User login

Multicomponent Exercise Program Can Reverse Hospitalization-Associated Functional Decline in Elderly Patients

Study Overview

Objective. To assess the effects of an individualized, multicomponent exercise intervention on the functional status of very elderly patients who were acutely hospitalized compared with those who received usual care.

Design. A single-center, single-blind randomized clinical trial comparing elderly (≥ 75 years old) hospitalized patients who received in-hospital exercise (ie, individualized low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking exercises) versus control (ie, usual care that included physical rehabilitation if needed) interventions. The exercise intervention was adapted from the multicomponent physical exercise program Vivifrail and was supervised and conducted by a fitness specialist in 2 daily (1 morning and 1 evening) sessions lasting 20 minutes for 5 to 7 consecutive days. The morning session consisted of supervised and individualized progressive resistance, balance, and walking exercises. The evening session consisted of functional unsupervised exercises including light weights, extension and flexion of knee and hip, and walking.

Setting and participants. The study was conducted in an acute care unit in a tertiary public hospital in Navarra, Spain, between 1 February 2015 and 30 August 2017. A total of 370 elderly patients undergoing acute care hospitalization were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to receive in-hospital exercise or control intervention. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 75 years, Barthel Index score ≥ 60, and ambulatory with or without assistance.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was change in functional capacity from baseline (beginning of exercise or control intervention) to hospital discharge as assessed by the Barthel Index of independence and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). Secondary outcomes were changes in cognitive capacity (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]) and mood status (Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS]), quality of life (QoL; EuroQol-5D), handgrip strength (dominant hand), incident delirium (Confusion Assessment Method), length of stay (LOS), falls during hospitalization, transfer after discharge, and readmission rate and mortality at 3 months after discharge. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted.

Main results. Of the 370 patients included in the study’s analyses, 209 (56.5%) were women, mean age was 87.3 ± 4.9 years (range, 75-101 years; 130 [35.1%] nonagenarians). The median LOS was 8 days in both groups (interquartile range [IQR], 4 and 4 days, respectively). The median duration of the intervention was 5 days (IQR, 0 days), with 5 ± 1 morning and 4 ± 1 evening sessions in the exercise group. Adherence to the exercise intervention was high (95.8% for morning sessions; 83.4% for evening sessions), and no adverse effects were observed with the intervention.

The in-hospital exercise intervention program yielded significant benefits over usual care in functional outcomes in elderly patients. The exercise group had an increased change in measures of functional capacity compared to the usual care group (ie, Barthel Index, 6.9 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.4-9.5; SPPB score, 2.2 points; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6). Furthermore, acute hospitalization led to an impairment in functional capacity from baseline to discharge in the Barthel Index (−5.0 points; 95% CI, −6.8 to −3.2) in the usual care group. In contrast, exercise intervention reversed this decline and improved functional outcomes as assessed by Barthel Index (1.9 points; 95% CI, 0.2-3.7) and SPPB score (2.4 points; 95% CI, 2.1-2.7).

The beneficial effects of the in-hospital exercise intervention extended to secondary end points indicative of cognitive capacity (MMSE, 1.8 points; 95% CI, 1.3-2.3), mood status (GDS, −2.0 points; 95% CI, −2.5 to −1.6), QoL (EuroQol-5D, 13.2 points; 95% CI, 8.2-18.2), and handgrip strength (2.3 kg; 95% CI, 1.8-2.8) compared to those who received usual care. In contrast, no differences were observed between groups that received exercise intervention and usual care in incident delirium, LOS, falls during hospitalization, transfer after discharge, and 3-month hospital readmission rate and mortality.

Conclusion. An individualized, multicomponent physical exercise program that includes low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking exercises performed during the course of hospitalization (average of 5 days) can reverse functional decline associated with acute hospitalization in very elderly patients. Furthermore, this in-hospital exercise intervention is safe and has a high adherence rate, and thus represents an opportunity to improve quality of care in this vulnerable population.

Commentary

Frail elderly patients are highly susceptible to adverse outcomes of acute hospitalization, including functional decline, disability, nursing home placement, rehospitalization, and mortality.1 Mobility limitation, a major hazard of hospitalization, has been associated with poorer functional recovery and increased vulnerability to these major adverse events after hospital discharge.2-4 Interdisciplinary care models delivered during hospitalization (eg, Geriatric Evaluation Unit, Acute Care for Elders) that emphasize functional independence and provide protocols for exercise and rehabilitation have demonstrated reduced hospital LOS, discharge to nursing home, and mortality, and improved functional status in elderly patients.5-7 Despite this evidence, significant gaps in knowledge exist in understanding whether early implementation of an individualized, multicomponent exercise training program can benefit the oldest old patients who are acutely hospitalized.

This study reported by Martinez-Velilla and colleagues provides an important and timely investigation in examining the effects of an individualized, multicomponent (ie, low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking) in-hospital exercise intervention on functional outcomes of hospitalized octogenarians and nonagenarians. The authors reported that such an intervention, administered 2 sessions per day for 5 to 7 consecutive days, can be safely implemented and reverse functional decline (ie, improvement in Barthel Index and SPPB score over course of hospital stay) typically associated with acute hospitalization in these vulnerable individuals. These findings are particularly significant given the paucity of randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of exercise intervention in preserving functional capacity of geriatric patients in the setting of acute hospitalization. While much more research is needed to facilitate future development of a consensus opinion in this regard, results from this study provide the rationale that implementation of an individualized multicomponent exercise program is feasible and safe and may attenuate functional decline in hospitalized older patients. Finally, the beneficial effects of in-hospital exercise intervention may extend to cognitive capacity, mood status, and QoL—domains that are essential to optimizing patient-centered care in the frailest elderly patients.

The study was well conceived with a number of strengths, including its randomized clinical trial design. In addition, the trial patients were advanced in age (35.1% were nonagenarians), which is particularly important because this is a vulnerable population that is frequently excluded from participation in trials of exercise interventions and because the evidence-base for physical activity guidelines is suboptimal. Moreover, the authors demonstrated that an individualized multicomponent exercise program could be successfully implemented in elderly patients in an acute setting via daily exercise sessions. This test of feasibility is significant in that clinical trials in exercise intervention in geriatrics are commonly performed in nonacute settings in the community, long-term care facilities, or subacute care. The major limitation in this study centers on the generalizability of its findings. It was noted that some patients were not assessed for changes from baseline to discharge on the Barthel Index (6.1%) and SPPB (2.3%) because of their poor condition. The exclusion of the most debilitated patients limits the application of the study’s key findings to the frailest elderly patients, who are most likely to require acute hospital care.

Applications for Clinical Pract

Functional decline is an exceedingly common adverse outcome associated with hospitalization in older patients. While more evidence is needed, early implementation of an individualized, multicomponent exercise regimen during hospitalization may help to prevent functional decline in vulnerable elderly patients.

—Fred Ko, MD, MS

1. Goldwater DS, Dharmarajan K, McEwan BS, Krumholz HM. Is posthospital syndrome a result of hospitalization-induced allostatic overload? J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5).doi:10.12788/jhm.2986.

2. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:219-223.

3. Minnick AF, Mion LC, Johnson ME, et al. Prevalence and variation of physical restraint use in acute care settings in the US. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:30-37.

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Sinoff G et al. Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:266-273.

5. Rubenstein LZ, et al. Effectiveness of a geriatric evaluation unit. A randomized clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1664-1670.

6. Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1338-1344.

7. de Morton NA, Keating JL, Jeffs K. Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD005955.

Study Overview

Objective. To assess the effects of an individualized, multicomponent exercise intervention on the functional status of very elderly patients who were acutely hospitalized compared with those who received usual care.

Design. A single-center, single-blind randomized clinical trial comparing elderly (≥ 75 years old) hospitalized patients who received in-hospital exercise (ie, individualized low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking exercises) versus control (ie, usual care that included physical rehabilitation if needed) interventions. The exercise intervention was adapted from the multicomponent physical exercise program Vivifrail and was supervised and conducted by a fitness specialist in 2 daily (1 morning and 1 evening) sessions lasting 20 minutes for 5 to 7 consecutive days. The morning session consisted of supervised and individualized progressive resistance, balance, and walking exercises. The evening session consisted of functional unsupervised exercises including light weights, extension and flexion of knee and hip, and walking.

Setting and participants. The study was conducted in an acute care unit in a tertiary public hospital in Navarra, Spain, between 1 February 2015 and 30 August 2017. A total of 370 elderly patients undergoing acute care hospitalization were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to receive in-hospital exercise or control intervention. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 75 years, Barthel Index score ≥ 60, and ambulatory with or without assistance.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was change in functional capacity from baseline (beginning of exercise or control intervention) to hospital discharge as assessed by the Barthel Index of independence and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). Secondary outcomes were changes in cognitive capacity (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]) and mood status (Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS]), quality of life (QoL; EuroQol-5D), handgrip strength (dominant hand), incident delirium (Confusion Assessment Method), length of stay (LOS), falls during hospitalization, transfer after discharge, and readmission rate and mortality at 3 months after discharge. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted.

Main results. Of the 370 patients included in the study’s analyses, 209 (56.5%) were women, mean age was 87.3 ± 4.9 years (range, 75-101 years; 130 [35.1%] nonagenarians). The median LOS was 8 days in both groups (interquartile range [IQR], 4 and 4 days, respectively). The median duration of the intervention was 5 days (IQR, 0 days), with 5 ± 1 morning and 4 ± 1 evening sessions in the exercise group. Adherence to the exercise intervention was high (95.8% for morning sessions; 83.4% for evening sessions), and no adverse effects were observed with the intervention.

The in-hospital exercise intervention program yielded significant benefits over usual care in functional outcomes in elderly patients. The exercise group had an increased change in measures of functional capacity compared to the usual care group (ie, Barthel Index, 6.9 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.4-9.5; SPPB score, 2.2 points; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6). Furthermore, acute hospitalization led to an impairment in functional capacity from baseline to discharge in the Barthel Index (−5.0 points; 95% CI, −6.8 to −3.2) in the usual care group. In contrast, exercise intervention reversed this decline and improved functional outcomes as assessed by Barthel Index (1.9 points; 95% CI, 0.2-3.7) and SPPB score (2.4 points; 95% CI, 2.1-2.7).

The beneficial effects of the in-hospital exercise intervention extended to secondary end points indicative of cognitive capacity (MMSE, 1.8 points; 95% CI, 1.3-2.3), mood status (GDS, −2.0 points; 95% CI, −2.5 to −1.6), QoL (EuroQol-5D, 13.2 points; 95% CI, 8.2-18.2), and handgrip strength (2.3 kg; 95% CI, 1.8-2.8) compared to those who received usual care. In contrast, no differences were observed between groups that received exercise intervention and usual care in incident delirium, LOS, falls during hospitalization, transfer after discharge, and 3-month hospital readmission rate and mortality.

Conclusion. An individualized, multicomponent physical exercise program that includes low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking exercises performed during the course of hospitalization (average of 5 days) can reverse functional decline associated with acute hospitalization in very elderly patients. Furthermore, this in-hospital exercise intervention is safe and has a high adherence rate, and thus represents an opportunity to improve quality of care in this vulnerable population.

Commentary

Frail elderly patients are highly susceptible to adverse outcomes of acute hospitalization, including functional decline, disability, nursing home placement, rehospitalization, and mortality.1 Mobility limitation, a major hazard of hospitalization, has been associated with poorer functional recovery and increased vulnerability to these major adverse events after hospital discharge.2-4 Interdisciplinary care models delivered during hospitalization (eg, Geriatric Evaluation Unit, Acute Care for Elders) that emphasize functional independence and provide protocols for exercise and rehabilitation have demonstrated reduced hospital LOS, discharge to nursing home, and mortality, and improved functional status in elderly patients.5-7 Despite this evidence, significant gaps in knowledge exist in understanding whether early implementation of an individualized, multicomponent exercise training program can benefit the oldest old patients who are acutely hospitalized.

This study reported by Martinez-Velilla and colleagues provides an important and timely investigation in examining the effects of an individualized, multicomponent (ie, low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking) in-hospital exercise intervention on functional outcomes of hospitalized octogenarians and nonagenarians. The authors reported that such an intervention, administered 2 sessions per day for 5 to 7 consecutive days, can be safely implemented and reverse functional decline (ie, improvement in Barthel Index and SPPB score over course of hospital stay) typically associated with acute hospitalization in these vulnerable individuals. These findings are particularly significant given the paucity of randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of exercise intervention in preserving functional capacity of geriatric patients in the setting of acute hospitalization. While much more research is needed to facilitate future development of a consensus opinion in this regard, results from this study provide the rationale that implementation of an individualized multicomponent exercise program is feasible and safe and may attenuate functional decline in hospitalized older patients. Finally, the beneficial effects of in-hospital exercise intervention may extend to cognitive capacity, mood status, and QoL—domains that are essential to optimizing patient-centered care in the frailest elderly patients.

The study was well conceived with a number of strengths, including its randomized clinical trial design. In addition, the trial patients were advanced in age (35.1% were nonagenarians), which is particularly important because this is a vulnerable population that is frequently excluded from participation in trials of exercise interventions and because the evidence-base for physical activity guidelines is suboptimal. Moreover, the authors demonstrated that an individualized multicomponent exercise program could be successfully implemented in elderly patients in an acute setting via daily exercise sessions. This test of feasibility is significant in that clinical trials in exercise intervention in geriatrics are commonly performed in nonacute settings in the community, long-term care facilities, or subacute care. The major limitation in this study centers on the generalizability of its findings. It was noted that some patients were not assessed for changes from baseline to discharge on the Barthel Index (6.1%) and SPPB (2.3%) because of their poor condition. The exclusion of the most debilitated patients limits the application of the study’s key findings to the frailest elderly patients, who are most likely to require acute hospital care.

Applications for Clinical Pract

Functional decline is an exceedingly common adverse outcome associated with hospitalization in older patients. While more evidence is needed, early implementation of an individualized, multicomponent exercise regimen during hospitalization may help to prevent functional decline in vulnerable elderly patients.

—Fred Ko, MD, MS

Study Overview

Objective. To assess the effects of an individualized, multicomponent exercise intervention on the functional status of very elderly patients who were acutely hospitalized compared with those who received usual care.

Design. A single-center, single-blind randomized clinical trial comparing elderly (≥ 75 years old) hospitalized patients who received in-hospital exercise (ie, individualized low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking exercises) versus control (ie, usual care that included physical rehabilitation if needed) interventions. The exercise intervention was adapted from the multicomponent physical exercise program Vivifrail and was supervised and conducted by a fitness specialist in 2 daily (1 morning and 1 evening) sessions lasting 20 minutes for 5 to 7 consecutive days. The morning session consisted of supervised and individualized progressive resistance, balance, and walking exercises. The evening session consisted of functional unsupervised exercises including light weights, extension and flexion of knee and hip, and walking.

Setting and participants. The study was conducted in an acute care unit in a tertiary public hospital in Navarra, Spain, between 1 February 2015 and 30 August 2017. A total of 370 elderly patients undergoing acute care hospitalization were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to receive in-hospital exercise or control intervention. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 75 years, Barthel Index score ≥ 60, and ambulatory with or without assistance.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was change in functional capacity from baseline (beginning of exercise or control intervention) to hospital discharge as assessed by the Barthel Index of independence and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). Secondary outcomes were changes in cognitive capacity (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]) and mood status (Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS]), quality of life (QoL; EuroQol-5D), handgrip strength (dominant hand), incident delirium (Confusion Assessment Method), length of stay (LOS), falls during hospitalization, transfer after discharge, and readmission rate and mortality at 3 months after discharge. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted.

Main results. Of the 370 patients included in the study’s analyses, 209 (56.5%) were women, mean age was 87.3 ± 4.9 years (range, 75-101 years; 130 [35.1%] nonagenarians). The median LOS was 8 days in both groups (interquartile range [IQR], 4 and 4 days, respectively). The median duration of the intervention was 5 days (IQR, 0 days), with 5 ± 1 morning and 4 ± 1 evening sessions in the exercise group. Adherence to the exercise intervention was high (95.8% for morning sessions; 83.4% for evening sessions), and no adverse effects were observed with the intervention.

The in-hospital exercise intervention program yielded significant benefits over usual care in functional outcomes in elderly patients. The exercise group had an increased change in measures of functional capacity compared to the usual care group (ie, Barthel Index, 6.9 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.4-9.5; SPPB score, 2.2 points; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6). Furthermore, acute hospitalization led to an impairment in functional capacity from baseline to discharge in the Barthel Index (−5.0 points; 95% CI, −6.8 to −3.2) in the usual care group. In contrast, exercise intervention reversed this decline and improved functional outcomes as assessed by Barthel Index (1.9 points; 95% CI, 0.2-3.7) and SPPB score (2.4 points; 95% CI, 2.1-2.7).

The beneficial effects of the in-hospital exercise intervention extended to secondary end points indicative of cognitive capacity (MMSE, 1.8 points; 95% CI, 1.3-2.3), mood status (GDS, −2.0 points; 95% CI, −2.5 to −1.6), QoL (EuroQol-5D, 13.2 points; 95% CI, 8.2-18.2), and handgrip strength (2.3 kg; 95% CI, 1.8-2.8) compared to those who received usual care. In contrast, no differences were observed between groups that received exercise intervention and usual care in incident delirium, LOS, falls during hospitalization, transfer after discharge, and 3-month hospital readmission rate and mortality.

Conclusion. An individualized, multicomponent physical exercise program that includes low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking exercises performed during the course of hospitalization (average of 5 days) can reverse functional decline associated with acute hospitalization in very elderly patients. Furthermore, this in-hospital exercise intervention is safe and has a high adherence rate, and thus represents an opportunity to improve quality of care in this vulnerable population.

Commentary

Frail elderly patients are highly susceptible to adverse outcomes of acute hospitalization, including functional decline, disability, nursing home placement, rehospitalization, and mortality.1 Mobility limitation, a major hazard of hospitalization, has been associated with poorer functional recovery and increased vulnerability to these major adverse events after hospital discharge.2-4 Interdisciplinary care models delivered during hospitalization (eg, Geriatric Evaluation Unit, Acute Care for Elders) that emphasize functional independence and provide protocols for exercise and rehabilitation have demonstrated reduced hospital LOS, discharge to nursing home, and mortality, and improved functional status in elderly patients.5-7 Despite this evidence, significant gaps in knowledge exist in understanding whether early implementation of an individualized, multicomponent exercise training program can benefit the oldest old patients who are acutely hospitalized.

This study reported by Martinez-Velilla and colleagues provides an important and timely investigation in examining the effects of an individualized, multicomponent (ie, low-intensity resistance, balance, and walking) in-hospital exercise intervention on functional outcomes of hospitalized octogenarians and nonagenarians. The authors reported that such an intervention, administered 2 sessions per day for 5 to 7 consecutive days, can be safely implemented and reverse functional decline (ie, improvement in Barthel Index and SPPB score over course of hospital stay) typically associated with acute hospitalization in these vulnerable individuals. These findings are particularly significant given the paucity of randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of exercise intervention in preserving functional capacity of geriatric patients in the setting of acute hospitalization. While much more research is needed to facilitate future development of a consensus opinion in this regard, results from this study provide the rationale that implementation of an individualized multicomponent exercise program is feasible and safe and may attenuate functional decline in hospitalized older patients. Finally, the beneficial effects of in-hospital exercise intervention may extend to cognitive capacity, mood status, and QoL—domains that are essential to optimizing patient-centered care in the frailest elderly patients.

The study was well conceived with a number of strengths, including its randomized clinical trial design. In addition, the trial patients were advanced in age (35.1% were nonagenarians), which is particularly important because this is a vulnerable population that is frequently excluded from participation in trials of exercise interventions and because the evidence-base for physical activity guidelines is suboptimal. Moreover, the authors demonstrated that an individualized multicomponent exercise program could be successfully implemented in elderly patients in an acute setting via daily exercise sessions. This test of feasibility is significant in that clinical trials in exercise intervention in geriatrics are commonly performed in nonacute settings in the community, long-term care facilities, or subacute care. The major limitation in this study centers on the generalizability of its findings. It was noted that some patients were not assessed for changes from baseline to discharge on the Barthel Index (6.1%) and SPPB (2.3%) because of their poor condition. The exclusion of the most debilitated patients limits the application of the study’s key findings to the frailest elderly patients, who are most likely to require acute hospital care.

Applications for Clinical Pract

Functional decline is an exceedingly common adverse outcome associated with hospitalization in older patients. While more evidence is needed, early implementation of an individualized, multicomponent exercise regimen during hospitalization may help to prevent functional decline in vulnerable elderly patients.

—Fred Ko, MD, MS

1. Goldwater DS, Dharmarajan K, McEwan BS, Krumholz HM. Is posthospital syndrome a result of hospitalization-induced allostatic overload? J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5).doi:10.12788/jhm.2986.

2. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:219-223.

3. Minnick AF, Mion LC, Johnson ME, et al. Prevalence and variation of physical restraint use in acute care settings in the US. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:30-37.

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Sinoff G et al. Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:266-273.

5. Rubenstein LZ, et al. Effectiveness of a geriatric evaluation unit. A randomized clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1664-1670.

6. Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1338-1344.

7. de Morton NA, Keating JL, Jeffs K. Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD005955.

1. Goldwater DS, Dharmarajan K, McEwan BS, Krumholz HM. Is posthospital syndrome a result of hospitalization-induced allostatic overload? J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5).doi:10.12788/jhm.2986.

2. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:219-223.

3. Minnick AF, Mion LC, Johnson ME, et al. Prevalence and variation of physical restraint use in acute care settings in the US. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:30-37.

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Sinoff G et al. Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:266-273.

5. Rubenstein LZ, et al. Effectiveness of a geriatric evaluation unit. A randomized clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1664-1670.

6. Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1338-1344.

7. de Morton NA, Keating JL, Jeffs K. Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD005955.

Androgen Deprivation Therapy Combined with Radiation in High-Risk Prostate Cancer . . . How Long Do We Go?

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the outcomes of 18 months versus 36 months of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with radiation in high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).

Design. Phase 3 multicenter, randomized superiority trial.

Participants. This study enrolled patients aged ≤ 80 years with HRPC. All patients had no evidence of regional or distant metastasis. High-risk disease was defined as any of the following: clinical stage T3 or T4, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level > 20 ng/mL, or Gleason score > 7.

Methods. Prior to randomization, all patients received 4 months of ADT with goserelin 10.8 mg and anti-androgen therapy with bicalutamide 50 mg daily for 30 days. Patients were then randomly assigned to 18 (short arm) or 36 (long arm) months of ADT in combination with radiation therapy (RT). The randomization was stratified by stage (T1-2 vs T3-4), Gleason score (< 7 vs > 7) and PSA level (< 20 ng/mL vs > 20 ng/mL). The standard radiation dose was 70 Gy to the prostate and 44 Gy to the pelvis. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging exam of the abdomen and pelvis and a bone scan were performed to rule out regional or distant metastases. PSA level was monitored every 3 months for 18 months, every 6 months up to the third year, and yearly thereafter.

Main outcome measures. The 2 primary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QoL) at 5 years. The secondary end points were biochemical failure (BF)defined as PSA nadir plus 2, disease-free survival (DFS), and site(s) of tumor relapse.

Main results. The 5-year OS was 91% and 86% for the 36- and 18-month groups, respectively (P = 0.07). The 10-year OS was 62% for both groups (P = 0.7), and the global hazard ratio (HR) was 1.02 (P = 0.8). The disease-specific survival (DSS) was similar in both groups at 5 years (98% vs 97%) and at 10 years (91% vs 92%) in the long versus short arm, respectively. The rate of prostate cancer–specific death was 21% versus 23% in the long versus short arm, respectively. In a multivariate analysis for OS, only age and Gleason score > 7 were statistically significant survival predictors. BF rate at 10 years was 25% for 36 months as compared with 31% for 18 months (HR, 0.71, P = 0.02). The 10-year DFS rates were 45% and 39% for 36 and 18 months, respectively (HR, 0.68, P = 0.08). Forty patients in the long arm versus 43 in the short arm developed distant metastasis. Both groups developed similar sites of metastasis, which was predominantly osseous. Some aspects of the EORTC30 and PR25 scales were significant, mostly pertaining to sexual activity, fatigue, and hormone-related symptoms in favor of the 18-month group. The median time to testosterone recovery after completion of ADT was 2.1 years for the short arm versus 4 years in the long arm (P = 0.02). The compliance rate with ADT was 88% in the short arm versus 53% in the long arm. The main reason for nonadherence was side effects in 54% of the patients in the long arm and 31% in the short arm.

Conclusion. The results of the current study suggest that 18 months of ADT in combination with RT yields similar 10-year OS and improved QoL compared with 36 months in patients with HRPC.

Commentary

The role of ADT for HRPC in combination with RT has been well established by evidence from several trials; however, the comparator arms and patient characteristics between these studies have been quite heterogeneous. For instance, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 85-31 trial compared indefinite ADT with RT versus RT alone and showed significantly better 10-year OS in the ADT plus RT arm.1 Similarly, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EROTC) 22961 trial showed an OS benefit for 36 months versus 6 months of ADT in combination with radiation.2 Additionally, the RTOG 92-02 trial, which compared 4 months versus 24 months of ADT with radiation, also found a significantly improved 10-year OS with a longer course of ADT.3 Taken together these data suggest that 4 to 6 months of ADT is inferior to 24 to 36 months of ADT in HRPC.

Several differences, however, exist in patient characteristics between the present trial and the earlier trials, justifiably reflecting the change of practice in the PSA era. For instance, the present study has a higher percentage of patients with Gleason scores 8-10 (60%) compared to the EROTC and RTOG studies (15%-35%) and a lower percentage of patients with T3 and T4 tumors. Patients with high Gleason scores are believed to have a higher risk of micro-metastasis at the time of diagnosis and higher chances of castration resistance. Therefore, inclusion of a (presumably) larger high-risk patient subgroup in the present study lends further credence to results indicating similar OS with a shorter course of ADT. A post hoc analysis including only patients with Gleason score 8-10 performed for OS, DSS, BF, and DFS showed no significant difference in any of these variables between the arms. Analysis of the interaction between ADT duration in the Gleason 8-10 subgroup versus Gleason 7 for OS, DFS, DSS and BF found no significant differences. This again suggests that 18 months of ADT may be sufficient for this high-risk group; however, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from this unplanned subgroup analysis.

Based on the results of the current study, it seems that 18 months of ADT is adequate for many, but not necessarily all, patients. For instance, there was a significantly higher incidence of BF in the 18-month arm. Applying this data to younger patients may require a more nuanced approach, as it is possible that with longer follow-up this higher rate of BF may translate into a difference in OS. Therefore, life expectancy and comorbid conditions always need to be incorporated into clinical decision making with regards to ADT duration. In a study by Rose et al, the risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality significantly decreased by using ADT plus RT for men with HRPC with a low, but not a high, competing mortality score.4 The clinical significance of this finding is that adding ADT to RT might significantly reduce the risk of death from prostate cancer only in the setting of low competing risks.

Another concept to ponder is the optimum duration of ADT in the era of RT dose escalation. Currently, there are emerging techniques for delivering higher radiation doses and combining brachytherapy with external beam radiotherapy for HRPC, and the role of whole pelvic radiation is being investigated. New data suggests that higher radiation doses can lead to improvement in outcomes for HRPC. The DART01/05 study compared 4 versus 24 months of ADT with 76 to 82 Gy of RT and reported improved 5-year OS, DFS, and metastasis-free survival with longer ADT duration.5 Moreover, Kishan et al reported improved prostate cancer–specific mortality when brachytherapy boost was added to radiation compared to radiation alone in patients with Gleason scores 9 and 10.6 Therefore, the optimal duration of ADT in the setting of dose-escalated radiotherapy is not yet known. Also, it is important to note that unlike the prior RTOG and EORTC studies, this study did not include patients with evidence of regional nodal disease, and thus the present data should not be applied to this patient population.

Applications to Clinical Practice

This study’s results suggesting that 18 months of ADT in combination with RT yields similar 10-year OS and improved QoL compared with 36 months of ADT in patients with HRPC should be interpreted with caution when treating very young patients, since the higher rate of BF in the short arm may impact the OS with longer follow-up. Additionally, patients’ QoL and tolerance to ADT-related adverse effects should be taken into consideration given that compliance with 36 months of ADT was only 53% in this study.

—Jailan Elayoubi, MD, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

1. Pilepich MV, Winter K, Lawton CA, et al. Androgen suppression adjuvant to definitive radiotherapy in prostate carcinoma—long-term results of phase III RTOG 85–31. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1285-1290.

2. Bolla M, de Reijke TM, Van Tienhoven G, et al. Duration of androgen suppression in the treatment of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2516-2527.

3. Horwitz EM, Bae K, Hanks GE, Porter A, et al. Ten-year follow-up of radiation therapy oncology group protocol 92-02: a phase III trial of the duration of elective androgen deprivation in locally advanced prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2497–2504.

4. Rose BS, Chen MH, Wu J, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy use in the setting of high-dose radiation therapy and the risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality stratified by the extent of competing mortality. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:778-784.

5. Zapatero A, Guerrero A, Maldonado X, et al. High-dose radiotherapy with short-term or long-term androgen deprivation in localised prostate cancer (DART01/05 GICOR): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:320-327.

6. Kishan, AU, Cook, RR, Ciezki, JP, et al. Radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, or external beam radiotherapy with brachytherapy boost and disease progression and mortality in patients with gleason score 9-10 prostate cancer. JAMA. 2018;319:896-905.

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the outcomes of 18 months versus 36 months of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with radiation in high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).

Design. Phase 3 multicenter, randomized superiority trial.

Participants. This study enrolled patients aged ≤ 80 years with HRPC. All patients had no evidence of regional or distant metastasis. High-risk disease was defined as any of the following: clinical stage T3 or T4, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level > 20 ng/mL, or Gleason score > 7.

Methods. Prior to randomization, all patients received 4 months of ADT with goserelin 10.8 mg and anti-androgen therapy with bicalutamide 50 mg daily for 30 days. Patients were then randomly assigned to 18 (short arm) or 36 (long arm) months of ADT in combination with radiation therapy (RT). The randomization was stratified by stage (T1-2 vs T3-4), Gleason score (< 7 vs > 7) and PSA level (< 20 ng/mL vs > 20 ng/mL). The standard radiation dose was 70 Gy to the prostate and 44 Gy to the pelvis. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging exam of the abdomen and pelvis and a bone scan were performed to rule out regional or distant metastases. PSA level was monitored every 3 months for 18 months, every 6 months up to the third year, and yearly thereafter.

Main outcome measures. The 2 primary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QoL) at 5 years. The secondary end points were biochemical failure (BF)defined as PSA nadir plus 2, disease-free survival (DFS), and site(s) of tumor relapse.

Main results. The 5-year OS was 91% and 86% for the 36- and 18-month groups, respectively (P = 0.07). The 10-year OS was 62% for both groups (P = 0.7), and the global hazard ratio (HR) was 1.02 (P = 0.8). The disease-specific survival (DSS) was similar in both groups at 5 years (98% vs 97%) and at 10 years (91% vs 92%) in the long versus short arm, respectively. The rate of prostate cancer–specific death was 21% versus 23% in the long versus short arm, respectively. In a multivariate analysis for OS, only age and Gleason score > 7 were statistically significant survival predictors. BF rate at 10 years was 25% for 36 months as compared with 31% for 18 months (HR, 0.71, P = 0.02). The 10-year DFS rates were 45% and 39% for 36 and 18 months, respectively (HR, 0.68, P = 0.08). Forty patients in the long arm versus 43 in the short arm developed distant metastasis. Both groups developed similar sites of metastasis, which was predominantly osseous. Some aspects of the EORTC30 and PR25 scales were significant, mostly pertaining to sexual activity, fatigue, and hormone-related symptoms in favor of the 18-month group. The median time to testosterone recovery after completion of ADT was 2.1 years for the short arm versus 4 years in the long arm (P = 0.02). The compliance rate with ADT was 88% in the short arm versus 53% in the long arm. The main reason for nonadherence was side effects in 54% of the patients in the long arm and 31% in the short arm.

Conclusion. The results of the current study suggest that 18 months of ADT in combination with RT yields similar 10-year OS and improved QoL compared with 36 months in patients with HRPC.

Commentary

The role of ADT for HRPC in combination with RT has been well established by evidence from several trials; however, the comparator arms and patient characteristics between these studies have been quite heterogeneous. For instance, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 85-31 trial compared indefinite ADT with RT versus RT alone and showed significantly better 10-year OS in the ADT plus RT arm.1 Similarly, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EROTC) 22961 trial showed an OS benefit for 36 months versus 6 months of ADT in combination with radiation.2 Additionally, the RTOG 92-02 trial, which compared 4 months versus 24 months of ADT with radiation, also found a significantly improved 10-year OS with a longer course of ADT.3 Taken together these data suggest that 4 to 6 months of ADT is inferior to 24 to 36 months of ADT in HRPC.

Several differences, however, exist in patient characteristics between the present trial and the earlier trials, justifiably reflecting the change of practice in the PSA era. For instance, the present study has a higher percentage of patients with Gleason scores 8-10 (60%) compared to the EROTC and RTOG studies (15%-35%) and a lower percentage of patients with T3 and T4 tumors. Patients with high Gleason scores are believed to have a higher risk of micro-metastasis at the time of diagnosis and higher chances of castration resistance. Therefore, inclusion of a (presumably) larger high-risk patient subgroup in the present study lends further credence to results indicating similar OS with a shorter course of ADT. A post hoc analysis including only patients with Gleason score 8-10 performed for OS, DSS, BF, and DFS showed no significant difference in any of these variables between the arms. Analysis of the interaction between ADT duration in the Gleason 8-10 subgroup versus Gleason 7 for OS, DFS, DSS and BF found no significant differences. This again suggests that 18 months of ADT may be sufficient for this high-risk group; however, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from this unplanned subgroup analysis.

Based on the results of the current study, it seems that 18 months of ADT is adequate for many, but not necessarily all, patients. For instance, there was a significantly higher incidence of BF in the 18-month arm. Applying this data to younger patients may require a more nuanced approach, as it is possible that with longer follow-up this higher rate of BF may translate into a difference in OS. Therefore, life expectancy and comorbid conditions always need to be incorporated into clinical decision making with regards to ADT duration. In a study by Rose et al, the risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality significantly decreased by using ADT plus RT for men with HRPC with a low, but not a high, competing mortality score.4 The clinical significance of this finding is that adding ADT to RT might significantly reduce the risk of death from prostate cancer only in the setting of low competing risks.

Another concept to ponder is the optimum duration of ADT in the era of RT dose escalation. Currently, there are emerging techniques for delivering higher radiation doses and combining brachytherapy with external beam radiotherapy for HRPC, and the role of whole pelvic radiation is being investigated. New data suggests that higher radiation doses can lead to improvement in outcomes for HRPC. The DART01/05 study compared 4 versus 24 months of ADT with 76 to 82 Gy of RT and reported improved 5-year OS, DFS, and metastasis-free survival with longer ADT duration.5 Moreover, Kishan et al reported improved prostate cancer–specific mortality when brachytherapy boost was added to radiation compared to radiation alone in patients with Gleason scores 9 and 10.6 Therefore, the optimal duration of ADT in the setting of dose-escalated radiotherapy is not yet known. Also, it is important to note that unlike the prior RTOG and EORTC studies, this study did not include patients with evidence of regional nodal disease, and thus the present data should not be applied to this patient population.

Applications to Clinical Practice

This study’s results suggesting that 18 months of ADT in combination with RT yields similar 10-year OS and improved QoL compared with 36 months of ADT in patients with HRPC should be interpreted with caution when treating very young patients, since the higher rate of BF in the short arm may impact the OS with longer follow-up. Additionally, patients’ QoL and tolerance to ADT-related adverse effects should be taken into consideration given that compliance with 36 months of ADT was only 53% in this study.

—Jailan Elayoubi, MD, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the outcomes of 18 months versus 36 months of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with radiation in high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).

Design. Phase 3 multicenter, randomized superiority trial.

Participants. This study enrolled patients aged ≤ 80 years with HRPC. All patients had no evidence of regional or distant metastasis. High-risk disease was defined as any of the following: clinical stage T3 or T4, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level > 20 ng/mL, or Gleason score > 7.

Methods. Prior to randomization, all patients received 4 months of ADT with goserelin 10.8 mg and anti-androgen therapy with bicalutamide 50 mg daily for 30 days. Patients were then randomly assigned to 18 (short arm) or 36 (long arm) months of ADT in combination with radiation therapy (RT). The randomization was stratified by stage (T1-2 vs T3-4), Gleason score (< 7 vs > 7) and PSA level (< 20 ng/mL vs > 20 ng/mL). The standard radiation dose was 70 Gy to the prostate and 44 Gy to the pelvis. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging exam of the abdomen and pelvis and a bone scan were performed to rule out regional or distant metastases. PSA level was monitored every 3 months for 18 months, every 6 months up to the third year, and yearly thereafter.

Main outcome measures. The 2 primary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QoL) at 5 years. The secondary end points were biochemical failure (BF)defined as PSA nadir plus 2, disease-free survival (DFS), and site(s) of tumor relapse.

Main results. The 5-year OS was 91% and 86% for the 36- and 18-month groups, respectively (P = 0.07). The 10-year OS was 62% for both groups (P = 0.7), and the global hazard ratio (HR) was 1.02 (P = 0.8). The disease-specific survival (DSS) was similar in both groups at 5 years (98% vs 97%) and at 10 years (91% vs 92%) in the long versus short arm, respectively. The rate of prostate cancer–specific death was 21% versus 23% in the long versus short arm, respectively. In a multivariate analysis for OS, only age and Gleason score > 7 were statistically significant survival predictors. BF rate at 10 years was 25% for 36 months as compared with 31% for 18 months (HR, 0.71, P = 0.02). The 10-year DFS rates were 45% and 39% for 36 and 18 months, respectively (HR, 0.68, P = 0.08). Forty patients in the long arm versus 43 in the short arm developed distant metastasis. Both groups developed similar sites of metastasis, which was predominantly osseous. Some aspects of the EORTC30 and PR25 scales were significant, mostly pertaining to sexual activity, fatigue, and hormone-related symptoms in favor of the 18-month group. The median time to testosterone recovery after completion of ADT was 2.1 years for the short arm versus 4 years in the long arm (P = 0.02). The compliance rate with ADT was 88% in the short arm versus 53% in the long arm. The main reason for nonadherence was side effects in 54% of the patients in the long arm and 31% in the short arm.

Conclusion. The results of the current study suggest that 18 months of ADT in combination with RT yields similar 10-year OS and improved QoL compared with 36 months in patients with HRPC.

Commentary

The role of ADT for HRPC in combination with RT has been well established by evidence from several trials; however, the comparator arms and patient characteristics between these studies have been quite heterogeneous. For instance, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 85-31 trial compared indefinite ADT with RT versus RT alone and showed significantly better 10-year OS in the ADT plus RT arm.1 Similarly, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EROTC) 22961 trial showed an OS benefit for 36 months versus 6 months of ADT in combination with radiation.2 Additionally, the RTOG 92-02 trial, which compared 4 months versus 24 months of ADT with radiation, also found a significantly improved 10-year OS with a longer course of ADT.3 Taken together these data suggest that 4 to 6 months of ADT is inferior to 24 to 36 months of ADT in HRPC.

Several differences, however, exist in patient characteristics between the present trial and the earlier trials, justifiably reflecting the change of practice in the PSA era. For instance, the present study has a higher percentage of patients with Gleason scores 8-10 (60%) compared to the EROTC and RTOG studies (15%-35%) and a lower percentage of patients with T3 and T4 tumors. Patients with high Gleason scores are believed to have a higher risk of micro-metastasis at the time of diagnosis and higher chances of castration resistance. Therefore, inclusion of a (presumably) larger high-risk patient subgroup in the present study lends further credence to results indicating similar OS with a shorter course of ADT. A post hoc analysis including only patients with Gleason score 8-10 performed for OS, DSS, BF, and DFS showed no significant difference in any of these variables between the arms. Analysis of the interaction between ADT duration in the Gleason 8-10 subgroup versus Gleason 7 for OS, DFS, DSS and BF found no significant differences. This again suggests that 18 months of ADT may be sufficient for this high-risk group; however, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from this unplanned subgroup analysis.

Based on the results of the current study, it seems that 18 months of ADT is adequate for many, but not necessarily all, patients. For instance, there was a significantly higher incidence of BF in the 18-month arm. Applying this data to younger patients may require a more nuanced approach, as it is possible that with longer follow-up this higher rate of BF may translate into a difference in OS. Therefore, life expectancy and comorbid conditions always need to be incorporated into clinical decision making with regards to ADT duration. In a study by Rose et al, the risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality significantly decreased by using ADT plus RT for men with HRPC with a low, but not a high, competing mortality score.4 The clinical significance of this finding is that adding ADT to RT might significantly reduce the risk of death from prostate cancer only in the setting of low competing risks.

Another concept to ponder is the optimum duration of ADT in the era of RT dose escalation. Currently, there are emerging techniques for delivering higher radiation doses and combining brachytherapy with external beam radiotherapy for HRPC, and the role of whole pelvic radiation is being investigated. New data suggests that higher radiation doses can lead to improvement in outcomes for HRPC. The DART01/05 study compared 4 versus 24 months of ADT with 76 to 82 Gy of RT and reported improved 5-year OS, DFS, and metastasis-free survival with longer ADT duration.5 Moreover, Kishan et al reported improved prostate cancer–specific mortality when brachytherapy boost was added to radiation compared to radiation alone in patients with Gleason scores 9 and 10.6 Therefore, the optimal duration of ADT in the setting of dose-escalated radiotherapy is not yet known. Also, it is important to note that unlike the prior RTOG and EORTC studies, this study did not include patients with evidence of regional nodal disease, and thus the present data should not be applied to this patient population.

Applications to Clinical Practice

This study’s results suggesting that 18 months of ADT in combination with RT yields similar 10-year OS and improved QoL compared with 36 months of ADT in patients with HRPC should be interpreted with caution when treating very young patients, since the higher rate of BF in the short arm may impact the OS with longer follow-up. Additionally, patients’ QoL and tolerance to ADT-related adverse effects should be taken into consideration given that compliance with 36 months of ADT was only 53% in this study.

—Jailan Elayoubi, MD, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

1. Pilepich MV, Winter K, Lawton CA, et al. Androgen suppression adjuvant to definitive radiotherapy in prostate carcinoma—long-term results of phase III RTOG 85–31. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1285-1290.

2. Bolla M, de Reijke TM, Van Tienhoven G, et al. Duration of androgen suppression in the treatment of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2516-2527.

3. Horwitz EM, Bae K, Hanks GE, Porter A, et al. Ten-year follow-up of radiation therapy oncology group protocol 92-02: a phase III trial of the duration of elective androgen deprivation in locally advanced prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2497–2504.

4. Rose BS, Chen MH, Wu J, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy use in the setting of high-dose radiation therapy and the risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality stratified by the extent of competing mortality. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:778-784.

5. Zapatero A, Guerrero A, Maldonado X, et al. High-dose radiotherapy with short-term or long-term androgen deprivation in localised prostate cancer (DART01/05 GICOR): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:320-327.

6. Kishan, AU, Cook, RR, Ciezki, JP, et al. Radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, or external beam radiotherapy with brachytherapy boost and disease progression and mortality in patients with gleason score 9-10 prostate cancer. JAMA. 2018;319:896-905.

1. Pilepich MV, Winter K, Lawton CA, et al. Androgen suppression adjuvant to definitive radiotherapy in prostate carcinoma—long-term results of phase III RTOG 85–31. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1285-1290.

2. Bolla M, de Reijke TM, Van Tienhoven G, et al. Duration of androgen suppression in the treatment of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2516-2527.

3. Horwitz EM, Bae K, Hanks GE, Porter A, et al. Ten-year follow-up of radiation therapy oncology group protocol 92-02: a phase III trial of the duration of elective androgen deprivation in locally advanced prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2497–2504.

4. Rose BS, Chen MH, Wu J, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy use in the setting of high-dose radiation therapy and the risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality stratified by the extent of competing mortality. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:778-784.

5. Zapatero A, Guerrero A, Maldonado X, et al. High-dose radiotherapy with short-term or long-term androgen deprivation in localised prostate cancer (DART01/05 GICOR): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:320-327.

6. Kishan, AU, Cook, RR, Ciezki, JP, et al. Radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, or external beam radiotherapy with brachytherapy boost and disease progression and mortality in patients with gleason score 9-10 prostate cancer. JAMA. 2018;319:896-905.

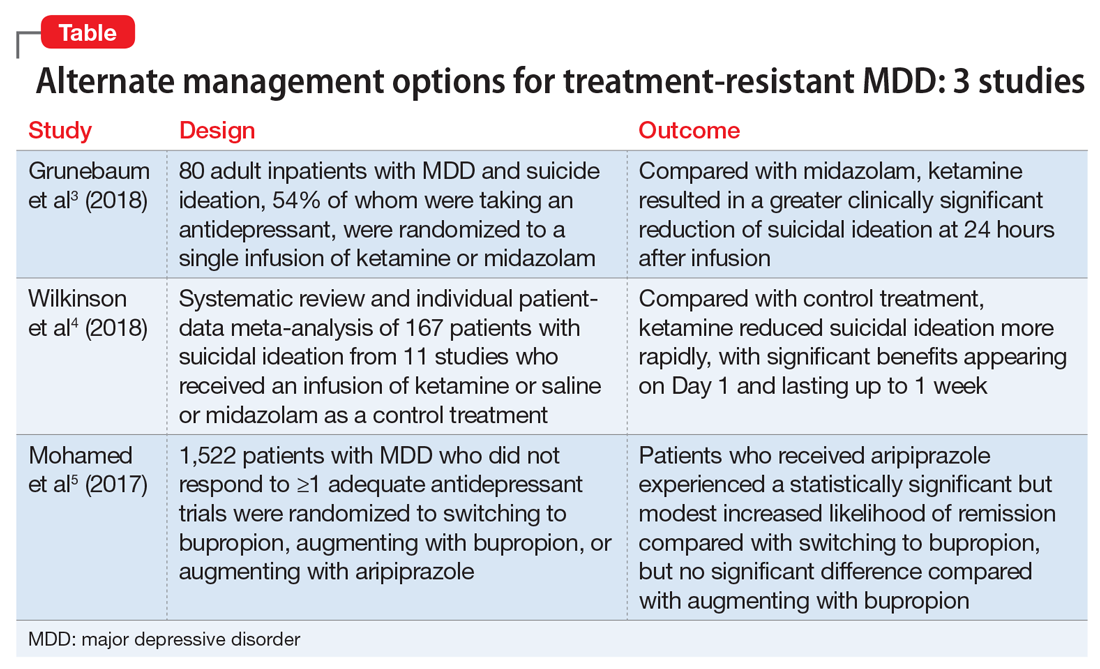

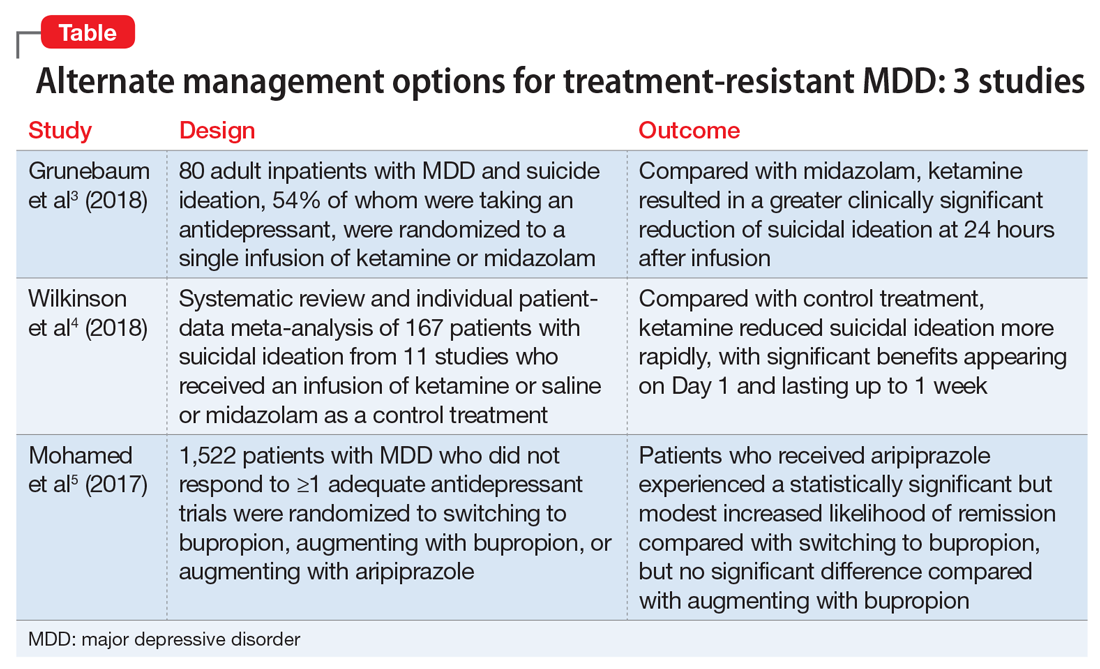

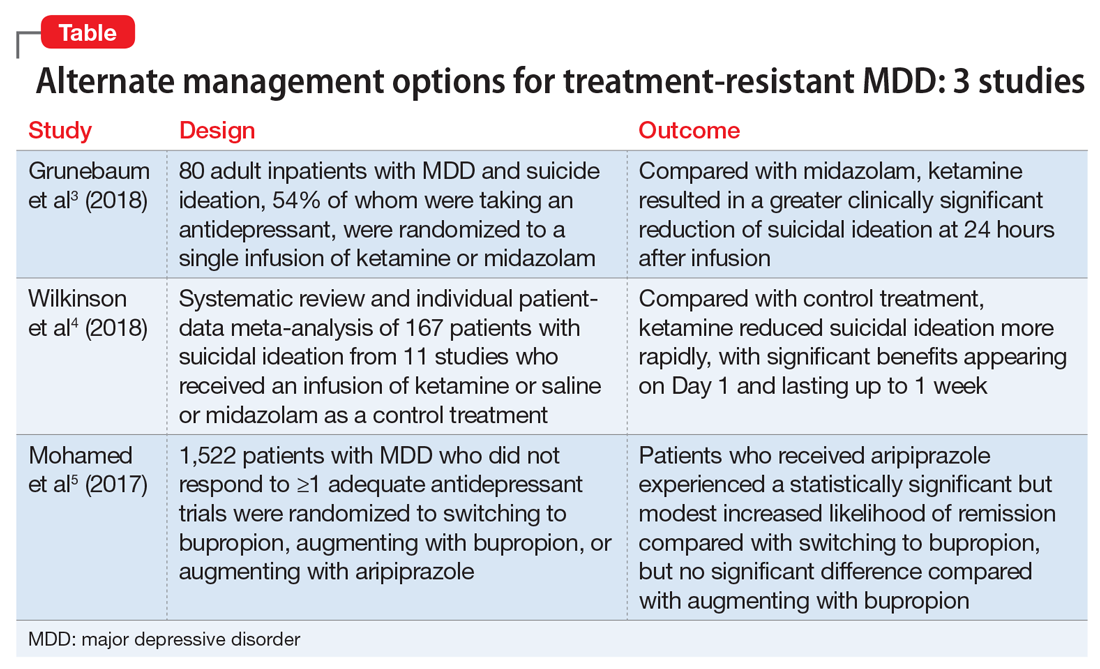

Management of treatment-resistant depression: A review of 3 studies

An estimated 7.1% of the adults in United States had a major depressive episode in 2017, and this prevalence has been trending upward over the past few years.1 The prevalence is even higher in adults between age 18 and 25 (13.1%).1 Like other psychiatric diagnoses, major depressive disorder (MDD) has a significant impact on productivity as well as daily functioning. Only one-third of patients with MDD achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication.2 This leaves an estimated 11.47 million people in the United States in need of an alternate regimen for management of their depressive episode.

The data on evidence-based biologic treatments for treatment-resistant depression are limited (other than for electroconvulsive therapy). Pharmacologic options include switching to a different medication, combining medications, and augmentation strategies or novel approaches such as ketamine and related agents. Here we summarize the findings from 3 recent studies that investigate alternate management options for MDD.

Ketamine: Randomized controlled trial

Traditional antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation by improving depressive symptoms, but this effect may take weeks. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

_

1. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

Grunebaum et al3 evaluated the acute effect of adjunctive subanesthetic IV ketamine on clinically significant suicidal ideation in patients with MDD, with a comparison arm that received an infusion of midazolam.

Study design

- 80 inpatients (age 18 to 65 years) with MDD who had a score ≥16 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and a score ≥4 on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI). Approximately one-half (54%) were taking an antidepressant

- Patients were randomly assigned to IV racemic ketamine hydrochloride, .5 mg/kg, or IV midazolam, .02 mg/kg, both administered in 100 mL normal saline over 40 minutes.

Outcomes

- Scale for Suicidal Ideation scores were assessed at screening, before infusion, 230 minutes after infusion, 24 hours after infusion, and after 1 to 6 weeks of follow-up. The average SSI score on Day 1 was 4.96 points lower in the ketamine group compared with the midazolam group. The proportion of responders (defined as patients who experienced a 50% reduction in SSI score) on Day 1 was 55% for patients in the ketamine group compared with 30% in the midazolam group.

Conclusion

- Compared with midazolam, ketamine produced a greater clinically meaningful reduction in suicidal ideation 24 hours after infusion.

Apart from the primary outcome of reduction in suicidal ideation, greater reductions were also found in overall mood disturbance, depression subscale, and fatigue subscale scores as assessed on the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Although the study noted improvement in depression scores, the proportion of responders on Day 1 in depression scales, including HAM-D and the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory, fell short of statistical significance. Overall, compared with the midazolam infusion, a single adjunctive subanesthetic ketamine infusion was associated with a greater clinically significant reduction in suicidal ideation on Day 1.

Continue to: Ketamine

Ketamine: Review and meta-analysis

Wilkinson et al4 conducted a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis of 11 similar comparison intervention studies examining the effects of ketamine in reducing suicidal thoughts.

2. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):150-158.

Study design

- Review of 11 studies of a single dose of IV ketamine for treatment of any psychiatric disorder. Only comparison intervention trials using saline placebo or midazolam were included:

- Individual patient-level data of 298 patients were obtained from 10 of the 11 trials. Analysis was performed on 167 patients who had suicidal ideation at baseline.

- Results were assessed by clinician-administered rating scales.

Outcomes

- Ketamine reduced suicidal ideation more rapidly compared with control infusions as assessed by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and HAM-D, with significant benefits appearing on Day 1 and extending up to Day 7. The mean MADRS score in the ketamine group decreased to 19.5 from 33.8 within 1 day of infusion, compared with a reduction to 29.2 from 32.9 in the control groups.

- The number needed to treat to be free of suicidal ideation for ketamine (compared with control) was 3.1 to 4.0 for all time points in the first week after infusion.

Conclusion

- This meta-analysis provided evidence from the largest sample to date (N = 298) that ketamine reduces suicidal ideation partially independently of mood symptoms.

While the anti-suicidal effects of ketamine appear to be robust in the above studies, the possibility of rebound suicidal ideation remains in the weeks or months following exposure. Also, these studies only prove a reduction in suicidal ideation; reduction in suicidal behavior was not studied. Nevertheless, ketamine holds considerable promise as a potential rapid-acting agent in patients at risk of suicide.

Continue to: Strategies for augmentation or switching

Strategies for augmentation or switching

Only one-third of the patients with depression achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication. The American Psychiatric Association’s current management guidelines2 for patients who do not respond to the first-choice antidepressant include multiple options. Switching strategies recommended in these guidelines include changing to an antidepressant of the same class, or to one from a different class (eg, from a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or from an SSRI to a tricyclic antidepressant). Augmentation strategies include augmenting with a non-monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressant from a different class, lithium, thyroid hormone, or an atypical antipsychotic.

The VAST-D trial5 evaluated the relative effectiveness and safety of 3 common treatments for treatment-resistant MDD:

- switching to bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with the second-generation antipsychotic aripiprazole.

3. Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

Study design

- A multi-site, randomized, single-blind, parallel-assignment trial of 1,522 patients at 35 US Veteran Health Administration medical centers with nonpsychotic MDD with a suboptimal response to at least one antidepressant (defined as a score of ≥16 on the Quick Inventory Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated questionnaire [QIDS-C16]).

- Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: switching to bupropion (n = 511), augmenting with bupropion (n = 506), or augmenting with aripiprazole (n = 505).

- The primary outcome was remission (defined as a QIDS-C16 score ≤5 at 2 consecutively scheduled follow-up visits). Secondary outcome was a reduction in QIDS-C16 score by ≥50%, or a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Improvement scale score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved).

Outcomes

- The aripiprazole group showed a modest, statistically significant remission rate (28.9%) compared with the bupropion switch group (22.3%), but did not show any statistically significant difference compared with the bupropion augmentation group.

- For the secondary outcome, there was a significantly higher response rate in the aripiprazole group (74.3%) compared with the bupropion switch group (62.4%) and bupropion augmentation group (65.6%). Response measured by the CGI– Improvement scale score also favored the aripiprazole group (79%) compared with the bupropion switch group (70%) and bupropion augmentation group (74%).

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Overall, the study found a statistically significant but modest increased likelihood of remission during 12 weeks of augmentation treatment with aripiprazole, compared with switching to bupropion monotherapy.

The studies discussed here, which are summarized in the Table,3-5 provide some potential avenues for research into interventions for patients who are acutely suicidal and those with treatment-resistant depression. Further research into long-term outcomes and adverse effects of ketamine use for suicidality in patients with depression is needed. The VAST-D trial suggests a need for further exploration into the efficacy of augmentation with second-generation antipsychotics for treatment-resistant depression.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Reports and detailed tables from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2017-NSDUH. Accessed November 12, 2018.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed November 12, 2018.

3. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

4. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):150-158.

5. Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

An estimated 7.1% of the adults in United States had a major depressive episode in 2017, and this prevalence has been trending upward over the past few years.1 The prevalence is even higher in adults between age 18 and 25 (13.1%).1 Like other psychiatric diagnoses, major depressive disorder (MDD) has a significant impact on productivity as well as daily functioning. Only one-third of patients with MDD achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication.2 This leaves an estimated 11.47 million people in the United States in need of an alternate regimen for management of their depressive episode.

The data on evidence-based biologic treatments for treatment-resistant depression are limited (other than for electroconvulsive therapy). Pharmacologic options include switching to a different medication, combining medications, and augmentation strategies or novel approaches such as ketamine and related agents. Here we summarize the findings from 3 recent studies that investigate alternate management options for MDD.

Ketamine: Randomized controlled trial

Traditional antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation by improving depressive symptoms, but this effect may take weeks. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

_

1. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

Grunebaum et al3 evaluated the acute effect of adjunctive subanesthetic IV ketamine on clinically significant suicidal ideation in patients with MDD, with a comparison arm that received an infusion of midazolam.

Study design

- 80 inpatients (age 18 to 65 years) with MDD who had a score ≥16 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and a score ≥4 on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI). Approximately one-half (54%) were taking an antidepressant

- Patients were randomly assigned to IV racemic ketamine hydrochloride, .5 mg/kg, or IV midazolam, .02 mg/kg, both administered in 100 mL normal saline over 40 minutes.

Outcomes

- Scale for Suicidal Ideation scores were assessed at screening, before infusion, 230 minutes after infusion, 24 hours after infusion, and after 1 to 6 weeks of follow-up. The average SSI score on Day 1 was 4.96 points lower in the ketamine group compared with the midazolam group. The proportion of responders (defined as patients who experienced a 50% reduction in SSI score) on Day 1 was 55% for patients in the ketamine group compared with 30% in the midazolam group.

Conclusion

- Compared with midazolam, ketamine produced a greater clinically meaningful reduction in suicidal ideation 24 hours after infusion.

Apart from the primary outcome of reduction in suicidal ideation, greater reductions were also found in overall mood disturbance, depression subscale, and fatigue subscale scores as assessed on the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Although the study noted improvement in depression scores, the proportion of responders on Day 1 in depression scales, including HAM-D and the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory, fell short of statistical significance. Overall, compared with the midazolam infusion, a single adjunctive subanesthetic ketamine infusion was associated with a greater clinically significant reduction in suicidal ideation on Day 1.

Continue to: Ketamine

Ketamine: Review and meta-analysis

Wilkinson et al4 conducted a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis of 11 similar comparison intervention studies examining the effects of ketamine in reducing suicidal thoughts.

2. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):150-158.

Study design

- Review of 11 studies of a single dose of IV ketamine for treatment of any psychiatric disorder. Only comparison intervention trials using saline placebo or midazolam were included:

- Individual patient-level data of 298 patients were obtained from 10 of the 11 trials. Analysis was performed on 167 patients who had suicidal ideation at baseline.

- Results were assessed by clinician-administered rating scales.

Outcomes

- Ketamine reduced suicidal ideation more rapidly compared with control infusions as assessed by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and HAM-D, with significant benefits appearing on Day 1 and extending up to Day 7. The mean MADRS score in the ketamine group decreased to 19.5 from 33.8 within 1 day of infusion, compared with a reduction to 29.2 from 32.9 in the control groups.

- The number needed to treat to be free of suicidal ideation for ketamine (compared with control) was 3.1 to 4.0 for all time points in the first week after infusion.

Conclusion

- This meta-analysis provided evidence from the largest sample to date (N = 298) that ketamine reduces suicidal ideation partially independently of mood symptoms.

While the anti-suicidal effects of ketamine appear to be robust in the above studies, the possibility of rebound suicidal ideation remains in the weeks or months following exposure. Also, these studies only prove a reduction in suicidal ideation; reduction in suicidal behavior was not studied. Nevertheless, ketamine holds considerable promise as a potential rapid-acting agent in patients at risk of suicide.

Continue to: Strategies for augmentation or switching

Strategies for augmentation or switching

Only one-third of the patients with depression achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication. The American Psychiatric Association’s current management guidelines2 for patients who do not respond to the first-choice antidepressant include multiple options. Switching strategies recommended in these guidelines include changing to an antidepressant of the same class, or to one from a different class (eg, from a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or from an SSRI to a tricyclic antidepressant). Augmentation strategies include augmenting with a non-monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressant from a different class, lithium, thyroid hormone, or an atypical antipsychotic.

The VAST-D trial5 evaluated the relative effectiveness and safety of 3 common treatments for treatment-resistant MDD:

- switching to bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with bupropion

- augmenting the current treatment with the second-generation antipsychotic aripiprazole.

3. Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(2):132-145.

Study design

- A multi-site, randomized, single-blind, parallel-assignment trial of 1,522 patients at 35 US Veteran Health Administration medical centers with nonpsychotic MDD with a suboptimal response to at least one antidepressant (defined as a score of ≥16 on the Quick Inventory Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated questionnaire [QIDS-C16]).

- Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: switching to bupropion (n = 511), augmenting with bupropion (n = 506), or augmenting with aripiprazole (n = 505).

- The primary outcome was remission (defined as a QIDS-C16 score ≤5 at 2 consecutively scheduled follow-up visits). Secondary outcome was a reduction in QIDS-C16 score by ≥50%, or a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Improvement scale score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved).

Outcomes

- The aripiprazole group showed a modest, statistically significant remission rate (28.9%) compared with the bupropion switch group (22.3%), but did not show any statistically significant difference compared with the bupropion augmentation group.

- For the secondary outcome, there was a significantly higher response rate in the aripiprazole group (74.3%) compared with the bupropion switch group (62.4%) and bupropion augmentation group (65.6%). Response measured by the CGI– Improvement scale score also favored the aripiprazole group (79%) compared with the bupropion switch group (70%) and bupropion augmentation group (74%).

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Overall, the study found a statistically significant but modest increased likelihood of remission during 12 weeks of augmentation treatment with aripiprazole, compared with switching to bupropion monotherapy.

The studies discussed here, which are summarized in the Table,3-5 provide some potential avenues for research into interventions for patients who are acutely suicidal and those with treatment-resistant depression. Further research into long-term outcomes and adverse effects of ketamine use for suicidality in patients with depression is needed. The VAST-D trial suggests a need for further exploration into the efficacy of augmentation with second-generation antipsychotics for treatment-resistant depression.

An estimated 7.1% of the adults in United States had a major depressive episode in 2017, and this prevalence has been trending upward over the past few years.1 The prevalence is even higher in adults between age 18 and 25 (13.1%).1 Like other psychiatric diagnoses, major depressive disorder (MDD) has a significant impact on productivity as well as daily functioning. Only one-third of patients with MDD achieve remission on the first antidepressant medication.2 This leaves an estimated 11.47 million people in the United States in need of an alternate regimen for management of their depressive episode.

The data on evidence-based biologic treatments for treatment-resistant depression are limited (other than for electroconvulsive therapy). Pharmacologic options include switching to a different medication, combining medications, and augmentation strategies or novel approaches such as ketamine and related agents. Here we summarize the findings from 3 recent studies that investigate alternate management options for MDD.

Ketamine: Randomized controlled trial

Traditional antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation by improving depressive symptoms, but this effect may take weeks. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

_

1. Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Choo TH, et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts in major depression: a midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):327-335.

Grunebaum et al3 evaluated the acute effect of adjunctive subanesthetic IV ketamine on clinically significant suicidal ideation in patients with MDD, with a comparison arm that received an infusion of midazolam.

Study design

- 80 inpatients (age 18 to 65 years) with MDD who had a score ≥16 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and a score ≥4 on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI). Approximately one-half (54%) were taking an antidepressant