials and training opportunities for clinicians, as well as direct support for victims. The Homeland Security Blue Campaign advises against confronting a suspected trafficker directly and encourages clinicians to instead report suspected cases to 1-866-347-2423.3

Clinicians can better help children who are trafficked by taking the following 5 steps:

- Learn about the risk factors and signs of child trafficking.

- Post the National Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888) in your waiting room.

- Determine if your patient is in danger and needs to be moved to a safe place.

- Connect the patient to social service agencies that can provide financial support and housing assistance so he/she doesn’t feel trapped by financial burdens.

- Work to rebuild their emotional and physical well-being while treating depression, PTSD, substance abuse, or any other mental illness.

1. National Center for Missing and Exploited Childr en. Missing children, state care, and child sex trafficking. http://www.missingkids.com/content/dam/missingkids/pdfs/publications/missingchildrenstatecare.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2019.

2. Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23(1):61-91.

3. Blue Campaign. Identify a victim. US Department of Homeland Security. https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/identify-victim. Accessed June 10, 2019.

Child trafficking—a modern-day form of slavery that continues to destroy many lives—often is hidden, even from the clinicians who see its victims. Traffickers typically exploit children for labor or commercial sexual work. The signs and symptoms that suggest a child is being trafficked may be less clear than those of the psychiatric illnesses we usually diagnose and treat. In this article, I summarize characteristics that could be helpful to note when you suspect a child is being trafficked, and offer some resources for helping victims.

How to identify possible victims

Children can be trafficked anywhere. The concept of a child being picked up off a street corner is outdated. Trafficking occurs in cities, suburbs, and rural areas. It happens in hotel rooms, at truck stops, on quiet residential streets, and in expensive homes. The internet has made it easier for traffickers to find victims.

Traffickers typically target youth who are emotionally and physically vulnerable. They often seek out teenagers who are undergoing financial hardships, experiencing family conflict, or have survived natural disasters. Many victims are runaways. In 2016, 1 in 6 child runaways reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children were likely victims of trafficking.1 Of those children, 86% were receiving social services support or living in foster homes.

Traffickers are adept at emotional manipulation, which may explain why a child or adolescent might minimize the abuse during a clinical visit. Traffickers shroud the realities of trafficking with notions of love and inclusion. They use several physical and mental schemes to keep children and adolescents in their grip, such as withholding food, sleep, or medical care. Therefore, we should check for signs and symptoms of chronic medical conditions that have gone untreated, malnutrition, or bruises in various stages of healing.

Connecting risk factors for trafficking to dramatic changes in a young patient’s behavior is challenging. These youth often have dropped out of school, lack consistent family support, and spend their nights in search of a warm place to sleep. Their lives are upended. A child who once was more social may be forced into isolation and make excuses for why she no longer spends time with her friends.

In a study of 106 survivors of domestic sex trafficking, approximately 89% of respondents reported depression during depression. Many respondents reported experiencing anxiety (76.4%), nightmares (73.6%), flashbacks (68%), low self-esteem (81.1%), or feelings of shame or guilt (82.1%).2 Almost 88% of respondents said that they saw a doctor or other clinician while being trafficked, but their clinicians were unable to recognize the signs of trafficking. Part of the challenge is that many children and adolescents are not comfortable discussing their situations with clinicians because they may struggle with shame and guilt. Their traffickers also might have convinced them that they are criminals, not victims. These patients also may have an overwhelming fear of their trafficker, being reported to child welfare authorities, being arrested, being deported, or having their traffickers retaliate against their families. Gaining the trust of a patient who is being trafficked is critical, but not easy, because children may be skeptical of a clinician’s promise of confidentiality.

Some signs of trafficking overlap with the psychiatric presentations with which we are more familiar. These patients may abuse drugs or alcohol as means of escape or because their traffickers force them to use substances.2 They may show symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and may be disoriented. Other indicators may be more telling, such as if a child or adolescent describes:

- having no control of their schedules or forms of identification

- having to work excessively long hours, often to pay off an overwhelming debt

- having high security measures installed in their place of residence (such as cameras or barred windows).

Continue to: Also, they may be...

Also, they may be dressed inappropriately for the weather.

We should be concerned when patients’ responses seem coached, if they say they are isolated from their family and community, or if they are submissive or overly timid. In addition, our suspicions should be raised if an accompanying adult guardian insists on sitting in on the appointment or translating for the child. In such instances, we may request that the guardian remain in the waiting area during the appointment so the child will have the opportunity to speak freely.2

How to help a suspected victim

Several local and national organizations help trafficking victims. These organizations provide educational materials and training opportunities for clinicians, as well as direct support for victims. The Homeland Security Blue Campaign advises against confronting a suspected trafficker directly and encourages clinicians to instead report suspected cases to 1-866-347-2423.3

Clinicians can better help children who are trafficked by taking the following 5 steps:

- Learn about the risk factors and signs of child trafficking.

- Post the National Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888) in your waiting room.

- Determine if your patient is in danger and needs to be moved to a safe place.

- Connect the patient to social service agencies that can provide financial support and housing assistance so he/she doesn’t feel trapped by financial burdens.

- Work to rebuild their emotional and physical well-being while treating depression, PTSD, substance abuse, or any other mental illness.

Child trafficking—a modern-day form of slavery that continues to destroy many lives—often is hidden, even from the clinicians who see its victims. Traffickers typically exploit children for labor or commercial sexual work. The signs and symptoms that suggest a child is being trafficked may be less clear than those of the psychiatric illnesses we usually diagnose and treat. In this article, I summarize characteristics that could be helpful to note when you suspect a child is being trafficked, and offer some resources for helping victims.

How to identify possible victims

Children can be trafficked anywhere. The concept of a child being picked up off a street corner is outdated. Trafficking occurs in cities, suburbs, and rural areas. It happens in hotel rooms, at truck stops, on quiet residential streets, and in expensive homes. The internet has made it easier for traffickers to find victims.

Traffickers typically target youth who are emotionally and physically vulnerable. They often seek out teenagers who are undergoing financial hardships, experiencing family conflict, or have survived natural disasters. Many victims are runaways. In 2016, 1 in 6 child runaways reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children were likely victims of trafficking.1 Of those children, 86% were receiving social services support or living in foster homes.

Traffickers are adept at emotional manipulation, which may explain why a child or adolescent might minimize the abuse during a clinical visit. Traffickers shroud the realities of trafficking with notions of love and inclusion. They use several physical and mental schemes to keep children and adolescents in their grip, such as withholding food, sleep, or medical care. Therefore, we should check for signs and symptoms of chronic medical conditions that have gone untreated, malnutrition, or bruises in various stages of healing.

Connecting risk factors for trafficking to dramatic changes in a young patient’s behavior is challenging. These youth often have dropped out of school, lack consistent family support, and spend their nights in search of a warm place to sleep. Their lives are upended. A child who once was more social may be forced into isolation and make excuses for why she no longer spends time with her friends.

In a study of 106 survivors of domestic sex trafficking, approximately 89% of respondents reported depression during depression. Many respondents reported experiencing anxiety (76.4%), nightmares (73.6%), flashbacks (68%), low self-esteem (81.1%), or feelings of shame or guilt (82.1%).2 Almost 88% of respondents said that they saw a doctor or other clinician while being trafficked, but their clinicians were unable to recognize the signs of trafficking. Part of the challenge is that many children and adolescents are not comfortable discussing their situations with clinicians because they may struggle with shame and guilt. Their traffickers also might have convinced them that they are criminals, not victims. These patients also may have an overwhelming fear of their trafficker, being reported to child welfare authorities, being arrested, being deported, or having their traffickers retaliate against their families. Gaining the trust of a patient who is being trafficked is critical, but not easy, because children may be skeptical of a clinician’s promise of confidentiality.

Some signs of trafficking overlap with the psychiatric presentations with which we are more familiar. These patients may abuse drugs or alcohol as means of escape or because their traffickers force them to use substances.2 They may show symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and may be disoriented. Other indicators may be more telling, such as if a child or adolescent describes:

- having no control of their schedules or forms of identification

- having to work excessively long hours, often to pay off an overwhelming debt

- having high security measures installed in their place of residence (such as cameras or barred windows).

Continue to: Also, they may be...

Also, they may be dressed inappropriately for the weather.

We should be concerned when patients’ responses seem coached, if they say they are isolated from their family and community, or if they are submissive or overly timid. In addition, our suspicions should be raised if an accompanying adult guardian insists on sitting in on the appointment or translating for the child. In such instances, we may request that the guardian remain in the waiting area during the appointment so the child will have the opportunity to speak freely.2

How to help a suspected victim

Several local and national organizations help trafficking victims. These organizations provide educational materials and training opportunities for clinicians, as well as direct support for victims. The Homeland Security Blue Campaign advises against confronting a suspected trafficker directly and encourages clinicians to instead report suspected cases to 1-866-347-2423.3

Clinicians can better help children who are trafficked by taking the following 5 steps:

- Learn about the risk factors and signs of child trafficking.

- Post the National Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888) in your waiting room.

- Determine if your patient is in danger and needs to be moved to a safe place.

- Connect the patient to social service agencies that can provide financial support and housing assistance so he/she doesn’t feel trapped by financial burdens.

- Work to rebuild their emotional and physical well-being while treating depression, PTSD, substance abuse, or any other mental illness.

1. National Center for Missing and Exploited Childr en. Missing children, state care, and child sex trafficking. http://www.missingkids.com/content/dam/missingkids/pdfs/publications/missingchildrenstatecare.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2019.

2. Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23(1):61-91.

3. Blue Campaign. Identify a victim. US Department of Homeland Security. https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/identify-victim. Accessed June 10, 2019.

1. National Center for Missing and Exploited Childr en. Missing children, state care, and child sex trafficking. http://www.missingkids.com/content/dam/missingkids/pdfs/publications/missingchildrenstatecare.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2019.

2. Lederer LJ, Wetzel CA. The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities. Ann Health Law. 2014;23(1):61-91.

3. Blue Campaign. Identify a victim. US Department of Homeland Security. https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/identify-victim. Accessed June 10, 2019.

Hypersomnolence: Unraveling the causes

Establishing a diagnosis of hypersomnia—recurrent episodes of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) or prolonged nighttime sleep—requires a stepwise assessment. We describe a complex case of an older adult who presented with multiple potential causes of hypersomnolence.

CASE REPORT

Persistent daytime sleepiness

Mr. W, age 63, is a veteran with a medical history significant for severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), insomnia, restless leg syndrome, hypertension, and major depressive disorder. He reported long-standing EDS that was causing functional and social impairment. Mr. W’s EDS persisted despite the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. A download of his CPAP compliance summary revealed both optimal CPAP adherence (>7-hour usage for 95%) and control of OSA (Apnea Hypopnea Index <5). His Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score remained at 20 out of 24. Another clinician had previously prescribed modafinil to treat Mr. W’s EDS, which was presumed to be related to sleep apnea. At the time of assessment, Mr. W was taking modafinil, 200 mg every morning, without significant relief of his daytime somnolence. Laboratory results revealed normal liver function tests, electrolytes, and hormonal levels, and a urine toxicology was negative. Mr. W said he constantly rubbed his legs to ease his bilateral leg movement. He reported both sensory and motor components, and relief with movement and absence of sensations in the morning.1 Gabapentin was initiated and titrated to a therapeutic dose to stabilize these symptoms.

Further contemplation led the treating clinician to investigate sleep deprivation or insomnia as potential causes of Mr. W’s daytime somnolence. Mr. W also reported occasional insomnia symptoms. To probe for the culprit of daytime sleepiness, actigraphy wrist monitoring was performed and showed no persistent insomnia or circadian rhythm disturbances.2 Medication reconciliation revealed Mr. W was taking 2 medications (fluoxetine and modafinil) that made him alert, but because he took these in the morning, it was unlikely that they were affecting his sleep. Upon review of his sleep habits, Mr. W’s naps were rare and unrefreshing during the day and he was not drinking excessive amounts of caffeinated beverages.

The diagnostic uncertainty led the treating clinician to order a polysomnography sleep study (PSG) with Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), which revealed a mean sleep latency of 4.1 minutes with no rapid eye movement (REM) periods during his PSG nor next-day napping.3 The PSG showed sleep fragmentation with a sleep efficiency of 90%. The results indicated residual sleepiness secondary to OSA.

Next, the clinician prescribed dextroamphetamine, 25 mg/d, which lowered Mr. W’s ESS score by 2 points (18 out of 24). The clinician presumed that if the stimulant worked, the diagnosis would more likely fit the criteria for residual sleepiness from OSA, rather than idiopathic hypersomnia (IH). Due to a lack of efficacy and adverse effects, the patient was tapered off this medication.

Mr. W reported that he experienced sleepiness during his service in the military at age 23. He also said he did not feel refreshed if he napped during the day.

To address the hypersomnia, he was prescribed off-label sodium oxybate. Sodium oxybate was efficacious and well tolerated; it was slowly titrated up to 9 g/d. After taking sodium oxybate for 2 months, Mr. W’s ESS score diminished to 6. Currently, he reports no functional impairment. A repeat actigraphy showed minimal sleep fragmentation and a strong normal circadian rhythm.

Continue to: Identifying hypersomnia

Identifying hypersomnia

Idiopathic hypersomnia should be considered when a patient’s excessive sleep or EDS are not better explained by another sleep disorder, other medical or psychiatric disorders, or the use of illicit drugs or medications.4 Idiopathic hypersomnia is characterized by EDS that occurs in the absence of cataplexy and is accompanied by no more than 1 sleep-onset REM (SOREM) period on an MSLT and the preceding PSG combined. The differential diagnosis includes narcolepsy, sleep apnea, and

In IH, evidence of hypersomnia must be demonstrated by an MSLT showing a mean sleep latency of <8 minutes or by PSG or wrist actigraphy showing a total 24-hour sleep time of >660 minutes.4 A prolonged and severe form of sleep inertia, consisting of prolonged difficulty waking up with repeated returns to sleep, irritability, automatic behavior, and confusion, often occurs in IH but is not pathognomonic.4

Naps are long—often 60 minutes—and described as unrefreshing by 46% to 78% of patients.4 Sleep efficiency on polysomnography is usually high (mean 90% to 94%). Self-reported total sleep time is longer than in controls and is >10 hours in at least 30% of patients.4 Unfortunately, symptoms and certain objective findings of IH are not unique to the disorder and are considered ubiquitous.

For Mr. W, a diagnosis of narcolepsy was unlikely due to his MSLT results. Patients with narcolepsy have cataplexy (REM dissociation) and/or at least 2 SOREM periods on MLST, or at least 1 SOREM period on MLST in conjunction with a SOREM on the preceding PSG,4 which Mr. W did not exhibit. Patients with narcolepsy typically take refreshing naps lasting 15 to 30 minutes. Although not unique to narcolepsy, common findings include hypnagogic hallucinations and sleep paralysis. Patients with narcolepsy typically do not have sleep inertia but, when seemingly awake, have lapses in vigilance sometimes in combination with automatic behavior, such as writing gibberish or interrupting a conversation with a completely different topic. Another characteristic PSG finding is moderate to severe sleep fragmentation, which may be due to associated periodic limb movements or instability in sleep/wake transitions.5 Mr. W had no history of traumatic brain injury that would suggest hypersomnolence secondary to a brain injury.

Among medical conditions, OSA is the predominant cause of EDS, but this, too, was unlikely for Mr. W because the CPAP therapy reports indicated excellent chronic use and effect. His apnea/hypopnea index was low, and the lowest oxygen saturation recorded on his pre-MSLT PSG using CPAP was 93%. Subjectively, Mr. W reported no choking, gasping, or snoring while receiving CPAP therapy.

Continue to: Restless leg syndrome...

Restless leg syndrome was excluded because after receiving gabapentin, both Mr. W and his wife reported improvement in his leg movements.

Although patients with mood disorders such as depression have normal MSLT results, Mr. W reported no excessive time lying in bed awake, which patients with depression often describe as fatigue and sleepiness. In addition, Mr. W’s score on the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale indicated he was not depressed.

Mr. W’s clinician prescribed off-label sodium oxybate to address his EDS. Its potential benefit in this case may be related to its activity on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) receptors and its effects in prolonging slow-wave sleep, which has restorative properties. This treatment’s effectiveness in this patient was surprising and without precedent. Because the causes of IH often are not precisely defined, we do not recommend administering a trial of this medication without stepwise exclusion of other causes of sleepiness as demonstrated in Pagel’s algorithm “Diagnosis and Management of Conditions That Cause Excessive Daytime Sleepiness,”6 available at www.aafp.org/afp/2009/0301/p391.html.

1. Kallweit U, Siccoli MM, Poryazova R, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in idiopathic restless legs syndrome: characteristics and evolution under dopaminergic treatment. Eur Neurol. 2009;62(3):176-179.

2. Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139(6):1514-1527.

3. Carskadon MA. Guidelines for the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9(4):519-524.

4. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

5. Bahammam A. Periodic leg movements in narcolepsy patients: impact on sleep architecture. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115(5):351-355.

6. Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391-396.

Establishing a diagnosis of hypersomnia—recurrent episodes of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) or prolonged nighttime sleep—requires a stepwise assessment. We describe a complex case of an older adult who presented with multiple potential causes of hypersomnolence.

CASE REPORT

Persistent daytime sleepiness

Mr. W, age 63, is a veteran with a medical history significant for severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), insomnia, restless leg syndrome, hypertension, and major depressive disorder. He reported long-standing EDS that was causing functional and social impairment. Mr. W’s EDS persisted despite the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. A download of his CPAP compliance summary revealed both optimal CPAP adherence (>7-hour usage for 95%) and control of OSA (Apnea Hypopnea Index <5). His Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score remained at 20 out of 24. Another clinician had previously prescribed modafinil to treat Mr. W’s EDS, which was presumed to be related to sleep apnea. At the time of assessment, Mr. W was taking modafinil, 200 mg every morning, without significant relief of his daytime somnolence. Laboratory results revealed normal liver function tests, electrolytes, and hormonal levels, and a urine toxicology was negative. Mr. W said he constantly rubbed his legs to ease his bilateral leg movement. He reported both sensory and motor components, and relief with movement and absence of sensations in the morning.1 Gabapentin was initiated and titrated to a therapeutic dose to stabilize these symptoms.

Further contemplation led the treating clinician to investigate sleep deprivation or insomnia as potential causes of Mr. W’s daytime somnolence. Mr. W also reported occasional insomnia symptoms. To probe for the culprit of daytime sleepiness, actigraphy wrist monitoring was performed and showed no persistent insomnia or circadian rhythm disturbances.2 Medication reconciliation revealed Mr. W was taking 2 medications (fluoxetine and modafinil) that made him alert, but because he took these in the morning, it was unlikely that they were affecting his sleep. Upon review of his sleep habits, Mr. W’s naps were rare and unrefreshing during the day and he was not drinking excessive amounts of caffeinated beverages.

The diagnostic uncertainty led the treating clinician to order a polysomnography sleep study (PSG) with Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), which revealed a mean sleep latency of 4.1 minutes with no rapid eye movement (REM) periods during his PSG nor next-day napping.3 The PSG showed sleep fragmentation with a sleep efficiency of 90%. The results indicated residual sleepiness secondary to OSA.

Next, the clinician prescribed dextroamphetamine, 25 mg/d, which lowered Mr. W’s ESS score by 2 points (18 out of 24). The clinician presumed that if the stimulant worked, the diagnosis would more likely fit the criteria for residual sleepiness from OSA, rather than idiopathic hypersomnia (IH). Due to a lack of efficacy and adverse effects, the patient was tapered off this medication.

Mr. W reported that he experienced sleepiness during his service in the military at age 23. He also said he did not feel refreshed if he napped during the day.

To address the hypersomnia, he was prescribed off-label sodium oxybate. Sodium oxybate was efficacious and well tolerated; it was slowly titrated up to 9 g/d. After taking sodium oxybate for 2 months, Mr. W’s ESS score diminished to 6. Currently, he reports no functional impairment. A repeat actigraphy showed minimal sleep fragmentation and a strong normal circadian rhythm.

Continue to: Identifying hypersomnia

Identifying hypersomnia

Idiopathic hypersomnia should be considered when a patient’s excessive sleep or EDS are not better explained by another sleep disorder, other medical or psychiatric disorders, or the use of illicit drugs or medications.4 Idiopathic hypersomnia is characterized by EDS that occurs in the absence of cataplexy and is accompanied by no more than 1 sleep-onset REM (SOREM) period on an MSLT and the preceding PSG combined. The differential diagnosis includes narcolepsy, sleep apnea, and

In IH, evidence of hypersomnia must be demonstrated by an MSLT showing a mean sleep latency of <8 minutes or by PSG or wrist actigraphy showing a total 24-hour sleep time of >660 minutes.4 A prolonged and severe form of sleep inertia, consisting of prolonged difficulty waking up with repeated returns to sleep, irritability, automatic behavior, and confusion, often occurs in IH but is not pathognomonic.4

Naps are long—often 60 minutes—and described as unrefreshing by 46% to 78% of patients.4 Sleep efficiency on polysomnography is usually high (mean 90% to 94%). Self-reported total sleep time is longer than in controls and is >10 hours in at least 30% of patients.4 Unfortunately, symptoms and certain objective findings of IH are not unique to the disorder and are considered ubiquitous.

For Mr. W, a diagnosis of narcolepsy was unlikely due to his MSLT results. Patients with narcolepsy have cataplexy (REM dissociation) and/or at least 2 SOREM periods on MLST, or at least 1 SOREM period on MLST in conjunction with a SOREM on the preceding PSG,4 which Mr. W did not exhibit. Patients with narcolepsy typically take refreshing naps lasting 15 to 30 minutes. Although not unique to narcolepsy, common findings include hypnagogic hallucinations and sleep paralysis. Patients with narcolepsy typically do not have sleep inertia but, when seemingly awake, have lapses in vigilance sometimes in combination with automatic behavior, such as writing gibberish or interrupting a conversation with a completely different topic. Another characteristic PSG finding is moderate to severe sleep fragmentation, which may be due to associated periodic limb movements or instability in sleep/wake transitions.5 Mr. W had no history of traumatic brain injury that would suggest hypersomnolence secondary to a brain injury.

Among medical conditions, OSA is the predominant cause of EDS, but this, too, was unlikely for Mr. W because the CPAP therapy reports indicated excellent chronic use and effect. His apnea/hypopnea index was low, and the lowest oxygen saturation recorded on his pre-MSLT PSG using CPAP was 93%. Subjectively, Mr. W reported no choking, gasping, or snoring while receiving CPAP therapy.

Continue to: Restless leg syndrome...

Restless leg syndrome was excluded because after receiving gabapentin, both Mr. W and his wife reported improvement in his leg movements.

Although patients with mood disorders such as depression have normal MSLT results, Mr. W reported no excessive time lying in bed awake, which patients with depression often describe as fatigue and sleepiness. In addition, Mr. W’s score on the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale indicated he was not depressed.

Mr. W’s clinician prescribed off-label sodium oxybate to address his EDS. Its potential benefit in this case may be related to its activity on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) receptors and its effects in prolonging slow-wave sleep, which has restorative properties. This treatment’s effectiveness in this patient was surprising and without precedent. Because the causes of IH often are not precisely defined, we do not recommend administering a trial of this medication without stepwise exclusion of other causes of sleepiness as demonstrated in Pagel’s algorithm “Diagnosis and Management of Conditions That Cause Excessive Daytime Sleepiness,”6 available at www.aafp.org/afp/2009/0301/p391.html.

Establishing a diagnosis of hypersomnia—recurrent episodes of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) or prolonged nighttime sleep—requires a stepwise assessment. We describe a complex case of an older adult who presented with multiple potential causes of hypersomnolence.

CASE REPORT

Persistent daytime sleepiness

Mr. W, age 63, is a veteran with a medical history significant for severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), insomnia, restless leg syndrome, hypertension, and major depressive disorder. He reported long-standing EDS that was causing functional and social impairment. Mr. W’s EDS persisted despite the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. A download of his CPAP compliance summary revealed both optimal CPAP adherence (>7-hour usage for 95%) and control of OSA (Apnea Hypopnea Index <5). His Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score remained at 20 out of 24. Another clinician had previously prescribed modafinil to treat Mr. W’s EDS, which was presumed to be related to sleep apnea. At the time of assessment, Mr. W was taking modafinil, 200 mg every morning, without significant relief of his daytime somnolence. Laboratory results revealed normal liver function tests, electrolytes, and hormonal levels, and a urine toxicology was negative. Mr. W said he constantly rubbed his legs to ease his bilateral leg movement. He reported both sensory and motor components, and relief with movement and absence of sensations in the morning.1 Gabapentin was initiated and titrated to a therapeutic dose to stabilize these symptoms.

Further contemplation led the treating clinician to investigate sleep deprivation or insomnia as potential causes of Mr. W’s daytime somnolence. Mr. W also reported occasional insomnia symptoms. To probe for the culprit of daytime sleepiness, actigraphy wrist monitoring was performed and showed no persistent insomnia or circadian rhythm disturbances.2 Medication reconciliation revealed Mr. W was taking 2 medications (fluoxetine and modafinil) that made him alert, but because he took these in the morning, it was unlikely that they were affecting his sleep. Upon review of his sleep habits, Mr. W’s naps were rare and unrefreshing during the day and he was not drinking excessive amounts of caffeinated beverages.

The diagnostic uncertainty led the treating clinician to order a polysomnography sleep study (PSG) with Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), which revealed a mean sleep latency of 4.1 minutes with no rapid eye movement (REM) periods during his PSG nor next-day napping.3 The PSG showed sleep fragmentation with a sleep efficiency of 90%. The results indicated residual sleepiness secondary to OSA.

Next, the clinician prescribed dextroamphetamine, 25 mg/d, which lowered Mr. W’s ESS score by 2 points (18 out of 24). The clinician presumed that if the stimulant worked, the diagnosis would more likely fit the criteria for residual sleepiness from OSA, rather than idiopathic hypersomnia (IH). Due to a lack of efficacy and adverse effects, the patient was tapered off this medication.

Mr. W reported that he experienced sleepiness during his service in the military at age 23. He also said he did not feel refreshed if he napped during the day.

To address the hypersomnia, he was prescribed off-label sodium oxybate. Sodium oxybate was efficacious and well tolerated; it was slowly titrated up to 9 g/d. After taking sodium oxybate for 2 months, Mr. W’s ESS score diminished to 6. Currently, he reports no functional impairment. A repeat actigraphy showed minimal sleep fragmentation and a strong normal circadian rhythm.

Continue to: Identifying hypersomnia

Identifying hypersomnia

Idiopathic hypersomnia should be considered when a patient’s excessive sleep or EDS are not better explained by another sleep disorder, other medical or psychiatric disorders, or the use of illicit drugs or medications.4 Idiopathic hypersomnia is characterized by EDS that occurs in the absence of cataplexy and is accompanied by no more than 1 sleep-onset REM (SOREM) period on an MSLT and the preceding PSG combined. The differential diagnosis includes narcolepsy, sleep apnea, and

In IH, evidence of hypersomnia must be demonstrated by an MSLT showing a mean sleep latency of <8 minutes or by PSG or wrist actigraphy showing a total 24-hour sleep time of >660 minutes.4 A prolonged and severe form of sleep inertia, consisting of prolonged difficulty waking up with repeated returns to sleep, irritability, automatic behavior, and confusion, often occurs in IH but is not pathognomonic.4

Naps are long—often 60 minutes—and described as unrefreshing by 46% to 78% of patients.4 Sleep efficiency on polysomnography is usually high (mean 90% to 94%). Self-reported total sleep time is longer than in controls and is >10 hours in at least 30% of patients.4 Unfortunately, symptoms and certain objective findings of IH are not unique to the disorder and are considered ubiquitous.

For Mr. W, a diagnosis of narcolepsy was unlikely due to his MSLT results. Patients with narcolepsy have cataplexy (REM dissociation) and/or at least 2 SOREM periods on MLST, or at least 1 SOREM period on MLST in conjunction with a SOREM on the preceding PSG,4 which Mr. W did not exhibit. Patients with narcolepsy typically take refreshing naps lasting 15 to 30 minutes. Although not unique to narcolepsy, common findings include hypnagogic hallucinations and sleep paralysis. Patients with narcolepsy typically do not have sleep inertia but, when seemingly awake, have lapses in vigilance sometimes in combination with automatic behavior, such as writing gibberish or interrupting a conversation with a completely different topic. Another characteristic PSG finding is moderate to severe sleep fragmentation, which may be due to associated periodic limb movements or instability in sleep/wake transitions.5 Mr. W had no history of traumatic brain injury that would suggest hypersomnolence secondary to a brain injury.

Among medical conditions, OSA is the predominant cause of EDS, but this, too, was unlikely for Mr. W because the CPAP therapy reports indicated excellent chronic use and effect. His apnea/hypopnea index was low, and the lowest oxygen saturation recorded on his pre-MSLT PSG using CPAP was 93%. Subjectively, Mr. W reported no choking, gasping, or snoring while receiving CPAP therapy.

Continue to: Restless leg syndrome...

Restless leg syndrome was excluded because after receiving gabapentin, both Mr. W and his wife reported improvement in his leg movements.

Although patients with mood disorders such as depression have normal MSLT results, Mr. W reported no excessive time lying in bed awake, which patients with depression often describe as fatigue and sleepiness. In addition, Mr. W’s score on the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale indicated he was not depressed.

Mr. W’s clinician prescribed off-label sodium oxybate to address his EDS. Its potential benefit in this case may be related to its activity on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) receptors and its effects in prolonging slow-wave sleep, which has restorative properties. This treatment’s effectiveness in this patient was surprising and without precedent. Because the causes of IH often are not precisely defined, we do not recommend administering a trial of this medication without stepwise exclusion of other causes of sleepiness as demonstrated in Pagel’s algorithm “Diagnosis and Management of Conditions That Cause Excessive Daytime Sleepiness,”6 available at www.aafp.org/afp/2009/0301/p391.html.

1. Kallweit U, Siccoli MM, Poryazova R, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in idiopathic restless legs syndrome: characteristics and evolution under dopaminergic treatment. Eur Neurol. 2009;62(3):176-179.

2. Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139(6):1514-1527.

3. Carskadon MA. Guidelines for the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9(4):519-524.

4. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

5. Bahammam A. Periodic leg movements in narcolepsy patients: impact on sleep architecture. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115(5):351-355.

6. Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391-396.

1. Kallweit U, Siccoli MM, Poryazova R, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in idiopathic restless legs syndrome: characteristics and evolution under dopaminergic treatment. Eur Neurol. 2009;62(3):176-179.

2. Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139(6):1514-1527.

3. Carskadon MA. Guidelines for the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9(4):519-524.

4. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

5. Bahammam A. Periodic leg movements in narcolepsy patients: impact on sleep architecture. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115(5):351-355.

6. Pagel JF. Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(5):391-396.

Polypharmacy: When might it make sense?

Polypharmacy is often defined as the simultaneous prescription of multiple medications (usually ≥5) to a single patient for a single condition or multiple conditions.1 Patients with psychiatric illnesses may easily be prescribed multiple psychotropic medications regardless of how many other medications they may already take for nonpsychiatric comorbidities. According to 2011-2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, 11.9% of the US population used ≥5 medications in the past 30 days.2 Risks of polypharmacy include higher rates of adverse effects as well as treatment noncompliance.3

There are, however, many patients for whom a combination of psychotropic agents can be beneficial. It is important to carefully assess your patient’s regimen, and to document the rationale for prescribing multiple medications. Here I describe some factors that can help you to determine whether a multi-medication regimen might be warranted for your patient.

Accepted medication pairings. This describes a medication combination that has been recognized as generally safe and may provide more benefits than either single agent alone. Examples of clinically accepted medication combinations include4,5:

- a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) plus bupropion

- an SSRI or SNRI plus mirtazapine

- ziprasidone as an adjunct to valproate or lithium for treating bipolar disorder

- aripiprazole as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD).

Comorbid diagnoses. Each of a patient’s psychiatric comorbidities may require a different medication to address specific symptoms.3 Psychiatric comorbidities that might be appropriate for multiple medications include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder, MDD and generalized anxiety disorder, and a mood disorder and a substance use disorder.

Treatment resistance. The patient has demonstrated poor or no response to prior trials with simpler medication regimens, and/or there is a history of decompensation or hospitalization when medications were pared down.

Severe acute symptoms. The patient has been experiencing acute symptoms that do not respond to one medication class. For example, a patient with bipolar disorder who has acute mania and psychosis may require significant doses of both a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic.

Amelioration of adverse effects. One medication may be prescribed to address the adverse effects of other medications. For example, propranolol may be added to address akathisia from aripiprazole or tremors from lithium. In these cases, it is important to determine if the medication that’s causing adverse effects continues to provide benefits, in order to justify continuing it as well as adding a new agent.3

Continue to: After reviewing...

After reviewing your patient’s medication regimen, if one of these scenarios does not clearly exist, consider a “deprescribing” approach—reducing or stopping medications—to address unnecessary and potentially detrimental polypharmacy. For more information on dep

1. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230.

Polypharmacy is often defined as the simultaneous prescription of multiple medications (usually ≥5) to a single patient for a single condition or multiple conditions.1 Patients with psychiatric illnesses may easily be prescribed multiple psychotropic medications regardless of how many other medications they may already take for nonpsychiatric comorbidities. According to 2011-2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, 11.9% of the US population used ≥5 medications in the past 30 days.2 Risks of polypharmacy include higher rates of adverse effects as well as treatment noncompliance.3

There are, however, many patients for whom a combination of psychotropic agents can be beneficial. It is important to carefully assess your patient’s regimen, and to document the rationale for prescribing multiple medications. Here I describe some factors that can help you to determine whether a multi-medication regimen might be warranted for your patient.

Accepted medication pairings. This describes a medication combination that has been recognized as generally safe and may provide more benefits than either single agent alone. Examples of clinically accepted medication combinations include4,5:

- a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) plus bupropion

- an SSRI or SNRI plus mirtazapine

- ziprasidone as an adjunct to valproate or lithium for treating bipolar disorder

- aripiprazole as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD).

Comorbid diagnoses. Each of a patient’s psychiatric comorbidities may require a different medication to address specific symptoms.3 Psychiatric comorbidities that might be appropriate for multiple medications include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder, MDD and generalized anxiety disorder, and a mood disorder and a substance use disorder.

Treatment resistance. The patient has demonstrated poor or no response to prior trials with simpler medication regimens, and/or there is a history of decompensation or hospitalization when medications were pared down.

Severe acute symptoms. The patient has been experiencing acute symptoms that do not respond to one medication class. For example, a patient with bipolar disorder who has acute mania and psychosis may require significant doses of both a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic.

Amelioration of adverse effects. One medication may be prescribed to address the adverse effects of other medications. For example, propranolol may be added to address akathisia from aripiprazole or tremors from lithium. In these cases, it is important to determine if the medication that’s causing adverse effects continues to provide benefits, in order to justify continuing it as well as adding a new agent.3

Continue to: After reviewing...

After reviewing your patient’s medication regimen, if one of these scenarios does not clearly exist, consider a “deprescribing” approach—reducing or stopping medications—to address unnecessary and potentially detrimental polypharmacy. For more information on dep

Polypharmacy is often defined as the simultaneous prescription of multiple medications (usually ≥5) to a single patient for a single condition or multiple conditions.1 Patients with psychiatric illnesses may easily be prescribed multiple psychotropic medications regardless of how many other medications they may already take for nonpsychiatric comorbidities. According to 2011-2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, 11.9% of the US population used ≥5 medications in the past 30 days.2 Risks of polypharmacy include higher rates of adverse effects as well as treatment noncompliance.3

There are, however, many patients for whom a combination of psychotropic agents can be beneficial. It is important to carefully assess your patient’s regimen, and to document the rationale for prescribing multiple medications. Here I describe some factors that can help you to determine whether a multi-medication regimen might be warranted for your patient.

Accepted medication pairings. This describes a medication combination that has been recognized as generally safe and may provide more benefits than either single agent alone. Examples of clinically accepted medication combinations include4,5:

- a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) plus bupropion

- an SSRI or SNRI plus mirtazapine

- ziprasidone as an adjunct to valproate or lithium for treating bipolar disorder

- aripiprazole as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD).

Comorbid diagnoses. Each of a patient’s psychiatric comorbidities may require a different medication to address specific symptoms.3 Psychiatric comorbidities that might be appropriate for multiple medications include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder, MDD and generalized anxiety disorder, and a mood disorder and a substance use disorder.

Treatment resistance. The patient has demonstrated poor or no response to prior trials with simpler medication regimens, and/or there is a history of decompensation or hospitalization when medications were pared down.

Severe acute symptoms. The patient has been experiencing acute symptoms that do not respond to one medication class. For example, a patient with bipolar disorder who has acute mania and psychosis may require significant doses of both a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic.

Amelioration of adverse effects. One medication may be prescribed to address the adverse effects of other medications. For example, propranolol may be added to address akathisia from aripiprazole or tremors from lithium. In these cases, it is important to determine if the medication that’s causing adverse effects continues to provide benefits, in order to justify continuing it as well as adding a new agent.3

Continue to: After reviewing...

After reviewing your patient’s medication regimen, if one of these scenarios does not clearly exist, consider a “deprescribing” approach—reducing or stopping medications—to address unnecessary and potentially detrimental polypharmacy. For more information on dep

1. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230.

1. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230.

SPIRITT: What does ‘spirituality’ mean?

Both patients and clinicians alike have shown increasing interest in spirituality as a component of physical and mental well-being.1 However, there’s no clear consensus on what spirituality actually means. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it “affecting the spirit, relating to sacred matters, concerned with religious issues.”2 Spirituality is sometimes defined in broadly secular terms, such as the feeling of “being part of something greater than ourselves,” or in connection to ideas rooted in a specific belief system, such as “aligning oneself with the Will of God.”

I prefer to think of the word “spiritual” as encompassing multiple practices and beliefs that have the common goal of helping us deepen our capacity for self-awareness, joy, compassion, love, freedom, justice, and mutual cooperation, not only for our own benefit, but also to create a better world. To help clinicians better understand what the term spirituality implies, whether for themselves or for their patients, I offer the acronym SPIRITT to describe core components of varied spiritual perspectives, beliefs, and practices.

Sacred. Considering certain aspects of life, time, or place as non-ordinary and worthy of reverence and awe.

Presence. Cultivating an inner presence that is open, accepting, compassionate, and loving toward others. During a spiritual experience, some may feel embraced in this way by a presence outside of themselves, such as an encounter with a spiritual teacher or an experience of feeling held lovingly by a transcendent power.

Interconnection. Understanding that we are not separate entities but are interconnected beings existing in interdependent unity, starting with our families and extending out universally. According to this perspective, harming anything or anyone is doing harm to ourself.

Rest. Taking a Sabbath or unplugging. Dedicating time each week for resting your mind and body. Spending quality time with family. Decreasing excessive stimulation and loosening the grip of consumerism.

Introspection. Looking inwardly. Eastern traditions emphasize deepening self-awareness through mindful meditation practices, while Western traditions include taking a personal inventory through self-examination or confessional practices.

Continue to: Traditions

Traditions. Studying sacred texts, participating in communal prayer, meditating, or engaging in rituals. This requires sorting through outmoded beliefs and ways of thinking while updating beliefs that are compatible with our lived experiences.

Transcendence. Experiencing moments, whether through nature, music, dance, ritual, prayer, art, etc., in which the narrow sense of being a separate self fades away and there is a deeper sense of a larger connection and belonging that is transpersonal, timeless, and expansive.

The components of SPIRITT have helped me to think about and pursue the physical, emotional, and social benefits of adopting a spiritual practice for my well-being as well as for the benefit of my patients.

1. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29(3):19-26.

2. Spiritual. Miriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spiritual. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Both patients and clinicians alike have shown increasing interest in spirituality as a component of physical and mental well-being.1 However, there’s no clear consensus on what spirituality actually means. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it “affecting the spirit, relating to sacred matters, concerned with religious issues.”2 Spirituality is sometimes defined in broadly secular terms, such as the feeling of “being part of something greater than ourselves,” or in connection to ideas rooted in a specific belief system, such as “aligning oneself with the Will of God.”

I prefer to think of the word “spiritual” as encompassing multiple practices and beliefs that have the common goal of helping us deepen our capacity for self-awareness, joy, compassion, love, freedom, justice, and mutual cooperation, not only for our own benefit, but also to create a better world. To help clinicians better understand what the term spirituality implies, whether for themselves or for their patients, I offer the acronym SPIRITT to describe core components of varied spiritual perspectives, beliefs, and practices.

Sacred. Considering certain aspects of life, time, or place as non-ordinary and worthy of reverence and awe.

Presence. Cultivating an inner presence that is open, accepting, compassionate, and loving toward others. During a spiritual experience, some may feel embraced in this way by a presence outside of themselves, such as an encounter with a spiritual teacher or an experience of feeling held lovingly by a transcendent power.

Interconnection. Understanding that we are not separate entities but are interconnected beings existing in interdependent unity, starting with our families and extending out universally. According to this perspective, harming anything or anyone is doing harm to ourself.

Rest. Taking a Sabbath or unplugging. Dedicating time each week for resting your mind and body. Spending quality time with family. Decreasing excessive stimulation and loosening the grip of consumerism.

Introspection. Looking inwardly. Eastern traditions emphasize deepening self-awareness through mindful meditation practices, while Western traditions include taking a personal inventory through self-examination or confessional practices.

Continue to: Traditions

Traditions. Studying sacred texts, participating in communal prayer, meditating, or engaging in rituals. This requires sorting through outmoded beliefs and ways of thinking while updating beliefs that are compatible with our lived experiences.

Transcendence. Experiencing moments, whether through nature, music, dance, ritual, prayer, art, etc., in which the narrow sense of being a separate self fades away and there is a deeper sense of a larger connection and belonging that is transpersonal, timeless, and expansive.

The components of SPIRITT have helped me to think about and pursue the physical, emotional, and social benefits of adopting a spiritual practice for my well-being as well as for the benefit of my patients.

Both patients and clinicians alike have shown increasing interest in spirituality as a component of physical and mental well-being.1 However, there’s no clear consensus on what spirituality actually means. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it “affecting the spirit, relating to sacred matters, concerned with religious issues.”2 Spirituality is sometimes defined in broadly secular terms, such as the feeling of “being part of something greater than ourselves,” or in connection to ideas rooted in a specific belief system, such as “aligning oneself with the Will of God.”

I prefer to think of the word “spiritual” as encompassing multiple practices and beliefs that have the common goal of helping us deepen our capacity for self-awareness, joy, compassion, love, freedom, justice, and mutual cooperation, not only for our own benefit, but also to create a better world. To help clinicians better understand what the term spirituality implies, whether for themselves or for their patients, I offer the acronym SPIRITT to describe core components of varied spiritual perspectives, beliefs, and practices.

Sacred. Considering certain aspects of life, time, or place as non-ordinary and worthy of reverence and awe.

Presence. Cultivating an inner presence that is open, accepting, compassionate, and loving toward others. During a spiritual experience, some may feel embraced in this way by a presence outside of themselves, such as an encounter with a spiritual teacher or an experience of feeling held lovingly by a transcendent power.

Interconnection. Understanding that we are not separate entities but are interconnected beings existing in interdependent unity, starting with our families and extending out universally. According to this perspective, harming anything or anyone is doing harm to ourself.

Rest. Taking a Sabbath or unplugging. Dedicating time each week for resting your mind and body. Spending quality time with family. Decreasing excessive stimulation and loosening the grip of consumerism.

Introspection. Looking inwardly. Eastern traditions emphasize deepening self-awareness through mindful meditation practices, while Western traditions include taking a personal inventory through self-examination or confessional practices.

Continue to: Traditions

Traditions. Studying sacred texts, participating in communal prayer, meditating, or engaging in rituals. This requires sorting through outmoded beliefs and ways of thinking while updating beliefs that are compatible with our lived experiences.

Transcendence. Experiencing moments, whether through nature, music, dance, ritual, prayer, art, etc., in which the narrow sense of being a separate self fades away and there is a deeper sense of a larger connection and belonging that is transpersonal, timeless, and expansive.

The components of SPIRITT have helped me to think about and pursue the physical, emotional, and social benefits of adopting a spiritual practice for my well-being as well as for the benefit of my patients.

1. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29(3):19-26.

2. Spiritual. Miriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spiritual. Accessed May 9, 2019.

1. Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29(3):19-26.

2. Spiritual. Miriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spiritual. Accessed May 9, 2019.

When your patient is a physician: Overcoming the challenges

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

Physicians’ physical and mental well-being has become a major concern in health care. In the United States, an estimated 300 to 400 physicians die from suicide each year.1 Compared with the general population, the suicide rates for male and female physicians are 1.41 and 2.27 times higher, respectively.2 As psychiatrists, we can play an instrumental role in preserving our colleagues’ mental health. While treating a fellow physician can be rewarding, these situations also can be challenging. Here we describe a few of the challenges of treating physicians, and solutions we can employ to minimize potential pitfalls.

Challenges: How our relationship can affect care

We may view physician-patients as “VIPs” because of their profession, which might lead us to assume they are more knowledgeable than the average patient.1,3 This mindset could result in taking an inadequate history, having an incomplete informed-consent discussion, avoiding or limiting educational discussions, performing an inadequate suicide risk assessment, or underestimating the need for higher levels of care (eg, psychiatric hospitalization).1

We may have difficulty maintaining appropriate professional boundaries due to the relationship (eg, friend, colleague, or mentor) we have established with a physician-patient.3 It may be difficult to establish the usual roles of patient and physician, particularly if we have a professional relationship with a physician-patient that requires routine contact at work. The issue of boundaries can become compounded if there is an emotional component to the relationship, which may make it difficult to discuss sensitive topics.3 A physician-patient may be reluctant to discuss sensitive information due to concerns about the confidentiality of their medical record.3 They also might obtain our personal contact information through work-related networks and use it to contact us about their care.

Solutions: Treat them as you would any other patient

Although physician-patients may have more medical knowledge than other patients, we should avoid showing deference and making assumptions about their knowledge of psychiatric illnesses and treatment. As we would with other patients, we should always1:

- conduct a thorough evaluation

- develop a comprehensive treatment plan

- provide appropriate informed consent

- adequately assess suicide risk.

We should also maintain boundaries as best we can, while understanding that our professional relationships might complicate this.

We should ask our physician-patients if they have been self-prescribing and/or self-treating.1 We shouldn’t shy away from considering inpatient treatment for physician-patients (when clinically indicated) because of our concern that such treatment might jeopardize their ability to practice medicine. Also, to help decrease barriers to and enhance engagement in treatment, consider recommending treatment options that can take place outside of the physician-patient’s work environment.3

Continue to: We should provide...

We should provide the same confidentiality considerations to physician-patients as we do to other patients. However, at times, we may need to break confidentiality for safety concerns or reporting that is required by law. We may have to contact a state licensing board if a physician-patient continues to practice while impaired despite engaging in treatment.1 We should understand the procedures for reporting; have referral resources available for these patients, such as recovering physician programs; and know whom to contact for further counsel, such as risk management or legal teams.1

The best way to provide optimal psychiatric care to a physician colleague is to acknowledge the potential challenges at the onset of treatment, and work collaboratively to avoid the potential pitfalls during the course of treatment.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

1. Fischer-Sanchez D. Risk management considerations when treating fellow physicians. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.7a21. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Racing thoughts: What to consider

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

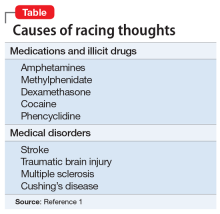

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.